Abstract

Sequence-based searches identified a new family of genes in proteobacteria, named rnk, that shares high sequence similarity with the C-terminal domains of the Gre-factors (GreA, GreB) and the Thermus/Deinococcus anti-Gre-factor Gfh1. We solved the X-ray crystal structure of Escherichia coli Rnk at 1.9 Å-resolution using the anomalous signal from the native protein. The Rnk structure strikingly resembles those of E. coli GreA, GreB, and Thermus Gfh1, all of which are RNAP secondary channel effectors, and all of which have a C-terminal domain belonging to the FKBP fold. Rnk, however, has a much shorter N-terminal coiled-coil. Rnk does not stimulate transcript cleavage in vitro, nor does it reduce the lifetime of the complex formed by RNAP on promoters. We show that Rnk competes with the Gre-factors and DksA (another RNAP secondary channel effector) for binding to RNAP in vitro, and although we found that the concentration of Rnk in vivo was much lower than that of DksA, it was similar to that of GreB, consistent with a potential regulatory role for Rnk as an anti-Gre factor.

Introduction

Gre-factors (GreA and GreB) 1 promote transcription elongation in bacteria by stimulating the intrinsic endonucleolytic transcript cleavage activity of the RNA polymerase (RNAP) 2. Gre-factors are required for the natural progression of RNAP in vivo 3; 4. In addition to rescuing arrested complexes and increasing the overall elongation rate 5, Gre factors may play a role in modulating RNAP behavior at pause signals 3, increasing transcriptional fidelity 6, and in stimulating promoter clearance 7; 8; 9.

Gre factors comprise two structural/functional domains 10. The N-terminal domain (NTD) consists of a 60 Å-long coiled-coil that extends into the RNAP secondary channel to the RNAP catalytic site and is critical for stimulating transcript cleavage activity 11; 12; 13. The globular C-terminal domain (CTD) consists of a β-sheet flanked by a small α-helix 10; 11; 12. The CTD, which is important for binding RNAP, interacts with the β’ subunit of RNAP at the entrance of the RNAP secondary channel 10; 11; 12; 13. Biochemical and structural data have converged to a model whereby conserved acidic residues at the Gre coiled-coil tip stabilize the binding of the second Mg2+-ion in the RNAP active site required for the endonucleolytic cleavage reaction 13; 14; 15; 16.

Similar to the Gre-factors, DksA is organized into two structural domains. It has a long coiled-coil similar in structure to that of the Gre-factors, but its second domain is distinct and contains a Zn-finger motif 17. Like the Gre-factors, DksA binds to RNAP with its coiled-coil structural element placed directly in the RNAP secondary channel (17; 18; I. Toulokhonov, R.L.G., unpublished data). DksA is essential for control of rRNA promoters at all times in bacterial growth, including following nutrient starvation, when it cooperates with the alarmone ppGpp to regulate expression from many operons during the stringent response 19; 20. Recent studies have shown that GreB can fulfill some roles of DksA in vitro, allowing rRNA promoters to sense changes in the concentrations of ppGpp and the first NTP in the transcript when the dksA gene is deleted 21.

In addition to a GreA homolog, the hyperthermophiles Thermus thermophilus (Tth) and Thermus aquaticus (Taq) possess another Gre-factor homolog, Gfh1, that lacks transcript cleavage activity and competes with GreA for RNAP binding 22. This anti-Gre factor contains domains structurally similar to GreA 10; 23; 24; 25. Crystal structures of Taq and Tth Gfh1 revealed a large conformational change compared with Escherichia coli (Ec) GreA, affecting the relative orientation of the coiled-coil and the C-terminal domains. Biochemical data suggested that Gfh1 binds RNAP in a conformation similar to that observed for the Gre-factors, but that it switches to an alternate conformation at high pH 10; 13; 25. Conserved inter-domain contacts that may stabilize the GreA-like conformation of Gfh1 were revealed by modeling Gfh1 in its GreA-like conformation 23.

Our database searches for Gre-factor/Gfh1 homologs revealed another family of proteins in proteobacteria, known as regulator of nucleoside kinase (Rnk), that shares substantial sequence similarity with the Gre and anti-Gre factors. Mutations in rnk drastically reduce the level of nucleoside diphosphate kinase (Ndk) in Ec, which is an important enzyme involved in maintaining cellular NTP and dNTP pools 26. By an unknown mechanism, Ec Rnk is also a multicopy suppressor of an alginate-deficient phenotype in Pseudomonas aeruginosa caused by deletion of algQ (also called algR2; 27).

We present here the 1.9 Å-resolution crystal structure of Ec Rnk. The structure reveals a globular CTD that is structurally conserved with the Gre and anti-Gre factors, but an NTD containing a much shorter coiled-coil. The CTD belongs to the FKBP fold first identified in the immunophilin family 28. The FKBP fold has been found in proteins with a wide variety of functions, from a peptidyl-prolyl isomerase to proteins that make protein/protein interactions within large molecular assemblies. Structural features of the Gre/Gfh1/Rnk FKBP domain show that it belongs to the latter group. We further demonstrate that Ec Rnk competes for binding and function with the RNAP secondary channel effectors GreA, GreB, and DksA in vitro. Unlike Gre-factors 10; 11, however, Rnk does not crosslink with the 3'-end of the RNA transcript in the RNAP ternary elongation complex (TEC), stimulate transcript cleavage, or decrease the lifetime of the RNAP-promoter complex 21. The cellular concentration of Rnk in both log and stationary phase is comparable to that of GreB, and only a few-fold lower than GreA, suggesting that Rnk might compete with, and thereby regulate, Gre factor activity in vivo. We found that Rnk is dispensable for regulation of rRNA transcription initiation in vivo, consistent with its much lower cellular concentration than DksA. However, we also were unable to detect effects of Rnk on Gre factor function in transcription from the tnaC promoter in vivo. Our results thereby suggest a tantalizing, although unconfirmed, role for Rnk in vivo as an anti-Gre factor.

Results

Identification of Rnk proteins as a new family of Gre factor homologs

The anti-Gre factor Gfh1 has only been found in the Thermus/Deinoccocus phylum. Searching for Gfh1 homologs using the program Ballast 29, we found proteins sharing significant sequence similarity in a region covering the CTD (residues 79 to 151) of Taq Gfh1. The Gfh1 homologs belong to the nucleoside diphosphate kinase regulator family (Rnk), with the closest homolog from Geobacter sulfurreducens (expectation value 1×10−9). In an inverse search using Ec Rnk, elongation factors were found immediately after Rnk family members (elongation factor Q82T10_niteu : expectation value 1×10−28, ballast rank 11, blast rank 19).

During our search, we found that the Rnk proteins seem to be limited to gram negative proteobacteria (Figure S1). Ec Rnk (sw:P40679) is a 136 amino acid protein that shares significant sequence identity with Taq Gfh1: 22.79% identity between the full length proteins, and 28.9% identity over their CTDs (Ec Rnk residues 48 to 136, Taq Gfh1 residues 79 to the C-terminus). By comparison, Ec Rnk shares 22.06% sequence identity with Ec GreA and 15.44% with Ec GreB (Gfh1 shares 25 % identity with Ec GreA). The N-terminal residues of Rnk (residues 1 to 47) do not exhibit significant sequence similarity with the Gre-factor NTDs (residues 1 to 76).

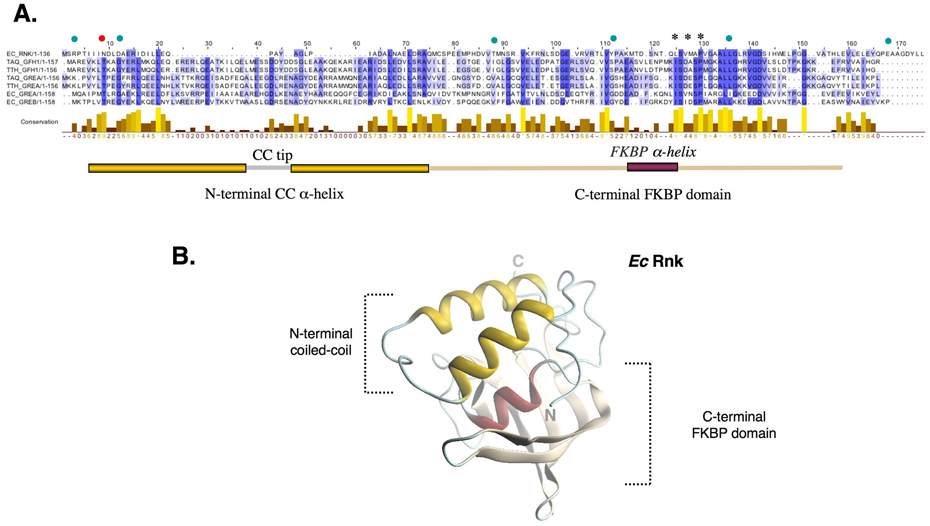

Secondary structure prediction for Rnk using PHD 30 revealed that the CTD of Rnk possesses secondary structure elements similar to the Gre and anti-Gre factors. The secondary structure elements for the Rnk NTD are also predicted to be similar to the Gre factors, but the coiled-coil helices are much shorter (Figure 1A).

Figure 1. Ec Rnk is a Gre-factor/Gfh1 homolog.

(A) Primary sequence alignment of Rnk with selected Gre and anti-Gre factors. Residues are shaded according to their sequence conservation using the program Jalview 43. Limits of the NTD and CTD are indicated below the sequences. Stars above the sequences mark conserved residues in the FKBP domain part of a flat hydrophobic surface around Pro93, a residue involved in RNAP binding in Gre factors 40. Green dots indicate residues involved in Rnk inter-domain interactions. The red dot indicates a position involved in the stabilization of Gre and anti-Gre conformation observed so far in all known structures of Gre factors.

(B) The Ec Rnk crystal structure is displayed in ribbon representation. The N-terminal coiled-coil appears in yellow, the FKBP domain is made of a β-sheet (beige) flanked by a small α-helix (red).

Ec Rnk structure

The purified, native Ec Rnk protein was crystallized by hanging-drop vapor diffusion. The crystals diffracted beyond 1.9 Å-resolution and were also very resistant to radiation damage. This allowed us to collect a highly redundant dataset with relatively low energy X-rays (1.74 Å wavelength; Table 1) to facilitate detection of the sulfur anomalous signal directly from the native protein. The asymmetric unit contains two Rnk molecules as well as 10 sulfate and 2 chloride ions (Figure S2A). The chloride ions bind in a small hydrophobic pocket of the protein, whereas the sulfate ions bind to arginine residues on the surface of the protein, with two of them sitting between the two molecules in the asymmetric unit. The overall structural organization of Rnk is similar to the Gre-factors (Figure 1B), with an N-terminal coiled-coil and a C-terminal globular domain. As expected from the sequence similarity, the C-terminal globular domain superimposes closely on that of the Gre factors. The CTDs of Ec Rnk and Ec GreA superimpose with a root-mean-square-deviation (rmsd) of 1.96 Å over 68 Cα positions. The CTDs of Ec Rnk and Taq Gfh1 superimpose with an rmsd of 4.1 Å over 54 Cα positions, a larger value due to conformational variations in flexible loops connecting the secondary structural elements. The N-terminal coiled-coil of Rnk is about 22 Å shorter than the Gre or Gfh1 coiled-coil (Figure 2A).

Table 1.

Crystallographic Analysis

| Diffraction data | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Data set | Wavelength (Å) | Resolution (Å) | Number of reflections (Total/Unique) | Completeness | I/σ | Rsyma (%) | Redundancy | No. of sites |

| Sulfur | 1.74326 | 20-1.91 (1.98-1.91) | 787,643/44,841 | 98.8 (97.5) | 57.3 (13.7) | 6.2 (23.3) | 17.2 | 18 |

| Crystal space group C2221 | ||||||||

| Unit cell a = 68.46 Å, b = 133.39 Å, c = 66.02 Å | ||||||||

| Solvent content 55.85 % (2 molecules in the asymmetric unit) | ||||||||

| Figure of Meritb (30-2.3 Å) 0.25 | ||||||||

| Refinement | ||||||||

| Resolution 20.0 - 1.91 Å | ||||||||

| Rcryst / Rfreec (%) 21.2 / 23.7 % | ||||||||

| rmsd bonds 0.006 Å | ||||||||

| rmsd angles 1.40° | ||||||||

| The final model contains 270 residues, 282 water molecules, 10 sulfates ions, 2 chloride ions | ||||||||

Rsym = Σ|I-<I>|/ΣI, where I is observed intensity and <I> is average intensity obtained from multiple observations of symmetry-related reflections.

Figure of merit as calculated by SOLVE 45.

Rcryst = Σ∥Fobserved|-|Fcalculated∥/Σ|Fobserved|, Rfree = Rcryst calculated using 9.3% random data omitted from the refinement.

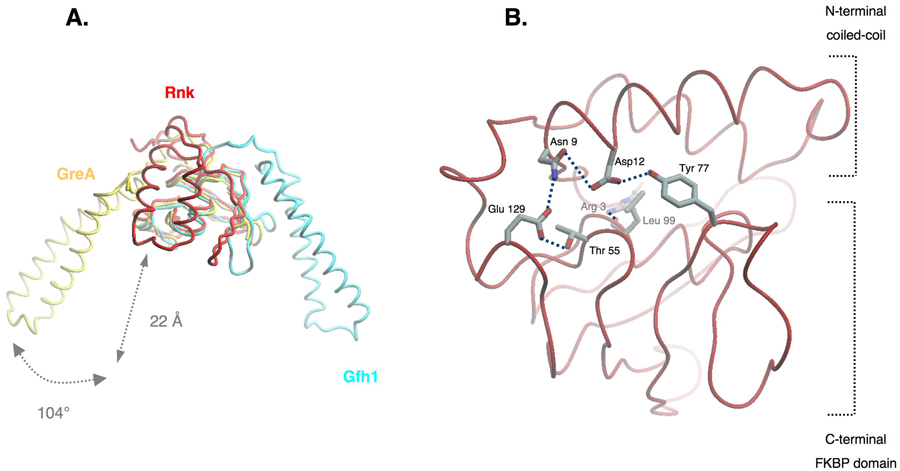

Figure 2. Rnk interdomain orientation.

(A) Ec Rnk (red) superposition with Ec GreA (yellow; 10 and Taq Gfh1 23. The structures have been superimposed on the C-terminal FKBP domain. The Rnk coiled-coil is rotated 104° away from the coiled-coil position observed in Ec GreA. The Rnk coiled-coil is 22 Å shorter than the GreA and Gfh1 coiled-coils.

(B) Ec Rnk interdomain hydrogen bond network. Side chains of N-terminal residues Arg3, Asn9, and Asp12 interact with amino-acids Thr55, Tyr77, Leu99, and Glu129 of the C-terminal FKBP domain.

Comparison of the Ec GreA, Taq Gfh1, and Ec Rnk structures, all aligned by their C-terminal domains, reveals three different orientations of the N-terminal coiled-coil domains with respect to the CTDs. The Rnk NTD is rotated 104° with respect to the GreA NTD, while the Gfh1 NTD is rotated 178° 23 (Figure 2A). The Ec Rnk NTD is maintained against its CTD by a hydrogen bond network involving the side chains of Asn9 and Asp12 from the NTD, and Thr55, Tyr77, and Glu129 from the CTD (Figure 2B). Several residues are also engaged in main chain/main chain interactions, and the side chain of Arg3 in the N-terminal arm of the protein interacts with the carbonyl group of Leu99 in the CTD. Additional hydrophobic interactions at the interface between the two domains of the protein stabilize the overall conformation.

Structural homology with the FKBP domain

While the NTD is variable at the sequence and structural level between the Gre and Rnk families, the CTD is well conserved even when comparing distant species. Proteins with the closest structural similarity to the Rnk CTD, identified from a search using DALI (http://www.ebi.ac.uk/dali), aside from the Gre factors (Ec GreA, Z=11.0, PDB entry PDB:1GRJ), are proteins belonging to the FKBP fold: the FK506-binding proteins FKBP51 (Z=6.0, PDB:1KT0) and FKBP12 (Z=5.8, PDB:1FKJ), Rv2118c, a methyltransferase from mycobacterium (Z=5.3, 1I9G), a domain of the Trigger factor (Z=4.7, PDB:1HXV), a prolylisomerase Mip (Z=4.9, PDB:1FD9), and SurA, a molecular chaperone (Z=3.8, PDB:1M5Y).

The commonality among all these proteins is a core structure comprising an antiparallel β-sheet wrapped around a central α-helix of two-turns. The number of β-strands in the FKBP β-sheet can vary from 4 for Rv2118c, SurA, and the Trigger factor, to 5 for FKBP51, FKBP12, Mip, and the Gre factors (where the N-terminal arm of the protein is considered part of the C-terminal β-sheet). Depending on the protein, the β-sheet can adopt slightly different spatial orientations relative to the α-helix. This structural relationship between the Ec GreA CTD and the FKBP domain was previously mentioned in the structural study of hpar14 31, a parvulin-like human peptidyl-prolyl isomerase (Dali score with Rnk CTD Z=2.4, PDB:1EQ3).

Initially, FKBP domains were named for their ability to bind the immunosuppressive drug FK506 28. The domain is found associated with a variety of protein functions. Some display peptidyl-prolyl cis/trans isomerase activity (PPIase), like FKBP12 32, the Trigger factor 33, and Mip 34, while some have evolved into protein/protein interaction domains, like the Rv2118c methyltransferase 35, and one of the FKPB domains in FKBP51 36 and SurA 37.

FKBP proteins that display PPIase activity present a hollow surface that leads into the core of the structure to the N-terminal part of the central α-helix. This cavity is surrounded by conserved residues that are able to bind oligopeptide substrates, and in some cases the inhibitor FK506 (Figure S3A). The Trigger factor, although possessing weak PPiase activity, does not bind FK506 due to subtle structural changes that lead to steric hindrance 33. In contrast, FKBP proteins without PPIase activity do not show significant sequence homology with the PPIase family, and the cavity is either filled by loops (Figure S3B) or flattened like in the Gre factors, exposing the N-terminal end of the core α-helix (Figure S3A). Gre factors share no significant sequence similarity with most PPIases. Together with divergent Gre factor sequences, however, weak sequence similarity can be detected with the Trigger factor from D. radiodurans (TIG_deira) in a PSI-BLAST search 38 after the first iteration (score 0.91) in the C-terminal FKBP domain (from Ec Rnk residue 58 to 120).

Rnk competes with transcription factors that bind near the RNAP secondary channel in vitro

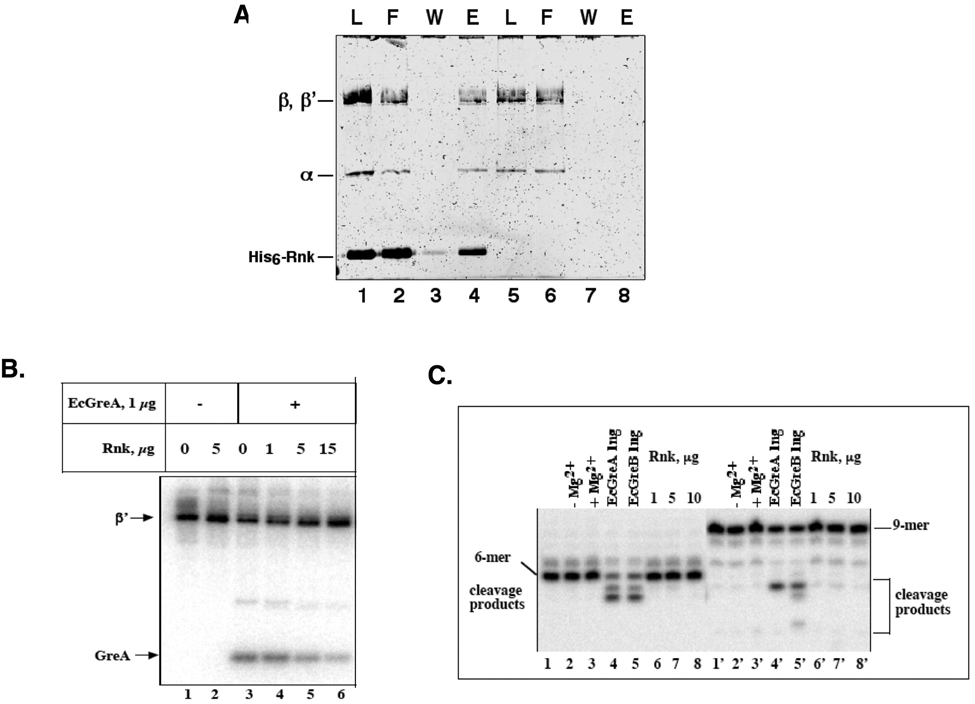

The sequence (Figure 1A) and structural (Figure 2A) similarity of Rnk with the Gre-factors and Gfh1, which bind RNAP at the entry to the secondary channel 13, suggest that Rnk may also interact with RNAP in a similar manner. Therefore, we tested directly whether Rnk interacts with RNAP. Immobilized hexa-histidine-tagged (His6)-Rnk clearly co-immobilized Ec core RNAP (Figure 3A, lane 4), while RNAP alone was not detectably retained on the column (Figure 3A, lane 8), confirming an Rnk/RNAP protein/protein interaction. Native polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis analysis also indicated Rnk binding to RNAP (data not shown).

Figure 3. Rnk binds RNAP competitively with Gre-factors.

(A) Binding of core RNAP to Ni2+-NTA immobilized His6-Rnk. His6-Rnk and a molar excess of core RNAP (Load, lane 1) were incubated with Ni2+-NTA agarose beads in buffer containing 0.5 mM imidazole. The beads were washed with buffer containing 0.5 mM imidazole (Flow-throuth, lane 2), then washed with buffer containing 10 mM imidazole (Wash, lane 3), then eluted with buffer containing 100 mM imidazole (Elution, lane 4). The presence of core RNAP in the Elution (lane 4) indicates binding. A separate control experiment shows that core RNAP was not immobilized in the absence of His6-Rnk (lanes 5–8).

(B) Functional (RNA 3'-end crosslinking) competition of Rnk with Gre-factors. TECs with crosslinkable 8-N3-AMP incorporated in the 3'-end of the 9mer RNA transcript were prepared and crosslinked with GreA in the presence of increasing amounts of Rnk (lanes 3 to 6). The presence of Rnk decreases GreA crosslinking to the RNA.

(C) Rnk lacks transcript cleavage activity. TECs containing 6 (lanes 1–8) and 9 (lanes 1’–8’) nt-long nascent RNAs were prepared on the rrnB P1 promoter and incubated with Gre-factors or Rnk in the presence of Mg2+.

If Rnk binds RNAP at the entrance to the RNAP secondary channel, as suggested by the sequence and structural similarity with Gre-factors and Gfh1, then Rnk should bind RNAP competitively with Gre-factors. It has been previously shown that GreA and GreB interact, or are in close proximity to, the RNA transcript 3'-end since the Gre-factors crosslink to probes incorporated into the RNA 3'-end in TECs (Figure 3B, lane 3; 10; 11. The RNA does not crosslink to Rnk (Figure 3B, lane 2), presumably because the short coiled-coil of Rnk is unable to enter the RNAP secondary channel and reach the 3'-end of the RNA transcript. Addition of Rnk reduces the efficiency of RNA crosslinking to GreA, indicating that Rnk binding to RNAP displaces GreA in a competitive manner (Fig. 3B, lanes 4–6). The results of additional experiments (native gel electrophoresis, data not shown; gel filtration experiments, Figure S4) corroborate the conclusion that Rnk and Gre-factor binding to RNAP is mutually exclusive. Although Rnk exhibits sequence (Figure 1A), structural (Figure 2A), and functional (competitive binding) similarity with the Gre-factors, Rnk, in contrast to the Gre-factors, does not stimulate transcript cleavage in TECs containing either 6-mer or 9-mer RNA transcripts (Figure 3C).

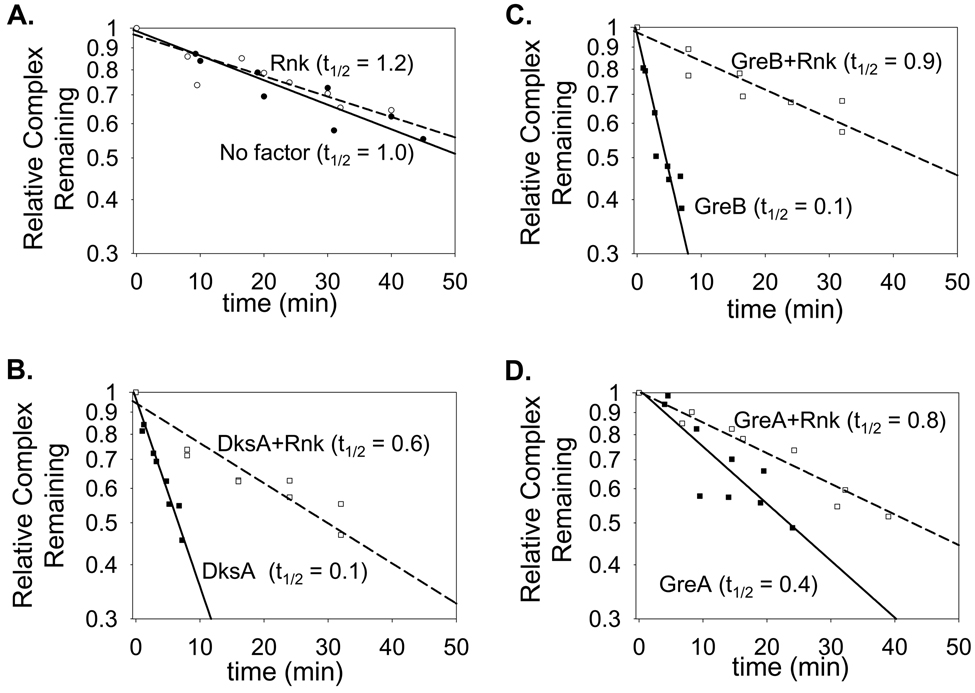

Finally, using a filter-binding assay, we tested whether Rnk reduced the lifetime of the RNAP-promoter complex in a manner similar to DksA and the Gre factors (Figure 4). DksA, GreB, and GreA each decreased the absolute half-life of the competitor-resistant complex formed between RNAP and promoter DNA (compare absolute half-lives of the complexes formed by RNAP in the absence of factor with those in the presence of DksA, GreB, and GreA) 20; 21; 39. In contrast, Rnk had no effect on the half-life of the complex (Figure 4A).

Figure 4. Functional (reduction of open promoter complex half-life) competition of Rnk with secondary channel effectors.

The half-life of the RNAP-lacUV5 competitor-resistant complex was determined in the absence (filled symbols, solid lines) and presence (open symbols, dashed lines) of 0.5 µM Rnk with (A) buffer (circles), (B) 0.5 µM DksA (squares), (C) 0.5 µM GreB (diamonds), or (D) 2.5 µM GreA (triangles) using a filter binding assay (see Materials and Methods). The decay curves show the fraction of complexes remaining versus time after heparin addition. Curves for the lifetimes without factors (t1/2 ratio = 1.0) are shown in each panel for comparison. Although the curves are displayed in separate panels for clarity, all were carried out at the same time under the same conditions. Thus, the absolute half-lives can be compared directly. The value provided in parenthesis (t1/2 ratio) for each curve is the half-life of the competitor-resistant complex relative to that of the same complex in the absence of factor.

We also tested whether Rnk would alter the effects of DksA and the Gre factors on promoter complex lifetime. Whereas DksA or GreB alone decreased the lifetime of the complex ~10-fold (from 53 min to 5–7 min), an equimolar concentration of Rnk either partially reduced (DksA) or eliminated (GreB) the effect of the factor on half-life (Figure 4B, 4C). As reported previously 21, more GreA than DksA or GreB was required to reduce the lifetime of the promoter complex, and the decrease caused by GreA was smaller than that caused by GreB or DksA (Figure 4D), suggesting that GreA binds to the promoter complex with lower affinity than GreB or DksA. Not surprisingly, Rnk, even at less than equimolar concentrations, essentially eliminated the effect of GreA on promoter lifetime (Figure 4D). We conclude that Rnk can compete with DksA and the Gre factors for binding to the promoter complex in vitro.

Rnk likely is dispensable for rRNA and tnaC regulation in vivo

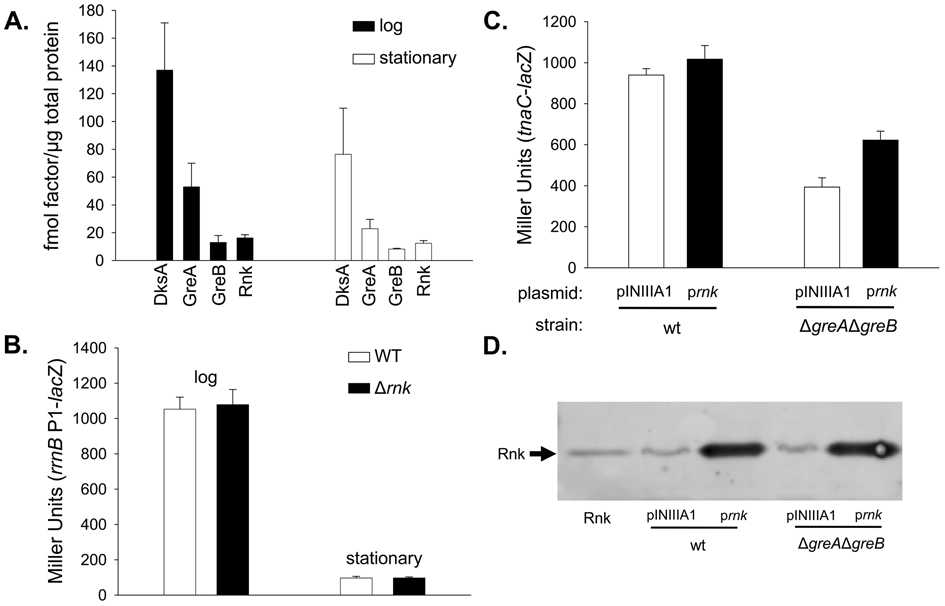

The competitive effects observed at comparable concentrations of Rnk, DksA, and Gre factors in vitro would only affect promoter complexes in vivo if the concentrations of the factors were also comparable as were solution conditions and macromolecular crowding. Therefore, we measured Rnk, DksA, GreA, and GreB levels in cell lysates using Western blots. The Rnk concentration was ~9-fold lower than that of DksA in log phase and ~6-fold lower in stationary phase (Figure 5A). Since an equal concentration of Rnk was insufficient to completely compete away DksA function in vitro (suggesting the concentration used in vitro was not saturating; Figure 4B), and the concentration of Rnk present in vivo was much lower than that of DksA, Rnk therefore is unlikely to compete with DksA for RNAP and affect rRNA promoter activity in vivo (see also below).

Figure 5. Cellular levels of Rnk are insufficient to affect DksA function, but are similar to levels of GreB.

(A) The in vivo concentration of Rnk is lower than DksA and GreA, but comparable to GreB in log and stationary phase. Quantitative Western blots were performed on cell lysates of a wild-type strain (RLG5950) grown in MOPS medium (see Materials and Methods) in log phase (OD600~0.4) and stationary phase (OD600>4.5). Concentrations (fmol factor/µg total protein) were determined from at least 3 separate experiments (except for Rnk in stationary phase which was determined from 2 experiments).

(B) The rnk gene is dispensable for rRNA regulation in vivo. β-galactosidase activities (expressed in Miller Units) were determined in strains containing lacZ fused to rrnB P1. Promoter activities were assayed in wild-type (RLG3739) and Δrnk (RLG8255) cells growing in LB at 30°C in log phase (OD600~0.4 after ~4 generations of growth) and stationary phase (24 hr). β-galactosidase activities from ≥4 cultures were averaged and standard errors are shown.

(C). Rnk does not inhibit Gre factor function in tnaC expression in vivo. β-galactosidase activities (expressed in Miller Units) were determined in strains containing lacZ fused to the tnaC promoter region. Promoter activities were assayed in wild-type (RLG9166) and ΔgreAΔgreB (RLG9168) cells carrying an empty vector, pINIIIA1 (pRLG6332), or a vector expressing Rnk from the IPTG-inducible lpp-lac promoter, pRnk (pRLG9163). Cells were grown in LB at 30°C with 100 µg/ml ampicillin and 1 mM IPTG, and β-galactosidase activity was assayed in log phase (OD600~0.4 after ~4 generations of growth). β-galactosidase activities from ≥4 cultures were averaged and standard errors are shown. Similar trends were observed in stationary phase (date not shown)

(D). Rnk was overexpressed from the IPTG inducible lpp-lac promoter. Rnk levels were measured by Western blots performed on cell lysates from the cultures assayed for β-galactosidase activity described above. 40 ng of purified Rnk, ~39 µg of total protein from the cultures carrying the empty vector, pINIIIA1 (pRLG6332), and ~7.8 µg of total protein from the cultures carrying prnk (pRLG9163) were probed with anti-Rnk antibody. A representative blot is shown. Similar results were observed in stationary phase (data not shown).

In contrast, Rnk was only slightly less abundant than GreA and approximately equimolar with GreB in both log and stationary phase (Figure 5A). Equimolar concentrations of Rnk and GreB were sufficient to eliminate GreB function in vitro (Figure 4C), and Rnk was able to eliminate GreA function even when GreA was in 5-fold molar excess in vitro (Figure 4D). Assuming that the specific activities of the purified proteins are comparable and that the relative affinities of the Gre factors and Rnk for the promoter complex reflect their relative affinities for RNAP complexes during promoter escape and transcription elongation (where Gre factors are thought to influence transcription), Rnk might be expected to compete with GreB and perhaps even GreA in vivo.

To address directly whether Rnk competes with DksA or the Gre factors in cells, we examined the effects of Rnk in vivo on transcription from two promoters, the rRNA promoter rrnB P1 and the tryptophanase promoter tnaC. It was shown previously that DksA negatively regulates rrnB P1, and therefore transcription from rrnB P1 increases when the dksA gene is inactivated 20. In contrast, Gre factors facilitate promoter escape from tnaC, and therefore inactivation of the gre genes decreases the activity of this promoter 9.

We measured rrnB P1-lacZ activity by β-galactosidase assay in a wild-type strain and in a strain deleted for rnk (Δrnk). The rrnB P1 activity was identical in a wild-type and Δrnk strain in both log and stationary phase (Figure 5B). This result is consistent with the prediction above that Rnk would not compete with DksA for rRNA promoter complexes in vivo because Rnk is much less abundant that DksA in vivo. However, we have not ruled out that there might be some condition in vivo where the two factors are in competition.

Because Rnk and the Gre factors are much closer in concentration in vivo, we chose a promoter that had been shown previously to require Gre factor activiy for a more rigorous test of potential competition between Rnk and a secondary channel binding factor in vivo. We further increased the chance that the Rnk concentration would be sufficient to compete with the Gre factors by expressing Rnk from an IPTG-inducible promoter (we confirmed that Rnk was greatly overexpressed under these conditions; ~60-fold; Figure 5D).

In aggreement with the previous conclusion that GreA and GreB facilitate escape of RNAP from the tnaC promoter 9, we found that the activity of a tnaC-lacZ fusion decreased more than 2-fold in a ΔgreAΔgreB strain (Fig. 5C, compare open bars). However, even under these conditions, Rnk did not reduce tnaC-lacZ activity; i.e. overexpression of Rnk did not mimic the effect of inactivation of the gre genes (Figure 5C). Therefore, we are unable to conclude at this time that the competition between Rnk and the Gre factors observed in vitro actually occurs in vivo. For unknown reasons, overexpression of Rnk appeared to increase tnaC promoter activity very slightly (~1.5-fold) in a ΔgreAΔgreB strain (Figure 5C, right). Clearly, further studies will be needed to determine promoters (if any) where Rnk competes with Gre factors and reduces expression in vivo.

Discussion

We report here the structure of Rnk, the relative concentrations of Rnk and GreA, GreB, and DksA (three other factors that bind to the RNAP secondary channel), and the results of competition experiments with these factors performed in vitro and in vivo. Our results strongly suggest that although Rnk itself appears to have no direct effect on transcription, it shares important RNAP binding determinants with Gre factors, and it binds to RNAP with similar or greater apparent affinity in vitro, suggesting that Rnk might inhibit Gre factor function under conditions yet-to-be identified.

The relative orientation of the N-terminal coiled-coil and C-terminal globular domains in the crystal structure of Ec GreA was maintained by inter-domain hydrogen bonds involving conserved residues in both of the protein domains 10. A model of Taq Gfh1 suggested that these same residues could also stabilize a GreA-like conformation 23. This observation was supported by in vitro experiments showing the existence of several conformations in solution for Gfh1 25. Conserved residues in Rnk, including Asp12, Tyr77 and Glu129, stabilize the Rnk conformation in the Rnk crystal structure. These positions are not conserved in GreA and Gfh1. Rnk Asn9, located at the end of the N-terminal arm, is at the core of the interdomain hydrogen bond network. Interestingly, Ec Rnk Asn9 is replaced by a Thr or Ser in most of the Rnk homologs. It is in the same position as GreA Thr7 and Gfh1 Thr8 involved in similar networks 23.

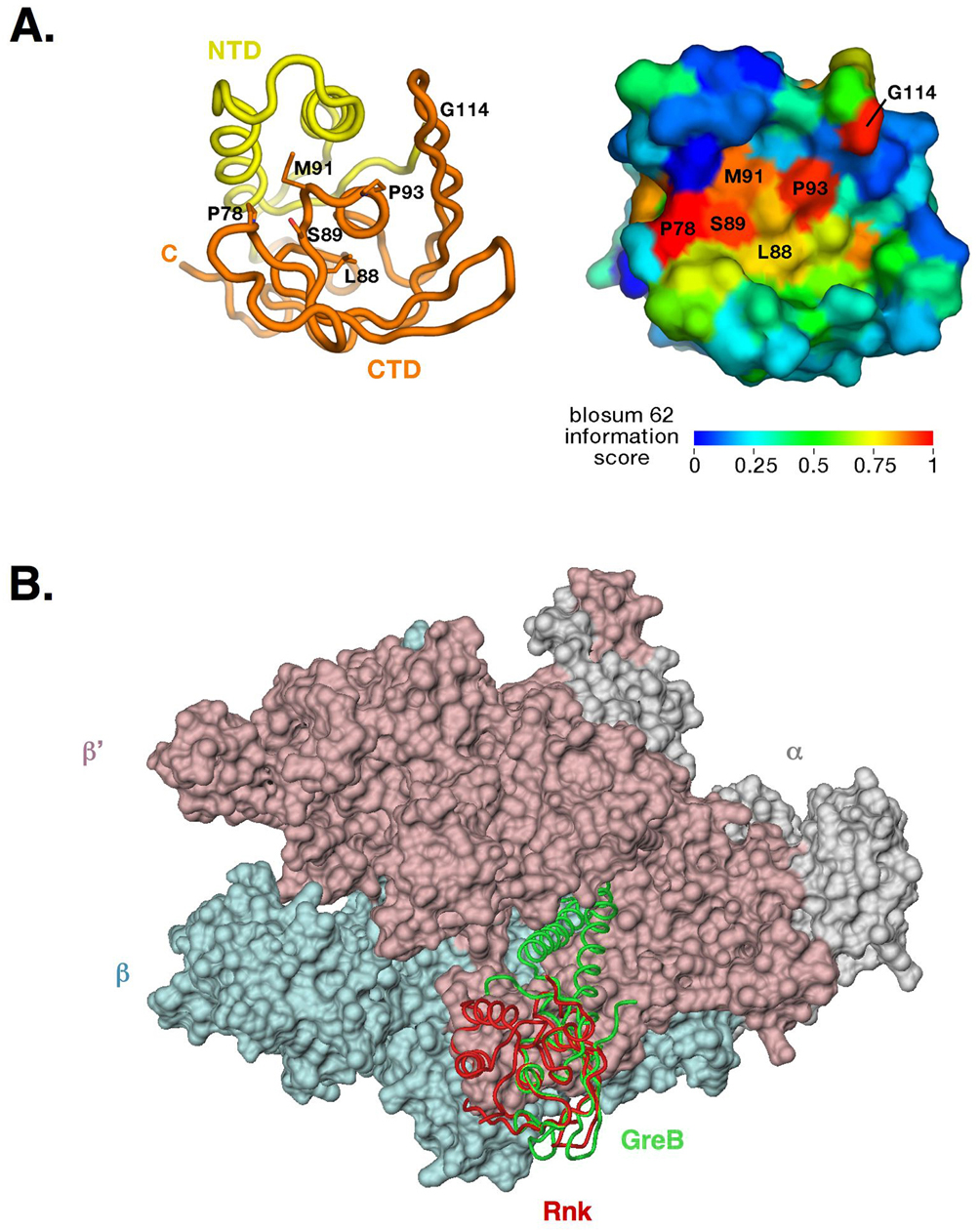

Mapping sequence similarity from an alignment of 45 Rnk homologs (Figure S1) onto the structure reveals a single cluster of surface-exposed, highly conserved residues (Figure 6A). The cluster contains Ec Rnk residues Pro78, Leu88, Ser89, Met91, Pro93, and Gly114. Interestingly, some of the corresponding residues are also conserved and surface-exposed in the Gfh1 and Gre-factors (Figure 1A). Specifically, the residue corresponding to Ec Rnk Pro78 is conserved in the Gfh1s, but is a Ser in the Gre-factors. The residue corresponding to Ec Rnk Leu88 is highly conserved as a bulky hydrophobic residue among all the factors. Finally, the residues corresponding to Ec Rnk Ser89 and Pro93 are strictly conserved among all three families of factors (Rnk, Gfh1, GreA/B). Mutational studies indicate strictly conserved Ec GreB Pro123 (corresponding to Ec Rnk Pro93) plays a role in RNAP binding 40. Moreover, the juxtaposition of this surface against the RNAP in the structure-based model of the RNAP/Gre-factor complex is consistent with this region playing a role in the protein/protein complex 13. These findings suggest that this surface-exposed patch of conserved residues plays a similar functional role (mediating the protein/protein complex with RNAP) among the three families of factors.

Figure 6. Potential RNAP binding surface of Rnk.

(A). Rnk C-terminal FKBP domain conserved residues. (left) Conserved residues in the Rnk family (see alignment Figure S1) are highlighted on the RNK structure (worm representation with NTD in yellow and FKBP domain in orange) and (right) in a molecular surface representation colored according to the BLOSUM score.

(B). RNAP model with Rnk (red backbone worm) and GreB (green backbone worm) C-terminal FKBP domains superposed 13.

We generated Rnk single mutations of P93A, L88A and S89A as well as combination of double mutants and a triple mutant P93A+L88A+S89A to assess their binding to RNAP. Native gel shift analyses failed to show any notable effect of the mutations when compared to wild-type Rnk (data not shown). Considering the highly hydrophobic nature of this surface, it is most likely that multiple interactions contribute to RNAP binding and substitution to alanine might not be drastic enough to disrupt the hydrophobic contacts.

A model of Rnk bound to the TEC (Figure 6B) predicts a minor clash at the extremity of a flexible loop in the Rnk CTD (residues 139 to 150). However this loop displays a wide range of conformations in the structures of Gfh1 and Rnk, and it is completely disordered in Ec GreA (Figure S2B), suggesting that this flexible element might be able to adapt to the RNAP surface upon binding. If the Rnk coiled-coil adopts the same relative orientation when bound to RNAP as the Ec GreA coiled-coil (Figure 6B), the model predicts that the Rnk coiled-coil would be too short to reach backtracked RNA in the RNAP secondary channel, in agreement with the absence of crosslinking (Figure 3B).

Previous biochemical studies of the Gre factors have shown that truncations of the Gre factors containing only the CTD are still able to competetively bind RNAP with full-length GreA and GreB, thereby inhibiting transcription cleavage activity 12. Thus, the presence of a long coiled-coil domain is not a pre-requisite for anti-Gre activity. Interactions between the CTD of the Gre factors with the β’G lineage-specific insert in Ec have been detected in several studies 14; 41. The Taq and Tth anti-Gre factor Gfh1 possesses a coiled-coil of the same length as Taq and Tth GreA factor. It is possible that additional interactions provided by the Ec β’G insert, absent in Thermus, compensates for the shorter coiled-coil of its anti-Gre factor Rnk. On the other hand, although only the presence of the CTD is sufficient for inhibiting Gre-stimulated transcript cleavage activity, the presence of a long coiled-coil in Thermus anti-Gre Gfh1 might ensure stronger binding and more efficient cleavage inhibition in extreme environmental conditions.

In summary, although we have demonstrated that Ec Rnk binds to RNAP and competes in vitro with three known secondary channel effectors, GreA, GreB, and DksA, we have been unable as yet to establish the importance of this competition in vivo. Likewise, regulation of transcript cleavage activity by Thermus anti-Gre factors has also been demonstrated in vitro, but the nutritional/environmental conditions under which this modulation of Gre factor functions in vivo remain unclear. Nevertheless, our results suggest that regulation of Gre-stimulated transcript cleavage might be a general feature in transcription that extends beyond hyperthermophilic bacteria.

Materials and Methods

Sequence analysis

Rnk homologs were identified using Ballast (http://bips.ustrasbg.fr/PipeAlign/jump_to.cgi?Ballast+noid) 29. Sequence alignments were edited using Seqlab and identity percentages were calculated with the identity matrix from the GCG Wisconsin package 42. Secondary structure predictions were calculated on the web interface with the program PHD (http://npsa-pbil.ibcp.fr/cgi-bin/npsa_automat.pl?page=/NPSA/npsa_phd. html) 30. The most redundant sequences were removed out of the multiple sequence alignment (identity cutoff 0.95). Six Rnk homologs with large N-terminal insertions were omitted from the final alignment: spt_q73j81, spt_q4kb20, spt_q7w4h3, spt_q5qw19, spt_q3n261 and spt_q8yc75. The resulting sequence alignment (Figure S1) was adjusted manually using Seqlab 42. The sequences were colored according to their sequence identity conservation using Jalview 43.

The PSI-BLAST search against Swiss-Prot, TRembl and Microbial complete proteomes databases was performed through the website interface (http://myhits.isb-sib.ch/cgi-bin/psi_blast) using Rnk FKBP domain residues 52 to 124 and the BLOSUM-62 matrix (E-value inclusion 1.10−3, E value report 1, clusters matches with approximate level of identity 70%).

Cloning the rnk gene

The rnk gene was amplified by the polymerase chain reaction (PCR) from Ec genomic DNA with primers: ggagtacatatgtccagaccaactatcatcat (forward), gcactcgagttaaagcaggtagtcgccagcag (reverse). The 430 bp DNA fragment was blunt-end cloned into pT7Blue blunt vector (Novagen), and recombinants containing the rnk gene in the correct orientation with respect to the T7 promoter were selected.

The rnk gene was excised from pT7Blue by NdeI and BamHI restriction endonucleases, and cloned into the pET11a expression vector (Novagen) treated with the same enzymes. To generate Rnk with an N-terminal His6-tag, the same NdeI-BamHI DNA fragment containing the rnk gene was cloned into the pET28a expression vector.

Rnk Purification and Crystallization

The pET11a plasmid producing Ec Rnk was transformed into Ec BL21(DE3). Colonies were harvested directly from the plates and used to inoculate a 6 L culture. Cells at OD600nm=0.8 were induced with 0.5 mM IPTG for 3 hours at 37°C. The cells were lysed using a French Press in 80 ml of TGED buffer (20 mM Tris-HCl, pH 8.0, 5% glycerol, 0.1 mM EDTA, 1 mM DTT) plus 100 mM NaCl and 0.1 mM PMSF. After 50 min centrifugation at 14000 rpm, the pellet was resuspended in the TGED + 500 mM NaCl and lysed again. The supernatant was recovered after a second centrifugation and protein was precipitated with ammonium sulfate (36% w/v) at 4°C. After centrifugation, the precipitate was dissolved in TGED + 50 mM NaCl and loaded on a 20 ml Q sepharose column (GE Healthcare). The protein was eluted by a gradient from 50 mM to 1 M NaCl over 10 column volumes. Fractions containing Rnk (determined by SDS-PAGE) were pooled and concentrated to 5 ml using a Vivaspin 5000 Da cutoff centrifugal concentrator. The sample was loaded on a Superdex 75 gel filtration column (GE Healthcare) equilibrated in TGED + 500 mM NaCl. The purified fractions were frozen and stored at −80°C with 15% glycerol.

Individual fractions were dialyzed against 20 mM Tris-HCl, pH 8.0, 50 mM NaCl, 1 mM DTT, and concentrated separately to 9 mg/ml. Crystals grew by vapour diffusion in a couple of days at 22°C in Hampton Natrix Screen condition 1 (50 mM MES, pH 5.6, 10 mM MgCl2, 2.0 M LiSO4). Microseeding was used to obtain large single crystals, with the final well conditions being refined to 50 mM MES, pH 5.6, 10 mM MgCl2, 1.5 M LiSO4. For cryocrystallography, the crystals were dunked in a cryosolution containing only 2.5 M LiSO4 and frozen in liquid ethane.

Structure determination

Frozen Rnk crystals diffracted beyond 2 Å-resolution on an X-ray home source. A native dataset was collected to 2 Å-resolution at NSLS beamline X9A (Table 1). A highly redundant dataset (Sulfur, Table 1) was collected from a single crystal at the iron edge to observe the sulfur anomalous signal from the native protein. The data were analyzed using XPREP 44. Phasing was performed with SOLVE 45 between 20 and 1.91 Å using the sulfur sites found with SHELX 44; 46. Out of the 18 anomalous sites found by SHELX, 4 were sulfate ions bound at the surface of the protein, and 2 were chloride ions. Density modification performed with DM using non-crystallographic two-fold symmetry 47 yielded a very clear map and most of the main chain was built with ArpWarp 48. Loops and side chains were built manually in O. The structure was refined to 1.91 Å using CNS 49 with the anomalous data processed with Scalepack 50. The final model (R=21.2%, Rfree=23.7 %) consists of two copies of Rnk, 282 water molecules, 10 sulfate ions, and 2 chloride ions. PROCHECK 51 revealed no residues in the disallowed regions of the Ramachandran plot.

Biochemical Assays

Ni2+-NTA agarose binding assay

Binding reactions (50 µl) contained approximately 5 pmol of core RNAP plus 75 pmol of His6-Rnk (Figure 3A, lanes 1–4) or no Rnk (Figure 3A, lanes 5–8) in binding buffer (20 mM Tris-HCl, pH 7.9, 125 mM NaCl, 0.5 mM imidazole). Reactions were incubated for 10 min. at room temperature, then added to 15 µl of Ni2+-NTA agarose beads (Qiagen; pre-equilibrated with binding buffer) and further incubated for 10 min. at room temperature with gentle mixing of the beads. The beads were pelleted by brief centrifugation, and unbound material in the supernatant was withdrawn. The beads were then washed three times with 1 ml of binding buffer, then eluted with 30 µl binding buffer + 100 mM imidazole. The protein samples were precipitated with 7% trichloroacetic acid and analyzed by SDS-PAGE (Figure 3A).

TEC preparation

All TECs were prepared by using a PCR-amplified 202-bp DNA fragment (−152 to +50 bp) containing the Ec rrnB P1 promoter 1; 52. TECs containing a 6-nt transcript (TEC6=CpApCpCpApC) were prepared by incubating 7.3 pmol of the promoter DNA fragment for 10 min at 37°C with 30 pmol of RNAP, BSA (1 mg/ml), 1 mM CpA, 10 µM ATP, and 1 µM [α-32P]CTP (3000 Ci/mmol) in 35 µL of transcription buffer (40 mM Tris acetate, pH 7.9, 30 mM KCI, 10 mM MgCl2). TECs containing a 9-nt transcript (TEC9=CpApCpCpApCpUpGpA) were obtained by chain extension of unlabelled TEC6 with 10 µM UTP, 10 µM ATP, and 1 µM [α-32P]GTP (3000 Ci/mmol) for 5 min at 37°C. TEC9 containing 8-N3(azido)AMP at the RNA 3'-terminus was obtained by chain extension of TEC6 with 10 µM UTP, 100 µM 8-N3-ATP, and 1 µM [α-32P]GTP (3000 Ci/mmol) for 5 min at 37°C. The complexes were purified by gel filtration on Quick-Spin G-50 columns in 10 mM Tris-HCl, pH 8.0, 1 mM EDTA.

Competetive crosslinking assay

Combinations of Rnk and GreA (as specified in Figure 3B) were added to TEC9 containing 8-N3-AMP at the RNA 3'-terminus, and incubated for 10 min at 37°C. Photocrosslinking was performed by UV-radiation at 310 nm for 20 min on ice 10. Reactions were terminated by the addition of an equal volume of SDS gel-loading buffer (2x) and analyzed by Tris-Tricine SDS-16%-PAGE followed by autoradiography and quantification by PhosphorImagery.

Transcript cleavage reactions

Reactions were performed in 10 µl of transcription buffer containing 2.5 nM TEC6 or TEC9 and other factors as specified (Figure 3C; nothing, Mg2+, GreA, GreB, or Rnk) for 10 min at 37°C. After incubation, 10 µl of formamide buffer was added, and the samples were analyzed by urea-23%-PAGE, visualized by autoradiography, and quantified using a PhosphorImager.

RNAP-promoter complex decay assays

RNAP-promoter complex decay assays were performed as described 21. Half-lives of RNAP-promoter complexes (Figure 4) were determined using a filter-binding assay 53. Briefly, approximately 0.2 nM of a 242 bp XhoI restriction fragment containing the lacUV5 promoter (lac sequence endpoints −60 to +40) from pRLG4264 was 32P end-labeled and incubated with 10 nM RNAP in transcription buffer (40 mM Tris HCl pH 7.9, 10 mM MgCl2, 1 mM DTT, 0.1 mg/ml BSA) containing 100 mM NaCl and the concentration of Rnk, DksA, GreB, GreA, or storage buffer indicated (Figure 4 legend) at 30 ° C for 20 min. Heparin (to 10 µg/ml) was added, aliquots were removed at the indicated times, and RNAP-promoter complexes were captured on nitrocellulose filters. The radioactivity retained was determined by phosphorimaging, and half-lives were calculated as described 53.

Promoter activity measurements in vivo

Construction of promoter-lacZ fusions on monolysogens of phage λ and β-galactosidase assays were performed as described 21. Briefly, promoter fusions were created by in vitro ligation of an rrnB P1 promoter fragment (endpoints −66 to +9 with respect to the transcription start site) to purified phage DNA arms containing the lacZ gene, followed by phage packaging and infection, or by in vivo recombination of a tnaC promoter (endpoints −189 to +21) into phage λ DNA carrying lacZ. Strains containing or lacking the rnk gene or the greA and greB genes were grown in LB for ~4 generations to an OD600 of ~0.4 (for log phase) or for ~24 hr to an OD600 of ~5.0 (stationary phase). Where indicated, cells carried an empty plasmid vector, pINIIIA1 (RLG6332), or a plasmid expressing Rnk from the IPTG-inducible lpp-lac promoter, pRnk (pRLG9163), and were grown in the presence of 100 µg/ml ampicillin. pRnk was constructed by cloning the rnk coding region (from 19 bp upstream of the AUG to 29 bp downstream of the stop codon) into pINIIIA1 (pRLG6332) between the XbaI and HindIII sites, as described 20. Cells were harvested, chilled on ice for ~20 min, lysed by sonication, and β-galactosidase activity was determined by standard methods 53. The greA and greB deletions were as described 21. The rnk strain (Δrnk) was generously provided by K. Datsenko and B. Wanner (Purdue University) and was constructed using Red-mediated recombination as described previously 9; 54. Details are available on request.

Quantitative Western blots

Western blots were performed as described 21. Protein concentrations were determined from 50–100 ml cultures grown in a MOPS-based minimal medium containing 0.4% glycerol, 40 µg/ml each of tryptophan and tyrosine, and 80 µg/ml each of the other 18 amino acids at 30°C and from the LB cultures used for β-galactosidase assays. After growth to the indicated optical densities (see above) and 20 min on ice, cells were harvested by centrifugation, suspended in ≤1 ml of 10 mM Tris-HCl, pH 7.9, 1 mM EDTA, 5% glycerol, 0.1 mM PMSF, lysed by sonication, and centrifuged to remove insoluble material. The total soluble protein concentration was determined with Bradford Assay Reagent using BSA as a standard. A range of purified DksA, GreA, GreB, and Rnk concentrations was used to construct standard curves. Lysates and standards were separated on 4–12% SDS-polyacrylamide gels (Invitrogen), transferred electrophoretically to PVDF membranes (Bio-Rad), and Western blots were performed as described 20. For detection of DksA, GreA, GreB, and Rnk, ~5 µg, ~40 µg, ~100 µg, and ~50 µg protein lysate were used, respectively. Rabbit polyclonal anti-DksA antiserum was a generous gift from D. Downs (UW-Madison) and was precleared with total lysate from a strain lacking dksA. Mouse monoclonal anti-GreA, anti-GreB, and anti-Rnk antisera were produced by NeoClone, Inc (Madison, WI). An HRP-conjugated secondary antibody (specific to rabbit IgG for polyclonal or to mouse IgG for monoclonal antibodies; Santa Cruz Biotechnology) was detected using ECL+ reagent (GE Healthcare). Western blots were scanned with a Typhoon phosphorimager [GE Healthcare, 520 BP 40 Cy2, ECL+ Blue family (emission), ECL+ excitation (laser)], quantified with ImageQuant (Molecular Dynamics), and protein amounts in the cell lysates were interpolated from the standard curve.

Supplementary Material

Primary sequence homologs of Rnk were identified using Ballast (29). A short NTD as well as overall high sequence identity were criteria used to determine wether the homologs belong to the Rnk family.

A. Rnk crystal asymmetric unit content. The two Rnk molecules in the asymmetric unit appear in grey. Five sulfates ions per molecule are bound to surface arginines. Chloride ions are located in a hydropobic pocket at the tip of the coiled-coil.

B. FKBP domain flexible loops. Ec Rnk, Ec GreA and Taq Gfh1 are superposed on their C-terminal FKBP domain. Flexible loops are colored in red (Rnk), yellow (GreA) and cyan (Gfh1). The GreA loop appearing as a dotted line was disordered in the crystal structure (10). The flexibility in this particular loop might allow conserved residues in the FKBP domain to face the RNAP β’ coiled-coil.

A. Rnk’s FKBP domain structural superposition with FKBP12. Rnk FKBP domain (in red) has been superposed on FKBP12 (in green) on the small α-helix region revealing a deeper surface in FKBP12. This cavity accomodates peptides during the PPiase reaction and is able to bind the immunosuppressive drug FK506 (90° view).

B. Rnk’s FKBP domain structural superposition with FKBP51. Rnk FKBP domain (in red) has been superposed on the central FKBP domain of FKBP51 on the small α-helix region (in green, other domains of the protein have been omitted for clarity). This domain of FKBP51 doesn’t have any PPiase activity. The cavity leading to the core small α-helix is closed by a loop.

Rnk displaces GreA from complexes with RNAP core. 32P-labeled GreA was combined with RNAP core and run on a Superose 6 gel-filtration column. In the top trace, the radioactive peak eluting at 18 minutes contains RNAP and corresponds to the RNAP/GreA complex. The peak eluting after 22 min is free 32P-GreA. The bottom trace is a negative control, where 32P-GreA was combined with Thyroglobulin (MW 660 kDa). Traces in the middle contained, in addition to RNAP and 32P-GreA, increasing amounts of Rnk (the molar ratios of 32P-GreA and Rnk are indicated).

Acknowledgements

We thank K. Datsenko and B. Wanner for making the rnk mutant strain available in advance of publication and C. Villers for technical assistance. Figures were generated with DINO (http://www. dino3d.org). National Institutes of Health (GM37048 to R.L.G., GM59295 to K.S., and GM61898 to S.A.D.); University of Wisconsin (University of Wisconsin Distinguished Graduate Student Research Fellowship to S.T.R.).

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Accession Numbers

Coordinates and structure factors have been deposited in the Protein Data Bank with accession number 3BMB.

References

- 1.Borukhov S, Sagitov V, Goldfarb A. Transcript cleavage factors from E. coli. Cell. 1993;72:459–466. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(93)90121-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Fish RN, Kane CM. Promoting elongation with transcript cleavage stimulatory factors. Biochim. Biophys. Acta. 2002;1577:287–307. doi: 10.1016/s0167-4781(02)00459-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Marr MT, Roberts JW. Function of transcription cleavage factors GreA and GreB at a regulatory pause site. Mol. Cell. 2000;6:1275–1285. doi: 10.1016/s1097-2765(00)00126-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Toulme F, Mosrin-Huaman C, Sparkowski J, Das A, Leng M, Rahmouni AR. GreA and GreB proteins revive backtracked RNA polymerase in vivo by promoting transcript trimming. EMBO J. 2000;19:6853–6859. doi: 10.1093/emboj/19.24.6853. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Borukhov S, Lee J, Laptenko O. Bacterial transcription elongation factors: new insights into molecular mechanism of action. Mol Microbiol. 2005;55:1315–1324. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.2004.04481.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Erie DA, Hajiseyedjavadi O, Young MC, von Hippel PH. Multiple RNA polymerase conformations and GreA: control of the fidelity of transcription. Science. 1993;262:867–873. doi: 10.1126/science.8235608. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Hochschild A. Gene-specific regulation by a transcript cleavage factor: facilitating promoter escape. J. Bacteriol. 2007;189:8769–8771. doi: 10.1128/JB.01611-07. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Hsu LH, Vo NV, Chamberlin MJ. Escherichia coli transcript cleavage factors GreA and GreB stimulate promoter escape and gene expression in vivo and in vitro. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 1995;92:11588–11592. doi: 10.1073/pnas.92.25.11588. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Stepanova E, Lee J, Ozerova M, Semenova E, Datsenko K, Wanner BL, Severinov K, Borukhov S. Analysis of promoter targets for Escherichia coli transcription elongation factor GreA in vivo and in vitro. J. Bacteriol. 2007;189:8772–8785. doi: 10.1128/JB.00911-07. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Stebbins CE, Borukhov S, Orlova M, Polyakov A, Goldfarb A, Darst SA. Crystal structure of the GreA transcript cleavage factor from Escherichia coli. Nature. 1995;373:636–640. doi: 10.1038/373636a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Koulich D, Orlova M, Malhotra A, Sali A, Darst SA, Goldfarb A, Borukhov S. Domain organization of transcript cleavage factors GreA and GreB. J. Biol. Chem. 1997;272:7201–7210. doi: 10.1074/jbc.272.11.7201. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Koulich D, Nikiforov V, Borukhov S. Distinct functions of N- and C-terminal domains of GreA, an Escherichia coli transcript cleavage factor. J. Mol. Biol. 1998;276:379–389. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.1997.1545. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Opalka N, Chlenov M, Chacon P, Rice WJ, Wriggers W, Darst SA. Structure and function of the transcription elongation factor GreB bound to bacterial RNA polymerase. Cell. 2003;114:335–345. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(03)00600-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Laptenko O, Lee J, Lomakin I, Borukhov S. Transcript cleavage factors GreA and GreB act as transient catalytic components of RNA polymerase. EMBO J. 2003;23:6322–6334. doi: 10.1093/emboj/cdg610. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Sosunov V, Sosunova E, Mustaev A, Bass I, Nikiforov V, Goldfarb A. Unified two-metal mechanism of RNA synthesis and degradation by RNA polymerase. EMBO J. 2003;22:2234–2244. doi: 10.1093/emboj/cdg193. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Sosunova E, Sosunov V, Kozlov M, Nikiforov V, Goldfarb A, Mustaev A. Donation of catalytic residues to RNA polymerase active center by transcription factor Gre. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2003 doi: 10.1073/pnas.2536698100. in press. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Perederina A, Svetlov V, Vassylyeva M, Tahirov T, Yokoyama S, Artsimovitch I, Vassylyev D. Regulation through the secondary channel - structural framework for ppGpp-DksA synergism during transcription. Cell. 2004;118:297–309. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2004.06.030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Nickels BE, Hochschild A. Regulation of RNA polymerase through the secondary channel. Cell. 2004;118:281–284. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2004.07.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Paul BJ, Berkmen MB, Gourse RL. DksA potentiates direct activation of amino acid promoters by ppGpp. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2005;102:7823–7828. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0501170102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Paul BJ, Barker M, Ross W, Schneider D, Webb C, Foster J, Gourse R. DksA: A critical component of the transcription intiiation machinery that potentiates the regulation of rRNA promoters by ppGpp and the initiating NTP. Cell. 2004;118:311–322. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2004.07.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Rutherford ST, Lemke JJ, Vrentas CE, Gaal T, Ross W, Gourse RL. Effects of DksA, GreA, and GreB on transcription initiation: insights into the mechanisms of factors that bind in the secondary channel of RNA polymerase. J Mol Biol. 2007;366:1243–1257. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2006.12.013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Hogan BP, Hartsch T, Erie DA. Transcript cleavage by Thermus thermophilus RNA polymerase. Effects of GreA and anti-GreA factors. J. Biol. Chem. 2002;277:967–975. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M108737200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Lamour V, Hogan BP, Erie DA, Darst SA. Crystal structure of Thermus aquaticus Gfh1, a Gre-factor homolog that inhibits rather than stimulates transcript cleavage. J. Mol. Biol. 2006;356:179–188. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2005.10.083. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Symersky J, Perederina A, Vassylyeva MN, Svetlov V, Artsimovitch I, Vassylyev DG. Regulation through the RNA polymerase secondary channel. Structural and functional variability of the coiled-coil transcription factors. J Biol Chem. 2006;281:1309–1312. doi: 10.1074/jbc.C500405200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Laptenko O, Kim SS, Lee J, Starodubtseva M, Cava F, Berenguer J, Kong XP, Borukhov S. pH-dependent conformational switch activates the inhibitor of transcription elongation. Embo J. 2006;25:2131–2141. doi: 10.1038/sj.emboj.7601094. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Shankar S, Schlictman D, Chakrabarty AM. Regulation of nucleoside diphosphate kinase and an alternative kinase in Escherichia coli: role of the sspA and rnk genes in nucleoside triphosphate formation. Mol Microbiol. 1995;17:935–943. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.1995.mmi_17050935.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Schlictman D, Shankar S, Chakrabarty AM. The Escherichia coli genes sspA and rnk can functionally replace the Pseudomonas aeruginosa alginate regulatory gene algR2. Mol Microbiol. 1995;16:309–320. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.1995.tb02303.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Van Duyne GD, Standaert RF, Karplus PA, Schreiber SL, Clardy J. Atomic structure of FKBP-FK506, an immunophilin-immunosuppressant complex. Science. 1991;252:839–842. doi: 10.1126/science.1709302. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Plewniak F, Thompson JD, Poch O. Ballast: blast post-processing based on locally conserved segments. Bioinformatics. 2000;16:750–759. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/16.9.750. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Rost B, Sander C. Prediction of protein structure at better than 70% accuracy. J. Mol. Biol. 1993;232:584–599. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.1993.1413. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Sekerina E, Rahfeld JU, Muller J, Fanghanel J, Rascher C, Fischer G, Bayer P. NMR solution structure of hPar14 reveals similarity to the peptidyl prolyl cis/trans isomerase domain of the mitotic regulator hPin1 but indicates a different functionality of the protein. J Mol Biol. 2000;301:1003–1017. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.2000.4013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Van Duyne GD, Standaert RF, Karplus PA, Schreiber SL, Clardy J. Atomic structures of the human immunophilin FKBP-12 complexes with FK506 and rapamycin. J Mol Biol. 1993;229:105–124. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.1993.1012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Vogtherr M, Jacobs DM, Parac TN, Maurer M, Pahl A, Saxena K, Ruterjans H, Griesinger C, Fiebig KM. NMR solution structure and dynamics of the peptidyl-prolyl cis-trans isomerase domain of the trigger factor from Mycoplasma genitalium compared to FK506-binding protein. J Mol Biol. 2002;318:1097–1115. doi: 10.1016/S0022-2836(02)00112-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Riboldi-Tunnicliffe A, Konig B, Jessen S, Weiss MS, Rahfeld J, Hacker J, Fischer G, Hilgenfeld R. Crystal structure of Mip, a prolylisomerase from Legionella pneumophila. Nat Struct Biol. 2001;8:779–783. doi: 10.1038/nsb0901-779. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Gupta A, Kumar PH, Dineshkumar TK, Varshney U, Subramanya HS. Crystal structure of Rv2118c: an AdoMet-dependent methyltransferase from Mycobacterium tuberculosis H37Rv. J Mol Biol. 2001;312:381–391. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.2001.4935. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Sinars CR, Cheung-Flynn J, Rimerman RA, Scammell JG, Smith DF, Clardy J. Structure of the large FK506-binding protein FKBP51, an Hsp90-binding protein and a component of steroid receptor complexes. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2003;100:868–873. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0231020100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Bitto E, McKay DB. Crystallographic structure of SurA, a molecular chaperone that facilitates folding of outer membrane porins. Structure. 2002;10:1489–1498. doi: 10.1016/s0969-2126(02)00877-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Altschul SF, Madden TL, Schaffer AA, Zhang J, Zhang Z, Miller W, Lipman DJ. Gapped BLAST and PSI-BLAST: a new generation of protein database search programs. Nucleic Acids Res. 1997;25:3389–3402. doi: 10.1093/nar/25.17.3389. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Sen R, Nagai H, Shimamoto N. Conformational switching of Escherichia coli RNA polymerase-promoter binary complex is facilitated by elongation factor GreA and GreB. Genes Cells. 2001;6:389–401. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2443.2001.00436.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Loizos N, Darst SA. Mapping interactions of Escherichia coli GreB with NA polymerase and ternary elongation complexes. J. Biol. Chem. 1999;274:23378–23386. doi: 10.1074/jbc.274.33.23378. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Zakharova N, Bass I, Arsenieva E, Nikiforov V, Severinov K. Mutations in and monoclonal antibody binding to evolutionary hypervariable region of E. coli RNA polymerase β' subunit inhibit transcript cleavage and transcript elongation. J. Biol. Chem. 1998;273:19371–19374. doi: 10.1074/jbc.273.38.24912. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Womble DD. GCG: The Wisconsin Package of sequence analysis programs. Methods Mol Biol. 2000;132:3–22. doi: 10.1385/1-59259-192-2:3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Clamp M, Cuff J, Searle SM, Barton GJ. The Jalview Java alignment editor. Bioinformatics. 2004;20:426–427. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btg430. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Uson I, Sheldrick GM. Advances in direct methods for protein crystallography. Curr Opin Struct Biol. 1999;9:643–648. doi: 10.1016/s0959-440x(99)00020-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Terwilliger TC, Berendzen J. Automated MAD and MIR structure solution. Acta Crystallogr. D Biol. Crystallogr. 1999;D55:849–861. doi: 10.1107/S0907444999000839. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Schneider TR, Sheldrick GM. Substructure solution with SHELXD. Acta Crystallogr D Biol Crystallogr. 2002;58:1772–1779. doi: 10.1107/s0907444902011678. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Cowtan K. Dm-density modification package. ESF/CCP4 Newsletter. 1994;31:34–38. [Google Scholar]

- 48.Perrakis A, Morris R, Lamzin VS. Automated protein model building combined with iterative structure refinement. Nature Struct. Biol. 1999;6:458–463. doi: 10.1038/8263. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Adams PD, Pannu NS, Read RJ, Brunger AT. Cross-validated maximum likelihood enhances crystallographic simulated annealing refinement. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 1997;94:5018–5023. doi: 10.1073/pnas.94.10.5018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Otwinowski Z, Minor W. Processing of X-ray diffraction data collected in oscillation mode. Methods Enzymol. 1997;276:307–326. doi: 10.1016/S0076-6879(97)76066-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Laskowski RA, MacArthur MW, Moss DS, Thornton JM. PROCHECK - A program to check the stereochemical quality of protein structures. J. appl. Crystallogr. 1993;26:283–291. [Google Scholar]

- 52.Borukhov S, Polyakov A, Nikiforov V, Goldfarb A. GreA protein: A transcription elongation factor from Escherichia coli. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 1992;89:8899–8902. doi: 10.1073/pnas.89.19.8899. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Barker MM, Gaal T, Josaitis CA, Gourse RL. Mechanism of regulation of transcription intiiation by ppGpp. I. Effects of ppGpp on transcription initiaiton in vivo and in vitro. J. Mol. Biol. 2001;305:673–688. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.2000.4327. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Datsenko KA, Wanner BL. One-step inactivation of chromosomal genes in Escherichia coli K-12 using PCR products. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2000;97:6640–6645. doi: 10.1073/pnas.120163297. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Primary sequence homologs of Rnk were identified using Ballast (29). A short NTD as well as overall high sequence identity were criteria used to determine wether the homologs belong to the Rnk family.

A. Rnk crystal asymmetric unit content. The two Rnk molecules in the asymmetric unit appear in grey. Five sulfates ions per molecule are bound to surface arginines. Chloride ions are located in a hydropobic pocket at the tip of the coiled-coil.

B. FKBP domain flexible loops. Ec Rnk, Ec GreA and Taq Gfh1 are superposed on their C-terminal FKBP domain. Flexible loops are colored in red (Rnk), yellow (GreA) and cyan (Gfh1). The GreA loop appearing as a dotted line was disordered in the crystal structure (10). The flexibility in this particular loop might allow conserved residues in the FKBP domain to face the RNAP β’ coiled-coil.

A. Rnk’s FKBP domain structural superposition with FKBP12. Rnk FKBP domain (in red) has been superposed on FKBP12 (in green) on the small α-helix region revealing a deeper surface in FKBP12. This cavity accomodates peptides during the PPiase reaction and is able to bind the immunosuppressive drug FK506 (90° view).

B. Rnk’s FKBP domain structural superposition with FKBP51. Rnk FKBP domain (in red) has been superposed on the central FKBP domain of FKBP51 on the small α-helix region (in green, other domains of the protein have been omitted for clarity). This domain of FKBP51 doesn’t have any PPiase activity. The cavity leading to the core small α-helix is closed by a loop.

Rnk displaces GreA from complexes with RNAP core. 32P-labeled GreA was combined with RNAP core and run on a Superose 6 gel-filtration column. In the top trace, the radioactive peak eluting at 18 minutes contains RNAP and corresponds to the RNAP/GreA complex. The peak eluting after 22 min is free 32P-GreA. The bottom trace is a negative control, where 32P-GreA was combined with Thyroglobulin (MW 660 kDa). Traces in the middle contained, in addition to RNAP and 32P-GreA, increasing amounts of Rnk (the molar ratios of 32P-GreA and Rnk are indicated).