Abstract

Biofilm formation is an example of a multicellular process which depends on cooperative behavior and differentiation within a bacterial population. Our findings indicate that there is a complex feedback loop that maintains the stoichiometry of the extracellular matrix and other proteins required for complex colony development by Bacillus subtilis. Analysis of the transcriptional regulation of two DegU-activated genes that are required for complex colony development by B. subtilis revealed additional involvement of global regulators that are central to controlling biofilm formation. Activation of transcription from both the yvcA and yuaB promoters requires DegU∼phosphate, but transcription is inhibited by direct AbrB binding to the promoter regions. Inhibition of transcription by AbrB is relieved when Spo0A∼phosphate is generated due to its known role in inhibiting abrB expression. Deletion of SinR, a key coordinator of motility and biofilm formation, enhanced transcription from both loci; however, no evidence of a direct interaction with SinR for either the yvcA or yuaB promoter regions was observed. The enhanced transcription in the sinR mutant background was subsequently demonstrated to be dependent on biosynthesis of the polysaccharide component that forms the major constituent of the B. subtilis biofilm matrix. Together, these findings indicate that a genetic network dependent on activation of both DegU and Spo0A controls complex colony development by B. subtilis.

Bacteria are able to differentiate and coordinate activity in their offspring to accomplish complex multicellular processes, such as sporulation, biofilm formation, and swarming motility (1, 34, 44). Such multicellular behaviors are optimally exhibited by undomesticated species of bacteria, and consistent with this, wild isolates of the gram-positive soil bacterium Bacillus subtilis grow in sessile communities called biofilms that appear to be complex colonies or air-liquid interface pellicles, whose phenotypic characteristics are a result of cooperative behavior and differentiation (1, 43). Unraveling how B. subtilis integrates environmental and regulatory signals to coordinate the complex decision-making processes that precede and control its diverse multicellular behaviors has progressed substantially since the first reports of the biofilm-forming ability of this organism in 2001 (5, 17). To date, several transcriptional regulators have been demonstrated to be regulators involved in the formation of a sessile community, and they were recently examined systematically (reference 22 and references therein). The contributions of four pairs of global regulators, Spo0A/AbrB, DegS/DegU, SinI/SinR, and SlrR/SlrA, now form the working model for how biofilm formation by B. subtilis is controlled (9, 24).

Biofilm formation, the transition from a free-swimming state to an adhered state, coincides with the production of an exopolymeric matrix that surrounds the sessile cells (6, 43). In B. subtilis two operons are essential for this process, an operon containing epsA to epsO (referred to below as the eps operon) and yqxM-sipW-tasA (referred to below as the yqxM operon) (4, 8, 18). The products of the eps operon direct the synthesis of the polysaccharide constituent of the extracellular matrix and encode a protein that disables the flagellum motor, rendering the cells nonmotile (3). TasA is a protein component of the extracellular matrix, and its correct localization depends on both SipW and YqxM activity (4, 36). SinR inhibits transcription of both the eps and yqxM operons by direct promoter binding (8, 20), an interaction that is disrupted by SinI, the antagonist of SinR (2, 20). The pleiotropic regulator AbrB is another negative regulator of biofilm formation (9, 18). AbrB represses transcription of the eps and yqxM operons via indirect and direct mechanisms, respectively (9, 18, 37). It additionally directly inhibits the transcription of the yxaAB operon, in which yxaB codes for a putative exopolysaccharide synthase that is able to restore biofilm formation by a sigB mutant when it is overexpressed (31). Both of these pathways are activated by Spo0A through its role in activating transcription of sinI and inhibiting transcription of abrB (9).

DegU is a response regulator which needs to be phosphorylated by its cognate sensor kinase, DegS, to activate biofilm formation (23, 42). Determination that DegU was required for production of the exopolymer poly-γ-glutamic acid, an extracellular polymer that can contribute to biofilm formation, indicated that DegU has further roles during biofilm formation (35). Recently, we and other workers have presented evidence demonstrating that DegU controls and discriminates between multicellular phenomena, including swarming motility, biofilm formation, and protease production, via a gradient in its phosphorylation level. Two novel DegU-regulated genes were identified; in strain NCIB3610 yvcA is required for complex colony architecture, and in strain ATCC 6051 yuaB is required for pellicle formation (23, 42). These genes encode a putative membrane-bound lipoprotein (YvcA) and a small secreted protein (YuaB), but the exact contribution that these two proteins make to biofilm formation is not understood yet.

Here we describe the complex, but strikingly similar, regulatory control of yvcA transcription and yuaB transcription. For both genes we show that Spo0A∼P exerts positive control through repressing abrB transcription, thus enabling DegU∼P-dependent activation of transcription. Direct binding of AbrB to both the yvcA and yuaB promoter regions was confirmed in vitro. We ascribe an indirect regulatory role to SinR since we observed that transcription of yvcA and yuaB is elevated in the absence sinR, but we have shown that SinR does not bind to the yvcA and yuaB promoter regions. The increased level of yvcA and yuaB transcription in the sinR mutant was shown to be dependent on production of the exopolysaccharide synthesized by the products of the eps operon, and it is proposed that an intermediate in the intracellular sugar nucleotide cascade that is involved in exopolysaccharide synthesis has a positive effect on transcription of yvcA and yuaB via a mechanism that so far has not been identified.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

General strain construction and growth conditions.

The B. subtilis strains used and constructed in this study are described in Table 1. Escherichia coli strain MC1061 [F′ lacIq lacZM15 Tn10 (tet)] was used for construction and maintenance of plasmids (Table 2). B. subtilis JH642 derivatives were generated by transformation of competent cells with plasmids using standard protocols (19). SPP1 phage transduction for introduction of DNA into B. subtilis NCIB3610 was conducted as described previously (21). Both E. coli and B. subtilis strains were routinely grown in Luria-Bertani (LB) medium (10 g NaCl per liter, 5 g yeast extract per liter, 10 g tryptone per liter) or MSgg medium (5 mM potassium phosphate and 100 mM morpholinepropanesulfonic acid [pH 7.0] supplemented with 2 mM MgCl2, 700 μM CaCl2, 50 μM MnCl2, 50 μM FeCl3, 1 μM ZnCl2, 2 μM thiamine, 0.5% glycerol, 0.5% glutamate, and appropriate amino acids at a final concentration of 50 μg ml−1 [5, 8]) at 37°C. When appropriate, antibiotics were used at the following concentrations: ampicillin, 100 μg ml−1; chloramphenicol, 5 μg ml−1; erythromycin, 5 μg ml−1; kanamycin, 25 μg ml−1; and spectinomycin, 100 μg ml−1. Growth of complex colonies and observation of colony architecture were performed essentially as described previously (5, 42).

TABLE 1.

B. subtilis strains used in this study

| Strain | Relevant genotype or descriptiona | Reference, source, or constructionb |

|---|---|---|

| JH642 | trpC2 pheA1 | 32 |

| NCIB3610 | Prototroph | BGSC |

| BAL679 | trpC2 pheA1 spo0A(D56N) (spec) | 17 |

| BAL373 | trpC2 pheA1 abrB::cat | Grossman lab collection |

| BAL2340 | trpC2 pheA1 epsA::pBL584(Φ[Pspac-hy-epsA-O]) (cat) | Lazazzera lab collection |

| BAL2423 | trpC2 pheA1 sinR::cat | Lazazzera lab collection |

| BAL2428 | trpC2 pheA1 epsG::pBL601 (spec) | Lazazzera lab collection |

| DS91 | NCIB3610 sinI::spec | 20 |

| DS93 | NCIB3610 sinIR::spec | 20 |

| W939 | ATCC 6051 yuaB::cat | 23 |

| NRS1314 | NCIB3610 degU::pBL204 (cat) | 42 |

| NRS1326 | NCIB3610 amyE::Pspank-hy-degU-lacI (spec) degU::pBL204 (cat) | 42 |

| NRS1327 | NCIB3610 amyE::Pspank-hy-degU146-lacI (spec) degU::pBL204 (cat) | 42 |

| NRS1390 | NCIB3610 yvcA::pNW34 (cat) | 42 |

| NRS1502 | NCIB3610 epsG::pBL601 (spec) | BAL2428 → 3610 |

| NRS1603 | trpC2 pheA1 thrC::PyvcA-lacZ (erm) | pNW209 → JH642 |

| NRS1608 | NCIB3610 thrC::PyvcA-lacZ (erm) | SPP1 NRS1603 → 3610 |

| NRS1628 | NCIB3610 thrC::PyvcA-lacZ (erm) sinR::cat | SPP1 BAL2423 → NRS1608 |

| NRS1631 | NCIB3610 thrC::PyvcA-lacZ (erm) spo0A(D56N) (spec) | SPP1 BAL679 → NRS1608 |

| NRS1644 | NCIB3610 thrC::PyvcA-lacZ (erm) abrB::cat | SPP1 BAL373 → NRS1608 |

| NRS1685 | NCIB3610 epsA::pBL584(Φ[Pspac-hy-epsA-O]) (cat) | SPP1 BAL2340 → 3610 |

| NRS1858 | trpC2 pheA1 sinR::kan | PCR → JH642 |

| NRS1859 | NCIB3610 sinR::kan | SPP1 NRS1858 → 3610 |

| NRS2051 | trpC2 pheA1 thrC::PyuaB-lacZ (erm) | pNW500 → JH642 |

| NRS2052 | NCIB3610 thrC::PyuaB-lacZ (erm) | SPP1 NRS2051 → 3610 |

| NRS2053 | NCIB3610 thrC::yuaB-lacZ (erm) spo0A(D56N) (spec) | SPP1 NRS2051 → NRS1545 |

| NRS2054 | NCIB3610 thrC::yuaB-lacZ (erm) epsG::spec | SPP1 NRS2051 → NRS1502 |

| NRS2055 | NCIB3610 thrC::yuaB-lacZ (erm) sinI::spec | SPP1 NRS2051 → DS91 |

| NRS2056 | NCIB3610 amyE::Pspank-hy-degU146-lacI (spec) degU::pBL204 (cat) thrC::yuaB-lacZ (erm) | SPP1 NRS2051 → NRS1327 |

| NRS2223 | NCIB3610 thrC::yuaB-lacZ (erm) sinR::kan | SPP1 NRS2051 → NRS1859 |

| NRS2224 | NCIB3610 thrC::yuaB-lacZ (erm) degU::pBL204 (cat) | SPP1 NRS2051 → NRS1314 |

| NRS2226 | NCIB3610 amyE::Pspank-hy-degU-lacI (spec) degU::pBL204 (cat) thrC::yuaB-lacZ (erm) | SPP1 NRS2051 → NRS1326 |

| NRS2228 | NCIB3610 thrC::yuaB-lacZ (erm) abrB::cat | SPP1 BAL373 → NRS2052 |

| NRS2230 | NCIB3610 thrC::yuaB-lacZ (erm) sinIR::spec | SPP1 NRS2051 → DS93 |

| NRS2231 | NCIB3610 thrC::yuaB-lacZ (erm) epsG::spec sinR::kan | SPP1 NRS1858 → NRS2054 |

| NRS2232 | NCIB3610 thrC::yuaB-lacZ (erm) epsA::pBL584(Φ[Pspac-hy-epsA-O]) (cat) | SPP1 NRS2051 → NRS1685 |

| NRS2233 | NCIB3610 thrC::yuaB-lacZ (erm) abrB::cat spo0A(D56N) (spec) | SPP1 BAL679 → NRS2228 |

| NRS2067 | NCIB3610 thrC::PyvcA-lacZ (erm) abrB::cat spo0A(D56N) (spec) | SPP1 BAL679 → NRS1644 |

| NRS2076 | NCIB3610 thrC::PyvcA-lacZ (erm) epsG::spec | SPP1 BAL2428 → NRS1608 |

| NRS2077 | NCIB3610 thrC::PyvcA-lacZ (erm) epsG::spec sinR::cat | SPP1 BAL2423 → NRS2076 |

| NRS2083 | NCIB3610 thrC::PyvcA-lacZ (erm) sinI::spec | SPP1 DS91 → NRS1608 |

| NRS2084 | NCIB3610 thrC::PyvcA-lacZ (erm) sinIR::spec | SPP1 DS93 → NRS1608 |

| NRS2097 | NCIB3610 yuaB::cat | SPP1 W939 → 3610 |

| NRS2283 | trpC2 pheA1 amyE::Phy-spank-yuaB (spec) | pNW518 → JH642 |

| NRS2299 | NCIB3610amyE::Phy-spank-yuaB-lacI (spec) yuaB::cat | NRS2283 → NRS2097 |

Drug resistance cassettes are indicated as follows: cat, chloramphenicol resistance; kan, kanamycin resistance; erm, erythromycin resistance; spec, spectinomycin resistance.

The direction of strain construction is indicated for DNA or the phage (SPP1) recipient strain.

TABLE 2.

Plasmids used in this study

| Plasmid | Description | Reference or source |

|---|---|---|

| pDG1663 | thrC integration plasmid | 14 |

| pDR111 | amyE integration plasmid | 7 |

| pQAB3W | Ptac abrB (in JM109) | 38 |

| pET28a(+) | PT7 His6 vector | Novagen |

| pSac-Kan | sacA integration plasmid | 28 |

| pMF502 | Pspac-hy-gfp | 13 |

| pNW90 | PIPTG(T7)sinR in pET28a(+) | This study |

| pNW209 | PyvcA240-lacZ in pDG1663 | This study |

| pNW500 | PyuaB-lacZ in pDG1663 | This study |

| pNW518 | amyE::Phy-spank-yuaB-lacI in pDR111 | This study |

Plasmid construction.

The 300-bp region upstream of the yuaB translational start site and the 240-bp region upstream of the yvcA translational start site were amplified from NCIB3610 genomic DNA using primer pairs NSW614/NSW615 and NSW408/NSW19, respectively (Table 3). The resulting PCR fragments were ligated into the BamHI and EcoRI sites located upstream of the lacZ gene in the thrC integration vector pDG1663 using the restriction sites incorporated in the primers to generate pNW500 (yuaB) and pNW209 (yvcA) (14) (Table 2). Plasmids pNW209 and pNW500 were introduced by selection for double-crossover recombination at the thrC locus into JH642 and transferred into the chromosome of NCIB3610 by phage transduction (Table 1).

TABLE 3.

Primers used in this study

| Primer | Target | Sequence (5′ to 3′)a | Positionb |

|---|---|---|---|

| NSW19 | yvcA | CGAGGCGAATTCGGATCCCCTGTCAGGGCAAGT | 36 to 50 |

| NSW50 | yqxM | TGGCGAATTCATAGACAAATCACACATTGTTTGATCA | −302 to −276 |

| NSW51 | yqxM | GCCAGAATTCGGATCCATCTTACCTCCTGTAAAACACTGTAA | −26 to −1 |

| NSW74 | yvcA | CGAGGCATGCTTATTTCTCCTTTTTATC | 709 to 726 |

| NSW368 | sinR | AGGAGGCTAGCTTGATTGGCCAGCGTATTAAACAATA | 1 to 26 |

| NSW369 | sinR | CTCCTCTCGAGCTACTCCTCTTTTTGGGATTTTCTCCAT | 309 to 336 |

| NSW408 | yvcA | CGAGGCGAATTCAGCCGGATGATACGGCT | −243 to −227 |

| NSW410 | yvcA | CGAGGCGAATTCcCAAATTCCGCCATGA | −121 to −106 |

| NSW416 | yvcA | CGAGGCGAATTCTGCCGCTGGATGATGT | −304 to −289 |

| NSW421 | recA | AAACTCACTGGCAGCGATATCG | −388 to −367 |

| NSW422 | recA | TCTATTTGTTTAAGAGCCATATCTAAG | 21 to 47 |

| NSW614 | yuaB | ATGCGAATTCTCAGCTGGAAAGCTCTAAAGC | −300 to −280 |

| NSW615 | yuaB | ATGCGGATCCGCGTTTCATAACAAAATTC | −8 to 8 |

| NSW626 | yuaB | AGCTAAGCTTCATTTTTTAGGGGGAATTTTGTTATG | 3 to −22 |

| NSW645 | yuaB | AACTGCATGCTTAGTTGCAACCGCAAGGCTGA | 543 to 525 |

The restriction enzyme sites used for cloning are underlined.

The primer annealing sites on the chromosome are relative to the A residue (position 1) of the ATG translational start codon.

Introduction of sinR into pET28a(+) to generate an N-terminal His6 tag fusion was achieved by amplification of the sinR coding region from the chromosome of NCIB3610 using primers NSW368 and NSW369 (Table 3). The resulting PCR product was ligated into the NheI and XhoI sites of pET28a(+) to generate pNW90 (Table 2). The plasmid was sequenced to ensure that PCR-generated mutations were not present.

Plasmid pNW518 (Table 2) used to complement the yuaB mutation was generated by amplifying the yuaB coding sequence, including the ribosome binding site, from NCIB3610 genomic DNA using primers NSW626 and NSW645 (Table 3). The resulting PCR fragment was introduced into pDR111 using the HindIII and SphI restriction sites incorporated into the primers. The plasmid was sequenced to ensure that the sequence was correct and was subsequently introduced into JH642 at the amyE locus to generate strain NRS2283 (Table 1).

Strain construction.

In order to delete sinR, long-flanking homology PCR based on a previously described method (27) was used. The region overlapping the translational start codon of sinR was amplified using primers NSW148 (5′-CAGGCGCTGAAAACCTTGTATCAACC-3′) and NSW149 (5′-ATCACCTCAAATGGTTCGCTGCCAATCAATGTCATCACCTTCC-3′), and the region overlapping the termination stop codon of sinR was amplified using primers NSW150 (5′-CGAGCGCCTACGAGGAATTTGTATCGGGAGTAGTGCCTGAGCAGAG-3′) and NSW151 (5′-GATGCAGCGGCTGCTGAAAAAATC-3′). The translational start is indicated by single underlining, and the translational termination codon is indicated by double underlining; bold type indicates sequences homologous to the primer sequences used to amplify the kanamycin resistance gene. The kanamycin resistance gene was amplified from plasmid pSac-Kan using primers NSW152 (5′-CAGCGAACCATTTGAGGTGATAGG-3′) and NSW153 (5′-CGATACAAATTCCTCGTAGGCGCTCGG-3′). The purified fragments were combined using a sinR 5′ PCR product/kanamycin resistance gene/sinR 3′ PCR product ratio of 1:2:1 in a PCR mixture containing primers NSW148 and NSW151 and LA Taq (TaKaRa). The resulting PCR fragment was transformed into competent JH642 cells, and the resulting colonies were screened by PCR to ensure that there was double recombination at the sinR locus (NRS1858). The mutated sinR gene was then transferred into NCIB3610 by phage transduction, with selection for kanamycin resistance (NRS1859).

β-Galactosidase assay.

Biofilm growth medium (LB medium supplemented with 124 mM potassium phosphate [pH 7.0], 15 mM ammonium sulfate, 3.4 mM sodium citrate, 1 mM MgSO4, and 0.1% glucose) was inoculated to obtain an optical density at 600 nm (OD600) of 0.01 using a preculture grown to an OD600 of ∼0.5 in LB medium. Cultures were grown in 250-ml Erlenmeyer flasks or in glass tubes (1.5 by 15 cm). When required, isopropyl-β-d-1-thiogalactopyranoside (IPTG) was added after 60 min of growth. At the time points indicated, the OD600 was determined and 500 μl of cell suspension was harvested by centrifugation. Each resulting cell pellet was stored at −20°C for subsequent enzymatic analysis, and the β-galactosidase assay was performed as described previously (29). On solid medium colonies were grown on MSgg medium plates containing 1.5% agar supplemented with threonine (40 μg/ml) for 18 h. The colonies were collected from each plate, suspended in 300 μl of Bug Buster Mastermix (Novagen), and incubated for 15 min at room temperature with gentle shaking. Subsequently, the cells were vortexed for 10 min after addition of glass beads to further disrupt the cells. The suspension was centrifuged at 16,000 × g for 20 min at 4°C to pellet the cell debris. The protein concentration of the cell lysate supernatant was determined using a Bradford protein assay (Pierce). β-Galactosidase activity (in Miller units) was calculated as described above relative to the protein concentration in the sample. The values presented below are the average β-galactosidase activities determined for six colonies isolated in three independent experiments and normalized to the protein concentration (in mg ml−1); the standard errors of the means are also indicated.

Purification of AbrB and SinR.

AbrB and His6-SinR were purified basically by using previously described procedures (20, 38). The His6 tag of His6-SinR was removed using Novagen's thrombin cleavage capture kit.

Electrophoretic mobility shift assay.

Protein-DNA gel shift assays were performed with purified SinR and AbrB. The promoter regions assessed were the region from bp −300 to 8 for yuaB (generated using primers NSW617 and NSW618), the regions from bp −304 to 50 (generated using primers NSW416 and NSW19) and from bp −121 to 50 (generated using primers NSW410 and NSW19) for yvcA (P300 and P120), the region from bp −302 to −1 (generated using primers NSW50 and NSW51) for yqxM as a positive control, and (for AbrB) the region from bp −388 to 47 bp (generated using primers NSW421 and NSW422) for recA as a negative control. The positions are relative to the translation start codon, and the A of the ATG codon represented bp 1. 32P-labeled PCR fragments were generated by labeling one primer per primer pair (Table 3) prior to PCR amplification using [γ-32P]ATP (Perkin Elmer) and T4 polynucleotide kinase (New England Biolabs). Binding reactions were conducted in 30-μl (total volume) mixtures for 20 min at room temperature. For SinR the reaction mixtures contained 10 mM Tris-HCl (pH 8.0), 1 mM MgCl2, 50 mM NaCl, 5% glycerol, 1 mM EDTA, 1 mM dithiothreitol, 50 ng μl−1 bovine serum albumin, 50 ng μl−1 poly(dI-dC), 0.5 to 1 ng 32P-labeled DNA, and the amounts of SinR indicated below. For AbrB the reaction mixtures contained 20 mM Tris-HCl (pH 8.0), 5 mM MgCl2, 100 mM KCl, 5% glycerol, 0.05% Nonidet P-40, 0.5 mM dithiothreitol, 50 ng μl−1 bovine serum albumin, 50 ng μl−1 poly(dI-dC), 0.5 to 1 ng 32P-labeled DNA, and the amounts of AbrB indicated below. Reaction samples (15 μl) were loaded onto a 5% polyacrylamide 0.5× Tris-borate-EDTA gel. Gels were run at 100 V, and after drying they were autoradiographed by exposure to a Fujifilm phosphorimaging plate or X-ray film.

RESULTS AND DISCUSSION

YuaB is required for complex colony architecture.

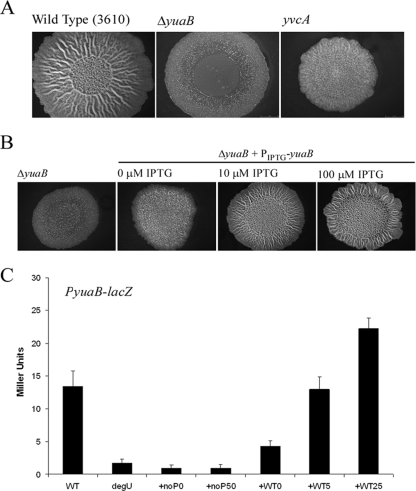

The DegU-regulated gene yuaB is required for pellicle formation by strain ATCC 6051 and is postulated to encode a small secreted protein (23). Transcription of yuaB was shown by Northern blot analysis to be enhanced in the presence of DegQ, a finding that indicates that yuaB is transcribed by DegU∼P (23). However, deletion of degS from ATCC 6051 and NCIB3610 results in different swarming motility phenotypes, indicating that there are differences in the DegU regulons of these two strains (23, 42). Additionally, ATCC 6051 has recently been found to differ from strain NCIB3610 (used in this study) at at least two locations in its genome, at least one of which influences biofilm formation (24, 25). Therefore, it was necessary to establish whether YuaB activates complex colony development by strain NCIB3610 and to assess if, like yvcA transcription, yuaB transcription was activated by DegU∼P, as DegU is known to have regulatory activity in both its nonphosphorylated and phosphorylated states (10). Highly consistent with the role of DegU and YuaB during pellicle formation in strain ATCC 6051, an NCIB3610-derived strain with a deletion in the single-gene operon yuaB (NRS2097) showed impaired complex colony architecture (Fig. 1A). Since the impact on complex colony architecture was greater than the impact on deletion of yvcA observed (42), this may indicate that yuaB encodes a protein required earlier in the complex colony development process than YvcA (Fig. 1A). The deletion phenotype was efficiently complemented by ectopic expression of the yuaB coding sequence under the control of a heterologous promoter from the amyE locus (Fig. 1B). While partial complementation was observed in the absence of IPTG, full complementation of the yuaB mutation was seen after addition of IPTG at concentrations of 10 and 100 μM. How YuaB functions is not known yet, but one hypothesis is that, like the secreted protein TasA (4), YuaB forms an additional structural component of the extracellular matrix. Alternatively, YuaB may form part of a feedback signaling cascade to regulate gene expression required for complex colony development by B. subtilis.

FIG. 1.

Complex colony architecture requires DegU-dependent yuaB transcription. (A) Complex colony morphology of wild-type strain NCIB3610, yuaB mutant NRS2097, and yvcA mutant NRS1390 after 48 h of incubation at 37°C on MSgg agar. (B) Complementation of yuaB mutant NRS2097 through ectopic expression of yuaB under control of a heterologous promoter (NRS2299). Strains were grown in the presence of IPTG as indicated at the top for 48 h at 37°C on MSgg agar. (C) Transcription of yuaB (PyuaB-lacZ) in wild-type strain NRS2052 (WT), degU mutant NRS2224, and the degU mutant complemented with the PIPTG-degU-D56N (NRS2056) and PIPTG-degU (NRS2226) constructs. The IPTG concentrations used were 0, 5, and 25 μM for the PIPTG-degU construct (+WT0, +WT5, and +WT25, respectively) and 0 and 50 μM for the PIPTG-degU-D56N construct (+noP0 and +noP50, respectively). The bars indicate the β-galactosidase activities and the error bars indicate the standard errors of the means obtained for stationary-phase cells in three to five independent experiments.

In line with previous findings for yvcA (42), transcription of yuaB was activated by DegU∼P when lacZ was used as an in vivo reporter of transcription using a 300-bp yuaB promoter region. Deletion of degU resulted in an eightfold decrease in yuaB transcription which could not be complemented by ectopic expression of a mutant allele of degU that cannot be phosphorylated due to a point mutation in the amino acid that is phosphorylated by DegS (degU-D56N) (Fig. 1C) (42). In contrast, ectopic expression of the wild-type degU gene under the control of the IPTG-inducible promoter Phy-spank (42) resulted in wild-type levels of yuaB expression after addition of 5 μM IPTG and levels slightly higher than the wild-type levels after addition of 25 μM IPTG (Fig. 1C). These data indicate that, like the overall complex colony development process, transcription of yuaB is activated by DegU∼P (23, 42).

AbrB represses transcription of yvcA and yuaB.

Only a limited number of genes that are known to be directly regulated by DegU have been characterized with respect to additional regulatory control, but what has become apparent from these studies is that multiple global regulators are involved (16, 33). For example, transcription of aprE, in addition to being activated by DegU, is controlled by SinR, AbrB, and Spo0A (2, 12). These regulators are all key players in the control of complex colony development by B. subtilis (5, 9, 17, 18, 22). Therefore, it was hypothesized that SinR, SinI, AbrB, and Spo0A may have a role in regulating the novel DegU-activated loci, yvcA and yuaB, that are also required for complex colony development (Fig. 1A). This possibility was addressed using mutant strains carrying lacZ as an in vivo reporter of either yvcA or yuaB transcription. For yvcA the 240-bp sequence upstream of the translational start site was used to drive lacZ transcription as this region of DNA has been defined as the optimal minimal yvcA promoter region (P240) (see Fig. S1 in the supplemental material).

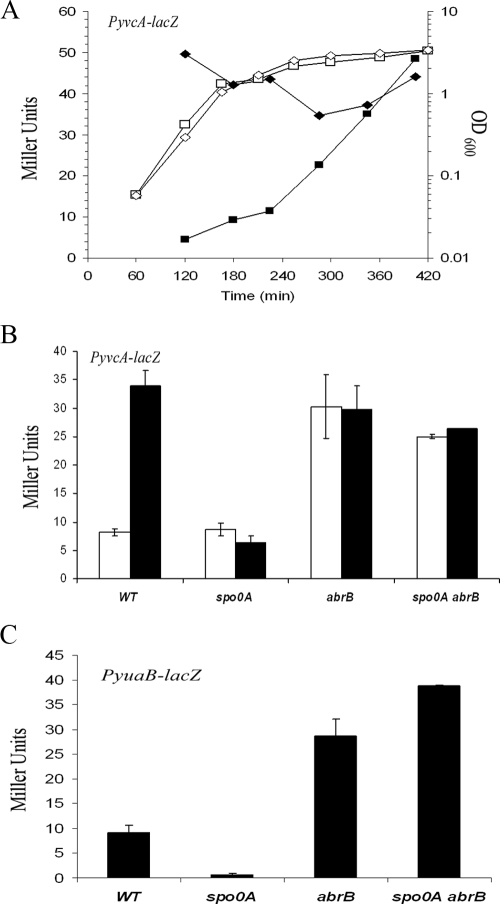

Introduction of a mutant allele of spo0A encoding a version of Spo0A that cannot be phosphorylated resulted in fivefold-decreased yvcA transcription during stationary phase (P < 0.01) (Fig. 2B). This finding is consistent with the role of Spo0A∼P in activating biofilm formation (5, 17). It was subsequently determined that the lack of yvcA transcription observed in the spo0A mutant was mediated through its known role in inhibiting abrB expression (17, 39). Consistent with this, yvcA transcription was observed to be constitutive in an abrB mutant strain, and the inhibition of transcription observed in the spo0A mutant was bypassed in the abrB spo0A double mutant strain (Fig. 2A and 2B). The same phenomenon was observed when transcription from the yuaB promoter was examined. Deletion of spo0A resulted in an 11-fold (P < 0.01) decrease in transcription. In the abrB and spoOA mutants, the level of transcription was four- to fivefold higher (P < 0.01) than the wild-type level, respectively (Fig. 2C). These data indicate that both yvcA and yuaB are regulated indirectly by Spo0A∼P through AbrB. Consistent with these findings, neither gene was identified as a direct target of Spo0A using chromatin immunoprecipitation experiments (30), but both genes were determined by genome-wide transcriptome analysis to be members of the larger spo0A regulon (11).

FIG. 2.

Transcription of yvcA and yuaB is activated by Spo0A∼P through abrB inhibition. (A) Transcription of yvcA (PyvcA-lacZ) in the wild-type (NRS1608) and abrB mutant (NRS1644) backgrounds. The symbols indicate the β-galactosidase activities (in Miller units) (filled symbols) and the growth (open symbols) expressed as OD600 for the wild-type strain (squares) and abrB mutant (diamonds) strain at different times. (B) Transcription of yvcA (PyvcA-lacZ) in the wild-type strain (NRS1608) (WT), the spo0A mutant (NRS1631), the abrB mutant (NRS1644), and the spo0A abrB mutant (NRS2067). The bars indicate the β-galactosidase activities (in Miller units) and the error bars indicate the standard errors of the means obtained for exponential-phase cells (120 min) (open bars) and for stationary-phase cells (360 min) (filled bars). (C) Transcription of yuaB (PyuaB-lacZ) in the wild-type strain (NRS2052), the spo0A mutant (NRS2053), the abrB mutant (NRS2228), and the spo0A abrB mutant (NRS2233). The bars indicate the β-galactosidase activities (in Miller units) and the error bars indicate the standard errors of the means obtained for stationary-phase cells (360 min).

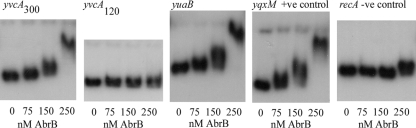

AbrB binds to the promoter region of yvcA and yuaB.

To establish that the AbrB-mediated repression of transcription was a direct regulatory event, DNA retardation assays with the yvcA and yuaB promoter regions and purified AbrB were performed. Using yqxM as a positive control (37) and the recA promoter region as a negative control (15), a direct interaction was demonstrated (Fig. 3). Addition of AbrB at a concentration of 150 nM was sufficient to initiate a promoter DNA-AbrB interaction, while complete yvcA and yuaB promoter binding was observed in the presence of 250 nM AbrB (Fig. 3). AbrB binding was not detected when only the 120-bp sequence upstream of the translational start site for yvcA, a region that also did not show any DegU∼P-activated transcription when it was fused with lacZ (see Fig. S1 in the supplemental material), was used. These data indicate that AbrB binds to the region between bp −120 and −240 upstream of the yvcA translational start site and binds within the 300-bp region upstream of the translation start site of yuaB, and they add yvcA and yuaB to the growing list of AbrB-inhibited targets that need to be derepressed for complex colony development to occur. These data highlight the key role that AbrB plays in controlling this multicellular behavior exhibited by B. subtilis (9, 17, 18, 31).

FIG. 3.

AbrB is a direct repressor of yvcA and yuaB transcription. An electrophoretic mobility shift assay was performed using 32P-labeled yvcA300, yvcA120, yuaB, yqxM, and recA promoter fragments incubated with AbrB at the concentrations indicated. +ve, positive; −ve, negative.

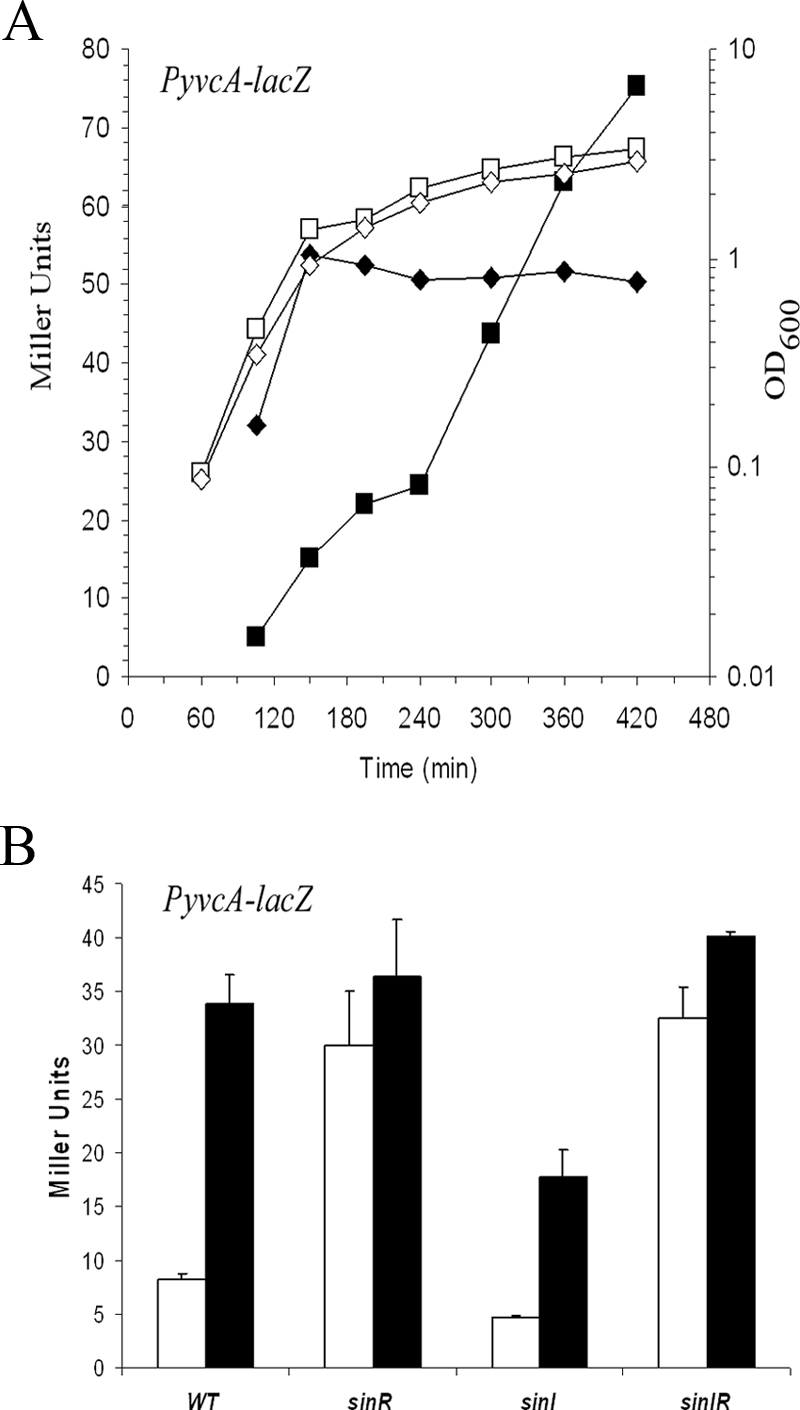

Deletion of sinR enhances transcription of yvcA and yuaB.

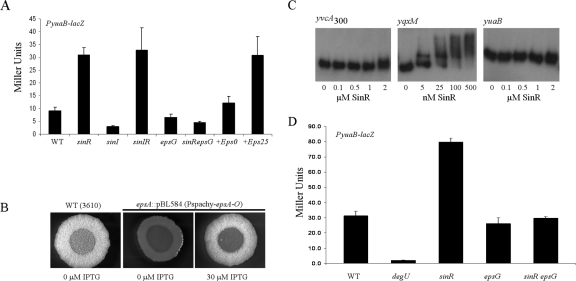

Consistent with the role of SinR as a repressor of complex colony architecture (20), deletion of sinR resulted in a fourfold increase in transcription from the yvcA promoter during exponential growth (Fig. 4A and 4B) and a fourfold (P < 0.01) increase in transcription from the yuaB promoter throughout growth compared with the wild-type strain (Fig. 5A). SinI is the antagonist of SinR (2), and consistent with this, deletion of sinI resulted in a twofold decrease in transcription for both the yvcA and yuaB promoters compared with the wild type (Fig. 4B and 5A). As expected, deletion of both sinR and its antagonist sinI in combination resulted in an increase in transcription similar to that observed for the single sinR deletion (Fig. 4B and 5A). We wanted to ensure that the fourfold-enhanced transcription was not the result of inaccurate assessment of the cell number (and therefore gene transcription) in the sinR and sinIR mutant strains as shaking cultures of the sinR and sinIR mutant strains do not have a uniform optical density due to overexpression of components of the biofilm matrix (20). We did not think that this was likely as we used an LB medium-based growth medium for our experiments, in which the final transcriptional level of the eps operon in the absence of the repressor sinR was suppressed (data not shown). Thus, in this growth medium, the cells still clumped but at a lower level than in MSgg medium (data not shown), and therefore, the growth could be followed (Fig. 2A and 4A). However, in order to eliminate any doubt, the level of expression from the yvcA promoter in the presence and absence of sinR was calculated after preparation of soluble-protein cell lysates. This allowed normalization of the β-galactosidase activity to protein levels. Using this approach, a 4.5-fold-higher level of yvcA transcription in the sinR mutant was still observed, indicating that the recorded values were not the result of inaccurate assessment of the cell number (see Fig. S2 in the supplemental material). Our findings indicate that SinR inhibits transcription of both the yvcA and yuaB DegU-activated promoters. To establish that it was a direct interaction, we used electrophoretic mobility shift assays with purified SinR (Fig. 5C). Using radiolabeled yvcA and yuaB promoter regions, we were unable to demonstrate any interaction of SinR with either promoter region in the nanomolar range needed to bind to the yqxM promoter, a known SinR target (Fig. 5C) (8, 20). Therefore, in contrast to the known role of SinR in repressing eps and yqxM operon transcription (4, 8, 20), these findings do not support a model in which the inhibition of yvcA and yuaB transcription by SinR is directly mediated.

FIG. 4.

Deletion of sinR enhances transcription of yvcA. (A) Transcription of yvcA (PyvcA-lacZ) in the wild-type background (NRS1608) and the sinR mutant (NRS1628). The symbols indicate the β-galactosidase activities (in Miller units) (filled symbols) and the growth (open symbols) expressed as OD600 for the wild-type strain (squares) and sinR mutant strain (diamonds) at different times. (B) Transcription of yvcA (PyvcA-lacZ) in the wild-type background (NRS1608), the sinR mutant (NRS1628), the sinI mutant (NRS2083), and the sinIR mutant (NRS2084). The bars indicate the β-galactosidase activities (in Miller units) and the error bars indicate the standard errors of the means obtained for exponential-phase cells (120 min) (open bars) and stationary-phase cells (360 min) (filled bars) for three to five experiments.

FIG. 5.

SinR is not a direct repressor of yuaB transcription. (A) Transcription of yuaB (PyuaB-lacZ) in the wild-type background (NRS2052) (WT), the sinR mutant (NRS2223), the sinI mutant (NRS2055), the sinIR mutant (NRS2230), the epsG mutant (NRS2054), the epsG sinR mutant (NRS2231), and the PIPTG-eps operon strain (NRS2232) with no IPTG (+Eps0) and 25 μM IPTG (+Eps25). The bars indicate the β-galactosidase activities (in Miller units) and the error bars indicate the standard errors of the means obtained for stationary-phase cells in three to five independent experiments. (B) Complex colony architecture can be restored to the epsA::pBL584(Φ[Pspachy-epsA-O]) strain (PIPTG-epsA-O) (NRS1685) in the presence of 30 μM IPTG after incubation for 24 h at 37°C on MSgg medium. (C) Electrophoretic mobility shift assay using 32P-labeled yvcA300, yqxM, and yuaB promoter fragments incubated with SinR at the concentrations indicated. (D) Transcription of yuaB (PyuaB-lacZ) in the wild-type (NRS2052), degU mutant (NRS2224), sinR mutant (NRS2223), epsG mutant (NRS2054), and epsG sinR mutant (NRS2231) backgrounds. The bars indicate the β-galactosidase activities (in Miller units) and the error bars indicate the standard errors of the means normalized to the total protein concentration (in mg ml−1) determined using colonies grown on MSgg medium for 18 h in three independent experiments.

Synthesis of the exopolysaccharide is required for enhanced transcription.

In the absence of a direct interaction of SinR with the yvcA and yuaB promoters, we postulated that the increase in transcription of yvcA and yuaB may be stimulated by the extracellular matrix or an intermediate in the biosynthetic process that is overproduced in both the sinR and sinIR mutants. To test this hypothesis, the level of transcription from the yvcA and yuaB promoters was measured in the presence of a mutation in the eps operon which prevents exopolysaccharide biosynthesis (20). In an epsG sinR mutant strain the yvcA transcription was equivalent to that of the wild-type strain (data not shown), and the yuaB transcription was 1.7-fold lower than that of the wild-type strain (Fig. 5A). These findings are consistent with the hypothesis that exopolysaccharide production stimulates transcription of these two DegU-activated loci. These experiments were conducted using cells grown in liquid LB medium-based growth medium, and we wanted to ensure that the same pattern of gene expression occurred under complex colony development conditions; therefore, we harvested colonies from solid MSgg medium after 18 h of growth. The level of β-galactosidase activity was normalized to the total amount of protein extracted from the colony. We observed a 2.5-fold increase (P < 0.0001) in yuaB transcription in the absence of sinR compared with the transcription in the wild-type strain (Fig. 5D) and confirmed that the increase in transcription was dependent on the production of the exopolymeric matrix since disruption of epsG in the sinR background resulted in loss of the enhanced level of transcription (Fig. 5D).

To further investigate the hypothesis that synthesis of the polysaccharide component of the biofilm matrix acted as a signal responsible for enhancing yvcA and yuaB transcription, transcription of the eps operon was uncoupled from native regulation by replacing the eps operon promoter with a construct that enabled transcription of the eps operon from an IPTG-inducible promoter. Substitution of the promoter region allowed wild-type colony morphology to be exhibited in the presence of 30 μM IPTG (Fig. 5B). Using the PIPTG-eps operon strain, the level of yuaB transcription was measured in the presence and absence of IPTG. Without addition of IPTG to cells carrying the PIPTG-eps operon construct, the transcription of yuaB during early stationary phase was not significantly different from that measured for the wild-type strain, but addition of 10 μM IPTG resulted in a small but statistically significant increase in transcription (1.7-fold; P < 0.01 [data not shown]). Addition of 25 μM IPTG increased transcription of yuaB 3.5-fold (P < 0.05) during stationary phase to levels comparable to those observed for the sinR mutant strain (Fig. 5A). These findings are consistent with the DNA retardation data which indicated that SinR does not bind to the yvcA and yuaB promoters and could explain why yvcA and yuaB were not identified as SinR-regulated genes in genome-wide transcriptional profiling studies since those analyses were performed using a sinR mutant strain carrying a mutation in the eps operon (8). In conclusion, our data indicate that either a product of the eps operon, the biofilm matrix itself, or some unidentified regulatory step that requires matrix production enhances transcription of yvcA and yuaB in the sinR mutant strain.

The exopolysaccharide is not an extracellular signal triggering enhanced yuaB transcription.

It is possible that the exopolysaccharide synthesized by the products of the eps operon could enhance transcription of yvcA and yuaB through recognition by a receptor on the cell surface, which in turn could trigger a signaling cascade within the cell. If this were the case, then overproduction of the exopolysaccharide would be detected for a strain that does not overproduce the exopolysaccharide when it is assessed in coculture experiments. To test this possibility, the level of transcription from the yuaB promoter fusion was measured for the wild-type strain that was cocultured at a 1:1 ratio with either the wild-type strain or the sinIR mutant strain that lacked the yuaB reporter fusion. It was established that the increased level of exopolysaccharide produced by the sinIR mutant did not result in enhanced transcription of yuaB in the wild-type strain, indicating that the exopolysaccharide did not function as an extracellular signaling molecule (data not shown). It is not known yet how overproduction of the extracellular polysaccharide enhances transcription of the yvcA and yuaB loci; however, one hypothesis favored by us is that carbohydrate intermediates in the polysaccharide biosynthetic process are detected intracellularly and used to mediate signal transduction processes. Detection of metabolic intermediates as a means to control gene expression can occur through the activity of trans-acting ribozymes, such as the glucosamine-6-phosphate-activated ribozyme encoded by glmS (26, 45).

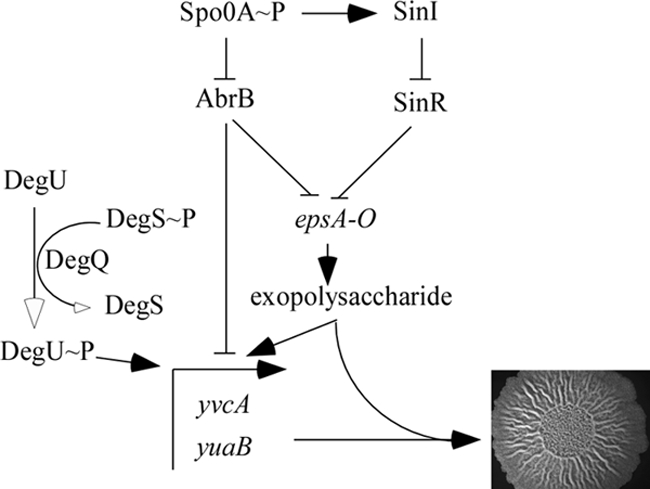

Conclusion.

AbrB and SinR are known for their role in inhibiting transcription of the eps and yqxM operons that are required for biosynthesis of the extracellular matrix of the B. subtilis biofilm (9, 20). Here we found that transcription of the DegU-activated genes yvcA and yuaB is also regulated by AbrB and SinR. While we were able to clearly demonstrate that the inhibition exerted by AbrB was directly mediated (Fig. 3), we surprisingly also demonstrated that the inhibition exerted by SinR was indirectly mediated through the exopolysaccharide synthesized by the protein products of the eps operon (Fig. 5). These findings indicate that a complex feedback loop is established during complex colony development by B. subtilis to ensure that the stoichiometry of yvcA and yuaB transcription is kept in balance with that of the eps and yqxM operons (Fig. 6). The dual requirements of DegU and Spo0A activation prior to complex colony development are comparable to the regulatory network required to activate exoprotease production by B. subtilis. Exprotease production occurs in a small subpopulation of cells that reach threshold levels of DegU∼P and Spo0A∼P (40, 41). Therefore, our findings add complex colony development to the growing list of multicellular behavioral phenomena exhibited by B. subtilis that are subjected to an “AND-gating genetic circuit” that depends on the activation of both DegU and Spo0A (40, 41). Future work will investigate how this regulatory loop is maintained and whether fluctuations in the absolute levels of DegU and Spo0A activation are used as a mechanism to coordinate entry into the different multicellular behaviors that are exhibited by B. subtilis.

FIG. 6.

A complex regulatory network controls biofilm formation. The diagram is a simplified diagram depicting the network that controls yvcA and yuaB transcription during complex colony development (5, 8, 9, 17, 20). Open arrowheads indicated changes in phosphorylation, filled arrowheads indicate activation of transcription, and T bars indicate inhibition of transcription.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by the Biotechnology and Biological Sciences Research Council (grants BB/C520404/1 and BB/E001572/1).

We thank The Sequencing Service (College of Life Sciences, University of Dundee, Dundee, Scotland) (www.dnaseq.co.uk) for DNA sequencing. We are very grateful to M. Strauch (University of Maryland) for providing the AbrB-overproducing E. coli strain and for his advice concerning AbrB purification. We thank D. Kearns (University of Indiana) for providing the sinI and sinIR strains and for helpful discussions, K. Kobayashi (NIST, Japan) for providing the yuaB mutant strain, Taryn Kiley (University of Dundee) for providing the sinR::kan strain, and B. Terra and B. Lazazzera (University of California, Los Angeles) for providing strain BAL2340 prior to publication and for helpful discussions.

Footnotes

Published ahead of print on 31 October 2008.

Supplemental material for this article may be found at http://jb.asm.org/.

REFERENCES

- 1.Aguilar, C., H. Vlamakis, R. Losick, and R. Kolter. 2007. Thinking about Bacillus subtilis as a multicellular organism. Curr. Opin. Microbiol. 10638-643. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bai, U., I. Mandic-Mulec, and I. Smith. 1993. SinI modulates the activity of SinR, a developmental switch protein of Bacillus subtilis, by protein-protein interaction. Genes Dev. 7139-148. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Blair, K. M., L. Turner, J. T. Winkelman, H. C. Berg, and D. B. Kearns. 2008. A molecular clutch disables flagella in the Bacillus subtilis biofilm. Science 3201636-1638. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Branda, S. S., F. Chu, D. B. Kearns, R. Losick, and R. Kolter. 2006. A major protein component of the Bacillus subtilis biofilm matrix. Mol. Microbiol. 591229-1238. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Branda, S. S., J. E. Gonzalez-Pastor, S. Ben-Yehuda, R. Losick, and R. Kolter. 2001. Fruiting body formation by Bacillus subtilis. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 9811621-11626. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Branda, S. S., S. Vik, L. Friedman, and R. Kolter. 2005. Biofilms: the matrix revisited. Trends Microbiol. 1320-26. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Britton, R. A., P. Eichenberger, J. E. Gonzalez-Pastor, P. Fawcett, R. Monson, R. Losick, and A. D. Grossman. 2002. Genome-wide analysis of the stationary-phase sigma factor (sigma-H) regulon of Bacillus subtilis. J. Bacteriol. 1844881-4890. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Chu, F., D. B. Kearns, S. S. Branda, R. Kolter, and R. Losick. 2006. Targets of the master regulator of biofilm formation in Bacillus subtilis. Mol. Microbiol. 591216-1228. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Chu, F., D. B. Kearns, A. McLoon, Y. Chai, R. Kolter, and R. Losick. 2008. A novel regulatory protein governing biofilm formation in Bacillus subtilis. Mol. Microbiol. 681117-1127. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Dahl, M. K., T. Msadek, F. Kunst, and G. Rapoport. 1992. The phosphorylation state of the DegU response regulator acts as a molecular switch allowing either degradative enzyme synthesis or expression of genetic competence in Bacillus subtilis. J. Biol. Chem. 26714509-14514. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Fawcett, P., P. Eichenberger, R. Losick, and P. Youngman. 2000. The transcriptional profile of early to middle sporulation in Bacillus subtilis. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 978063-8068. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ferrari, E., D. J. Henner, M. Perego, and J. A. Hoch. 1988. Transcription of Bacillus subtilis subtilisin and expression of subtilisin in sporulation mutants. J. Bacteriol. 170289-295. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Fujita, M., J. E. Gonzalez-Pastor, and R. Losick. 2005. High- and low-threshold genes in the Spo0A regulon of Bacillus subtilis. J. Bacteriol. 1871357-1368. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Guerout-Fleury, A. M., N. Frandsen, and P. Stragier. 1996. Plasmids for ectopic integration in Bacillus subtilis. Gene 18057-61. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Hamoen, L. W., D. Kausche, M. A. Marahiel, D. van Sinderen, G. Venema, and P. Serror. 2003. The Bacillus subtilis transition state regulator AbrB binds to the −35 promoter region of comK. FEMS Microbiol. Lett. 218299-304. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hamoen, L. W., G. Venema, and O. P. Kuipers. 2003. Controlling competence in Bacillus subtilis: shared use of regulators. Microbiology 1499-17. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Hamon, M. A., and B. A. Lazazzera. 2001. The sporulation transcription factor Spo0A is required for biofilm development in Bacillus subtilis. Mol. Microbiol. 421199-1209. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Hamon, M. A., N. R. Stanley, R. A. Britton, A. D. Grossman, and B. A. Lazazzera. 2004. Identification of AbrB-regulated genes involved in biofilm formation by Bacillus subtilis. Mol. Microbiol. 52847-860. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Harwood, C. R., and S. M. Cutting. 1990. Molecular biological methods for Bacillus. John Wiley &Sons Ltd., Chichester, England.

- 20.Kearns, D. B., F. Chu, S. S. Branda, R. Kolter, and R. Losick. 2005. A master regulator for biofilm formation by Bacillus subtilis. Mol. Microbiol. 55739-749. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kearns, D. B., and R. Losick. 2003. Swarming motility in undomesticated Bacillus subtilis. Mol. Microbiol. 49581-590. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kobayashi, K. 2007. Bacillus subtilis pellicle formation proceeds through genetically defined morphological changes. J. Bacteriol. 1894920-4931. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kobayashi, K. 2007. Gradual activation of the response regulator DegU controls serial expression of genes for flagellum formation and biofilm formation in Bacillus subtilis. Mol. Microbiol. 66395-409. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kobayashi, K. 2008. SlrR/SlrA control the initiation of biofilm formation in Bacillus subtilis. Mol. Microbiol. 691399-1410. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kobayashi, K., R. Kuwana, and H. Takamatsu. 2008. kinA mRNA is missing a stop codon in the undomesticated Bacillus subtilis strain ATCC 6051. Microbiology 15454-63. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Mandal, M., B. Boese, J. E. Barrick, W. C. Winkler, and R. R. Breaker. 2003. Riboswitches control fundamental biochemical pathways in Bacillus subtilis and other bacteria. Cell 113577-586. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Mascher, T., N. G. Margulis, T. Wang, R. W. Ye, and J. D. Helmann. 2003. Cell wall stress responses in Bacillus subtilis: the regulatory network of the bacitracin stimulon. Mol. Microbiol. 501591-1604. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Middleton, R., and A. Hofmeister. 2004. New shuttle vectors for ectopic insertion of genes into Bacillus subtilis. Plasmid 51238-245. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Miller, J. 1972. Experiments in molecular genetics. Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory, Cold Spring Harbor, NY.

- 30.Molle, V., M. Fujita, S. T. Jensen, P. Eichenberger, J. E. Gonzalez-Pastor, J. S. Liu, and R. Losick. 2003. The Spo0A regulon of Bacillus subtilis. Mol. Microbiol. 501683-1701. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Nagorska, K., K. Hinc, M. A. Strauch, and M. Obuchowski. 2008. Influence of the σΒ stress factor and yxaB, the gene for a putative exopolysaccharide synthase under σB control, on biofilm formation. J. Bacteriol. 1903546-3556. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Perego, M., G. B. Spiegelman, and J. A. Hoch. 1988. Structure of the gene for the transition state regulator, abrB: regulator synthesis is controlled by the spo0A sporulation gene in Bacillus subtilis. Mol. Microbiol. 2689-699. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Sanchez, A., and J. Olmos. 2004. Bacillus subtilis transcriptional regulators interaction. Biotechnol. Lett. 26403-407. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Shapiro, J. A. 1998. Thinking about bacterial populations as multicellular organisms. Annu. Rev. Microbiol. 5281-104. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Stanley, N. R., and B. A. Lazazzera. 2005. Defining the genetic differences between wild and domestic strains of Bacillus subtilis that affect poly-gamma-dl-glutamic acid production and biofilm formation. Mol. Microbiol. 571143-1158. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Stover, A. G., and A. Driks. 1999. Regulation of synthesis of the Bacillus subtilis transition-phase, spore-associated antibacterial protein TasA. J. Bacteriol. 1815476-5481. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Strauch, M. A., B. G. Bobay, J. Cavanagh, F. Yao, A. Wilson, and Y. Le Breton. 2007. Abh and AbrB control of Bacillus subtilis antimicrobial gene expression. J. Bacteriol. 1897720-7732. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Strauch, M. A., G. B. Spiegelman, M. Perego, W. C. Johnson, D. Burbulys, and J. A. Hoch. 1989. The transition state transcription regulator abrB of Bacillus subtilis is a DNA binding protein. EMBO J. 81615-1621. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Strauch, M. A., V. Webb, G. B. Spiegelman, and J. A. Hoch. 1990. The Spo0A protein of Bacillus subtilis is a repressor of the abrB gene. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 871801-1805. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Veening, J. W., O. A. Igoshin, R. T. Eijlander, R. Nijland, L. W. Hamoen, and O. P. Kuipers. 2008. Transient heterogeneity in extracellular protease production by Bacillus subtilis. Mol. Syst. Biol. 4184. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Veening, J. W., W. K. Smits, and O. P. Kuipers. 2008. Bistability, epigenetics, and bet-hedging in bacteria. Annu. Rev. Microbiol. 62193-210. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Verhamme, D. T., T. B. Kiley, and N. R. Stanley-Wall. 2007. DegU co-ordinates multicellular behaviour exhibited by Bacillus subtilis. Mol. Microbiol. 65554-568. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Vlamakis, H., C. Aguilar, R. Losick, and R. Kolter. 2008. Control of cell fate by the formation of an architecturally complex bacterial community. Genes Dev. 22945-953. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Voloshin, S. A., and A. S. Kaprelyants. 2004. Cell-cell interactions in bacterial populations. Biochemistry (Moscow) 691268-1275. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Winkler, W. C., A. Nahvi, A. Roth, J. A. Collins, and R. R. Breaker. 2004. Control of gene expression by a natural metabolite-responsive ribozyme. Nature 428281-286. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.