Abstract

Zoocin A is a streptococcolytic peptidoglycan hydrolase with an unknown site of action that is produced by Streptococcus equi subsp. zooepidemicus 4881. Zoocin A has now been determined to be a d-alanyl-l-alanine endopeptidase by digesting susceptible peptidoglycan with a combination of mutanolysin and zoocin A, separating the resulting muropeptides by reverse-phase high-pressure liquid chromatography, and analyzing them by mass spectrometry (MS) in both the positive- and negative-ion modes to determine their compositions. In order to distinguish among possible structures for these muropeptides, they were N-terminally labeled with 4-sulfophenyl isothiocyanate (SPITC) and analyzed by tandem MS in the negative-ion mode. This novel application of SPITC labeling and MS/MS analysis can be used to analyze the structure of peptidoglycans and to determine the sites of action of other peptidoglycan hydrolases.

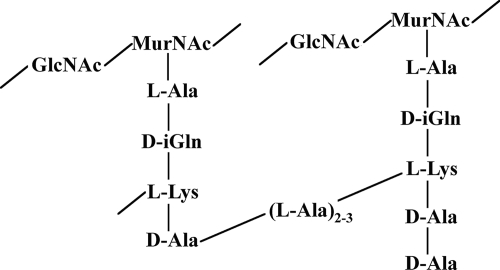

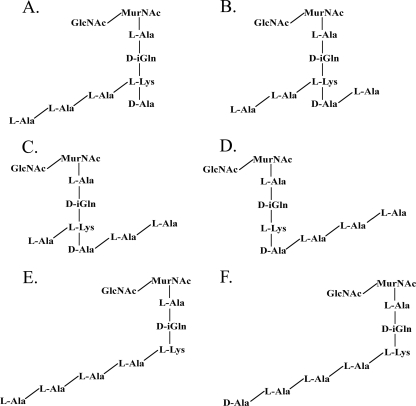

Streptococcal peptidoglycans (16) have a repeating backbone of the amino sugars N-acetylglucosamine (GlcNAc) and N-acetylmuramic acid (MurNAc). Connected to the lactyl group of MurNAc is a tetrapeptide (stem peptide) composed of l-alanine, d-isoglutamine (or d-isoglutamate), l-lysine, and d-alanine. The stem peptides are connected by peptide cross bridges that typically contain two or three l-alanine residues (Fig. 1). During peptidoglycan synthesis, the stem peptides contain an additional C-terminal d-alanine (Fig. 1) that is removed during cross-bridge formation by a transpeptidase (11). In some cases, the cross bridges are not formed and the terminal d-alanine may or may not be removed by a carboxypeptidase (11).

FIG. 1.

Typical structure of streptococcal peptidoglycan. Streptococci usually have two or three alanines in their peptide cross bridges, but in some strains other amino acids, such as serine, threonine, or glycine, can also be incorporated during peptidoglycan synthesis. The stem peptide on the right has not yet been cross-linked. In addition, carboxypeptidase activity may remove one or both of the d-alanines, which could result in stem peptides with fewer d-alanine residues at their C termini.

Zoocin A is a streptococcolytic enzyme produced by Streptococcus equi subsp. zooepidemicus 4881. The genes for zoocin A and for the zoocin A immunity factor (zif) are adjacent on the chromosome and are divergently transcribed (1). Zoocin A hydrolyzes the cell walls of some closely related streptococci, including S. pyogenes and S. mutans, the main causative agents of group A streptococcal sore throat and dental caries, respectively (20). Zoocin A is presumed to target peptidoglycan cross bridges based on three lines of evidence. First, the catalytic domain of zoocin A has a high degree of similarity to the catalytic domains of several bacteriolytic endopeptidases (lysostaphin [21], ALE-1 [22], LytM [23], and millericin B [3]). Second, the introduction of the gene for lysostaphin resistance into a zoocin A-sensitive streptococcus resulted in the insertion of serines into its peptidoglycan cross bridges and a decrease in sensitivity to zoocin A (6). Third, zoocin A covalently binds penicillin and slowly hydrolyzes a chromogenic cephalosporin, both of which are d-alanyl-d-alanine analogs. These three lines of evidence suggest that zoocin A hydrolyzes the bond between the terminal d-alanine of the stem peptide and the first l-alanine of the cross bridge (8).

If zoocin A is an endopeptidase, determination of its site of action on streptococcal peptidoglycans only by the mass of the products is not possible because the presence of alanines in the cross bridge and at the C terminus of the stem peptide can yield a variety of structurally different fragments that have the same mass (4). In streptococci, the number and order of the amino acids in the peptidoglycans are usually determined using a combination of tandem mass spectrometry (MS/MS) and Edman degradation (2, 7, 18). However, Edman sequencing can be time-consuming and requires the isolation of relatively large amounts of a purified product for analysis. Therefore, a simpler method for determination of the amino acid arrangement of peptidoglycan fragments after zoocin A digestion was desirable. In the present study, the site of action of zoocin A was determined by analysis of peptidoglycan fragments generated by digestion with a mixture of zoocin A and the muramidase mutanolysin. These muropeptides were purified using reverse-phase high-pressure liquid chromatography (RP-HPLC), and analysis by collision-induced dissociation (CID) MS/MS in both the positive- and negative-ion modes identified their composition. In order to distinguish among possible structures for these muropeptides, they were N-terminally labeled with 4-sulfophenyl isothiocyanate (SPITC) and analyzed by MS/MS in the negative-ion mode. SPITC labeling has been used in protein sequencing (5, 10), but to our knowledge this is the first report of its use in analysis of peptidoglycan structure.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Construction of a kanamycin-resistant zif-zooA knockout mutant.

Strain 4881.1KOK, which was constructed to facilitate genetic manipulations not reported here, was made by replacing the erythromycin resistance marker from strain 4881.1KOE (8) with the kanamycin resistance gene from Ω-Km2 (13). Plasmid p3-10 DNA (8) was transformed into strain 4881.1KOE, and kanamycin-resistant transformants were selected. These were then tested for a double-crossover event by a loss of resistance to erythromycin. One isolate that was resistant to kanamycin and sensitive to erythromycin and maintained the phenotype of the parent strain (streptomycin resistant, catalase negative, beta-hemolytic, sensitive to zoocin A, and negative for production of zoocin A) was designated strain 4881.1KOK. PCR and sequencing reactions were used to show that the insertion in this strain was at the correct site, as was done previously (8), using the primers 5′ AAT TCT CGT TTT CAT ACC TCG 3′ and 5′ CAA CTG TCC ATA CTC TGA TGT 3′.

Purification and analysis of peptidoglycans.

Peptidoglycans were purified and analyzed as previously described (6), with the exceptions that the cells were grown in Todd-Hewitt broth and were not subjected to mechanical fragmentation.

Dansylation of peptidoglycan fragments to detect free amino groups.

Five milligrams (wet weight) of purified peptidoglycan from susceptible strain 4881.1KOK in 1 ml of 50 mM Tris hydrochloride buffer (pH 8.8) was treated with 150 units of mutanolysin (Sigma Chemical Co., St. Louis, MO), with or without 50 μg of six-His-tagged recombinant zoocin A (9, 19), and incubated at 37°C for 15 h. After centrifugation (13,000 × g for 5 min) to remove undigested material, the samples were dried, dissolved in 1 ml of 40 mM Li2CO3 (pH 9.5), and treated with 0.5 ml of a solution (1.5 mg/ml) of 5-(dimethylamino)naphthalene-1-sulfonyl chloride (dansyl-Cl; Sigma) in acetonitrile. The reaction mixtures were incubated at 60°C for 30 min and then dried under a stream of nitrogen gas. The dried samples were suspended in 10% (vol/vol) acetonitrile in 200 mM ammonium bicarbonate. The samples were hydrolyzed with 0.7 ml of 6 M HCl for 15 h at 110°C and dried under a stream of nitrogen gas. The products were separated on a Spherisorb ODS-2 reverse-phase column (250 by 4.6 mm, with a 5-μm particle size; Waters Corp., Milford, MA) at room temperature, using a Shimadzu LC-6A liquid chromatograph (Shimadzu Scientific Instruments, Columbia, MD). The elution buffers were as follows: solution A, 10% (vol/vol) acetonitrile in 200 mM ammonium bicarbonate; and solution B, 45% (vol/vol) acetonitrile in 200 mM ammonium bicarbonate. The flow rate was 1 ml/min; the elution profile started with 100% solution A, followed by a linear gradient from 0% to 30% solution B over 25 min, a linear gradient of 30% to 45% solution B over 20 min, a linear gradient of 45% to 100% solution B over 15 min, and then 100% solution B for 30 min. Peaks were detected at 334 nm due to absorbance by the dansyl chromophore.

Structural determination of muropeptides.

Seventy-five milligrams (wet weight) of peptidoglycan in 1 ml of a 50 mM ammonium bicarbonate buffer (pH 8.0) was incubated at 37°C with shaking at 200 rpm for 24 h, with or without 200 μg of six-His-tagged recombinant zoocin A. The digest was lyophilized and then dissolved in 850 μl of a 25 mM potassium phosphate buffer (pH 6.5) containing 10 mM MgCl2. Mutanolysin (500 units; Sigma) was then added to both samples, and the reaction mixtures were incubated at 37°C with shaking at 200 rpm for 24 h. Undigested material was removed by centrifugation (18,000 × g for 5 min), and the supernatant was boiled for 5 min, cooled to room temperature, and then centrifuged again. In order to simplify the RP-HPLC chromatograms by eliminating anomers of MurNAc, the peptidoglycan fragments were reduced as follows. The supernatant was removed and mixed with an equal volume of 500 mM sodium borate buffer (pH 9.0). Two milligrams of sodium borohydride was added, and the sample was vortexed. The samples were incubated at room temperature for 30 min, and the reactions were stopped by adding 100 μl of 20% (vol/vol) ortho-phosphoric acid.

Muropeptides were separated by RP-HPLC with an instrument that consisted of a model 234 autoinjector, a model 322 solvent delivery system, and a model 156 UV-visible lamp (Gilson, Middleton, WI). The peptide fragments were separated at room temperature on a Grom-Sil 120 ODS-5 ST column (100 by 3 mm [internal diameter], with a 3-μm particle size; Rottenburg-Hailfingen, Germany), using a 0 to 25% solution B gradient applied between 5 and 90 min (solution A, 0.1% trifluoroacetic acid in water; and solution B, 0.085% trifluoroacetic acid in 80% acetonitrile). Absorbance was measured at 214 nm. Peaks that showed the greatest increase after digestion with zoocin A were collected and dried under vacuum with centrifugation (Speed-Vac; Thermo Fisher Scientific Inc., Waltham, MA).

MS of muropeptides.

Matrix-assisted laser desorption ionization-tandem time-of-flight MS (MALDI-tandem TOF MS) was carried out using an ABI 4800 MALDI-tandem TOF mass analyzer (Applied Biosystems, Framingham, MA). Dried fractions from RP-HPLC were dissolved in 2 μl of matrix (10 mg/ml α-cyano-4-hydroxycinnamic acid dissolved in 50% [vol/vol] aqueous acetonitrile containing 0.1% [vol/vol] trifluoroacetic acid). An aliquot of each sample (0.8 μl) was spotted onto a model 384 Opti-TOF MALDI plate (Applied Biosystems) and air dried. Muropeptides readily form alkaline metal adducts during MALDI MS, where the [M + Na]+ ion is the predominant species (2, 23). The molecular mass can therefore be identified from the [M + Na]+ ion. Mass spectra were acquired in positive- and negative-ion modes, with 800 laser pulses per sample spot. MS/MS CID spectra were acquired in positive- and negative-ion modes, using a 1-kV collision energy and air as the collision gas. The instrument's default calibration parameters for MS and MS/MS modes were updated by acquiring data for six calibration spots. After acquisition of a full spectrum for each sample, CID analysis of selected ions was carried out. In figures, daughter ions are labeled “d” according to the scheme described by Roepstorff and Fohlman (15).

Structural determination of SPITC-labeled muropeptides.

Sulfonation of the N-terminal amino group was performed on muropeptides bound to a Zip-Tip (Millipore, Bedford, MA) solid-phase extraction unit, using SPITC according to the method described by Chen et al. (5). Following elution from the Zip-Tip unit, each sample was dried using a Speed-Vac, mixed with 2 μl of α-cyano-4-hydroxycinnamic acid matrix, and used (0.8 μl) for MS and MS/MS CID analyses in the negative-ion mode as described above.

RESULTS AND DISCUSSION

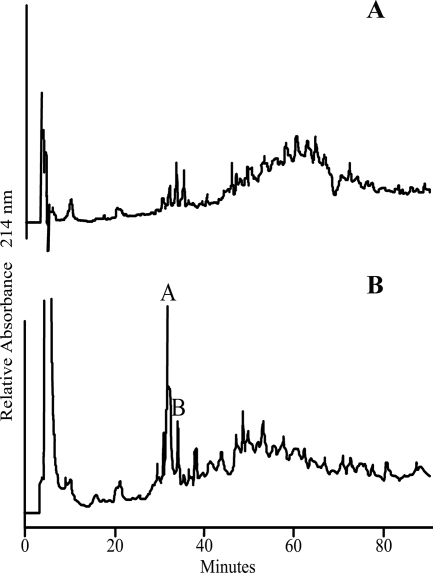

Digestion of sensitive peptidoglycan with zoocin A produced alanyl residues with free N termini, as detected by dansylation (data not shown). This is consistent with zoocin A being an endopeptidase, an N-acetylmuramyl-l-alanine amidase, or both. However, the enzyme did not appear to be an amidase because when peptidoglycan from the zoocin A-sensitive strain 4881.1KOK was digested with zoocin A alone, no fragments small enough for analysis by MS were liberated, presumably because of the intact carbohydrate backbone. Therefore, the muramidase mutanolysin was used both with and without zoocin A to generate muropeptides from strains 4881.1 and 4881.1KOK. As expected, chromatographic profiles of the peptidoglycan fragments from the zoocin A-resistant strain 4881.1 generated with and without zoocin A digestion were essentially the same (data not shown), indicating that resistance of S. equi subsp. zooepidemicus 4881.1 cells is intrinsic to the peptidoglycan. However, chromatographic profiles of the peptidoglycan fragments from the sensitive strain 4881.1KOK generated with and without zoocin A digestion were markedly different (Fig. 2). Fractions corresponding to the peaks at 32 min (peak A) and 34 min (peak B) from the zoocin A digest were collected for analysis by MALDI-TOF MS/MS because they were the largest peaks that appeared after digestion with zoocin A.

FIG. 2.

RP-HPLC chromatograms of 4881.1KOK peptidoglycan digested with the muramidase mutanolysin (A) and 4881.1KOK peptidoglycan digested with mutanolysin and zoocin A (B). Peaks A and B were collected for further analysis.

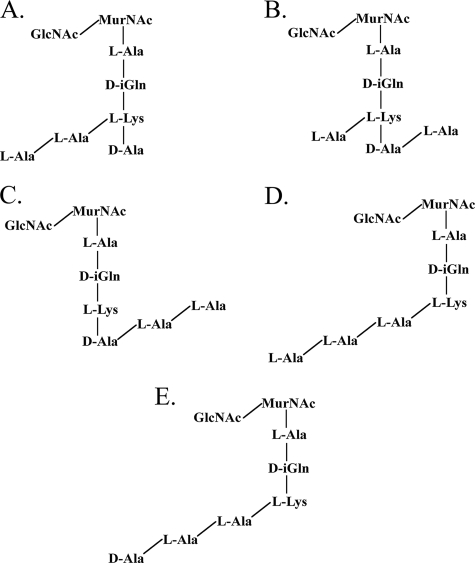

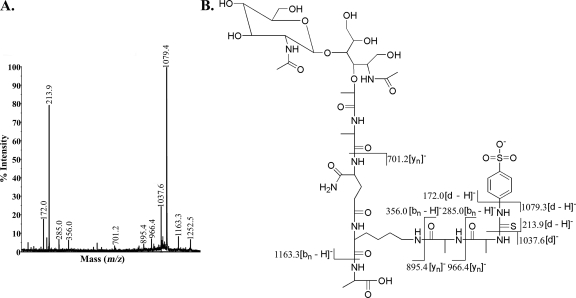

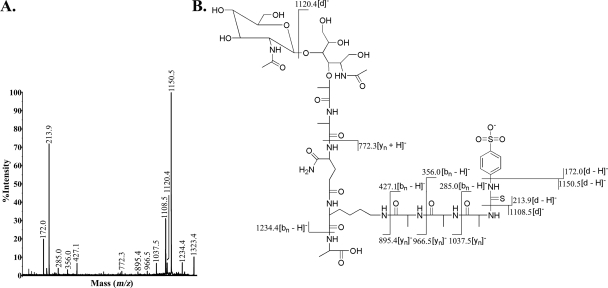

Our compositional analysis of the peptidoglycan of strain 4881.1KOK (Table 1) and MS/MS analysis of the muropeptides in peaks A and B (data not shown) showed that this strain has the typical streptococcal peptidoglycan structure, as shown in Fig. 1. The muropeptide in peak A had m/z values of 1,061.4 in the positive-ion mode and 1,037.4 in the negative-ion mode. However, there are several possible structures (Fig. 3) for the muropeptide in peak A, which represented the most abundant species after digestion with zoocin A. The dansylation experiment revealed that zoocin A activity generated alanines with free amino groups; thus, the muropeptide indicated in Fig. 3C can be eliminated from further consideration because no alanines with free amino groups would be generated by production of this fragment. If there are two alanines in the cross bridge and if zoocin A hydrolyzes the bond between the terminal d-alanine of the tetrapeptide and the first l-alanine of the cross bridge, then the resulting structure would be that shown in Fig. 3A. Alternatively, if zoocin A hydrolyzes the bond between the two l-alanines of the cross bridge, then one l-alanine residue would remain attached to the terminal d-alanine of the tetrapeptide and the other would remain attached to the epsilon amino group of lysine, giving the structure shown in Fig. 3B. The structure in Fig. 3D could be generated if zoocin A acts as a d-alanyl-l-alanine endopeptidase on a cross bridge that contains three alanines attached to a stem peptide missing both terminal d-alanines. The structure in Fig. 3E could be generated if zoocin A hydrolyzes the bond between lysine and d-alanine in the stem peptide and there are two alanines in the cross bridge. In order to determine the structure of the muropeptide in peak A, SPITC was used to label free amino groups in the muropeptide. The negative-ion-mode MS/MS CID spectrum of the SPITC-labeled muropeptide (m/z 1,252.5) is shown in Fig. 4A. The other peaks correspond to fragmentation within the label (1,079.4 and 172.0), between the label and the first alanine (1,037.6 and 213.9), between the two alanines (966.4 and 285.0), and between the alanine and the lysine (895.4 and 356.0). Therefore, two alanines are connected to the epsilon amino group of lysine. Also, the presence of an ion at m/z 1,163.3 (SPITC-labeled muropeptide less an alanyl group) and the absence of ions at m/z 1,092.3 (labeled muropeptide less a dialanyl group) showed that there was only one alanine connected to the carboxy side of the lysine. The corresponding structure is shown in Fig. 3A and 4B. The production of this muropeptide by zoocin A digestion indicated that the enzyme is a d-alanyl-l-alanine endopeptidase.

TABLE 1.

Peptidoglycan compositions of Streptococcus equi subsp. zooepidemicus 4881.1 and 4881.1KOK

| Strain | Molar ratioa

|

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Lys | Glx | Ala | Mur | GlcN | |

| 4881.1 | 1.00 | 0.97 | 3.80 | 0.82 | 1.08 |

| 4881.1KOK | 1.00 | 0.97 | 3.89 | 0.85 | 1.06 |

The amount of each compound is expressed as a molar ratio relative to lysine. Values shown are the averaged results from two separate analyses. Mur, muramic acid; GlcN, glucosamine.

FIG. 3.

Possible structures for the muropeptide in peak A ([M + Na]+, 1,061.4; [M − H]−, 1,037.4), which represented the most abundant species after digestion with zoocin A.

FIG. 4.

(A) MALDI-tandem TOF CID analysis of the muropeptide in peak A labeled with SPITC ([M − H]−, 1,252.5) in the negative-ion mode. (B) Structure of the muropeptide in peak A labeled with SPITC. All masses have been rounded to the nearest 10th of an integer.

The muropeptide in peak B had m/z values of 1,132.5 in the positive-ion mode and 1,108.5 in the negative-ion mode. This corresponds to the muropeptide in peak A with an additional alanyl residue. Possible structures for this muropeptide are shown in Fig. 5. As with the structure in Fig. 3C, the muropeptide indicated in Fig. 5D can be eliminated from further consideration because no alanines with free amino groups would be generated by production of this fragment. SPITC labeling was used to identify the structure of the muropeptide in peak B. The MS/MS CID spectrum in the negative-ion mode for the SPITC-labeled muropeptide in peak B (m/z 1,323.4) is shown in Fig. 6A. The other peaks correspond to fragmentation within the label (1,150.5 and 172.0), between the label and the first alanine (1,108.5 and 213.9), between the first and second alanines (1,037.5 and 285.0), between the second and third alanines (966.5 and 356.0), and between the third alanine and the lysine (895.4 and 427.1). Therefore, in the muropeptide in peak B, three alanines are connected to the epsilon amino group of lysine. Also, as described above, the presence of an ion at m/z 1,234.4 (SPITC-labeled muropeptide less an alanyl group) and the absence of ions at m/z 1,163.4 (labeled muropeptide less a dialanyl group) showed that there was only one alanine connected on the carboxy side of the lysine. The corresponding structure is shown in Fig. 5A and 6B. This confirmed that zoocin A is a d-alanyl-l-alanine endopeptidase.

FIG. 5.

Possible structures for the muropeptide in peak B ([M + Na]+, 1,132.5; [M − H]−, 1,108.5), which represented the second most abundant species after digestion with zoocin A.

FIG. 6.

(A) MALDI-tandem TOF CID analysis of the muropeptide in peak B labeled with SPITC ([M − H]−, 1,323.4) in the negative-ion mode. (B) Structure of the muropeptide in peak B labeled with SPITC. All masses have been rounded to the nearest 10th of an integer.

Related enzymes, such as lysostaphin (21), ALE-1 (22), LytM (14), and millericin B (3), hydrolyze within peptidoglycan cross bridges. In contrast, zoocin A hydrolyzes at the junction between the d-alanine of the stem peptide and the first l-alanine of the cross bridge.

MS/MS analysis in the positive-ion mode of N-terminally SPITC-labeled peptides has been used for amino acid sequencing because the additional negative charge added to the peptide suppresses detection of the ions that contain SPITC and thereby enhances detection of ions that do not contain SPITC (5, 10). However, in the present study, when peptidoglycan fragments were labeled with SPITC and analyzed in the negative-ion mode, both SPITC-labeled and unlabeled ions were detected. The negative charge actually facilitated detection of the SPITC-labeled ions. Detecting both types of ions would normally be a hindrance in protein sequencing, but in the present study the detection of both aided in the determination of the alanine arrangement in the muropeptides because of the SPITC label on the N-terminal residue of the cross bridge. Frequently, the number and type of amino acids in peptidoglycan cross bridges are determined using Edman degradation, which requires relatively large amounts of purified product (2, 7, 12, 17, 18). MS/MS analysis of SPITC-labeled muropeptides requires less material of lower purity because specific ions can be selected for analysis. SPITC labeling and MS/MS analysis can be used to determine the sites of action of peptidoglycan hydrolases, as was done in this study. This technique can also be used to analyze amino acid sequences of peptidoglycans after digestion with appropriate hydrolases or growth in the presence of sublethal concentrations of penicillin to inhibit cross-bridge formation. The present study, which determined the site of action of zoocin A, is the first report of the use of SPITC labeling to determine the arrangement of amino acids in peptidoglycan.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by grant R03AI073412 (to G.L.S.) from the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases and by a Fulbright grant to S.R.G.

The content of this work is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases or the National Institutes of Health.

We thank Torsten Kleffman of the Centre for Protein Research in the Department of Biochemistry at the University of Otago, Dunedin, New Zealand, for his assistance with the MS analyses and Ralph Jack of the Department of Microbiology at the University of Otago for the use of his HPLC instrument and for assistance with data interpretation.

Footnotes

Published ahead of print on 31 October 2008.

REFERENCES

- 1.Beatson, S. A., G. L. Sloan, and R. S. Simmonds. 1998. Zoocin A immunity factor: a femA-like gene found in a group C streptococcus. FEMS Microbiol. Lett. 163:73-77. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Beranova-Giorgianni, S., D. M. Desiderio, and M. J. Pabst. 1998. Structures of biologically active muramyl peptides from peptidoglycan of Streptococcus sanguis. J. Mass Spectrom. 33:1182-1191. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Beukes, M., and J. W. Hastings. 2001. Purification and partial characterization of a murein hydrolase, millericin B, produced by Streptococcus milleri NMSCC 061. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 67:3888-3896. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bouhss, A., N. Josseaume, A. Severin, K. Tabei, J. E. Hugonnet, D. Shlaes, D. Mengin-Lecreulx, J. van Heijenoort, and M. Arthur. 2002. Synthesis of the l-alanyl-l-alanine cross-bridge of Enterococcus faecalis peptidoglycan. J. Biol. Chem. 277:45935-45941. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Chen, P., S. Nie, W. Mi, X. C. Wang, and S. P. Liang. 2004. De novo sequencing of tryptic peptides sulfonated by 4-sulfophenyl isothiocyanate for unambiguous protein identification using post-source decay matrix-assisted laser desorption/ionization mass spectrometry. Rapid Commun. Mass Spectrom. 18:191-198. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Farris, M. H., L. S. Heath, H. E. Heath, P. A. LeBlanc, R. S. Simmonds, and G. L. Sloan. 2003. Expression of the genes for lysostaphin and lysostaphin resistance in streptococci. FEMS Microbiol. Lett. 228:115-119. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Filipe, S. R., and A. Tomasz. 2000. Inhibition of the expression of penicillin resistance in Streptococcus pneumoniae by inactivation of cell wall muropeptide branching genes. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 97:4891-4896. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Heath, L. S., H. E. Heath, P. A. LeBlanc, S. R. Smithberg, M. Dufour, R. S. Simmonds, and G. L. Sloan. 2004. The streptococcolytic enzyme zoocin A is a penicillin-binding protein. FEMS Microbiol. Lett. 236:205-211. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Lai, A. C.-Y., S. Tran, and R. S. Simmonds. 2002. Functional characterization of domains found within a lytic enzyme produced by Streptococcus equi subsp. zooepidemicus. FEMS Microbiol. Lett. 215:133-138. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Marekov, L. N., and P. M. Steinert. 2003. Charge derivatization by 4-sulfophenyl isothiocyanate enhances peptide sequencing by post-source decay matrix-assisted laser desorption/ionization time-of-flight mass spectrometry. J. Mass Spectrom. 38:373-377. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Navarre, W. W., and O. Schneewind. 1999. Surface proteins of gram-positive bacteria and mechanisms of their targeting to the cell wall envelope. Microbiol. Mol. Biol. Rev. 63:174-229. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Navarre, W. W., H. Ton-That, K. F. Faull, and O. Schneewind. 1999. Multiple enzymatic activities of the murein hydrolase from staphylococcal phage Φ11. J. Biol. Chem. 274:15847-15856. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Perez-Casa, J., M. G. Caparon, and J. R. Scott. 1991. Mry, a trans-acting positive regulator of the M protein gene of Streptococcus pyogenes with similarity to the receptor proteins of two-component systems. J. Bacteriol. 173:2617-2624. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ramadurai, L., and R. K. Jayaswal. 1997. Molecular cloning, sequencing, and expression of lytM, a unique autolytic gene of Staphylococcus aureus. J. Bacteriol. 179:3625-3631. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Roepstorff, P., and J. Fohlman. 1984. Proposal for a common nomenclature for sequence ions in mass spectra of peptides. Biomed. Mass Spectrom. 11:601. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Schleifer, K. H., and O. Kandler. 1972. Peptidoglycan types of bacterial cell walls and their taxonomic implication. Bacteriol. Rev. 36:407-477. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Severin, A., S. W. Wu, K. Tabei, and A. Tomasz. 2005. High-level β-lactam resistance and cell wall synthesis catalyzed by the mecA homologue of Staphylococcus sciuri introduced into Staphylococcus aureus. J. Bacteriol. 187:6651-6658. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Severin, A., and A. Tomasz. 1996. Naturally occurring peptidoglycan variants of Streptococcus pneumoniae. J. Bacteriol. 178:168-174. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Simmonds, R. S., J. Naidoo, C. L. Jones, and J. R. Tagg. 1995. The streptococcal bacteriocin-like inhibitory substance, zoocin A, reduces the proportion of Streptococcus mutans in an artificial plaque. Microb. Ecol. Health Dis. 8:281-292. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Simmonds, R. S., L. Pearson, R. C. Kennedy, and J. R. Tagg. 1996. Mode of action of a lysostaphin-like bacteriolytic agent produced by Streptococcus zooepidemicus 4881. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 62:4536-4541. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Simmonds, R. S., W. J. Simpson, and J. R. Tagg. 1997. Cloning and sequence analysis of zooA, a Streptococcus zooepidemicus gene encoding a bacteriocin-like inhibitory substance having a domain structure similar to that of lysostaphin. Gene 189:255-261. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Sugai, M., T. Fujiwara, T. Akiyama, M. Ohara, H. Komatsuzawa, S. Inoue, and H. Suginaka. 1997. Purification and molecular characterization of glycylglycine endopeptidase produced by Staphylococcus capitis EPK1. J. Bacteriol. 179:1193-1202. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Xu, N., Z. H. Huang, B. L. de Jonge, and D. A. Gage. 1997. Structural characterization of peptidoglycan muropeptides by matrix-assisted laser desorption ionization mass spectrometry and postsource decay analysis. Anal. Biochem. 248:7-14. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]