Abstract

SHARP1, a basic helix–loop–helix transcription factor, is expressed in many cell types; however, the mechanisms by which it regulates cellular differentiation remain largely unknown. Here, we show that SHARP1 negatively regulates adipogenesis. Although expression of the early marker CCAAT/enhancer binding protein β (C/EBPβ) is not altered, its crucial downstream targets C/EBPα and peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor γ (PPARγ) are downregulated by SHARP1. Protein interaction studies confirm that SHARP1 interacts with and inhibits the transcriptional activity of both C/EBPβ and C/EBPα, and enhances the association of C/EBPβ with histone deacetylase 1 (HDAC1). Consistently, in SHARP1-expressing cells, HDAC1 and the histone methyltransferase G9a are retained at the C/EBP regulatory sites on the C/EBPα and PPARγ2 promoters during differentiation, resulting in inhibition of their expression. Interestingly, treatment with troglitazone results in displacement of HDAC1 and G9a, and rescues the differentiation defect of SHARP1-overexpressing cells. Our data indicate that SHARP1 inhibits adipogenesis through the regulation of C/EBP activity, which is essential for PPARγ-ligand-dependent displacement of co-repressors from adipogenic promoters.

Keywords: adipogenesis, G9a, HDAC1, troglitazone, acetylation

Introduction

Transcriptional regulation of adipogenic differentiation is a tightly controlled process that is regulated by members of two protein families: the CCAAT/enhancer binding proteins (C/EBPs) and the peroxisome proliferator-activated receptors (PPARs; Rosen et al, 2000; Farmer, 2006; Rosen & MacDougald, 2006). Following exposure of preadipocytes to differentiation-inducing hormones, C/EBPβ and C/EBPδ are rapidly and transiently expressed, and transcriptionally regulate the expression of C/EBPα and PPARγ, which, in turn, regulate the expression of many genes required for terminal differentiation (Wu et al, 1996, 1999). Several effectors modulate the expression or activity of C/EBPs and PPARγ and thereby affect adipogenic differentiation. This includes transcription factors, cell-cycle regulators and signalling pathways such as Wnt, Notch, Hypoxia and Hedgehog. In addition, recent evidence indicates that histone modifiers result in epigenetic alterations that allows the formation of transcriptionally competent chromatin during differentiation (Farmer, 2006; Rosen & MacDougald, 2006).

SHARP1/DEC2 (Rossner et al, 1997; Fujimoto et al, 2001) is a member of the transcriptional repressor subfamily of basic helix–loop–helix (bHLH) transcription factors (Sun et al, 2007a) that is expressed in various embryonic and adult tissues (Azmi & Taneja, 2002; Azmi et al, 2003). We have shown previously that overexpression of SHARP1 results in inhibition of myogenic differentiation (Azmi et al, 2004). Consistent with these findings, SHARP1 was found to be overexpressed in inclusion body myositis mesangioblasts that fail to differentiate into skeletal muscle (Morosetti et al, 2006). However, little is known about the function of SHARP1 in differentiation of other cell types and the mechanisms underlying its function as a transcriptional repressor remain to be fully defined.

Here, we show by using both gain-of-function and loss-of-function approaches that SHARP1 inhibits adipogenesis. SHARP1 interacts with C/EBPβ and C/EBPα and inhibits their activity. The interaction with C/EBPβ is essential for SHARP1-mediated inhibition of differentiation. In the presence of SHARP1, the association of C/EBPβ with histone deacetylase 1 (HDAC1) is enhanced and probably results in the retention of HDAC1 and G9a on the C/EBPα and PPARγ2 promoters during differentiation. Addition of the PPARγ ligand troglitazone rescues the differentiation block imposed by overexpressing SHARP1, which is concomitant with the removal of HDAC1 and G9a. Our data indicate that SHARP1 inhibits adipogenesis by targeting C/EBPβ activity essential for the displacement of co-repressors from the promoters of its transcriptional targets C/EBPα and PPARγ2 during differentiation.

Results And Discussion

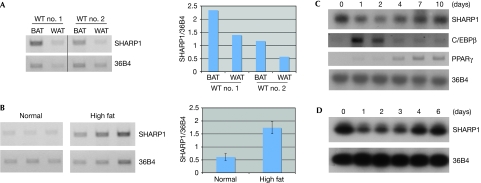

Expression of SHARP1 is modulated during adipogenesis

We have shown previously that SHARP1 is expressed in several embryonic and adult tissues (Azmi & Taneja, 2002; Azmi et al, 2003). We characterized its pattern of expression in adipose tissue; SHARP1 RNA was detected in both white and brown adipose tissue of adult mice (Fig 1A), and its expression was elevated in white adipose tissue of mice fed with a high-fat diet (Fig 1B). SHARP1 RNA levels were transiently downregulated during differentiation in 3T3L1 and 10T1/2 cells, coincident with an increase in C/EBPβ, and upregulated again during terminal differentiation (Fig 1C,D).

Figure 1.

The expression of SHARP1 in adipose tissue and differentiating adipocytes. (A) SHARP1 RNA levels were analysed in BAT and WAT from 2-month-old WT mice (n=2) and (B) in WAT of mice fed normal (n=3) or a high-fat diet (n=3). RNA amounts were normalized with transcripts to the ribosomal phosphoprotein 36B4. Band intensities were quantified and the ratio of SHARP1/36B4 is shown on the right. Error bars indicate mean±s.e. (C,D) SHARP1 RNA levels were examined in (C) differentiating 3T3L1 cells and (D) 10T1/2 cells, using 36B4 as a control. BAT, brown adipose tissue; C/enhancer, CCAAT/enhancer binding protein; PPAR, peroxisome proliferator activated receptor; WAT, white adipose tissue; WT, wild type.

SHARP1 inhibits adipogenic differentiation

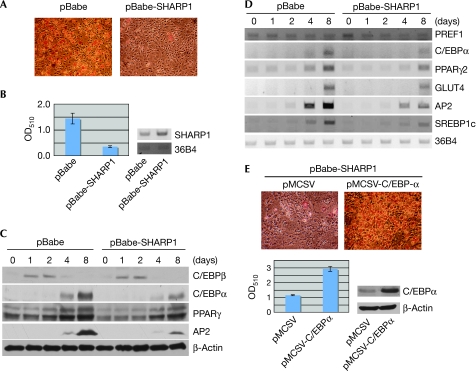

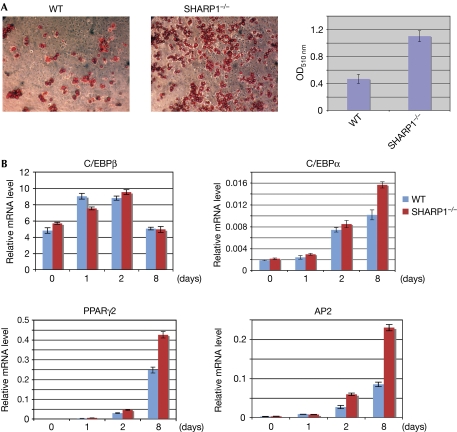

To determine whether SHARP1 overexpression in adipocyte precursor cells modulates differentiation, 3T3L1 cells were infected with retrovirus expressing SHARP1 (pBabe-SHARP1) or with the vector alone (pBabe) as a control. Cells overexpressing SHARP1 showed a decrease in the number of differentiated adipocytes compared with vector-infected cells as seen by Oil-Red-O (ORO) staining (Fig 2A,B). To investigate the mechanisms underlying this inhibitory effect, we examined the expression of early and late adipogenic markers during differentiation by using Western blot analysis. The expression of C/EBPβ was not altered; however, its downstream transcriptional targets C/EBPα and PPARγ2 (Christy et al, 1991; Clarke et al, 1997) were downregulated in pBabe-SHARP1 cells (Fig 2C), suggesting that SHARP1 inhibits adipogenesis through C/EBPβ. In addition, adipocyte fatty-acid binding protein 2 (AP2), a target of both PPARγ and C/EBPα, was also reduced in SHARP1-expressing cells. To examine whether inhibition of late adipogenic markers was caused by altered transcriptional regulation, we analysed C/EBPα, PPARγ2 and AP2 messenger RNA (mRNA) levels. Transcripts of these late differentiation markers, as well as glucose transporter 4 (GLUT4) and sterol regulatory element binding protein 1c (SREBP1c), were lower in SHARP1-overexpressing cells. By contrast, pre-adipocyte factor 1 (PREF1), which is downregulated during differentiation, was regulated normally (Fig 2D). As C/EBPα has a crucial function in adipogenesis and is a transcriptional target of C/EBPβ, we examined whether re-introducing C/EBPα could rescue SHARP1-mediated block of adipogenesis. Re-expression of C/EBPα rescued the inhibition of differentiation in SHARP1-overexpressing cells as seen by ORO staining (Fig 2E), indicating that repression of C/EBPα is important for SHARP1-mediated inhibition of adipogenesis. Consistent with these studies, SHARP1−/− mouse embryonic fibroblast (MEF) cells showed increased differentiation relative to wild-type cells, confirming that endogenous SHARP1 regulates adipogenesis (Fig 3A). Furthermore, the expression of C/EBPβ was unaltered, whereas CEBPα, PPARγ2 and AP2 levels were higher in mutant MEFs compared with wild-type controls (Fig 3B).

Figure 2.

Overexpression of SHARP1 inhibits adipogenic differentiation. (A) 3T3L1 cells were infected with SHARP1 (pBabe-SHARP1) or vector (pBabe) alone, differentiated and stained with ORO. (B) Extracted ORO was measured at OD510 nm. The expression of SHARP1 was determined by RT–PCR (right panel); 36B4 transcripts were used as an internal control. (C) pBabe and pBabe-SHARP1 cells were differentiated and analysed by Western blot using antibodies against C/EBPβ, C/EBPα, PPARγ2 and AP2; β-Actin was used as a loading control. (D) PREF1, C/EBPα, PPARγ2, GLUT4, AP2 and SREBP1c messenger RNA levels in pBabe and pBabe-SHARP1 cells were detected during differentiation by RT–PCR; 36B4 transcripts were used as an internal control. (E) SHARP1-expressing cells were infected with empty vector (pMCSV) or with C/EBPα. At 10 days after differentiation, cells were stained with ORO. Extracted dye was measured at OD510 nm (lower panel). C/EBPα expression levels were analysed by Western blot; β-Actin was used as a loading control. C/EBP, CCAAT/enhancer binding protein; OD, optical density; ORO, Oil-Red-O; PPAR, peroxisome proliferator activated receptor; RT–PCR, reverse transcription–PCR.

Figure 3.

Enhanced adipogenesis in SHARP1−/− mouse embryonic fibroblasts. (A) WT and SHARP1−/− MEFs were differentiated and stained with ORO; extracted ORO was measured at OD510 nm. (B) C/EBPβ, C/EBPα, PPARγ2 and AP2 levels in WT and SHARP1−/− cells were detected during differentiation by Q-PCR; GAPDH transcripts were used as an internal control. The data are representative of two independent WT and SHARP1−/− cells. Error bars indicate mean±s.d. C/EBP, CCAAT/enhancer binding protein; GAPDH, glyceraldehyde 3-phosphate dehydrogenase; MEF, mouse embryonic fibroblast; OD, optical density; ORO, Oil-Red-O; PPAR, peroxisome proliferator activated receptor; Q-PCR, quantitative PCR; WT, wild type.

SHARP1 inhibits the activity of C/EBP

To examine the mechanisms underlying reduced expression of C/EBPα and PPARγ2, we analysed whether SHARP1 modulates the localization of C/EBPβ, DNA binding or transcriptional activity. No alteration in the localization of C/EBPβ or DNA binding was evident from gel-shift assays or by chromatin immunoprecipitation (ChIP) assays (Supplementary Fig 1A–C online). We then examined the activity of C/EBPβ in the presence of SHARP1 by using reporter assays (Supplementary Fig 1D online). C/EBPβ-activated reporter activity was downregulated by SHARP1 in a dose-dependent manner. Furthermore, SHARP1 also inhibited C/EBPα-induced PPARγ promoter activity, indicating that SHARP1 regulates the transcriptional activity of both C/EBPβ and C/EBPα.

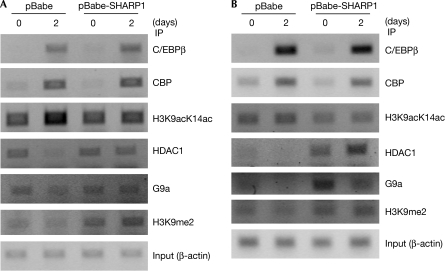

SHARP1 retains HDAC1 and G9a on adipogenic promoters

To examine the mechanisms underlying reduced expression of C/EBPα and PPARγ2, ChIP assays were performed. During differentiation, an increase in H3K9acK14ac—a mark of transcriptionally active regions—was seen at the C/EBPα promoter (Fig 4A) in a region encompassing the C/EBP site in control cells but not in SHARP1-overexpressing cells. H3K9acK14ac levels were also lower at the PPARγ2 promoter in SHARP1-overexpressing cells (Fig 4B). Reduced acetylation could be due to sustained recruitment of HDACs, reduced recruitment of co-activators or changes in histone H3 methylation (K9) associated with transcriptional repression. Therefore, we analysed HDAC1, the histone methyltransferase G9a that methylates K9 and K27 of histone H3, as well as the levels of CREB binding protein (CBP). HDAC1 and G9a levels were downregulated during differentiation of control cells (Yoo et al, 2006), whereas SHARP1-overexpressing cells retained HDAC1 and G9a on both promoters. Consistent with sustained G9a, an increase in H3K9me2 was apparent in SHARP1-overexpressing cells, with no change in CBP recruitment. These results indicate that reduced expression of C/EBPα and PPARγ2 is probably due to sustained levels of HDAC1 and/or G9a rather than the loss of activity of histone acetyl transferase (HAT).

Figure 4.

SHARP1 retains HDAC1 and G9a on the C/EBPα and PPARγ2 promoters. ChIP assays were performed for histone modifications (acetylated H3; methylated H3), chromatin modifiers (CBP, HDAC1 and G9a) and transcriptional activators (C/EBPβ) on (A) the C/EBPα promoter, and (B) PPARγ2 promoter, in control (pBabe) and pBabe-SHARP1 cells in undifferentiated cells (day 0) and after 2 days of differentiation. Primers flanking the C/EBP site on both promoters were used for PCR. Input DNA (10%) was used as a control. C/EBP, CCAAT/enhancer binding protein; ChIP, chromatin immunoprecipitation; HDAC, histone deacetylase; PPAR, peroxisome proliferator activated receptor.

SHARP1 retains co-repressors on adipogenic promoters

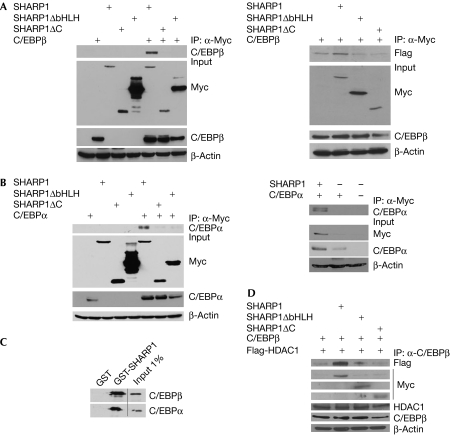

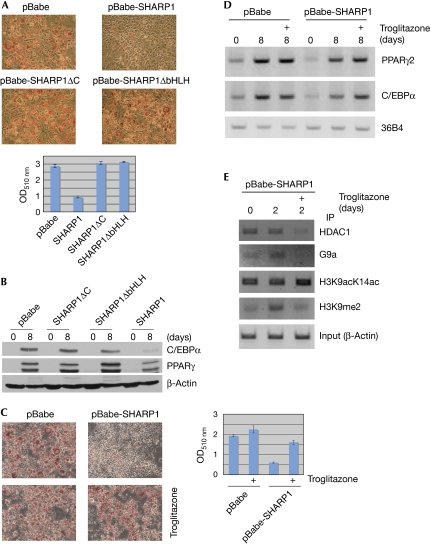

As SHARP1 prevents dissociation of HDAC1 and G9a on the C/EBPα and PPARγ2 promoters in a region that contains the C/EBP regulatory site, we tested whether SHARP1 interacts with C/EBPs. NIH3T3 and 3T3L1 cells were transfected with full-length Myc-SHARP1 or its deletion mutants SHARP1ΔC and SHARP1ΔbHLH, along with C/EBPβ. Full-length SHARP1 interacted with C/EBPβ, whereas no interaction was seen with SHARP1ΔC or SHARP1ΔbHLH in NIH3T3 cells (Fig 5A, left panel), or 3T3L1 cells (Fig 5A, right panel; Supplementary Fig 2 online). Similarly, full-length SHARP1 interacted with C/EBPα in NIH3T3 and 3T3L1 cells (Fig 5B, left and right panels, respectively). Both C/EBPβ and C/EBPα showed a direct interaction with SHARP1, as seen by glutathione S-transferase (GST) pull-down assays (Fig 5C). Previous studies have shown an interaction between C/EBPβ and HDAC1 (Wiper-Bergeron et al, 2003). As SHARP1 interacts with CEBPβ, we investigated the effect of SHARP1 on the CEBPβ–HDAC1 complex. Interestingly, only full-length SHARP1 increased the association of C/EBPβ with HDAC1 (Fig 5D), indicating that SHARP1 might inhibit the transcriptional activity of C/EBP through enhanced co-repressor recruitment. To test whether interaction with C/EBPβ is essential for the inhibition of adipogenesis, SHARP1, SHARP1ΔC and SHARP1ΔbHLH were expressed in 3T3L1 cells. In contrast to full-length SHARP1, neither mutant inhibited adipogenic differentiation (Fig 6A) or expression of C/EBPα and PPARγ (Fig 6B), indicating that the interaction of SHARP1 with C/EBPβ is essential for SHARP1-mediated inhibition of adipogenesis. In addition to regulating the expression of C/EBPα and PPARγ2, C/EBPβ also regulates PPARγ ligand production (Hamm et al, 2001), which is essential for the removal of HDAC1 from the C/EBPα promoter (Zuo et al, 2006). Therefore, we tested the effect of troglitazone on SHARP1-mediated inhibition of adipogenesis. Interestingly, troglitazone rescued the differentiation defect in cells overexpressing SHARP1, and the expression of PPARγ2 and C/EBPα was also restored (Fig 6C,D). Furthermore, during differentiation, HDAC1, G9a and H3K9me2 levels were reduced on the C/EBPα promoter by treatment with troglitazone (Fig 6E), indicating that reduced PPARγ ligand production underlies the sustained presence of HDAC1 and G9a, and inhibition of adipogenesis.

Figure 5.

SHARP1 interacts with C/EBPs and enhances C/EBPβ–HDAC1 association. (A) NIH3T3 cells (left panel) and 3T3L1 cells (right panel) were transfected with Flag-C/EBPβ and Myc-SHARP1 constructs as indicated. Proteins were immunoprecipitated (IP) with anti-Myc agarose beads and immunoblotted with C/EBPβ antibody. The expression of SHARP1 and C/EBPβ was analysed by Western blot. (B) NIH3T3 cells (left panel) and 3T3L1 cells (right panel) transfected with C/EBPα and Myc-SHARP1 constructs were immunoprecipitated with anti-Myc agarose beads and immunoblotted with C/EBPα antibody. The expression of SHARP1 and C/EBPα was analysed by Western blot. (C) 35S-labelled in vitro translated C/EBPβ and C/EBPα were tested for interaction with equivalent amounts of GST or GST-SHARP1; 1% input was run as a control. (D) 3T3L1 cells were transfected with Flag-C/EBPβ and Flag-HDAC1 alone, or in the presence of full-length Myc-SHARP1 and deletion mutants. Proteins were immunoprecipitated with C/EBPβ antibody, and immunoblotted with Flag antibody. Lysates were analysed for the expression of SHARP1, C/EBPβ and HDAC1 by Western blot. C/EBP, CCAAT/enhancer binding protein; GST, glutathione S-transferase; HDAC, histone deacetylase.

Figure 6.

Interaction of SHARP1 with C/EBPβ is essential for the inhibition of adipogenic differentiation, and troglitazone reverses SHARP1-mediated block of adipogenesis. (A) 3T3L1 cells were infected with vector (pBabe), SHARP1, SHARP1ΔC and SHARP1ΔbHLH. Differentiated cells were stained with ORO dye. Dye extracted from cells was measured at OD510 nm. (B) Lysates were analysed at days 0 and 8 of differentiation for the expression of C/EBPα and PPARγ2 by Western blot. Protein loading was normalized with β-actin. (C) Control and SHARP1-infected cells were differentiated in the absence (upper panels) and presence of 5 μM troglitazone and stained with ORO. Extracted dye was measured at OD510 nm (right panel). (D) RT–PCR was performed for PPARγ2, C/EBPα and 36B4 using days 0 and 8 troglitazone-untreated and -treated (+) samples. (E) Cells overexpressing SHARP1 were differentiated with or without 5 μM troglitazone. ChIP assays were performed at 0 and 2 days after differentiation using HDAC1, G9a, H3K9acK14ac and H3K9me2 antibodies. C/EBPα promoter was amplified by PCR; β-Actin promoter was amplified to normalize input DNA. C/EBP, CCAAT/enhancer binding protein; ChIP, chromatin immunoprecipitation; OD, optical density; ORO, Oil-Red-O; PPAR, peroxisome proliferator activated receptor; RT–PCR, reverse transcription–PCR.

Taken together, our results show a new function for SHARP1 in regulating the transition from preadipocytes to adipocytes through regulation of C/EBP activity. The activity of C/EBPβ is essential for the expression of C/EBPα and PPARγ2. In addition, the activity of C/EBPβ and SREBP1c has been implicated in PPARγ ligand production (Kim et al, 1998; Hamm et al, 2001), which is required to dislodge HDAC1 from the C/EBPα promoter (Zuo et al, 2006). The downregulation of SREBP1c expression in SHARP1-overexpressing cells might contribute to the retention of co-repressors on adipogenic promoters. However, SHARP1 mutants that fail to interact with C/EBPβ do not inhibit differentiation. Furthermore, SHARP1 increases the association of CEBPβ with HDAC1. These results suggest that SHARP1 enhances and might stabilize the interaction of co-repressors with C/EBPβ, resulting in the sustained presence of HDAC1 and G9a on the C/EBP regulatory sites in adipogenic promoters. The failure to dissociate co-repressors probably results in epigenetic changes that lead to the suppression of C/EBPα and PPARγ2 expression and adipogenic differentiation. In addition to regulating early stages of the adipogenic programme through C/EBPβ, the upregulation of SHARP1 during terminal differentiation might be important to curtail the activity of C/EBPα and thereby regulate late stages of differentiation. Given its effect on adipogenesis, aberrant SHARP1 function might be associated with obesity and obesity-related diseases.

Methods

Mice. Wild-type mice (5 weeks old) were fed with normal or a high-fat diet (Research Diets, New Brunswick, NJ, USA) for 5 months. RNA was isolated from fat pads and analysed for the expression of SHARP1. SHARP1−/− mice were recently described (Rossner et al, 2008). All animal protocols followed institutional guidelines.

Cell culture. Wild-type and SHARP1−/− MEF cells were generated from littermate embryos as described previously (Sun et al, 2007b). 3T3L1, 10T1/2, Phoenix cells and MEFs were cultured in Dulbecco's modified Eagle's medium with 10% fetal bovine serum. NIH3T3 cells were cultured in Dulbecco's modified Eagle's medium with 10% bovine serum.

Plasmid constructs. pCS2-Myc-SHARP1 (amino acids 1–410) and GST-SHARP1 have been described previously (Azmi et al, 2003). Deletion mutants containing the bHLH domain of SHARP1 (SHARP1ΔC; amino acids 1–112), or the carboxy-terminal region (SHARP1ΔbHLH; amino acids 112–410) were cloned by PCR into pCS2 and pBabe-puro vectors. Primers used for amplification are provided in Supplementary Table I online. Haemagglutinin (HA)-C/EBPα, Flag-C/EBPβ and C/EBP-luc were provided by D. Tenen, pMCSV-C/EBPα by O. McDougald, PPARγ-luc by R. Derynck and Flag-HDAC1 by S. Schreiber.

Retroviral infection and adipogenic differentiation. 3T3L1 cells were infected with viral supernatant in the presence of 8 μg/ml polybrene, and selected with 4 μg/ml puromycin. For rescue experiments, SHARP1-expressing cells were reinfected with pMCSV-C/EBPα, and selected with 100 μg/ml hygromycin. Differentiation of 3T3L1 and MEFs was induced with 3-isobutyl-1-methylxanthine (0.5 mM), insulin (1 μg/ml) and dexamethasone (250 μM) for 2 days, replaced with a medium containing 1 μg/ml insulin for 2 days, followed by growth medium. Troglitazone (5 μM) was added on the first 2 days of differentiation. Differentiated cells were fixed and stained with 0.5% ORO.

Co-immunoprecipitation and GST pull-down assays. Co-immunoprecipitation and GST assays were carried out as described previously (Azmi et al, 2004). For co-immunoprecipitation assays, NIH3T3 and 3T3L1 cells were transfected using Lipofectamine Plus (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA, USA) with Myc-SHARP1 constructs, Flag-C/EBPβ, HA-C/EBPα and Flag-HDAC1 as indicated. Cell lysates were prepared using radioimmunoprecipitation assay buffer, and immunoprecipitated and immunoblotted with appropriate antibodies as described in the figure legends. For GST assays, 5 μg of GST-SHARP1 or GST protein was incubated with 5 μl of in vitro translated 35S-methionine-labelled C/EBPβ or C/EBPα protein. GST beads were washed and run on SDS–PAGE gels.

Electro mobility shift assay. Nuclear extracts (10 μg) and poly dI-dC (25 ng/μl) were incubated with 32P-labelled double-stranded oligonucleotides containing the C/EBP consensus element 5′-TGCAGATTGCGCAATCTGCA-3′. For supershift assays, 0.2 μg of antibody was preincubated with nuclear lysate before the addition of probe. Samples were run on 5% polyacrylamide gels and exposed for autoradiography.

ChIP. Assays were performed using the ChIP assay kit (Millipore, Billerica, MA, USA) as described previously (Azmi et al, 2003). Here, 2 μg C/EBPβ, CBP, HDAC1 (Santa Cruz, Santa Cruz, CA, USA), acetyl-H3 (K9K14) and dimethyl-H3 (K9; Upstate) and 10 μg G9a (Nishio & Walsh, 2004) antibodies were used for immunoprecipitation. Primers for amplification of C/EBPα, PPARγ2 and β-actin promoters are provided in Supplementary Table II online.

Reverse transcription–PCR. RNA isolated with Trizol (Invitrogen) was reverse transcribed with AMV reverse transcriptase (Promega, Madison, WI, USA). The cDNA was amplified with primers specific to SHARP1, C/EBPα, PPARγ, GLUT4, AP2, SREBP1c, PREF1 and 36B4. Primer sequences are provided in Supplementary Table III online. Quantitative PCR was carried out as described previously (Sun et al, 2007c). Primer sequences are provided in Supplementary Table IV online.

Supplementary information is available at EMBO reports online (http://www.emboreports.org).

Supplementary Material

Supplementary Information

Acknowledgments

We thank R. Derynck, O. MacDougald, P. Scherer, S. Schreiber and D. Tenen for reagents, and T.-K. Chung for assistance with the preparation of the paper. This study was supported in part by funds from the March of Dimes, and a Scholar Award from the Leukemia and Lymphoma Society (R.T.).

Footnotes

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

References

- Azmi S, Taneja R (2002) Embryonic expression of mSharp-1/mDEC2, which encodes a basic helix-loop-helix transcription factor. Mech Dev 114: 181–185 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Azmi S, Sun H, Ozog A, Taneja R (2003) mSharp-1/DEC2, a basic helix-loop-helix protein functions as a transcriptional repressor of E box activity and Stra13 expression. J Biol Chem 278: 20098–20109 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Azmi S, Ozog A, Taneja R (2004) Sharp-1/DEC2 inhibits skeletal muscle differentiation through repression of myogenic transcription factors. J Biol Chem 279: 52643–52652 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Christy RJ, Kaestner KH, Geiman DE, Lane MD (1991) CCAAT/enhancer binding protein gene promoter: binding of nuclear factors during differentiation of 3T3-L1 preadipocytes. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 88: 2593–2597 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clarke SL, Robinson CE, Gimble JM (1997) CAAT/enhancer binding proteins directly modulate transcription from the peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor γ 2 promoter. Biochem Biophys Res Commun 240: 99–103 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Farmer SR (2006) Transcriptional control of adipocyte formation. Cell Metab 4: 263–273 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fujimoto K, Shen M, Noshiro M, Matsubara K, Shingu S, Honda K, Yoshida E, Suardita K, Matsuda Y, Kato Y (2001) Molecular cloning and characterization of DEC2, a new member of basic helix-loop-helix proteins. Biochem Biophys Res Commun 280: 164–171 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hamm JK, Park BH, Farmer SR (2001) A role for C/EBPβ in regulating peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor γ activity during adipogenesis in 3T3-L1 preadipocytes. J Biol Chem 276: 18464–18471 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim JB, Wright HM, Wright M, Spiegelman BM (1998) ADD1/SREBP1 activates PPARγ through the production of endogenous ligand. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 95: 4333–4337 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morosetti R et al. (2006) MyoD expression restores defective myogenic differentiation of human mesoangioblasts from inclusion-body myositis muscle. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 103: 16995–17000 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nishio H, Walsh MJ (2004) CCAAT displacement protein/cut homolog recruits G9a histone lysine methyltransferase to repress transcription. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 101: 11257–11262 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rosen ED, MacDougald OA (2006) Adipocyte differentiation from the inside out. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol 7: 885–896 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rosen ED, Walkey CJ, Puigserver P, Spiegelman BM (2000) Transcriptional regulation of adipogenesis. Genes Dev 14: 1293–1307 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rossner MJ, Dorr J, Gass P, Schwab MH, Nave KA (1997) SHARPs: mammalian enhancer-of-split- and hairy-related proteins coupled to neuronal stimulation. Mol Cell Neurosci 10: 460–475 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rossner MJ, Oster H, Wichert SP, Reinecke L, Wehr MC, Reinecke J, Eichele G, Taneja R, Nave KA (2008) Disturbed clockwork resetting in sharp-1 and sharp-2 single and double mutant mice. PLoS ONE 3: e2762. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sun H, Ghaffari S, Taneja R (2007a) bHLH-orange transcription factors in development and cancer. Translational Oncogenomics 2: 105–118 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sun H, Gulbagci NT, Taneja R (2007b) Analysis of growth properties and cell cycle regulation using mouse embryonic fibroblast cells. Methods Mol Biol 383: 311–319 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sun H, Li L, Vercherat C, Gulbagci NT, Acharjee S, Li J, Chung TK, Thin TH, Taneja R (2007c) Stra13 regulates satellite cell activation by antagonizing Notch signaling. J Cell Biol 177: 647–657 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wiper-Bergeron N, Wu D, Pope L, Schild-Poulter C, Haché R (2003) Stimulation of preadipocyte differentiation by steroid through targeting of an HDAC1 complex. EMBO J 22: 2135–2145 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wu Z, Bucher NL, Farmer SR (1996) Induction of peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor γ during the conversion of 3T3 fibroblasts into adipocytes is mediated by C/EBPβ, C/EBPδ, and glucocorticoids. Mol Cell Biol 16: 4128–4136 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wu Z, Rosen ED, Brun R, Hauser S, Adelmant G, Troy AE, McKeon C, Darlington GJ, Spiegelman BM (1999) Cross-regulation of C/EBP α and PPAR γ controls the transcriptional pathway of adipogenesis and insulin sensitivity. Mol Cell 3: 151–158 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yoo EJ, Chung JJ, Choe SS, Kim KH, Kim JB (2006) Down-regulation of histone deacetylases stimulates adipocyte differentiation. J Biol Chem 281: 6608–6615 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zuo Y, Qiang L, Farmer SR (2006) Activation of CCAAT/enhancer-binding protein (C/EBP) α expression by C/EBP β during adipogenesis requires a peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor-γ-associated repression of HDAC1 at the C/ebp α gene promoter. J Biol Chem 281: 7960–7967 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Supplementary Information