Abstract

The human gastric pathogen Helicobacter pylori encounters frequent oxidative and acid stress in its specific niche, and this causes bacterial DNA damage. H. pylori exhibits a very high degree of DNA recombination, which is required for repairing both DNA double-stranded (ds) breaks and blocked replication forks. Nevertheless, few genes encoding components of DNA recombinational repair processes have been identified in H. pylori. An H. pylori mutant defective in a putative helicase gene (HP1553) was constructed and characterized herein. The HP1553 mutant strain was much more sensitive to mitomycin C than the WT strain, indicating that HP1553 is required for repair of DNA ds breaks. Disruption of HP1553 resulted in a significant decrease in the DNA recombination frequency, suggesting that HP1553 is involved in DNA recombination processes, probably functioning as a RecB-like helicase. HP1553 was shown to be important for H. pylori protection against oxidative stress-induced DNA damage, as the exposure of the HP1553 mutant cells to air for 6 h caused significant fragmentation of genomic DNA and led to cell death. In a mouse infection model, the HP1553 mutant strain displayed a greatly reduced ability to colonize the host stomachs, indicating that HP1553 plays a significant role in H. pylori survival/colonization in the host.

Homologous DNA recombination is one of the key mechanisms responsible for the repair of DNA double-stranded (ds) breaks. More frequently, homologous recombination is required for repairing stalled replication forks caused by DNA damage (3). DNA recombinational repair requires a large number of proteins that act at various stages of the process (4). The first stage, presynapsis, is the generation of 3′ single-stranded DNA ends that can then be used for annealing with the homologous sequence on the sister chromosome. In Escherichia coli, the two types of two-stranded lesions (ds end and daughter strand gap) are repaired by two separate pathways, RecBCD and RecFOR, respectively (15). The second and most crucial step (synapsis) is RecA-mediated introduction of the 3′ DNA overhang into the homologous duplex of the sister chromosome. During the third step in recombination, postsynapsis, RecA-promoted strand transfer produces a four-stranded exchange, or Holliday junction, generated by the RecG and RuvAB helicases. Finally, RuvC resolves the Holliday junction in an orientation determined by RuvB, and the remaining nicks are sealed by DNA ligase. Several other genes (recJ, recQ, and recN) are also required for recombination, although their functions are not very clear (8, 26).

Helicobacter pylori is an important human pathogen involved in the etiology of gastric ulcers and cancer (7). In its physiological environment, H. pylori is thought to suffer both oxidative and acid stresses frequently, leading to DNA damage (6, 20, 22, 32). H. pylori exhibits the highest level of genetic diversity known among bacteria, and a major contributor to this is the high frequency of DNA recombination (14). However, a limited number of genes that are predicted to be involved in recombinational repair are present in the H. pylori genome. The H. pylori RecA protein requires a posttranslational modification for its activity and is critical in DNA recombination and repair (9, 28). Genes encoding RuvABC proteins are present in H. pylori; thus, H. pylori may be able to restore Holliday junctions in a way similar to that for E. coli. A ruvC mutant of H. pylori was sensitive to oxidative stress and other DNA-damaging agents and was unable to establish long-term infection in a mouse model, highlighting the role of DNA recombinational repair in bacterial survival in vivo (17). H. pylori contains the homologues of RecG, RecJ, RecR, and RecN. Our recent study (34) showed that H. pylori RecN is involved in DNA recombinational repair and plays a significant role in the bacterium's survival in the host. Many genes coding for the components of DNA recombinational repair that are involved in the presynapsis stage, such as RecBCD, RecF, RecO, and RecQ, are missing in the H. pylori genome (1, 29).

DNA helicases play key roles in many cellular processes by promoting unwinding of the DNA double helix (25). Bacterial genomes encode a set of helicases of the DExx family that fulfill several, sometimes overlapping, functions. Based on sequence homology, bacterial RecB, UvrD, Rep, and PcrA were classified as superfamily 1 helicases (16, 21, 25). In E. coli, which is well studied, RecBCD forms a multifunctional enzyme complex that processes DNA ends resulting from a ds break. RecBCD is a bipolar helicase that splits the duplex into its component strands and digests them until encountering a recombinational hot spot (chi site). The nuclease activity is then attenuated, and RecBCD loads RecA onto the 3′ tail of the DNA (24). Another bacterial enzyme complex, AddAB, extensively studied for Bacillus subtilis, has both nuclease and helicase activities similar to those of RecBCD enzymes (13, 37). In this study, we characterized an H. pylori mutant defective in a gene (HP1553) encoding a RecB-like helicase.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

H. pylori strains and culture conditions.

H. pylori strain 26695 or X47 was cultured on Brucella agar (Difco) plates supplemented with 10% defibrinated sheep blood or 5% fetal bovine serum (called BA plates). Cultures of H. pylori were grown microaerobically at 37°C in an incubator under continuously controlled levels of oxygen (5% partial pressure O2 and 5% CO2, and the balance was N2). For assessing the susceptibility to mitomycin C (MMC), H. pylori strains were grown on BA plates containing different concentration of MMC under microaerobic conditions, and the growth was recorded after 2 days.

Construction of H. pylori HP1553 mutant.

A 1.1-kb fragment containing the HP1553 gene was amplified by PCR from genomic DNA of strain 26695 using the primer pair P1553F (5′-AAGATTGCGCACATTTTGATTGA-3′) and P1553R (5′-TCTTTAGCCGCTTCTTCTTTGTCT-3′). The PCR product was cloned into the pGEM-T vector to generate pGEM-HP1553. Subsequently, a chloramphenicol resistance (Cmr) cassette was inserted within the HP1553 sequence of pGEM-HP1553, removing a 450-bp HindIII-HindIII fragment of the gene. The disrupted HP1553 gene was then introduced into the H. pylori wild type (WT) by natural transformation via allelic exchange and chloramphenicol (50 μg/ml)-resistant colonies were isolated. The disruption of the gene in the genome of the mutant strain was confirmed by PCR, showing an increase in the expected size of the PCR product, and by direct sequencing of the PCR fragment.

Air survival assay.

H. pylori strains were grown on BA plates to late log phase, and the cells were suspended in phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) at a concentration of ∼108 cells/ml. The cell suspensions were incubated at 37°C under normal atmospheric conditions (21% O2, without alteration of CO2 partial pressure), with moderate shaking. Samples were then removed at various time points (2, 4, 6, 8, and 10 h), serially diluted, and spread onto BA plates. Colony counts were recorded after 4 days of incubation in a microaerobic atmosphere (5% partial pressure O2) at 37°C.

DNA transformation assay to assess recombination frequency.

The donor DNA used in this study included (i) a 330-bp PCR fragment of the H. pylori rpoB gene containing a site-specific mutation (at the center of the fragment) conferring rifampin resistance, (ii) a linear DNA fragment containing a kanamycin resistance (Kanr) cassette (1.4 kb) flanked by H. pylori acnB gene sequences (about 550 bp on each side of the Kanr cassette), and (iii) pHP1, an H. pylori-E. coli shuttle plasmid carrying a Kanr cassette (12).

H. pylori strains were grown on BA plates to late log phase, and the cells were suspended in PBS at a concentration of ∼108/ml (recipient cells for transformation). A portion (30 μl) of the suspension was mixed with 100 ng of donor DNA and spotted onto a BA plate. After incubation for 18 h under microaerobic conditions at 37°C, the transformation mixture was harvested and suspended in 1 ml PBS. Portions (100 μl) of the suspension (or appropriate dilution) were plated onto either BA plates or BA plates containing a selective antibiotic (20 μg/ml rifampin or 40 μg/ml kanamycin, depending on the donor DNA used). The plates were incubated for 4 days under microaerobic conditions at 37°C, and the numbers of colonies were counted. The transformation frequency was determined by the number of resistant colonies divided by the total number of CFU. In a normalized DNA transformation assay, the frequency of transformation is expressed as the number of transformants per 108 recipient cells. As negative controls, H. pylori strains with no DNA added were tested under this assay condition; no antibiotic-resistant colonies were observed.

DNA fragmentation analysis by electrophoresis.

Analysis of DNA fragmentation was performed as described by Zirkle and Krieg (38), with the following minor modifications. Cells were suspended in PBS buffer to an optical density at 600 nm of 0.5. A portion (500 μl) of the sample was centrifuged for 1 min at 15,000 × g, the pellet was washed in TE buffer (50 mM Tris-HCl, 5 mM EDTA, pH 8) at 4°C, and the final pellet was suspended in 10 μl TE buffer. This suspension was then added to 50 μl of 1% low-melting-point agarose at 37°C. Agarose and cells were mixed thoroughly, and 60-μl blocks were made by pipetting the mixture onto parafilm. After solidification, the blocks were placed in a lysing solution (0.25 mM EDTA, 0.5% Sarkosyl, 0.5 mg/ml proteinase K) and incubated at 55°C for 1 h, followed by overnight incubation at room temperature. The next day, the blocks were washed three times for 10 min each in cold TE buffer. Agarose plugs were then submerged in a 0.8% agarose gel. Samples were subjected to gel electrophoresis for 7 h at 30 V. Gels were then stained for 30 min with ethidium bromide (0.5 μg/ml), destained in H2O, and then visualized under UV light.

Mouse colonization.

Mouse colonization assays were performed essentially as described previously (31, 35). Briefly, WT X47 or X47 HP1553 mutant cells were harvested after 48 h of growth on BA plates (37°C, 5% oxygen) and suspended in PBS to an optical density at 600 nm of 1.7. The headspace in the tube was sparged with argon gas to minimize oxygen exposure, and the tube was tightly sealed. The bacterial suspensions were administered to C57BL/6J mice (3 × 108 H. pylori cells/mouse) twice, with each of the oral deliveries made 2 days apart. Three weeks after the first inoculation, the mice were sacrificed and the stomachs were removed, weighed, and homogenized in argon-sparged PBS (23) to avoid O2 exposure. Stomach homogenate dilutions (dilutions conducted in tubes in argon-sparged buffer) were plated on BA plates supplemented with bacitracin (100 μg/ml), vancomycin (10 μg/ml), and amphotericin B (10 μg/ml), and the plates were rapidly transported into an incubator containing sustained 5% partial pressure O2. After incubation for 5 to 7 days, the fresh H. pylori colonies were enumerated; the data are expressed as CFU per gram of stomach.

RESULTS AND DISCUSSION

Identification of a recB-like gene and construction of the HP1553 mutant.

When looking for a RecB-like helicase in H. pylori, we found that HP1553 from strain 26695 was annotated as a gene encoding a putative helicase (29) and that the corresponding gene from strain J99 was annotated as pcrA (1). An amino acid sequence alignment of HP1553 to E. coli RecB (or to B. subtilis AddA) revealed 24% identity (to both heterologous systems) at the N-terminal half (helicase domain) and no significant homology at the C-terminal half (including the nuclease domain). A similar level of sequence homology (25% identity at the helicase domain) was also found between HP1553 and B. subtilis PcrA.

The data from our RecN study (34) indicated that H. pylori has an efficient system to repair DNA ds breaks via recombination, and we suspected that HP1553 could be a RecB-like helicase involved in this process. To test whether HP1553 functions as a RecB-like helicase, we constructed an H. pylori HP1553 mutant by inserting a Cmr cassette at the two HindIII restriction sites within the HP1553 gene. By insertion of the Cmr cassette, the 450-bp fragment between the two HindIII sites within the HP1553 gene was removed. Correct insertion of the cassette within the HP1553 gene in the H. pylori genome was confirmed by PCR, showing the increase in the expected size of the PCR product (data not shown). Under the normal microaerobic conditions for H. pylori growth, the mutant grows more slowly than the WT (the growth rate is about half that of the WT). The HP1553 mutants were constructed using H. pylori strains 26695 and X47. As X47 is a strain well adapted for mouse colonization, all of the assays reported below were done with X47 and its isogenic HP1553 mutant.

Downstream of the HP1553 gene is the gene nhaA, encoding a Na+/H+ antiporter. H. pylori NhaA was shown to play an important role in ion transport and regulation of intracellular pH (30). In previous construction of many H. pylori mutants by insertion of the Cmr cassette in our laboratory, no polar effects on downstream genes were observed. Therefore, it is very likely that the phenotype changes (in DNA recombination and repair) between the HP1553 Cmr mutant and its isogenic WT strain are attributable to the loss of HP1553 function.

HP1553 is involved in DNA recombinational repair.

First, we determined the sensitivity of the strains to MMC, which causes predominantly DNA ds breaks. H. pylori strains were grown on BA plates containing different concentrations of MMC, and the growth results are shown in Table 1. The WT H. pylori strain can grow on plates containing 5 ng/ml MMC but not on plates containing 10 ng/ml MMC. This sensitivity is much greater than that of other bacteria, such as B. subtilis or E. coli, which can tolerate 100 ng/ml MMC on the plate for growth (11, 19). An H. pylori mutS mutant, although more sensitive to oxidative stress than the WT (31), has the same phenotype for MMC sensitivity as the WT. In contrast, the HP1553 mutant strain showed no growth on plates containing MMC at 2.5 ng/ml or higher concentrations. This is a more severe phenotype than that observed for the recN mutant strain, which can tolerate 2.5 ng/ml MMC but cannot grow on plates containing 5 ng/ml MMC.

TABLE 1.

Growth of different strains on BA plates containing different concentrations of MMC

| Strain | Growth on MMC ata:

|

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0 ng/ml | 2.5 ng/ml | 5 ng/ml | 10 ng/ml | |

| X47 WT | ++ | ++ | + | − |

| X47 mutS::Cmr | ++ | ++ | + | − |

| X47 recN::Cmr | ++ | + | − | − |

| X47 HP1553::Cmr | ++ | − | − | − |

++, normal growth; +, compromised growth; −, no growth.

The above-described results strongly suggest that HP1553 is involved in the repair of DNA ds breaks. To investigate whether this repair function is fulfilled by a DNA recombination process, we tested whether loss of HP1553 function had an adverse effect on DNA recombination by determining the frequency of DNA transformation. As described previously (34), we used two different types of DNA for examining DNA transformation of H. pylori. A specific A-to-G mutation in the H. pylori rpoB gene (rpoB3 allele) confers rifampin resistance (36). A 330-bp PCR fragment containing this specific mutation at the center of the fragment was used to transform H. pylori strains by using rifampin resistance as a selective marker. Another type of DNA used for transformation was the sequence of the H. pylori acnB gene (a housekeeping gene, 1.1 kb) in which a Kanr cassette (1.4 kb) was inserted at the center (acnB::Kanr). A plasmid that does not contain any H. pylori chromosomal gene sequence (pHP1) was used as a control, as this transformation does not involve DNA recombination (the plasmid remains extrachromosomal).

The results for transformation are shown in Table 2. Using rpoB3 DNA as donor DNA, the X47 HP1553 mutant had a transformation frequency of 3.7 × 10−5, which was eightfold lower than that for the WT strain X47 (3.07 × 10−4). When acnB::Kanr DNA was used as the donor DNA, WT H. pylori X47 had a transformation frequency of 9.4 × 10−6. In contrast, the transformation frequency for the HP1553 mutant was only 3.2 × 10−7, which is 30-fold lower than that of the WT strain. For both types of donor DNA (rpoB3 and acnB::Kanr DNA), the HP1553 strain data (transformation frequency) are significantly lower than those of the WT strain, according to the Student t test (P < 0.01). In control experiments using the plasmid pHP1 as the donor DNA, no significant difference was observed for the transformation frequency between the WT and the HP1553 mutant. These results indicated that HP1553 plays a significant role in the DNA recombination process of H. pylori.

TABLE 2.

Transformation frequencies with different types of donor DNA

| H. pylori strain | Transformation frequencya with donor DNA

|

||

|---|---|---|---|

| rpoB3 (330 bp) | acnB::Kanr (2.5 kb) | Plasmid pHP1 | |

| X47 WT | 30,700 ± 1,700 | 940 ± 80 | 310 ± 28 |

| X47 HP1553::Cmr | 3,700 ± 390 | 32 ± 4 | 290 ± 25 |

| 26695 WT | 2,400 ± 340 | 56 ± 9 | 82 ± 17 |

| 26695 HP1553::Cmr | 690 ± 210 | 13 ± 4 | 74 ± 16 |

The transformation frequencies are presented as the numbers of transformants (resistant colonies) per 108 recipient cells. Data are means ± standard errors from three independent determinations.

Upon completion of our work, it was observed that two new papers describing the roles of H. pylori DNA recombinational repair components were published (2, 18). Amundsen et al. (2) characterized the AddAB helicase-nuclease, wherein AddA corresponds to HP1553. While studying primarily a RecO orthologue in H. pylori, Marsin et al. (18) also reported the effect of a recB (HP1553) mutation on transformation frequency. Their results showed that the recB mutant (in the strain 26695 background) was not impaired in transformation but that instead it was hypertransformable. Therefore, we also performed a transformation assay for strain 26695 and its isogenic HP1553 mutant (Table 2). Generally, strain 26695 has a lower transformation frequency than strain X47. From our results, the 26695 HP1553 mutant displayed three- to fourfold lower transformation frequencies than the WT, when both rpoB3 and acnB::Kanr DNA were used as the donor DNA. We noticed that Marsin et al. (18) used the total genomic DNA from the streptomycin-resistant strain or the kanamycin-resistant strain for the transformation assay, while we used the defined linear DNA fragments of small sizes. The use of different assay systems may partly explain the discrepancy in transformation results observed in the two studies.

HP1553 is a putative helicase belonging to superfamily 1 helicases, which include bacterial RecB, UvrD, Rep, and PcrA. Among these helicases, RecB (or AddA in Bacillus) is required for DNA recombination. On the other hand, UvrD, Rep, and PcrA helicases suppress DNA recombination (21). UvrD controls the access of recombination proteins to blocked replication forks, which is required for replication restart (16), and an H. pylori uvrD mutant was shown to have an increased frequency of intergenomic recombination (10). A homologue of the rep gene was identified in the H. pylori genome sequences (HP0911, or JHP1371) but has not yet been studied experimentally. PcrA is an essential helicase present in all gram-positive bacteria, and pcrA mutants are hyperrecombinogenic (21). Genetic studies suggest that PcrA interacts with RecFOR to sustain normal levels of recombination in bacteria (21). As the H. pylori HP1553 mutant showed a decreased recombination frequency, we conclude that HP1553 likely functions as a RecB-like helicase. Amundsen et al. (2) recently demonstrated that AddAB has ATP-dependent helicase and nuclease activities. Detailed biochemical analyses of the helicase-nuclease activities of HP1553 and its partner proteins (as in the RecBCD or AddAB complex) are required to further define the role of HP1553 in DNA recombination and repair.

HP1553 is important for H. pylori protection against oxidative DNA damage.

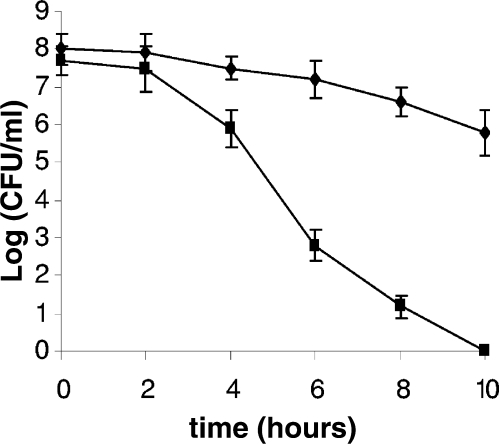

Under physiological conditions, DNA ds breaks often result from exposure of cells to oxidative agents (5). Oxidative stress is a major stress condition that H. pylori encounters in its physiological niche. To test whether HP1553 plays a role in repairing DNA damage derived from oxidative stress, we examined the sensitivities of the H. pylori strains to oxidative stress by an air survival assay. The cell suspensions (∼108 cells/ml) were exposed to air, and the numbers of surviving cells were determined at various time points (Fig. 1). Two hours after exposing cells to air, the number of the surviving HP1553 mutant cells started to decrease at a rate much faster than that of the WT cells. At the 10-h time point, about 106 viable cells of the WT strain (∼1% of that at time zero) could be recovered, while the HP1553 mutant cells were completely killed (i.e., no viable cells recovered). The results clearly showed that the HP1553 mutant is significantly more sensitive to atmospheric oxygen than the WT.

FIG. 1.

Survival of WT H. pylori X47 (diamonds) and its isogenic HP1553 mutant (squares) upon exposure to air. H. pylori cell suspensions in PBS were incubated at 37°C under normal atmospheric conditions (21% partial pressure O2, and no alteration of CO2 partial pressure). Samples were removed at the times indicated on the x axis and were used for plate count determinations in a 5% oxygen environment. The data are the means from three experiments, with standard deviations indicated. Based on statistical analysis (the Student t test), the differences in cell survival between the WT and the mutant strain are significant (P < 0.01) for all of the data points except for the 2-h time point.

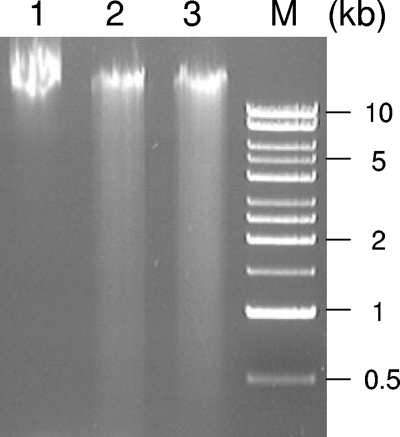

Next, we examined the level of oxidative stress-induced DNA damage in the HP1553 mutant cells compared to that for the WT, using a DNA fragmentation assay originally described by Zirkle and Krieg (38) and modified as described in our recent studies (33, 34). In this assay, cells were lysed in a block of 1% low-melting-point agarose followed directly by electrophoresis on a 0.8% agarose gel, minimizing the generation of DNA damage during the sample preparation. Fragmentation of genomic DNA is visualized as smears at smaller-molecular-weight ranges on the agarose gel. H. pylori cells were grown on BA plates under microaerobic conditions (5% O2) to mid-log phase (for about 1 day). When the genomic DNA was examined at this time point, no significant DNA damage was observed for either the WT or the HP1553 mutant strain (not shown). Upon exposure of the cells to atmospheric conditions (approximately 21% O2 partial pressure) for 6 h, the cells were analyzed via the DNA fragmentation assay, and the results are shown in Fig. 2. While the WT cells contained nearly intact genomic DNA (Fig. 2, lane 1), the HP1553 mutant cells contained a large amount of fragmented DNA (Fig. 2, lane 3; smears at ranges of 0.5 to 10 kb), similar to that observed for the recN mutant cells (Fig. 2, lane 2). From the data presented above, we conclude that the HP1553 mutant strain cannot efficiently repair DNA damage generated from oxidative stress (Fig. 2); the result is cell death (Fig. 1). Thus, HP1553, functioning as a RecB-like helicase in DNA recombinational repair, is important for H. pylori protection against oxidative stress-induced damage. A similar role of DNA recombinational repair in protection against oxidative damage was found for Neisseria gonorrhoeae (27).

FIG. 2.

Agarose gel electrophoresis showing genomic DNA fragmentation of H. pylori cells after exposure to air for 6 h. Lane 1, WT strain X47; lane 2, the X47 recN mutant strain; lane 3, the X47 HP1553 mutant strain; lane M, molecular size standard. Fragmented DNA is visualized as smears on the agarose gel. The experiments were repeated three times, with similar results.

HP1553 plays a significant role in H. pylori survival/colonization in the host.

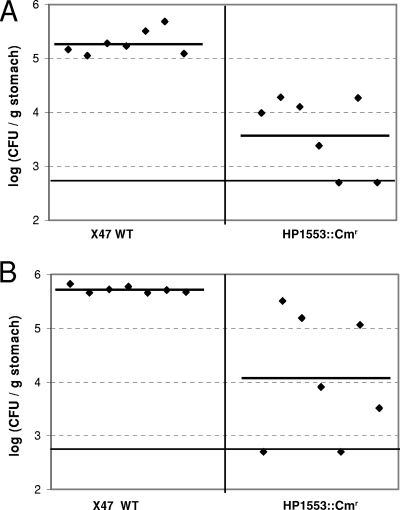

Repair of damaged DNA is known to be important for H. pylori survival and pathogenesis (20, 31). Defects in DNA recombinational repair due to loss of RuvC or RecN function in H. pylori resulted in a reduced ability to colonize the host stomach (17, 34). To determine whether the loss of HP1553 has a similar effect on H. pylori colonization in the host, we performed an assay using a mouse infection model as described previously (31, 34, 35).

WT X47 or the X47 HP1553 mutant strain was inoculated into seven C57BL/6J mice, and the colonization of H. pylori cells in the mouse stomachs was examined 3 weeks after inoculation (Fig. 3A). H. pylori was recovered from all seven mice that had been inoculated with the WT strain, with a geometric mean number of 1.93 × 105 CFU/g stomach. In contrast, five of seven mice that were inoculated with the HP1553 mutant strain were found to harbor H. pylori. The geometric mean of the colonization number for the mutant strain in the seven mice was 4.27 × 103 CFU/g stomach. According to a Wilcoxon rank test, the range of colonization values of the mutant strain is significantly lower than that of the WT at the 99% confidence level (P < 0.01). The entire mouse colonization assay was performed an additional time, with a similar difference observed between the WT and the mutant strain (Fig. 3B). These results indicate that HP1553 plays a significant role in H. pylori survival/colonization in the host.

FIG. 3.

Mouse colonization results of H. pylori X47 and its isogenic HP1553 mutant. The mice were inoculated with H. pylori two times (2 days apart), with a dose of 1.5 × 108 viable cells administered per animal each time. Colonization of H. pylori in mouse stomachs was examined 3 weeks after the first inoculation. Conditions that minimized oxygen exposure were used during stomach homogenization and homogenate dilution (see the text). Data are presented as a scatter plot (at log scale) of CFU per gram of stomach, as determined by plate counts. Each point represents the CFU count from one mouse stomach, and the solid line represents the geometric mean of the colonization number for each group (WT or HP1553 mutant). The baseline (log10 CFU/g = 2.7) is the detection limit of the assay, which represents a count below 500 CFU/g stomach.

In conclusion, the HP1553 mutant was shown to be much more sensitive to the DNA-damaging agent MMC and to oxidative stress than the WT strain, and the mutant strain has a significantly decreased DNA recombination ability (i.e., frequency), indicating that the HP1553 protein plays an important role in recombinational DNA repair in H. pylori. We demonstrated that under oxidative stress conditions H. pylori HP1553 mutant cells accumulate much more fragmented DNA than WT cells. Furthermore, it was shown that the HP1553 mutant strain displays a significantly attenuated ability to colonize mouse stomachs. The major results and conclusions reported here are in great agreement with those for the H. pylori AddAB helicase-nuclease from the study of Amundsen et al. (2).

Thus far, several components of DNA recombinational repair that are involved in the presynapsis stage, RecN (34), a RecB-like helicase (this study) or the AddAB complex (2), and a RecO orthologue (18), have been identified in H. pylori. RecN may be the protein that functions to recognize DNA ds breaks while recruiting other components, including the RecB-like helicase and other unidentified proteins, required for initiation of DNA recombination. Together with the previous report on RuvC (Holliday junction resolvase) (17), these studies highlight the role of DNA recombinational repair in H. pylori's survival and persistent colonization in the host.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported mainly by the University of Georgia Foundation, with minor support from NIH grant R01DK06285201.

We thank Sue Maier for her expertise and assistance with mouse colonization assays.

Editor: A. Camilli

Footnotes

Published ahead of print on 3 November 2008.

REFERENCES

- 1.Alm, R. A., L. S. Ling, D. T. Moir, B. L. King, E. D. Brown, P. C. Doig, D. R. Smith, B. Noonan, B. C. Guild, B. L. deJonge, G. Carmel, P. J. Tummino, A. Caruso, M. Uria-Nickelsen, D. M. Mills, C. Ives, R. Gibson, D. Merberg, S. D. Mills, Q. Jiang, D. E. Taylor, G. F. Vovis, and T. J. Trust. 1999. Genomic-sequence comparison of two unrelated isolates of the human gastric pathogen Helicobacter pylori. Nature 397176-180. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Amundsen, S. K., J. Fero, L. M. Hansen, G. A. Cromie, J. V. Solnick, G. R. Smith, and N. R. Salama. 2008. Helicobacter pylori AddAB helicase-nuclease and RecA promote recombination-related DNA repair and survival during stomach colonization. Mol. Microbiol. 69994-1007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Cox, M. M., M. F. Goodman, K. N. Kreuzer, D. J. Sherratt, S. J. Sandler, and K. J. Marians. 2000. The importance of repairing stalled replication forks. Nature 40437-41. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Cromie, G. A., J. C. Connelly, and D. R. Leach. 2001. Recombination at double-strand breaks and DNA ends: conserved mechanisms from phage to humans. Mol. Cell 81163-1174. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Demple, B., and L. Harrison. 1994. Repair of oxidative damage to DNA: enzymology and biology. Annu. Rev. Biochem. 63915-948. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ding, S. Z., Y. Minohara, X. J. Fan, J. Wang, V. E. Reyes, J. Patel, B. Dirden-Kramer, I. Boldogh, P. B. Ernst, and S. E. Crowe. 2007. Helicobacter pylori infection induces oxidative stress and programmed cell death in human gastric epithelial cells. Infect. Immun. 754030-4039. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Dunn, B. E., H. Cohen, and M. J. Blaser. 1997. Helicobacter pylori. Clin. Microbiol. Rev. 10720-741. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Fernandez, S., S. Ayora, and J. C. Alonso. 2000. Bacillus subtilis homologous recombination: genes and products. Res. Microbiol. 151481-486. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Fischer, W., and R. Haas. 2004. The RecA protein of Helicobacter pylori requires a posttranslational modification for full activity. J. Bacteriol. 186777-784. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kang, J., and M. J. Blaser. 2006. UvrD helicase suppresses recombination and DNA damage-induced deletions. J. Bacteriol. 1885450-5459. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kidane, D., H. Sanchez, J. C. Alonso, and P. L. Graumann. 2004. Visualization of DNA double-strand break repair in live bacteria reveals dynamic recruitment of Bacillus subtilis RecF, RecO and RecN proteins to distinct sites on the nucleoids. Mol. Microbiol. 521627-1639. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kleanthous, H., C. L. Clayton, and S. Tabaqchali. 1991. Characterization of a plasmid from Helicobacter pylori encoding a replication protein common to plasmids in gram-positive bacteria. Mol. Microbiol. 52377-2389. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kooistra, J., B. J. Haijema, A. Hesseling-Meinders, and G. Venema. 1997. A conserved helicase motif of the AddA subunit of the Bacillus subtilis ATP-dependent nuclease (AddAB) is essential for DNA repair and recombination. Mol. Microbiol. 23137-149. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kraft, C., and S. Suerbaum. 2005. Mutation and recombination in Helicobacter pylori: mechanisms and role in generating strain diversity. Int. J. Med. Microbiol. 295299-305. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kuzminov, A. 1999. Recombinational repair of DNA damage in Escherichia coli and bacteriophage lambda. Microbiol. Mol. Biol. Rev. 63751-813. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Lestini, R., and B. Michel. 2007. UvrD controls the access of recombination proteins to blocked replication forks. EMBO J. 263804-3814. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Loughlin, M. F., F. M. Barnard, D. Jenkins, G. J. Sharples, and P. J. Jenks. 2003. Helicobacter pylori mutants defective in RuvC Holliday junction resolvase display reduced macrophage survival and spontaneous clearance from the murine gastric mucosa. Infect. Immun. 712022-2031. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Marsin, S., A. Mathieu, T. Kortulewski, R. Guerois, and J. P. Radicella. 2008. Unveiling novel RecO distant orthologues involved in homologous recombination. PLoS Genet. 4e1000146. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Nagashima, K., Y. Kubota, T. Shibata, C. Sakaguchi, H. Shinagawa, and T. Hishida. 2006. Degradation of Escherichia coli RecN aggregates by ClpXP protease and its implications for DNA damage tolerance. J. Biol. Chem. 28130941-30946. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.O'Rourke, E. J., C. Chevalier, A. V. Pinto, J. M. Thiberge, L. Ielpi, A. Labigne, and J. P. Radicella. 2003. Pathogen DNA as target for host-generated oxidative stress: role for repair of bacterial DNA damage in Helicobacter pylori colonization. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 1002789-2794. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Petit, M. A., and D. Ehrlich. 2002. Essential bacterial helicases that counteract the toxicity of recombination proteins. EMBO J. 213137-3147. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Scott, D. R., E. A. Marcus, Y. Wen, J. Oh, and G. Sachs. 2007. Gene expression in vivo shows that Helicobacter pylori colonizes an acidic niche on the gastric surface. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 1047235-7240. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Seyler, R. W., Jr., J. W. Olson, and R. J. Maier. 2001. Superoxide dismutase-deficient mutants of Helicobacter pylori are hypersensitive to oxidative stress and defective in host colonization. Infect. Immun. 694034-4040. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Singleton, M. R., M. S. Dillingham, M. Gaudier, S. C. Kowalczykowski, and D. B. Wigley. 2004. Crystal structure of RecBCD enzyme reveals a machine for processing DNA breaks. Nature 432187-193. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Singleton, M. R., and D. B. Wigley. 2002. Modularity and specialization in superfamily 1 and 2 helicases. J. Bacteriol. 1841819-1826. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Skaar, E. P., M. P. Lazio, and H. S. Seifert. 2002. Roles of the recJ and recN genes in homologous recombination and DNA repair pathways of Neisseria gonorrhoeae. J. Bacteriol. 184919-927. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Stohl, E. A., and H. S. Seifert. 2006. Neisseria gonorrhoeae DNA recombination and repair enzymes protect against oxidative damage caused by hydrogen peroxide. J. Bacteriol. 1887645-7651. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Thompson, S. A., and M. J. Blaser. 1995. Isolation of the Helicobacter pylori recA gene and involvement of the recA region in resistance to low pH. Infect. Immun. 632185-2193. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Tomb, J. F., O. White, A. R. Kerlavage, R. A. Clayton, G. G. Sutton, R. D. Fleischmann, K. A. Ketchum, H. P. Klenk, S. Gill, B. A. Dougherty, K. Nelson, J. Quackenbush, L. Zhou, E. F. Kirkness, S. Peterson, B. Loftus, D. Richardson, R. Dodson, H. G. Khalak, A. Glodek, K. McKenney, L. M. Fitzegerald, N. Lee, M. D. Adams, E. K. Hickey, D. E. Berg, J. D. Gocayne, T. R. Utterback, J. D. Peterson, J. M. Kelley, M. D. Cotton, J. M. Weidman, C. Fujii, C. Bowman, L. Watthey, E. Wallin, W. S. Hayes, M. Borodovsky, P. D. Karp, H. O. Smith, C. M. Fraser, and J. C. Venter. 1997. The complete genome sequence of the gastric pathogen Helicobacter pylori. Nature 388539-547. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Tsuboi, Y., H. Inoue, N. Nakamura, and H. Kanazawa. 2003. Identification of membrane domains of the Na+/H+ antiporter (NhaA) protein from Helicobacter pylori required for ion transport and pH sensing. J. Biol. Chem. 27821467-21473. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Wang, G., P. Alamuri, M. Z. Humayun, D. E. Taylor, and R. J. Maier. 2005. The Helicobacter pylori MutS protein confers protection from oxidative DNA damage. Mol. Microbiol. 58166-176. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Wang, G., P. Alamuri, and R. J. Maier. 2006. The diverse antioxidant systems of Helicobacter pylori. Mol. Microbiol. 61847-860. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Wang, G., R. C. Conover, A. A. Olczak, P. Alamuri, M. K. Johnson, and R. J. Maier. 2005. Oxidative stress defense mechanisms to counter iron-promoted DNA damage in Helicobacter pylori. Free Radic. Res. 391183-1191. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Wang, G., and R. J. Maier. 2008. Critical role of RecN in recombinational DNA repair and survival of Helicobacter pylori. Infect. Immun. 76153-160. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Wang, G., and R. J. Maier. 2004. An NADPH quinone reductase of Helicobacter pylori plays an important role in oxidative stress resistance and host colonization. Infect. Immun. 721391-1396. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Wang, G., T. J. Wilson, Q. Jiang, and D. E. Taylor. 2001. Spontaneous mutations that confer antibiotic resistance in Helicobacter pylori. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 45727-733. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Yeeles, J. T., and M. S. Dillingham. 2007. A dual-nuclease mechanism for DNA break processing by AddAB-type helicase-nucleases. J. Mol. Biol. 37166-78. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Zirkle, R. E., and N. R. Krieg. 1996. Development of a method based on alkaline gel electrophoresis for estimation of oxidative damage to DNA in Escherichia coli. J. Appl. Bacteriol. 81133-138. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]