Abstract

Background

Hypoxia is an important risk factor for development of necrotizing enterocolitis (NEC) in premature infants. Hypoxia-inducible factor (HIF)-1 is a transcription factor that plays a critical role in cellular responses to hypoxia and can be induced by phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase (PI3-K) pathway. Activation of the PI3-K and regulation of HIF-1 during NEC have not been elucidated.

Methods

NEC was induced in 3 day-old neonatal mice using hypoxia and artificial formula feedings. Mice were divided into 3 treatment groups: (1) NEC alone, (2) NEC with insulin-like growth factor (IGF)-I or (3) NEC with Akt1 siRNA treatment. Animals were sacrificed and intestinal sections were harvested for protein analysis, H&E and immunohistochemical staining.

Results

In vivo model of NEC produced intestinal injury associated with increased protein expression of HIF-1α, pAkt, PARP and caspase-3 cleavage. Pretreatment with IGF-1 attenuated HIF-1α response. In contrast, targeted inhibition of Akt1 completely abolished NEC-induced expression of pAkt and upregulated HIF-1α activation.

Conclusions

NEC activates important protective cellular responses to hypoxic injury such as HIF-1α and PI3-K/Akt in neonatal gut. Hypoxia-mediated activation of pro-survival signaling during NEC may be modulated with growth factors, thus suggesting a potential therapeutic option in the treatment of neonates with NEC.

Keywords: HIF-1α, PI3-K, Akt1, IGF-1, oxidative stress, necrotizing enterocolitis

Introduction

Necrotizing enterocolitis (NEC), characterized by inflammation, ischemia and necrosis of the intestine, remains a serious life-threatening gastrointestinal emergency in low-birth weight premature infants. The overall incidence of NEC has steadily risen as a result of improved survival of premature infants. A variety of well-established risk factors, such as hypoxia, impaired intestinal barrier and immunity, enteric feeding and abnormal bacterial colonization, is known to contribute to complex pathophysiology of NEC.1 However, hypoxia as a result of transient ischemic injury is thought to be a critical initial insult leading to multitude of inflammatory responses in the gut.

Hypoxia triggers various systemic, cellular, and metabolic responses necessary for tissues to adapt to low oxygen conditions and activates hypoxia-inducible factor (HIF)-1, a transcription factor essential in regulating hypoxia-induced gene expression. HIF-1, a heterodimer consisting of constitutively expressed α and β subunits, contributes to O2 homeostasis, cell survival, erythropoiesis, wound healing, and regulation of vascular tone.2 The exact signaling mechanisms involved in the regulation of hypoxia-induced activation of HIF-1α are not fully understood. Among many, phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase (PI3-K) pathway, mitochondrial ROS and diacylglycerol kinase are required to stabilize HIF-1α and to allow for nuclear translocation, hetero-dimerization with HIF-1β, transcriptional activation and interaction with proteins.3-6 The PI3-K pathway along with its downstream effector, Akt, is known to induce HIF-1α activation in normoxia;7 however, the downstream targets of Akt, such as GSK3β or forkhead transcription factors, have also been shown to negatively regulate HIF-1α expression.8-10

PI3-K is a major cellular protective pathway that is activated during oxidative injury and apoptosis to mediate cell survival. We have previously shown that oxidative stress activates the PI3-K survival pathway in vitro;11 this response was further augmented with insulin-like growth factor (IGF)-1 in intestinal epithelial cells.12 A recent study demonstrated that upregulation of HIF-1α occurs in intestinal mucosa and submucosa in patients with inflammatory bowel diseases;13 however, intestinal HIF-1α expression during NEC is unknown. In the present study, we sought to determine whether intestinal HIF-1α activation occurs during NEC, and to further examine PI3-K pathway regulation of this process in vivo.

Materials and Methods

Cell line, reagents and antibodies

Rat intestinal epithelial (RIE)-1 cells (a gift from Dr. Kenneth D. Brown; Cambridge Research Station, Cambridge, U.K.) were maintained in Dulbecco's modified Eagle medium (DMEM) supplemented with 5% fetal bovine serum and cultured at 37°C under an atmosphere containing 5% CO2. Tissue culture media and reagents were obtained from Mediatech, Inc (Herndon, VA). Recombinant rat insulin-like growth factor (IGF)-1 was from Diagnostic Systems Laboratories (Webster, TX). Hydrogen peroxide (H2O2), mouse monoclonal anti-β-actin antibody and other reagents were purchased from Sigma (St. Louis, Mo). LabTek® chambered 1.0 borosilicate cover glass system (NUNC International, Rochester, NY), AlexaFluor® 647-labeled goat anti-rabbit IgG and Höechst 33342 (Molecular Probes, Eugene, OR) were used for immunofluorescent studies. Rabbit polyclonal anti-phospho-Akt (Ser 473; Akt1-specific), anti-HIF-1α, anti-Akt1, anti-Akt, anti-PARP, and anti-caspase-3 antibodies were purchased from Cell Signaling Technology (Beverly, MA). Polyvinylidene difluoride (PVDF) membranes were from Millipore Corp. (Bedford, MA). Enhanced chemiluminescence (ECL)Plus system was purchased from Amersham Biosciences (Piscataway, NJ).

In vivo NEC model

Timed pregnant Swiss-Webster mice were purchased (Charles River Labs, Pontage, MI) and pup littermates were obtained from litters at 72 h of life. They were randomized to three treatment groups: (1) NEC alone, (2) NEC with a single IGF-1 pretreatment (10 μg/g body weight; i.p.) 1 h prior to initial hypoxic insult, and (3) NEC with Akt1 siRNA (i.p.; q 48 h). All mice in NEC groups were housed in a water bath at 37°C. They were hand-fed KMR liquid milk replacer formula (0.3 cc/g/day; q 3 h) using an animal feeding needle (24 g, ballpoint; Popper & Sons, New Hyde Park, NY). Control animals received vehicle injection(s) according to the protocol and were maternally reared. All pups' body weights were recorded daily; urination and defecation were induced b.i.d. by gentle stimulation of the anogenital region.

To induce NEC, pups were stressed twice daily with hypoxia by placing them in a plexi glass chamber, breathing 5% oxygen for 10 min (30 min prior to scheduled feeding). Each mouse was monitored daily for the clinical severity of NEC by assessing the level of activity, oral intake, weight change and abdominal exam findings. Mice that developed abdominal distention, respiratory distress and lethargy during the first 96 h of the experiment were sacrificed. After 96 h, all surviving mice were sacrificed and distal ileum was harvested for assays. Segments of ileum were fixed in formalin and stored in 70% ethanol for paraffin embedding. The remaining ileum was snap frozen in liquid nitrogen for protein analysis. Histological changes were assessed and scored by a pathologist (H.K.H) in a blinded fashion.

In vivo and in vitro siRNA transfection

For in vivo siRNA delivery, mouse siSTABLE SMARTpool Akt1 and non-targeting control (NTC) siRNA duplexes, chemically modified to extend siRNA stability in vivo, were synthesized by Customer SMARTpool siRNA Design from Dharmacon (Lafayette, CO). These duplexes were diluted with a liposomal transfection agent, DOTAP (Roche Applied Science, Germany), and injected into the abdominal cavity.

Immunoblot analysis

HIF-1α protein was analyzed in tissue lysates prepared from full-thickness mouse intestines and clarified by centrifugation (13000 × g for 20 min at 4°C). RIE-1 cells were treated with H2O2 (500 μM) for 1 h and whole cell lysates were stored at −80°C. Protein concentrations were determined using Bradford method.14 Equal amounts of total protein (100 μg for tissues; 30 μg for cells) were loaded onto NUPAGE 4-12% Bis-Tris Gel and transferred to PVDF membranes, incubated in a blocking solution for 1 h (Tris-buffered saline containing 5% nonfat dried milk and 0.1 % Tween 20), and then incubated with primary antibody overnight at 4°C and horseradish peroxidase-conjugated secondary antibody. Anti-β-actin antibody was used for protein loading control. HIF-1α, phospho-Akt, Akt1, total Akt, PARP and caspase-3 antibodies were used to probe membranes. The immune complexes were visualized by ECLPlus. Quantitative densitometry (Image J, NIH, Bethesda, MD) was used to assess signals.

Tissue hypoxia measurement

To characterize intestinal hypoxia in vivo, pups from control and NEC groups were injected with pimonidazole hydrochloride (Hypoxiprobe™-1; 60 mg/kg; i.p.), a sensitive hypoxia marker that accurately measures cellular oxygen gradient, 1 h prior to sacrifice. Intestines were harvested, fixed, paraffin-embedded and sectioned (5 μm) for immunoperoxidase staining according to a manufacturer's protocol (Chemicon International, Temecula, CA), and were visualized with light microscopy.

Immunohistochemistry

Paraffin-embedded distal ileum samples were sectioned (5 μm), deparaffinized, rehydrated, washed, and unmasked with sodium citrate buffer (pH 6.0). After an endogenous peroxidase blocking step, sections were blocked with Dako Protein Block Serum-free solution and incubated with rabbit anti-phospho-Akt or rabbit anti-Akt polyclonal antibodies overnight at 4°C. The anti-rabbit secondary antibody was applied (DakoCytomation EnVision®+System-HRP (DAB) kit, Carpinteria, CA), followed by DAB chromogen staining. Slides were washed, counterstained with hematoxylin, dehydrated and cover slipped. Control sections were incubated with rabbit IgG instead of the anti-phospho-Akt.

Statistical analysis

Body weights for all groups were analyzed using ANOVA. All effects and interactions were assessed at the 0.05 level of significance. Multiple comparisons for pair-wise treatment groups were conducted using Fisher's exact test with Bonferroni adjustment.

Results

In vivo NEC induces PI3-K pathway activation and upregulates HIF-1α expression

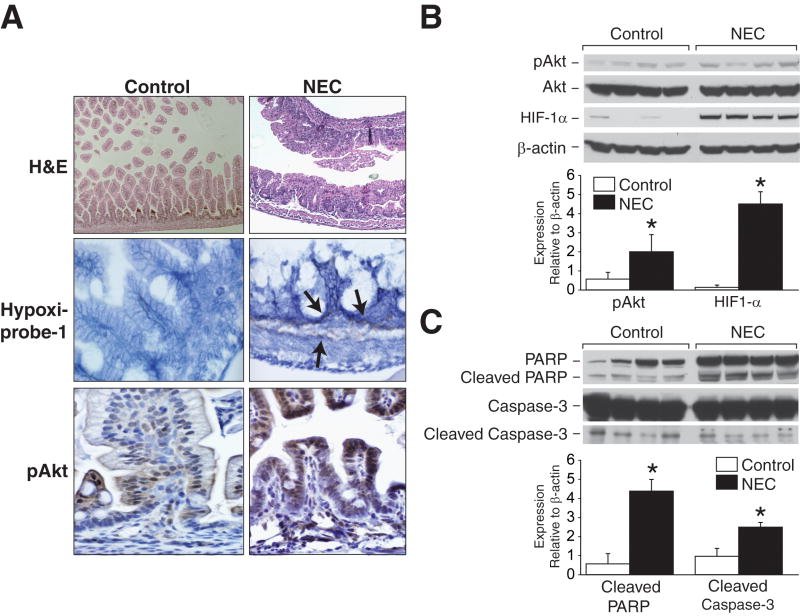

Our in vivo NEC model produced moderate intestinal injury, as characterized by marked blunting of villous tips with inflammatory cell infiltration (Fig. 1A). In addition, there was significant tissue hypoxia detected in lamina propria and submucosa of injured intestines. In vivo NEC also induced increased expression of pAkt shown as dark brown staining in injured mucosa when compared with control (Fig. 1A). Correlative to our previous reports demonstrating intestinal epithelial cell activation of PI3-K/Akt in vitro model of NEC11, 12, our in vivo NEC also showed increased Akt phosphorylation in the intestine by Western blot analysis (Fig. 1B), therefore, further implicating activated PI3-K/Akt pathway as the central survival signaling mechanism during NEC.

Fig 1. In vivo NEC activates PI3-K/Akt pathway and increases HIF-1α expression.

(A) Blunting of villous tips, submucosal separation/edema are present in NEC sections (first row). Hypoxia is markedly expressed in intestinal lamina propria and submucosa during NEC (second row; arrows). Increased intestinal pAkt expression is noted during in vivo NEC (third row). (B) Extracted total proteins from ileal segments were analyzed by Western blotting for the expression of HIF-1α, pAkt and total Akt. NEC induced significant increase in pAkt and HIF-1α expression (* p < 0.05 vs. control). Equal β-actin levels indicate even loading. (C) NEC intestinal tissues were harvested and analyzed for apoptotic protein markers, PARP and caspase-3. NEC resulted in significantly increased cleavage of PARP and caspase-3 (* p < 0.05 vs. control).

NEC induced significant activation of intestinal HIF-1α when compared with control (Fig. 1B). This finding supports our hypothesis of hypoxia-induced intestinal cell injury and HIF-1α activation orchestrating critical cellular responses during NEC. The activation of NEC-induced apoptotic signaling in injured intestinal tissues was also confirmed by Western blot analysis. We observed significant increase in cleaved products of apoptotic molecules, PARP and caspase-3 (Fig. 1C). Collectively, these data suggest that in vivo NEC model induces intestinal injury, adaptive intestinal HIF-1α upregulation and PI3-K/Akt survival pathway activation.

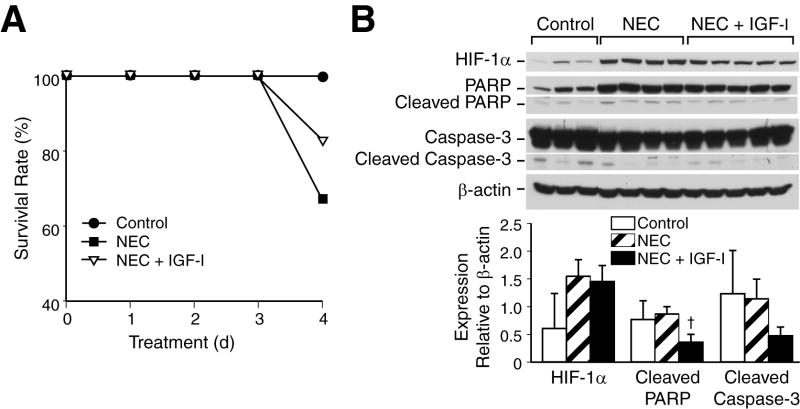

HIF-1α activation in intestinal epithelial cells

We next assessed HIF1-α expression after H2O2 treatment in rat intestinal epithelial cells. RIE-1 cells were treated with H2O2 for 1 h and evaluated with scanning laser confocal microscopy for intracellular HIF-1α accumulation. H2O2 treatment induced significant increase in cytoplasmic HIF-1α expression without nuclear translocation; this increase in fluorescence was nearly 10-fold when compared with control (Fig. 2A). Similarly, Western blot analysis showed significant HIF-1α response in H2O2-treated cells when compared to control cells (Fig. 2B), hence, further supporting our hypothesis of enhanced HIF-1α expression during in vivo NEC.

Fig 2. H2O2 treatment induces HIF-1α expression in RIE-1 cells.

(A) RIE-1 cells (1×104/well) were treated with H2O2 (500 μM) for 1h, and then incubated with HIF-1α antibody, AlexaFluor® 647-labeled goat anti-rabbit IgG and Höechst 33342 nuclear stain. They were visualized using 1.0 Zeiss LSM 510 UV Meta laser scanning confocal microscopy. H2O2 treatment resulted in significant increase in intracellular HIF-1α activation and accumulation by nearly 10-fold in RIE-1 cells. (Zeiss LSM Image software). (B) RIE-1 cells were treated with H2O2 for 1h, the protein was extracted for Western blot analysis. H2O2 treatment also increased protein expression of HIF-1α. Equal β-actin levels indicate even loading.

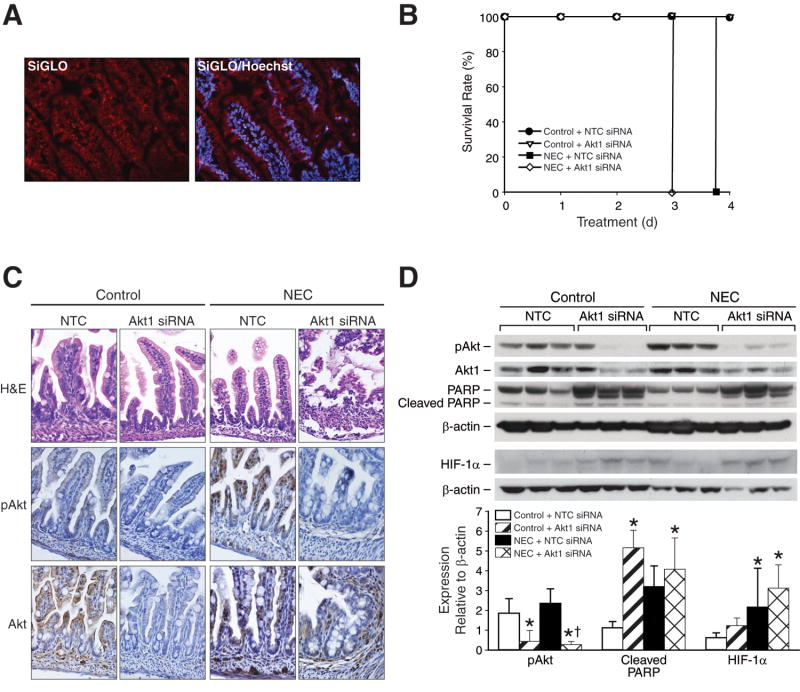

IGF-1 attenuates intestinal injury and HIF-1α expression during NEC

IGF-1 is a potent inducer of the PI3-K/Akt pathway which plays an important role in cellular growth and survival. To examine the effects of IGF-1 on PI3-K pathway activation during NEC, we treated mice pups with a single injection of IGF-1 prior to NEC (hypoxia and formula feedings). IGF-1 pretreated mice demonstrated higher survival rates when compared to NEC alone (Fig. 3A), and these results were reproduced in a separate study (results not shown). This protective effect of IGF-1 treatment in NEC mice is an important in vivo finding that supports our recent in vitro findings,12 suggesting a critical role for PI3-K pathway in protecting injured intestinal tissues during NEC. All NEC pups showed clinically significant disease progression with decreased activity, poor oral intake and abdominal distention; however, no significant improvements on these parameters were noted with IGF-1 treatment due to small sample size. IGF-1-induced PI3-K pathway stimulation decreased intestinal expression of cleaved PARP and caspase-3 (Fig. 3B), suggesting an anti-apoptotic role during NEC.

Fig 3. IGF-1 treatment improves mice survival during NEC and attenuates apoptosis, HIF-1α expression during NEC.

(A) Neonatal mice were randomized into control (n=5), NEC alone (n=6) and IGF-1 + NEC (n=6) groups, and then sacrificed after 96 h. Neonatal mice in a NEC group with single IGF-1 injection (10 μg/g; i.p.) showed higher survival rate than pups in NEC alone group (83.3% vs. 66.6%). (B) Ileal segments were harvested and analyzed by Western blotting for the expression of intestinal HIF-1α, caspase-3 and PARP († p < 0.05, NEC alone vs. NEC + IGF-1). IGF-1 pretreatment attenuated NEC-induced cleavage of PARP and caspase-3, and decreased HIF-1α protein levels. Equal β-actin levels indicate even loading.

Under normoxic conditions, the growth factor stimulation is known to upregulate HIF-1α via enhanced PI3-K/Akt survival pathway activation.7 We analyzed intestinal tissues by Western blotting to assess the effect of IGF-1 on HIF-1α expression and regulation during NEC. NEC induced pronounced HIF-1α response, as shown in Figure 1; surprisingly, this response was attenuated by IGF-1 pretreatment nearly by half (Fig. 3B). Growth factor stimulation of PI3-K pathway in normoxia or hypoxia is thought to exert an additive effect on HIF-1α activation.15-20 Interestingly, our findings elucidate a different regulatory mechanism for PI3-K pathway in HIF-1α activation during in vivo NEC. IGF-1 pretreatment may have induced an early PI3-K/Akt pathway stimulation which resulted in peaked HIF-1α activation with subsequent diminished signal over time. Collectively, our in vivo and in vitro data suggest that the PI3-K/Akt upregulation improves survival and plays a negative regulatory role in HIF-1α expression during NEC.

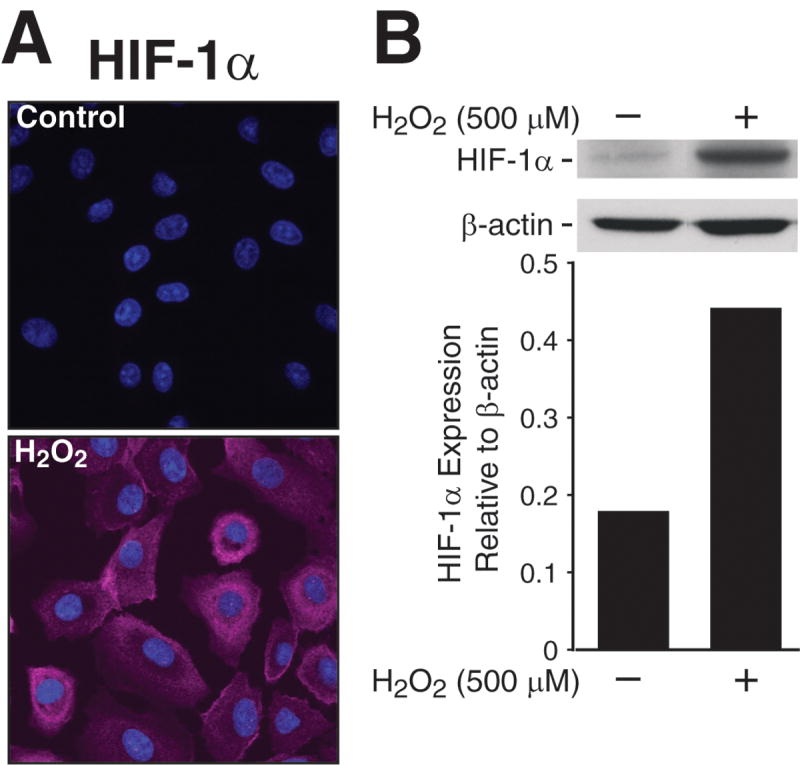

Targeted Akt1 inhibition decreases survival and upregulates HIF-1α during NEC

To further clarify the role of PI3-K pathway in survival and HIF-1α regulation during NEC, we silenced Akt1, a PI3-K downstream effector, and assessed its effects on NEC severity, pups' survival and apoptotic protein markers. To confirm siRNA transfection efficiency, we injected 3-day old mice with siGLO Lamin A/C siRNA (Dharmacon, Lafayette, CO) intraperitoneally and sacrificed at 24 h. Intestinal cryosections showed excellent siGLO Lamin A/C siRNA localization (Fig. 4A). We proceeded with targeted Akt1 silencing, which resulted in worsening NEC severity. Mice pups treated with Akt1 siRNA demonstrated decreased activity, oral intake and increased abdominal distention at 48 h (data not shown). Knockdown of Akt1 led to rapid demise of mice; all of the treated pups became increasingly distressed by day 3, shortly after a second siRNA treatment, and had to be sacrificed promptly. NEC pups receiving NTC became clinically worse by day 4 and were sacrificed a few hours before the rest of the mice (Fig. 4B). Immunohistochemical analysis of ileal sections for pAkt and Akt expression demonstrated suppressed phosphorylation of pAkt and relative decrease in total Akt levels in Akt1 siRNA groups (Fig. 4C). Western blot analysis confirmed that the Akt1 siRNA duplexes effectively silenced Akt1 and blocked Akt phosphorylation in both control and NEC groups (Fig. 4D). Moreover, Akt silencing resulted in increased expression of cleaved PARP when compared to NEC alone, suggesting that PI3-K/Akt activation is crucial for intestinal cell survival during NEC-induced intestinal injury.

Fig 4. Akt1 siRNA induces HIF-1α upregulation and decreases survival during NEC.

(A) Intestinal cryosections from healthy 3-day old mice (n=3) injected with siGLO Lamin A/C siRNA i.p. were stained with Höechst 33342 nuclear stain. Intestinal sections showed excellent siGLO Lamin A/C siRNA transfection and localization in neonatal mouse intestine (Nikon fluorescent microscopy). (B) Neonatal mice were randomized into control and NEC groups to receive either NTC or Akt1 siRNA i.p injections for 96 h. Five mice were used for each treatment group. Neonatal mice in a NEC Akt1 siRNA group had significantly higher mortality rate than pups in NEC NTC siRNA. (C) Intestinal sections stained with H&E showed mucosal and submucosal injury in NEC NTC and NEC Akt1 siRNA groups (first row). Intestinal pAkt and Akt levels were attenuated in Akt1 siRNA-treated groups during NEC (second and third rows). (D) Ileal segments were harvested and analyzed by Western blotting for the expression of intestinal HIF-1α, pAkt, Akt1 and PARP. Targeted Akt1 inhibition enhaced NEC-induced HIF-1α protein levels, enhanced PARP cleavage, and effectively silenced activation of Akt1 in control and NEC groups (* p < 0.05 vs. control; † p < 0.05, NEC Akt1 siRNA vs. NEC NTC siRNA). Equal β-actin levels indicate even loading.

Next, we examined the effects of Akt1 silencing on intestinal HIF-1α expression during NEC. Targeted in vivo inhibition of Akt1 induced increased intestinal HIF-1α expression in both control and NEC groups when compared to non-targeted controls (Fig. 4C). Knockdown of Akt1 during NEC resulted in significant HIF-1α upregulation, thus further suggesting an important role for PI3-K/Akt pathway-dependent regulation of HIF-1α in injured intestinal tissues. Moreover, this also supports our findings of attenuated HIF-1α response with IGF-1 treatment in NEC, as shown in Figure 3B. Interestingly, the non-targeted NEC tissues did not show pronounced HIF-1α response as did the NEC groups in Figures 1B and 3B. The down-regulation of HIF-1α expression may have resulted from non-specific effects of NTC. Taken together, these results suggest that the PI3-K-dependent regulation of intestinal HIF-1α involves a negative regulatory mechanism during NEC.

Discussion

Intestinal cellular signaling pathways involved in the pathogenesis of NEC remain largely unclear. In this study, we show that activation of PI3-K/Akt pathway along with HIF1-α occurs in the intestine during in vivo NEC. We also show that exogenous IGF-1, a strong inducer of PI3-K/Akt pathway, improves neonatal pups' survival during NEC. In contrast, targeted silencing of Akt1 significantly increases mortality of pups with induced NEC, further accentuating PI3-K/Akt as an important survival signaling pathway during NEC.

NEC remains a major gastrointestinal surgical emergency in premature and low birth weight infants. Hypoxic/ischemic insult is thought to be an important initial factor contributing to the development of NEC. Hypoxia can induce injury, activation of HIF-1, apoptotic signaling, and necrosis, as well as a range of physiological responses necessary for cellular survival and ability to cope with low oxygen levels. Central to O2 homeostasis during fetal and postnatal life,21 tissue repair, ischemia and tumor growth,22, 23 HIF-1α can regulate hypoxia-induced apoptosis in concert with many factors to either induce or inhibit apoptosis.24 However, its role in the intestine during NEC is unknown.

In normoxia, the PI3-K/Akt pathway stimulation leads to increased HIF-1α activation; however, the role of PI3-K/Akt pathway in the regulation of HIF-1α in hypoxia remains controversial. Using our in vivo model, we found that the intestinal HIF-1α activation occurs in neonatal mice during NEC. Contrary to our hypothesis, the PI3-K/Akt pathway stimulation with exogenous IGF-1 attenuates HIF-1α response during in vivo NEC model. Furthermore, the silencing of HIF-1α upstream regulator Akt1, ubiquitously expressed Akt isoform, leads to pronounced HIF-1α upregulation in both control and NEC groups. Our findings suggest that PI3-K/Akt pathway may negatively regulate intestinal HIF-1α expression in protecting intestinal tissues during in vivo NEC. However, it is yet unclear whether this interaction is a mechanism of intestinal injury or cell protective response during NEC. There may be several factors involved in regulating HIF-1α response to NEC. The prolonged hypoxic stress and downstream targets of Akt, such as GSK3β or forkhead transcription factors, are some of the potential negative regulators HIF-1α that may result in decreased HIF-1α accumulation.10,25

PI3-K-mediated signaling is central to intestinal survival. Our in vivo NEC model induced significant intestinal activation of PI3-K/Akt in neonatal mice. Hence, modulating PI3-K activation with exogenous IGF-1 and Akt1 siRNA further elucidated its protective role during NEC. The most notable finding of this study is the improved survival in neonatal pups with IGF-1 pretreatment and associated decrease in apoptotic molecules during NEC. This response provides strong evidence for the protective role of PI3-K/Akt in injured intestinal tissues, and possibly other organ systems, during in vivo NEC. In contrast, the PI3-K inhibition with Akt1 siRNA proved to be detrimental to neonatal pups with NEC, and led to early development of clinically severe NEC and high mortality. When taken together, our findings support the hypothesis that the PI3-K/Akt signaling cascade is critical to intestinal survival, mechanistic understanding and therapeutic intervention during NEC.

Neonatal survival is the most important clinical outcome during NEC. We have demonstrated that modulating survival signaling with a growth factor is protective to neonatal gut, and possibly other organ systems, during NEC-induced injury. Our in vivo findings clearly demonstrate anti-apoptotic effects of IGF-1 during NEC. Hence, upregulation of PI3-K/Akt pathway is vital to cellular survival; it may protect neonatal gut and improve overall survival during injury. Future studies aimed at elucidating the intricate molecular signaling mechanisms involved in PI3-K/Akt cascade may help attenuate intestinal injury in neonates with NEC.

Acknowledgments

We thank Karen Martin for manuscript preparation and Tatsuo Uchida for statistical analysis. This work was supported by grants RO1 DK61470, RO1 DK48498 and PO1 DK35608 from the National Institutes of Health and grant #8580 from Shriners Burns Hospital.

Footnotes

Presented at the 2nd Annual Academic Surgical Congress, February 6-9, 2007, Phoenix, AZ

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Sibbons P, Spitz L, van Velzen D, Bullock GR. Relationship of birth weight to the pathogenesis of necrotizing enterocolitis in the neonatal piglet. Pediatr Pathol. 1988;8:151–62. doi: 10.3109/15513818809022292. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Schumacker PT. Hypoxia-inducible factor-1 (HIF-1) Crit Care Med. 2005;33:S423–5. doi: 10.1097/01.ccm.0000191716.38566.e0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Zundel W, Schindler C, Haas-Kogan D, Koong A, Kaper F, Chen E, et al. Loss of PTEN facilitates HIF-1-mediated gene expression. Genes Dev. 2000;14:391–6. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Zhong H, Chiles K, Feldser D, Laughner E, Hanrahan C, Georgescu MM, et al. Modulation of hypoxia-inducible factor 1alpha expression by the epidermal growth factor/phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase/PTEN/AKT/FRAP pathway in human prostate cancer cells: implications for tumor angiogenesis and therapeutics. Cancer Res. 2000;60:1541–5. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Chandel NS, Maltepe E, Goldwasser E, Mathieu CE, Simon MC, Schumacker PT. Mitochondrial reactive oxygen species trigger hypoxia-induced transcription. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1998;95:11715–20. doi: 10.1073/pnas.95.20.11715. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Chandel NS, McClintock DS, Feliciano CE, Wood TM, Melendez JA, Rodriguez AM, et al. Reactive oxygen species generated at mitochondrial complex III stabilize hypoxia-inducible factor-1alpha during hypoxia: a mechanism of O2 sensing. J Biol Chem. 2000;275:25130–8. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M001914200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Jiang BH, Jiang G, Zheng JZ, Lu Z, Hunter T, Vogt PK. Phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase signaling controls levels of hypoxia-inducible factor 1. Cell Growth Differ. 2001;12:363–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Sodhi A, Montaner S, Miyazaki H, Gutkind JS. MAPK and Akt act cooperatively but independently on hypoxia inducible factor-1alpha in rasV12 upregulation of VEGF. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2001;287:292–300. doi: 10.1006/bbrc.2001.5532. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Chen EY, Mazure NM, Cooper JA, Giaccia AJ. Hypoxia activates a platelet-derived growth factor receptor/phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase/Akt pathway that results in glycogen synthase kinase-3 inactivation. Cancer Res. 2001;61:2429–33. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Mottet D, Dumont V, Deccache Y, Demazy C, Ninane N, Raes M, et al. Regulation of hypoxia-inducible factor-1alpha protein level during hypoxic conditions by the phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase/Akt/glycogen synthase kinase 3beta pathway in HepG2 cells. J Biol Chem. 2003;278:31277–85. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M300763200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Zhou Y, Wang Q, Evers BM, Chung DH. Signal transduction pathways involved in oxidative stress-induced intestinal epithelial cell apoptosis. Pediatr Res. 2005;58:1192–7. doi: 10.1203/01.pdr.0000185133.65966.4e. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Baregamian N, Song J, Jeschke MG, Evers BM, Chung DH. IGF-1 protects intestinal epithelial cells from oxidative stress-induced apoptosis. J Surg Res. 2006;136:31–7. doi: 10.1016/j.jss.2006.04.028. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Giatromanolaki A, Sivridis E, Kouskoukis C, Gatter KC, Harris AL, Koukourakis MI. Hypoxia-inducible factors 1alpha and 2alpha are related to vascular endothelial growth factor expression and a poorer prognosis in nodular malignant melanomas of the skin. Melanoma Res. 2003;13:493–501. doi: 10.1097/00008390-200310000-00008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Bradford MM. A rapid and sensitive method for the quantitation of microgram quantities of protein utilizing the principle of protein-dye binding. Anal Biochem. 1976;72:248–54. doi: 10.1016/0003-2697(76)90527-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Treins C, Giorgetti-Peraldi S, Murdaca J, Monthouel-Kartmann MN, Van Obberghen E. Regulation of hypoxia-inducible factor (HIF)-1 activity and expression of HIF hydroxylases in response to insulin-like growth factor I. Mol Endocrinol. 2005;19:1304–17. doi: 10.1210/me.2004-0239. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Bardos JI, Ashcroft M. Negative and positive regulation of HIF-1: a complex network. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2005;1755:107–20. doi: 10.1016/j.bbcan.2005.05.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Wang X, Deng J, Boyle DW, Zhong J, Lee WH. Potential role of IGF-I in hypoxia tolerance using a rat hypoxic-ischemic model: activation of hypoxia-inducible factor 1alpha. Pediatr Res. 2004;55:385–94. doi: 10.1203/01.PDR.0000111482.43827.40. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Chavez JC, LaManna JC. Activation of hypoxia-inducible factor-1 in the rat cerebral cortex after transient global ischemia: potential role of insulin-like growth factor-1. J Neurosci. 2002;22:8922–31. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.22-20-08922.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Fukuda R, Hirota K, Fan F, Jung YD, Ellis LM, Semenza GL. Insulin-like growth factor 1 induces hypoxia-inducible factor 1-mediated vascular endothelial growth factor expression, which is dependent on MAP kinase and phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase signaling in colon cancer cells. J Biol Chem. 2002;277:38205–11. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M203781200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Burroughs KD, Oh J, Barrett JC, DiAugustine RP. Phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase and mek1/2 are necessary for insulin-like growth factor-I-induced vascular endothelial growth factor synthesis in prostate epithelial cells: a role for hypoxia-inducible factor-1? Mol Cancer Res. 2003;1:312–22. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Huang ST, Vo KC, Lyell DJ, Faessen GH, Tulac S, Tibshirani R, et al. Developmental response to hypoxia. Faseb J. 2004;18:1348–65. doi: 10.1096/fj.03-1377com. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Berra E, Ginouves A, Pouyssegur J. The hypoxia-inducible-factor hydroxylases bring fresh air into hypoxia signalling. EMBO Rep. 2006;7:41–5. doi: 10.1038/sj.embor.7400598. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Corbucci GG, Marchi A, Lettieri B, Luongo C. Mechanisms of cell protection by adaptation to chronic and acute hypoxia: molecular biology and clinical practice. Minerva Anestesiol. 2005;71:727–40. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Greijer AE, van der Wall E. The role of hypoxia inducible factor 1 (HIF-1) in hypoxia induced apoptosis. J Clin Pathol. 2004;57:1009–14. doi: 10.1136/jcp.2003.015032. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Emerling BM, Platanias LC, Black E, Nebreda AR, Davis RJ, Chandel NS. Mitochondrial reactive oxygen species activation of p38 mitogen-activated protein kinase is required for hypoxia signaling. Mol Cell Biol. 2005;25:4853–62. doi: 10.1128/MCB.25.12.4853-4862.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]