Abstract

(NZW × BXSB)F1 mice (W/BF1 mice) have been reported to be a type of autoimmune-prone mice, showing symptoms of proteinuria, anti-DNA antibodies and anti-platelet antibodies. In this paper, we report that W/BF1 mice show hyperproduction of tumour necrosis factor (TNF)-α, responding to lipopolysaccharide (LPS) in comparison with normal mice, resulting in induction of death. In normal mice, monocytes/macrophages (Mo/MØ) are the main producer of TNF-α, while both Mo/MØ and dendritic cells (DCs) produce TNF-α in W/BF1 mice. Because the number of DCs is higher in W/BF1 mice, the main producers of TNF-α in W/BF1 mice are thought to be DCs. Moreover, administration of anti-TNF-α antibodies rescued the W/BF1 mice from death induced by LPS, suggesting that TNF-α is crucial for the effect of LPS. Although there is no significant difference in the expression of Toll-like receptor-4 (TLR-4) on DCs between B6 and W/BF1 mice, nuclear factor kappa b activity of DCs from W/BF1 mice is augmented under stimulation of LPS in comparison with that of normal mice. These results suggest that the signal transduction from TLR-4 is augmented in W/BF1 mice in comparison with normal mice, resulting in the hyperproduction of TNF-α and reduced survival rate. The results also suggest that not only the quantity of endotoxin, but also the host conditions, the facility to translate signal from TLR, and so on, could reflect the degree of bacterial infections and prognosis.

Keywords: lipopolysaccharide, (NZW × BXSB)F1 mice (W/BF1 mice), TNF-α, Toll-like receptor

Introduction

The Toll-like receptors (TLRs) play a crucial role in early host defence against invading pathogens [1,2]. TLRs exist on various types of cells [monocytes/macrophages (Mo/MØ), dendritic cells (DCs), neutrophils and other haematopoietic and non-haematopoietic cells] and detect specific pathogens, resulting in the induction of innate immunity. TLR-4 has been reported to be a receptor for lipopolysaccharide (LPS), which consists of a cell wall of Gram-negative rods. It has also been reported that the hyporesponsiveness to LPS in C3H/HeJ mice is due to point mutation of the gene encoding TLR-4, resulting in low-level production of tumour necrosis factor (TNF)-α induced by LPS [3]. In the current concept, septic shock is due to hypercytokinaemia induced by inflammation [4]. In septic shock induced by Gram-negative rods, LPS binds to TLR-4 and causes inflammatory cells to release cytokines such as TNF-α, interleukin (IL)-1 and IL-6 [5].

(NZW × BXSB)F1 mice (W/BF1 mice) have been reported to be a type of autoimmune-prone mice [6]. Although histological and immunological manifestations of W/BF1 mice resemble those of human systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE), male mice show earlier onset of the autoimmune disease and more severe symptoms than females, this being the reverse of human SLE patients. The phenomena are accounted for by the existence of the Yaa gene, which resides on the Y chromosome and accelerates autoimmune diseases [7]. W/BF1 mice show not only lupus nephritis and anti-DNA antibodies but also cardiac infarction, leucocytosis, hypertension, anti-cardiolipin antibodies and anti-platelet antibodies [6,8,9]. We have reported previously that the number of DCs increases in not only peripheral blood but also various organs of W/BF1 mice, and that the increased number of DCs could be related to the production of autoantibodies, at least anti-platelet antibodies [10].

In this paper, we show that W/BF1 mice are more sensitive to LPS than normal mice because of hyperproduction of TNF-α, and that DCs are the main producers of TNF-α in W/BF1 mice.

Materials and methods

Mice

Female NZW mice and male BXSB mice were purchased from SLC (Shizuoka, Japan), and were inbred to obtain male W/BF1 mice. Otherwise, male W/BF1 mice were purchased from SLC. Male W W/BF1 mice more than 12 weeks old, which showed more than (++) proteinuria (Albustix®, Bayer Medical Ltd, Tokyo, Japan), were used for this experiment. Age-matched male C57/BL6 mice were purchased from SLC.

Administration of LPS and anti-TNF-α antibody to mice

The LPS, purchased from Sigma Chemical Co. (St Louis, MO, USA), was injected into the peritoneal cavity of the mice. Anti-TNF-α antibody (0·3 mg; Pierce Biotechnology Inc., Rockford, IL, USA) was administered 10 min before the LPS.

Histological analyses

W/BF1 mice were killed 12 h after LPS injection (15 mg/kg) and their organs were then fixed with buffered formalin. Haematoxylin and eosin staining and terminal deoxynucleotidyl transferase mediated dUTP nick end labelling (TUNEL) assay of the organs were carried out. For the TUNEL assay, we used the in situ apoptosis detection kit (Takara, Otsu, Japan).

Reverse transcription–polymerase chain reaction to examine mRNA expression of TNF-α in spleen cells

cDNA from freshly isolated and cultured spleen cells was prepared as described previously [11]. After adjusting the quantity of cDNA, polymerase chain reaction was carried out using the cDNA and glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase-specific primers (Toyobo, Tokyo, Japan) or mouse TNF-α-specific primers (Maxim Biotech, Inc., San Francisco, CA, USA).

Preparation of DCs and Mo/MØ from spleen

For the preparation of DCs and Mo/MØ, a single-cell suspension was prepared from spleen cells of W/BF1 mice and B6 mice, as described previously [10]. The cells were incubated with anti-CD11c coated MACS® magnetic microbeads (Miltenyi Biotec, Bergisch Gladbach, Germany). After 15 min incubation at 8°C, the cells were passed through a magnetic affinity cell sorter midi column (Miltenyi Biotec) to obtain a CD11c+ enriched fraction from the cells. The positively selected cells were stained with phycoerythrin (PE)-labelled anti-CD11c (PharMingen, San Diego, CA, USA), TC-labelled anti-CD3 (Caltag Laboratories, Burlingame, CA, USA) and TC-labelled anti-CD19 (Caltag Laboratories). To obtain purified CD11c+CD3-CD19- cells, the cells were sorted using EPICS ALTRA™ (Coulter, Hialeah, FL, USA). More than 90% of the sorted cells were CD11c, and the cells were used as DCs in this experiment. The cells which passed through the column were incubated with anti-CD11b-coated MACS® magnetic microbeads (Miltenyi Biotec) for 15 min at 8°C. The cells were then incubated further with fluorescein isothiocyanate (FITC)-labelled anti-Mac1, PE-labelled anti-CD11c, TC-labelled anti-CD3 and TC-labelled anti-CD19 antibodies. To obtain Mac1+CD11c-CD3-CD19- cells, the cells were sorted using EPICS ALTRA™. More than 90% of the sorted cells were Mac1+CD11c-CD3-CD19-, and the cells were used as Mo/MØ in this experiment.

Measurement of concentration of TNF-α in serum and supernatant

Mice serum was collected after the periods indicated from LPS injection (12 mg/kg), while supernatant the cells (2 × 106/ml) was also collected after culture for the periods indicated with or without LPS (1 µg/ml). The serum and supernatant were stored in a freezer until measurement. Concentrations of TNF-α in the serum and supernatant were measured using an enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) kit (R&D Systems, Inc., Minneapolis, MN, USA).

Analyses of production of TNF-α of each population with intracytoplasmic staining of TNF-α

Spleen cells from B6 mice and W/BF1 mice were cultured in 10% fetal calf serum containing RPMI-1640 with LPS (1 µg/ml) with or without Brefeldin A (10 µg/ml; Sigma). After 2 h incubation, the cells were harvested and stained. First, surface staining of the cells with (i) FITC-labelled anti-CD11c, peridinin chlorophyll (PerCP) Cy5·5-labelled anti-CD3 (PharMingen), PerCP Cy5·5-labelled anti-CD19 (PharMingen), plus allophycocyanin (APC)-labelled anti-B220 antibodies for analyses of DCs, B cells and T cells; and (ii) FITC-labelled anti-CD11c, PerCP Cy5·5-labelled anti-CD3 and APC-labelled anti-Mac1for analyses of Mo/MØ, were carried out. Next, intracytoplasmic staining for TNF-α was carried out with PE-labelled anti-TNF-α using IntraPrep® (Immunotech, Beckman Coulter Co., Marseille, France), following the instruction manual. The cells were analysed with BD LSR™ (BD Bioscience Pharmingen, San Jose, CA, USA).

Analyses for expression of TLR-2, TLR-4, CD180 and MD-1

A single-cell suspension was prepared from spleen cells of B6 mice and W/BF1 mice. The cells were stained with FITC-labelled anti-CD11c, PerCP Cy5·5-labelled anti-CD3, PerCP Cy5·5-labelled anti-CD19, APC-labelled anti-B220 or anti-Mac1 antibody and various PE-labelled anti-TLR-related protein antibodies (eBioscience, San Diego, CA, USA), such as anti-TLR-2, anti-TLR-4 (clone UT41 or MTS510), anti-CD180 or anti-MD-1 antibody. PE-labelled isotype matched control antibodies (rat IgG1, rat IgG2a and rat IgG2b antibodies) were obtained from Caltag Laboratories. The expression of TLR-related proteins of DCs was analysed in the gate of CD11c+CD3-CD19- cells. The expression of TLR-related proteins of Mo/MØ was analysed in the gate of Mac1+CD3-CD19-CD11c- cells. The TLR-related protein expression of T cells was analysed in the gate of Mac1-CD3+B220- cells. The TLR-related proteins expression of B cells was analysed in the gate of CD11c-CD19+B220+ cells.

Measurement of nuclear factor kappa B in nuclear extract of cultured DCs with or without LPS

The DCs (1 × 106) from B6 mice and W/BF1 mice were cultured with or without LPS (1 µg/ml) for 15 min. Nuclear extracts were prepared and the amount of nuclear factor kappa B (NF-κB)/p65 was measured using an ELISA kit for NF-κB/p65 (NF-κB/p65 ActiveELISA™; IMAGENEX Corporation, San Diego, CA, USA).

Statistical analyses

Significances were evaluated using Student's t-test, except for the mortality rate. The mortality significances were evaluated using Fisher's exact test. P-values of less than 0·05 were considered to be statistically significant.

Results

Hypersensitivity of W/BF1 mice to LPS

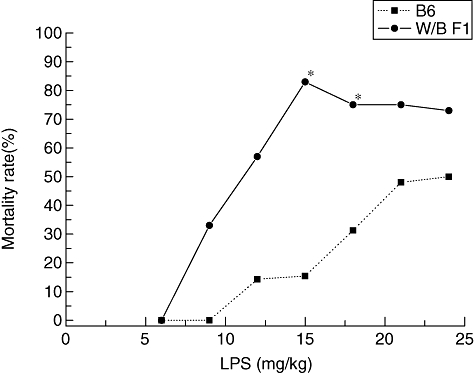

First, to examine the sensitivity of W/BF1 mice to LPS, we injected LPS into the peritoneal cavity of the W/BF1 mice, and B6 mice as control mice, and compared the survival rate. As shown in Fig. 1, the W/BF1 mice died after lower doses of LPS than the B6 mice. With 6 mg/kg LPS administration, all of both W/BF1 mice and B6 mice survived. However, with 9 mg/kg LPS administration, 33% of the W/BF1 mice died, while all B6 mice still survived. With an LPS dose of 15 mg/kg, approximately 83% of the W/BF1 mice died, but only 15% of the B6 mice died. These results suggest that W/BF1 mice are more sensitive to LPS than normal mice. When we also used BALB/c mice as normal control mice, the BALB/c mice showed a similar survival rate to B6 mice (data not shown). We examined the W/BF1 mice histologically, which were injected with 15 mg/kg LPS (see Supplementary material, Fig. S1). The mice showed so-called multiple-organ failure, in which some parenchymal cells and some haemopoetic cells died in each organ. Cell death was confirmed by TUNEL assay (see Supplementary material, Fig. S1).

Fig. 1.

Hypersensitivity of (NZW × BXSB)F1 mice (W/BF1) mice in response to lipopolysaccharide (LPS). Various dosages of LPS were injected into the peritoneal cavity of W/BF1 mice and B6 mice and mortality rates were examined, as described in Materials and methods. In this experiment, LPS usually induced mouse death within 24 h after the injection of LPS. Each group consisted of three to 15 mice (from five to 10 mice in most groups). *P < 0·05 versus B6 mice.

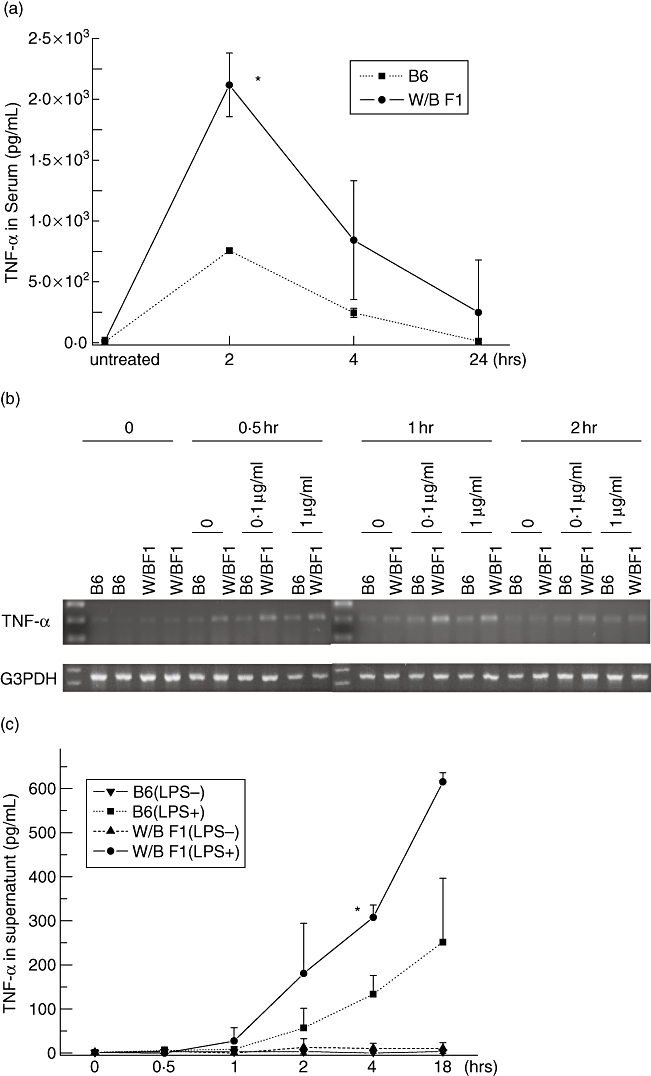

It has been reported that LPS induces production of cytokines such as TNF-α and/or other cytokines, thereby inducing individual death. Therefore, we examined whether LPS can induce TNF-α after LPS injection in mice. As shown in Fig. 2a, serum levels of TNF-α of non-treated W/BF1 mice were low, similar to that of non-treated B6 mice before LPS administration. However, TNF-α reached a peak at 2 h after LPS administration in both the W/BF1 mice and B6 mice. Thereafter, the concentration decreased gradually. Serum concentrations of TNF-α of W/BF1 mice were significantly higher than those of B6 mice after LPS injection. Next, we examined the production of TNF-α from spleen cells in the in vitro assay in mRNA and protein levels under LPS stimulation. As shown in Fig. 2b, the mRNA level of TNF-α was extremely low in spleen cells before culture or cultured cells without LPS in both W/BF1 mice and B6 mice. Cultured spleen cells with LPS showed a higher expression of TNF-α mRNA in both W/BF1 mice and B6 mice. However, the level of TNF-α mRNA of spleen cells from W/BF1 mice was higher at 30 min and 1 h after LPS stimulation than in the B6 mice, and the expression decreased at 2 h after LPSstimulation in both W/BF1 mice and B6 mice. In terms of protein level, spleen cells from both W/BF1 and B6 mice under LPS stimulation showed a higher concentration of TNF-α than unstimulated spleen cells, and spleen cells from W/BF1 mice showed a significantly higher concentration of TNF-α than those of spleen cells from B6 mice under LPS stimulation (Fig. 2c). These results suggest that spleen cells from W/BF1 mice produce much more TNF-α than those of B6 mice in response to LPS.

Fig. 2.

Hyperproduction of tumour necrosis factor (TNF)-α in (NZW × BXSB)F1 mice (W/BF1) mice in response to lipopolysaccharide (LPS). (a) Serum concentrations of TNF-α were examined after LPS injection. Serum concentrations of TNF-α in W/BF1 mice and B6 mice, which were untreated, and after 2, 4 and 24 h after LPS injection (9 mg/kg). *P < 0·05 versus B6 mice. (b) mRNA expression of TNF-α from spleen cells in W/BF1 mice and B6 mice in vitro. Spleen cells were obtained from B6 mice and W/BF1 mice. Spleen cells (2 × 106) were cultured with or without the indicated concentration of LPS. cDNA were prepared from freshly isolated spleen cells and spleen cells cultured for the indicated times. Reverse transcription–polymerase chain reaction was carried out to detect mRNA expression of TNF-α. (c) Concentrations of TNF-α in the supernatants from cultured spleen cells were measured as described in Materials and methods. *P < 0·05 versus spleen cells of B6 mice treated with LPS.

Next, we examined the effects of the TNF-α on murine survival. Namely, we blocked the effects of TNF-α using anti-TNF-α antibody. Ten minutes after intraperitoneal injection of anti-TNF-α antibody into W/BF1 mice, a lethal dosage of LPS (24 mg/kg) was injected into the mice. All the W/BF1 mice (four of four) that had been injected with both the anti-TNF-α antibody and TNF-α survived, suggesting that TNF-α is a crucial factor in LPS-induced death in this system.

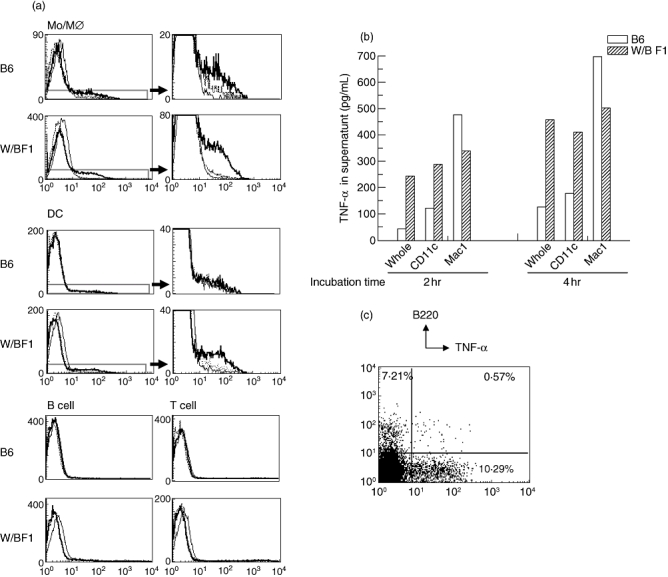

The TNF-α is produced mainly by Mo/MØ in normal mice, while it is produced by both Mo/MØ and DCs in W/BF1 mice

It has been reported that Mo/MØ produce mainly TNF-α under stimulation of LPS. We have also reported previously that the number of DCs increased significantly in W/BF1 mice [10]. Therefore, we examined whether DCs can produce TNF-α in W/BF1 mice. First, we examined the production of TNF-α using the intracytoplasmic staining technique. As shown in Fig. 3a, in B6 mice Mo/MØ could produce TNF-α, but we could not detect the production of TNF-α in DCs even with LPS stimulation. In W/BF1 mice, both Mo/MØ and DCs could produce TNF-α in response to LPS stimulation. We could not detect the production of TNF-α in T cells or B cells in this method in either W/BF1 mice or B6 mice. Next, to confirm the production of TNF-α from DCs, we measured the concentration of TNF-α in the supernatants of in vitro-cultured whole spleen cells, Mo/MØ and DCs (Fig. 3b). In B6 mice, the supernatant obtained from cultured Mo/MØ with LPS showed a much higher concentration of TNF-α than that of DCs, while DCs in W/BF1 mice produced a similar amount of TNF-α to Mo/MØ. It has been reported that DCs can be divided into two subpopulations, such as B220+DCs and B220-DCs [12]. The B220+DCs, which can produce IFN-α, are known as plasmacytoid DCs. Therefore, we examined which DCs could produce TNF-α in W/BF1 mice. As shown in Fig. 3c, CD11c+ cells of W/BF1 mice were analysed further with B220 and intracytoplasmic TNF-α. Approximately 92·2% were B220- and 7·8% were B220+ in DCs of W/BF1 mice. Only 7·9% of B220+ DCs were positive for TNF-α, while 12·5% of B220-DCs were positive for TNF-α. These results suggest that not only Mo/MØ but also DCs produce TNF-α in W/BF1 mice and that B220-DCs produce mainly TNF-α in DCs.

Fig. 3.

Not only monocytes/macrophages (Mo/MØ) but also dendritic cells (DCs) produce tumour necrosis factor (TNF)-α in (NZW × BXSB)F1 mice (W/BF1) mice. (a) Intracytoplasmic staining of TNF-α in Mo/MØ, DCs, T cells and B cells. Intracytoplasmic staining of TNF-α was carried out as described in Materials and methods. Thin lines show isotype-matched antibody, dotted lines show the staining pattern of anti-TNF-α without Brefeldin A, and bold lines show the staining pattern of anti-TNF-α with Brefeldin A. Figures on the right are magnifications of the lower part of figures on the left in the parts of DCs and Mo/MØ. Representative data are shown for three independent experiments. (b) TNF-α production from Mo/MØ and DCs in vitro assay. Purified Mo/MØ and DCs were cultured for the period indicated, followed by measurement of the concentration of TNF-α in the supernatants using enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay. Representative data are shown for two independent experiments. (c) Spleen cells of W/BF1 mice were stained with fluorescein isothiocyanate-labelled anti-CD11c, peridinin chlorophyll (PerCP) Cy5·5-labelled anti-CD3, PerCP Cy5·5-labelled anti-CD19 and allophycocyanin-labelled anti-B220 antibodies, followed by intracytoplasmic staining with phycoerythrin-labelled anti-TNF-α antibody. Cells gated with CD11c+CD3-CD19- cells were analysed. Representative data are shown for two independent experiments.

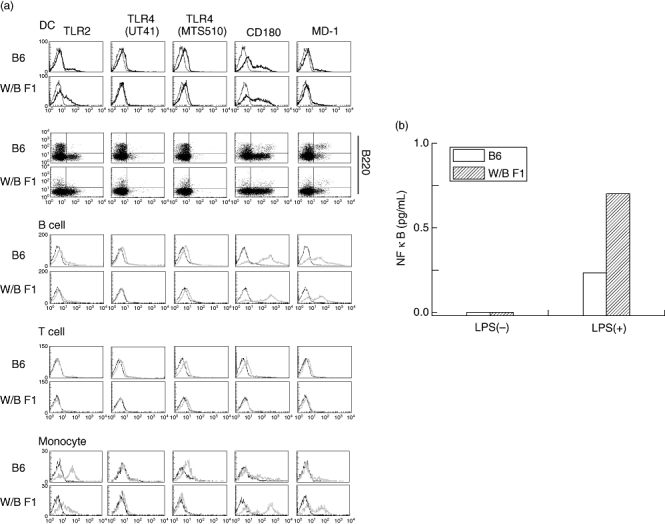

Expression of TLR-4 is not different between DCs of W/BF1 mice and DCs of B6 mice

It has been reported that LPS first binds to TLR-4, followed by activation of the signal transduction-related molecules, resulting in the production of TNF-α[3]. Therefore, we examined the expression of TLR-4 in DCs and macrophages in B6 mice and W/BF1 mice. As shown in Fig. 4a, there was no significant difference between the expression of TLR-4 in DCs in B6 mice and W/BF1 mice. On the other hand, a much greater number of DCs in W/BF1 mice expressed TLR-2, which can detect Gram-positive bacterium Staphylococcus aureus[13], than the DCs in B6 mice. However, in Mo/MØ, more Mo/MØ from B6 mice expressed TLR-2 than Mo/MØ from W/BF1 mice. Next, we examined the activation of NF-κB, which is activated by stimulation from TLR-4, by means of measuring intranuclear NF-κB, as it has been reported that NF-κB activation is related to TNF-α production and that activated NF-κB moves into the nucleus. As shown in Fig. 4b, there are greater quantities of intranuclear NF-κB of DCs in W/BF1 mice than in B6 mice under LPS stimulation. These results suggest that it is the facilitation of the signal transduction pathway from TLR-4 to activation of NF-κB rather than the expression of TLR-4, which is related to the augmentation of TNF-α production in W/BF1 mice.

Fig. 4.

Expression of Toll-like receptor 4 (TLR-4) of dendritic cells (DCs) from (NZW × BXSB)F1 mice (W/BF1) mice is not different from that of normal mice, but the facility of activation of nuclear factor kappa B (NF-κB) in DCs of W/BF1 mice is augmented in comparison with DCs of normal mice. (a) Spleen cells were stained with phycoerythrin-labelled antibodies for TLR-related proteins, fluorescein isothiocyanate-labelled anti-CD11c, peridinin chlorophyll (PerCP) Cy5·5-labelled anti-CD3, PerCP Cy5·5-labelled anti-CD19, allophycocyanin-labelled anti-B220 antibodies. CD11c+CD3-CD19- cells were gated and analysed further with expression of TLR-related proteins. The expression of TLR-related proteins was also analysed in CD19+ cells (B cells), CD3+ cells (T cells) and Mac-1+ CD11c- cells (monocytes/macrophages). Representative data are shown for three independent experiments. (b) Quantities of intranuclear NF-κB in DCs of W/BF1 mice and B6 mice were measured as described in Materials and methods. Representative data are shown for two independent experiments.

Discussion

W/BF1 mice were first reported as a type of lupus mice, showing not only lupus nephritis but also coronary vascular disease [6]. We have also shown several characteristics of W/BF1 mice, such as the appearance of anti-platelet antibodies [9] and anti-cardiolipin antibodies [7], thymic atrophy [14] and increased numbers of DCs [10]. In this paper, we have shown that the hypersensitivity of W/BF1 mice to LPS is due to the hyperproduction of TNF-α and that the DCs of W/BF1 mice can produce quantities of TNF-α. It has been reported that DCs can produce TNF-α in response to LPS [15]. We show that DCs from W/BF1 mice produce much more TNF-α than those of normal mice (Figs 1–3). Therefore, when we take into account the increase in the number of DCs in W/BF1 mice, it is conceivable that mainly DCs, not Mo/MØ, produce TNF-α in W/BF1 mice. The main population producing TNF-α in DCs is not B220+DCs but B220-DCs (Fig. 3).

It has been reported that the cells expressing only TLR-4 cannot respond to LPS but that cells expressing the TLR-4/MD-2 complex can do so [16]. We used two kinds of antibodies to detect TLR-4; clone UT4 and clone MST510. Clone MTS510 can detect the TLR-4/MD-2 complex [17]. We have shown that the expression of TLR-4 in DCs of W/BF1 mice is not augmented in comparison with normal mice (Fig. 4). However, the activation of NF-κB is augmented in DCs of W/BF1 mice (Fig. 4). These facts suggest that the facility of the signal transduction pathway is different between DCs in normal mice and W/BF1 mice. In fact, modifications of the TLR-4 signalling pathway have been reported, and several proteins, which augment or reduce the signal transduction from TLR-4 to NF-κB, have also been identified [18]. Namely, IL-1 receptor-associated serine/threonine kinase M, a short form of MyD88 (MyD88s) and suppressor of cytokine signalling-1 suppresses the activation of NF-κB [19–21], while signal-transducing adaptor protein-2 augments the signal transduction [22]. Therefore, we examined the mRNA expression of these proteins using reverse transcription–polymerase chain reaction. However, the expression of mRNA of these proteins in DCs of W/BF1 mice were no different from those in DCs of normal mice (data not shown). To clarify the mechanisms underlying the hyperactivation of NF-κB of DCs in W/BF1 mice, further exploration is required. We have also addressed the expression of TLR-2, which can detect S. aureus[13]. Far greater numbers of DCs in W/BF1 mice expressed TLR-2 than DCs in B6 mice. However, in Mo/MØ, more Mo/MØ from B6 mice expressed TLR-2 than Mo/MØ from W/BF1 mice. These results suggest that DCs in W/BF1 mice can react not only to Gram-negative bacteria, which produce LPS, but also to Gram-positive S. aureus.

W/BF1 mice are F1 mice induced by female NZW and male BXSB mice. Therefore, we examined which strain of NZW or BXSB mice are susceptible to LPS. We injected 15 mg/kg of LPS into aged male BXSB, which showed lupus nephritis, and age-matched female NZW mice. All NZW mice survived, but three of four of the BXSB mice died, suggesting that not NZW, but BXSB mice, are susceptible to LPS.

Sepsis is one of the main causes of death in SLE patients [23,24]. Although immunosuppressive medications, including corticosteroids and cytotoxic drugs, are critical inlimiting infectious complications in the SLE patients, a high sensitivity to LPS and the facility of signal transduction from TLR in SLE patients have not hitherto been reported. We are carrying out similar experiments using MRL/Mp-lpr/lrp mice, another type of lupus mouse, which show accelerated lupus nephritis because of an abnormality of Fas [25], and have observed a similar high sensitivity to LPS in these mice (manuscript in preparation). Therefore, a high sensitivity to LPS could be common in lupus mice, in at least W/BF1 mice and MRL/lpr mice, in spite of the causes of induction of SLE. We have suggested that the facility of signal transduction from TLR could contribute to the poor prognosis of septic patients in SLE. To clarify this, further studies should be carried out in clinical patients. Although we have also shown that pretreatment with anti-TNF-α rescues mice from death induced by LPS, it has been reported that anti-TNF-α antibodies do not have significant effects on the prognosis of septic shock [26]. However, as described in Fig. 2, we have shown that mRNA of TNF-α reaches a peak 30 min after the injection of LPS and serum TNF-α reaches a peak 2 h after LPS in protein level. These data suggest that secretion of TNF-α begins very rapidly after LPS stimulation. Therefore, it is conceivable that, in clinical studies, TNF-α had already reached a high level and had worked when the anti-TNF-α antibody administration was begun.

In this paper, we have shown that LPS induced the hyperproduction of TNF-α in W/BF1 mice in vivo, and that not only Mo/MØ but also DCs produce TNF-α in W/BF1 mice, resulting from hyperactivation of NF-κB. These results could suggest a mechanism underlying the easy induction of sepsis in SLE patients.

Acknowledgments

We thank Ms Y. Tokuyama, Ms M. Murakami-Shinkawa, Ms S. Miura, Ms K. Hayashi and Ms A. Kitajima for their expert technical assistance, and also Mr Hilary Eastwick-Field and Ms K Ando for the preparation of this manuscript. This study was supported by a grant from the the 21st Century COE Program of the Ministry of Education, Culture, Sports, Science and Technology, the Department of Transplantation for Regeneration Therapy (sponsored by Otsuka Pharmaceutical Company, Ltd), Molecular Medical Science Institute, Otsuka Pharmaceutical Co., Ltd, Japan, Immunoresearch Laboratories Co., Ltd (JIMRO) and Scientific Research (C) 18590388.

Supporting information

Additional Supporting Information may be found in the online version of this article:

The numbers of dead cells and degenerative cells increased in each organ in lipopolysaccharide-injected (NZW × BXSB)F1 mice (W/BF1) mice. In the lung, epithelial cells and haemopoietic cells in particular fell into degeneration and/or cell death. In the spleen many haemopoietic cells, containing lymphoid cells, Mo/MØ and DCs, fell into cell death. In the liver, a part of parenchymal cells fell into acidic change in haematoxylin and eosin staining and many haemopoietic cells fell into apoptosis, but some parenchymal cells also fell into apoptosis. In the kidney, not only haemopoetic cells but also epithelial cells in renal tubules fell into degeneration and apoptosis.

Please note: Blackwell Publishing are not responsible for the content or functionality of any supporting materials supplied by the authors. Any queries (other than missing material) should be directed to the corresponding author for the article.

References

- 1.Janeway CA, Medzhitov R. Innate immune recognition. Annu Rev Immunol. 2002;20:197–216. doi: 10.1146/annurev.immunol.20.083001.084359. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Beutler B, Riestschel ET. Innate immune sensing and its roots: the story of endotoxin. Nat Rev Immunol. 2003;3:169–76. doi: 10.1038/nri1004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Hoshino K, Takeuchi O, Kawai T, et al. Toll-like receptor 4 (TLR4)-deficient mice are hyporesponsive to lipopolysaccharide: evidence for TLR4 as the lps gene product. J Immunol. 1999;162:3749–52. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Morrison DC, Ryan JL. Bacterial endotoxins and host immune responses. Adv Immunol. 1979;28:293–450. doi: 10.1016/s0065-2776(08)60802-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Baumann H, Gauldie J. Acute phase response. Immunol Today. 1994;15:74–80. doi: 10.1016/0167-5699(94)90137-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Hang LM, Izui S, Dixon FJ. NZW × BXSB)F1 hybrid. A model of acute lupus and coronary vascular disease with myocardial infarction. J Exp Med. 1981;154:241–6. doi: 10.1084/jem.154.1.216. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Adachi Y, Inaba M, Amoh Y, et al. Effect of bone marrow transplantation on anti-phospholipid antibody syndrome in murine lupus mice. Immunobiology. 1994;192:218–30. doi: 10.1016/S0171-2985(11)80099-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Hang L, Stephens-Larson P, Henry JP, Dixon FJ. The role of hypertension in the vascular disease and myocardial infarcts associated with murine systemic lupus erythematosus. Arthritis Rheum. 1983;26:1340–5. doi: 10.1002/art.1780261106. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Oyaizu N, Yasumizu R, Miyama-Inaba M, et al. NZW × BXSB)F1 mouse, a new animal model of idiopathic thrombocytopenia purpura. J Exp Med. 1998;167:2017–22. doi: 10.1084/jem.167.6.2017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Adachi Y, Taketani S, Toki J, et al. Marked increase in number of dendritic cells in autoimmune-prone (NZW × BXSB)F1 mice with age. Stem Cells. 2002;20:61–72. doi: 10.1634/stemcells.20-1-61. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Adachi Y, Taketani S, Oyaizu H, Ikebukuro K, Tokunaga R, Ikehara S. Apoptosis of colorectal adenocarcinoma induced by 5-FU and/or IFN-gamma through caspase 3 and caspase 8. Int J Oncol. 1999;15:1191–6. doi: 10.3892/ijo.15.6.1191. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ferrero I, Held W, Wilson A, Tacchini-Cottier F, Radtke F, Macdonald HR. Mouse CD11c(+) B220(+) Gr1(+) plasmacytoid dendritic cells develop independently of the T-cell lineage. Blood. 2002;100:2852–7. doi: 10.1182/blood-2002-01-0214. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Takeuchi O, Hoshino K, Akira S. TLR2-deficient and MyD88-deficient mice are highly susceptible to Staphylococcus aureus infection. J Immunol. 2000;165:5392–6. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.165.10.5392. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Adachi Y, Inaba M, Inaba K, Than S, Kobayashi Y, Ikehara S. Analyses of thymic abnormalities in autoimmune-prone (NAW×BXSB)F1 mice. Immunobiology. 1993;188:340–54. doi: 10.1016/S0171-2985(11)80218-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Pulendran B, Kumar P, Cutler CW, Mohamadzadeh M, Dyke TV, Bancherau J. Lipopolysaccharides from distinct pathogens induce different classes of immune responses in vivo. J Immunol. 2001;167:5067–76. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.167.9.5067. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Shimazu R, Akashi S, Ogata H, et al. MD-2, a molecule that confers lipopolysaccharide responsiveness on Toll-like receptor 4. J Exp Med. 1999;189:1777–82. doi: 10.1084/jem.189.11.1777. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Akashi S, Shimazu R, Ogata H, et al. Cell surface expression and lipopolisaccharide signaling via the Toll-like receptor 4-MD-2 complex on mouse peritoneal macrophages. J Immunol. 2000;164:3471–5. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.164.7.3471. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.De Wit DTonon S, Olislagers V, Goriely S, Boutriaux M, Goldman M, Willems F. Impaired responses to Toll-like receptor 4 and Toll-like receptor 3 ligand in human cord blood. J Autoimmun. 2003;21:277–81. doi: 10.1016/j.jaut.2003.08.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kobayashi K, Hernandez LD, Galan JE, Janeway CA, Jr, Medzhitov R, Flavell RA. IRAK-M is a negative regulator of Toll-like receptor signaling. Cell. 2002;110:191–202. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(02)00827-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Janssens S, Burns K, Tschopp J, Beyaert R. Regulation of interleukin-1- and lipopolysaccharide-induced NF-κB activation by alternative splicing of MyD88. Curr Biol. 2002;12:467–71. doi: 10.1016/s0960-9822(02)00712-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Nakagawa R, Naka T, Tsutsui H, et al. SOCS-1 participates in negative regulation of LPS responses. Immunity. 2002;17:677–87. doi: 10.1016/s1074-7613(02)00449-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Sekine Y, Yumioka T, Yamamoto T, et al. Modulation of Toll-like receptor 4 signaling by a novel adaptor protein STAP-2 in macrophages. J Immunol. 2006;176:380–9. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.176.1.380. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Chen Y-S, Yang Y-H, Lin Y-T, Chiang B-L. Risk of infection in hospitalized children with systemic lupus erythematosus: a 10-year follow-up. Clin Rheumatol. 2004;23:235–8. doi: 10.1007/s10067-004-0877-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kim W, Min J, Lee S, Park S, Kim M. Causes of death in Korea patients with systemic lupus erythematosus: a single center retrospective study. Clin Exp Rheumatol. 1999;17:539–45. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Watanabe-Fukunaga R, Brannan CI, Copeland NG, Jenkins NA, Nagata S. Lymphoproliferation disorder in mice explained by defects in Fas antigen that mediates apoptosis. Nature. 1992;356:314–17. doi: 10.1038/356314a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Bone RC. Why sepsis trials fail. JAMA. 1996;276:565–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

The numbers of dead cells and degenerative cells increased in each organ in lipopolysaccharide-injected (NZW × BXSB)F1 mice (W/BF1) mice. In the lung, epithelial cells and haemopoietic cells in particular fell into degeneration and/or cell death. In the spleen many haemopoietic cells, containing lymphoid cells, Mo/MØ and DCs, fell into cell death. In the liver, a part of parenchymal cells fell into acidic change in haematoxylin and eosin staining and many haemopoietic cells fell into apoptosis, but some parenchymal cells also fell into apoptosis. In the kidney, not only haemopoetic cells but also epithelial cells in renal tubules fell into degeneration and apoptosis.