Abstract

Absolute lung volumes such as functional residual capacity, residual volume (RV), and total lung capacity (TLC) are used to characterize emphysema in patients, whereas in animal models of emphysema, the mechanical parameters are invariably obtained as a function of transrespiratory pressure (Prs). The aim of the present study was to establish a link between the mechanical parameters including tissue elastance (H) and airway resistance (Raw), and thoracic gas volume (TGV) in addition to Prs in a mouse model of emphysema. Using low-frequency forced oscillations during slow deep inflation, we tracked H and Raw as functions of TGV and Prs in normal mice and mice treated with porcine pancreatic elastase. The presence of emphysema was confirmed by morphometric analysis of histological slices. The treatment resulted in an increase in TGV by 51 and 44% and a decrease in H by 57 and 27%, respectively, at 0 and 20 cmH2O of Prs. The Raw did not differ between the groups at any value of Prs, but it was significantly higher in the treated mice at comparable TGV values. In further groups of mice, tracheal sounds were recorded during inflations from RV to TLC. All lung volumes but RV were significantly elevated in the treated mice, whereas the numbers and size distributions of inspiratory crackles were not different, suggesting that the airways were not affected by the elastase treatment. These findings emphasize the importance of absolute lung volumes and indicate that tissue destruction was not associated with airway dysfunction in this mouse model of emphysema.

Keywords: elastance, airway resistance, pressure-volume curve, airway reopening, crackle sound

emphysema is clinically characterized by loss of elastic recoil and significant hyperexpansion of the lungs due to a permanent destruction of the parenchymal tissue structure (35). Although a variety of mechanisms including protease-antiprotease imbalance (27), inflammation (23), abnormal extracellular matrix remodeling (46), and mechanical forces (44) have been proposed to be involved in its pathogenesis, the progressive nature of emphysema is still poorly understood (3).

The assessment and evaluation of emphysema raise several questions related to both the functional and structural aspects of the disease. Specifically, the physiological characterization of emphysema requires the measurement of pulmonary or respiratory mechanics (18, 39). In clinical studies, absolute lung volumes such as residual volume (RV), functional residual capacity, or total lung capacity (TLC), as well as their ratios are used to characterize the emphysematous changes (14, 47, 49). To gain insight into the pathogenesis and progression of the human disease, various small animal models of emphysema have been developed (11, 25, 32, 41, 45). However, in animal experiments, the mechanical parameters are most often represented in terms of their dependence on transpulmonary (Pl) or transrespiratory pressure (Prs) or positive end-expiratory pressure (PEEP) (25). This is particularly true for the mouse, the most preferred experimental animal because of the availability of genetic manipulations (12), in which the assessment of changes in absolute lung volume is technically demanding due to the small lung size and is therefore rarely reported. Thus it remains unclear how the physiological findings including the mechanical properties of the lung expressed in terms of Pl or Prs in the various mouse models of emphysema are related to the clinically observable pathophysiological changes in lung volumes and the associated alterations in respiratory resistance and elastance in patients.

The purpose of this study was to establish a link between the mechanical properties of the respiratory system and absolute lung volumes in mice treated with porcine pancreatic elastase (PPE). To this end, we used a previously developed technique to track the elastic and resistive parameters of the respiratory system during slow inspiratory-expiratory maneuvers (19) while recording the changes in lung volume. Our findings suggest that presentation of parameters in terms of absolute lung volumes differ substantially from that in terms of transrespiratory pressures.

METHODS

Animal preparation.

Female CBA/Ca mice were anesthetized with an intraperitoneal injection of pentobarbital sodium (75 mg/kg) and intubated with a 20-mm-long, 0.8-mm inner diameter polyethylene cannula under the guidance of a cold light source (model FLQ85E, Helmuth Hund, Wetzlar, Germany), according to the technique described in detail by others (8, 17). The elastase-treated animals received PPE (Sigma-Aldrich Hungary, Budapest, Hungary) in 50 μl of saline in one of two doses: 0.3 IU (n = 15) and 0.6 IU (n = 4) via intratracheal instillation. The control animals (n = 19) received 50 μl of saline only. Three weeks thereafter, the mice were anesthetized with an intraperitoneal injection of pentobarbital sodium (75 mg/kg), tracheotomized, and cannulated with a 0.8-mm inner diameter polyethylene tube. The animals were placed in a custom-built 160-ml body plethysmograph in the supine position and ventilated transmurally with a small-animal respirator (Harvard Apparatus, South Natick, MA) at a rate of 160 min−1, tidal volume of 0.25 ml, and a positive end-expiratory pressure of 2 cmH2O. Supplemental doses of pentobarbital sodium (15 mg/kg) were administered as needed, generally at the beginning of the measurements. The study protocol was approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committees of the University of Szeged and Boston University.

Measurement of lung volumes.

Thoracic gas volume (TGV) at end expiration at zero transrespiratory pressure (TGV0) was measured with the plethysmographic technique (13), modified recently for the measurement of thoracic gas volume in anesthetized mice that have weak or no respiratory effort (28). Briefly, 2–3 s after the respirator was stopped, the tracheal cannula was occluded and the intercostal muscles were stimulated via a pair of electrodes arranged diagonally between the upper and lower chest regions, with single impulses of 8–12 V in amplitude and 0.1 ms in duration (model S44, Grass Instruments, Quincy, MA), repeated five to six times in a 10-s recording interval. Figure 1 shows the measurement setup. Plethysmograph pressure (Pbox) and tracheal pressure (Ptr) were measured with miniature pressure transducers (model 8507C-2, Endevco, San Juan Capistrano, CA). TGV0 was estimated from the Pbox vs. Ptr relationship on the basis of Boyle's principle, as described previously in detail (28). Following the measurement of TGV0, in 14 control animals (group C1) and 14 elastase-treated mice (group E1) the tracheal cannula was connected to a loudspeaker via a 100-cm, 0.117-cm inner diameter polyethylene tube (a wave tube; see below). After a 5-s pause at end expiration, Pbox was lowered approximately linearly by connecting the plethysmograph to a vacuum line until −20 cmH2O was reached, and then Pbox was allowed to return quasi-exponentially to 0 cmH2O by opening the box to atmosphere through a resistor. The inflation and deflation phases lasted for ∼20 and ∼25 s, respectively. Inlet and outlet lateral pressures of the wave tube (P1 and P2, respectively) were measured by another pair of Endevco transducers. Inflation volume V(t) was obtained by integration of flow (V′) determined as V′ = P2/Rwt, where Rwt is the direct current resistance of the wave tube. TGV as a function of time was obtained as TGV(t) = TGV0 + V(t). Transrespiratory pressure (Prs) was calculated as Ptr − Pbox.

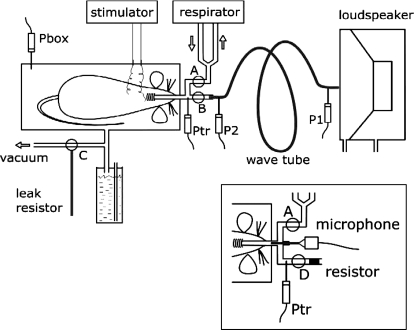

Fig. 1.

Schematic arrangement for the measurement of thoracic gas volume (TGV) and oscillatory mechanics. During the measurement of TGV with respiratory muscle stimulation, stoppers A, B, and C were closed, and plethysmograph box pressure (Pbox) and tracheal pressure (Ptr) were recorded. The tracheal cannula was then connected via stopper B and a wave tube to a loudspeaker box open to atmosphere, and inflation was started by opening stopper C to a vacuum source; a water column limited Pbox at −20 or −35 cmH2O. During the subsequent deflation, the box was connected to atmosphere via stopper C through a leak resistor. During inflation-deflation, the loudspeaker delivered an oscillatory signal via the wave tube whose inlet (P1) and outlet lateral pressures (P2) were recorded. Inset: modified arrangement for the recording of tracheal sounds during reinflation from residual volume (Pbox = 20 cmH2O) to total lung capacity (Pbox = −35 cmH2O) in the group C2 and group E2 mice. With stopper A closed and stopper B open, tracheal flow was measured as the pressure drop (Ptr) across a capillary bundle resistor while the microphone recorded the sound.

In five control mice (group C2) and five mice treated with 0.3 IU elastase (group E2), the measurement of TGV0 was followed by deflation to RV, accomplished by elevating Pbox to 20 cmH2O; subsequently, Pbox was lowered to −35 cmH2O through the vacuum line in ∼30 s to obtain an estimate of TLC. The box was then opened to atmosphere via a resistor to allow for a passive deflation. During this deflation-inflation-deflation maneuver, V′ was measured with a capillary bundle (resistance = 180 cmH2O·s·l−1) and the Ptr transducer (Fig. 1, inset). Expiratory reserve volume (ERV) was determined by integration, and RV was obtained as TGV0 − ERV.

Measurement of respiratory impedance.

The tracking estimation of the impedance of the total respiratory system (Zrs) during slow inflation-deflation maneuvers was performed in the group C1 and group E1 mice. The measurement of Zrs was similar to that described previously in detail (19), with the modification that a negative body surface pressure was applied (6) instead of the positive pressure inflation. Briefly, Zrs was measured as the load impedance of the wave tube by using a pseudorandom signal between 4 and 38 Hz. Mean Zrs was computed for the first 5 s of oscillation before the inflation started (to estimate Zrs at TGV0) and for every successive 0.5-s interval during the maneuver. Each Zrs spectrum was fitted by a model (20) containing a Newtonian resistance ascribed to the airways (Raw), an inertance (I), and a constant-phase tissue unit characterized by the coefficients of damping (G) and elastance (H). Hysteresivity (η), the ratio of the dissipated and elastically stored energies in the tissue (16), was calculated as η = G/H. The resistance and the inertance of the tubing including the tracheal cannula were subtracted from Raw and I, respectively; since the inertance of this tubing was the major component of I, the remaining values are considered physiologically unimportant and are not reported.

The slow inflation-deflation maneuvers, together with the preceding measurements of TGV0, were repeated three times in each animal to establish a standard volume history and to ascertain that the Prs-V loops and the Zrs spectra as a function of lung volume were reproducible. The Zrs parameters did not exhibit different volume dependences during inflation and deflation; hence, for clarity, the tracking results are presented only for inflation.

Crackle sound recordings.

For the measurements in the C2 and E2 groups, the setup was modified so that a microphone ending in a 15-mm-long, 0.7-mm outer diameter metal tube was connected to the tracheal tube adaptor of the plethysmograph (Fig. 1, inset). Tracheal sound was recorded at a sampling rate of 44 kHz and a 16-bit resolution and preprocessed with a GoldWave sound editor (version 5.12, GoldWave, St. John's NFLD, Canada). High-pass filtering at 2 kHz was used to eliminate the cardiac noise. Subsequently, a short 0.5-ms time window was set up and moved along the sound recording. An individual crackle event was identified if the sound energy in a window increased above a threshold that was chosen to eliminate most of the background noise. The crackle energy was represented by its cumulative distribution defined as the sum of energy up to a given inflation pressure normalized by the total energy, whereas the crackle amplitudes were characterized with their probability density distribution. The details of sound recording and processing are described in Ref. 37.

Lung morphometry.

At the end of the measurements, the mice were killed with an overdose of pentobarbital sodium, and the heart and the lungs were removed en bloc. The collapsed lungs were then slowly inflated via the tracheal cannula by injecting 1 ml of low melt agarose warmed to 45°C at a concentration of 4%. Successful fixation was accomplished in four elastase-treated and five control mice. Epifluorescence microscopy was employed to study alveolar morphometry in two to three slices in each lung. Following thresholding, the alveolar or terminal airspace cross-sectional areas (A) were measured using image-processing software (INVIVO, Pictron, Budapest, Hungary), and an equivalent alveolar diameter (D) was calculated as D = (4A/π)1/2. From the values of A, an area-weighted mean equivalent diameter (D2) was also calculated. The number of D values obtained in individual animals was not sufficient to compute a complete diameter distribution. Since, by visual inspection, the characteristics of the alveolar structure were similar in the treated animals, we pooled the diameters and constructed single-diameter distribution for both the control and treated mice. The equivalent diameter is useful in that it is not sensitive to shape and it can better characterize the alveolar structure than other morphological indexes in the presence of structural heterogeneity (34).

Statistical analysis.

The differences in mechanical parameters between the control and elastase-treated animals were compared using repeated-measures ANOVA tests. The variability of alveolar diameters was compared using F test.

RESULTS

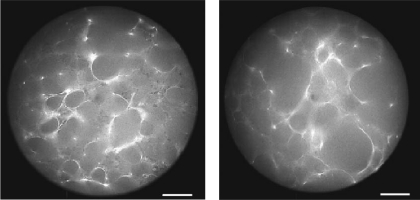

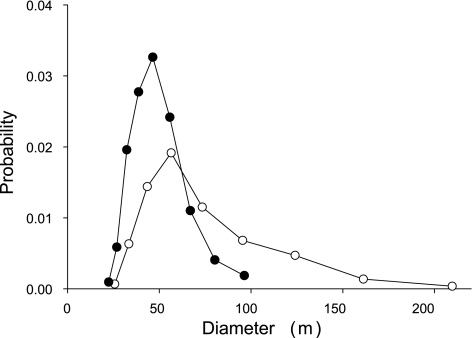

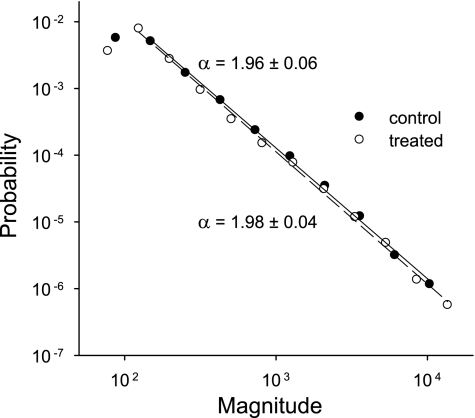

Morphometric evaluation of the lung slices (Fig. 2) revealed a significant enlargement of the alveolar airspace sizes in the elastase-treated animals: the equivalent diameter D increased from 46.5 ± 13.8 μm in the control mice to 70.3 ± 34.2 μm in the treated mice (P < 0.001). Additionally, the variance of the alveolar diameters was also statistically significantly higher in the treated mice (P < 0.001). There was a significant increase in the mean area-weighted diameter D2 from 55 to 107 μm (P < 0.01). In both groups, the distribution of the diameters was significantly different from a normal distribution (P < 0.001). The distribution of diameters was skewed in both groups; however, in the treated mice, the distribution exhibited a significantly longer tail reaching values above 200 μm (Fig. 3).

Fig. 2.

Epifluorescence microscopy pictures of agarose-fixed lung slices. Left: control lung. Right: elastase-treated lung. Bar = 50 μm.

Fig. 3.

Probability distribution of equivalent alveolar or terminal airspace diameters in subpopulations of control (•) and elastase-treated mice (○).

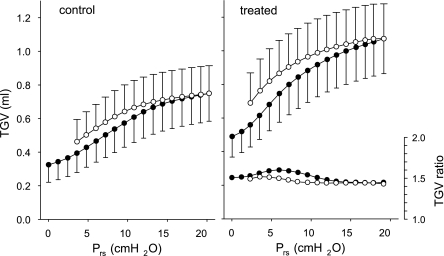

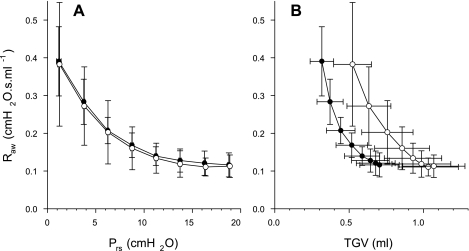

Elastase treatment resulted in marked and statistically highly significant changes in lung volumes: compared with control, TGV0 and TGV at Prs of 20 cmH2O (TGV20) increased by 52 and 45%, respectively (Table 1). There was no difference between the group E1 mice treated with the 0.3 and 0.6 IU doses of elastase in any of the morphometric indexes or mechanical parameters except η at TGV20 (0.170 ± 0.007 vs. 0.157 ± 0.004; P < 0.01). Therefore, both the mechanical and morphometric parameters from the two groups were pooled. The average TGV vs. Prs curves also reflected the changes due to the elastase treatment (Fig. 4), with the mean values of TGV significantly different (P < 0.001) between the groups at all Prs levels. The ratios of TGV between the groups at the same Prs were fairly constant (between 1.44 and 1.60 for inspiration and between 1.43 and 1.52 for expiration), suggesting a nearly proportional increase of TGV at all Prs, i.e., an unchanged shape of the PV loops. Inspiratory volume (TGV20 − TGV0) increased by 37% in the treated animals, which was also accompanied by a 27% decrease in chord elastance between 0 and 20 cmH2O.

Table 1.

Thoracic gas volumes and oscillatory mechanical parameters

| Group | Weight, g | TGV0, ml | TGV20, ml | H0, cmH2O/ml | H20, cmH2O/ml | η0 | η20 | Raw0, cmH2O·s·ml−1 | Raw20, cmH2O·s·ml−1 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| C1 | 29±2 | 0.31±0.06 | 0.76±0.11 | 52±10 | 129±9 | 0.24±0.02 | 0.15±0.01 | 0.46±0.14 | 0.12±0.02 |

| E1 | 29±3 | 0.47±0.10 | 1.10±0.18 | 22±7 | 94±12 | 0.38±0.07 | 0.17±0.01 | 0.45±0.18 | 0.11±0.02 |

| P value | NS | <0.001 | <0.001 | <0.001 | <0.001 | <0.001 | <0.001 | NS | NS |

Values are means ± SD. Thoracic gas volumes (TGV) and oscillatory mechanical parameters are at transrespiratory pressures of 0 cmH2O (suffix 0) and 20 cmH2O (suffix 20) in the control (group C1; n =14) and the elastase-treated (group E1; n =14) mice. H, elastance coefficient; η, hysteresivity; Raw, airway resistance; NS, statistically not significant.

Fig. 4.

Inflation (•) and deflation (○) curves of thoracic gas volume (TGV) vs. transrespiratory pressure (Prs) averaged for the control mice (group C1) and the elastase-treated animals (group E1). Bars indicate standard deviation. The ratio of TGV values of the elastase-treated mice to those in the controls, as a function of Prs, is also plotted (right and bottom).

The mechanical parameters obtained from the small-amplitude forced oscillatory measurements of the elastase-treated mice exhibited similarly marked changes: compared with control, the decreases in H were 57 and 27%, respectively, at Prs values of 0 and 20 cmH2O (Table 1). The values of η were also altered by the elastase treatment, with increases more marked at 0 cmH2O (55%) than at 20 cmH2O (12%). By contrast, small and statistically insignificant decreases were observed in Raw at both 0 cmH2O (−2%) and 20 cmH2O (−10%). Since in the inflation-deflation maneuver the pressure protocol was standardized, the group mean values of these parameters were calculated as functions of both Prs and TGV.

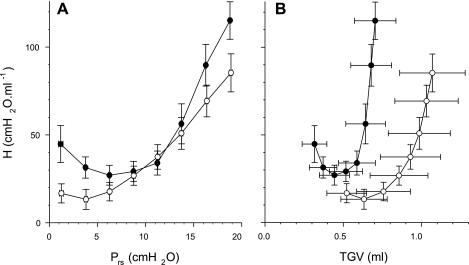

Figure 5, A and B, display the dependences of H on Prs and TGV, respectively. The differences in H between group E1 and group C1 animals in the low and high Prs range were in accord with the mean values of H at 0 and 20 cmH2O (see Table 1), whereas this difference disappeared in the pressure range between 9 and 13 cmH2O (Fig. 5A). When plotted as a function of TGV (Fig. 5B), the values of H corresponding to the control and treated animals were completely separated. The mean H at comparable TGV was significantly lower in the treated animals, which suggests that the dynamic elastance in the treated mice reached values similar to those of the control animals at about twice as high absolute lung volumes.

Fig. 5.

A: elastance coefficient (H) vs. transrespiratory pressure (Prs) during slow inflation from Prs of 0–20 cmH2O. The values in each animal were averaged for successive 2.5-cmH2O ranges of Prs. The mean values of H for the animals in the control (group C1) mice (•) and the elastase-treated (group E1) mice (○) are statistically significantly different (P < 0.05) at Prs of <8 cmH2O and Prs of >14 cmH2O. Bars denote standard deviation. B: H vs. thoracic gas volume (TGV). The values of H are statistically significantly different between the two groups at all ranges of Prs (P < 0.05).

The mean Raw data did not differ between the groups at any value of Prs (Fig. 6A). However, the Raw curves as a function of TGV were remarkably different from those expressed in terms of Prs (Fig. 6B). Elastase treatment resulted in a rightward shift of the mean Raw vs. TGV relationship and, consequently, in statistically significantly higher Raw values at comparable lung volumes (Fig. 6B).

Fig. 6.

A: airway resistance (Raw) vs. transrespiratory pressure (Prs) during slow inflation from Prs of 0–20 cmH2O. The values in each animal were averaged for successive 2.5-cmH2O ranges of Prs. No statistically significant difference was found between the mean values of Raw for the control (group C1) mice (•) and the elastase-treated (group E1) mice (○) in any range of Prs. Bars denote standard deviation. B: raw vs. thoracic gas volume (TGV). The values of Raw are statistically significantly different between the two groups for all TGV (P < 0.05).

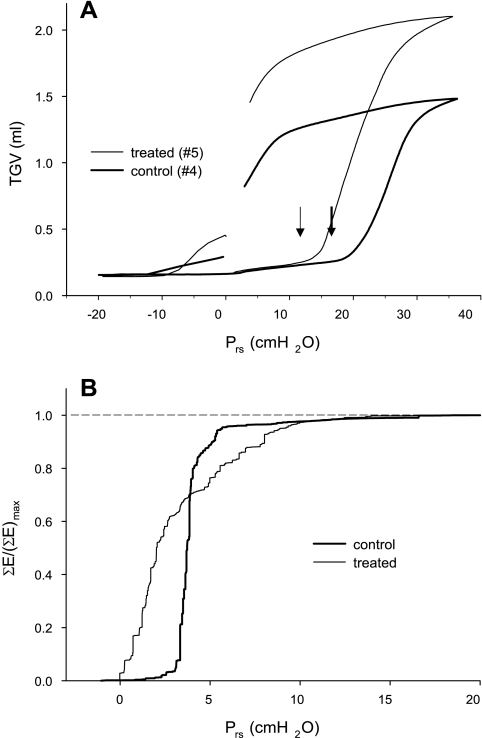

The vital capacity (VC) maneuvers performed in the group C2 and group E2 animals also revealed marked differences in all lung volumes but RV; a typical example is shown in Fig. 7A. The increase in TGV0 in the treated mice (51%) was the same as that in the group E1 mice, and similar elevations (41 and 52%) were observed in TLC and VC, respectively (Table 2). Interestingly, the pressure at the bottom knee of the TGV-Prs curve decreased on average by 5.5 cmH2O in the treated animals (P < 0.001). The number of crackles detected during inflation from RV to TLC was ∼150 and did not differ between the group C2 and group E2 mice (Table 2). The cumulative distributions of crackle energy in the C2 and E2 groups are compared in Fig. 7B as a function of Prs. In group C2, the cumulative energy rises steeply from 0 to above 95% within a narrow range of Prs values between 2.5 and ∼5 cmH2O. In contrast, the cumulative energy in the E2 group rises almost immediately at the start of inflation but reaches 95% only by a Prs of ∼9 cmH2O. Despite the grossly different rates of crackle energy release during inflation, the probability distribution (Π) of crackle amplitudes was very similar in the two groups (Fig. 8). Since both distributions followed a linear decrease on a log-log graph, Π can be described by a power law as Π ∼ s−α, where s is the crackle amplitude and α is the exponent of the distribution. Furthermore, α had identical values, close to 2 with a small standard deviation, in the two groups of mice (Fig. 8).

Fig. 7.

A: thoracic gas volume (TGV) vs. transrespiratory pressure (Prs) curves recorded during vital capacity maneuvers in a control (group C2) and an elastase-treated (group E2) mouse. Arrows indicate the bottom knees of the inflation curve. B: cumulated crackle sound energy ΣE normalized by its maximum value (ΣE)max in the control and the treated mice. Pooled data are in both groups.

Table 2.

End-expiratory thoracic gas volume, residual volume, vital capacity, and total lung capacity

| Group | Weight, g | TGV0, ml | RV, ml | VC, ml | TLC, ml | Pknee, cmH2O | Ncr/infl |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| C2 | 33±2 | 0.32±0.09 | 0.20±0.10 | 1.28±0.26 | 1.48±0.20 | 21.5±1.0 | 148±111 |

| E2 | 33±2 | 0.49±0.08 | 0.15±0.03 | 1.95±0.18 | 2.10±0.19 | 15.9±1.3 | 166±72 |

| P | NS | <0.02 | NS | <0.001 | <0.001 | <0.001 | NS |

Values are means ± SD. End-expiratory thoracic gas volume (TGV0), residual volume (RV), vital capacity (VC), total lung capacity (TLC) corresponding to the transrespiratory pressure of 35 cmH2O, pressure at the bottom knee of the thoracic gas volume vs. transrespiratory pressure curve (Pknee), and the number of crackles during an inflation maneuver (Ncr/infl) in the control (group C2; n =5) and the elastase-treated mice (group E2; n =5).

Fig. 8.

Log-log plots of the probability distributions of crackle amplitude (in arbitrary units) recorded during inflations from residual volume to total lung capacity in the control (group C2) and the elastase-treated (group E2) mice. Pooled data are from three to five inflation maneuvers in each mouse. The regression lines cover the data range included in the regression.

DISCUSSION

The primary purpose of this study was to characterize the mechanical properties of the respiratory system in a mouse model of emphysema in terms of Prs and TGV. To achieve this goal, we used a standard elastase treatment protocol and confirmed the presence of emphysema in the treated mice using morphometric analysis of the alveolar structure at a fixed time point, 3 wk following treatment. We also employed a plethysmographic method to determine TGV in mice (28) in combination with a forced oscillation technique that is able to separately estimate the airway and tissue mechanical parameters during slow lung inflation and deflation (19). The main findings of the study are that 1) both the mean and variance of alveolar diameters significantly increased in the treated mice, which resulted in increases in TGV similar to those seen in FRC and TLC in patients with emphysema; 2) dynamic elastance of the lung as a function of Prs was significantly lower in the treated mice except in a narrow range of Prs corresponding to lung volumes approximately halfway between FRC and TLC; 3) when expressed in terms of absolute lung volume, dynamic elastance was markedly lower in the treated mice; and 4) airway resistance (Raw) was significantly higher in the treated group at comparable lung volumes, but the differences disappeared when Raw was plotted as a function of Prs. Furthermore, measurements made in two additional groups of mice revealed that 5) the elastase treatment did not lead to any increase in RV, and the statistics of crackle properties that are related to airway reopening do not substantiate any change in bronchial patency.

Methodological issues.

Several methodological issues warrant discussion. First, the elastase treatment produces a quick injury-like pathophysiology including the deterioration of lung function and airspace enlargement, whereas human emphysema is usually associated with cigarette smoking with its full development often taking more than 5 years. In this respect, the elastase-induced emphysema does not model the human disease. On the other hand, rodents respond to cigarette smoke in a highly variable manner, and the pathophysiologal changes at best mimic mild COPD (48). For the specific purpose of comparing lung physiology as expressed in terms of absolute lung volume or transrespiratory pressure, the widely used elastase treatment targeting the tissue compartment is appropriate. Second, it has been reported that there exists a second “knee” in the pressure-volume curve of mice beyond 20 cmH2O (42). To avoid the rapid changes in mechanical properties of such a second knee, the tracking maneuvers were limited to a maximum inflation pressure of 20 cmH2O. We note, however, that the inflation curves initiated from RV (groups C2 and E2) followed a single sigmoidal and were reproducible, and hence we defined TLC as the value of TGV reached at Prs = 35 cmH2O, while acknowledging the problems of the definition of TLC in mice (42). Another issue is related to the measurement of the quasi-static and dynamic properties of the total respiratory system. The contribution of the chest wall to the total respiratory elastance is small in mice, which implies a negligible impact on the pressure-volume curve (30) and a <10% share in the dynamic elastance H (25, 40). Therefore, any change in H following elastase treatment must be proportional to alterations in lung tissue properties. We should also note that, although the parameter Raw estimated from the model fitting to the Zrs data represents not only airway resistance but all frequency-independent (Newtonian) viscous losses in the respiratory system, the contribution of the chest wall to the Newtonian resistance was shown to be negligible at any lung volume in mice (40).

Parenchymal structural changes.

It has recently been shown that the trapped gas volume in excised lungs from a variety of animal models of emphysema correlated with morphometric evaluation of the alveolar structure (29). In the present study, the larger absolute gas volumes in the treated animals were also associated with a significant increase in the equivalent diameters (D) of the airspaces. It is interesting to note that, in response to elastase treatment, the mean D increased by 51%, which is close to the 45% increase in TGV20. Furthermore, the equivalent diameters were not normally distributed (Fig. 3), and the treatment resulted in a significant stretch of the tail of the diameter distribution from ∼100 to 200 μm. As a consequence, the standard deviation of the equivalent diameters nearly tripled, whereas the mean area-weighted diameter D2 doubled following treatment. Since both the variance and D2 are sensitive to heterogeneities (34), these results imply that the elastase treatment significantly increased the structural heterogeneity of the parenchyma. The increased heterogeneity is also supported by the fact that the coefficient of variation of diameters increased from 30% in control to 49% in the treated mice.

The increase in heterogeneity is consistent with the possibility that the enzymatically weakened alveolar walls rupture under the influence of mechanical forces (44). The presence of elastase in the interstitium not only leads to digestion of the elastin of the connective tissue, but it also triggers complex cellular repair processes (46). Such repair is likely abnormal (46), and the corresponding extracellular assembly of collagen results in mechanically weak collagen fibers in the alveolar walls. At points of stress concentration, the weak collagen and the alveolar wall break. Following rupture, the stress is redistributed in the neighborhood, and, consequently, the nearby intact regions start to experience new stress concentration (39). This ongoing process necessarily leads to an increase in structural heterogeneity as well as a progressive decrease in lung recoil. The latter in turn results in a larger TGV at the same Prs in the treated mice (Fig. 4).

Dynamic tissue properties.

Although H decreased significantly in the treated mice both at low and high Prs (Table 1), the initial decrease in H with increasing Prs and the reversal toward higher Prs values remained a characteristic feature of the H vs. Prs relationship following the elastase treatment (Fig. 5A). However, the initial decrease reverses at a lower Prs in the elastase-treated mice, and this is in accordance with the results of a study on mice spontaneously developing emphysema (tight skin mice) and their controls, in which lung elastance was measured as a function of PEEP (24). The elevation in H at high Prs is likely due to the stretching of the respiratory tissues and recruiting collagen in the lung parenchyma (19, 40), whereas the mechanisms behind the initial decrease in H are less clear: they may include alveolar recruitment, reorganization of the tissue matrix and the surfactant layer (19, 25, 40), or chest wall mechanics (22). Whatever the mechanism, the biphasic pattern of the H vs. Prs is also seen as a function of TGV and is not altered by the elastase treatment (Fig. 5B); nevertheless, when H is plotted against TGV, the separation between the two groups becomes more apparent.

Tissue hysteresivity was also markedly affected by the elastase treatment. The 55% increase in η at end-expiration is in accord with several previous studies (7, 25, 31). Brewer et al. (7) argued that the increased η is a result of remodeling of the alveolar walls. At higher lung volume, the difference between the values of η of the two groups, both exhibiting a significant fall from the values obtained at end-expiration, was drastically reduced to 12%. The decrease in η with increasing lung volume has been attributed to the increasing contribution of collagen to tissue resistance (15, 40). Additionally, Ito et al. (26) reported that, following elastase treatment of mice, respiratory elastance decreased despite a nearly 50% increase in the total collagen content of the lung, implying an abnormality in collagen function. Together with the increase in tissue heterogeneity discussed above, the abnormal collagen function might also have contributed to the overall increase in η in the treated mice (Table 1).

Airway resistance and structure.

Several studies using animal models of emphysema have pointed out that the tissue destruction manifested in elevations in TGV and decreases in elastance are not associated with increased airway or pulmonary resistance (2, 4, 5, 9, 33), and some observations on human emphysema also indicate that airspace enlargement and airflow limitation do not necessarily combine (10, 38, 47). In this context, the changes following elastase treatment observed in the present study may characterize an initial or mild degree of emphysema where the loss of alveolar attachments, which must have accompanied the marked increase in both alveolar size and lung volumes, is compensated by new elastic equilibria within the lung parenchyma itself as well as between the lung and chest wall so that the patency of the airways is retained. Therefore, we paid particular attention to the possible alterations in airway function and established that the average Raw vs. Prs relationships of the control and treated groups were remarkably similar (Fig. 6A). Another indicator of the intact airway function was the lack of any increase in airway collapsibility during forced expiration to RV, the only lung volume that, quite unexpectedly, did not change in this emphysema model. Furthermore, the size distribution of crackle amplitudes was identical in the C2 and E2 groups (Fig. 8). Since the power law nature of the crackle amplitude distribution is dominated by the attenuation factors at bifurcations (and not by the opening pressures), which in turn are determined by airway cross-sectional areas (1), we conclude that once the airways opened, the diameters along various pathways must have been similar in the two groups as a function of Prs. Finally, there was no difference in airway closure during the RV maneuver between the control and treated animals according to the analysis of reinflation crackles, which has been shown to be a sensitive indicator of airway collapse at varying levels of transpulmonary pressure and bronchoconstrictor dose (37). On the other hand, it should be pointed out that, at the same absolute lung volume, the Raw of the emphysematous mice were higher, a fact also established in clinical cases of emphysema and COPD (49). This is a consequence of the fact that, at the same lung volume, transpulmonary pressure in the treated mice is much less, and this, due to the loss of elastic tethering, leads to a higher Raw (Fig. 6A). These findings, together with the different pressure- and volume-dependent behavior of dynamic elastance highlight the importance of measuring TGV and comparing the mechanical parameters at similar absolute lung volumes.

Quasi-static pressure-volume curves.

The structural changes due to the elastase treatment are reflected in the increases in lung volumes at all Prs values (Fig. 4). The elevations in the end-expiratory and end-inspiratory volumes in the treated mice amounted to ∼50 and ∼40%, respectively, reflecting an upward stretching in the TGV vs. Prs diagrams with a negligible change in the shape of the TGV vs. Prs loops (Fig. 4). A remarkable finding is the increase in the expiratory reserve volume in the group E2 mice, which corresponds to little or no change in RV. Since RV is most sensitive to small airway collapse, these results imply that the small airways, whose closure determines RV, were not influenced by elastase treatment. Interestingly, the lower knee of the pressure-volume curve (Fig. 7A and Table 2) moved to a lower pressure, and the cumulative crackle energy started increasing at a much lower Prs in the treated mice (Fig. 7B). Both of these findings suggest that a significant fraction of the airways had a lower critical opening pressure in the treated animals. How is it then possible that, whereas RV and Raw at the same Prs are the same in the control and treated mice, the lower knee and the crackle energies are different between the two groups?

The lower knee of the inflation curve is associated with massive airway opening leading to alveolar recruitment (43), although the crackles that were detectable in our experiments may come from larger airways than those that determine RV (21). Thus, although the site of airway closure and the trapped air behind the small airways that determine RV are similar in the two groups, the relative locations of the knee in Fig. 7A imply that some of these airways are easier to open up in the emphysematous group. In contrast, since a weakened parenchymal tethering, which characterizes the E2 group, reduces the probability of reopening airways (36), one might expect that the opening pressures would actually be higher in the E2 group. In fact, by examining the cumulative distributions in Fig. 7B, both of these statements are true. Indeed, on the one hand, the difference in cumulative crackle energy does imply that some airways must be more difficult to open in the E2 group since 95% of the total energy is reached only at Prs of 9 cmH2O compared with Prs of ∼5 cmH2O in the C2 group. On the other hand, there are crackles that are triggered at a much lower Prs in the E2 than in the C2 group, indicating that some airways open very easily in the former. Although the reduced tethering in the E2 group explains why some airways are more difficult to open in the E2 group, we are unsure about the exact mechanism responsible for the reduction in airway opening pressures following treatment. Assuming that surface tension is not altered by the elastase treatment, we can speculate as follows. Computer simulations mimicking the breakdown of lung parenchyma have shown that, when the breakdown is governed by mechanical forces, a significant heterogeneity develops in the network (44). This leads to a wide distribution of mechanical forces around the damaged area, including elastic elements that carry significantly smaller as well as larger forces than before the breakdown (24). The higher forces would then generate locally an increased tethering and hence a reduced opening pressure. Nevertheless, the above uncertainties indicate that further investigations involving time course studies with a longer time period after the elastase treatment are warranted to further characterize the relevance of this murine model of emphysema to the human disease.

GRANTS

Supported by Hungarian Scientific Research Fund Grants T42971, T37810, and 67700, National Health and Medical Research Council of Australia no. 139024, National Science Foundation Grant BES-0402530, and National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute Grant HL-059215.

The costs of publication of this article were defrayed in part by the payment of page charges. The article must therefore be hereby marked “advertisement” in accordance with 18 U.S.C. Section 1734 solely to indicate this fact.

REFERENCES

- 1.Alencar AM, Hantos Z, Petak F, Tolnai J, Asztalos T, Zapperi S, Andrade JS Jr, Buldyrev SV, Stanley HE, Suki B. Scaling behavior in crackle sound during lung inflation. Phys Rev E Stat Phys Plasmas Fluids Relat Interdiscip Topics 60: 4659–4663, 1999. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Barnas GM, Delaney PA, Gheorghiu I, Mandava S, Russell RG, Kahn R, Mackenzie CF. Respiratory impedances and acinar gas transfer in a canine model for emphysema. J Appl Physiol 83: 179–188, 1997. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Barnes PJ, Stockley RA. COPD: current therapeutic interventions and future approaches. Eur Respir J 25: 1084–1106, 2005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bellofiore S, Eidelman DH, Macklem PT, Martin JG. Effects of elastase-induced emphysema on airway responsiveness to methacholine in rats. J Appl Physiol 66: 606–612, 1989. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Boyd RL, Fisher MJ, Jaeger MJ. Non-invasive lung function tests in rats with progressive papain-induced emphysema. Respir Physiol 40: 181–190, 1980. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bozanich EM, Janosi T, Collins RA, Thamrin C, Turner DJ, Hantos Z, Sly PD. Methacholine responsiveness in mice from 2 to 8 weeks of age. J Appl Physiol 103: 542–546, 2007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Brewer KK, Sakai H, Alencar AM, Majumdar A, Arold SP, Lutchen KR, Ingenito EP, Suki B. Lung and alveolar wall elastic and hysteretic behavior in rats: effects of in vivo elastase treatment. J Appl Physiol 95: 1926–1936, 2003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Brown RH, Walters DM, Greenberg RS, Mitzner W. A method of endotracheal intubation and pulmonary functional assessment for repeated studies in mice. J Appl Physiol 87: 2362–2365, 1999. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Brusselle GG, Bracke KR, Maes T, D'Hulst AI, Moerloose KB, Joos GF, Pauwels RA. Murine models of COPD. Pulm Pharmacol Ther 19: 155–165, 2006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Clark KD, Wardrobe-Wong N, Elliott JJ, Gill PT, Tait NP, Snashall PD. Patterns of lung disease in a “normal” smoking population: are emphysema and airflow obstruction found together? Chest 120: 743–747, 2001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.D'Armiento J, Dalal SS, Okada Y, Berg RA, Chada K. Collagenase expression in the lungs of transgenic mice causes pulmonary emphysema. Cell 71: 955–961, 1992. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Drazen JM, Takebayashi T, Long NC, De Sanctis GT, Shore SA. Animal models of asthma and chronic bronchitis. Clin Exp Allergy 29, Suppl 2: 37–47, 1999. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.DuBois AB, Botelho SY, Bedell GN, Marshall R, Comroe JH Jr. A rapid plethysmographic method for measuring thoracic gas volume: a comparison with a nitrogen washout method for measuring functional residual capacity in normal subjects. J Clin Invest 35: 322–326, 1956. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Dykstra BJ, Scanlon PD, Kester MM, Beck KC, Enright PL. Lung volumes in 4,774 patients with obstructive lung disease. Chest 115: 68–74, 1999. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Faffe DS, D'Alessandro ES, Xisto DG, Antunes MA, Romero PV, Negri EM, Rodrigues NR, Capelozzi VL, Zin WA, Rocco PR. Mouse strain dependence of lung tissue mechanics: role of specific extracellular matrix composition. Respir Physiol Neurobiol 152: 186–196, 2006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Fredberg JJ, Stamenovic D. On the imperfect elasticity of lung tissue. J Appl Physiol 67: 2408–2419, 1989. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Glaab T, Mitzner W, Braun A, Ernst H, Korolewitz R, Hohlfeld JM, Krug N, Hoymann HG. Repetitive measurements of pulmonary mechanics to inhaled cholinergic challenge in spontaneously breathing mice. J Appl Physiol 97: 1104–1111, 2004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Govaerts E, Demedts M, Van de Woestijne KP. Total respiratory impedance and early emphysema. Eur Respir J 6: 1181–1185, 1993. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Hantos Z, Collins RA, Turner DJ, Janosi TZ, Sly PD. Tracking of airway and tissue mechanics during TLC maneuvers in mice. J Appl Physiol 95: 1695–1705, 2003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Hantos Z, Daroczy B, Suki B, Nagy S, Fredberg JJ. Input impedance and peripheral inhomogeneity of dog lungs. J Appl Physiol 72: 168–178, 1992. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Hantos Z, Tolnai J, Asztalos T, Petak F, Adamicza A, Alencar AM, Majumdar A, Suki B. Acoustic evidence of airway opening during recruitment in excised dog lungs. J Appl Physiol 97: 592–598, 2004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Hirai T, McKeown KA, Gomes RF, Bates JH. Effects of lung volume on lung and chest wall mechanics in rats. J Appl Physiol 86: 16–21, 1999. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Hogg JC Pathophysiology of airflow limitation in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Lancet 364: 709–721, 2004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Ito S, Bartolak-Suki E, Shipley JM, Parameswaran H, Majumdar A, Suki B. Early emphysema in the tight skin and pallid mice: roles of microfibril-associated glycoproteins, collagen, and mechanical forces. Am J Respir Cell Mol Biol 34: 688–694, 2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Ito S, Ingenito EP, Arold SP, Parameswaran H, Tgavalekos NT, Lutchen KR, Suki B. Tissue heterogeneity in the mouse lung: effects of elastase treatment. J Appl Physiol 97: 204–212, 2004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Ito S, Ingenito EP, Brewer KK, Black LD, Parameswaran H, Lutchen KR, Suki B. Mechanics, nonlinearity, and failure strength of lung tissue in a mouse model of emphysema: possible role of collagen remodeling. J Appl Physiol 98: 503–511, 2005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Janoff A Elastase in tissue injury. Annu Rev Med 36: 207–216, 1985. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Jánosi TZ, Adamicza Á, Zosky GR, Asztalos T, Sly PD, Hantos Z. Plethysmographic estimation of thoracic gas volume in apneic mice. J Appl Physiol 101: 454–459, 2006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Jansson AH, Smailagic A, Andersson AM, Zackrisson C, Fehniger TE, Stevens TR, Wang X. Evaluation of excised lung gas volume measurements in animals with genetic or induced emphysema. Respir Physiol Neurobiol 150: 240–250, 2006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Lai YL, Chou H. Respiratory mechanics and maximal expiratory flow in the anesthetized mouse. J Appl Physiol 88: 939–943, 2000. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Lundblad LK, Thompson-Figueroa J, Leclair T, Sullivan MJ, Poynter ME, Irvin CG, Bates JH. Tumor necrosis factor-alpha overexpression in lung disease: a single cause behind a complex phenotype. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 171: 1363–1370, 2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Mahadeva R, Shapiro SD. Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease * 3: experimental animal models of pulmonary emphysema. Thorax 57: 908–914, 2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Martin EL, Truscott EA, Bailey TC, Leco KJ, McCaig LA, Lewis JF, Veldhuizen RA. Lung mechanics in the TIMP3 null mouse and its response to mechanical ventilation. Exp Lung Res 33: 99–113, 2007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Parameswaran H, Majumdar A, Ito S, Alencar AM, Suki B. Quantitative characterization of airspace enlargement in emphysema. J Appl Physiol 100: 186–193, 2006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Pauwels RA, Buist AS, Calverley PM, Jenkins CR, Hurd SS. Global strategy for the diagnosis, management, and prevention of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. NHLBI/WHO Global Initiative for Chronic Obstructive Lung Disease (GOLD) Workshop summary. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 163: 1256–1276, 2001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Perun ML, Gaver DP, 3rd. Interaction between airway lining fluid forces and parenchymal tethering during pulmonary airway reopening. J Appl Physiol 79: 1717–1728, 1995. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Petak F, Habre W, Babik B, Tolnai J, Hantos Z. Crackle-sound recording to monitor airway closure and recruitment in ventilated pigs. Eur Respir J 27: 808–816, 2006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Petty TL, Silvers GW, Stanford RE. Mild emphysema is associated with reduced elastic recoil and increased lung size but not with air-flow limitation. Am Rev Respir Dis 136: 867–871, 1987. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Rabe KF, Hurd S, Anzueto A, Barnes PJ, Buist SA, Calverley P, Fukuchi Y, Jenkins C, Rodriguez-Roisin R, van Weel C, Zielinski J. Global strategy for the diagnosis, management, and prevention of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease: GOLD executive summary. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 176: 532–555, 2007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Sly PD, Collins RA, Thamrin C, Turner DJ, Hantos Z. Volume dependence of airway and tissue impedances in mice. J Appl Physiol 94: 1460–1466, 2003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Snider GL, Lucey EC, Stone PJ. Animal models of emphysema. Am Rev Respir Dis 133: 149–169, 1986. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Soutiere SE, Mitzner W. On defining total lung capacity in the mouse. J Appl Physiol 96: 1658–1664, 2004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Suki B, Andrade JS Jr, Coughlin MF, Stamenovic D, Stanley HE, Sujeer M, Zapperi S. Mathematical modeling of the first inflation of degassed lungs. Ann Biomed Eng 26: 608–617, 1998. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Suki B, Lutchen KR, Ingenito EP. On the progressive nature of emphysema: roles of proteases, inflammation, and mechanical forces. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 168: 516–521, 2003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Tuder RM, McGrath S, Neptune E. The pathobiological mechanisms of emphysema models: what do they have in common? Pulm Pharmacol Ther 16: 67–78, 2003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Vlahovic G, Russell ML, Mercer RR, Crapo JD. Cellular and connective tissue changes in alveolar septal walls in emphysema. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 160: 2086–2092, 1999. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Vulterini S, Bianco MR, Pellicciotti L, Sidoti AM. Lung mechanics in subjects showing increased residual volume without bronchial obstruction. Thorax 35: 461–466, 1980. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Wright JL, Cosio M, Churg A. Animal models of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Am J Physiol Lung Cell Mol Physiol 295: L1–L15, 2008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Zamel N, Hogg J, Gelb A. Mechanisms of maximal expiratory flow limitation in clinically unsuspected emphysema and obstruction of the peripheral airways. Am Rev Respir Dis 113: 337–345, 1976. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]