Abstract

Within the mouse endometrium, secreted phosphoprotein 1 gene expression is mainly expressed in the luminal epithelium and some macrophages around the onset of implantation. However, during the progression of decidualization it is expressed mainly in the mesometrial decidua. To date, the precise cell types responsible for the expression in the mesometrial decidua has not been absolutely identified. The goal of the present study was to assess the expression of secreted phosphoprotein 1 in uteri of pregnant mice (decidua) during the progression of decidualization and compared it to those undergoing artificially-induced decidualization (deciduoma). Significantly (P< 0.05) greater steady-state levels of secreted phosphoprotein 1 mRNA were seen in the decidua compared to deciduoma. Further, in the decidua, the majority of the secreted phosphoprotein 1 protein (SPP1) was localized within a subpopulation of granulated uterine natural killer (uNK) cells but not co-localized to their granules. However, in addition to being localized to uNK cells, SPP1 protein was also detected in another cell type(s) that were not EGF-like containing mucin-like hormone receptor-like sequence 1 protein (EMR1)-positive immune cells which are known to be present in the uterus at this time. Finally, decidual SPP1 expression dramatically decreased in uteri of interleukin-15-deficient mice which lack uNK cells. In conclusion, SPP1 expression is greater in the mouse decidua compared to the deciduoma after the onset of implantation during the progression of decidualization. Finally, uNK cells were found to be the major source of SPP1 in the pregnant uterus during decidualization. SPP1 might play a key role in uNK killer cell functions in the uterus during decidualization.

INTRODUCTION

In most mammals, implantation of the conceptus begins with the attachment of the embryo to the uterine wall and ends in the formation of the definitive placenta. One of the first major processes that begins to occur in the rodent uterus after the onset of implantation is the proliferation then differentiation of the endometrial fibroblast-like cells into large polyploid decidual cells (Das & Martin, 1978, Lejeune et al., 1982). This process, called decidualization, results in the formation of tissue that is referred to as the decidua and occurs in response to an implantation stimulus provided by the implanting blastocyst in rodents. However, due to an observation first reported almost a century ago in the guinea-pig (Loeb, 1908), then in several other species (Krehbiel, 1937), molecular signals from the conceptus appear not to be required for decidualization to occur. This is because the uterus can undergo decidualization in response to an artificial-stimulus such as an intra-luminal injection of sesame oil (Finn & Martin, 1972) or transfer of blastocyst-sized agarose beads (Sakoff & Murdoch, 1994) into ovariectomized hormonally-sensitized or pseudopregnant animals (Finn & Martin, 1974). In order to discern the tissue that forms in response to artificial-stimuli from the one that forms in response to an implanting blastocyst, we refer to it as a deciduoma (Krehbiel, 1937).

Secreted phosphoprotein 1 gene (Spp1, also referred to as osteopontin) encodes a 44 kDa protein and is expressed in several tissue types. Spp1 expression is found in many types of cells and might play physiological and pathological roles (Okamoto, 2006). Studies examining the role of Spp1 in early mouse development revealed it is expressed in the uterus during pregnancy (Nomura et al., 1988, Waterhouse et al., 1992). In this study, and one that appeared soon after (Waterhouse et al., 1992) it was speculated that Spp1 expression was localized to immune cells at the onset of implantation. This speculation was confirmed in a recent study which shows that Spp1 expression occurs in macrophages in the mouse uterus at the onset of implantation (White et al., 2006). After the onset of implantation, during the progression of decidualization, Spp1 expression is found in the mesometrial decidua. (Nomura et al., 1988, Waterhouse et al., 1992). However, to our knowledge, work providing the precise identity of the cells expressing it has not been reported. Therefore, the goal of the present study was to examine Spp1 expression during the progression of decidualization in the mouse. Further, we determined if the conceptus possibly influences uterine Spp1 expression during the progression of decidualization by comparing its expression in pregnant uteri (conceptus present) to those undergoing artificially-induced decidualization (conceptus absent).

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Animals

All procedures involving mice were approved by the Southern Illinois University Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee. Unless otherwise noted, experiments were carried out using 12–16 wk old CD1 mice (Charles River Breeding Laboratories, Wilmington, MA, USA). In some cases, mice with a targeted deletion of the Il15 gene (Il15−/−; C57BL/6-Il15tm1Imx) plus their wild-type (Il15+/+; C57BL/6-Tac) controls (National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases Emerging Models Program, Taconic Farms, Germantown, NY, USA) were used. Females were placed with fertile males and the morning a vaginal plug was detected was considered to be Day 0.5 of pregnancy. Mice were killed at 09:00 h on Days 6.5, 7.5 or 8.5 of pregnancy which approximately corresponds to Days 2, 3 and 4 after the onset of decidualization, respectively (Fig 1). Segments of uteri containing implanting conceptuses, implantation sites (IS), were dissected and then used for either histological or for reverse transcription-real-time-polymerase chain reaction (RT-real-time-PCR) experiments. For samples used in the later, the conceptuses were carefully dissected out of the IS tissues as described elsewhere (Nagy et al., 2003). To generate artificially-induced deciduomas, ovariectomized CD1 mice were treated exactly as described previously (Bany & Cross, 2006). Briefly, after mice were allowed a 1 wk recovery after ovariectomy, they were injected subcutaneously with a regimen of estradiol-17β and/or progesterone (Sigma, St Louis, MO, USA) at 09:00 hrs as outlined in figure 1. This regimen serves to adequately sensitize the uterus for an artificial deciduogenic stimulus. Once sensitized, an intra-luminal injection of 10–15 μl of sesame oil (Sigma, St Louis, MO, USA) was used as an artificial deciduogenic stimulus between 11:00–13:00 h and mice were maintained on daily subcutaneous injections (09:00 h) of progesterone thereafter until killed (Fig 1). Mice were killed at approximately 48, 72 or 96 h after artificially-inducing decidualization, which correspond to Days 2, 3 and 4 after the onset of decidualization, respectively. The resulting uterine horns undergoing artificially-induced decidualization, called stimulated (ST) uterine horns, were dissected and processed for histological or RT-real-time-PCR work.

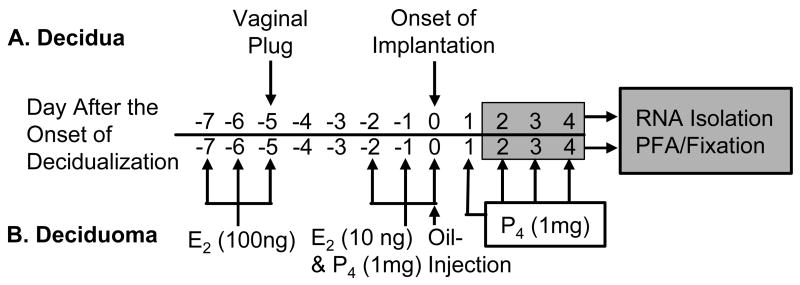

Figure 1.

Time-line showing the preparation and collection of mouse uteri during decidualization. Decidual tissue samples were collected on Days 6.5, 7.5 and 8.5 of pregnancy, corresponding to Days 2, 3 and 4 after the onset of decidualization, respectively (A). Deciduomal tissue samples from ovariectomized mice treated with estradiol-17β (E2) and/or progesterone (P4) were collected on Days 2, 3 and 4 after the onset of decidualization in response to an intra-luminal injection of sesame oil (B).

RT-Real-Time-PCR

Total RNA was extracted from the uterine tissue using TRIzol® reagent (Invitrogen Corp., Grand Island, NY, USA) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. The method of RT-real-time-PCR was then used to evaluate the relative steady-state levels of Spp1 mRNA in the total RNA samples. Briefly, total RNA (1 μg) was reverse-transcribed into cDNA using ImpromII reverse transcriptase (Promega, Madison, WI, USA) according to manufacturer’s instructions. Each reverse transcription reaction was carried out in a 20 uL volume and contained downstream primers for both 18 S rRNA and Spp1 mRNA (Integrated DNA Technologies Inc., Coralville, IA, USA). Real-time-PCR for 18 S rRNA and Spp1 mRNA was then carried out using IQ SYBR Green Supermix (BioRAD, Hercules, CA, USA) as suggested by the manufacturer. Briefly, 2 μl (for Spp1 mRNA) or 2 μl of a 50-fold dilution (for 18 S rRNA) of the reverse transcription reactions were combined with 13 ul of the supermix, 1 μl of each upstream and downstream primers, and 9 μl of RNase-free water. These reaction mixes, in 96-well plates (BioRAD, Hercules, CA, USA), were then placed in an iCycler Thermal Cycler coupled to a MyIQ real-time detection system (BioRAD, Hercules, CA, USA). Primer sequences for Spp1 (upstream 5′-AGCAAGAAACTCTTCCAAGCAA-3′; downstream 5′-GTGAGATTCGTCAGATTCATCCG-3′) and 18 S rRNA (upstream 5′-TCAAGAACGAAAGTCGGAGGTT-3′; downstream 5′-GGACATCTAAGGGCATCACAG-3′) were obtained from Primer Bank Database (Wang & Seed, 2003) and designed using software, respectively. The conditions of the RT-real-time-PCR was 40 repetitive cycles of melting (94°), annealing (61.8°) and extension (72°) for 15, 15 and 30 sec respectively. The cycle threshold (Ct) values provided by the MyIQ software were used to calculate the relative steady-state levels of Spp1 mRNA in the samples normalized to 18 S rRNA. Briefly, for each of the four independent samples from each time point and tissue type, the ΔCt values (CtSPP1-CtrRNA) were calculated where CtSpp1 and CtrRNA are the Ct values for Spp1 mRNA and 18S rRNA respectively. Next, the average ΔCt for the values found for the deciduomas on Day 2 after the onset of decidualization was subtracted from all individual ΔCt values to normalize them to that tissue type and time point. Finally, the normalized ΔCt values for each of the samples were then transformed using the following: 2−(ΔCt). This data was then analyzed using a two-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) to determine overall effects of time and tissue source. This was followed by the use of Duncan multiple range test to determine differences between means for each given day after the onset of decidualization. At the end of the RT-real-time-PCR, a melt curve confirmed the existence of a single amplicon as did agarose gel electrophoresis (data not shown). For further verification, the amplicons were also sequenced (University of Illinois Urbana-Champaign Core Sequencing Facility, Urbana-Champaign, IL, USA).

SPP 1 and uNK Cell Double-fluorescent Staining

Dolichos biflorus agglutinin (DBA) lectin histochemistry can be used to identify uNK cells in mouse uterine sections (Paffaro et al., 2003). Combining this histochemical technique with immunofluorescence, we co-localized uNK cells and SPP1 protein within uterine cross-sections from 4–7 independent samples per time sampling. After both perfusion and immersion fixation as previously described (Herington & Bany, 2006), the tissue was embedded in paraffin blocks using routine histological methods. Uterine cross-sections (5 μm) were mounted onto silanized glass slides and stored until use. For double-fluorescent staining, the sections were deparaffinized in xylene (Fisher Scientific, Pittsburg, PA, USA) hydrated in decreasing concentrations of ethanol (MIDSCI, St. Louis, MO, USA), and then washed in phosphate buffer saline (PBS). The slides were then placed in blocking solution containing 2% (w/v) normal donkey serum (Biomeda Corporation, Foster City, CA, USA) in PBS containing 0.05% Tween-20 (DS-PBST) for 1 h. This was followed by incubation of the sections overnight in 0.5 μg/ml anti-SPP1 IgG (Assay Design Inc., Ann Arbor, MI, USA) in DS-PBST at 4°C. After washing in PBS containing 0.05% Tween-20 (PBST), the sections were incubated for 3 h in DS-PBST containing both 7.5 μg/ml donkey anti-rabbit IgG-cyanine 3 (Cy3) conjugate (Jackson Immuno Research Laboratories, Inc., West Grove, PA, USA) and 62.5 ug/ml DBA lectin-fluorescein conjugate (Biomeda Corporation, Foster City, CA, USA) at room temperature. After washing with PBST, the sections were incubated for 20 min in PBS containing 5 μg/ml 4’,6-diamidino-2-phenylindole, dihydrochloride (DAPI; Pierce Biotechnology, Rockford, IL, USA) to stain nuclei. To reduce lipofuscin-like autofluorescence, the sections were then incubated in a cupric sulfate solution as previously described (Schnell et al., 1999). Finally, after washing in PBS, coverslips were mounted over the sections using Fluoromount-G™ mounting medium (Southern Biotechnology Associates Inc., Birmingham, CA, USA). Cy3 and fluorescein fluorescent signals were not detected in control sections incubated in DS-PBST containing 0.5 ug/ml rabbit IgG (in place of anti-SSP1 IgG), DBA lectin (as above) and 0.1 M N-acetyl-D-galactosamine (Sigma, St Louis, MO, USA ) competitor (data not shown).

All microscopy work was conducted using a Leica MZFLIII stereomicroscope (North Central Instruments, Maryland Heights, MO, USA) or Nikon light/fluorescence microscope (Hitschfel Instruments Inc., St. Louis, MO, USA), each equipped with Retiga digital cameras (QImaging, Burnaby, Canada). Images were captured using QCapture Pro software (QImaging, Burnaby, Canada). Only cells in the cross-sections that had DAPI-stained nuclei within them were counted and used in the analysis of DBA lectin and/or SPP1 double-fluorescence in the entire mesometrial region of deciduomas and deciduas. DBA lectin-positive uNK cells were classified according to their stage of maturation (Paffaro et al., 2003) as types I–IV, based on the localization of DBA lectin binding, presence or absence of granules, cell size plus shape and nuclear morphology exactly as previously described (Herington & Bany, 2006). The types I, II, III and IV represent immature, intermediate, fully mature and senescent uNK cells, respectively. An ANOVA on arcsine transformed data was performed to determine if the percentage of total cells in the entire mesometrial area that were SPP1-negative plus DBA lectin-positive, SPP1-positive plus DBA lectin-positive and SPP1-posititive plus DBA lectin-negative were different between the deciduomas and deciduas on each day examined. Similarly, a one-way ANOVA on arcsine transformed data was also used to determine if the proportion of SPP1-positive cells that stained negative for DBA lectin were different between the two tissue types on each day examined.

SPP 1 and EMR1 Double-Immunofluorescent Staining

EGF-like containing mucin-like hormone receptor-like sequence 1 protein (EMR1, originally referred to as F4/80) is a membrane protein that is commonly used to localize macrophages within the mouse tissues (Austyn & Gordon, 1981). Although, this protein is also localized to some dendritic cells and eosinophils in other tissues (McGarry & Stewart, 1991, Peters et al., 1996), it has also been the most commonly used marker for localizing macrophages specifically in uterine tissue (De et al., 1991, Hunt, 1994, Pollard et al., 1998, Pollard et al., 1991, Robertson et al., 1999, Tibbetts et al., 1999, White et al., 2006). After using the same antigen retrieval methods described above, sections were blocked with DS-PBST for 1 h. Sections were then incubated overnight in DS-PBST containing 0.5 μg/ml anti-SPP1 IgG (Assay Design Inc., Ann Arbor, MI, USA) and 50 μg/ml rat anti-mouse EMR1 (eBioscience, San Diego, CA, USA) at 4°C. After washing in PBST, the sections were incubated for 3 h in DS-PBST containing 7.5 μg/ml donkey anti-rabbit IgG-Cy3 and anti-rat IgG-fluorescein conjugates (Jackson Immuno Research Laboratories Inc., West Grove, PA, USA) at room temperature. After washing with PBST, the sections were covered in PBS containing DAPI for 20 min to stain the nuclei. Sections were then treated with copper sulfate solution, then coverslips were mounted as described above. Cy3 or fluorescein fluorescent signals were not detected in control sections incubated in DS-PBST containing 0.5 μg/ml normal rabbit and 50 μg/ml normal rat IgG (Sigma, St Louis, MO, USA) in place of the primary antibodies (data not shown).

Statistical Analyses

All statistical analyses described above were carried out using either SAS (SAS Institute Inc., Cary, NC, USA) or SigmaStat (Systat Software Inc., Point Richmond, CA, USA) software.

RESULTS

Steady-State Spp1 mRNA Levels

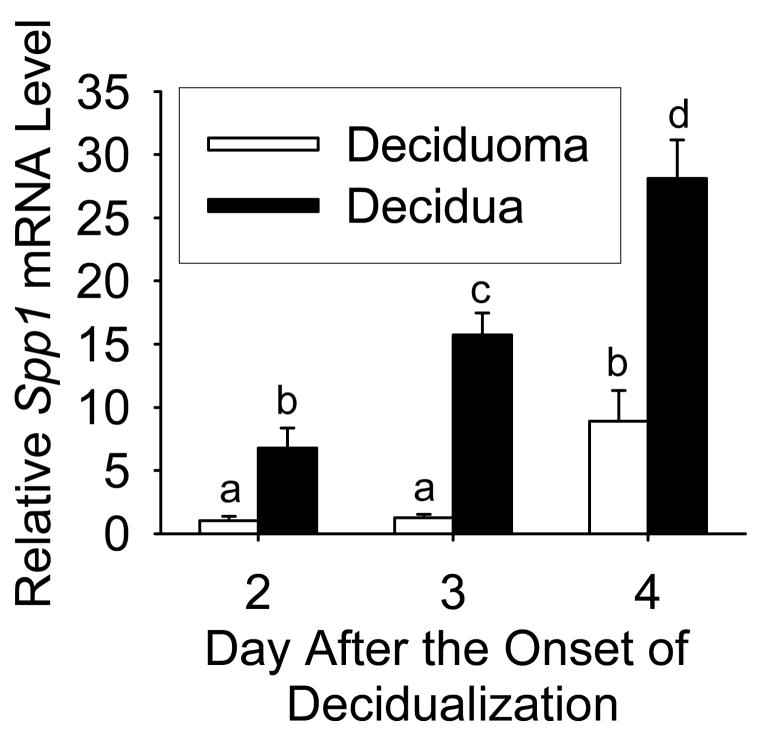

Utilizing the method of RT-real-time-PCR, we measured the relative steady-state level of Spp1 mRNA in the deciduoma and decidua on days 2–4 after the onset of decidualization (Fig 2). Although the levels in the deciduomas were not different between Days 2 and 3, there was a significant (P< 0.05) increase in the steady-state level of Spp1 mRNA on Day 4 after the onset of decidualization. On the other hand, a significant (P< 0.05) increase in the steady-state Spp1 mRNA levels occurred in the decidua between Days 2 to 3 and also Days 3 to 4 after the onset of decidualization. Finally, the steady-state levels of Spp1 mRNA were significantly (P<0.05) greater in the decidua compared to deciduoma by approximately 8-, 17- and 3-fold on Days 2, 3 and 4 after the onset of decidualization, respectively.

Figure 2.

RT-real-time-PCR analysis showing relative steady-state Spp1 mRNA levels in the mouse decidua and deciduoma on Days 2, 3 and 4 after the onset of decidualization. Bars represent the mean (±SEM; N= 4) and those with different letters on a given day are significantly different (P <0.05).

Double-Fluorescent Localization

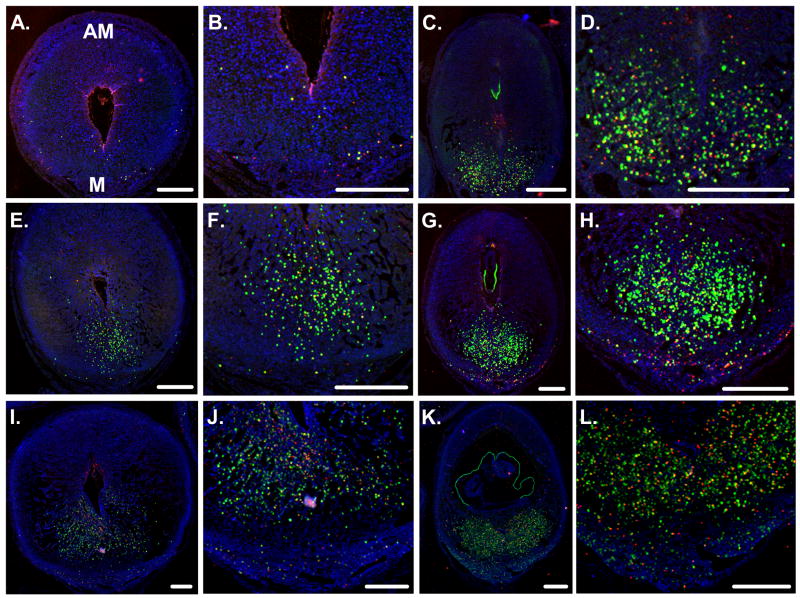

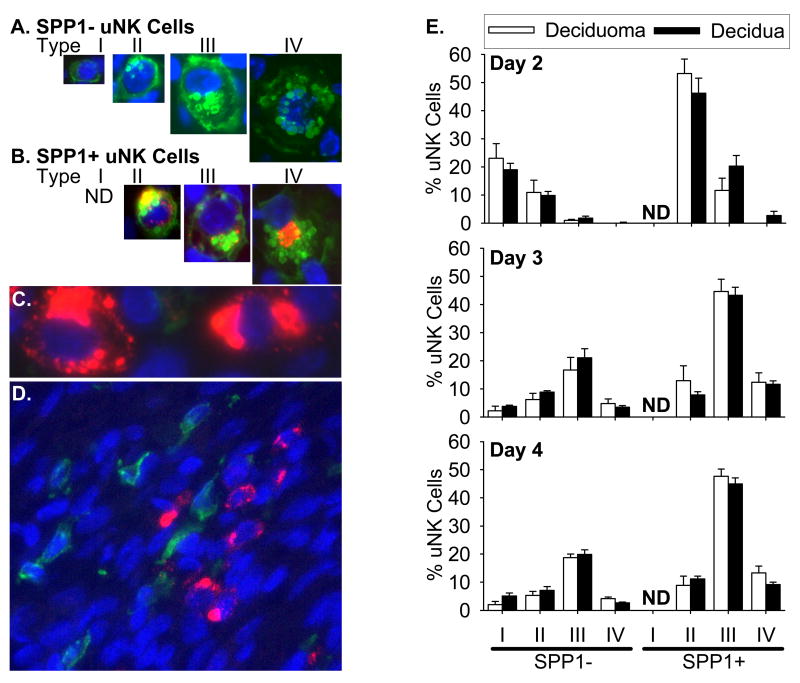

Since the steady-state mRNA levels differed between the deciduas compared to deciduomas, we co-localized SPP1 protein and uNK cells in uterine cross-sections on Days 2, 3 and 4 after the onset of decidualization. On these days, SPP1-positive cells along with DBA lectin-positive uNK cells were localized almost exclusively in the mesometrial region of both deciduomas (Fig 3A, B, E, F, I and J) and deciduas (Fig 3C, D, G, H, K and L). The cells staining positive for DBA lectin and/or SPP1 appeared to increase in number from Days 2 to 4 after the onset of decidualization in both tissues. Although not all uNK cells stained positive for SPP1 (Fig 4A), this protein was localized to a subpopulation of only the granulated (type II, III and IV) forms (Fig 4B). No SPP1-positive immature type I uNK cell could be found. Finally, there was a subset of unknown cells that stained positive for SPP1 but were non-uNK cells (DBA lectin-negative) (Fig 4C). Since EMR1-postive dendritic/macrophage cells have previously been shown to stain positive for SPP1 earlier in pregnancy (White et al., 2006) we next determined whether these unknown cell(s) were EMR1-positive. As shown in figure 4D, the unknown SPP1-positive DBA lectin-negative cells were not EMR1-positive. Finally the localization of the SPP1 protein in all cells, regardless of type, appeared to be intracellular and cytoplasmic in nature. The staining seemed to be localized to either small or large granules and close inspection of the granulated DBA lectin- and SPP1-positive cells using regular fluorescence (Fig. 4B) and confocal (data not shown) microscopy revealed that the SPP1 protein was not localized to the DBA lectin-positive granules.

Figure 3.

Double fluorescent co-localization of SPP1 and DBA lectin binding in cross-sections of the mouse uterus during the progression of decidualization. Representative photomicrographs of the deciduoma (A, B, E, F, I and J) and decidua (C, D, G, H, K and L) on Days 2 (upper row), 3 (middle row) and 4 (lower row) after the onset of decidualization. Green, red and blue fluorescence localizes DBA lectin-positive uNK cells, SPP1 localization and nuclei, respectively. Scale bars = 0.5 mm. For all photomicrographs, sections are oriented with the antimesometrial (AM) side up and mesometrial (M) side down.

Figure 4.

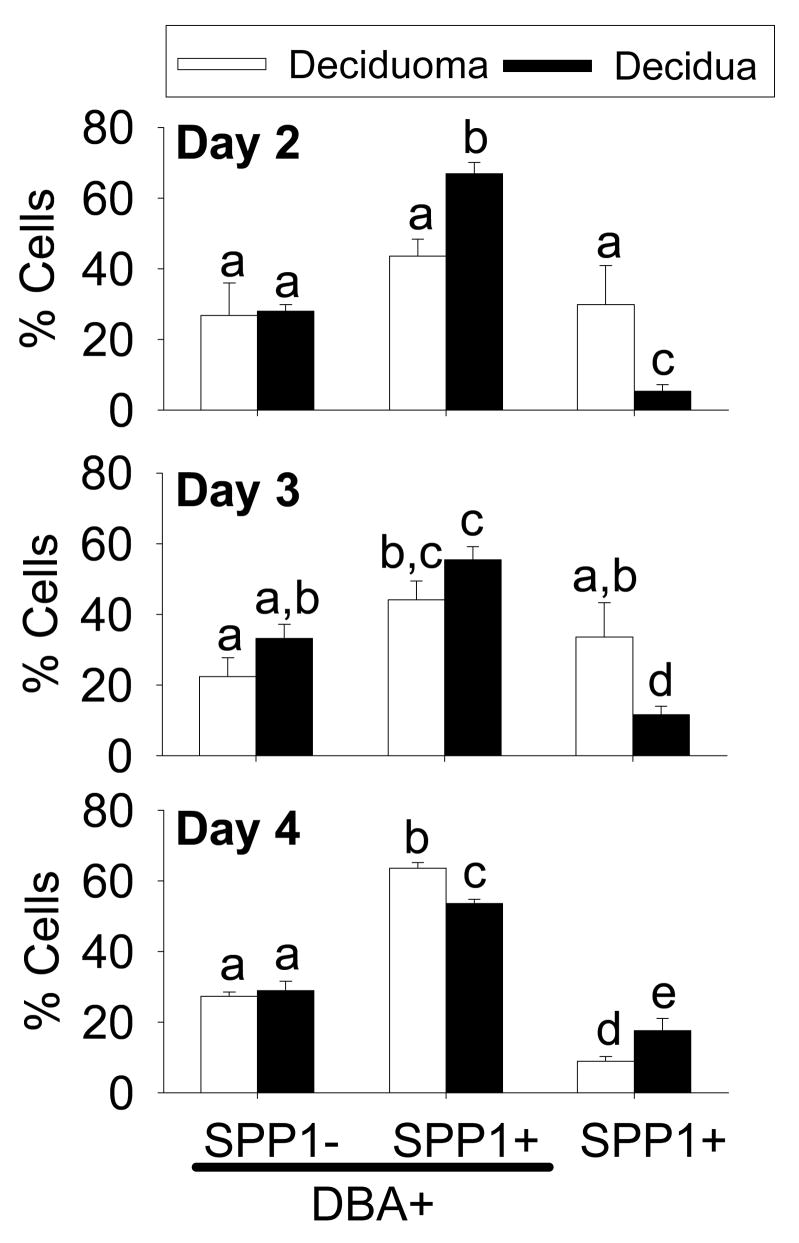

Cell types in the mesometrial region of the mouse decidua and deciduoma that contain SPP1 during the progression of decidualization. DBA lectin-positive uNK cell types (I–IV) that do not (A) and do contain (B) SPP1 were seen. Some SPP1 was localized to DBA lectin-negative cells (C) but these cells were not EMR1 positive (D). Green, red and blue fluorescence shows DBA lectin-positive uNK cells or EMR1, SPP1 and nuclei, respectively. Graph representing the mean percentage of uNK cell types (I–IV) that do not (SPP1−) or do (SPP1+) stain positive for SPP1 in the total mesometrial region of the deciduomas and deciduas on Days 2 (upper graph), 3 (middle graph) and 4 (lower graph) after the onset of decidualization (E). Bars represent the mean (±SEM; N= 4–7) and ND denotes none detected.

For days 2–4 after the onset of decidualization, all DBA lectin-positive uNK cells in the mesometrial region of the deciduomas and deciduas were counted, typed (type I–IV) and grouped by whether they were SPP1-negative or positive (Fig 4E). Further, of the uNK cell types that were SPP1-positive in the deciduoma and decidua, the majority were type 2 on Day 2 and type 3 on both Days 3 plus 4. Overall, on each day examined, there were no differences in the percentage of each uNK cell type between deciduomas and deciduas regardless if they were SPP1-negative or -positive.

To statistically evaluate the different cell types, we counted all SPP1-negative plus -positive uNK cells regardless of type as well as SPP1-postitive non-uNK (DBA lectin-negative) cells throughout the mesometrial region in cross-sections from the deciduomas and deciduas (Fig 5). On Day 2, there was no difference in the percentage of uNK cells in the deciduoma that were SPP1-positive compared to -negative. However, higher percentages of uNK cells were SPP1-positive on Days 3 plus 4 in the deciduomas. In the decidua, unlike the deciduoma, there were higher percentages of SPP1-positive uNK cells compared to SPP1-negative uNK cells at all days examined. Next, for the deciduoma on Days 2 and 3 there were no differences in the percentages of SPP1-positive uNK cells relative to SPP1-positive non-uNK cells. However, by Day 4 there was a significantly (P < 0.05) greater percentage of the SPP1-positive cells that were uNK cells. Unlike the deciduoma, significantly (P < 0.05) greater percentages of SPP1-positive uNK cells compared to SPP1-positive non-uNK cells were found in the decidua on all days examined. Finally, we compared differences in the percentages of SPP1-positive non-uNK cells between the deciduoma and decidua on each day after the onset of decidualization. There were significantly (P < 0.05) higher percentages of these cells in the deciduoma compared to decidua on Days 2 (~6-fold) and 3 (~3-fold). However, the complete opposite was seen on Day 4 where there was a significantly (P < 0.05) lower (~0.5-fold) percentage in the deciduoma compared to decidua.

Figure 5.

Graphs showing the percentage of cells in the deciduoma and decidua staining positive for DBA lectin binding (DBA+) and/or SPP1 (SPP1+/SPP1−) in the mesometrial region of the mouse uterus during the progression of decidualization on Days 2 (upper graph), 3 (middle graph) and 4 (lower graph) after the onset of decidualization. Bars represent the mean (±SEM; N= 4–7) and those with different letters are significantly different (P <0.05).

SPP1 Expression in Il15−/− Mice

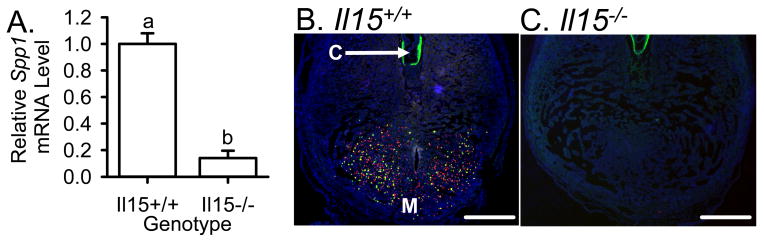

Il15−/− mice lack uNK cells in the uterus during implantation (Barber & Pollard, 2003, Kennedy et al., 2000, Ye et al., 1996). We performed RT-real-time-PCR on decidual total RNA from Il15−/− and Il15+/+ mice to measure the steady-state level of Spp1 mRNA in these tissues. There was a significant (P < 0.01) decrease in the steady-state levels of Spp1 mRNA in the IS of Il15−/− mice compared those from Il15+/+ mice by approximately 7-fold on Day 3 after the onset of decidualization (Fig 6A). To provide further confirmation that the major site of SPP1 localization was to uNK cells, we also carried out double-fluorescent staining of uNK cells and SPP1 protein in uterine cross-sections from Il15−/− and Il15+/+ mice. Surprisingly, a complete loss of SPP1 localization in the sections from Il15−/− mice (Fig 6B) was seen, while localization in Il15+/+ mice was normal (Fig 6C).

Figure 6.

SPP1 expression in the decidua on Day 3 after the onset of decidualization in Il15+/+ compared to Il15−/− mice. Bar graph summarizing the RT-real time-PCR analysis showing relative steady-state levels of Spp1 mRNA in the decidua of Il15+/+ compared to Il15−/− mice on Day 3 after the onset of decidualization (A). Representative photomicrographs of DBA lectin- and SPP1-stained cross-sections of the mouse decidua from Il15+/+ (B) and Il15−/− mice (C). Green and red fluorescent colors indicate DBA lectin binding and SPP1 localization, respectively. Bars represent the mean (±SEM; N= 4) and those with different letters are significantly different (P <0.01). For both photomicrographs, sections are oriented with the mesometrial (M) side down and also shown is the conceptus (C).

DISCUSSION

Spp1 expression increases in the pregnant mouse uterus during the progression of decidualization mainly due to an influx of uNK cells. In tissues outside the uterus, Spp1 gene expression is localized to activated lymphocytes including T-cells and a subset of NK cells (Pollack et al., 1994). Further, in vitro experiments show that Spp1 expression increases in NK cells after activation with IL2 (Patarca et al., 1989). Past studies have shown the presence of Spp1 mRNA and an increase in its levels in the mesometrial region of the mouse uterus during the progression of decidualization after the onset of implantation (Nomura et al., 1988, Waterhouse et al., 1992). Although they also provided some evidence that suggested Spp1 mRNA might be present in uNK cells, to the best of our knowledge, there is no definitive proof of this. In this current study, we confirmed that there is an increase in steady-state levels of Spp1 mRNA during the progression of decidualization in the decidua. This increase occurs at a similar time that uNK cells have been previously shown to dramatically increase in the mesometrial region of the mouse decidua (Herington & Bany, 2006, Peel, 1989, Stewart & Peel, 1978). The present study also shows that a major localization of SPP1 protein is within a subpopulation of the granulated uNK cell types in the uterus during the progression of decidualization. Taken together, these observations provide evidence that uNK cells are a major source of Spp1 expression in the uterus during the progression of decidualization in the decidua. This is strongly supported by the additional observation of this study that there is a dramatic decrease in Spp1 gene expression in the decidua of uNK cell-deficient (Ashkar et al., 2003, Ye et al., 1996) Il15−/− compared to that of normal Il15+/+ mice.

The localization of Spp1 expression in the uterus dramatically changes during early pregnancy in mice. Recently it has been shown that all Spp1 is expressed in the luminal epithelia and EMR1-positive immune cells in the mouse endometrium around the onset of implantation (White et al., 2006). As discussed above, Spp1 expression is localized mainly to DBA lectin-positive granulated uNK cell types in the endometrium after the onset of implantation as it undergoes the process of decidualization. The dominant uNK cell types where this protein is localized changes from type 2 to type 3 in both the deciduoma and decidua during the progression of decidualization. Notably, this correlates well with previous work (Herington & Bany, 2006) showing these are the dominant types of uNK cells present in the uterus at these times. Therefore, the changes seen in SPP1 localization appear to depend on changes in the proportion of uNK cell types during decidualization. Further, since the majority SPP1 expressing cells in the stroma of the endometrium around the onset of implantation have been shown to be EMR1-positive cells, we hypothesized that the non-uNK (DBA lectin-negative) SPP1-positive cells found in this study were also EMR1-positive during the progression of decidualization. However, we found that SPP1 protein was not co-localized to the EMR1-positive immune cells in the decidua and deciduoma at this time. To complicate matters, all SPP1-positive cells appeared to be absent in the decidua of Il15−/− mice during the progression of decidualization, including the SPP1-positive non-uNK cells. This suggests uNK cells may regulate the presence of the SPP1-positive non-uNK cells. It has been shown that SPP1 is a chemotactic factor for many immune cell types in other tissue (Denhardt & Guo, 1993, Patarca et al., 1993). Thus, we still speculate the SPP1-positive non-uNK cells observed in the present study are immune cells. However, more work is required to identify the exact identity of these cells in the future.

The level of Spp1 expression in mouse uterus during the progression of decidualization is enhanced in the presence of a conceptus, at least in part, due to its influence on uNK cells. This study shows that SPP1 protein is localized to a majority of the granulated uNK cell types in the mouse deciduoma and decidua during the progression of decidualization. In a similar fashion to the decidua, previous work (Nomura et al., 1988) in combination along with the work in this study indicates that Spp1 expression increases in the deciduoma. However, to our knowledge, there have been no reports where the level and localization of Spp1 gene expression has never been compared between the deciduoma (conceptus absent) and decidua (conceptus present) during the progression of decidualization. Indeed, one interesting aspect of the expression of Spp1 in the deciduomas found in this study is that its levels were significantly lower compared to the deciduas at similar times after the onset of decidualization. This decreased level of Spp1 expression in the deciduoma compared to decidua correlates well to a previous finding that there are less uNK cells in the deciduoma compared to decidua during the progression of decidualization (Herington & Bany, 2006). That study shows uNK cells appear in the endometrium during the progression of decidualization regardless of whether it’s a deciduoma or decidua. However, if a conceptus is present there are significantly more uNK cells. Therefore, the lower level of Spp1 expression during the progression of decidualization in the deciduoma appears to be a consequence of the reduction in uNK cell numbers compared to that of the decidua.

Although many different functions have been attributed to SPP1 protein in other tissues, we know very little about its function in the mouse uterus during decidualization. A survey of the current literature reveals several potential functions of SPP1 protein in other tissues and include such things as cell-cell adhesion (Leali et al., 2003), angiogenesis (Denhardt & Guo, 1993, Prols et al., 1998, Shijubo et al., 1999, Takano et al., 2000) and immune cell chemoattraction (Liaw et al., 1995) and immune cell function (Denhardt et al., 2001, O’Regan et al., 2000). Further, this is complicated by the fact that SPP1 function may (Ek-Rylander et al., 1994, Nemir et al., 1989) or may not (Weber et al., 1996) change depending on its phosphorylation status. Notably, SPP1 protein which is secreted by uterine epithelium has been suggested to provide a substrate for integrin-mediated interactions at the conceptus-maternal interface at the onset of implantation in several species (Apparao et al., 2001, Johnson et al., 1999, von Wolff et al., 2001), including mice (White et al., 2006). Although these are potential roles of SPP1 in the mouse uterus during the progression of decidualization, a great deal of work will be required to confirm this. One logical approach may be to conduct an in-depth investigation of Spp1-deficient mice (Liaw et al., 1998) to determine if there are abnormalities in the utero-placental vascular changes during implantation since it was found that these mice experience decreased pregnancy rates and an intrauterine growth restriction during pregnancy as compared with their wild-type counterparts (Weintraub et al., 2004). Since uNK cells do play a role in changes in the maternal vasculature during implantation in the mouse (Croy et al., 2003) and appear to be a major source of SPP1, such a role is plausible.

Acknowledgments

This study was supported by NIH Grant HD049010.

Footnotes

Supported by NIH grant HD049010

References

- Apparao KB, Murray MJ, Fritz MA, Meyer WR, Chambers AF, Truong PR, Lessey BA. Osteopontin and its receptor alphavbeta(3) integrin are coexpressed in the human endometrium during the menstrual cycle but regulated differentially. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2001;86:4991–5000. doi: 10.1210/jcem.86.10.7906. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ashkar AA, Black GP, Wei Q, He H, Liang L, Head JR, Croy BA. Assessment of requirements for IL-15 and IFN regulatory factors in uterine NK cell differentiation and function during pregnancy. J Immunol. 2003;171:2937–2944. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.171.6.2937. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Austyn JM, Gordon S. F4/80, a monoclonal antibody directed specifically against the mouse macrophage. Eur J Immunol. 1981;11:805–815. doi: 10.1002/eji.1830111013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bany BM, Cross JC. Post-implantation mouse conceptuses produce paracrine signals that regulate the uterine endometrium undergoing decidualization. Dev Biol. 2006;294:445–456. doi: 10.1016/j.ydbio.2006.03.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barber EM, Pollard JW. The uterine NK cell population requires IL-15 but these cells are not required for pregnancy nor the resolution of a Listeria monocytogenes infection. J Immunol. 2003;171:37–46. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.171.1.37. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Croy BA, He H, Esadeg S, Wei Q, McCartney D, Zhang J, Borzychowski A, Ashkar AA, Black GP, Evans SS, et al. Uterine natural killer cells: insights into their cellular and molecular biology from mouse modelling. Reproduction. 2003;126:149–160. doi: 10.1530/rep.0.1260149. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Das RM, Martin L. Uterine DNA synthesis and cell proliferation during early decidualization induced by oil in mice. J Reprod Fertil. 1978;53:125–128. doi: 10.1530/jrf.0.0530125. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- De M, Choudhuri R, Wood GW. Determination of the number and distribution of macrophages, lymphocytes, and granulocytes in the mouse uterus from mating through implantation. J Leukoc Biol. 1991;50:252–262. doi: 10.1002/jlb.50.3.252. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Denhardt DT, Guo X. Osteopontin: a protein with diverse functions. Faseb J. 1993;7:1475–1482. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Denhardt DT, Noda M, O’Regan AW, Pavlin D, Berman JS. Osteopontin as a means to cope with environmental insults: regulation of inflammation, tissue remodeling, and cell survival. J Clin Invest. 2001;107:1055–1061. doi: 10.1172/JCI12980. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ek-Rylander B, Flores M, Wendel M, Heinegard D, Andersson G. Dephosphorylation of osteopontin and bone sialoprotein by osteoclastic tartrate-resistant acid phosphatase. Modulation of osteoclast adhesion in vitro. J Biol Chem. 1994;269:14853–14856. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Finn CA, Martin L. Endocrine control of the timing of endometrial sensitivity to a decidual stimulus. Biol Reprod. 1972;7:82–86. doi: 10.1093/biolreprod/7.1.82. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Finn CA, Martin L. The control of implantation. J Reprod Fertil. 1974;39:195–206. doi: 10.1530/jrf.0.0390195. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Herington JL, Bany BM. Effect of the Conceptus on Uterine Natural Killer Cell Numbers and Function in the Mouse Uterus During Decidualization. Biol Reprod. 2006 doi: 10.1095/biolreprod.106.056630. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hunt JS. Immunologically relevant cells in the uterus. Biol Reprod. 1994;50:461–466. doi: 10.1095/biolreprod50.3.461. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johnson GA, Spencer TE, Burghardt RC, Bazer FW. Ovine osteopontin: I. Cloning and expression of messenger ribonucleic acid in the uterus during the periimplantation period. Biol Reprod. 1999;61:884–891. doi: 10.1095/biolreprod61.4.884. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kennedy MK, Glaccum M, Brown SN, Butz EA, Viney JL, Embers M, Matsuki N, Charrier K, Sedger L, Willis CR, et al. Reversible defects in natural killer and memory CD8 T cell lineages in interleukin 15-deficient mice. J Exp Med. 2000;191:771–780. doi: 10.1084/jem.191.5.771. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krehbiel RH. Cytological studies of the decidual reaction in the rat during early pregnancy and in the production of the deciduomata. Physiological Zoology. 1937;X:212–233. [Google Scholar]

- Leali D, Dell’Era P, Stabile H, Sennino B, Chambers AF, Naldini A, Sozzani S, Nico B, Ribatti D, Presta M. Osteopontin (Eta-1) and fibroblast growth factor-2 cross-talk in angiogenesis. J Immunol. 2003;171:1085–1093. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.171.2.1085. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lejeune B, Van Hoeck J, Leroy F. Satellite versus total DNA replication in relation to endopolyploidy of decidual cells in the mouse. Chromosoma. 1982;84:511–516. doi: 10.1007/BF00292852. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liaw L, Lindner V, Schwartz SM, Chambers AF, Giachelli CM. Osteopontin and beta 3 integrin are coordinately expressed in regenerating endothelium in vivo and stimulate Arg-Gly-Asp-dependent endothelial migration in vitro. Circ Res. 1995;77:665–672. doi: 10.1161/01.res.77.4.665. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liaw L, Birk DE, Ballas CB, Whitsitt JS, Davidson JM, Hogan BL. Altered wound healing in mice lacking a functional osteopontin gene (spp1) J Clin Invest. 1998;101:1468–1478. doi: 10.1172/JCI1122. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Loeb L. The production of deciduomata and the relation between the ovaries and the formation of the decidua. J Am Med Assoc. 1908;50:1897–1901. [Google Scholar]

- McGarry MP, Stewart CC. Murine eosinophil granulocytes bind the murine macrophage-monocyte specific monoclonal antibody F4/80. J Leukoc Biol. 1991;50:471–478. doi: 10.1002/jlb.50.5.471. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nagy A, Gertsenstein M, Vintersten K, Behringer R. Manipulating the Mouse Embryo: A Laboratory Manual. 3. Cold Spring Harbor: Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press; 2003. Manipulation of postimplantation embryos; pp. 209–250. [Google Scholar]

- Nemir M, DeVouge MW, Mukherjee BB. Normal rat kidney cells secrete both phosphorylated and nonphosphorylated forms of osteopontin showing different physiological properties. J Biol Chem. 1989;264:18202–18208. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nomura S, Wills AJ, Edwards DR, Heath JK, Hogan BL. Developmental expression of 2ar (osteopontin) and SPARC (osteonectin) RNA as revealed by in situ hybridization. J Cell Biol. 1988;106:441–450. doi: 10.1083/jcb.106.2.441. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- O’Regan AW, Nau GJ, Chupp GL, Berman JS. Osteopontin (Eta-1) in cell-mediated immunity: teaching an old dog new tricks. Immunol Today. 2000;21:475–478. doi: 10.1016/s0167-5699(00)01715-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Okamoto H. Osteopontin and cardiovascular system. Mol Cell Biochem. 2006 doi: 10.1007/s11010-006-9368-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Paffaro VA, Jr, Bizinotto MC, Joazeiro PP, Yamada AT. Subset classification of mouse uterine natural killer cells by DBA lectin reactivity. Placenta. 2003;24:479–488. doi: 10.1053/plac.2002.0919. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Patarca R, Saavedra RA, Cantor H. Molecular and cellular basis of genetic resistance to bacterial infection: the role of the early T-lymphocyte activation-1/osteopontin gene. Crit Rev Immunol. 1993;13:225–246. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Patarca R, Freeman GJ, Singh RP, Wei FY, Durfee T, Blattner F, Regnier DC, Kozak CA, Mock BA, Morse HC, 3rd, et al. Structural and functional studies of the early T lymphocyte activation 1 (Eta-1) gene. Definition of a novel T cell-dependent response associated with genetic resistance to bacterial infection. J Exp Med. 1989;170:145–161. doi: 10.1084/jem.170.1.145. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peel S. Granulated metrial gland cells. Adv Anat Embryol Cell Biol. 1989;115:1–112. doi: 10.1007/978-3-642-74170-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peters JH, Gieseler R, Thiele B, Steinbach F. Dendritic cells: from ontogenetic orphans to myelomonocytic descendants. Immunol Today. 1996;17:273–278. doi: 10.1016/0167-5699(96)80544-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pollack SB, Linnemeyer PA, Gill S. Induction of osteopontin mRNA expression during activation of murine NK cells. J Leukoc Biol. 1994;55:398–400. doi: 10.1002/jlb.55.3.398. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pollard JW, Lin EY, Zhu L. Complexity in uterine macrophage responses to cytokines in mice. Biol Reprod. 1998;58:1469–1475. doi: 10.1095/biolreprod58.6.1469. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pollard JW, Hunt JS, Wiktor-Jedrzejczak W, Stanley ER. A pregnancy defect in the osteopetrotic (op/op) mouse demonstrates the requirement for CSF-1 in female fertility. Dev Biol. 1991;148:273–283. doi: 10.1016/0012-1606(91)90336-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Prols F, Loser B, Marx M. Differential expression of osteopontin, PC4, and CEC5, a novel mRNA species, during in vitro angiogenesis. Exp Cell Res. 1998;239:1–10. doi: 10.1006/excr.1997.3882. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Robertson SA, Roberts CT, Farr KL, Dunn AR, Seamark RF. Fertility impairment in granulocyte-macrophage colony-stimulating factor-deficient mice. Biol Reprod. 1999;60:251–261. doi: 10.1095/biolreprod60.2.251. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sakoff JA, Murdoch RN. Alterations in uterine calcium ions during induction of the decidual cell reaction in pseudopregnant mice. J Reprod Fertil. 1994;101:97–102. doi: 10.1530/jrf.0.1010097. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schnell SA, Staines WA, Wessendorf MW. Reduction of lipofuscin-like autofluorescence in fluorescently labeled tissue. J Histochem Cytochem. 1999;47:719–730. doi: 10.1177/002215549904700601. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shijubo N, Uede T, Kon S, Maeda M, Segawa T, Imada A, Hirasawa M, Abe S. Vascular endothelial growth factor and osteopontin in stage I lung adenocarcinoma. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 1999;160:1269–1273. doi: 10.1164/ajrccm.160.4.9807094. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stewart I, Peel S. The differentiation of the decidua and the distribution of metrial gland cells in the pregnant mouse uterus. Cell Tissue Res. 1978;187:167–179. doi: 10.1007/BF00220629. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Takano S, Tsuboi K, Tomono Y, Mitsui Y, Nose T. Tissue factor, osteopontin, alphavbeta3 integrin expression in microvasculature of gliomas associated with vascular endothelial growth factor expression. Br J Cancer. 2000;82:1967–1973. doi: 10.1054/bjoc.2000.1150. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tibbetts TA, Conneely OM, O’Malley BW. Progesterone via its receptor antagonizes the pro-inflammatory activity of estrogen in the mouse uterus. Biol Reprod. 1999;60:1158–1165. doi: 10.1095/biolreprod60.5.1158. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- von Wolff M, Strowitzki T, Becker V, Zepf C, Tabibzadeh S, Thaler CJ. Endometrial osteopontin, a ligand of beta3-integrin, is maximally expressed around the time of the “implantation window”. Fertil Steril. 2001;76:775–781. doi: 10.1016/s0015-0282(01)02015-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang X, Seed B. A PCR primer bank for quantitative gene expression analysis. Nucleic Acids Res. 2003;31:e154. doi: 10.1093/nar/gng154. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Waterhouse P, Parhar RS, Guo X, Lala PK, Denhardt DT. Regulated temporal and spatial expression of the calcium-binding proteins calcyclin and OPN (osteopontin) in mouse tissues during pregnancy. Mol Reprod Dev. 1992;32:315–323. doi: 10.1002/mrd.1080320403. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weber GF, Ashkar S, Glimcher MJ, Cantor H. Receptor-ligand interaction between CD44 and osteopontin (Eta-1) Science. 1996;271:509–512. doi: 10.1126/science.271.5248.509. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weintraub AS, Lin X, Itskovich VV, Aguinaldo JG, Chaplin WF, Denhardt DT, Fayad ZA. Prenatal detection of embryo resorption in osteopontin-deficient mice using serial noninvasive magnetic resonance microscopy. Pediatr Res. 2004;55:419–424. doi: 10.1203/01.PDR.0000112034.98387.B2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- White FJ, Burghardt RC, Hu J, Joyce MM, Spencer TE, Johnson GA. Secreted phosphoprotein 1 (osteopontin) is expressed by stromal macrophages in cyclic and pregnant endometrium of mice, but is induced by estrogen in luminal epithelium during conceptus attachment for implantation. Reproduction. 2006;132:919–929. doi: 10.1530/REP-06-0068. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ye W, Zheng LM, Young JD, Liu CC. The involvement of interleukin (IL)-15 in regulating the differentiation of granulated metrial gland cells in mouse pregnant uterus. J Exp Med. 1996;184:2405–2410. doi: 10.1084/jem.184.6.2405. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]