Introduction

Human rhinoviruses (HRV), which comprise a genus within the family Picornaviridae, are the major culprits of cold infections in humans. While generally resulting in an upper respiratory illness that commonly runs its course in 7–10 days in healthy individuals, the infection can cause severe lower respiratory tract symptoms in certain subgroups, including the very young, the elderly, and individuals with chronic respiratory disease such as asthma, COPD, and cystic fibrosis. In order to study HRV infection in vivo and develop new options for treatment, new models to study mechanisms of HRV-induced disease are needed.

Several groups have developed mouse models of HRV infection, to enable the use of a wide variety of molecular tools and genetic manipulation that are available with this species (Yin and Lomax, 1986; Bartlett, et al., 2008; Newcomb, et al., 2008). Although these models have not been fully established, an important observation is that minor group HRV, which use receptors in the low density lipoprotein receptor (LDLr) family, can bind to and replicate within mouse epithelial cells and epithelial cell lines (Yin and Lomax, 1983; Lomax and Yin, 1989; Harris and Racaniello, 2003; Bartlett, et al., 2008; Newcomb, et al., 2008).

In vitro models using primary cultures of airway epithelial cells have proven valuable, and techniques for reliably producing healthy, high quality, differentiated cultures with mucociliary phenotypes at the air-liquid interface are available for several species, including mice (Davidson et al., 2000; You, et al., 2002). Conducting experiments of HRV growth in epithelial cells from mice with genetic manipulations to innate antiviral pathways is likely to produce new insights into the pathogenesis of infections with HRV and other respiratory viruses. For this type of experimental design, it is advantageous to serially culture undifferentiated cells obtained from specific strains of mice, to maximize the information that can be obtained from a limited number of mice. In fact, cells of some species have proven amenable to serial subculture, and specific media tailored to support them are often available on the market, as is the case for cells of human (BEGM; Lonza, Walkersville, MD) or rat (PCT Airway Epithelium Medium Complete; Millipore, Temecula, CA) origin. Unfortunately, the serial subculture of mouse cells has not yet been established.

In this paper, we describe a method to serially culture mouse airway epithelial cells. Furthermore, these cells have proven useful in developing a mouse model of epithelial cell infection with the minor group strain HRV-1A. Using monolayers of serially passaged cells, these experiments demonstrate replication of viral RNA, de novo synthesis of viral proteins, and production of infectious virus.

Materials & Methods

Isolation and culture of primary airway epithelial cells from mice

Fifteen female, 7.5 week old C57BL/6N mice (supplied by National Cancer Institute), whose care was in accordance with institutional guidelines, were sacrificed using an overdose of pentobarbitol. Trachea were aseptically removed and collected in a tube containing DMEM/F12 (Invitrogen #11330, Carlsbad, CA) with penicillin (100U/mL) and streptomycin (0.1 mg/mL). Tube contents were poured into a sterile P100 culture dish, and then trachea were transferred to the cover of a sterile P100 culture dish in a small amount of medium. Each trachea was held between the tips of a sterile forceps and sliced longitudinally with a sterile scalpel, for better exposure to enzyme solution. Trachea were then transferred to a tube containing about 20mL of calcium and magnesium-free MEM with 1.4mg/mL pronase (Roche Applied Sciences, Indianapolis, IN) and 0.1mg/mL deoxyribonuclease I (Sigma #DN25, St. Louis, MO) and placed at 4°C for overnight incubation.

The next day, FCS (Sigma #F6178) was added to 10% to stop the action of the protease, and the tube was inverted several times to mix well and dislodge cells. Trachea were discarded, and the cell-containing supernatant was transferred to a new 50 mL tube and centrifuged 10 minutes at 1000 rpm, 4°C. The cell pellet was resuspended in 10 mL complete medium (DMEM/F12 with penicillin and streptomycin, supplemented with 5% FCS, insulin [120U/L], and 1X non-essential amino acids) and transferred to an uncoated P100 culture plate. Cells were incubated at 37° C, 5% CO2, for 3 hours to remove fibroblasts through differential adherence. Epithelial cells were then collected into a new 50 mL tube and centrifuged again, after which pellet was resuspended in 10 mL DMEM/F12 to rinse cells and allow them to be counted. The cell yield from 15 trachea generally ranged from 1.2–2 × 106 cells. The pellet was resuspended in serum free PCT Airway Epithelial Medium Complete (Millipore #CnT-17, Temecula, CA), transferred to collagen-coated, 75cm2 flask, and incubated at 37° C, 5% C02. Medium was changed every other day until cells reached desired confluency.

Cells were passaged by removing medium from the flask and adding 4 mL trypsin-EDTA (Invitrogen #25200) for about 10 minutes. Collected cells were transferred to a 50 mL tube containing DMEM/F12, with FCS added to 5% to stop the action of trypsin. A second treatment with trypsin-EDTA was sometimes necessary to collect cells that remained tightly adhered to the flask. The flask was then rinsed with 5 mL DMEM/F12 to collect any loose cells, and added to the cell pool also, which was centrifuged (10 min, 1000 rpm, 4°C), followed by resuspension in DMEM/F12 for cell rinsing and counting. Centrifugation was repeated, and the cell pellet was resuspended in serum free PCT Airway Epithelial Medium to the desired concentration for seeding flasks or culture plates, which were incubated at 37° C, 5% C02.

Cells were prepared for frozen storage by adding approximately 500,000 cells, suspended in 1 mL PCT Airway Epithelial Medium Complete, to a cryovial containing 0.6 mL FCS and 0.18 mL DMSO. Vials were placed in a Cryo 1°C Freezing Container (Nalgene Cat. No. 5100-0001, Rochester, NY) overnight at −80°C, and then transferred to a liquid nitrogen canister for long term storage. To bring cells out of frozen storage, vials were quickly thawed in a 37°C water bath and contents were transferred to a 50mL tube, where 10 mL of warmed DMEM/F12 was slowly added dropwise, with swirling, to the tube. Cells were spun down at 1000 rpm for 10 minutes, resuspended in 10 mL serum free PCT Airway Epithelial Medium Complete, and added to a prepared collagen-coated flask for incubation at 37°C, 5% C02. The medium was replaced 24 hours later to ensure any residual FCS or DMSO was removed.

Isolation and culture of primary fibroblast cells from mice

In order to obtain mouse fibroblasts for negative control in staining procedures, a BALB/c mouse trachea was minced in a sterile, 35mm culture dish, incubated at 37°C, 5% C02 for one hour with 1 mL collagenase solution (10mg/mL, Sigma #C9407), then collected into a tube and centrifuged. The pellet was resuspended in DMEM with 15% FCS plus amphotericin B (1.25 μg/mL), penicillin (100 U/mL) and streptomycin (0.1 mg/mL), and returned to the 35 mm culture dish for one week (37° C, 5% C02). Medium was then replaced as needed until cell density was high enough to harvest cells for seeding onto coverslips.

Cell lines and virus

HeLa cells were grown in MEM (GIBCO; Invitrogen) supplemented with Earle’s Salts, L-glutamine, 100 U/ml penicillin, and 0.1 mg/ml streptomycin. This medium was further supplemented with 10% fetal calf serum (Sigma). LA-4 cells (mouse respiratory epithelial cell line) were grown in Kaighn’s nutrient mixture F-12 medium, 1X (Mediatech, Inc., Herndon, VA) supplemented with 10% fetal calf serum (Sigma), 100 U/ml penicillin and 0.1 mg/ml streptomycin. Viral serotypes HRV-1A, 1B, 2, 3 and 5 were kindly provided by Wai-Ming Lee, University of Wisconsin-Madison, for propagation on HeLa and L-cells.

Immunohistochemistry

Mouse airway epithelial and fibroblast cells grown on coverslips were fixed with 5% formalin for 40 minutes, permeabilized with 0.3% Triton X-100 for 10 minutes, and stored in PBS/10% FCS. One set of cells was stained with monoclonal anti-cytokeratin pan-FITC antibody (1:100 dilution; Sigma #F-0397) for one hour. Another set was stained with vimentin (C-20) goat polyclonal IgG (1:50 dilution; Santa Cruz #SC-7557, Santa Cruz, CA) primary antibody for one hour, followed by Alexa Fluor 594 rabbit anti-goat IgG (H+L) (1:100 dilution; Invitrogen #A11080) secondary antibody for one hour. In both cases, DAPI nuclear stain was used at 1:20,000. Coverslips were mounted on slides using Vectashield (Vector Laboratories, Burlingame, CA), and were examined using confocal microscopy.

Infection of cells

Subconfluent cell monolayers (>75%) were inoculated with a minimal volume of viral suspension at a multiplicity of infection (MOI) of 10 PFU/cell, incubated at RT for 1 hour with gentle shaking for virus attachment, washed with PBS, and incubated in medium without serum at 34°C. At designated time points, media from cells was aspirated and cells were collected from the plate in Trizol reagent (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA) for analysis by real-time PCR.

Virus plaque assay

Virus plaque assay was performed as described by Mosser (Mosser et al., 2002). Confluent Hela cell monolayers in 6-well plates were exposed to serial dilutions of infected samples for 1 hour with gentle shaking. The cells then were overlaid with 1.8% Noble Agar and medium without serum. After 60 hours of incubation at 34°C, monolayers were fixed with 10% formalin and stained with 0.1% crystal violet in 20% ethanol solution. Viral plaques were then counted to express titers as PFU/mL.

Western blot

Primary cells were infected with HRV-1A (10 pfu/cell) for 24 hrs (human cells) or 48 hrs (mouse cells), after which cells were collected, lysed in sample buffer, and whole cell lysates containing equal amounts of protein were loaded onto 12% SDS-PAGE gels for electrophoretic separation. Separated proteins were transferred to Immobilon transfer membranes (Millipore). The membrane was treated with 10% blocking buffer overnight and then incubated for 1 hour with rabbit anti-3C polyclonal antibody (1:10,000 dilution in 0.5% blocking buffer) that was produced by inoculating New Zealand White rabbits (Indianapolis, IN) with purified viral 3C protease (Amineva, et al., 2004). The activity of the polyclonal antibody had previously been tested in a western blot assay against native viral proteins from HRV-infected HeLa cells. Next, the membrane was washed and incubated with anti-rabbit immunoglobulin conjugate in 0.5% blocking buffer. After two subsequent washes, bands were visualized by chemiluminescence with SuperSignal West Dura Western blotting developing reagent, (PIERCE, Rockford, IL).

Real-time PCR for detection of viral RNA replication

To analyze replication of HRV RNA in mouse and human cells, total RNA was extracted from infected cells with Trizol reagent (Invitrogen) and reverse transcribed. Using specific primers, real-time PCR was performed as described earlier (Mosser et al., 2002). Results were compared with samples containing known amounts of virus (PFU/mL), and geometric mean values were calculated (PCR unit equivalents of PFU/mL).

Results

Serial culture of primary mouse airway epithelial cells

The initial aim was to develop a system for serial culture of primary mouse airway cells. Following collection of the trachea, separation of the epithelial cells from the parent tissue was best achieved using an overnight enzymatic treatment at 4°C, as opposed to a shorter time (1 hr) at a higher temperature (37°C), which yielded relatively low numbers of cells. Submerged culture of harvested cells was then performed with a panel of various serum-free media and supplements, and optimal cell growth was observed using PCT Airway Epithelia Medium Complete (Millipore #CnT-17). Notably, this protocol was successful with cells from C57BL/6N mice, but not with BALB/c mice. Thus, both the mouse strain and medium were important.

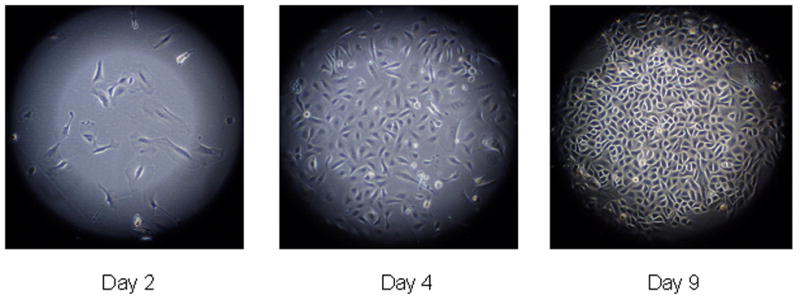

Cultures of passage 0 (P0) cells taken directly from tissue consistently took several days to establish. Primary mouse airway epithelial cells proved more tolerant of dense numbers than primary human airway epithelial cells, and in fact did not grow well if seeded at densities less than ~400,000 cells per T-25 flask. Medium changes were required every 2–3 days for optimal growth. Even so, adherent cells were typically sparse for several days, with only a few “islands” of cells with typical epithelial morphology, including small numbers of ciliated cells. These islands then spread and became confluent over the course of a couple of weeks. This is in contrast to human cells, which disperse and fill in the flask more evenly. As cells progressed through several passages, they grew more evenly, doubling in number approximately every three days (Fig. 1).

Figure 1.

Mouse (C57BL/6N) primary airway epithelial cells from serial passage.

Serial culture of the cells was continued through four rounds of subculture, indicating that primary mouse airway epithelial cells can be isolated and expanded for several passages with no loss of vigor and with success similar to that seen with human cells. In additional tests, cultures were restarted from cells placed in frozen storage. Viability upon thawing allowed reestablishment of cultures that required about eight days for an initial doubling, after which growth matched that of cells grown without interruption. Thus, multiple vials of frozen stocks could be created from expanded cells for the convenient reestablishment of future cultures, eliminating the need to sacrifice animals each time.

Immunostaining of cultured airway epithelial cells

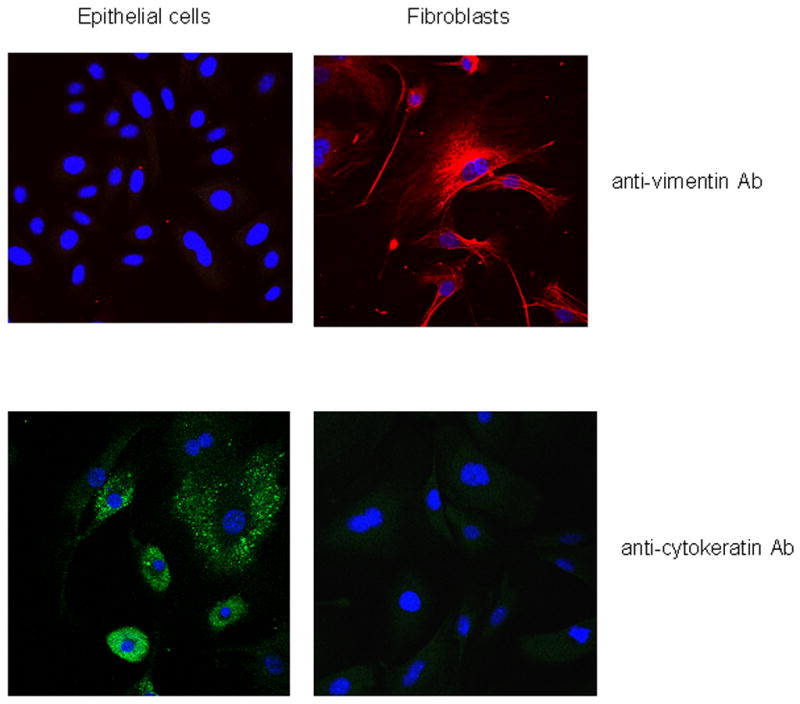

Cultured cell monolayers were stained with monoclonal anti-cytokeratin pan-FITC, as well as antibody against vimentin, a marker of fibroblasts. The cell monolayers exhibited specific staining for cytokeratins, a family of intermediate filaments comprising the cytoskeleton of epithelial cells, while only fibroblast control cells stained positive for vimentin, demonstrating that the monolayers were epithelial in nature (Fig. 2).

Figure 2.

Differential staining of epithelial cells and fibroblasts with antibodies to vimentin and cytokeratins.

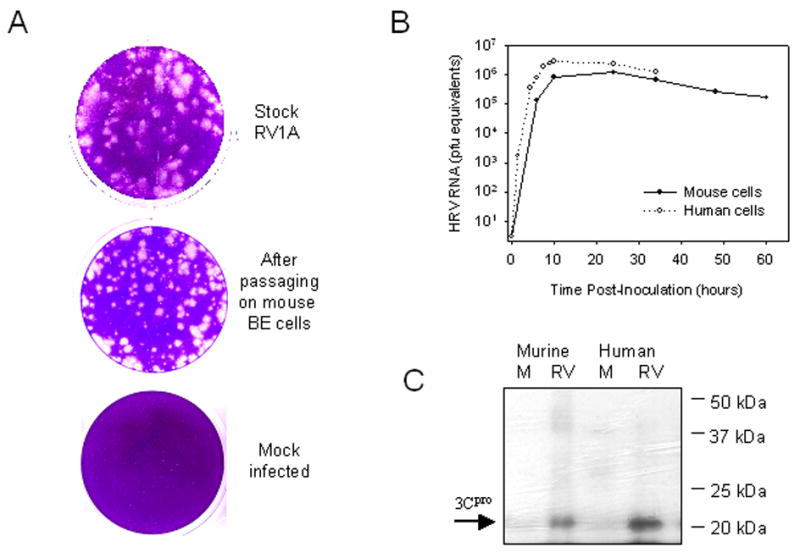

Mouse epithelial cell lines have been reported to support growth of minor group HRV (Tuthill, 2003). In preliminary experiments, HRV-1A produced CPE in murine LA-4 cells after 60 hours of incubation (data not shown). Next, cultures of primary mouse airway epithelial cells were inoculated with HRV-1A (MOI = 10) for 1hr, washed to remove input virus, and incubated for 60 hours. The titer of HRV-1A in cell lysates was 8.5 × 107 PFU/mL. Plaque characteristics in HeLa cells were similar for HRV-1A from the mouse cell lysates compared to the stock HRV-1A suspension (Fig. 3A).

Figure 3.

(A) Plaque assay of virus collected after passaging on primary mouse cells. (B) Replication of RV1A RNA in primary human and mouse BE cells. Cells were infected with 10 PFU/cell of HRV 1A and, at different time points, the viral RNA replication was analyzed by real time PCR. (C) Western blot assay with polyclonal antibodies to RV 3C protease to analyze synthesis of non-structural viral proteins in mock- (M) and RV-infected mouse and human BE cells.

To compare replication in mouse vs. human cells, cultures of human and mouse primary airway epithelial cells were infected with HRV-1A (10 PFU/cell), and the level of viral RNA in the cells was serially measured for up to 60 hours (Fig. 3B). Viral RNA increased quickly in primary human cells, reaching a peak of 2.8×106 PFU equivalents at 12 hours. Levels of viral RNA increased at a slower rate in primary mouse cells, reaching a peak of 1.2×106 PFU equivalents at 24 hours. Viral cytopathic effect (CPE) was evident with human primary cells at 24 hours post-infection, with cells appearing rounded and detached from the monolayer. CPE in primary mouse cells was present, but less extensive.

Finally, whole cell lysates of uninfected and HRV-1A infected cells were analyzed for the presence of 3C protease by Western blot. A strong band corresponding to 3C protein was detected in both the mouse and human HRV-1A infected samples after 24 hrs of infection but not in samples of uninfected cells (Fig. 3C).

Discussion

In this paper we describe techniques for the serial culture of murine airway epithelial cells. The methods closely parallel those designed for human cells, which have been used successfully for many years. While the mouse model does not, as of yet, have the benefit of specially tailored commercial media preparations, cell growth was successfully maintained with components that are readily available. The epithelial nature of the cells and culture purity was confirmed via staining for pan-cytokeratin and vimentin, using mouse fibroblast cells as negative control. Previous studies of murine epithelial cells have relied on transformed cell lines, which may have important differences compared to nontransformed cells, or else have used cells freshly prepared from lung tissue for each experiment. Compared to the latter, cultured cells can establish confluent monolayers more quickly, without the need to sacrifice animals each time. Furthermore, the cultures can be established and expanded from a relatively small number of mouse tracheal cells, which are readily cryopreserved. The culture of primary mouse airway epithelial cells as the serial passage system provides a new model to study airway diseases in general, and specifically mechanisms of virus-induced disease. This model does not replace the need for differentiated cell systems, but serves as an additional tool to provide a ready supply of undifferentiated airway epithelial cells. The serial culture system also has the potential to facilitate the adaptation of viruses for growth in the mouse.

The study of HRV pathogenesis has historically been hampered by the lack of a suitable murine model. Recently, HRV have been shown to have limited replication in mice, and for major group viruses, this has required the use of a transgenic mouse expressing human ICAM-1. The primary cell culture system described here will extend these models by providing a model for the study of effects of RV infection on isolated airway epithelial cells. Similarly, this model should prove useful for the study of other respiratory viruses (e.g. influenza, RSV), and non-viral airway inflammatory responses.

The ability of HRV-1A to replicate in these primary mouse cells was confirmed via three sets of evidence. First, viral RNA in mouse cells increased steadily, peaking 24 hours after inoculation. Furthermore, RV replication in murine epithelial cells was confirmed by the de novo synthesis of the nonstructural 3C protease and also the synthesis and release of infectious viral particles. The kinetics of RV RNA accumulation was slower in murine cells, peaking 24 hrs after inoculation vs. 12 hrs post-inoculation in human cells. The reason for the difference in viral kinetic profiles is unknown, but could be related to mismatches between viral and host proteins required for replication, or species-specific differences in tracheal epithelial cell populations (Pack, et al). For example, tracheal cell populations in mice are relatively deficient in goblet cells, which make up approximately 10 to 20% of epithelial cells in human airways (Harkema, et al).

In conclusion, this system for serial culture of murine airway epithelial cells has potential to be useful in research related to a variety of airway disorders. This system may be especially useful to study pathogenic mechanisms of respiratory viruses, including HRVs, which have been difficult to study in the mouse. The wide variety of immunologic reagents developed for the mouse, as well as the availability of mice lacking key antiviral pathways, should be very useful to study host/virus interactions in cultured airway epithelium.

Abbreviations

- HRV

human rhinovirus

- COPD

chronic obstructive pulmonary disease

- LDLr

low density lipoprotein receptor

- DMEM

Dulbecco’s minimal essential medium

- F12

Ham’s F12 medium

- MEM

minimal essential medium

- FCS

fetal calf serum

- PCT

progenitor cell targeted

- DMSO

dimethyl sulfoxide

- qPCR

quantitative polymerase chain reaction

- HEPES

N-2-Hydroxyetheylpiperazine-N′-2-ethane sulfonic acid

- MOI

multiplicity of infection

- SDS-PAGE

sodium dodecyl sulfate polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis

- ICAM-1

intercellular adhesion molecule 1

- CPE

cytopathic effect

- RNA

ribonucleic acid

- PFU

plaque forming unit

- FITC

fluorescein isothiocyanate

- ALI

air liquid interface

- DAPI

4′,6-diamidino-2-phenylindole

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- Amineva SP, Aminev AG, Palmenburg AC, Gern JE. Rhinovirus 3C protease precursors 3CD and 3CD’ localize to the nuclei of infected cells. J Gen Virol. 2004;85:2969. doi: 10.1099/vir.0.80164-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Braman SS. The global burden of asthma. Chest. 2006;130:4S. doi: 10.1378/chest.130.1_suppl.4S. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bartlett NW, Walton RP, Edwards MR, Aniscenko J, Caramori G, Zhu J, Glanville N, Choy KJ, Jourdan P, Burnet J, Tuthill TJ, Pedrick MS, Hurle MJ, Plumpton C, Sharp NA, Bussell JN, Swallow DM, Schwarze J, Guy B, Almond JW, Jeffery PK, Lloyd CM, Papi A, Killington RA, Rowlands DJ, Blair ED, Clarke NJ, Johnston SL. Mouse models of rhinovirus-induced disease and exacerbation of allergic airway inflammation. Nat Med. 2008;14:199. doi: 10.1038/nm1713. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Davidson DJ, Kilanowski FM, Randell SH, Sheppard DN, Dorin JR. A primary culture model of differentiated murine tracheal epithelium. Am J Physiol Lung Cell Mol Physiol. 2000;279:L766. doi: 10.1152/ajplung.2000.279.4.L766. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harkema JR, Mariassy A, StGeorge J, Hyde DM, Plopper CG. Epithelial cells of the conducting airways: a species comparison. In: Farmer SG, Hay DWP, editors. The Airway Epithelium: Physiology, pathophysiology, and pharmacology. Marcel Dekker; New York: 1991. p. 3. [Google Scholar]

- Harris JR, Racaniello VR. Changes in rhinovirus protein 2C allow efficient replication in mouse cells. J Virol. 2003;77:4773. doi: 10.1128/JVI.77.8.4773-4780.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hofer F, Gruenberger M, Kowalski H, Machat H, Huettinger M, Kuechler E, Blaas D. Members of the low density lipoprotein receptor family mediate cell entry of a minor-group common cold virus. Proc Natl Acad Sci. 1994;91:1839. doi: 10.1073/pnas.91.5.1839. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lomax NB, Yin FH. Evidence for the role of the P2 protein of human rhinovirus in its host range change. J Virol. 1989;63:2396. doi: 10.1128/jvi.63.5.2396-2399.1989. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mosser AG, Brockman-Schneider RA, Amineva S, Burchell L, Sedgwick JB, Busse WW, Gern JE. Similar frequency of rhinovirus-infectible cells in upper and lower airway epithelium. J Infect Dis. 2002;185:734. doi: 10.1086/339339. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Newcomb DC, Sajjan US, Nagarkar DR, Wang Q, Nanua S, Zhou Y, McHenry CL, Hennrick KT, Tsai WC, Bentley JK, Lukacs NW, Johnston SL, Hershenson MB. Human rhinovirus 1B exposure induces phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase-dependent airway inflammation in mice. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2008;177:1111. doi: 10.1164/rccm.200708-1243OC. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pack RJ, Al-Ugaily LH, Morris G, Widdicombe JG. The distribution and structure of cells in the tracheal epithelium of the mouse. Cell Tissue Res. 1980;208:65. doi: 10.1007/BF00234174. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tuthill TJ, Papadopoulos NG, Jourdan P, Challinor LJ, Sharp NA, Plumpton C, Shah K, Barnard S, Dash L, Burnet J, Killington RA, Rowlands DJ, Clarke NJ, Blair ED, Johnston SL. Mouse respiratory epithelial cells support efficient replication of human rhinovirus. J Gen Virol. 2003;84:2829. doi: 10.1099/vir.0.19109-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yin FH, Lomax NB. Host range mutants of human rhinovirus in which nonstructural proteins are altered. J Virol. 1983;48:410. doi: 10.1128/jvi.48.2.410-418.1983. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yin FH, Lomax NB. Establishment of a mouse model for human rhinovirus infection. J Gen Virol. 1986;67:2335. doi: 10.1099/0022-1317-67-11-2335. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- You Y, Richer EJ, Huang T, Brody SL. Growth and differentiation of mouse tracheal epithelial cells: selection of a proliferative population. Am J Physiol Lung Cell Mol Physiol. 2002;283:L1315. doi: 10.1152/ajplung.00169.2002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]