Abstract

Netrin1 is a diffusible factor that attracts commissural axons to the floor plate of the spinal cord. Recent evidence indicates that Netrin1 is widely expressed and functions in the development of multiple organ systems. In mammals, there are three genes encoding Netrins, whereas in zebrafish, only the Netrin1 orthologs netrin1a and netrin1b have been identified. Here, we have cloned two new zebrafish Netrins, netrin2 and netrin4, and present a comparative sequence and expression analysis. Despite significant sequence similarity with netrin1a/netrin1b, netrin2 displays a unique expression pattern. Netrin2 transcript is first detected in the notochord and in developing somites at early somitogenesis. By late somitogenesis, netrin2 is expressed in fourth rhombomere and is subsequently expressed in the hindbrain and otic vesicles. In contrast, netrin4 is detected only at very low levels during early development. The nonoverlapping expression patterns of these four Netrins suggest that they may play unique roles in zebrafish development.

Keywords: axon guidance, notochord, otic vesicle, rhombomere, pectoral fins, somites, hindbrain, tectum

INTRODUCTION

The formation of neuronal connections requires both attractive and repulsive guidance cues that direct growth cones to their appropriate targets. The Netrins are diffusible guidance molecules that can either attract or repel growth cones, depending on the constellation of receptors on the target axon. They are evolutionarily conserved vertebrate homologs of the Caenorhabditis elegans UNC-6 protein that is involved in axon guidance and cell migration (Livesey, 1999). Whereas unc-6 mutations disrupt the circumferential projection of growth cones along the dorsoventral axis of the C. elegans body wall (Hedgecock et al., 1990; Ishii et al., 1992), mutations in murine and Drosophila netrins cause defects in commissural axon guidance to the ventral midline of the central nervous system (CNS; Serafini et al., 1994; Harris et al., 1996; Mitchell et al., 1996). In addition to their roles in nervous system development, the Netrins appear to play roles in the development of other organ systems. Netrin1 regulates ear development in the mouse, as revealed by the examination of Netrin1 gene trap mice (Salminen et al., 2000). Recent evidence indicates that Netrin1 also regulates mammary gland morphogenesis as well as promoting angiogenesis both in vitro and in vivo (Srinivasan et al., 2003; Lu et al., 2004; Park et al., 2004). Netrin1 has also been implicated in the regulation of cell survival and tumorigenesis (Arakawa, 2004; Mazelin et al., 2004).

Netrin family proteins are characterized by two extracellular laminin-like domains (VI and V) and a highly basic region in the C-terminus of the protein. Laminin-like domains VI and V have been implicated in receptor interaction (Keino-Masu et al., 1996; Kruger et al., 2004), while recent evidence suggests that the C-terminal basic region also mediates interaction with integrin receptors to modulate pancreatic epithelial cell development (Yebra et al., 2003).

Two classes of receptors have been identified that recognize Netrins. The DCC (Deleted in Colorectal Cancer) family includes DCC and Neogenin in vertebrates, UNC-40 in C. elegans, and Frazzled in Drosophila melanogaster. The second family, the Unc5 receptors, includes vertebrate UNC5A/B/C/D (or UNC5H1/2/3/4), which are homologs of the C. elegans UNC-5 receptor. Ablation of the DCC receptor results in compromised axonal attraction (Fazeli et al., 1997), whereas loss of Neogenin is associated with impaired mammary gland ductal formation (Srinivasan et al., 2003). Studies in C. elegans showed that the UNC-5 receptor mediates repulsive guidance activities of Netrin (Hedgecock et al., 1990; Hamelin et al., 1993). Mutation of murine Unc5b leads to vessel branching defects during vascular development (Lu et al., 2004). In vertebrates, complex formation between DCC and Unc5b converts Netrin1-induced growth cone attraction to repulsion (Hong et al., 1999).

Three secreted members of the Netrin family have been identified to date in human and mouse: Netrin1, Netrin2-like (called Netrin3 in mouse), and Netrin4 (beta-Netrin) (Serafini et al., 1996; Wang et al., 1999; Koch et al., 2000; Yin et al., 2000). Mammalian Netrin2-like is so named because it is most similar to, but somewhat divergent from, chick Netrin2. Because all Netrin family members promote axonal outgrowth in in vitro assays, it is likely that there are functional redundancies among the Netrins. Apart from Netrin1, the specific roles of the other Netrins remain unknown and await combinatorial gene inactivation studies. In zebrafish, there are two Netrin1 orthologs, netrin1a (Lauderdale et al., 1997) and netrin1b (originally named net1; Strähle et al., 1997). These two genes are primarily expressed near the ventral midline of the CNS, throughout the length of the rostro-caudal axis. Here, we report the cloning and characterization of two new zebrafish Netrin family members, netrin2 and netrin4. We compared the transcript distributions of all four zebrafish Netrins in developing embryos. Although netrin2 and netrin4 possess sequence and structural similarities to netrin1a and netrin1b, their expression patterns are markedly different, suggesting unique roles for these genes during development.

RESULTS AND DISCUSSION

Identification of netrin2 and netrin4

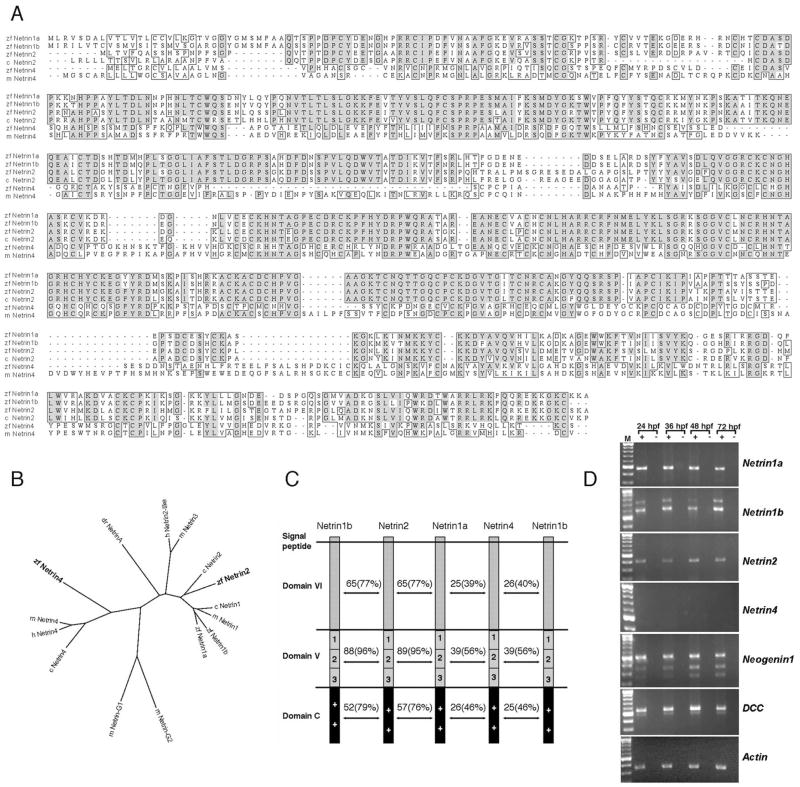

To investigate whether additional Netrin homologs exist in zebrafish, database mining was performed with zebrafish Netrin1a and Netrin1b amino acid query sequences. We identified an expressed sequence tag (EST) clone (accession no. AL916140) that shows significant similarity to mammalian Netrin2-like. A genomic database search (www.sanger.ac.uk/projects/D_rerio) further revealed zebrafish clones homologous to mammalian Netrin4. Complete cDNA sequences for each of these genes were obtained by RACE polymerase chain reaction and nested polymerase chain reaction (PCR). The extended cDNA sequences were shown to contain full-length open reading frames, based on protein sequence alignments, the presence of upstream in-frame stop codons and an N-terminal signal peptide. ClustalW alignments and phylogenetic analysis demonstrated that the predicted protein sequences of netrin2 and netrin4 represent Netrin family members with the highest degree of similarity to chick Netrin2 and mouse Netrin4, respectively (Fig. 1A, B). Zebrafish netrin2 and netrin4 encode the typical domains of Netrin family members: an N-terminal laminin-like domain VI followed by a laminin-like domain V, and an integrin-interacting basic region (domain C) at the C-terminus (Fig. 1C). Zebrafish genomic BLAST searches indicate that netrin2 and netrin4 map to linkage group 14 and 7, respectively. Together, sequence similarities and the presence of Netrin-specific domains indicate that these proteins represent new zebrafish orthologs of Netrin2 and Netrin4.

Fig. 1.

ClustalW amino acid alignment of Netrin sequences and reverse transcriptase-polymerase chain reaction (RT-PCR) expression analysis of Netrin and Netrin receptor genes. A: Alignment of chick Netrin2 and mouse Netrin4 with zebrafish Netrin2 and Netrin4. Dark and pale gray boxes represent, respectively, identical and similar amino acids. zf, zebrafish; m, mouse; c, chick. B: Phylogenetic analysis of predicted zebrafish Netrin proteins based on ClustalW alignment using the Biology Workbench site (http://workbench.sdsc.edu). zf, zebrafish; h, human; m, mouse; c, chick; dr, Drosophila. Zebrafish Netrin2 is most closely related to chick Netrin2, whereas zebrafish Netrin4 is closely related to human and mouse Netrin4. The GPI-linked proteins Netrin-G1 and -G2 are included for comparison. C: Zebrafish Netrin2 and Netrin4 contain all the domains (domains VI, V, and C) described in other Netrin family members. Numbers indicate identity, and parentheses represent similarities between two given proteins. Netrin2 is highly similar to Netrin1a and 1b, while Netrin4 is the most divergent member of the Netrin family. D: RT-PCR analyses were performed to detect netrin transcripts in total RNA collected from 24, 36, 48, and 72 hpf embryos. Actin amplification served as a loading control, and mock amplifications (−, no RT) confirmed that bands represent amplification of RNA. Netrin2 is expressed from 24 hpf through 72 hpf, whereas netrin4 is not detected at any of these stages (25 cycles). Netrin1a, netrin1b, dcc, and neogenin1 are expressed at all stages.

Developmental Expression Patterns

To gain insight into the expression profiles of these genes during zebrafish development, reverse transcriptase-PCR (RT-PCR) analyses were performed with total RNA from 24, 36, 48, and 72 hpf embryos. Netrin1a, netrin1b, and netrin2 transcripts were detected in all four stages at relatively constant levels. Netrin4 transcript was not detectable under the same conditions (Fig. 1D). Netrin4 PCR product was detected only after extended amplification (data not shown). The relatively weak expression of zebrafish netrin4 during early development is reminiscent of mouse Netrin4, further supporting the hypothesis that netrin4 is a true Netrin4 ortholog (data not shown; Koch et al., 2000). Two zebrafish Netrin receptors, dcc and neogenin1 (Hjorth et al., 2001; Shen et al., 2002; Fricke and Chien, manuscript submitted for publication) are expressed coincident with netrin1a, 1b, and 2 during this developmental window (Fig. 1D).

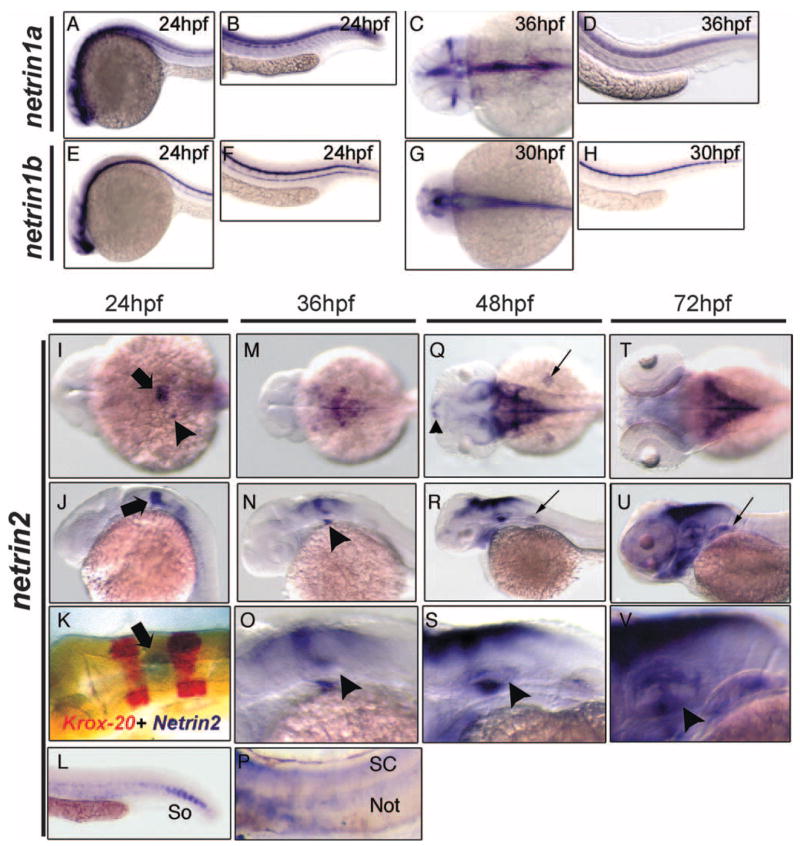

We further investigated the expression pattern of all four zebrafish Netrin family members during embryonic development using RNA in situ hybridization (Fig. 2). Netrin1a and netrin1b transcripts are primarily detected in the developing CNS as previously reported (Lauderdale et al., 1997; Strähle et al., 1997). At 24 hours postfertilization (hpf), netrin1a is expressed in the brain, spinal cord, and somites. By 36 hpf, netrin1a is expressed in the optic nerve, and broadly in the ventral hindbrain and spinal cord. At 24 hpf, netrin1b is detected in the brain, the floor plate of the spinal cord, and the hypochord; at 30 hpf, it is expressed primarily in the floor plate of the hindbrain and spinal cord.

Fig. 2.

Netrin mRNA expression in zebrafish embryos. Netrin1a, netrin1b, and netrin2 expression domains were analyzed by RNA in situ hybridization during the first 3 days of embryonic development. A–H: Lateral (A, B, D–F, H) and dorsal (C, G) views of netrin1a (A–D) and netrin1b (E–H). A, B: netrin1a is expressed in the brain, spinal cord, and somites at 24 hpf. C, D: By 36 hpf, somite expression has diminished and expression is visible in the optic nerve. E, F: netrin1b is detected in the ventral brain, the floor plate of the spinal cord, and the hypochord at 24 hpf. G, H: Hypochord expression diminishes by 30 hpf. I–V: Dorsal (I, K, M, Q, T) and lateral (J, L, N–P, R, S, U, V) views of netrin2 expression at stages indicated. I, J: netrin2 is expressed in the fourth rhombomere (arrow) and in the otic vesicle (arrowhead) at 24 hpf. K: krox20 two-color in situ hybridizations confirm rhombomere 4 localization of netrin2 (arrow). L: netrin2 is expressed in the ventral somites (So) at 24 hours postfertilization (hpf). M, N: At 36 hpf, netrin2 expression extends to the dorsal and ventral margins of the otic vesicle (arrowhead) and in the hindbrain region. O: Enlarged view of the hindbrain and otic vesicle (arrowhead). P: netrin2 is also detected in notochord (Not) and spinal cord (SC) after prolonged colorimetric development. Q, R: At 48 hpf, netrin2 is expressed in bilateral clusters in the telencephalon (small arrowhead), around the medial and caudal margins of the tectum, in the cerebellum, and along the dorsal hindbrain, and in the ventromedial margin of the otic vesicles. It is also expressed in the pharyngeal arches and pectoral fins (small arrows). In contrast to netrin1a and 1b, expression in the brain is primarily constrained to the dorsal aspect. S: Higher magnification views of the hindbrain and otic vesicle; arrowhead denotes the strong expression in the ventral margin of the otic epithelium. T, U: By 72 hpf, expression in the pharyngeal arches is robust, and expression in the dorsal aspect of the otic epithelium and pectoral fins (small arrow) has strengthened. V: Higher magnification view of the otic vesicle; the arrowhead denotes the strong expression in the developing inner ear.

At 24 hpf, netrin2 is expressed with remarkable specificity in hindbrain rhombomere 4, with weaker expression more posteriorly in the hindbrain as well as in ventral somites in the tail (Fig. 2I–L). Expression is also seen in a small cluster of cells in the developing otic vesicle (Fig. 2I). The hindbrain expression domain was identified as rhombomere 4 (Fig. 2K) using double staining with krox20, which is expressed in rhombomeres 3 and 5 (Oxtoby and Jowett, 1993). At 36 hpf, netrin2 expression has extended anteriorly and posteriorly along the roof of the hindbrain and is present at the dorsal margin of the otic vesicle (Fig. 2M–O). Strong expression is evident in the ventromedial aspect of the otic epithelium by 36 hpf as well (Fig. 2N, O). Netrin2 is also detectable in the notochord (Not) and spinal cord (SC) after long periods of colorimetric development (Fig. 2P). By 48 hpf and 72 hpf, netrin2 expression is observed in expanded domains within the brain, otic vesicles, pharyngeal arches, and pectoral fin buds. Expression has extended anteriorly past the midbrain/hindbrain boundary around the medial and caudal margins of the tectum, and has extended posteriorly to the cerebellum and along the roof of the hindbrain (Fig. 2Q–V). Unlike the ventral expression of netrin1a and 1b, netrin2 expression in the hindbrain and midbrain is largely dorsal. Netrin4 was not detected at any of these developmental stages, consistent with the RT-PCR results (data not shown).

To examine the onset of the zebrafish netrin2 mRNA during early stages embryogenesis, embryos from cleavage through somitogenesis stages were collected and hybridized with netrin2 riboprobe (Supplementary Figure S1, which can be viewed at http://www.interscence.wiley.com/jpages/1058-8388/suppmat). Netrin2 mRNA was strongly detected in the notochord in the early somitogenesis staged embryos. Netrin2 is also detected in developing somites (adaxial cells) in mid-somitogenesis embryos. Trunk expression is significantly reduced by 22 hpf. No signal was detected in cleavage, blastula, gastrula embryos, or in tail bud stage. Therefore, netrin2 expression commences by early somitogenesis stages. These data suggest that netrin2 mRNA may play roles in early development even before axonal tracts and nerves are established.

How do the expression patterns of the zebrafish Netrins compare with those of their homologs in mouse and chick? Phylogenetic analysis shows that zebrafish netrin2 is most similar to chick Netrin2 and somewhat less similar to mouse Netrin 3/human Netrin2-like (Fig. 1B). Chick netrin2 is expressed in the ventral two thirds of the spinal cord and dermomyotome (Kennedy et al., 1994). Zebrafish netrin2 is also detected in the spinal cord, albeit weakly, and ventrally in the caudal somites (Fig. 2L, P). In contrast, mouse Netrin3 is restricted to the sensory ganglia, mesenchymal cells, and muscles but is not expressed in the CNS during early mouse development (Wang et al., 1999). Furthermore, zebrafish netrin2 is strongly expressed in the notochord and developing somites in early segmentation-staged embryos similar to the chick netrins (Supplemental Fig. 1). Thus, zebrafish netrin2 is most closely related to chick Netrin2 both in sequence and in expression profile. Whether they share similar functions during development remains to be determined. Interestingly, mouse Netrin1 is expressed in the ear during development (Salminen et al., 2000), as is zebrafish netrin2, suggesting that they may have similar functional roles. The relatedness of mouse and zebrafish Netrin4 is supported by the finding that neither gene is expressed appreciably during early embryonic development.

Summary

Here, we have reported the identification of two new members of the Netrin family of secreted proteins, zebrafish netrin2 and netrin4. Both netrin2 and netrin4 show significant differences in expression relative to the previously described zebrafish Netrins, netrin1a and 1b, which are far more robustly expressed in the spinal cord and trunk of developing embryos. These expression data suggest that each family member may play unique functional roles. In the future, it will be interesting to elucidate the divergent functions of these Netrin proteins during zebrafish development.

EXPERIMENTAL PROCEDURES

Cloning of Zebrafish netrin2 and netrin4

A BLAST search of the zebrafish EST database with netrin1a and 1b amino acid sequences yielded one sequence, AL916140. Fugu rubripes netrin4 sequence was identified based on similarities with mouse Netrin4 (www.ensembl.org/Fugu_rubripes/). Genomic database searches (Sanger Institute) with the Fugu netrin4 EST yielded a putative zebrafish netrin4. Total RNA was isolated from 24 hpf wild-type zebrafish embryos using TRIZOL (GIBCO-BRL) as previously reported (Lee et al., 2001). The RNA was reverse-transcribed with a RETRO-script kit (Ambion). RT-PCR was performed using primers spanning sequence from the clone AL916140 and from the genomic sequences for netrin4. These PCR fragments were extended by 5′ and 3′ rapid amplification of cDNA ends (RACE) using the BD SMART RACE cDNA amplification kit (BD Biosciences) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. Amplified products were verified by sequence analysis. The sequences of the zebrafish netrin2 and netrin4 genes have been submitted to GenBank under the following accession numbers: zebrafish netrin2, AY928518; and zebrafish netrin4, AY928519.

RT-PCR Analysis

RNA was extracted from whole embryos staged at 24, 36, 48, and 72 hpf. Two micrograms of total RNA was reverse-transcribed using random hexamers provided with the SuperScript III kit (Invitrogen). The primer pairs for zebrafish β-actin were 5′-cccaaggccaacagggaaaa-3′ (forward) and 5′-ggtgcccatctcctgctcaa-3′(reverse); netrin1a, 5′-tgacagatgcaaaccttttcac-3′ (forward) and 5′-ggattcacagtctgatggctcttc-3′ (reverse); netrin1b, 5′-gcctgcgattgtcatcctgttgg-3′ (forward) and 5′-ccctctcttgtcgcgctgctgg-3′ (reverse); netrin2, 5′-tatagggacatgggcaaagc-3′ (forward) and 5′-ctcttttcagcgggtctcc-3′ (reverse); netrin4, 5′-ttttaaaaggaggctgcctgtg-3′ (forward) and 5′-gcatttgtctggatgactgagg-3′ (reverse) and 5′-acactgccaacactgtcagagc-3′ (forward) and 5′-gcctttatcatgagcacccaac-3′ (reverse); dcc, 5′-cagtttccaggtttcagggatg-3′ (forward) and 5′-ctggttcttgggaatggagttg-3′(reverse); neogenin1, 5′-gggcaactccaaagatctcaa-3′ (forward) and 5′-tgaaaggtcagtggtgcaaga-3′ (reverse). The following conditions were used for amplification of netrin1a and netrin1b: denaturation at 94°C for 30 sec, annealing at 67°C for 30 sec, and extension at 72°C for 60 sec, 25 cycles. The conditions used to amplify netrin2, dcc, and neogenin1 were denaturation at 94°C for 30 sec, annealing at 58°C for 30 sec, and extension at 72°C for 60 sec, 25 cycles. The conditions used to amplify netrin4 were denaturation at 94°C for 30 sec, annealing at 61°C for 30 sec, and extension at 72°C for 60 sec, 25 cycles or 35 cycles.

Whole-Mount RNA In Situ Hybridization

Staging of embryos and whole-mount in situ hybridizations were performed as described previously (Lee et al., 2001). Briefly, antisense digoxigenin-labeled riboprobes were synthesized from the linearized plasmids encoding netrin2 and netrin4 cDNA. After in situ hybridization, images were taken using a Leica digital camera. Two-color in situ hybridization was performed as described previously with fluorescein- and digoxigenin-labeled probes (Jowett, 2001).

Acknowledgments

We thank Dr. Tatjana Piotrowski, Dr. Richard Dorsky, Arminda Suli, and Michael Jurynec for advice and technical support. The krox20 plasmid was kindly provided by Dr. David Grunwald’s laboratory. D.Y.L. was funded by the NIH and the American Cancer Society; K.W.P. and D.Y.L. were funded by the American Heart Association; and C.B.C. was funded by the NIH/NEI.

Grant sponsor: the NIH; Grant sponsor: American Heart Association; Grant sponsor: American Cancer Society; Grant sponsor: NIH/NEI.

Footnotes

The Supplementary Material referred to in this article can be found at http://www.interscence.wiley.com/jpages/1058-8388/suppmat

References

- Arakawa H. Netrin-1 and its receptors in tumorigenesis. Nat Rev Cancer. 2004;4:978–987. doi: 10.1038/nrc1504. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fazeli A, Dickinson SL, Hermiston ML, Tighe RV, Steen RG, Small CG, Stoeckli ET, Keino-Masu K, Masu M, Rayburn H, Simons J, Bronson RT, Gordon JI, Tessier-Lavigne M, Weinberg RA. Phenotype of mice lacking functional Deleted in colorectal cancer (DCC) gene. Nature. 1997;386:796–804. doi: 10.1038/386796a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hamelin M, Zhou Y, Su MW, Scott IM, Culotti JG. Expression of the UNC-5 guidance receptor in the touch neurons of C. elegans steers their axons dorsally. Nature. 1993;364:327–330. doi: 10.1038/364327a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harris R, Sabatelli LM, Seeger MA. Guidance cues at the Drosophila CNS midline: identification and characterization of two Drosophila Netrin/UNC-6 homologs. Neuron. 1996;17:217–228. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(00)80154-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hedgecock EM, Culotti JG, Hall DH. The unc-5, unc-6, and unc-40 genes guide circumferential migrations of pioneer axons and mesodermal cells on the epidermis in C. elegans. Neuron. 1990;4:61–85. doi: 10.1016/0896-6273(90)90444-k. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hjorth JT, Gad J, Cooper H, Key B. A zebrafish homologue of deleted in colorectal cancer (zdcc) is expressed in the first neuronal clusters of the developing brain. Mech Dev. 2001;109:105–109. doi: 10.1016/s0925-4773(01)00513-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hong K, Hinck L, Nishiyama M, Poo MM, Tessier-Lavigne M, Stein E. A ligand-gated association between cytoplasmic domains of UNC5 and DCC family receptors converts netrin-induced growth cone attraction to repulsion. Cell. 1999;97:927–941. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)80804-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ishii N, Wadsworth WG, Stern BD, Culotti JG, Hedgecock EM. UNC-6, a laminin-related protein, guides cell and pioneer axon migrations in C. elegans. Neuron. 1992;9:873–881. doi: 10.1016/0896-6273(92)90240-e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jowett T. Double in situ hybridization techniques in zebrafish. Methods. 2001;23:345–358. doi: 10.1006/meth.2000.1147. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Keino-Masu K, Masu M, Hinck L, Leonardo ED, Chan SS, Culotti JG, Tessier-Lavigne M. Deleted in Colorectal Cancer (DCC) encodes a netrin receptor. Cell. 1996;87:175–185. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)81336-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kennedy TE, Serafini T, de la Torre JR, Tessier-Lavigne M. Netrins are diffusible chemotropic factors for commissural axons in the embryonic spinal cord. Cell. 1994;78:425–435. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(94)90421-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koch M, Murrell JR, Hunter DD, Olson PF, Jin W, Keene DR, Brunken WJ, Burgeson RE. A novel member of the netrin family, beta-netrin, shares homology with the beta chain of laminin: identification, expression, and functional characterization. J Cell Biol. 2000;151:221–234. doi: 10.1083/jcb.151.2.221. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kruger RP, Lee J, Li W, Guan KL. Mapping netrin receptor binding reveals domains of Unc5 regulating its tyrosine phosphorylation. J Neurosci. 2004;24:10826–10834. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.3715-04.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lauderdale JD, Davis NM, Kuwada JY. Axon tracts correlate with netrin-1a expession in the zebrafish embryo. Mol Cell Neurosci. 1997;9:293–313. doi: 10.1006/mcne.1997.0624. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee JS, Ray R, Chien CB. Cloning and expression of three zebrafish roundabout homologs suggest roles in axon guidance and cell migration. Dev Dyn. 2001;221:216–230. doi: 10.1002/dvdy.1136. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Livesey FJ. Netrins and netrin receptors. Cell Mol Life Sci. 1999;56:62–68. doi: 10.1007/s000180050006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lu X, Le Noble F, Yuan L, Jiang Q, De Lafarge B, Sugiyama D, Breant C, Claes F, De Smet F, Thomas JL, Autiero M, Carmeliet P, Tessier-Lavigne M, Eichmann A. The netrin receptor UNC5B mediates guidance events controlling morphogenesis of the vascular system. Nature. 2004;432:179–186. doi: 10.1038/nature03080. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mazelin L, Bernet A, Bonod-Bidaud C, Pays L, Arnaud S, Gespach C, Bredesen DE, Scoazec JY, Mehlen P. Netrin-1 controls colorectal tumorigenesis by regulating apoptosis. Nature. 2004;431:80–84. doi: 10.1038/nature02788. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mitchell KJ, Doyle JL, Serafini T, Kennedy TE, Tessier-Lavigne M, Goodman CS, Dickson BJ. Genetic analysis of Netrin genes in Drosophila: Netrins guide CNS commissural axons and peripheral motor axons. Neuron. 1996;17:203–215. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(00)80153-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oxtoby E, Jowett T. Cloning of the zebrafish krox-20 gene (krx-20) and its expression during hindbrain development. Nucleic Acids Res. 1993;21:1087–1095. doi: 10.1093/nar/21.5.1087. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Park KW, Crouse D, Lee M, Karnik SK, Sorensen LK, Murphy KJ, Kuo CJ, Li DY. The axonal attractant Netrin-1 is an angiogenic factor. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2004;101:16210–16215. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0405984101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Salminen M, Meyer BI, Bober E, Gruss P. Netrin 1 is required for semicircular canal formation in the mouse inner ear. Development. 2000;127:13–22. doi: 10.1242/dev.127.1.13. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Serafini T, Kennedy TE, Galko MJ, Mirzayan C, Jessell TM, Tessier-Lavigne M. The netrins define a family of axon outgrowth-promoting proteins homologous to C. elegans UNC-6. Cell. 1994;78:409–424. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(94)90420-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Serafini T, Colamarino SA, Leonardo ED, Wang H, Beddington R, Skarnes WC, Tessier-Lavigne M. Netrin-1 is required for commissural axon guidance in the developing vertebrate nervous system. Cell. 1996;87:1001–1014. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)81795-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shen H, Illges H, Reuter A, Stuermer CA. Cloning, expression, and alternative splicing of neogenin1 in zebrafish. Mech Dev. 2002;118:219–223. doi: 10.1016/s0925-4773(02)00255-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Srinivasan K, Strickland P, Valdes A, Shin GC, Hinck L. Netrin-1/neogenin interaction stabilizes multipotent progenitor cap cells during mammary gland morphogenesis. Developmental Cell. 2003;4:371–382. doi: 10.1016/s1534-5807(03)00054-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Strähle U, Fischer N, Blader P. Expression and regulation of a netrin homologue in the zebrafish embryo. Mech Dev. 1997;62:147–160. doi: 10.1016/s0925-4773(97)00657-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang H, Copeland NG, Gilbert DJ, Jenkins NA, Tessier-Lavigne M. Netrin-3, a mouse homolog of human NTN2L, is highly expressed in sensory ganglia and shows differential binding to netrin receptors. J Neurosci. 1999;19:4938–4947. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.19-12-04938.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yebra M, Montogomery AMP, Diaferia GR, Kaido T, Silletti S, Perez B, Just ML, Hildbrand S, Hurford R, Florkiewicz E, Tessier-Lavigne M, Cirulli V. Recognition of the neural chemoattractant netrin-1 by integrins alpha6beta4 and alpha3beta1 regulates epithelial cell adhesion and migration. Dev Cell. 2003;5:695–707. doi: 10.1016/s1534-5807(03)00330-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yin Y, Sanes JR, Miner JH. Identification and expression of mouse netrin-4. Mech Dev. 2000;96:115–119. doi: 10.1016/s0925-4773(00)00369-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]