Abstract

Objective

To investigate the retinal microstructure and lamination of patients affected with X-linked retinoschisis (XLRS) using high-resolution imaging modalities.

Methods

Patients diagnosed as having XLRS underwent assessment. Visual function testing included visual acuity, color vision, and full-field electroretinography. We used a high-resolution Fourier-domain optical coherence tomography (FD-OCT) system (4.5-μm axial resolution; 9 frames/s; 1000 A-scans per frame) combined with a handheld scanner. Macular image evaluation included schisis localization and retinal layer integrity.

Results

Six patients with XLRS and identified mutations in the XLRS1 gene underwent testing. Visual acuity ranged from 0.2 to 1.6 logMAR (logarithm of the minimum angle of resolution). Results of FD-OCT revealed foveal schisis extending from the outer to the inner plexiform layer in 4 of 6 patients. Bullous foveal schisis was associated with younger age. All patients showed extrafoveal schisis within the outer and inner nuclear and ganglion cell layer, alone or in combination. Photoreceptor outer and inner segment layers were disrupted and irregular in all patients.

Conclusions

Retinal dystrophy in XLRS is reflected by morphological changes within the inner and outer retinal layers. Disturbed foveal photoreceptor integrity was identified in all patients. Retinal layer abnormalities correlated with age but did not appear to correlate with visual acuity or genotypic variation.

CASES OF RETINOSCHISIS OR splitting of the retina were mentioned as early as 1898.1 More than 100 years later, our knowledge about X-linked retinoschisis (XLRS) incidence, histopathological features, causative genes, and possible gene-protein interaction has advanced greatly.2 A recent study by Apushkin et al3 suggested that visual acuity does not correspond to the size of cystic areas or retinal thickness as evaluated by time-domain optical coherence tomography (OCT). The question of why patients with XLRS have varying levels of reduced vision remains unanswered.

X-linked retinoschisis is caused by mutations in the XLRS1 gene (OMIM 312700) on Xp22 encoding retinoschisin,4 which is primarily expressed in photoreceptor and bipolar cells.5,6 In histopathological studies by Condon et al7 and Mooy et al,8 results from 2 patients aged 18 and 55 years revealed degenerated or absent photoreceptors and an outer nuclear layer replaced with amorphous material and fibrils within the macular schitic area.7,8

In vivo morphological studies using time-domain OCT have demonstrated schitic changes involving the neuroretinal layers.3,9-13 Detailed analyses, however, have been limited by the image resolution of commercial time-domain instruments. The purpose of the present study using a custom-built, high-speed, high-resolution Fourier-domain OCT (FD-OCT) system was to provide higher-resolution characterization of the retinal layer abnormalities associated with XLRS. We identified schisis of the retina involving various layers in all patients. Subfoveal photo-receptors demonstrated significant structural changes that were not identifiable with lower-resolution techniques.

METHODS

SUBJECTS

Patients diagnosed as having XLRS and an identified mutation in the XLRS1 gene were recruited through the Ocular Genetics Clinic at The Hospital for Sick Children in Toronto, Ontario, Canada. Written informed consent and/or assent was obtained from all participants and/or their guardians. The project was approved by the Research Ethics Board at The Hospital for Sick Children and the institutional review board at the University of California, Davis, and conducted in accordance with the Tenets of Helsinki.

OCULAR FUNCTION AND MORPHOLOGICAL ASSESSMENT

A comprehensive eye evaluation included best-corrected monocular distant visual acuity (using the Early Treatment Diabetic Retinopathy Study Chart),14 color vision testing (using Hardy-Rand-Rittler pseudoisochromatic plates with a standard illumination), full-field electroretinography (ERG) (using the International Society for Clinical Electrophysiology of Vision standard),15 and a dilated fundus examination. Molecular genetic analysis was provided as a clinical service in part by the Kellogg Eye Center at the University of Michigan, Ann Arbor, and by GeneDx, Inc, Gaithersburg, Maryland.

FOURIER-DOMAIN OCT

In vivo high-resolution retinal image acquisition was performed using a high-speed, high-resolution FD-OCT16,17 system (axial resolution, 4.5 μm; acquisition speed, 9 frames/s, 1000 A-scans per frame) constructed at the University of California, Davis, Medical Center,18 combined with a sample arm handheld scanner (Bioptigen Inc, Durham, North Carolina). Horizontal scans of 6 mm were obtained through the macular area. After scanning, we processed the images as described in detail elsewhere.19,20 Retinal layers were identified on the basis of previously published data19 and compared with control data as shown in Figure 1. Retinal structure analysis was performed on at least 3 macular scans through the fovea of each eye. Each scan was analyzed for schisis location within the foveal and extrafoveal area and the integrity of the photoreceptor inner and outer segment layers. Particular interest was paid to the interface between the cone photoreceptors and the retinal pigment epithelium (RPE), which creates a virtual membrane owing to a change in refractive index. We have tentatively labeled this the Verhoeff membrane20 based on light21 and electron22 microscopy findings.

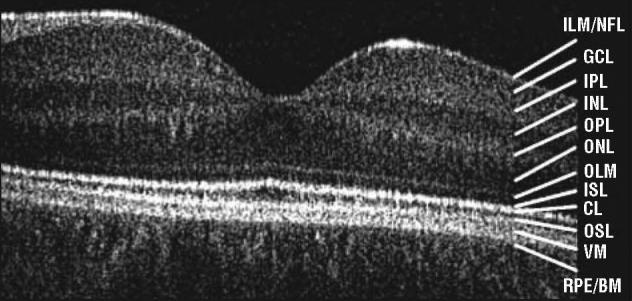

Figure 1.

A 5-mm horizontal Fourier-domain optical coherence tomography image obtained through the right macula of a control subject aged 16 years. CL indicates connecting cilia; GCL, ganglion cell layer; ILM/NFL, internal limiting membrane/nerve fiber layer; INL, inner nuclear layer; IPL, inner plexiform layer; ISL, inner segment layer; OLM, outer limiting membrane; ONL, outer nuclear layer; OPL, outer plexiform layer; OSL, outer segment layer; RPE/BM, retinal pigment epithelium/Bruch membrane; and VM, Verhoeff membrane.

RESULTS

Six male patients, with an identified mutation in the XLRS1 gene and ranging in age from 12 to 38 years, underwent testing (Table). Patients 1 and 3 were siblings. Visual acuity ranged from 0.20 to 1.60 logMAR. Patient 6 had had nystagmus since early childhood. Red/green and blue/yellow color vision defects were detected in 3 patients. Fundus changes included macular schisis (4 patients), blunted macular reflex (1 patient), atrophic macular changes (1 patient), and peripheral schisis (2 patients). The ERG responses showed an abnormal ratio of b to a waves in all patients (data not shown). Five of the 6 mutations were located in exon 4 or exon 6, which encodes the discoidin domain. These mutations resulted in missense substitution23 (the retinoschisis database is available at http://www.dmd.nl/rs/). In patient 6, 1 mutation led to a splicing defect (Table). Vision function and genotypes are summarized in the Table.

Table.

Ocular Phenotype and FD-OCT Findings of Patients Studied

| FD-OCT Macular Findings |

|||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Layers Involved in Schisis |

|||||||||

| Patient No./ Age, y |

XLRS1 Mutation |

OD/OS VA, logMAR |

Color Defectc |

Fundus Findings | Foveal Schisis |

Foveal | Extrafoveal | Foveal OSL/ISL |

Verhoeff Membrane |

| Abbreviations: FD-OCT, Fourier-domain optical coherence tomography; GCL, ganglion cell layer; INL, inner nuclear layer; IPL, inner plexiform layer; ISL, inner segment layer; NA, not able to perform test; ONL, outer nuclear layer; OPL, outer plexiform layer; OSL, outer segment layer; VA, visual acuity; XLRS, X-linked retinoschisis; ellipses, not applicable. | |||||||||

| 1/12a | Pro203Leu | 0.34/0.42 | Normal | Macular schisis | Bullous | IPL to OPL | ONL/INL/GCL | Irregular | Present, extrafoveal |

| 2/14 | Arg200Cys | 0.30/0.64 | Medium | Macular schisis | Laminar/bullous | IPL to OPL | ONL/INL/GCL | Irregular | Absent |

| 3/15a | Pro203Leu | 0.88/0.72 | Normal | Macular schisis | Bullous | IPL to OPL | ONL/INL/GCL | Irregular | Absent |

| 4/18 | Arg213Gln | 0.60/0.80 | Strong | Macular schisis | Bullous | IPL to OPL | ONL/INL/GCL | Irregular | Absent |

| 5/33 | Arg102Tryp | 0.20/0.42 | Strong | Blunt macular reflex, peripheral schisis | None | … | INL | Thinned | Absent |

| 6/38b | IVS1-34A→G | 1.00/1.60 | NA | Macular atrophic, peripheral schisis | None | … | INL | Thinned | Absent |

Indicates siblings.

Patient had nystagmus.

Red/green and blue/yellow color discrimination determined by means of Hardy-Rand-Rittler pseudoisochromatic plates using standard illumination.

Analysis of the FD-OCT scans showed a foveal schisis with different morphological findings in 8 of 12 eyes (4 of 6 patients). The appearance of the foveal schisis was bullous and symmetrical in all but 1 patient (Figure 2A). Patient 2 demonstrated an asymmetric macular morphological change with laminar and bullous foveal schisis in the right and left eye, respectively (Figure 2B). The foveal schisis was of varying size, reaching from the outer to the inner plexiform layers and including the inner nuclear layer in all 4 patients. Extrafoveal schisis involved the outer nuclear layer, inner nuclear layer, and the ganglion cell layer in the eyes with foveal schisis (Figure 2A and B). Macular images from 2 patients in their fourth decade of life revealed a flattened fovea without a foveal schisis, but with a smaller extrafoveal schisis within the inner nuclear layer only (Figure 2C). Photoreceptors were present, although the inner and outer segment layer demonstrated irregularity or thinning in all patients. The Verhoeff membrane, the interface between cone photoreceptors and the RPE, was identifiable within the extrafoveal location in only 1 patient (Figure 2A). None of the high-resolution images demonstrated the Verhoeff membrane in the subfoveal area, suggesting disruption within the cone photoreceptors and the RPE.

Figure 2.

Composites of horizontal 6-mm Fourier-domain optical coherence tomography (FD-OCT) images. A, Images from patient 1, aged 12 years (right eye [RE]), and patient 3, aged 15 years (RE); both patients carry a Pro203Leu mutation on XLRS1. Bullous foveal schisis extends from the outer to the inner plexiform layer (OPL). Extrafoveal schisis is located within the outer (ONL) and inner nuclear layers (INL) and the ganglion cell layer (GCL). Foveal photoreceptor inner (ISL) and outer (OSL) segment layers are disrupted in both scans. The Verhoeff membrane (VM) (arrowhead [patient 1]) is visible only extrafoveally. B, Images from the RE and left eye (LE) of patient 2, aged 14 years, who carries an Arg200Cys mutation on XLRS1. Asymmetry of foveal schisis is evident with laminar schisis (RE) and bullous schisis (LE) extending from the OPL to the IPL. Extrafoveal schisis is similar to that seen in part A. Subfoveal photoreceptor ISL and OSL are markedly disrupted (oval). C, Images from patient 5, aged 33 years (RE), who carries an Arg102Tryp mutation on XLRS1, and patient 6, aged 38 years (LE), who carries an IVS1-34A→G mutation. In both images, the macula shows extrafoveal flattened schisis within the ONL only. More severe photoreceptor ISL and OSL integrity changes are evident (ovals).

REPORT OF CASES

Two patients representing the clinical variability observed are discussed in further detail.

Patient 1

A boy aged 12 years was diagnosed as having XLRS 1 year before FD-OCT testing. The patient had been aware of reduced vision since he was 7 years of age. Clinical diagnosis of XLRS was established because of the characteristic fundus appearance with macular schisis, an electronegative ERG waveform response, and similar findings in his older brother (patient 3). Diagnosis was confirmed by a missense mutation (Pro203Leu) in the XLRS1 gene, which has been reported previously (retinoschisis database). The FD-OCT horizontal images through the macula demonstrated a bullous foveal schisis within the outer nuclear layer. Extrafoveal areas showed a schisis involving the inner and outer nuclear layers and the ganglion cell layer. Photoreceptor inner and outer segments appeared irregular subfoveally. The Verhoeff membrane was visible in the extrafoveal area but disrupted subfoveally (Figure 2A).

Patient 5

A patient aged 33 years had been diagnosed as having macular schisis in childhood. The left eye was treated with focal cryotherapy for a peripheral retinal tear at 18 years of age. Visual acuity was 0.2 and 0.4 logMAR in the right and left eyes, respectively. The ERG responses at 31 years of age showed an electronegative waveform with reduced and delayed cone responses in both eyes. Results of the last fundus examination revealed a flat-appearing macula with minor RPE changes and extramacular temporal schisis in both eyes. Horizontal scans through the macula showed areas of schisis within the inner nuclear layer in the extrafoveal area only. No schisis was evident within the fovea. The outer and inner nuclear layers appeared with an irregular structure. The photoreceptor inner and outer segment layers were thinner than in the younger patients. The Verhoeff membrane was not identifiable in multiple images of both eyes, suggesting photoreceptor disruption.

COMMENT

In vivo characterization of retinal structures in XLRS was performed using high-speed, high-resolution FD-OCT, to our knowledge for the first time. We were able to demonstrate detailed photoreceptor abnormalities in all 6 patients, which has not been possible previously because of resolution limitations. Mutations in the XLRS1 gene result in loss of function in the protein retinoschisin. The RS1 protein, primarily expressed in photoreceptor and bipolar cells, is thought to maintain cell-cell interactions between photoreceptor synapses and bipolar cells. Curat et al24 indicated that the highly conserved discoidin domain within XLRS1 might be essential for collagen binding similar to “molecular” glue, strengthening adhesions of inner and outer retinal layers. In vivo images obtained by FD-OCT are supportive of this theory, with identified schisis and retinal bridges between schitic areas. Retinoschisis was evident in 3 retinal layers depending on the macular location of the scan and the patient's age. Younger patients with visible macular schisis, noted during ophthalmoscopic examination, demonstrated schitic changes within the outer and inner nuclear and ganglion cell layers. In contrast, images obtained in patients in their fourth decade of life showed clinically flattened or atrophic-appearing maculae associated with smaller schisis within fewer retinal layers outside the fovea. These findings are in agreement with previous clinical descriptions of macular schisis flattening with age.25,26

Photoreceptor inner and outer segment layers, including the Verhoeff membrane, were affected in all patients tested, which confirm previous histopathological studies.7,8,27 Retinal histopathology of an enucleated eye from an 18-year-old patient with complicated retinoschisis revealed splitting in the nerve fiber layer, detachment of the inner limiting membrane, and proliferative and degenerative RPE changes. Photoreceptors and the outer nuclear layer at the posterior pole showed atrophy. The macular outer plexiform and nuclear layers exhibited degenerative changes.8 Using histopathological examination in a 55-year-old patient with XLRS, Condon et al7 showed macular blending of the inner and outer nuclear layers with partial obliteration of the outer plexiform layer, degenerated or focally absent photoreceptors, and focal proliferative and degenerative changes within the RPE layer. Findings similar to our results and those of histopathological studies are also observed in murine XLRS, that is, schisis within the inner retina up to the nerve fiber layer, retinal layer disorganization with photoreceptor nuclei reduction, and absence of photoreceptor outer segments in some cases.28 Most recent electron microscopy data in rs1−/y mice suggest that loss of retinoschisin leads to the disruption of inner segment architecture and the displacement and disorganization of photoreceptors.29 Khan et al30demonstrated normal photoreceptor function in patients aged 14 to 47 years with XLRS1 mutations. Whether changes within the photoreceptor layers, as shown in our work and in histopathological studies, are primary or secondary still needs to be determined.

X-linked retinoschisis is usually diagnosed clinically on the basis of typical fundus findings associated with stable visual acuity and, quite often, positive family history. Variable expressivity of XLRS1 with minor visual acuity changes may delay diagnosis or even lead to mis-diagnosis. Morphological and functional tests are important for properly defining the diagnosis and natural history. The ERG response with an electronegative waveform (found in all of our study patients) and the lack of progression were thought to be pathognomonic for XLRS. Recent reports of genetically confirmed XLRS without an electronegative ERG waveform13,31 require additional investigative tools such as high-resolution imaging techniques to clarify the diagnosis and to determine the longitudinal disease outcome. Our FD-OCT description supports previous histopathological studies and proves to be a useful tool in the characterization of the XLRS phenotype. The OCT findings and ERG responses, together with the fundus appearance and family history, are key variables for defining disease progression correctly and for focusing molecular-genetic diagnostics.

A larger sample size is required to establish the geno-type-phenotype correlation. One patient carrying a mutation with a possible splicing effect exhibited a more severe phenotype with nystagmus and severely reduced visual acuity. Retinal morphological changes also indicated a greater extent of photoreceptor layer abnormalities than in the other patients with milder phenotypes. Functional studies are needed to verify the implication of this change.

In conclusion, in vivo high-resolution imaging modalities revealed photoreceptor abnormalities and schisis within the various retinal layers of patients with the XLRS1 mutation. Further studies with more advanced imaging techniques such as adaptive optics OCT19 might give more insight into ultrastructural retinal changes associated with XLRS1 mutations. Retinal layer characterization, in particular photoreceptor abnormalities, in patients with XLRS will be useful in the design of novel treatment modalities.32

Acknowledgments

Funding/Support: The study was supported by the Mira Godard Fund (Dr Héon), The Hospital for Sick Children Research Institute's Restracomp Fund (Dr Gerth), grant NEI 014743 from the National Institutes of Health (Dr Werner), and the Albrecht Fund (Dr Werner) in collaboration with Bioptigen, Inc.

Footnotes

Additional Contributions: Alex Levin, MD, recruited patients; Yesmino Elia, MSc, coordinated the study; Carole Panton, OC (C), provided editorial comments; and Tom Wright, BSc, helped with data analysis. We thank the patients and their families, who made this study possible.

Financial Disclosure: None reported.

REFERENCES

- 1.Haas J. Ueber das Zusammenvorkommen von Veraenderungen der Retina und Chorioidea. Archive Augenheilkunde. 1898;37:343–348. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Tantri A, Vrabec TR, Cu-Unjieng A, Frost A, Annesley WH, Jr, Donoso LA. X-linked retinoschisis: a clinical and molecular genetic review. Surv Ophthalmol. 2004;49(2):214–230. doi: 10.1016/j.survophthal.2003.12.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Apushkin MA, Fishman GA, Janowicz MJ. Correlation of optical coherence tomography findings with visual acuity and macular lesions in patients with X-linked retinoschisis. Ophthalmology. 2005;112(3):495–501. doi: 10.1016/j.ophtha.2004.08.027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Sauer CG, Gehrig A, Warneke-Wittstock R, et al. Positional cloning of the gene associated with X-linked juvenile retinoschisis. Nat Genet. 1997;17(2):164–170. doi: 10.1038/ng1097-164. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Molday LL, Hicks D, Sauer CG, Weber BH, Molday RS. Expression of X-linked retinoschisis protein RS1 in photoreceptor and bipolar cells. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2001;42(3):816–825. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Reid SN, Akhmedov NB, Piriev NI, Kozak CA, Danciger M, Farber DB. The mouse X-linked juvenile retinoschisis cDNA: expression in photoreceptors. Gene. 1999;227(2):257–266. doi: 10.1016/s0378-1119(98)00578-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Condon GP, Brownstein S, Wang NS, Kearns JA, Ewing CC. Congenital hereditary (juvenile X-linked) retinoschisis: histopathologic and ultrastructural findings in three eyes. Arch Ophthalmol. 1986;104(4):576–583. doi: 10.1001/archopht.1986.01050160132029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Mooy CM, Van Den Born LI, Baarsma S, et al. Hereditary X-linked juvenile retinoschisis: a review of the role of Müller cells. Arch Ophthalmol. 2002;120(7):979–984. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Azzolini C, Pierro L, Codenotti M, Brancato R. OCT images and surgery of juvenile macular retinoschisis. Eur J Ophthalmol. 1997;7(2):196–200. doi: 10.1177/112067219700700214. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Chan WM, Choy KW, Wang J, et al. Two cases of X-linked juvenile retinoschisis with different optical coherence tomography findings and RS1 gene mutations. Clin Experiment Ophthalmol. 2004;32(4):429–432. doi: 10.1111/j.1442-9071.2004.00820.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Greene JM, Shakin EP. Optical coherence tomography findings in foveal schisis. Arch Ophthalmol. 2004;122(7):1066–1067. doi: 10.1001/archopht.122.7.1066. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Eriksson U, Larsson E, Holmstrom G. Optical coherence tomography in the diagnosis of juvenile X-linked retinoschisis. Acta Ophthalmol Scand. 2004;82(2):218–223. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0420.2004.00227.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Eksandh L, Andreasson S, Abrahamson M. Juvenile X-linked retinoschisis with normal scotopic b-wave in the electroretinogram at an early stage of the disease. Ophthalmic Genet. 2005;26(3):111–117. doi: 10.1080/13816810500228688. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ferris FL, III, Kassoff A, Bresnick GH, Bailey I. New visual acuity charts for clinical research. Am J Ophthalmol. 1982;94(1):91–96. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Marmor MF, Holder GE, Seeliger MW, Yamamoto S. International Society for Clinical Electrophysiology of Vision. Standard for clinical electroretinography (2004 update) Doc Ophthalmol. 2004;108(2):107–114. doi: 10.1023/b:doop.0000036793.44912.45. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Wojtkowski M, Leitgeb R, Kowalczyk A, Bajraszewski T, Fercher AF. In vivo human retinal imaging by Fourier domain optical coherence tomography. J Biomed Opt. 2002;7(3):457–463. doi: 10.1117/1.1482379. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Nassif N, Cense B, Park BH, et al. In vivo human retinal imaging by ultrahigh-speed spectral domain optical coherence tomography. Opt Lett. 2004;29(5):480–482. doi: 10.1364/ol.29.000480. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Zawadzki RJ, Bower BA, Zhao M, et al. Exposure time dependence of image quality in high-speed retinal in vivo Fourier-domain OCT. In: Manns F, Soederberg PG, Ho A, Stuck BE, Belkin M, editors. Ophthalmic Technologies XV. International Society for Optical Engineering; Bellingham, Wash: 2005. pp. 45–52. Proceedings of SPIE; vol 5688. doi:10.1117/12.591660. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Zawadzki RJ, Jones SM, Olivier SS, et al. Adaptive-optics optical coherence tomography for high-resolution and high-speed 3D retinal in-vivo imaging. Opt Express. 2005;13(21):8532–8546. doi: 10.1364/opex.13.008532. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Zawadzki RJ, Fuller AR, Wiley DF, Hamann B, Choi SS, Werner JS. Adaptation of a support vector machine algorithm for segmentation and visualization of retinal structures in volumetric optical coherence tomography data sets. J Biomed Opt. 2007;12(4):041206. doi: 10.1117/1.2772658. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Rodieck RW. The Vertebrate Retina: Principles of Structure and Function. WH Freeman; San Francisco, CA: 1973. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Anderson DH, Fisher SK, Steinberg RH. Mammalian cones: disc shedding, phagocytosis, and renewal. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 1978;17(2):117–133. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.The Retinoschisis Consortium Functional implications of the spectrum of mutations found in 234 cases with X-linked juvenile retinoschisis. Hum Mol Genet. 1998;7(7):1185–1192. doi: 10.1093/hmg/7.7.1185. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Curat CA, Eck M, Dervillez X, Vogel WF. Mapping of epitopes in discoidin domain receptor 1 critical for collagen binding. J Biol Chem. 2001;276(49):45952–45958. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M104360200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Forsius H, Krause U, Helve J, et al. Visual acuity in 183 cases of X-chromosomal retinoschisis. Can J Ophthalmol. 1973;8(3):385–393. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Roesch MT, Ewing CC, Gibson AE, Weber BH. The natural history of X-linked retinoschisis. Can J Ophthalmol. 1998;33(3):149–158. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Manschot WA. Pathology of hereditary juvenile retinoschisis. Arch Ophthalmol. 1972;88(2):131–138. doi: 10.1001/archopht.1972.01000030133002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Weber BH, Schrewe H, Molday LL, et al. Inactivation of the murine X-linked juvenile retinoschisis gene, Rs1 h, suggests a role of retinoschisin in retinal cell layer organization and synaptic structure. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2002;99(9):6222–6227. doi: 10.1073/pnas.092528599. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Vijayasarathy C, Takada Y, Zeng Y, Bush RA, Sieving PA. Retinoschisin is a peripheral membrane protein with affinity for anionic phospholipids and affected by divalent cations. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2007;48(3):991–1000. doi: 10.1167/iovs.06-0915. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Khan NW, Jamison JA, Kemp JA, Sieving PA. Analysis of photoreceptor function and inner retinal activity in juvenile X-linked retinoschisis. Vision Res. 2001;41(28):3931–3942. doi: 10.1016/s0042-6989(01)00188-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Sieving PA, Bingham EL, Kemp J, Richards J, Hiriyanna K. Juvenile X-linked retinoschisis from XLRS1 Arg213Trp mutation with preservation of the electroretinogram scotopic b-wave. Am J Ophthalmol. 1999;128(2):179–184. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9394(99)00144-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Zeng Y, Takada Y, Kjellstrom S, et al. RS-1 gene delivery to an adult Rs1 h knockout mouse model restores ERG b-wave with reversal of the electronegative waveform of X-linked retinoschisis. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2004;45(9):3279–3285. doi: 10.1167/iovs.04-0576. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]