Summary

Vascular endothelial growth factor A (VEGFA; hereafter referred to as VEGF) is a key regulator of physiological and pathological angiogenesis. Two families of VEGF isoforms are generated by alternate splice-site selection in the terminal exon. Proximal splice-site selection (PSS) in exon 8 results in pro-angiogenic VEGFxxx isoforms (xxx is the number of amino acids), whereas distal splice-site selection (DSS) results in anti-angiogenic VEGFxxxb isoforms. To investigate control of PSS and DSS, we investigated the regulation of isoform expression by extracellular growth factor administration and intracellular splicing factors. In primary epithelial cells VEGFxxxb formed the majority of VEGF isoforms (74%). IGF1, and TNFα treatment favoured PSS (increasing VEGFxxx) whereas TGFβ1 favoured DSS, increasing VEGFxxxb levels. TGFβ1 induced DSS selection was prevented by inhibition of p38 MAPK and the Clk/sty (CDC-like kinase, CLK1) splicing factor kinase family, but not ERK1/2. Clk phosphorylates SR protein splicing factors ASF/SF2, SRp40 and SRp55. To determine whether SR splicing factors alter VEGF splicing, they were overexpressed in epithelial cells, and VEGF isoform production assessed. ASF/SF2, and SRp40 both favoured PSS, whereas SRp55 upregulated VEGFxxxb (DSS) isoforms relative to VEGFxxx. SRp55 knockdown reduced expression of VEGF165b. Moreover, SRp55 bound to a 35 nucleotide region of the 3′UTR immediately downstream of the stop codon in exon 8b. These results identify regulation of splicing by growth and splice factors as a key event in determining the relative pro- versus anti-angiogenic expression of VEGF isoforms, and suggest that p38 MAPK-Clk/sty kinases are responsible for the TGFβ1-induced DSS selection, and identify SRp55 as a key regulatory splice factor.

Keywords: VEGF, VEGF165b, splicing, VEGFxxxb, SRp55, TGFβ1, IGF1, Clk1/sty (CLK1), CLK4

Introduction

The growth of new blood vessels is a fundamental requirement for survival of new tissue in embryonic development, and in the mature adult, new vessel formation is required for wound healing, placental development, cyclical changes within the endometrium, muscle growth, and fat deposition (Folkman, 1985). However, angiogenesis is also the underlying pathological process in all the major diseases of the developed world. It is a prominent feature of cancer, vascular disease - atheromatous plaque development requires proliferation of the vaso vasorum (Celletti et al., 2001), diabetes, rheumatoid arthritis and proliferative retinopathy (Ferrara and Davis-Smyth, 1997).

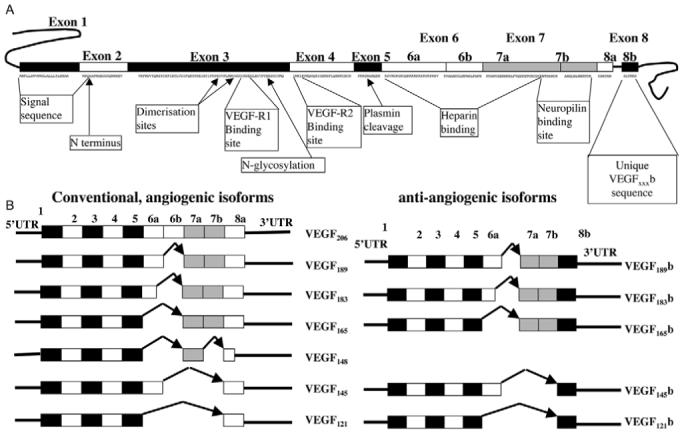

The formation of new vessels is a complex process involving over 50 interdependent growth factors, receptors, cytokines and enzymes (Carmeliet, 2000), many from the vascular endothelial growth factor A (VEGFA; hereafter referred to as VEGF), angiopoietin and ephrin families. Although complex, VEGF signalling often represents a crucial rate-limiting step in angiogenesis and is therefore the focus of intense investigation. However, there are at least 12 splice isoforms of VEGF (Fig. 1), some with pro-angiogenic and some with anti-angiogenic properties (Perrin et al., 2005). In contrast to the well-described regulation of VEGF transcription, however, almost nothing is known about the regulation of splicing. Of the more than 24,000 manuscripts published on VEGF, only a few have investigated the regulation of splicing (Cohen et al., 2005; Dowhan et al., 2005; Li et al., 2004).

Fig. 1.

Exonic structure of the VEGF gene and identified splice variants of VEGF-A. (A) Full-length VEGF gene with two alternative exon 8 splice sites. (B) Two families of VEGF isoforms, VEGFxxx and VEGFxxxb.

VEGF pre-mRNA is differentially spliced from eight exons to form mRNAs encoding at least six proteins (Neufeld et al., 1999) that have been widely studied and accepted as pro-angiogenic pro-permeability vasodilators. The dominant form is generally considered to be VEGF165, which has 165 amino acids in the final structure. In 2002, an alternative isoform, VEGF165b, was identified (Bates et al., 2002), generated by differential splice-acceptor-site selection in the 3′UTR within exon 8 of the VEGF gene (Fig. 1B), thus resulting in two sub-exons, termed exon 8a and exon 8b, in keeping with the nomenclature for exon 6 (Houck et al., 1991). Distal splicing into the splice acceptor site for exon 8b results in an open-reading frame of 18 bases. The open-reading frames of exons 8a and 8b both code for six amino acids; exon 8a for Cys-Asp-Lys-Pro-Arg-Arg and exon 8b for Ser-Leu-Thr-Arg-Lys-Asp. This alternative splicing predicted an alternate family of VEGF isoforms (complementary to the existing isoforms) expressed as multiple proteins in human cells and tissues, of which VEGF121b, VEGF165b, VEGF145b and VEGF189b have now been identified (Perrin et al., 2005). The family has been termed VEGFxxxb, where xxx is the amino acid number. This alternate C-terminus enables VEGF165b to inhibit VEGF165-induced endothelial proliferation, migration, vasodilatation (Bates et al., 2002), and in vivo experimental and physiological angiogenesis and tumour growth (Cebe Suarez et al., 2006; Qiu et al., 2007; Woolard et al., 2004). These effects were shown to be specific for VEGF, because VEGF165b does not affect fibroblast growth factor (FGF)-induced endothelial cell proliferation (Bates et al., 2002). Moreover, unlike other VEGF isoforms, VEGF165b is downregulated in cancers investigated so far, including renal-cell (Bates et al., 2002), prostate (Woolard et al., 2004) and colon carcinoma (Varey et al., 2008) and malignant melanoma (Pritchard-Jones et al., 2007). Furthermore, the expression of VEGF splice variants is altered in angiogenic microvascular phenotypes of proliferative eye disease and pre-eclampsia (Bates et al., 2006; Perrin et al., 2005). The receptor-binding domains are still present in VEGF165b and, hence it acts as a competitive inhibitor of VEGF165, it binds to the receptor but does not stimulate the full tyrosine phosphorylation of the VEGFR activated by VEGF165 (Woolard et al., 2004; Cebe Suarez et al., 2006). This isoform therefore appears to be an endogenous anti-angiogenic agent formed by alternative splicing and, as such, inhibits angiogenesis-dependent conditions, such as tumour growth (Rennel et al., 2008a; Varey et al., 2008) and proliferative retinopathy (Konopatskaya et al., 2006). Recent studies have shown that this family of isoforms forms a substantial proportion of the total VEGF (Perrin et al., 2005), ranging from 1% in placental tissues (Bates et al., 2006) to over 95% in normal colon tissue (Varey et al., 2008).

Alternative splicing is a mechanism of differential gene expression that allows the selection of alternate splice sites, inclusion or exclusion of specific exons or intron retention resulting in the production of structurally and functionally distinct proteins from a single coding sequence (Kalnina et al., 2005; Smith, 2005). It is widely accepted that alternative splicing of VEGF, which results in the conventional pro-angiogenic family, is fundamental to the regulation of its bioavailability; the inclusion and exclusion of exons 6 and 7, which contain the heparin-binding domains, affect the generation of diffusible proteins (Houck et al., 1991). Moreover, VEGF gene expression is transcriptionally regulated by a diversity of factors including hypoxia (Shweiki et al., 1992), growth factors and cytokines (Goad et al., 1996) (Kotsuji-Maruyama et al., 2002) (Patterson et al., 1996) (Asano-Kato et al., 2005), hormones (Sone et al., 1996) (Charnock-Jones et al., 2000), oncogenes and tumour suppressor genes (Rak et al., 1995) (Mukhopadhyay et al., 1995). Despite evidence that there is a switch between pro- and anti-angiogenic VEGF isoforms in a variety of disease states (Bates et al., 2002; Bates et al., 2006; Perrin et al., 2005; Schumacher et al., 2007; Woolard et al., 2004), little is known about the molecular and cellular pathways that regulate alternative splicing of VEGF pre-mRNA in general and of the exon 8a/8b alternative 3′ splice site in particular.

The present study aimed to determine the role of environmental stimuli in the alternative splicing event that cause this angiogenic switch between pro- and anti-angiogenic isoforms of VEGF. Growth factors, such as insulin-like growth factor 1 (IGF1) and transforming growth factor β1 (TGFβ1) have previously been shown to increase total VEGF expression (Finkenzeller et al., 1997; Goad et al., 1996; Li et al., 1995; Pertovaara et al., 1994), but their effects on terminal exon splice-site selection are unknown. It is clear, however, that signal transduction pathways initiated by growth factors can influence alternative splicing (Blaustein et al., 2005). We have therefore addressed the hypothesis that growth factors (e.g. IGF1, TNFα, TGFβ1) differentially affect expression of the VEGFxxx and VEGFxxxb isoform families.

Pre-mRNA splicing occurs during transcription (Misteli et al., 1997) mediated by the spliceosome (Caceres and Kornblihtt, 2002). Splicing is regulated, however, by splicing regulatory factors (SRFs). These include the SR proteins (e.g. 9G8, ASF/SF2, SRp40, SRp55, among others) that regulate binding to exon-splicing enhancers and silencers (ESEs and ESSs, respectively) and intronic enhancers and silencers (ISE and ISS) in the pre-mRNA (Caceres and Kornblihtt, 2002). General mechanisms of splicing can be regulated genetically: base sequences in the transcript influence splice-factor affinities (Matlin et al., 2005), and promoters can also influence alternative splicing through the selective recruitment of splice factors to the C-terminal domain of RNA polymerase II (Kornblihtt, 2005). A sequence mutation in tumours could theoretically result in altered splicing, but as splicing from VEGF165 to VEGF165b has previously been demonstrated upon differentiation of glomerular epithelial cells (Cui et al., 2004), this splicing is unlikely to be mutation dependent.

Pre-mRNA has intronic and exonic sequences that bind SRF enhancers and silencers (Hertel et al., 1997). Exon splicing depends upon the balance of SR protein activities. These include ASF/SF2 and SRp40, which have previously been shown to favour proximal splice-site selection in other pre-mRNAs, SRp55 and 9G8. Neither binding of these splicing factors to VEGF pre-mRNA nor their interaction with VEGF pre-mRNA sequences have been investigated, but they have been implicated in growth-factor-mediated alternate splice-site selection (Blaustein et al., 2005). Of all splicing factors, the distribution of these consensus sequences led us to investigate the potential role of SRp40, ASF/SF2, SRp55 and 9G8 (the latter as a factor in which no consensus sequences were present) in VEGF terminal-exon splicing. We therefore addressed the hypothesis that known splicing factors (SRp40, ASF/SF2, SRp55, 9G8) would also differentially affect expression of the VEGFxxx and VEGFxxxb isoform families.

VEGFxxxb isoforms are rarely expressed in transformed cell lines. Therefore, we have used two cell types that constitutively produce both VEGFxxx and VEGFxxxb isoforms (Cui et al., 2004). We show here that retinal pigmented epithelial (RPE) cells express more VEGF165b than VEGF165, whereas human proliferating conditionally immortalised podocytes (PCIP) express predominantly VEGF165 (Cui et al., 2004). We have used these two cell types to investigate the downregulation of VEGF165b (RPE cells) and upregulation of VEGF165b (podocytes) by growth factors.

Results

Retinal pigmented epithelial cells express both VEGFxxx and VEGFxxxb

RPE cell supernatant was collected after 72 hours incubation in serum-free medium. VEGFxxxb and VEGFtotal concentrations in the supernatant were detected by ELISA. RPE cells from four different primary human donors expressed 87±28 pg/ml (mean ± s.e.m.) of VEGFxxxb in the supernatant, and 117±60 pg/ml of VEGF, demonstrating that, on average, 74% of the total VEGF was the VEGFxxxb isoform.

IGF1 and TNFα switch splicing from anti-angiogenic to pro-angiogenic VEGF isoforms

Growth factors such as IGF1, TNFα and TGFβ1 have previously been shown to increase total VEGF expression (Finkenzeller et al., 1997; Goad et al., 1996; Li et al., 1995; Pertovaara et al., 1994), but their effect on terminal exon splice-site selection is not known. In both epithelial cell types tested, RPE cells and podocytes, treatment with IGF1 significantly upregulated total VEGF expression, but this upregulation was confined to the pro-angiogenic, VEGFxxx, isoforms (Fig. 2). In RPE cell lysate, IGF1 resulted in a dose dependent increase in VEGFtotal from 217±112 pg/mg total protein to 1656±527 pg/mg protein at 100 nM IGF1 (n=6, P<0.001 ANOVA, Dunnett’s). This increase was due to an increase in VEGFxxx to 1592±526 pg/mg protein, and a downregulation of VEGFxxxb to 64±16 pg/mg protein. Thus, IGF induced a switch in expression such that cells that were originally producing 80±32% of their VEGF as VEGFxxxb, after IGF1 treatment produced only 5±1.9% of their VEGF as VEGFxxxb. To determine whether switching of isoforms could be induced by other cytokines, RPE cells were incubated in 50 ng/ml TNFα, and protein collected (Fig. 2B). TNFα induced an upregulation of VEGFtotal from 258±122 pg/mg protein to 1037±248 pg/mg protein (P<0.05), a mean increase of 7.8±3.0 fold (n=5). By contrast, 50 ng/ml TNFα, significantly downregulated VEGFxxxb isoforms (P<0.05) from 109±20 pg/mg to 38±10 pg/mg protein, a decrease of 64±6%. To determine whether isoform switching could be demonstrated in another epithelial cell type, we investigated podocytes. When these cells were treated with IGF, they showed a decrease in VEGFxxxb levels with a significant increase in total VEGF levels compared with control (Fig. 2C). To determine whether IGF1 altered regulation of the VEGF165 and VEGF165b isoforms of their respective families, western blotting was used. Fig. 3 shows that 100 nM IGF1 downregulated VEGF165b in RPE cell lysates (Fig. 3A), while resulting in an increase in total VEGF relative to loading control (β-actin, Fig. 3B). The cells produced VEGFs that are predominantly of higher molecular mass than recombinant protein because they are glycosylated fully [recombinant VEGF165 and VEGF165b are 38 kDa (unglycosylated) and 41.6 kDa (partially glycosylated) (Rennel et al., 2008b; Keck et al., 1997) as dimers, compared with 46 kDa for the endogenously produced protein (Rosenthal et al., 1990)].

Fig. 2.

Effect of IGF1 on expression of VEGFxxxb and VEGFxxx proteins. (A) Cell lysates from RPE cells that had been treated with increasing concentrations of IGF1 for 48 hours, and total VEGF and VEGFxxxb concentrations measured by ELISA. (B) Effect of TNFα on VEGF and VEGFxxxb levels in RPE cells. (C) VEGF and VEGFxxxb concentrations in podocytes treated with IGF1, *P<0.05, ***P<0.001 vs respective control, one-way ANOVA, Dunnett’s test, n=3.

Fig. 3.

(A,B) Effect of IGF1 on expression of (A) VEGF165b and (B) VEGF165/VEGF165b in RPE cells. Cell lysates from RPE cells that had been treated with 100 nM IGF for 48 hours or left untreated were resolved by SDS-PAGE and immunoblotted using (A) monoclonal antibody against VEGF165b or (B) a pan-VEGF antibody. Blots were stripped and re-probed with anti-actin antibody. (C) Density of bands (mean ± s.e.m.) demonstrating a significant downregulation of VEGF165b (n=4) and upregulation of VEGF165 vs VEGF165b (n=5) in RPE cells (*P<0.05 compared with control, paired t-tests)

TGFβ1 switches splicing to anti-angiogenic VEGF isoforms in podocytes

In contrast to IGF1 and TNFα, incubation with TGFβ1 at 0.5 nM and 1 nM for 48 hours significantly increased the level of VEGFxxxb protein (2.15±0.56 fold and 2.49±0.4 fold, respectively, P<0.01 Dunnett’s test) and total VEGF protein expression (1.13±0.01 and 1.52±0.1 fold, respectively, P<0.05 Dunnett’s test, (Fig. 4A). Thus VEGFxxx expression levels fell by 70±7% at 1 nM TGFβ1. To determine whether the VEGF165b isoform of the VEGFxxxb was being regulated by TGFβ1, (i.e. the qualitative nature of the alteration in splice family isoforms), western blotting was carried out on the cell lysate. Fig. 4B shows that the VEGF165b isoform was upregulated 1 nM TGFβ1. Fig. 4C shows densitometry of the blots, revealing statistically significant upregulation of VEGF165b by TGFβ1. To confirm that the changes seen by TGFβ1 were at the mRNA level, amplification of mRNA from podocytes was carried out using primers that detect both splice isoforms, the proximal (130-bp product) and distal (65-bp product) isoform. RT-PCR showed that TGFβ1 treatment (1 nM) resulted in an increase in relative density of the lower (VEGFxxxb) band (Fig. 4C).

Fig. 4.

Effect of TGF1 on expression of VEGFxxxb and VEGFtotal in podocytes. (A) ELISA of podocyte cell lysate for VEGFxxxb and VEGFtotal treated with TGFβ1. *P<0.05, **P<0.01 vs respective control, one-way ANOVA, Dunnett’s test, n=5. (B) Lysates of podocytes treated with TGF1 resolved by western blot using antibodies that detect VEGFxxxb. Densitometry of western blots show VEGF165b to be upregulated relative to control (n=3). (C) RT-PCR of cells exposed to 1 nM TGFβ1. The lower band, corresponding to VEGF165b is increased in intensity relative to the upper band (VEGF165). Densitometry (n=5) indicates a significant upregulation of VEGF165b relative to VEGF165 (**P<0.01, paired t-test).

Intracellular mechanisms through which VEGF165b splicing is regulated by cytokines

TGFβ1 has previously been shown to activate the p38 MAPK pathway (Herrera et al., 2001) (Bakin et al., 2004), which has also been involved in mechanisms of regulation of splicing (e.g. van der Houven van Oordt et al., 2000; Lin et al., 2007). To determine whether this signalling pathway is activated by TGFβ1 in podocytes, cells were treated with the p38 MAPK inhibitor SB203580 (Lechuga et al., 2004), or two other kinase inhibitors PD98059 (p42/p44 MAPK inhibitor) and TG003 (inhibitor of the CDC-like kinases 1 and 4 splicing factors Clk1 and Clk4).

To determine whether there was an effect of inhibitors on splicing, reverse transcriptase (RT)-PCR was carried out using primers that detect both proximal splice isoforms (VEGFxxx, 130-bp band) and distal splice isoforms (VEGFxxxb, 64-bp band). The increase in intensity of the lower band induced by 1 nM TGFβ1 (see Fig. 4C) was inhibited by SB203820 but not by PD98059 (Fig. 5A). Interestingly, TG003 also inhibited the TGFβ1-mediated increased intensity of the VEGFxxxb band. Densitometric analysis confirmed that the relative intensity of the VEGF165b band was significantly upregulated by TGFβ1, but not in the presence of SB203820 or TG003 (Fig. 5A). These findings were confirmed by western blotting (Fig. 5B). Densitometric analysis of the bands indicated that, whereas TGFβ1 resulted in a significant increase in density relative to control (P<0.01) even in the presence of PD98059 (P<0.05), there was no significant upregulation in the presence of TG003 or SB203820 (P>0.1, ANOVA on difference in intensity between TGFβ1 and respective control). This was confirmed quantitatively by ELISA. Fig. 5C shows that TGFβ1 increased VEGFxxxb expression by ∼60% compared with untreated control but, in the presence of SB203580 or TG003, TGFβ1 did not increase VEGFxxxb expression compared with respective drug-treated control. PD98059, however, did not affect the VEGFxxxb upregulation induced by TGFβ1. To confirm that p38 MAPK was involved in the TGFβ1-mediated upregulation of VEGF, podocytes were transfected with a dominant-negative p38 MAPK construct, and subsequently treated with TGFβ1. This resulted in a reduction in the increase in VEGF165b expression from 353 pg/ml in control transfected cells to 6 pg/ml in cells transfected with the p38 MAPK dominant-negative construct (Fig. 5C). To confirm that the treatment of podocytes with TGFβ1 resulted in increased phosphorylation of both p42/p44 MAPK and p38 MAPK, immunoblotting using phosphospecific antibodies was carried out (Fig. 5D). p38 MAPK phosphorylation was increased by TGFβ1, and this was inhibited by SB203580. p42/p44 MAPK phosphorylation was inhibited by PD98059 (Fig. 5D).

Fig. 5.

Regulation of distal splice-site selection by p38 MAPK and p42/p44 MAPK, and Clk1 and Clk4. Podocytes were treated with the p38 MAPK inhibitor SB203580 (10 μM), the p42/p44 MAPK inhibitor PD98059 (10 μM) or the Clk/Sty inhibitor TG003 (1 μM) in the presence or absence of 1 nM TGF1. (A) mRNA from cells treated as above were subjected to RT-PCR using primers that detect both isoform families of VEGF, *P<0.05 compared with control, +P<0.05 compared with TGF alone. (B) Proteins were resolved by immunoblotting. (C) Quantitative ELISA for VEGFxxxb and VEGFtotal. TGF1-mediated upregulation of distal splicing was not seen in the presence of SB203580, DN-p38MAPK or TG003 but was present during PD98059 treatment. ***P<0.001 compared with vehicle, *P<0.05 compared with drug control. (D) TGFβ1 induces phosphorylation of p38 MAPK and p42/p44 MAPK in human podocytes was inhibited by SB203580 and PD98059, respectively.

Alteration of splicing by transfection of RPE cells with known splicing factors

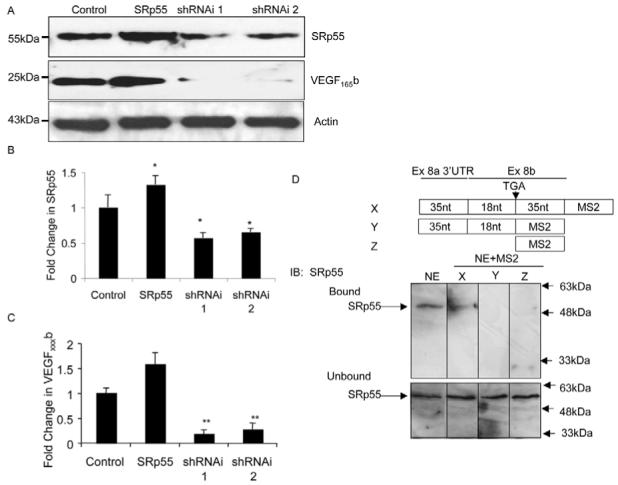

Clk1/sty has been shown to result in phosphorylation of three known splicing factors ASF/SF2, SRp55 and SRp40. (Prasad et al., 1999; Lai et al., 2003). The distribution of known ESE consensus sequences for these splicing factors in the 3′ end of VEGF pre-mRNA, generated from ESE Finder (rulai.cshl.edu/tools/ESE) are displayed in Fig. 6. There is a strong cluster of SRp55-binding sites just distal to the distal splice sites, and a strong cluster of ASF/SF2 and SRp40 sites adjacent to the proximal splice site. To determine whether these splice factors can regulate VEGF terminal exon splice-site selection, we transfected RPE cells with splicing factor cDNAs in expression vectors, and protein from cell lysate (quantified by Bradford assay and equally loaded) and analysed by western blotting (densitometrically, Fig. 7). ASF/SF2 did not significantly increase the amount of VEGF165b in the cell lysate, but increased the amount of VEGFtotal (mean ± s.e.m., n=3 41.4±6.9%, P<0.05, Fig. 7A). Neither 9G8 nor SRp40 significantly increased VEGFxxxb or VEGFtotal levels in the cell lysate (Fig. 7B). SRp55 increased the amount of VEGFxxxb (104.5±18.0%, P<0.05) but did not increase VEGFtotal (e.g. Fig. 7A). To determine the effect of these changes on overall relative expression levels, the concentration of VEGFxxxb to VEGFtotal was calculated (Fig. 7C). It can be seen that SRp55 results in a significant switch in splicing towards the anti-angiogenic VEGF isoforms. These results indicate that splicing factors, such as ASF/SF2 and SRp55, regulate the alternative splicing of the VEGF pre-mRNA, which determines the C-terminus of VEGF. To further identify the role of SRp55 in the regulation of distal splice-site selection, overexpression and knockdown experiments were performed. Fig. 8A shows that overexpression of SRp55 in RPE cells resulted in clear upregulation of SRp55 and VEGF165b levels. By contrast, two different small hairpin RNAs (shRNAs) targeting SRp55 demonstrated a significant downregulation of both SRp55 and VEGF165b (Fig. 8B shows the fold change in SRp55 and Fig. 8C the fold change in VEGF165b, P<0.01 ANOVA), without affecting β-actin. To determine whether SRp55 can bind directly to the distal splice site RNA, we used the MS2-MBP system to pull down proteins that can interact with the RNA. Fig. 8D shows that SRp55 is present in both crude nuclear extract and in the pull down of nuclear extract incubated with an RNA containing the MS2-binding-domain RNA fused to a 88 nucleotide fragment that contains the terminal 35 nucleotides of exon 8a, the coding sequence of exon 8b and 35 nucleotides of 3′UTR. By contrast, SRp55 was not seen in the pull down of nuclear extract incubated with the mRNA that did not have the 35 nucleotides of exon 8b 3′UTR, or incubated with the MS2-binding domain itself, indicating that SRp55 can bind directly to a 35 nucleotide fragment of exon 8b downstream of the stop codon.

Fig. 6.

Distribution of ESE consensus sequences in the C terminus of the VEGF gene. The SRp55 sites were associated with distal splicing whereas the SF2/ASF and SRp40 sites were more associated with the proximal splice sites.

Fig. 7.

Effect of overexpression of splicing factors on VEGF isoform production. (A) Retinal pigmented epithelial cells were transfected with splicing factors and distal splicing isoforms (VEGFxxxb) and total VEGF levels determined by SDS-PAGE and western blotting. (B) Densitometry of cell lysates showing expression of VEGF165b and total VEGF after transfection with splice factors. (C) The difference in VEGF expression between VEGFxxxb and total VEGF is shown relative to controls for splice factors. Solid line indicates an equal balance between the two sets of isoforms. Values below the line indicate anti-angiogenic balance, above a pro-angiogenic balance (*P<0.05 compared with untreated, ANOVA, Dunnett’s test. n=3).

Fig. 8.

SRp55 regulates VEGF splice-site selection in exon 8. (A) RPE cells were transfected with SRp55 or shRNA targeting SRP55, and VEGF165b expression measured by immunoblotting. siRNA targeting SRp55 downregulated both SRp55 and VEGF165b. (B) Densitometry indicated that both shRNAs targeting SRp55 inhibited SRp55 expression (n=4). (C) shRNAs targeting SRp55 also inhibited VEGF165b expression (n=3, *P<0.05, **P<0.01 compared with control, ANOVA, Dunnett’s test). (D) MS2-MBP assay for RNA-binding sites of HEK-cell nuclear extract. SRp55 was detected by immunoblotting in nuclear extract (NE) and when bound to a RNA construct containing the 35 nucleotides downstream of the stop codon for exon 8b (construct X), but not when this region was deleted (construct Y) or MS2 RNA (construct Z).

Discussion

The balance of the VEGFxxx (pro-angiogenic) and VEGFxxxb (anti-angiogenic) families, derived from the same gene, may have a crucial role in the control of angiogenesis in health; an imbalance could underpin pathological angiogenesis. Understanding the properties, expression and control of the VEGFxxxb family might therefore have wide-ranging therapeutic implications in diseases as diverse as cancer, vascular disease, arthritis, diabetes, renal disease and psoriasis. Therapies that inhibit angiogenesis have been approved after major phase-III clinical trials in cancer and age-related macular degeneration (AMD) (Gragoudas et al., 2004; Hurwitz et al., 2004). Phase-II and -III trials show significant efficacy of anti-VEGF therapies in colorectal (Hurwitz et al., 2004; McCarthy, 2003) and renal-cell carcinomas (Yang et al., 2003) and in AMD (Eyetech Study Group, 2003). However, the concept of alternate splicing of the VEGF gene resulting in anti-angiogenic as well as pro-angiogenic isoforms indicates that it might be insufficient simply to measure the quantitative changes of the VEGF molecule in cancer and other diseases; a quantitative characterisation of the balance of each isoform family might be essential to define the optimal therapeutic option and dosing.

Despite the fact that there are 12 splice variants of VEGF that have been identified so far (Fig. 1) - with varying bio-availability and activity - very few studies have considered the mechanisms of pre-mRNA splicing of VEGF. This is the first study to examine the effect of known splicing factors and other agents on pre-mRNA splicing that affects the C-terminus of VEGF, a process that might profoundly influence the angiogenic phenotype of a tissue. We found splicing factors (particularly SRp55) and growth factors (especially TGFβ1) that can preferentially select for the distal splice site - in the case of SRp55 through direct binding to the RNA - although the potential interaction of these agents is unknown.

However, SRFs are regulated by specific signalling molecules, either directly (SR protein kinases, such as Clk1 or SRPKs), or indirectly (MAPKs and PKC). SRPKs phosphorylate ASF/SF2, which favours proximal splicing. VEGF has been shown to be upregulated by many conditions and factors, such as hypoxia (Shweiki et al., 1992), and interleukin 1β (Li et al., 1995), IGF1 (Goad et al., 1996), TGFβ1 (Pertovaara et al., 1994) and PDGF (Finkenzeller et al., 1997). Moreover, VEGF can be inhibited by hyperoxia (Perkett and Klekamp, 1998), IL10 and IL13 (Matsumoto et al., 1997), but the detailed influence these factors have on the VEGFxxx and VEGFxxxb sub-family switch in general is still unknown.

Our discussion clearly does not cover areas such as transcriptional control of splicing (Cramer et al., 1999). Splicing factors are recruited to the transcriptional machinery because of their interaction with the C-terminal domain of RNA polymerase II and its processivity at the 5′ end of the mRNA (Hirose et al., 1999; Koenigsberger et al., 2000). Alternate 5′ transcriptional start sites have been demonstrated for VEGF (Neufeld et al., 1996). These might result in recruitment of different splice factors and, hence, alternative splicing. Other factors and mechanisms, such as exon-splicing silencers and poly-pyrimidine tract-binding-protein-mediated repression of splicing, are also likely to be regulators of VEGF splicing.

Regulation of alternative splicing is unlikely to be an event within the angiogenic phenotype that is unique to VEGF. Many other proteins in the angiogenic cascade have alternate, inhibitory splice variants, which suggests that the common mechanisms and coordinated alteration in the splicing of genes, such as VEGF, VEGF-R1, thrombospondin, HIF1, collagen, fibronectin and others, might be fundamental in the regulation of angiogenesis, vascular remodelling and disease processes in many pathologies of the Western world, including cancer, diabetes and heart disease.

The human foetus and the fully grown adult possess the same species-specific genome. However, it is the isoform-specific and temporarily specific proteome, not the genome, that characterises the differing phenotypes. The proteome determines health and disease and, in disease, the clinical picture, and the response to treatment and prognosis. More specifically, in many circumstances, it is the isoform- and time-specific pattern of alternative splicing that determines the phenotype. For example, abnormalities of splice-variant-expression patterns of a wide variety of proteins have been highlighted as a characteristic of malignant change (Venables, 2006), and with the pro-angiogenic phenotype that is associated with cancer and other conditions (Bates et al., 2002). This is most clearly demonstrated in the human vitreous. In non-diabetic human vitreous VEGFxxxb (anti-angiogenic) comprises 60% of VEGF. In diabetics suffering from proliferative retinopathy, this proportion drops to 16% - a pro-angiogenic phenotype therefore predominates (Perrin et al., 2005).

In summary, the C-terminal VEGF angiogenic switch might be a fundamental control mechanism for neo-vascularisation. Understanding this splicing switch will enhance our understanding of blood-vessel growth in normal tissues and in pathological states as diverse as diabetes and cancer. Furthermore, the potential manipulation of the splicing control, in conjunction with unaltered promoter activity - to promote distal (exon 8b - anti-angiogenic) rather than proximal (exon 8a - pro-angiogenic) splice-site selection - would promote a therapy that, in the cancer example, may encourage the tumor to switch off its own nutrient supply. Indeed, the more hypoxic the tumour becomes, the more effective this therapeutic switch might be. A greater understanding of VEGF splicing might enable us to change many molecules, not just VEGF, from tumour-supporting pro-angiogenic to tumour-killing anti-angiogenic variants.

Materials and Methods

Plasmids

SRp40, ASF/SF2, SRp55, 9G8 in pCGTVP16C were a kind gift of Javier Caceres, University of Edinburgh, UK. SRp55 shRNA was a kind gift of Gilbert Cote, M. D. Anderson Cancer Centre, University of Texas, TX (Jin and Cote, 2004). Dominant-negative p38 MAPK (pMEVHA-P38-K53M) was purchased from Biomyx (San Diego, CA).

RPE cell culture

Human donor eyes were obtained within 10-30 hours post-mortem from the Bristol Eye Bank. Choroid-RPE sheets dissected from ocular globes were fragmented in a small amount of DMEM:F12 (1:1) supplemented with GlutaMAX (Gibco), and RPE cells were isolated by digestion with 0.3 mg/ml collagenase (Gibco) for 15 minutes at 37°C. RPE cells were initially cultured for 5 days in the presence of 2.5% v/v foetal bovine serum (FBS; Gibco) to prevent proliferation of fibroblasts and until the cell cultures became established. After the first passage cell culture was maintained in DMEM:F12 (1:1), supplemented with 10% v/v FBS and antibiotic-antimycotic solution (Sigma). The once-passaged cells were homogeneous and contained only RPE as characterised by immunohistochemistry with anti-cytokeratin monoclonal antibody (Sigma). RPE cells were routinely subcultured by trypsinisation (trypsin/EDTA, Sigma). RPE cells at passage 3-4 were plated onto 12.5-cm2 Petri dishes (Nunc). Having reached 70-80% confluency, RPE cells were cultured in freshly-replaced medium in the absence of FBS for 24 hours prior to agonist stimulation to determine the effects of agonists. IGF1 (Sigma) and TNFα (Sigma) were prepared in serum-free medium and were added to the volume of 2 ml at various concentrations, as indicated. No changes in cell morphology were noticed after stimulation. 24 hours later, conditioned medium of cells in all experimental treatments was collected, spun down to remove debris and placed immediately into −80°C until ELISA. The RPE cells were washed three times with ice-cold PBS and lysed in Laemmli buffer for western blotting.

Podocyte cell culture

Proliferating conditionally immortalised podocytes (PCIPs; kindly donated by Moin Saleem, University of Bristol, UK) were derived from cell lines that had been conditionally transformed from normal human podocytes with temperature-sensitive mutant of immortalised SV-40 T-antigen. At the permissive temperature of 33°C the SV-40 T-antigen is active and allows the cells to proliferate rapidly (Saleem et al., 2002). PCIPs were cultured in T75 flasks (Greiner) using RPMI-1640 medium (Sigma) with 10% FBS, 1% ITS (insulin-transferrin-selenium) (Sigma), 0.5% penicillin-streptomycin (Sigma) and grown to 95% confluency. Cells were then split to six-well plates (1×105 cells per well) and grown until 95% confluent. We investigated time- and dose-dependent effects of IGF1, and TGF1 on production of VEGF isoforms from cultured PCIPs. Twenty-four hours before treatment, cultured medium was replaced with serum-free RPMI-1654 medium (Sigma) containing 1% ITS (Sigma) and 0.5% penicillin-streptomycin. Subsequently, the medium was replaced with fresh serum-free RPMI-1610 medium (Sigma) containing 1% ITS (Sigma), 0.5% penicillin-streptomycin and increasing concentrations of IGF1 (Sigma) or TGF1 (Sigma).

RT-PCR

1 ml of Trizol reagent was added to each well of a six-well plate and mRNA extracted using the method described by Chomczynski and Sacchi (Chomczynski and Sacchi, 1987). 50% of the mRNA was reverse transcribed using MMLV reverse transcriptase, RNase H Minus, Point mutant (Promega) and polyd(T) (Promega) as a primer. 10% of the cDNA was then amplified using primers designed to pick up proximal and distal splice forms (Fig. 1). 1 μM of a primer complementary to exon 7b of VEGF (5′-GGCAGCTTGAGTTAAACGAAC-3′) corresponding to nt −24 to −13 from the end of exon 7, and 1 μM of a primer complementary to 3′UTR (5′-ATGGATCCGTATCAGTCTTTCCTGG-3′ equivalent to the last three amino acids of the open reading frame for exon 8b and the stop codon, underlined is the complementary sequence) and PCR Master Mix (Promega) were used. Reactions were cycled 30 times, with denaturing at 95°C for 60 seconds, annealing at 55°C for 60 seconds and extending at 72°C for 60 seconds. PCR products were run on 2.5% agarose gels containing 0.5 μg/ml ethidium bromide and visualised under a UV transilluminator. This reaction consistently resulted in one amplicon at ∼130 bp (consistent with VEGFxxx), and one amplicon at ∼64 bp, consistent with VEGFxxxb isoforms. PCR blots are representative of at least two different experiments.

Assessment of protein production following transfection of candidate splicing factors

RPE cells were grown in six-well plates, each seeded with 3×105 cells and subsequently transfected with 1 μg of SRp40, ASF/SF2, SRp55, 9G8 in pCGTVP16C or an empty expression vector using Lipofectamine (Invitrogen). Following incubation at 37°C for 48 hours, conditioned medium was collected and cells were lysed in buffer containing: 20 mM Tris, pH 7.4, 1.5% w/v Triton X-100, 150 mM NaCl, 10% w/v glycerol and protease inhibitor cocktail (Sigma). VEGF isoforms were measured in cell lysate or conditioned medium was measured using ELISA and protein production assessed via western blotting, as outlined below.

Assessment of protein production following transfection with genetic inhibitors

Cells were grown in six-well plates, each seeded with 3×105 cells per well cells and subsequently transfected with 1 μg of shRNA against SRp55, dominant-negative p38 MAPK or an empty expression vector using GeneJuice® (Novagen). Following incubation at 33°C for 48 hours (with shRNA), or after the appropriate treatment with TGFβ1 (with p38MAPK-DN), cell lysate was extracted with RIPA buffer.

VEGF measurements

Total VEGF concentrations were measured using a first-generation DuoSet VEGF ELISA (R&D Systems) according to manufacturer’s instruction. We have previously described this kit as having a lower affinity for VEGF165b than for VEGF165 and, so, total VEGF levels were calculated as previously described (Varey et al., 2008). VEGFxxxb was determined with a similar sandwich ELISA, using for detection a monoclonal biotinylated mouse anti-human antibody raised against the terminal nine amino acids of VEGF165b (R&D Systems; clone 264610/1), and a standard curve for this assay was built with recombinant human VEGF165b (R&D Systems) (Varey et al., 2008). This antibody is an affinity-purified mouse monoclonal IgG1 antibody.

The levels of VEGFxxxb found free in the cell supernatant were sometimes at or below the limit of the detection threshold, particularly after downregulation with growth factors. Therefore, the total protein in conditioned medium was precipitated with trichloroacetic acid (TCA) for the VEGFxxxb ELISA. For this purpose, 250 μl ice-cold TCA (24%) and 6.25 μl sodium deoxycholate (12%) were added to 700 μl conditioned medium and left on ice for 15 minutes. After centrifugation at 5000 g for 10 minutes, pellets were collected and re-suspended in lysis buffer, which contained 20 mM Tris, pH 7.4, 1.5% w/v Triton X-100, 150 mM NaCl, 10% w/v glycerol and protease inhibitor cocktail (Sigma). The pH in the pelleted samples was adjusted to 7.4 with 1.5 M Tris (pH 8.8). The total protein content in the pellet was measured using Bradford Assay (Bio-Rad).

Western blotting

Protein samples were dissolved in Laemmli buffer, boiled for 3-4 minutes and centrifuged for 2 minutes at 20,000 g to remove insoluble materials. 30 μg protein per lane were separated by SDS-PAGE (12%) and transferred to 0.2 μm nitrocellulose membrane. The blocked membranes were probed overnight (4°C) with the following antibodies: panVEGF (R&D Systems; MAB 293, 1:500), anti-VEGFxxxb (R&D Systems; MAB3045; 1:250), anti-phospho-p38 MAP kinase (Thr180-Tyr182) antibody (Cell Signaling 9216), anti-phospho-p44/p42 MAPK (Thr202-Tyr204) (Cell Signaling 9106), anti-p44/42 MAPK (Cell Signaling 9102) and anti-β-tubulin (Sigma; 1:2000). Western blotting has previously shown that all the proteins recognised by the anti-VEGFxxxb antibody are also recognised by commercial antibodies raised against VEGF165. It binds recombinant VEGF165b, and can be used to demonstrate expression of VEGF165b, VEGF189b, VEGF121b VEGF183b and VEGF145b (collectively termed VEGFxxxb) but does not recognise VEGF165, which conclusively demonstrates that this antibody is specific for VEGFxxxb (Woolard et al., 2004). Subsequently, the membranes were incubated with secondary HRP-conjugated antibody, and immunoreactive bands were visualised using ECL reagent (Pierce). The immunoreactive bands corresponding to panVEGF and VEGFxxxb in each treatment were quantified by ImageJ analysis and normalised to those of β-tubulin. Blots are representative of at least three experiments. Densitometry was carried out by scanning gels and using ImageJ to determine grey levels of bands and background.

Construction of plasmids

The VEGF sequence of interest (from 35 upstream of exon 8a till 35 bp downstream of exon 8b) was amplified from a BAC DNA template using 50 ng of BAC DNA, 10 μM of each primers (see Table 1), 10 μM dNTP mix (Promega) and Taq Polymerase (Promega). A modified ADML-MS2 plasmid was digested with EcoR1 and BamH1 and PCR products ligated into the vector and subsequently transformed. Colonies were selected and plasmid extraction (Qiagen) was performed. The identities of the plasmids were confirmed by sequencing.

Expression of the MS2-MBP fusion protein

MS2-maltose-binding protein (MBP) fusion protein (a gift from Robin Reed, Harvard University, Boston, MA) was expressed in E.coli DH5α. The cells were grown to an OD600 of 0.5 at and induced for expression for 3 hours with 0.2 mM IPTG. The MS2-MBP protein was purified by amylose beads according to manufacturer’s protocol (NEB, Beverly, MA). Protein was dialysed with 10 mM sodium phosphate pH 7 overnight at 4°C to remove salts and further purified over a heparin Hi Trap column by using a NaCl gradient (GE Healthcare). Immunoblot analysis was performed on the purified fusion-proteins using rabbit anti-MS2 antibody (gift from Peter Stockley, Leeds University, Leeds, UK) to confirm the identity of the protein.

Assembly of the MS2-MBP system

1 μg of the VEGF-MS2 plasmids was linearised with Xba1 and in-vitro transcribed with T7 RNA polymerase (NEB) in 0.5 mM rNTP (Ambion), 40 mM Tris-HCL, 6 mM MgCl2, 10 mM dithiothreitol, 2 mM spermidine at 40°C for 1 hour to make VEGF-MS2 RNA. A 100-fold molar excess of MS2-MBP fusion protein and VEGF-MS2 RNA were incubated in a buffer containing 20 mM HEPES pH 7.9 and 60 mM NaCl on ice for 30 minutes. 75 μg of HEK-293-cell nuclear extract was added to the MS2-MBP-VEGF RNA mix in 0.5 mM ATP, 6.4 mM MgCl2, 20 mM creatine phosphate for 1 hour at 30°C. Proteins that bound to the MS2-MBP-VEGF-MS2 RNA complex were affinity selected on amylose beads by rotating for 4 hours at 4°C and eluted with 12 mM maltose, 20 mM HEPES pH 7.9, 60 mM NaCl, 10 mM β-mercapthoethanol and 1 mM PMSF.

Statistical analysis

Statistical analyses were carried out on raw data using the Friedman test (Dunnett’s post t-test) and P<0.05 was considered statistically significant. Values are expressed as the means ± s.e.m. For all data, n represents the number of independent RPE cell populations deriving from different donors.

References

- Asano-Kato N, Fukagawa K, Okada N, Kawakita T, Takano Y, Dogru M, Tsubota K, Fujishima H. TGF-beta1, IL-1beta, and Th2 cytokines stimulate vascular endothelial growth factor production from conjunctival fibroblasts. Exp. Eye Res. 2005;80:555–560. doi: 10.1016/j.exer.2004.11.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bakin AV, Safina A, Rinehart C, Daroqui C, Darbary H, Helfman DM. A critical role of tropomyosins in TGF-beta regulation of the actin cytoskeleton and cell motility in epithelial cells. Mol. Biol. Cell. 2004;15:4682–4694. doi: 10.1091/mbc.E04-04-0353. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bates DO, Cui TG, Doughty JM, Winkler M, Sugiono M, Shields JD, Peat D, Gillatt D, Harper SJ. VEGF165b, an inhibitory splice variant of vascular endothelial growth factor, is down-regulated in renal cell carcinoma. Cancer Res. 2002;62:4123–4131. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bates DO, MacMillan PP, Manjaly JG, Qiu Y, Hudson SJ, Bevan HS, Hunter AJ, Soothill PW, Read M, Donaldson LF, et al. The endogenous anti-angiogenic family of splice variants of VEGF, VEGFxxxb, are down-regulated in pre-eclamptic placentae at term. Clin. Sci. 2006;110:575–585. doi: 10.1042/CS20050292. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blaustein M, Pelisch F, Tanos T, Munoz MJ, Wengier D, Quadrana L, Sanford JR, Muschietti JP, Kornblihtt AR, Caceres JF, et al. Concerted regulation of nuclear and cytoplasmic activities of SR proteins by AKT. Nat. Struct. Mol. Biol. 2005;12:1037–1044. doi: 10.1038/nsmb1020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Caceres JF, Kornblihtt AR. Alternative splicing: multiple control mechanisms and involvement in human disease. Trends Genet. 2002;18:186–193. doi: 10.1016/s0168-9525(01)02626-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carmeliet P. VEGF gene therapy: stimulating angiogenesis or angioma-genesis? Nat. Med. 2000;6:1102–1103. doi: 10.1038/80430. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cebe Suarez S, Pieren M, Cariolato L, Arn S, Hoffmann U, Bogucki A, Manlius C, Wood J, Ballmer-Hofer K. A VEGF-A splice variant defective for heparan sulfate and neuropilin-1 binding shows attenuated signaling through VEGFR-2. Cell. Mol. Life Sci. 2006;63:2067–2077. doi: 10.1007/s00018-006-6254-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Celletti FL, Waugh JM, Amabile PG, Brendolan A, Hilfiker PR, Dake MD. Vascular endothelial growth factor enhances atherosclerotic plaque progression. Nat. Med. 2001;7:425–429. doi: 10.1038/86490. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Charnock-Jones DS, Macpherson AM, Archer DF, Leslie S, Makkink WK, Sharkey AM, Smith SK. The effect of progestins on vascular endothelial growth factor, oestrogen receptor and progesterone receptor immunoreactivity and endothelial cell density in human endometrium. Hum. Reprod. 2000;15(Suppl. 3):85–95. doi: 10.1093/humrep/15.suppl_3.85. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chomczynski P, Sacchi N. Single-step method of RNA isolation by acid guanidinium thiocyanate-phenol-chloroform extraction. Anal. Biochem. 1987;162:156–159. doi: 10.1006/abio.1987.9999. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cohen CD, Doran PP, Blattner SM, Merkle M, Wang GQ, Schmid H, Mathieson PW, Saleem MA, Henger A, Rastaldi MP, et al. Sam68-like mammalian protein 2, identified by digital differential display as expressed by podocytes, is induced in proteinuria and involved in splice site selection of vascular endothelial growth factor. J. Am. Soc. Nephrol. 2005;16:1958–1965. doi: 10.1681/ASN.2005020204. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cramer P, Caceres JF, Cazalla D, Kadener S, Muro AF, Baralle FE, Kornblihtt AR. Coupling of transcription with alternative splicing: RNA pol II promoters modulate SF2/ASF and 9G8 effects on an exonic splicing enhancer. Mol. Cell. 1999;4:251–258. doi: 10.1016/s1097-2765(00)80372-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cui TG, Foster RR, Saleem M, Mathieson PW, Gillatt DA, Bates DO, Harper SJ. Differentiated human podocytes endogenously express an inhibitory isoform of vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF165b) mRNA and protein. Am. J. Physiol. Renal Physiol. 2004;286:F767–F773. doi: 10.1152/ajprenal.00337.2003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dowhan DH, Hong EP, Auboeuf D, Dennis AP, Wilson MM, Berget SM, O’Malley BW. Steroid hormone receptor coactivation and alternative RNA splicing by U2AF65-related proteins CAPERalpha and CAPERbeta. Mol. Cell. 2005;17:429–439. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2004.12.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eyetech Study Group Anti-vascular endothelial growth factor therapy for subfoveal choroidal neovascularization secondary to age-related macular degeneration: phase II study results. Ophthalmology. 2003;110:979–986. doi: 10.1016/S0161-6420(03)00085-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ferrara N, Davis-Smyth T. The biology of vascular endothelial growth factor. Endocr. Rev. 1997;18:4–25. doi: 10.1210/edrv.18.1.0287. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Finkenzeller G, Sparacio A, Technau A, Marme D, Siemeister G. Sp1 recognition sites in the proximal promoter of the human vascular endothelial growth factor gene are essential for platelet-derived growth factor-induced gene expression. Oncogene. 1997;15:669–676. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1201219. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Folkman J. Tumor angiogenesis. Adv. Cancer Res. 1985;43:175–203. doi: 10.1016/s0065-230x(08)60946-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goad DL, Rubin J, Wang H, Tashjian AH, Jr, Patterson C. Enhanced expression of vascular endothelial growth factor in human SaOS-2 osteoblast-like cells and murine osteoblasts induced by insulin-like growth factor I. Endocrinology. 1996;137:2262–2268. doi: 10.1210/endo.137.6.8641174. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gragoudas ES, Adamis AP, Cunningham ET, Jr, Feinsod M, Guyer DR. Pegaptanib for neovascular age-related macular degeneration. N. Engl. J. Med. 2004;351:2805–2816. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa042760. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Herrera B, Fernandez M, Roncero C, Ventura JJ, Porras A, Valladares A, Benito M, Fabregat I. Activation of p38MAPK by TGF-beta in fetal rat hepatocytes requires radical oxygen production, but is dispensable for cell death. FEBS Lett. 2001;499:225–229. doi: 10.1016/s0014-5793(01)02554-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hertel KJ, Lynch KW, Maniatis T. Common themes in the function of transcription and splicing enhancers. Curr. Opin. Cell Biol. 1997;9:350–357. doi: 10.1016/s0955-0674(97)80007-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hirose Y, Tacke R, Manley JL. Phosphorylated RNA polymerase II stimulates pre-mRNA splicing. Genes Dev. 1999;13:1234–1239. doi: 10.1101/gad.13.10.1234. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Houck KA, Ferrara N, Winer J, Cachianes G, Li B, Leung DW. The vascular endothelial growth factor family: identification of a fourth molecular species and characterization of alternative splicing of RNA. Mol. Endocrinol. 1991;5:1806–1814. doi: 10.1210/mend-5-12-1806. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hurwitz H, Fehrenbacher L, Novotny W, Cartwright T, Hainsworth J, Heim W, Berlin J, Baron A, Griffing S, Holmgren E, et al. Bevacizumab plus irinotecan, fluorouracil, and leucovorin for metastatic colorectal cancer. N. Engl. J. Med. 2004;350:2335–2342. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa032691. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jin W, Cote GJ. Enhancer-dependent splicing of FGFR1 alpha-exon is repressed by RNA interference-mediated down-regulation of SRp55. Cancer Res. 2004;64:8901–8905. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-04-0716. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kalnina Z, Zayakin P, Silina K, Line A. Alterations of pre-mRNA splicing in cancer. Genes Chromosomes Cancer. 2005;42:342–357. doi: 10.1002/gcc.20156. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Keck RG, Berleau L, Harris R, Keyt BA. Disulfide structure of the heparin binding domain in vascular endothelial growth factor: characterization of posttranslational modifications in VEGF. Arch. Biochem. Biophys. 1997;344:103–113. doi: 10.1006/abbi.1997.0145. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koenigsberger C, Chicca JJ, 2nd, Amoureux MC, Edelman GM, Jones FS. Differential regulation by multiple promoters of the gene encoding the neuron-restrictive silencer factor. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2000;97:2291–2296. doi: 10.1073/pnas.050578797. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Konopatskaya O, Churchill AJ, Harper SJ, Bates DO, Gardiner TA. VEGF165b, an endogenous C-terminal splice variant of VEGF, inhibits retinal neovascularization in mice. Mol. Vis. 2006;12:626–632. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kornblihtt AR. Promoter usage and alternative splicing. Curr. Opin. Cell Biol. 2005;17:262–268. doi: 10.1016/j.ceb.2005.04.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kotsuji-Maruyama T, Imakado S, Kawachi Y, Otsuka F. PDGF-BB induces MAP kinase phosphorylation and VEGF expression in neurofibroma-derived cultured cells from patients with neurofibromatosis 1. J. Dermatol. 2002;29:713–717. doi: 10.1111/j.1346-8138.2002.tb00208.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lai MC, Lin RI, Tarn WY. Differential effects of hyperphosphorylation on splicing factor SRp55. Biochem. J. 2003;371:937–945. doi: 10.1042/BJ20021827. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lechuga CG, Hernandez-Nazara ZH, Dominguez Rosales JA, Morris ER, Rincon AR, Rivas-Estilla AM, Esteban-Gamboa A, Rojkind M. TGF-beta1 modulates matrix metalloproteinase-13 expression in hepatic stellate cells by complex mechanisms involving p38MAPK, PI3-kinase, AKT, and p70S6k. Am. J. Physiol. Gastrointest. Liver Physiol. 2004;287:G974–G987. doi: 10.1152/ajpgi.00264.2003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li H, Yonekura H, Kim CH, Sakurai S, Yamamoto Y, Takiya T, Futo S, Watanabe T, Yamamoto H. Possible participation of pICln in the regulation of angiogenesis through alternative splicing of vascular endothelial growth factor receptor mRNAs. Endothelium. 2004;11:293–300. doi: 10.1080/10623320490904250. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li J, Perrella MA, Tsai JC, Yet SF, Hsieh CM, Yoshizumi M, Patterson C, Endege WO, Zhou F, Lee ME. Induction of vascular endothelial growth factor gene expression by interleukin-1 beta in rat aortic smooth muscle cells. J. Biol. Chem. 1995;270:308–312. doi: 10.1074/jbc.270.1.308. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lin JC, Hsu M, Tarn WY. Cell stress modulates the function of splicing regulatory protein RBM4 in translation control. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2007;104:2235–2240. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0611015104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Matlin AJ, Clark F, Smith CW. Understanding alternative splicing: towards a cellular code. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell. Biol. 2005;6:386–398. doi: 10.1038/nrm1645. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Matsumoto K, Ohi H, Kanmatsuse K. Interleukin 10 and interleukin 13 synergize to inhibit vascular permeability factor release by peripheral blood mononuclear cells from patients with lipoid nephrosis. Nephron. 1997;77:212–218. doi: 10.1159/000190275. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McCarthy M. Antiangiogenesis drug promising for metastatic colorectal cancer. Lancet. 2003;361:1959. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(03)13603-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Misteli T, Caceres JF, Spector DL. The dynamics of a pre-mRNA splicing factor in living cells. Nature. 1997;387:523–527. doi: 10.1038/387523a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mukhopadhyay D, Tsiokas L, Zhou XM, Foster D, Brugge JS, Sukhatme VP. Hypoxic induction of human vascular endothelial growth factor expression through c-Src activation. Nature. 1995;375:577–581. doi: 10.1038/375577a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Neufeld G, Cohen T, GitayGoren H, Poltorak Z, Tessler S, Sharon R, Gengrinovitch S, Levi BZ. Similarities and differences between the vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF) splice variants. Cancer and Metastasis Rev. 1996;15:153–158. doi: 10.1007/BF00437467. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Neufeld G, Cohen T, Gengrinovitch S, Poltorak Z. Vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF) and its receptors. FASEB J. 1999;13:9–22. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Patterson C, Perrella MA, Endege WO, Yoshizumi M, Lee ME, Haber E. Downregulation of vascular endothelial growth factor receptors by tumor necrosis factor-alpha in cultured human vascular endothelial cells. J. Clin. Invest. 1996;98:490–496. doi: 10.1172/JCI118816. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Perkett EA, Klekamp JG. Vascular endothelial growth factor expression is decreased in rat lung following exposure to 24 or 48 hours of hyperoxia: implications for endothelial cell survival. Chest. 1998;114:52S–53S. doi: 10.1378/chest.114.1_supplement.52s. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Perrin RM, Konopatskaya O, Qiu Y, Harper S, Bates DO, Churchill AJ. Diabetic retinopathy is associated with a switch in splicing from anti- to pro-angiogenic isoforms of vascular endothelial growth factor. Diabetologia. 2005;48:2422–2427. doi: 10.1007/s00125-005-1951-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pertovaara L, Kaipainen A, Mustonen T, Orpana A, Ferrara N, Saksela O, Alitalo K. Vascular endothelial growth factor is induced in response to transforming growth factor-beta in fibroblastic and epithelial cells. J. Biol. Chem. 1994;269:6271–6274. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Prasad J, Colwill K, Pawson T, Manley JL. The protein kinase Clk/Sty directly modulates SR protein activity: both hyper- and hypophosphorylation inhibit splicing. Mol. Cell. Biol. 1999;19:6991–7000. doi: 10.1128/mcb.19.10.6991. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pritchard-Jones RO, Dunn DB, Qiu Y, Varey AH, Orlando A, Rigby H, Harper SJ, Bates DO. Expression of VEGF(xxx)b, the inhibitory isoforms of VEGF, in malignant melanoma. Br. J. Cancer. 2007;97:223–230. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjc.6603839. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Qiu Y, Bevan H, Weeraperuma S, Wratting D, Murphy D, Neal CR, Bates DO, Harper SJ. Mammary alveolar development during lactation is inhibited by the endogenous antiangiogenic growth factor isoform, VEGF165b. FASEB J. 2007;22:1104–1112. doi: 10.1096/fj.07-9718com. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rak J, Mitsuhashi Y, Bayko L, Filmus J, Shirasawa S, Sasazuki T, Kerbel RS. Mutant ras oncogenes upregulate VEGF/VPF expression: implications for induction and inhibition of tumor angiogenesis. Cancer Res. 1995;55:4575–4580. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rennel E, Waine E, Guan H, Schuler Y, Leenders W, Woolard J, Sugiono M, Gillatt D, Kleinerman E, Bates D, et al. The endogenous anti-angiogenic VEGF isoform, VEGF165b inhibits human tumour growth in mice. Br. J. Cancer. 2008a;98:1250–1257. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjc.6604309. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rennel ES, H-Zadeh AM, Wheatley E, Schuler Y, Kelly SP, Cebe Suarez S, Ballmer-Hofer K, Stewart L, Bates DO, Harper SJ. Recombinant human VEGF165b protein is an effective anti-cancer agent in mice. Eur. J. Cancer. 2008b;44:1883–1894. doi: 10.1016/j.ejca.2008.05.027. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rosenthal RA, Megyesi JF, Henzel WJ, Ferrara N, Folkman J. Conditioned medium from mouse sarcoma 180 cells contains vascular endothelial growth factor. Growth Factors. 1990;4:53–59. doi: 10.3109/08977199009011010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Saleem MA, O’Hare MJ, Reiser J, Coward RJ, Inward CD, Farren T, Xing CY, Ni L, Mathieson PW, Mundel P. A conditionally immortalized human podocyte cell line demonstrating nephrin and podocin expression. J. Am. Soc. Nephrol. 2002;13:630–638. doi: 10.1681/ASN.V133630. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schumacher VA, Jeruschke S, Eitner F, Becker JU, Pitschke G, Ince Y, Miner JH, Leuschner I, Engers R, Everding AS, et al. Impaired glomerular maturation and lack of VEGF165b in Denys-Drash syndrome. J. Am. Soc. Nephrol. 2007;18:719–729. doi: 10.1681/ASN.2006020124. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shweiki D, Itin A, Soffer D, Keshet E. Vascular endothelial growth factor induced by hypoxia may mediate hypoxia-initiated angiogenesis. Nature. 1992;359:843–845. doi: 10.1038/359843a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith CW. Alternative splicing - when two’s a crowd. Cell. 2005;123:1–3. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2005.09.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sone H, Kawakami Y, Okuda Y, Kondo S, Hanatani M, Suzuki H, Yamashita K. Vascular endothelial growth factor is induced by long-term high glucose concentration and up-regulated by acute glucose deprivation in cultured bovine retinal pigmented epithelial cells. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 1996;221:193–198. doi: 10.1006/bbrc.1996.0568. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van der Houven van Oordt W, Diaz-Meco MT, Lozano J, Krainer AR, Moscat J, Caceres JF. The MKK(3/6)-p38-signaling cascade alters the subcellular distribution of hnRNP A1 and modulates alternative splicing regulation. J. Cell Biol. 2000;149:307–316. doi: 10.1083/jcb.149.2.307. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Varey AH, Rennel ES, Qiu Y, Bevan HS, Perrin RM, Raffy S, Dixon AR, Paraskeva C, Zaccheo O, Hassan AB, et al. VEGF 165 b, an antiangiogenic VEGF-A isoform, binds and inhibits bevacizumab treatment in experimental colorectal carcinoma: balance of pro- and antiangiogenic VEGF-A isoforms has implications for therapy. Br. J. Cancer. 2008;98:1366–1379. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjc.6604308. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Venables JP. Unbalanced alternative splicing and its significance in cancer. BioEssays. 2006;28:378–386. doi: 10.1002/bies.20390. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Woolard J, Wang WY, Bevan HS, Qiu Y, Morbidelli L, Pritchard-Jones RO, Cui TG, Sugiono M, Waine E, Perrin R, et al. VEGF165b, an inhibitory vascular endothelial growth factor splice variant: mechanism of action, in vivo effect on angiogenesis and endogenous protein expression. Cancer Res. 2004;64:7822–7835. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-04-0934. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang JC, Haworth L, Sherry RM, Hwu P, Schwartzentruber DJ, Topalian SL, Steinberg SM, Chen HX, Rosenberg SA. A randomized trial of bevacizumab, an anti-vascular endothelial growth factor antibody, for metastatic renal cancer. N. Engl. J. Med. 2003;349:427–434. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa021491. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]