Abstract

We previously demonstrated potentiated effects of maternal Pb exposure producing blood Pb(PbB) levels averaging 39 μg/dl combined with prenatal restraint stress (PS) on stress challenge responsivity of female offspring as adults. The present study sought to determine if: 1) such interactions occurred at lower PbBs, 2) exhibited gender specificity, and 3) corticosterone and neurochemical changes contributed to behavioral outcomes. Rat dams were exposed to 0, 50 or 150 ppm Pb acetate drinking water solutions from 2 mos prior to breeding through lactation (pup exposure ended at weaning; mean PbBs of dams at weaning were <1, 11 and 31 μg/dl, respectively); a subset in each Pb group underwent prenatal restraint stress (PS) on gestational days 16-17. The effects of variable intermittent stress challenge (restraint, cold, novelty) on Fixed Interval (FI) schedule controlled behavior and corticosterone were examined in offspring when they were adults. Corticosterone changes were also measured in non-behaviorally tested (NFI) littermates. PS alone was associated with FI rate suppression in females and FI rate enhancement in males; Pb exposure blunted these effects in both genders, particularly following restraint stress. PS alone produced modest corticosterone elevation following restraint stress in adult females, but robust enhancements in males following all challenges. Pb exposure blunted these corticosterone changes in females, but further enhanced levels in males. Pb-associated changes showed linear concentration dependence in females, but non-linearity in males, with stronger or selective changes at 50 ppm. Statistically, FI performance was associated with corticosterone changes in females, but with frontal cortical dopaminergic and serotonergic changes in males. Corticosterone changes differed markedly in FI vs. NFI groups in both genders, demonstrating a critical role for behavioral history and raising caution about extrapolating biochemical markers across such conditions. These findings demonstrate that maternal Pb interacts with prenatal stress to further modify both behavioral and corticosterone responses to stress challenge, thereby suggesting that studies of Pb in isolation from other disease risk factors will not reveal the extent of its adverse effects. These findings also underscore the critical need to extend screening programs for elevated Pb exposure, now restricted to young children, to pregnant, at risk, women.

Keywords: lead, prenatal stress, corticosterone, HPA axis, gender, stress responsivity, Fixed Interval

INTRODUCTION

Although dramatic reductions in blood lead (PbB) levels occurred in the U.S. and other countries following the phase out of lead (Pb) from gasoline, elevated exposures remain a significant public health problem, especially for low socioeconomic status (SES) populations. The highest PbB values are found in African-American medically-underserved households with income <$25,000 renting homes built before 1950. Current estimates indicate at least 2.4 million children with PbBs >5 μg/dl (Iqbal et al., 2008). This continuing problem now largely reflects residual contamination resulting from years of use of Pb-based paints. It is further compounded by accumulating reports of adverse health outcomes at increasingly lower PbBs. Cognitive deficits in children, for example, have now been shown to occur at PbBs well below the Center for Disease Control’s (CDC) designated 10 μg/dl level of concern, and have even been suggested to occur with no threshold (Canfield et al., 2003; Lanphear et al., 2005).

As with all chemicals, Pb exposure occurs in the context of numerous other factors that influence vulnerability to diseases and disorders, including genetic background, and other host, environmental, and behavioral risk factors. One such factor, stress, is common to virtually all human populations, and may occur during the prenatal period or at any time throughout the life span. Recently, prenatal stress has received particular attention because of the associated glucocorticoid programming which has been demonstrated both in animal models and humans to leads to permanent adverse cardiovascular, metabolic, neuroendocrine and behavioral effects (Seckl, 2008).

Stress may be particularly pertinent to low SES communities. Low SES has been associated with higher incidences of various diseases and disorders even when access to medical care is considered (Dohrenwend, 1973; Starfield, 1982; Pappas et al., 1993; Anderson and Armstead, 1995; Stipek and Ryan, 1997). One hypothesis ascribes this phenomenon to chronically elevated levels of stress associated with low SES environments (Munck et al., 1984; Lupien et al., 2001). Thus, elevated Pb burden and stress are significant co-occurring risk factors for low SES communities. Importantly, both Pb exposure and stress (via the hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal (HPA) axis, the system that mediates the body’s response to stress) act in conjunction with brain mesocorticolimbic dopamine and glutamate systems (Diorio et al., 1993; Lowy et al., 1993; Piazza et al., 1996; Pokora et al., 1996; Cory-Slechta et al., 1998; Barrot et al., 2000; Moghaddam, 2002) which could provide a biological basis for interactive effects.

Based on this premise, we carried out studies in rats that initially focused on the adverse consequences of combined maternal Pb exposure (Pb exposure of offspring ended at weaning) combined with prenatal stress (PS) on offspring function, using measures that included corticosterone, regional brain dopamine and serotonergic neurotransmitter changes, and behavioral function, the latter evaluated using a Fixed Interval (FI) schedule of reinforcement, a behavioral task with demonstrated sensitivity to Pb (Cory-Slechta, 1984; Cory-Slechta and Weiss, 1985; Cory-Slechta, 1992).

PS itself can result in a wide variety of apparently permanent consequences for offspring, among which are alterations in the responsivity of offspring to stress challenges and permanent changes in function of the HPA axis (Fride et al., 1986; McCormick et al., 1995; Rimondini et al., 2003; Igosheva et al., 2007). For that reason, stress responsivity of offspring was evaluated by imposing a series of various stress challenges (restraint, novelty, and cold) immediately prior to an FI behavioral test session in these offspring as adults. In females, cold stress resulted in reductions in FI response rates but only in the combined Pb + PS groups, consistent with synergistic effects. Moreover, combined Pb+PS female offspring exhibited the smallest increase in corticosterone following cold stress (Cory-Slechta et al., 2004a; Virgolini et al., 2006; Cory-Slechta et al., 2008).

In this initial study, however, only a single Pb exposure concentration was studied, one that resulted in maternal PbBs averaging 39 μg/dl, a level quite high in the context of accumulating evidence of adverse effects on the central nervous system in children at PbBs <10 μg/dl (Canfield et al., 2003; Lanphear et al., 2005). In addition, offspring were housed individually in the initial study. Isolation housing itself is known to induce stress (Cabib et al., 2002; Francolin-Silva and Almeida, 2004), and could, therefore, have influenced outcomes even differentially by gender. The current study therefore sought to further characterize stress challenge responsivity of combined Pb + PS offspring as adults, by determining whether: 1) such interactions occur at lower, environmentally relevant PbB levels, 2) manifest differentially by gender, and 3) result in corticosterone or neurochemical changes that may contribute to the behavioral outcomes.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Animals and Pb Exposure

Three week old female Long Evans rats (Charles River, Germantown, NY) were randomly assigned to receive 0 ppm (tap water), 50 or 150 ppm Pb acetate dissolved in distilled deionized water. Previous studies from our laboratory show 50 ppm to produce PbBs averaging 10-15 μg/dl (Cory-Slechta et al., 1985) and the 150 ppm exposure with mean PbBs ranging from 32.6 ± 4.4 to 42.7 ± 4.0 μg/dl.

Pb exposure of dams was initiated two months prior to breeding, and was continued throughout lactation to ensure elevated bone Pb levels to produce a Pb body burden in dams (Cory-Slechta et al., 1987), consistent with human exposure. When females reached 3 mos of age, they were paired with 3 mos old male Long-Evans rats for breeding as previously described (Virgolini et al., 2008).

Breeding and Maternal Stress

Pregnant females in each Pb-treated group were weighed and further randomly subdivided to a non-stress (NS) or maternal stress (PS) sub-groups (see below) and individually housed for the remainder of pregnancy and lactation. This resulted in six groups of Pb-stress conditions with the following sample sizes: 0NS (n=20); 0PS (n=23); 50NS (n=21); 50PS (n=31); 150NS (n=19); and 150PS (n=33).

On gestational days 16 and 17, dams assigned to PS groups were weighed and subjected to three 45 min restraint sessions (0900, 1200 and 1500h) (Virgolini et al., 2008). NS dams were weighed and subsequently left undisturbed in their home cages. The choice of days 16 and 17 was timed to correspond to the development of key brain regions associated with the endpoints under study (Yi et al., 1994; Diaz et al., 1997).

At delivery (postnatal day 1: PND1), litters were culled to 8 pups, maintaining equal numbers of males and females wherever possible. Pups were weaned at PND21 when Pb exposure ended, separated by gender, and housed in littermate pairs for the duration of the experiment. Only one pup was used from each litter for each outcome measure to preclude any litter-specific effects.

At weaning, subsets of PS pups within each Pb group were assigned to an offspring stress (PS+OS) sub-group. The current study presents results of the stress challenges to offspring in adulthood and thus shows findings only from the PS+OS groups. At weaning, pups were provided with unrestricted access to tap water (0 ppm) and lab chow until male pups reached approximately 300 g and females 220 g. At this point, caloric intake was restricted to maintain the above-stated body weights. At 55-60 days of age, behavioral training was initiated. Group sizes of n=10-11 per gender (one male and one female per litter) in each of the Pb PS+OS groups were used to evaluate the effects of a series of three variable stressors, presented intermittently, on Fixed Interval (FI) schedule-controlled behavior (FI rats) and on corticosterone levels measured following the FI session. The FI schedule served as the behavioral baseline from which to evaluate stress challenge based on its documented sensitivity to Pb exposure across species and developmental periods of exposure (Cory-Slechta, 1996) which would therefore facilitate interpretation of Pb-stress interactions.

To evaluate the impact of behavioral training itself on outcome measures, littermates of the offspring used in the behavioral evaluation, deemed non-FI (NFI) rats, were subjected to minimal handling conditions after weaning, remaining in home cages, but were exposed to the same offspring stress challenges (see below) and corticosterone determinations as FI rats (see below).

Fixed Interval Performance

Behavioral training was initiated when offspring reached two-three months of age. An FI 1 min schedule of food reinforcement was implemented after lever press training in operant chambers as previously described (Virgolini et al., 2008). This schedule provided a 45 mg food pellet (Bioserv, Frenchtown, NJ) for the first occurrence of a designated response after a 1 min interval had elapsed. Reinforcement delivery also initiated the next 1 min FI. Responses during the 1 min interval itself had no programmed consequences. Sessions were initiated by the first response or after 5-min if no response had occurred, and ended following the completion of the 1-min interval in progress 20 min after the session began, or after a total of 21 min, whichever occurred first. Standard behavioral measures of FI performance were computed, including overall response rate (total number of responses divided by total session time), post-reinforcement pause time (PRP; time to the first response in the interval) and run rate (number of responses per minutes during the interval, calculated without the PRP).

Offspring Stress Procedures

Multiple variable stressors rather than a single homotypical stress challenge were used to more closely mimic the human experience across the life span and to preclude any habituation effects. Moreover, different stressors have been demonstrated to produce different neuroendocrine profiles (Pacak, 2001), and thus they might be predicted to reveal differential aspects of Pb-stress interactions. Stress challenges were carried out during the acquisition phase of FI training so that the ability to elicit group differences was maximized. Stress challenges were imposed in the order of restraint, followed by cold, followed by novelty. The use of the most intense stressor, restraint, before other stress challenges was based on its potential to increase sensitivity of the animals to subsequent stressors (Koolhaas et al., 1997), thereby potentially maximizing the ability to detect treatment-related differences.

FI Rats

Offspring stress challenges were imposed immediately prior to an FI session to measure impact on subsequent FI performance. Restraint stress was imposed prior to session 13 in both males and females, using the same procedure described above for the dams. Prior to session 21 for females, and session 20 for males, cold stress, considered a mild physical stress, was imposed. Animals were placed in cages similar to home cages (without the bedding) at 4° C in a temperature-controlled room for 30 min prior to being placed in the operant chambers. Prior to session 30 for females and session 31 for males, animals underwent a 15 min test of locomotor activity in locomotor activity cages as a novel environment stressor. The period of stress challenge in FI animals covered the 14-18 weeks of age range. Behavioral testing on the FI schedule continued for an additional 3 months post stress challenge testing to determine whether any further changes in baseline FI performance emerged, after which animals were sacrificed and brain regions collected for neurochemical analyses as previously described (Virgolini et al., 2008).

NFI Rats

NFI offspring, that were minimally handled and remained in home cages post-weaning, were subjected to the same schedule of stressors and post-session determination of corticosterone levels as FI littermates. Given the numbers of animals involved in the study, stress challenges were carried out according to the same schedule in FI and NFI rats, but began approximately 4 weeks later in NFI offspring and covered the 18-22 weeks of age range. Corticosterone determinations were carried out at the same time points post stress challenge in NFI rats as in FI rats. They remained in transport cages between the stress challenge and corticosterone determination and were then returned to home cages.

Corticosterone Determination

Since a pre-stress challenge blood collection was likely to serve as another stressor in these groups, particularly in NFI rats, basal corticosterone levels determined in littermates of rats from each Pb group were used to calculate percent change for all stress challenges. For basal determinations, tail blood from a subset of PS littermates from which the PS+OS groups were derived was collected immediately after an FI behavioral session after approximately 8-10 FI sessions had been conducted (n=8 for each group).

For corticosterone determinations post-stress challenge, tail blood was collected immediately after the FI behavioral test session following each stress challenge. Blood was not collected during the 20 min FI session as it would have significantly disrupted behavioral performance. A final non-stress corticosterone determination was collected on the PS+OS groups at the termination of behavioral testing on the FI schedule, approximately 3 months later. Corticosterone analyses were carried out using (ImmuChem™ Double Antibody Corticosterone 125I kit (MP Biomedicals, Orangeburg, NY as previously described (Virgolini et al., 2008).

Blood Pb Analysis

Blood Pb levels were measured in a subset of dams (n=7-9 for each group) at the time of weaning (PND21) by anodic stripping voltammetry according to methods described previously (Cory-Slechta et al., 1987). Blood Pb levels were determined in a subset of pups from each Pb+/-PS treatment group at the time of weaning.

Neurochemical Determinations of Catecholamines, 5-HT and 5-HIAA

At the completion of behavioral testing, frontal cortex, nucleus accumbens and striatum were collected for determinations of monamine and analyzed by high-performance liquid chromatography (HPLC) with electrochemical detection as previously reported (Virgolini et al., 2008).

Data and Statistical Analysis

Blood Pb Concentrations

Overall analysis of PbBs of dams and pups, from blood collected at the time of weaning, were analyzed using ANOVAs with Pb, stress and group (dam, male offspring, female offspring) as between group factors. Subsequent lower order ANOVAs, based on the outcome of the overall ANOVA, were done separately comparing male offspring to dams and female offspring to dams, as well as ANOVAs that included all groups but a single Pb exposure concentration.

Effects of Stress Challenge on FI Performance

Changes in FI performance following stress challenges were calculated for each animal as a percent of its performance in the preceding FI non-challenge test session (basal), with each animal’s data serving as its own basal control value. Statistical analysis was then carried out on the percent of control values. Because different stressors are associated with different neuroendocrine profiles (Pacak, 2001), each stressor was analyzed separately by one way ANOVA with Pb as a between group factor. Analyses were carried out separately for each gender and FI performance measure following initial RMANOVAs confirming significant main effects and interactions based on gender. In the event of main effects, post-hoc tests to assess Pb group differences were carried out.

Corticosterone Changes

Corticosterone levels determined after each stress challenge and the final non-stress determination level were calculated as a percent of the basal corticosterone levels determined in littermates after approximately 8-10 FI sessions, just prior to the initiation of stress challenges. For this purpose, group mean values for each Pb-PS group were utilized, since all PS+OS offspring came from PS dams. Thus, for each gender, values from 0 PS+OS offspring were calculated as a percent of the same gender group 0 PS basal levels, 50 PS+OS groups as a percent of 50 PS basal levels, and 150 PS+OS levels as a percent of 150 PS basal levels, etc. Basal corticosterone levels determined prior to stress challenges for these experimental groups were previously reported (Virgolini et al., 2008) and are also listed in the corresponding figure legends.

Because different stressors are known to produce different neuroendocrine profiles (Pacak, 2001), corticosterone changes following each stress challenge and the final determination were analyzed separately by one-factor ANOVAs using Pb as a between groups factor for each gender and for FI vs. NFI rats. In the event of significant effects, post-hoc tests were carried out to determine specific differences among the Pb groups. Comparisons of percent change in FI vs. NFI corticosterone values were also carried out using repeated measures ANOVAs with Pb and behavioral testing status (FI vs. NFI) as between group variables and corticosterone determination (restraint, cold, novelty, final) as a within-group variable. In the case of significant main effects or interactions, post-hoc tests were carried out as appropriate for a given stress challenge.

Correlations Between Behavioral and Corticosterone Responses to Stress Challenges

To examine potential relationships between changes in corticosterone levels and in FI performance following the stress challenges, simple linear regression analyses inclusive of all three Pb groups were carried out separately for males vs. females, for each stress challenge, and for each measure of FI performance.

Relationship of Behavioral Responses to Stress Challenges and Neurochemical Changes

To explore the potential relationships between changes in FI performance following stress challenges and changes in neurotransmitter levels induced by these treatments measured at the completion of FI testing approximately 3 mos later, backward stepwise regression analyses were used, with FI performance measures on the day of the stressor as dependent variables and neurochemical changes at the termination of behavioral testing (Virgolini et al., 2008) as the independent variables. Thus, a backward stepwise regression analysis was run, for example, with each FI performance measure (overall rate, run rate, postreinforcement pause time) from a session preceded by one of the stress challenges (restraint, cold, novelty) as a dependent variable and neurochemical changes measured at the termination of behavioral testing as the independent variables. Model outcomes and corresponding r2 values are presented in Table 1, as well as the specific region and neurotransmitters that retained a high enough F score to remain in the model. Backward, rather than forward regression was used given that significant changes were produced by Pb/stress across a wide group of neurotransmitters, virtually all of which have been reported to contribute to behavioral effects of stress. In these analyses, F values were set at 4.00 to remain in the model and at 3.996 to be removed from the model. Analyses were carried out separately for males and females for each stress challenge and for each measure of FI performance.

Table 11.

Results of Stepwise Backward Regression of Corticosterone and Neurochemical Changes in Relation to FI Performance Following Stress Challenges

| FI PERFORMANCE MEASURE | Overall Rate | Run Rate | PRP | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Females | Males | Females | Males | Females | Males | |

| RESTRAINT STRESS | ||||||

| Model Outcome | r2=0.518 | r2=0.79 | r2=0.29 | r2=0.58 | r2=0.096 | r2=0.110 |

| p=0.025 | p<0.0001 | p=0.006 | P=0.003 | p=0.149 | P=0.0848 | |

| Variables in Model | ||||||

| NA 5HT | FC DATO | FC HIAA | FC DATO | STR HIAA | FC NE | |

| FC HIAA | FC DA | NA 5HT | ||||

| FC DA | STR 5HT | FC DOPAC | ||||

| STR DOPAC | FC HVA | FC DA | ||||

| FC DOPAC | NA 5HT | NA HIAA | ||||

| FC HIAA | STR DATO | |||||

| COLD STRESS | ||||||

| Model Outcome | r2=0.08 | r2=0.68 | r2=0.106 | r2=0.75 | r2=0.78 | r2=0.06 |

| p=0.171 | p=0.055 | p=0.1123 | p=0.009 | p<0.0001 | p=0.208 | |

| Variables in Model | FC HIAA | FC DATO | STR DATO | STR DATO | ||

| FC 5HT | NA DA | |||||

| FC DA | NA NE | |||||

| STR DOPAC | NA HVA | |||||

| STR HVA | FC HIAA | |||||

| STR 5HT | STR HIAA | |||||

| FC NE | NA DOPAC | |||||

| NA 5HT | FC DA | |||||

| STR HIAA | STR 5HT | |||||

| NA DOPAC | NA DATO | |||||

| FC DATO | FC 5HT | |||||

| NA DA | NA HIAA | |||||

| NOVELTY STRESS | ||||||

| Model Outcome | r2=0.42 | r2=0.106 | r2=0.94 | r2=0.116 | r2=0.515 | r2=0.536 |

| p=0.009 | p=0.0978 | p=0.0003 | p=0.0758 | p=0.006 | p=0.003 | |

| Variables in Model | FC HVA | STR 5HT | FC NE | NA NE | NA NE | FC DA |

| FC 5HT | NA DOPAC | FC DATO | FC DOPAC | |||

| NA 5HT | NA NE | STR DATO | FC NE | |||

| STR DATO | NA DA | FC DATO | ||||

| STR HIAA | STR DOPAC | |||||

| FC HIAA | ||||||

| FC DA | ||||||

| STR DA | ||||||

| FC DATO | ||||||

| NA HVA | ||||||

| NA DA | ||||||

| FC HVA | ||||||

| STR DOPAC | ||||||

Results of backward stepwise regression analysis run for each FI performance measure (overall rate, run rate, postreinforcement pause time) from a session preceded by one of the stress challenges (restraint, cold, novelty) as a dependent variable with neurochemical changes measured at the termination of behavioral testing (Virgolini et al., 2008) as the independent variables. Model outcomes and corresponding r2 values are presented for each analysis, as well as the specific region and neurotransmitters that retained a high enough F score to remain in the model. Neurotransmitters listed in bold represent those that showed up most frequently across models in which statistically significant outcomes were observed. FC=frontal cortex, NA=nucleus accumbens, STR=striatum; DA=dopamine; DOPAC= 3,4-dihydroxyphenylacetic acid, HVA=homovanillic acid; DATO=dopamine turnover; NE=norepinephrine; 5HT=serotonin; HIAA= 5-hydroxyindoleacetic acid

A p value ≤0.05 was considered significant in all statistical analyses.

RESULTS

Blood Pb Concentrations

PbBs of dams and pups, both collected at the time of pup weaning, are shown in Figure 1. Group mean PbBs (μg/dl) of all groups increased with increasing Pb exposure concentration. Overall ANOVA revealed significant main effects of Pb and gender (both p values <0.0001) as well as a gender × Pb interaction (p<0.0001), but no main effects or interactions that included stress. Subsequent lower-order ANOVAs confirmed that these effects were due to significantly higher PbBs of male and female offspring at 50 ppm, where levels of dams were approximately 12 μg/dl and those of pups approximately 19 μg/dl. At 150 ppm, PbBs of neither males nor female pups differed from offspring, but those of female offspring were higher than those of male offspring, an effect largely due to the slightly lower PbBs of the 150PS males relative to other groups, although there was no significant interaction with stress. Our prior studies demonstrate that pup PbBs decline after weaning following maternal Pb exposure, such that they are below detection limits by 40 days of age (Widzowski et al., 1994).

Figure 1.

PbBs (μg/dl) of dams and male and female offspring in relation to Pb exposure concentration and stress condition (NS and PS). Each value represents a group mean ± S.E. Sample sizes ranged from 7-9 per treatment group in dams and from 2-8 in male offspring and 3-9 in female offspring.

Changes in FI Performance Following Stress Challenges

Females

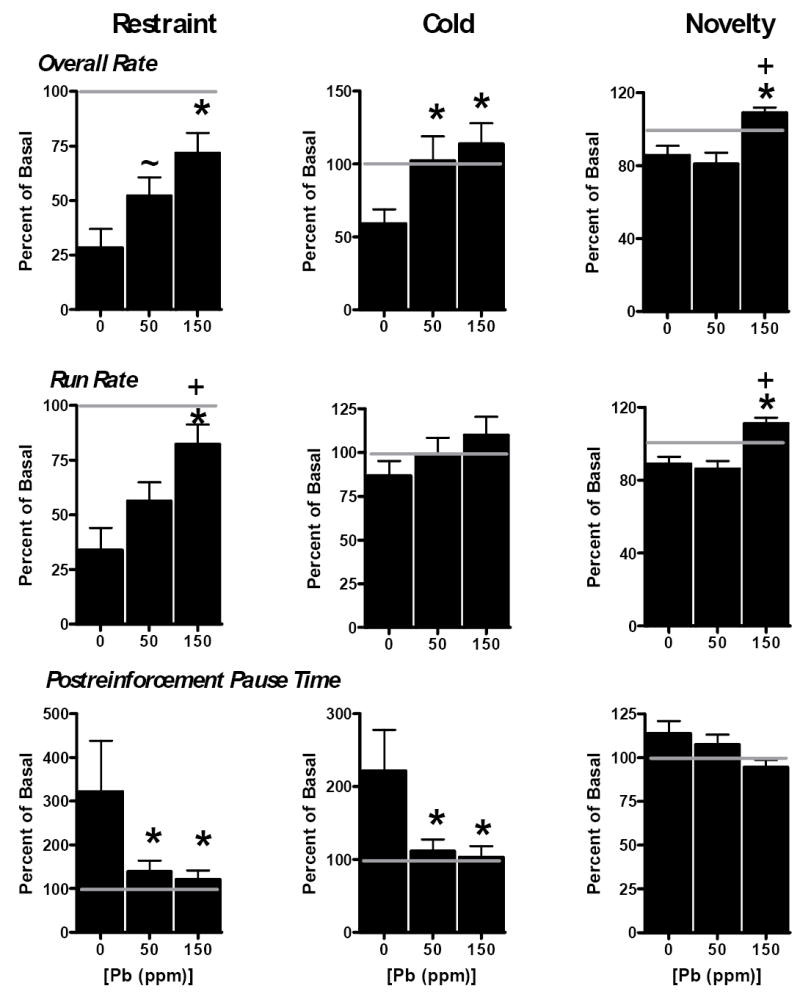

Restraint stress, the first stress challenge imposed, markedly reduced FI overall response rate (Figure 2, top left) in controls (0 ppm) by reducing run rates (middle left) and increasing PRP times (bottom left). These effects were blunted by Pb in a concentration-related fashion. While overall rates of 0 ppm females were reduced by almost 75%, corresponding reductions were only 48% and 28% for the 50 and 150 ppm groups, respectively (p=0.006). Similar differences between Pb-treated groups were observed for run rate (p=0.004). While PRP times of controls increased to greater than 300% of baseline levels, corresponding values for the 50 and 150 ppm groups were 139% and 121%, respectively (p=0.047).

Figure 2.

Changes in FI performance (overall rate, top row; run rate, middle row; PRP, bottom row) in response to restraint stress (left column), cold stress (middle column) and novelty stress (right column) in relation to Pb exposures (ppm) in female offspring. For each animal, data were calculated as a percent of the prior FI session performance value, defined as basal control. Each bar represents a group mean ± S.E. The horizontal line at 100 in each plot is used to highlight the direction and magnitude of differences in performance. Sample sizes ranged from 9-11 per treatment group. * indicate significantly different from 0 ppm; + indicates significantly different from the 50 ppm group; ~ indicates marginally different from 0 ppm (p=0.066). Basal levels of FI performance: overall rate = 10.1 ± 2.2, 17.1 ± 2.3 and 14.2 ± 1.6 for 0, 50 and 150 ppm groups, respectively; corresponding values for run rate = 13.5 ± 1.4, 18.7 ± 1.4 and 18.7 ± 1.4 and for PRP= 15.8 ± 2.9, 12.9 ± 1.7 and 14.9 ± 1.9.

Cold stress also suppressed overall FI response rates in controls (middle column), although less dramatically than did restraint stress. Here too, Pb exposure blunted the stress challenge response (p=0.034) both at 50 and 150 ppm. A similar but non-significant trend was evident in run rates. Cold stress, like restraint stress, increased PRP times in controls, but significantly smaller increases were found in both the 50 and 150 ppm females (p=0.04).

Novelty stress, the final stress challenge, likewise reduced FI overall rates and run rates (p=0.0007 and <0.0001, respectively) in control offspring, effects diminished in this case only by the 150 ppm exposure.

Males

Pb exposure also modified the stress challenge responses seen in male offspring (Figure 3). In contrast to the reduction in FI overall rates associated with stress challenges in females, control males exhibited increased FI overall rates (p=0.025) and run rates (p=0.0014) following restraint stress. As with females, Pb exposure blunted these effects, but did so in a non-linear fashion, with significantly lower overall rate and run rate at 50 ppm, but not at 150 ppm, yielding a U-shaped concentration-effect function. These reductions at 50 ppm were on the order of 52-68% relative to 0 ppm levels. No changes in PRP times were observed.

Figure 3.

Changes in FI performance (overall rate, top row; run rate, middle row; PRP, bottom row) in response to restraint stress (left column), cold stress (middle column) and novelty stress (right column) in relation to Pb exposures (ppm) in male offspring. For each animal, data were calculated as a percent of the prior FI session performance value, defined as basal control. Each bar represents a group mean ± S.E. The horizontal line at 100 in each plot is used to highlight the direction and magnitude of differences in performance. Sample sizes ranged from 10-11 per treatment group. * indicate significantly different from 0 ppm; + indicates significantly different from the 50 ppm group; ~ indicates marginally different from 0 ppm. Basal levels of FI performance: overall rate = 13.7 ± 2.3, 7.5 ± 2.6 and 12.2 ± 3.6 for 0, 50 and 150 ppm groups, respectively; corresponding values for run rate = 21.9 ± 3.0, 21.5 ± 3.3 and 24.8 ± 5.2 and for PRP= 17.4 ± 1.9, 18.3 ± 4.0 and 18.7 ± 2.1.

Cold stress challenge increased FI overall and run rates, but only in the 150 ppm offspring (p=0.0046 and 0.011, respectively) by 20-25% relative to 0 ppm. A non-significant trend towards a blunting at 150 ppm of increased PRP times observed in the 0 and 50 ppm groups was also observed.

FI overall and run rates were not significantly impacted by novelty stress in males. A significant increase in PRP times (p=0.0076) was due to a 36% increase in the 50 ppm group relative to levels in the 0 ppm and 150 ppm groups.

Corticosterone Levels Following Stress Challenges and Final Basal Determination

Corticosterone levels were determined following the completion of each FI session that was preceded by a stress challenge (restraint, cold, novelty) and again prior to the termination of the experiment (final non-stress determination).

Females

In control FI females (Figure 4, top left panel), the first stress challenge, restraint, increased corticosterone levels by approximately 28% relative to basal levels, while neither cold stress nor novelty stress elevated corticosterone. Final corticosterone levels of control females were similar to cold and novelty stress levels. The corticosterone elevation in response to restraint stress in 0 ppm females was modified by Pb exposure (p=0.0001), where reductions in corticosterone levels relative to basal values were found at both 50 and 150 ppm. No other Pb-related modifications were noted.

Figure 4.

Changes in corticosterone levels of female (top row) and male (bottom row) offspring for Pb treated groups (as indicated) in response to various stress challenges (restraint, cold, novelty) as well as a final basal determination, with all values calculated as a percent of the basal corticosterone levels determined prior to the initiation of stress challenges. For this purpose, group mean values for each Pb-PS group were utilized, since all PS+OS offspring came from PS dams. Thus, values from 0PS+OS female offspring were calculated as a percent of the group 0 PS basal levels, 50PS+OS females as a percent of the group 50 PS basal levels, and 150PS+OS offspring as a percent of the group 150PS basal levels. Data are shown for animals used in FI behavioral testing (left panel) and for littermates not used in FI behavioral testing but subjected to the same stress challenge procedures (NFI; right panel). Sample sizes ranged from 9-11 per treatment group for females and from 10-11 per treatment group for males. Each bar represents a group mean ± S.E. value. * indicate significantly different from 0 ppm; + indicates significantly different from the corresponding FI group. Basal corticosterone values (ng/ml) for FI females were: 413 ± 72, 555 ± 58 and 437 ± 71 for 0, 50 and 150 ppm groups, respectively; corresponding values for NFI females were 383 ± 45, 490 ± 62 and 523 ± 66. Basal corticosterone values (ng/ml) for FI males were: 122 ± 20, 83 ± 24 and 146 ± 31 for 0, 50 and 150 ppm groups, respectively; corresponding values for NFI males were 301 ± 22, 230 ± 19 and 290 ± 26.

The profile of corticosterone changes in NFI female offspring (top right panel) showed both similarities and differences to that of FI females (Pb × behavioral condition × corticosterone determination, p=0.016). Most strikingly, in 0 ppm NFI females, corticosterone levels were elevated by approximately 50% following restraint stress, a value comparable to that in FI females, but which thereafter exhibited a trend, albeit non-statistically significant, towards further increases with successive stress challenges to the final corticosterone determination. Indeed, values of NFI 0 ppm females exceeded those of FI 0 ppm females following both cold (58%) and novelty stress challenge (88%) and remained elevated at the final corticosterone determination (104%).

In correspondence with the Pb effects in FI female offspring, Pb exposure at both 50 and 150 ppm, prevented the corticosterone response after all three stress challenges, producing levels approximately 50% lower than in the 0 ppm group. Final non-stress corticosterone determination in both the 50 and 150 ppm NFI groups were approximately 75% lower than those of control NFI females.

Males

Corresponding results for male offspring are presented in Figure 4, bottom panels. In contrast to FI females, FI males showed robust corticosterone elevations following all three stress challenges, although the magnitude diminished across stress challenges. In the 0 ppm group, values reached 400% of basal levels following restraint stress, dropped to levels of 255% of control following cold stress and to 157% following novelty stress. Values were 62% of basal levels at the final corticosterone determination. Pb exposure modified the corticosterone response to all three stress challenges (restraint: p=0<0.0001, cold: p=0.006; novelty: p=0.019), but in a non-linear fashion, with marked increases only at 50 ppm, where corticosterone levels exceeded those of 0 ppm counterparts by 181%, 130% and 135% following restraint, cold and novelty stress challenges, respectively. In general, values of the 150 ppm group were comparable to those of controls, although there was a marginally significant (p=0.052) reduction of corticosterone increases in the 150 ppm group following restraint stress. Corticosterone levels of the 50 ppm group remained slightly higher than those of the 0 ppm (49%) and 150 ppm (66%) groups, even at the final corticosterone determination (p=0.014).

Corticosterone changes in NFI males differed dramatically from FI counterparts, with significantly lower corticosterone levels at all determination points and a virtual absence of elevations relative to basal levels. Pb-related differences, nevertheless, were observed in response to restraint stress, but, again, only at 50 ppm, where levels were approximately 45% greater than both 0 and 150 ppm values. At the final corticosterone determination, levels of Pb-treated groups were actually lower than control (p=0.0009), with reductions of 38% and 23% at 50 and 150 ppm, respectively.

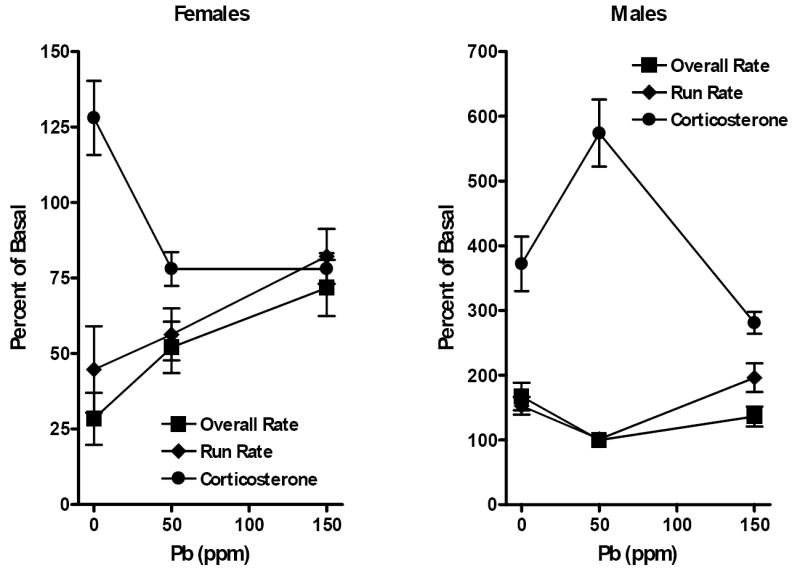

Correlations Between Behavioral and Corticosterone Responses to Stress Challenges

For both genders, the most robust FI performance alterations and corticosterone changes occurred in response to restraint stress. Two analyses were used to ascertain the potential relationship between corticosterone changes and FI performance changes following restraint. Simple plots of percent of control changes for each of these measures show (Figure 5), in females (left), an inverse correspondence between corticosterone levels and FI response rates, with elevated corticosterone levels in controls associated with lower FI response rates, lower corticosterone levels of both 50 and 150 ppm groups occurred with higher FI response rates. Correspondingly, in males, the robust increase in corticosterone levels seen in the 50 ppm offspring was associated with decreases in FI response rates.

Figure 5.

Changes in percent of control overall rate and run rate on the FI schedule and in percent of control corticosterone levels following restraint stress challenge of female (left panel) and male (right panel) offspring in relation to Pb exposure level (ppm). Each data point represents a group mean ± S.E. value.

A simple linear regression model used to examine these data more systematically (Figure 6) confirms significant inverse relationships between restraint-induced corticosterone levels and FI overall response rates (p=0.0002) and FI run rates (p=0.024) in females, findings associated with r2 values of 0.38 and 0.158, respectively. Correspondingly, Pb-treated female offspring exhibited higher response rates following restraint challenge than did controls, and lower corticosterone levels (cf. Figures 1 and 3). In addition, increased corticosterone levels were associated with increased PRP times in females (Figure 6, p=0.0038; r2=0.27), and PRP times of controls were markedly higher than Pb-treated female offspring following restraint stress, and controls also had higher corticosterone levels.

Figure 6.

Correlation plots showing changes in FI overall rate (left column), run rate (middle column), PRP times (right column) following restraint stress challenge in relation to corticosterone levels determined following restraint stress. Values for female are shown in the top row and for males in the bottom row. r2 and p values from the corresponding linear regression analysis are indicated in each plot. Each data point represents an individual animal.

In males, similar trends to those seen in females were observed for all three FI performance measures, but none of the linear regression analyses achieved statistical significance and far weaker r2 values were observed.

Relationship of Behavioral Responses to Stress Challenges and Neurochemical Changes

Behavioral testing on the FI schedule continued for approximately 3 months following stress challenge testing at which point changes in dopamine, norepinephrine and serotonin and their metabolites were determined as reported previously (Virgolini et al., 2008). Backward stepwise regression analyses were used to explore the potential roles of these neurochemical changes as determinants of the changes in FI performance following stress challenges in both genders.

As shown in Table 1, for female offspring, significant models were confirmed for overall rate and run rate following restraint stress, for PRP in response to cold stress, and for overall rate, run rate and PRP following novelty stress. Corresponding r2 values ranged from 0.29 to 0.94. In the case of male offspring, significant models emerged for overall rate and run rate following restraint stress and cold stress and for PRP following novelty stress, with r2 values ranging from 0.54 to 0.79.

Variables common across models in males and females were primarily related to frontal cortical function and included dopamine, dopamine turnover and the serotonin metabolite 5-HIAA (n=7, 7 and 6 occurrences, respectively). R2 values in male models were greater than those for female models for overall rate and run rate following restraint and cold stress. In addition to higher r2 values, both frontal cortical dopamine and dopamine turnover occurrences were more prevalent in male offspring (5 of 7 occurrences in both cases). Some evidence for involvement of striatal serotonergic changes was found predominately in males, with 4 models including striatal 5-HT and 3 including 5-HIAA; the latter was observed in only one model in female offspring. Also notable from these analyses was the correspondence of outcome in males and females in models for PRP following cold stress, where the only variable entering in both cases was striatal dopamine turnover; the model was significant only in female offspring. Furthermore, for novelty stress, PRP models were significant for both genders, and in both cases, frontal cortical dopamine turnover was a significant variable in the model.

DISCUSSION

The current study confirms that maternal Pb exposure modifies the effects of prenatal stress on adult stress responsivity in both genders, blunting behavioral outcomes on the FI schedule of reinforcement, and modifying corticosterone levels measured post-stress challenge. Importantly, effects were observed even at PbBs of 10-11 μg/dl in dams at weaning, the lowest PbBs we have examined to date. Several outcomes of the study are notable, as elaborated below.

Effects of Prenatal Stress Differ Significantly by Gender

While control females showed suppression of FI performance following stress challenges, their male counterparts exhibited marked increases in rates, particularly following restraint stress (Figures 2 and 3). Moreover, while FI control females exhibited higher absolute levels of corticosterone, but modest corticosterone changes in response to restraint stress and little change in response to other stressors, absolute corticosterone levels in males were lower than females, but increases following stress challenges were almost 400% following restraint and ranged between 150-250% following cold and novelty stress (Figure 4).

Differential effects of prenatal stress by gender have been reported in multiple studies, including our previous studies of Pb-stress interactions (Cory-Slechta et al., 2004b; Virgolini et al., 2006; Weinstock, 2007). Although hormonal changes are often raised as a potential mechanism of such differences, several other possibilities need to be considered. Although numerous studies document rate-dependent effects of drugs on FI performance, with low rates of responding increased and higher rates decreased or unchanged (Dews, 1958), rate-dependency does not appear to account for gender differences in FI performance outcomes following stress challenge in this study since basal FI response rates of 0 ppm females, although lower than those of males by approximately 50% and were decreased, rather than increased following stress challenges (Virgolini et al., 2008).

Absolute corticosterone levels, however, may be a more important determinant of outcome, and corticosterone-induced changes may not be linearly related to absolute level. Indeed, biphasic corticosterone dose-effect functions have been reported for hippocampal plasticity (Diamond et al., 1992) and memory formation (Sandi and Rose, 1997). Absolute basal corticosterone levels of all female groups exceeded those of all male groups. Additionally, females may be exposed to higher levels of corticosterone in utero following prenatal stress. Montano et al. (Montano et al., 1993) reported 58% higher baseline serum corticosterone concentrations following prenatal stress in female fetuses as compared to males at day 18 of pregnancy due to an increased passage of corticosterone across the placenta of females. What such studies suggest is that the evaluation of true gender differences will require their distinction from potential differences in corticosterone dosing conditions, i.e., comparisons under conditions of equivalent prenatal corticosterone dosing/basal corticosterone levels. At this point, it is not possible to eliminate the possibility that a higher level of prenatal stress (higher maternal corticosterone “dose”) would produce comparable changes in males in studies examining gender differences or that lower corticosterone levels in females would produce effects similar to those observed in males.

Through Different Concentration-Effect Functions, Pb Exposure Blunted the Behavioral Response to Restraint Stress in Both Genders, but Produced Dichotomous Corticosterone Changes in Males and Females

Pb exposure modified both the robust behavioral responses to stress challenge, and the associated corticosterone changes associated with prenatal stress in both genders. Maternal Pb blunted the FI response to stress challenges in both females and males, and did so independently of the direction of rate change observed. Specifically, Pb diminished the FI rate suppression observed in female offspring following all three stress challenges, and the FI rate increases found in control male offspring following restraint stress (Figures 2 and 3). In some conditions moreover, males demonstrated an exaggerated behavioral response to stress (cold, novelty), where none was otherwise seen. In addition, maternal Pb blunted the increases in corticosterone following restraint stress in females, but dramatically enhanced (at 50 ppm) corticosterone changes in males (Figure 4).

Stress responding per se is, of course, highly beneficial to survival, since it evokes behavioral and physiological responses that direct a reinstatement to homeostatic conditions. Consequently, either the inability to mount the expected behavioral and corticosterone response to stress challenge, or an exaggerated response, as observed here under conditions of combined maternal Pb and prenatal stress, would have to confer a specific disadvantage.

Notably, these effects were associated with quite different Pb exposure concentration-effect functions in males vs. females. Whereas changes in FI performance were linearly related to exposure concentration in females, a U-shaped, non-linear concentration effect curve characterized the changes in male offspring, with the most pronounced effects at 50 ppm, a concentration associated with PbBs of only 10-11 μg/dl. Non-linear dose effect curves for Pb exposure have been noted for a variety of effects including locomotor activity, cerebral cortex growth, operant behavior, maze performance, age at vaginal opening, serum urea and urate and body weight and height (Davis and Svendsgaard, 1990; Leasure et al., 2008). The basis of this non-linearity has yet to be determined, but the need to do so has become more urgent given the non-linear effects of Pb on IQ in children. In studies with children, IQ reductions are associated with PbB, but these reductions are greater at lower as compared to higher PbBs (Canfield et al., 2003). Nor is the extent to which such non-linearity is gender specific known, since so few studies have actually evaluated gender differences following Pb exposure.

FI Performance Changes Associated with Corticosterone Changes in Females but with Frontal Cortex Dopaminergic and Serotonergic Changes in Males

FI performance changes were linearly related to corticosterone changes in females, but not in males. How corticosterone might influence FI performance is not known; such effects could occur either directly or indirectly. Increases in plasma corticosterone have been reported with reinforcement schedule shifts and extinction (Coover et al., 1971; Goldman et al., 1973), but the current study imposed no such shifts. Studies using both mineralocorticoid and glucocorticoid receptor antagonists will be required to begin to address this issue.

Backward stepwise regression analyses suggested, instead, a stronger role for frontal cortical dopamine and serotonin in mediating stress-induced FI performance changes in males (Table 1). Together, the results of the linear and stepwise regression analyses suggest a dissociation of corticosterone changes and behavioral responses to stress challenges, and instead, a neurochemically-mediated behavioral activation. The relationship between frontal cortical dopamine and serotonin and FI response to stress challenge in males is consistent with our studies demonstrating the critical role(s) of mesocorticolimbic circuits in mediating FI performance. Microinjections of dopamine into nucleus accumbens, for example, produce an inverse U-shaped dose effect curve for FI response rates (Cory-Slechta et al., 1996; Cory-Slechta et al., 1997; Cory-Slechta et al., 1998; Cory-Slechta et al., 2002). Moreover, microinjections of DA1 and DA2 receptor antagonists into nucleus accumbens combined with lidocaine administration into prelimbic or agranular insular areas of frontal cortex influence nucleus accumbens control of FI performance (Evans and Cory-Slechta, 2000). Those studies all utilized only male rats. Understanding the extent to which mesocorticolimbic mediation differs in females may assist in understanding gender-based differences in stress outcomes. As with other gender-related differences seen in this and our prior Pb-stress studies, moreover, they raise cautions about the extrapolation of findings across genders and the potential misinterpretations that may result from the use of groups that combine male and female subjects in studies of stress. That is, both female and male subjects should be included in studies of Pb+/- PS, and sex treated as a factor in the statistical analyses.

Corticosterone Changes Differed Significantly in Animals With (FI) and Without (NFI) Behavioral Testing Experience

Inclusion of NFI littermates in these studies allowed a determination of the extent to which behavioral testing per se influenced corticosterone outcomes. Marked differences were seen between FI and NFI corticosterone responses to stress challenges in both genders. In NFI control (0 ppm) females (Figure 4), corticosterone levels actually tended to increase over the course of stress challenges, whereas reductions across stress challenges were observed in FI females. Indeed, corticosterone increases in response to cold, novelty and even the final basal determination all revealed significantly higher levels in NFI than FI females. These findings suggest a sensitization of the corticosterone response by prenatal stress in NFI females and an adaptation to this effect produced by behavioral testing-associated events in FI females. A completely opposite effect was observed in males, where the FI 0 ppm males showed far higher increases in corticosterone in response to stressors than NFI counterparts (Figure 4). These findings suggest a silencing of the corticosterone response by prenatal stress in males, but its marked over-activation or sensitization in a behavioral context.

These contrasting effects in FI and NFI females and males underscore a critical role of behavioral and/or early experience/handling in the corticosterone response to stress challenges. Stress-attenuating effects of handling during the early postnatal period have been documented (Cirulli et al., 2007; Tejedor-Real et al., 2007). In this study, however, no systematic early handling was carried out, and what early handling did occur was comparable in FI and NFI offspring. Thus, these differential effects are unlikely to be related to differences in early handling per se.

Only testing on the FI schedule differed between FI and NFI groups. FI testing encompasses a complex environment with multiple components, including daily weighing, movement to and from the vivarium, food reward, operant chambers, and acquisition of new behavior. As such FI testing itself might similarly operate as a kind of ‘environmental enrichment’. Behavioral testing began at 2-3 months of age, a period during which implementation of environmental enrichment procedures in rats has been shown to be effective in reversing components of stress responses in rodents (Segovia et al., 2007), indicating its malleability. In the current study, FI testing appeared to operate as a type of enrichment in females, but as an additional stressor or provocation in males. Whether these NFI vs FI differences reflect the FI paradigm itself or the other components of the environment, and whether other behavioral paradigms would produce similar effects, cannot be ascertained, but clearly warrant additional investigation. This differential pattern of corticosterone changes in FI vs. NFI groups, nonetheless, clearly demonstrates that biochemical measures derived from non-behaviorally trained animals may be quite misleading as mechanistic explanations for subjects with a behavioral history in such experiments.

Pb and Stress Induced Alterations in HPA Axis Function Have Broad Human Health Effect Implications

These studies demonstrate that maternal Pb exposure interacts with and further modifies prenatal stress effects even at PbBs in dams as low as 11 μg/dl. Pb and stress show both congruence as risk factors in low SES populations as well as commonalities in diseases and disorders with which each has been associated. The current findings demonstrate their interactive influences on HPA axis function, and argue that studies of Pb as an isolated risk factor do not capture its full toxicity. Moreover, these findings have clear implications for risk assessment in that current screening for elevated blood Pb levels focuses on young children; the apparently permanent effects of combined maternal Pb and prenatal stress underscore the need to screen pregnant women, particularly those at risk for elevated Pb exposure with high-stress lifestyles, since postnatal only screening will not prevent such effects, and indeed, Pb exposures to fetuses may initially exceed those measured postnatally given the rise in blood Pb during pregnancy (Hertz-Picciotto et al., 2000).

Acknowledgments

Supported in part by ES05017 (D. Cory-Slechta, PI)

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Iqbal S, Muntner P, Batuman V, Rabito FA. Estimated burden of blood lead levels 5mug/dl in 1999-2002 and declines from 1988 to 1994. Environ Res. 2008 doi: 10.1016/j.envres.2008.01.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Canfield RL, Henderson CR, Cory-Slechta DA, et al. Intellectual impairment in children with blood lead concentrations below 10 ug per deciliter. N Engl J Med. 2003;348:1517–1526. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa022848. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Lanphear BP, Hornung R, Khoury J, et al. Low-level environmental lead exposure and children’s intellectual function: an international pooled analysis. Environ Health Perspect. 2005;113:894–899. doi: 10.1289/ehp.7688. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Seckl JR. Glucocorticoids, developmental ‘programming’ and the risk of affective dysfunction. Prog Brain Res. 2008;167:17–34. doi: 10.1016/S0079-6123(07)67002-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Dohrenwend BP. Social status and stressful life events. J Pers Soc Psychol. 1973;28:225–235. doi: 10.1037/h0035718. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Starfield EL. Child health and social status. Pediatrics. 1982;69:550–557. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Pappas G, Queen S, Hadden W, Fisher G. The increasing disparity in mortality between socioeconomic groups in the United States, 1960 and 1986. N Engl J Med. 1993;329:103–109. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199307083290207. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Anderson NB, Armstead CA. Toward understanding the association of socioeconomic status and health: A new challenge for the biopsychosocial approach. Psychosom Med. 1995;57:213–225. doi: 10.1097/00006842-199505000-00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Stipek JD, Ryan RH. Economically disadvantaged preschoolers: ready to learn but further to go. Dev Psychol. 1997;33:711–723. doi: 10.1037//0012-1649.33.4.711. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Munck A, Guyre PM, Holbrook NJ. Physiological functions of glucocorticoids in stress and their relation to pharmacological actions. Endocr Rev. 1984;5:25–44. doi: 10.1210/edrv-5-1-25. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Lupien SJ, King S, Meaney MJ, McEwen BS. Can poverty get under your skin? Basal cortisol levels and cognitive function in children from low and high socioeconomic status. Dev Psychopathol. 2001;13:653–676. doi: 10.1017/s0954579401003133. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Diorio D, Viau V, Meaney MJ. The role of the medial prefrontal cortex (cingulate gyrus) in the regulation of hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal responses to stress. J Neurosci. 1993;13:3839–3847. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.13-09-03839.1993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Lowy M, Gault L, Yammamato B. Adrenalectomy attenuates stress induced elevation in extracellular glutamate concentration in hippocampus. J Neurosci. 1993;61:1957–1960. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-4159.1993.tb09839.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Piazza PV, Rouge-Pont F, Deroche V, et al. glucocorticoids have state-dependent stimulant effects on the mesencephalic dopaminergic transmission. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1996;93:8716–8720. doi: 10.1073/pnas.93.16.8716. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Pokora MJ, Richfield EK, Cory-Slechta DA. Preferential vulnerability of nucleus accumbens dopamine binding sites to low-level lead exposure: Time course of effects and interactions with chronic dopamine agonist treatments. J Neurochem. 1996;67:1540–1550. doi: 10.1046/j.1471-4159.1996.67041540.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Cory-Slechta DA, O’Mara DJ, Brockel BJ. Nucleus accumbens dopaminergic mediation of fixed interval schedule-controlled behavior and its modulation by low-level lead exposure. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 1998;286:794–805. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Barrot M, Marinelli M, Abrous DN, et al. The dopaminergic hyper-responsiveness of the shell of the nucleus accumbens is hormone-dependent. Eur J Neurosci. 2000;12:973–979. doi: 10.1046/j.1460-9568.2000.00996.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Moghaddam B. Stress activation of glutamate neurotransmission in the prefrontal cortex: Implications for dopamine-associated psychiatric disorders. Biol Psychiatry. 2002;51:775–787. doi: 10.1016/s0006-3223(01)01362-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Cory-Slechta DA. The behavioral toxicity of lead: Problems and perspectives. In: Barrett JE, editor. Advances in Behavioral Pharmacology. Vol. 4. New York: Academic Press, Inc.; 1984. pp. 211–255. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Cory-Slechta DA, Weiss B. Alterations in schedule-controlled behavior of rodents correlated with prolonged lead exposure. In: Balster RL, editor. Behavioral Pharmacology: The Current Status. New York: Alan R. Liss; 1985. pp. 487–501. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Cory-Slechta DA. Schedule-controlled behavior in neurotoxicology. In: Mitchell CL, editor. Neurotoxicology, Target Organ Toxicology Series. New York: Raven Press; 1992. pp. 271–294. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Fride E, Dan Y, Feldon J, Halevy G, Weinstock M. Effects of prenatal stress on vulnerability to stress in prepubertal and adult rats. Physiol Behav. 1986;37:681–687. doi: 10.1016/0031-9384(86)90172-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.McCormick CM, Smythe JW, Sharma S, Meaney MJ. Sex-specific effects of prenatal stress on hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal responses to stress and brain glucocorticoid receptor density in adult rats. Brain Research Developmental Brain Research. 1995;84:55–61. doi: 10.1016/0165-3806(94)00153-q. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Rimondini R, Agren G, Borjesson S, Sommer W, Heilig M. Persistent behavioral and autonomic supersensitivity to stress following prenatal stress exposure in rats. Behav Brain Res. 2003;140:75–80. doi: 10.1016/s0166-4328(02)00273-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Igosheva N, Taylor PD, Poston L, Glover V. Prenatal stress in the rat results in increased blood pressure responsiveness to stress and enhanced arterial reactivity to neuropeptide Y in adulthood. J Physiol. 2007;582:665–674. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2007.130252. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Cory-Slechta DA, Virgolini MB, Thiruchelvam M, Weston DD, Bauter MR. Maternal stress modulates effects of developmental lead exposure. Environ Health Perspect. 2004a;112:717–730. doi: 10.1289/ehp.6481. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Virgolini MB, Bauter MR, Weston DD, Cory-Slechta DA. Permanent alterations in stress responsivity in female offspring subjected to combined maternal lead exposure and/or stress. Neurotoxicol. 2006;27:11–21. doi: 10.1016/j.neuro.2005.05.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Cory-Slechta DA, Virgolini MB, Rossi-George A, et al. Lifetime consequences of combined maternal lead and stress. Basic Clin Pharmacol Toxicol. 2008;102:218–227. doi: 10.1111/j.1742-7843.2007.00189.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Cabib S, Ventura R, Puglisi-Allegra S. Opposite imbalances between mesocortical and mesoaccumbens dopamine responses to stress by the same genotype depending on living conditions. Behav Brain Res. 2002;129:179–185. doi: 10.1016/s0166-4328(01)00339-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Francolin-Silva AL, Almeida SS. The interaction of housing condition and acute immobilization stress on the elevated plus-maze behaviors of protein-malnourished rats. Braz J Med Biol Res. 2004;37:1035–1042. doi: 10.1590/s0100-879x2004000700013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Cory-Slechta DA, Weiss B, Cox C. Performance and exposure indices of rats exposed to low concentrations of lead. Toxicol Appl Pharmacol. 1985;78:291–299. doi: 10.1016/0041-008x(85)90292-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Cory-Slechta DA, Weiss B, Cox C. Mobilization and redistribution of lead over the course of calcium disodium ethylenediamine tetracetate chelation therapy. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 1987;243:804–813. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Virgolini MB, Rossi-George A, Lisek R, et al. CNS effects of developmental Pb exposure are enhanced by combined maternal and offspring stress. Neurotoxicol. 2008 doi: 10.1016/j.neuro.2008.03.003. epub ahead of print. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Yi SJ, Masters JN, Baram TZ. Glucocorticoid receptor mRNA ontogeny in the fetal and postnatal rat forebrain. Mol Cell Neurosci. 1994;5:385–393. doi: 10.1006/mcne.1994.1048. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Diaz R, Sokoloff P, Fuxe K. Codistribution of the dopamine D3 receptor and glucocorticoid receptor mRNAs during striatal prenatal development in the rat. Neurosci Lett. 1997;227:119–122. doi: 10.1016/s0304-3940(97)00316-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Cory-Slechta DA. Comparative neurobehavioral toxicology of heavy metals. In: Suzuki T, editor. Toxicology of Metals. New York: CRC Press; 1996. pp. 537–560. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Pacak Ka, P M. Stressor-specificity of central neuroendocrine responses: implications for stress-related disorders. Endocr Rev. 2001;22:502–548. doi: 10.1210/edrv.22.4.0436. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Koolhaas JM, Meerlo P, De Boer SF, Strubbe JH, Bohus B. The temporal dynamics of the stress response. Neurosci Biobehav Rev. 1997;21:775–782. doi: 10.1016/s0149-7634(96)00057-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Widzowski DV, Finkelstein JN, Pokora MJ, Cory-Slechta DA. Time course of postnatal lead-induced changes in dopamine receptors and their relationship to changes in dopamine sensitivity. Neurotoxicol. 1994;15:853–865. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Cory-Slechta DA, Virgolini MB, Thiruchelvam M, Weston DD, Bauter MR. Maternal stress modulates the effects of developmental lead exposure. Environ Health Perspect. 2004b;112:717–730. doi: 10.1289/ehp.6481. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Weinstock M. Gender Differences in the Effects of Prenatal Stress on Brain Development and Behaviour. Neurochem Res. 2007 doi: 10.1007/s11064-007-9339-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Dews PB. Studies on behavior. IV. Stimulant actions of methamphetamine. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 1958;122:137–147. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Diamond DM, Bennett MC, Fleshner M, Rose GM. Inverted-U relationship between the level of peripheral corticosterone and the magnitude of hippocampal primed burst potentiation. Hippocampus. 1992;2:421–430. doi: 10.1002/hipo.450020409. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Sandi C, Rose SP. Training-dependent biphasic effects of corticosterone in memory formation for a passive avoidance task in chicks. Psychopharmacology (Berl) 1997;133:152–160. doi: 10.1007/s002130050385. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Montano MM, Wang MH, vom Saal FS. Sex differences in plasma corticosterone in mouse fetuses are mediated by differential placental transport from the mother and eliminated by maternal adrenalectomy or stress. J Reprod Fertil. 1993;99:283–290. doi: 10.1530/jrf.0.0990283. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Davis JM, Svendsgaard DJ. U-shaped dose-response curve-shaped dose-response curves: Their occurrence and implications for risk assessment. J Toxicol Environ Health. 1990;30:71–83. doi: 10.1080/15287399009531412. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Leasure JL, Giddabasappa A, Chaney S, et al. Low-level human equivalent gestational lead exposure produces sex-specific motor and coordination abnormalities and late-onset obesity in year-old mice. Environ Health Perspect. 2008;116:355–361. doi: 10.1289/ehp.10862. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Coover GD, Goldman L, Levine S. Plasma corticosterone levels during extinction of a lever-press response in hippocampectomized rats. Physiol Behav. 1971;7:727–732. doi: 10.1016/0031-9384(71)90140-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Goldman L, Coover GO, Levine S. Bidirectional effects of reinforcement shifts on pituitary adrenal activity. Physiol Behav. 1973;10:209–214. doi: 10.1016/0031-9384(73)90299-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Cory-Slechta DA, Pokora MJ, Preston RA. The effects of dopamine agonists on fixed interval schedule-controlled behavior are selectively altered by low level lead exposure. Neurotoxicol Teratol. 1996;18:565–575. doi: 10.1016/0892-0362(96)00082-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Cory-Slechta DA, Pazmino R, Bare C. The critical role of the nucleus accumbens dopamine systems in the mediation of fixed interval schedule-controlled operant behavior. Brain Res. 1997;764:253–256. doi: 10.1016/s0006-8993(97)00591-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Cory-Slechta DA, Brockel BJ, O’Mara DJ. Lead exposure and dorsomedial striatum mediation of fixed interval schedule-controlled behavior. Neurotoxicol. 2002;23:313–327. doi: 10.1016/s0161-813x(02)00059-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Evans SB, Cory-Slechta DA. Prefrontal cortical manipulations alter the effects of intra-ventral striatal dopamine antagonists on fixed-interval performance in the rat. Behavioral Brain Research. 2000;17:45–58. doi: 10.1016/s0166-4328(99)00108-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Cirulli F, Capone F, Bonsignore LT, Aloe L, Alleva E. Early behavioural enrichment in the form of handling renders mouse pups unresponsive to anxiolytic drugs and increases NGF levels in the hippocampus. Behav Brain Res. 2007;178:208–215. doi: 10.1016/j.bbr.2006.12.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Tejedor-Real P, Sahagun M, Biguet NF, Mallet J. Neonatal handling prevents the effects of phencyclidine in an animal model of negative symptoms of schizophrenia. Biol Psychiatry. 2007;61:865–872. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2006.08.033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Segovia G, Del Arco A, de Blas M, Garrido P, Mora F. Effects of an enriched environment on the release of dopamine in the prefrontal cortex produced by stress and on working memory during aging in the awake rat. Behav Brain Res. 2007;187:304–311. doi: 10.1016/j.bbr.2007.09.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Hertz-Picciotto I, Schramm M, Watt-Morse M, et al. Patterns and determinants of blood lead during pregnancy. Am J Epidemiol. 2000;152:829–837. doi: 10.1093/aje/152.9.829. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]