Summary

Ca2+ as a messenger of signal transduction regulates numerous target molecules via Ca2+-induced conformational changes. Investigation into the determinants for Ca2+-induced conformational change is often impeded by cooperativity between multiple metal binding sites or protein oligomerization in naturally occurring proteins. To dissect the relative contributions of key determinants for Ca2+-dependent conformational changes, here we report the design of a single-site Ca2+-binding protein (CD2.trigger) created by altering charged residues at an electrostatically-sensitive location on the surface of the host protein rat Cluster of Differentiation 2 (CD2). CD2.trigger binds to Tb3+ and Ca2+ with dissociation constants of 0.3 ± 0.1 and 90 ± 25 μM, respectively. This protein is largely unfolded in the absence of metal ions at physiological pH while Tb3+ or Ca2+ binding results in folding of the native-like conformation. Neutralizing the charged coordination residues either by mutation or protonation similarly induces folding of the protein. The control of a major conformational change by a single Ca2+ ion, achieved on a protein designed without reliance on sequence similarity to known Ca2+-dependent proteins and coupled metal binding sites, represents an important step in the design of trigger proteins.

Introduction

Ca2+-dependent conformational change is a common mechanism for signal transduction, which regulates trigger proteins' interactions with downstream partners and target molecules [1-6]. The trigger proteins can respond to Ca2+ concentration changes in different cellular environments through cooperative binding/dissociation of multiple Ca2+ ions [3]. For example, upon binding four Ca2+ ions, calmodulin (CaM) exhibits a large rearrangement of the flexible Ca2+ binding loops and the helical packing of paired EF-hand motifs, which affords CaM the ability to regulate more than 100 target proteins in various biological processes [4-6]. Conversely, Troponin C, with a strong sequence and structural similarity to CaM specifically interacts with troponin I to control muscle contraction. Extracellularly, Ca2+-sensing receptors and other sensing proteins each bind to several Ca2+ ions cooperatively to activate multiple signaling pathways in the cytosol through conformational changes.

Electrostatic interactions have been proposed to be important for Ca2+-induced conformational change as well as for Ca2+ binding affinity and protein stability [7-9]. Statistical analyses have shown that Ca2+ ions are predominantly coordinated to oxygen from carboxylate, carbonyl, and hydroxyl groups in proteins [10-12]. A Ca2+ binding site in proteins has an average coordination number of 6-7, arranged in either a pentagonal bipyramidal or distorted octahedral geometry. Proteins that exhibit large Ca2+-induced conformational changes usually have a high number of charged residues in the Ca2+ binding sites. While the clustering of negatively charged residues favors the attraction of positively charged Ca2+ ions, it may also force a conformational rearrangement of the coordination residues or even the entire protein in the absence of Ca2+. Additionally, structural studies have revealed large ensembles of conformations of trigger proteins in different states. However, the determinants for Ca2+ binding and Ca2+-dependent conformational changes are yet to be clearly elucidated. To date, development of novel Ca2+-dependent proteins is based on mimicking the natural Ca2+ binding proteins with multiple coupled metal binding sites [13]. Chazin's group reported their elegant work on creating the CaM-like Ca2+-dependent conformational change in calbindin D9k by replacing residues in calbindin D9k with the corresponding residues of CaM [14]. However, it is not clear whether it is possible to achieve calcium-dependent conformational change without using coupled metal binding sites.

A major barrier to understanding the molecular mechanism of Ca2+-dependent biological functions is the lack of established rules relating Ca2+-binding affinity to specific structural aspects of proteins [15, 16]. This is exacerbated by the complexities encountered in cooperative, multi-site systems, and the use of Ca2+-binding energy to effect conformational changes in proteins such as calmodulin [17]. Obtaining information for calcium-induced conformational change is limited by the measurement of Ca2+-binding affinities for site-specific Ca2+ binding and cooperativity [15].

To overcome the limitations associated with naturally-occurring Ca2+-binding proteins, our lab has developed an approach to dissect the key structural factors that control Ca2+-binding affinity, Ca2+-dependent conformational changes, and cooperativity by designing a single Ca2+-binding site in a model protein [13, 14]. Departing from previously published studies that mimic natural Ca2+ binding proteins [18-20], we have demonstrated the successful design of an array of single Ca2+-binding sites using the host protein rat Cluster of Differentiation 2 (CD2). For example, the single Ca2+-binding site in Ca.CD2 was shown to be capable of resisting global conformational changes upon Ca2+ binding and solution structures demonstrated that Ca2+ bound at the intended site with the designed arrangements [19, 21, 22]. This model system was used to dissect local factors important for calcium binding affinity [20, 21, 23].

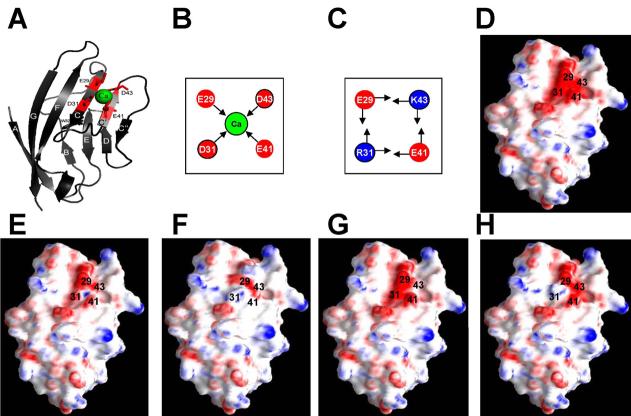

In this paper, we report the successful design of a trigger protein (CD2.trigger) that can be used as a model system to reveal key factors essential for Ca2+-dependent conformational changes. CD2 has a common immunoglobulin fold with nine β-strands sandwiched in two layers (Fig. 1A) [24, 25], which is similar to that of the Ca2+-dependent molecules cadherin and C2 domains [26]. Results from a designed Ca2+-binding CD2 can directly aid in the study of these proteins. In addition, CD2 can be reversibly refolded [27], which is important for the study of Ca2+-dependent conformational change and Ca2+-dependent biological function. Unlike our previously-designed Ca2+-binding proteins, the design of CD2.trigger is created by altering charged residues at an electrostatically sensitive location based on the hypothesis that Ca2+-dependent protein folding can be achieved by Ca2+ binding to reduce the electrostatic repulsion in the apo protein. Two positively charged residues Arg-31 and Lys-43 that form a network of salt bridges with Glu-29 and Glu-41 were mutated to acidic residues to form a Ca2+-binding pocket. In contrast to conformational changes elicited by cooperative binding of multiple Ca2+ ions to natural proteins, the designed CD2.trigger exhibits a major conformational change upon binding of a single Ca2+ ion revealed by various spectroscopic methods.

Fig. 1.

Protein design and calculation. (A) Model structure of designed Ca2+-binding protein CD2.trigger with Ca2+-coordination residues Glu-29, Asp-31, Glu-41 and Asp-43 based on CD2 (1hng). This structure was drawn using the program PyMOL (DeLano Scientific LLC). (B) Local electrostatic interactions in CD2.trigger and in wild-type CD2 (C). (D-H) Surface electrostatic potential of metal-free CD2.trigger, Ca2+-loaded CD2.trigger, wild-type CD2, metal-free R31D/K43N, and metal-free R31K/K43D, respectively.

Results

Design of a Ca2+-modulating protein

The design of a Ca2+-binding protein with Ca2+-induced global conformational change was based on several considerations. First, since natural Ca2+ trigger proteins often have Ca2+-induced folding instead of Ca2+-induced unfolding, we assumed that the Ca2+-bound protein possesses wild-type CD2 structure. Therefore, we performed computational design of the Ca2+-binding site based on the local geometric properties of a target site in the host protein by assuming that the backbone of the protein was not altered [18-20]. Second, to ensure the strong Ca2+-binding energy required for protein folding, it was determined that a minimum of four negatively charged coordination residues should be utilized, based on results observed from our previous designs of Ca2+-binding proteins which indicated no global conformational changes following the introduction of 2-3 negatively charged coordination residues [20, 21, 23]. Third, regions on the protein surface with high electrostatic potentials (electrostatic “hot spots”) are typically sensitive to changes of electrostatic interactions upon binding of metal ions. Therefore, we hypothesized if repulsion of the cation-coordination residues leads to the unfolding of the apo protein, neutralization of these charges by Ca2+ binding may trigger the refolding of the protein.

Fig. 1A shows the model structure of the designed protein, denoted as CD2.trigger, with a Ca2+-binding site introduced into an electrostatic “hot spot” on CD2. The coordination shell of the site contains four negatively charged residues located at the center of the densely-charged GFCC'C” surface of the CD2 sandwich layers. The site was formed by two reverse charge mutations R31D and K43D together with the existing residues Glu-29 and Glu-41 (Fig. 1A and B). The mutations disrupt the charge balance at the site and the surrounding salt-bridge networks. In wild-type CD2, Arg-31, Lys-43, Glu-29, and Glu-41 form several salt bridges (Fig. 1C). In addition, they are involved in salt bridges with surrounding charged residues. A strong negative surface electrostatic potential is produced by the purported Ca2+-coordination residues and the surrounding negative residues such as Asp-28 and Glu-33, as calculated by the DelPhi program [28].

Metal binding affinity and selectivity

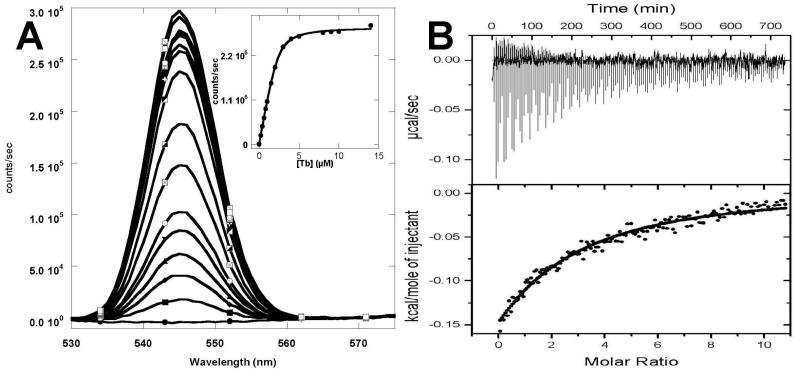

Supplementary Fig. 1 shows the ESI mass spectra of CD2.trigger variants. The addition of excess Ca2+ or La3+ resulted in the appearance of a new mass peak corresponding to CD2.trigger-metal complex with a stoichiometry of 1:1. By monitoring the NMR chemical shift changes as a function of Ca2+ concentration, a Kd value of 90 ± 25 μM was obtained. This is comparable to a Kd of 240 ± 20 μM obtained from isothermal titration calorimetry (ITC) (Fig. 2B). ITC study further revealed that Ca2+ binding of CD2.trigger was a slightly exothermic process. The small magnitude of heat release observed is very similar to the compensation of enthalpy change by endothermic Ca2+–induced conformational change observed for the trigger protein CaM [29] as well as the Zn2+-induced fold of zinc fingers [30]. However, it is quite different from the binding process observed on non-trigger protein α-lactalbumin. Unfortunately, the small change in the isotherm prevents us from obtaining the stoichiometry. The calculated ΔH and ΔS values for Ca2+ binding to CD2.trigger were −0.93 ± 0.02 kcal mol−1 and 11.6 ± 0.02 cal mol−1K−1, respectively. This ΔH value is several-fold smaller in magnitude than that of Ca2+ binding to α-lactalbumin with reported values of −1.7 kcal mol−1 at 5°C and −59 kcal mol−1 at 45°C in Tris-HCl buffer at pH 8.0 [31]. The formation of precipitation limits further ITC study of Tb3+ binding to CD2.trigger variants.

Fig. 2.

Metal binding affinities. (A) Fluorescence emission spectra of CD2.trigger (excited at 280 nm) in 10 mM PIPES/10 mM KCl pH 6.8 with 0, 0.2, 0.4, 0.6, 0.8, 1.0, 1.5, 2.0, 3.0 , 4.0, 5.0, 6.0, 7.0, 8.0, 9.0, 10, or 14 μM of Tb3+ (bottom to top). The fluorescence enhancement at 545 nm as a function of Tb3+ concentration was fitted assuming the formation of 1:1 protein-Tb3+ complex (inset). (B) Ca2+ titration of CD2.trigger by ITC at 5°C. A solution of 5 mM CaCl2 was titrated in increments of 2 μL into 0.1 mM protein.

Tb3+ binding to CD2.trigger resulted in a large fluorescence enhancement at 545 nm due to fluorescence resonance energy transfer (FRET) when excited at 280 nm (Fig. 2A). The R31K/K43D variant showed a significant decrease in Tb3+-binding affinity with an apparent Kd of 5.7 ± 0.6 μM obtained using FRET, while R31D/K43N had a Kd of 0.22 ± 0.04 μM similar to CD2.trigger (Supplementary Fig. 4). These binding affinities were considered the lower limits due to limitations of the direct titration method such as the concentration increment and accuracy, signal/noise ratio, and other factors. Our methods cannot measure any apparent Kd values smaller than 1 μM accurately. A decrease in metal binding affinity by the R31K/K43D mutation was expected since the mutations reduced the net negative charge at the metal-binding site. Such an affinity decrease was predicted by our electrostatic calculations on Ca2+ binding. The metal-binding affinities, using different methods, are summarized in Table 1.

Table 1.

Metal-binding affinity and thermal stability of the designed proteins

| Kd (μM) | Tm (°C)d | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Protein | Ca2+ | Tb3+* | EGTA | Ca2+ |

| CD2.trigger | 90 ± 20a 240 ± 20b |

0.3 ± 0.1 c | 52 ± 1 | 54 ± 1 |

| CD2.trigger. R31K/K43D |

N/A | 5.7 ± 0.6 c | 56 ± 1 | 56 ± 1 |

| CD2.trigger. K31D/K43N |

N/A | 0.2 ± 0.04 c | 55 ± 1 | 56 ± 1 |

| Ca.CD2[23] | 1400 ± 400 | 8 ± 2 | 63 ± 2 | 63 ± 2 |

| w.t. CD2[23] | N/A | N/A | 61 ± 1 | 61 ± 1 |

Measured by NMR in 10 mM PIPES/10 mM KCl, pH 6.8.

Measured by ITC in 10 mM PIPES/10 mM KCl, pH 6.8.

Measured by FRET in 10 mM PIPES/10 mM KCl, pH 6.8.

Measured by CD in 10 mM MOPS/10 mM KCl, pH 6.8.

These binding affinities should be considered as the lower limits due to limitations of the direct titration method such as the concentration increment and accuracy, signal/noise ratio, and other factors. Our methods cannot measure any apparent Kd values smaller than 1 μM accurately.

It is interesting to note that the affinity for La3+ or Tb3+ is approximately 300-800-fold greater than for Ca2+. Like many natural Ca2+ binding proteins, CD2.trigger exhibits selective binding for Ca2+ and La3+ over excess physiological cations such as Mg2+ and K+. The addition of 2 mM Ca2+ or 1 mM La3+ following 100 mM K+ or 10 mM of Mg2+ led to significant changes in NMR spectra, suggesting that the specific binding of Ca2+ and La3+ cannot be shielded by the excess concentrations of K+ and Mg2+. Consistently, the addition of excess Mg2+ (10 mM) or K+ (> 100 mM) did not affect the Tb3+ fluorescence enhancement monitored by FRET.

Metal ion dependent conformational change

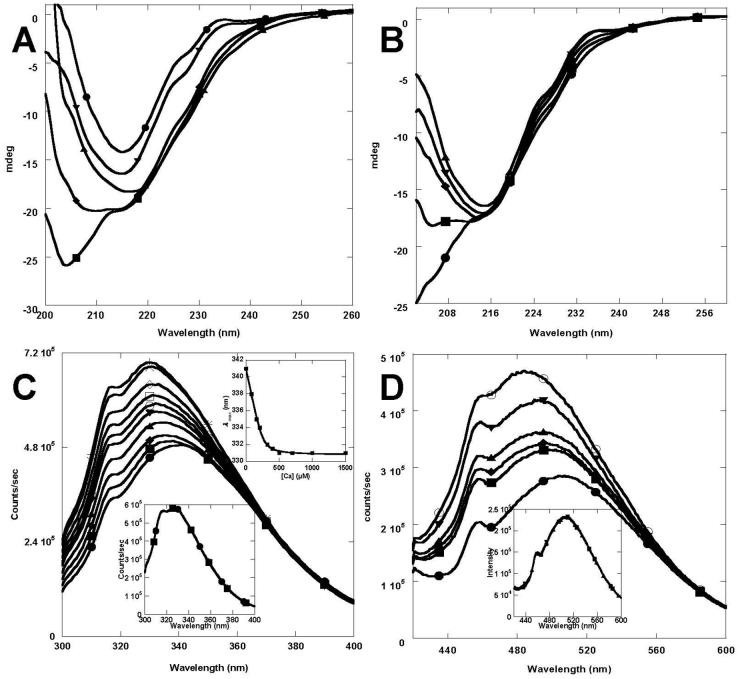

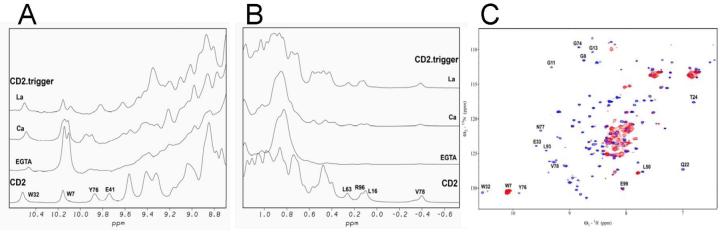

CD2.trigger undergoes the expected Ca2+-induced conformational change revealed by various spectroscopic methods. In the absence of Ca2+, Tb3+, or La3+ at physiological pH (7.2), the far UV CD spectrum of CD2.trigger has a minimum at 205 nm (Fig. 3A), suggesting the loss of β-strand secondary structure [24, 25]. In addition, the Trp fluorescence emission shifted to 341 nm (close to the 350 nm of free Trp) from the 327 nm of wild-type CD2 (Fig. 3C). This suggests that the buried Trp-32 in wild-type CD2 becomes solvent-exposed in CD2.trigger. In contrast, the Trp-fluorescence spectrum of wild-type CD2 changed with the addition of Ca2+ (Fig. 3C inset). Further, the hydrophobic dye ANS binding to CD2.trigger showed a 40% increase in fluorescence intensity with a 13 nm blue shift in the emission maximum wavelength when La3+ concentration increased from 0 to 10 μM, suggesting conformational changes of the CD2.trigger were induced by La3+-binding (Fig. 3D). Conversely, there were no detectable changes in the wild-type CD2 spectrum (Fig. 3D inset). In 1D NMR spectrum, the dispersed resonances around 10 and 0 ppm typically observed in wild-type CD2 disappeared in the CD2.trigger spectrum, indicating the loss of tertiary packing (Fig. 4A and 4B). Further, loss of secondary and tertiary structures in CD2.trigger was clearly demonstrated by the HSQC spectrum, in which all resonances were crowded into a narrow region (Fig. 4C).

Fig. 3.

Conformational studies as a function of metal ions. (A) Far UV CD spectra of 10 μM wild-type CD2 (●) and 10 μM CD2.trigger in the presence of 1 mM EGTA (■), 10 mM Ca2+ (◆), 0.1 mM La3+ (▲), or 0.1 mM Tb3+ (▼) in 10 mM Tris at pH 7.2. (B) Far UV CD spectra changes of CD2.trigger at varying Tb3+ concentrations in 20 mM Tris at pH 7.4. The Tb3+ concentrations were 0 (●), 1 (■), 2 (◆), 3 (▼), or 7 μM (▲), respectively. (C) Trp-fluorescence of 2 μM CD2.trigger at Ca2+ concentrations of 0, 0.08, 0.16, 0.21, 0.32, 0.4, 0.5, 0.7, 1.0, or 1.5 mM (bottom to top) in 20 mM Tris at pH 8.0 (excited at 280 nm). The fitting of λMax of Trp emission as a function of Ca2+ concentration gave the Kd of Ca2+ (inset up). The Trp-fluorescence spectra of wild-type CD2 were overlaid at different Ca2+ concentrations (inset low) (D) Fluorescence emission spectra of 50 μM ANS only (●) and 50 μM ANS with addition of 2 μM CD2.trigger in 20 mM Tris at pH 7.2 and in the presence of 0 (■), 1 (◆), 5 (▲), 7 (▼), or 10 μM (○) of La3+ (excited at 394 nm). The λMax of emission blue shifted and fluorescence intensity increased with increasing La3+ concentration, while the fluorescence intensity did increase for wild-type CD2 (inset).

Fig. 4.

NMR spectra. 1D 1H NMR spectra of CD2.trigger in the amide region (A) and the methyl group region (B) in the presence of 1 mM EGTA, 25 mM Ca2+, or 2 mM La3+. The bottom spectrum is wild-type CD2 in 1 mM EGTA. Some of the assigned resonances of CD2 are labeled. (C) Major resonances of CD2.trigger in the HSQC spectrum in the presence of 0.05 mM EGTA (red) are clustered in a narrow region, indicating the lack of well-packed tertiary structures. In the presence of 10 mM Ca2+ (blue), dispersed peaks as in wild-type CD2 are observed, indicating the formation of a well-folded structure.

Ca2+, Tb3+, or La3+-binding all refolded the CD2.trigger into a CD2-like structure. With the addition of Ca2+, Tb3+, or La3+, the spectra from far UV CD, fluorescence emission, and NMR were similar to those of wild-type CD2. The negative maximum at 216 nm in the CD spectra indicated the formation of β-strand structure, while the Trp emission at 333 nm and the NMR resonances in the 10 and 0 ppm regions indicated the formation of tightly-packed tertiary structure. The metal-induced conformational change is highly cooperative, shown by the concurrent formation of secondary and tertiary structures (Fig. 3). Ca2+ titrations showed that the fractional changes in CD signal, Trp emission fluorescence, and NMR chemical shifts of different resonances coincided. As a result, the different spectroscopic methods gave similar estimates for the metal binding affinity.

Removal of charge repulsion by protonation and mutations

We hypothesized that a major factor in the metal-binding induced conformation change is the reduction of the charge repulsion present in the metal binding site of CD2.trigger. To verify this hypothesis, two additional approaches were pursued to reduce the negative charges at the metal binding site. The first approach was to create two variants to reduce charge repulsion in the CD2.trigger by mutating the negatively-charged residues. Mutant R31D/K43N replaced a negatively charged Asp with a neutral Asn at position 43. Mutant R31K/K43D replaced an Asp in CD2.trigger with a positively charged Lys at position 31 (Fig. 1). In contrast to the unfolded conformation of apo CD2.trigger, the R31K/K43D mutant exhibited the folded conformation at pH up to 9, both in the absence and presence of cations (Fig. 6D). The R31D/K43N mutant was also folded below pH 9 in the absence of cations (Fig. 6C, Supplementary Fig. 3). In line with these experimental results, our electrostatic calculations predicted that the R31K/K43D and R31D/K43N mutations would increase the folding stability of CD2.trigger by 7.0 and 3.3 kcal/mol, respectively. While the magnitudes of the predictions from these crude calculations are questionable, they do strongly suggest that modulations of charge-charge interactions constitute a dominant factor in the increase in folding stability by the R31K/K43D and R31D/K43N mutations. The experimental and calculated results for the R31K/K43D and R31D/K43N variants directly support the hypothesis that the unfolding of CD2.trigger in the apo form is due to charge repulsion at the metal binding site, and the metal-induced folding is due to reduction of the charge repulsion. Clearly, this “hot spot” location of the Ca2+-binding site is very sensitive to the alteration of electrostatic interactions and charge repulsion (Fig. 1).

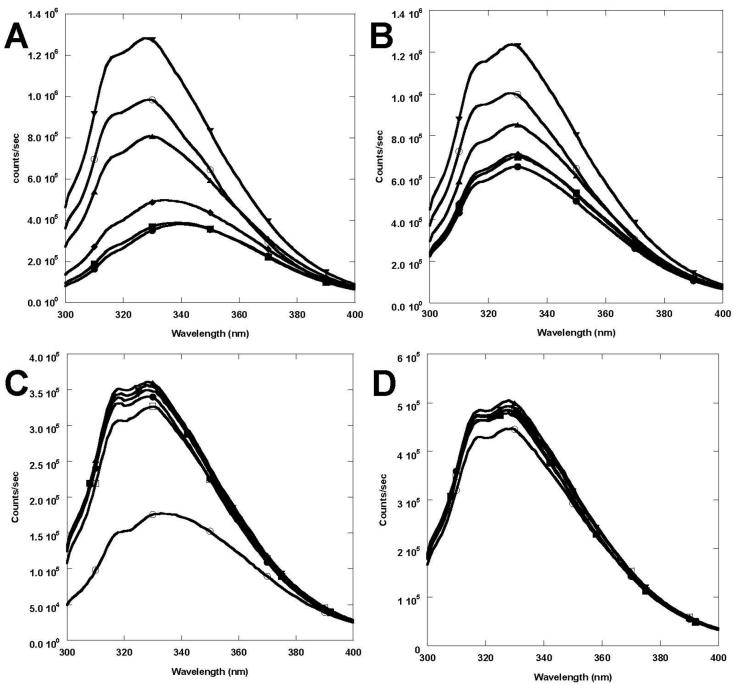

Fig. 6.

Tryptophan emission fluorescence spectra. CD2.trigger spectra (excited at 280 nm) in the absence (A) or presence of 0.5 mM Ca2+ (B) at pH 9.0 (●), 8.5 (■), 8.0 (◆), 7.4 (▲), 7.0 (▼), or 6.5 (○) as well asR31D/ K43N (C) and R31K/K43D (D) in acetate buffer (pH 4.0) in the presence of 1 mM EGTA (●) or Ca2+ (■), in PIPES buffer (pH 6.8) in the presence of 1 mM EGTA (▲) or 0.5 mM Ca2+(▼), and in Tris buffer (pH 9.0) in the presence of 1 mM EGTA (○) or 0.5 mM Ca2+ (□).

The thermal stability of CD2.trigger and its variants in the absence and presence of 10 mM Ca2+ was monitored using CD at 230 nm at pH 6.8. The three proteins had similar far UV CD spectra at low temperatures (5 °C) and underwent reversible thermal denaturation with the negative maximum shifting to 202 nm at high temperatures. The Tm values of the three proteins did not exhibit significant differences at pH 6.8 (Table 1).

The second approach was to lower the pH. Specifically, if the reduction of charge repulsion is the driving force for the metal-binding induced conformational change, lowering the pH should neutralize some of the negative coordination charges and thereby shift CD2.trigger toward the folded conformation. Consistent with this expectation, when pH was lowered below 7, CD2.trigger gradually converted to the native structure from its unfolded conformation (Fig. 5A), which closely resembles the Ca2+-, Tb3+-, or La3+-induced refolding (Fig. 3A). The Trp fluorescence emission maximum blue-shifted to 327 nm at pH 7 (Fig. 6A). In addition, we observed a concurrent increase in the emission intensity, likely a result of the increased hydrophobicity of the Trp environment. The NMR (Supplementary Fig. 2) spectra provided further evidence that the protonation-induced folding process was similar to the Ca2+, Tb3+, or La3+-induced folding process. The pH-dependent transition curves can be fitted with a two-state model. In the absence of metal ion, the transition pH values determined by the different spectroscopic methods were all near 7.2 (Fig. 5B). The folding-unfolding transition pH was increased in the presence of Ca2+ or Tb3+. Far UV CD and Trp fluorescence studies showed that at pH 7.4, CD2-trigger was predominantly unfolded in the absence of metal ion but became predominantly folded in the presence of 7 μM Tb3+ (Fig. 3B) or 0.5 mM Ca2+ (Fig. 3C). In the presence of saturating amounts of cations, the apparent transition pH increased from 7.2 ± 0.1 to 8.5 ± 0.1 for Tb3+ (Fig. 5B). Folding or refolding was achieved by addition of metal ions, reduction of pH, or a combination of the two conditions. The effects of metal binding and protonation were additive.

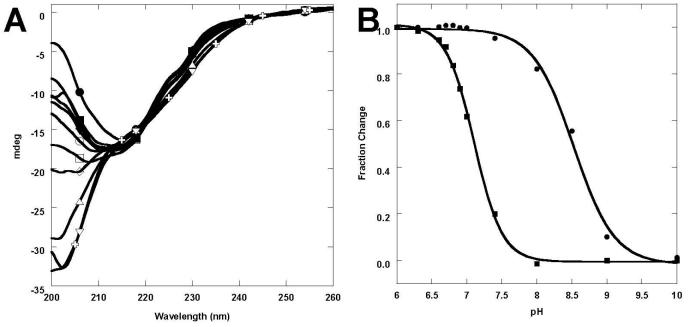

Fig. 5.

Conformational studies as a function of pH. (A) Far UV CD spectra of CD2.trigger at pH 9.0, 8.0, 7.4, 7.0, 6.8, 6.6, 6.4, 6.2, 6.0 5.8, or 4.5 (bottom to top) in the absence of metal ion. (B) The signal changes of CD2.trigger as a function of pH in the absence (■) or presence (●) of 20 μM Tb3+.

Discussion

Electrostatic interactions and protein folding

The folding stability of proteins depends on delicate balances of non-covalent interactions such as salt bridges, hydrogen bonding networks, and van der Waals and hydrophobic interactions. The electrostatic interactions between charged residues are long ranged. Due to their strong favorable interactions with water, charged residues are predominantly located on the surface of proteins. Changes in salt concentrations or pH often have a significant effect on the charge interactions.

Negatively-charged residues are often observed around Ca2+-binding pockets. Charged residues are important for tuning metal binding affinity and selectivity [8, 23]. However, in the absence of cation binding, the repulsion between charged residues often destabilizes the proteins. For example, Ca2+-loaded CaM has high thermal stability with Tm > 90 °C while the apo-form is labile even at room temperature [32, 33]. Further, the removal of Ca2+ ions results in a molten globular state of α-lactalbumin [34]. Similarly, introduction of a fifth charge in the parvalbumin Ca2+-binding sites results in a decrease of protein thermal stability in the absence of Ca2+ [35]. Besides charge effects, Ca2+ binding may also result in changes in local conformations and dynamics that tune the function and stability of these proteins [36, 37]. In natural proteins, Ca2+-binding sites are almost all located within loop regions, turns, or the ends of α-helices or β-sheets, probably due to their relatively higher flexibility [12].

To design Ca2+-binding sites, we have introduced charged and non-charged carboxyl residues in a non-Ca2+-binding protein frame CD2. This mutation process results in proteins with different folding properties depending on the nature of the changes, the number of charged residues, and locations in the protein environment. Our first generation of designed Ca2+-binding sites, such as the one in Ca.CD2, were created by mutating four core hydrophobic residues and one positively charged residue into four negatively charged residues [18-20]. This protein was largely unfolded both for apo and loaded forms. We then designed a second generation of Ca2+-binding sites such as Ca.CD2 which was capable of resisting global conformational changes upon Ca2+ binding as a result of reducing either the number of mutations or the number of charged ligand residues. Interestingly, the Ca2+-binding site in CD2.7E15 created by adding three negatively-charged residues coupled with two existing residues Glu56 and Asp 62 with a total of five-negatively charged ligand residues is able to retain native structure in the absence and presence of Ca2+. It is also interesting to note that CD2.6D79 formed by the cluster of two new negative charges within β-strands exhibits smaller backbone changes upon mutation [22] compared with CD2.7E15 within loops [23], possibly due to limited flexibility of the backbone and minimal perturbation of the native environment.

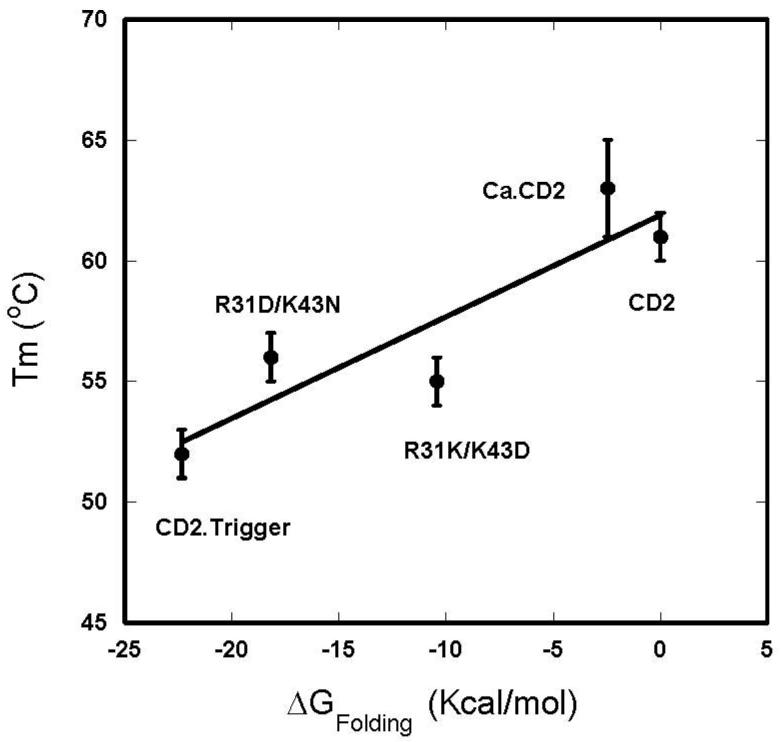

Altering electrostatic interactions may result in either an increase or decrease in protein stability [38, 39]. In favorable cases, the effects on protein stability can be predicted by electrostatic calculations [40]. As shown in Fig. 7, the calculations predict that CD2.trigger and two mutants with altered charges at the Ca2+ binding site have the following stability: w.t. CD2 > R31K/K43D > R31D/K43N > CD2.trigger. The cluster of negative charges designed into the Ca2+ binding site of CD2.trigger presents an opportunity to validate these predictions. This predicted order is consistent with the measured melting temperatures of the five protein variants including Ca.CD2 at different locations. The electrostatic calculations thus provide corroborating evidence that the driving force for the metal-binding induced folding of CD2.trigger is the reduction of charge repulsion present in the apo protein at pH 6.8. Further, consistent with our observations, our electrostatic calculations predict that the CD2.trigger has the lowest stability and Ca.CD2 has the highest stability in the absence of Ca2+ (Fig. 7).

Fig. 7.

Thermal transition temperature (Tm) of CD2 and its variants in the presence of 1mM EGTA as a function of calculated folding energy change (ΔGFolding) from w.t. CD2.

Because a metal binds either preferentially or exclusively to the folded state, metal binding always increases the folding stability of a protein. The degree of increase depends on the binding affinity and the metal concentration. For example, Ca2+ shifts the Tm of E-cadherin from 40°C to 65°C [41]. The Tm values of α- and β-parvalbumin CD-EF fragments increase more than 20°C as the Ca2+ concentration moderately increases from 0.25 or 0.5 mM to 1 mM [39]. Conversely, the loss of Ca2+ binding often decreases the protein stability. We did not detect a change in Tm for the R31K/K43D variant but observed small increases in Tm for both CD2.trigger and the R31D/K43N variant. Given the fact that the different charged variants have almost identical CD spectra at high temperature and the folding of native conformation is Ca2+, Tb3+, or La3+ specific, independent of excess Na+ or K+, it is less likely that the unfolded state is stabilized by the addition of extra surface negative charges.

Metal-induced conformational change in CD2.trigger

The design of CD2.trigger is based on our hypothesis that clustering of charged coordination residues and the alteration of native electrostatic balance greatly destabilizes the protein, and Ca2+ binding at the location will mitigate such effects. The single Ca2+-binding site in CD2.trigger is located at a charge-sensitive “hot spot” identified by electrostatic calculations. Using various spectroscopic methods, we have shown that the four proximate negative charges of Glu-29, Asp-31, Glu-41, and Asp-43 at the surface of the wild-type CD2 β-sandwich structure significantly destabilized the protein and resulted in the unfolding of the protein at room temperature at pH 7.4. At pH 6.8, the protein became folded due to neutralization of charge repulsion. Similarly, charge mutation by the R31D/K43N or R31K/K43D substitution stabilized the folded state. The folding-unfolding process of CD2.trigger is reversible following a two-state model.

The pKa of wild-type CD2 was examined using 15N labeled protein and by site-directed mutagenesis [42]. Glu-41 in wild-type CD2 has an unusually high pKa of 6.6, which is attributed to the hydrogen bond between protonated Glu-41 and deprotonated Glu-29 in close proximity. In principle, as nearby negative charges aid in the protonation, the pKa of Glu-41 in CD2.trigger is not likely to be lower than that in wild-type CD2. At high pH, it is reasonable to assume that the four proposed coordination residues in CD2.trigger possess four negative charges. Upon binding of Ca2+, Tb3+, or La3+, the net charges are reduced to −2 or −1. The effect of a pH change on the net charge of the metal binding site is dependent upon the pKa of the residues. Therefore, decreasing to a slightly acidic pH of 6.6 may significantly reduce the net negative charges at the metal binding site. The folding of the protein under this condition allows us to conclude that the location of CD2.trigger Ca2+-binding site is capable of tolerating three negative charges. However, the repulsion introduced by the fourth charged residue exceeds the tolerance range of the β-strand of wild-type CD2 Ig-fold structure. The mutants, R31K/K43D and R31D/K43N with a −2 and −3 charge in the binding site, respectively, maintain the wild-type CD2 structure in the absence of cations at basic pH, thus supporting conclusions derived from the analysis of the pH study.

The observed enthalpy for Ca2+ binding to CD2.trigger is only −0.93 kcal mol−1. The small magnitude of ΔH may be due to the protein undergoing an unfolded-to-folded transition upon Ca2+ binding attributable to large change in conformational entropy. Such coupled folding-binding is reminiscent of natural trigger proteins with small heat releases. Several groups have reported that Ca2+ binding can lead to either heat release or absorbance depending on the site [31, 39, 43]. For example, the binding of Ca2+ to high-affinity sites in C2 domains is exothermic while binding to low-affinity sites is endothermic [44]. Gilli et al have reported that Ca2+ binding to CaM has both an exothermic and an endothermic phase [29]. Decreases in backbone entropy upon Ca2+ binding has been determined by NMR relaxation for several proteins with high-affinity binding sites [37, 45]. On the other hand, a study of one of our designed proteins has shown that the backbone entropy of the protein increases slightly upon Ca2+ binding. For natural trigger proteins, due to the mutual influence of multiple metal binding sites [21], the dissection of the relative contributions of specific interactions and conformational change to Ca2+ binding is often controversial [29].

Design of trigger proteins

Extensive studies have been carried out to understand the molecular mechanisms of Ca2+-dependent processes with various approaches including structure determination of apo and loaded forms of the trigger proteins. To date, the reported studies mainly focus on natural Ca2+-dependent proteins such as CaM. Development of novel Ca2+-dependent proteins has been attempted by mimicking the natural Ca2+-binding proteins which have multiple coupled metal-binding sites. Desjarlais and colleagues [13] have abolished the Ca2+-induced conformational change of N-terminal CaM by replacing its hydrophilic residues with large hydrophobic residues as found in calbindin D9k, which does not undergo global conformational change upon Ca2+ binding. Conversely, Bunick et al. [14] built up the CaM-like Ca2+-dependent conformational change in calbindin D9k by replacing 15 residues in calbindin D9k with the corresponding residues of CaM. Structural determination and other methods confirmed that the exposed hydrophobic surfaces on the Ca2+-loaded form of the new protein are similar to what is found on CaM.

Departing from previously reported methods, we do not rely on the use of sequence similarity between known Ca2+-dependent proteins. The de novo design of CD2.trigger is achieved by coupling protein destabilization via the electrostatic repulsion among introduced Ca2+-coordination residues and the reacquisition of protein folding upon Ca2+ binding. We have previously reported the success of designing several Ca2+-binding proteins resistant to global conformational changes upon Ca2+ binding [20, 21, 23]. The sites in these proteins are either partially located within flexible regions, or have only 2-3 clustered negatively charged residues. While the algorithms used to identify/design Ca2+ binding sites are the same, we have added major components to localize conformationally sensitive spots and to specifically incorporate electrostatic interactions that globally switch the conformation of the designed protein as a result of Ca2+, Tb3+, or La3+ binding. To create Ca2+-binding proteins with Ca2+-induced global conformational change, we have developed several new criteria to ensure a strong local charge interaction and strong metal binding, as well as methods to analyze and alter charge distribution on the host protein. In the absence of Ca2+, CD2.trigger is highly dynamic, mobile, and possesses less tertiary structures than natural trigger proteins such as CaM or TnC. To our knowledge, this is the first study to report the successful design of Ca2+-, Tb3+-, or La3+-induced trigger proteins with a single metal binding site that do not rely on the use of sequence similarity to known Ca2+-dependent proteins with multiple coupled metal-binding sites. The success in achieving a Ca2+-dependent conformational change represents a major step forward from our previously published work.

Our design of a Ca2+-binding trigger protein is significant for several reasons. First, this engineered protein can be utilized to study signal transduction systems involving Ca2+ [46] as well as Ca2+-dependent cell adhesion [47], so this achievement moves beyond design, into functional application. Second, the isolated metal-binding site in our design allows us to better elucidate key binding determinants, such as charge repulsions that contribute to Ca2+ binding, and the resulting conformational changes. Data obtained from this strategy will provide insight into the mechanisms of Ca2+ mediated signaling and the molecular bases for diseases associated with alterations in Ca2+ binding. Finally, these results provide guidance for the design of Ca2+-switchable proteins such as sensors or catalysts [48, 49].

Materials and methods

Design of Ca2+ binding site

The design of Ca2+ binding sites was carried out on an SGI O2 computer using the MetalFinder program as described previously [19, 50]. The CD2 protein (PDB code 1hng) was chosen as the scaffold. The protein surface potential was calculated by using the DelPhi program on modeled structures. The modeled structure of the designed protein was generated by the design program and the structures of its variants were generated using the SYBYL program (Tripos Co.).

Refinement of model structures by energy minimization

The structures of CD2.trigger and its R31K/K43D and R31D/K43N mutants were further refined using the AMBER program [51]. The Ca2+-loaded structure of CD2.trigger generated by the SYBYL program was energy minimized within the AMBER ff99SB forcefield [52]. Minimization was completed in two stages. First, 2,000 steps of minimization were carried out while the Ca2+-loaded protein was restrained with a harmonic constant of 100 kcal/mol/Å. Second, 20,000 steps of minimization were carried out without restraints. Mutations were generated on the minimized CD2.trigger structure by the LEAP module in AMBER. The resulting mutated side chain was energy minimized for at least 40,000 steps while the rest of the Ca2+-loaded protein was fixed in space.

Effects of mutation on binding energy and folding stability

Electrostatic contributions of mutational effects on the Ca2+-binding affinity and folding stability of CD2.trigger were calculated using the Poisson-Boltzmann (PB) equation. PB calculations were carried out using the UHBD program [53]. The calculation protocols on electrostatic contributions to protein binding and folding stability were followed as described previously [40, 54]. The protein and the solvent were modeled with dielectric constants of 4 and 78.5, respectively, with the dielectric boundary specified by the protein van der Waals surface. The buffer was modeled as a 1:1 salt (with an ion exclusion radius of 2 Å) at a concentration of 20 mM and a temperature of 298 K. The solution of the PB equation started with a 150 × 150 × 150 grid at a 1.5 Å spacing. This was followed by two levels of focusing, with the same grid dimensions but the spacing was reduced to 0.5 Å and 0.25 Å, respectively. The center of the second focusing grid was changed from the center of the protein to the site of mutation. The effect of a mutation on the Ca2+-binding affinity was calculated as the change in the electrostatic binding free energy by the mutation. The electrostatic binding free energy was the difference in the total electrostatic free energy, before and after Ca2+ binding:

| (1) |

where the three terms on the right-hand side (from left to right) represent the electrostatic energies of the Ca2+-loaded protein, the apo protein, and the Ca2+ ion. In this calculation, the apo protein was assumed to have the same structure as the Ca2+-loaded form. Similarly, the effect of a mutation on the folding stability was calculated as the change in the electrostatic folding free energy by the mutation. The electrostatic folding free energy was the difference in the total electrostatic free energy of the protein in the unfolded and folded states:

| (2) |

In this calculation, the folded protein was assumed to have the same structure as the Ca2+-loaded form, even though the ion was absent. The unfolded state was modeled as the individual residues separately dissolved in the solvent. Since the quantity of interest was the change in ΔGf by a mutation and the contributions of all separately dissolved residues other than the one being mutated were identical before and after mutation, only the electrostatic free energy of the residue being mutated, Gel(residue), was required for modeling the unfolded state.

Protein engineering and purification

The cloning, expression, and purification of CD2.trigger followed established methods for GST-fusion proteins with minor modifications [19, 20]. Briefly, the cell was lysed with 1% N-lauroylsarcosine sodium in pH 7.0 Tris buffer with the addition of 5 mM DTT, 5 μM 4-(2-Aminoethyl) benzenesulfonyl fluoride hydrochloride (AEBSF), 50 μM La3+, and 25 U/ml Benzonase nuclease (Novagen). The GST-fusion proteins were bound to a GS4-B affinity column (Amersham) and cleaved on the column by thrombin (Amersham). The eluted protein was further purified by Superdex G75 gel filtration chromatography (Amersham) and HiTrap SP cation exchange FPLC (Amersham). EGTA (0.5 mM) was added to the protein solution before HiTrap SP cation exchange FPLC to remove metal ions bound to the protein.

Fluorescence, CD spectroscopy and NMR spectra

All fluorescence, circular dichroism (CD) and NMR spectra were collected as previously described [19, 20]. The dye 1-anilinonapthalene-8-sulfonic acid (ANS) (Sigma Co.) in 20 mM Tris pH 7.2 was titrated with La3+ in the presence and absence of proteins and 10 minutes were allowed for equilibrium at each data point. The emission scans were acquired from 425 nm to 700 nm with an excitation at 364 nm. For the CD study, the metal free protein (10 μM) sample contained 1 mM EGTA and the cation-loaded samples contained 10 mM Ca2+ or 0.1 mM La3+ or Tb3+. The pH was varied from 5.8 to 9.0 for the pH study. For the thermal stability study, the temperature was increased from 5°C to 90°C at 2°C increments, with a 10 minute equilibration time at each temperature. Protein samples (10 μM) contained 1 mM EGTA or 10 mM Ca2+. The metal binding affinities were derived from metal titrations by fitting the signal changes from CD, fluorescence, or NMR as a function of metal concentration, assuming the formation of 1:1 protein-cation complex as previously described [19, 20]

Isothermal titration calorimetry

The ITC experiment was performed in a VP-ITC (MicroCal, LLC). The sample cell contained 0.1 mM of protein in 20 mM PIPES/10 mM KCl at pH 6.8. The injection solution contained 5 mM of Ca2+ in the same buffer, and a volume of 2 μL was injected each time. The reference power was 5 μCal/sec. The initial delay time was 300 sec and the stirring speed was 280 rpm. The cell temperature was set to 5°C. The sample cell and syringe were pre-treated with 20 mM EGTA and washed with 20 mM PIPES/10 mM KCl at pH 6.8. All solutions for metal-binding studies were pre-treated with Chelex-100 (Bio-Rad). The data were analyzed using the Microcal Origin software (Microcal Software Co.).

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank Dan Adams, Michael Kirberger, and Julian Johnson for their critical review of this manuscript and helpful discussions, and David W. Wilson for assistance in running the ITC. This work is supported in part by the following sponsors: NIH GM070555, NIH GM 62999, and NSF MCB-0092486 to JJY; NIH GM058187 to HXZ; and the Equipment Funds from the Georgia Research Alliance.

REFERENCES

- 1.Ikura M, Ames JB. Genetic polymorphism and protein conformational plasticity in the calmodulin superfamily: two ways to promote multifunctionality. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2006;103:1159–64. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0508640103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kretsinger RH. Calcium-binding proteins. Annu Rev Biochem. 1976;45:239–66. doi: 10.1146/annurev.bi.45.070176.001323. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Klee CB, Crouch TH, Richman PG. Calmodulin. Annu Rev Biochem. 1980;49:489–515. doi: 10.1146/annurev.bi.49.070180.002421. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Meador WE, Means AR, Quiocho FA. Modulation of calmodulin plasticity in molecular recognition on the basis of x-ray structures. Science. 1993;262:1718–21. doi: 10.1126/science.8259515. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Chou JJ, Li S, Klee CB, Bax A. Solution structure of Ca(2+)-calmodulin reveals flexible hand-like properties of its domains. Nat Struct Biol. 2001;8:990–7. doi: 10.1038/nsb1101-990. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Frederick KK, Marlow MS, Valentine KG, Wand AJ. Conformational entropy in molecular recognition by proteins. Nature. 2007;448:325–9. doi: 10.1038/nature05959. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Reid RE, Hodges RS. Co-operativity and calcium/magnesium binding to troponin C and muscle calcium binding parvalbumin: an hypothesis. J Theor Biol. 1980;84:401–44. doi: 10.1016/s0022-5193(80)80013-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Falke JJ, Drake SK, Hazard AL, Peersen OB. Molecular tuning of ion binding to calcium signaling proteins. Q Rev Biophys. 1994;27:219–90. doi: 10.1017/s0033583500003012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Linse S, Forsen S. Determinants that govern high-affinity calcium binding. Adv Second Messenger Phosphoprotein Res. 1995;30:89–151. doi: 10.1016/s1040-7952(05)80005-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Glusker JP. Structural aspects of metal liganding to functional groups in proteins. Adv Protein Chem. 1991;42:1–76. doi: 10.1016/s0065-3233(08)60534-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Zhou Y, Yang W, Kirberger M, Lee HW, Ayalasomayajula G, Yang JJ. Prediction of EF-hand calcium-binding proteins and analysis of bacterial EF-hand proteins. Proteins. 2006;65:643–55. doi: 10.1002/prot.21139. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Pidcock E, Moore GR. Structural characteristics of protein binding sites for calcium and lanthanide ions. J Biol Inorg Chem. 2001;6:479–89. doi: 10.1007/s007750100214. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ababou A, Desjarlais JR. Solvation energetics and conformational change in EF-hand proteins. Protein Sci. 2001;10:301–12. doi: 10.1110/ps.33601. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Bunick CG, Nelson MR, Mangahas S, Hunter MJ, Sheehan JH, Mizoue LS, Bunick GJ, Chazin WJ. Designing sequence to control protein function in an EF-hand protein. J Am Chem Soc. 2004;126:5990–8. doi: 10.1021/ja0397456. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Batey S, Randles LG, Steward A, Clarke J. Cooperative folding in a multi-domain protein. J Mol Biol. 2005;349:1045–59. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2005.04.028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Yang JJ, Gawthrop A, Ye Y. Obtaining site-specific calcium-binding affinities of calmodulin. Protein Pept Lett. 2003;10:331–45. doi: 10.2174/0929866033478852. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Ye Y, Lee HW, Yang W, Shealy S, Yang JJ. Probing site-specific calmodulin calcium and lanthanide affinity by grafting. J Am Chem Soc. 2005;127:3743–50. doi: 10.1021/ja042786x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Yang W, Lee HW, Hellinga H, Yang JJ. Structural analysis, identification, and design of calcium-binding sites in proteins. Proteins. 2002;47:344–56. doi: 10.1002/prot.10093. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Yang W, Jones LM, Isley L, Ye Y, Lee HW, Wilkins A, Liu ZR, Hellinga HW, Malchow R, Ghazi M, Yang JJ. Rational design of a calcium-binding protein. J Am Chem Soc. 2003;125:6165–71. doi: 10.1021/ja034724x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Yang W, Wilkins AL, Ye Y, Liu ZR, Li SY, Urbauer JL, Hellinga HW, Kearney A, van der Merwe PA, Yang JJ. Design of a calcium-binding protein with desired structure in a cell adhesion molecule. J Am Chem Soc. 2005;127:2085–93. doi: 10.1021/ja0431307. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Yang W, Wilkins AL, Li S, Ye Y, Yang JJ. The effects of Ca2+ binding on the dynamic properties of a designed Ca2+-binding protein. Biochemistry. 2005;44:8267–73. doi: 10.1021/bi050463n. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Jones LM, Yang W, Maniccia AW, Harrison A, van der Merwe PA, Yang JJ. Rational design of a novel calcium-binding site adjacent to the ligand-binding site on CD2 increases its CD48 affinity. Protein Sci. 2008;17:439–49. doi: 10.1110/ps.073328208. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Maniccia AW, Yang W, Li SY, Johnson JA, Yang JJ. Using protein design to dissect the effect of charged residues on metal binding and protein stability. Biochemistry. 2006;45:5848–56. doi: 10.1021/bi052508q. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Driscoll PC, Cyster JG, Campbell ID, Williams AF. Structure of domain 1 of rat T lymphocyte CD2 antigen. Nature. 1991;353:762–5. doi: 10.1038/353762a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Jones EY, Davis SJ, Williams AF, Harlos K, Stuart DI. Crystal structure at 2.8 A resolution of a soluble form of the cell adhesion molecule CD2. Nature. 1992;360:232–9. doi: 10.1038/360232a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Wagner G. E-cadherin: a distant member of the immunoglobulin superfamily. Science. 1995;267:342. doi: 10.1126/science.7824932. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Yang JJ, Ye Y, Carroll A, Yang W, Lee HW. Structural biology of the cell adhesion protein CD2: alternatively folded states and structure-function relation. Curr Protein Pept Sci. 2001;2:1–17. doi: 10.2174/1389203013381251. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Honig B, Nicholls A. Classical electrostatics in biology and chemistry. Science. 1995;268:1144–9. doi: 10.1126/science.7761829. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Gilli R, Lafitte D, Lopez C, Kilhoffer M, Makarov A, Briand C, Haiech J. Thermodynamic analysis of calcium and magnesium binding to calmodulin. Biochemistry. 1998;37:5450–6. doi: 10.1021/bi972083a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Reddi AR, Gibney BR. Role of protons in the thermodynamic contribution of a Zn(II)-Cys4 site toward metalloprotein stability. Biochemistry. 2007;46:3745–58. doi: 10.1021/bi062253w. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Griko YV, Remeta DP. Energetics of solvent and ligand-induced conformational changes in alpha-lactalbumin. Protein Sci. 1999;8:554–61. doi: 10.1110/ps.8.3.554. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Protasevich I, Ranjbar B, Lobachov V, Makarov A, Gilli R, Briand C, Lafitte D, Haiech J. Conformation and thermal denaturation of apocalmodulin: role of electrostatic mutations. Biochemistry. 1997;36:2017–24. doi: 10.1021/bi962538g. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Tsalkova TN, Privalov PL. Thermodynamic study of domain organization in troponin C and calmodulin. J Mol Biol. 1985;181:533–44. doi: 10.1016/0022-2836(85)90425-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Schulman BA, Kim PS, Dobson CM, Redfield C. A residue-specific NMR view of the non-cooperative unfolding of a molten globule. Nat Struct Biol. 1997;4:630–4. doi: 10.1038/nsb0897-630. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Henzl MT, Hapak RC, Goodpasture EA. Introduction of a fifth carboxylate ligand heightens the affinity of the oncomodulin CD and EF sites for Ca2+ Biochemistry. 1996;35:5856–69. doi: 10.1021/bi952184d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Smallridge RS, Whiteman P, Werner JM, Campbell ID, Handford PA, Downing AK. Solution structure and dynamics of a calcium binding epidermal growth factor-like domain pair from the neonatal region of human fibrillin-1. J Biol Chem. 2003;278:12199–206. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M208266200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Gagne SM, Tsuda S, Spyracopoulos L, Kay LE, Sykes BD. Backbone and methyl dynamics of the regulatory domain of troponin C: anisotropic rotational diffusion and contribution of conformational entropy to calcium affinity. J Mol Biol. 1998;278:667–86. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.1998.1723. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Strickler SS, Gribenko AV, Gribenko AV, Keiffer TR, Tomlinson J, Reihle T, Loladze VV, Makhatadze GI. Protein stability and surface electrostatics: a charged relationship. Biochemistry. 2006;45:2761–6. doi: 10.1021/bi0600143. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Henzl MT, Agah S, Larson JD. Characterization of the metal ion-binding domains from rat alpha- and beta-parvalbumins. Biochemistry. 2003;42:3594–607. doi: 10.1021/bi027060x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Dong F, Zhou HX. Electrostatic contributions to T4 lysozyme stability: solvent-exposed charges versus semi-buried salt bridges. Biophys J. 2002;83:1341–7. doi: 10.1016/S0006-3495(02)73904-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Prasad A, Pedigo S. Calcium-dependent stability studies of domains 1 and 2 of epithelial cadherin. Biochemistry. 2005;44:13692–701. doi: 10.1021/bi0510274. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Chen HA, Pfuhl M, McAlister MS, Driscoll PC. Determination of pK(a) values of carboxyl groups in the N-terminal domain of rat CD2: anomalous pK(a) of a glutamate on the ligand-binding surface. Biochemistry. 2000;39:6814–24. doi: 10.1021/bi992209z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Jelesarov I, Bosshard HR. Isothermal titration calorimetry and differential scanning calorimetry as complementary tools to investigate the energetics of biomolecular recognition. J Mol Recognit. 1999;12:3–18. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1099-1352(199901/02)12:1<3::AID-JMR441>3.0.CO;2-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Torrecillas A, Laynez J, Menendez M, Corbalan-Garcia S, Gomez-Fernandez JC. Calorimetric study of the interaction of the C2 domains of classical protein kinase C isoenzymes with Ca2+ and phospholipids. Biochemistry. 2004;43:11727–39. doi: 10.1021/bi0489659. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Akke M, Skelton NJ, Kordel J, Palmer AG, 3rd, Chazin WJ. Effects of ion binding on the backbone dynamics of calbindin D9k determined by 15N NMR relaxation. Biochemistry. 1993;32:9832–44. doi: 10.1021/bi00088a039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Hofer AM, Brown EM. Extracellular calcium sensing and signalling. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2003;4:530–8. doi: 10.1038/nrm1154. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Kemler R, Ozawa M, Ringwald M. Calcium-dependent cell adhesion molecules. Curr Opin Cell Biol. 1989;1:892–7. doi: 10.1016/0955-0674(89)90055-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Mizoue LS, Chazin WJ. Engineering and design of ligand-induced conformational change in proteins. Curr Opin Struct Biol. 2002;12:459–63. doi: 10.1016/s0959-440x(02)00348-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Lu Y, Berry SM, Pfister TD. Engineering novel metalloproteins: design of metal-binding sites into native protein scaffolds. Chem Rev. 2001;101:3047–80. doi: 10.1021/cr0000574. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Deng H, Chen G, Yang W, Yang JJ. Predicting calcium-binding sites in proteins-A graph theory and geometry approach. Proteins. 2006 doi: 10.1002/prot.20973. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Case DA, Darden TA, Cheatham TE, III, Simmerling CL, Wang J, Duke RE, Luo R, Merz KM, Pearlman DA, Crowley M, Walker RC, Zhang W, Wang B, Hayik S, Roitberg A, Seabra G, Wong KF, Paesani F, Wu X, Brozell S, Tsui V, Gohlke H, Yang L, Tan C, Mongan J, Hornak V, Cui G, Beroza P, Mathews DH, Schafmeister C, Ross WS, Kollman PA. 2006 AMBER 9 in. [Google Scholar]

- 52.Hornak V, Abel R, Okur A, Strockbine B, Roitberg A, Simmerling C. Comparison of multiple Amber force fields and development of improved protein backbone parameters. Proteins. 2006;65:712–25. doi: 10.1002/prot.21123. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Madura JD, Briggs JM, Wade R, Davis ME, Luty BA, Ilin A, Antosiewicz J, Gilson MK, Bagheri B, Scott LR, McCammon JA. Electrostatics and diffusion of molecules in solution: simulations with the University of Houston Brownian Dynamics program. Computer Physics Communications. 1995;91:57–95. [Google Scholar]

- 54.Dong F, Vijayakumar M, Zhou HX. Comparison of calculation and experiment implicates significant electrostatic contributions to the binding stability of barnase and barstar. Biophys J. 2003;85:49–60. doi: 10.1016/S0006-3495(03)74453-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.