Abstract

We herein report the optical coherence tomography (OCT) findings in a case of chloroquine-induced macular toxicity, which to our knowledge, has so far not been reported. A 53- year-old lady on chloroquine for treatment of rheumatoid arthritis developed decrease in vision 36 months after initiation of the treatment. Clinical examination revealed evidence of retinal pigment epithelial (RPE) disturbances. Humphrey field analyzer (HFA), fundus fluorescein angiography (FFA) and OCT for retinal thickness and volume measurements at the parafoveal region were done. The HFA revealed bilateral superior paracentral scotomas, FFA demonstrated RPE loss and OCT revealed anatomical evidence of loss of ganglion cell layers, causing marked thinning of the macula and parafoveal region. Parafoveal retinal thickness and volume measurements may be early evidence of chloroquine toxicity, and OCT measurements as a part of chloroquine toxicity screening may be useful in early detection of chloroquine maculopathy.

Keywords: Chloroquine maculopathy, optical coherence tomography, retinal thickness

Ocular toxicity associated with antimalarial agents have been extensively studied since its first description in 1957 by Cambiaggi.1 Several tools have been used to detect functional loss for diagnosis including color vision, Amsler grid, Humphrey field analyzer (HFA) and multifocal electroretinography.2,3

Although the vision loss from chloroquine toxicity has been attributed to retinal pigment epithelial (RPE) changes and consequent photoreceptor loss, several animal studies have suggested that the initial retinal damage occurs in ganglion cells, and the other retinal layers are affected only later on.4 Scanning laser polarimetry has shown that there is a marked thinning of the nerve fiber layer, possibly due to ganglion cell damage.4 Optical coherence tomography (OCT) gives a good cross-sectional view of the macula and may be a good tool for the detection of anatomical evidence of chloroquine macular toxicity.5 We report the OCT findings in a case of chloroquine macular toxicity, which, to the best of our knowledge has so far not been reported.

Case Report

A 53-year-old lady, of height 152 centimeters and weighing 45 kilograms diagnosed with rheumatoid arthritis was first seen by us in April 2003 for a pre-chloroquine workup. Her vision was 20/20 N6 bilaterally. She was trichromatic (17/17) using the Ishihara isochromatic charts. Fundus examination, Amsler grid testing and HFA 10-2 were normal. Chloroquine 250 mg daily was then started.

She was seen at six-monthly intervals and advised Amsler grid self-evaluation between her scheduled eye examinations.

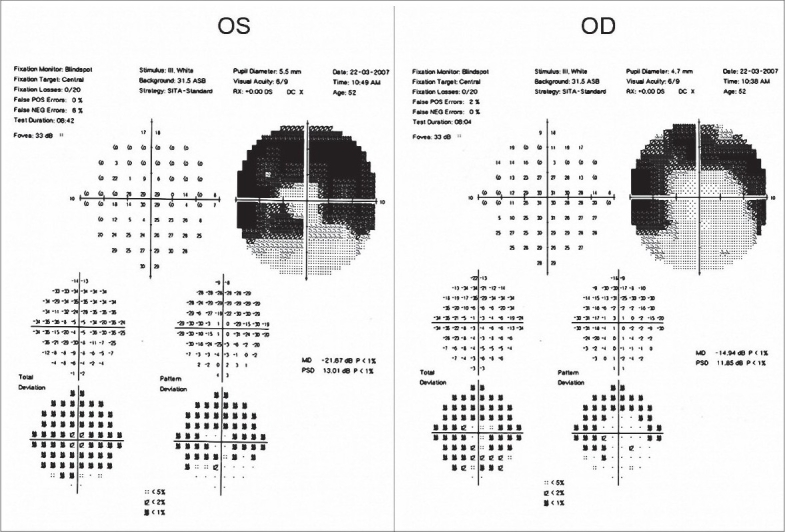

In April 2006, the vision in her left eye dropped to 20/30 N8 with no subjective change in vision. She was trichromatic, although taking longer to identify the numbers. A clinically detectable RPE disturbance was noted, more prominent in her left eye [Figures 1, 2]. Amsler grid evaluation was normal, but HFA 10-2 revealed, repeatable superior paracentral defect in both eyes [Figure 3]. Fundus fluorescein angiography (FFA) revealed RPE defects in the macular region in both eyes. A recommendation to the treating internist was made to replace chloroquine with hydroxychloroquine. At review four months later, she reported distortion of vision in both eyes, which was reflected as a small blurred area in the center of the Amsler grid and vision in both eyes of 20/30 N8

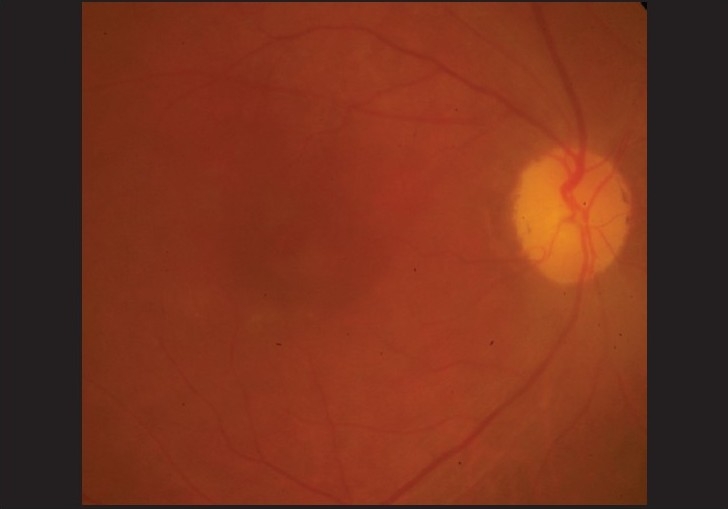

Figure 1.

Right eye fundus photograph showing clinically detectable retinal pigment epithelial changes at the macula in a patient on chloroquine therapy for rheumatoid arthritis

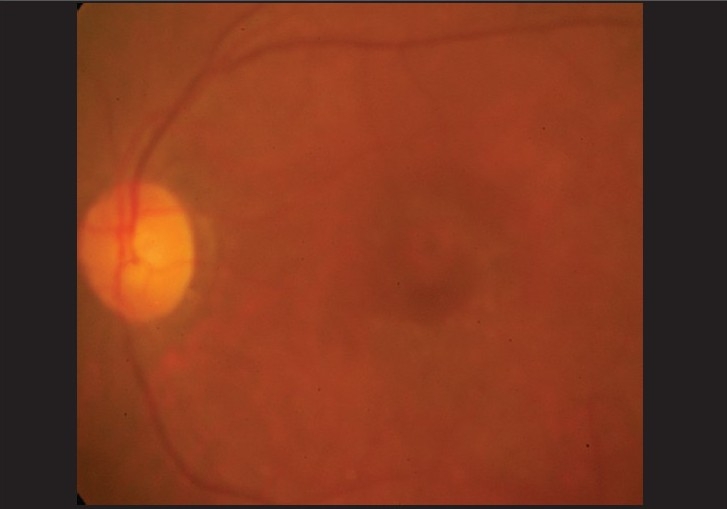

Figure 2.

Left eye fundus photograph showing clinically detectable retinal pigment epithelial changes at the macula of the same patient

Figure 3.

Humphrey Field Analyzer 10-2 program showing superior paracentral field defects in both eyes of the patient

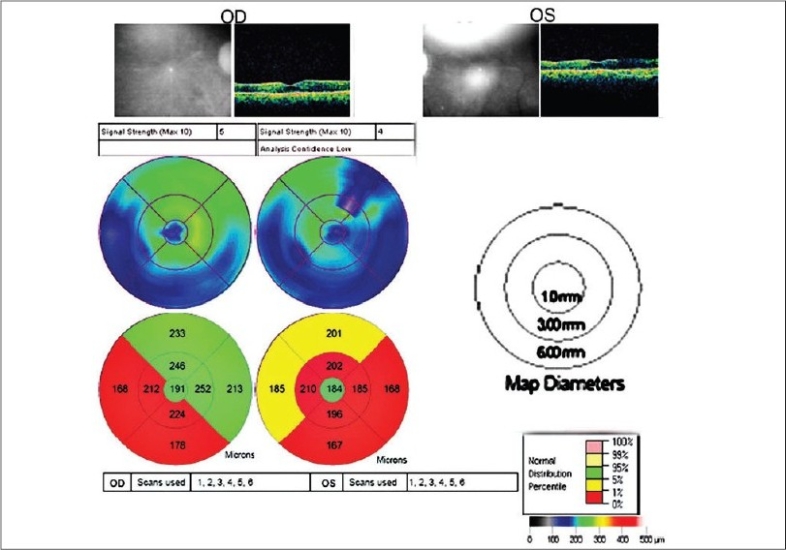

Optical coherence tomography (Stratus 4 OCT™; Carl Zeiss Meditec, Dublin, Calif) revealed a marked retinal thinning of the parafoveal region [Figure 4].

Figure 4.

Retinal thickness and volume measurements at the parafoveal region of a patient with chloroquine maculopathy

The internist was informed and hydroxychloroquine was replaced by methotrexate. Since then, her vision has remained stable at 20/30 N8.

Discussion

Chloroquine, and more recently, the apparently less toxic hydroxychloroquine, is used for long periods of time for treatment of various autoimmune disorders. Cambiaggi first described the classic RPE changes in 19571 and Hobbs in 1959 established a definite link between long-term use of chloroquine and subsequent development of retinal pathology.6

Early chloroquine retinopathy though still inadequately described, is defined as an acquired paracentral scotoma on threshold visual field testing, with no detectable retinal findings, while advanced retinopathy has associated parafoveal RPE atrophy.7 Chloroquine and its metabolites have been found in the pigmented ocular structures at concentrations much greater than in any other tissue in the body, which may explain its toxic properties in the eye.3,8 Animal studies have suggested that ganglion cell damage occurs early with choloroquine.4,8 Human pathological studies are however limited to patients with advanced maculopathy.3

Detection of resultant thinning of the ganglion cell and nerve fiber layer (NFL) would be useful in demonstrating the initial stages of toxicity, perhaps at a stage when further damage can be halted by stopping the drug at this point. The NFL measurements of the peripapillary region in patients on antimalarials by scanning polarimetry have indeed shown a significant thinning of the NFL which was dose and duration-dependent.4 However, the ganglion cell population is the densest in the macular region, and hence, toxicity of the drug would be greatest at this location. The fact that the first functional change is a paracentral scotoma, and the first observable RPE changes are seen in this area supports this assumption.7 Thus retinal thickness and volume measurements in this area may give more accurate and earlier predictions of chloroquine toxicity, perhaps even before the scotoma develops. The OCT, with its high resolution provides measurements of the retinal thickness and volume, both in the peripappillary area as well as at the macular region. It also gives information on the status of the retinal pigment epithelium, clearly revealing RPE defects. In addition, the limitations of the scanning laser polarimeter with respect to inaccuracies related to corneal and lens birefringence are not present.

A recent study using a research prototype of a high-speed ultra-high-resolution OCT reported discontinuity or loss of perifoveal photoreceptor inner segment/outer segment junctions and thinning of the outer nuclear layer in 15 patients receiving hydroxychloroquine.5 This instrument is however not available as yet for general clinical use.

In our patient [Figure 2], the fovea (central circle) is of normal thickness while the perifoveal (inner circle) and peripheral (outer circle), are thinned mainly temporally and inferiorly. This is in agreement with the universally accepted early superior paracentral scotoma, also seen in this patient [Figure 1].

Although reports in the older literature on chloroquine toxicity had suggested that the cumulative dose of chloroquine was the critical factor for toxicity, current evidence suggests that cumulative dosage and duration of therapy are relatively unimportant and that the crucial index is daily dosage normalized by lean body weight.7,9 In this patient, the dose of chloroquine she was on clearly exceeded the recommended daily dose of 4 mg/kg/day.10 This is probably why she developed maculopathy just 36 months after starting the chloroquine therapy for her rheumatoid arthritis.

Long-term prospective studies may determine when retinal thinning starts in patients on antimalarials, and whether irreversible paracentral field defects could be prevented if antimalarials are stopped on first detection of thinning.

References

- 1.Cambiaggi A. Unusual ocular lesions in a case of systemic lupus erythromatosis. Arch Ophthalmol. 1957;57:451–53. doi: 10.1001/archopht.1957.00930050463019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Easterbrook M. Detection and prevention of maculopathy associated with antimalarial agents. Int Ophthalmol Clin. 1999;39:49–57. doi: 10.1097/00004397-199903920-00005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Neubauer AS, Stiefelmeyer S, Berninger T, Arden GB, Rudolph G. The multifocal pattern electroretinogram in chloroquine retinopathy. Ophthalmic Res. 2004;36:106–13. doi: 10.1159/000076890. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bonanomi MT, Dantas NC, Medeiros FA. Retinal nerve fibre layer thickness measurements in patients using chloroquine. Clin Exp Ophthalmol. 2006;34:130–6. doi: 10.1111/j.1442-9071.2006.01167.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Rodriguez-Padilla JA, Hedges TR, 3rd, Monson B, Srinivasan V, Wojtkowski M, Reichel E, et al. High-speed ultra-high-resolution optical coherence tomography findings in hydroxychloroquine retinopathy. Arch Ophthalmol. 2007;125:775–80. doi: 10.1001/archopht.125.6.775. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Hobbs HE, Sorsby A, Freedman A. Retinopathy following chloroquine therapy. Lancet. 1959;2:478–80. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(59)90604-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Browning DJ. Hydroxychloroquine and chloroquine retinopathy: Screening for drug toxicity. Am J Ophthalmol. 2002;133:649–56. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9394(02)01392-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ramsey MS, Fine BS. Chloroquine toxicity in the human eye: Histopathologic observations by electron microscopy. Am J Ophthalmol. 1972;73:229–35. doi: 10.1016/0002-9394(72)90137-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Mackenzie AH. Dose refinements in long-term therapy of rheumatoid arthritis with antimalarials. Am J Med. 1983;75:40–5. doi: 10.1016/0002-9343(83)91269-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Marmor MF, Carr RE, Easterbrook M, Farjo AA, Mieler WF. Recommendations on screening for chloroquine and hydroxychloroquine retinopathy: A report by the American Academy of Ophthalmology. Ophthalmology. 2002;109:1377–82. doi: 10.1016/s0161-6420(02)01168-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]