Abstract

HIV-1 Vif counteracts the antiviral activity of APOBEC3G by inhibiting its encapsidation into virions. Here, we compared the relative sensitivity to Vif of APOBEC3G in stable HeLa cells containing APOBEC3G (HeLa-A3G cells) versus that of newly synthesized APOBEC3G. We observed that newly synthesized APOBEC3G was more sensitive to degradation than preexisting APOBEC3G. Nevertheless, preexisting and transiently expressed APOBEC3G were packaged with similar efficiencies into vif-deficient human immunodeficiency virus type 1 (HIV-1) virions, and Vif inhibited the encapsidation of both forms of APOBEC3G into HIV particles equally well. Our results suggest that HIV-1 Vif preferentially induces degradation of newly synthesized APOBEC3G but indiscriminately inhibits encapsidation of “old” and “new” APOBEC3G.

APOBEC3G is a cellular cytidine deaminase with potent antiviral activity. Interference with viral infectivity requires the incorporation of APOBEC3G into virions and results in the editing of viral cDNA during subsequent reverse transcription (4, 10, 12, 25, 27). Vif can reduce the cellular expression of APOBEC3G through proteasomal degradation and thus inhibit its incorporation into virions (2, 6, 11, 14, 15, 20, 22, 26). In addition, Vif can inhibit the encapsidation of APOBEC3G through a degradation-independent mechanism, although details of this activity of Vif remain under investigation (5-7, 13, 15, 19).

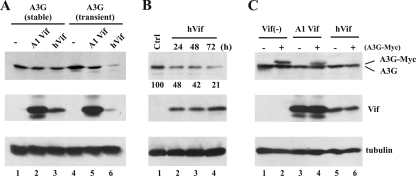

Here, we wanted to compare the effects of human immunodeficiency virus type 1 (HIV-1) Vif on the intracellular stability and virus encapsidation of stable versus transiently expressed APOBEC3G. APOBEC3G found in naturally APOBEC3G-positive cells and in stable HeLa cells is relatively “old,” due to the long half-life of the protein and the low rate of de novo synthesis (16, 24). With time, APOBEC3G tends to transition from a low-molecular-mass configuration to a high-molecular-mass ribonucleoprotein complex (21), and we hypothesized that old APOBEC3G might exist predominantly in a complex with cellular proteins or RNAs, while transiently expressed “new” APOBEC3G may not yet have undergone complete transition. As a result, old and new APOBEC3G might exhibit differential sensitivities to HIV-1 Vif. We took advantage of a HeLa cell line stably expressing wild-type untagged old APOBEC3G (HeLa-A3G) (16) and compared its sensitivity to degradation by Vif to that of new APOBEC3G in transiently transfected HeLa cells (Fig. 1A). Stable HeLa-A3G cells were transfected with pNL-A1 or pcDNA-hVif for the expression of Vif from subviral or codon-optimized vectors, respectively (18, 23) (Fig. 1A, lanes 2 and 3). Untransfected HeLa-A3G cells were analyzed in parallel (Fig. 1A, lane 1). For comparison, normal HeLa cells were transiently transfected with pcDNA-A3G in the absence of Vif (Fig. 1A, lane 4) or together with pNL-A1 or pcDNA-hVif (Fig. 1A, lanes 5 and 6). Immunoblot analysis revealed that old APOBEC3G from stable HeLa cells was resistant to degradation, while transiently expressed APOBEC3G, albeit relatively insensitive to pNL-A1 Vif, was efficiently degraded by pcDNA-hVif. The relative insensitivity of APOBEC3G to pNL-A1 Vif compared to that to pcDNA-hVif —despite higher levels of pNL-A1 Vif—was reported previously (5). We concluded that old APOBEC3G in stable HeLa-A3G cells is indeed less sensitive to degradation by pcDNA-hVif than transiently expressed new APOBEC3G.

FIG. 1.

Sensitivity of old and new APOBEC3G to degradation by HIV-1 Vif. (A) HeLa-A3G cells (5 × 106) stably expressing human APOBEC3G (A3G; lanes 1 to 3) were transfected with 1 μg each of empty vector DNA (−), pNL-A1 (A1 Vif), or pcDNA-hVif (hVif), using Lipofectamine Plus reagent (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA). In parallel, normal HeLa cells (lanes 4 to 6) were transfected with 0.5 μg of pcDNA-A3G together with 1 μg each of empty vector DNA, pNL-A1, or pcDNA-hVif. In this and all subsequent experiments, the total amount of transfected DNA was adjusted to 5 μg, using empty-vector DNA as appropriate. Cells were harvested 24 h posttransfection. Whole-cell lysates were separated by sodium dodecyl sulfate-12.5% polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis and analyzed by immunoblotting, using an APOBEC3G-specific antibody (top panel), a Vif monoclonal antibody (middle panel), or an antitubulin antibody (bottom panel). (B) HeLa-A3G cells were transfected with 5 μg of pcDNA-hVif (lanes 2 to 4). Lane 1 is a control of mock-transfected cells. Cells were harvested at 24 (lanes 1 and 2), 48 (lane 3), or 72 (lane 4) h, and cell lysates were subjected to immunoblotting as in panel A. Bands were quantified and corrected for fluctuations in tubulin levels. Results are shown below the A3G panel. Values are expressed as percentages of the Vif− [Vif(−)] control (lane 1). (C) HeLa-A3G cells were transfected with 0.5 μg of GFP-expressing plasmid (pEGFP), along with 0.5 μg of pcDNA-A3G-MycHis (A3G-Myc) in the absence or presence of 1 μg of pNL-A1 or pcDNA-hVif. Cells were harvested 24 h later and sorted for GFP-positive cells, using a FACSAria cell sorter (BD Biosciences Immunocytometry, San Jose, CA). Cell sorting was performed on live cells suspended in phosphate-buffered saline. The instrument setup was performed according to the manufacturer's instructions. All sorts were performed at 70 lb/in2. GFP-positive cells were lysed in sample buffer. Lysates from an equal number of cells were analyzed by immunoblotting as in panel A.

To rule out the possibility that APOBEC3G in stable HeLa-A3G cells is inherently resistant to degradation by Vif, HeLa-A3G cells were transfected with fivefold-increased amounts (5 μg) of pcDNA-hVif and incubated for extended times (up to 72 h) prior to protein analysis. As shown in Fig. 1B, APOBEC3G in stable HeLa-A3G cells was sensitive to degradation by pcDNA-hVif under these conditions (Fig. 1B, compare lanes 1 to lanes 2 to 4). Thus, old APOBEC3G is in principle sensitive to degradation when Vif is overexpressed and when the experiment was extended beyond our standard 24-h observation period.

It is unlikely that the relative insensitivity of APOBEC3G to Vif in stable HeLa-A3G cells as shown in Fig. 1A was due to poor transfection efficiency of our Vif-expression vectors. To formally rule out such a possibility, we enriched transfected cells by fluorescence-activated cell sorting (Fig. 1C). To further minimize technical artifacts, we compared the effects of Vif on the stability of old and new APOBEC3G in the same cells. A3G-Myc, which migrates more slowly in gels than untagged APOBEC3G due to the presence of an epitope tag, was used for transient expression in stable HeLa-A3G cells for direct comparison of new and old APOBEC3G. Specifically, HeLa-A3G cells were cotransfected with vectors encoding green fluorescent protein (GFP; for sorting) and A3G-Myc (Fig. 1C, lanes 2, 4, and 6) and either pNL-A1 Vif (Fig. 1C, lanes 3 and 4) or pcDNA-hVif (Fig. 1C, lanes 5 and 6). Empty-vector DNA was used in Vif− samples (Fig. 1C, lanes 1 and 2). As can be seen in Fig. 1C, transiently expressed A3G-Myc in GFP-positive cells was exquisitely sensitive to pcDNA-hVif -induced degradation (Fig. 1C, compare lanes 2 and 6) and to a lesser extent to pNL-A1 Vif (Fig. 1C, lane 4), whereas stable APOBEC3G was largely resistant to pNL-A1 Vif and pcDNA-hVif (Fig. 1C, compare lanes 1, 3, and 5). Similar results were observed for the reverse experiment, where untagged APOBEC3G was transiently transfected into stable HeLa-A3G-Myc cells (data not shown). These results confirm that even when coexpressed in the same cell as old APOBEC3G, new APOBEC3G is more sensitive to degradation by Vif than old APOBEC3G.

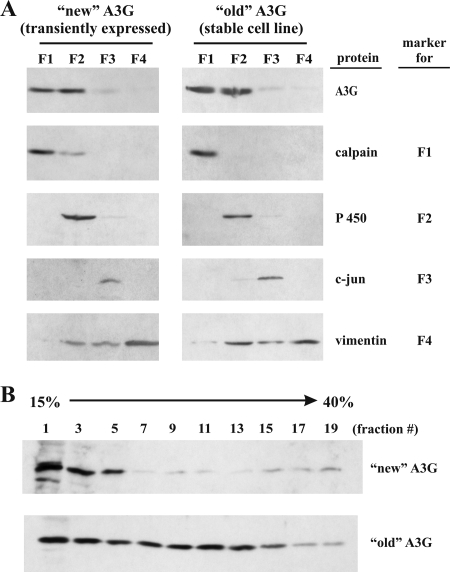

To assess gross differences in the subcellular distribution of stable and transiently expressed APOBEC3G, we performed cell fractionation (Fig. 2A). We employed a commercial cell fractionation kit (EMD Chemicals Inc., Gibbstown, NJ) to separate cytoplasmic (F1) from membrane (F2), nuclear (F3), and cytoskeletal (F4) compartments. As can be seen in Fig. 2A, the marker proteins recommended by the manufacturer were largely restricted to their respective compartments, attesting to the efficiency of the fractionation procedure. The only exception was vimentin, which not only partitioned to the cytoskeletal fraction (F4) but spilled over to some extent into fractions F2 and F3. APOBEC3G equally partitioned between fractions F1 and F2. Only minute quantities were found in the nuclear fraction (F3), and the protein was absent from the cytoskeletal fraction (F4). It is not clear whether the APOBEC3G identified in fraction F2 in this experiment reflects true membrane localization or is caused by incomplete extraction of the protein. Importantly, however, we did not observe any gross differences between transiently expressed APOBEC3G (Fig. 2A, left panel) and stable APOBEC3G (Fig. 2A, right panel) that might explain the differential sensitivity to Vif-induced degradation.

FIG. 2.

Localization and characterization of old versus new APOBEC3G in HeLa cells. (A) HeLa cells (left panel) were transfected with 5 μg of pcDNA-A3G. Cell fractionation was performed 24 h later, using a ProteoExtract subcellular proteome extraction kit (EMD Chemicals Inc., Gibbstown, NJ) according to the manufacturer's instructions. HeLa-A3G cells (right panel) were analyzed in parallel. Proteins from individual fractions were analyzed by immunoblotting, using antibodies to APOBEC3G (A3G), calpain-1/2 as a cytoplasmic marker (EMD Chemicals Inc., Gibbstown, NJ), cytochrome P450 reductase (P 450) as a membrane marker (Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Inc., Santa Cruz, CA), c-Jun as a nuclear marker (c-jun; BD Biosciences Immunocytometry, San Jose, CA), and vimentin as a cytoskeletal marker (Sigma Aldrich, Inc., St. Louis, MO). (B) APOBEC3G from stable HeLa-A3G cells and normal HeLa cells transiently transfected with pcDNA-A3G was fractionated on a 15 to 40% sucrose gradient as described previously (3). Nineteen fractions (550 μl each) were collected from the top of the gradient, and odd-numbered fractions were analyzed by immunoblotting, using an APOBEC3G-specific antibody.

APOBEC3G is known to transition from low-molecular-mass to high-molecular-mass complexes within 30 to 60 min after synthesis (21). We fractionated APOBEC3G from stable or transiently transfected HeLa cells on 15 to 40% sucrose gradients as described previously (3) to identify possible differences between old and new APOBEC3G with regard to the formation of intracellular complexes (Fig. 2B). Indeed, we observed that old APOBEC3G had a greater propensity to assemble into high-molecular-mass complexes than transiently expressed APOBEC3G (Fig. 2B, compare fractions 15 to 19). These results suggest that the APOBEC3G population present in stable HeLa cells is qualitatively distinct from that in transiently transfected HeLa cells.

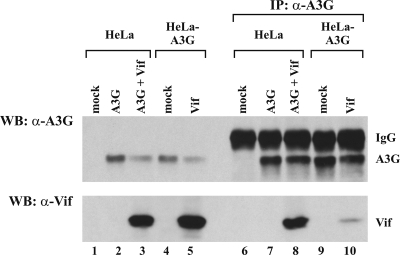

The relative resistance of old APOBEC3G to Vif-induced degradation could be due to the limited access of Vif to APOBEC3G in the cells. To test this possibility, we performed coimmunoprecipitations of Vif with APOBEC3G. For that purpose, HeLa cells were transiently transfected with pcDNA-A3G in the absence or presence of Vif (Fig. 3, lanes 2 and 3 and 7 and 8). Mock-transfected HeLa cells were included as controls (Fig. 3, lanes 1 and 6). In parallel, stable HeLa-A3G cells were transfected with empty vector (mock) or with pcDNA-hVif (Fig. 3, lanes 4 and 5 and 9 and 10). To prevent degradation of APOBEC3G by Vif, all samples were cotransfected with a dominant negative Cul5 mutant (Cul5-Rbx). Cell lysates were prepared 24 h later and were analyzed either directly (Fig. 3, lanes 1 to 5) or following immunoprecipitation by an APOBEC3G-specific antibody. As can be seen, old APOBEC3G from stable HeLa cells and new APOBEC3G from transiently transfected HeLa cells were expressed at comparable levels and were precipitated with similar efficiencies by the APOBEC3G-specific antibody. Samples expressing Vif had somewhat lower levels of APOBEC3G, presumably due to the incomplete inhibition of APOBEC3G degradation by Cul5-Rbx. Interestingly, Vif coprecipitated much less efficiently with old APOBEC3G (Fig. 3, lane 10) than with new APOBEC3G (Fig. 3, lane 8). These results suggest that the reduced sensitivity of old APOBEC3G to Vif could be due to a weaker interaction with Vif protein.

FIG. 3.

Vif interacts more efficiently with new than with old APOBEC3G. HeLa cells were transiently transfected with pcDNA-A3G (A3G; 0.5 μg) in the absence of Vif (lanes 2 and 7) or together with 1.5 μg of pcDNA-hVif (A3G + Vif; lanes 3 and 8). In parallel, stable HeLa-A3G cells were transfected without (mock; lanes 4 and 9) or together with 1.5 μg of pcDNA-hVif (Vif; lanes 5 and 10). Mock-transfected HeLa cells were analyzed as controls (lanes 1 and 6). To prevent degradation of APOBEC3G, the dominant negative Cul5-Rbx mutant (1 μg) was included in all samples. The cells were lysed 24 h posttransfection, using NP-40 lysis buffer. Cell lysates were either analyzed directly (lanes 1 to 5) or were first immunoprecipitated, using an APOBEC3G-specific antibody (α-A3G; lanes 6 to 10). Samples were probed with antibodies to APOBEC3G (top panel) or Vif (α-Vif; lower panel). Proteins are identified on the right. IP, immunoprecipitation; WB, Western blot; IgG, immunoglobulin G.

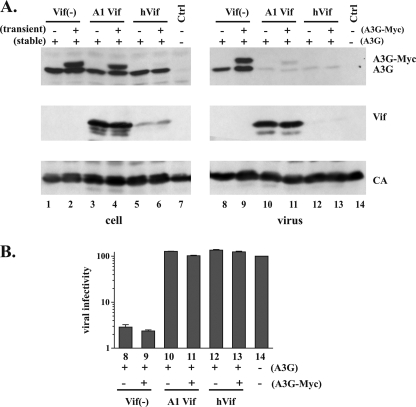

To investigate whether the differential sensitivities of old and new APOBEC3G to degradation by Vif is also reflected in a sensitivity of APOBEC3G encapsidation to inhibition by Vif, we compared the relative packaging efficiencies of old and new APOBEC3G expressed in the same cell into HIV-1 virions in the presence or absence of Vif. HeLa-A3G cells stably expressing untagged APOBEC3G were transfected with a vector encoding Myc-tagged APOBEC3G along with vif-defective pNL4-3 (8) and either pNL-A1 Vif or pcDNA-hVif vectors (Fig. 4). Newly transfected APOBEC3G was efficiently degraded by pcDNA-hVif, while old APOBEC3G was insensitive to degradation by pcDNA-hVif (Fig. 4A, compare lanes 2 and 6). Again, pNL-A1 Vif had little impact on the stability of either form of APOBEC3G (Fig. 4A, compare lanes 2 and 4), and both forms of APOBEC3G were equally well packaged into HIV viruses in the absence of Vif (Fig. 4, compare lanes 2 and 9). Surprisingly, despite their differential sensitivities to degradation, both old and new APOBEC3Gs were effectively excluded from HIV-1 virions by pNL-A1 Vif and pcDNA-hVif alike (Fig. 4A, lanes 10 to 13). These results demonstrate that despite their differential sensitivities to degradation, both preexisting APOBEC3G and newly synthesized protein can be efficiently encapsidated into viral particles in the absence of Vif but are effectively excluded when Vif is present.

FIG. 4.

(A) Cellular expression and packaging of old versus new APOBEC3G. HeLa-A3G cells were transfected with 0.5 μg of pcDNA-A3G-MycHis (even lane numbers) along with 3 μg of vif-defective pNL4-3 in the absence of Vif [Vif(−); lanes 1 and 2 and 7 and 8] or in the presence of 1 μg of pNL-A1 (A1 Vif; lanes 3 and 4 and 9 and 10) or pcDNA-hVif (hVif; lanes 5 and 6 and 11 and 12). Cells were harvested 24 h posttransfection and lysed in sample buffer. Virus-containing supernatant was concentrated by passing pellets through 20% sucrose. Cell and viral lysates were analyzed by immunoblotting with antibodies to APOBEC3G (A3G; top panel), Vif (middle panel), or an HIV-positive patient serum (CA; lower panel). Ctrl, control. (B) Virus-containing supernatants from transfected cultures were collected 24 h after transfection, normalized for reverse transcriptase activity, and used for the infection of LuSIV indicator cells. The relative infectivities of the viruses were determined by measuring the virus-induced expression of luciferase in the LuSIV cells 24 h later. The lane numbers correspond to those in panel A.

To determine the relative infectivities of the viruses produced in the experiment shown in Fig. 4A, virus-containing supernatants from transfected cultures were collected 24 h after transfection, normalized for reverse transcriptase activity, and used for the infection of LuSIV-indicator cells (Fig. 4B). The relative infectivities of the viruses were determined by measuring the virus-induced expression of luciferase in the indicator cells 24 h later, as previously reported (6). The infectivity of virus produced in the absence of APOBEC3G and Vif was defined as 100% (Fig. 4B, lane 14). As expected, the infectivity of viruses produced in the absence of Vif was low (Fig. 4B, lane 8). Additional transient expression of APOBEC3G caused only a minimal further reduction in viral infectivity (Fig. 4B, lane 9). Coexpression of pNL-A1 Vif and pcDNA-hVif completely restored viral infectivity to the level of a control virus produced in the absence of APOBEC3G (Fig. 4B, compare lanes 10 through 13 with lane 14). The results from this experiment are consistent with our previous findings involving degradation-resistant APOBEC3G (5) and suggest that degradation of APOBEC3G by Vif is functionally separable from its inhibition of APOBEC3G encapsidation and recovery of viral infectivity (19).

In this study, we demonstrated that Vif preferentially targets transiently expressed APOBEC3G that presumably has not yet completed its transition from an immature to a mature configuration, a process that presumably involves assembly of APOBEC3G into high-molecular-mass complexes. It is interesting to note that high-molecular-mass complexes can be destroyed by treatment with RNase (1) and that RNase treatment increases the interaction of Vif with APOBEC3G (9). Together, these results could explain why Vif preferentially targets newly synthesized APOBEC3G. Surprisingly, we found that new and old APOBEC3G were packaged into HIV-1 virions with very similar efficiencies. These results differ from those of an earlier study that reported that virion APOBEC3G is mainly recruited from the cellular pool of newly synthesized APOBEC3G (21). Most, if not all, cells stably expressing APOBEC3G (including HeLa-A3G cells) contain a mixture of high- and low-molecular-mass APOBEC3G. It is therefore not possible for us to determine whether the old APOBEC3G packaged into HIV-1 virions in our experiments came from a pool of low-molecular-mass APOBEC3G or from high-molecular-mass complexes (or both). Our finding that old APOBEC3G is more resistant to degradation than newly synthesized protein has important implications for the degradation-independent inhibition of APOBEC3G encapsidation by Vif early after infection, when APOBEC3G has not yet been eliminated from the cell by degradation. We have previously found that virus produced under such conditions is fully infectious (5, 17, 19). Thus, Vif's ability to exclude APOBEC3G from virions in a degradation-independent manner is a critical function of the viral accessory protein.

Acknowledgments

We thank Amy Andrew, Sandra Kao, and Robert Walker for helpful discussions and critical reviews of the manuscript. We very much appreciate Jason Brenchley's help with cell sorting. We thank Michael Malim for the Vif monoclonal antibody (MAb no. 319) and Jason Roos and Janice Clements for the LuSIV-indicator cell line. Both reagents were obtained through the NIH AIDS Research and Reference Reagent Program.

This work was supported by a grant from the NIH Intramural AIDS Targeted Antiviral Program to K.S. and by the Intramural Research Program of the NIAID, NIH.

Footnotes

Published ahead of print on 12 November 2008.

REFERENCES

- 1.Chiu, Y. L., V. B. Soros, J. F. Kreisberg, K. Stopak, W. Yonemoto, and W. C. Greene. 2005. Cellular APOBEC3G restricts HIV-1 infection in resting CD4+ T cells. Nature 435108-114. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Conticello, S. G., R. S. Harris, and M. S. Neuberger. 2003. The Vif protein of HIV triggers degradation of the human antiretroviral DNA deaminase APOBEC3G. Curr. Biol. 132009-2013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Goila-Gaur, R., M. Khan, E. Miyagi, S. Kao, S. Opi, H. Takeuchi, and K. Strebel. 2008. HIV-1 Vif promotes the formation of high molecular mass APOBEC3G complexes. Virology 372136-146. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Harris, R. S., K. N. Bishop, A. M. Sheehy, H. M. Craig, S. K. Petersen-Mahrt, I. N. Watt, M. S. Neuberger, and M. H. Malim. 2003. DNA deamination mediates innate immunity to retroviral infection. Cell 113803-809. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kao, S., R. Goila-Gaur, E. Miyagi, M. A. Khan, S. Opi, H. Takeuchi, and K. Strebel. 2007. Production of infectious virus and degradation of APOBEC3G are separable functional properties of human immunodeficiency virus type 1 Vif. Virology 369329-339. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kao, S., M. A. Khan, E. Miyagi, R. Plishka, A. Buckler-White, and K. Strebel. 2003. The human immunodeficiency virus type 1 Vif protein reduces intracellular expression and inhibits packaging of APOBEC3G (CEM15), a cellular inhibitor of virus infectivity. J. Virol. 7711398-11407. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kao, S., E. Miyagi, M. A. Khan, H. Takeuchi, S. Opi, R. Goila-Gaur, and K. Strebel. 2004. Production of infectious human immunodeficiency virus type 1 does not require depletion of APOBEC3G from virus-producing cells. Retrovirology 127. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Karczewski, M. K., and K. Strebel. 1996. Cytoskeleton association and virion incorporation of the human immunodeficiency virus type 1 Vif protein. J. Virol. 70494-507. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kozak, S. L., M. Marin, K. M. Rose, C. Bystrom, and D. Kabat. 2006. The anti-HIV-1 editing enzyme APOBEC3G binds HIV-1 RNA and messenger RNAs that shuttle between polysomes and stress granules. J. Biol. Chem. 28129105-29119. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Lecossier, D., F. Bouchonnet, F. Clavel, and A. J. Hance. 2003. Hypermutation of HIV-1 DNA in the absence of the Vif protein. Science 3001112. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Liu, B., X. Yu, K. Luo, Y. Yu, and X. F. Yu. 2004. Influence of primate lentiviral Vif and proteasome inhibitors on human immunodeficiency virus type 1 virion packaging of APOBEC3G. J. Virol. 782072-2081. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Mangeat, B., P. Turelli, G. Caron, M. Friedli, L. Perrin, and D. Trono. 2003. Broad antiretroviral defence by human APOBEC3G through lethal editing of nascent reverse transcripts. Nature 42499-103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Mariani, R., D. Chen, B. Schrofelbauer, F. Navarro, R. Konig, B. Bollman, C. Munk, H. Nymark-McMahon, and N. R. Landau. 2003. Species-specific exclusion of APOBEC3G from HIV-1 virions by Vif. Cell 114:21-31. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Marin, M., K. M. Rose, S. L. Kozak, and D. Kabat. 2003. HIV-1 Vif protein binds the editing enzyme APOBEC3G and induces its degradation. Nat. Med. 91398-1403. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Mehle, A., B. Strack, P. Ancuta, C. Zhang, M. McPike, and D. Gabuzda. 2004. Vif overcomes the innate antiviral activity of APOBEC3G by promoting its degradation in the ubiquitin-proteasome pathway. J. Biol. Chem. 2797792-7798. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Miyagi, E., S. Opi, H. Takeuchi, M. Khan, R. Goila-Gaur, S. Kao, and K. Strebel. 2007. Enzymatically active APOBEC3G is required for efficient inhibition of human immunodeficiency virus type 1. J. Virol. 8113346-13353. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Miyagi, E., F. Schwartzkopff, R. Plishka, A. Buckler-White, K. A. Clouse, and K. Strebel. 2008. APOBEC3G-independent reduction in virion infectivity during long-term HIV-1 replication in terminally differentiated macrophages. Virology 379266-274. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Nguyen, K. L., M. llano, H. Akari, E. Miyagi, E. M. Poeschla, K. Strebel, and S. Bour. 2004. Codon optimization of the HIV-1 vpu and vif genes stabilizes their mRNA and allows for highly efficient Rev-independent expression. Virology 319163-175. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Opi, S., S. Kao, R. Goila-Gaur, M. A. Khan, E. Miyagi, H. Takeuchi, and K. Strebel. 2007. Human immunodeficiency virus type 1 Vif inhibits packaging and antiviral activity of a degradation-resistant APOBEC3G variant. J. Virol. 818236-8246. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Sheehy, A. M., N. C. Gaddis, and M. H. Malim. 2003. The antiretroviral enzyme APOBEC3G is degraded by the proteasome in response to HIV-1 Vif. Nat. Med. 91404-1407. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Soros, V. B., W. Yonemoto, and W. C. Greene. 2007. Newly synthesized APOBEC3G is incorporated into HIV virions, inhibited by HIV RNA, and subsequently activated by RNase H. PLoS Pathog. 3e15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Stopak, K., C. de Noronha, W. Yonemoto, and W. C. Greene. 2003. HIV-1 Vif blocks the antiviral activity of APOBEC3G by impairing both its translation and intracellular stability. Mol. Cell 12591-601. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Strebel, K., D. Daugherty, K. Clouse, D. Cohen, T. Folks, and M. A. Martin. 1987. The HIV A (sor) gene product is essential for virus infectivity. Nature 328728-730. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Watashi, K., M. Khan, V. R. Yedavalli, M. L. Yeung, K. Strebel, and K.-T. Jeang. 2008. Human immunodeficiency virus type 1 replication and regulation of APOBEC3G by peptidyl prolyl isomerase Pin1. J. Virol. 829928-9936. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Yu, Q., R. Konig, S. Pillai, K. Chiles, M. Kearney, S. Palmer, D. Richman, J. M. Coffin, and N. R. Landau. 2004. Single-strand specificity of APOBEC3G accounts for minus-strand deamination of the HIV genome. Nat. Struct. Mol. Biol. 11435-442. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Yu, X., Y. Yu, B. Liu, K. Luo, W. Kong, P. Mao, and X. F. Yu. 2003. Induction of APOBEC3G ubiquitination and degradation by an HIV-1 Vif-Cul5-SCF complex. Science 3021056-1060. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Zhang, H., B. Yang, R. J. Pomerantz, C. Zhang, S. C. Arunachalam, and L. Gao. 2003. The cytidine deaminase CEM15 induces hypermutation in newly synthesized HIV-1 DNA. Nature 42494-98. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]