Abstract

Background

Long-term HCT survivors have a high prevalence of severe and chronic health conditions, placing significant demands on the healthcare system. The aim of this study was to evaluate and compare the healthcare utilization by adult Hispanic and non-Hispanic white long term survivors of HCT.

Methods

A mailed questionnaire was used to assess self-reported health care utilization in three domains: general contact with healthcare system, general physical examination outside cancer center (GPE), and Cancer/HCT center visit. Eligible individuals had undergone HCT between 1974 and 1998, at 21 years of age or older and survived 2 or more years after HCT.

Results

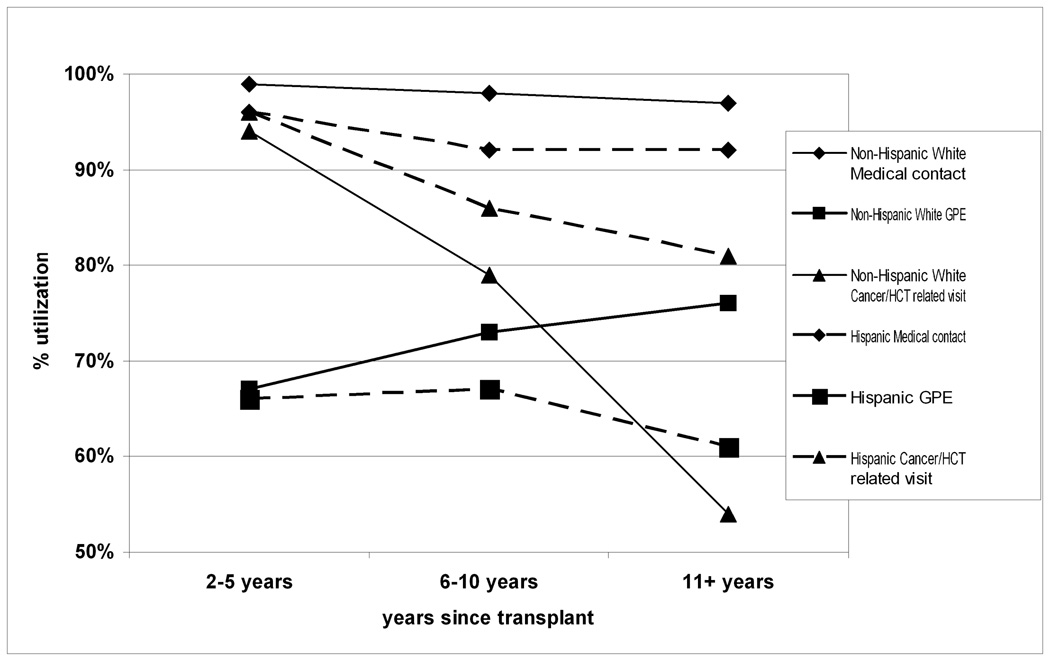

The cohort included 681 non-Hispanic white and 137 Hispanic survivors. The median age at HCT was 38.3 years and the median length of follow-up was 6.6 years. Hispanic survivors had lower family income and education and were more likely to lack health insurance. The prevalence of GPE increased significantly over time among non- Hispanic whites (67% at 2–5 years to 76% at 11+ years) but remained unchanged among Hispanics (66% to 61%). Cancer/ HCT center visits declined over time among both Hispanics and non-Hispanic whites but higher proportion of Hispanics reported Cancer/HCT center visit at 11+ years after HCT (81% vs. 54%).

Conclusion

As compared to non-Hispanic whites, Hispanic survivors are less likely to establish contact with a primary care providers years after the HCT and continue to receive care at Cancer/HCT center. Future studies of this population are needed to establish the factors responsible for this pattern of healthcare utilization.

Keywords: Hematopoietic cell transplantation, Survivor, Hispanics, Healthcare utilization

INTRODUCTION

Ethnicity and race are important determinants of health outcome in various disease states. According to the 2005 census, Hispanics form the largest ethnic minority group in the United States, constituting 14.4% of the entire population.1 Compared to non-Hispanic whites, Hispanics are considered to be a vulnerable population for adverse health outcomes in general2 and in the field of oncology in particular3. Significant differences have been noted in the incidence, and mortality related to cancer in the Hispanic populations as compared to non-Hispanic whites.4, 5 The reasons for such differences include, but are not limited to, financial, cultural and political barriers as well as barriers within the healthcare system. Accessibility and continuity have been identified as key dimensions of primary care by the Institute of Medicine.6 Of all the minority racial and ethnic groups in the United States, Hispanics are most likely to be uninsured.7–11 Furthermore, studies have shown that Hispanics are more likely to report lack of continuity of care or no usual source of care.12–14 However, there is limited information regarding the patterns of healthcare utilization by Hispanic cancer survivors.15

Hematopoietic cell transplantation (HCT) has become an increasingly utilized therapeutic option for a variety of life-threatening malignant and non-malignant conditions. High-dose chemotherapy, total body irradiation (TBI), and management of graft vs. host disease (GvHD) with the attendant prolonged immune suppression, place the survivors of HCT at a particularly high risk of developing late complications necessitating an increased utilization of healthcare services.16–24

We have previously described the healthcare utilization patterns by a predominantly non-Hispanic white population of HCT survivors.25 However, the patterns of healthcare utilization by a comparable Hispanic HCT survivor population was not described in detail. The aim of this study was to compare the patterns of healthcare utilization of adult Hispanic HCT survivors with those of non-Hispanic white HCT survivors, and to evaluate the risk factors associated with the lack of healthcare utilization in this population.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Patients

The self-reported utilization of health care services by individuals enrolled on the Bone Marrow Transplant Survivor Study (BMTSS) was evaluated in this study. The BMTSS is a collaborative retrospective cohort study between City of Hope National Medical Center (COH) and the University of Minnesota (UMN). Survivors who met all the following criteria were eligible for participation in the BMTSS: i) HCT performed at COH or UMN between 1974 and 1998; ii) survival of 2 or more years after HCT irrespective of current disease status; and iii) English- or Spanish-speaking. The current analysis was restricted to subjects: i) 21 years of age or older at time of HCT; ii) belonging to one of the following two ethnic/ racial categories: non-Hispanic whites or Hispanics; and iii) alive at the time of study participation. The BMTSS was approved by the Human Subjects committee at the participating institutions and informed consent was obtained according to the Declaration of Helsinki.

Between February 1999 and August 2004, a 255-item self-administered questionnaire was used to collect information from eligible participants regarding: demographic characteristics, marital status, insurance coverage, education, income, employment, post-HCT complications, utilization of medical care, current health status (response options: excellent, very good, good, fair, poor), and concerns for future health. This questionnaire was adapted from the questionnaire used in the Childhood Cancer Survivor Study with modifications to include items specific to an HCT population. A Spanish version of the questionnaire was used for mono-lingual Spanish-speaking participants. Details regarding primary diagnosis, HCT conditioning, chronic GvHD, and prophylaxis and treatment of GvHD were obtained from the medical records, with the consent of the study participant.

Outcomes Measures

Self-reported healthcare utilization in the two years preceding the study was assessed. The three domains used to evaluate healthcare utilization included: i) general contact with the health care system (general contact); ii) general physical examination outside a Cancer/HCT center (GPE) ; iii) Cancer/HCT-related visit with the transplant team or medical visit at a cancer center (Cancer/HCT center visit). These outcomes were not mutually exclusive. General or nonspecific medical contact was any contact with a physician, nurse, or other health care provider in the two years before the survey. A visit to a physician’s office or a phone contact was also considered a general medical contact. Self-report of a general physical examination outside of a Cancer/HCT center was considered as a GPE. All visits to see a physician at the Cancer/HCT center, irrespective of the reason for the visit, were included as Cancer/HCT center visits. No details regarding the content of the visit with any providers were collected.

Analysis

Outcome measures were analyzed for the entire cohort, and for Hispanic and non-Hispanic white HCT survivors separately. Comparisons between Hispanics and non-Hispanic whites were made by using t-test for continuous variables and chi-square for categorical variables. Odds ratios and 95% confidence intervals for risk factors for absence of healthcare utilization were calculated by using unconditional logistic regression. Variables with a p- value <0.1 on univariate analysis were included in the stepwise logistic regression. The final multivariate regression model only included variables with p-values <0.05. The variables considered in the univariate analysis included gender, ethnicity (Hispanics vs. non-Hispanic whites), age at time of HCT, age at study participation, educational status, household income, current health insurance, primary diagnosis, conditioning regimen (TBI vs. non-TBI based), time since HCT, presence of chronic GvHD and its prophylaxis and treatment, type of transplantation (allogeneic vs. autologous), risk of relapse at HCT (standard vs. high risk), current health status and concerns for future health. Patients were considered at standard risk for relapse if they were in first or second complete remission after acute leukemia, and lymphoma, and first chronic phase of chronic myeloid leukemia. All other patients were placed into the high-risk category. The analysis was conducted for the entire cohort, and also stratified by type of transplant (autologous HCT and allogeneic {related and unrelated donor} HCT). Statistical analyses were performed using SAS software 9.1 (SAS institute, Cary, NC).

RESULTS

Of the 1224 patients eligible for participation in this study, 1143 (93%) were successfully contacted and 818 (72%) agreed to participate. There were no differences between the 818 participants and the 406 non-participants in terms of gender (males: 55% vs. 59%, p=0.16), type of transplant (autologous 49%, allogeneic 41%, matched unrelated donor 10% vs. 47%, 45%, 8%, p=0.35, respectively), primary diagnosis (chronic myeloid leukemia 26.5%, acute myeloid leukemia 22.5%, Hodgkin and non- Hodgkin lymphoma 32.9%, acute lymphocytic leukemia 6.0%, other 12.2% vs. 24.6%, 20.0%, 32.8%, 8.4%, 14.3%, respectively, p=0.37), and risk of relapse at HCT (61.6% vs. 63.6%, p=0.51). However, participants were older at HCT compared to non-participants (39 vs. 36 years, p<0.001). The age difference was predominantly observed in non-Hispanic whites (40 vs. 37 years, p<0.001). For Hispanic survivors, age at HCT was similar for participants and non-participants (35 vs. 36, p=0.72).

Self-reported race/ethnicity resulted in identification of 681 non-Hispanic whites and 137 Hispanics in this cohort (16.7%). Among the 137 Hispanics, 96 reported a reasonable understanding of written and spoken English, while 41 were monolingual Spanish-speaking.

The demographic characteristics of the entire cohort, by race/ethnicity and by language are described in Table 1. Over one half of the cohort was male and the median age at HCT was 38 years. Median length of follow-up was 6.6 years (range, 2 to 24.4 years), and 56% of the cohort had been followed for over 5 years. The Hispanic HCT survivors were significantly younger than non-Hispanic whites at time of HCT (p=0.02) and at study participation (p=0.003). In addition, Hispanic survivors were significantly more likely to be uninsured (22.4% vs. 4.6%, p<0.001); to report a lower educational background (some high school or lower education: 37.5% vs. 6%, p<0.001); and to report household incomes below $20,000 (45.6% vs. 8.8%, p<0.001). The time from HCT to study participation was significantly longer for Hispanics when compared with non-Hispanic whites (mean follow-up time 8.7 vs. 7.6 years, p=0.01). Among the Hispanic survivors, the mono-lingual Spanish-speaking survivors were older at the time of HCT and at study participation, and had lower education as well as household income, when compared to their English-speaking counterparts.

Table 1.

Demographic characteristics of Hispanic and non-Hispanic white survivors of HCT.

| Entire Cohort (N=818) |

Non-Hispanic White (N=681) |

Hispanic-White (n=137) |

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Overall | P* | English-speaking (n=96) |

Spanish-speaking (n=41) |

P$ | |||

| Age at transplantation (y) | |||||||

| Median (range) | 38.3 (21–68.6) | 39.0 (21.0–68.6) | 33.2 (21.1–62.4) | 31.5 (21.2–62.4) | 37.3 (21.4–61.4) | ||

| Mean (SD) | 39.1 (10.7) | 39.9 (10.7) | 35.1 (10.2) | <0.001 | 33.7 (10.0) | 38.2 (10.2) | 0.02 |

| Age at study participation (y) | |||||||

| Median (range) | 46.6 (23.2–73) | 47.4 (23.3–73.0) | 43.3 (25.3–67.4) | 41.6 (25.3–66.8) | 47.4 (29.2–67.4) | ||

| Mean (SD) | 46.8 (9.8) | 47.5 (9.7) | 43.7 (9.9) | <0.001 | 42.1 (9.8) | 47.6 (9.3) | 0.003 |

| Follow up time (y) | |||||||

| Median (range) | 6.6 (2– 24.4) | 6.4 (2.0–24.4) | 7.9 (2.5–20.9) | 7.3 (2.5–20.9) | 8.9 (4.8–19.2) | ||

| Mean (SD) | 7.8 (4.5) | 7.6 (4.4) | 8.7 (4.6) | 0.01 | 8.3 (4.9) | 9.4 (3.6) | 0.16 |

| Gender n (%) | 0.11 | 0.66 | |||||

| Male | 451 (55.1) | 367 (53.9) | 84 (61.3) | 60 (62.5) | 24 (58.4) | ||

| Education, n (%) | <0.001 | <0.001 | |||||

| < High school | 92 (11.3) | 41 (6.0) | 51 (37.5) | 14 (14.6) | 37 (92.5) | ||

| High school graduate and some college | 374 (45.9) | 326 (48.0) | 48 (35.3) | 45 (46.9) | 3 (7.5) | ||

| College degree | 349 (42.8) | 312 (45.9) | 37 (27.2) | 37 (38.5) | 0 (0) | ||

| Household income, n (%) | <0.001 | 0.008 | |||||

| >= $60,000/y | 358 (46.4) | 342 (52.9) | 16 (12.8) | 16 (17.4) | 0 (0) | ||

| $20,000–59,999/y | 300 (38.9) | 248 (38.3) | 52 (41.6) | 39 (42.4) | 13 (39.4) | ||

| <$20,000/y | 114 (14.8) | 57 (8.8) | 57 (45.6) | 37 (40.2) | 20 (60.6) | ||

| Current health insurance, n (%) | <0.001 | 0.17 | |||||

| Uninsured | 61 (7.5) | 31 (4.6) | 30 (22.4) | 18 (19.1) | 12 (30.0) | ||

| Duration of follow-up (y), n (%) | 0.12 | 0.04 | |||||

| 2–5 | 359 (43.9) | 309 (45.4) | 50 (36.5) | 41 (42.7) | 9 (21.9) | ||

| 6–10 | 284 (34.7) | 233 (34.2) | 51 (37.2) | 30 (31.2) | 21 (51.2) | ||

| ≥ 11 | 175 (21.4) | 139 (20.4) | 36 (26.3) | 25 (26.0) | 11 (26.8) | ||

P* value for non-Hispanic vs. Hispanic survivors.

P$ value for English-speaking vs. Spanish-speaking Hispanic survivors

Table 2 describes the clinical characteristics for the entire cohort, by the two race/ethnicities of survivors (Hispanics vs. non-Hispanic whites) and by the preferred spoken language. A significantly larger proportion of Hispanic survivors had undergone allogeneic HCT (62% vs. 36%, p<0.001) and received cyclosporine A (57% vs. 35%, p<0.001) as either prophylaxis or treatment for GvHD. Among the Hispanic survivors, English and Spanish-speaking Hispanic survivors were comparable in terms of primary diagnosis, risk of relapse at HCT, and use of TBI-based conditioning regimen. However, the monolingual Spanish-speaking Hispanic survivors were more likely to have been exposed to cyclosporine A for GvHD prophylaxis/ treatment. A larger proportion of Hispanic survivors expressed lack of concern for future health compared to non-Hispanic white survivors (11% vs. 4.5%, p=0.002).

Table 2.

Clinical characteristics of Hispanic and non-Hispanic White HCT survivors.

| Entire Cohort (N=818) |

Non-Hispanic White (N=681) |

Hispanic-White (N=137) |

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| n (%) | n (%) | Overall n (%) |

P* | English-speaking (n=96) |

Spanish-speaking (n=41) |

P$ | |

| Primary Diagnosis | <0.001 | 0.59 | |||||

| HL/NHL | 269 (32.9) | 243 (35.7) | 26 (19.0) | 21 (21.9) | 5 (12.2) | ||

| ALL | 49 (6.0) | 31 (4.55) | 18 (13.1) | 13 (13.5) | 5 (12.2) | ||

| AML | 183 (22.4) | 148 (21.7) | 35 (25.6) | 25 (26.0) | 10 (24.4) | ||

| CML | 217 (26.5) | 179 (26.3) | 38 (27.7) | 25 (26.0) | 13 (31.7) | ||

| Other | 100 (12.2) | 80 (11.7) | 20 (14.6) | 12 (12.5) | 8 (19.5) | ||

| Relapse risk at HCT | 0.28 | 0.71 | |||||

| High risk | 313 (38.4) | 266 (39.2) | 47 (34.3) | 32 (33.3) | 15 (36.6) | ||

| Conditioning regimen | |||||||

| TBI | 639 (78.4) | 533 (78.5) | 106 (77.9) | 0.89 | 74 (77.9) | 32 (78.0) | 0.98 |

| Chronic GvHD | 0.10 | 0.15 | |||||

| Yes | 255 (31.2) | 204 (30.0) | 51 (37.2) | 32 (33.3) | 19 (46.3) | ||

| GvHD prophylaxis/ treatment | |||||||

| Cyclosporine A | 316 (36.7) | 239 (35.1) | 77 (56.6) | <0.001 | 48 (50.0) | 29 (72.5) | 0.02 |

| Current health | 0.06 | 0.42 | |||||

| Fair/poor | 172 (21.1) | 135 (19.9) | 37 (27.0) | 24 (25.0) | 13 (31.7) | ||

| Concerns for future health | 0.002 | ||||||

| Not concerned | 45 (5.6) | 30 (4.5) | 15 (11.2) | 8 (8.5) | 7 (17.5) | 0.13 | |

| HCT type | <0.001 | 0.13 | |||||

| Allogeneic | 335 (41) | 250 (36.7) | 85 (62.0) | 55 (57.3) | 30 (73.2) | ||

| MUD | 80 (9.8) | 75 (11.0) | 5 (3.7) | 5 (5.2) | 0 | ||

| Autologous | 403 (49.3) | 356 (52.3) | 47 (34.3) | 36 (37.5) | 11 (26.8) | ||

P* value for non-Hispanic vs. Hispanic survivors.

P$ value for English-speaking vs. Spanish-speaking Hispanic survivors

Patterns of Healthcare Utilization

The overall healthcare utilization by ethnicity and spoken language, and stratified by type of transplantation is shown in Table 3. Hispanic survivors were significantly less likely to report general contact with the healthcare system (93% vs. 98%, p=0.001) in the two years preceding the study, when compared with the non-Hispanic whites. Both groups reported comparable prevalence of GPE (66% vs. 71%, p=0.23). However, Hispanic survivors were significantly more likely to report a visit to the Cancer/HCT center than non-Hispanic whites (88% vs. 81%, p=0.03). Among Hispanic survivors, the monolingual Spanish-speaking Hispanics were significantly less likely to report GPE (49% vs. 73%, p=0.006) compared to English-speaking Hispanics.

Table 3.

Healthcare utilization by Hispanic and non-Hispanic white survivors of HCT

| Entire Cohort (N=818) |

Non-Hispanic White (N=681) |

Hispanic-White (N=137) |

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| n (%) | n (%) | Overall n (%) |

P* | English-speaking (n=96) |

Spanish-speaking (n=41) |

P$ | |

| Any HCT | |||||||

| General contact | 797 (97.4) | 669 (98.2) | 128 (93.4) | 0.001 | 89 (92.7) | 39 (95.1) | 0.72 |

| GPE | 573 (70.0) | 483 (70.9) | 90 (65.7) | 0.23 | 70 (72.9) | 20 (48.8) | 0.006 |

| Cancer/HCT | (670 81.9) | 549 (80.6) | 121 (88.3%) | 0.03 | 84 (87.5) | 37 (90.2) | 0.78 |

| Autologous-HCT Only | |||||||

| General contact | 392 (97.3) | 347 (97.5) | 45 (95.4) | 0.49 | 34 (94.4) | 11 (100.0) | 1.00 |

| GPE | 295 (73.2) | 263 (73.9) | 32 (68.1) | 0.40 | 26 (72.2) | 6 (54.6) | 0.27 |

| Cancer/HCT | 333 (82.6) | 291 (81.7) | 42 (89.4) | 0.20 | 31 (86.1) | 11 (100) | 0.32 |

| Allogeneic/MUD HCT Only | |||||||

| General contact | 405 (97.6) | 322 (99.1) | 83 (92.2) | 0.001 | 55 (91.7) | 28 (93.3) | 1.00 |

| GPE | 278 (67.0) | 220 (67.7) | 58 (64.4) | 0.56 | 44 (73.3) | 14 (46.7) | 0.01 |

| Cancer/HCT | 337 (81.2) | 258 (79.4) | 79 (87.8) | 0.07 | 53 (88.3) | 26 (86.7) | 0.82 |

P* value for non-Hispanic vs. Hispanic survivors.

P$ value for English-speaking vs. Spanish-speaking Hispanic survivors

MUD- Matched unrelated donor

When stratified by type of transplant, a similar pattern was observed in both groups. For the entire cohort, Hispanic survivors were more likely to report cancer/HCT center visits as compared to non-Hispanic whites. The differences by ethnicity were not statistically significant among survivors of autologous HCT. For allogeneic HCT survivors, Hispanics were less likely to report general contact (p=0.001) and more likely to report Cancer Center/HCT-related visits (p=0.07) when compared to non-Hispanic whites. Furthermore, the monolingual Spanish-speaking Hispanics were less likely to report GPE compared to English-speaking Hispanics in both transplant groups, but the difference was significant in survivors of allogeneic HCT only (47% vs. 73%, p=0.01).

Healthcare utilization, as measured by self-reported general medical contact, GPE and visits to Cancer/HCT center, as a function of time after HCT is shown in Figure 1.

Figure 1. Health Care Utilization.

Healthcare utilization as function of time from transplantation in adult Hispanic and non-Hispanic white survivors of HCT.

Healthcare Utilization reported by non-Hispanic whites

The prevalence of general medical contact remained high and did not change significantly over time (99% at 2–5 years, 98% at 6–10 years, 97% at 11+ years after HCT, p for trend= 0.26). There was a significant increase in the prevalence of GPE from 67% at 2–5 years, to 73% at 6–10 years and 76% at 11+years after HCT (p for trend=0.05). On the other hand, Cancer/HCT center visits declined significantly from 94% at 2–5 years to 79% at 6–10 years and 54% at 11+ years after HCT (p for trend <0.001).

Healthcare Utilization reported by Hispanics

Over 90% of Hispanic survivors continued to report general medical contact up to 11+ years from transplantation and this did not change significantly over time (96% at 2– 5 years, 92% at 6–10 years, 92% at 11+ years after HCT, p for trend=0.40). The prevalence of GPE also did not change significantly over time (66% at 2–5 years, 69% at 6–10 years, vs. 61% at 11+ years after HCT, p for trend=0.68). However, the Cancer/HCT center visits declined over time from 96% at 2–5 years to 86% at 6–10 years and 81% at 11+ years after HCT (p for trend=0.03).

Comparison of Healthcare Utilization between non-Hispanic whites and Hispanics

The prevalence of general medical contact remained high over time and did not differ between Hispanic and non-Hispanic survivors (p for follow-up time and race interaction =0.95). Although there was a significant increase in the prevalence of self-reported GPE over time in non-Hispanic whites, and no significant change was observed in Hispanic survivors, the difference was not statistically significant (p for interaction = 0.23). In both groups, Cancer/HCT center visits declined over time. However this decline in Cancer/HCT center visits did not differ significantly between the two groups over time (p for interaction=0.23).

Risk factors for Lack of Healthcare Utilization

Entire Cohort

The results of multivariate analysis for risk factors associated with lack of healthcare utilization for the entire cohort are shown in Table 4.

Table 4.

Risk factors for absence of healthcare utilization in entire cohort of Hispanic & non-Hispanic survivors of HCT

| Risk Factors* | Entire Cohort (N=818) RR (95% CI) |

||

|---|---|---|---|

| General contact | GPE | Cancer/HCT | |

| Race | |||

| Non-Hispanic white | 1.00 | ||

| Hispanic | 0.42 (0.22, 0.80) | ||

| Language | |||

| English | 1.00 | ||

| Spanish | 2.56 (1.35–4.87) | ||

| Gender | |||

| Male | 1.00 | ||

| Female | 0.23 (0.07, 0.78) | ||

| Age at time of HCT | |||

| 18–45 years | 1.00 | ||

| > 45 years | 0.54 (0.31, 0.92) | ||

| Age at study participation | |||

| <40 years | 1.00 | ||

| 40–<45 years | 0.68 (0.43–1.07) | ||

| 45–<55 years | 0.79 (0.54–1.16) | ||

| ≥ 55 years | 0.48 (0.30–0.77) | ||

| Follow-up since HCT | |||

| 2–5 years | 1.00 | ||

| 6–10 years | 3.39 (1.96, 5.87) | ||

| 11+ years | 8.29 (4.64, 14.81) | ||

| Concerns of future health | |||

| Concerned | 1.00 | ||

| Not concerned | 3.97 (1.95–8.09) | ||

| Current health | |||

| Good | 1.00 | ||

| Fair/Poor | 1.96 (1.38–2.80) | ||

| Current insurance | |||

| Insured | 1.00 | ||

| Uninsured | 3.82 (1.33, 11.02) | ||

| Exposure to CSA | |||

| No exposure | 1.00 | ||

| Exposed | 0.44 (0.28, 0.71) | ||

Only risk factors found to be statistically significantly associated with absence of healthcare utilization on multivariate analysis are listed in the table. No association was found in either group with other factors such as household income, type of transplant, relapse risk, and exposure to TBI, MTX.

General Medical Contact

Uninsured individuals were significantly less likely to have general medical contact than those who had medical insurance (OR=3.82, 95% CI: 1.33, 11.02). Compared to males, female HCT survivors were more likely to report general medical contact (OR (lack of reporting) = 0.23, 95% CI, 0.07–0.78).

GPE

Individuals who were mono-lingual Spanish-speaking (OR = 2.56, 95% CI: 1.35, 4.87), and those reporting fair/poor current health (OR = 1.96, 95% CI: 1.38, 2.80) were significantly more likely to report lack of GPE. Individuals who were older at the time of study participation were less likely to report lack of GPE (p for trend =0.007).

Cancer/ HCT Center Visit

Hispanic race (OR (for lack of reporting a visit) = 0.42, 95% CI: 0.22, 0.80), age >45 years at HCT (OR (lack of reporting a visit) = 0.54, 95% CI: 0.31, 0.92), exposure to cyclosporine A (OR (lack of reporting a visit) = 0.44, 95% CI: 0.28, 0.71) were significantly associated with reporting a Cancer/ HCT center visit. Increasing follow-up time (OR = 8.29, 95% CI: 4.64, 14.81) and lack of concern for future health (OR = 3.97, 95% CI: 1.95, 8.09) were associated with lack of Cancer/ HCT center visit. When stratified by type of transplant, in both autologous and allogeneic HCT groups, Hispanic race was associated with reporting a Cancer/HCT center visit (OR (lack of reporting a visit) =0.41, 95% CI: 0.14, 1.19; OR=0.41, 95% CI:.0.18, 0.92). The association is similar in magnitude but only statistically significant in allogeneic HCT group.

Multivariate analyses of risk factors for lack of healthcare utilization among non-Hispanic whites and Hispanics are shown in Table 5.

Table 5.

Risk factors for absence of healthcare utilization in non-Hispanic white and Hispanic survivors of HCT

| Non-Hispanic White | Hispanic White | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| General contact | GPE | Cancer/HCT | General contact | GPE | Cancer/HCT | |

| Follow-up (yr) | ||||||

| 2–5 | 1.00 | 1.00 | ||||

| 6–10 | 3.76 (2.11–6.71) | 3.82 (0.75,19.37) | ||||

| 11+ | 11.87 (6.56–21.47) | 5.79 (1.13, 29.80) | ||||

| Age at study participation | ||||||

| <40 | 1.00 | |||||

| 40–<45 | 0.68 (0.41–1.14) | |||||

| 45–<55 | 0.80 (0.52–1.23) | |||||

| ≥ 55 | 0.43 (0.26–0.73) | |||||

| Education | ||||||

| High school or less | 1.00 | |||||

| High school & college | 0.34 (0.16, 0.71) | |||||

| Concerns for future | ||||||

| Concerned | 1.00 | 1.00 | ||||

| Not Concerned | 5.09 (2.22–11.67) | 4.71 (1.04, 21.28) | ||||

| Current health status | ||||||

| Good | 1.00 | 1.00 | ||||

| Fair/Poor | 2.10 (1.41–3.12) | 0.47 (0.24–0.89) | ||||

| Exposure to CSA | ||||||

| No exposure | 1.00 | |||||

| Exposed | 0.54 (0.33–0.89) | |||||

Only risk factors found to be statistically significantly associated with absence of healthcare utilization on multivariate analysis are listed in the table.

Non- Hispanic Whites

GPE

Fair or poor current health (OR = 2.10, 95% CI: .41, 3.12) was significantly associated with lack of GPE. Older age at study participation was significantly associated with reporting of GPE (p for trend=0.007).

Cancer/ HCT Center Visit

Lack of concern for future health (OR=5.09, 95% CI: 2.22, 11.67) and longer follow-up (OR = 6.34 at 11+ years, 95% CI: 3.46, 11.6) were significantly associated with lack of HCT/Cancer center visit. Exposure to cyclosporine A (OR (lack of Cancer/HCT visit) = 0.54, 95% CI: 0.33, 0.89), was significantly associated with reporting Cancer / HCT Center visit.

Hispanics

General Medical Contact

Lack of concern for future health was significantly associated with reporting lack of general medical contact (OR = 4.71, 95% CI: 1.04, 21.28).

GPE

Individuals with high school or college education were more likely to report a GPE (OR (lack of GPE) = 0.34, 95% CI: 0.16, 0.71).

Cancer/ HCT Center Visit

Increasing time of follow-up was the o nly independent risk factor significantly associated with the lack of Cancer/HCT center visit for Hispanic survivors (OR = 5.79 at 11+ years, 95% CI: 1.13, 29.8).

DISCUSSION

This study of a large cohort of HCT survivors demonstrated that the prevalence of general medical contact is high even up to 11+ years after HCT. For the entire cohort of HCT survivors, individuals uninsured at the time of study participation, and male survivors were significantly less likely to have any medical contact. Monolingual Spanish-speaking Hispanics as well as those reporting fair/poor current health and those younger at study participation, were less likely to report GPE. Overall, Hispanics were more likely to report Cancer/ HCT center visits, as were HCT survivors older than 45 years of age, and those who had received cyclosporine for prophylaxis or treatment of GvHD. The likelihood of Cancer/HCT center visit decreased with time from HCT, and among those who reported lack of concern for future health.

We have described the healthcare utilization by HCT survivors in a predominantly white population in a previous report25 demonstrating that the prevalence of GPE increased with time while that of Cancer/HCT center visits decreased. However, a detailed examination of the healthcare utilization pattern reported by Hispanic HCT survivors, and its comparison with the non-Hispanic white survivors was not described, and is the subject of the current report. In the current report, although over 90% of both Hispanic and non-Hispanic white survivors reported medical contact 11+ years after HCT, significant differences were noted in the pattern of healthcare utilization between the two populations. The prevalence of GPE increased significantly with increasing time from transplantation among non-Hispanic whites, while it remained largely unchanged among the Hispanics. Self-reported visit to Cancer/HCT centers decreased over time in both groups.

Differences in healthcare utilization by Hispanic and non-Hispanic whites have been reported in childhood cancer survivors. Castellino et al compared the long-term outcomes, healthcare utilization and health-related behaviors of minority adult childhood cancer survivors to that of Caucasian survivors in the Childhood Cancer Survivor Study (CCSS)15. Regardless of the socioeconomic status, black female and Hispanic male survivors were found to have significantly less general contact with the medical system. Hispanic survivors were more likely to report a visit to a cancer center than non-Hispanic white survivors. Male gender, lack of health insurance, lack of concern for future health and age greater than 30 years at time of the study were associated with lack of reporting GPE, cancer related visits or a cancer center visit among childhood cancer survivors in another study from the CCSS cohort26 – a pattern of healthcare utilization that is quite similar to that identified in the current study.

Increased utilization of hospital-based care for cancer therapy among patients who are uninsured or insured with Medicaid has been shown in other studies.27 A cross-sectional study using the National Ambulatory Medical Care Survey and National Hospital Ambulatory Care Survey for care of cancer patients showed that patients with Medicaid were more likely to visit hospital clinics rather than private offices for treatment as compared to those who were privately insured.27 Our study demonstrates that Hispanics were more likely to utilize the Cancer/ HCT center long-term after adjustment for current insurance status, and other relevant medical factors that could have determined patterns of utilization, indicating that other sociocultural variables that remain unmeasured in this study could have influenced this pattern of utilization.

Health insurance and cost barriers to care among cancer survivors have been studied using the 1998 and 2000 National Health Interview Survey.28 Uninsured and publicly insured survivors were more likely to delay or miss care because of cost. Overall, 68% of uninsured survivors reported delaying or missing needed care. In the current study, a significantly higher number of Hispanic survivors reported lack of health insurance when compared with non-Hispanic whites, and lack of health insurance was noted to significantly decrease the general medical contact in the cohort of HCT survivors.

Hispanics experience substantial barriers to primary care. Previous studies have shown that Hispanics are more likely to report lack of continuity of care or no usual source of care.12, 13 Proficiency in English language has been postulated as one of the possible mechanisms for disparities in quality of primary care between Hispanic and non-Hispanic whites. Analysis of data on insured Latinos from National Latino and Asian American Study, a nationally representative household survey, 2002–2003, showed that low English language proficiency was associated with worse reports of quality of primary care.29 Language proficiency has also been associated with lack of utilization of preventive healthcare by Hispanics.30 Other studies have associated low English proficiency with less timeliness of care as well as poor communication with providers and less helpful staff.31

A cross sectional analysis of the Community Tracking Survey (1996–1997) that studied 18 to 64 year old adults with private or Medicaid health insurance found that the pattern of healthcare utilization for English-speaking Hispanic patients was not significantly different from non-Hispanic whites.7 In contrast, the Spanish-speaking Hispanic patients were significantly less likely to have had a physician visit, mental health visit or influenza vaccine as compared to the non-Hispanic whites.

Our study also points to English proficiency as a determinant of healthcare utilization. Spanish-speaking survivors were two times more likely to not have a GPE as compared to English-speaking survivors. Among Hispanics, higher educational status was associated with greater likelihood of having had a GPE, probably indicating that a higher educational status was more likely to be associated with proficiency in English language.

Our study demonstrated that with increasing time from HCT the survivors were less likely to report a Cancer/HCT center visit for their medical care – a finding that was true for both Hispanic and non-Hispanic whites. However, Hispanics reported a higher utilization of the Cancer/HCT center as compared to non-Hispanic whites. The reason for this difference is not clear. Similar patterns were observed for both autologous and allogeneic HCT survivors and the prevalence of chronic GvHD did not differ between Hispanic and non-Hispanic whites allogeneic survivors – so, the burden of post-HCT morbidity was unlikely to contribute to these observed differences in healthcare utilization. We speculate that prolonged utilization of the Cancer/HCT center could be a reflection of lack of a primary care provider to provide general care.

To our knowledge, this is the first study evaluating health care utilization in Hispanic survivors of HCT. However, the results of the study need to be interpreted in the context of certain limitations. The total number of Hispanic survivors is relatively small and the number of monolingual Spanish-speaking Hispanic survivors even smaller. Hence, for the most part, both English and Spanish-speaking Hispanic survivors were evaluated as a single population for the risk factors associated with lack of health care utilization. The inclusion of English-speaking Hispanics is likely to decrease the observed differences in the patterns of healthcare utilization between Hispanics and non-Hispanic whites. Nevertheless, the study was able to demonstrate significant differences between the Hispanic and non-Hispanic white survivors. Another limitation stems from the fact that healthcare utilization was determined by self-report and was not verified by healthcare providers. The reasons for the visits to Cancer/HCT centers were not solicited. These limitations not-withstanding, this study shows that Hispanic survivors of HCT continue to receive care at Cancer/HCT center several years after HCT. Future studies are needed to further investigate the factors responsible for such differences among Hispanic and non-Hispanic white populations.

Acknowledgments

Supported in part by NIH R01 CA078938 (S.B.), and Lymphoma/Leukemia Society Scholar Award for Clinical Research 2191-02 (S.B.)

REFERENCES

- 1.Census 2005. American Fact Finder. Washington DC: US Census Bureau; [Google Scholar]

- 2.Wong MD, Shapiro MF, Boscardin WJ, Ettner SL. Contribution of major diseases to disparities in mortality. N Engl J Med. 2002;347(20):1585–1592. doi: 10.1056/NEJMsa012979. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bach PB, Schrag D, Brawley OW, Galaznik A, Yakren S, Begg CB. Survival of blacks and whites after a cancer diagnosis. Jama. 2002;287(16):2106–2113. doi: 10.1001/jama.287.16.2106. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Powe BD. Eliminating cancer disparities. Cancer. 2007;109(2 Suppl):345–347. doi: 10.1002/cncr.22364. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Jemal A, Murray T, Ward E, Samuels A, Tiwari RC, Ghafoor A, et al. Cancer statistics, 2005. CA Cancer J Clin. 2005;55(1):10–30. doi: 10.3322/canjclin.55.1.10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Donaldson MYK, Lohr K, et al. Primary Care: America's Health in a New Era. Washington DC: National Academy Press; 1996. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Fiscella K, Franks P, Doescher MP, Saver BG. Disparities in health care by race, ethnicity, and language among the insured: findings from a national sample. Med Care. 2002;40(1):52–59. doi: 10.1097/00005650-200201000-00007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Lurie N, Dubowitz T. Health disparities and access to health. Jama. 2007;297(10):1118–1121. doi: 10.1001/jama.297.10.1118. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Monheit AC, Vistnes JP. Race/ethnicity and health insurance status: 1987 and 1996. Med Care Res Rev. 2000;57 Suppl 1:11–35. doi: 10.1177/1077558700057001S02. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Wagner TH, Guendelman S. Healthcare utilization among Hispanics: findings from the 1994 Minority Health Survey. Am J Manag Care. 2000;6(3):355–364. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Weinick RM, Zuvekas SH, Cohen JW. Racial and ethnic differences in access to and use of health care services, 1977 to 1996. Med Care Res Rev. 2000;57 Suppl 1:36–54. doi: 10.1177/1077558700057001S03. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Doescher MP, Saver BG, Fiscella K, Franks P. Racial/ethnic inequities in continuity and site of care: location, location, location. Health Serv Res. 2001;36(6 Pt 2):78–89. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hargraves JL, Cunningham PJ, Hughes RG. Racial and ethnic differences in access to medical care in managed care plans. Health Serv Res. 2001;36(5):853–868. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Shi L, Forrest CB, Von Schrader S, Ng J. Vulnerability and the patient-practitioner relationship: the roles of gatekeeping and primary care performance. Am J Public Health. 2003;93(1):138–144. doi: 10.2105/ajph.93.1.138. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Castellino SM, Casillas J, Hudson MM, Mertens AC, Whitton J, Brooks SL, et al. Minority adult survivors of childhood cancer: a comparison of long-term outcomes, health care utilization, and health-related behaviors from the childhood cancer survivor study. J Clin Oncol. 2005;23(27):6499–6507. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2005.11.098. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Sun CLFL, Kawashima T, Robison LL, Baker KS, Weisdorf D, Forman SJ, Bhatia S. Burdern of Long-Term Morbidity after Hematopoietic Cell Transplantation: A Report from the Bone Marrow Transplant Survivor Study (BMTSS) Blood (ASH Annual Meeting Abstracts), Nov 2007. 2007;110:832. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Perkins JL, Kunin-Batson AS, Youngren NM, Ness KK, Ulrich KJ, Hansen MJ, et al. Long-term follow-up of children who underwent hematopoeitic cell transplant (HCT) for AML or ALL at less than 3 years of age. Pediatr Blood Cancer. 2007;49(7):958–963. doi: 10.1002/pbc.21207. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Bhatia S, Robison LL, Francisco L, Carter A, Liu Y, Grant M, et al. Late mortality in survivors of autologous hematopoietic-cell transplantation: report from the Bone Marrow Transplant Survivor Study. Blood. 2005;105(11):4215–4222. doi: 10.1182/blood-2005-01-0035. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Hows JM, Passweg JR, Tichelli A, Locasciulli A, Szydlo R, Bacigalupo A, et al. Comparison of long-term outcomes after allogeneic hematopoietic stem cell transplantation from matched sibling and unrelated donors. Bone Marrow Transplant. 2006;38(12):799–805. doi: 10.1038/sj.bmt.1705531. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Andrykowski MA, Bishop MM, Hahn EA, Cella DF, Beaumont JL, Brady MJ, et al. Long-term health-related quality of life, growth, and spiritual well-being after hematopoietic stem-cell transplantation. J Clin Oncol. 2005;23(3):599–608. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2005.03.189. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Cool VA. Long-term neuropsychological risks in pediatric bone marrow transplant: what do we know? Bone Marrow Transplant. 1996;18 Suppl 3:S45–S49. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Duell T, van Lint MT, Ljungman P, Tichelli A, Socie G, Apperley JF, et al. Health and functional status of long-term survivors of bone marrow transplantation. EBMT Working Party on Late Effects and EULEP Study Group on Late Effects. European Group for Blood and Marrow Transplantation. Ann Intern Med. 1997;126(3):184–192. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-126-3-199702010-00002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Phipps S, Dunavant M, Srivastava DK, Bowman L, Mulhern RK. Cognitive and academic functioning in survivors of pediatric bone marrow transplantation. J Clin Oncol. 2000;18(5):1004–1011. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2000.18.5.1004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Flowers MEDDH. Delayed complications after hematopoeitic cell transplantation. In: Blume KGFS, Applebaum ER, editors. Thomas' Hematopoeitic Cell Transplantation. 3rd ed. Malden, Mass: Blackwell Publishing; 2004. pp. 944–961. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Shankar SM, Carter A, Sun CL, Francisco L, Baker KS, Gurney JG, et al. Health care utilization by adult long-term survivors of hematopoietic cell transplant: report from the Bone Marrow Transplant Survivor Study. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2007;16(4):834–839. doi: 10.1158/1055-9965.EPI-06-0714. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Oeffinger KC, Mertens AC, Hudson MM, Gurney JG, Casillas J, Chen H, et al. Health care of young adult survivors of childhood cancer: a report from the Childhood Cancer Survivor Study. Ann Fam Med. 2004;2(1):61–70. doi: 10.1370/afm.26. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Richardson LC, Tangka FK. Ambulatory care for cancer in the United States: results from two national surveys comparing visits to physicians' offices and hospital outpatient departments. J Natl Med Assoc. 2007;99(12):1350–1358. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Sabatino SA, Coates RJ, Uhler RJ, Alley LG, Pollack LA. Health insurance coverage and cost barriers to needed medical care among U.S. adult cancer survivors age<65 years. Cancer. 2006;106(11):2466–2475. doi: 10.1002/cncr.21879. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Pippins JR, Alegria M, Haas JS. Association between language proficiency and the quality of primary care among a national sample of insured Latinos. Med Care. 2007;45(11):1020–1025. doi: 10.1097/MLR.0b013e31814847be. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Solis JM, Marks G, Garcia M, Shelton D. Acculturation, access to care, and use of preventive services by Hispanics: findings from HHANES 1982–84. Am J Public Health. 1990;80 Suppl:11–19. doi: 10.2105/ajph.80.suppl.11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Weech-Maldonado R, Morales LS, Elliott M, Spritzer K, Marshall G, Hays RD. Race/ethnicity, language, and patients' assessments of care in Medicaid managed care. Health Serv Res. 2003;38(3):789–808. doi: 10.1111/1475-6773.00147. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]