Abstract

Bacillus anthracis strains harboring virulence plasmid pXO1 that encodes the toxin protein protective antigen (PA), lethal factor, and edema factor and virulence plasmid pXO2 that encodes capsule biosynthetic enzymes exhibit different levels of virulence in certain animal models. In the murine model of pulmonary infection, B. anthracis virulence was capsule dependent but toxin independent. We examined the role of toxins in subcutaneous (s.c.) infections using two different genetically complete (pXO1+ pXO2+) strains of B. anthracis, strains Ames and UT500. Similar to findings for the pulmonary model, toxin was not required for infection by the Ames strain, because the 50% lethal dose (LD50) of a PA-deficient (PA−) Ames mutant was identical to that of the parent Ames strain. However, PA was required for efficient s.c. infection by the UT500 strain, because the s.c. LD50 of a UT500 PA− mutant was 10,000-fold higher than the LD50 of the parent UT500 strain. This difference between the Ames strain and the UT500 strain could not be attributed to differences in spore coat properties or the rate of germination, because s.c. inoculation with the capsulated bacillus forms also required toxin synthesis by the UT500 strain to cause lethal infection. The toxin-dependent phenotype of the UT500 strain was host phagocyte dependent, because eliminating Gr-1+ phagocytes restored virulence to the UT500 PA− mutant. These experiments demonstrate that the dominant virulence factors used to establish infection by B. anthracis depend on the route of inoculation and the bacterial strain.

The major virulence factors of Bacillus anthracis include two toxins and the poly-d-γ-glutamic acid (PGA) capsule (10, 24, 27, 46). The toxins are composed of three polypeptides, lethal factor (LF), edema factor (EF), and protective antigen (PA), which are encoded noncontiguously on plasmid pXO1 (36). The LF and EF polypeptides form complexes with the receptor-binding PA heptamer to generate lethal toxin (LT) and edema toxin (ET), respectively (6). The PGA capsule biosynthetic enzymes are encoded on plasmid pXO2 (18). Genetically complete (pXO1+ pXO2+) B. anthracis strains persist as endospores in the environment and are stable for years in this form. When they have access to an appropriate environment, such as inside a susceptible host, the dormant endospores germinate and transform into capsulated, toxin-producing, and rapidly replicating vegetative bacilli (19). The toxins modulate host immune responses to promote bacterial survival and together with the PGA capsule are responsible for anthrax-related pathogenesis (12, 34, 35).

The common routes of entry for B. anthracis are cutaneous, gastrointestinal, and pulmonary, and cutaneous infection is the most common route in humans (10, 24, 27). The outcome of infection varies with the route of entry, and pulmonary anthrax is the most lethal form (10, 24, 46). The exact mechanisms that determine the outcome for a given infection route remain unclear, but they are likely related to both the strain of B. anthracis and host cellular and anatomical differences at the site of infection. Various mouse models of B. anthracis infection have been developed in order to help us understand anthrax pathogenesis, host immune responses, and B. anthracis virulence mechanisms (4, 30, 49, 51). Pulmonary anthrax in mice is produced by delivering B. anthracis into the lung by aerosolization or by intranasal or intratracheal (i.t.) inoculation (8, 9, 21, 22, 29, 30). Other routes used for experimental infection are subcutaneous (s.c.) (30, 49) and intravenous (i.v.) inoculation, and the latter is used to mimic the systemic phase of infection (13, 23).

Advances in genetic tools and reagents and development of experimental animal models have improved our understanding of anthrax virulence and pathogenesis (4, 12, 13, 23, 37, 38, 44, 51, 52). An examination of genetically complete B. anthracis strain UT500 and isogenic mutants of this strain using the murine model of pulmonary anthrax produced the surprising result that toxin production was not required for virulence of strain UT500 in murine models of pulmonary and systemic infections (23, 48). In contrast, toxin-producing acapsular isogenic mutants of the UT500 strain were completely attenuated in a murine pulmonary infection model (12), demonstrating that capsule is the dominant virulence factor in murine pulmonary anthrax. The latter results were consistent with the results of previous studies utilizing plasmid-cured derivatives of genetically complete B. anthracis strains that showed that there was a significant decrease in the virulence of toxigenic acapsular pXO1+ pXO2− derivatives compared to the virulence of nontoxigenic capsular pXO1− pXO2+ derivatives for a murine s.c. infection (48, 51). Thus, toxigenic acapsular derivatives of the Ames and Vollum 1B strains had significantly higher 50% lethal doses (LD50s) than nontoxigenic capsular derivatives (51). It is important to note that these studies used strains lacking entire virulence plasmids; thus, other plasmid-encoded genes could have impacted these studies as well (48, 51).

Variations in virulence among B. anthracis strains or isolates that are genetically monomorphic have been described previously (5, 28, 45, 51). Very little is known about the mechanisms responsible for variations in virulence among B. anthracis strains. In the current study, we compared two genetically complete virulent strains of B. anthracis, strains UT500 and Ames, that were inoculated into mice using the s.c. route and we analyzed the role of toxins in causing a lethal infection. The data obtained demonstrate that the B. anthracis Ames strain exhibits “toxin-independent” virulence mechanisms in mice, whereas the UT500 strain requires toxin production for virulence after s.c. infection of BALB/c mice. Similar results were obtained with the C57BL mouse strain. These results suggest that the s.c. mouse model may be an excellent model for evaluating and detecting differences in virulence phenotypes among site-directed isogenic mutants of B. anthracis.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Animals.

Female 7- to 8-week-old BALB/c, C57BL/6, and C57BL/10 mice were purchased from Harlan Sprague-Dawley (Indianapolis, IN) and maintained in a specific-pathogen-free animal research facility at the University of New Mexico. In our experimental setting for s.c infection, the LD50s for the C57BL/6 and C57BL/10 substrains were similar; hence, these substrains were used interchangeably depending on availability and are referred to here as C57BL mice. The mice were housed in cages with HEPA filters (Tecniplast, Phoenixville, PA) containing autoclaved Tek-Fresh bedding (Harlan Teklad, Madison, WI); each cage contained five mice. Mice had access to irradiated food (Harlan Teklad Global 18% protein rodent diet) and autoclaved, acidified (pH 2.6) water ad libitum to help prevent any waterborne microbial contamination. Animals were allowed to acclimate to their surroundings for 1 week prior to use. All protocols were approved by the UNMHSC Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee.

B. anthracis strains.

The Ames strain used was originally obtained from the U.S. Army Medical Research Institute of Infectious Diseases, Frederick, MD. The UT500 strain (pXO1+ pXO2+) and isogenic mutants, including a UT500 LF-deficient (LF−) mutant (UT539), a UT500 EF-deficient (EF−) mutant (UT540), and a UT500 PA-deficient (PA−) mutant (NM-1), were constructed in Theresa Koehler's lab as described previously (23), and the lab-assigned names are indicated in parentheses. Isogenic toxin-deficient mutants with the Ames background, including an Ames EF− mutant (UTA1), an Ames LF− mutant (UTA2), and an Ames PA− mutant (UTA3), were constructed using a similar strategy, and the lab-assigned names are indicated in parentheses. Briefly, the individual mutants were constructed by replacing the coding sequences of the EF, LF, or PA genes with an omega-kanamycin resistance gene cassette to help with screening of the mutants generated.

The toxin-deficient phenotypes were confirmed by performing Western blot analyses of supernatants from cultures grown under conditions that promote toxin and capsule synthesis (11). Blots were probed using antibodies against EF, LF, and PA to demonstrate the absence of the appropriate protein from the corresponding mutant (data not shown). Deletion of toxin component genes was also confirmed using a quantitative reverse transcription-PCR assay (TaqMan assay; Applied Biosystems) designed specifically for each gene (data not shown).

Reagents.

The RB6-8C5 (anti-Gr-1) monoclonal antibody (MAb) hybridoma was a gift from Hattie Gresham (University of New Mexico Health Sciences Center, Albuquerque, NM) (originally from R. Coffman, DNAX Research Institute, Palo Alto, CA). The SFR8-B6 hybridoma (anti-HLA-Bw6) was obtained from the American Type Culture Collection (HB-152). The antibodies were purified using a Montage antibody purification Prosep-G kit (Millipore Corp., Bedford, MA), concentrated with Amicon Ultra-15 (nominal molecular weight limit, 30,000) centrifugal filter devices (Millipore Corp., Bedford, MA), and stored at −20°C in 1-ml aliquots. The purity of antibody preparations was >99%, as evaluated by standard sodium dodecyl sulfate-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis analysis, and the protein concentrations were assessed by measuring the extinction coefficient (E1%) at 280 nm using an E1% value of 14 for immunoglobulin G molecules. All other chemical reagents used were commercial grade.

Spore preparation.

Spores were prepared as described previously (18, 25). Briefly, spore stocks were streaked onto nutrient broth yeast agar plates containing 0.8% bicarbonate (NBY-NaHCO3) that was supplemented with 50 μg/ml kanamycin only for mutants and were grown overnight in the presence of 10% CO2 at 37°C. After overnight growth three colonies were inoculated into 50 ml of phage assay medium in a 500-ml vented-cap flask to ensure that there was active culture inoculation of the desired mutant strain and were grown at 200 rpm and 30°C for 5 to 7 days. The final cultures were heated at 68°C for 40 min to kill any remaining vegetative cells and then washed, resuspended in phosphate-buffered saline, aliquoted, and frozen at −80°C. The purity and extent of sporulation were assessed by phase-contrast microscopy of India ink-stained spore preparations and also by determining the number of CFU grown from heated (68°C for 40 min) and nonheated aliquots. All the spore preparations consisted of 100% spores as assessed by these methods. The titers were determined by plating serial dilutions onto blood agar plates (Remel Inc., Lenexa, KS) using an Autoplate 4000 spiral plating system (Spiral Biotech, Norwood, MA) and a QCount colony counter (Spiral Biotech, Norwood, MA).

Preparation of B. anthracis vegetative bacilli for infection.

B. anthracis vegetative bacilli were prepared as described previously (18, 25). Briefly, spores were plated onto NBY-NaHCO3 plates as described above. A few colonies from each plate were used to inoculate 15 ml of Luria-Bertani broth with 0.5% glycerol and 50 μg/ml kanamycin (only for mutants) and grown overnight at 200 rpm and 30°C in air. Bacteria were subcultured in NBY-NaHCO3 using an initial optical density at 600 nm (OD600) of 0.1 and were grown at 37°C with 10% CO2 at 200 rpm to an OD600 of approximately 0.4. At this OD600, all cultures contained vegetative B. anthracis bacilli at a concentration of ∼107 CFU/ml. The bacteria were resuspended in phosphate-buffered saline to obtain a volume equivalent to the original culture volume, and aliquots were plated onto blood agar plates to obtain the inoculating doses.

Mouse infection.

All infections were carried out in an animal biological safety level 3 containment area. s.c. infection, i.t infection, and i.v. infection were performed as described previously (23, 30). Briefly, for s.c. infection, isoflurane-anesthetized mice were inoculated with 200 μl of an inoculum containing either spores or vegetative bacilli in the dorsal subcapular region using a 27-gauge needle attached to a 1-ml syringe. For i.t. infection, mice were anesthetized with avertin (2,2,2-tribromoethanol), a small incision was made through the skin over the trachea, and the underlying tissue was separated. A 50-μl inoculum was delivered into the lung using a 30-gauge needle inserted into the trachea. For i.v. infection, each mouse was infected with 100 μl of vegetative bacilli using a 30-gauge needle via the tail vein. Initially, after inoculation three random mice were euthanized and the infection sites (skin for s.c. infection and lungs for i.t. infection) were excised and cultured to determine that the number of B. anthracis deposited was ≥90% of the bacteria inoculated.

LD50 and MTD calculation.

LD50s were calculated using the method of Reed and Muench (41) and were expressed as log10 values. The experimental data shown below are averages of at least two independent experiments in which ≥6 mice per group were used. The mean time to death (MTD) was calculated for each individual mutant with a dose greater than 10 times the LD50 (10× LD50) as described previously (30).

Depletion of Gr-1+ cells in mice.

Mice were rendered neutropenic by intraperitoneally administering 100 μg of anti-Gr-1 (RB6-8C5) antibody per mouse on days −1, 2, and 4 of infection (7, 13). Control mice received an equivalent amount of an irrelevant rat immunoglobulin G2b isotype control MAb (SFR8-B6) (40). Polymorphonuclear granulocyte (PMN) depletion was confirmed 24 h after anti-Gr-1 administration by performing a complete blood count analysis (Forcyte; Oxford Science Inc., Oxford, CT) for mice receiving anti-Gr-1 antibody, and the results were compared to the results for mice receiving the isotype control antibody. Based on this quantitative assessment, there was a 10-fold decrease in the absolute blood neutrophil count. There were only 20.0 ± 4.1 PMN s/μl in anti-Gr-1-treated mice, compared to 197.5 ± 22.5 PMN s/μl in isotype-treated mice (n = 4; P = 0.0002), and the PMN levels ranged from 100 to 2,400 cells per μl in normal mice. No changes were observed in the other leukocyte levels; specifically, the monocyte levels were 42.5 ± 10.3 cells per μl of blood in isotype-treated mice and 35.0 ± 13.7 cells per μl of blood in anti-Gr-1-treated mice (n = 4).

Statistical analysis.

A one-way analysis of variance was performed to compare the LD50s of all strains, and a pairwise comparison was performed using the Student t test. Data were processed using GraphPad PRISM 4.0 software (Graph-Pad Software, Inc., San Diego, CA) to generate graphs and for statistical analyses. Comparisons among multiple groups of nonparametric data were statistically evaluated by performing Kaplan-Meier and log rank post hoc test analyses. Differences were considered statistically significant if the P value was <0.05.

RESULTS

The virulence of the Ames strain and the virulence of the UT500 strain are comparable for mouse s.c. infection.

Previous studies performed in our lab demonstrated that there was no significant difference between the virulence of the Ames strain and the virulence of the UT500 strain in pulmonary infection of mice (12). Therefore, we determined the LD50s of these two strains for the s.c. infection in mice. Infection with the Ames strain and infection with the UT500 strain were compared in terms of morbidity and mortality in two strains of mice, BALB/c and C57BL. The s.c. LD50s of the Ames strain were 1.34 log10 CFU for BALB/c mice and 1.56 log10 CFU for C57BL mice. The s.c. LD50s of the UT500 strain were 1.63 log10 CFU for BALB/c mice and 2.17 log10 CFU for C57BL mice. Thus, there were no significant differences between the virulence of the Ames strain and the virulence of the UT500 strain in either mouse strain. Depending on the number of spores administered, mice began to die as early as day 2 and as late as day 8, and the majority of mice died on days 3 and 4. Most of the mice developed clinical symptoms that included a gradual decrease in activity, increased ruffling, and edematous swelling around the site of inoculation.

In addition, when 10× LD50 was used, there was no significant difference between the MTD of BALB/c mice infected with the UT500 strain (4.2 days) and the MTD of BALB/c mice infected with the Ames strain (3.7 days) or between the MTD of C57BL mice infected with the UT500 strain (3.1 days) and the MTD of C57BL mice infected with the Ames strain (2.7 days). However, the infected C57BL mice died a day earlier than the BALB/c mice.

The virulence of the Ames strain in mice is toxin independent for i.t., i.v., and s.c. infections.

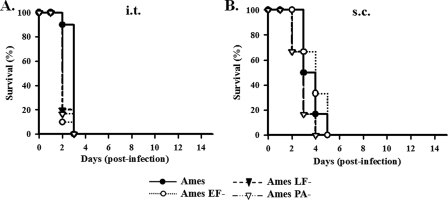

We evaluated the virulence of isogenic toxin-deficient mutants of the Ames strain (i.e., mutants lacking the ET [Ames EF−], the LT [Ames LF−], or both toxins [Ames PA−]) for all routes of infection in mice. For pulmonary infection, spores of the parent Ames strain or the toxin-deficient mutants were inoculated i.t. using identical infection doses (equivalent to 10× LD50 of the parent Ames strain). Death due to pulmonary infection with the Ames strain did not rely on toxin expression in BALB/c mice (Fig. 1A). To mimic systemic infection, vegetative forms of toxin-deficient mutants and the parent Ames strain were inoculated i.v. All of the infected mice succumbed to infection by 20 h postinoculation irrespective of the mutant administered (data not shown).

FIG. 1.

Survival of BALB/c mice after pulmonary (i.t.) and s.c. administration of the B. anthracis Ames strain and isogenic toxin-deficient mutants of this strain. (A) Approximately 10× LD50 of the parent Ames strain dose was administered i.t. (10 mice/group). There were no significant differences among the four survival curves (P > 0.05). (B) Mice (10 mice/group) were infected s.c. with 100× LD50 of the parent Ames strain dose. Mice infected with the wild-type Ames strain or isogenic toxin-deficient mutants of this strain exhibited no significant differences (P > 0.05) in survival regardless of whether the infecting microbial mutant was capable of making one toxin (Ames EF− or Ames LF−) or neither toxin (Ames PA−).

For s.c. infection, identical doses of each mutant strain (equivalent to 100× LD50 of the parent Ames strain) were administered s.c. to BALB/c mice. Similar to the results for the i.t. and i.v. routes of infection, the Ames toxin-deficient mutants exhibited virulence comparable to that of the parent Ames strain for s.c. infection. All infected mice died by day 5 irrespective of the mutant administered (Fig. 1B). Furthermore, additional experiments performed to determine the LD50 of each of the Ames toxin-deficient mutants revealed no significant difference between the LD50s for s.c. infection with the Ames toxin-deficient mutants and the LD50 for s.c. infection with the parent Ames strain (Table 1). Thus, all the toxin-deficient mutants of the Ames strain were as virulent as the parent Ames strain in mice for all routes of infection examined.

TABLE 1.

LD50s for s.c. infection with isogenic toxin-deficient mutants of the Ames and UT500 strains using spores and vegetative bacillia

| Strain | LD50 (log10 CFU)

|

|

|---|---|---|

| BALB/c mice | C57BL mice | |

| Spores | ||

| Ames | 1.34 | ND |

| Ames EF− | 1.40 | ND |

| Ames LF− | 1.34 | ND |

| Ames PA− | 1.48 | ND |

| UT500 | 1.63 ± 0.47 | 2.17 ± 0.24 |

| UT500 EF− | 1.48 ± 0.47 | 1.28 ± 0.71c |

| UT500 LF− | 2.61 ± 1.05 | 1.31 ± 0.23c |

| UT500 PA− | 5.75 ± 0.39b | 5.65 ± 0.07c |

| Bacilli | ||

| Ames | 0.26 ± 0.12 | ND |

| Ames PA− | −0.01 ± 0.12 | ND |

| UT500 | 1.20 ± 0.42 | ND |

| UT500 PA− | 5.65 ± 0.36d | ND |

The LD50s are the values from one experiment for spores of the Ames strain and mutants and are the means ± standard deviations of at least two different experiments for spores of the UT500 strain and mutants and for vegetative bacilli of both the Ames and UT500 strains and mutants. In each experiment there were three or more groups (≥6 mice/group) of mice that received three to five different doses. ND, not determined.

P < 0.05 for UT500 PA− versus UT500 in BALB/c mice.

P < 0.05 for UT500 EF− and UT500 LF− versus UT500 and P < 0.005 for UT500 PA− versus UT500 in C57BL mice.

P < 0.0001 for UT500 versus UT500 PA− bacilli.

The virulence of the UT500 strain is toxin dependent for s.c. infection.

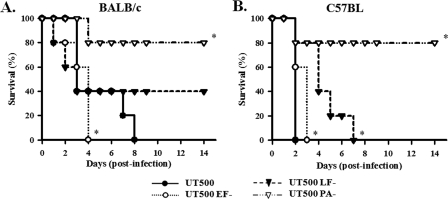

For the UT500 strain and its derivatives, we showed previously that all of the isogenic toxin-deficient UT500 mutants were as virulent as the parent UT500 strain in both pulmonary and systemic infections (23). We assessed the impact of eliminating toxins on the ability of the UT500 strain to cause a lethal infection via s.c. inoculation. Identical doses of each mutant strain (equivalent to 100× LD50 of the parent UT500 strain) were administered s.c. to BALB/c and C57BL mice. In contrast to the Ames PA− mutant, the nontoxigenic UT500 PA− mutant was significantly attenuated compared to the parent UT500 strain, and infection with this mutant resulted in only 20% mortality in the two mouse strains (Fig. 2A and 2B). In addition, there were small, yet significant differences among the survival curves for the single-toxin-deficient UT500 mutants. For BALB/c mice, the mice infected with the UT500 EF− mutant died significantly faster than the mice infected with the parent UT500 strain (Fig. 2A). BALB/c mice infected with the UT500 LF− mutant exhibited only 60% mortality, compared to the 100% mortality of mice infected with the parent UT500 strain (Fig. 2A). For C57BL mice, there were no survivors among mice infected with either the UT500 EF− or UT500 LF− mutant; however, the survival curves were significantly different from each other and also from that observed for the parent UT500 strain (Fig. 2B). For the two mouse strains, the survival curves obtained for the UT500 (P < 0.0001) and UT500 EF− (P < 0.05) strains were significantly different, and the C57BL mice died faster.

FIG. 2.

Survival of BALB/c and C57BL mice following s.c. administration of the B. anthracis UT500 strain and isogenic toxin-deficient mutants of this strain. Approximately 100× LD50 of the UT500 parent strain dose was administered to the members of each group (≥6 mice/group). (A) BALB/c mice infected with the UT500 strain or isogenic toxin-deficient mutants exhibited significant differences in survival when the effect of the parent UT500 strain was compared to the effect of either the UT500 EF− mutant or the UT500 PA− mutant (P < 0.05), but there was no significant difference in survival when the effect of UT500 was compared with the effect of the UT500 LF− mutant (P > 0.05). The survival curve for the EF− mutant was not significantly different from that for the LF− mutant (P = 0.139). However, in the case of the EF− mutant, the survival curve indicated that it was more, rather than less, virulent than the parent UT500 strain. (B) C57BL mice infected with the parent UT500 strain or isogenic toxin-deficient mutants of this strain exhibited significant differences in survival when the effect of the UT500 strain was compared to the effect of the UT500 EF− (P < 0.005), UT500 LF− (P < 0.0001), or UT500 PA− (P < 0.0005) mutant, and there was also a difference between the effects of the UT500 EF− and UT500 LF− mutants (P < 0.0005). For the two mouse strains, the survival curves for mice infected with UT500 (P < 0.0001) and mice infected with UT500 EF− (P < 0.05) were significantly different.

To further define and quantitate the virulence phenotypes associated with the toxin-deficient mutants of the UT500 strain, the s.c. LD50s were determined for both BALB/c and C57BL mice. For the toxin-deficient mutants of the UT500 strain, there was no significant difference between the LD50 of the UT500 strain and the LD50 of either the EF− or LF− mutant in BALB/c mice (Table 1). Nonetheless, in C57BL mice, the LD50s of both the EF− and LF− mutants were significantly less than the LD50 of the parent UT500 strain. However, in both mouse strains, the LD50 of the nontoxigenic UT500 PA− mutant was 4 logs greater than the LD50 of the parent UT500 strain (Table 1). Thus, the lack of both toxins as a result of PA deletion significantly attenuated the UT500 strain in an s.c. infection.

The toxin-dependent virulence of UT500 does not depend on infection with spore forms.

It was possible that the difference between the toxin-dependent virulence of the UT500 strain and the toxin-dependent virulence of the Ames strain was related to an intrinsic difference in the way that the host responds to spores of the two B. anthracis strains. In order to assess this possibility, we tested the virulence of toxin-deficient mutants along with that of parent strains using s.c inoculation of vegetative bacilli. Fully capsulated mid-log-phase vegetative bacilli of the Ames strain, the Ames PA− mutant, the UT500 strain, and the UT500 PA− mutant were inoculated s.c. into BALB/c mice, and the LD50s were determined. Similar to the findings for infection with spores, infection with bacillus forms revealed that the LD50 of the UT500 PA− mutant was 4 logs greater than that of the parent UT500 strain and also that the Ames PA− mutant was as virulent as the parent Ames strain (Table 1). These data suggest that the phenotypic difference between the two strains is not related to differences in spore composition or the rate of germination.

Gr-1+ host phagocytes are required for the toxin-dependent virulence of UT500.

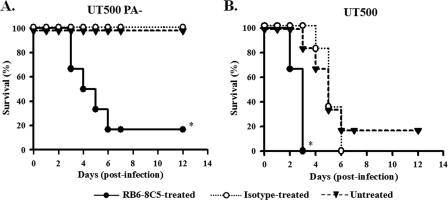

We questioned whether the toxin-dependent virulence of UT500 was associated with the ability to survive a phagocyte response at the s.c. site of infection, because phagocytes have been implicated in limiting B. anthracis infections (20, 32, 50). Therefore, we depleted Gr-1+ phagocytes prior to infection with UT500 and the toxin-deficient UT500 PA− mutant using an anti-Gr-1 rat MAb (RB6-8C5), which targets predominantly neutrophils (17). For controls, mice were treated with an irrelevant isotype-matched rat antibody (SFR8-B6). Mice were infected with UT500 or UT500 PA− mutant spores by using approximately 104 CFU, which is a nonlethal dose for the UT500 PA− mutant. Untreated or isotype-treated mice survived infection with the UT500 PA− mutant and exhibited no clinical signs of infection (Fig. 3A). However, the anti-Gr-1-treated mice infected with the UT500 PA− mutant appeared to be sick on day 2, and 5/6 mice died by day 6. As expected, with the parent UT500 strain, untreated, isotype-treated, and anti-Gr-1-treated mice all succumbed to infection, although the anti-Gr-1-treated mice died significantly faster than the untreated or the isotype-treated mice (Fig. 3B).

FIG. 3.

Survival of BALB/c mice following s.c. challenge with the UT500 PA− and UT500 strains after Gr-1+ phagocyte depletion. (A) Groups of mice (six mice/group) were left untreated or were inoculated with either anti-Gr-1 (RB6-8C5) MAb or isotype control antibody and infected with 3,110 CFU of the UT500 PA− mutant. The P value was <0.05 for a comparison of anti-Gr-1-treated (RB6-8C5) and untreated or isotype control groups. (B) Groups of mice (six mice/group) were left untreated or were treated with either RB6-8C5 or isotype control antibody and infected with 2,072 CFU of the parent UT500 strain. The P value was <0.005 for a comparison of the anti-Gr-1-treated (RB6-8C5) curves and the untreated and isotype control group curves.

To further define the impact of Gr-1+ phagocyte depletion on the virulence of the UT500 PA− mutant, the LD50 was determined using anti-Gr-1-treated BALB/c mice. In anti-Gr-1-treated mice, the LD50 of the UT500 PA− mutant was 2.86 ± 0.02 log10 CFU and was significantly different (P < 0.05) from the LD50 observed for normal BALB/c mice (Table 1). The 3-log decrease in the LD50 indicated that neutrophil depletion nearly restored full virulence to the UT500 PA− mutant. However, there was no significant difference between the LD50 for the anti-Gr-1-treated mice (1.68 ± 0.28 log10 CFU) and the LD50 for the untreated BALB/c mice (1.63 ± 0.47 log10 CFU) (Table 1) infected with the parent UT500 strain.

DISCUSSION

While the dominant virulence factors of B. anthracis are well established (10, 12, 34, 35), the mechanisms that result in the variable virulence of different strains are not known. Previous studies demonstrated empirically that the Ames strain of B. anthracis was significantly more virulent than certain other pXO1+ pXO2+ strains (5, 28, 51). In addition, there are well-documented variations among B. anthracis strains in terms of the protection provided by anthrax vaccines to various experimental animals (15, 25, 28, 42). The differences underlying these variations in virulence are not understood, although they are likely to be due to the abilities of the different bacterial strains to overcome the host innate response at the initial site of infection. A key element for understanding the differences among strains is having a model that can discern differences among isogenic mutants and be manipulated in order to understand the basis of any detectable differences. Understanding these processes is crucial for the development of broadly acting immunomodulators that enhance innate immunity and for the development of the most effective vaccines.

In this study, we evaluated isogenic mutants of two different genetically complete B. anthracis strains, UT500 and Ames, and demonstrated that in an s.c. infection the virulence of the UT500 strain was toxin dependent, whereas the virulence of the Ames strain was toxin independent. These data were in contrast to findings for the toxin-deficient mutants of the Ames strain or the UT500 strain (23) inoculated via the respiratory (i.t.) route, where the toxin-deficient mutants of both strains were as virulent as the parent strains. Thus, the difference in the virulence phenotypes of the two strains depended on the route of inoculation and likely reflected differences in interactions between the two strains of bacteria and the host microenvironment at the site of infection. The difference between the virulence of the UT500 strain and the virulence of the Ames strain was also tested using vegetative cells rather than spores as inocula. The toxin-dependent and toxin-independent virulence phenotypes of UT500 and Ames were maintained in these experiments. The demonstration that Gr-1+ phagocyte depletion significantly abolished the toxin dependence of the UT500 PA− mutant suggests that phagocytes, particularly neutrophils, recruited to the inoculation site were the dominant host factor involved in the toxin-dependent virulence phenotype. Neutrophils play a critical role in limiting B. anthracis infection through direct antimicrobial activity and modulation of other cellular components of innate immunity (8, 13, 32). Besides neutrophils, other Gr-1+ cells, like some monocytes and plasmacytoid dendritic cells, could also be depleted in the anti-Gr-1 antibody-treated mice (17). Because the anti-Gr-1 antibody targets primarily neutrophils, we suggest that these cells likely play the predominant role in the host defense against s.c. anthrax in the model, but certainly the possibility that other innate immune cells contribute cannot be excluded.

We propose that the s.c. model is a powerful model for understanding the dynamics of the host-pathogen interaction. In a B. anthracis infection, a strong innate immune response is immediately triggered (1, 2, 10, 13, 19, 20, 46, 47), resulting in a battle between the host cells, which attempt to clear the bacterium, and the bacterium with its bacterial toxins, which attempt to disable the innate response (3, 34, 37, 43, 46, 47), and its capsule, which provides protection by resisting uptake by phagocytes in the hostile environment (12, 14, 26). However, in the absence of toxins, the Ames and UT500 strains differed in virulence when the s.c. route of infection was used; the Ames PA− mutant was virulent, while the UT500 PA− mutant showed a marked decrease in virulence. These findings are consistent with the results of previous studies demonstrating increased virulence of the Ames strain compared with the Vollum 1B strain and the UM23-1 (Weybridge A) strain when plasmid-cured and plasmid-swapped derivatives of these strains were used for s.c. infection of mice (51). This observed strain-dependent difference in virulence was inferred to be the result of differences at the molecular level involving the genes on the strain-specific pXO2 plasmid and chromosome (48, 51).

In summary, factors other than toxins contribute significantly to the virulence of the Ames strain in the s.c. murine model, and these factors might explain the increased virulence of this strain compared with other strains (5, 28, 51). The PGA capsule is another virulence factor which helps B. anthracis vegetative forms evade phagocyte defenses (31, 48), but capsule formation by the UT500 strain prior to s.c. infection did not eliminate the toxin dependence of the UT500 strain. However, when host innate immunity was compromised by depleting neutrophils, the toxin dependence of the UT500 strain was eliminated as the toxin-deficient UT500 PA− mutant became virulent in such mice. At present little is known about the differences between the Ames and UT500 strains that would explain the observed phenotypic difference. A thorough analysis of these strains is required, and hence, nucleotide sequences of these two strains are currently being analyzed to help us understand possible chromosomal or plasmid-encoded genetic differences.

Infection of two different mouse strains with B. anthracis strains and mutants resulted in different responses related to the host genetic background. Although the LD50s of the UT500 strain and mutants of this strain were not significantly different for BALB/c and C57BL mice, the survival data revealed differences that were mouse strain dependent. Following infection with 100× LD50 of the UT500 strain, C57BL mice died significantly faster than BALB/c mice, consistent with previous reports (39, 49). Between the two mouse strains, the survival curves for the mice infected with the EF− mutants were different, while the survival curves for PA− mutant-infected mice were essentially the same. These observations suggest that the difference in survival kinetics observed in the parental challenges was due to greater toxin sensitivity in C57BL mice. Nevertheless, both BALB/c and C57BL mice had a shorter survival when they were infected with the LF-expressing mutant than when they were infected with the EF-expressing mutant, as has been observed with other B. anthracis mutants (4, 37, 48). In contrast to the results obtained with viable organisms, when equivalent doses of purified ET and LT were injected intraperitoneally into mice, the mice that received ET died much more rapidly than the mice that received LT (4 to 5 h versus 48 to 60 h), and BALB/c mice were more sensitive to LT than C57BL mice (16, 33). While on the surface the latter findings appear to conflict with our findings, we believe that it is difficult to directly compare studies using viable B. anthracis and studies using purified toxins. Thus, in our studies, the production of a single toxin occurred in the context of an ongoing infection, in which a number of bacterial components interacted with multiple cells in the microenvironment and the interactions could readily influence the response to the toxin. Furthermore, unlike an experimental setting where precise equivalent toxin doses can be injected into an animal, the in vivo concentrations, as well as the tissue distribution of LT and ET during active infections with the EF− and LF− mutants, respectively, are likely to be different.

In conclusion, the s.c. infection model in mice should be extremely useful for examining the role of individual virulence factors in anthrax pathogenesis and for comparing the virulence phenotypes of B. anthracis strains, particularly when virulence factor-deficient mutants are used. However, other routes of infection, particularly the intrapulmonary route, should not be overlooked as new virulence factors and additional B. anthracis strains are studied. Nevertheless, the ability of the murine s.c. infection to discriminate between two B. anthracis strains with regard to the role for toxins in establishing infection provides a model to assess multiple additional strains to determine the frequency of the toxin-dependent virulence phenotype.

Acknowledgments

We thank Lucy Berliba, Sonja Dean, Tara Henry-Hoefer, Charlene Hensler, Josh Ngyuen, and Quiteria Sanchez for expert technical assistance.

This study was supported by Public Health Service grants P01 A1056295-01 and U54 AI057156 from the National Institutes of Health.

Editor: J. B. Bliska

Footnotes

Published ahead of print on 3 November 2008.

REFERENCES

- 1.Agrawal, A., J. Lingappa, S. H. Leppla, S. Agrawal, A. Jabbar, C. Quinn, and B. Pulendran. 2003. Impairment of dendritic cells and adaptive immunity by anthrax lethal toxin. Nature 424329-334. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Alileche, A., E. R. Serfass, S. M. Muehlbauer, S. A. Porcelli, and J. Brojatsch. 2005. Anthrax lethal toxin-mediated killing of human and murine dendritic cells impairs the adaptive immune response. PLoS Pathog. 1e19. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Baldari, C. T., F. Tonello, S. R. Paccani, and C. Montecucco. 2006. Anthrax toxins: a paradigm of bacterial immune suppression. Trends Immunol. 27434-440. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Brossier, F., M. Weber-Levy, M. Mock, and J. C. Sirard. 2000. Role of toxin functional domains in anthrax pathogenesis. Infect. Immun. 681781-1786. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Coker, P. R., K. L. Smith, P. F. Fellows, G. Rybachuck, K. G. Kousoulas, and M. E. Hugh-Jones. 2003. Bacillus anthracis virulence in guinea pigs vaccinated with anthrax vaccine adsorbed is linked to plasmid quantities and clonality. J. Clin. Microbiol. 411212-1218. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Collier, R. J., and J. A. Young. 2003. Anthrax toxin. Annu. Rev. Cell Dev. Biol. 1945-70. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Conlan, J. W., and R. J. North. 1994. Neutrophils are essential for early anti-Listeria defense in the liver, but not in the spleen or peritoneal cavity, as revealed by a granulocyte-depleting monoclonal antibody. J. Exp. Med. 179259-268. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Cote, C. K., N. Van Rooijen, and S. L. Welkos. 2006. Roles of macrophages and neutrophils in the early host response to Bacillus anthracis spores in a mouse model of infection. Infect. Immun. 74469-480. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Deziel, M. R., H. Heine, A. Louie, M. Kao, W. R. Byrne, J. Basset, L. Miller, K. Bush, M. Kelly, and G. L. Drusano. 2005. Effective antimicrobial regimens for use in humans for therapy of Bacillus anthracis infections and postexposure prophylaxis. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 495099-5106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Dixon, T. C., M. Meselson, J. Guillemin, and P. C. Hanna. 1999. Anthrax. N. Engl. J. Med. 341815-826. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Drysdale, M., A. Bourgogne, S. G. Hilsenbeck, and T. M. Koehler. 2004. atxA controls Bacillus anthracis capsule synthesis via acpA and a newly discovered regulator, acpB. J. Bacteriol. 186307-315. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Drysdale, M., S. Heninger, J. Hutt, Y. Chen, C. R. Lyons, and T. M. Koehler. 2005. Capsule synthesis by Bacillus anthracis is required for dissemination in murine inhalation anthrax. EMBO J. 24221-227. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Drysdale, M., G. Olson, T. M. Koehler, M. F. Lipscomb, and C. R. Lyons. 2007. Murine innate immune response to virulent toxigenic and nontoxigenic Bacillus anthracis strains. Infect. Immun. 751757-1764. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ezzell, J. W., and S. L. Welkos. 1999. The capsule of Bacillus anthracis, a review. J. Appl. Microbiol. 87250. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Fellows, P. F., M. K. Linscott, S. F. Little, P. Gibbs, and B. E. Ivins. 2002. Anthrax vaccine efficacy in golden Syrian hamsters. Vaccine 201421-1424. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Firoved, A. M., G. F. Miller, M. Moayeri, R. Kakkar, Y. Shen, J. F. Wiggins, E. M. McNally, W. J. Tang, and S. H. Leppla. 2005. Bacillus anthracis edema toxin causes extensive tissue lesions and rapid lethality in mice. Am. J. Pathol. 1671309-1320. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Fleming, T. J., M. L. Fleming, and T. R. Malek. 1993. Selective expression of Ly-6G on myeloid lineage cells in mouse bone marrow. RB6-8C5 mAb to granulocyte-differentiation antigen (Gr-1) detects members of the Ly-6 family. J. Immunol. 1512399-2408. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Green, B. D., L. Battisti, T. M. Koehler, C. B. Thorne, and B. E. Ivins. 1985. Demonstration of a capsule plasmid in Bacillus anthracis. Infect. Immun. 49291-297. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Guidi-Rontani, C., M. Levy, H. Ohayon, and M. Mock. 2001. Fate of germinated Bacillus anthracis spores in primary murine macrophages. Mol. Microbiol. 42931-938. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Hahn, B. L., T. S. Bischof, and P. G. Sohnle. 2008. Superficial exudates of neutrophils prevent invasion of Bacillus anthracis bacilli into abraded skin of resistant mice. Int. J. Exp. Pathol. 89180-187. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Harvill, E. T., G. Lee, V. K. Grippe, and T. J. Merkel. 2005. Complement depletion renders C57BL/6 mice sensitive to the Bacillus anthracis Sterne strain. Infect. Immun. 734420-4422. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Heine, H. S., J. Bassett, L. Miller, J. M. Hartings, B. E. Ivins, M. L. Pitt, D. Fritz, S. L. Norris, and W. R. Byrne. 2007. Determination of antibiotic efficacy against Bacillus anthracis in a mouse aerosol challenge model. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 511373-1379. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Heninger, S., M. Drysdale, J. Lovchik, J. Hutt, M. F. Lipscomb, T. M. Koehler, and C. R. Lyons. 2006. Toxin-deficient mutants of Bacillus anthracis are lethal in a murine model for pulmonary anthrax. Infect. Immun. 746067-6074. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Inglesby, T. V., T. O'Toole, D. A. Henderson, J. G. Bartlett, M. S. Ascher, E. Eitzen, A. M. Friedlander, J. Gerberding, J. Hauer, J. Hughes, J. McDade, M. T. Osterholm, G. Parker, T. M. Perl, P. K. Russell, and K. Tonat. 2002. Anthrax as a biological weapon, 2002: updated recommendations for management. JAMA 2872236-2252. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Ivins, B. E., M. L. Pitt, P. F. Fellows, J. W. Farchaus, G. E. Benner, D. M. Waag, S. F. Little, G. W. Anderson, Jr., P. H. Gibbs, and A. M. Friedlander. 1998. Comparative efficacy of experimental anthrax vaccine candidates against inhalation anthrax in rhesus macaques. Vaccine 161141-1148. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Kozel, T. R., W. J. Murphy, S. Brandt, B. R. Blazar, J. A. Lovchik, P. Thorkildson, A. Percival, and C. R. Lyons. 2004. mAbs to Bacillus anthracis capsular antigen for immunoprotection in anthrax and detection of antigenemia. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 1015042-5047. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Little, S. F., and B. E. Ivins. 1999. Molecular pathogenesis of Bacillus anthracis infection. Microbes Infect. 1131-139. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Little, S. F., and G. B. Knudson. 1986. Comparative efficacy of Bacillus anthracis live spore vaccine and protective antigen vaccine against anthrax in the guinea pig. Infect. Immun. 52509-512. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Loving, C. L., M. Kennett, G. M. Lee, V. K. Grippe, and T. J. Merkel. 2007. Murine aerosol challenge model of anthrax. Infect. Immun. 752689-2698. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Lyons, C. R., J. Lovchik, J. Hutt, M. F. Lipscomb, E. Wang, S. Heninger, L. Berliba, and K. Garrison. 2004. Murine model of pulmonary anthrax: kinetics of dissemination, histopathology, and mouse strain susceptibility. Infect. Immun. 724801-4809. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Makino, S., I. Uchida, N. Terakado, C. Sasakawa, and M. Yoshikawa. 1989. Molecular characterization and protein analysis of the cap region, which is essential for encapsulation in Bacillus anthracis. J. Bacteriol. 171722-730. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Mayer-Scholl, A., R. Hurwitz, V. Brinkmann, M. Schmid, P. Jungblut, Y. Weinrauch, and A. Zychlinsky. 2005. Human neutrophils kill Bacillus anthracis. PLoS Pathog. 1e23. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Moayeri, M., and S. H. Leppla. 2004. The roles of anthrax toxin in pathogenesis. Curr. Opin. Microbiol. 719-24. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Moayeri, M., N. W. Martinez, J. Wiggins, H. A. Young, and S. H. Leppla. 2004. Mouse susceptibility to anthrax lethal toxin is influenced by genetic factors in addition to those controlling macrophage sensitivity. Infect. Immun. 724439-4447. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Mock, M., and A. Fouet. 2001. Anthrax. Annu. Rev. Microbiol. 55647-671. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Okinaka, R. T., K. Cloud, O. Hampton, A. R. Hoffmaster, K. K. Hill, P. Keim, T. M. Koehler, G. Lamke, S. Kumano, J. Mahillon, D. Manter, Y. Martinez, D. Ricke, R. Svensson, and P. J. Jackson. 1999. Sequence and organization of pXO1, the large Bacillus anthracis plasmid harboring the anthrax toxin genes. J. Bacteriol. 1816509-6515. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Pezard, C., P. Berche, and M. Mock. 1991. Contribution of individual toxin components to virulence of Bacillus anthracis. Infect. Immun. 593472-3477. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Phipps, A. J., C. Premanandan, R. E. Barnewall, and M. D. Lairmore. 2004. Rabbit and nonhuman primate models of toxin-targeting human anthrax vaccines. Microbiol. Mol. Biol. Rev. 68617-629. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Popov, S. G., T. G. Popova, E. Grene, F. Klotz, J. Cardwell, C. Bradburne, Y. Jama, M. Maland, J. Wells, A. Nalca, T. Voss, C. Bailey, and K. Alibek. 2004. Systemic cytokine response in murine anthrax. Cell. Microbiol. 6225-233. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Radka, S. F., D. D. Kostyu, and D. B. Amos. 1982. A monoclonal antibody directed against the HLA-Bw6 epitope. J. Immunol. 1282804-2806. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Reed, L., and H. Muench. 1938. A simple method of estimating fifty per cent endpoints. Am. J. Hyg. 27493-497. [Google Scholar]

- 42.Ribot, W. J., B. S. Powell, B. E. Ivins, S. F. Little, W. M. Johnson, T. A. Hoover, S. L. Norris, J. J. Adamovicz, A. M. Friedlander, and G. P. Andrews. 2006. Comparative vaccine efficacy of different isoforms of recombinant protective antigen against Bacillus anthracis spore challenge in rabbits. Vaccine 243469-3476. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Rossi Paccani, S., F. Tonello, L. Patrussi, N. Capitani, M. Simonato, C. Montecucco, and C. T. Baldari. 2007. Anthrax toxins inhibit immune cell chemotaxis by perturbing chemokine receptor signalling. Cell. Microbiol. 9924-929. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Stearns-Kurosawa, D. J., F. Lupu, F. B. Taylor, Jr., G. Kinasewitz, and S. Kurosawa. 2006. Sepsis and pathophysiology of anthrax in a nonhuman primate model. Am. J. Pathol. 169433-444. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Sue, D., C. K. Marston, A. R. Hoffmaster, and P. P. Wilkins. 2007. Genetic diversity in a Bacillus anthracis historical collection (1954 to 1988). J. Clin. Microbiol. 451777-1782. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Tournier, J. N., A. Quesnel-Hellmann, A. Cleret, and D. R. Vidal. 2007. Contribution of toxins to the pathogenesis of inhalational anthrax. Cell. Microbiol. 9555-565. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Triantafilou, M., A. Uddin, S. Maher, N. Charalambous, T. S. Hamm, A. Alsumaiti, and K. Triantafilou. 2007. Anthrax toxin evades Toll-like receptor recognition, whereas its cell wall components trigger activation via TLR2/6 heterodimers. Cell. Microbiol. 92880-2892. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Welkos, S. L. 1991. Plasmid-associated virulence factors of nontoxigenic (pX01−) Bacillus anthracis. Microb. Pathog 10183-198. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Welkos, S. L., T. J. Keener, and P. H. Gibbs. 1986. Differences in susceptibility of inbred mice to Bacillus anthracis. Infect. Immun. 51795-800. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Welkos, S. L., R. W. Trotter, D. M. Becker, and G. O. Nelson. 1989. Resistance to the Sterne strain of B. anthracis: phagocytic cell responses of resistant and susceptible mice. Microb. Pathog. 715-35. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Welkos, S. L., N. J. Vietri, and P. H. Gibbs. 1993. Non-toxigenic derivatives of the Ames strain of Bacillus anthracis are fully virulent for mice: role of plasmid pX02 and chromosome in strain-dependent virulence. Microb. Pathog. 14381-388. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Zaucha, G. M., L. M. Pitt, J. Estep, B. E. Ivins, and A. M. Friedlander. 1998. The pathology of experimental anthrax in rabbits exposed by inhalation and subcutaneous inoculation. Arch. Pathol. Lab. Med. 122982-992. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]