Abstract

Both anxiety-related behavior [3,19] and the release of corticosterone following a psychogenic stress such as exposure to platform shaker was greater in female [3,21], but not male [22], oxytocin gene deletion (OTKO) mice compared to wild type (WT) cohorts. In the present study we exposed OTKO and WT female mice to another psychogenic stress, inserting a rectal probe to record body temperature followed by brief confinement in a metabolic cage, and measured plasma corticosterone following the stress. OTKO mice released more corticosterone than WT mice (P < 0.03) following exposure to this stress. In contrast, if OTKO and WT female and male mice were administered insulin-induced hypoglycemia, an acute physical stress, corticosterone release was not different between genotypes. The absence of central OT signaling pathways in female mice heightens the neuroendocrine (e.g., corticosterone) response to psychogenic stress, but not to the physical stress of insulin-induced hypoglycemia.

Keywords: corticosterone, hypoglycemia, stress-induced hyperthermia, oxytocin

Introduction

Oxytocin (OT), a nine amino acid peptide, is one of two neurohypophsial hormones, the other being the biologically and anatomically distinct but structurally similar nonapeptide, arginine vasopressin (AVP). The majority of OT is synthesized in the magnocellular neurons of the hypothalamic paraventricular and supraoptic nuclei (PVN and SON) and transported to the posterior lobe of the pituitary gland for storage and release into the periphery. Peripherally released OT is essential for milk ejection and is the sole mediator of this primitive reflex. If OT or its receptor (OTR) is absent, as in genetically engineered mice that lack the gene for OT [26,40] or OTR [30], milk ejection cannot occur. Although OT facilitates uterine contractility during labor and delivery, parturition is not impeded in mice lacking either OT [26,40] or OTR [30].

A lesser amount of OT is synthesized in the parvocellular neurons of the PVN, as well as a few select forebrain nuclei, and is released within the central nervous system (CNS). Within the CNS of rodents, OT is believed to influence complex behaviors, such as social interaction [9,10,16], maternal behavior [28], anxiety [5,19,23], aggression [37], and the response to psychogenic stress [3,21,24,25,35,36]. One psychogenic stress, exposure to platform shaker, activated OT, but not AVP, neurons of the PVN of the rat [12] or mouse [21]. Plasma corticosterone concentrations increased following exposure to this stress and were significantly higher in oxytocin gene deletion (OTKO) than wild type (WT) female mice [21]. Genotypic differences in the corticosterone response after shaker stress persisted across all stages of the estrous cycle and after mice were conditioned to repeated shaker stress [21]. However, unlike female mice, OTKO and WT male mice secreted the same amount of corticosterone following exposure to shaker stress [22]. Our studies suggest that the heightened plasma corticosterone concentrations in female, but not male, OTKO mice after exposure to this particular acute psychogenic stress likely reflects heightened activation of the hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal (HPA) axis.

In the first experiment, we measured plasma corticosterone concentrations in OTKO and WT female mice following exposure to another psychogenic stress. Acutely inserting a rectal probe to record body temperature in rodents induces psychogenic stress. The maneuver triggers a rise in corticosterone, which is an index of neuroendocrine activation [for review see ref. 6], and evokes a rise in body temperature, which is referred to as stress induced hyperthermia (SIH). SIH can also be combined with other maneuvers to evoke stress. In the present study we measured corticosterone in OTKO and WT female mice following removal from their home cage, insertion of a rectal probe to measure body temperature and a brief (10 min) transfer to a metabolic cage. We hypothesized that if OTKO female mice manifest heightened plasma corticosterone concentrations after exposure to acute psychogenic stresses, OTKO female mice will release more corticosterone than WT female mice following brief confinement in a metabolic cage.

In a second experiment, we measured corticosterone release following exposure of male and female mice to an acute physical stress, insulin-induced hypoglycemia. A variety of physical stresses, such as administration of the anorexigen cholecystokinin [CCK,20] overnight dehydration [29], or overnight fasting activate OT neurons of the mouse PVN and also release corticosterone. Mantella at al [22] reported that CCK resulted in comparable release of corticosterone in OTKO and WT male mice, but that overnight fasting or fluid deprivation triggered greater corticosterone release in OTKO than WT male mice. However no measures were included to guarantee either comparable dehydration (serum osmolality or sodium) or comparable fasting-induced lowering of plasma glucose at the time corticosterone was measured. In the present study, we administered insulin to OTKO and WT female and male mice and acutely induced an equivalent degree of hypoglycemia, a primarily physical non-psychogenic stress. We sought to determine if the amount of corticosterone released after exposure to the acute physical stress of hypoglycemia will be the same or greater in OTKO versus WT female or male mice.

Materials and methods

Animals

Mice for these studies were derived from the mating of OTKO male mice and heterozygote (HZ) female mice using the line produced by Scott Young [40]. The resulting HZ males and HZ females were crossed to produce a continuous line of OTKO and WT mice that have been housed and bred in the viral free quarters of the University of Pittsburgh Animal Facility under a 12-h light, 12-h dark cycle (lights on at 0700 h). Current mice have been backcrossed for 12 generations into a C57BL/6J background and were age- (9–12 months) and weight-matched at the time of study.

Mice were housed in standard cages in groups of up to 4 animals per cage with free access to water and food (Prolab RMH 3000 5P00, Lab Diet/ Purina). For testing, animals were removed from group housing and acclimated to single housing for a week prior to the test day and remained in single housing throughout the study. Experimental protocols were approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee of the University of Pittsburgh and performed in accordance with the NIH Guidelines for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals. Mice were tested as paired cohorts according to genotype and treatment.

To identify the genotype of each mouse, at one month of age DNA from a mouse tail sample was extracted and prepared for polymerase chain reaction (PCR) using adaptations [2] to methods previously published [40]. Pairs of primers were designed for PCR that either detect the wild-type allele (OT, 332 bp) or the mutant allele (neomycin resistance cassette, 430 bp).

SIH and Corticosterone Release after Transfer to a Metabolic Cage

Female mice (6 WT and 8 OTKO) were single-housed for 7 days prior to the start of this study. Methods for measuring core body temperature in single housed mice before and after an acute stress have been published previously and applied in these experiments [6,33]. A lubricated thermocouple temperature probe (Omega, Stanford, CT) was inserted to a uniform depth of 2.0 cm into the rectum of the mouse and maintained in place for 10–15 seconds. A temperature reading was recorded to the nearest 0.1 degree. In pilot studies (data not shown) we determined that peak temperature is achieved 10 min after an acute stress and remains stable for 30 min before declining, in agreement with others [6]. Between 1000 and 1100h, rectal temperature was recorded in mice of each genotype before placement in a metabolic cage. After 10 min, mice were removed from the cage and rectal temperature was recorded. Mice were returned to the home cage and rapidly killed 10 min later by scissors decapitation. Trunk blood was obtained to measure corticosterone. Control female mice (3 of each genotype) were handled and killed rapidly by scissors decapitation but no core body temperature was measured nor were the mice placed in a metabolic cage.

Overnight Fasting and Insulin-Induced Hypoglycemia

Female or male mice of both genotypes had food removed at 1700 h the day before an experiment and placed in a new cage with fresh bedding. The change of cage and bedding obviated the possibility that mice may access spilled food that was sequestered in bedding of the home cage prior to removal of the food tray. The next morning at 0900 h mice were injected with regular insulin, 1.0 U per kg body weight i.p. (Sigma, St Louis MO). We studied 8 OTKO and 10 WT male mice and 8 OTKO and 8 WT female mice. Control mice (3 WT and 3OTKO) received saline injection. Before injection a small drop of blood was obtained for glucose measurement by nicking the tail vein. One hour post injection, mice were killed rapidly by scissors decapitation and blood was collected for measurement of glucose and corticosterone.

Hormone Assays

Glucose was measured in whole blood using an Ascensia Contour blood glucose monitoring system and Ascensia Microfill blood glucose test strips (Bayer Health Care, Mishawaka, IN). Corticosterone was measured in plasma using an assay kit from a commercial source (Siemens Medical Solutions Diagnostic, Los Angeles, CA). The range of the assay is 20 to 2000 ng/ml. Trunk blood removed at decapitation was centrifuged at 1500 × g for 10 min, the plasma was separated from the red blood cells, and the plasma was stored frozen at −20 C° until assay.

Statistics

Results are presented as group means ± SE. Plasma corticosterone and blood glucose concentrations were analyzed by analysis of variance (ANOVA). When F ratios indicated a significant effect of the factors of genotype and intervention or an interaction between genotype and intervention, Bonferroni t-tests were used for post hoc comparisons. An effect was considered significant when P < 0.05.

Results

SIH and Corticosterone Release after Transfer to a Metabolic Cage

Basal core body temperature prior to transfer to a metabolic cage was not different between OTKO (37.4 ± 0.2° C) and WT (37.4 ± 0.2° C) female mice. After confinement in the metabolic cage for 10 min, there was a significant rise in body temperature from baseline (P < 0.01) but the change in body temperature ((Δ T) in OTKO (Δ T = 1.0 ± 0.1° C) versus WT (Δ T = 1.0 ± 0.2° C) female mice was not significantly different.

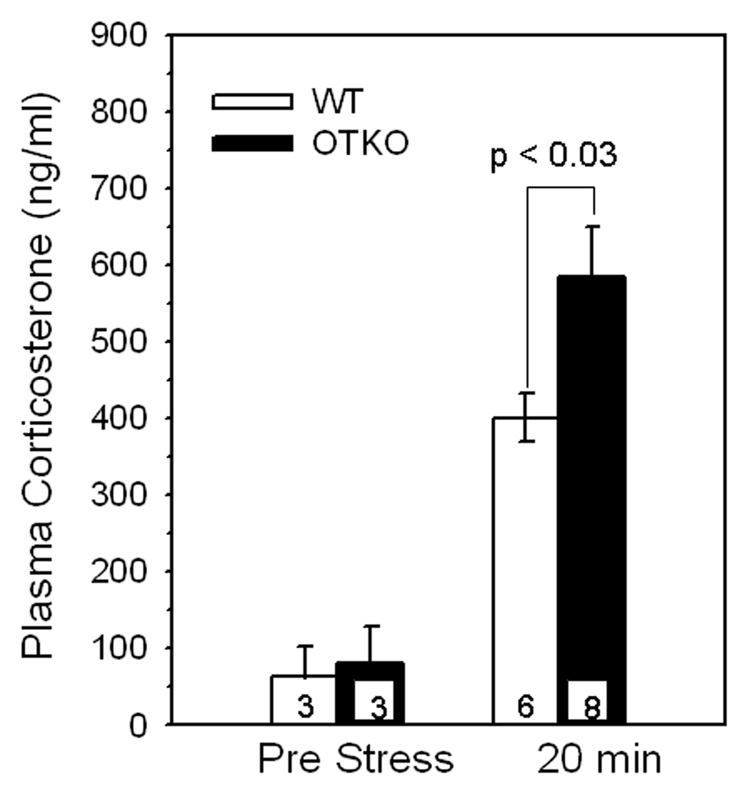

Basal plasma corticosterone levels were not different between control OTKO (80 ± 48 ng/ml) and WT (65 ± 38 ng/m) female mice, Fig 1. Plasma corticosterone concentration measured 10 min after removal of mice from a 10 min confinement in a metabolic cage was significantly higher in OTKO (P = 0.0002) and WT (P = 0.001) mice than in non stressed mice. However the elevation in corticosterone was significantly greater in OTKO (584 ± 65 ng/ml) than WT (401 ± 31 ng/ml) female mice P <0.03, Fig 1.

Figure 1.

Mean ± SEM plasma corticosterone concentrations in OT gene deletion (OTKO) and wild type (WT) female mice before and after manipulation to measure rectal temperature and transfer to a metabolic cage. Plasma corticosterone concentration measured 10 min after removal of mice from a 10 min confinement in a metabolic cage (e.g., 20 min after the transfer to the cage and 10 min after rectal temperature recording) was significantly higher, P < 0.03, in OTKO than WT female mice.

Overnight Fasting and Insulin-Induced Hypoglycemia

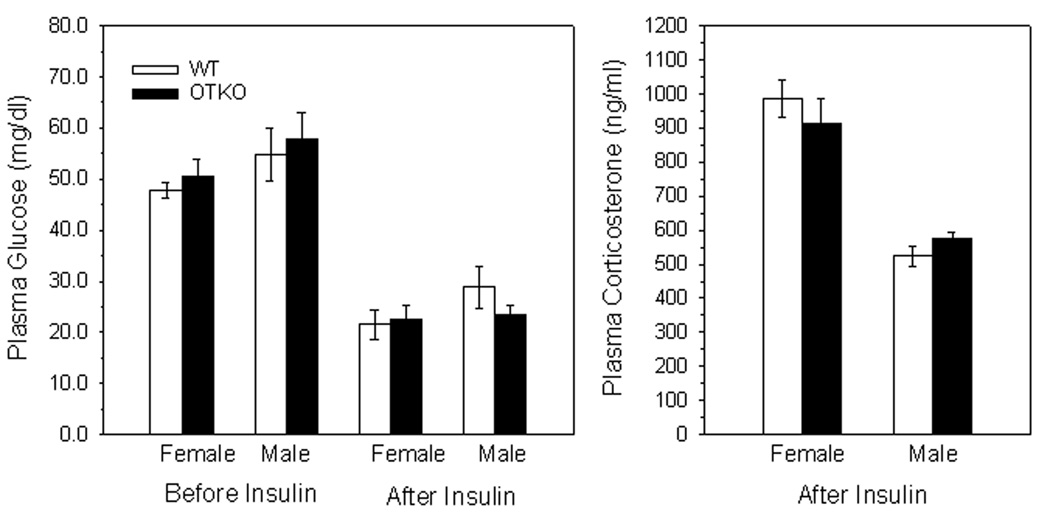

Blood glucose concentrations after overnight fasting were not different between genotypes in female (OTKO, 51 ± 3.5 versus WT, 48 ± 1.5 mg/dl) or male mice (OTKO, 58 ± 2.5 versus WT, 55 ± 5 mg/dl), Fig 2. Following insulin injection, blood glucose declined to the same degree in mice of both genotypes (female: OTKO, 23 ± 3.0 versus WT, 22 ± 3.0 mg/dl and male: OTKO, 24 ± 2.0 versus WT, 29 ± 4.0 mg/dl, Fig 2). Hypoglycemia was associated with heightened plasma corticosterone concentrations that were not different between genotypes in female (OTKO, 912 ± 75 versus WT, 985 ± 55 ng/ml) or male mice (OTKO, 575 ± 17 versus WT, 524 ± 30 ng/ml), Fig 2, but were significantly higher in female than male mice, p < 0.05.

Figure 2.

Left Panel. Blood glucose concentrations before and one hr after peripheral i.p. Injection of 1.0 U/kg body weight of regular insulin in overnight-fasted OT gene deletion (OTKO) or wild type (WT) female or male mice. Right Panel. Plasma corticosterone concentrations in the same mice one hr after insulin injection. Data are mean ± SEM.

Blood glucose concentrations following an overnight fast in saline-treated control mice (N = 3 per genotype) were not different between genotypes (OTKO, 57 ± 1 versus WT, 54 ± 6 mg/dl) and did not change one-hour post saline injection (OTKO, 59 ± 10 versus WT, 57 ± 2 mg/dl). Corticosterone levels one hour after saline injection were not different between OTKO (587 ± 81 ng/ml) and WT (406 ± 172 ng/ml) mice.

Discussion

We conclude from the present study that following exposure to an acute psychogenic stress such as transfer to a metabolic cage and rectal temperature recording, OTKO female mice had higher plasma corticosterone concentrations than WT female mice. This finding is in keeping with previously reported heightened corticosterone concentrations in OTKO versus WT female mice after exposure to platform shaker, a predominantly psychogenic stress [3,21]. In contrast, corticosterone release was not different between OTKO and WT female mice if the mice were exposed to a physical stress, acute hypoglycemia induced by insulin. Thus the type of stress, anticipatory versus non anticipatory, differentially modulates the magnitude of plasma corticosterone concentration in OTKO female mice. On the other hand OTKO male mice did not manifest higher plasma corticosterone concentrations than WT male mice following exposure to a psychogenic stress such as platform shaker [22] or to the acute onset of a physical stress such as hypoglycemia induced by insulin.

In addition to modulating neuroendocrine responses to psychogenic stress, central OT is also believed to modulate emotional responses in rodents. OT administration into the brain, especially into the amygdala, is anxiolytic and anxioloysis is facilitated by estrogen [5,23,35]. There are also differences in the emotional phenotype of male versus female OTKO mice. OTKO female, but not male, mice manifest more anxiety-related behavior than WT cohorts in an elevated plus maze (EPM) test and centrally administered OT will lessen anxiety in OTKO female mice [19]. On the other hand OTKO male mice manifest less fearful behavior in a test of anxiety such as the EPM [19,37] and enhanced aggression in a resident intruder test [37] compared to WT cohorts. The cumulative findings suggest sex differences in both the emotional and stress responses of OTKO mice.

The findings in this study complement the findings by a variety of laboratories that central administration of OT, especially into the amygdala, blunts stress activation of the HPA axis and an OTR antagonist has the opposite effect. [24,25,35,36]. The amygdala plays an important role in the response to anxiety and psychogenic stress. OT binding sites have been identified in the central and medial nuclei and to a lesser extent the basal medial nucleus [7,11,17,31,34]. Electrical recordings from the amygdala of rats showed that iontophoretic application of OT excited 50% of neurons studied [17]. The central and medial amygdalae are extensions of the BNST, with which there are extensive reciprocal innervations such that the unit (BNST, central and medial amygdala) has been termed the “extended amygdala” [1]. OT binding sites in both the BNST and the central and medial amygdala vary both with the level of gonadal steroids, especially estrogen [8,18,27,32] and with the reproductive status of the animal [14,15,38.39].

In vitro work by Huber et al [13] suggests that OT and AVP work in opposite ways to control activation in the central amygdala. While AVP promotes anxiety and stress hyper responsiveness, OT is anxiolytic and fosters stress hypo responsiveness. The source of OT is believed to derive from OT projections that arise in the PVN and project to the amygdala [13]. OT acts upon gamma aminobutyric acid (GABA) synapses within the central amygdala to enhance GABA tone and inhibit AVP neurons. Thus OT is positioned to modulate output from the central amygdala and in turn autonomic and neuroendocrine responses (corticosterone) response to anxiety and psychogenic stress.

SIH is an excellent way to measure anxiolysis or stress hypo responsiveness and has been extensively used to assess the anxiolytic properties of pharmacological agents. However SIH cannot readily identify stress hyper responsiveness or heightened anxiety [6]. As such a change in core body temperature has not been useful to determine if heightened stress or anxiety exist in mutant versus WT mice. We recently reported our experience using SIH as an index of stress hyper responsiveness in OTKO and WT female or male mice [4]. We did not consistently identify greater temperature increases in OTKO male or female mice compared to WT mice, although in a pilot study we had previously reported heightened temperature increases in a small number (5 of each genotype ) of female mice [3]. However, OTKO mice released significantly more corticosterone than WT mice following this maneuver, despite equivalent rises in core body temperature following transfer to a metabolic cage. Thus the heightened neuroendocrine response of OTKO female mice after exposure to an acute psychogenic stress can be reliably identified by measurements of corticosterone, but not SIH.

Greater plasma corticosterone concentrations in OTKO than WT female mice are associated with exposure to acute psychogenic but not the acute physical stress of hypoglycemia. Although various stress paradigms have both physical and psychogenic component, animals do not anticipate rapid induction of hypoglycemia that follows an insulin injection. This contrasts with most other forms of physical stress in which the animal anticipates the stress (cold exposure, pain, heat) or the stress is prolonged (overnight dehydration or overnight fasting). Moreover, the degree of hypoglycemia can be accurately quantified by measuring blood glucose. In the present study OTKO and WT male and female mice achieved equivalent blood glucose concentrations after an overnight fast. Following saline injection blood glucose did not decline further in either OTKO or WT mice. Insulin treatment was followed by a significant but equivalent hypoglycemic response in OTKO and WT mice. The corticosterone concentration in saline-treated mice was greater than typical baseline values obtained in mice with ad libitum access to food. Thus the elevation in corticosterone reflects the impact of the overnight fast. Corticosterone concentrations in OTKO and WT mice were thus measured at a time that mice were documented to have equal effects from an overnight fast. In a prior study in which we measured corticosterone after overnight fasting, blood glucose was not measured [22]. Thus a prior report of higher corticosterone in OTKO versus WT male mice may not be to genotypic differences but rather an unequal degree of hypoglycemia following an overnight fast. In the present study overnight fasted mice that received insulin had a further reduction in blood glucose. The severe hypoglycemia that ensued was equal between genotypes and served as an acute stimulus to the release of corticosterone. Corticosterone concentrations one hour after insulin injection and at the time of severe hypoglycemia were not different between genotypes in either male or female mice. Thus OTKO mice do not have higher levels of corticosterone than WT mice following a controlled overnight fast or following insulin-induced hypoglycemia. It is important to note that the corticosterone response to insulin treatment was significantly greater in female mice than male mice of both genotypes. This latter observation agrees with other reports that stress generally causes greater corticosterone release in female than male rodents [summarized in ref. 27].

In summary a deficiency of OT in female mice manifests as higher plasma corticosterone concentrations following exposure to several psychogenic stresses (e.g., shaker stress, thermal probe, and changing environment) but not the physical stress of hypoglycemia induced by insulin. Although higher corticosterone concentrations in these settings have been observed in OTKO female mice, higher corticosterone responses have not yet been reported in OTKO male mice. Future studies in which OTKO mice are exposed to additional psychogenic stresses will help determine if the heightened corticosterone response to psychogenic stress is restricted to OTKO female mice.

Acknowledgements

Supported by grant HD044898 from the National Institutes of Health (JAA)

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Alheid GF, de Olmos JS, Beltramino CA. Amygdala and extended amygdala. In: Paxinos G, editor. The Rat Nervous System. 2nd edition. New York: Academic Press; 1995. pp. 495–578. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Amico JA, Morris M, Vollmer RR. Mice deficient in oxytocin manifest increased saline consumption following overnight fluid deprivation. Am J Physiol Regul Integr Comp Physiol. 2001;281:R1368–R1373. doi: 10.1152/ajpregu.2001.281.5.R1368. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Amico JA, Mantella RC, Vollmer RR, Li X. Anxiety and stress responses in female oxytocin deficient mice. J Neuroendocrinol. 2004;16:1–6. doi: 10.1111/j.0953-8194.2004.01161.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Amico JA JA, Miedlar JA, Cai HM, Vollmer RR. Oxytocin knockout mice: a model for studying stress-related and ingestive behaviors. In: Landgraf R, Neumann ID, editors. Vasopressin and Oxytocin: From Gene to Behavior. Progress in Brain Research. Vol. 170. Amsterdam: Elsevier; 2008. pp. 53–64. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bale TL, Davis AM, Auger AP, Dorsa DM, McCarthy MM. CNS region-specific oxytocin receptor expression: importance in regulation of anxiety and sex behavior. J Neurosci. 2001;21:2546–2552. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.21-07-02546.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bouwknecht JA, Olivier B, Paylor RE. The stress-induced hyperthermia paradigm as a physiological animal model for anxiety: A review of pharmacological and genetic studies in the mouse. Neurosci. & Biobehav Rev. 2007;3:41–59. doi: 10.1016/j.neubiorev.2006.02.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Condés-Lara M, Veinante P, Rabai M, Freund-Mercier MJ. Correlation between oxytocin neuronal sensitivity and oxytocin binding sites in the amygdala of the rat: electrophysiological and histoautoradiographic study. Brain Res. 1994;637:277–286. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(94)91245-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.de Kloet ER, Voorhuis DAM, Boschma Y, Eland J. Estradiol modulates density of putative ‘oxytocin receptors’ in discrete rat brain regions. Neuroendocrinology. 1986;44:415–421. doi: 10.1159/000124680. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ferguson JN, Young LJ, Hearn EF, Matzuk MM, Insel TR. Social amnesia in mice lacking the oxytocin gene. Nature Genetics. 2000;25:284–288. doi: 10.1038/77040. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Ferguson JN, Aldag JM, Insel TR, Young LJ. Oxytocin in the medial amygdala is essential for social recognition in the mouse. J Neurosci. 2001;21:8278–8285. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.21-20-08278.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Freund-Mercier MJ, Stoeckel ME, Palacios JM, Pazos A, Reichhart JM, Porte A, Richard P. Pharmacological characteristics and anatomical distribution of [3H]-oxytocin binding sites in the Wistar rat brain studied by autoradiography. Neuroscience. 1987;20:599–614. doi: 10.1016/0306-4522(87)90113-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hashiguchi H, Ye SH, Morris M, Alexander N. Single and repeated environmental stress: effect on plasma oxytocin, corticosterone, catecholamines, and behavior. Physiol Behav. 1997;61:731–736. doi: 10.1016/s0031-9384(96)00527-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Huber D, Veinante P, Stoop R. Vasopressin and oxytocin excite distinct neuronal populations in the central amygdala. Science. 2005;308:245–248. doi: 10.1126/science.1105636. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ingram CD, Wakerley JB. Post-partum increases in oxytocin-induced excitation of neurons in the bed nuclei of the stria terminalis n vitro. Brain Res. 1993;602:325–330. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(93)90697-l. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Insel TR. Regional changes in brain oxytocin receptors postpartum: time-course and relationship to maternal behaviour. J Neuroendocrinol. 1990;2:539–545. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2826.1990.tb00445.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Insel TR. Oxytocin-a neuropeptide for affiliation: evidence from behavioral, receptor autoradiographic, and comparative studies. Psychoneuroendocrinol. 1992;17:3–35. doi: 10.1016/0306-4530(92)90073-g. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Krémarik P, Freund-Mercier MJ, Stoeckel ME. Histoautoradiographic detection of oxytocin- and vasopressin-binding sites in the telencephalon of the rat. J Comp Neurol. 1993;333:343–359. doi: 10.1002/cne.903330304. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Krémarik P, Freund-Mercier MJ, Stoeckel ME. Estrogen-sensitive oxytocin binding sites are differently regulated by progesterone in the telencephalon and the hypothalamus of the rat. J Neuroendocrinol. 1995;7:281–289. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2826.1995.tb00759.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Mantella RC, Vollmer RR, Li X, Amico JA. Female oxytocin-deficient mice display enhanced anxiety-related behavior. Endocrinology. 2003;144:2291–2296. doi: 10.1210/en.2002-0197. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Mantella RC, Rinaman L, Vollmer RR, Amico JA. Cholecystokinin and D-fenfluramine inhibit food intake in oxytocin deficient mice. Am J Physiol. Regul, Integr, Comp Physiol. 2003;285:R1037–R1045. doi: 10.1152/ajpregu.00383.2002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Mantella RC, Vollmer RR, Rinaman L, Li X, Amico JA. Enhanced corticosterone concentrations and attenuated Fos expression in the medial amygdala of female oxytocin knockout mice exposed to psychogenic stress. Am J Physiol Regul Integr Comp Physiol. 2004;287:R1494–R1504. doi: 10.1152/ajpregu.00387.2004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Mantella RC, Vollmer RR, Amico JA. Corticosterone release is heightened in food or water deprived oxytocin deficient male mice. Brain Res. 2005;1058:56–61. doi: 10.1016/j.brainres.2005.07.062. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.McCarthy MM, McDonald CH, Brooks PJ, Goldman D. An anxiolytic action of oxytocin is enhanced by estrogen in the mouse. Physiol Behav. 1996;60:1209–1215. doi: 10.1016/s0031-9384(96)00212-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Neumann ID, Kromer SA, Toschi N, Ebner K. Brain oxytocin inhibits the reactivity of the hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal axis in male rats: involvement of hypothalamic and limbic brain regions. Regul Pep. 2000;96:31–38. doi: 10.1016/s0167-0115(00)00197-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Neumann ID, Torner L, Wigger A. Brain oxytocin: differential inhibition of neuroendocrine stress responses and anxiety-related behaviour in virgin, pregnant and lactating rats. Neuroscience. 2000;95:567–575. doi: 10.1016/s0306-4522(99)00433-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Nishimori K, Young LJ, Guo Q, Wang Z, Insel TR, Matzuk MM. Oxytocin is required for nursing but is not essential for parturition or reproductive behavior. Proc Nat Acad Sci USA. 1996;93:11699–11704. doi: 10.1073/pnas.93.21.11699. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Ochedalski T, Subburaju S, Wynn PC, Aguilera G. Interactions between oestrogen and oxytocin on the hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal axis activity. J Neuroendocrinol. 2007;19:189–197. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2826.2006.01525.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Patchev VK, Schlosser SF, Hassan AHS, Almeida OFX. Oxytocin binding sites in rat limbic and hypothalamic structures: site specific modulation by adrenal and gonadal steroids. Neuroscience. 1993;57:537–543. doi: 10.1016/0306-4522(93)90003-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Pedersen CA, Prange AJ., Jr Induction of maternal behavior in virgin rats after intra-cerebroventricular administration of oxytocin. Proc Nat Acad Sci USA. 1979;76:6661–6665. doi: 10.1073/pnas.76.12.6661. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Rinaman L, Volmer RR, Karam JR, Li X, Amico JA. Attenuation of dehydration anorexia in oxytocin deficient mice. Am J Physiol. Regulatory, Integrative, Comp Physiol. 2005;288:R1791–R1799. doi: 10.1152/ajpregu.00860.2004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Takayanagi Y, Yoshida M, Bielsky IF, Ross HE, Kawamata M, Onaka T, Yanagisawa T, Kimura T, Matzuk MM, Young LJ, Nishimori K. Pervasive social deficits, but normal parturition, in oxytocin receptor-deficient mice. Proc Nat Acad Sci USA. 2005;102:16096–16101. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0505312102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Terenzi MG, Ingram CD. Oxytocin-induced excitation of neurons in the rat central and medial amygdaloid nuclei. Neuroscience. 2005;134:345–354. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroscience.2005.04.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Tribollet E, Audigier S, Dubois-Dauphine M, Dreifuss JJ. Gonadal steroid regulate oxytocin receptors in the brain of male and female rats. Brain Res. 1990;811:129–140. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(90)90232-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Van der Heyden JA, Zethof TJ, Olivier B. Stress-induced hyperthermia in singly housed mice. Physiol. Behav. 1997;62:463–470. doi: 10.1016/s0031-9384(97)00157-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Veinante P, Freund-Mercier MJ. Distribution of oxytocin- and vasopressin-binding sites in the rat extended amygdala: a histoautoradiographic study. J Comp Neurol. 1997;383:305–325. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Windle RJ, Shanks N, Lightman SL, Ingram CD. Central oxytocin administration reduces stress-induced corticosterone release and anxiety behavior in rats. Endocrinology. 1997;138:2829–2834. doi: 10.1210/endo.138.7.5255. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Windle RJ, Kershaw YM, Shanks N, Wood SA, Lightman SL, Ingram CD. Oxytocin attenuates stress-induced cfos mRNA expression in specific forebrain regions associated with modulation of hypothalamo-pituitary-adrenal activity. J Neurosci. 2004;24:2974–2982. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.3432-03.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Winslow JT, Hearn EF, Ferguson JN, Young LJ, Matzuk MM, Insel TR. Infant vocalization, adult aggression, and fear behavior of an oxytocin null mutant mouse. Horm Behav. 2000;37:145–155. doi: 10.1006/hbeh.1999.1566. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Young LJ, Muns S, Wang Z, Insel TR. Changes in oxytocin receptor mRNA in rat brain during pregnancy and the effects of estrogen and interleukin-6. J Neuroendocrinol. 1997;9:859–865. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2826.1997.00654.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Young WS, 3rd, Shepard E, Amico JA, Hennighausen L, Wagner K, LaMarca ME, McKinney C, Ginns EI. Deficiency in mouse oxytocin prevents milk ejection, but not fertility or parturition. J Neuroendocrinol. 1996;8:847–853. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2826.1996.05266.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]