Abstract

In this paper, we describe the fabrication and evaluation of a multilayer microchip device that can be used to quantitatively measure the amount of catecholamines released from PC 12 cells immobilized within the same device. This approach allows immobilized cells to be stimulated on-chip and, through rapid actuation of integrated microvalves, the products released from the cells are repeatedly injected into the electrophoresis portion of the microchip, where the analytes are separated based upon mass and charge and detected through post-column derivatization and fluorescence detection. Following optimization of the post-column derivatization detection scheme (using naphthalene-2,3-dicarboxaldehyde and 2-β-mercaptoethanol), off-chip cell stimulation experiments were performed to demonstrate the ability of this device to detect dopamine from a population of PC 12 cells. The final 3-dimensional device that integrates an immobilized PC 12 cell reactor with the bilayer continuous flow sampling/electrophoresis microchip was used to continuously monitor the on-chip stimulated release of dopamine from PC 12 cells. Similar dopamine release was seen when stimulating on-chip versus off-chip yet the on-chip immobilization studies could be carried out with 500 times fewer cells in a much reduced volume. While this paper is focused on PC 12 cells and neurotransmitter analysis, the final device is a general analytical tool that is amenable to immobilization of a variety of cell lines and analysis of various released analytes by electrophoretic means.

Introduction

The use of microchip-based devices for studying cellular systems is a research area that has grown significantly over the past decade.1-4 While an appreciable number of papers have been published in the general area of “cells-on-a-chip”, most applications have been aimed at operations such as cell culture,1,5 cell sorting and handling,6,7 and single cell analysis.3,4,8,9 In terms of analyzing cellular content, microfluidic devices are emerging as attractive platforms due to their potential of performing automated and controlled sample manipulation (e.g., sample clean-up, lysis, separation, dilution, derivatization, etc.) in a single device.1,2 Most of the work involving cellular analyses has involved the use of single cells.3,4 Recent work has shown that microchip devices can be used to integrate single cell lysis, derivatization of the lysed sample, and electrophoretic-based separation of the cellular content.8,9

While much information can be garnered from single cell studies, there is also interest in culturing layers of adherent cells in microfluidic devices.1,10 By integrating a method to analyze the chemicals that are released from the cultured cells it will be possible to investigate processes such as how cells act in concert and how populations of cells communicate with each other. In a sense, such a device is an in vitro-based mimic of an in vivo system that also integrates an analysis scheme.2 There have been a few reports of such integrated mimics;11-13 however, to our knowledge, there have been no reports of an all encompassing device that can integrate cell culture and analysis techniques like electrophoresis with fluorescence detection so that a wide variety of chemicals (such as neurotransmitters) that are released from cells can be separated and detected in close to real time. Our group is interested developing such a device, with the long-term goal of investigating nitric oxide-mediated mechanisms of dopaminergic degeneration in neuronal systems. Ideally, integrating a neuronal mimic with a separation and detection scheme will enable analytical measurements with high temporal resolution for monitoring rapid changes in cellular exocytotic events.

We have previously published a method that enables the culturing and immobilization of PC 12 cells into rectangular PDMS microchannels.14 The PC 12 cell line can serve as a model dopaminergic system for the development of methods to monitor synaptic or exocytotic release, mostly due to the fact that they synthesize, store, release, and reuptake dopamine and norepinephrine.15 We previously showed that PC 12 cells immobilized in PDMS channels are bioresponsive by detecting the stimulated release of catecholamines via integrated carbon ink microelectrodes.14 However, electrochemistry is unable to differentiate between the catecholamines released from the PC 12 cells (dopamine and norepinephrine).16 These catecholamines can be readily separated through electrophoresis; therefore, to enable differentiation of dopamine and norepinephrine released from an immobilized layer of PC 12 cells (as well as, in the future, catecholamine/nitric oxide reaction products), there is a need to couple the continuous flow associated with an immobilized cell reactor to microchip electrophoresis. Recently, we have also published work on the development of a reversibly-sealed bilayer microchip that uses integrated pneumatic valves to couple continuous flow sampling to microchip electrophoresis.17 With such a device, one can discretely inject a sample plug from a hydrodynamically-pumped continuous flow stream as well as monitor concentration changes that occur on-chip through the rapid actuation of the pneumatic valves.17,18

In this paper, we describe the fabrication and evaluation of a multilayer microchip for quantitatively measuring the amount of catecholamines released from PC 12 cells immobilized within the same device. Through the actuation of PDMS-based pneumatic valves, sample from the hydrodynamic region can be injected into the electrophoresis portion of the microchip, where the analytes are separated based upon mass and charge. Post-separation derivatization using naphthalene-2,3-dicarboxaldehyde (NDA) and 2-β-mercaptoethanol (2ME) enables fluorescent detection of the catecholamines. Following optimization of the separation/detection portion of the device, off-chip cell stimulation experiments were performed to demonstrate the ability of this device to detect dopamine from a population of PC 12 cells. The final 3-dimensional device that integrates an immobilized PC 12 cell reactor with the bilayer continuous flow sampling/electrophoresis microchip was used to continuously monitor the on-chip stimulated release of dopamine from PC 12 cells. This approach allows the cells to be stimulated on-chip and, through rapid actuation of the PDMS-based valves, the products released from the cells are repeatedly injected into the electrophoresis portion of the microchip, where the analytes are separated and subsequently detected through post-column derivatization and fluorescence detection. While this paper is focused on PC 12 cells and neurotransmitter analysis, the final device is a general analytical tool that is amenable to immobilization of a variety of cell lines and analysis of various released analytes by electrophoretic means.

Experimental

Chemicals

The following chemicals and materials were used as received: Nano SU-8 50 (Microchem, Newton, MA, USA); AZ P4620 photoresist and AZ 400K developer (AZ Resist, Somerville, NJ, USA); aspartic acid (Acros, NJ); naphthalene-2,3-dicarboxaldehyde (NDA; Molecular Probes, Eugene, OR); 4-in. Si wafers (Silicon Inc., Boise, ID, USA); Sylgard 184 (Ellsworth Adhesives, Germantown, WI, USA). Where not otherwise noted, other reagents were from Sigma-Aldrich (St. Louis, MO).

Master Fabrication

The fabrication of the valve and flow channel masters were based upon previously published methods.17,18 Four mL of positive photoresist (AZ P4620) was coated onto a HMDS-coated silicon wafer at 700 rpm for 40 sec using a spin coater (Laurell Techonologies, North Wales, PA). The wafer was placed on a hot plate (Barnstead International, Dubuque, IA) at 110 °C for 3 mins. It was then allowed to cool prior to exposure with a UV flood source (Optical Associates Inc., Milpitas, CA) at 10 mW/cm2 for 50 sec through a positive film (The Negative Image, St. Louis, MO). After exposure, the wafer was developed in AZ 400K developer and post baked for 20 min at 120 °C. The depth of the PDMS channels, corresponding to the step height of the structures, was measured with a profilometer (Dektak3 ST, Veeco Instruments, Woodbury, NY). The rounded flow channels were typically 25 μm deep with the separation and pushback channels being 40 μm wide, while the hydrodynamic flow channel was 130 μm wide. Valve master fabrication consisted of spinning 4 mL of SU8-50 negative photoresist onto a 4-in silicon wafer at 1200 rpm for 40 sec. The photoresist was prebaked at 95 °C for 5 min prior to UV exposure at 10 mW/cm2 for 180 s. through a negative film. After exposure, the wafer was post baked at 95 °C for another 5 min and developed in 1-methoxy-2-propanol acetate (Fisher Scientific, Springfield, NJ). The valves were 90 μm in height and 240 μm wide.

Microchip Assembly

The assembly of the microchips were based on previously published methods.17 A 5:1 mixture of PDMS was poured into a mold formed on the master valve layer, which aided in the creation of a thick layer of PDMS. Meanwhile, a 20:1 mixture of Sylgard 184 elastomer and curing agent was spin coated (2000 rpm for 1 min) onto a flow channel master. The valve wafer was cured at 75 °C for 30 min, while the flow channel wafer cured at 75 °C for 15 min. Holes were then punched in the valve layer, which were approximately 3.5 mm thick, at the valve inlet with the 20 gauge luer stub adapter. This hole will later serve as the inlet for nitrogen gas and aid in the actuation of the valves. Alignment of the valve layer onto the flow layer was carried out under a stereomicroscope (SZ60, Olympus America, Melville, NY). The two layers were then cured together for 60 min at 75 °C to form one PDMS microchip. The cured PDMS layers were then peeled up from the thin layer master and a sample access hole was created through the layers using a 0.82 mm i.d. circular razor (Technical Innovations, Brazoria, TX), while a 3 mm i.d. circular razor (Technical Innovations, Brazoria, TX) was used to form the waste and buffer reservoirs. A 20:1 mixture of PDMS was poured onto single strength soda lime glass and fully cured in the oven for 60 min at 75 °C.

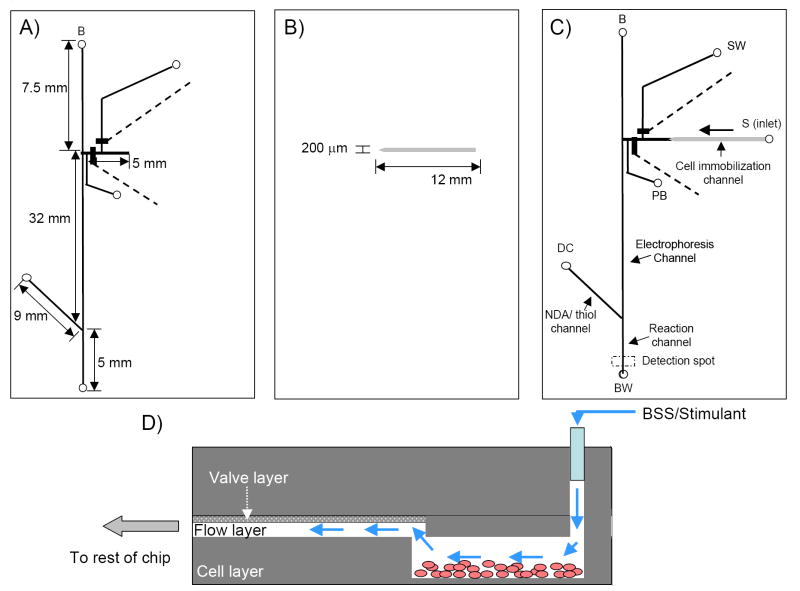

For characterization studies and off-chip PC 12 cell analysis, the microchip design depicted in Fig. 1 was utilized. The distance between the flow channel and pushback channel at the intersection was 50 μm. The final microchip shown in Fig. 1C was reversibly sealed to a PDMS-coated glass plate before use. For studies where PC 12 cell immobilization was integrated with continuous flow sampling and microchip electrophoresis with fluorescence detection, the bilayer microchips were fabricated as stated in the previous section but the hydrodynamic channel is shorter, with only a length of 5 mm (Fig. 2A). An additional PDMS layer, consisting of the cell channel is included in this assembly as well. This is a 12 mm in length straight channel (250 μm wide, 90 μm in height) that is rectangular in shape and made with SU8 negative resist (Fig. 2B). This takes place of the PDMS slab used in the characterization/off-chip PC 12 cell studies. One end of this cell channel is tapered down to approximately the same width as the hydrodynamic flow channel of the bilayer microchip of 130 μm. The wider area of the cell channel enables more cells to be immobilized in this region while the tapered region prevents leakage once the multilayer microchip is fully assembled. As shown in Figs. 2C and D, this leads to a 3-dimensional fluidic device, where the cell immobilization channel and the hydrodynamic flow channel of the bilayer microchip are in separate layers.

Fig. 1.

Bilayer device with post column derivatization channel. Dimensions of the flow and valve layers are shown in (A) and (B). Assembled chip is seen in (C) with close-up micrograph of the interface. Labels are as follows: B, buffer reservoir; BW, buffer waster; S, sample inlet; SW, sample waste; PB, pushback reservoir; DC, derivatization channel; NO, normally open; NC, normally closed.

Fig. 2.

Dimensions of the multilayer cell analysis device. Assembly of bilayer microchip (A) with rectangular cell culture channel (B) leads to a fully assembled multilayer cell analysis device (C). A side profile of the interface between the cell culture channel and the hydrodynamic portion of the bilayer microchip is illustrated in (D).

Microchip Operation

The PDMS-based pneumatic valves were dead end filled with water through the use of pressurized water vials that were connected to a solenoid valve (MAC Fluid Power Engineering, St. Louis, MO). The pressure of the gas was controlled by a regulator, while the solenoid valve was controlled by a power supply control unit (Instrument Design Lab, University of Kansas, Lawrence, KS). Once the valves were dead end filled, the control unit were used to actuate the valves for a specific period of time.

The microchips depicted in Figs. 1 and 2 were operated similarly. High voltage was applied to the buffer reservoir (B), a pushback voltage was applied to pushback reservoir (PB), and a ground was applied to buffer waste reservoir (BW). As described previously, the pushback voltages lead to a small amount of electroosmotic flow down the pushback channel to minimize sample carryover at the injection interface as well as leakage into the electrophoresis separation channel.17,18 Also, as described in results/discussion, a fraction of the high voltage was applied to the derivatization channel (DC) to eletroosmotically pump the derivatization solution to the separation channel. Sample solution (standards or stimulant solution) was continuously pumped (model 11 Plus syringe pump, Harvard Apparatus, Holliston, MA) through the sample inlet (S) to the hydrodynamic flow channel and out to sample waste hole (SW) while valve 1 was normally open and valve 2 was normally closed. In order to conduct an injection of sample, valve 2 would open for a specified amount of time (actuation time), while valve 1 was concurrently closed. Typical injection volumes for 600 and 800 ms actuation times are 555 and 790 pL, respectively.

A fluorescence microscope (IX71, Olympus America) with a 100 W Hg arc lamp, a semi-apochromat 10x Olympus microscope (0.30 numerical aperture), and a cooled 12-bit monochrome QICAM FAST digital CCD camera (QImaging, Montreal, Canada) was used for single-point fluorescence detection. A 400-440 nm band pass filter was used to isolate the excitation radiation while a 475 nm long pass was used to filter the emission (UIS2 Series, Olympus America). To generate electropherograms, images were captured at a frequency of at least 19 Hz using Streampix Digital Video Recording software (Norpix Inc, Montreal, Canada). This software allowed pixel integration over a user specified area (fixed to be 30 × 35 μm). This data was output to a Microsoft Excel file and the resulting data was processed using ChromPerfect software (Justice Laboratories, Denville, NJ).

PC 12 culture, immobilization and stimulation

Untreated T-25 culture flasks (Corning, Fisher Scientific) were coated with polygen, a solution of 60.0 μL of PureCol collagen solution (Inanmed, Fremont, CA), 4.5 mL of a 0.03 mg/mL poly-l-lysine solution, and 9.0 mL of 30% ethanol. The polygen was then left in the flasks overnight to evaporate, after which the flasks were rinsed with 10x phosphate buffered saline solution (Fisher Scientific, Springfield, NJ) and then replaced by F-12K medium (Kaighn’s modification of Ham’s F-12 medium; ATCC, Manassas, Virginia) supplemented with 10% penicillin-streptomycin solution, 5% fetal bovine serum (ATCC), and 10% horse serum (ATCC). A nerve growth factor (NGF; Roche, Switzerland) solution was also added to the cell media (final concentration = 100 ng/mL). The NGF allows the cells to elongate processes and form dendrites that we have found aid in immobilization of the cells within the channels.19 PC 12 cells (ATCC) were then transferred into the flask and placed into the incubator at 37°C, 7% CO2. Cell medium was replaced every 1-2 days and subcultured as needed (approximately 7 days).

For off-chip cell analysis studies, PC 12 cells were seeded into 35 mm petri dishes (Fisher Scientific, Springfield, NJ) and allowed to grow for ~5 days until 90% confluency prior to analysis. Media was removed from the cells preceding analysis and rinsed twice with buffered saline solution (BSS)20 to ensure full removal of media from the cells. Cells were then exposed to a K+/Ca2+stimulant solution. This solution was then directly pumped into the bilayer microfluidic device for analysis. The stimulant solution is comprised of 80 mM KCl, 150 mM NaCl, 0.7 mM MgCl2, 2 mM CaCl2, and 1 mM NaH2PO4, and 10 mM HEPES.20 Cells were counted after stimulation with a hemocytometer. Dopamine standards were prepared daily and analyzed on the same microchip.

For on-chip PC 12 cell analysis with the integrated cell reactor microchips, cells were immobilized in the PDMS channels.14 To coat the channels with polygen, the cell channels were reversibly sealed to a glass plate with 1 mm holes at each end for fluid access. The ends of the PDMS channels were aligned to these access holes. A polygen solution was placed into one of the access holes and aspirated through the channels with vacuum. The polygen solution was then allowed to evaporate in the channels overnight, after which time the channels were rinsed with a solution of BSS. The trough method14 was used to immobilize the cells into the polygen coated channels. Here, another piece of PDMS with a 1 cm × 0.2 cm slit removed is reversibly sealed over the polygen coated channel (facing up). This creates an area where the polygen-coated channel is accessible to cells. A solution of cells are then pipetted into trough and placed into the incubator for at least 24 hours. As we showed previously, the PC 12 cells immobilize only on the coated portion of the microchannels.14

Once the cells have resided in the channels for at least 24 hours, they can be used for analysis. To assemble the multilayer cell analysis microchip device, the excess media in the trough can be simply removed with a Kimwipe®. The PDMS trough layer can be removed and, with the cell channel facing up, the end of the hydrodynamic flow channel of the bilayer chip is aligned to the tapered end of the cell region. This multilayer microchip device can be seen in Fig. 2.

A 4-port injection valve containing a 500 nL internal rotor was used to introduce a plug of stimulant to the cell channel for the on-chip cell analysis experiments. BSS is continuously delivered from a 500 μL syringe (Hamilton, Reno, NV) by a syringe pump (model 11 Plus Harvard Apparatus, Holliston, MA) through the 4-port injection valve (Valco Instruments Co. Inc.) at a flow rate of 0.9 μL/min to the multilayer device. Meanwhile, another syringe with the stimulant solution is introduced into the injection valve. By switching from the load to inject position, a plug of stimulant solution is directed towards the chip. To minimize the dead volume of transferring stimulant solution to the microchip, the syringe delivered BSS solution to the multilayer microchip via an 8.25 cm in length fused silica capillary (360 μm o.d. × 75 μm i.d. Polymicro Technologies, Phoenix, AZ) adapted with a microtight tubing sleeve (395 μm i.d and.790 μm o.d., Upchurch Scientific, Oak Harbor, WA). This capillary was inserted into a 0.65 mm o.d. connecting tube (BAS, West Lafayette, IN) and coupled to a 17.2 cm section of Teflon tubing (0.65 mm o.d. × 0.12 mm i.d.; BAS), with the Teflon tubing being made flush against the capillary tubing. Taking into account the dead volume of the capillary and Teflon tubing (2.31 μL) as well as the dead volume of the sample inlet hole (0.167 μL), the total dead volume of the system outside of the microchip is 2.48 μL; however, this volume does not affect any on-chip processes such as the release of neurotransmitters from PC 12 cells. Dopamine standards were prepared daily and analyzed on the same microchip.

Results and discussion

Post-column derivatization for fluorescence detection

Our earlier work reporting the development of a reversibly-sealed bilayer microchip with integrated pneumatic valves used fluorescence detection without any means of labeling analytes on-chip.17 To study the release of neurotransmitters from a neuronal cell model, we chose to exploit the fact that catecholamines can derivatized to be fluorescent through reaction of their primary amine moiety with naphthalene-2,3-dicarboxaldehyde (NDA) and 2-β-mercaptoethanol (2ME).21,22 Pre-, on-, and post-column sample derivatization approaches have been reported for microchip devices23-26 where the sample is combined with a derivatization reagent stream prior to (pre-column), during (on-column), or after (post-column) the separation.22,27 Post-column derivatization for microchip electrophoresis has several advantages. Analyte dilution is minimal and the formation of side reaction products is avoided.22 In addition, the analytes are first separated based upon their native electrophoretic mobilities prior to derivatization and detection. This enables the separation of analytes that are very similar in structure. The use of NDA/2ME for post-column derivatization and fluorescence detection of amino acids, neuropeptides and proteins at high nanomolar concentrations following separation by CE was first demonstrated by Gilman and Ewing in 1994.28 Later, Lunte’s group used the same reagents for detecting peptides using CE with laser-induced fluorescence detection.29 Although NDA/2ME derivatives are unstable for use in pre-column derivatization schemes, their formation rate, fluorescence yield and stability are suitable to be used as a post-column derivatization reagent.28

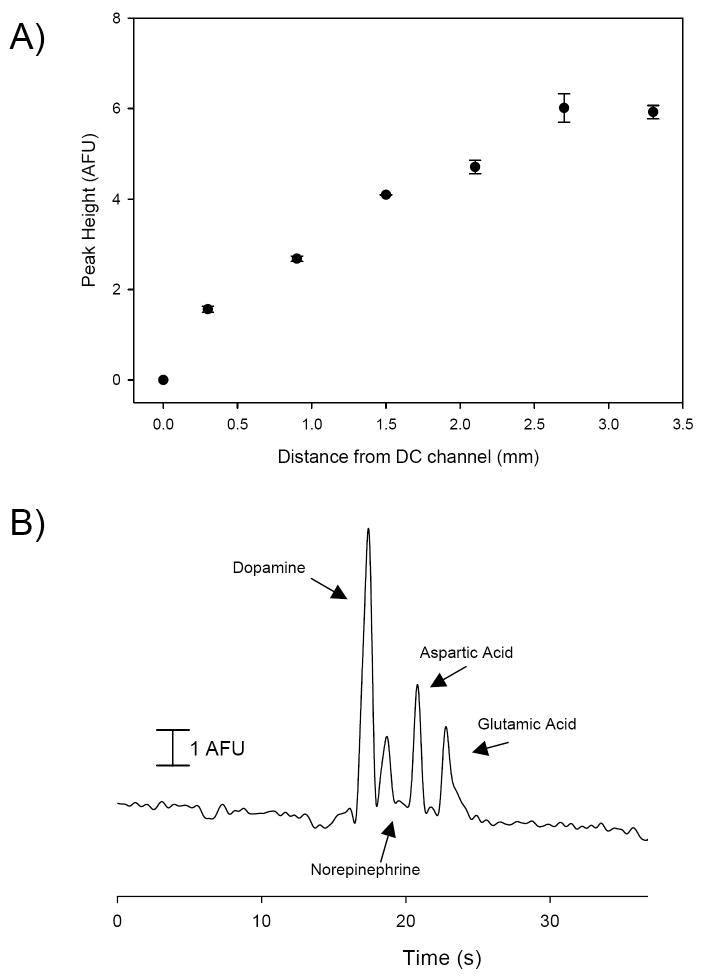

To enable post-column derivatization, these studies includes an extra channel denoted the derivatization channel (DC) that feeds into the electrophoresis channel approximately 5 mm from the detection spot. The reservoir for this channel is filled with a solution of NDA/2ME (1.8 mM NDA and 3.6 mM 2ME, diluted with the separation buffer). A fraction of the separation voltage is applied to the reservoir (455 V), resulting in a junction voltage30 at the separation/derivation channel intersection of 244 V. This voltage allows the NDA/2ME mixture to be continuously pumped in to the electrophoresis separation channel. In order to determine optimal placement of the detector spot for fluorescence detection, alignment markers were placed prior to the DC junction and at periodic locations past the junction. These alignment markers served as guides for placement of the detection spot for fluorescence detection. In microfluidic channels, there is always concern about proper mixing due to low Reynold’s numbers. The electroosmotic flow of these buffers leads to a Reynold’s number of <0.01 in the separation channel meaning that there is only diffusion-based mixing of the separated analyte band with the derivatization reagents. To determine the optimal location for the detection spot in the separation channel, a 1.1 mM dopamine solution was continuously pumped through the hydrodynamic flow channel and repeatedly injected (800 ms valve actuation) into the separation channel. Electrophoresis carried the plug down the separation channel to the derivatization reagents. Fluorescence was monitored as a function of time at each of the detection spots as well prior to the DC junction. It can be seen in Fig. 3A that there is near linear increase in the fluorescence intensity (peak height) of the derivatized dopamine peak. Past the 2.7 mm marker, the response begins to plateau and, due to the short-lifetime of the derivatized product,31 begins to decrease after 3.3 mm (data not shown in plot). To ensure maximal mixing/reaction time and minimal degradation of the analytical signal,28,29 we held the detection spot at the 3.3 mm alignment marker for subsequent use. Figure 3B demonstrates the ability of our device to inject, separate, derivatize and detect multiple analytes including dopamine, norepinephrine, aspartic acid, and glutamic acid.

Fig. 3.

A) Fluorescent intensity as a function of the distance down the derivatization channel. Dopamine was injected into the microchip device (800 ms actuation) and monitored at varying detection spots along the electrophoresis channel after the post column derivatization channel junction. 25 mM boric acid/ 3 mM SDS buffer, pH 9.5. High voltage = 1500 V, Pushback voltage = 500 V, post column voltage = 400 V, and flow rate = 0.7 μL/min. Error bars shown as standard error of the mean (n = 3). B) Multianalyte separation of 1.1 mM dopamine, 1.1 mM norepinephrine, 1.4 mM aspartic acid, and 2.3 mM glutamic acid.

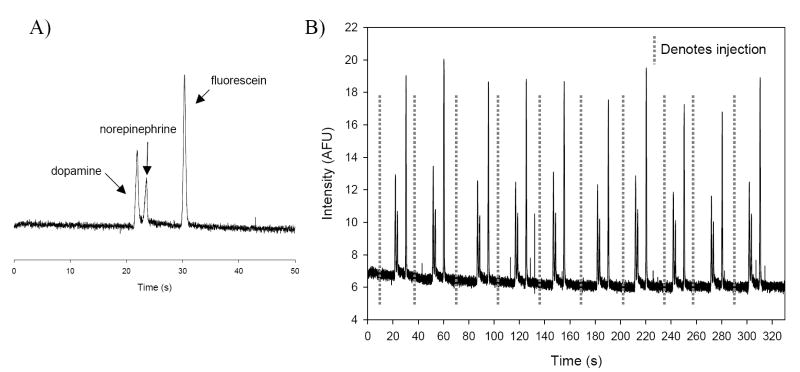

The bilayer device was also proficient at reproducibly injecting, separating, derivatizing, and detecting our analytes of interest, dopamine and norepinephrine. Figure 4A shows a separation from one injection of dopamine, norepinephrine, and fluorescein. Figure 4B shows an electropherogram that results from 10 sequential injection of this mixture into the separation channel. The actuation time was 600 ms and injections were made every 30 sec. Following separation and derivatization, the average peak heights were found to be: 6.26 ± 0.41 AFU (6.5% RSD) for dopamine, 3.99 ± 0.20 (5.0% RSD) for norepinephrine, and 12.4 ± 0.92 (7.4% RSD) for fluorescein. Injection, separation, derivatization and detection of various concentrations (100 μM to 1.5 mM) of dopamine led to a linear response (r2 of 0.9987) and a limit of detection (LOD) of 70 μM. Similar experiments using norepinephrine (concentrations of 250 μM to 2.5 mM) also showed a linear correlation (r2 of 0.9915) and a LOD of 250 μM. The relatively high detection limits is due to the fact that these experiments were carried out with a fluorescence microscope using a 100 W Hg arc lamp for the excitation source. If desired, the LOD could be improved upon through the usage of a HeCd laser for the excitation source.32 This is due to the fact that the power of fluorescence emission is proportional to the radiant power of the excitation beam and lasers have more power than arc lamps.33 The integration of amperometric detection with the relative complex bilayer devices used here is an on-going research effort but we have shown previously that the use of microchip electrophoresis with a palladium decoupler and carbon ink microelectrodes enables an LOD of 900 nM for dopamine.34 However, for these studies we found that the fluorescence microscope system is easy to use and, since it is commercially available, makes routine fluorescence detection possible for non-laser experts. As is detailed below, the ability to integrate cell culture with on-chip analysis minimizes sample dilution so that these detection limits are sufficient to monitor the release of dopamine from a layer of PC 12 cells.

Fig. 4.

A) Electropherogram demonstrating the valving-based injection, electrophoretic separation, post-column derivatization and fluorescent detection of 1.1 mM dopamine, 2.25 mM norepinephrine, and 5 μM fluorescein. B) Sequential injections (n = 10) of the sample in (A).

Off-chip stimulation of PC 12 cells

After optimizing the post-column derivatization and fluorescence detection schemes for the bilayer microchip device, we next sought to determine whether or not this device is capable of detecting the products released from PC 12 cells upon stimulation. To provide a comparison to subsequent on-chip stimulation studies, we first performed our measurements on PC 12 cells that had been stimulated off-chip. Initially, the PC 12 cells were grown to 90% confluency in 35 mm petri dishes over a period of 5 days (Fig. 5A). The cells were then rinsed with a BSS twice prior to exposing them to 600 μL of a K+/Ca2+stimulant solution for approximately 1 min. The stimulant solution was then withdrawn from the petri dish of cells with a 250 μL syringe and directly pumped into the bilayer microchip device. The PDMS-based valves were used to periodically inject this sample and the injected plug was electrophoretically separated, derivatized, and detected with fluorescence. As shown in Fig. 5B, from a petri dish of approximately 2.6 × 105 cells, dopamine was detected at an average concentration 320 μM. To verify that the product released was dopamine, 200 μL of the stimulant solution (same solution that was exposed to the cells) was spiked with dopamine standard (final spiked concentration = 955 μM). The resulting electropherograms from these experiments can be seen in Fig. 5B, where the spiked and cell release data are overlaid. The migration times of the 2 samples correlate, validating that the cell release product is dopamine. Blanks were also performed where the PC 12 cells were exposed to BSS. Continuous injection of this solution resulted in no signal (data not shown). From these results it can be determined that approximately 7.5 × 10-13 mol of dopamine are released per cell. Norepinephrine was not detected for several reasons. PC 12 cells are known to release dopamine and norepinephrine in differing amounts, with the initial PC 12 study showing a 10:1 dopamine:norepinephrine ratio.19 Subsequent studies have shown this ratio can be as high as 20:1.35 Due to the LOD of norepinephrine with the current detection method (discussed in previous section), we are unable to detect the best-case (assuming a 10:1 ratio) theoretical amount of ~30 μM norepinephrine released from the cells.

Fig. 5.

A) Micrograph showing PC 12 cells at 90% confluency in 35 mm petri dishes that were used for off-chip analysis. B) Electropherogram resulting from injection, separation, and post-column derivatization of off-chip stimulation solution. Dopamine release from the stimulated PC 12 cells is shown in comparison to the injection of the same solution spiked with of 955 μM dopamine standard.

Monitoring release from PC 12 cells cultured on-chip

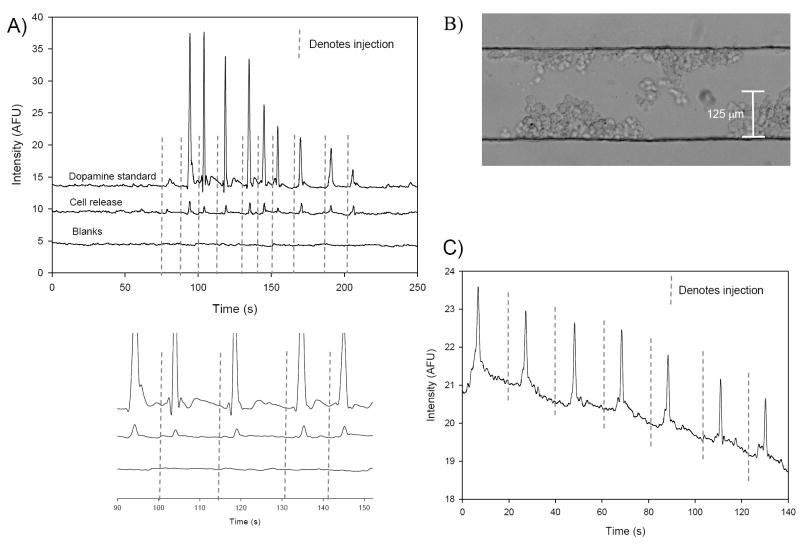

Initial studies of immobilizing the cells directly in the shallow, rounded flow channels of the bilayer device were unsuccessful. In previous work from our lab, we found that cells immobilized in rectangular-shaped PDMS channels (100 × 100 μm cross-section) maintained viability for up to 5 days and could be subjected to flow rates as high as 3.5 μL/min.14 Furthermore, we noted that the cells preferred to immobilize in the corners of the rectangular microchannel. To integrate the immobilization of PC 12 cells with continuous flow sampling, electrophoresis, derivatization, and detection, the multilayer microchip device seen in Fig. 2 was employed. In this device, the cells are immobilized in a separate layer that contains rectangular channels as in the previous study. As compared to the device in Fig. 1, the bilayer device has a shorter hydrodynamic flow region of 5 mm as seen in Fig. 2A. The cell immobilization layer (Fig. 2B) has a rectangular channel made from SU8 photoresist (250 μm wide × 90 μm in height × 12 mm in length). The channel is tapered to a width of 130 μm and when analysis of the immobilized cells is desired, this section of the channel is reversibly sealed with the open side of the bilayer device, creating a 3-dimensional microfluidic device (Fig. 2C). A side profile of the interface between the bilayer device and the cell channel can be seen in Fig. 2D. Buffer/stimulant introduced into the microchip device first enters through the bilayer portion of the microchip into the cell immobilization channel until it is transferred to the flow layer of the bilayer device.

We have previously shown that the dead volume from tubing and syringe connectors limits the temporal resolution of monitoring off-chip changes in concentration to 120 sec.17 This value is probably a best-case scenario, as we used very short pieces of tubing and solutions were directly introduced into the chip so that dead volumes from off-chip sampling mechanisms were not considered. The ability to culture cells on-chip along with the use of fabricated microchannels and PDMS-based valves to integrate the cultured cells to the electrophoresis portion of the device greatly minimizes dilution and improves the temporal resolution of the device. Taking into account the channel volumes, flow rates and experimental data, it was determined that it takes ~16 sec. for stimulant solution to travel from the inlet of the device to the injection interface and ~14 sec. for injected sample to migrate to the detection spot. The resulting ~30 sec. temporal resolution is a product of both the minimal dilution and fast analysis times.

In order to monitor the products released upon stimulation of the immobilized cells, we utilized an off-chip 4-port injection valve to introduce a plug of stimulant solution to the cells. Figure 6A shows the release from one device where the cells are stimulated and the cellular release is continually sampled and analyzed over a period of time by continuously injecting, separating, derivatizing, and detecting dopamine. For comparative purposes, this plot also shows the electropherograms for multiple injections of a 2.12 mM dopamine standard and BSS blanks (where BSS is pumped over the cells). As shown in the zoomed portion of Fig. 6A, the migration times between the standard and the cell release correspond verifying the cell release as dopamine. Norepinephrine was not detected due to the same reasons stated in the previous section. Figure 6B shows a population of ~507 cells that have been immobilized in the cell culture channel for 1 day. Fig. 6C shows the data from exposing these particular cells to stimulant solution. The electropherogram shows multiple injections of the cellular release solution into the electrophoresis portion of the device. Comparing the average response to the response from injecting dopamine standards it was determined that on average this population of cells released 242 μM dopamine. By taking into account the volume of the cell immobilization channel for dilution purposes (230 nL), this amounted to ~1.1 × 10-13 moles of dopamine released per cell. This is an approximate number, as there is some error with counting cells in the channel and there may be less dilution than is assumed by using the entire volume of the cell immobilization channel. Nevertheless, with both on- and off-chip cell analyses, we were able to detect ~10-13 moles of dopamine released per cell. Comparing these results to the off-chip cell studies, the on-chip cell analysis resulted in a similar concentration of dopamine being released from a population of cells almost 500 times smaller than what was used in the off-chip cell analysis. This is primarily due to the minimal sample dilution experienced with on-chip analyses and the larger volumes needed to carry out the off-chip experiments. The ability to minimize both dilution and the time between stimulation and analysis is important for studies where the released product is short-lived and/or low in concentration.

Fig. 6.

A) Electropherograms demonstrating the on-chip stimulation of PC 12 cells, followed by valving-based injection of the cellular release, electrophoretic separation, post-column derivatization and fluorescent detection of the resultant derivatized dopamine. The plots also compare multiple injections of a 2.12 mM dopamine standard to multiple injections of the stimulant solution. Also shown in the plot is the response from injecting plugs of BSS over the cells. An enlarged portion of the electropherogram zooms in on the first 5 injections demonstrating the correlation of migration times between the standards and the actual cell release. B) Micrograph of PC 12 cells immobilized within one portion of the multilayer device with BSS pumping over the immobilized layer at 0.9 μL/min. C) Electropherogram of the release (242 μM dopamine) seen from PC 12 cells immobilized in the multilayer device where ~507 cells are immobilized in the cell culture channel.

Conclusions

These studies have shown that it is possible to integrate the culture and immobilization of a PC 12 cell line with electrophoresis-based separations using continuous flow over the cells and PDMS-based valves to couple this continuous flow to electrophoresis. To enable detection of catecholamines released from these cells, a post-column derivatization scheme was included and optimized in terms mixing/reaction time. Off-chip PC 12 cell stimulation verified the ability of our system to monitor the stimulated release of dopamine. A multilayer, 3-dimensional microchip device was used to integrate cell immobilization on-chip. It was shown that integration of the immobilized cells with the analysis portion of the device minimized dilution and improved the temporal resolution of the system. Similar dopamine release was seen when stimulating on-chip versus off-chip yet the on-chip immobilization studies could be carried out with 500 times fewer cells in a much reduced volume (230 nL vs. 600 μL). To our knowledge, this is the first report of a fully integrated microchip device that couples cell immobilization and hydrodynamic flow over the cells to microchip electrophoresis with an integrated detection scheme. While this paper is focused on PC 12 cells and neurotransmitter analysis, the device we developed could be used as a general analytical tool that is amenable to immobilization of a variety of cell lines and analysis of various released analytes by electrophoretic means. Future work will involve increasing the sensitivity of the device, integrating the discrete injection of stimulant on-chip, and incorporating another cell line (such as microglia) to investigate how the multiple cell types interact.

Acknowledgments

This research was supported by a grant from the National Institutes of Health (R15 NS048103).

References

- 1.El-Ali J, Sorger PK, Jensen KF. Nature. 2006;442:403–411. doi: 10.1038/nature05063. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Martin RS, Root PD, Spence DM. Analyst. 2006;131:1197–1206. doi: 10.1039/b611041j. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Price A, Culbertson CT. Anal Chem. 2007;79:2614–2621. doi: 10.1021/ac071891x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Sims CE, Allbritton NL. Lab Chip. 2007;7:423–440. doi: 10.1039/b615235j. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Gomez-Sjoberg R, Leyrat AA, Pirone DM, Chen CS, Quake SR. Anal Chem. 2007;79:8557–8563. doi: 10.1021/ac071311w. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Moehlenbrock MJ, Martin RS. Lab Chip. 2007;7:1589–1596. doi: 10.1039/b707410g. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Wheeler AR, Throndset WR, Whelan RJ, Leach AM, Zare RN, Liao YH, KFarrell K, Manger ID, Daridon A. Anal Chem. 2003;75:3581–3586. doi: 10.1021/ac0340758. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Huang B, Wu H, Bhaya D, Grossman A, Granier S, Kobilka BK, Zare RN. Science. 2007;315:81–84. doi: 10.1126/science.1133992. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Wu H, Wheeler A, Zare RN. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2004;101:12809–12813. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0405299101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Salazar GT, Wang Y, Young G, Bachman M, Sims CE, Li GP, Allbritton NL. Anal Chem. 2007:682–687. doi: 10.1021/ac0615706. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Genes LI, Tolan NV, Hulvey MK, Martin RS, Spence DM. Lab Chip. 2007;7:1256–1259. doi: 10.1039/b712619k. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Spence DM, Torrence NJ, Kovarik ML, Martin RS. Analyst. 2004;129:995–1000. doi: 10.1039/b410547h. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Oblak TD, Root P, Spence DM. Anal Chem. 2006;78:3193–3197. doi: 10.1021/ac052066o. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Li MW, Spence DM, Martin RS. Electroanalysis. 2005;17:1171–1180. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Sombers L, Ewing AG. In: Electroanalytical Methods for Biological Materials. Brajter-Toth A, Chambers JQ, editors. Marcel Dekker; New York: 2002. pp. 279–327. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Michael DJ, Wightman RM. J Pharm Biomed Anal. 1999;19:33–46. doi: 10.1016/s0731-7085(98)00145-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Li M, Martin R. Electrophoresis. 2007;28:2478–2488. doi: 10.1002/elps.200600713. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Li MW, Huynh BH, Hulvey MK, Lunte SM, Martin RS. Anal Chem. 2006;78:1042–1051. doi: 10.1021/ac051592c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Greene LA, Fainelli SE, Cunningham ME, Park DS. In: Culturing Nerve Cells. Banker G, Goslin K, editors. MIT Press; Cambridge: 1998. pp. 161–188. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kozminski KD, Gutman DA, Davila V, Sulzer D, Ewing AG. Anal Chem. 1998;70:3123–3130. doi: 10.1021/ac980129f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Dave KJ, Stobaugh JF, Rossi TM, Riley CM. J Pharm Biomed Anal. 1992;10:965–977. doi: 10.1016/0731-7085(91)80106-j. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Pasas SA, Fogatry BA, Huynh BH, Lacher NA, Carlson B, Martin RS, Vandaveer WR, Lunte SM. In: Separation Methods in Microanalytical Systems. Kutter JP, Fintschenko Y, editors. CRC Talyor and Francis; Boca Raton: 2006. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Jacobson SC, Koutny LB, Hergenroder RM, Moore AW, Ramsey JM. Anal Chem. 1994;66:3472–3476. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Liu YJ, Foote RS, Jacobson SC, Ramsey RS, Ramsey JM. Anal Chem. 2000;72:4608–4613. doi: 10.1021/ac000625f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Wang J, Chatrathi MP, Tian B. Anal Chem. 2000;72:5774–5778. doi: 10.1021/ac0006371. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Huynh BH, Fogatry BA, Nandi P, Lunte SM. J Pharm Biomed Anal. 2006;42:529–534. doi: 10.1016/j.jpba.2006.05.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Bardelmeijer HA, Waterval JCM, Lingeman H, van’t Hof R, Bult A, Underberg WJM. Electrophoresis. 1997;18:2214–2227. doi: 10.1002/elps.1150181212. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Gilman SD, Pietron JJ, Ewing AG. J Microcolumn Sep. 1994;6:373–384. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Kostel KL, Lunte SM. J Chromatogr B. 1997;695:27–38. doi: 10.1016/s0378-4347(97)00173-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Seiler K, Fan ZHH, Fluri K, Harrison DJ. Anal Chem. 1994;66:3485–3491. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Manica DP, Lapos JA, Jones D, Ewing AG. Anal Biochem. 2003;322:68–78. doi: 10.1016/j.ab.2003.07.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Toulas C, Hernandez L. LC GC. 1992;10:471–476. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Skoog DA, Holler FJ, Nieman TA. Principles of Instrumental Analysis. 6. Brooks/Cole; 1998. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Mecker LC, Martin RS. Electrophoresis. 2006;27:5032–5042. doi: 10.1002/elps.200600401. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Gilman SD, Ewing AG. Anal Chem. 1995;67:58–64. doi: 10.1021/ac00097a010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]