Abstract

This paper examines the concept of resilience in the context of children affected by armed conflict. Resilience has been frequently viewed as a unique quality of certain ‘invulnerable’ children. In contrast, this paper argues that a number of protective processes contribute to resilient mental health outcomes in children when considered through the lens of the child's social ecology. While available research has made important contributions to understanding risk factors for negative mental health consequences of war-related violence and loss, the focus on trauma alone has resulted in inadequate attention to factors associated with resilient mental health outcomes. This paper presents key studies in the literature that address the interplay between risk and protective processes in the mental health of war-affected children from an ecological, developmental perspective. It suggests that further research on war-affected children should pay particular attention to coping and meaning making at the individual level; the role of attachment relationships, caregiver health, resources and connection in the family, and social support available in peer and extended social networks. Cultural and community influences such as attitudes towards mental health and healing as well as the meaning given to the experience of war itself are also important aspects of the larger social ecology.

Introduction

Wars are dramatically altering the lives of children around the world. UNICEF (2006) reports that conflicts in the last decade have killed an estimated 2 million children and have left another 6 million disabled, 20 million homeless, and over 1 million separated from their parents. The changing tactics and technology of warfare have magnified hazards to children. Wars are increasingly fought within states and involve non-state actors, such as rebel or terrorist groups less likely to be aware of, or abide by, humanitarian laws providing for the protection of civilians (Stichick & Bruderlein, 2001). As a result, modern ‘wars of destabilization’ (Stichick & Bruderlein, 2001) often rupture the fabric of life that supports healthy child development. Wars sever families and extended social networks, interrupt services systems and often feed deep ethnic and political divides.

The evidence base on prevention and intervention efforts to improve the situation of children in armed conflict remains nascent (Machel, 1996, 2001; Betancourt & Williams, 2008). Recent years have brought increased research attention to the topic (Barenbaum, Ruchkin, & Schwab-Stone, 2004; Bayer, Klasen, & Adam, 2007; Bolton et al., 2007; Lustig et al., 2004; Vinck, Pham, Stover, & Weinstein, 2007). This paper examines the concept of resilience in the context of children affected by armed conflict with particular attention to potentially modifiable protective processes which may be the targets of intervention. Though various definitions of resilience arise in the literature (Cicchetti & Garmezy, 1993; Gordon & Song, 1994; Kaufman et al., 1994; Luthar, 1993; Luthar & Cushing, 1999; Masten, Best, & Garmezy, 1991, Masten, 1994; Rutter, 1985, 1987, 1990; Stouthamer-Loeber et al., 1993; Tarter & Vanyulov, 1999; Tolan, 1996), we use the following definition of ‘resilience’: the attainment of desirable social outcomes and emotional adjustment, despite exposure to considerable risk (Luthar, 1993; Rutter, 1985). Though there are a variety of ways that risk may be defined (Resnick & Burt, 1996), we use the following definition of ‘risk’: a psychosocial adversity or event that would be considered a stressor to most people and that may hinder normal functioning (Masten, 1994). In order to understand resilient outcomes among children and families in adversity, one must identify protective factors and subsequent protective processes influencing successful outcomes despite specified risks (Luthar, 1993; Rutter, 1985). ‘Protective factors’ refer to often exogenous variables whose presence is associated with desirable outcomes in populations deemed at risk for mental health and other problems (Werner, 1989). The dynamic processes that foster resilient outcomes (in this case psychosocial and developmental outcomes) in youths are defined as ‘protective processes’. Scholars define protective processes as those operating in the family, peer group, school, and community (Benard, 1995) which serve to decrease the likelihood of negative outcomes (Cowan, Cowan, & Schulz, 1996). In this paper, we view resilience as composed of both protective factors and protective processes that lead to positive psychosocial and development outcomes.

We argue that trauma, psychological adjustment, resilience, and the mental health of children in war must be viewed as a dynamic process, rather than as a personal trait. Furthermore, we argue for an understanding of resilience from the perspective of the social ecology - the nurturing physical and emotional environment that includes, and extends beyond, the immediate family to peer, school and community settings, and to cultural and political belief systems (Boothby, Strang, & Wessells, 2006; Earls & Carlson, 2001). War is often characterized by the loss of security, unpredictability and the lack of structure in daily life (Stichick, 2001; Machel, 2001). Essential services and institutions, such as schools and hospitals are often damaged or purposely destroyed. Family and social networks are shattered. For children, war represents a fundamental alteration of the social ecology and infrastructure which supports child development in addition to risk of personal physical endangerment. Restoration of a damaged social ecology is fundamental to improving prevention and rehabilitative interventions for war-affected children.

Ecological model of human development

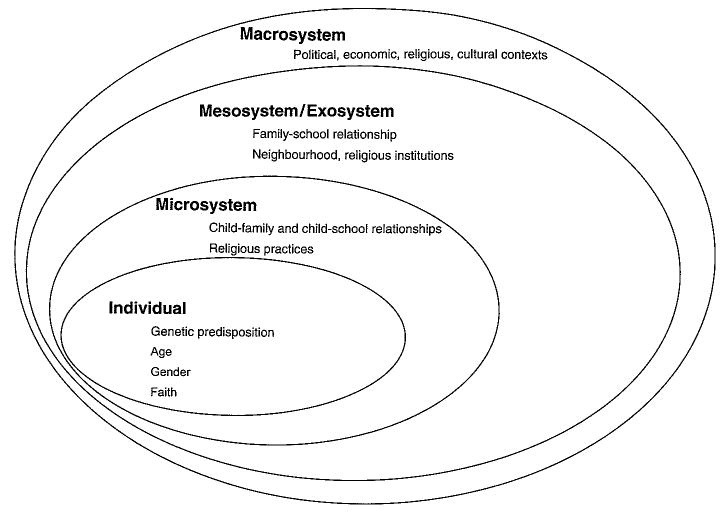

Bronfenbrenner's classic ecological model of child development (1979) provides a central framework for analysing the interrelated settings and relationships involved in the psychosocial impact of armed conflict on children. His theory defines key developmental contexts in terms of microsystems, mesosytems, exosystems and macrosystems.

The first layer of a child's social ecology, the microsystem, involves the interactions between the individual child and the immediate setting, such as the school or home environment where primary relationships are established. The mesosystem concerns the interaction of two or more settings of relevance to the developing child – between the child's family and school settings, or among the family system and the child's extended social network. The exosystem is an extension of the mesosystem and includes societal structures, both formal and informal. This may include government structures, major societal institutions, both economic and cultural, as well as informal concepts like the neighbourhood. The exosystem pertains indirectly to the individual. The macrosystem encompasses the larger cultural context including beliefs, customs and the historical and political aspects of the social ecology. Bronfenbrenner (1979) notes: ‘the availability of supportive settings is, in turn, a function of their existence and frequency in a given culture or subculture’ (p. 7). In this manner, the macrosystem touches all other aspects of the social ecology. Macrosystem influences of culture, politics and history are all reflected in the operation of major institutions at the level of the mesosystem, the community exosystem and even relationships within smaller microsystems.

Bronfenbrenner's framework allows us to consider the role or status of children in their ecological context to assess opportunities and limitations inherent in working on their behalf. In outlining his ecology of child development, Bronfenbrenner (1979) points out that ‘what place or priority’ (p. 515) children and people who work with children have in macrosystems is important for understanding how children – and their caregivers – are treated, and shapes interactions across ecological settings. According to Bronfenbrenner's theory, the ability of parents to care for their children is embedded in and influenced by ‘stresses and supports emanating from other settings’ (1979, p. 7).

In this paper, a social ecological framework is used to take a broad perspective on resilience in children affected by armed conflict. This view looks to capacities and resources in the individual child and their larger social environment, as well as the interaction between them.

The mental health of war-affected children

Research on the mental health consequences of armed conflict for children has grown in recent years (Lustig et al., 2004; Barenbaum et al., 2004; Betancourt & Williams, 2008). In particular, research has documented the many ways in which exposure to war-related traumatic events contributes to subsequent mental health distress, and in some cases, longer-term psychopathology in children and adolescents.

A debate continues about how best to respond to the mental health needs of war-affected children and their families (Stichick, 2001; Summerfield, 2001). This debate is constrained by the fact that the majority of the research on the mental health of war-affected children has focused on risk factors and subsequent psychopathology. Far less research has explored variables or processes associated with resilient outcomes in children. As a result, there are significant gaps in our knowledge about effective responses and factors associated with resilient mental health outcomes in war-affected children. There is a pressing need to examine predictors of resilience in war-affected children across all layers of the social ecology - beyond individual characteristics of resilience to protective factors operating at the family, community and cultural level. Of particular interest to many practitioners and policymakers are those factors which may be modified by outside intervention or policy. Such research would provide an important foundation for improving appropriate responses and interventions (Fergus & Zimmerman, 2005). In order to explore these issues in more detail, we first address the construct of resilience and protective processes in children.

The construct of resilience and protective processes in children

Attention to resilience as a framework for the study of children's mental health in the face of extreme stressors has grown in contrast to more traditional, deficit-based models. Rooted in the early writings of Garmezy (1988), Rutter (1985) and longitudinal studies conducted by Werner and Smith (1982), the child resilience field has now grown to address children's resilient outcomes across many situations of risk (Luthar, 2005).

While there are disagreements about how to define the construct of resilience (Howard, Dryden, & Johnson, 1999; Luthar, Cicchetti, & Becker, 2000; Masten, 2001; Rutter, 1999, 2000), a resilience perspective is useful in the discussion of protective processes in the mental health of children affected by armed conflict. Traditionally, resilience has been conceptualized as an individual trait or unique quality (Block & Block, 1980) that helps an individual child achieve desirable emotional and social functioning despite exposure to considerable adversity (Masten et al., 1991; Rutter, 1985, 2003). In some accounts of children affected by armed conflict, resilience has been described as an individual quality of ‘invulnerable’ children who did well despite the extremely difficult circumstances they faced (Apfel & Simon, 1996).

Today's leading scholars on resilience caution against thinking of resilience merely as an individual quality of certain children (Bartelt, 1994; Benard, 1995; Cowan et al., 1996; Luthar, 1993; Richmond & Beardslee, 1988). Rather, they stress it is more useful to focus on ‘resilient outcomes’ or resilient trajectories in children faced with adversity (Luthar, 1993). This understanding of resilience complements the ecological perspective described above. Protective factors and protective processes operate at all levels of a child's social ecology, from interaction with individual traits to the family and extended social network to the cultural and historical context (Garmezy, 1988; Masten et al., 1999, Masten, 2001).

Luthar et al. (2000) summarize three sets of factors thought to relate to the ‘development of resilience’ in children (p. 544): attributes of the individual child, attributes of a child's family, and characteristics of the larger social environment. All of these factors may be mapped on to a social ecological model of risk and protection for children affected by armed conflict (Figure 1). This model depicts resilience as a process shaped by the interaction between risk and protective factors operating across many layers of a child's social ecology.

Figure 1.

The social ecological model of risk and protection for children affected by armed conflict (adapted from Bronfenbrenner, 1979).

An ecological analysis of research on protective processes for war-affected children

For war-affected children, little is known about what factors contribute to resilient or positive outcomes in the face of war-related stressors such as violence, displacement and loss. However, the present analysis of the available literature on protective factors and protective processes related to the mental health of children affected by armed conflict provides compelling evidence that such processes are at work at each level of the social ecology. An exploration of factors associated with resilient outcomes in war-affected children follows.

Protection and the individual

Research has suggested the protective potential of a range of child characteristics, such as high intelligence, internal locus of control, good coping skills, and an easygoing temperament (Fergusson & Horwood, 2003; Masten & Powell, 2003). Cortes & Buchanan (2007) conducted a narrative analysis of six Colombian child soldiers who did not exhibit trauma-related symptoms after experiencing armed combat. They sought to understand the mechanisms and resources that these ‘resilient children’ used to buffer the effects of war trauma. They identified six themes which indicated a wide repertoire of strengths and resources that seemed to facilitate the ability of these youths to overcome the trauma of war: a sense of agency; social intelligence, empathy, and affect regulation; shared experience, caregiving features, and community connection; a sense of future, hope and growth; a connection to spirituality; and morality.

Religion may serve an important source of cultural identity and a foundation for how both trauma and healing are interpreted. Among war-affected children in Sri Lanka, Fernando (2006) found that resilient orphans identified Buddhist religious practices – meditation, reciting the five precepts of Buddhism, reading character stories of the Buddha, and cultivating understanding about life's circumstances as important for coping with difficulties and promoting well being. In particular, these activities were seen as offering structure and helping the children to make sense of and ultimately accept the traumatic past they had survived. In addition to the mainly individual attributes described, a number of aspects of the environment – a supportive adult, neighbourhood networks, and mentors within the community – were also important in promoting and sustaining resilience. The interaction between individual characteristics and environmental supports provide an important foundation for developing future strengths-based interventions (Cauce, Stewart, Rodriguez, Cochran, & Ginzler, 2003; Gorman-Smith & Tolan, 2003).

Protection and the microsystem: Attachment relationships

Attachment relationships to others (Bowlby, 1969) are critical for helping children cope with difficult circumstances (Rutter, 1985). Landmark longitudinal studies of child development have demonstrated that the existence of a supportive relationship with at least one caring adult outside of a troubled home was associated with better social and emotional outcomes in even the most disadvantaged children (Werner, 1989). A number of studies indicate that social support, social ties, living in caring or ‘connected’ neighbourhoods or schools, and forming and belonging to youth groups are all associated with positive mental health outcomes in children and adolescents (Kliewer, Lepore, Oskin, & Johnson, 1998; Kliewer, Murrelle, Mejia, Torres de, & Angold, 2001; Resnick et al., 1997; Women's Commission for Refugee Women and Children, 2007).

Attention to attachment relationships is critical in understanding how children cope in the face of war-related stressors. Research in this area dates back to the seminal work of Anna Freud and Dorothy Burlingham (1944) who documented the behaviour of children cared for in English nurseries during World War II. In observing children who had not incurred physical injury, but who had been repeatedly exposed wartime bombings and even ‘partly buried in debris’, Freud and Burlingham (1944) noted:

so far as we can notice, there were no signs of traumatic shock to be observed in these children. If these bombing incidents occur when small children are in the care either of their own mother, or a familiar mother substitute, they do not seem to be particularly affected by them. Their experience remains an accident, in line with other accidents of childhood. (p. 21)

Another classic study (Henshaw & Howarth, 1941) of children during the British evacuations of World War II concluded that, for children, evacuation and the subsequent family separation caused more emotional strain than exposure to air raids. Particularly for young children, the process of interpreting and making meaning of frightening situations is characterized by a dynamic interaction whereby the child looks to the reaction of immediate caregivers as a means of interpreting the threat as well as a source of reassurance (Ainsworth, Blehar, Waters, & Wall, 1978; Winnicott, 1965). The ability of the caregiver to comfort the child and help them make meaning of frightening events is critical in the child's process of adjustment. In the end, some theorists have argued, the psychological effects of violence on children may be more dependent on the availability of close, reliable attachment figures to provide support during and following difficult events more than the abject degree of violence witnessed (Garbarino, Dubrow, & Kostelny, 1991).

In a survey of war affected youths in northern Uganda, Annan and Blattman (2006) provide evidence of the integral role of the family in the reintegration of 741 male former child soldiers and their long-term mental health outcomes in northern Uganda. Those who had high family connectedness and social support were more likely to have lower levels of emotional distress and exhibited better social functioning (Annan & Blattman, 2006). Punamaki et al. (2001) expands on the simple assumption that ‘good and loving parenting is beneficial, and rejective and hostile parenting is harmful.’ Of the 86 war-affected children (44 girls, 42 boys) first tested in 1993 during the last and violent months of the Intifada, Punamaki (2001) reinterviewed a subgroup of 64 children in 1996. Punamaki (2001) found that children who perceived only their mothers as highly loving and caring, but not their fathers, exhibited higher levels of post traumatic stress symptoms compared to children who perceived equal loving and caring relationships with both parents.

Social support

A main function of attachment relationships is the social support, love, and care they provide the developing child. Social support is usually defined in terms of its source, structure and function. Sherbourne & Stewart (1991) have outlined three main dimensions of social support: instrumental support (help and assistance to carry out necessary tasks); informational support (information and guidance for an individual to carry out day-to-day activities successfully); and emotional support (caring and emotional comfort provided by others). Researchers have noted the importance of distinguishing between support received from different sources, such as family, peers and significant others in international research because cultural variations in gender roles may result in boys and girls responding differently to stressors (Llabre & Hadi, 1997).

The role of social support for children exposed to war-related trauma may differ according to gender. Llabre & Hadi (1997) observed interactions between social support and gender in their study of 151 Kuwaiti girls and boys exposed to high or low levels of trauma during the Gulf War crisis. They found that, overall, girls reported higher social support compared to boys. Futhermore, boys and girls may have differing responses to social support. Social support moderated the impact of trauma exposure on distress in girls, but not in boys. Kuterovac-Jagodic (2003) found that while higher levels of social support were observed in girls and younger children, poor social support was a main predictor of posttraumatic stress symptoms, particularly those symptoms that persisted months and years after the wartime exposure to trauma.

In a sample of 184 war-affected Chechen adolescents (Betancourt, 2002), measures of children's connectedness to family members, peers and others in the larger community of internally displaced persons (IDP) in Ingushetia were associated with lower average levels of internalizing emotional and behavioural problems. In a study of family stress and coping in the face of war and non-war stressors, Farhood (1999) observed that social support was a significant predictor of psychological health and a main contributor to family adaptation.

Related to the prior findings on caregiver attachment and connection, Kliewer et al. (2001) studied Colombian children coping with violence against family members. They found that higher levels of social support in children exposed to severe violence were associated with reduced risk of internalizing emotional problems. The researchers also observed interactions between social support and both family and individual factors. Exposure to community violence had the strongest emotional impact on children who exhibited low social support and a high degree of social strain. They also observed that children who had a high degree of intrusive thinking (a hallmark symptom of Post Traumatic Stress Disorder, or PTSD) were more likely to exhibit internalizing symptoms such as anxiety, depression, emotional withdrawal and somatic complaints when they had low social support.

A study by Barber (2001) tested an ecological model of Palestinian youth expectations during the Intifada. The study found that social integration in family, education, religion and peer relations significantly moderated the association between Intifada experience and subsequent psychosocial problems.

Of the different forms of social support studied, instrumental support, emotional support and support that fostered self-esteem were correlated with lower average PTSD symptoms over time. In particular, instrumental support demonstrated the strongest association with long-term posttraumatic stress symptoms.

Caregiver mental health

Caregiver mental health may mediate the availability of social support and primary attachment relationships available to the child. As (Elbedour, Bensel, & Bastien, 1993) noted, the influence of family on the mental health of war-affected children often takes two forms: parents and other caregivers or family members can act as a ‘protective shield’ during hardship; or parents can complicate a child's management of the war stress when they themselves manage stress poorly. A child's adjustment to wartime stressors is shaped not only by their individual qualities, but also by characteristics of the family system. In this manner, caregiver mental health can serve as an important predictor of child mental health (Dybdahl, 2001; Miller, 1996).

A number of studies have documented a relationship between the mental health of war-affected children and their parents. In a study of Central American children, Locke and colleagues (1996) observed that the effects of war on children's mental health were mediated by maternal mental health. Overall, the researchers observed very low rates of PTSD among children who had been exposed to severe traumatic events. However, for those children who did exhibit PTSD symptoms, the mother's level of posttraumatic stress symptoms was a strong predictor of PTSD symptoms in the children. In an intervention study with Bosnian refugees, a mental health intervention targeting mothers was demonstrated to have direct improvements on the mental health of mothers and indirect effects on the physical and emotional health of their children (Dybdahl, 2001). Over the six months of intervention, children of participants demonstrated better weight gain and lower reports of emotional and behavioural problems compared to the children of mothers receiving health services alone.

Protection and the community mesosystem: Child care institutions and schools

Refugee families offer an example of a war-affected population in which the mesosystemic context of child development becomes dramatically altered by war. For refugee children and families, the mesosystem refers to relations within families and their interrelationship with the larger community system. Refugee families often experience ‘ecological transitions’ (Bronfenbrenner, 1979), or shifts in settings and roles. For children and adolescents, displacement and the often powerless experience of being a ‘refugee’ or ‘displaced person’ must be negotiated along with the more routine identity struggles of maturation and identity formation (Betancourt, 2005). Likewise, even the most loving and committed of caregivers may find the nature and quality of their interactions with their children dramatically altered by the tasks and shifts in roles necessary for surviving in a war zone (Elbedour et al., 1993; Betancourt, 2005). This broader ecological view is of particular value for understanding the multiple stressors and sources of support negotiated by caregivers attempting to care for their children during times of insecurity.

The quality and nature of relationships in more distal settings such as schools and neighbourhoods are also implicated in the mental health and adjustment of war-affected youth, but remain under studied. In preliminary research on war-affected children, there is evidence to suggest that childcare facilities characterized by caring relationships between staff and children have been associated with positive mental health outcomes. Wolff & Fesseha (1998) compared measures of adjustment among comparable groups of Eritrean orphans in two institutional care settings. Although the institutions were similar in staffing ratios and structure, management styles differed between the two institutions. In one site, staff and children focused on meeting children's basic needs, but remained emotionally aloof. The other site encouraged staff to take an active role in decisions affecting the children and to develop close relationships with children. The researchers observed significantly lower levels of distress among children in the site where close caring relationships between staff and the children in care were encouraged.

In discussing ecological approaches to interventions for children affected by war, Elbedour et al. (1993) emphasized the importance of schools in ‘mitigating trauma's effects’. In displacement and refugee crises, the early provision of educational activities has been argued as an important means of restoring predictability and social supports to children (Aguilar & Retamal, 1998). Generally, emergency education programming aims to reach children and adolescents from the outset of conflict throughout the period of displacement (Aguilar & Retamal, 1998; Betancourt, 2005). Emergency education comprises a range of programmatic interventions often beginning with informal education activities that can be quickly established with limited resources. With time, programming is developed to include more formal schooling activities that require extended investment in training, community involvement, and coordination with local authorities.

There are a number of theorized psychosocial mechanisms by which emergency education responses during complex humanitarian emergencies might operate to improve social and mental health outcomes in young people (Betancourt, 2005). For example, the restoration of opportunities to study or develop vocational skills can provide children and youths with a sense of predictability and security amidst the chaos of displacement, traumatic events and loss. The opportunity for children to return to their studies may also instill a sense of hope and develop the tools necessary for future success. In displacement situations, education programmes can serve a protective function as children are monitored in a more centralized manner and systematic mechanisms for screening their mental and physical health may be established. Finally, participatory education programmes may foster enriched social networks and social support between children, staff and other adults in the community by engaging beneficiaries in collective action on behalf of children.

The exosystem is an extension of the mesosystem, and indirectly influences the day-to-day lives of individuals. For refugees, the exosystem may refer to the major agencies providing aid, as well as the governments of their home and host countries who play an important goal in determining the conditions in which they live and the aid they receive.

Religious institutions are also an important part of the community exosystem. Fernando (2006) found that rituals and religious practices followed by war-affected children in Sri Lankan orphanages provided a sense of belonging, which promoted integration into the community. The children benefited from the structure and routine offered by rituals with Buddhist practice. Since these activities were conducted within the orphanage community with peers, caregivers, teachers, and monks, these activities extended the relationships established in the development of early faith practices to broaden young people's connections in the community as well. Apart from educational and religious institutions, access to healthcare, shelter, good nutrition, mental health services, social services and legal services are all important exosystem forces involved in promoting well-being of war-affected populations (Aguilar & Retamal, 1998; Betancourt & Williams, 2008).

Protection and the macrosystem: The cultural, historical, and political context of war

Considering the cultural, political, religious and historical roots of potential protective processes in the mental health of war-affected children is important to the socio-ecological view. For instance, political dynamics at the macrosystem level can have direct bearing on the funding allotted for services in refugee camps and the provision of military protections to civilians during conflict. By shaping demands placed on families and communities to secure basic needs for their children and keep them safe, macrosystem dynamics exert influence on the functioning of community exosystems, mesosystems and family microsystems.

The cultural and historical meaning given to war-related experiences has been linked to its psychosocial impact: while political ideologies may strengthen, or buffer (Punamaki, 1996) individuals in a struggle for survival, such beliefs may also perpetuate group tensions and foment ethic divisions and violence (Garbarino et al., 1991). Across different war-affected populations, culture and cultural meaning play a defining role in determining what constitutes risk and what constitutes protection (Rousseau, Taher, Gagne, & Bibeau, 1998). In situations of armed conflict, dynamics at the macrosystem level may be at the very root of the conflict itself. Political ideologies, economic stressors and religious tensions between ethnic groups have historically precipitated many conflicts and subsequent forced migration (de Waal, 2007). These ideologies may also underlie the attitudes of the host country as well as service organizations that care for displaced and war-affected children.

Cultural beliefs and practices in mental health

In recognizing the role of culture in healing and coping with the hardships of war, several examples exist of programmes that build on community strengths and cultural norms. These programmes aim not to pathologize children. Rather, they build upon strengths inherent in cultural beliefs and community processes that traditionally protect and support children. For example, a programme in Sierra Leone has sought support for community-led traditional cleansing ceremonies as a part of a mental health intervention. These Bundu initiation ceremonies are intended to rid young women of noro or spiritual pollution and bad luck that is thought to affect female survivors of war-related rape. Such ceremonies have been found to facilitate greater self-esteem and community acceptance (Stark, 2006). In the Khmer refugee camps in Thailand, health services were designed to integrate traditional healers and traditional medicines into the care provided. (Ressler, Tortocini, & Marcelino, 1993) found this traditional support to be particularly valuable for individuals complaining of ‘sadness, anxiety, fatigue and insomnia’. This treatment, which incorporates cultural practices, derives its strength from the familiarity and comfort from practices long known to the child, family and community. Intervention based on traditional practices may be more culturally syntonic and engaging than treatment models imported to war-affected regions from the west (Summerfield, 1998; IASC, 2007).

Overall, this review indicates the importance of a socio-ecological model, as individuals' characteristics do not act as sole predictors of resilient outcomes. Individual characteristics are channelled through environmental and psychological mediators (Punamaki et al., 2001). These environmental mediators include characteristics of family and peer relationships (Microsystems), the availability of supports and resources in the major settings and institutions of the mesosystem and exosystem levels and the dynamics operant at the larger macrosystem level (Basic Science Behavioral Task Force, 1996; Freitas & Downey, 1998; IASC, 2007).

Discussion

Attention to risk factors and protective processes operating in the mental health of war-affected children is only a first step in broadening responses available to the policy and programming community. A resilience perspective is not an antidote for the true horrors of war. Discussing resilience as a relevant construct in understanding the mental health of children in war must be pursued with caution (Benard, 1993; Dawes, Tredoux, & Feinstein, 1989; Howard et al., 1999; Luthar et al., 2000). In the movement towards efforts to boost resilience among war-affected youths, Benard (1993) has cautioned against ‘quick fix’ approaches. Dawes et al. (1989) caution that researchers should not be seduced by the optimism of resilience and miss the undeniable, often long-term mental health consequences of wartime exposures on child mental health. Programmes to enhance protective factors should not supplant targeted clinical programmes intended to help severely traumatized children exhibiting persistent mental health symptoms and functional impairment (Betancourt & Williams, 2008). Indeed, the orientation of many early resilience theorists and researchers towards identifying traits in individual children seen as ‘invulnerables’ was deserving of criticism. In this light, a resilience perspective offers one way to think about building on naturally occurring strengths in prevention and intervention programmes, but it should not be used to minimize the gravity of war for children and families or limit the scope of services.

Implications for policy and mental health intervention

The studies reviewed here indicate several potential sources of protection and support available to youths in their family, school, and community environments, as well as within their political, economic, and cultural contexts. This integrative, ecological approach can help inform policy and mental health intervention models. Funding informed by such a perspective could help restore child-friendly schools, build family and community participation in existing programmes, and ensure that caregivers, teachers and community mentors return to the care and protection of children (Earls & Carlson, 2001; Betancourt, 2005). Subsequently, interventions may address screening and treatment for children who require greater attention to emotional or behavioural problems and functional impairment (Bolton & Betancourt, 2004). At the macrosystem level, positive youth involvement in civil society may challenge dangerous and divisive political ideologies.

Ideally, both risk and resilience will serve as complementary and equally necessary concepts in the scientific investigation of the mental health of children affected by armed conflict. By filling gaps in the available knowledge about protective processes associated with resilient mental health outcomes in war-affected children we can make great strides in designing better policy and interventions. Rather than focusing solely on deficits or psychopathology, we consider war-affected children and their families from a perspective that emphasizes strengths and coping. A handful of intervention studies conducted in recent years are beginning to detail how targeted individual or group intervention might improve individual level coping skills in war-affected youths (Betancourt & Williams, 2008). A number of interventions, particularly when delivered in groups, may also serve to invigorate exogenous protective processes by bolstering social supports and connectedness among war-affected youths and their caregivers, peers and larger community (Betancourt & Williams, 2008; IASC, 2007). The findings of the analysis presented here, however, underscore the importance of designing programmes that focus beyond the individual child. The data suggest that improving opportunities for children to deepen connections to family, peers, teachers and members of the larger community might provide young people with important resources to help them weather the distress associated with war and displacement (Betancourt, 2005; Elbedour et al., 1993; IASC, 2007; Stichick, 2001).

Implications for future research

As necessitated by an ecological approach, future research on protective processes impacting the mental health of children in war must explore contextual factors across the family, community and societal levels (Boyden & de Berry, 2004; Chatty & Lewando Hunt, 2001; Earls & Carlson, 2001; Maksoud & Aber, 1996; Stichick, 2001). Future research should also take account of children's own understanding of the central concepts of risk and resilience which may differ from those of the adult researchers (Howard et al., 1999; Boyden & de Berry, 2004).

This review of the available research indicates the primacy of family relationships in the mental health of children. At the family or microsystem level, future studies of family support and children's mental health in war-affected populations could be strengthened by collecting data on qualitative aspects of family functioning to help clarify the mechanisms by which attachment and family support operate in these settings. For instance, family support would be better understood if it could be disentangled from other aspects of family functioning, such as parental mental health, loss or separation from close family members, parenting styles, caregiver trauma exposure, and family conflict. Furthermore, local practices such as traditional cleansing ceremonies, and expressive or creative interventions such as dance, art and drama are worthy of systematic investigation (Stark, 2006; Stepakoff et al., 2006; Rousseau, Drapeau, & Rahimi, 2003).

For children whose immediate needs are not met by culturally and contextually-appropriate, broad-based, psychosocial interventions, the efficacy of adapted evidence-based treatment models from other settings should be considered; For instance, recent research in northern Uganda demonstrated that group interpersonal therapy, an adapted version of an evidence-based treatment for depression (Verdeli et al., 2003) was effective for the treatment of locally-described depression symptoms, particularly in adolescent girls (Bolton et al., 2007).

Important research on community and institutional aspects of the social ecology and their relationship to child adjustment remains. Research examining variables of community functioning such as collective trust and social cohesion remains to be developed in war-affected populations, but is emerging in the context of other large-scale crises, such as the HIV/AIDS pandemic (Earls, 2008). Participatory approaches involving youths in the transformation of community life hold a great deal of promise. Many emergency education programmes prioritize the involvement of youth beneficiaries, their families, and the larger community in the development of programmes. Such “empowered collaboration” is thought both to foster a sense of ownership of the programme among beneficiaries and to recreate a sense of belonging (Fullilove, 1998). In future studies, objective measures of community functioning, such as independent assessments of trust and cohesion at the community level and measures of the degree of actual participation and sense of ownership by beneficiaries in programmes, would provide insight into the theory behind popular intervention models.

Future research exploring the benefits of social support and attachment relationships in the mental health of war-affected populations would be improved by considering social processes operating at the peer, family, and community level. In understanding protective processes in the lives of war-affected children, the ecological framework helps build multiple points of intervention in a manner that is holistic, systematic and responsive to the complex nature of war-related stressors and subsequent adjustment. Using the ecological framework, future research and programmes can more effectively combat the consequences of war on the lives of children and families.

Footnotes

Declaration of interest: The authors report no conflicts of interest. The authors alone are responsible for the content and writing of the paper.

References

- Aguilar P, Retamal G. Rapid educational response in complex emergencies: A discussion document. Geneva, Switzerland: International Bureau of Education; 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Ainsworth MDS, Blehar MC, Waters E, Wall S. Patterns of attachment: A psychological study of the strange situation. Hillsdale, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates; 1978. [Google Scholar]

- Annan J, Blattman C. The psychological resilience of youth in northern Uganda: Survey of War Affected Youth, Research Brief 2. [February 6, 2008];2006 Available at www.sway-uganda.org/SWAY.RB2.pdf.

- Apfel RJ, Simon B. Psychosocial interventions for children of war: The value of a model of resiliency. Medicine and Global Survival. 1996;3:A2. [Google Scholar]

- Barber BK. Political violence, social integration, and youth functioning: Palestinian youth from the Intifada. Journal of Community Psychology. 2001;29(3):259–280. [Google Scholar]

- Barenbaum J, Ruchkin V, Schwab-Stone M. The psychosocial aspects of children exposed to war: Practice and policy initiatives. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry. 2004;45(1):41–62. doi: 10.1046/j.0021-9630.2003.00304.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bartelt D. On resilience: Questions of validity. In: Wang MC, Gordon EW, editors. Educational resilience in inner-city America: Challenges and prospects. Hillsdale, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates; 1994. [Google Scholar]

- Basic Science Behavioral Task Force. Basic behavioral science research for mental health: Vulnerability and resilience. American Psychologist. 1996;51:22–28. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bayer CP, Klasen F, Adam H. Association of trauma and PTSD symptoms with openness to reconciliation and feelings of revenge among former Ugandan and Congolese child soldiers. Journal of the American Medical Association. 2007;298:55–559. doi: 10.1001/jama.298.5.555. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Benard B. Resiliency requires changing hearts and minds. Western Center News. 1993;6(2):27–29. [Google Scholar]

- Benard B. ERIC Digest, EDO-PS-95-9. Urbana, IL: University of Illinois; 1995. Fostering resilience in children. [Google Scholar]

- Betancourt T. Stressors, supports and the social ecology of displacement: Psychosocial dimensions of an emergency education program for Chechen adolescents displaced in Ingushetia, Russia. Culture, Medicine & Psychiatry. 2005;29(3):309–340. doi: 10.1007/s11013-005-9170-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Betancourt TS, Williams T. Building an evidence base on mental health interventions for children affected by armed conflict. International Journal of Mental Health, Psychosocial Work and Counseling in Areas of Armed Conflict. 2008;6(1):39–56. doi: 10.1097/WTF.0b013e3282f761ff. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Block JH, Block J. The role of ego-control and ego resiliency in the organization of behaviour. In: Collins WA, editor. Minnesota Symposium on Child Psychology. Vol. 13. Hillsdale, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates; 1980. pp. 39–101. [Google Scholar]

- Bolton P, Betancourt TS. Mental Health in Postwar Afghanistan. Journal of the American Medical Association. 2004;292:626–628. doi: 10.1001/jama.292.5.626. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bolton P, Bass J, Betancourt TS, Speelman L, Onyango G, Clougherty K, et al. Interventions for depression symptoms among war-affected adolescents in northern Uganda: A randomized controlled trial. Journal of the American Medical Association. 2007;298(5):519–527. doi: 10.1001/jama.298.5.519. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boothby N, Strang A, Wessells M. A world turned upside down: Social ecological approaches to children in war zones. Bloomfield, CT: Kumarian Press; 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Bowlby J. Attachment and loss. Vol. 1. New York: Basic Books; 1969. [Google Scholar]

- Boyden J, De Berry J, editors. Children and youth on the front line: Ethonography, armed conflict and displacement. New York: Berghahn Books; 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Bronfenbrenner U. The ecology of human development. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press; 1979. [Google Scholar]

- Cauce AM, Stewart A, Rodriguez MD, Cochran B, Ginzler J. Overcoming the odds? Adolescent development in the context of urban poverty. In: Luthar SS, editor. Resilience and vulnerability: Adaptation in the context of childhood adversities. New York: Cambridge University Press; 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Chatty D, Lewando Hunt G. Lessons Learned Report: Children and Adolescents in Palestinian Households: Living with the Effects of Prolonged Conflict and Forced Migration. Oxford: Refugee Studies Centre; 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Cicchetti D, Garmezy N. Prospects and promises in the study of resilience. Development and Psychopathology. 1993;5(4):497. [Google Scholar]

- Cortes L, Buchanan MJ. The experience of Colombian child soldiers from a resilience perspective. International Journal for the Advancement of Counselling. 2007;29:43–55. [Google Scholar]

- Cowan PA, Cowan CP, Schulz MS. Thinking about risk and resilience in families. In: Hetherington EM, Blechman EA, editors. Stress, coping, and resiliency in children and families. Mahwah, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates; 1996. [Google Scholar]

- Dawes A, Tredoux C, Feinstein A. Political violence in South Africa: Some effects on children of the violent destruction of their community. International Journal of Mental Health. 1989;18:16–43. [Google Scholar]

- de Waal A, editor. War in Darfur and the search for peace. Cambridge, MA: Global Equity Initiative, Harvard University; 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Dybdahl R. Children and mothers in war: An outcome study of a psychosocial intervention program. Child Development. 2001;72(4):1214–1230. doi: 10.1111/1467-8624.00343. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Earls F, Carlson M. The social ecology of child health and well-being. Annual Review of Public Health. 2001;22:143–66. doi: 10.1146/annurev.publhealth.22.1.143. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Earls F. The promotion of child mental health in the context of a generalized epidemic of HIV/AIDS: Results for a cluster randomized trial in Tanzania. Seminar, Psychiatric Epidemiology Series; February 13, 2008.Boston, MA: Harvard School of Public Health; 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Elbedour S, Bensel RT, Bastien DT. Ecological integrated model of children of war: Individual and social psychology. Child Abuse & Neglect. 1993;17:805–819. doi: 10.1016/s0145-2134(08)80011-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Farhood L. Testing a model of family stress and coping based on war and non-war stressors, family resources and coping among Lebanese families. Archives of Psychiatric Nursing. 1999;13(4):192–203. doi: 10.1016/s0883-9417(99)80005-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fergus S, Zimmerman MA. Adolescent resilience: A framework for understanding healthy development in the face of risk. Annual Review of Public Health. 2005;26:399–419. doi: 10.1146/annurev.publhealth.26.021304.144357. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fergusson DM, Horwood LJ. Resilience to childhood adversity: Results of a 21-year study. In: Haggerty RJ, Sherrod LR, Garmezy N, Rutter M, editors. Stress, risk and resilience in children and adolescents: Processes, mechanisms and intervention. New York: Cambridge University Press; 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Fernando C. PhD dissertation. University of Toronto; 2006. Children of war in Sri Lanka: Promoting resilience through faith development. [Google Scholar]

- Freitas AL, Downey G. Resiliency: A dynamic perspective. International Journal of Behavioral Development. 1998;22:263–285. [Google Scholar]

- Freud A, Burlingham D. War and children. second. New York: Ernst Willard; 1944. [Google Scholar]

- Fullilove MT. Promoting social cohesion to improve health. Journal of the American Medical Women's Association. 1998;53(2):72–76. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Garbarino J, Dubrow N, Kostelny K. What children can tell us about living in danger. American Psychologist. 1991;46:376–383. doi: 10.1037//0003-066x.46.4.376. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Garmezy N. Stressors of childhood. In: Garmezy N, Rutter N, editors. Stress, coping, and development in children. Baltimore: The Johns Hopkins University Press; 1988. pp. 43–84. [Google Scholar]

- Gordon EW, Song LD. Variations in the experience. In: Wang MC, Gordon EW, editors. Educational resilience in inner-city America: Challenges and prospects. Hillsdale, NJ, England: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates, Inc.; 1994. pp. 27–43. [Google Scholar]

- Gorman-Smith D, Tolan PH. Positive adaptation among youth exposed to community violence. In: Haggerty RJ, Sherrod LR, Garmezy N, Rutter M, editors. Stress, risk and resilience in children and adolescents: Processes, mechanisms and intervention. New York: Cambridge University Press; 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Henshaw EM, Howarth HE. Observed effects of wartime condition of children. Mental Health. 1941;2:93–101. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Howard S, Dryden J, Johnson B. Childhood resilience: Review and critique of literature. Oxford Review of Education. 1999;25(3):307–323. [Google Scholar]

- IASC (Inter-Agency Standing Committee) IASC guidelines on mental health and psychosocial support in emergency settings. Geneva: IASC; 2007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaufman J, Cook A, Arny L, Jones B, Pittinsky T. Problems defining resiliency: Illustrations from the study of maltreated children. Development and Psychopathology. 1994;6:215–229. [Google Scholar]

- Kliewer W, Lepore SJ, Oskin D, Johnson PD. The role of social and cognitive processes in children's adjustment to community violence. Journal of Consulting & Clinical Psychology. 1998;66:199–209. doi: 10.1037//0022-006x.66.1.199. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kliewer W, Murrelle L, Mejia R, Torres de Y, Angold A. Exposure to violence against a family member and internalizing symptoms in Colombian adolescents. Journal of Consulting & Clinical Psychology. 2001;69(6):971–982. doi: 10.1037/0022-006X.69.6.971. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kuterovac-Jagodic G. Posttraumatic stress symptoms in Croatian children exposed to war: A prospective study. Journal of Clinical Psychology. 2003;59(1):9–25. doi: 10.1002/jclp.10114. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Llabre MM, Hadi F. Social support and psychological distress in Kuwaiti boys and girls exposed to the gulf crisis. Journal of Clinical Child Psychology. 1997;26(3):247–255. doi: 10.1207/s15374424jccp2603_3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Locke CJ, Southwick K, McCloskey LA, Fernandez-Esquer ME. The psychological and medical sequelae of war in Central American refugee mothers and children. Archives of Pediatric Adolescent Medicine. 1996;150:822–828. doi: 10.1001/archpedi.1996.02170330048008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lustig SL, Kia-Keating M, Knight WG, Geltman P, Ellis H, Kinzie JD, et al. Review of child and adolescent refugee mental health. Journal of the American Academy of Child & Adolescent Psychiatry. 2004;43(1):24–36. doi: 10.1097/00004583-200401000-00012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Luthar S. Annotation: Methodological and conceptual issues in research on childhood resilience. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry. 1993;34(4):441–453. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7610.1993.tb01030.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Luthar S, Cushing G. Measurement issues in the empirical study of resilience: An overview. In: Glantz M, Johnson JL, editors. Resilience and development: Positive life adaptations. New York: Plenum; 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Luthar S, Cicchetti D, Becker B. The construct of resilience: A critical evaluation and guidelines for future work. Child Development. 2000;71(3):543–562. doi: 10.1111/1467-8624.00164. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Luthar S. Resilience in development: A synthesis of research across five decades. In: Cicchetti D, Cohen DJ, editors. Developmental psychopathology: Risk, disorder, and adaptation. second. Vol. 3. New York: Wiley; 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Machel G. Report of the expert of the Secretary-General of the United Nations. New York: United Nations; 1996. Impact of armed conflict on children. [Google Scholar]

- Machel G. The impact of war on children. London: Hurst & Company; 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Macksoud MS, Aber JL. The War Experiences and Psychosocial Development of Children in Lebanon. Child Development. 1996;67(1):70–88. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Masten AS, Best KM, Garmezy N. Resilience and development: Contributions from the study of children who overcome adversity. Development and Psychopathology. 1991;2:425–444. [Google Scholar]

- Masten AS. Resilience in individual development: Successful adaptation despite risk and adversity. In: Wang MC, Gordon EW, editors. Educational resilience in inner-city America: Challenges and prospects. Hillsdale, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates; 1994. [Google Scholar]

- Masten AS, Hubbard JJ, Gest SD, Tellegan A, Garmezy N, Ramirez M. Competence in the context of adversity: Pathways to resilience and maladaptation from childhood to late adolescence. Development and Psychopathology. 1999;11:143–169. doi: 10.1017/s0954579499001996. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Masten AS. Ordinary magic: Resilience processes in development. American Psychologist. 2001;56(3):227–238. doi: 10.1037//0003-066x.56.3.227. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Masten AS, Powell JL. A resilience framework for research, policy, and practice. In: Haggerty RJ, Sherrod LR, Garmezy N, Rutter M, editors. Stress, risk and resilience in children and adolescents: Processes, mechanisms and intervention. New York: Cambridge University Press; 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Miller KE. The effects of state terrorism and exile on indigenous Guatemalan refugee children: A mental health assessment and an analysis of children's narratives. Child Development. 1996;67:89–106. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Punamaki RL. Can ideological commitment protect children's psychosocial well-being in situations of political violence? Child Development. 1996;67(1):55–69. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Punamaki RL. Resiliency factors predicting psychological adjustment after political violence among Palestinian children. International Journal of Behavioral Development. 2001;25(3):256–267. [Google Scholar]

- Punamaki RL, Qouta S, El-Sarraj E. Resiliency factors predicting psychological adjustment after political violence among Palestinian children. International Journal of Bhavioral Development. 2001;25(3):256–267. [Google Scholar]

- Resnick G, Burt MK. Youth at risk: Definitions and implications for service delivery. American Journal of Orthopsychiatry. 1996;66:172–188. doi: 10.1037/h0080169. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Resnick MD, Bearman PS, Blum RW, Bauman KE, Harris KM, Jones J, et al. Protecting adolescents from harm. Findings from the National Longitudinal Study on Adolescent Health. Journal of the American Medical Association. 1997;278(10):823–832. doi: 10.1001/jama.278.10.823. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ressler E, Tortocini J, Marcelino A. Children in war: A guide to the provision of services. New York: United Nations Children's Fund; 1993. [Google Scholar]

- Richmond JG, Beardslee WR. Resiliency: Research and practical implications for pediatricians. Development and Behavioral Pediatrics. 1988;9:157–163. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Robinson JP, Young J. Listening to youth: The experiences of young people in Northern Uganda. New York: Women's Commission for Refugee Women and Children; 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Rousseau C, Taher MS, Gagne M, Bibeau G. Resilience in unaccompanied minors from the north of Somalia. Psychoanalytic Review. 1998;85(4):615–637. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rousseau C, Drapeau A, Rahimi S. The complexity of trauma response: A four-year follow-up of adolescent Cambodian refugees. Child Abuse & Neglect. 2003;27:1277–1290. doi: 10.1016/j.chiabu.2003.07.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rutter M. Resilience in the face of adversity: Protective factors and resistance to psychiatric disorder. British Journal of Psychiatry. 1985;147:598–611. doi: 10.1192/bjp.147.6.598. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rutter M. Psychosocial resilience and protective mechanisms. American Journal of Orthopsychiatry. 1987;57:316–331. doi: 10.1111/j.1939-0025.1987.tb03541.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rutter M. Psychosocial resilience and protective mechanisms. In: Rolf J, Masten A, Cicchetti D, Neucterlein K, Weintraub S, editors. Risk and protective factors in the development of psychopathology. New York: Cambridge University Press; 1990. [Google Scholar]

- Rutter M. Resilience concepts and findings: Implications for family therapy. Journal of Family Therapy. 1999;21:119–144. [Google Scholar]

- Rutter M. Resilience reconsidered: Conceptual considerations, empirical findings, and policy implications. In: Shonkoff JP, Meisels SJ, editors. Handbook of early childhood intervention. second. New York: Cambridge University Press; 2000. pp. 651–682. [Google Scholar]

- Rutter M. Genetic influences on risk and protection: implications for understanding resilience. In: Luthar SS, editor. Resilience and vulnerability: Adaptation in the context of childhood adversities. New York: Cambridge University Press; 2003. pp. 489–509. [Google Scholar]

- Sherbourne CD, Stewart AL. The MOS social support survey. Social Science & Medicine. 1991;32(6):705–714. doi: 10.1016/0277-9536(91)90150-b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stark L. Cleansing the wounds of war, an examination of traditional healing, psychosocial health and reintegration in Sierra Leone. Intervention. 2006;4(3):206–218. [Google Scholar]

- Stepakoff S, Hubbard J, Katoh M, Falk E, Mikulu JB, Nkhoma P, et al. Trauma healing in refugee camps in Guinea: A psychosocial program for Liberian and Sierra Leonean survivors of torture and war. American Psychologist. 2006;61(8):921–932. doi: 10.1037/0003-066X.61.8.921. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stichick T. The psychosocial impact of armed conflict on children: Rethinking traditional paradigms in research and intervention. Child and Adolescent Psychiatric Clinics of North America. 2001;10(4):797–814. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stichick T, Bruderlein C. Children facing insecurity: New strategies for survival in a global era; Policy paper produced for the Canadian Department of Foreign Affairs and International Trade, The Human Security Network, 3rd Ministerial Meeting; Petra, Jordan. 11–12 May.2001. [Google Scholar]

- Stichick Betancourt T. The IRC's emergency education and recreation for Chechen displaced youth in Ingushetia. Forced Migration Review. 2002;15:28–30. [Google Scholar]

- Stouthamer-Loeber M, Loeber R, Farrington DP, Zhang Q, van Kammen W, Maguin E. The double edge of protective and risk factors delinquency: Interrelations and developmental patterns. Development and Psychopathology. 1993;5:683–701. [Google Scholar]

- Summerfield D. Protecting children from armed conflict: Children affected by war must not be stigmatised as permanently damaged. British Journal of Medicine. 1998;317(7167):1249. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Summerfield D. The invention of post-traumatic stress disorder and the social usefulness of a psychiatric category. British Journal of Medicine. 2001;322:95–98. doi: 10.1136/bmj.322.7278.95. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tarter RE, Vanyukov M. Re-visiting the Validity of the Construct of Resilience. In: Glantz MD, Johnson JL, editors. Resilience and Development: Positive Life Adapations. New York: Kluwer Academic/Plenum Publishers; 1999. pp. 85–100. [Google Scholar]

- Tolan PT. How resilient is the concept of resilience? The Community Psychologist. 1996;29:12–15. [Google Scholar]

- UNICEF. State of the world's children 2006. New York: UNICEF; 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Verdeli H, Clougherty K, Bolton P, Speelman L, Lincoln N, Bass J, et al. Adapting group interpersonal psychotherapy for a developing country: Experience in rural Uganda. World Psychiatry. 2003;2(2):114–120. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vinck P, Pham PN, Stover E, Weinstein HM. Exposure to war crimes and implications for peace building in northern Uganda. Journal of the American Medical Association. 2007;298:543–554. doi: 10.1001/jama.298.5.543. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Werner EE, Smith RS. Vulnerable but invincible: A longitudinal study of resilient children and youth. New York: McGraw-Hill; 1982. [Google Scholar]

- Werner EE. High-risk children in young adulthood: A longitudinal study from birth to 32 years. American Journal of Orthopsychiatry. 1989;59(1):72–81. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Winnicott D. The maturational processes and the facilitating environment. New York: International Universities Press; 1965. [Google Scholar]

- Wolff PH, Fesseha G. The orphans of Eritrea: Are orphanages part of the problem or part of the solution? American Journal of Psychiatry. 1998;155(10):1319. doi: 10.1176/ajp.155.10.1319. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]