Abstract

The purpose of this report is to explore the growth inhibitory effect of extracts and compounds from black cohosh and related Cimicifuga species on human breast cancer cells and to determine the nature of the active components. Black cohosh fractions enriched for triterpene glycosides and purified components from black cohosh and related Asian species were tested for growth inhibition of the ER− Her2 overexpressing human breast cancer cell line MDA-MB-453. Growth inhibitory activity was assayed using the Coulter Counter, MTT and colony formation assays.

Results suggested that the growth inhibitory activity of black cohosh extracts appears to be related to their triterpene glycoside composition. The most potent Cimicifuga component tested was 25-acetyl-7,8-didehydrocimigenol 3-O-β-D-xylopyranoside, which has an acetyl group at position C-25. It had an IC50 of 3.2 µg/ml (5 µM) compared to7.2 µg/ml (12.1 µM) for the parent compound 7,8-didehydrocimigenol 3-O-β-D-xylopyranoside. Thus, the acetyl group at position C-25 enhances growth inhibitory activity.

The purified triterpene glycoside actein (β-D-xylopyranoside), with an IC50 equal to 5.7 µg/ml (8.4 µM), exhibited activity comparable to cimigenol 3-O-β-D-xyloside. MCF7 (ER+Her2 low) cells transfected for Her2 are more sensitive than the parental MCF7 cells to the growth inhibitory effects of actein from black cohosh, indicating that Her2 plays a role in the action of actein. The effect of actein on Her2 overexpressing MDA-MB-453 and MCF7 (ER+Her2 low) human breast cancer cells was examined by fluorescent microscopy. Treatment with actein altered the distribution of actin filaments and induced apoptosis in these cells.

These findings, coupled with our previous evidence that treatment with the triterpene glycoside actein induced a stress response and apoptosis in human breast cancer cells, suggest that compounds from Cimicifuga species may be useful in the prevention and treatment of human breast cancer.

Keywords: actein; caffeic acid; Cimicifuga, polyphenol; triterpene glycoside

1. Introduction

The North American perennial black cohosh (Actaea racemosa L; Ranunculaceae) and related Cimicifuga species have been used for centuries, across many cultures, for a variety of health benefits. Native Americans used black cohosh as an anti-inflammatory agent (Upton, 2002). Related Asian Cimicifuga species have been used in China and Japan as antipyretic and analgesic agents (Sakurai et al., 2005), as well as to treat infectious diseases (Hsu et al., 1986). In recent years, black cohosh has been used in the United States and Europe to relieve symptoms associated with female medical conditions, particularly menopause (McKenna et al., 2001).

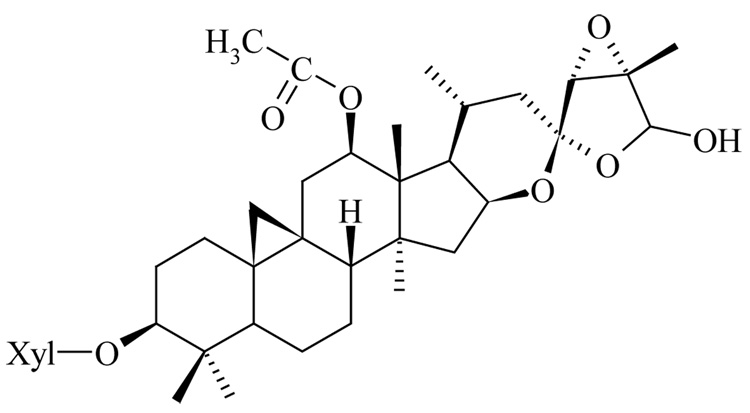

The roots and rhizomes of the plant contain 2 major classes of compounds, triterpene glycosides and phenylpropanoids. We and others had shown that extracts enriched in triterpene glycosides and specific triterpene glycosides isolated from black cohosh possess anticancer activity (Nesselhut et al., 1993; Dixon-Shanies and Shaikh, 1999; Watanabe et al., 2002; Bodinet and Freudenstein, 2004; Einbond et al., 2004; Hostanska et al., 2004a,b), but the precise mechanism and nature of the active components are not yet known. The purpose of this study is to determine: (1) the nature of the active anticancer components in black cohosh and related Cimicifuga species, and (2) the effect of the triterpene glycoside actein (Fig. 1) on the morphology of human breast cancer cells.

Figure 1.

Structure of Actein (Cimigenol-3-O-β-D-xyloside)

2. Materials and methods

Chemicals and reagents

All solvents and reagents were reagent grade; water was distilled and deionized. Black cohosh fractions and purified components were dissolved in dimethylsulfoxide (DMSO) (Sigma; St. Louis, MO) prior to addition to cell cultures. Triterpene glycosides A1, d6, d8, d10 and dE were dissolved in DMSO at 50 µg/ml (for d6: 25 µg/ml; A1 was diluted in ethanol before adding to aqueous media to a final concentration of 0.5% ethanol).

Plant materials

Cimigenol 3-O-β-D-xyloside and triterpene glycosides from related Cimicifuga species were the kind gift of Dr. Ye Wen-Cai (Guangzhou, China) (Documentation of Materials being studied as described by Ye et al., 1999; Zhang et al., 1999; Zhang et al., 2001).

Naturex, Inc. (South Hackensack, NJ) generously provided black cohosh extracts containing 1, 15 and 27% triterpene glycosides (Table 1). Black cohosh raw material was collected in the United States in 1998 from natural habitat, dried naturally by air and identified by Dr. Scott Mori from the New York Botanical Garden. Each lot of the raw material was compared with the authentic samples using HPLC. A voucher sample (9-2677) was deposited in Naturex's herbarium.

Table 1.

Composition of 1, 15 and 27% triterpene glycoside enriched extracts from black cohosh

| Compound | % Triterpene Glycosides | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| 26.69% | 14.62% | 0.87% | |

| Cimiracemoside A | 2.35 | 1.30 | 0 |

| (26R)-Actein | 0.79 | 0.69 | 0 |

| 26-Deoxycimicifugoside | 1.55 | 1.31 | 0 |

| (26S)-Actein | 2.62 | 1.52 | 0 |

| 23-epi-26-Deoxyactein | 3.01 | 1.58 | 0 |

| Acetyl shengmanol arabinoside | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Acetyl shengmanol xyloside | 3.25 | 1.73 | 0 |

| Cimigenol arabinoside | 3.67 | 1.90 | 0 |

| Cimicifugoside | 4.97 | 2.44 | 0 |

| 25-OAc-cimigenol arabinoside | 2.27 | 1.11 | 0.43 |

| 25-OAc-cimigenol xyloside | 2.23 | 1.04 | 0.44 |

| Total | 26.69 | 14.62 | 0.87 |

| % isoferulic acid | 1.83 | 0.70 | 0.64 |

Extraction and isolation procedures

Black cohosh roots and rhizomes (Lot number 9-2677; South Hackensack, NJ) were extracted with 75%EtOH/water. The ethanol was removed at 45–55 degrees C under reduced pressure. The concentrated extract was partitioned between methylene chloride and water, which provided a fraction of 15% triterpene glycosides (TG) from methylene chloride and 1% TG from water. The methylene chloride was removed at 45–55 degrees C under reduced pressure. The concentrated fraction was further partitioned between n-butanol and water and the 27% TG fraction was obtained from the n-butanol phase.

Cell cultures

MDA-MB-453 (ER negative, Her2 overexpressing) and MCF7 (ER positive, Her2 low) cells were obtained from the ATCC (Manassas, VA). Cells were grown in Dulbecco’s Modified Eagle’s medium (DMEM) (Gibco BRL Life Technologies, Inc., Rockville, MD) containing 10% (v/v) fetal bovine serum (FBS) (Gibco BRL) at 37°C, 5% C02. MCF7 and MCF7/Her2–18 {MCF7 cells transfected with a full length Her2 cDNA coding region, 45-fold increase Her2 (Benz et al., 1992)} were the kind gift of Dr. Dennis Slamon (Los Angeles, CA). These cells were maintained in RPMI supplemented with 10% FBS plus glutamine (1%) and PSF (1%) (Gibco, Rockville MD).

Proliferation Assays

Coulter Counter Assay

To determine the growth inhibitory activity, MDA-MB-453 human breast cancer cells were exposed to increasing concentrations of black cohosh extracts containing 1%, 15%, or 27% triterpene glycosides or purified triterpene glycosides from Cimicifuga species (Table 1) for 96 h and the number of viable cells was determined by the Coulter Counter assay.

Cells were seeded at 3 × 104 cells per well in 24 well plates (0.875 cm diameter); 24 h later, the medium was replaced with fresh medium with or without the indicated test materials, in triplicate. The number of attached viable cells was counted 96 hours later using a model ZF Coulter Counter (Coulter Electronics Inc., Hialeah, FL) and IC50 values were calculated, as previously described (Einbond et al., 2004). Cell viability was calculated by comparing cell counts in treated samples relative to cell counts in the DMSO or DMSO/ethanol control and converted to percentage.

MTT assay

The MTT assay was used to determine the sensitivity of MCF7 and MCF7Her2 to actein. Cells were seeded at 1 × 104 cells/well in 96-well plates and allowed to attach for 24 h. The medium was replaced with fresh medium containing DMSO or compound. The cells were treated for 96 h, after which they were incubated with MTT reagents and the absorbance read at 600 nm.

Colony formation assay

The effect of actein on the ability of MDA-MB-453 cells to form colonies was determined using the colony formation assay. Cells were seeded at 0.5–1.5 × 103 cells per well in 6-well plates; 24 h later the media was replaced with fresh media containing DMSO or compound, in triplicate. The cells were treated with actein for 24 or 96 h, then the media was replaced with fresh media not containing actein and incubated for 8 days. After incubation, media was removed and cells were washed twice with PBS. Cells were fixed in 2 ml of 100% ethanol for 10 minutes, after which ethanol was removed, and samples were allowed to dry at room temperature. Colonies were then stained for 30 minutes using 2 ml 1xGiemsa solution, rinsed with tap water, and allowed to dry at room temperature.

For cell growth assays, the data are expressed as mean +/− standard deviation. Control and treated cells were compared using the student’s t-test (p<0.05).

Indirect Immunofluorescence Microscopy of Actein-Treated Cells

The effects of actein on MCF7 and MDA-MB-453 cell structure were examined and compared by fluorescent microscopy. Cell nuclei and actin filaments were stained according to the methods of Yoon et al. (2002). MCF7 and MDA-MB-453 cells were allowed to attach to coverslips in 6-well plates (35-mm diameter), treated with DMSO (control) or actein (20 or 40 µg/ml) for 48 hours, washed with DMEM at 37°C and fixed with PBS containing 4% EM-grade formaldehyde and 0.1% Triton×100 for 10 min at room temperature. The cells were next washed with PBS. After the second wash, the PBS was replaced with 1 ml/well PBS containing 2 units/ml Texas Red-X Phalloidin to stain the actin filaments and 1 µg/ml 4,6-diamidino-2-phenylindole (DAPI) to stain the nuclei. The cells were then incubated for 20 min at room temperature and protected from light (under foil). All samples were visualized with a Nikon Optiphot microscope; images were obtained with a MicroMax cooled CCD (charge-coupled device) camera (Kodak KAF 1400 chip; Princeton Scientific Instruments, Monmouth Junction, NJ) using Metamorph software (Universal Imaging, Downingtown, PA).

3. Results

Growth inhibitory activity of extracts of black cohosh

Our previous experiments indicated that fractions and purified components from black cohosh inhibited the growth of human breast cancer cells. Of the cells tested, the Her2 overexpressing MDA-MB-453 human breast cancer cells were the most sensitive to the growth inhibitory effects of the ethyl acetate fraction and the purified triterpene glycoside actein from black cohosh. MDA-MB-453 cells overexpress the Her2, FGF and AR receptors and are mutant for p53, and they are ER negative.

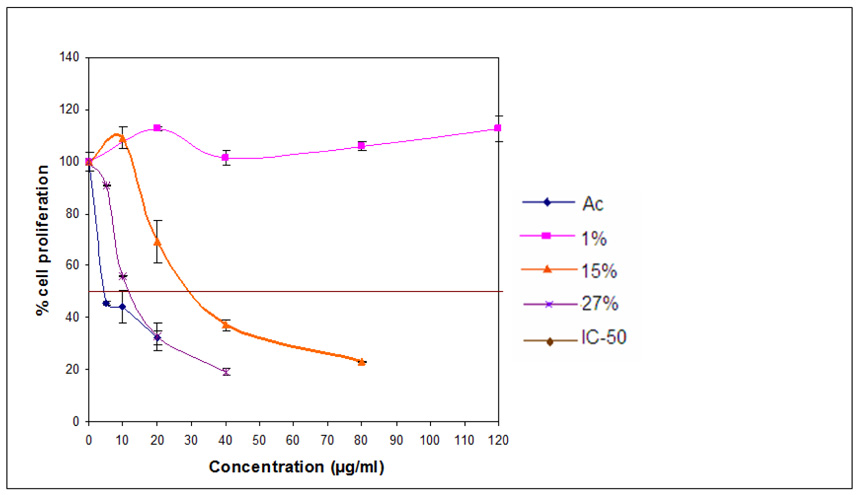

Guided by the results of these previous experiments, we tested the growth inhibitory activity of extracts of black cohosh roots and rhizomes, containing different percents of triterpene glycosides (Table 1) on MDA-MB-453 human breast cancer cells in order to explore the nature of the active components. Cells were exposed to increasing concentrations of the agents for 96 h and the number of viable cells was determined by the Coulter Counter assay, as shown in Figure 2. The extract with a low concentration of triterpene glycosides (1%) resulted in little or no inhibition of cell growth (Fig. 2). The IC50 value, the concentration that caused 50% inhibition of cell proliferation, for the extract with 15% triterpene glycosides was 29 µg/ml, and for the extract with 27% triterpene glycosides, the IC50 value was 12 µg/ml. An IC50 value of 4.5 µg/ml (6.7 µM) was obtained with the purified triterpene glycoside actein. The percent of the polyphenol isoferulic acid in the respective three fractions was: 1.8; 0.7; and 0.6%.

Figure 2.

Effect of 3 extracts enriched for triterpene glycosides or actein on cell proliferation in MDA-MB-453 (Her2 overexpressing) human breast cancer cells. MDA-MB-453 cells were treated with increasing concentrations of each of 3 extracts containing 1, 15, 27% triterpene glycosides or actein for 96 h and the number of viable cells determined using a Coulter Counter. Similar results were obtained in an additional study.

Growth inhibitory activity of compounds from Cimicifuga species

Our previous experiments (Einbond et al., 2004) indicated that of the black cohosh triterpene glycosides tested, actein was the most potent. To further characterize the nature of the active components, we tested the effects of a series of triterpene glycosides from related Cimicifuga species on cell proliferation (Table 2). The most strongly acting component was d13 (25-acetyl-7,8-didehydrocimigenol 3-O-β-D-xylopyranoside) which has an acetyl group at position C-25; it had an IC50 of 3.2 µg/ml (5 µM) compared to7.2 µg/ml (12.1 µM) for the parent compound d11 (7,8-didehydrocimigenol 3-O-β-D-xylopyranoside), which lacks the acetyl residue. Compound d6 (24-epi-7,8-didehydrocimigenol 3-O-β-D-xylopyranoside), the 24-epi derivative of compound d11, exhibited efficacy similar to that of d11 (IC50=7.2 µg/ml; 11.7 µM).

Table 2.

Effect of purified triterpene glycosides/aglycone from Cimicifuga species on cell proliferation in MDA-MB-453 (Her2 overexpressing) human breast cancer cells

| Code | Plant Species | Chemical Name | M.W. | IC50 µg/ml | IC50 µM |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| A1 | Cimicifuga acerina | Cimigenol 3-O-β-D-xylopyranoside | 620 | 6 | 9.7 |

| C2 | Cimicifuga acerina | (22R)-22-hydroxycimigenol 3-O-β-D-xylopyranoside | 636 | 29 | 45.6 |

| d6 | Cimicifuga dahurica | 24-epi-7,8-didehydrocimigenol 3-O-β-D-xylpyranoside | 618 | 7.2 | 11.7 |

| d8 | Cimicifuga dahurica | 12 β-hydroxycimigenol 3-O-α-L-arabinopyranoside | 636 | 55 | 86.5 |

| d10 | Cimicifuga dahurica | 24-O-acetylisodahurinol 3-O-α-L-arabinopyranoside | 684 | 17 | 24.9 |

| d11 | Cimicifuga dahurica | 7,8-didehydrocimigenol 3-O-β-D-xylopyranoside | 596 | 7.2 | 12.1 |

| d13 | Cimicifuga acerina | 25-acetyl-7,8-didehydrocimigenol 3-O-β-D-xylopyranoside | 638 | 3.2 | 5.0 |

| dE | Cimicifuga dahurica | 3-O-α-L-arabinopyranosyl cimigenol 15-O-β-D-glucopyranoside | 804 | 72 | 89.6 |

| Ac | Actaea racemosa | actein, β-D-xylopyranoside | 676 | 5.7 | 8.4 |

MDA-MB-453 cells were treated with increasing concentrations of each of the Cimicifuga components for 96 h and the number of viable cells determined using a Coulter Counter. Similar results were obtained in an additional study.

Actein (β-D-xylopyranoside), with an IC50 equal to 5.7 µg/ml (8.4 µM), exhibited activity comparable to cimigenol 3-O-β-D-xyloside, which had an IC50 value of 6 µg/ml (9 µM). Compound d10 (24-O-acetylisodahurinol 3-O-α-L-arabinopyranoside), a 24-acetyl derivative, possessed the next highest activity, with an IC50 value of 15 µg/ml (24.9 µM). Compounds C2 ((22R)-22-hydroxy cimigenol 3-O-β-D-xylopyranoside) and d8 (12 β-hydroxycimigenol 3-O-α-L-arabinopyranoside), hydroxyl derivatives of compound A1, exhibited less growth inhibitory activity, with IC50 values of 29 µg/ml (46 µM) and 55 µg/ml (87 µM), respectively. Compound dE (3-O-α-L-arabinopyranosyl cimigenol 15-O-β-D-glucopyranoside), which possesses several sugar residues, was also less active, with an IC50 value of about 72 µg/ml (90 µM).

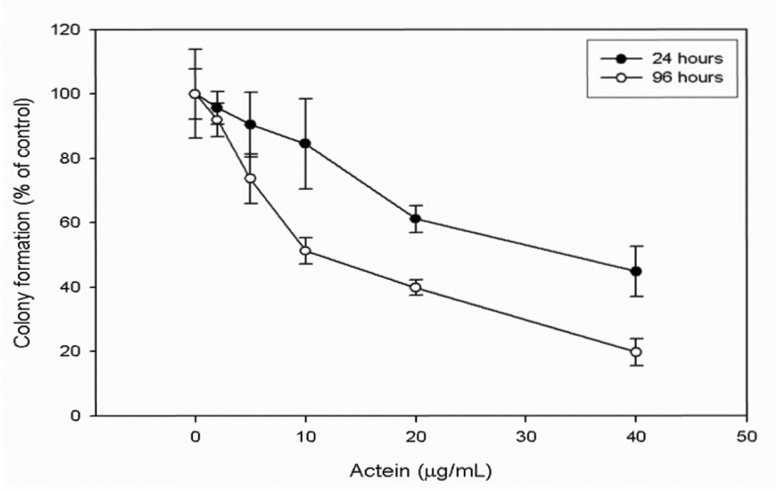

Colony formation assay

To ascertain the anticancer potential of actein, we tested the effect of actein on the ability of MDA-MB-453 cells to form colonies. The colonies were smaller on average in the actein treated cells: the IC50 values after 24 and 96 h were 33 µg/ml (48.7 µM) and 10 µg/ml (14.8 µM), respectively (Fig. 3).

Figure 3.

Effect of actein on the ability of MDA-MB-453 cells to form colonies. MDA-MB-453 cells were treated with increasing concentrations of actein for 24 or 96 h and the number of colonies determined using the colony formation assay.

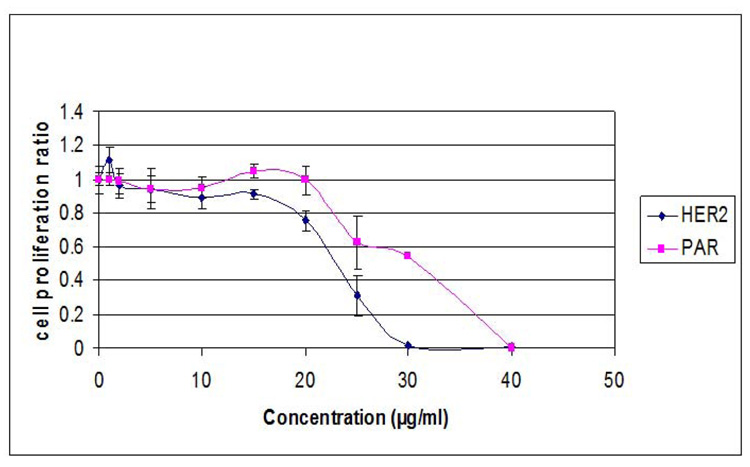

Effect of actein on MCF7 and MCF7(Her2) human breast cancer cells

To determine whether sensitivity correlates with Her2 expression, we compared the effects of actein on the genetically matched pair of human breast cancer cells, MCF7 (ER+, Her2 low) and MCF7/Her2, transfected with a full length Her2 cDNA coding region (Benz et al., 1992). We found that the Her-2 transfected cells (IC50 value: 22 µg/ml; 32.5 µM ) were more sensitive than the parental cells (IC50 value: 31 µg/ml; 45.8 µM) (Fig. 4).

Figure 4.

Effect of actein on cell proliferation in MCF7(Her2) and MCF7 human breast cancer cells. Cells were treated with increasing concentrations of actein for 96 h and the number of viable cells determined using the MTT assay. Similar results were obtained in an additional study.

Fluorescent microscopy of the effects of actein on human breast cancer cells

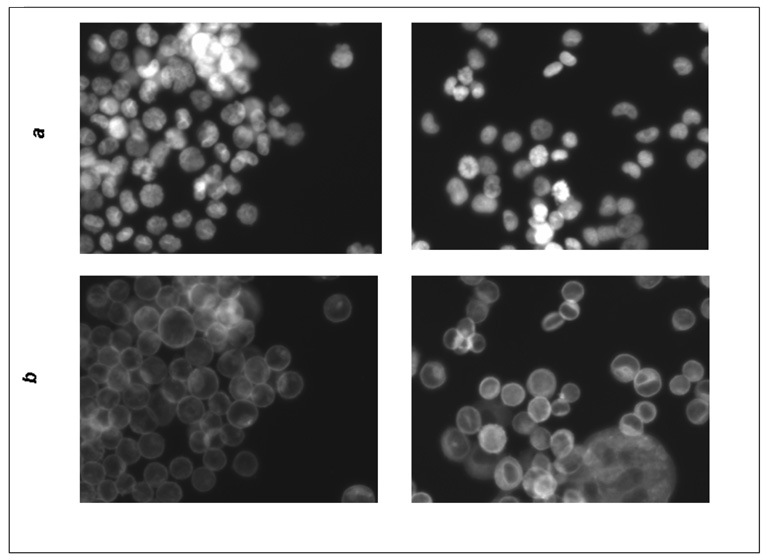

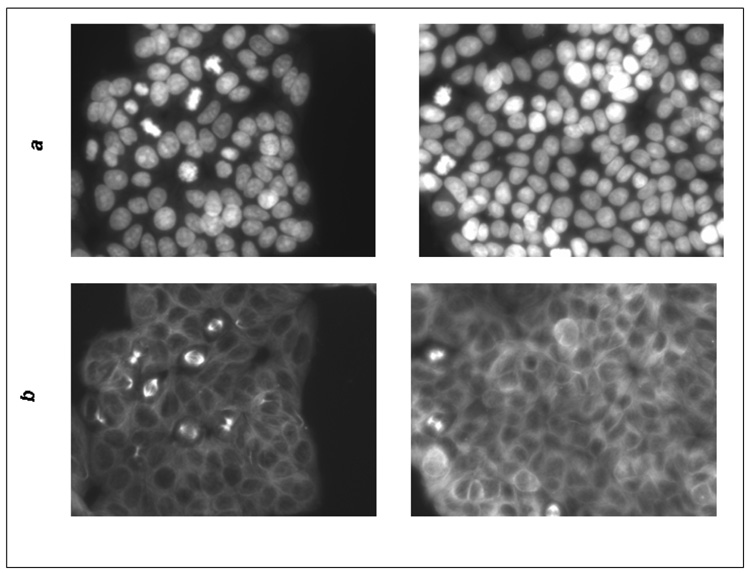

We observed two effects of actein on MCF7 and MDA-MB-453 cell structure by fluorescent microscopy (Fig. 5): (1) there were fewer cells in mitosis in the MCF7 cells treated with actein at 20 µg/ml for 48 h, and (2) the distribution of actin filaments was altered after treatment with actein in both the MCF7 and MDA-MB-453 cells. In the untreated cells, actin was primarily beneath the cell membrane, whereas in the actein treated cells, actin was dispersed in the cytoplasm and also present around the nucleus. Furthermore, the nuclei had a donut-shape, which is characteristic of apoptotic cells.

Figure 5.

Fluorescence microscopy of MDA-MB-453 and MCF7 cells treated with actein. MDA-MDA-453 or MCF7 cells were treated with actein at 20 or 40 µg/ml for 48 h, fixed with methanol, stained for DNA or actin, and observed by indirect fluorescence microscopy, as described in Materials and Methods: (A) MCF7 cells: a) DAPI stain; b) actin stain; (left) DMSO, (right) 20 µg/ml actein; (B) MDA-MB-453 cells: a) DAPI stain; b) actin stain (left) DMSO, (right) 40 µg/ml actein; magnification, x200.

4. Discussion

This study examined the growth inhibitory activity of extracts and purified components from Cimicifuga species on human breast cancer cells. Our results support the hypothesis that the growth inhibitory effect of black cohosh on human breast cancer cells is primarily due to the triterpene glycoside fraction. In additional unpublished studies we tested the activity of individual components of the black cohosh caffeic acid (polyphenol) fraction. The IC50 values of the polyphenols cimicifugic acid G (Nuntanakorn et al., 2006), A and B, fukinolic acid, ferulic and isoferulic acid were greater than 100 µM on MDA-MB-453 cells. Although these polyphenols were more active on MCF7 cells than MDA-MB-453 cells, they displayed very weak activity on both cell lines. Our present and previous results indicate that the percent inhibition of cell proliferation is related to the triterpene glycoside content of back cohosh and not the isoferulic content; however, we can not exclude a role for this polyphenolic fraction or other components.

Our results contradict the finding of Hostanska et al. (Hostanska et al. 2004b) that the caffeic acid ester (CAE) fraction is more active than the triterpene glycoside fraction on MCF7, ER+, human breast cancer cells. This difference in results could be due to the use of different subclones, experimental procedures or incubation media, or to the fact that the polyphenols and triterpene glycosides differ in molecular weight. Thus, Hostanska et al. (Hostanska et al. 2004b) performed their assays in estrogen-free medium and were only able to find increased activity for the CAE fraction in the crystal violet and early apoptosis assays.

The acetyl group at position C-25 appears to be important for the growth inhibitory activity of the triterpene glycoside compound d13 (25-acetyl-7,8-didehydrocimigenol 3-O-β-D-xylopyranoside). This is consistent with the findings that the acetyl derivative of boswellic acid {3-O-acetyl-11-keto-β-boswellic acid (AKBA)} from Boswellia serratia (Shao et al., 1998) and the 16-acetate derivative of gitoxigenin from Digitalis purpurea (Lopez-Lazaro et al., 2003) are also more active than the parent compounds.

Since the colonies in the colony formation assay were smaller on average in the actein-treated cells, actein appears to decrease the rate of cell proliferation, i.e., actein appears to have cytostatic as well as cytotoxic activity. Her2 may play a role in the action of actein, since MCF7 cells transfected for Her2 appear to be more sensitive to the growth inhibitory effects of actein than the parental cells. This is consistent with our finding that MDA-MB-453 cells, which are ER− and Her2+, were the most sensitive of the cells that we tested. It is possible that the greater sensitivity of the transfected cells may reflect in part the difference in growth rates of the transfected and parental cells.

We found that treatment of MCF7 or MDA-MB-453 cells with actein altered their cell structures, since the actin filaments aggregated around the cell nuclei and the nuclei appeared donut-shaped (Fig. 5). These effects are consistent with actein inducing apoptosis; the aggregation of actin around the nucleus occurs in response to cell stress (Haskin et al., 1993). These results corroborate the results of our previous studies indicating that the growth inhibitory effect of actein or an extract of black cohosh is associated with activation of specific stress response pathways and apoptosis (Einbond et al., 2007; Einbond et al., in press). Taken together, these results indicate that the triterpene glycoside actein and related compounds may be useful in the prevention and treatment of human breast cancer.

Acknowledgements

We thank Sung-Min Park, Hyun Park, Dr. Shannon Brightman, Alejandro Ramirez and Laura Chen for excellent technical assistance and Dr. Dennis Slamon for the kind gift of MCF7 and MCF7 (Her2) cells.

This research was supported by NIH-NCCAM Grant 3P50 AT00090-02S2 and NIH-NCCAM K01 AT001692-01A2. The contents of this paper are solely our responsibility and do not necessarily reflect the official views of NIH-NCCAM. This research was also supported by the Susan G. Komen Breast Cancer Foundation Grant BCTR0402502 to L. S. E.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- Benz CC, Scott GK, Sarup JC, Johnson RM, Tripathy D, Coronado E, Shepard HM, Osborne CK. Estrogen-dependent, tamoxifen-resistant tumorigenic growth of MCF-7 cells transfected with HER2/neu. Breast Cancer Res Treat. 1992;24:85–95. doi: 10.1007/BF01961241. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bodinet C, Freudenstein J. Influence of marketed herbal menopause preparations on MCF-7 cell proliferation. Menopause. 2004;11:281–289. doi: 10.1097/01.gme.0000094209.15096.2b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dixon-Shanies D, Shaikh N. Growth inhibition of human breast cancer cells by herbs and phytoestrogens. Oncol. Rep. 1999;6:1383–1387. doi: 10.3892/or.6.6.1383. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Einbond LS, Shimizu M, Xiao MD, Nuntanakorn P, Lim JT, Suzui M, Seter C, Pertel T, Kennelly EJ, Kronenberg F, Weinstein IB. Growth inhibitory activity of extracts and purified components of black cohosh on human breast cancer cells. Breast Cancer Res. Treat. 2004;83:221–231. doi: 10.1023/B:BREA.0000014043.56230.a3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Einbond LS, Su T, Wu H, Friedman R, Wang X, Jiang B, Hagan T, Kennelly EJ, Kronenberg F, Weinstein IB. Gene expression analysis of the mechanisms whereby black cohosh inhibits the growth of human breast cancer cells. Anticancer Research. 2007;2:697–712. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Einbond LS, Su T, Wu HA, Friedman R, Wang X, Ramirez A, Kronenberg F, Weinstein IB. The growth inhibitory effect of actein on human breast cancer cells is associated with activation of stress response pathways. Int J Cancer. 2007 Nov 1;121(9):2073–83. doi: 10.1002/ijc.22897. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haskin CL, Athanasiou KA, Klebe R, Cameron IL. A heat-shock-like response with cytoskeletal disruption occurs following hydrostatic pressure in MG-63 osteosarcoma cells. Biochem. Cell Biol. 1993;71:361–371. doi: 10.1139/o93-054. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hostanska K, Nisslein T, Freudenstein J, Reichling J, Saller R. Cimicifuga racemosa extract inhibits proliferation of estrogen receptor-positive and negative human breast carcinoma cell lines by induction of apoptosis. Breast Cancer Res. Treat. 2004a;84:151–160. doi: 10.1023/B:BREA.0000018413.98636.80. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hostanska K, Nisslein T, Freudenstein J, Reichling J, Saller R. Evaluation of cell death caused by triterpene glycosides and phenolic substances from Cimicifuga racemosa extract in human MCF-7 breast cancer cells. Biol. Pharm. Bull. 2004b;27:1970–1975. doi: 10.1248/bpb.27.1970. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hsu H-Y, Chen Y-P, Hsu C-S, Shen S-J, Chen C-C, Chang H-C. Oriental materia medica: a concise guide. New Canaan: Keats Publishing, Inc.; 1986. [Google Scholar]

- Lopez-Lazaro M, Palma De La Pena N, Pastor N, Martin-Cordero C, Navarro E, Cortes F, Ayuso MJ, Toro MV. Anti-tumour activity of Digitalis purpurea L. subsp. heywoodii. Planta Med. 2003;69:701–704. doi: 10.1055/s-2003-42789. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McKenna DJ, Jones K, Humphrey S, Hughes K. Black cohosh: efficacy, safety, and use in clinical and preclinical applications. Altern. Ther. Health Med. 2001;7:93–100. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nesselhut T, Schellhase C, Dietrich R, Kuhn W. Studies on mamma carcinoma cells regarding the proliferative potential of herbal medications with estrogen-like effects. Arch. Gynecol. Obstet. 1993;254:817–818. [Google Scholar]

- Nuntanakorn P, Jiang B, Einbond LS, Yang H, Kronenberg F, Weinstein IB, Kennelly EJ. Polyphenolic constituents of Actaea racemosa. J. Nat. Prod. 2006;69:314–318. doi: 10.1021/np0501031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sakurai N, Kozuka M, Tokuda H, Mukainaka T, Enjo F, Nishino H, Nagai M, Sakurai Y, Lee KH. Cancer preventive agents. Part 1: chemopreventive potential of cimigenol, cimigenol-3,15-dione, and related compounds. Bioorg. Med. Chem. 2005;13:1403–1408. doi: 10.1016/j.bmc.2004.10.062. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shao Y, Ho CT, Chin CK, Badmaev V, Ma W, Huang MT. Inhibitory activity of boswellic acids from Boswellia serrata against human leukemia HL-60 cells in culture. Planta Med. 1998;64:328–331. doi: 10.1055/s-2006-957444. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Upton R, editor. American Herbal Pharmacopoeia and Therapeutic Compendium. Santa Cruz: American Herbal Pharmacopoeia; 2002. Black Cohosh Rhizome. [Google Scholar]

- Watanabe K, Mimaki Y, Sakagami H, Sashida Y. Cycloartane glycosides from the rhizomes of Cimicifuga racemosa and their cytotoxic activities. Chem. Pharm. Bull. (Tokyo) 2002;50:121–125. doi: 10.1248/cpb.50.121. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ye W, Zhang J, Che CT, Ye T, Zhao S. New Cycloartane Glycosides from Cimicifuga dahurica. Planta Med. 1999;65:770–772. doi: 10.1055/s-2006-960865. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yoon JT, Palazzo AF, Xiao D, Delohery TM, Warburton PE, Bruce JN, Thompson WJ, Sperl G, Whitehead C, Fetter J, Pamukcu R, Gundersen GG, Weinstein IB. CP248, a derivative of exisulind, causes growth inhibition, mitotic arrest, and abnormalities in microtubule polymerization in glioma cells. Mol. Cancer Ther. 2002;1:393–404. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang QW, Ye WC, Che CT, Zhao SX. A new cycloartane saponin from Cimicifuga acerina. J. Asian Nat. Prod. Res. 1999;2:45–49. doi: 10.1080/10286029908039890. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang QW, Ye WC, Hsiao WW, Zhao SX, Che CT. Cycloartane glycosides from Cimicifuga dahurica. Chem. Pharm. Bull (Tokyo) 2001;49:1468–1470. doi: 10.1248/cpb.49.1468. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]