Abstract

Splenectomy results in an increased risk of sepsis. The autogenous transplant of the spleen is an option for preserving splenic functions after total splenectomy. In this study, the capacity of animals undergoing autogenous spleen transplantation to respond to Staphylococcus aureus infection was investigated. BALB/c mice were divided into three groups: splenectomy followed by autotransplantation in the retroperitonium (AT), splenectomized only (SP) and operated non-splenectomized sham control (CT). Thirty days after surgery the mice were infected intravenously with S. aureus. Splenectomized mice had a higher number of colony-forming units (CFU) of S. aureus in liver and lungs in comparison with either AT or with CT mice (P < 0·05). Higher CFU numbers in lung of SP mice correlated with elevated production of interleukin-10 associated with a lower production of interferon-γ and tumour necrosis factor-α. However, systemically, the level of tumour necrosis factor-α was higher in the SP group than in CT or AT. Lower titres of specific anti-S. aureus immunoglobulin (Ig)M and IgG1 were observed 6 days after infection in SP mice in comparison either with the AT or CT groups. Thus, splenectomy is detrimental to the immune response of BALB/c mice against infection by S. aureus which can be re-established by autogenous implantation of the spleen.

Keywords: antibody response, cytokines, spleen, Staphylococcus aureus, transplantation

Introduction

Misconceptions about the spleen have hindered the development of knowledge about its function and importance for the organism. For a long time the spleen was regarded as a superfluous organ, which could be removed without side effects [1]. A change in attitude began with the description of overwhelming post-splenectomy infection [2]. Overwhelming infection is a serious clinical situation, occurring 58 times more frequently in patients subjected to splenectomy than in the general population, harming mainly children [3]. The adult spleen is perfused with more than 200 ml of blood per minute and functions as a filter that prolongs contact time of blood cells and molecules with splenic phagocytes, thereby facilitating phagocytosis and presentation of foreign antigens [4,5].

Evaluation of the impact of splenic autotransplantation technique is justified due to the high incidence of total splenectomies. The spleen is the organ most affected in closed abdominal trauma, and is also highly susceptible to iatrogenic injuries [6]. Haematological indications for splenectomy result in high incidence of sepsis and death after infection by Pneumococcus, Meningococcus, Escherichia coli, Haemophilus influenza, Staphylococcus and Streptococcus[5,7,8]. The idea of distributing spleen segments into different sites in the abdomen is not new. It is based on splenosis, which is the implantation of splenic tissue fragments resulting from trauma [9].

In order to maintain splenic function, autogenous splenic implantation into various sites including the subcutaneous tissue, retroperitoneum, rectal muscle and the greater omentum have been described [10]. The greater omentum has been used most commonly, but neither histological and immunological patterns nor graft acceptance have been found to differ significantly between the greater omentum and the retroperitoneum [11]. Complications of the spleen autotransplant in the greater omentum have been described, such as cases of torsion of the implants, anaemia and subphrenic abscesses due to necrosis of the implanted tissue, and the retroperitoneum presented higher technical facility when compared with the greater omentum [10,11].

The S. aureus, a Gram-positive bacterium that can inhabit the skin and mucous membranes without causing pathologies, can also induce possibly fatal diseases, mainly through toxin liberation. This bacterium was chosen as infection model due to its importance to immunocompromised patients, being one of the most important agents causing community- and hospital-acquired infections, including pneumonia [12]. The critical role of neutrophils in the defence against staphylococcal infection is supported by recurrent infections in individuals with chronic granulomatous disease and by studies with neutrophil-depleted mice [13]. In vitro studies have shown that killing of S. aureus by neutrophils is not optimal unless antibodies and other opsonins are present. Clinical studies in splenectomized patients have shown that there is an immediate and prolonged fall in plasma tuftzin levels, which leads to a defect in neutrophil phagocytosis and a defective complement activation via the alternative pathway [14,15].

Interferon (IFN)-γ and interleukin (IL)-10 are among the cytokines capable of modulating the immune response, providing activation of effector mechanisms or anergy during the immune response against microbial antigens [16]. IFN-γ enhances the microbicidal function of macrophages, and stimulates the expression of high-affinity receptors for immunoglobulin (Ig)G and complement proteins. IgG and complement molecules are involved in the opsonization and phagocytosis of particulate microbes [17]. IL-10 has been identified as a crucial modulator of inflammatory responses. IL-10 inhibits bactericidal activity in vitro by blocking endogenous production of tumour necrosis factor (TNF)-α[18]. TNF-α has been shown to act in combating bacterial infections. It is a key cytokine in the development of inflammatory responses, enhancing the expression of adhesion molecules aside from inducing the production of chemokines in endothelial cells, and recruiting phagocytes to the infection site. TNF-α, when released at systemic levels, as in sepsis provoked by Gram-negative bacteria, is considered detrimental to the host [19,20].

The purpose of this study was to evaluate whether the autogenous splenic graft in the retroperitoneum can restore immunological functions of splenectomized mice during S. aureus infection and to seek the possible mechanisms related to the restoration of these functions. In this paper, splenic graft is shown to modulate the number of S. aureus and this effect could be associated with the cytokine profile described locally and systemically, and with the serum levels of IgM and IgG1 in infected mice possessing or lacking spleen.

Material and methods

Animals and surgical protocol

Experiments were performed with female BALB/c mice from 8 to 10 weeks old. The animals were grouped in the following way: (i) control group (CT), 11 mice subjected to midline laparotomy with subsequent laparorrhaphy; (ii) splenectomized group (SP), 11 mice subjected to splenectomy; and (iii) autotransplanted group (AT), 11 mice subjected to splenectomy and autotransplantation in the retroperitoneum. After anaesthesia (0·9 NaCl, 2% xylazine, 5% ketamine, injected intraperitoneally), a midline laparotomy was performed with subsequent splenectomy and binding of the vascular pedicle and short vessels with 5·0 catgut (Shalon, Goiânia, Brazil). All operations were performed under sterile conditions. The spleen was cut into six slices about 2·5 mm thick and kept in physiological saline at room temperature. In the AT group, the retroperitoneum was opened near the left kidney, and two pieces were placed close to the large abdominal blood vessel without fixation [11]. Skin closure was performed using a 4·0 running polyglactin suture. In the CT group, midline laparotomy, spleen mobilization and isolation of splenic vessels with subsequent laparorrhaphy was performed. The project was approved by the Committee for Ethics in Animal Experimentation of the Federal University of Juiz de Fora (no. 14/2003).

Infection and colony-forming units score

Thirty days after surgery, six mice of each group were infected by intravenous bolus injection of 5 × 106 colony-forming units (CFU) of S. aureus (ATCC 25923) obtained from the National Institute of Quality Control in Health (Oswaldo Cruz foundation, Rio de Janeiro). Animals were then killed 6 days after infection. Lungs and livers fragments from individual animals were homogenized in phosphate-buffered saline (PBS), serially diluted 10-fold and plated on mannitol. The mannitol salt agar (Oxoid, Basingstoke, Hampshire, UK) was prepared according to the manufacturer's instructions. This medium was dispensed into six-well plates (Corning Inc., Corning, NY, USA), and incubated at 37°C. CFU numbers were counted visually after 2 days' culture.

Myeloperoxidase assay

The relative extent of neutrophil accumulation in the lungs was measured indirectly by assaying myeloperoxidase (MPO) activity, as described previously [21]. Briefly, a portion of the left lung was removed and snap-frozen in liquid nitrogen. Upon thawing, the tissue (0·1 g of tissue per 1·9 ml buffer) was homogenized in pH 4·7 buffer (0·1 M NaCl, 0·2 M NaPO4, 0·015 M Na ethylenediamine tetraacetic acid), centrifuged at 3000 g for 10 min and the pellet subjected to hypotonic lyses. After a further centrifugation, the pellet was resuspended in 0·05 M NaPO4 buffer (pH 5·4) containing 0·5% hexadecyltrimethylammonium bromide. Results were expressed as change in optical density (OD) per milligram wet tissue.

N-acetylglucosaminidase assay

Infiltration of mononuclear cells in the lungs was quantified indirectly by measuring the levels of lysosomal enzyme N-acetylglucosaminidase (NAG) present at high levels in activated macrophages [22]. Pellets obtained after the centrifugation of lung homogenates were suspended in 2·0 ml cooled saline containing 0·1% v/v Triton X-100, vortex-homogenized and centrifuged at 4°C for 10 min at 1500 g. Samples of the resulting supernatant (100 µl) were incubated for 10 min with 100 µl of 2·24 mM p-nitrophenyl-N-acetyl-β-d-glucosaminide (Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO, USA), prepared in 0·1 M citrate/phosphate buffer (pH 4·5). The reaction was terminated by the addition of 100 µl 0·2 M glycine buffer pH 10·6. Hydrolysis of the substrate was determined by measuring the colour absorption at 405 nm. NAG activity was expressed as change in OD per milligram wet tissue.

Histological investigation and morphometric analysis

Lung specimens were fixed in 10% neutrally buffered formalin and embedded with paraffin for haematoxylin and eosin (H&E) staining. Histological cuts about 3 µm thick were removed from all the blocks and dyed with H&E staining. The inflammatory infiltration area in the lungs (morphometric analysis) was measured on 10 randomly chosen microscopic fields at ×100 magnification with the help of NIH Image Analysis software (version 1·61) (Bethesda, MD, USA) as the mean of area of inflammatory infiltrations divided by area of field analysed (Aii/At).

The IFN-γ, TNF-α and IL-10 detection by enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay

Lung and liver samples were homogenized in Hank's balanced salt solution containing protease inhibitor cocktail (100 µl/10 ml; Sigma-Aldrich) in a ratio of 0·1 g of tissue in 1 ml of the solution, and centrifuged at 2000 g at 4°C to collect the supernatant which was stored at −70°C in 100 µl aliquots. Blood was collected (approximately 300 µl/mouse) by retro-orbital plexus sampling into microtubes (Axygen, Union City, CA, USA) containing 10% final volume of 3% sodium citrate (w/v) at different times after infection (24 h, 48 h and 6 days) using sodium citrate-pretreated Pasteur pipettes. Plasma samples were separated by centrifugation at 300 g for 30 min and frozen at immediately −70°C. Spleens and spleen fragments were macerated and passed through steel mesh to obtain single-cell suspensions. The cells were washed twice with sterile PBS then cultured in RPMI-1640 medium supplemented with penicillin G-sodium (100 U/ml), streptomycin sulphate (100 µg/ml), amphotericin B (250 ng/ml) and 10% fetal bovine serum and then placed at 2 × 105 cells/well in 96-well tissue culture plates. Murine IFN-γ, TNF-α and IL-10 levels were determined in plasma, in the supernatant of splenocytes and in macerated lung and liver by enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) as described by the manufacturer (R&D Systems, Minneapolis, MN, USA).

Specific antibody detection

Mice were bled 6 days after infection, and individual sera were tested for antibody responses by ELISA. Plates (96-well) (Maxisorp; Nunc, Rochester, NY, USA) were incubated overnight with whole cell lysate S. aureus antigen at 10 µg/ml in carbonate–bicarbonate buffer, pH 9·6, at 4°C. Then, blocking solution [PBS containing Tween 20 (0·05%) plus 10% fetal bovine serum] was added for 2 h at 37°C. Sera from infected mice were diluted 1 : 100 in PBS-Tween 20, added to plates and incubated for 2 h at 37°C. To determine total serum IgM and IgG1, plates were treated with peroxidase-conjugated goat anti-mouse IgM molecule (1:10 000; Sigma) or peroxidase-conjugated goat anti-mouse IgG1. The reaction mixture was developed by the addition of 200 µmol of o-phenylenediamine (Sigma) and 0·04% H2O2. The reaction was stopped by the addition of 5% H2SO4 and plates were then read at 492 nm using an ELISA reader (SPECTRAMAX 190; Molecular Devices, Sunnyvale, CA, USA).

Statistical analysis

Normality of data was confirmed by a cumulative normal probability plot and Kolmogorov–Smirnov test. All results are expressed as mean ± standard error of the mean (s.e.m.). Statistical analyses were performed with Student's t-test for parametric values or Mann–Whitney U-test for non-parametric values using the GraphPad Prism 5·00 for Windows (GraphPad Software, San Diego, CA, USA).

Results

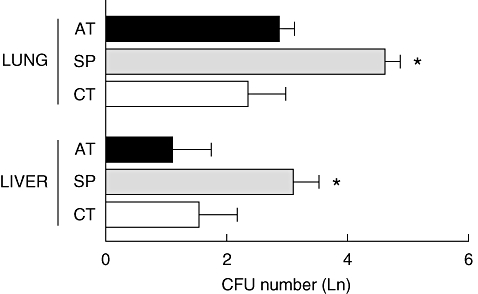

The S. aureus CFU in liver and lungs

The number of S. aureus CFU in liver and lungs of infected BALB/c mice was evaluated 6 days after infection. Figure 1 shows that a higher number of S. aureus CFU in liver and lungs was observed in the SP group in comparison with either the CT group or the group splenectomized and subsequently receiving autotransplant (AT). Our data indicate that the number of S. aureus CFU in liver and lungs is similar in the CT or AT infected groups, suggesting that splenic autotransplantation can restore the immune response against S. aureus infection after splenectomy.

Fig. 1.

Evidence that splenectomized BALB/c mice are more susceptible to Staphylococcus aureus infection and that splenic autotransplantation increases resistance to S. aureus. Groups of BALB/c mice were infected intravenously with 5 × 106S. aureus 30 days after surgery. At day 6 post-infection, the number of colony-forming units per lung and liver was determined. Data represent means of six mice from a representative experiment. CT = control group (white bar), SP = splenectomized group (grey bar), AT = autotransplanted group (black bar). *P < 0·05 versus CT and AT groups.

Detection of MPO and NAG activity in lung homogenates and morphometric analysis of inflammatory infiltration in the lungs

The MPO and the NAG activities were assayed in left lung homogenates of SP, AT and CT mice infected with S. aureus. The relative quantities of MPO present in the lungs, an indirect indicator of the number of infiltrating neutrophils, was only slightly increased in the SP infected mice (0·92 ± 0·09 absorbance/100 mg tissue) in relation to the AT (0·75 ± 0·09) and CT (0·74 ± 0·1) infected groups (Fig. 2a). The relative levels of NAG, an indirect indicator of the number of infiltrating macrophages, was slightly augmented in SP infected mice (1·07 ± 0·06) in comparison with the AT group (0·98 ± 0·04) and significantly higher in comparison with the CT (0·91 ± 0·02) group (Fig. 2b). Although not differing markedly in the MPO and NAG assays, the SP infected mice showed expansion of inflammatory infiltrations in the lungs (0·22 ± 0·01 Aii/At), which was significantly greater than that observed in the CT group (0·12 ± 0·01), but did not differ from the inflammatory infiltration area observed in the AT group (0·20 ± 0·02) at day 6 post-infection, as demonstrated by histopathology (Fig. 2c–e).

Fig. 2.

Myeloperoxidase (MPO) and N-acetylglucosaminidase (NAG) activity in lung homogenates and morphometric analysis of inflammatory infiltration in the lungs after Staphylococcus aureus infection. Neutrophil (a) and macrophage (b) accumulation in lungs was evaluated by indirect methods based on MPO and NAG activities respectively. Results represent the average of the optical density values of six infected (grey bar) and five non-infected (white bar) mice from a representative experiment. Photomicrograph showing inflammatory infiltration in lungs of S. aureus infected control (c), splenectomized (d) and autotransplanted (e) mice. The inflammatory infiltration area was measured as described previously. *P < 0·05 versus non-infected; #P < 0·05 versus control group. Bar = 100 µm.

Cytokine profile

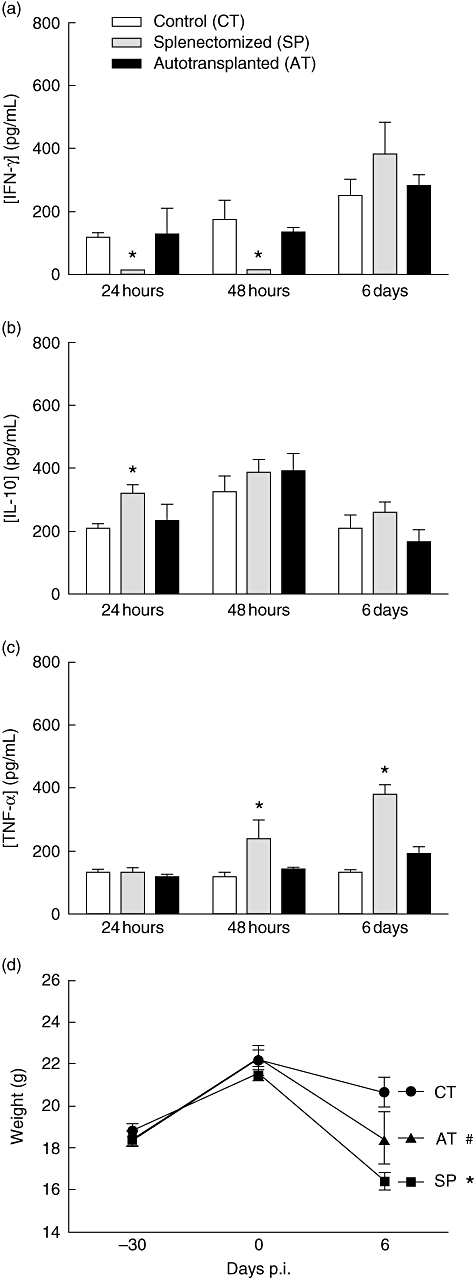

The IFN-γ, TNF-α and IL-10 secretion induced by S. aureus infection was quantified in plasma from the SP, AT and CT infected groups. Cytokine production was measured by ELISA. Higher levels of IFN-γ were detected in the plasma of the AT and the CT groups, both at 24 h and 48 h after infection, in comparison with the SP group. At 6 days of infection levels of IFN-γ increased markedly in the SP group, but did not differ significantly from those observed in CT and AT groups (Fig. 3a). IL-10 levels in plasma, in contrast, were significantly higher only in SP mice 24 h after infection in comparison with CT mice (Fig. 3b). Plasma levels of TNF-α were higher in SP mice after 48 h and after 6 days of infection in comparison with both AT and CT groups (Fig. 3c). Loss of weight was most dramatic in SP infected mice, although also notable in the AT infected group (Fig. 3d). These data suggest a systemic effect of increased TNF-α production in weight loss, as shown in previous work in other diseases [23].

Fig. 3.

Effect of splenectomy on plasma levels of interferon (IFN)-γ, interleukin (IL)-10 and tumour necrosis factor (TNF)-α and on weight loss after Staphylococcus aureus infection. Groups of BALB/c mice were infected intravenously with 5 × 106S. aureus 30 days after surgery. IFN-γ (a), IL-10 (b) and TNF-α (c) levels in plasma were evaluated at different times after infection by enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay. The body weights of infected mice were recorded before surgery (day –30), before infection (day 0) and at day 6 post-infection. Data represent means of six infected mice. *P < 0·05 versus CT and AT groups; #P < 0·05 versus SP.

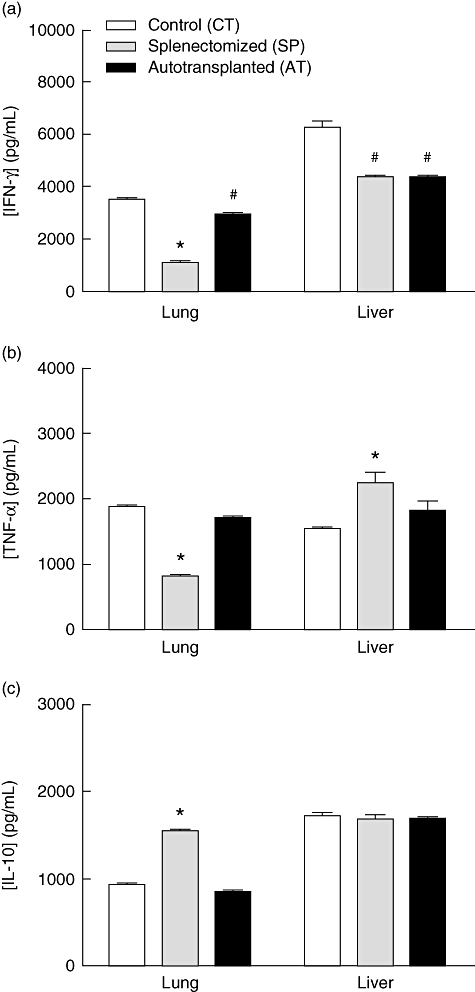

The IFN-γ, TNF-α and IL-10 were measured in liver and lung homogenates 6 days after S. aureus infection. Higher levels of IFN-γ were detected in lung and liver homogenates from the CT infected mice (3480 ± 124 and 6209 ± 268 respectively). IFN-γ production was also higher in the lung of AT mice (2894 ± 75), in comparison with the SP group (1093 ± 39, P < 0·05). Similar levels of IFN-γ were detected in liver homogenates of AT (4299 ± 134) and SP (4305 ± 136) groups (Fig. 4a). Figure 4b shows that TNF-α production was lower in the lung and higher in the liver of SP mice (808 ± 20 and 2225 ± 176 respectively) in relation to the CT (1861 ± 56 and 1518 ± 61) and AT (1689 ± 50 and 1804 ± 176) groups. IL-10 levels in lung homogenates were higher in SP mice (1540 ± 40) in comparison with either the CT (920 ± 20) or AT groups (840 ± 20) (P < 0·05). There was no significant difference for IL-10 production in the liver of the three groups studied (Fig. 4c).

Fig. 4.

Effect of splenectomy on interferon (IFN)-γ, interleukin (IL)-10 and tumour necrosis factor (TNF)-α levels in lung and liver homogenates after Staphylococcus aureus infection. Mice were infected intravenously with 5 × 106S. aureus 30 days after surgery. IFN-γ (a), TNF-α (b) and IL-10 (c) levels in lung and liver homogenates were evaluated at day 6 post-infection by enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay. Data represent means of six mice from a representative experiment. *P < 0·05 versus CT and AT groups; #P < 0·05 versus CT.

Levels of IFN-γ in supernatants of spleen cell cultures were similar between the CT (439 ± 37) and AT (442 ± 18) mice, suggesting that the IFN-γ response in implanted splenic tissue is as efficient as in the intact spleen.

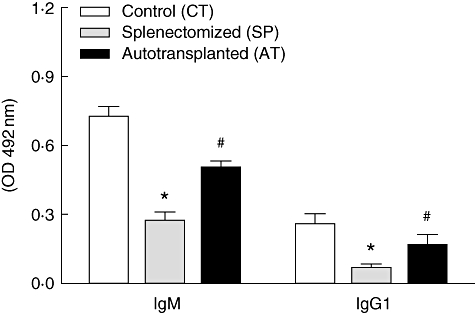

Serum levels of S. aureus-specific IgM and IgG1 antibodies

The levels of anti-S. aureus antibodies in the serum of infected mice differed significantly among the three groups studied. The control group showed the highest level of S. aureus-specific IgG1 (0·25 ± 0·02) and IgM (0·72 ± 0·01). The AT group showed an intermediary level of anti-S. aureus IgG1 (0·11 ± 0·02) and IgM (0·50 ± 0·03), while the SP group showed the lowest levels of IgG1 (0·06 ± 0·01) and IgM (0·26 ± 0·01) (Fig. 5). These levels in the AT group, although not as high as found in the CT group, demonstrate the function of the humoral immune system in recipients of autotransplant.

Fig. 5.

Effect of splenectomy on serum levels of anti-Staphylococcus aureus immunoglobulin (Ig)M and IgG1 antibodies. Mice were infected intravenously with 5 × 106S. aureus 30 days after surgery. Anti-S. aureus IgM and IgG1 antibodies were evaluated in serum at day 6 post-infection by enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay. Data represent means of six mice from a representative experiment. *P < 0·05 versus CT and AT groups; #P < 0·05 versus CT.

Discussion

The current study presents as main contribution the following findings: (i) infection by S. aureus in splenectomized (SP) mice resulted in higher CFU numbers in the liver and lungs when compared with mice splenectomized and receiving spleen autotransplant (AT) and when compared with CT animals; (ii) analysis of the MPO and NAG assays showed that all the groups studied presented similar influx of neutrophils and macrophages in lungs after S. aureus infection; however, the morphometric analysis indicated a greater inflammatory area in SP and AT mice compared with CT mice; (iii) SP animals showed a lower production of IFN-γ in plasma and lungs associated with a higher production of TNF-α in plasma and IL-10 in lungs; and (iv) levels of specific S. aureus IgM and IgG1 production were significantly lower in the SP group when compared with AT and CT mice.

Results of CFU measurements in splenectomized mice after bacterial infections have been controversial. Eskitürk and collaborators [24] have contested the importance of the spleen for protection against pulmonary sepsis provoked by intranasal infection with Pseudomonas aeruginosa. Kuranaga et al. demonstrated that splenectomy could reduce the growth of Listeria monocytogenes after intravenous infection [25]. However, in our understanding, there is strong evidence demonstrating the participation of the spleen in protecting against Gram-positive and Gram-negative bacterial infections [7,8,26,27]. This is the first study showing that autogenous implantation of the spleen can enhance the host capacity to control S. aureus infection.

The MPO and NAG assays demonstrated that the intravenous S. aureus infection caused a strong influx of neutrophils and macrophages into the lungs of all groups of mice studied. The SP group had a predominant influx of macrophages. Morphometric analysis indicated that the area of inflammation was greater for the SP and AT groups. This greater inflammatory area in AT mice seems to be due in part to a high influx of B cells (data not shown). The extension of the inflammatory infiltrate in the lungs of the infected animals seems to be proportional to the number of bacteria present in the tissue. This can explain the largest infiltrate in the SP group. The production of MPO and NAG, in spite of showing a small increase in the SP group, did not differ remarkably from the CT and AT groups. Our findings suggest the possibility that there are differences in the degree of activation of the cells present in the infiltrate, as those enzymes are increased in activated cells.

To look for indicators of cell activation associated possibly with resistance to S. aureus infection after splenectomy, we compared the production of cytokines in SP, AT and CT groups. Lower IFN-γ and TNF-α levels observed in the lungs of SP mice may be associated with a reduced macrophage activation at the site of infection which facilitates bacterial growth. IFN-γ production was similar in spleen cells after infection with S. aureus in AT and CT mice, which suggests that autotransplantation does not affect the IFN-γ response. The presence of lipoteicoic acid on the surface of S. aureus enables recognition of these pathogens through Toll-like receptor 2 [28]. Signalling by these receptors stimulates the production of IL-12 which, in turn, stimulates secretion of IFN-γ. The low production of IFN-γ by SP mice and their greater susceptibility to infection suggest a fundamental role of the spleen in the resistance to infection by S. aureus, confirming findings which indicate their importance in the activation of the immune response to blood-borne pathogens [29,30].

Animals of the SP group infected with S. aureus had less production of TNF-α in the lungs, which contrasted with the elevated levels of this cytokine in the liver and in the plasma. These data suggest a greater production of this cytokine at systemic level, which is associated with the loss of weight in these mice. Our data agree with the results observed in the literature, which demonstrate that TNF-α can play a protective role in infections caused by S. aureus; however, it is damaging to the host when released into the bloodstream [31,32].

Elevated levels of IL-10 are associated with higher S. aureus CFU numbers detected in the lungs of SP mice, and are in accordance with findings reported by Lau et al.[33]. These authors demonstrated that asplenic animals have a defect in bactericidal and phagocytic activities of alveolar macrophages. In fact, pulmonary lymph nodes in splenectomized mice are replenished with more live bacteria than in sham operated mice in response to a pneumococcal aerosol challenge [34]. Some authors have observed that abdominal sepsis syndrome resulted in significant impairment in alveolar macrophage effector cell function, which is mediated, in part, by sepsis-induced expression of IL-10. However, there is a consensus on the importance of this cytokine in the control of immune response, in the resolution of infection, avoiding the accumulation of lesions in the tissue [35].

The spleen is vital for first-line defence, being especially equipped for rapid humoral immune responses against blood-borne antigens. Once coated with complement, bacteria and viruses become circulating immune complexes [36]. The low levels of IgM and IgG1 found in the splenectomized mice, both in our study and in other reports found in the literature [4,11,26,27,36], indicate the possibility of low opsonization or removal of immunocomplexes in the spleen and the liver, compromising phagocytosis and microbial clearance by phagocytes [37].

Sipka et al. showed that splenectomy increases the number of neutrophils in the periphery, but the presence of a transplanted spleen can partially counteract this effect. However, despite the lower number of neutrophils, the phagocytic activity of these cells seems to be higher in autotransplanted and control animals than in splenectomized mice [38]. As demonstrated previously, asplenic patients have a higher level of circulating immune complexes than normal subjects [39].

The incapacity of asplenic individuals to mount an appropriate immune response after vaccination, together with the need for the use of antibiotics and the incidence of infections in these individuals, is an indication of the importance of the autotransplant approach in the case of trauma or damage to the spleen [40,41]. Our results indicate that the spleen autotransplant technique is an alternative strategy when total splenectomy is inevitable and partial splenectomy is not viable, in order to maintain splenic function and a better prognosis in the combat of the infections caused by S. aureus and other pathogens.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by FAPEMIG (CDS 255/03), CNPq (471696/2004-8) and PQI-CAPES no. 070, Brazil.

References

- 1.Mc Clusky DA, Skankalakis LJ, Colborn GL, Skandalakis JE. Tribute to a triad: history of splenic anatomy, physiology, and surgery. Part 1. World J Surg. 1999;23:311–25. doi: 10.1007/pl00013191. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.King H, Shumacker HB., Jr Susceptibility to infection after splenectomy performed in infancy. Ann Surg. 1952;136:239–42. doi: 10.1097/00000658-195208000-00006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Miko I, Brath E, Furka I, Kovacs J, Kelvin D, Zhong R. Spleen autotransplantation in mice: a novel experimental model for immunology study. Microsurgery. 2001;21:140–2. doi: 10.1002/micr.1026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Timens W. The human spleen and the immune system: not just another lymphoid organ. Res Immunol. 1991;142:316–20. doi: 10.1016/0923-2494(91)90081-s. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Peitzman AB, Ford HR, Harbrecht BG, Potoka DA, Townsend RN. Injury to the spleen. Curr Probl Surg. 2001;38:932–1008. doi: 10.1067/msg.2001.119121. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Resende V, Petroianu A. Functions of the splenic remnant after subtotal splenectomy for treatment of severe splenic injuries. Am J Surg. 2003;185:311–5. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9610(02)01407-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Pisters PW, Pachter HL. Autologous splenic transplantation for splenic trauma. Ann Surg. 1994;219:225–35. doi: 10.1097/00000658-199403000-00002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Bohnsack JF, Brown EJ. The role of the spleen in resistance to infection. Annu Rev Med. 1986;37:49–59. doi: 10.1146/annurev.me.37.020186.000405. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Buchbinder JH, Lipkoff CJ. Splenosis. Surgery. 1939;6:927–34. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Liaunigg A, Kastberger C, Leitner W, et al. Regeneration of autotransplanted splenic tissue at different implantation sites. Cell Tissue Res. 1992;269:1–11. doi: 10.1007/BF00384720. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Nunes SI, Rezende AB, Teixeira FM, et al. Antibody response of autogenous splenic tissue implanted in the abdominal cavity of mice. World J Surg. 2005;29:1623–9. doi: 10.1007/s00268-005-0060-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Rooijakkers SHM, Van Kessel KPM, Van Strijp JAG. Staphylococcal innate immune evasion. Trends Microbiol. 2005;13:596–601. doi: 10.1016/j.tim.2005.10.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Foster TJ. Immune evasion by staphylococci. Nat Rev Microbiol. 2005;3:948–58. doi: 10.1038/nrmicro1289. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Xu S, Arbeit RD, Lee JC. Phagocytic killing of encapsulated and microencapsulated Staphylococcus aureus by human polymorphonuclear leukocytes. Infect Immun. 1992;60:1358–62. doi: 10.1128/iai.60.4.1358-1362.1992. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.De Ciutiis A, Polley MJ, Metakis LJ, Peterson CM. Immunologic defect of the alternate pathway-of-complement activation postsplenectomy: a possible relation between splenectomy and infection. J Natl Med Assoc. 1978;70:667–70. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Faria AMC, Weiner HL. Oral tolerance. Immunol Rev. 2005;206:232–59. doi: 10.1111/j.0105-2896.2005.00280.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Park-Min KH, Serbina NV, Yang W, et al. FcgammaRIII-dependent inhibition of interferon-gamma responses mediates suppressive effects of intravenous immune globulin. Immunity. 2007;26:67–78. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2006.11.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Steinhauser ML, Hogaboam CM, Kunkel SL, Lukacs NW, Strieter RM, Standiford TJ. IL-10 is a major mediator of sepsis-induced impairment in lung antibacterial host defense. J Immunol. 1999;162:392–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Baud V, Karin M. Signal transduction by tumor necrosis factor and its relatives. Trends Cell Biol. 2001;11:372–7. doi: 10.1016/s0962-8924(01)02064-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Alexander HR, Sheppard BC, Jensen JC, et al. Treatment with recombinant human tumor necrosis factor-alpha protects rats against the lethality, hypotension, and hypothermia of Gram-negative sepsis. J Clin Invest. 1991;88:34–9. doi: 10.1172/JCI115298. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Matos IM, Souza DG, Seabra DG, Freire-Maia L, Teixeira MM. Effects of tachykinin NK1 or PAF receptor blockade on the lung injury induced by scorpion venom in rats. Eur J Pharmacol. 1999;376:293–300. doi: 10.1016/s0014-2999(99)00382-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Bailey PJ. Sponge implants as models. Methods Enzymol. 1988;162:327–34. doi: 10.1016/0076-6879(88)62087-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Wan Y, Xue X, Li M, et al. Prepared and screened a modified TNF-alpha molecule as TNF-alpha autovaccine to treat LPS induced endotoxic shock and TNF-alpha induced cachexia in mouse. Cell Immunol. 2007;246:55–64. doi: 10.1016/j.cellimm.2007.05.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Eskitürk A, Söyletir G, Peker O, et al. The effects of experimental splenic autotransplantation and imipenem-cilastatin treatment in postsplenectomy Pseudomonas aeruginosa sepsis. Res Exp Med. 1995;195:163–9. doi: 10.1007/BF02576785. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kuranaga N, Kinoshita M, Kawabata T, Shinomiya N, Seki S. A defective Th1 response of the spleen in the initial phase may explain why splenectomy helps prevent a Listeria infection. Clin Exp Immunol. 2005;140:11–21. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2249.2005.02735.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Altamura M, Caradonna L, Amati L, Pellegrino NM, Urgesi G, Miniello S. Splenectomy and sepsis: the role of the spleen in the immune-mediated bacterial clearance. Immunopharmacol Immunotoxicol. 2001;23:153–61. doi: 10.1081/iph-100103856. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Leemans R, Harms G, Rijkers GT, Timens W. Spleen autotransplantation provides restoration of functional splenic lymphoid compartments and improves the humoral immune response to pneumococcal polysaccharide vaccine. Clin Exp Immunol. 1999;117:596–604. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2249.1999.00943.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Schröder NW, Morath S, Alexander C, et al. Lipoteichoic acid (LTA) of Streptococcus pneumoniae and Staphylococcus aureus activates immune cells via Toll-like receptor (TLR)-2, lipopolysaccharide-binding protein (LBP), and CD14, whereas TLR-4 and MD-2 are not involved. J Biol Chem. 2003;278:15587–94. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M212829200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Jouanguy E, Döffinger R, Dupuis S, Pallier A, Altare F, Casanova JL. IL-12 and IFN-gamma in host defense against mycobacteria and salmonella in mice and men. Curr Opin Immunol. 1999;11:346–51. doi: 10.1016/s0952-7915(99)80055-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Mebius RE, Kraal G. Structure and function of the spleen. Nat Rev Immunol. 2005;5:606–16. doi: 10.1038/nri1669. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Hultgren O, Eugster HP, Sedgwick JD, Körner H, Tarkowski A. TNF/lymphotoxin-alpha double-mutant mice resist septic arthritis but display increased mortality in response to Staphylococcus aureus. J Immunol. 1998;161:5937–42. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Oviedo-Boyso J, Barriga-Rivera JG, Valdez-Alarcón JJ, et al. Internalization of Staphylococcus aureus by bovine endothelial cells is associated with the activity state of NF-kappaB and modulated by the pro-inflammatory cytokines TNF-alpha and IL-1beta. Scand J Immunol. 2008;67:169–76. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-3083.2007.02056.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Lau HT, Hardy MA, Altman RP. Decreased pulmonary alveolar macrophage bactericidal activity in splenectomized rats. J Surg Res. 1983;34:568–71. doi: 10.1016/0022-4804(83)90111-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Hebert JC, O'Reilly M, Yuenger K, Shatney L, Yoder DW, Barry B. Augmentation of alveolar macrophage phagocytic activity by granulocyte colony stimulating factor and interleukin-1: influence of splenectomy. J Trauma. 1994;37:909–12. doi: 10.1097/00005373-199412000-00006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Reddy RC, Chen GH, Newstead MW, et al. Alveolar macrophage deactivation in murine septic peritonitis: role of interleukin 10. Infect Immun. 2001;69:1394–401. doi: 10.1128/IAI.69.3.1394-1401.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Zandvoort A, Timens W. The dual function of the splenic marginal zone: essential for initiation of anti-TI-2 responses but also vital in the general first-line defense against blood-borne antigens. Clin Exp Immunol. 2002;130:4–11. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2249.2002.01953.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Johansson AG, Løvdal T, Magnusson KE, Berg T, Skogh T. Liver cell uptake and degradation of soluble immunoglobulin G immune complexes in vivo and in vitro in rats. Hepatology. 1996;24:169–75. doi: 10.1002/hep.510240128. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Sipka S, Jr, Brath E, Toth FF, et al. Distribution of peripheral blood cells in mice after splenectomy or autotransplantation. Microsurgery. 2006;26:43–9. doi: 10.1002/micr.20209. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Timens W, Leemans R. Splenic autotransplantation and the immune system. Ann Surg. 1992;215:256–60. doi: 10.1097/00000658-199203000-00010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Sumaraju V, Smith LG, Smith SM. Infectious complications in asplenic hosts. Infect Dis Clin North Am. 2001;15:551–65. doi: 10.1016/s0891-5520(05)70159-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Davies JM, Barnes R, Milligan D. Update of guidelines for the prevention and treatment of infection in patients with an absent or dysfunctional spleen. Clin Med. 2002;2:440–3. doi: 10.7861/clinmedicine.2-5-440. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]