Abstract

Gene alterations in tumor cells that confer the ability to grow under nutrient- and mitogen-deficient conditions constitute a competitive advantage that leads to more-aggressive forms of cancer. The atypical protein kinase C (PKC) isoform, PKCζ, has been shown to interact with the signaling adapter p62, which is important for Ras-induced lung carcinogenesis. Here we show that PKCζ-deficient mice display increased Ras-induced lung carcinogenesis, suggesting a new role for this kinase as a tumor suppressor in vivo. We also show that Ras-transformed PKCζ-deficient lungs and embryo fibroblasts produced more interleukin-6 (IL-6), which we demonstrate here plays an essential role in the ability of Ras-transformed cells to grow under nutrient-deprived conditions in vitro and in a mouse xenograft system in vivo. We also show that PKCζ represses histone acetylation at the C/EBPβ element in the IL-6 promoter. Therefore, PKCζ, by controlling the production of IL-6, is a critical signaling molecule in tumorigenesis.

Tumorigenesis relies on sequential mutations in genes required for the control of cell proliferation and survival. These mutations confer the loss of tumor suppressor function and the gain of proto-oncogene activity (17). The affected genes code for critical intermediaries in the signaling processes that regulate cell growth and death. As tumors grow in size, access to nutrients becomes more restricted for cancer cells until an angiogenic response is triggered by the transformed cell, which serves to restore a more normal supply of nutrients and mitogens. In this scenario, it is logical to assume that genetic and biochemical changes that confer on the tumor cell capabilities to grow under conditions of nutrient deprivation will promote tumor development. Therefore, a combination of increased mitogenicity, decreased apoptosis, and enhanced resistance to metabolic stress controls the ability of tumors to progress.

The signaling pathways relevant to cell proliferation include those that culminate in activation of inflammatory signals, which can play important roles as antiapoptotic and progrowth molecules (18, 23). In this regard, interleukin-6 (IL-6) has emerged as an essential positive regulator of growth in a number of human tumors, including liver and lung tumors, owing to its ability to control epithelial cell proliferation (14). Our recent data demonstrate that the atypical protein kinase C (PKC) (aPKC) signaling adapter p62 is required for lung carcinogenesis through its ability to activate the NF-κB inflammatory and survival pathway (9). p62 binds the aPKC isoform PKCζ (25, 32). This kinase has been implicated in the regulation of NF-κB and suggested to be relevant for Ras-induced oncogenesis in cotransfection and overexpression experiments (5, 7). Also, recent evidence links PKCζ to human cancer (19, 30, 34). However, as yet there has been no report of an in vivo test, at the organismal level, of the role of PKCζ in cancer.

Among the proto-oncogenes most frequently altered in human tumors are the small GTPases of the Ras family, which have been found to be mutated in at least 25% of human lung adenocarcinomas (6). Mouse lung cancer models that faithfully reproduce the human disease are available, thus allowing the study of the cellular and molecular basis of this neoplasia at the organismal level (11, 24). Here we show that the loss of PKCζ in vivo leads to increased tumorigenicity due to overproduction of IL-6. Therefore, PKCζ can be considered a novel tumor suppressor thanks to its ability to repress chromatin modification at the level of the C/EBPβ element in the IL-6 promoter.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Mice.

The PKCζ−/−, CCSP-rtTA, and K-Ras (Tet-op-K-RasG12D) mice were described previously (11, 21). All mice were born and kept under pathogen-free conditions. Animal handling and experimental procedures conformed to institutional guidelines (University of Cincinnati Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee). All genotyping was done by PCR. Doxycycline was administered at a concentration of 500 mg/liter via drinking water freshly prepared twice a week. For the in vivo tumor growth assays, cell suspensions (8 × 105) were injected intradermally into each flank of female athymic 4- to 6-week-old nu/nu mice.

Reagents and antibodies.

Reagents were purchased as follows: doxycycline and polybrene were from Sigma, and recombinant murine IL-6 was from R&D. Anti-Ki67 (clone sp6) and anti-CD31 were from Lab Vision Corporation; anti-PKCζ, anti-pSTAT3(Tyr 705) clone D3A7, and anti-VEGF receptor 2 (KDR) clone 55B11 were from Cell Signaling Technology; antiactin (I-19), anti-cyclin D1 (A-12), anti-hemagglutinin (HA) (12CA5), and anti-p65 (C-20) were from Santa Cruz Biotechnology; anti-caspase-3 active and anti-IL-6 were from R&D Systems, and anti-pan-Ras(Ab-3) was from Calbiochem. All antibodies were used according to manufacturers' instructions.

Histological analysis.

Lungs were inflated, excised, and fixed in 10% neutral buffered formalin for 24 h, dehydrated, and embedded in paraffin. Sections (5 μm) were cut and stained with hematoxylin and eosin (H&E). The overall tumor burden was quantitated by measuring the tumor area in H&E-stained sections using the NIH software program ImageJ (version 1.38; http://rsb.info.nih.gov/ij/). For immunohistochemistry, sections were deparaffinized and rehydrated, and antigen retrieval was performed by boiling for 10 min in 10 mM citric acid-2 mM EDTA (pH 6.2). After quenching of endogenous peroxidase and blocking in normal serum, tissues were incubated with primary antibody overnight at 4°C, followed by incubation with biotinylated secondary antibody. Antibodies were visualized with avidin-biotin complex (Vectastain Elite; Vector Labs) using diaminobenzidine as the chromogen. Slides were then counterstained with hematoxylin, dehydrated, and mounted. The intratumoral microvessel density was evaluated using a 25-point Chalkley eyepiece graticule on CD31-immunostained paraffin sections.

Cell culture.

Wild-type (WT) and PKCζ−/− primary embryo fibroblasts (EFs) were derived from E13.5 embryos (13). Cells were maintained in Dulbecco's modified Eagle medium (DMEM) (Gibco BRL) supplemented with 10% (vol/vol) fetal calf serum (FCS), 1% glutamine, and 1% penicillin-streptomycin (Gibco-Invitrogen) in an atmosphere of 95% air and 5% CO2 and immortalized by retroviral infection with pBabeT-Ag followed by puromycin selection (1 μg/ml). The established cell lines represent pools of at least 100 independent clones. The HEK293-derived virus-packaging 293T cells were cultured in DMEM with 10% FCS. Reporter κB assays were performed as described previously (32) using Renilla luciferase to normalize transfection efficiency. Transfection of EFs for IL-6 promoter reporter assays was performed by Fugene, following the manufacturers' instructions. IL-6 promoter luciferase constructs, both WT and mutant, were from William L. Farrar (NIH).

Retroviral and lentiviral transduction.

The following retroviral expression vectors were used: pWZL-Hygro-H-RasV12 and pBabe-large-T-Ag (4) and pWZL-Hygro-HA-PKCζ and pWZL-Hygro-HA-PKCζK281R. Retroviruses were produced in 293T cells by transient transfection using Lipofectamine 2000 (Invitrogen). Culture supernatants were collected 24 h, 48 h, and 72 h posttransfection, filtered (0.45 μm), and then supplemented with 4 μg/ml polybrene. EFs and A549 cells were infected with three rounds of viral supernatants and selected with hygromycin (75 μg/ml), as appropriate. Lentivirus for IL-6 was produced by the Viral Vector Core at the Translational Core Laboratories, Cincinnati Children's Hospital Research Foundation (Cincinnati, OH).

Soft-agar assays.

To determine the ability of cells to grow in soft agar, 2 × 104 cells were suspended in 0.3% agar in DMEM plus 10% FCS and overlaid on 0.5% agar in the same medium. Cells were refed with 10% FCS-containing medium every 5 days.

Western blots.

Cell extracts for Western blotting were prepared in radioimmunoprecipitation assay buffer (1× phosphate-buffered saline, 1% Nonidet P-40, 0.5% sodium deoxycholate, 0.1% sodium dodecyl sulfate [SDS], 1 mM phenylmethylsulfonylfluoride, and protease inhibitors). Lysates were separated by SDS-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis and transferred to nitrocellulose-ECL membranes (GE Healthcare), and the immune complex was detected by chemiluminescence (GE Healthcare).

ChIP.

Chromatin immunoprecipitation (ChIP) was performed using the EZ ChIP kit (Upstate Biotechnology). Precleared chromatin was incubated with 5 μg of specific antibody (C/EBPβ [Santa Cruz catalog no. sc-150], acetyl-histone 4 [Upstate Biotechnology catalog no. 06-866], and HDAC1 [Santa Cruz catalog no. sc-8410]). Quantitative PCR (Q-PCR) was performed using the Mastercycler Realplex EpgradientS system (Eppendorf) and iQ Sybr green supermix (Bio-Rad). Primers for amplification of a C/EBP binding-site-specific, proximal region (nucleotides −205 to −193) within the murine IL-6 promoter were 5′-TCGATGCTAAACGACGTCACA-3′ and 5′-GGGCTGATTGGAAACCTTATTAAGA-3′. For a nonspecific distal IL-6 promoter region (nucleotides −1164 to −1143), primers were 5′-CTAACCAAAGGGAAGAAGT-3′ and 5′-CTCCAATGCTCAAGTCTT-3′. Relative promoter binding is represented as the ratio between the amounts of specific and nonspecific amplified DNA fragments as the mean plus standard deviation of three independent experiments.

Gene expression analysis by Q-PCR.

Total RNA was extracted using the RNeasy purification kit (Qiagen) and DNase treated (RQ1 DNase free; Promega). cDNA was then prepared from total RNA using random primers (Promega) and the Omniscript RT kit (Qiagen). The relative levels of mRNA were determined by real-time quantitative PCR using an Eppendorf Realplex Mastercycler instrument (Eppendorf) and the Quantitect Sybr green PCR kit (Qiagen). 18S mRNA levels were used for normalization. Primer sequences used are as follows: Fhc, TCGTCGTTCCGCCGCTCCA and AGCCACATCATCTCGGTCAAAA; IL-6, TTCCATCCAGTTGCCTTCTTGG and TTCTCATTTCCACGATTTCCCAG; Ras, GGGAATAAGTGTGATTTGCCT and GCCTGCGACGGCGGCATCTGC; 18S, GTAACCCGTTGAACCCCATT and CCATCCAATCGGTAGTAGCG; Vegf-A, GGCTGCTGTAACGATGAAG and CTCCTATGTGCTGGCTTTG; Vegf-C, GCTGGTGTTCATGCACTGCAG and AAAGACTCAATGCATGCCACG; Vegf-R3, CTACAAAGACCCCGACTATG and CACAGCAGCACGCCGAAG; Pecam-1, TCCTTCCTGCTTCTTGCTAGC and AGCCCAATCACGTTTCAGTTT; Mip-2, GGTGGGGGTGGGGACAAAT and CTACTCTCCTCGGTGCTTAC; Kc, TGTGGGAGGCTGTGTTTGTA and CGAGACGAGACCAGGAGAA; IL-1, GTTTTCCTCCTTGCCTCTGA and CTGCCTAATGTCCCCTTGAA; tumor necrosis factor alpha (TNF-α), TGTCTACTCCCAGGTTCTCT and GGGGCAGGGGCTCTTGAC; oncostatin M, CAGGGGTCACACAGAAGAG and TGGGACACAATAACCTCACTA; cardiotrophin 1, CTTCCCACCAGTTCCTTTGT and TCTGCCTTTCTCTCTCCATTG; epidermal growth factor, CGGTGGGGCTTGGAACTT and CAGGCACAACCAGGCAAAG; gp130, CCAGCAACGAGGAGAATGAG and TCGGACCTTGAGAACACTTG; IL-6R, GCCCTTGCTGGTGGATGT and CCGTTGGTGGTGTTGATTTT; IL-11, CTGCACAGATGAGAGACAAATTCC and GAAGCTGCAAAGATCCCAATG; and LIF, CCTTACTGCTGCTGGTTCTG and TTACAGGGGTGATGGGAAGA.

PKCζ kinase assay.

Cell extracts prepared in lysis buffer (Tris-HCl [50 mM; pH 7.5], NaCl [150 mM], EGTA [1 mM], EDTA [2 mM], Triton X-100 [1%]) were immunoprecipitated with anti-HA antibody for 2 h at 4°C. Immunoprecipitates were captured with protein A and washed extensively in lysis buffer with 0.5 M NaCl. The enzymatic assay was carried out in the immunoprecipitates in assay buffer (Tris-HCl [35 mM; pH 7.5], MgCl2 [10 mM], CaCl2 ′100 μM], EGTA [0.5 mM], ATP [100 μM], 5 μCi of [32P]ATP) with 4 μg of myelin basic protein as a substrate for 1 h at 30°C. Afterwards, enzymatic activity in the samples was stopped, and samples were separated via SDS-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis.

RESULTS

Effect of PKCζ loss in Ras-induced lung carcinogenesis.

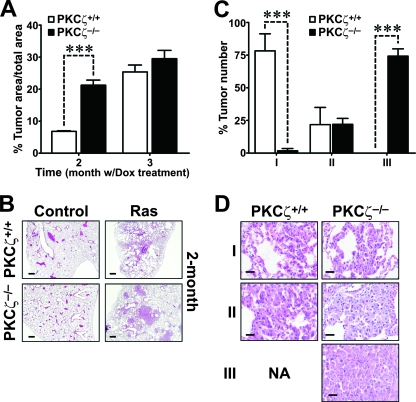

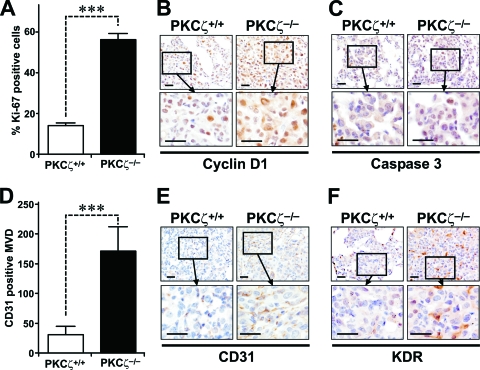

To test the potential role of PKCζ in a physiologically relevant in vivo mouse model of Ras-induced lung adenocarcinoma, we crossed WT and PKCζ−/− mice with bitransgenic mice that develop pulmonary adenocarcinomas as a consequence of the inducible expression of oncogenic Ras in type II alveolar epithelial cells in response to the presence of doxycycline in the diet (11). This is a physiologically relevant model for human cancer, since it has been reported that the likely precursors of lung adenocarcinomas include the type II alveolar epithelial cells and the Clara cells (15, 22, 33). Solid-type adenomas and adenocarcinomas were reproducibly detected when doxycycline was administered for 2 months (Fig. 1A and B), with the tumor area in the WT being close to 10% of the total lung area. Importantly, when this experiment was performed in a PKCζ−/− background, the tumor burden was even higher than in the WT controls, accounting for 30% of the lung area (Fig. 1A and B). After 3 months of Ras induction, the differences between WT and PKCζ−/− tumors were significantly reduced with regard to the tumor area. However, at this time (3 months of treatment), it was apparent that the absence of PKCζ promoted a more severe lung tumor phenotype. To quantify the extent of progression, we scored each tumor on a scale of I to III, with observers blinded to the genotype. The criteria for each grade were as follows. Grade I tumors have uniform nuclei, showing no nuclear atypia. Grade II tumors contain cells with uniform but slightly enlarged nuclei that exhibit prominent nucleoli. Grade III tumor cells have very large, pleomorphic nuclei exhibiting a high degree of nuclear atypia, including abnormal mitoses and hyperchromatism. Interestingly, a large majority of the lung tumors in the PKCζ−/− mice were grade III, whereas tumors from WT mice were grade I (Fig. 1C and D). This indicates that PKCζ plays an unexpected role in restraining lung tumorigenesis and its loss is an important event for lung tumor progression. Consistent with a higher tumor burden in the PKCζ−/− mice, the percentage of Ki-67-positive cells in the WT Ras-expressing lungs was dramatically lower than that in the PKCζ-deficient Ras-expressing lungs (Fig. 2A). Cyclin D1 expression was significantly increased in the Ras-expressing PKCζ−/− lung tumors compared to expression in the corresponding WT tumors (Fig. 2B). There was no difference in caspase-3 activities in the PKCζ−/− Ras lungs compared to those in the corresponding WT lungs (Fig. 2C), suggesting that increased cell proliferation likely accounts for the enhanced tumorigenesis observed in Ras-expressing mutant lungs compared to the identically treated WT lungs. The expression of the angiogenesis marker CD31 was also dramatically enhanced in the tumors from PKCζ−/− mice compared that in to the WT tumors (Fig. 2D and E). That is, staining of lung sections for CD31 confirmed strong induction of intratumoral vessels, as determined as CD31+ microvessel density, indicative of increased neoangiogenesis in the PKCζ-deficient tumors (Fig. 2D and E). This is consistent with enhanced staining of VEGF receptor 2 (KDR) in lung endothelial PKCζ-deficient cells (Fig. 2F).

FIG. 1.

Ras-induced lung tumorigenesis is enhanced in the absence of PKCζ. (A and B) Lung tumor burden of PKCζ+/+ and PKCζ−/− mice expressing the inducible Ras transgene as a result of treatment with doxycycline (Dox) for 2 or 3 months. Representative H&E staining of lung sections (n = 6 per treatment and genotype) is shown. ***, P < 0.001. (C and D) Tumor grades in PKCζ+/+ and PKCζ−/− mice after 3 months' exposure to doxycycline. Representative H&E staining showing the different tumor grades in each genotype is shown. ***, P < 0.001.

FIG. 2.

Ras-induced cell proliferation is enhanced in the absence of PKCζ. (A) Quantitation of Ki-67 staining of samples from grade II lung tumors taken from mice treated with doxycycline for 3 months. ***, P < 0.001. (B) Immunohistochemical analysis of cyclin D1 expression levels in PKCζ+/+ and PKCζ−/− Ras-expressing lung tumors (n = 6 per treatment and genotype; scale bars, 50 μm). (C) Immunohistochemical analysis of activated caspase-3 levels, as in panel B. (D) Quantitation of intratumoral CD31-positive microvessel density. Ten tumor areas (10,000 μm2) were counted (n = 6 per treatment and genotype). ***, P < 0.001. (E) Immunohistochemical analysis of CD31 in lung samples, as in panel B. (F) Immunohistochemical analysis of VEGF receptor 2 (KDR) levels in lung samples, as in panel B.

Immunohistochemical analysis of Ras expression in lungs from WT and PKCζ−/− mice, with or without 3 months of doxycycline treatment, revealed that Ras levels increased to similar extents in the two PKCζ genotypes upon doxycycline treatment (see Fig. S1A in the supplemental material). Q-PCR analysis demonstrated that this was also true at the mRNA level (see Fig. S1B in the supplemental material). Therefore, the increased tumorigenesis observed in the PKCζ-deficient lungs upon exposure to doxycycline cannot be accounted for by differences in Ras expression. The observation that the loss of PKCζ enhances rather than hampers lung tumorigenesis was unexpected based on the p62−/− phenotype (9) and reveals an unanticipated role of PKCζ as a potential tumor suppressor. Interestingly, our analysis of human non-small cell lung carcinoma (n = 49) reveals that PKCζ expression is absent in 12% of the analyzed samples (Fig. S2 in the supplemental material shows examples of PKCζ-positive and -negative tumors).

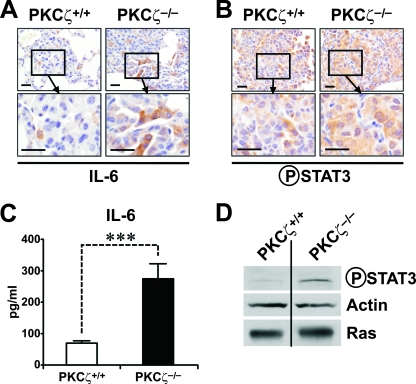

Effect of PKCζ loss in Ras-induced NF-κB gene expression in lung.

Previous genetic evidence from PKCζ−/− mice and EFs demonstrated that PKCζ is required for NF-κB activation at the levels of RelA phosphorylation in response to TNF-α and IL-1 (8, 21). In whole-animal studies, PKCζ ablation severely impairs TNF-α and lipopolysaccharide-induced IKK activation in the lung and the subsequent translocation of NF-κB to the nucleus, indicating that depending on the cell type and tissue, PKCζ is necessary for NF-κB activation at different levels of the pathway (8, 21). To test whether oncogenic Ras expression in the lung leads to NF-κB activation, we determined the ability of Ras to promote the nuclear translocation of p65/RelA to the nucleus in lungs from WT and PKCζ−/− mice that have been exposed to doxycycline for 3 months. Data in Fig. S3A and S3B in the supplemental material demonstrate the lack of significant differences between the two Ras-expressing PKCζ genotypes. These results indicate that in contrast to the PKCζ-dependent induction of NF-κB nuclear translocation by lipopolysaccharide or TNF-α in the lung (8, 21), the ability of oncogenic Ras to produce that effect is PKCζ independent. However, these results do not preclude the requirement of PKCζ for the induction of κB-dependent genes by oncogenic Ras. To address this possibility, we performed Q-PCR analysis of a well-established series of NF-κB-regulated transcripts in lung extracts from WT and PKCζ−/− mice that had been expressing oncogenic Ras for 3 months. Interestingly, there was a significant reduction in the expression of VegfA, VegfC, VegfR3, Fhc, Pecam-1, Mip-2, Kc, and IL-1 (Table 1), consistent with the notion that PKCζ is required for NF-κB-dependent transcriptional activity in oncogenic Ras-expressing lungs. In addition, the expression of critical inflammatory cytokines was analyzed. Interestingly, the induction of IFN-γ, a Th1 cytokine, and that of IL-4, a Th2 cytokine, were increased and decreased, respectively, in the PKCζ-deficient Ras-expressing lungs compared to results with the Ras WT lungs (Table 1). The expression of IL-12p35 and IL-12p40, which are the two chains of the pro-Th1 cytokine IL-12, was likewise increased, whereas that of IL-23p19 was not affected (Table 1). No significant changes were observed in the levels of IL-17A or IL-17F (Table 1). This pattern of cytokines is very interesting because it suggests that the loss of PKCζ leads to an increase in the Th1-like response that would likely provoke a proinflammatory reaction mediated by increased M1 macrophagic activity, which should boost the antitumor actions of the immune system and produce a reduction in the tumor burden in the PKCζ-deficient mice (3, 29). In contrast, what is observed is a higher tumorigenic activity in the lungs of the PKCζ-deficient mice (Fig. 1). Therefore, the M1-like phenotype of the PKCζ-deficient Ras lungs is not sufficient to drive an effective antitumorigenic response. A potential explanation for this apparently paradoxical phenotype can also be found in our analysis of the lung mRNAs in these mice. Thus, surprisingly, we found that the induction of IL-6 mRNA, which depends in part on NF-κB (21), was not reduced but contrary to what we expected was significantly increased in the Ras-expressing PKCζ-deficient lungs compared to results with the Ras-expressing WT lungs (Table 1). Taking into consideration the role played by IL-6 in cell proliferation and tumorigenesis in other systems (1, 12, 14, 28, 31), this observation suggests that enhanced IL-6 production might account for the phenotype of the PKCζ−/− Ras-expressing lungs. Immunohistochemical analysis of tumors from Ras-expressing WT and PKCζ−/− lungs demonstrated that the PKCζ-deficient lung tumors exhibited increased IL-6 protein levels (Fig. 3A), consistent with the mRNA data of Table 1. Interestingly, this enhanced expression of IL-6 in Ras-expressing PKCζ−/− lung tumors correlated with a higher level of Stat3 phosphorylation in these samples (Fig. 3B), consistent with the notion that the IL-6 produced under these conditions is biologically active. Our interpretation of these findings is that pneumocyte transformation activates IL-6 production in lung and this induction is enhanced in the PKCζ−/− mice, which serves to activate Stat3 in the tumor cell environment. Of note, no differences between WT and PKCζ-deficient Ras-expressing lungs in IL-6 staining or Stat3 activation were observed in tumor-adjacent normal lung cells (see Fig. S4 in the supplemental material). Also, no differences between WT and PKCζ-deficient tumors were observed when other IL-6 family members and Stat3 activators were analyzed, including LIF, oncostatin M, IL-11, and cardiotrophin 1, whereas EGF levels were reduced (Table 1). On the other hand, the levels of the two IL-6 receptor subunits, IL-6R and gp130, were not differently expressed between WT and PKCζ−/− tumors at the mRNA (Table 1) or protein level (not shown).

TABLE 1.

Role of PKCζ in Ras-induced lung gene expression

| Gene | Expression in lung cells with phenotypea

|

P valueb | |

|---|---|---|---|

| WT | PKCζ−/− | ||

| Vegf-A | 1.27 ± 0.37 | 0.32 ± 0.03 | 0.03* |

| Vegf-C | 3.91 ± 0.32 | 1.90 ± 0.34 | 0.003** |

| Vegf-R3 | 1.36 ± 0.38 | 0.46 ± 0.04 | 0.04* |

| Pecam-1 | 3.19 ± 0.41 | 1.65 ± 0.15 | 0.01* |

| Mip-2 | 3.07 ± 0.63 | 1.19 ± 0.12 | 0.02* |

| Kc | 1.79 ± 0.22 | 0.90 ± 0.10 | 0.02* |

| IL-1 | 1.66 ± 0.12 | 0.96 ± 0.20 | 0.02* |

| IL-4 | 3.44 ± 0.31 | 1.02 ± 0.62 | 0.008** |

| IL-6 | 0.44 ± 0.09 | 1.24 ± 0.18 | 0.004** |

| IL-12p35 | 0.27 ± 0.02 | 0.65 ± 0.12 | 0.03* |

| IL-12p40 | 0.91 ± 0.28 | 2.71 ± 0.48 | 0.01* |

| IL-23p19 | 0.31 ± 0.08 | 0.27 ± 0.48 | 0.75 |

| IL-17F | 0.15 ± 0.02 | 0.17 ± 0.03 | 0.66 |

| IL-17A | 0.82 ± 0.24 | 0.31 ± 0.05 | 0.08 |

| IFNγ | 0.78 ± 0.28 | 1.78 ± 0.28 | 0.03* |

| Fhc | 0.67 ± 0.14 | 0.26 ± 0.02 | 0.02* |

| EGF | 2.22 ± 0.16 | 1.12 ± 0.06 | 0.03* |

| LIF | 1.80 ± 0.08 | 1.62 ± 0.09 | 0.30 |

| Oncostatin M | 1.10 ± 0.10 | 1.38 ± 0.02 | 0.10 |

| IL-11 | 3.51 ± 0.32 | 2.84 ± 0.77 | 0.20 |

| IL6R | 3.21 ± 0.76 | 2.96 ± 0.25 | 0.20 |

| gp130 | 2.97 ± 0.35 | 3.25 ± 0.14 | 0.20 |

| Cardiotrophin-1 | 1.19 ± 0.06 | 1.19 ± 0.01 | 0.50 |

Values are expressed as means ± standard deviations.

*, P < 0.05 versus WT value; **, P < 0.01 versus WT value.

FIG. 3.

IL-6 production is enhanced in PKCζ-deficient lung tumors and cells. (A) Immunohistochemical analysis of IL-6 expression in PKCζ+/+ and PKCζ−/− Ras-expressing lung tumors (n = 6 per treatment and genotype; scale bars, 50 μm). (B) Immunohistochemical analysis of phospho-Stat3 levels in lung samples, as in panel A. (C) IL-6 secretion by PKCζ+/+ and PKCζ−/− immortalized Ras-expressing EFs. Results are shown as means ± standard deviations. ***, P < 0.001. (D) Immunoblot analysis of phospho-Stat3, actin, and oncogenic Ras levels of EFs, as in panel C. The experiment shown is representative of two others with similar results.

To find out whether this novel role of PKCζ is a cell-autonomous phenomenon and whether it can be generalized to other cell types, we examined whether the genetic ablation of PKCζ would affect IL-6 production in EFs transformed by the Ras oncogene. To do this, we generated immortal EFs from WT and PKCζ-deficient mice by infection with a simian virus 40 large-T retroviral construct. These immortal EFs were infected with a retroviral vector expressing the oncogenic Ras mutant. Since this vector contains a hygromycin-selectable marker, infected cells were incubated in the presence of hygromycin for 3 weeks to select for Ras-expressing cells. After selection, the ability to produce IL-6 was determined by enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay of the supernatant. Results in Fig. 3C demonstrate that, in fact, IL-6 levels were higher in the supernatant of the Ras-transformed PKCζ−/− EFs than in the WT. Interestingly, PKCζ−/− EFs also displayed elevated phospho-Stat3 levels, consistent with the increased production of IL-6 and an autocrine action of this cytokine (Fig. 3D). Collectively, these observations demonstrate that during Ras-induced transformation, the activation of NF-κB genes is a PKCζ-dependent event, which is in keeping with our previous results in TNF-α-treated PKCζ−/− EFs (8, 21). But importantly, the induction of IL-6, which is also NF-κB and PKCζ dependent in TNF-α-treated EFs (8, 21), is unexpectedly enhanced in the Ras-expressing PKCζ−/− lungs and EFs. IL-6 is a proinflammatory cytokine that exerts an important role as a growth factor and tumor promoter in several systems, which could explain why the PKCζ-deficient mice display enhanced lung tumorigenesis. Therefore, our results unveil a novel and unexpected role of PKCζ as a tumor suppressor, likely through its ability to downregulate Ras-induced IL-6 production.

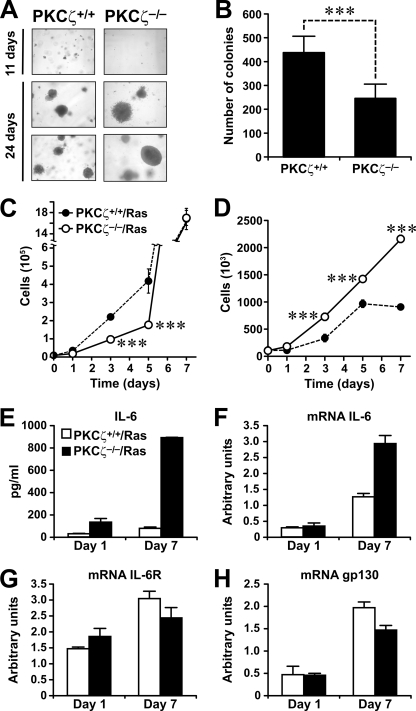

Lack of PKCζ improves Ras-induced proliferation under serum-limiting conditions.

To better understand the role of PKCζ in Ras-induced transformation, we analyzed the ability of immortalized PKCζ−/− EFs to form colonies in soft agar. Results in Fig. 4A (upper panels) and B show that at 11 days of growth, there were fewer PKCζ−/− cell colonies than WT cell colonies. Interestingly, at 24 days of culture, no differences were observed in the number of colonies between the two EF genotypes, but the PKCζ−/− cells had formed larger colonies (Fig. 4A, lower panels). These results suggest that PKCζ−/− Ras-transformed cells might be better able than WT cells to proliferate under conditions where access to medium nutrients is less than optimal. Interestingly, the data in Fig. 4C strongly suggest that this is the case. That is, in that experiment, we incubated Ras-transformed WT and PKCζ−/− immortalized EFs in standard growing conditions in the presence of 10% serum for several days, and the number of cells per culture dish was determined at days 1, 3, 5, and 7. Throughout the experiment, the medium was not changed, so that we could investigate the growth properties of both cell genotypes under conditions in which nutrients and serum are exhausted. Interestingly, at days 1, 3, and 5, the cell count for PKCζ−/− Ras-transformed cells was lower than that for WT Ras transformants. However, at day 7 the same number of cells was recovered for both genotypes (Fig. 4C), indicating that WT cells were more sensitive to a scarcity of nutrients and serum than PKCζ−/− cells. This result demonstrates that the lack of PKCζ in Ras transformants results in a greater capacity to grow under nutrient-adverse conditions. To further test this observation, WT and PKCζ−/− Ras-transformed cells were incubated as described above, but the initial amount of serum in the medium was reduced to 0.1%. Interestingly, PKCζ−/− Ras transformants showed greater increases in cell number than the WT Ras-transformed cells at all the time points measured (Fig. 4D). Particularly at days 5 and 7, WT Ras-transformed cells stopped growing, (presumably due to nutrient exhaustion) whereas the PKCζ-deficient Ras transformants maintained the same growth rate. These data confirm our hypothesis that the loss of PKCζ in Ras-transformed cells confers the ability to grow under nutrient- and mitogen-limiting conditions, which likely accounts for the ability of PKCζ−/− Ras lung tumors to grow more efficiently than WT tumors.

FIG. 4.

Growth properties of PKCζ−/−-deficient Ras-expressing cells. (A and B) Soft-agar growth of Ras-transformed PKCζ+/+ and PKCζ−/− EFs and quantitation of number of colonies at 11 days. The experiment shown in panel A is representative of another two with similar results. Results shown in panel B are means ± standard deviations. ***, P < 0.001. (C) Growth of Ras-transformed PKCζ+/+ and PKCζ−/− EFs in the presence of 10% FCS. (D) Growth of Ras-transformed PKCζ+/+ and PKCζ−/− EFs in 0.1% FCS. (E) IL-6 secretion by PKCζ+/+ and PKCζ−/− immortalized Ras-expressing EFs at day 1 or 7 of incubation in the absence of serum. Results are shown as means ± standard deviations. (F to H) mRNA levels of IL-6 (F), IL-6R (G), and gp130 (H) in PKCζ+/+ and PKCζ−/− immortalized Ras-expressing EFs incubated as for panel E. Results are shown as means ± standard deviations.

Interestingly, the increased IL-6 levels detected in PKCζ-deficient EFs under normal conditions (Fig. 3C) were even more enhanced in the mutant cells when they were incubated under nutrient deprivation conditions at both the protein (Fig. 4E) and mRNA (Fig. 4F) levels. Although the mRNA levels of IL-6R and gp130 were also increased as a consequence of nutrient stress, no differences were observed between WT and PKCζ-deficient cells (Fig. 4G and H).

Role of IL-6 in proliferation of Ras-transformed PKCζ-deficient cells.

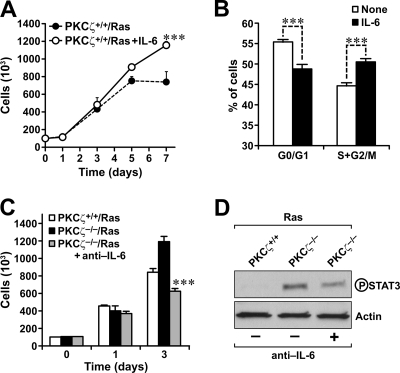

Since the Ras-transformed PKCζ-deficient cells produce more IL-6, which has been proposed to be a tumor-promoting cytokine by enhancing cell proliferation (1, 12, 14, 28, 31), to test whether the presence of IL-6 in the culture medium of WT cells is sufficient to phenocopy the cell growth properties of the Ras-transformed PKCζ-deficient cells, we incubated WT EFs under the same culture conditions as described above but in the absence or the presence of exogenously added recombinant IL-6. The data in Fig. 5A clearly demonstrate that the addition of IL-6 allows cells to grow better under conditions of scarce nutrients and mitogens. Cell cycle analysis of day-7 cultures under limiting serum conditions reveal no changes in the proportion of cell death either in the absence or in the presence of IL-6 (not shown). However, IL-6 addition led to an increase in the proportion of cells in the S-G2/M phase of the cell cycle compared to the untreated cells incubated in parallel (Fig. 5B). This is interpreted to mean that the presence of increased IL-6 levels in the PKCζ-deficient Ras-transformed cells will lead to enhanced growth properties under nutrient- and mitogen-deficient conditions without effects on cell survival. Therefore, we next determined whether the inactivation of the IL-6 released into the supernatant of PKCζ-deficient Ras-transformed cells with a neutralizing antibody would impair their proliferation under conditions of limited nutrients and serum. Interestingly, the presence of a neutralizing anti-IL-6 antibody in the culture medium dramatically impaired the ability of PKCζ-deficient Ras-transformed cells to grow under these conditions (Fig. 5C). Phospho-Stat3 levels are also increased in PKCζ-deficient Ras-transformed EFs compared to those in the WT cells, and more importantly, the incubation of the PKCζ−/− cells in the presence of the neutralizing anti-IL-6 antibody dramatically reduces phospho-Stat3 levels in the PKCζ-deficient cells (Fig. 5D). Collectively, these results demonstrate that the enhanced secretion of IL-6 in PKCζ−/− Ras transformants is essential for these cells to grow under conditions of limited nutrients and mitogens.

FIG. 5.

Role of IL-6 overproduction in the growth of PKCζ−/−-deficient Ras-expressing cells. (A) Growth of Ras-transformed PKCζ+/+ EFs in the absence or in the presence of recombinant mouse IL-6 (10 ng/ml) in 0.1% FCS. (B) Cell cycle analysis of PKCζ+/+ EFs in the absence or in the presence of recombinant mouse IL-6 (10 ng/ml) in 0.1% FCS at day 7. (C) Growth of Ras-transformed PKCζ+/+ or PKCζ−/− EFs in the absence or in the presence of neutralizing anti-IL-6 in 0.1% FCS. All results are means ± standard deviations. ***, P < 0.001. (D) Phospho-Stat3 levels of Ras-transformed EFs, either wild-type of PKCζ deficient, incubated in the absence or in the presence of neutralizing anti-IL-6 for 3 days in the absence of mitogens. This is a representative experiment of another two with very similar results.

Cell-autonomous role of PKCζ in Ras-induced tumorigenesis in vivo.

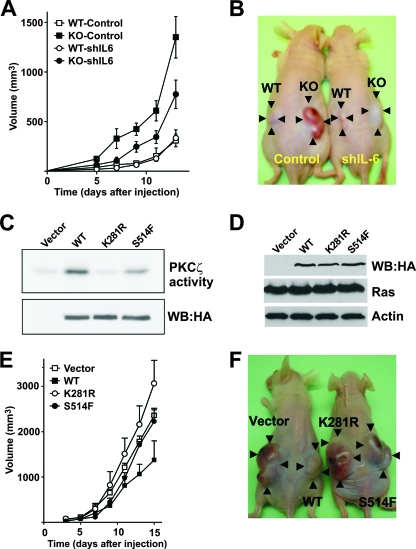

To demonstrate that PKCζ restrains tumorigenesis in vivo in a cell-autonomous manner and that IL-6 production is a critical event in that function, Ras-transformed EFs, either WT or PKCζ deficient, were transduced with an IL-6 short-hairpin-RNA (shRNA) lentivirus to knock down IL-6 levels in these cells. Results shown in Fig. S5 in the supplemental material demonstrate that IL-6 mRNA levels were effectively depleted in the shRNA-transduced cells. Afterwards, we injected cell suspensions of these four cell lines described above intradermally into each flank of nude mice, and tumors were allowed to develop for 13 days. The experiment was initially designed to last for 24 days, but due to the big increase in tumor size in the Ras-expressing PKCζ-deficient cells, we decided to stop the experiment at day 13 to avoid unnecessary discomfort to the animals. Interestingly, from the results of this experiment, it is clear that inoculation of Ras-expressing PKCζ-deficient cells gave bigger tumors that grew faster than the corresponding WT Ras-expressing cells (Fig. 6A), and interestingly, the inhibition of IL-6 expression significantly restrained that growth (Fig. 6A). Figure 6B shows an example of mice at day 13 that have been injected with different genotype cells in each flank. These results demonstrate that the increased Ras-induced tumorigenicity of the PKCζ-deficient cells is autonomous and that the enhanced production of IL-6 in the PKCζ−/− Ras transformants is important for the role of PKCζ as a cell-autonomous tumor suppressor in vitro and in vivo.

FIG. 6.

Role of IL-6 overproduction in tumor growth of PKCζ−/−-deficient Ras-expressing cells. (A) Suspensions of Ras-transformed PKCζ+/+ (WT) or PKCζ−/− (KO) EFs (8 × 105), transduced with a control or an shRNA IL-6 lentiviral vector, were intradermally injected into each flank of nude mice, and tumors were allowed to develop for 13 days. Tumor size was measured every other day. Results are means ± standard deviations (n = 5). (B) Representative mice injected with the different cell genotypes and left to develop for 13 days. (C) Extracts from 293 cells expressing HA-tagged versions of the PKCζ wild type (WT), a kinase-dead mutant form (K281R), or a mutant in which Ser514 was mutated to Phe (S514F) were immunoprecipitated, and their levels and activity were determined in vitro. The experiment shown is representative of another two with similar results. (D) Extracts from Ras-transformed NIH-3T3 fibroblasts expressing HA-tagged versions of the PKCζ wild type (WT), a kinase-dead mutant form (K281R), or a mutant in which Ser514 was mutated to Phe (S514F) were analyzed by immunoblotting. (E) Suspensions of Ras-transformed NIH-3T3 fibroblasts as described above were intradermally injected into each flank of nude mice, and tumors were allowed to develop for 15 days. Tumor size was measured every other day. Results are means ± standard deviations (n = 5). (F) Representative mice injected with the different NIH-3T3 Ras transformants expressing the different types of PKCζ constructs and left to develop for 15 days.

Of relevance to the results reported here, the analysis of human tumors revealed the presence of a PKCζ mutant in which Ser514 is mutated to Phe, suggesting a role of this PKCζ mutant in carcinogenesis (34). Based on our observations that the loss of PKCζ favors tumorigenesis, we hypothesized that this mutation would impair PKCζ activity. Interestingly, our data (Fig. 6C) demonstrate that this is indeed the case. That is, the substitution of Ser514 by Phe (S514F) severely impaired PKCζ enzymatic activity compared to that with the WT construct, although less dramatically than in the case of the kinase-dead mutant (K281R). This reinforces the notion that PKCζ manifests tumor suppressor activity. In support of this concept are the data of the experiments shown in Fig. 6E and F, in which NIH-3T3 fibroblasts expressing equal amounts of the WT or the kinase-dead (K281R) or S514F mutant (Fig. 6D) were injected into each flank of nude mice as described above. Importantly, overexpression of WT PKCζ impaired Ras-induced tumorigenesis in vivo, whereas the S514F mutant was unable to restrain tumor growth and the kinase-dead K281R mutant promoted tumor growth. These results are in keeping with the role of PKCζ as a tumor suppressor that needs its enzymatic activity to perform that function (Fig. 6E and F).

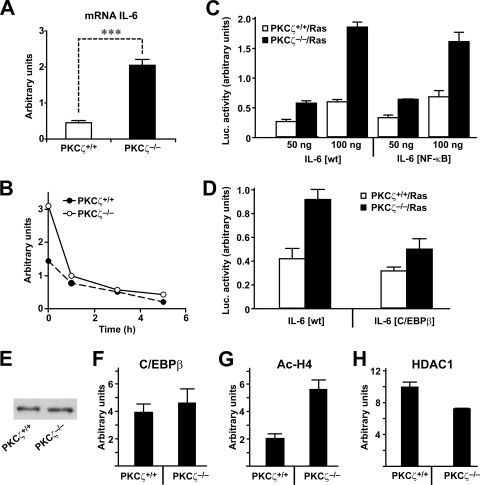

Role of PKCζ in the transcriptional control of IL-6 expression.

Once we have established the importance of IL-6 enhanced production during Ras-induced transformation in the absence of PKCζ, we determined the mechanisms whereby the loss of PKCζ favors IL-6 synthesis. Our data demonstrate that increased IL-6 production in PKCζ-deficient cells correlated with higher IL-6 mRNA levels in the Ras transformants than in Ras-transformed WT cells (Fig. 7A). Results in Fig. 7B show that PKCζ acts at the transcriptional level, since the difference in IL-6 mRNA levels, when Ras-expressing WT and PKCζ−/− EFs were compared, was completely abolished by incubating these cells with the transcriptional inhibitor DRB (5,6-dichloro-1-β-d-ribofuranosylbenzimidazole). A potential explanation for this finding would be that Ras transformation, in addition to activating NF-κB, also generates a set of signals that activate IL-6 synthesis that are antagonized by PKCζ. It is certainly likely that in the context of Ras-induced transformation, NF-κB-mediated IL-6 transcription would not be relevant and that other elements in the IL-6 promoter would be more important for the control of IL-6 levels, which would be impacted by PKCζ. The results shown in Fig. 7C demonstrate that this is actually the case, since PKCζ deficiency synergizes with Ras to activate IL-6 promoter activity even when the NF-κB element of that promoter is inactivated. This suggests that the ability of PKCζ to negatively impact Ras-induced activation of IL-6 should be through mechanisms other than NF-κB. Interestingly, a critical role for the C/EBPβ element has been demonstrated in IL-6 promoter activation by Ras (20). To address whether this enhancer element is important for the increased IL-6 promoter activity detected in the Ras-transformed PKCζ-deficient cells, we analyzed the promoter activity of a mutant in which the C/EBPβ element had been mutated. Results shown in Fig. 7D demonstrate that the ablation of that site severely impaired the enhanced IL-6 promoter activity detected in the PKCζ-deficient cells. In order to determine whether changes in the levels of C/EBPβ could account for the differences between WT and PKCζ-deficient EFs for IL-6 promoter activation, we analyzed the levels of this transcription factor in extracts from Ras-transformed EFs of both phenotypes. It is clear from results shown in Fig. 7E that there were no differences in the levels of C/EBPβ between WT and PKCζ-deficient transformed cells. When the recruitment of C/EBPβ to the IL-6 promoter in these cells was determined by ChIP, it was also apparent that no differences existed in this parameter (Fig. 7F). However, the levels of histone H4 acetylation in that promoter were significantly increased in the Ras-transformed PKCζ-deficient EFs over those in the WT transformed cells (Fig. 7G), indicating that the lack of PKCζ either favors the recruitment of a transcriptional acetyltransferase or decreases the recruitment of a deacetylase through the C/EBPβ enhancer element to the IL-6 promoter, which accounts for the increased levels of this cytokine in the PKCζ-deficient cells. Although no significant changes have been observed in the amount of the acetyltransferase CBP (not shown), the recruitment of the deacetylase HDAC1 was significantly decreased in the PKCζ-deficient cells (Fig. 7H). This observation offers an explanation for the enhanced H4 acetylation observed in the Ras-transformed PKCζ-deficient cells.

FIG. 7.

PKCζ regulates IL-6 promoter activity. (A) Q-PCR analysis of IL-6 mRNA levels in Ras-transformed EFs (PKCζ+/+ or PKCζ−/−). Results are shown as means ± standard deviations. ***, P < 0.001. (B) Q-PCR analysis of IL-6 mRNA levels of Ras-transformed EFs (PKCζ+/+ or PKCζ−/−) treated with DRB for different durations. The experiment shown is representative of two others with similar results. (C and D) Ras-transformed PKCζ+/+ or PKCζ−/− cells were transfected with two amounts of IL-6-luciferase promoter constructs, either wild type (wt) (C and D) or with mutations in the NF-κB (C) or C/EBPβ (D) enhancer elements, along with a Renilla control plasmid, for 24 h. Afterwards, luciferase activity was determined and normalized for Renilla. Results are the means ± standard deviations for triplicates. Luc., luciferase. (E) C/EBPβ protein levels were determined in Ras-transformed PKCζ+/+ or PKCζ−/− cells. (F, G, and H) ChIP determining the in vivo binding of C/EBPβ (F), acetylated histone H4 (G), or HDAC1 (H) to the IL-6 promoter in Ras-transformed PKCζ+/+ or PKCζ−/−cells. Relative IL-6 promoter binding was plotted as means ± standard deviations.

DISCUSSION

We show here that the loss of PKCζ enhances Ras-induced lung carcinogenesis in vivo through a mechanism involving the increased expression of IL-6, which favors the proliferation of Ras-transformed cells under nutrient- and mitogen-deprived conditions. We have also shown that the PKCζ mutation found in human cancers (S514F) led to reduced enzymatic activity (Fig. 6)(34), that the ability of PKCζ overexpression to restrain Ras-induced tumorigenesis is severely ablated by the S514F mutation (Fig. 6), and that a panel of human lung NSCLC exhibited reduced levels of PKCζ (see Fig. S2 in the supplemental material). Taken together, these results strongly suggest that the loss or inactivation of PKCζ leads to increased tumorigenicity, which highlights a new potential role for PKCζ as a tumor suppressor in vivo.

A recent study has shown that Ras-induced IL-6 production promotes tumorigenesis via the paracrine induction of angiogenesis (2). Consistent with this, our data reported here show that the loss of PKCζ enhances Ras-induced angiogenesis in lung tumors (Fig. 2D to F). However, we propose here that in addition to that role, IL-6 secretion is also essential to providing the Ras transformants with a cell-autonomous competitive advantage with respect to growth under nutrient-scarce conditions, a situation that the cancer cell encounters during tumor development. Therefore, in the context of PKCζ deficiency, the ability of Ras to induce IL-6 production is enhanced, which promotes tumorigenesis through two different mechanisms: increased angiogenesis and an enhanced ability to grow under nutrient-limiting conditions. Of note, the S514F mutation in PKCζ, which confers increased tumorigenicity in xenografts (Fig. 6E and F), also leads to enhanced IL-6 production (data not shown).

We also show here that the expression of NF-κB-dependent genes is dramatically reduced in the Ras-expressing PKCζ−/− lungs compared to that in WT Ras-expressing lungs. This is in good agreement with previous work demonstrating that PKCζ plays a critical role in the NF-κB pathway by phosphorylating RelA/p65, the transcriptional subunit of the NF-κB complex (8, 21). In this regard, we recently demonstrated that the genetic inactivation of p62, an interacting partner of aPKC, inhibits Ras-induced lung carcinogenesis and NF-κB activation (9), which brings up another interesting aspect of the work presented here. Thus, p62 is a PB1-containing adapter that has been proposed to locate the aPKCs, which also have a PB1 domain, in the NF-κB signaling cascade (25). Based on the biochemical interaction between PKCζ and p62, one would have expected that the two knockout mice would have identical phenotypes (25, 26). Our data demonstrate that in fact, PKCζ and p62 both control the expression of NF-κB-dependent genes, suggesting that the p62-PKCζ module is relevant for Ras-induced NF-κB. However, there is an important difference in the mechanisms whereby p62 and PKCζ participate in the NF-κB pathway in response to Ras. That is, unlike PKCζ, p62 is required to activate the IKK complex through the activation of K63-mediated polyubiquitination of TRAF6 (9, 10, 32, 35). This explains why p62 ablation inhibits the actual translocation of RelA/p65 to the nucleus in lung tumor cells (9) whereas ablation of PKCζ does not, although defective expression of NF-κB-dependent transcripts is observed in PKCζ−/− lungs. In many systems, PKCζ regulates NF-κB at the level of RelA/p65 phosphorylation and transcriptional activity without affecting IKK activity and the translocation of the NF-κB complex to the nucleus (8). Therefore, it is possible that in the PKCζ−/− lungs, Ras is capable of triggering NF-κB nuclear translocation because p62 is intact, but because of the lack of PKCζ, it is unable to fully activate its transcriptional activity. Thus, whereas p62 regulates TRAF6 ubiquitin activity and therefore IKK activation, PKCζ fine-tunes the NF-κB response by controlling the transcriptional activity of the NF-κB complex. This model, although consistent with the available biochemical and genetic evidence linking p62 and PKCζ to the NF-κB cascade (25, 27), would not explain the increased IL-6 levels observed in PKCζ-deficient Ras-expressing lung and cells. Since IL-6 production requires NF-κB and PKCζ in other systems (8), our observation that the loss of PKCζ enhances IL-6 production in response to Ras transformation was surprising. However, from our data it is clear that Ras and PKCζ regulate IL-6 promoter activity and transcription through a mechanism independent of the NF-κB enhancer element and which involves the regulation by PKCζ of C/EBPβ to orchestrate promoter histone acetylation, a key event in chromatin remodeling during gene transcription. This suggests that PKCζ can both positively regulate NF-κB and at the same time exert a negative effect on IL-6 transcription through a κB-independent pathway.

IL-6 has been shown to be essential for tumor progression in several systems (1, 12, 14, 28, 31). Thus, the increased levels of IL-6 in PKCζ-deficient mice explain their enhanced tumorigenicity, even in the context of an inflammatory condition in Ras-expressing PKCζ−/− lungs characterized by high IFN-γ and IL-12 levels and reduced IL-4 levels (Table 1), which are hallmarks of an M1-type immunological antitumor response (3, 29). The reduced levels of IL-1 observed in the mutant lungs compared to results for the WT (Table 1) might explain how the lack of PKCζ triggers this M1 response, since it has recently been shown that the IL-1R/MyD88/IKKβ cascade is essential for the “reeducation” of macrophages by tumor cells toward an M2 “protumorigenic” phenotype (16). Therefore, the lower levels of IL-1 production observed in the Ras PKCζ−/− lungs could lead to a skewed M1 response that would promote an antitumorigenic immunological response in the PKCζ-deficient mice. However, in this model, the lack of PKCζ favors the synthesis of IL-6 in the Ras-expressing lungs in a cell-type-independent and autonomous manner, which induces increased tumorigenesis even under M1 immunological conditions that are favorable for tumor reduction. Through this scenario, PKCζ could emerge as a critical step in the generation of inflammatory cytokines that might decide the final outcome of the carcinogenic process. The data presented here are of great functional relevance because they have unveiled a previously unrecognized role of PKCζ as a negative regulator of lung cancer through its ability to control IL-6 production by transformed cells.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank Jeff Whitsett (Cincinnati Children's Hospital Medical Center) for providing CCSP-rtTA mice, Harold Varmus (Memorial Sloan-Kettering Cancer Center) for providing Tet-op-K-RasG12D mice, Maryellen Daston for editing the manuscript, Glenn Doerman for preparing the figures, and Lyndsey Cheuvront and Emily Kellner for technical assistance.

This work was funded in part by the University of Cincinnati-CSIC Collaborative Agreement and by NIH grant R01-AI072581.

Footnotes

Published ahead of print on 27 October 2008.

Supplemental material for this article may be found at http://mcb.asm.org/.

REFERENCES

- 1.Amsen, D., J. M. Blander, G. R. Lee, K. Tanigaki, T. Honjo, and R. A. Flavell. 2004. Instruction of distinct CD4 T helper cell fates by different notch ligands on antigen-presenting cells. Cell 117515-526. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ancrile, B., K. H. Lim, and C. M. Counter. 2007. Oncogenic Ras-induced secretion of IL6 is required for tumorigenesis. Genes Dev. 211714-1719. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Balkwill, F., K. A. Charles, and A. Mantovani. 2005. Smoldering and polarized inflammation in the initiation and promotion of malignant disease. Cancer Cell 7211-217. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Barradas, M., A. Monjas, M. T. Diaz-Meco, M. Serrano, and J. Moscat. 1999. The downregulation of the pro-apoptotic protein Par-4 is critical for Ras-induced survival and tumor progression. EMBO J. 186362-6369. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Berra, E., M. T. Diaz-Meco, I. Dominguez, M. M. Municio, L. Sanz, J. Lozano, R. S. Chapkin, and J. Moscat. 1993. Protein kinase C zeta isoform is critical for mitogenic signal transduction. Cell 74555-563. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bos, J. L. 1989. ras oncogenes in human cancer: a review. Cancer Res. 494682-4689. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Diaz-Meco, M. T., J. Lozano, M. M. Municio, E. Berra, S. Frutos, L. Sanz, and J. Moscat. 1994. Evidence for the in vitro and in vivo interaction of Ras with protein kinase C zeta. J. Biol. Chem. 26931706-31710. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Duran, A., M. T. Diaz-Meco, and J. Moscat. 2003. Essential role of RelA Ser311 phosphorylation by zetaPKC in NF-kappaB transcriptional activation. EMBO J. 223910-3918. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Duran, A., J. F. Linares, A. S. Galvez, K. Wikenheiser, J. M. Flores, M. T. Diaz-Meco, and J. Moscat. 2008. The signaling adaptor p62 is an important NF-[kappa]B mediator in tumorigenesis. Cancer Cell 13343-354. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Duran, A., M. Serrano, M. Leitges, J. M. Flores, S. Picard, J. P. Brown, J. Moscat, and M. T. Diaz-Meco. 2004. The atypical PKC-interacting protein p62 is an important mediator of RANK-activated osteoclastogenesis. Dev. Cell 6303-309. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Fisher, G. H., S. L. Wellen, D. Klimstra, J. M. Lenczowski, J. W. Tichelaar, M. J. Lizak, J. A. Whitsett, A. Koretsky, and H. E. Varmus. 2001. Induction and apoptotic regression of lung adenocarcinomas by regulation of a K-Ras transgene in the presence and absence of tumor suppressor genes. Genes Dev. 153249-3262. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Gao, T., A. Toker, and A. C. Newton. 2001. The carboxyl terminus of protein kinase C provides a switch to regulate its interaction with the phosphoinositide-dependent kinase, PDK-1. J. Biol. Chem. 27619588-19596. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Garcia-Cao, I., M. Lafuente, L. Criado, M. Diaz-Meco, M. Serrano, and J. Moscat. 2003. Genetic inactivation of Par4 results in hyperactivation of NF-κB and impairment of JNK and p38. EMBO Rep. 4307-312. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Grivennikov, S., and M. Karin. 2008. Autocrine IL-6 signaling: a key event in tumorigenesis? Cancer Cell 137-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Guerra, C., N. Mijimolle, A. Dhawahir, P. Dubus, M. Barradas, M. Serrano, V. Campuzano, and M. Barbacid. 2003. Tumor induction by an endogenous K-ras oncogene is highly dependent on cellular context. Cancer Cell 4111-120. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hagemann, T., T. Lawrence, I. McNeish, K. A. Charles, H. Kulbe, R. G. Thompson, S. C. Robinson, and F. R. Balkwill. 2008. “Re-educating” tumor-associated macrophages by targeting NF-κB. J. Exp. Med. 2051261-1268. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Hanahan, D., and R. A. Weinberg. 2000. The hallmarks of cancer. Cell 10057-70. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Hayden, M. S., and S. Ghosh. 2008. Shared principles in NF-kappaB signaling. Cell 132344-362. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Inoue, T., T. Yoshida, Y. Shimizu, T. Kobayashi, T. Yamasaki, Y. Toda, T. Segawa, T. Kamoto, E. Nakamura, and O. Ogawa. 2006. Requirement of androgen-dependent activation of protein kinase Czeta for androgen-dependent cell proliferation in LNCaP Cells and its roles in transition to androgen-independent cells. Mol. Endocrinol. 203053-3069. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kuilman, T., C. Michaloglou, L. C. Vredeveld, S. Douma, R. van Doorn, C. J. Desmet, L. A. Aarden, W. J. Mooi, and D. S. Peeper. 2008. Oncogene-induced senescence relayed by an interleukin-dependent inflammatory network. Cell 1331019-1031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Leitges, M., L. Sanz, P. Martin, A. Duran, U. Braun, J. F. Garcia, F. Camacho, M. T. Diaz-Meco, P. D. Rennert, and J. Moscat. 2001. Targeted disruption of the zetaPKC gene results in the impairment of the NF-kappaB pathway. Mol. Cell 8771-780. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Malkinson, A. M. 1991. Promoters, co-carcinogens and inhibitors of pulmonary carcinogenesis in mice: an overview. Exp. Lung Res. 17435-437. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Mayo, M. W., C. Y. Wang, P. C. Cogswell, K. S. Rogers-Graham, S. W. Lowe, C. J. Der, and A. S. Baldwin, Jr. 1997. Requirement of NF-kappaB activation to suppress p53-independent apoptosis induced by oncogenic Ras. Science 2781812-1815. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Meuwissen, R., and A. Berns. 2005. Mouse models for human lung cancer. Genes Dev. 19643-664. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Moscat, J., M. T. Diaz-Meco, A. Albert, and S. Campuzano. 2006. Cell signaling and function organized by PB1 domain interactions. Mol. Cell 23631-640. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Moscat, J., M. T. Diaz-Meco, and M. W. Wooten. 2007. Signal integration and diversification through the p62 scaffold protein. Trends Biochem. Sci. 3295-100. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Moscat, J., P. Rennert, and M. T. Diaz-Meco. 2006. PKCzeta at the crossroad of NF-kappaB and Jak1/Stat6 signaling pathways. Cell Death Differ. 13702-711. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Naugler, W. E., T. Sakurai, S. Kim, S. Maeda, K. Kim, A. M. Elsharkawy, and M. Karin. 2007. Gender disparity in liver cancer due to sex differences in MyD88-dependent IL-6 production. Science 317121-124. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Pollard, J. W. 2004. Tumour-educated macrophages promote tumour progression and metastasis. Nat. Rev. Cancer 471-78. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Rhodes, D. R., S. Kalyana-Sundaram, V. Mahavisno, R. Varambally, J. Yu, B. B. Briggs, T. R. Barrette, M. J. Anstet, C. Kincead-Beal, P. Kulkarni, S. Varambally, D. Ghosh, and A. M. Chinnaiyan. 2007. Oncomine 3.0: genes, pathways, and networks in a collection of 18,000 cancer gene expression profiles. Neoplasia 9166-180. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Sansone, P., G. Storci, S. Tavolari, T. Guarnieri, C. Giovannini, M. Taffurelli, C. Ceccarelli, D. Santini, P. Paterini, K. B. Marcu, P. Chieco, and M. Bonafe. 2007. IL-6 triggers malignant features in mammospheres from human ductal breast carcinoma and normal mammary gland. J. Clin. Investig. 1173988-4002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Sanz, L., M. T. Diaz-Meco, H. Nakano, and J. Moscat. 2000. The atypical PKC-interacting protein p62 channels NF-kappaB activation by the IL-1-TRAF6 pathway. EMBO J. 191576-1586. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Tuveson, D. A., A. T. Shaw, N. A. Willis, D. P. Silver, E. L. Jackson, S. Chang, K. L. Mercer, R. Grochow, H. Hock, D. Crowley, S. R. Hingorani, T. Zaks, C. King, M. A. Jacobetz, L. Wang, R. T. Bronson, S. H. Orkin, R. A. DePinho, and T. Jacks. 2004. Endogenous oncogenic K-ras(G12D) stimulates proliferation and widespread neoplastic and developmental defects. Cancer Cell 5375-387. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Wood, L. D., D. W. Parsons, S. Jones, J. Lin, T. Sjoblom, R. J. Leary, D. Shen, S. M. Boca, T. Barber, J. Ptak, N. Silliman, S. Szabo, Z. Dezso, V. Ustyanksky, T. Nikolskaya, Y. Nikolsky, R. Karchin, P. A. Wilson, J. S. Kaminker, Z. Zhang, R. Croshaw, J. Willis, D. Dawson, M. Shipitsin, J. K. V. Willson, S. Sukumar, K. Polyak, B. H. Park, C. L. Pethiyagoda, P. V. K. Pant, D. G. Ballinger, A. B. Sparks, J. Hartigan, D. R. Smith, E. Suh, N. Papadopoulos, P. Buckhaults, S. D. Markowitz, G. Parmigiani, K. W. Kinzler, V. E. Velculescu, and B. Vogelstein. 2007. The genomic landscapes of human breast and colorectal cancers. Science 3181108-1113. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Wooten, M. W., T. Geetha, M. L. Seibenhener, J. R. Babu, M. T. Diaz-Meco, and J. Moscat. 2005. The p62 scaffold regulates nerve growth factor-induced NF-kappaB activation by influencing TRAF6 polyubiquitination. J. Biol. Chem. 28035625-35629. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.