Abstract

Insulin receptor (IR) signaling is considered to be important in growth and development in addition to its major role in metabolic homeostasis. The metabolic role of insulin in carbohydrate and lipid metabolism is extensively studied. In contrast, the role of IR activation during embryogenesis is less understood. To address this, we examined the function of the IR during zebrafish development. Zebrafish express two isoforms of IR (insra and insrb). Both isoforms were cloned and show high homology to the human insulin receptor and can functionally substitute for the human IR in fibroblasts derived from insr gene-deleted mice. Gene expression studies reveal that these receptors are expressed at moderate levels in the central nervous system during development. Morpholino-mediated selective knockdown of each of the IR isoforms causes growth retardation and profound morphogenetic defects in the brain and eye. These results clearly demonstrate that IR signaling plays essential roles in vertebrate embryogenesis and growth.

INSULIN AND THE insulin receptor (IR) play important roles in early growth and differentiation and in later stages are essential for metabolic homeostasis (1,2). Insulin belongs to a family of structurally related hormones, the IGF family of peptides that include insulin, IGF-I, and IGF-II (1). The metabolic effects of insulin are mediated primarily via the IR. This receptor is a member of the receptor tyrosine kinase family and is expressed at the cell surface as heterodimers that are composed of two identical α/β-subunits (3). The binding of insulin to the IR initiates a cascade of events including the interaction of multiple molecules with the IR and their tyrosine phosphorylation (4). The key molecules in this pathway include the IR substrates (IRSs), which are protein substrates of the intrinsic tyrosine kinase activity of IR (5). After tyrosine phosphorylation and activation, IRSs transmit the signal to downstream cascades, such as the phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase pathway and the MAPK pathways (5).

Dysfunction of the IR and components of the downstream signaling cascade results in insulin resistance that leads to type 2 diabetes mellitus. In embryos, disruption of IR signaling causes morphogenic defects. Genetic disorders caused mainly by mutations of the IR gene result in syndromes such as leprechaunism, the Rabson-Mendenhall syndrome and others, which are classified as the type A syndrome of severe insulin resistance (6). These patients, in addition to the severe insulin resistance, demonstrate abnormalities in organ development including neurological developmental delay (7). Although clinical data demonstrate the important role for the IR in development, experiments to further understand the developmental processes that require the IR and the mechanism by which defective insulin signaling affects embryogenesis are less well defined (2). Mice lacking IR are born at term with slight growth retardation and with normal features. They develop diabetes and die from severe ketoacidosis after birth (8). Studies in Drosophila have illustrated a requirement for insulin signaling in the development of the embryonic nervous system (9,10), and in studies with mutated steppke, a downstream signaling target of the insulin receptor in Drosophila, (11), it was shown that disruption of IR signaling results in a severe growth defect. Taken together, these studies point to a regulatory role for the IR during development; however, the precise mechanisms have not been fully established.

Zebrafish are a useful vertebrate model for studying embryogenesis due to their rapid, external development. The transparent zebrafish embryo enables easy recognition of tissue and organ formation in real time (12). The availability of genetic mutants and the ease of using morpholino oligonucleotides to transiently knock down target gene expression in early embryos has made this the system of choice for evaluating the genes that are responsible for early embryogenesis. For instance, the important roles of IGF-I signaling in early development have been elucidated using zebrafish (13,14,15). Studies have shown that the zebrafish genome was duplicated during evolution and major components of zebrafish IGF-I signaling, including duplicated ligands and duplicated IGF-I receptors, have been characterized, and they are highly conserved (15,16). Morpholino-mediated knockdown of IGF-I receptors in zebrafish embryos demonstrated that the duplicated IGF-I receptors play largely functional overlapping roles in the development of the eye, inner ear, heart, and muscle (13,17,18). In contrast, there is little information on the role of IR signaling in zebrafish. Recent studies have identified two copies of the insulin gene in zebrafish (19), each with a distinct expression pattern during embryogenesis. Previous cloning efforts have suggested that there may also be two copies of the zebrafish IR (GenBank), a finding that is substantiated by our study. Despite the importance of IR signaling and the interesting implications for developmental pathways that could be influenced by multiple insulin receptor-ligand pairings in zebrafish, the role of insulin signaling in embryonic development remains to be defined.

To address this, we have taken advantage of the many benefits of zebrafish. We cloned two zebrafish IR genes (insra and insrb) and found them to be highly conserved functional homologs of the human IR. To determine the requirement for each IR during early development, we used morpholinos to specifically knock down insra or insrb alone and in combination. The insra morphants demonstrated developmental defects in the central nervous system and failure to elongate the tail and show overall growth retardation, whereas the insrb morphants were less severely affected but developed cardiac edema. Knocking down these genes together produced more profound developmental delay, the insra + insrb morphants displayed both the insra bent tail phenotype and the insrb string heart phenotype. These data may help to understand the role of insulin signaling during the early stages of vertebrate embryogenesis.

Materials and Methods

Maintenance of zebrafish and sample preparation

Wild-type (TAB14 and TAB5) zebrafish (Danio rerio) were maintained on a 14-h light, 10-h dark cycle at 28 C according to standard protocols (20). Embryos were collected from individual clutches after natural crosses between paired individuals within each line and maintained in egg water (0.6 g/liter Crystal Sea Marine Mix, Bioassay Laboratory Formula; Marine Enterprises International, Inc., Baltimore, MD; 0.1 mg/liter methylene blue) for experimental procedures. The ages of the embryos are given as either hours or days post fertilization (hpf or dpf). Embryos were fixed in 4% paraformaldehyde in PBS at for 4 h at room temperature, dehydrated in a graded series of methanol and PBS plus 0.1% Tween, and stored in 100% methanol at −20 C. All experiments were conducted in accordance with the animal care guidelines of The Mount Sinai School of Medicine.

Cloning of the zebrafish insra and insrb

Total RNA was isolated from zebrafish embryos (24 hpf) using TRIzol reagent (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA), according to the manufacturer’s recommended instructions. Total RNA was used as the template for RT. Because the short sequences for insra and insrb were cloned previously (GenBank accession nos. AF400271 and AF400272), the full coding sequences of zebrafish insra and insrb were obtained by both 5′-rapid amplification of cDNA end (5′-RACE) and 3′-RACE using SMART RACE cDNA Amplification Kit (Becton Dickinson BD Biosciences Clontech, Palo Alto, CA). After amplification, the PCR products were cloned into pGEM-T Easy vector (Promega, Madison, WI), and the resulting plasmid was subjected to DNA sequencing analysis to confirm the sequence. Sequences used for alignment other than reported here were extracted from the public databases from Ensembl Genome Browser using BLAST searches.

Materials

Human recombinant insulin was purchased from Sigma (St. Louis, MO). A polyclonal antibody to the IR β-subunit (C-20) was purchased from Santa Cruz Biotechnology (Santa Cruz, CA). A monoclonal antibody to actin was obtained from Sigma. A monoclonal antibody to phosphotyrosine (4G10) was obtained from Upstate Biotechnology (Lake Placid, NY). Anti-phospho-Akt (Ser473), anti-Akt, anti-ERK1/2, and anti-phospho-ERK antibodies were purchased from Cell Signaling Technology (Beverly, MA). RNA polymerase and ribonuclease-free deoxyribonuclease were purchased from Promega. Oligonucleotide primers for PCR were purchased from Invitrogen. All chemicals were molecular biology grade and were purchased from Sigma unless noted otherwise.

Construction and culture of mouse hepatocytes over expressing zebrafish insra

Hepatocyte cell lines derived from IR-deficient mice (IR−/− cells) were kindly provided by Dr. Domenico Accili (Columbia University, NY). IR−/− cells were maintained in α-MEM supplemented with 1 mm l-glutamine, 4 nm dexamethasone, 4% heat-inactivated fetal bovine serum, 100 U/ml penicillin, and 100 mg/ml streptomycin in a humidified atmosphere of 95% air and 5% CO2 at 37 C. The NIH-3T3 cells that overexpress the human IR at a level of about 2×106 receptors per cell were cultured in DMEM supplemented with 10% heat-inactivated fetal bovine serum, 100 U/ml penicillin, 100 mg/ml streptomycin, 300 mg/ml l-glutamine, and geneticin (Invitrogen) in a humidified atmosphere of 95% air and 5% CO2 at 37 C.

Zebrafish insra full-length cDNA was generated by long and accurate (LA)-PCR using LA Taq polymerase (Takara, Madison, WI). The forward and reverse primers were 5′-ACCACCATGCGGCTGCGGACTTTGATT-3′ and 5′-TTAAGAAGGGGTGGATCGGGGTAGAG-3′. After amplification, the PCR products were cloned into pGEM-T Easy vector (Promega), and the resulting plasmid was subjected to DNA sequencing analysis to confirm the sequence and the orientation. The fragment of zebrafish insra full-length cDNA was subcloned into the mammalian expression vector, pcDNA3.1/Hygro (Invitrogen) (pcDNA3.1/Hygro-insra).

For stable transfection, IR−/− cells were seeded to 70–80% confluence in the complete culture medium 1 d before transfection. The cells were then transfected with 8 mg pcDNA3.1-Hygro-insra or empty vector using the FuGENE 6 transfection reagent (Roche Molecular Biochemicals, Indianapolis, IN) according to the manufacture’s instruction. Two days after transfection, 0.4 g/liter hygromycin (BD Biosciences Clontech) was added to the cultures to select for clones expressing the expression vectors. Two weeks later, independent colonies were picked using the cloning disks (Scienceware). The resulting stable clones were cultured in complete culture medium with hygromycin (0.4 g/liter). We determined whether the transfected clones contained the expression vectors by PCR analysis. The forward and reverse primers were 5′-TGAGCTCAGGCCATCAAGACAG-3′ and 5′-CGTTGGATGGATCCACACGTAG-3′, respectively. Genomic DNA was isolated from each cell line using DNeasy Tissue Kit (QIAGEN, Valencia, CA).

Western blot analysis

Whole, homogenized zebrafish embryos or whole-cell lysates were prepared in lysis buffer [10 mm Tris (pH 7.4), 150 mm NaCl, 1 mm EDTA, 1% Triton-X, 100 mm sodium fluoride, 10 mm sodium orthovanadate, 10 mm sodium pyrophosphate] with protease inhibitor (Roche Applied Sciences). Lysates were centrifuged at 12,000 × g for 30 min at 4 C to remove insoluble materials. The protein concentration in the supernatants was determined with the BCA protein assay kit (Pierce, Rockford, IL). The extracted protein samples were subjected to SDS-PAGE and transferred to nitrocellulose membranes (Invitrogen). The membranes were blocked with 3% BSA in Tris-buffered saline with 0.1% Tween 20 for 1 h at room temperature. The membranes were then incubated with antibodies recognizing human IRβ (Santa Cruz; insulin Rβ C-19), phosphorylated MAPK (pMAPK) Cell Signaling no. 9101), total MAPK (Cell Signaling no. 9102), phosphorylated AKT (Cell Signaling no. 9271, phospho-Akt Ser 473), total AKT (Cell Signaling no. 9272), and β-actin (Sigma A5441) as a loading control overnight, as indicated in the figure legends. After washing with Tris-buffered saline with 0.1% Tween 20, the membranes were incubated with the appropriate horseradish peroxidase-conjugated secondary antibodies (GE Healthcare, Piscataway, NJ) for 1 h and washed again. Immunoreactivity was detected with an enhanced chemiluminescence kit (PerkinElmer Life Science Products, Boston, MA) and quantified by densitometry, using Mac Bas version 2.52 software (FujiFilm, Stamford, CT).

Whole-mount in situ hybridization

The digoxigenin-labeled RNA probe was carried out essentially as reported previously (21). A 621-bp DNA fragment was generated by RT-PCR from 24-hpf zebrafish embryos and subcloned into the pGEM-T Easy vector (Promega) using a set of primers; 5′-gagaactgcactgtaatcgaag-3′ and 5′-gaagttgcggcaggccacgcat-3′ to amplify a sequence common to both of the receptors: nucleotides 175–795 and 85–705 of the coding sequence of insra and insrb, respectively. The resulting plasmid was subjected to DNA sequencing analysis to confirm the sequence and the orientation. The plasmids were linearized by restriction enzyme digestion, followed by in vitro transcription with either T7 or SP6 RNA polymerases (Roche) to generate digoxigenin-labeled sense and antisense RNA riboprobes. Embryos for whole-mount in situ hybridization were collected and pretreated as described above. Embryos were rehydrated from methanol with PBS plus 0.1% Tween in ascending washes, and those older than 24 hpf were bleached with 3.25% hydrogen peroxide, 2.5% formamide, 0.1× standard saline citrate solution in diethylpyrocarbonate-treated water and permeabilized by proteinase K treatment. In situ hybridization was carried out essentially as described (22), with the following changes. Prehybridization was carried out for 1 h at 68 C in 50% formamide/5× standard saline citrate/0.1% Tween 20, 5 mg/ml torula RNA, and 50 μg/ml heparin, and embryos were transferred to 2 ng/μl prepared in prehybridization solution for 16 h at 68 C, followed by washes, incubation with anti-digoxigenin antibody conjugated to alkaline phosphatase (Roche Molecular Biochemicals), and stained with the substrates nitroblue tetrazolium and 5-bromo-4-chloro-3-indolyl phosphate for 6–12 h as described (22). The embryos were then refixed in 4% paraformaldehyde in PBS for 1 h and stored in 80% glycerol. Photographs were taken with a Nikon Digital Sight DS-5M color camera using a Nikon SMZ1500 stereoscope.

RNA extraction and quantitative PCR (qPCR)

Total RNA was extracted using TRIzol reagent and QIAGEN RNeasy kit (QIAGEN) and used for cDNA synthesis by RT-PCR. Two sets of primers targeting each IR were designed and assessed for accuracy by investigating the number of products identified on an agarose gel by carrying out a graded temperature dissociation and by sequencing the products. Real-time qPCR was performed using SYBR green (QIAGEN) in triplicate and quantified as comparison with levels of the ribosomal protein P0 (rppo) gene. The sequence of each primer was as follows: insra-1, 5′-CAACATGCCCCCTCACCACT-3′ and 5′-CGACACACATGTTGTTGTG-3′; insra-2, 5′-GGAGCCCCACTCGTCTAACAAA-3′ and 5′-CGCCGTTGTGAATGACGTATTC-3′; insrb-1, 5′-GACTGATTACTATCGCAAGGG-3′ and 5′-TCCAGGTATCCTCCGTCCAT-3′; and insrb-2, 5′-CCACCGCCAACCCTAAAGGA-3′ and 5′-TTGCGATAGTAATCAGTC TCGTAAAT-3′.

Morpholino injections

Morpholinos and inverse control morpholinos against insra and insrb were purchased from Gene Tools (Philomath, OR). Sequences were as follows: insra, 5′-CGCGGTAAAGCCGAAAATCGGTCCA; inverse insra, 5′-ACCTGGCTAAAAGCCGAAATGGCGC-3′; insrb, 5′-CGCGACACGTTTTGGTTTCCTTGGA-3′; and inverse insrb, 5′-AGGTTCCTTTGGTTTTGCACAGCGC-3′. The morpholinos were diluted with sterile water and injected separately and in combination, insra plus insrb, inverse insra plus inverse insrb (injection concentrations were insra and inverse insra at 0.1 mm and insrb and inverse insrb at 0.5 mm). Approximately 4 nl of each morpholino was injected into one- to two-cell-stage embryos (less than 1 hpf) using a Narishege IM-300 pressure microinjector. Underdeveloped or dead embryos were removed at 5 hpf, and then the remaining embryos were scored for mortality and phenotype at 24, 48, and 72 hpf.

Results

Cloning of two zebrafish insulin receptors

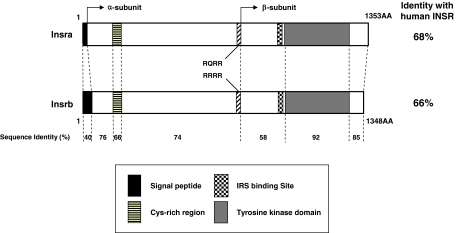

We identified two isoforms of zebrafish IR by 5′-RACE, termed insra and insrb, and analyzed their structure. The genomic structures of zebrafish insra and insrb were determined by searching the zebrafish genome database and by direct sequence analysis using PCR. Although the human IR gene has 22 exons, zebrafish insra and insrb both have 21 exons. Zebrafish insra spans 87.9 kb in chromosome 2, and zebrafish insrb spans 126.9 kb in chromosome 22 (Fig. 1). Thus, the cDNA sequence of each of the zebrafish IRs is derived from different zebrafish DNA clones, on different chromosomes, indicating that the two zebrafish IR cDNAs are derived from two distinct genes. The primary sequences of zebrafish insra (GenBank accession no. EU447177) and insrb (GenBank accession no. EU447178) precursors contain 1353 and 1348 amino acids (AA), respectively (supplemental Fig. S1, published as supplemental data on The Endocrine Society’s Journals Online web site at http://endo.endojournals.org). (GenBank also has predicted sequences insra XM-685442 and insrb XM-001922.) However, our sequences have added the 5′ and 3′ sequences and show that the exons are different from their prediction. Zebrafish Insra and Insrb are 75.3% identical to each other in primary sequence. The homologies of zebrafish Insra and Insrb with human IR are 68.3 and 65.1%, respectively. Their primary sequence identity to that of human IGF-I receptor and zebrafish IGF-1ra and IGF-1rb are significantly lower between 53 and 59%, suggesting that two zebrafish IR are grouped in the IR clade. As shown in Fig. 2, there is a tetrabasic protein cleavage site (RQRR at positions 733–736 AA for Insra and RRRR at positions 730–733 AA for Insrb) in each zebrafish IRs that cleave zebrafish IRs into α-subunits and β-subunits like human IR. Similar to mammalian IR, there are an N-terminal domain and a cysteine-rich domain that is flanked with receptor L domains in the α-subunits and a transmembrane domain with juxtamembrane motifs and a tyrosine kinase domain and a C-terminal domain in the β-subunit. Among these domains, the tyrosine kinase domain is the most highly conserved. In the tyrosine kinase domain, there is a potential ATP binding site (GXGXXG21XK; positions 1001–1028 AA for Insra and positions 996–1023 AA for Insrb) and a triple tyrosine cluster that constitutes the major autophosphorylation site for mammalian IR (YXXXYY; positions 1156–1161 AA for Insra and positions 1151–1156 AA for Insrb). Both zebrafish IRs also have a consensus IRS-binding motif (NEPY; positions 972–975 AA for insra and positions 967–970 AA for Insrb; Fig. 2 and supplemental Fig. S2).

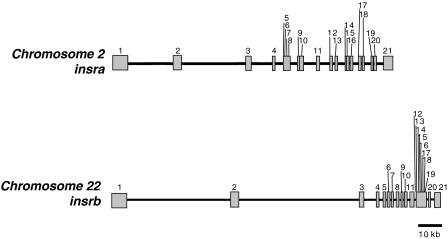

Figure 1.

The genomic structures of zebrafish insra and insrb. A schematic diagram compares the structure of zebrafish insra and insrb genes. The black lines indicate introns, and the gray boxes indicate exons.

Figure 2.

Structure of the zebrafish IR proteins Insra and Insrb. Schematic diagram of the protein domain structures is shown. The conserved IRS binding site (NPEY), ATP binding site, and autophosphorylation site are present. In addition to signal peptides, α-subunits, β-subunits, cysteine-rich region, and tetrabasic proteolytic cleavage site (RQRR for zebrafish Insra, and RRRR for zebrafish Insrb) are also presented. The percentage of sequence identity for each domain was calculated and is presented in the lower column. The percent identity between each zebrafish protein and the human INSR are indicated.

Functional characterization of zebrafish IR

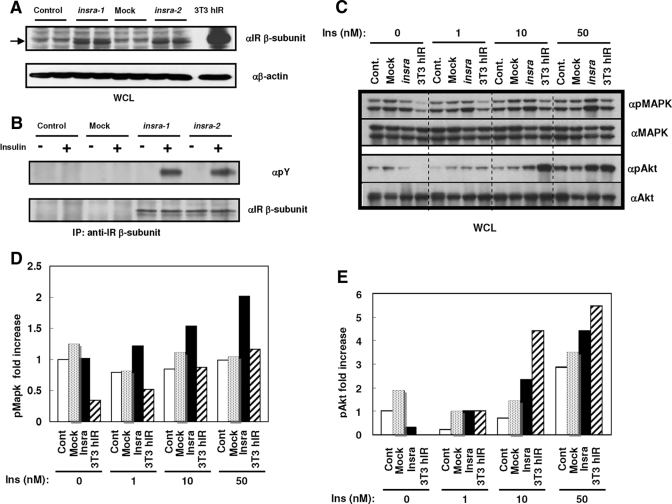

To analyze the functions of the zebrafish IRs, we established two stable clones that overexpress zebrafish insra in mouse IR-null hepatocytes (Fig. 3A). Because the two zebrafish IRs are nearly identical to human IR in the epitope for the specific antibody recognition (except for two amino acids in sequences), we were able to detect the β-subunit of zebrafish Insra using this antibody against human IR on Western blotting (Fig. 3, A and B). After insulin stimulation, the extracted proteins were immunoprecipitated with anti-mammalian IR antibody and were checked for tyrosine phosphorylation of the β-subunit. Similar to the mammalian IR, the tyrosine residues in the β-subunit of zebrafish insra were phosphorylated by insulin (Fig. 3B). In addition to the phosphorylation of the β-subunit of Insra, phosphorylation of p42/44 MAPK and Akt were increased in a dose-response manner compared with each control parental cells and mock-infected control cells after stimulation with various concentrations of insulin (Fig. 3, C–F). At high concentrations of insulin, the effect on control and mock-transfected cells may be acting via the IGF-I receptors that are increased slightly in the IR−/− hepatocytes (8). These data indicate that insra serves as the functional homolog to the human IR, and it is able to activate the same downstream signaling pathways.

Figure 3.

The zebrafish insra restores insulin signaling in mouse IR-deficient hepatocytes. A, IR−/− hepatocytes were established from IR-null mice and were stably transfected with an empty vector or one in which zebrafish insra expression is driven by the cytomegalovirus promoter. NIH-3T3 cells that overexpress human IR was loaded as a blotting control. Whole-cell lysates (WCL) were blotted with an antibody against the IR β-subunit (anti-IR) and then stripped and reprobed with an antibody against β-actin to control for equal loading (lower panel). B, IR−/− hepatocytes were either untransfected (control) or transfected with an empty vector (mock) or with the insra-containing plasmid. Each cell line was subjected to serum starvation for 18 h and then incubated in the presence or absence of 10 nm human insulin. The resulting cell lysates were immunoprecipitated with anti-IR β-subunit and blotted with anti-phosphotyrosine (anti-pY; upper panel), stripped, and reblotted with anti-IR. C, Phosphorylation and total MAPK levels (upper panels) and phosphorylation and total expression of Akt levels (lower panels). D and E, Phosphorylation of MAPK and Akt was evaluated by densitometric analysis compared with total MAPK or Akt, respectively. All experiments were repeated at least twice.

insra and insrb are expressed in the developing zebrafish embryo

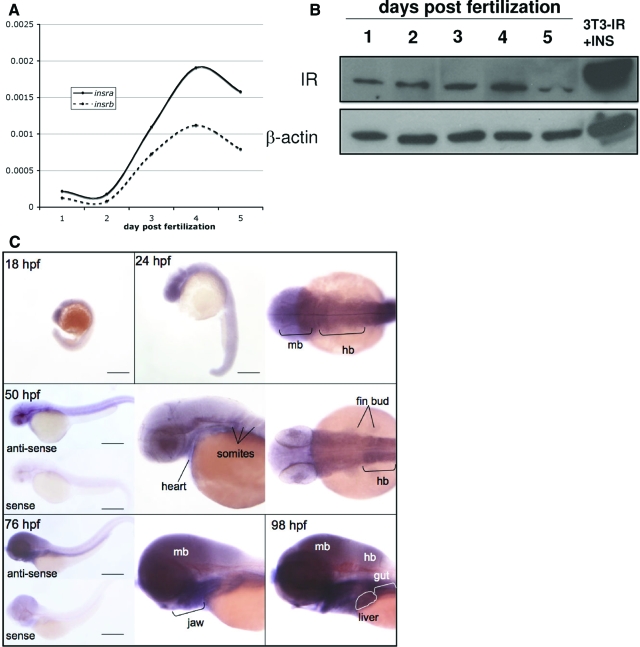

To evaluate IR RNA and protein expression during zebrafish development, real-time PCR, Western blotting, and whole-mount in situ hybridization were used. Many zebrafish genes are duplicated; however, in some cases, only one of the isoforms is expressed during development. If both insra and insrb play a role in embryogenesis, then we predict that both will be expressed in the developing embryo. The mRNAs were analyzed using two different sets of primers for each IR isoform. The products were run on a gel (supplemental Fig. S2) and subjected to sequence analysis, which demonstrated that the amplified product was as expected (not shown). Those primers yielding a single product that corresponded to the correct IR (i.e. primer pairs insra-2 and insrb-1; supplemental Fig. S2) were used in qPCR to detect the amount of each transcript compared with rppo as a reference (Fig. 4A). Interestingly, the expression levels of both isoforms of IR were remarkably high in unfertilized eggs (not shown), indicating that both are maternally supplied. As development proceeds, we found that the expression level trend for both insra and insrb was similar, increasing from 2–4 dpf and peaking at 4 dpf (Fig. 4A).

Figure 4.

IR expression during zebrafish development. A, insra and insrb RNA expression was assessed in embryos on 1–5 dpf by qPCR using insra-1 and insrb-1 primers, and the change in cycle threshold values relative to rppo message levels in each sample are plotted. B, IR protein levels in embryos from 1–5 dpf were analyzed by Western blotting using the human IR-β and β-actin antibodies. Extracts from NIH-3T3 cells overexpressing human IR and treated with insulin were loaded as a control. C, IR expression pattern was analyzed by in situ hybridization in embryos at 18–24 somites (18 hpf), prim-5 (24 hpf), long pec (50 hpf), and protruding-mouth (76 hpf) stages. The antisense probe detects both insra and insrb transcripts. The sense probe did not show any hybridization signal. These experiments were repeated with similar results. hb, Hindbrain; mb, midbrain.

Western blotting samples of embryos collected from two separate clutches on 1–5 dpf using the human IR antibody revealed a strongly cross-reacting band of the appropriate molecular weight appearing in 1-dpf samples, which we believe to correspond to the sum of both IRs (Fig. 4B). The maximum level of IR protein per microgram protein was detected on 4 dpf and decreased on 5 dpf. Akt total protein was first detected at 2 dpf, and levels did not change significantly on 3–5 dpf. Similarly, Akt phosphorylation remained constant from 2 dpf onward (data not shown). These data suggest that IR signaling through the Akt pathway may begin by the second day of development but does not rule out that signaling through other pathways may occur earlier.

To determine the spatial and temporal expression pattern of IRs during development, a probe that hybridizes to both insra and insrb was used to analyze expression in during early embryogenesis (18 somites through 74 hpf). Figure 4C illustrates the level, ubiquitous expression observed in during the somatogenesis and early patterning stages (18 and 24 somites, 24 and 36 hpf). Increased expression in the cerebellum, tectum, and spinal cord of embryos after 36 hpf was observed and low expression was also detected in the trunk somites and eyes. Staining was not observed in the tail or in any specific organs.

IR knockdown blocks insulin signaling

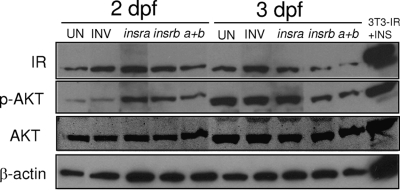

To determine whether either IR is required for vertebrate embryogenesis and to compare whether either plays a role in different or overlapping processes, we used morpholino oligos against insra and insrb to transiently knock down the expression of each individually and in combination and assessed the level of IR and Akt protein as well as the phosphorylation levels of Akt. Because morpholino oligonucleotides block the translation of the target RNA, but do not affect the levels of transcript, we used Western blotting to assess the efficacy of the morpholino injection (Fig. 5). Control morpholinos encoded the sense (i.e. the inverse) of each IR morpholino. IR protein levels were most significantly suppressed in the embryos that were injected with morpholinos against both insra and insrb compared with embryos injected with inverse controls. The expression level of IR in the embryos that were injected with the inverse insra and inverse insrb morpholinos (INV) was comparable to the uninjected embryos (Fig. 5A). In proportion to the expression level of IR, the phosphorylation and protein levels of Akt were suppressed in embryos that were injected either with insra or insrb as well as the combination of insra and insrb (a + b), whereas the levels remained only slightly decreased in the inverse morpholino-injected embryos.

Figure 5.

IR morphants have decreased levels of IR expression and phosphorylation of Akt. Control, uninjected (UN) embryos and those injected with morpholinos targeting insra or insrb either alone or in combination and those injected with the combined inverse insra plus inverse insrb (INV) were collected at 2 and 3 dpf. Blots were incubated with IR and phospho-Akt antibodies, and parallel samples were blotted for total Akt and β-actin. The data are representative of at least two experiments.

IR knockdown disrupts early embryogenesis

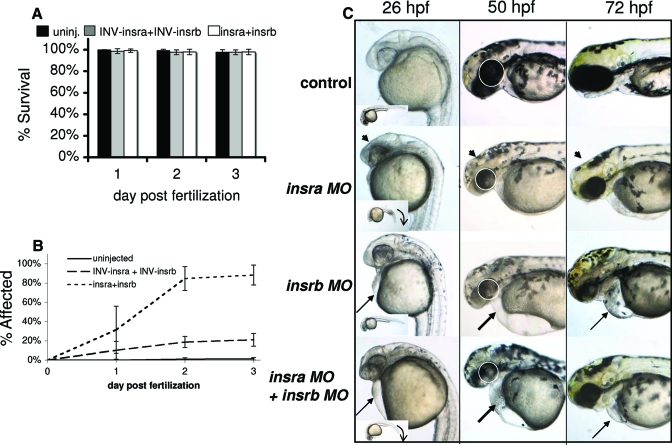

To address the role of IR on embryogenesis, we studied the effect of IR knockdown using morpholinos against each IR isoform. Each morpholino was titrated to obtain the maximal sublethal concentration: 0.1 mm for insra and 0.5 mm for insrb. When these were injected individually, a phenotype appeared in less than 30% of the embryos (not shown). When injected in combination, the morpholinos were not lethal (Fig. 6A); however, they induced a phenotype in nearly all of the injected embryos by 3 dpf (Fig. 6, B and C). These data demonstrate that the effect of the morpholino was specific and was not generally toxic and that these two receptors may serve some overlapping functions.

Figure 6.

insra and insrb play different roles in early zebrafish development. Embryos injected with about 4 nl 0.1 mm insra plus 0.5 mm insrb morpholinos were compared with uninjected controls and those injected with the same concentrations of inverse (INV) morpholinos and scored for mortality on 1–3 dpf (A) or for phenotype (B). Values represent the average of at least three experiments in which at least 50 embryos were scored for each treatment on each day. Error bars indicate the sem. C, Embryos displaying characteristic phenotypes observed in at least five clutches were imaged at 26, 50, and 72 hpf. Arrowhead points to the midbrain, which is underdeveloped in the insra morphants. The ventral tail curve in insra morphants is illustrated by the arrow in the inset of the 26-hpf embryos. The arrow illustrates pericardial edema. The eye is circled in the 50-hpf images to illustrate the reduction in eye size in the morphants. Magnification, ×50. The data are representative of two similar experiments.

The majority of the embryos injected with insra or insrb morpholinos individually were not affected. Those embryos that were affected, however, developed phenotypes that indicate that each IR plays a specific and essential role during embryogenesis. Figure 6C shows representative images of the morphants generated from knocking down each receptor alone and in combination on 1–3 dpf. The embryos injected with each morpholino individually showed specific and mild phenotypes on the first day of development, and these phenotypes became increasingly severe as development progressed. On 1 dpf, knockdown of insra caused general growth retardation, a downward curvature to the tail (see inset on 26-hpf embryo) and underdevelopment of the midbrain (arrowhead) and eye. In contrast, knockdown of insrb resulted in only mild pericardial edema in some embryos on 1 dpf (arrow in Fig. 6C). insra morphants at 2 and 3 dpf illustrate more severe reduction of the eye and midbrain, which distorts the midbrain-hindbrain boundary. The forebrain in insra morphants is also slightly reduced at 2 dpf, and this becomes more severe on 3 dpf. In contrast, although the insrb morphants also have small eyes and slightly reduced mid- and forebrain structures, the two most prominent phenotypes are the pericardial edema (Fig. 6C, arrow) and the small and dysmorphic jaw.

Interestingly, virtually all embryos injected with both insra and insrb morpholinos (combination morphants) show a phenotype (Fig. 6B) that has features of the embryos injected with each morpholino individually. These combination morphants develop a ventrally curved tail (a feature of insra morphants) as well as pericardial edema (a feature of insrb morphants) by 26 hpf. In addition, they demonstrate severely reduced eyes, small and abnormal jaws, and reduced forebrain structures on 2–3 dpf. These data suggest that the zebrafish IRs play distinct roles during development but that when one receptor is knocked down, the other can substitute.

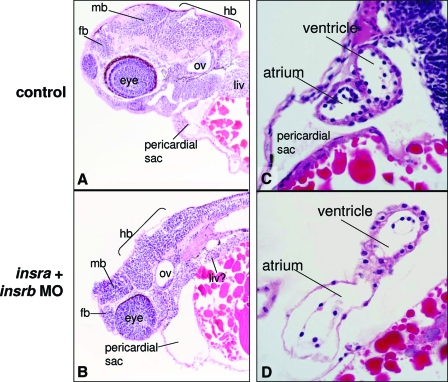

To more carefully examine the effects of insra knockdown on development of the brain and heart, we analyzed the histology of the insra plus insrb MO embryos at 74 hpf. Figure 7, A and B, shows a sagittal hematoxylin- and eosin-stained section through the left otic vesicle and eye of control and morphant embryos. The well developed fore-, mid-, and hindbrain are evident in control embryos; however, in morphants, although these regions of the brain can be identified, they are underdeveloped and poorly differentiated. For instance, the cerebellum is well formed in the controls but cannot be easily identified in morphants. In addition, the retinal layers cannot be easily identified in morphants. The brachial arches, liver, gut, and kidney are poorly differentiated and reduced in size. The pericardial sac is grossly dilated in morphants, as was evident by the pericardial edema observed in live embryos (Fig. 6C). The heart in 3-dpf morphants is markedly dilated, and the chambers are extended (Fig. 7, C and D), similar to that observed in the heartstrings mutant (23). Taken together, these data indicate the requirement for the IR in embryonic growth and cell differentiation, most significantly in the brain and heart.

Figure 7.

The IR is required for proper neurogenesis and organogenesis. Sections through the head (A and B) and heart (C and D) of control (uninjected) and insra plus insrb morphant embryos at 74 hpf were stained with hematoxylin and eosin. fb, Forebrain; hb, hindbrain; liv, liver; mb, midbrain; ov, otic vesicle. The data are representative of two similar experiments.

Discussion

Insulin signaling is one of the important pathways for biological homeostasis and is highly conserved (1,24). We have identified and characterized two isoforms of the IR in zebrafish, investigated their genetic structure, and demonstrated their unique roles in embryogenesis. Both Insra and Insrb have homology to human IR with amino acid similarity of 68.3 and 65.4%, respectively. Furthermore, each isoform encodes an α-subunit and β-subunit, similar to the human IR (3,25), suggesting that they are highly conserved evolutionarily. We demonstrate that the kinetics of the insulin signaling via insra is similar to that of mammalian insulin signaling cascades, suggesting that the signaling pathways downstream of the zebrafish IR are the same as found in other vertebrates (5). Indeed, knockdown of the IRs resulted in altered signaling via Akt, a downstream signaling cascade involved in mammalian systems and with orthologs in both Drosophila and Caenorhabditis elegans (26,27). Moreover, our experiments demonstrate that the zebrafish insra is a functional homolog of the human IR, indicating that our findings in zebrafish may be directly relevant to mammals.

It is interesting that the two IRs appear to play different, albeit somewhat overlapping, roles during early development. Whereas insra is critical for brain development and for general growth, insrb is essential for proper heart development. Our data show a ubiquitous expression of these receptors, and that expression is higher in the central nervous system and eyes. Although additional experiments using probes specific for each receptor are required to determine whether these two IRs have distinct expression patterns, the expression pattern corresponds to the phenotype resulting from their knockdown; i.e. the high expression in the central nervous system correlates with the significant defects in the brain and eye that form as a result of IR knockdown.

It is striking that the phenotype of the IR morphants precedes the expression of insulin by the pancreatic β-cells. Recently, two isoforms of insulin have been found in zebrafish (19), and one of them (insb) is expressed in early embryos in the central nervous system, whereas insa is expressed after 24 hpf in the pancreatic islets. It is interesting to speculate that the requirement for the IR 24- to 48-hpf embryos could be due to the signaling induced by the early expressed insb ligand. Consistent with this hypothesis, our preliminary findings indicate that there is widespread cell death in the CNS of the insra and the combination morphants at the 20- to 25-somite stage, before the first morphological phenotype observed in the morphants. Together, these data suggest that zebrafish IR genes are required for cell survival during neurogenesis.

According to the previous reports of genetic disorders of IR in humans, it has been indicated that IR signaling pathways play important roles in embryogenesis, morphogenesis, and growth as well as in glucose metabolism (28). Our data support this. We show that the IR is essential for the proper development of the brain, heart, and eye and for embryonic growth. The segments of the brain, although present, are undifferentiated and grossly reduced in size. This is similar to the phenotype of the eye in the insra plus insrb morphants. This suggests that the IR is not required for brain or eye patterning but instead for subsequent neural differentiation and expansion. Interestingly, those phenotypes are similar but somewhat different from the patients with IR mutations or gene-deletion studies of the IR in mice (6,29,30), where the defects are commonly related to growth retardation and some organ effects. Kadowaki and co-workers (31,32) demonstrated IR mutations in patients with leprechaunism that present with growth retardation and mental defects. Laustsen and co-workers (33) created the heart-specific IR and IGF-I recepter knockout mouse and found that those mice develop dilated cardiomyopathy at early stage and die from heart failure, and the heart-specific IR knockout mouse has cardiac dysfunction at 6 months of age. Our findings that knocking down insrb in zebrafish result in pericardial edema, which is frequently due to failed vasculogenesis resulting in restricted outflow or to dysmorphic cardiac morphogenesis and weak contractility. This is also evident by histological analysis, which shows a grossly dilated pericardial sac and a dilated and underdeveloped heart. Together, these data suggest that IR signaling is required for vertebrate cardiogenesis, and analysis of the early stages of cardiac development in the insrb morphants as well as the expression of specific cardiac markers will elucidate the mechanism by which this occurs.

Although there are some similarities between the zebrafish morphants described here and mammals with reduced IR signaling, the most striking difference is the neurogenic defects observed in the zebrafish morphants. These differences may be attributed to differences in experimental procedure. Morpholino oligonucleotides induce a significant, but not complete, knockdown of target gene translation, and this is most effective in early embryos, because the injection can be carried out only on the syncytial one- to eight-cell embryo. The intracellular concentration decreases with each cell division, and eventually the zygotic transcript overwhelms the morpholino, allowing the embryo to proceed through later IR-dependent developmental events. This is in contrast to mice or humans bearing genetic mutation in their IR, which is sustained throughout development. In addition, humans with IR mutations typically have point mutations, which presumably causes partial suppression of this signaling (31), as opposed to the knockdown of the whole message that is elicited by a morpholino or the complete abrogation of the gene occurring in mouse mutants (8).

Signaling through the IGF-I receptor is also considered to be important in developmental processes (14,17) and recent studies have described the differential role of IGF-I receptor isoforms a and b in zebrafish precisely (17). Those two isoforms have overlapping roles in eye, ear, and heart development, whereas igfra is critical for cell survival (17). IGF signaling regulates zebrafish embryonic growth and development by promoting cell survival and cell cycle progression (17), and igfrb regulates motoneuron and contractility of muscle and plays an important role in germ cell migration (13).

In a similar manner, it will be important to dissect the patterning and morphogenesis events that are regulated by IR signaling in each of the structures affected in the morphants. In addition to analysis of the requirements for IR signaling in early zebrafish embryos, it will be of interest to use this system to address developmental defects that occur as a result of changes in glucose utilization. Our initial findings demonstrate that embryos injected with morpholino concentrations lower than used in this study survive and appear relatively normal until 5 dpf; however, they develop hepatic steatosis, a sign of disrupted IR signaling. Thus, this provides a useful and novel system to understand the important role that the IR plays in morphogenesis as well as in energy metabolism.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank Ken Inagaki, M.D., for his expert help with the experiments and Milton English, Paul Liu, Brant Weinstein, and Makoto Kamei of the National Institutes of Health (Bethesda, MD) for their help.

Footnotes

GenBank accession numbers for our nucleotide sequences are EU447177 for insra EU447178 for insrb.

Both insra and insrb predicted structures in GenBank and Ensembl database missed the first exon. The second exon and the last exon are incorrect. They did not include the start and stop codons. In addition, for insra, the Ensembl predicted exon 10 is incorrect; it should be an intron. For insrb, the predicted exon 12 is incorrect; it includes the 12-bp intron sequence at the end of exon 12.

Disclosure Statement: Y.T., C.M., C.D., Y.W., C.G., S.Y., and K.C.S. have nothing to declare. D.L. consults for and has received speaker fees for Merck, Takeda, Novo-Nordisk, Astra-Zeneca, BMS, and Roche.

First Published Online August 7, 2008

Abbreviations: AA, Amino acids; dpf days post fertilization; hpf, hours post fertilization; IR, insulin receptor; IRS IR substrate; qPCR, quantitative PCR; RACE, rapid amplification of cDNA end.

References

- Le Roith D, Zick Y 2001 Recent advances in our understanding of insulin action and insulin resistance. Diabetes Care 24:588–597 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Louvi A, Accili D, Efstratiadis A 1997 Growth-promoting interaction of IGF-II with the insulin receptor during mouse embryonic development. Dev Biol 189:33–48 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- De Meyts P, Whittaker J 2002 Structural biology of insulin and IGF1 receptors: implications for drug design. Nat Rev Drug Discov 1:769–783 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kahn CR, White MF 1988 The insulin receptor and the molecular mechanism of insulin action. J Clin Invest 82:1151–1156 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Taniguchi CM, Emanuelli B, Kahn CR 2006 Critical nodes in signalling pathways: insights into insulin action. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol 7:85–96 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Taylor SI, Arioglu E 1999 Genetically defined forms of diabetes in children. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 84:4390–4396 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wertheimer E, Lu SP, Backeljauw PF, Davenport ML, Taylor SI 1993 Homozygous deletion of the human insulin receptor gene results in leprechaunism. Nat Genet 5:71–73 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Accili D, Drago J, Lee EJ, Johnson MD, Cool MH, Salvatore P, Asico LD, Jose PA, Taylor SI, Westphal H 1996 Early neonatal death in mice homozygous for a null allele of the insulin receptor gene. Nat Genet 12:106–109 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pimentel B, de la Rosa EJ, de Pablo F 1996 Insulin acts as an embryonic growth factor for Drosophila neural cells. Biochem Biophys Res Commun 226:855–861 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- LaFever L, Drummond-Barbosa D 2005 Direct control of germline stem cell division and cyst growth by neural insulin in Drosophila. Science 309:1071–1073 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fuss B, Becker T, Zinke I, Hoch M 2006 The cytohesin Steppke is essential for insulin signalling in Drosophila. Nature 444:945–948 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stuckenholz C, Ulanch PE, Bahary N 2005 From guts to brains: using zebrafish genetics to understand the innards of organogenesis. Curr Top Dev Biol 65:47–82 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schlueter PJ, Sang X, Duan C, Wood AW 2007 Insulin-like growth factor receptor 1b is required for zebrafish primordial germ cell migration and survival. Dev Biol 305:377–387 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eivers E, McCarthy K, Glynn C, Nolan CM, Byrnes L 2004 Insulin-like growth factor (IGF) signalling is required for early dorso-anterior development of the zebrafish embryo. Int J Dev Biol 48:1131–1140 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maures T, Chan SJ, Xu B, Sun H, Ding J, Duan C 2002 Structural, biochemical, and expression analysis of two distinct insulin-like growth factor I receptors and their ligands in zebrafish. Endocrinology 143:1858–1871 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ayaso E, Nolan CM, Byrnes L 2002 Zebrafish insulin-like growth factor-I receptor: molecular cloning and developmental expression. Mol Cell Endocrinol 191:137–148 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schlueter PJ, Peng G, Westerfield M, Duan C 2007 Insulin-like growth factor signaling regulates zebrafish embryonic growth and development by promoting cell survival and cell cycle progression. Cell Death Differ 14:1095–1105 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schlueter PJ, Royer T, Farah MH, Laser B, Chan SJ, Steiner DF, Duan C 2006 Gene duplication and functional divergence of the zebrafish insulin-like growth factor 1 receptors. FASEB J 20:1230–1232 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Papasani MR, Robison BD, Hardy RW, Hill RA 2006 Early developmental expression of two insulins in zebrafish (Danio rerio). Physiol Genomics 27:79–85 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Westerfield M 2000 The zebrafish book. A guide for laboratory use of zebrafish. 4th ed. Eugene, OR: University of Oregon Press [Google Scholar]

- Lo J, Lee S, Xu M, Liu F, Ruan H, Eun A, He Y, Ma W, Wang W, Wen Z, Peng J 2003 15000 unique zebrafish EST clusters and their future use in microarray for profiling gene expression patterns during embryogenesis. Genome Res 13:455–466 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sagerstrom CG, Grinbalt Y, Sive H 1996 Anteroposterior patterning in the zebrafish, Danio rerio: an explant assay reveals inductive and suppressive cell interactions. Development 122:1873–1883 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Garrity DM CS, Fishman MC 2002 The heartstrings mutation in zebrafish causes heart/fin Tbx5 deficiency syndrome. Development 129:4635–4645 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- White MF 2003 Insulin signaling in health and disease. Science 302:1710–1711 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ullrich A, Bell JR, Chen EY, Herrera R, Petruzzelli LM, Dull TJ, Gray A, Coussens L, Liao YC, Tsubokawa M, Mason A, Seeburg PH, Grunfeld C, Rosen OM, Ramachandran J 1985 Human insulin receptor and its relationship to the tyrosine kinase family of oncogenes. Nature 313:756–761 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Garofalo RS 2002 Genetic analysis of insulin signaling in Drosophila. Trends Endocrinol Metab 13:156–162 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Iser WB, Gami MS, Wolkow CA 2007 Insulin signaling in Caenorhabditis elegans regulates both endocrine-like and cell-autonomous outputs. Dev Biol 303:434–447 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Taylor SI 1992 Lilly Lecture: molecular mechanisms of insulin resistance. Lessons from patients with mutations in the insulin-receptor gene. Diabetes 41:1473–1490 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Longo N, Singh R, Griffin LD, Langley SD, Parks JS, Elsas LJ 1994 Impaired growth in Rabson-Mendenhall syndrome: lack of effect of growth hormone and insulin-like growth factor-I. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 79:799–805 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kadowaki T, Bevins CL, Cama A, Ojamaa K, Marcus-Samuels B, Kadowaki H, Beitz L, McKeon C, Taylor SI 1988 Two mutant alleles of the insulin receptor gene in a patient with extreme insulin resistance. Science 240:787–790 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kadowaki H, Takahashi Y, Ando A, Momomura K, Kaburagi Y, Quin JD, MacCuish AC, Koda N, Fukushima Y, Taylor SI, Akanuma Y, Yazaki Y, Kadowaki T 1997 Four mutant alleles of the insulin receptor gene associated with genetic syndromes of extreme insulin resistance. Biochem Biophys Res Commun 237:516–520 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Takahashi Y, Kadowaki H, Momomura K, Fukushima Y, Orban T, Okai T, Taketani Y, Akanuma Y, Yazaki Y, Kadowaki T 1997 A homozygous kinase-defective mutation in the insulin receptor gene in a patient with leprechaunism. Diabetologia 40:412–420 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Laustsen PG, Russell SJ, Cui L, Entingh-Pearsall A, Holzenberger M, Liao R, Kahn CR 2007 Essential role of insulin and insulin-like growth factor 1 receptor signaling in cardiac development and function. Mol Cell Biol 27:1649–1664 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.