Abstract

In the budding yeast Saccharomyces cerevisiae, the Hsp104-mediated disaggregation of protein aggregates is essential for thermotolerance and to facilitate the maintenance of prions. In humans, protein aggregation is associated with neuronal death and dysfunction in many neurodegenerative diseases. Mechanisms of aggregation surveillance that regulate protein disaggregation are likely to play a major role in cell survival after acute stress. However, such mechanisms have not been studied. In a screen using the yeast gene deletion library for mutants unable to survive an aggregation-inducing heat stress, we find that SSD1 is required for Hsp104-mediated protein disaggregation. SSD1 is a polymorphic gene that plays a role in cellular integrity, longevity, and pathogenicity in yeast. Allelic variants of SSD1 regulate the level of thermotolerance and cell wall remodeling. We have shown that Ssd1 influences the ability of Hsp104 to hexamerize, to interact with the cochaperone Sti1, and to bind protein aggregates. These results provide a paradigm for linking Ssd1-mediated cellular integrity and Hsp104-mediated disaggregation to ensure the survival of cells with fewer aggregates.

Protein misfolding and aggregation are frequently encountered by all cells due to extrinsic factors such as heat, oxidative stress, and other stresses, or due to intrinsic factors such as aging, mutation, and the reduced availability of molecular chaperones. In humans, protein misfolding and aggregation strongly influence the onset of neurodegenerative diseases like Alzheimer's disease, Parkinson's disease, Huntington's disease, and amyotrophic lateral sclerosis (14). Since molecular chaperones prevent or reverse aggregation, studying cellular responses to stress will illuminate the molecular mechanisms in neurodegenerative disease. Mechanisms regulating protein aggregation can be easily studied in simple model organisms like the budding yeast Saccharomyces cerevisiae, where protein aggregates have interesting biological consequences such as the epigenetic inheritance of prions and the acquisition of thermotolerance.

Cellular responses to protein misfolding triggered by environmental stress like heat have been studied primarily by examining thermoresistance or thermotolerance. Thermoresistance (or innate thermotolerance) is the cell's natural ability to survive or thrive at elevated temperatures. In yeast and other organisms, it has been demonstrated that thermoresistance requires the reprogramming of most cellular pathways to the new condition (23). On the other hand, thermotolerance (or acquired thermotolerance) is a phenomenon wherein a brief pretreatment of cells with a mild heat shock potentiates cells to survive an acute lethal heat stress (24, 33). The brief pretreatment stimulates the heat shock response and stress response pathways, leading to the expression of various heat shock proteins (23) that in turn prepare cells for a subsequent severe heat stress. Without the pretreatment, cell viability is rapidly lost during the lethal stress. The severe heat stress brings about the misfolding and aggregation of many proteins, including those involved in fundamental biological processes (such as translation, transcription, and DNA replication, etc.). Cells recover only if these basic machineries are reactivated from the aggregates.

In yeast, protein disaggregation by the heat shock protein Hsp104 is centrally responsible for thermotolerance (35). Members of the Hsp100 family of protein remodeling factors also ensure thermotolerance by a similar mechanism in bacteria (29), archaea (48), fungi (33), protozoa (16), and plants (22). Trehalose, a disaccharide thought to prevent misfolding and aggregation, also augments thermotolerance in yeast and other organisms (41). Hsp104 and the trehalose biosynthetic enzymes (Tps1/Tps2) are overexpressed via the heat shock response and stress response pathways upon the exposure of yeast to a mild heat shock (13, 30) and provide a survival advantage in the case of a subsequent severe stress (36).

The importance of Hsp104 in protein aggregation surveillance is further underscored by its central role in the inheritance of protein aggregates to maintain prions and to regulate longevity in yeast. Prions in yeast are epigenetically inherited aggregated states of certain proteins (see reference 53 for a review). Hsp104 is thought to ensure epigenetic prion inheritance by disaggregating large aggregates into smaller pieces amenable for easy transfer to daughter cells (40). More recently, Hsp104 was found to be important in the asymmetric retention of damaged and aggregated proteins in the aged mother cells and was thought to influence the Sir2-mediated regulation of longevity (9).

Hsp104 is a member of the Hsp100 family of protein remodeling factors that contain two ATPase domains of the AAA+ superfamily. It assembles into hexamers, forming a central pore through which unfolded polypeptides are thought to be translocated to achieve protein disaggregation (27). Although Hsp104 mutants with reduced hexamer assembly in vitro correlates with reduced in vivo function, there is no direct evidence that hexamerization regulates Hsp104 activity in vivo. In each monomer, ATP hydrolysis and peptide translocation appears to be coordinated by the coiled-coil domain (2, 15, 51). Hsp70/Hsp40 chaperones may facilitate the recognition and unfolding of polypeptides by Hsp104 and also may act subsequently to facilitate the folding of the unfolded polypeptide (11). Despite the relatively detailed mechanistic elucidation of Hsp104-mediated disaggregation, the question of the cellular regulation of Hsp104 function has not been addressed.

Here, we have carried out a genome-wide screen to identify the genes required for aggregation clearance by subjecting the yeast gene deletion library to a heat treatment regimen that requires protein disaggregation for survival. We demonstrate that Ssd1 is required for Hsp104-mediated protein disaggregation.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Yeast strains and plasmids.

The plasmids, strains, and primers used in this study are listed in Table 1. Yeast cells were grown in rich YPD medium (1% yeast extract, 2% bactopeptone, 2% glucose) or in minimal medium deficient for appropriate nutrients for selection using standard procedures. The transformation of yeast was performed using a standard lithium acetate-polyethylene glycol method (10). p425cFFL-green fluorescent protein (GFP) was a kind gift from John Glover (44). Overexpression plasmids corresponding to the single-gene deletions were obtained from the yeast FLEXgene overexpression library (4). The yeast FLEXgene collection contains sequence verified full-length expression-ready plasmids for 5,240 yeast genes. The plasmids used in this study express the genes from a galactose-inducible promoter. Plasmids carrying the polymorphic variants of SSD1 were kind gifts from Ted Powers (34).

TABLE 1.

Plasmids, yeast strains, and oligonucleotides used in this study

| Plasmid, strain, or oligonucleotide primer | Description, genotype, or sequence | Reference or source |

|---|---|---|

| Plasmid | ||

| p425cFFL-GFP | FFL fused to GFP | 44 |

| pPL092 | SSD1-v (JK9-3da allele) in pRS316 | 34 |

| pPL093 | SSD1-d (W303a allele) in pRS316 | 34 |

| pAG32 | HYG B resistance cassette | 50 |

| p2HGPD | Empty vector for p2HGPDHsp104 | S. Lindquist |

| p2HGPDHsp104 | Plasmid containing Hsp104 under the GPD promoter | S. Lindquist |

| pRS416GAL | Empty vector for pRS416GALHsp104 | S. Lindquist |

| pRS416GALHsp104 | Plasmid containing Hsp104 under the Gal promoter | S. Lindquist |

| S. cerevisiae strain | ||

| BY4741 | MATahsi3Δ1 leu2Δ0 met15Δ0 ura3Δ0 | Open Biosystems |

| orfΔ | MATahsi3Δ1 leu2Δ0 met15Δ0 ura3Δ0 orf::KanMX | Open Biosystems |

| Y8835 | MATα ura3Δ::nat R can1Δ::STE2pr-Sp_his5 lyp1Δ his3Δ1 leu2Δ0 ura3Δ0 met15Δ0 LYS2+ | 45 |

| Y8835hygR | MATα ura3Δ::hygR can1Δ::STE2pr-Sp_his5 lyp1Δ his3Δ1 leu2Δ0 ura3Δ0 met15Δ0 LYS2+ | This study |

| Primer | ||

| SSD1-A | 5′TGGTACCCTAAACATTTTGGTCTTA3′ | |

| SSD1-B | 5′CCCAGGATTATTGCTATTGTTATTG3′ | |

| SSD1-C | 5′AGTTCATGGAGATCAACTACCTTTG3′ | |

| SSD1-D | 5′TTGTAAATATTGAAAAGAAGGCTGC3′ | |

| SSD1-dF | 5′ATTAAACGTTGGCCAATCACATC3′ | |

| SSD1-dR | 5′TTTCCAATAAGGACAGGGTGG3′ | |

| SSD1-V | 5′GAATTTTACGGACACTAATGAGTAC3′ | |

| Ssd1-d | 5′GAATTTTACGGACACTAATGAGTAG3′ | |

| YPL101W-A | 5′GCGATAATCAAGGAGAATATCAGTG3′ | |

| YPL101W-D | 5′TCTGTCTATTTCAAATCCAAAGGAG3′ | |

| YEL013W-A | 5′AAATCTGAATAATTTCTCTTTCCCG3′ | |

| YEL013W-D | 5′TATACTACGGAACAAAGACAGCCTC3′ | |

| YCL036W-A | 5′GGTCCAGAGTAATCCTGATGTTCTA3′ | |

| YCL036W-D | 5′CGTTATATGAGATTAATGGCCAAAG3′ | |

| YCL056C-A | 5′TGTTTGAGCTCGATACTAACTTCCT3′ | |

| YCL056C-D | 5′GTAAAGACTTGCAAAACCTGTCAAT3′ | |

| YOL081W-A | 5′TGCCCAACGATTATCTATTCTACAT3′ | |

| YOL081W-D | 5′ACAGAAACACTTTCAACTAAGACGG3′ | |

| Ura3HygRFdel | 5′AGTTTTGACCATCAAAGAAGGTTAATGTGGCTGTGGTTTCAGGGTCCATACAGCTGAAGCTTCGTACGC3′ | |

| Ura3HygRRdel | 5′TCTTTCCAATTTTTTTTTTTTCGTCATTATAGAAATCATTACGACCGAGATTCCCGGGCATAGGCCACTAGTGGATCTG3′ | |

| YCL060C-A | 5′TTTAACGTACCTATCCATTCCGTTA3′ | |

| YCL060C-D | 5′TATCCTCTCCGATATTATCACCGTA3′ | |

| YGR240C-A | 5′TTCCGCTCTTAATAAAGGAGTTTTT3′ | |

| YGR240C-D | 5′GATTAAGCACACCCTAAAACTTGAA3′ | |

| YLR414C-A | 5′TATTTCCAAATCGGGCGTACTAT3′ | |

| YLR414C-D | 5′ATTATTTCTGGCTCTTCTCCATTTT3′ | |

| YCR009C-A | 5′ACTTTTAGGTTAGCGGAGAAGATGT3′ | |

| YCR009C-D | 5′CGTATCTTATTCCTCGCTTCTATTG3′ | |

| YIL040W-A | 5′GCCACAGACAGCTATCTCTATGAAT3′ | |

| YIL040W-D | 5′TTCTGGATGGAAAGATGGATAAGTA3′ | |

| YOR360C-A | 5′GCACAATTTTTCCTCTTTTCTTTTT3′ | |

| YOR360C-D | 5′TTTAGATTACACCTGTTTTTGCACC3′ | |

| YMR032W-A | 5′CCGAGGTATATGATTTCCTCTTTGGG3′ | |

| YMR032W-D | 5′AGTTACAAATCCGGAGAGGTGTCCTT3′ | |

| YBL094C-A | 5′GTTTGATCTAGACGGTACAGGAAAA3′ | |

| YBL094C-D | 5′GAAGATGCACCATGTCTTATTCAGT3′ | |

| YJL183W-A | 5′ATCCAGGAAGAGATTAACCAGCTAT3′ | |

| YJL183W-D | 5′AAAAGCTTCTTCTTCTTCTTCCTTG3′ |

All deletion strains were constructed by replacing an entire open reading frame (ORF) with a selectable marker after the transformation of a linear fragment of DNA constructed by PCR. Deletion strains were constructed either with hygromycin (HYG) (an MX4-HYG cassette amplified from pAG32 [12] or with kanamycin [KanMX] amplified from pFA6a [50]) as the selectable marker using standard forward and reverse primers with 50 bp homologous to the 5′ or 3′ end of the target ORF, followed by 20 bp homologous to the MX4 cassette.

Genomic screen.

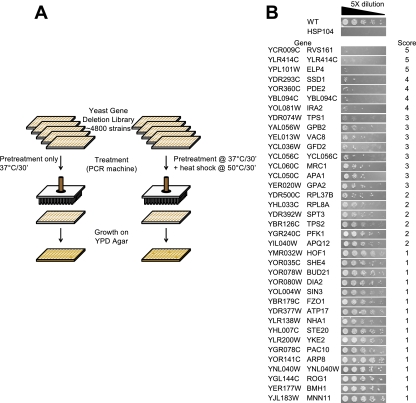

Saccharomyces cerevisiae strain BY4741 (MATa his3Δ1 leu2Δ0 met15Δ0 ura3Δ0) and deletion mutant derivatives were obtained from Open Biosystems, Huntsville, AL. The gene deletion library representing viable haploid deletions of 4,786 yeast ORFs were grown in YPD medium in 96-well plates. Deletion strains were inoculated, using a 96-pin tool (VP Scientific, San Diego, CA), into another plate containing 200 μl of YPD medium and grown at 30°C for 72 h. The deletion strains were subjected to pretreatment at 37°C for 30 min and subsequently heat shocked at 50°C for 30 min. Controls received only pretreatment. The cells were spotted on YPD agar medium in omnitrays (Nunc). The spots were grown overnight at 30°C and imaged using a gel documentation system (UVP Scientific). The viable cells were scored against the wild type and the hsp104 strain. The entire screen was performed in duplicate to eliminate false positives. A schematic diagram of the screen is shown in Fig. 1A.

FIG. 1.

Genes that influence the acquisition of thermotolerance in yeast. (A) A schematic diagram of the genome-wide screen for identifying genes essential for regulating Hsp104-mediated protein disaggregation. (B) Gene names and their respective thermotolerance of the hits identified in the screen. Cells grown in YPD medium were subjected to heat shock (37°C for 30 min and 50°C for 30 min) and spotted on YPD to measure acquired thermotolerance. The scores on the right indicate the strengths of their thermotolerance phenotypes compared to those of wild-type (WT) and Hsp104-deficient cells. The hits are arranged based on their thermotolerance scores.

Aggregate clearance assay.

The deletants, along with wild-type and hsp104Δ strains (as controls), were transformed with p425cFFL-GFP (44) and grown to mid-log phase (optical density at 600 nm [OD600] of 0.5) in medium lacking leucine. Cells were subjected to pretreatment at 37°C for 30 min, followed by sublethal heat shock at 46°C for 30 min. The synthesis of all new protein was blocked by the addition of cycloheximide (10 μg/ml). The recovery of the aggregated proteins was monitored either using fluorescence microscopy to look for punctuate aggregates of GFP or by measuring the activity of firefly luciferase (FFL).

FFL activity was monitored before heat shock, immediately after heat shock, and at various times during the recovery period. Equal numbers of cells were taken in 50 μl of medium in a 96-well luminescence plate (Corning Inc). Using the autoinjector in a BMG luminometer, 50 μl d-luciferin (Sigma) substrate buffered with 100 mM potassium phosphate (pH 3.0) was injected into the cells and vigorously shaken for 3 s. The resulting luminescence was integrated during a 10-s collection time. Data are expressed as percent FFL activity compared to the values obtained prior to heat shock. Appropriate controls, including wild-type and hsp104Δ cells carrying empty vector, were used, and the data were plotted as the percent FFL activity recovered.

Growth analysis.

Untreated (control) and treated (pretreatment alone or treatment followed by sublethal heat shock) cells were inoculated at an OD600 of 0.05 in YPD medium. Cultures were allowed to grow at 25°C and kept in suspension by vigorous shaking every 2 min. Light scatter (OD600) was measured every 10 min on a Safire spectrophotometer (Tecan) for a period of 24 h. The mean values of three replicates located at different regions of the plate were plotted.

Mitochondrial function deficiency was examined by the growth of cells on glycerol plates (1% yeast extract, 2% peptone, 2% glycerol, and 2% agar). Glycerol was used as the sole carbon source.

Trehalose estimation.

Trehalose was extracted from yeast cells and assayed as described previously (21), with minor modifications. Briefly, exponentially growing yeast cells were washed twice in ice-cold water to remove free glucose. Cells were resuspended in 10 to 20 volumes of ice-cold water and incubated at 95°C for 20 min. The trehalose (a disaccharide of glucose) released into the supernatant was treated with trehalase (20 mU/sample; Sigma Chemical Co.), which hydrolyzes trehalose to two molecules of glucose. After 6 h of incubation at 37°C, the amount of glucose generated was assayed with a glucose assay kit (Sigma) containing hexokinase and glucose-6-phosphate dehydrogenase per the manufacturer's instructions. Glucose released was estimated using a standard curve for absorbance values at 340 nm that was drawn using known concentrations of glucose. The preexistent glucose in each sample was assayed simultaneously without adding trehalase. This amount was less than 5% of the amount generated by trehalose and was subtracted from sample values. The cellular content of trehalose was expressed in micrograms per milliliter.

Back-crosses and complementation test.

Hits obtained from the genome-wide screen were back-crossed to a wild-type strain of the α mating type carrying a HYG resistance marker using the selection strategy described previously for the synthetic genetic array analysis (45). The HYG-resistant α strain (Y8835hygR) was generated from the original nourseothricin (Y8835)-resistant strain (a gift from Charles Boone).

The deletion strains were transformed with the respective overexpression plasmids. Overexpression plasmid constructs were obtained from the Yeast FLEXgene collection (a gift from Susan Lindquist) (4). In addition, to test for the nature of genetic interactions between Ssd1 and Hsp104, we also tested for cross-complementation by overexpressing Hsp104 in Ssd1-deficient cells and Ssd1 in Hsp104-deficient cells. The vector controls and deletion strains with the plasmids were subjected to heat shock and then spotted onto appropriate selection plates in fivefold serial dilutions. The resulting plates were documented after 30 h of incubation at 30°C.

Immunoblotting.

Wild-type cells and the required mutant yeast cells were grown in an appropriate growth medium to exponential phase. The cell density was equalized to an OD600 of 0.5. Cells were treated as indicated for each experiment. Cells were collected by centrifugation and resuspended in 500 μl of lysis buffer [20 mM sodium phosphate buffer, pH 6.5, 20 μM 4-(2-aminoethyl) benzenesulfonyl fluoride hydrochloride and Halt protease inhibitor EDTA free (Pierce Biotechnology, Rockford, IL)]. Glass bead lysis was carried out, and the protein concentration was determined using the bicinchoninic assay kit (Pierce Biotechnology).

Native gels (6% separating and 4% stacking) were run identically to sodium dodecyl sulfate-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (SDS-PAGE), except no SDS was added to the sample loading dye, gel casting buffers, or the gel running buffer. Samples were prepared in DNA loading dye and were not boiled prior to loading native gels.

Proteins were separated by native PAGE or by SDS-PAGE as necessary and transferred to a polyvinylidene difluoride membrane. The blots were probed with anti-Hsp104 (a gift from Susan Lindquist), anti-Tps1 (a gift from Olga Kandror), anti-Hsp26 (a gift from Johannes Buchner), anti-Ssa1 (a gift from Elizabeth Craig), or anti-Ydj1 (a gift from Doug Cyr) antibody and visualized using chemiluminescence (Pierce). Equal protein loading was verified by staining the membranes with Coomassie brilliant blue.

Cell wall integrity assay.

The sensitivity of cells to calcofluor white (CFW; fluorescence brightener 28; Sigma) was analyzed by spotting serial dilutions of cultures onto YPD plates containing 50 μg/ml CFW.

Sensitivity to Zymolyase was determined based on a previously described method (28). Cells were subjected to a pretreatment followed by a sublethal heat shock as described above to induce cell wall remodeling. Equal numbers of cells were treated with Zymolyase-20T (Seikagaku Corporation, Tokyo, Japan) at 5 μg/ml for different durations at 30°C, and the cells were spotted on YPD plates to assess viability.

Fluorescence microscopy.

For GFP fluorescence experiments, live cells were placed on polylysine-coated coverslips after appropriate treatments and mounted on slides.

For immunofluorescence experiments, cells were given pretreatment followed by sublethal heat shock and were immediately fixed in paraformaldehyde to prevent disaggregation during subsequent steps. Cells were partially permeabilized by Zymolyase treatment to allow access to antibodies. Identically treated hsp104Δ cells were used as controls for the nonspecific binding of anti-Hsp104 polyclonal antibodies (gifts from Sue Lindquist). Goat anti-rabbit immunoglobulin G antibody conjugated to Alexa 555 (Invitrogen) was used as the secondary antibody. The cells were mounted with Vectashield mounting reagent with 4′,6′-diamidino-2-phenylindole (DAPI) (to stain DNA).

Filter sets for GFP, Texas red, and DAPI were used to observe green (GFP), red (Alexa 555), or blue (DAPI) fluorescence. Fluorescence micrographs were obtained using a 100× oil-immersion objective in a Zeiss Axioplan 2 microscope equipped with an AxioCam MR digital camera.

Immunoprecipitation.

Native yeast lysates were prepared as described above from wild-type, ssd1Δ, or hsp104Δ cells. One hundred fifty to 250 μg of total protein was taken into a new tube, and 5 μg of Hsp104 monoclonal antibody (2B; a generous gift from Susan Lindquist) was added. The solution was incubated on a shaker in the cold. Ultralink protein A/G beads (Pierce) were added and incubated for 1 h at 4°C. The beads were allowed to settle (note: centrifugation was avoided to prevent the pelleting of protein aggregates). The beads were washed with Tris-buffered saline. The bound proteins were released by boiling the beads in SDS loading dye. Identically treated samples but without the addition of the Hsp104 antibody were used as the negative controls. The specificity of the immunoprecipitation was confirmed by using lysates from hsp104Δ cells. The samples and the corresponding total lysates were separated by SDS-PAGE and immunoblotted for the indicated antibodies.

RESULTS

Genes essential for thermotolerance in yeast.

We carried out a genome-wide screen in yeast using the haploid nonessential gene deletion mutant library (BY4741) to identify genes required for protein disaggregation during the acquisition of thermotolerance (Fig. 1A). In order to facilitate the identification of such genes and to minimize the identification of genes playing a role in innate thermotolerance, the control set received pretreatment but not the lethal heat stress. Gene deletants growing poorly on control plates were ignored. Further, the entire screen was repeated twice, and only the genes that appeared in both independent screens were picked as hits. In addition to Hsp104, deletions of 37 other genes were found to reduce the acquisition of thermotolerance to various degrees. Figure 1B summarizes the genes that reduce the ability of cells to acquire thermotolerance when deleted (genes descriptions are listed in Table 2). The validity of our approach was obvious by the ability of the screen to pick genes previously known to be defective (severely to mildly) in acquired thermotolerance: HSP104 (35), IRA2 (43), PDE2 (37), TPS1 (6), and TPS2 (6).

TABLE 2.

Characteristics of the thermotolerance-defective mutants from the genome-wide screena

| Gene | Score | Function | Hsp104 expression | Tps1 expression | Trehalose synthesis | Aggregate clearance |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Wild type | + | + | + | + | ||

| hsp104 | 5 | Heat shock protein | − | + | + | − |

| rvs161 | 5 | Amphyphysin-like lipid raft protein/vesicle trafficking | + | + | + | − |

| ylr414c | 5 | Unknown | + | + | + | ± |

| elp4 | 4 | Histone acetyltransferase/transcription factor | − | − | + | ± |

| ssd1 | 4 | Cellular integrity/TOR pathway/autophagy | + | + | + | − |

| pde2 | 4 | High-affinity cAMP phosphodiesterase | − | − | + | ± |

| ybl094c | 4 | Unknown | + | + | + | ± |

| ira2 | 4 | Inhibitory GAP of the Ras-cAMP pathway | − | − | − | − |

| tps1 | 3 | Trehalose metabolism | − | − | − | ± |

| gpb2 | 3 | cAMP/PKA signal transduction, G-protein β-subunit | + | + | + | + |

| vac8 | 3 | Vacuolar inheritence/microautophagy/Cvt pathway | + | + | + | − |

| gfd2 | 3 | Putative mRNA export | − | − | − | ± |

| ycl056c | 3 | Hypothetical | + | + | ND | ND |

| mrc1 | 3 | Mediator of the replication checkpoint | + | + | + | + |

| apa1 | 3 | Nucleotide metabolism | + | + | + | ± |

| rpl37b | 2 | Large (60S) ribosomal subunit | + | + | + | ± |

| rpl8a | 2 | Large (60S) ribosomal subunit | − | − | + | ± |

| tps2 | 2 | Trehalose metabolism | − | − | − | ± |

| pfk1 | 2 | Phosphofructokinase | + | + | + | ± |

| apq12 | 2 | Nucleocytoplasmic transport of mRNA | − | − | − | ± |

A plus sign indicates normal, a minus sign indicates deficient, and a plus/minus sign indicates the intermediate phenotype. ND, not determined.

To estimate the strength of the phenotype, the hits were cherry picked into a new 96-well plate and reexamined by plating fivefold serial dilutions after the treatment regimen. The hits were scored based on a comparison to results for wild-type and Hsp104-deficient cells. Three deletants, namely rvs161Δ, ylr414cΔ, and elp4Δ, were as defective as hsp104Δ cells (with a score of 5 on a scale of 1 to 5). Four more deletants, namely ssd1Δ, ybl094cΔ, ira2Δ, and pde2Δ, were only marginally more thermotolerant than hsp104Δ cells (score of 4). Fourteen mutants were more thermotolerant than hsp104Δ mutants but significantly deficient for thermotolerance compared to the wild type (eight with a score of 3 and six with a score of 2). The remaining 16 deletants showed only minor reductions in thermotolerance compared to that of wild-type cells (score of 1).

Previously characterized genetic and physical interactions among the genes provide useful information about interrelated pathways that regulate thermotolerance. We used the BioGRID (version 2.0.42; July 2008 release) database, which contains 98,698 physical and 42,999 genetic nonredundant interactions, to map interactions within the hits. The map was visualized using Osprey (version 1.2.0) (data not shown). We observed that 21 of the 38 hits (55%) were found in a single network. The nodes (hits) in this network belonged to diverse biological processes such as the signaling pathway (IRA2, PDE2, GPB2, GPA2, BMH1, STE20, and SSD1), transcriptional complexes (ELP4, SPT3, SIN3, and ARP8), DNA replication (MRC1 and DIA2), protein folding machinery (YKE2, PAC10, TPS1, TPS2, and HSP104), and other processes (RVS161, MNN11, and APQ12). The edges signify genetic or physical interactions identified in various studies. A convergence of several pathways appeared to confer the acquisition of thermotolerance in yeast. Further, many hits were involved in the cyclic AMP/protein kinase A (cAMP/PKA) pathway that regulates the heat shock response and stress response pathways (unpublished observations).

Analysis of protein disaggregation.

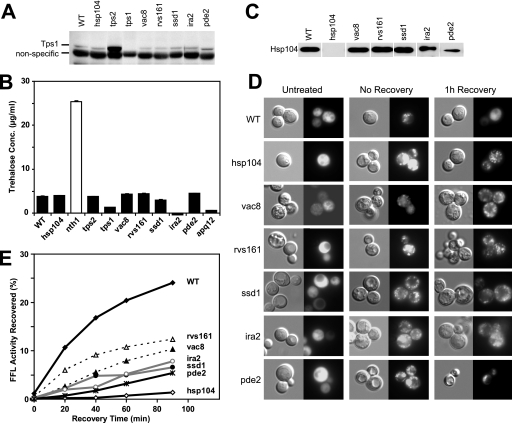

Since diverse pathways may be involved in thermotolerance, we wanted to understand how these pathways affected protein disaggregation. We tested whether the hits fall into one of the two major factors, namely Hsp104-mediated disaggregation and the synthesis of trehalose, known to influence thermotolerance in yeast. Specifically, the hits scoring between 5 and 2 were tested for (i) the expression of Hsp104 and Tps1 (analyzed by immunoblotting); (ii) the synthesis of trehalose (measured by biochemical methods) (21); and (iii) protein disaggregation (directly monitored by the microscopic examination of the aggregated status of a heat-sensitive FFL-GFP fusion protein) (44). In order to do this in live cells, we lowered the severe heat shock to 46°C. At this temperature of heat shock, wild-type but not Hsp104-deficient cells allowed protein disaggregation during recovery (32). Interestingly, hsp104Δ cells with defective protein disaggregation showed little recovery after 24 h compared to that of the wild type, but it showed complete recovery after 48 h (data not shown). All other mutants tested were fully viable after 48 h of growth (data not shown). A summary of our analysis of the hits is provided in Table 2. Results are described below in detail for wild-type, hsp104Δ, rvs161Δ, vac8Δ, ssd1Δ, ira2Δ, and pde2Δ cells (Fig. 2).

FIG. 2.

Trehalose synthesis and protein disaggregation in various mutants. Gene deletion mutants were subjected to the heat shock regimen (37°C for 30 min and 46°C for 30 min) and tested for Tps1 expression (A), trehalose synthesis (B), and Hsp104 expression (C). The same protein samples were used for immunoblotting with Tps1 (A) or Hsp104 (C). The nonspecific band with the Tps1 antibody indicates equal loading of samples. For panel B, the amount of trehalose was estimated using biochemical methods. Protein disaggregation was examined in wild-type (WT) and mutant cells expressing FFL-GFP. Disaggregation was monitored visually by GFP fluorescence microscopy (D) or biochemically by luciferase reactivation (E) before heat shock (untreated), after heat shock (no recovery), and after 1 h recovery at 30°C. The recovery of FFL activity was monitored as a time course using luminescence methods. All cells expressed similar amounts of FFL-GFP before treatment. FFL-GFP aggregated similarly in all cells after the heat treatment regimen, resulting in <2% of FFL activity of untreated cells. The synthesis of new FFL-GFP was blocked by the addition of cycloheximide immediately after heat shock. The recovery of aggregated FFL-GFP was monitored after 1 h at 30°C (D) and was monitored as a time course (E).

Trehalose.

Several studies have demonstrated the importance of trehalose in the acquisition of thermotolerance in yeast and other organisms (41). To test if the inability to synthesize trehalose reduced thermotolerance in the mutants, we first monitored the expression of Tps1 (trehalose synthase) after heat shock in various mutants (Fig. 2A). Tps1 expression was similar to that of the wild type in all of the mutants, with the following exceptions: Tps1 was absent in tps1Δ cells and overexpressed in tps2Δ cells. The cross-reactivity of the antibody with another protein indicated equal loading in all samples.

Next, we directly measured trehalose accumulated in various mutants after heat shock using a coupled biochemical assay (Fig. 2B). Cells lacking Nth1 (neutral trehalose; a trehalose-degrading enzyme) accumulated high levels of trehalose (more than fivefold) and were used as a positive control for the assay. tps1Δ and ira2Δ cells accumulated less trehalose than wild-type cells. Other mutants (vac8Δ, rvs161Δ, ssd1Δ, and pde2Δ) had trehalose accumulation comparable to that of the wild type. Although elp4Δ and ybl094cΔ cells had a severe loss of thermotolerance, trehalose was accumulated at normal levels; on the other hand, apq12Δ and rpl8aΔ cells accumulated very little trehalose but had marginal defects in thermotolerance (data not shown). Thus, there was a lack of a clear correlation between thermotolerance deficiency and trehalose amounts, suggesting that the amount of trehalose was not a critical determinant of acquired thermotolerance.

Hsp104-mediated protein disaggregation.

We next investigated Hsp104 expression after heat shock (Fig. 2C and Table 2). Genes in the Ras/cAMP/PKA pathway (namely, IRA2 and PDE2) previously have been shown to be able to regulate the heat shock response and thereby the expression of Hsp104 (39). In agreement with this finding, we observed a reduction in Hsp104 expression following heat shock in ira2Δ and pde2Δ mutants. Hsp104 was expressed at levels comparable to those of the wild type in vac8Δ, rvs161Δ, and ssd1Δ mutants. Lower Hsp104 expression was observed in elp4Δ, tps1Δ, gfd2Δ, rpl8aΔ, tps2Δ, and apq12Δ mutants (Table 2). Interestingly, despite the low levels of Hsp104, Tps1, and trehalose in apq12Δ cells, substantial thermotolerance (a score of 2) (Fig. 1B) could be observed, suggesting that Apq12 negatively influences cell survival after heat shock.

To assess disaggregation in the mutants, we made use of a construct expressing FFL fused to GFP (FFL-GFP) (44). FFL-GFP misfolds and aggregates when cells are subjected to temperatures higher than 43°C (44). Protein disaggregation was monitored visually by GFP fluorescence microscopy and biochemically by the reactivation of FFL in live cells after nonlethal heat shock at 46°C. The synthesis of new FFL-GFP during the recovery period was prevented by treating cells with cycloheximide (a protein synthesis inhibitor). Aggregates of FFL-GFP formed were observed as fluorescent dots in mutants and the wild type following the nonlethal heat shock (Fig. 2D). Upon the return to normalcy (30°C), the fluorescent puncta disappeared within 1 h in wild-type cells. In cells lacking Hsp104, the punctate pattern of GFP fluorescence did not become diffuse for 6 h or more (data not shown). Most of the mutants tested (except mrc1Δ and gpb2Δ) showed somewhat reduced disaggregation compared to that of wild-type cells, thereby suggesting the centrality of protein disaggregation in acquired thermotolerance (Table 2). Reduced Hsp104 expression in some of the mutants (e.g., ira2Δ, pde2Δ, elp4Δ, and gfd2Δ) could easily explain the loss of aggregate clearance. Although some mutants (e.g., ylr414cΔ and ybl094cΔ) expressed Hsp104 comparably to the wild type, FFL-GFP aggregates were not cleared efficiently. Remarkably, the disappearance of punctate GFP fluorescence was significantly delayed in three mutants (rvs161Δ, vac8Δ, and ssd1Δ) that showed normal expression of Hsp104 and Tps1 and also synthesized normal levels of trehalose. These results meant that the accumulation of wild-type levels of Hsp104 alone could not account for aggregate clearance. To confirm this observation, we monitored the reactivation of the biochemical activity of FFL in these mutants (Fig. 2E). All cells expressed comparable amounts of FFL (as determined by initial activity in untreated cells), demonstrating that none of the genes plays a role in regulating the expression of FFL-GFP from the Met25 promoter. After heat shock at 46°C, FFL activity dropped to <2% in all cells, suggesting that none of the mutants affected its aggregation. About 25 to 30% of the FFL activity was restored in wild-type cells after 90 min, but hsp104Δ cells recovered only negligible activity during this time. While ∼10% reactivation of FFL was observed in rvs161Δ and vac8Δ cells, only about 6 to 7% FFL was reactivated in ira2Δ, pde2Δ, and ssd1Δ cells (Fig. 2E).

From this analysis, it is clear that most of the hits showed some reduction in protein disaggregation compared to results for the wild type (Table 2), suggesting that several pathways impinge upon Hsp104 expression and/or activity after heat shock. In many cases, reduced Hsp104 or Tps1 expression was predictive of the reduced disaggregation. There were only three mutants (rvs161Δ, ssd1Δ, and vac8Δ) that had wild-type levels of Hsp104, Tps1, and trehalose, but they were severely defective in protein disaggregation. We suspected that these three genes influence Hsp104-mediated protein disaggregation directly or indirectly.

Characterization of Ssd1-deficient mutants.

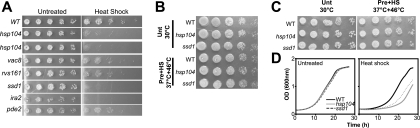

In order to eliminate the possibility of interference from other background mutations in these strains, we backcrossed the mutants in the BY4741 (MATa) background with a wild-type MATα strain. Appropriate markers were used to select MATa haploid progeny using an approach developed for synthetic genetic array analysis (45, 46). Of the newly created mutants, those lacking IRA2, PDE2, SSD1, VAC8, and RVS161 showed the loss of thermotolerance (Fig. 3A). However, the strength of the phenotype for pde2Δ, rvs161Δ, and vac8Δ was slightly reduced, suggesting other genetic determinants influenced the thermotolerance phenotype in the original mutants obtained from the library. In agreement, plasmids expressing PDE2, RVS161, or VAC8 were able to partially complement the thermotolerance defect in pde2Δ, rvs161Δ, and vac8Δ mutants, respectively (data not shown). Cells lacking Hsp104, Ssd1, or Ira2 showed a loss of thermotolerance similar to that of the original mutants, demonstrating that it was a monogenic trait in these cases. While the importance of HSP104 and IRA2 in thermotolerance has been previously documented, our studies have identified SSD1 as a novel player in thermotolerance.

FIG. 3.

Characterization of mutants lacking Ssd1. (A) The original mutants obtained from the library (hsp104Δ, vac8Δ, rvs161Δ, ssd1Δ, ira2Δ, and pde2Δ) were back-crossed to generate new mutants devoid of background defects. The new mutants were tested for thermotolerance after being treated with the standard heat shock regimen (37°C for 30 min and 50°C for 30 min). (B) The ability of ssd1Δ cells to utilize glycerol as a carbon source via mitochondrial respiration. Cells lacking Ssd1 or Hsp104 grew as efficiently as wild-type (WT) cells on glycerol medium, demonstrating that they did not show a defect in mitochondrial function (petite phenotype). Unt, untreated; Pre+HS, pretreatment and heat shock. The consequence of reduced protein aggregation in ssd1Δ mutants was examined by growth on YPD agar plates (C) or in YPD broth (D) after heat shock at 46°C. (C) The heat shock at 46°C had no effect on the viability of wild-type, hsp104Δ, or ssd1Δ cells, as indicated by their growing (48 h) on YPD agar as efficiently as untreated cells. (D) A significant delay in the rate of recovery could be observed in cells deficient for protein disaggregation (hsp104Δ and ssd1Δ) immediately after heat shock, as indicated by an extended lag phase of growth in YPD broth.

The loss of mitochondria or its DNA leads to small anaerobically growing colonies (known as the petite phenotype) that may mislead the interpretation of results from the ssd1Δ mutants. To test whether ssd1Δ mutants exhibited a petite phenotype, we tested for their ability to grow on glycerol as the sole carbon source before and after heat shock. The utilization of glycerol requires full mitochondrial function. Mutants lacking Ssd1 grew on glycerol as efficiently as wild-type cells before and after heat shock, suggesting that ssd1Δ cells were not simply defective in mitochondrial function (Fig. 3B). Thus, we decided to examine in detail the role of SSD1 in regulating protein disaggregation and in the acquisition of thermotolerance in yeast.

We first confirmed that cells lacking Ssd1 retained complete viability after the 46°C heat shock (Fig. 3C). To investigate the biological consequence of reduced protein disaggregation in the mutants after a nonlethal heat shock, we examined their ability to resume growth at normal temperatures. Results for cells deficient for Hsp104 and Ssd1 were compared to those of wild-type controls (Fig. 3D). All cells grew identically in untreated or pretreated (37°C for 30 min) conditions (data not shown). However, after the nonlethal heat shock (46°C for 30 min), the lag phase increased to ∼10 h in wild-type cells and to ∼20 h in hsp104Δ cells. ssd1Δ cells, which showed intermediate levels of protein disaggregation, also showed an intermediate lag-phase length (∼15 h). These results indicate that aggregate clearance is essential for the resumption of growth following nonlethal heat shock and is a determinant of thermotolerance.

SSD1 regulates the acquisition of thermotolerance, protein disaggregation, and cellular integrity.

SSD1 is a polymorphic gene that plays a major role in cellular integrity and suppresses many signal transduction pathways (7, 34, 42). Two genetic variants have been identified, the SSD1-V allele that produces full-length protein and the ssd1-d allele that terminates the protein at the start of a highly conserved RNA binding domain (18) (Fig. 4A). We tested the ability of each allele expressed under the SSD1 promoter on a plasmid to confer acquired thermotolerance to ssd1Δ cells in the BY4741 genetic background (Fig. 4B). Wild-type and hsp104Δ cells were used as controls. In cells carrying only the empty vector, wild-type cells survived the lethal heat shock, but hsp104Δ and ssd1Δ cells died. The SSD1-V allele did not affect the thermotolerance of wild-type or hsp104Δ cells but fully restored thermotolerance in ssd1Δ cells. On the other hand, the ssd1-d allele restored a reduced level of thermotolerance to ssd1Δ cells. The ssd1-d allele also appeared to slightly reduce thermotolerance in wild-type cells, suggesting that ssd1-d was partially dominant over the genomic SSD1-V in thermotolerance. These results confirm that Ssd1 is essential for thermotolerance in yeast.

FIG. 4.

Functional differences between the polymorphic variants of SSD1. (A) Schematic diagrams of the expected protein products (namely, Ssd1-V and Ssd1-d) from the two alleles of SSD1. (B) Differences between the ability of the two allelic variants to confer thermotolerance were examined by comparing the growth of cells with pretreatment alone (Pre) or with a lethal heat shock (Pre+HS). (C) The ability of each Ssd1 variant to restore protein disaggregation in hsp104Δ and ssd1Δ cells was examined by monitoring the reactivation of FFL-GFP after a nonlethal heat shock. WT, wild type; 104, hsp104Δ mutant; ssd1, ssd1Δ mutant; vec, empty vector; SSD1-V, pPL092; ssd1-d, pPL093. The ability of each Ssd1 variant to support cell wall remodeling after heat shock was examined by monitoring the sensitivity to CFW before and after nonlethal heat shock. (D) The ability of wild-type (WT), hsp104Δ, or ssd1Δ cells to grow on YPD plates without (YPD) or with 50 μg/ml CFW (YPD+CFW) was examined. Cells were spotted after no treatment (UT) or after a heat shock (HS; 37°C for 30 min and 46°C for 30 min). (E) Cell wall remodeling after heat shock was examined by sensitivity to zymolyase. Wild-type cells (control) or ssd1Δ cells carrying empty vector or each of the two alleles (SSD1-V and ssd1-d) were subjected to nonlethal heat shock (37°C for 30 min and 46°C for 30 min), followed by treatment with zymolyase for 0 or 30 min. All cells grew similarly when no treatment was given (top). After the nonlethal heat shock, ssd1Δ cells lost viability after treatment with zymolyase for 30 min. Both SSD1-V and ssd1-d alleles fully suppressed the sensitivity of ssd1Δ cells to zymolyase.

The ability of Ssd1 to confer thermotolerance could be related either to a role in protein disaggregation or to its role in the cellular integrity pathway. In order to delineate these possibilities, we first examined whether the expression of the two alleles of SSD1 can restore protein disaggregation in ssd1Δ or hsp104Δ cells. We monitored the reactivation of FFL activity after a nonlethal heat shock in wild-type, hsp104Δ, or ssd1Δ cells carrying empty vector or carrying ORFs for the SSD1-V or ssd1-d allele (Fig. 4C). Initial FFL-GFP activities in all cells were equal before treatment and decreased to less than 1% in all cells immediately after the heat shock. The wild-type cells with or without plasmid-borne SSD1 alleles reactivated about 60% of aggregated FFL (the percent FFL reactivated shown in Fig. 2E is different probably due to growth in a different medium). As previously observed, the loss of Hsp104 abolished FFL reactivation, but the loss of Ssd1 reduced disaggregation to about 30% of that of the wild type. Interestingly, while either allele of SSD1 fully reversed the reduction in FFL reactivation in ssd1Δ cells, neither had any effect on the negligible amounts of FFL reactivated in hsp104Δ cells. These data indicate that Ssd1 potentiated protein disaggregation but did not function as a disaggregase in the absence of Hsp104.

Because cell wall remodeling during heat shock influences cell viability (17), the cellular integrity pathway mediated by SSD1 may play a role in cell survival following a heat shock. If so, ssd1Δ cells may have a weaker cell wall after a heat shock than wild-type cells. To test this, we monitored the sensitivity of yeast to the presence of a cell wall binding dye, CFW, in YPD agar plates before and after a nonlethal heat shock (46°C for 30 min) (Fig. 4D). Cells expressing SSD1-V or ssd1-d were tested. Wild-type and hsp104Δ cells showed no sensitivity to CFW regardless of the Ssd1 variant, suggesting that while Ssd1-mediated cellular integrity regulated Hsp104-mediated protein disaggregation, Hsp104 did not influence cell wall remodeling. However, ssd1Δ cells carrying an empty vector grew poorly on CFW plates with or without heat shock. While the SSD1-V allele suppressed the growth defect in ssd1Δ cells in both conditions, the ssd1-d allele suppressed the defect only after heat shock. These results demonstrate that the ssd1-d allele was functional in cell integrity, but its function depended on the physiological state of the cell. Similar results were obtained when ssd1Δ cells were tested for sensitivity to the cell wall-digesting enzyme Zymolyase (Fig. 4E). Ssd1-deficient cells carrying either an empty vector or the SSD1-V or ssd1-d allele grew similarly to control cells under untreated conditions or after the nonlethal heat shock alone. However, when the heat-shocked cells were incubated with Zymolyase, only ssd1Δ cells carrying an empty vector showed a drastic reduction in viability. This reduction in viability could be suppressed by either allele of SSD1 to restore full viability. We found that both alleles equally supported heat shock-induced cell wall remodeling. These data suggest that both SSD1 alleles were capable of fully restoring protein disaggregation and cell wall remodeling during thermotolerance.

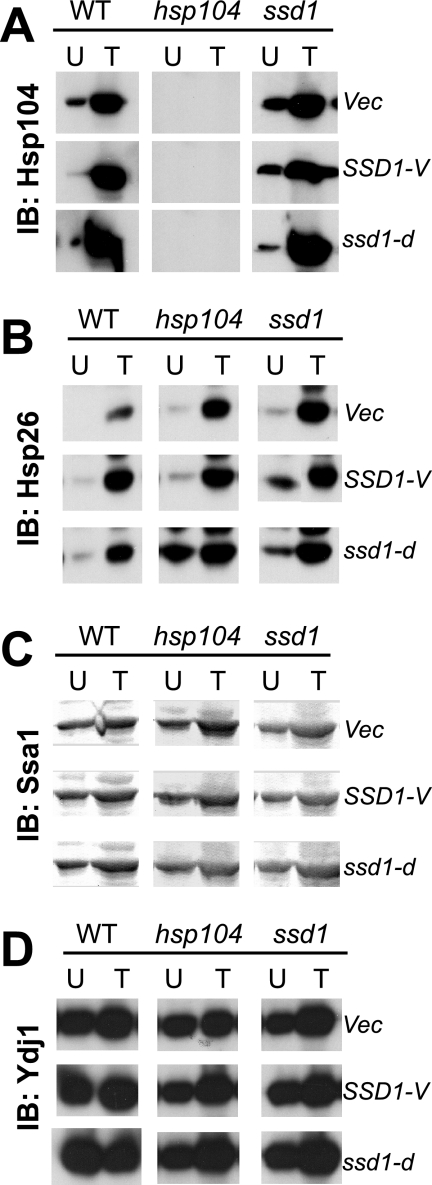

One obvious explanation for this effect would be that Ssd1 influences the expression of other heat shock proteins that are known to participate in protein disaggregation. To evaluate this possibility, the expression patterns of various molecular chaperones, including Hsp104, Ssa1, Ydj1, and Hsp26, were examined by immunoblotting (Fig. 5). No significant differences were observed between wild-type and ssd1Δ cells, suggesting that the reduction in protein disaggregation in ssd1Δ cells was not due to a reduction in the induction of the heat shock response. To examine whether the effect of Ssd1 also affected Hsp104 function in the maintenance of prions, we deleted the SSD1 gene from [PSI+] and [psi−] cells of strain 74D-694 and monitored them for growth on medium without adenine and for red-white colony coloration. No difference was obvious between SSD1 cells and ssd1Δ cells of these prion strains, suggesting that Ssd1 affected only Hsp104 function under heat shock conditions (unpublished observations). The loss of Ssd1 in both the [PSI+] and the [psi−] cells of the 74D-694 strain lead to a loss of thermotolerance, demonstrating that Ssd1 was important in strains other than BY4741 (data not shown).

FIG. 5.

Heat shock response in ssd1Δ cells. Wild-type (WT), hsp104Δ, or ssd1Δ cells carrying either an empty vector (vec) or a plasmid carrying the SSD1-V or ssd1-d allele were examined for the expression of Hsp104 (A), Hsp26 (B), Ssa1 (C), and Ydj1 (D) by immunoblotting (IB) with appropriate antibodies. Cells were left untreated (U) or were heat shocked (T; 37°C for 30 min and 46°C for 30 min).

Ssd1 regulates the disaggregation function of Hsp104.

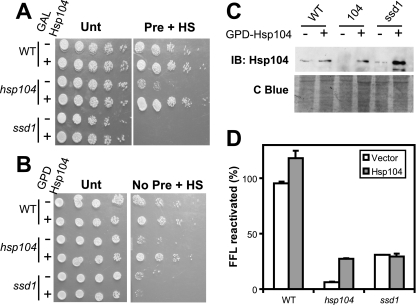

We next tested whether the overexpression of Hsp104 in ssd1Δ cells could suppress the loss of the thermotolerance phenotype in these cells. Wild-type, hsp104Δ, and ssd1Δ cells carrying an empty vector or a plasmid carrying galactose-inducible HSP104 were examined for thermotolerance after inducing Hsp104 expression in galactose medium (Fig. 6A). Hsp104 overexpression had no effect on untreated cells and did not influence the thermotolerance of wild-type cells. Hsp104 restored thermotolerance to cells lacking Hsp104 as expected. Interestingly, Hsp104 expression did not impart thermotolerance to ssd1Δ cells, suggesting that Hsp104 was unable to function in the absence of Ssd1. When we examined the cells for their ability to disaggregate FFL-GFP, no difference was observed between control (empty vector) and Hsp104-overexpressing ssd1Δ cells (data not shown).

FIG. 6.

Hsp104 function in the absence of Ssd1. (A) Wild-type (WT), hsp104Δ, or ssd1Δ cells transformed with an empty plasmid (−) or carrying HSP104 under the control of the GAL promoter (+) were examined for thermotolerance. Cells either received no treatment (Unt) or the pretreatment was followed by a lethal heat shock (Pre+HS). (B) The ability of Hsp104 to confer thermotolerance independently of pretreatment was examined by transforming cells with empty plasmid (−) or carrying HSP104 under the control of the constitutively active GPD promoter (+). Cells were untreated (Unt) or subjected to lethal heat shock without pretreatment (No Pre + HS). (C) The expression of Hsp104 in each of the strains shown in panel B was examined by immunoblotting (IB). C Blue, Coomassie blue. (D) Protein disaggregation in cells expressing GPD-Hsp104 was monitored by FFL reactivation after 60 min of recovery from a nonlethal heat shock at 46°C for 30 min.

Ssd1 could exert its effects on Hsp104 function via its role in various signaling pathways triggered by the pretreatment heat shock. Therefore, it is important to determine whether the effect of Ssd1 on Hsp104 function depends on pretreatment. To test this, we eliminated the pretreatment step by overexpressing Hsp104 from the constitutively active GPD promoter (Fig. 6B). As has been demonstrated earlier (36), cells not given a pretreatment at 37°C are extremely susceptible to killing by heat shock at 50°C. Wild-type, hsp104Δ, or ssd1Δ cells carrying an empty vector lost viability after a direct lethal heat shock at 50°C. When Hsp104 was overexpressed in wild-type or hsp104Δ cells, the cells became thermotolerant. Remarkably, overexpressed Hsp104 could not provide thermotolerance to ssd1Δ cells. Immunoblotting for Hsp104 showed that Hsp104 was indeed overexpressed in all cells as expected (Fig. 6C). The complete lack of thermotolerance in ssd1Δ cells overexpressing Hsp104 suggests that the pretreatment did not play a role in the Ssd1-mediated regulation of Hsp104 function. We further examined whether Hsp104 overexpression in these cells restored protein disaggregation by monitoring FFL reactivation after a nonlethal heat shock (Fig. 6D). Hsp104 overexpression had a marginal effect on the efficient reactivation by wild-type cells. The low levels of FFL reactivation observed in hsp104Δ cells was increased four- to fivefold by Hsp104 overexpression. In ssd1Δ cells, the low level of FFL reactivation was unaffected by Hsp104 overexpression. These results suggest that Hsp104 became nonfunctional in ssd1Δ cells.

Mechanism of Ssd1-mediated regulation of Hsp104 function.

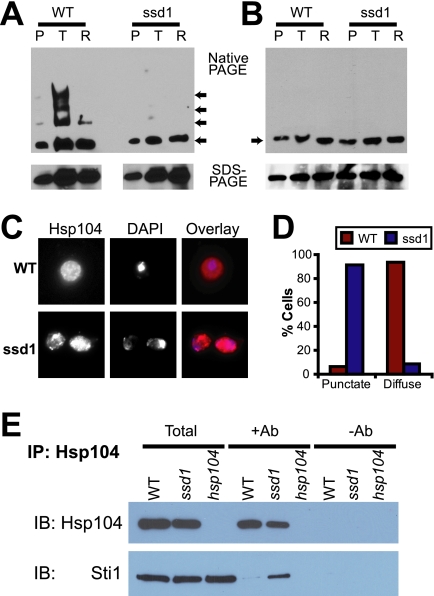

To understand the mechanism by which Ssd1 influences Hsp104 function, we tested whether Ssd1 modulated the hexamerization of Hsp104 or the binding of aggregated proteins. To accomplish this task, we prepared native lysates from cells after (i) a pretreatment (37°C for 30 min) to allow the expression of Hsp104 along with various other heat shock proteins; (ii) a nonlethal heat shock following the pretreatment (37°C for 30 min and 46°C for 30 min) to allow protein aggregation; and (iii) a recovery time following the heat shock (37°C for 30 min, 46°C for 30 min, and 30°C for 60 min) to allow Hsp104-mediated protein disaggregation. These lysates, prepared from wild-type or ssd1Δ cells, were subjected to native PAGE or SDS-PAGE (Fig. 7A), followed by immunoblotting for Hsp104. The amount of Hsp104 expressed, as indicated by SDS-PAGE, was similar in both wild-type and ssd1Δ cells (as previously observed in Fig. 2C). A surprising effect in Hsp104 mobility on native PAGE was observed, namely an upward mobility shift of Hsp104 that indicated that higher-order complexes observed immediately after the nonlethal heat shock in wild-type cells were absent in ssd1Δ cells. Interestingly, the Hsp104 mobility shift was reversed after the recovery time even in wild-type cells, suggesting that the larger assemblies of Hsp104 were not maintained after disaggregation. The upward mobility shift of Hsp104 in native gels may signify Hsp104 oligomerization in vivo or its ability to recognize aggregated proteins as substrates.

FIG. 7.

Ssd1 regulates Hsp104 function. (A and B) Native lysates prepared from wild-type (WT) or ssd1Δ cells after pretreatment (P), after treatment with the nonlethal heat shock (T), or after recovery for 1 h at 30°C (R) were analyzed by native PAGE (top) or by SDS-PAGE (bottom). The arrows in the top panel show the positions of Hsp104 migration on the native gels. Samples were prepared in the absence (A) or presence (B) of orthovanadate. (C) Differences between wild-type and ssd1Δ cells after nonlethal heat shock (37°C for 30 min and 46°C for 30 min) in Hsp104 localization were examined by immunofluorescence microscopy. (D) Cells in seven to eight independent microscopic fields (approximately 100 cells) were scored for the presence of a punctate or diffuse pattern of Hsp104. (E) Coimmunoprecipitation of Hsp104 with Sti1. Samples are total lysates (Total) and immunoprecipitation (IP) samples in the presence (Ab+) or absence (Ab−) of the Hsp104 monoclonal antibody (2B) from wild-type (WT), ssd1Δ, or hsp104Δ cells. Lysates were prepared from cells treated with nonlethal heat shock (37°C for 30 min and 46°C for 30 min). The samples were immunoblotted (IB) for Hsp104 or Sti1.

Binding, hydrolysis, and release cycles of ATP/ADP by Hsp104 are crucial for its hexamerization, substrate binding, and remodeling of aggregated substrates (8, 27). Phosphatase inhibitors such as orthovanadate displace the bound nucleotide and thereby destabilize the hexamers and the substrate complexes. If the upward mobility shift of Hsp104 observed on native gels in wild-type lysates is reminiscent of stable hexamers or substrate complexes, then orthovanadate is expected to abolish these functions. When lysates prepared in the presence of orthovanadate were separated on native gels, Hsp104 from the wild-type cells showed a single band at the same level as that in ssd1Δ cells (Fig. 7B). These results indicate that the biological activity of Hsp104, but not its expression, was significantly affected in ssd1Δ cells.

We next examined whether the in vivo distribution of Hsp104 was defective in ssd1Δ cells. Wild-type and ssd1Δ cells were given a pretreatment followed by a nonlethal heat shock to generate aggregates, but the aggregates were not allowed to recover. Disaggregation was prevented by fixing the cells immediately after heat shock. Hsp104 was visualized by immunofluorescence microscopy (Fig. 7C and D). In about 94% of wild-type cells, Hsp104 appeared diffuse. However, in about 91% of ssd1Δ cells, Hsp104 was observed in a punctate pattern. These results suggest that Hsp104 has a different on/off cycle of binding to aggregates in ssd1Δ cells than that in wild-type cells.

To examine the possible reasons for this difference in the structure and function of Hsp104 in cells lacking Ssd1Δ, we examined the binding of cochaperones to Hsp104 after the heat shock. The only known cochaperones conclusively shown to stably bind Hsp104 are the tetratricopeptide repeat-containing cochaperones of Hsp90 (1). We examined the assembly of Hsp104 with one such tetratricopeptide repeat protein, Sti1, by coimmunoprecipitation studies (Fig. 7E). The immunoprecipitation of Hsp104 was carried out immediately after heat shock (the same conditions that induce a difference in the mobility of Hsp104 between wild-type and ssd1Δ cells). The immunoprecipitated Hsp104 was immunoblotted for Hsp104 to confirm the presence of equal amounts of Hsp104. The immunoprecipitation produced a stoichiometric pulldown of Hsp104 from the lysates, while no Hsp104 adhered to the beads in the absence of antibody. When the same samples were immunoblotted for Sti1, no Sti1-specific bands were obvious in samples prepared without antibody. In samples that specifically pulled down Hsp104, a dramatic difference between wild-type and ssd1Δ cells was apparent: while the Sti1-specific band was thin in wild-type samples, it was prominent in ssd1Δ samples. These results suggest that in ssd1Δ cells, Hsp104 is engaged in a complex different from that of wild-type cells.

DISCUSSION

To understand the importance of protein aggregation and disaggregation in cell survival, we phenotypically screened 4,786 single-gene deletion strains for their ability to recover after a lethal heat stress. When deleted, 38 genes (hits) caused a severe to mild reduction in thermotolerance (unpublished data). After an extensive analysis of these genes in relation to protein disaggregation, we found that Ssd1, a protein that was previously known to play a role in cell wall integrity, also influences the function of Hsp104.

Cellular integrity pathway.

The yeast cell wall is an essential structure for the maintenance of cellular integrity and shape. The remodeling of the cell wall in response to environmental stresses as well as during the cell cycle is essential for survival (25). This remodeling, known as the cellular integrity pathway, is brought about by coordinated transcriptional reprogramming via the mitogen-activated protein kinase (MAPK) Slt2, which in turn is regulated by the protein kinase C (PKC) Pkc1. The MAPK cascade leads to transcriptional activation through the Rlm1 and Swi4 transcription factors, leading to the expression of genes required for cell wall remodeling. Recent evidence indicates that a PKC-independent parallel pathway mediated by SSD1 also ensures cell integrity (20).

Ssd1 protein is highly conserved among fungi and contains an RNB domain (Pfam no. 00773), which is the catalytic domain of 3′ to 5′ exoribonuclease II. The RNB domain is reminiscent of the exosome complex protein Dis3/Rrp44 that is involved in RNA processing and degradation. SSD1 has a confounding set of genetic properties. It has been shown to genetically suppress or rescue mutations in genes involved in signaling pathways mediated by PKA (42), PKC (5), and TORC1 (34). Mutations in SSD1 also are synthetically lethal, with mutations in the GimC/prefoldin chaperones (two of the prefoldins, Yke2 and Pac10, were found to have reduced thermotolerance in our screen) (3, 47). These observations by various laboratories suggest that Ssd1 functions as a molecular signal integrator to collate signals from various pathways to ensure the survival of healthy cells only. Here, we have identified one arm of such a mechanism in which cell wall remodeling is linked to protein disaggregation. Heat shock triggers the remodeling of the yeast cell wall (17), but the importance of the cellular integrity pathway in thermotolerance was hitherto unknown. While the PKC-mediated cellular integrity pathway was unrepresented in our screen results, Ssd1-mediated cellular integrity may play a role in cell wall remodeling during the acquisition of thermotolerance. It is likely that Ssd1 integrates signals from cellular integrity pathways to regulate Hsp104-mediated disaggregation to ensure the survival of cells with minimal damage.

SSD1 polymorphism.

Polymorphic variants of SSD1 are known to differentially influence cellular integrity (20), longevity (19), and pathogenicity (52). The SSD1-V allele provided greater thermotolerance than the ssd1-d allele, which produces a truncated protein lacking the RNB domain. But the fact that ssd1-d restores thermotolerance to ssd1Δ cells affirms that the truncated protein was not dysfunctional, as presumed earlier (19, 20). Further, the truncated Ssd1 protein fully restored Hsp104-mediated protein disaggregation, indicating that the RNB domain was not required for this function. The polymorphism in SSD1 may be centrally responsible for differences in acquired thermotolerance between laboratory strains. Since most studies have focused on the full-length (Ssd1-V) and the C-terminally truncated (Ssd1-d) forms of Ssd1, it is unclear whether the N-terminal domain of Ssd1 is required for cellular integrity. We have shown that while Ssd1-V supports cell wall integrity (resistance to CFW) in untreated or heat-shocked cells, Ssd1-d supports cell wall integrity only in heat-shocked cells (Fig. 4D). Whether the heat shock dependence of Ssd1-d function is dependent on Hsp104 function remains to be tested. These results show that after heat shock, the ssd1-d allele was functional and the RNB domain was not required for cell integrity after heat shock. These results also indicate that the N-terminal region and the RNB domains participate in distinct functions.

How does Ssd1 influence Hsp104 function?

The relationship between SSD1 and HSP104 is quite intriguing. Ssd1 overexpression cannot suppress the thermotolerance and disaggregation deficiencies in hsp104Δ cells, and Hsp104 overexpression cannot suppress the thermotolerance and disaggregation deficiencies in ssd1Δ cells. Since hsp104Δ cells are insensitive to Zymolyase or CFW, cellular integrity is not dependent on Hsp104 or on protein disaggregation. However, the conclusive determination of whether Hsp104 influences Ssd1 function requires the deciphering of Ssd1 function. On the other hand, Ssd1 is clearly required for Hsp104 to function efficiently. Whether Ssd1 elicits its effects on Hsp104 by direct physical interaction has remained unanswered despite our best efforts (unpublished observations). We have examined several possibilities by which such regulation may be brought about by indirect means.

(i) Ssd1 may regulate posttranslational modification(s) on Hsp104.

Since Ssd1 plays a role in many signaling pathways, it is likely that the loss of Ssd1 results in a change in the posttranslational modifications on Hsp104. When we tested for posttranslational modifications (phosphorylation and acetylation) of immunoprecipitated Hsp104 from heat-treated wild-type and ssd1Δ cells, no modifications were obvious (data not shown).

(ii) Ssd1 may influence the subcellular localization of Hsp104.

The nuclear localization of Hsp104 has been observed previously (44). If the level of Hsp104 in the cytoplasm compared to that in the nucleus decreases, then disaggregation in the cytoplasm is expected to be lower. We have observed that Hsp104 was mostly cytoplasmic, with a small amount in the nucleus in both wild-type and ssd1Δ cells. No dramatic differences in the nuclear localization of Hsp104 between wild-type and ssd1Δ cells were seen (Fig. 7C and unpublished observations), thus precluding the possibility that Ssd1 influences the localization of Hsp104.

(iii) Ssd1 may regulate the expression of other chaperones or cofactors.

Due to the presence of an RNase domain in Ssd1, others have suggested that it may participate in translational control by controlling mRNA stability (49). The possibility that Ssd1 controls Hsp104 function by regulating the expression of an unknown cofactor for Hsp104 needs to be examined. When we compared two-dimensional gel profiles of proteins from heat-shocked wild-type and ssd1Δ cells, certain glycolytic enzymes were upregulated in ssd1Δ cells (unpublished observations). Since many glycolytic enzymes are found in the yeast cell wall (26, 31), their accumulation in the cytoplasm of ssd1Δ cells may block heat shock-induced cell wall remodeling. In turn, a feedback signal from the cell wall could prematurely terminate Hsp104-mediated disaggregation.

(iv) Ssd1 may influence hexamerization of Hsp104.

Although Hsp104 hexamers are thought to be the functional forms of Hsp104, the oligomeric status of Hsp104 in vivo and how it is influenced by other proteins is unknown. Our results demonstrate for the first time that the oligomeric status of Hsp104 can be dynamic and may be influenced by Ssd1 (Fig. 7A). At this early stage it is unclear whether Ssd1 has a direct or an indirect effect on Hsp104 oligomerization.

(v) Ssd1 may promote efficient binding and release of Hsp104 from protein aggregates.

Efficient chaperoning of aggregates necessitates several binding and release cycles. Thus, a substrate-bound state of Hsp104 is not very stable. We have observed that Hsp104 localizes to puncta in heat-shocked ssd1Δ cells but not to those in wild-type cells (Fig. 7C). When similar experiments were done in cells expressing FFL-GFP, many of these puncta colocalized with the GFP fluorescent puncta (data not shown). This suggests that in ssd1Δ cells, Hsp104 was not efficiently released from aggregates after binding and thereby affected the processivity (cycling) of the chaperone.

(vi) Ssd1 may modulate the binding of cofactor(s) to Hsp104.

We have observed that one cochaperone, Sti1, binds to Hsp104 strongly in the absence of Ssd1 (Fig. 7E). It is possible that Sti1 preferentially binds to monomeric Hsp104 found in ssd1Δ cells, such that it prevents the hexamerization of Hsp104 necessary for disaggregation.

In summary, our results demonstrate that in the absence of Ssd1, Hsp104 fails to assemble into a disaggregation-competent state (possibly hexamers), Hsp104 remains in distinct puncta, and Sti1 is strongly associated with Hsp104. Taken together, these data suggest that cycling between hexameric and Sti1-bound states (monomeric?) regulates disaggregation in vivo. The punctate localization of Hsp104 in ssd1Δ cells in which hexamerization was affected suggests that monomeric Hsp104 is capable of binding aggregated substrates but remains in a disaggregation-incompetent state. These studies with ssd1Δ cells have illuminated a potential Sti1-stabilized monomer-to-hexamer cycling for Hsp104 that may normally regulate the disaggregation by Hsp104. Further studies are required to confirm these ideas.

Generality of the Ssd1-Hsp104 relationship.

Hsp104 function is critical for the maintenance of prions in yeast. The Hsp104-mediated segregation of Sup35 aggregates has been shown to be important in the epigenetic inheritance of self-replicative prions in yeast (38, 40). We find that the loss of Ssd1 does not significantly affect the maintenance of the [PSI+] prion, suggesting that there were physiological limits to the influence of Ssd1 on Hsp104 function. In our study, this physiological limit is set by the heat shock, which triggers extensive protein aggregation and cell wall remodeling.

Recent evidence showed that Hsp104 was essential for Sir2-dependent longevity regulation and played a major role in the asymmetric segregation of carbonyl-damaged protein aggregates between mother and daughter cells (9). The heat shock-mediated overexpression of Hsp104 previously was known to extend the life span of yeast (39). These studies suggest that aggregation surveillance by Hsp104 ensures, in general, cellular health and life span. Given our observations showing the effects of Ssd1 on Hsp104 function, it is possible that the SSD1-dependent pathway to longevity (19) also involves Hsp104 function.

Further work is required to more deeply understand the intricacies of the cell integrity pathways and its impact on the Ssd1-mediated regulation of Hsp104 function.

Acknowledgments

We thank Sue Lindquist for various strains, plasmids, and antibodies; John Glover and Ted Powers for plasmids; Charlie Boone for strains; Betty Craig, Johannes Buchner, Doug Cyr, David Toft, Olga Kandror, Brooke Bevis, and Martin Haslbeck for antibodies; and Cara Trammell and Rajalakshmi for technical help.

This work was supported by laboratory start-up funds from the Medical College of Georgia.

Footnotes

Published ahead of print on 20 October 2008.

REFERENCES

- 1.Abbas-Terki, T., O. Donze, P. A. Briand, and D. Picard. 2001. Hsp104 interacts with Hsp90 cochaperones in respiring yeast. Mol. Cell. Biol. 217569-7575. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Cashikar, A. G., E. C. Schirmer, D. A. Hattendorf, J. R. Glover, M. S. Ramakrishnan, D. M. Ware, and S. L. Lindquist. 2002. Defining a pathway of communication from the C-terminal peptide binding domain to the N-terminal ATPase domain in a AAA protein. Mol. Cell 9751-760. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Collins, S. R., K. M. Miller, N. L. Maas, A. Roguev, J. Fillingham, C. S. Chu, M. Schuldiner, M. Gebbia, J. Recht, M. Shales, H. Ding, H. Xu, J. Han, K. Ingvarsdottir, B. Cheng, B. Andrews, C. Boone, S. L. Berger, P. Hieter, Z. Zhang, G. W. Brown, C. J. Ingles, A. Emili, C. D. Allis, D. P. Toczyski, J. S. Weissman, J. F. Greenblatt, and N. J. Krogan. 2007. Functional dissection of protein complexes involved in yeast chromosome biology using a genetic interaction map. Nature 446806-810. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Cooper, A. A., A. D. Gitler, A. Cashikar, C. M. Haynes, K. J. Hill, B. Bhullar, K. Liu, K. Xu, K. E. Strathearn, F. Liu, S. Cao, K. A. Caldwell, G. A. Caldwell, G. Marsischky, R. D. Kolodner, J. Labaer, J. C. Rochet, N. M. Bonini, and S. Lindquist. 2006. Alpha-synuclein blocks ER-Golgi traffic and Rab1 rescues neuron loss in Parkinson's models. Science 313324-328. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Costigan, C., S. Gehrung, and M. Snyder. 1992. A synthetic lethal screen identifies SLK1, a novel protein kinase homolog implicated in yeast cell morphogenesis and cell growth. Mol. Cell. Biol. 121162-1178. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.De Virgilio, C., T. Hottiger, J. Dominguez, T. Boller, and A. Wiemken. 1994. The role of trehalose synthesis for the acquisition of thermotolerance in yeast. I. Genetic evidence that trehalose is a thermoprotectant. Eur. J. Biochem. 219179-186. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Doseff, A. I., and K. T. Arndt. 1995. LAS1 is an essential nuclear protein involved in cell morphogenesis and cell surface growth. Genetics 141857-871. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Doyle, S. M., J. Shorter, M. Zolkiewski, J. R. Hoskins, S. Lindquist, and S. Wickner. 2007. Asymmetric deceleration of ClpB or Hsp104 ATPase activity unleashes protein-remodeling activity. Nat. Struct. Mol. Biol. 14114-122. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Erjavec, N., L. Larsson, J. Grantham, and T. Nystrom. 2007. Accelerated aging and failure to segregate damaged proteins in Sir2 mutants can be suppressed by overproducing the protein aggregation-remodeling factor Hsp104p. Genes Dev. 212410-2421. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Geitz, K. A., D. W. Richter, and A. Gottschalk. 1995. The influence of chemical and mechanical feedback on ventilatory pattern in a model of the central respiratory pattern generator. Adv. Exp. Med. Biol. 39323-28. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Glover, J. R., and S. Lindquist. 1998. Hsp104, Hsp70, and Hsp40: a novel chaperone system that rescues previously aggregated proteins. Cell 9473-82. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Goldstein, A. L., and J. H. McCusker. 1999. Three new dominant drug resistance cassettes for gene disruption in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Yeast 151541-1553. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Gross, C., and K. Watson. 1998. Transcriptional and translational regulation of major heat shock proteins and patterns of trehalose mobilization during hyperthermic recovery in repressed and derepressed Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Can. J. Microbiol. 44341-350. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Haass, C., and D. J. Selkoe. 2007. Soluble protein oligomers in neurodegeneration: lessons from the Alzheimer's amyloid beta-peptide. Nat. Rev. 8101-112. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Haslberger, T., J. Weibezahn, R. Zahn, S. Lee, F. T. Tsai, B. Bukau, and A. Mogk. 2007. M domains couple the ClpB threading motor with the DnaK chaperone activity. Mol. Cell 25247-260. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hubel, A., S. Krobitsch, A. Horauf, and J. Clos. 1997. Leishmania major Hsp100 is required chiefly in the mammalian stage of the parasite. Mol. Cell. Biol. 175987-5995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Imazu, H., and H. Sakurai. 2005. Saccharomyces cerevisiae heat shock transcription factor regulates cell wall remodeling in response to heat shock. Eukaryot. Cell 41050-1056. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Jorgensen, P., B. Nelson, M. D. Robinson, Y. Chen, B. Andrews, M. Tyers, and C. Boone. 2002. High-resolution genetic mapping with ordered arrays of Saccharomyces cerevisiae deletion mutants. Genetics 1621091-1099. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kaeberlein, M., A. A. Andalis, G. B. Liszt, G. R. Fink, and L. Guarente. 2004. Saccharomyces cerevisiae SSD1-V confers longevity by a Sir2p-independent mechanism. Genetics 1661661-1672. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kaeberlein, M., and L. Guarente. 2002. Saccharomyces cerevisiae MPT5 and SSD1 function in parallel pathways to promote cell wall integrity. Genetics 16083-95. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kienle, I., M. Burgert, and H. Holzer. 1993. Assay of trehalose with acid trehalase purified from Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Yeast 9607-611. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kotak, S., J. Larkindale, U. Lee, P. von Koskull-Doring, E. Vierling, and K. D. Scharf. 2007. Complexity of the heat stress response in plants. Curr. Opin. Plant Biol. 10310-316. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kültz, D. 2005. Molecular and evolutionary basis of the cellular stress response. Annu. Rev. Physiol. 67225-257. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Landry, J., D. Bernier, P. Chretien, L. M. Nicole, R. M. Tanguay, and N. Marceau. 1982. Synthesis and degradation of heat shock proteins during development and decay of thermotolerance. Cancer Res. 422457-2461. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Lesage, G., and H. Bussey. 2006. Cell wall assembly in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Microbiol. Mol. Biol. Rev. 70317-343. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.López-Villar, E., L. Monteoliva, M. R. Larsen, E. Sachon, M. Shabaz, M. Pardo, J. Pla, C. Gil, P. Roepstorff, and C. Nombela. 2006. Genetic and proteomic evidences support the localization of yeast enolase in the cell surface. Proteomics 6(Suppl. 1)S107-S118. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Lum, R., J. M. Tkach, E. Vierling, and J. R. Glover. 2004. Evidence for an unfolding/threading mechanism for protein disaggregation by Saccharomyces cerevisiae Hsp104. J. Biol. Chem. 27929139-29146. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Lussier, M., A. M. White, J. Sheraton, T. di Paolo, J. Treadwell, S. B. Southard, C. I. Horenstein, J. Chen-Weiner, A. F. Ram, J. C. Kapteyn, T. W. Roemer, D. H. Vo, D. C. Bondoc, J. Hall, W. W. Zhong, A. M. Sdicu, J. Davies, F. M. Klis, P. W. Robbins, and H. Bussey. 1997. Large scale identification of genes involved in cell surface biosynthesis and architecture in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Genetics 147435-450. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Mogk, A., T. Tomoyasu, P. Goloubinoff, S. Rudiger, D. Roder, H. Langen, and B. Bukau. 1999. Identification of thermolabile Escherichia coli proteins: prevention and reversion of aggregation by DnaK and ClpB. EMBO J. 186934-6949. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Morano, K. A., P. C. Liu, and D. J. Thiele. 1998. Protein chaperones and the heat shock response in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Curr. Opin. Microbiol. 1197-203. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Pardo, M., M. Ward, S. Bains, M. Molina, W. Blackstock, C. Gil, and C. Nombela. 2000. A proteomic approach for the study of Saccharomyces cerevisiae cell wall biogenesis. Electrophoresis 213396-3410. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Parsell, D. A., A. S. Kowal, M. A. Singer, and S. Lindquist. 1994. Protein disaggregation mediated by heat-shock protein Hsp104. Nature 372475-478. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Piper, P. W. 1993. Molecular events associated with acquisition of heat tolerance by the yeast Saccharomyces cerevisiae. FEMS Microbiol. Rev. 11339-355. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Reinke, A., S. Anderson, J. M. McCaffery, J. Yates III, S. Aronova, S. Chu, S. Fairclough, C. Iverson, K. P. Wedaman, and T. Powers. 2004. TOR complex 1 includes a novel component, Tco89p (YPL180w), and cooperates with Ssd1p to maintain cellular integrity in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. J. Biol. Chem. 27914752-14762. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Sanchez, Y., and S. L. Lindquist. 1990. HSP104 required for induced thermotolerance. Science 2481112-1115. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Sanchez, Y., J. Taulien, K. A. Borkovich, and S. Lindquist. 1992. Hsp104 is required for tolerance to many forms of stress. EMBO J. 112357-2364. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Sass, P., J. Field, J. Nikawa, T. Toda, and M. Wigler. 1986. Cloning and characterization of the high-affinity cAMP phosphodiesterase of Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 839303-9307. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Satpute-Krishnan, P., S. X. Langseth, and T. R. Serio. 2007. Hsp104-dependent remodeling of prion complexes mediates protein-only inheritance. PLoS Biol. 5e24. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Shama, S., C. Y. Lai, J. M. Antoniazzi, J. C. Jiang, and S. M. Jazwinski. 1998. Heat stress-induced life span extension in yeast. Exp. Cell Res. 245379-388. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Shorter, J., and S. Lindquist. 2005. Prions as adaptive conduits of memory and inheritance. Nat. Rev. 6435-450. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Singer, M. A., and S. Lindquist. 1998. Thermotolerance in Saccharomyces cerevisiae: the Yin and Yang of trehalose. Trends Biotechnol. 16460-468. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Sutton, A., D. Immanuel, and K. T. Arndt. 1991. The SIT4 protein phosphatase functions in late G1 for progression into S phase. Mol. Cell. Biol. 112133-2148. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Tanaka, K., M. Nakafuku, F. Tamanoi, Y. Kaziro, K. Matsumoto, and A. Toh-e. 1990. IRA2, a second gene of Saccharomyces cerevisiae that encodes a protein with a domain homologous to mammalian ras GTPase-activating protein. Mol. Cell. Biol. 104303-4313. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Tkach, J. M., and J. R. Glover. 2008. Nucleocytoplasmic trafficking of the molecular chaperone Hsp104 in unstressed and heat-shocked cells. Traffic 939-56. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Tong, A. H., and C. Boone. 2007. High-throughput strain construction and systematic synthetic lethal screening in Saccharomyces cerevisiae, p. 369-386, Yeast gene analysis, 2nd ed., vol. 36. Elsevier Ltd., New York, NY. [Google Scholar]

- 46.Tong, A. H., and C. Boone. 2006. Synthetic genetic array analysis in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Methods Mol. Biol. 313171-192. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Tong, A. H., G. Lesage, G. D. Bader, H. Ding, H. Xu, X. Xin, J. Young, G. F. Berriz, R. L. Brost, M. Chang, Y. Chen, X. Cheng, G. Chua, H. Friesen, D. S. Goldberg, J. Haynes, C. Humphries, G. He, S. Hussein, L. Ke, N. Krogan, Z. Li, J. N. Levinson, H. Lu, P. Menard, C. Munyana, A. B. Parsons, O. Ryan, R. Tonikian, T. Roberts, A. M. Sdicu, J. Shapiro, B. Sheikh, B. Suter, S. L. Wong, L. V. Zhang, H. Zhu, C. G. Burd, S. Munro, C. Sander, J. Rine, J. Greenblatt, M. Peter, A. Bretscher, G. Bell, F. P. Roth, G. W. Brown, B. Andrews, H. Bussey, and C. Boone. 2004. Global mapping of the yeast genetic interaction network. Science 303808-813. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Trent, J. D. 1996. A review of acquired thermotolerance, heat-shock proteins, and molecular chaperones in archaea. FEMS Microbiol. Rev. 18249-258. [Google Scholar]

- 49.Uesono, Y., A. Toh-e, and Y. Kikuchi. 1997. Ssd1p of Saccharomyces cerevisiae associates with RNA. J. Biol. Chem. 27216103-16109. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Wach, A., A. Brachat, R. Pohlmann, and P. Philippsen. 1994. New heterologous modules for classical or PCR-based gene disruptions in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Yeast 101793-1808. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]