Abstract

The Look AHEAD (Action for Health in Diabetes) study is a multi-center, randomized controlled trial, designed to determine whether intentional weight loss reduces cardiovascular morbidity and mortality in overweight individuals with type 2 diabetes. The study began in 2001 and is scheduled to conclude in 2012. A total of 5,145 participants, with a mean age of 60 years and body mass index of 36.0 kg/m2, have been randomly assigned to a lifestyle intervention or to enhanced usual care condition (i.e., Diabetes Support and Education). This article describes the lifestyle intervention and the empirical evidence to support it. The two principal intervention goals are to induce a mean loss ≥ 7% of initial weight and to increase participants’ moderately-intense physical activity to ≥ 175 minutes a week. For the first 6 months, participants attend one individual and three group sessions per month and are encouraged to replace two meals and one snack a day with liquid shakes and meal bars. From months 7−12, they attend one individual and two group meetings per month and continue to replace one meal per day (which is recommended for the duration of the program). Starting at month 7, more intensive behavioral interventions, as well as weight loss medication, are available from a toolbox, designed to help participants with limited weight loss. In years 2−4, treatment is provided mainly on an individual basis and includes at least one on-site visit per month and a second contact by telephone, mail, or e-mail. Short-term (6−8 weeks) refresher groups and motivational campaigns also are offered three times yearly to help participants reverse small weight gains. After year 4, participants are offered monthly individual visits, as well as one refresher group and one campaign a year. The intervention is delivered by a multi-disciplinary team that includes medical staff who monitor participants at risk of hypoglycemic episodes. The study's evidence-based protocol should be of use to researchers, as well as to practitioners who care for overweight individuals with type 2 diabetes.

Keywords: weight loss, diet, physical activity, lifestyle modification, weight maintenance

In June 2001 the National Institutes of Health launched the Look AHEAD (Action for Health in Diabetes) study to provide a definitive assessment of the long-term health consequences of intentional weight loss (1). This 16-center investigation, which has enrolled 5,145 overweight individuals with type 2 diabetes, will examine cardiovascular morbidity and mortality for up to 12 years in persons randomly assigned to one of two conditions. Participants in a Diabetes Support and Education (DSE) group receive usual medical care, provided by their own primary care physicians, plus three group educational sessions per year for the first 4 years. Participants in a Lifestyle Intervention group receive usual medical care, combined with an intensive 4-year program designed to increase physical activity and reduce initial weight by 7% or more. Data in Table 1 show that, at the time of randomization, participants in both groups had a mean age of nearly 60 years and a body mass of approximately 36 kg/m2. Nearly 60% of participants are women, and the sample is ethnically diverse with approximately 16% African American, 13% Hispanic, and 5% Native American/Alaskan native. In addition to having type 2 diabetes (for an average of 6.8 yr), 80% of participants in both groups have hypertension, 93% meet criteria for metabolic syndrome, and 14% have a history of cardiovascular disease.

Table 1.

Baseline characteristics of participants in the Lifestyle Intervention and Diabetes Support and Education groups.

| Variable | Lifestyle Intervention (N=2570) | Diabetes Support and Education (N=2575) |

|---|---|---|

| Age (yr) | 58.6 ± 6.8 | 58.9 ± 6.9 |

| Height (cm) | 167.2 ± 9.6 | 167.3 ± 9.9 |

| Weight (kg) | 100.5 ± 19.7 | 100.9 ± 18.8 |

| Body mass index (kg/m2) | 35.9 ± 6.0 | 36.0 ± 5.8 |

| Sex (% female) | 1524 (59.3%) | 1534 (59.6%) |

| Ethnicity/race | ||

| White | 1618 (63.1%) | 1628 (63.4%) |

| African American/Black | 398 (15.5%) | 405 (15.8%) |

| Hispanic | 338 (13.2%) | 337 (13.1%) |

| Native American/Alaskan Native | 131 (5.1%) | 129 (5.0%) |

| Asian/Pacific Islander | 29 (1.1%) | 21 (0.8%) |

| Other | 49 (1.9%) | 49 (1.9%) |

Look AHEAD is the first randomized controlled trial (RCT) to assess whether weight reduction, combined with increased physical activity, reduces cardiovascular morbidity and mortality (1). The study has statistical power to detect an 18% difference between the two groups in time to occurrence of first fatal myocardial infarction (MI) or stroke, as well as non-fatal MI or stroke, during up to 11.5 years of follow-up. These are the trial's principal outcomes, although multiple other end points (e.g., coronary artery by-bass) also are assessed annually.

Look AHEAD follows closely upon the Diabetes Prevention Program (DPP) which found that a lifestyle intervention significantly decreased the risk of developing type 2 diabetes in overweight individuals with impaired glucose tolerance (2). Two other investigations yielded similar findings (3,4).

Key components of Look AHEAD's lifestyle intervention have been described briefly in a summary of the study's design (1). The present report provides a fuller description of the intervention and reviews the evidence that guided development of the program. In all cases, Look AHEAD's steering committee sought to select treatment goals and methods that were supported by RCTs. In the absence of such data, the steering committee (hereafter referred to as Look AHEAD) relied on uncontrolled studies and clinical judgment. The treatment protocol combines multiple diet and exercise approaches in an effort to maximize the number of participants who meet the study's weight and activity goals. If this broad intervention is successful in reducing cardiovascular events, future trials may examine whether one method of losing weight (or increasing activity) is superior to another.

Principal Goals of the Lifestyle Intervention

Weight Loss Goal

The two principal goals of the intervention are to achieve a mean loss ≥ 7% of initial weight and to increase participants’ physical activity to ≥ 175 minutes a week. The weight loss goal was based on findings that it is achievable in overweight individuals with type 2 diabetes. Several RCTs, summarized in Table 2, achieved a mean loss of 7%−10% of initial weight in 16−26 weeks of treatment by diet, exercise, and behavior therapy (5-9). Losses of this size improve glycemic control in patients with type 2 diabetes (10) and ameliorate blood pressure (11) and lipids (12) in clinically affected individuals.

Table 2.

Summary of selected studies of weight loss in obese patients with type 2 diabetes treated by comprehensive lifestyle intervention.

| Study | Weeks of Treatment | kcal/d | Mean % Reduction in Initial Weight | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| End of Treatment | Follow-Up | |||

| Guare et al. (5) | 16 | 20 kcal/kg wt. | 8.0% | 2.2% (at 1 yr) |

| Pascale et al. (6) | 16 | 1000−1500 | 8.2% | 5.5% (at 1 yr) |

| Wing et al. (7) | 20 | 1000−1200 | 9.7% | 6.5% (at 1 yr) |

| Wing et al. (8) | 50 | 1000−1200 | 9.7% | 5.5% (at 1 yr) |

Note: Percentage reduction in weight was estimated, in some cases, from weight loss reported in kg. For each study, the table shows only the treatment group that was provided lifestyle modification in combination with a conventional program of diet and physical activity.

Larger weight losses are generally associated with greater improvements in HbA1c and other health outcomes as shown, for example, by Wing et al. (10). Thus, Look AHEAD had to balance the potential benefits of inducing losses of 15%−20% of initial weight, achieved with very-low-calorie diets, against findings that losses of this size are usually followed by rapid weight regain (7,13-16), even when participants are provided weight-maintenance therapy (13). Look AHEAD ultimately selected a moderate weight loss goal it believed could be maintained. Each of the 16 study centers is expected, during the first year, to obtain a mean loss ≥ 7% of initial weight. Individual lifestyle participants, however, are given a goal of losing 10% or more of initial weight. This higher individual goal was selected to increase the likelihood that the study would achieve a mean loss ≥ 7%.

Physical Activity Goal

The intervention's physical activity goal is ≥ 175 minutes a week of moderately intense activity, achieved by the sixth month. Participants are instructed to engage in brisk walking or similar aerobic activity. The activity program relies on unsupervised (at-home) exercise. The activity goal is consistent with an expert panel's recommendation that adults “accumulate at least 30 minutes of at least moderate-intensity physical activity over the course of most, preferably all, days of the week” (17). This prescription often is interpreted as ≥ 150 minutes activity a week, which was the goal of the DPP (2,18). Look AHEAD selected a more ambitious target (≥ 175 minutes/week), given findings that higher levels of physical activity (> 200 minutes/week or > 2500 kcal/week) significantly improve the maintenance of lost weight (19,20). In addition, high levels of physical activity may reduce blood glucose, insulin, blood pressure, and lipid levels in the absence of significant weight loss (21). Cross-sectional studies also have suggested that fitness reduces the risk of cardiovascular mortality and morbidity, independent of body weight (21,22). Look AHEAD's activity goal falls short of recent recommendations that people who wish to lose weight exercise ≥ 60 minutes/day (23).

Overview of the Lifestyle Intervention

Table 3 presents a synopsis of the intervention over the three phases of treatment. Phase I lasts 1 year and is designed to achieve the study's initial weight loss and activity goals. Participants attend weekly on-site treatment sessions the first 6 months and three sessions per month during months 7−12. During Phase II, from years 2 − 4, they attend a minimum of one on-site visit per month, with at least one additional contact by telephone, mail, or e-mail. The goal during this phase is to maintain the improvements in weight and activity. Phase III extends from year 5 until the participant's final study visit, which will average 10.25 years from randomization. Participants are offered monthly individual (on-site) visits during this time.

Table 3.

Overview of the Look AHEAD Lifestyle Intervention

| Frequency of On-Site Visits | Format of Treatment Sessions | Weight Loss Goal | Activity Goal | Special Features | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Phase I | |||||

| Months 1−6 | Weekly | 3 group, 1 individual. | Lose ≥ 10% of initial weight. | Exercise ≥ 175 min/wk by mo. 6. | Treatment toolbox |

| Months 7−12 | 3 per mo. | 2 group, 1 individual. | Continued loss or weight maintenance. | Increase min/wk of activity; 10,000 steps/day goal. | Advanced toolbox options; orlistat. |

| Phase II | |||||

| Years 2−4 | Minimum of 1 per mo. | 1 individual with minimum of 1 additional contact by phone, mail, or e-mail. | Weight maintenance, reverse weight gain as it occurs. | Maintain high levels of physical activity. | Refresher Groups to reverse weight gain; National Campaigns across 16 centers. |

| Phase III | |||||

| Year 5+ | Monthly Recommended. | individual | Prevention of weight gain. | Prevention of inactivity. | Refresher groups; Campaigns; open groups. |

The lifestyle intervention relies heavily on the DPP protocol (2,18) but has been adapted for use with individuals who already have developed type 2 diabetes. In addition, based on recent empirical findings, Look AHEAD has diverged from the DPP in providing: 1) primarily group (rather than individual) treatment during the first year; 2) liquid meal replacements; and 3) the option of weight loss medication, after the first 6 months, with selected individuals. These and other components of the intervention are described below.

Phase I: Months 1−6

Treatment Frequency and Format

Lifestyle participants attend 24 treatment sessions during the first 6 months. Weekly treatment of 16−26 weeks is standard in the behavioral management of obesity (24,25). Look AHEAD selected the longer duration (i.e., 6 months) because longer therapy generally induces greater weight loss (25). However, weekly treatment of up to 1 year produces only marginally greater weight loss than that achieved in 6 months (8,13). Mean weight loss generally plateaus at 6 months with all interventions, except bariatric surgery (25-27).

Format

The intervention combines group and individual treatment. Participants at each center are assigned to a group of approximately 10−20 persons with whom they attend classes for the entire year. During the first 6 months, they attend group sessions (of 60−75 minutes) for the first 3 weeks of each month. The fourth week they have an individual meeting (20−30 minutes) with their lifestyle counselor, who remains the same staff person throughout the first year (and preferably beyond). Group meetings are not held this week. Monthly individual meetings give participants a chance to review specific questions or problems. They also allow lifestyle counselors to tailor treatment to participants’ individual needs, including those related to cultural or ethnic differences.

This mix of group and individual treatment was selected to reap the potential benefits of each approach. In addition to reducing costs, group treatment provides social support and a potentially healthy dose of competition (24). A 6-month RCT demonstrated the superiority of group over individual counseling in inducing weight loss, regardless of the individual's preferred method of treatment (28).

Despite the benefits of group treatment, several Look AHEAD members who had served as DPP interventionists believed that individual contact was critical to retaining participants in Look AHEAD's multi-year intervention. Individual treatment, compared with group, potentially creates a stronger bond with participants, allowing them to share more details about their family members, work, or special occasions. This strong personal relationship is viewed as a safety net for participants who stop attending group sessions regularly, which is a common occurrence after the first 6−12 months (13,29). No RCTs have assessed the benefits of combining group and individual treatment. This approach, however, was used successfully in a weight loss study of older adults with hypertension (30).

Dietary Intervention

The first week of treatment participants are instructed to eat a self-selected diet of conventional foods and to record their intake. The second week they consume a similar diet but restrict their intake. The energy goal for persons < 114 kg (250 lb) is 1200−1500 kcal/d and is 1500−1800 kcal/d for individuals ≥ 114 kg. Participants count calories and fat grams with the aid of a booklet provided. They are prescribed < 30% of calories from fat, with < 10% from saturated fat. This is similar to the diet prescribed in the DPP (18).

Portion control

During weeks 3−19, a portion-controlled meal plan is prescribed to facilitate participants’ adherence to their calorie goals. All individuals are encouraged to replace two meals (typically breakfast and lunch) with a liquid shake and one snack with a bar (31). They are to consume an evening meal of conventional foods (which includes the option of frozen food entrees) and to add fruits and vegetables to their diet until they reach their daily calorie goal. Participants potentially can choose from four meal replacements, including SlimFast (SlimFast Foods), Glucerna (Ross Laboratories), OPTIFAST (Novartis Nutrition) and HMR (HMR, Inc.). All products are provided free of charge. Persons who decline meal replacements are provided detailed menu plans that specify conventional foods to be consumed. A variety of meals are offered but all are intended to control portion sizes and calories. From weeks 20−22, participants decrease their use of meal replacements while increasing the consumption of conventional foods.

Rationale for portion control

Meal replacements were included, within a diet of 1200−1500 kcal/d, because they significantly increase weight loss compared with prescribing isocaloric diets comprised of conventional foods (31). A meta-analysis of six RCTs showed that liquid meal replacements induced a loss approximately 3 kg greater than that produced by a conventional diet (32). Obese individuals typically underestimate their calorie intake by 40%−50% when consuming a diet of conventional foods (33) because of difficulty in estimating portion sizes, macronutrient composition, and calorie content, as well as in remembering all foods consumed. Meal replacements appear to decrease these difficulties and simplify food choices (24). Portion-controlled servings of conventional foods similarly facilitate weight loss, as shown by Jeffery and Wing (34), and other investigators (35,36). Ultimately, simply providing patients detailed menu plans, with accompanying shopping lists, provides sufficient structure to significantly increase weight loss (37).

Look AHEAD investigators initially were concerned that the high sugar content of some meal replacement products might adversely affect glycemic control. This concern, however, was alleviated by findings in patients with type 2 diabetes that a meal-replacement plan (that included SlimFast) was associated with significantly greater weight losses and reductions in fasting blood sugar than was a conventional reducing diet with the same calorie goal (38). Additional studies found that when participants achieved significant negative energy balance, as expected in Look AHEAD, short-term gylcemic control improved, independent of weight loss (39,40).

Physical Activity Intervention

Look AHEAD participants complete an exercise tolerance test at baseline to increase the likelihood that they can safely engage in moderately intense physical activity. The first month, participants are instructed to walk (i.e., or otherwise exercise) for at least 50 minutes a week. Activity bouts ≥ 10 minutes may be counted toward the weekly goal, given findings that four 10-minute bouts, spread across the day, result in comparable improvements in fitness as one continuous 40-minute bout (41). (Shorter bouts do not count toward the goal.) Activity is increased to ≥ 125 minutes/week by week 16 and ≥ 175 minutes/week by week 26. Group sessions review numerous activity-related topics, including methods of exercising safely, as well as the benefits of strength training (17), which may comprise up to 25% of the weekly goal.

Lifestyle activity

Participants also are encouraged to increase their lifestyle activity by methods such as using stairs rather than elevators, walking rather than riding, and reducing use of labor saving devices (e.g., e-mailing colleagues at work). Lifestyle activity is as effective as programmed (aerobic) activity in inducing and maintaining weight loss (42,43) and in improving cardiovascular risk factors (44). Participants increase their lifestyle activity, in part, by using a pedometer, provided at week 7. They are instructed to increase their daily steps by 250 a week, until they reach a goal ≥ 10,000 steps/day (45). Strolling in the mall (i.e., lifestyle activity) would count toward the step goal but not the 175 minutes/week target (because strolling is not moderately intense activity).

Supervised activity

Centers may offer supervised activity classes, provided they are consistent with the institution's risk management policies. The lifestyle intervention, however, relies principally on at-home exercise because it is easier to implement and is associated with greater minutes of weekly exercise and better maintenance of weight loss than is on-site physical activity (46,47).

Behavior Modification Curriculum

The 6-month, 16-session DPP protocol was modified for Look AHEAD to include group treatment and the changes in diet and activity described previously. Each group session typically introduces one or two new topics in behavioral weight control, including recording food intake and physical activity, eating at regular times, limiting times and places of eating, and coping with negative thoughts related to overeating (24). All major topics are accompanied by a homework assignment. Of these, recording daily food intake and physical activity are likely the most important. Participants total their calories for each day (and for the week) and report at group sessions their success in meeting their targets. Numerous studies have shown that the more frequently participants record their food intake, the more weight they lose (and keep off) (48-50). Weight also is measured at each visit to provide additional feedback on adherence and to increase motivation. More frequent weighing is associated with better weight loss (51).

Special Treatment Components: A Toolbox

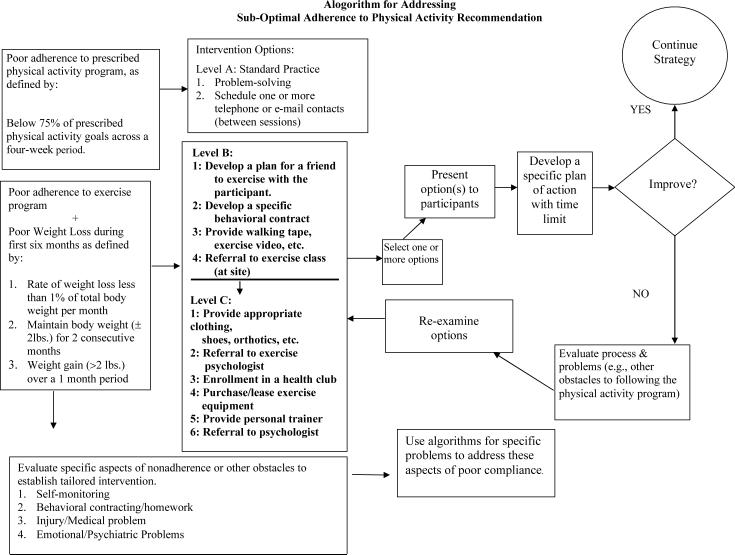

Participants who have difficulty adhering to the diet and exercise recommendations, or who lose < 1% of weight per month, are eligible for special interventions from the program's toolbox. Interventions are suggested by a series of algorithms, following a detailed assessment of the problem behavior. In the first 6 months, most interventions utilize elements of motivational interviewing (52) and problem solving skills (53), as well as additional individual contacts with the lifestyle counselor. Written contracts may be used to identify goals and how, when, and where participants will modify their behaviors to achieve them. The success of the intervention is evaluated using predetermined criteria. The efficacy of a toolbox per se has not been evaluated by RCTs, although a similar approach was used in the DPP (18). Figure 1 presents an algorithm for addressing sub-optimal adherence to physical activity recommendations.

Figure 1.

The figure shows an algorithm used to assist individuals who are not meeting the recommended activity goals. With all treatment algorithms used in Look AHEAD, Level A interventions involve the use of standard methods of care, provided during regular treatment visits. Level B interventions require more detailed assessment and planning and possibly modest financial expenditures. Level C interventions are the most intensive and costly.

Phase I: Months 7 −12

Treatment Frequency and Format

During months 7−12, participants attend two group meetings a month and one individual session. The decreased schedule of visits represents an effort to support patients’ efforts to maintain their weight loss (and physical activity) but not burden them with the demands of weekly attendance. Weight loss participants frequently report that they do not enjoy this stage of therapy as much as the first 6 months, principally because they lose little or no weight, despite working just as hard (13,54). In addition, the excitement of the treatment sessions and of new acquaintances declines over time. Several RCTs found that twice monthly group meetings facilitated the maintenance of lost weight while retaining participants in treatment (53,55,56). Thus, Look AHEAD selected this schedule of group meetings, while also continuing individual sessions with the lifestyle counselor. On the “off” week each month, when they do not have a meeting, participants are instructed to weigh themselves at home and to review their eating and activity records. With this increased autonomy, they are encouraged to develop habits associated with successful weight maintenance (57).

Diet and Physical Activity Intervention

After the first 6 months, calorie targets are personalized based on participants’ weight loss goals. Those who wish to lose more weight, or to reverse small weight gains, are encouraged to induce an energy deficit of approximately 500 kcal/d. Such dieting may be discontinued with participants who have achieved their weight loss goals. Group sessions during this time emphasize eating more fruits and vegetables and other foods consistent with a low-energy density diet (58). This approach, which is taught following the book Volumetrics (59), is based on findings that satiation is influenced by the weight or amount of food eaten, rather than the energy content of the meal (60,61). Eating a low energy density diet, compared with one high in fat, may allow people to consume a greater quantity of food and avoid feeling deprived (59). Participants are encouraged to continue monitoring their calorie and fat intake.

During months 7−12, participants are encouraged to continue to replace one meal and one snack a day with shakes and bars. (Individuals who elect not to use meal replacements are instructed to use other portion-controlled meal options.) The continued prescription of meal replacements is based on findings from a previous study that persons who adhered to this regimen for 4 years maintained a loss of approximately 8% of initial weight at the end of this time (31,62). These results, and those from a second study (63), were obtained in single-site, open-label trials and require confirmation in RCTs. However, in an 18-month RCT, Jeffery and Wing found that long-term provision of portion-controlled servings of conventional foods significantly improved the maintenance of lost weight, compared with consumption of a self-selected diet with the same calorie target (34). Thus, Look AHEAD decided to prescribe portion-controlled servings, including meal replacements, for the duration of the 4-year intensive intervention.

Activity

The physical activity goal for months 7−12 remains 175 minutes/week of moderately intense activity. Participants who achieve this target are encouraged to exercise ≥ 200 minutes/week (64). All are instructed to strive for 10,000 or more steps a day, as measured by pedometers.

Behavior Modification Curriculum

The curriculum for months 7−12 distinguishes between behaviors required to lose weight and those associated with maintaining a weight loss (24,65). Learning to reverse small weight gains, as they occur, is a critical skill for maintaining a weight loss (13). Sustaining motivation for behavior change is another key focus of this stage, given the decreased rewards (principally weight loss) of treatment (65). To this end, a motivational campaign which focuses on increasing physical activity is introduced early after the transition to bi-monthly group sessions. Other new concepts presented in months 7−12 include coping with dietary lapses, improving body image and self esteem, and expanding exercise options.

Special Treatment Components

Advanced toolbox options

The toolbox provides more intensive weight loss strategies after the first 6 months for participants who have failed to lose 5% of initial weight or have regained 2% or more from their lowest weight (e.g., a loss of 8% declines to 5.5%). Examples of advanced tool box options for such persons include providing prepared, pre-packaged meals for 1 or 2 weeks or paying the cost of cooking classes to help them learn more about food selection and preparation. Individuals who do not meet the study's activity goals might be provided an aerobics video, gym membership, or exercise equipment. Toolbox funds also may be used to reward successful participants who reach and maintain their goals. Advanced toolbox options are only selected after less intensive interventions, suggested by the study's algorithms, have been tried without success. Participants must demonstrate clear evidence of success to continue to receive an advanced option.

Medication

The toolbox also contains weight loss medications (26), which are available for persons who fail during the first 6 months to lose 10% of initial weight. Those who lose less than 5% are encouraged by their lifestyle counselor to try pharmacotherapy, whereas those who lose 5.0 − 9.9% are informed of medication and may receive it upon request. Medication is not offered to individuals who lose ≥ 10% of initial weight and maintain the loss. This is because previous studies found that the addition of medication did not significantly increase weight loss following an initial loss of approximately 10% (66,67). However, given the challenge of maintaining lost weight (68), individuals who regain ≥ 2% from their lowest weight also are offered pharmacotherapy. Participants are not required to use medication if they do not wish. Those who elect to are evaluated by a study physician (or nurse practitioner) to ensure they are free of contraindications to treatment. Participants’ safety and progress are monitored at regular intervals.

At the time of this writing, orlistat is the only weight loss medication prescribed in the study. New agents, however, may be included as they are approved by the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) and by Look AHEAD's pharmacotherapy subcommittee, which conducted an exhaustive review of the safety and efficacy of all FDA-approved medications. Only two agents, orlistat and sibutramine, are currently approved by the FDA for long-term use (26), thus, making them appropriate for Look AHEAD's long duration. Sibutramine is associated, on average, with small increases in diastolic blood pressure (1−2 mm Hg) and pulse (4−5 bpm) that were of concern to Look AHEAD investigators, given the study's goal of decreasing cardiovascular events (26,69-71).

Orlistat is a gastrointestinal lipase inhibitor that induces weight loss by reducing the absorption of dietary fat by approximately 30% (27). Its safety and efficacy have been described elsewhere (72,73). Several RCTs of patients with type 2 diabetes found, at 1 year, that orlistat plus lifestyle modification induced a loss of approximately 4%−6% of initial weight, compared with 2%−4% for placebo plus lifestyle change (74-76). Additional studies showed that the medication improved the maintenance of lost weight, although participants regained weight over time (72,73). Hill et al., for example, found that after losing 8% of initial weight by diet alone, persons who received orlistat regained only 33% of lost weight in the year following treatment, compared with 59% for placebo-treated participants (66). Based on these findings, Look AHEAD investigators concluded that orlistat could be used as an adjunct to the study's behavioral weight-maintenance program but clearly was not a substitute for participants’ continued efforts to increase their physical activity and control their calorie intake. Orlistat may be prescribed up to 4 years, given safety data of this duration (77).

Phase II: Years 2−4

Treatment Frequency and Format

During the second phase of the intervention, which covers years 2−4, participants are no longer required to attend group meetings. Instead, they have two individual contacts per month with their lifestyle counselor to obtain support and monitor their adherence to the weight, diet, and activity goals. One meeting must be face-to-face, while the other can be in person or by phone, mail, or e-mail. RCTs have shown that at least twice-monthly contact, using these modalities, significantly improves the maintenance of lost weight (78-80). This individual format was selected to reduce participant burden but also to provide more flexible scheduling and more opportunities to tailor treatment. Tailoring becomes increasingly important after the first year because participants differ so widely in their progress. Some regain weight, while others continue to lose (24,68). More than two individual contacts per month may be offered to individuals who need additional help. Centers also may continue to offer group sessions, using whatever format they wish, but this is not required.

Diet and Physical Activity Intervention

A weight maintenance schedule of one meal and one snack replacement continues to be recommended from years 2−4, based on data previously reviewed (34,62). Participants who regain large amounts of weight are encouraged to resume the weight-loss-induction protocol (i.e., two meal and one snack replacement a day) to reverse weight gain.

High levels of physical activity continue to be emphasized during this phase (64). The minimum goals remain 175 minutes/week of moderately intense activity and 10,000 steps/day. Participants are encouraged to exceed these goals whenever possible, given the strong relationship between physical activity and long-term weight management observed in previous studies (20,57,64).

Behavior Modification Curriculum

Monthly in-person sessions focus on individualized assessment of progress, review of self-monitoring records, problem solving of difficulties encountered, and goal setting. Sessions reinforce behavioral strategies introduced in the first year and, when appropriate, apply them to the problems of lapse and relapse (68).

Special Treatment Components

Refresher Groups

During years 2−4, centers offer periodic Refresher Groups to help participants reverse weight regain, as well as to achieve (and maintain) the 10% weight loss goal. Attendees meet weekly for 6−8 weeks in groups of 10−20 participants. Refresher Groups are organized around a theme that offers novelty, while reinforcing the basic diet and activity modifications prescribed earlier. Examples include a “Back-to-the Basics Review,” use of a “Perfect Plate” that teaches portion control, and “Mission Possible,” in which participants select a new diet or activity mission each week. Participants have the option of using meal replacements. Refresher Groups are not mandatory, but participants with significant weight regain are strongly encouraged to attend.

National Campaigns

Motivational campaigns also are implemented in Years 2−4 to rejuvenate participants’ commitment to lifestyle change. All participants who have completed the first year are invited to enroll. Campaigns last 8−10 weeks and typically have a kick off meeting (to describe the campaign), a mid-point assessment, and a finale at which the results are announced. Campaigns provide participants specific targets for the 8 weeks, such as losing 5 lb or walking a total of 400,000 steps. The same campaign is conducted at all centers at the same time to enhance study-wide cohesion. The 16 centers, for example, are asked to join forces in a “Let's-Lose-a-Ton-Together” campaign. Centers also may challenge each other in head-to-head competitions. Individual participants who reach the campaign goal are awarded prizes (e.g., windbreakers or stadium blankets). Centers are required to offer a combined total of two or three Refresher Groups and National Campaigns a year (based on a study-wide decision). The efficacy of these interventions has not been assessed by RCTs but both approaches have been used previously (18,29).

Reunion Groups

Centers are encouraged, but not required, to offer two Reunion Groups a year at which participants can renew acquaintances with members of their first-year treatment group. These are primarily social gatherings designed, in part, to facilitate participants’ retention in the study.

Toolbox

Advanced toolbox strategies remain a key method of tailoring treatment to participants’ diverse needs in years 2−4. Individualized assessment at monthly in-person sessions allows identification of barriers to behavior change and weight maintenance. Results of assessment guide the selection of interventions, as do the many algorithms for different clinical problems provided by the toolbox.

Phase III: Year 5 and Beyond

After year 4, participants are encouraged to continue monthly, individual on-site visits with their lifestyle counselor. They may, however, negotiate a reduced schedule of visits (i.e., minimum of two a year) if monthly meetings are not considered feasible (e.g., travel difficulties or poor health) or beneficial. Visits review successes and challenges in maintaining the study's weight and physical activity goals. Lifestyle counselors use cognitive restructuring (24) and motivational interviewing (52) techniques to help participants cope with dietary and activity lapses, as well as weight regain. In addition, participants are encouraged to join the two yearly Refresher Groups (or National Campaigns) that the centers offer. As noted previously, these interventions are designed to help participants reverse weight regain, as well as to renew their commitment to at least 175 minutes a week of physical activity. (Participants, in some cases, may pursue Refresher Groups and National Campaigns on an individual basis with their lifestyle counselor.) Monthly open group meetings are also provided at which participants may weigh-in and obtain new food and activity records.

Treatment Implementation

Numerous steps are taken to ensure that the lifestyle intervention is uniformly implemented across centers, while also attempting to address participant's individual differences and treatment needs. In addition, care was taken to select (and retain) highly motivated participants who could be expected to meet the study's weight and activity goals.

Multidisciplinary Treatment Team

Centers are encouraged to deliver the intervention using a multidisciplinary team that includes a registered dietitian, behavioral psychologist (or other mental health professional), and an exercise specialist. These interventionists are supported by a program coordinator, as well as a physician and diabetes educator (often a nurse).

Management of hypoglycemia

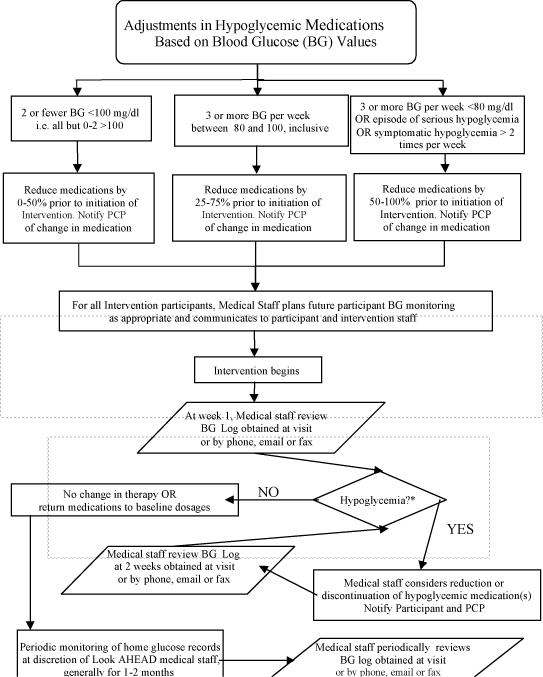

Prevention of hypoglycemic episodes is of particular concern during the first 6 months when participants are prescribed the hypo-caloric meal-replacement plan. Before introducing this diet, medical staff have participants at risk of hypoglycemia (i.e., those taking insulin, sulfonulureas, etc.) monitor their blood sugar daily for at least a week. Based on the readings obtained, diabetes medications are adjusted, following an algorithm (see Figure 2). After beginning the meal replacement, these participants regularly review their blood sugars with medical staff who may adjust medications further. (Only lifestyle participants at risk of hypoglycemic episodes are instructed to monitor their blood sugar. Primary care physicians are expected to instruct other study participants, including those in the DSE group, in monitoring their glucose.)

Figure 2.

The figure presents an algorithm for adjusting the use of medications associated with hypoglycemia. At baseline, medical staff identify all participants in the lifestyle intervention who are prescribed hypoglycemic agents (e.g., insulin, sulfonylurea, repaglinide, and nateglinede) and have them monitor their blood glucose (BG) twice a day for 1 week. Participants are provided with a meter, test strips, and glucose, if needed. BG readings are reviewed with participants at the end of the week, and medications are adjusted, prior to initiating caloric restriction, using the guidelines shown.

Standardizing Treatment Delivery and Tracking Outcomes

The Look AHEAD study follows procedures used in other large-scale RCTs to ensure that the intervention is consistently implemented across centers. Thus, group treatment during the first year is delivered following detailed session-by-session protocols that describe the topics to be covered and the manner in which they are to be addressed. Refresher Groups and National Campaigns are delivered in a similar manner.

Training, certification, and staffing

Each year, lifestyle interventionists from all centers attend a two-day national training to review implementation of the treatment protocol for the coming year. Interventionists’ fidelity in delivering the protocol is certified yearly, based on performance criteria. Each center identifies a senior interventionist who oversees the training of newly hired personnel and is responsible for the continuing annual certification of the site's interventionists. Protocol implementation and participant care are facilitated by each center's holding regular meetings of all treatment staff.

Lifestyle Resource Core

Interventionists are further supported by a Lifestyle Resource Core (LRC) that is led by members of the Lifestyle Intervention subcommittee (which developed the treatment protocol). The LRC organized the 16 centers into four geographic regions, each of which has an LRC team leader. Leaders conduct monthly conference calls to discuss their four centers’ performance, to introduce new treatment materials, and to address questions concerning participant care or protocol implementation.

Tracking System

Feedback on each center's success in meeting the study's weight and activity goals is provided by a centralized Tracking System, managed by the study's coordinating center. Every time participants attend a group or individual visit, their weight and weekly minutes of physical activity (with other data) are recorded in the system. The Tracking System can produce progress reports for individual participants. Additional reports provide monthly summaries of each center's mean weight loss, minutes of activity, and other outcomes. The LRC team has periodic conference calls with each center to review its results of treatment. Centers that are not meeting the study's goals receive further support to identify administrative, personnel, or clinical problems.

Selecting Participants and Tailoring Treatment

Applicants to Look AHEAD were screened extensively to ensure that they met eligibility criteria (i.e., demographic, health status, etc). All applicants also were assessed by the lifestyle intervention team to judge their likelihood of losing weight and increasing physical activity. To this end, all applicants completed a 2-week behavioral run-in period, in which they were asked to record daily both their physical activity and all foods and beverages consumed. Those who did not complete at least 12 of 14 days of record keeping were deemed ineligible because of their low likelihood of completing the extensive self-monitoring required during treatment. In some cases, applicants were allowed to repeat the run-in.

Tailoring treatment to diverse populations

The lifestyle intervention is designed to address the needs of the culturally diverse population that is affected by obesity and type 2 diabetes. As noted previously, 16% of the study's participants are African American, 13% Hispanic American, and 5% Native American/Alaskan native. There is significant cultural diversity even within these groups. For example, cultural, spiritual and socioeconomic factors that influence lifestyle behavior vary among the Navajo, the Pima and other Native American tribes participating in the study (81-83). In an effort to tailor treatment to individuals, interventionists are often chosen from the same ethnic group as that of the participants with whom they will work. This increases the likelihood that they will be better able to discuss cultural beliefs related to diabetes, health, and weight loss, as well as to provide suggestions for adapting ethnic dishes and cooking methods (81-84). The intervention materials are translated into appropriate languages (i.e., Spanish, Navajo) and include the calorie and fat content of various ethnic foods. The toolbox also allows lifestyle counselors to tailor the intervention to the cultural needs of their participants. Thus, although the intervention provides a highly structured, empirically-supported diet and activity protocol, Look AHEAD recognizes that the protocol cannot meet the preferences and needs of all individuals. Interventionists are expected to adapt the protocol, as needed, to help all individuals meet the study's diet and activity goals. Look AHEAD also recognizes that some subsets of participants, including Africans Americans, may have a different weight loss trajectory than that observed in European Americans. The former individuals may lose less weight in the initial stages of treatment but achieve equivalent weight losses over the long term (85-87).

Looking AHEAD

When completed in 2012, the Look AHEAD study will provide the definitive assessment of the health consequences of intentional weight loss, combined with increased physical activity. In the interim, we hope this description of the study's evidence-based lifestyle intervention will assist researchers in planning future trials and practitioners in caring for their obese patients with type 2 diabetes.

Acknowledgements

Writing Group: Thomas A. Wadden (chair), Delia Smith West (co-chair), Linda M. Delahanty (co-chair), John M. Jakicic, W. Jack Rejeski, Robert I. Berkowitz, Donald A. Williamson, David E. Kelley, Shiriki K. Kumanyika, James O. Hill, and Christine M. Tomchee.

We wish to acknowledge the other members of the Look AHEAD Lifestyle Intervention Subcommittee, not included in the writing group, who contributed so generously to the development of the treatment protocol. They include: Nell Armstrong, John Bantle, Paula Bolin, Barbara Cerniauskas, John Foreyt, Edward Gregg, Robert Kuczmarski, Marsha Miller, Connie Mobley, Eva Obarzanek, Amy Otto, Carmen Pal, Rebecca Reeves, Mara Vitolins, Rena Wing, and Susan Yanovski. We also thank Judy Bahnson for her extraordinary contributions to the lifestyle intervention, as we do Mimi Hodges.

Funding and Support

This study is supported by the Department of Health and Human Services through the following cooperative agreements from the National Institutes of Health: DK57136, DK57149, DK56990, DK57177, DK57171, DK57151, DK57182, DK57131, DK57002, DK57078, DK57154, DK57178, DK57219, DK57008, DK57135, and DK56992. The following federal agencies have contributed support: National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases; National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute; National Institute of Nursing Research; National Center on Minority Health and Health Disparities; Office of Research on Women's Health; and the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

Additional support was received from The Johns Hopkins Medical Institutions Bayview General Clinical Research Center (M01-RR-02719); the University of Colorado Health Sciences Center General Clinical Research Center (M01 RR00051) and Clinical Nutrition Research Unit (P30 DK48520); The University of Tennessee at Memphis General Clinical Research Center (M01RR00211-40); the University of Pennsylvania General Clinical Research Center (M01 RR000056 44) and NIH grant (DK 046204); and the University of Washington / VA Puget Sound Health Care System Medical Research Service, Department of Veterans Affairs.

The following organizations have committed to make major contributions to Look AHEAD: Federal Express; Health Management Resources; Johnson & Johnson, LifeScan Inc.; OPTIFASTNovartis Nutrition; Roche Pharmaceuticals; Ross Product Division of Abbott Laboratories; and Slim-Fast Foods Company.

Appendix: Look AHEAD acknowledgements for this paper include

Clinical Sites

The Johns Hopkins Medical Institutions

Frederick Brancati, MD, MHS; Coda Davison, MS; Jeanne Clark, MD, MPH; Jeanne Charleston, RN; Lawrence Cheskin, MD; Kerry Steward, DEd; Richard Rubin, PhD; Kathy Horak, RD

Pennington Biomedical Research Center

George A. Bray, MD; Kristi Rau; Allison Strate, RN; Frank L. Greenway, MD; Donna H. Ryan, MD; Donald Williamson, PhD; Elizabeth Tucker; Brandi Armand, LPN; Mandy Shipp, RD; Kim Landry; Jennifer Perault

The University of Alabama at Birmingham

Cora E. Lewis, MD, MSPH; Sheikilya Thomas MPH; Vicki DiLillo, PhD; Monika Safford, MD; Stephen Glasser, MD; Clara Smith, MPH; Cathy Roche, RN; Charlotte Bragg, MS, RD, LD; Nita Webb, MA; Staci Gilbert, MPH; Amy Dobelstein; L. Christie Oden; Trena Johnsey

Boston Harvard Center

Massachusetts General Hospital: David M. Nathan, MD; Heather Turgeon, RN; Kristina P. Schumann, BA; Enrico Cagliero, MD; Kathryn Hayward, MD; Linda Delahanty, MS, RD; Barbara Steiner, EdM; Valerie Goldman, MS, RD; Ellen Anderson, MS, RD; Laurie Bissett, MS, RD; Alan McNamara, BS; Richard Ginsburg, PhD; Virginia Harlan, MSW; Theresa Michel, MS; Joslin Diabetes Center: Edward S. Horton, MD; Sharon D. Jackson, MS,RD,CDE; Osama Hamdy, MD,PhD; A. Enrique Caballero, MD; Sarah Ledbury, M.Ed, RD; Maureen Malloy, BS; Ann Goebel-Fabbri, PhD; Kerry Ovalle, MS, RCEP, CDE; Sarah Bain,BS; Elizabeth Bovaird, BSN,RN; Lori Lambert, MS, RD;

Beth Israel Deaconess Medical Center: George Blackburn, MD, PhD; Christos Mantzoros, MD, D.Sc; Ann McNamara, RN; Heather McCormick, RD;

University of Colorado Health Sciences Center

James O.Hill, PhD; Marsha Miller, MS, RD; Brent VanDorsten, PhD; Judith Regensteiner, PhD; Robert Schwartz, MD; Richard Hamman, MD, DrPH; Michael McDermott, MD; JoAnn Phillipp, MS; Patrick Reddin, BA; Kristin Wallace, MPH; Paulette Cohrs, RN, BSN; April Hamilton, BS; Salma Benchekroun, BS; Susan Green; Loretta Rome, TRS; Lindsey Munkwitz, BS

Baylor College of Medicine

John P. Foreyt, PhD; Rebecca S. Reeves, DrPH, RD; Henry Pownall, PhD; Peter Jones, MD; Ashok Balasubramanyam, MD

University of California at Los Angeles School of Medicine

Mohammed F. Saad, MD; Ken C. Chiu, MD; Siran Ghazarian, MD; Kati Szamos, RD; Magpuri Perpetua, RD; Michelle Chan, BS; Medhat Botrous

The University of Tennessee Health Science Center

Karen C. Johnson, MD, MPH; Abbas E. Kitabchi, PhD, MD; Helen Lambeth, RN, BSN; Leeann Carmichael, RN; Lynne Lichtermann, RN, BSN

University of Minnesota

Robert W. Jeffery, PhD; Carolyn Thorson, CCRP; John P. Bantle, MD; J. Bruce Redmon, MD; Richard S. Crow, MD; Jeanne Carls, Med; Carolyne Campbell; La Donna James; T. Ockenden, RN; Kerrin Brelje, MPH, RD; M. Patricia Snyder, MA, RD; Amy Keranen, MS; Cara Walcheck, BS, RD; Emily Finch, MA; Birgitta I. Rice, MS, RPh, CHES; Vicki A. Maddy, BS, RD; Tricia Skarphol, BS

St. Luke's Roosevelt Hospital Center

Xavier Pi-Sunyer, MD; Jennifer Patricio, MS; Jennifer Mayer, MS; Stanley Heshka, PhD; Carmen Pal, MD; Mary Anne Holowaty, MS, CN; Diane Hirsch, RNC, MS, CDE;

University of Pennsylvania

Thomas A. Wadden, Ph.D; Barbara J. Maschak-Carey, M.S.N., C.D.E; Gary D. Foster, Ph.D; Robert I. Berkowitz, M.D; Stanley Schwartz, M.D.; Monica Mullen, M.S., R.D; Louise Hesson, M.S.N; Patricia Lipschutz, M.S.N; Anthony Fabricatore, Ph.D; Canice Crerand, Ph.D; Robert Kuehnel, Ph.D; Ray Carvajal, M.S; Renee Davenport; Helen Chomentowski

University of Pittsburgh

David E. Kelley, MD; Jacqueline Wesche -Thobaben, RN,BSN,CDE; Lewis Kuller, MD, Dr.PH.; Andrea Kriska, PhD; Daniel Edmundowicz, MD; Mary L. Klem, PhD,MLIS; Janet Bonk,RN,MPH; Jennifer Rush, MPH; Rebecca Danchenko, BS; Barb Elnyczky; Karen Vujevich, RN-BC,MSN,CRNP; Janet Krulia, RN,BSN,CDE; Donna Wolf,MS; Juliet Mancino, MS,RD,CDE,LDN; Pat Harper,MS,RD,LDN; Anne Mathews, MS,RD,LDN

Brown University

Rena R. Wing, PhD; Vincent Pera, MD; John Jakicic, PhD; Deborah Tate, PhD; Amy Gorin, PhD; Renee Bright, MS; Pamela Coward, MS, RD; Natalie Robinson, MS, RD; Tammy Monk, MS; Kara Gallagher, PhD; Anna Bertorelli, MBA, RD; Maureen Daly, RN; Tatum Charron, BS; Rob Nicholson, PhD; Erin Patterson, BS; Julie Currin, MD; Linda Foss, MPH; Deborah Robles; Barbara Bancroft, RN, MS; Jennifer Gauvin, BS; Deborah Maier, MS; Caitlin Egan, MS; Suzanne Phelan, PhD; Hollie Raynor, PhD, RD; Don Kieffer, PhD; Douglas Raynor, PhD; Lauren Lessard, BS; Kimberley Chula-Maguire, MS; Erica Ferguson, BS, RD; Richard Carey, BS; Jane Tavares, BS; Heather Chenot, MS; JP Massaro, BS

The University of Texas Health Science Center at San Antonio

Steve Haffner, MD; Maria Montez, RN, MSHP, CDE; Connie Mobley, PhD, RD; Carlos Lorenzo, MD

University of Washington / VA Puget Sound Health Care System

Steven E. Kahn, MB, ChB; Brenda Montgomery, RN, BSN, CDE; Robert H. Knopp, MD;Edward W. Lipkin, MD, PhD; Matthew L. Maciejewski, PhD; Dace L. Trence, MD; Roque M. Murillo, BS;S Terry Barrett, BS;

Southwestern American Indian Center, Phoenix, Arizona and Shiprock, New Mexico

William C. Knowler, MD, DrPH; Paula Bolin, RN, MC; Tina Killean; Carol Percy, RN; Rita Donaldson, BSN; Bernadette Todacheenie, EdD; Justin Glass, MD; Sarah Michaels, MD; Jonathan Krakoff, MD; Jeffrey Curtis, MD, MPH; Peter H. Bennett, MB, FRCP; Tina Morgan; Ruby Johnson; Cathy Manus; Janelia Smiley; Sandra Sangster; Shandiin Begay, MPH; Minnie Roanhorse; Didas Fallis, RN; Nancy Scurlock, MSN, ANP; Leigh Shovestull, RD

Coordinating Center

Wake Forest University School of Medicine

Mark A. Espeland, PhD; Judy Bahnson, BA; Lynne Wagenknecht, DrPH; David Reboussin, PhD; W. Jack Rejeski, PhD; Wei Lang, PhD; Alain Bertoni, MD, MPH; Mara Vitolins, DrPH; Gary Miller, PhD; Paul Ribisl, PhD; Kathy Dotson, BA; Amelia Hodges, BA; Patricia Hogan, MS; Carrie Combs, BS; Delia S. West, PhD; William Herman, MD, MPH

Central Resources Centers

DXA Reading Center, University of California at San Francisco

Michael Nevitt, PhD; Ann Schwartz, PhD; John Shepherd, PhD; Jason Maeda, MPH; Cynthia Hayashi; Michaela Rahorst; Lisa Palermo, MS, MA

Central Laboratory, Northwest Lipid Research Laboratories

Santica M. Marcovina, PhD, ScD; Greg Strylewicz, MS

ECG Reading Center, EPICARE, Wake Forest University School of Medicine

Ronald J. Prineas, MD, PhD; Zhu-Ming Zhang, MD; Charles Campbell, AAS, BS; Sharon Hall

Diet Assessment Center, University of South Carolina, Arnold School of Public Health, Center for Research in Nutrition and Health Disparities

Elizabeth J Mayer-Davis, PhD; Cecilia Farach, DrPH

Federal Sponsors

National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases

Barbara Harrison, MS; Susan Z.Yanovski, MD; Van S. Hubbard, MD PhD

National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute

Lawton S. Cooper, MD, MPH; Eva Obarzanek, PhD, MPH, RD; Denise Simons-Morton, MD, PhD

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention

David F. Williamson, PhD; Edward W. Gregg, PhD

References

- 1.The Look AHEAD Research Group Look AHEAD (Action for Health in Diabetes): design and methods for a clinical trial of weight loss for the prevention of cardiovascular disease in type 2 diabetes. Controlled Clinical Trials. 2003;24:610–628. doi: 10.1016/s0197-2456(03)00064-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.The Diabetes Prevention Program Research Group Reduction in the incidence of type 2 diabetes with lifestyle intervention or metformin. N Engl J Med. 2002;346:393–403. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa012512. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Pan XR, Li GW, Hu YH, Wang JX, Yang WY, An ZX, Hu ZX, Lin J, Xiao JZ, Cao HB, Liu PA, Jiang XG, Jiang YY, Wang JP, Zheng H, Zhang H, Bennett PH, Howard BV. Effects of diet and exercise in preventing NIDDM in people with impaired glucose tolerance: the Da Quing IGT and Diabetes Study. Diabetes Care. 1997;20:537–544. doi: 10.2337/diacare.20.4.537. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Tuomilehto JLJ, Eriksson JG, Valle TT, Hamalainin H, Ilanne-Parikka P, Keinanen-Kiukaanniemi S, Laakso M, Louheranta A, Rastas M, Salminen V, Uusitupa M. Prevention of type 2 diabetes mellitus by changes in lifestyle among subjects with impaired glucose tolerance. N Engl J Med. 2001;344:1343–1392. doi: 10.1056/NEJM200105033441801. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Guare JC, Wing RR, Grant A. Comparison of obese NIDDM and nondiabetic women: short- and long-term weight loss. Obes Res. 1995;3:329–335. doi: 10.1002/j.1550-8528.1995.tb00158.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Pascale RW, Wing RR, Butler BA, Mullen M, Bononi P. Effects of a behavioral weight loss program stressing calorie restrictions versus calorie plus fat restriction in obese individuals with NIDDM or a family history of diabetes. Diabetes Care. 1995;18:1241–1248. doi: 10.2337/diacare.18.9.1241. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Wing RR, Marcus MD, Salata R, Epstein LH, Miaskiewicz S, Blair EH. Effects of a very-low-calorie diet on long-term glycemic control in obese type 2 diabetic subjects. Arch Intern Med. 1991;151:1334–1340. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Wing RR, Blair E, Marcus M, Epstein LH, Harvey J. Year-long weight loss treatment for obese patients with type II diabetes: does including and intermittent very-low-calorie diet improve outcome? Amer J Med. 1994;97:354–362. doi: 10.1016/0002-9343(94)90302-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Wing RR, Epstein LH, Paternostro-Bayles M, Kriska A, Nowalk MP, Gooding W. Exercise in a behavioural weight control programme for obese patients with type 2 (non-insulin-dependent) diabetes. Diabetologia. 1988;31:902–909. doi: 10.1007/BF00265375. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Wing RR, Koeske R, Epstein LH, Nowalk MP, Gooding W, Becker D. Long-term effects of modest weight loss type II diabetic patients. Arch Int Med. 1987;147:1749–1753. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Stevens VJ, Corrigan SA, Obarzanek E, Bernauer E, Cook NR, Hebert P, Mattfeldt-Beman M, Oberman A, Sugars C, Dalcin AT. Weight loss intervention in phase 1 of the trials of hypertension prevention. Arch Intern Med. 1993;153:849–858. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Dattilo AM, Kris-Etherton PM. Effects of weight reduction on blood lipids and lipoproteins: a meta-analysis. Am J Clin Nutr. 1992;56:320–328. doi: 10.1093/ajcn/56.2.320. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Wadden TA, Foster GD, Letizia KA. One-year behavioral treatment of obesity: comparison of moderate and severe caloric restriction and the effects of weight maintenance therapy. J Consult Clin Psychol. 1994;62:165–171. doi: 10.1037//0022-006x.62.1.165. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Torgerson JS, Lissner L, Lindroos AK, Kruijer H, Sjostrom L. VLCD plus dietary and behavioral support versus support alone in the treatment of severe obesity: A randomised two-year clinical trial. Int J Obes. 1997;21:987–994. doi: 10.1038/sj.ijo.0800507. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Wadden TA, Bartlett SJ, Foster GD, Greensetin RA, Wingate BJ, Stunkard AJ, Letizia KA. Sertraline and relapse prevention training following treatment by very-low-calorie diet: A controlled clinical trial. Obes Res. 1995;3:549–557. doi: 10.1002/j.1550-8528.1995.tb00189.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Sikand G, Kondo A, Foreyt JP, Jones PH, Gotto AM., Jr. Two-year follow-up of patients treated with a very-low-calorie diet and exercise training. J Am Diet Assoc. 1988;88:487–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Pate RR, Pratt M, Blair SN, Haskell WL, Macera CA, Bouchard C, Buchner D, Ettinger W, Heath GW, King AC. Physical activity and public health: a recommendation from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention and the American College of Sports Medicine. JAMA. 1995;273:402–407. doi: 10.1001/jama.273.5.402. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.The Diabetes Prevention Program Research Group The Diabetes Prevention Program (DPP). Description of lifestyle intervention. Diabetes Care. 2002;25:2165–2171. doi: 10.2337/diacare.25.12.2165. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Jakicic JM, Wing RR, Winters C, Lang W. Intermittent exercise and home-exercise equipment: effects on long-term adherence, weight loss, and fitness. A randomized trial. JAMA. 1999;282:1554–1560. doi: 10.1001/jama.282.16.1554. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Jeffery RW, Wing RR, Sherwood NE, Tate DF. Physical activity and weight loss: does prescribing higher physical activity goals improve outcome? Am J Clin Nutr. 2003;78:684–689. doi: 10.1093/ajcn/78.4.684. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Lee CD, Blair SN, Jackson AS. Cardiorespiratory fitness, body composition, and all-cause and cardiovascular disease mortality in men. Am J Clin Nutr. 1999;69:373–380. doi: 10.1093/ajcn/69.3.373. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Hu FB, Willett WC, Li T, Stampfer MJ, Colditz GA, Manson JE. Adiposity as compared with physical activity in predicting mortality among women. N Engl J Med. 2004;351:2694–703. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa042135. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Dietary Guidelines for Americans. 2005. U.S. Department of Agriculture, U.S. Department of Health and Human Services

- 24.Wadden TA, Butryn ML, Byrne KJ. Efficacy of lifestyle modification for long-term weight control. Obes Res. 2004;12:151S–161S. doi: 10.1038/oby.2004.282. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Perri MG, Nezu AM, Patti ET, McCann KL. Effect of length of treatment on weight loss. J Consult Clin Psychol. 1989;57:450–454. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Yanovski SZ, Yanovski JA. Obesity. N Engl J Med. 2002;346:591–602. doi: 10.1056/NEJMra012586. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Buchwald H, Avidor Y, Braunwald E, Jensen MD, Pories W, Fahrbach K, Schoelles K. Bariatric surgery: a systematic review and meta-analysis. JAMA. 2004;292:1724–37. doi: 10.1001/jama.292.14.1724. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Renjilian DA, Perri MG, Nezu AM, McKelvey WF, Shermer RL, Anton SD. Individual vs. group therapy for obesity: Effects of matching participants to their treatment preference. J Consult Clin Psychol. 2001;69:717–721. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Wing RR, Venditti E, Jakicic JM, Polley BA, Lang W. Lifestyle intervention in overweight individuals with a family history of diabetes. Diabetes Care. 1998;21:350–9. doi: 10.2337/diacare.21.3.350. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Whelton PK, Appel LJ, Espeland MA, Applegate WB, Ettinger WHJ, Kostis JB, Kumanyika S, Lacy CR, Johnson KC, Folmar S, Cutler JA. Sodium reduction and weight loss in the treatment of hypertension in older persons: a randomized controlled trial of nonpharmacologic interventions in the elderly (TONE). JAMA. 1998;279:839–846. doi: 10.1001/jama.279.11.839. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Ditschuneit HH, Flechtner-Mors M, Johnson TD, Adler G. Metabolic and weight loss effects of long-term dietary intervention in obese subjects. Am J Clin Nutr. 1999;69:198–204. doi: 10.1093/ajcn/69.2.198. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Heymsfield SB, van Mierlo CA, van der Knaap HC, Heo M, Frier HI. Weight management using a meal replacement strategy: Meta and pooling analysis from six studies. Int J Obes. 2003;27:537–549. doi: 10.1038/sj.ijo.0802258. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Lichtman SW, Pisarska K, Berman ER, Pestone M, Dowling H, Offenbacher E, Weisel H, Heshka S, Matthews DE, Heymsfield SB. Discrepancy between self-reported and actual caloric intake and exercise in obese subjects. N Engl J Med. 1992;327:1893–1898. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199212313272701. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Jeffery RW, Wing RR, Thorson C, Burton LR, Raether C, Harvey J, Mullen M. Strengthening behavioral interventions for weight loss: A randomized trial of food provision and monetary incentives. J Consult Clin Psychol. 1993;61:1038–1045. doi: 10.1037//0022-006x.61.6.1038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Metz JA, Stern JS, Kris-Etherton P, Reusser ME, Morris CD, Hatton D, Oparil S, Haynes RB, Resnick LM, Pi-Sunyer FX, Clark S, Chester L, McMahon M, Snyder GW, McCarron DA. A randomized trial of improved weight loss with a prepared meal plan in overweight and obese patients: impact of cardiovascular risk reduction. Arch Intern Med. 2000;160:2150–8. doi: 10.1001/archinte.160.14.2150. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Haynes RB, Kris-Etherton P, McCarron DA, Oparil S, Chait A, Resnick LM, Morris CD, Clark S, Hatton DC, Metz JA, McMahon M, Holcomb S, Snyder GW, Pi-Sunyer FX, Stern JS. Nutritionally complete prepared meal plan to reduce cardiovascular risk factors: a randomized clinical trial. J Am Diet Assoc. 1999;99:1077–83. doi: 10.1016/S0002-8223(99)00257-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Wing RR, Jeffery RW, Burton LR, Thorson C, Nissinoff KS, Baxter JE. Food provision vs. structured meal plans in the behavioral treatment of obesity. Int J Obes. 1996;20:56–62. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Yip I, Go VL, DeShields S, Saltsman P, Bellman M, Thames G, Murray S, Wang HJ, Elashoff R, Heber D. Liquid meal replacements and glycemic control in obese type 2 diabetes patients. Obes Res. 2001;4:341S–347S. doi: 10.1038/oby.2001.140. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Wing RR, Blair EH, Bononi P, Marcus MD, Watanabe R, Bergman RN. Caloric restriction per se is a significant factor in improvements in glycemic control and insulin sensitivity during weight loss in obese NIDDM. Diabetes Care. 1994;17:30–36. doi: 10.2337/diacare.17.1.30. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Williams KV, Mullen ML, Kelley DE, Wing RR. The effect of short periods of caloric restriction on weight loss and glycemic control in type 2 diabetes. Diabetes Care. 1998;21:2–8. doi: 10.2337/diacare.21.1.2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Jakicic JM, Wing RR, Butler BA, Robertson RJ. Prescribing exercise in multiple short bouts versus one continuous bout: effects on adherence, cardiorespiratory fitness, and weight loss in overweight women. Int J Obes. 1995;19:893–901. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Andersen RE, Wadden TA, Bartlett SJ, Zemel B, Verde TJ, Franckowiak SC. Effects of lifestyle activity vs structured aerobic exercise in obese women. JAMA. 1999;281:335–340. doi: 10.1001/jama.281.4.335. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Epstein LH, Wing RR, Koeske R, Ossip D, Beck S. A comparison of lifestyle change and programmed aerobic exercise on weight and fitness change in obese children. Behav Ther. 1985;13:651–665. [Google Scholar]

- 44.Dunn AL, Marcus BH, Kampert JB, Garcia ME, Kohl III HW, Blair SN. Comparison of lifestyle and structured interventions to increase physical activity and cardiorespiratory fitness. JAMA. 1999;281:327–334. doi: 10.1001/jama.281.4.327. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Yamanouchi K, Shinozaki T, Chikada K, Nishikawa T, Ito K, Shimizu S, Ozawa N, Suzuki Y, Maeno H, Kato K. Daily walking combined with diet therapy is a useful means for obese NIDDM patients not only to reduce body weight but also to improve insulin sensitivity. Diabetes Care. 1995;18:775–778. doi: 10.2337/diacare.18.6.775. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.King AC, Haskell WL, Young DR, Oka RK, Stefanick ML. Long-term effects of varying intensities and formats of physical activity on participation rates, fitness, and lipoproteins in men and women aged 50 to 65 years. Circulation. 1995;91:2596–604. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.91.10.2596. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Perri MG, Martin AD, Leermakers EA, Sears SF, Notelovitz M. Effects of group- versus home-based exercise in the treatment of obesity. J Consult Clin Psychol. 1997;65:278–285. doi: 10.1037//0022-006x.65.2.278. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Wadden TA, Berkowitz RI, Womble LG, Sarwer DB, Phelan S, Cato RK, Hesson LA, Osei SY, Kaplan R, Stunkard AJ. Randomized trial of lifestyle modification and pharmacotherapy for obesity. N Engl J Med. 2005;353:2111–2120. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa050156. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Baker RC, Kirschenbaum DS. Weight control during the holidays: highly consistent self-monitoring as a potentially useful coping mechanism. Health Psychol. 1998;17:367–370. doi: 10.1037//0278-6133.17.4.367. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Berkowitz RI, Wadden TA, Tershakovec AM, Cronquist JL. Behavior therapy and sibutramine for treatment of adolescent obesity. JAMA. 2003;289:1805–1812. doi: 10.1001/jama.289.14.1805. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.O'Neil PM, Brown JD. Weighing the evidence: benefits of regular weight monitoring for weight control. J Nutr Educ Behav. 2005;37:319–322. doi: 10.1016/s1499-4046(06)60163-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Smith DE, Heckemeyer CM, Kratt PP, Mason DA. Motivational interviewing to improve adherence to a behavioral weight-control program for older obese women with NIDDM. A pilot study. Diabetes Care. 1997;20:52–54. doi: 10.2337/diacare.20.1.52. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Perri MG, Nezu AM, McKelvey WF, Shermer RL, Renjilian DA, Viegener BJ. Relapse prevention training and problem-solving therapy in the long-term management of obesity. J Consult Clin Psychol. 2001;69:722–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Smith D, Wing R. Diminished weight loss and behavioral compliance using repeated diets in obese women with type II diabetes. Health Psychol. 1991;10:378–383. doi: 10.1037//0278-6133.10.6.378. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Perri MG, McAllister D, Gange J, Jordan R, McAdoo W, Nezu A. Effects of four maintenance programs on the long-term management of obesity. J Consult Clin Psychol. 1988;56:529–534. doi: 10.1037//0022-006x.56.4.529. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Perri MG, McAdoo WG, McAllister DA, Lauer JB, Jordan RC, Yancey DZ, Nezu AM. Effects of peer support and therapist contact on long-term weight loss. J Consult Clin Psychol. 1987;55:615–617. doi: 10.1037/0022-006X.55.4.615. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.McGuire M, Wing RR, Klem M, Hill J. Behavioral strategies of individuals who have maintained long-term weight losses. Obes Res. 1999;7:334–341. doi: 10.1002/j.1550-8528.1999.tb00416.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Lowe M. Self-regulation of energy intake in the prevention and treatment of obesity: is it feasible? Obes Res. 2003;11:44S–59S. doi: 10.1038/oby.2003.223. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Rolls B, Barnett R. Volumetrics: Feel full on fewer calories. Harper Collins Publishers; New York: 2000. [Google Scholar]

- 60.Bell EA, Rolls BJ. Energy density of foods affects energy intake across multiple levels of fat content in lean and obese women. Am J Clin Nutr. 2001;73:1010–8. doi: 10.1093/ajcn/73.6.1010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Rolls BJ, Bell EA. Dietary approaches to the treatment of obesity. Med Clin North Am. 2000;84:401–18. doi: 10.1016/s0025-7125(05)70228-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Flechtner-Mors M, Ditschuneit H, Johnson T, Suchard M, Adler G. Metabolic and weight loss effects of long-term dietary intervention in obese patients. Obes Res. 2000;8:399–402. doi: 10.1038/oby.2000.48. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Rothacker D. Five-year self-management of weight using meal replacements: comparison with matched controls in rural Wisconsin. Nutrition. 2000;16:344–348. doi: 10.1016/s0899-9007(99)00280-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Jakicic JM, Marcus B, Gallagher K, Napolitano M, Lang W. Effect of exercise duration and intensity on weight loss in overweight, sedentary women: a randomized trial. JAMA. 2003;290:1323–1330. doi: 10.1001/jama.290.10.1323. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Rothman A. Toward a theory-based analysis of behavioral maintenance. Health Psychol. 2000;19(1 Suppl):64–69. doi: 10.1037/0278-6133.19.suppl1.64. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Hill JO, Hauptman J, Anderson JW, Fujioka K, O'Neil PM, Smith DK, Zavoral JH, Aronne LJ. Orlistat, a lipase inhibitor, for weight maintenance after conventional dieting: a 1-y study. Am J Clin Nutr. 1999;69:1109–1116. doi: 10.1093/ajcn/69.6.1108. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Wadden TA, Berkowitz RI, Womble L, Sarwer D, Arnold M, Steinberg C. Effects of sibutramine plus orlistat in obese women following 1 year treatment by sibutramine alone: a placebo-controlled trial. Obes Res. 2000;8:431–437. doi: 10.1038/oby.2000.53. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Jeffery R, Drewnowski A, Epstein L, Stunkard A, Wilson G, Wing R. Long-term maintenance of weight loss: current status. Health Psychol. 2000;19(1 Suppl):5–16. doi: 10.1037/0278-6133.19.suppl1.5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Bray GA, Blackburn GL, Ferguson JM, Greenway FL, Jain AK, Mendel CM, Mendels J, Ryan DH, Schwartz SL, Scheinbaum ML, Seaton TB. Sibutramine produces dose-related weight loss. Obes Res. 1999;7:189–198. doi: 10.1002/j.1550-8528.1999.tb00701.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Arterburn DE, Crane PK, Veenstra DL. The efficacy and safety of sibutramine for weight loss: a systematic review. Arch Int Med. 2004;164:994–1003. doi: 10.1001/archinte.164.9.994. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Kim SH, Lee YM, Jee SH, Nam CM. Effect of sibutramine on weight loss and blood pressure: a meta-analysis of controlled trials. Obes Res. 2003;11:1116–1123. doi: 10.1038/oby.2003.152. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Davidson M, Hauptman J, DiGirolamo M, Foreyt J, Halsted C, Heber D. Weight control and risk factor reduction in obese subjects treated for 2 years with orlistat: a randomized controlled trial. JAMA. 1999;281:235–242. doi: 10.1001/jama.281.3.235. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Sjostrom L, Rissanen A, Andersen T, Boldrin M, Golay A, Koppeschaar H, Krempf M, European Multicenter Orlistat Study Group Randomized placebo-controlled trial of orlistat for weight loss and prevention of weight regain in obese patients. Lancet. 1998;352:167–172. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(97)11509-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Hollander PA, Elbein SC, Hirsch IB, Kelley D, McGill J, Taylor T, Weiss SR, Crockett SE, Kaplan RA, Comstock J, Lucas CP, Lodewick PA, Canovatchel W, Chung J, Hauptman J. Role of orlistat in the treatment of obese patients with type 2 diabetes. Diabetes Care. 1998;21:1288–94. doi: 10.2337/diacare.21.8.1288. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Miles JM, Leiter L, Hollander P, Wadden TA, Anderson JW, Doyle M, Foreyt J, Aronne L, Klein S. Effect of orlistat in overweight and obese patients with type 2 diabetes treated with metformin. Diabetes Care. 2002;25:1123–8. doi: 10.2337/diacare.25.7.1123. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Kelley DE, Bray GA, Pi-Sunyer FX, Klein S, Hill J, Miles J, Hollander P. Clinical efficacy of orlistat therapy in overweight and obese patients with insulin-treated type 2 diabetes: a 1-year randomized controlled trial. Diabetes Care. 2002;25:1033–41. doi: 10.2337/diacare.25.6.1033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Torgerson JS, Hauptman J, Boldrin MN, Sjostrom L. Xenical in the prevention of diabetes in obese subjects (XENDOS) study: a randomized study of orlistat as an adjunct to lifestyle changes for the prevention of type 2 diabetes in obese patients. Diabetes Care. 2004;27:155–61. doi: 10.2337/diacare.27.1.155. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Perri MG, Shapiro RM, Ludwig WW, Twentyman CT, McAdoo WG. Maintenance strategies for the treatment of obesity: An evaluation of relapse prevention training and posttreatment contact by mail and telephone. J Consult Clin Psychol. 1984;52:404–413. doi: 10.1037//0022-006x.52.3.404. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Perri MG, McAdoo WG, McAllister DA, Lauer JB, Yancey DZ. Enhancing the efficacy of behavior therapy for obesity: effects of aerobic exercise and a multicomponent maintenance program. J Consult Clin Psychol. 1986;54:670–5. doi: 10.1037//0022-006x.54.5.670. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Tate DF, Jackvony EH, Wing RR. Effects of internet behavioral counseling on weight loss in adults at risk for type 2 diabetes: a randomized trial. JAMA. 2003;289:1833–6. doi: 10.1001/jama.289.14.1833. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Roubideaux YD, Moore K, Avery C, Muneta B, Knight M, Buchwald D. Diabetes education materials: recommendations of tribal leaders, Indian health professionals, and American Indian community members. Diabetes Educ. 2000;26:290–4. doi: 10.1177/014572170002600209. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Thompson JL, Wolfe VK, Wilson N, Pardilla MN, Perez G. Personal, social, and environmental correlates of physical activity in Native American women. Am J Prev Med. 2003;25:53–60. doi: 10.1016/s0749-3797(03)00165-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Griffin JA, Gilliland SS, Perez G, Upson D, Carter JS. Challenges to participating in a lifestyle intervention program: the Native American Diabetes Project. Diabetes Educ. 2000;26:681–9. doi: 10.1177/014572170002600416. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Delahanty LM, Begay SR, Coocyate N, Hoskin M, Isonaga M, Levy E, Szamos K, Ka"iulani Odom S, Mikami K. The effectiveness of lifestyle intervention in the Diabetes Prevention Program (DPP): application in diverse ethnic groups. In: Mayer-Davis E, editor. Diabetes Prevention. Vol. 23. American Dietetic Association; 2002. pp. 30–36. [Google Scholar]

- 85.Kumanyika SK, Espeland MA, Bahnson JL, Bottom JB, Chartleston JB, Folmar S, Wilson AC, Whelton PK. Ethnic comparison of weight loss in the trial of nonpharmacologic interventions in the elderly. Obes Res. 2002;10:96–106. doi: 10.1038/oby.2002.16. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Wing RR, Hamman RF, Bray GA, Delahanty L, Edelstein SL, Hill JO, Horton ES, Hoskin MA, Kriska A, Lachin J, Mayer-Davis EJ, Pi-Sunyer FX, Regensteiner JG, Venditti B, Wylie-Rosett J, the Diabetes Prevention Program Research Group Achieving weight and activity goals among diabetes prevention program lifestyle participants. Obes Res. 2004;12:1426–34. doi: 10.1038/oby.2004.179. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Kumanyika SK. Obesity treatment in minorities. In: Wadden TA, Stunkard AJ, editors. Handbook of obesity treatment. Guildford Press; New York: 2002. pp. 416–446. [Google Scholar]