Abstract

Genetically modified mice susceptible to atherosclerosis are widely used in atherosclerosis research. Although the atherosclerotic lesions in these animals show similarities to those in humans, comprehensive expression profile analysis of these lesions is limited by their very small size. In this communication, we have developed an approach to analyze global gene expression in mouse lesions by a combination of (a) laser capture microdissection (LCM) to isolate RNA from specific lesions, (b) an efficient RNA amplification method that reliably yields sufficient quantities of high quality cRNA for quantitative real-time PCR (qPCR), as well as for microarray analysis. The RNA passed multiple quality controls and the expression profile observed in lesional cells compared with the whole artery encompasses genes that are characteristic of a macrophage/foam cell population. We believe that this method represents a useful new tool for the unbiased analysis of global gene expression of specific sub-regions in atherosclerotic lesions in different rodent models.

Keywords: atherosclerosis, gene expression, IVT, LCM, microarrays

Introduction

Atherosclerosis is the main underlying pathology of cardiovascular disease (CVD) and stroke, two major causes of morbidity and mortality in the developed countries[1]. Genetically modified mouse models with increased susceptibility to atherosclerosis, such as the apolipoprotein E-deficient mice (apoE−/−) mice, are an excellent tool to study the pathophysiology of atherogenesis and to test novel treatments [2–4]. There is substantial similarity in the histopathology of atheromatous lesions in apoE−/− mice and in humans, but the time span needed to observe significant progression is weeks to months in these mice as compared with decades in people[4,5]. A major drawback in studying atherosclerotic lesions in mice is their small size, which makes it difficult to perform certain kinds of analysis, such as gene expression profiling. One way of studying gene expression of microscopic areas in histological sections is by laser capture microdissection (LCM), which allows the selective isolation of individual cells or cell clusters from tissue sections under direct microscopy[6]. In fact, this technique has been applied in experiments on gene expression in atherosclerotic lesions in mice [7]. On the other hand, the small amount of RNA that can be isolated by this technique limits the analysis to the targeted quantitative PCR of genes of interest. While useful information is generated, such an approach by necessity introduces a selection bias, as only a very small subset of transcripts can be quantified compared to thousands that could be examined using a microarray approach. Microarray analysis is a powerful technique to examine tissue-specific expression profiles and has been used extensively to analyze normal and pathological tissues, including human atherosclerotic lesions[8]. Unfortunately, such analysis requires the isolation of RNA from a sizeable amount of tissue, a technical limitation that has thus far precluded the use of microarrays to study the expression profile of atherosclerotic lesions in mouse models. Interestingly, in other situations where it is necessary to analyze small cell populations with minimal interference of surrounding cells, such as for example pure cancer cell populations or different neuronal cell subtypes, the amplification of the RNA captured by LCM has facilitated extensive expression profiling [9–11]. The combination of the unbiased and global expression profile afforded by microarray analysis and the highly selective isolation of cells from subregions within atherosclerotic lesions by LCM, if it can be accomplished, would represent a significant advance, not only in atherosclerosis research but also in other fields.

In this communication, we show that we can couple microarray analysis with LCM sample by demonstrating that RNA isolated from macrophage-rich areas of mouse-atherosclerotic lesions by LCM can be amplified to produce sufficient amounts of complementary RNA (cRNA), which can be used for quantitative RT-PCR (qPCR) and for microarray analysis. Multiple quality control experiments show that the cRNA is of good quality, and the analysis of this cRNA produces reproducible data that have the expected representation of specific marker genes, thus supporting the efficacy and power of the technology.

Methods

Mice

Male apolipoprotein E-deficient (apoE−/−) mice (B6.129P2-Apoetm1Unc, Jackson Laboratories, Bar Harbor, Me) were used for this study. The mice had free access to standard chow and water until the time of sacrifice, which was performed by exsanguination under general anesthesia (avertin). All animal experiments were conducted following protocols for handling and treatment of animals approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee at Baylor College of Medicine.

LCM and RNA extraction and amplification

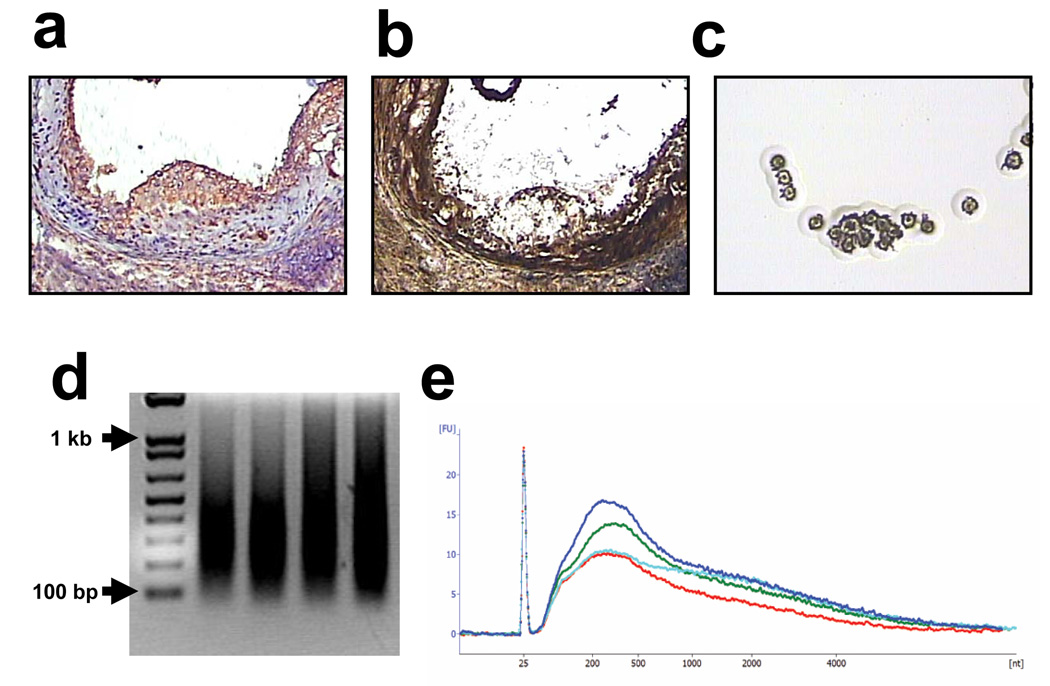

We isolated macrophage-rich areas from atherosclerotic lesions of four ~29-weeks old apoE−/− mice. Immediately after sacrifice, the hearts were perfused with PBS, excised, bisected with a parallel cut approximately 1 mm under the tips of the atria, embedded in O.C.T. (Sakura), frozen on dry ice, and stored at −80°C. For LCM, approximately 30-7 µm sections of each aortic sinus were performed on a Leica CM3050 S cryostat and consecutive sections were mounted on 3 different Superfrost®/Plus slides (Fisher Scientific). The first and third slides, used for LCM, were immediately fixed, stained with toluidine blue and dehydrated with the HistoGene™ LCM Frozen Section Staining Kit (Molecular Devices Corporation). These slides were stored O/N at room temperature in a slide box containing fresh desiccant. The second slide was stained for macrophages with anti Mac-3 antibody (Santa Cruz Biotechnology) as previously described [12], and used as template to distinguish the macrophage-rich areas in the lesions. LCM of macrophages was performed with a Veritas Microdissection System (Molecular Devices Corporation) using the CapSure™ HS LCM Caps (Molecular Devices Corporation). We used approximately 20 sections of each aortic sinus to perform ~2000 laser shots (the laser power was set to ~65 mV and the pulse duration was 2500 µ-seconds, resulting in a spot size of ~20 µm) on macrophage-rich areas of atherosclerotic lesions (Figure 1a–1c). RNA was extracted immediately after LCM with the PicoPure™ RNA Isolation Kit (Molecular Devices Corporation) and stored at −80°C until amplification. In our experience it takes approximately one hour to perform LCM for each sample and the RNAs can be extracted in less than two hours.

Figure 1.

(a) Immunoreactive macrophages in aortic atherosclerotic lesions (brown color); (b) a consecutive section used for LCM showing that some of the macrophages have been dissected; and (c) picture of the cap used for LCM showing the captured macrophages. (d and e) Size distribution of the amplified cRNA by agarose gel electrophoresis (d) and in a electropherogram performed with the Agilent 2100 bioanalyzer (e).

To amplify the RNA, we performed two rounds of amplification with the RiboAmp™ HS RNA Amplification Kit (Molecular Devices). Briefly, each amplification cycle consists of a reverse transcription and double strand cDNA synthesis followed by an in vitro transcription (IVT) reaction with a T7 RNA polymerase. This is a method of linear amplification that can yield µg amounts of cRNA from picogram or low nanogram amounts of starting RNA[13]. Because the initial RNA amount is very low, 1 µL of 200 ng/µL nucleic acid carrier such as Poly (I) or Poly (dI-dC) must be added to the sample prior to the first round of amplification. We note that we got better results for both quantitative real-time PCR (qPCR) and microarrays with Poly (I) than with Poly (dI-dC). The time required for RNA amplification is ~20 hours, but since the amplification protocol can be stopped at several points, the whole process can be performed in two days.

We also used four apoE−/− mice to obtain RNA from whole aorta. At ~35-weeks, when apoE−/− mice’s lesions are widely distributed throughout the arterial tree[4,14], the mice were sacrificed by exsanguination, the aortas were rapidly isolated, thoroughly cleaned under a dissection microscope, and immediately frozen in liquid nitrogen. RNA extraction was performed with Absolutely RNA® Miniprep Kit (Stratagene) as previously described [12].

Quantitative real-time PCR (qPCR)

Reverse transcription of lesional or aortic cRNA was performed with SuperScript™ III (Invitrogen) using random hexamers as primers. Primers for qPCR were designed with primer3 software [15]. Because the concentration of the house-keeping genes may vary between both types of samples, we used seven different housekeeping genes {Cyclophilin A (cyclo A), ubiquitin C (UBC), β-actin, glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase (GAPDH), topoisomerase I ( TOP1), eukaryotic translation initiation factor 4A2 (EIF4A2), and calnexin} and, among them, selected the most stable in both the whole aorta and lesional macrophages using the GENORM software as previously described by Vandesompele et al. [16]. Since the IVT amplification is known to result in a 3’-bias, i.e. a shortening of the amplified cRNA compared to the parent mRNA, the primers were designed in the 3’-terminus region of the mRNA, including the 3’ untranslated region (Table 1). qPCRs were performed on 25 ng of cDNA with iQ™ SYBR® Green Supermix (BIO-RAD) using 40 amplification cycles (95°C for 30 s, 55°C for 1 min, 72°C for 1 min) with the Mx3000P (Stratagene). The specificities of the reactions were assessed by analyzing the melting curves (single peak) and by gel electrophoresis (single band).

Table 1.

Primer Sequences.

| Gene | Primer Sequences | GenBank |

|---|---|---|

| Cyclo A | Forward: 5’-tttgggaaggtgaaagaagg-3’ | NM_008907 |

| Reverse: 5’-ttacaggacattgcgagcag-3’ | ||

| UBC | Forward: 5’-agaaagagtccaccctgcac-3’ | NM_019639 |

| Reverse: 5’-tcacacccaagaacaagcac-3’ | ||

| β-actin | Forward: 5’-ggggaaggtgacagcattg-3’ | NM_007393 |

| Reverse: 5’-ctggctgcctcaacacct-3’ | ||

| GAPDH | Forward: 5’-ggcattgctctcaatgacaa-3’ | XM_01473623 |

| Reverse: 5’-tgtgagggagatgctcagtg-3’ | ||

| TOP1 | Forward: 5’-ggtccaagaaaaacaaaaacca-3’ | NM_009408 |

| Reverse: 5’-ggaatggactctgcacacac-3’ | ||

| EIF4A2 | Forward: 5’-tctgcctttattgtgtttgtca-3’ | NM_013506 |

| Reverse: 5’-ggcaattttactgggggttt-3’ | ||

| Calnexin | Forward: 5’-gcagatgggtgctagaggag-3’ | NM_007597 |

| Reverse: 5’-tttcccagtatttccccaat-3’ | ||

| CD68 | Forward: 5’-gctgttcaccttgacctgct-3’ | NM_009853 |

| Reverse: 5’-agaggggctggtaggttgat-3’ | ||

| CD14 | Forward: 5’-gtggccttgtcaggaactct-3’ | NM_009841 |

| Reverse: 5’-atcaggggtcaagtttgctg-3’ | ||

| α-actin | Forward: 5’-tcaacagaggaaggtccactt-3’ | NM_007392 |

| Reverse: 5’-acttgccaaattttaaatacacg-3’ | ||

| MYH11 | Forward: 5’-cacaggaaacttcgcagtga-3’ | NM_013607 |

| Reverse: 5’-ttctgttttccctgacatggt-3’ | ||

| IL-1β | Forward: 5’-accatggcacattctgttca-3’ | NM_008361 |

| Reverse: 5’-agacctcagtgcgggctat-3’ | ||

| TNFα | Forward: 5’-gtcctggaggacccagtgt-3’ | NM_013696 |

| Reverse: 5’- gggagcagaggttcagtgat-3’ | ||

| SR-A1 | Forward: 5’-gccctgttcagaagcatca-3’ | NM_031195 |

| Reverse: 5’-cttgatcacgagcacagcat-3’ | ||

| ABCA1 | Forward: 5’-tggatctatttttgcactgga-3’ | NM_013454 |

| Reverse: 5’-cagcaggactgtcacagcttta-3’ | ||

| ADFP | Forward: 5’-tggtgagtggcctgtgttag-3’ | NM_007408 |

| Reverse: 5’-cacacgccttgagagaaaca-3’ |

Microarrays

The cRNA was hybridized to Mouse Genome 430 2.0 Arrays from Affymetrix (Santa Clara, California). Affymetrix protocols require the addition of 15 µg of fragmented biotinylated cRNA to a final volume of 300 µL of hybridization cocktail. The standard Affymetrix labeling protocol uses an IVT amplification reaction to incorporate biotinylated nucleotide analogs. In case the initial concentration of RNA is very low, a first cycle of amplification can be performed with unlabeled nucleotides and the product can be amplified and labeled in a second amplification cycle that incorporates biotinylated ribonucleotide analogs. In our case, we performed two rounds of amplification using unlabeled ribonucleotides, and labeled an aliquot (20 µg) of the cRNA with the TURBO Labeling™ Biotin kit from Molecular Devices Corporation, based on a chemical reaction that forms a coordinate bond between the N7 position of guanine and a platinum-biotin complex . This labeling method can be performed in less than 1 hour and allows retaining a portion of the cRNA as unlabeled, for other applications such as qPCR. 15 µg of the labeled cRNA were fragmented and hybridized to the Mouse Genome 430 2.0 Arrays following the protocols from Molecular Devices Corporation and Affymetrix. Washing, staining and scanning were performed following the Affymetrix protocols.

Statistical analysis

Statistical analysis was carried out with SPSS 15.0 for windows. The groups were compared by the Student’s t-test or the Mann-Whitney U. Differences were considered significant when p<0.05. In all tables and figures the values are presented as mean ± SD.

Results

cRNA yield and quality control

We determined the yield of amplified cRNA by reading the absorbance at 260 nm (A260) of samples diluted 1:10 with the NanoDrop® ND-1000 Spectrophotometer. In all cases we were able to obtain a considerable amount of cRNA (average: 66.0 µg; minimum: 42.6; maximum: 89.7 µg). We then proceeded to assess the quality of the cRNA. Most of the cellular RNA is ribosomal RNA; thus, the integrity of the ribosomal RNA bands is commonly used to determine RNA quality[17]. However, our protocol for RNA amplification involves two rounds of in vitro transcription with T7 RNA polymerase. For that, the T7 promoter is ligated to an oligo(dT)-primer {oligo(dT)-T7} and incorporated during the generation of the cDNA. Thus, only mRNAs, that have a polyA tail, but not ribosomal RNAs, are amplified and, therefore, the ribosomal RNA cannot be used for quality control to test the integrity of the cRNA and other parameters need to be used. Typically, an A260/A280 ratio between 2.0 and 2.6 indicates very pure cRNA and, in our samples, this ratio ranged between 2.19 and 2.45. Assessing the size of the amplification product is also a useful parameter to assess the quality of the cRNA, which typically ranges in length between 200 and 2000 nucleotides[18]. We assessed the size of the cRNA by agarose gel electrophoresis and also with the Agilent 2100 bioanalyzer and, as shown in Figure 1d and 1e, by both techniques the cRNA appears as a single broad peak and no degradation products are observed in any sample. Therefore, RNA isolated from macrophage-rich areas of atherosclerotic lesions by LCM can be amplified to produce large amounts of cRNA of high quality.

qPCR analysis

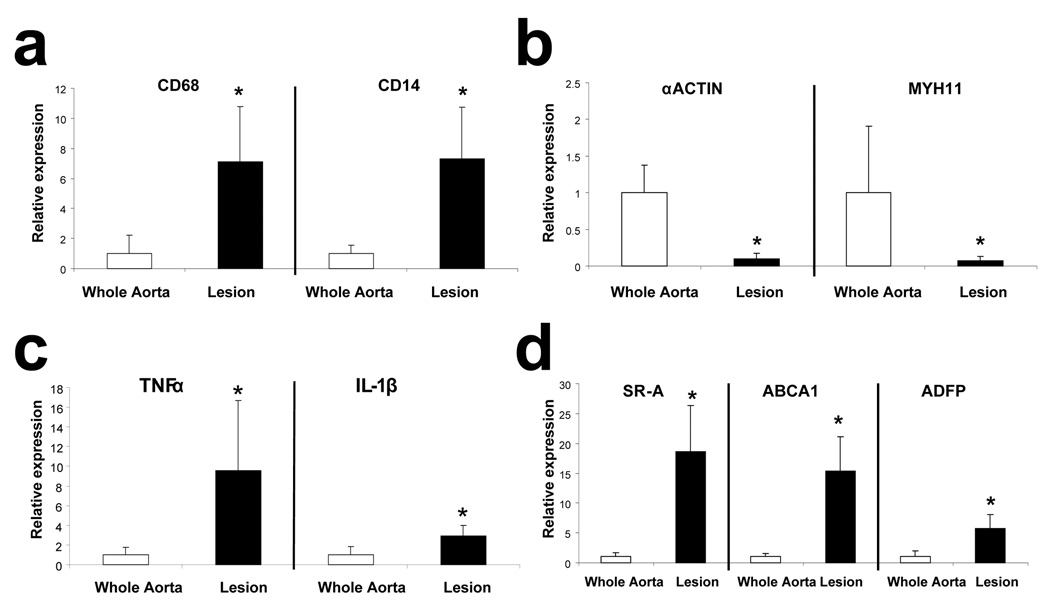

After showing that we can produce large amounts of cRNA, we tested if it could be used for qPCR analysis and, if so, if the gene expression pattern was consistent with that expected in a cell population composed predominantly of foam cells. For example, we anticipate that, compared to RNA isolated from whole aorta, the RNA captured from macrophages would be enriched in macrophage specific transcripts and depleted of markers of other cell types such as smooth muscle cells (SMC). To assess this, we compared gene expression in amplified cRNA captured by LCM from macrophage–rich areas of lesions with amplified cRNA isolated from whole aorta. Of the 7 housekeeping genes we used, by the Genorm approach[16], we determined that the two most stable housekeeping genes for both tissues were EIF4A2 and cyclo A and, therefore, we normalized the data to the combination of these two genes. As expected, the two macrophage transcripts we analyzed, CD68 and CD14,were markedly increased in the cRNA from lesions (Figure 2a), whereas the two SMC markers, α-actin and MYH11(encoding SMC myosin heavy chain)[19] were markedly depleted (Figure 2b). Furthermore, two markers of inflammation (TNFα and IL-1β) were also enriched in macrophage cRNA (Figure 2c). Finally, SR-A, a major player in lipoprotein uptake by foam cells[20], ABCA-1, which plays an important role in cholesterol efflux[21], and ADFP, the main lipid-droplet associated protein in macrophages[22], are also well enriched in the cRNA isolated from macrophages (Figure 2d). Therefore, we conclude that the cRNA amplified from macrophage rich areas of atherosclerotic lesions is well suited for qPCR analysis, and that the pattern of gene expression is consistent with that expected in a macrophage/foam cell rich cell population.

Figure 2.

Relative expression of (a) macrophages markers; (b) SMC markers; (c) inflammation markers; and (d) other foam cell markers in cRNA amplified from macrophage rich areas of atherosclerotic lesions or from whole aorta (n=4, *p<0.05). Bars represent means and SDs.

Microarray analysis

Microarray analysis enables the measurement of the expression of thousands of genes in a single RNA sample[23] and, thus, it would be a very useful technique for the study of atherosclerosis in mouse models. After showing that with amplification we can obtain microgram amounts of cRNA necessary for microarray hybridization, we tested whether this cRNA would yield reproducible data in microarray analysis. We assessed several general quality controls used for microarrays. In the 4 samples the spots were relatively uniform in size and there were not areas of low intensity or high background. In all cases the boundaries of the arrays were easily identified by the hybridization of the B2 oligonucleotides. As shown in Table 2, the arrays displayed relatively low and comparable background and noise values. Furthermore, the % of genes called “present” (%P) was also similar among different samples, and so was the average signal of the genes called present, which was ~20-fold higher than the average background (Table 2). The scaling factor is the number used to adjust the value of every array to a common value in order to make the arrays comparable. Per Affymetrix protocols, the scaling factors should lie within three folds of each other, and larger discrepancies may indicate assay variability or sample degradation. As shown in Table 2, the scaling factors of the four samples analyzed were very similar. As we commented on before, a 3′ bias is expected when IVTs are used to amplify RNA[24]. Therefore, not surprisingly we found relatively high β-actin and GAPDH 3’/5’ ratios in all our samples; the high ratio is inherent to the amplification process and is one difference that we can expect from amplified RNA as compared to unamplified RNA. Furthermore, since the standard Affymetrix labeling procedure also involves an IVT reaction, to maximize the %P most probe sets are designed to be within the most 3’ 600 nucleotides of the transcripts, which has enabled us to obtain a high %P in the analysis in the presence of the relatively high 3’/5’ ratios.

Table 2. Selected quality control parameters of microarray hybridization.

The % of genes called present, background, noise, average signal of the genes called present, and scaling factor lie within the expected normal ranges in Affymetrix microarrays. High 3’/5’ ratios are expected when the RNA is submitted to two rounds of amplification.

| Background | Noise | % Present | Average Signal of Present | Scaling Factor | Actin 3’/5’ | GAPDH 3’/5’ | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sample 1 | 91.56 | 4.74 | 42.3 | 2051 | 3.01 | 70.3 | 51.7 |

| Sample 2 | 92.71 | 5.32 | 45.0 | 1847 | 2.50 | 67.5 | 39.2 |

| Sample 3 | 86.84 | 4.18 | 37.4 | 2678 | 5.57 | 157.4 | 33.3 |

| Sample 4 | 131.6 | 6.74 | 38.5 | 2191 | 2.85 | 104.6 | 31.8 |

Another important question was whether RNA amplification was reproducible between different samples. The Affymetrix microarrays have a large signal range, and the signal of the different genes is distributed along the entire range. However, for individual genes, particularly those that are not expected to change among samples, the signal intensities should remain similar among arrays. To assess this, we compared the signals for the same housekeeping genes that we used for qPCR normalization. As shown in Table 3, Cyclo A and UBC had relatively high signals; β-actin and GAPDH had intermediate signals; and TOP1, EIF4A4 and Calnexin had relatively low signals. However, the genes with high signal intensity were high in all the samples, and the same happened with the genes with medium or low signal (Table 3). Therefore, overall, the quality controls show that the cRNA amplified from LCM-captured cells are suitable for microarray analysis.

Table 3. Microarray expression of the housekeeping genes.

The signal intensities for each one of the housekeeping genes tested were in a similar range across all the arrays, thus supporting the reproducibility of the RNA amplification.

| Cyclo A | UBC | β-actin | GAPDH | TOP1 | EIF4A2 | Calnexin | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Average Signal | 10801 | 11129 | 6707 | 6143 | 1247 | 1466 | 1866 |

| Maximum | 11576 | 11778 | 7250 | 7209 | 1489 | 1780 | 2263 |

| Minimum | 10164 | 10210 | 6465 | 5162 | 1051 | 1236 | 1651 |

| SD | 655 | 686 | 365 | 864 | 181 | 228 | 272 |

Discussion

Atherosclerosis, the most prevalent underlying pathology of cardiovascular diseases, is a complex multifactorial process [25,26]. Mouse models of atherosclerosis are widely used to study atherosclerosis. In fact, if we search in PUBMED “atherosclerosis and mice” we can find over 4000 articles. However, the small size of mice, and therefore of their lesions, and the cellular heterogeneity of the atherosclerotic lesions, severely limit the application of analyses that are otherwise commonly used in biomedical research, such as measuring gene and protein expression, thus impeding the generation of information from the study of atherosclerosis in mice.

LCM enables us to examine specific gene expression from individual cell types in heterogeneous tissues, and Trogan et al.[7] showed that this is a good approach to analyze gene expression in macrophages from atherosclerotic lesions of apoE−/− mice. However, the low amount of RNA that can be isolated from LCM-captured cells limits the number of genes that can be analyzed. We asked whether we could amplify the RNA to obtain sufficient amounts to perform a genome-wide expression profiling in macrophage-rich areas of atherosclerotic lesions using microarrays in the same mouse model. The fidelity of the T7 polymerase-mediated linear amplification of RNA from microscopic samples has been confirmed in multiple studies [10,27,28]. We obtained a large amount of cRNA after two rounds of IVT. The cRNA passed the standard quality controls, but we wanted to ensure that the amplification process did not change the relative abundance levels of various messages found in the original cellular RNA. Therefore, we used qPCR to validate the gene expression differences seen on microarrays. We compared gene expression in cRNA amplified from macrophage-rich areas of lesions or from whole aorta and showed that, compared aortic cRNA, the cRNA from lesions is greatly enriched in markers of macrophage/foam cells, but is depleted of markers of SMC, the most abundant cells in the arterial wall. Furthermore, when we performed microarray hybridizations with 4 different cRNAs from lesions, we found a high %P, that the most commonly used parameters used for microarray quality control were within the normal range, and, most importantly, that the signals for all the housekeeping genes tested were in a similar range in all the arrays, in support of a similar amplification for all independently obtained samples. Importantly, the amplification process does not seem to be associated with very large variations, which would have made the data interpretation difficult.

In conclusion, in this study we show that LCM and subsequent amplification of RNA allow a comprehensive study of gene expression in macrophage-rich areas of atherosclerotic lesions. The ample amount of cRNA obtained after amplification indicates that this technique can also be used to study other cell populations, such as SMC and endothelial cells. Future applications of LCM in the study of atherosclerosis in mice could also include proteomics analysis, that have already been used in human atherosclerotic plaque [29,30], and cell signaling. In conclusion, we believe that the analysis of LCM-captured cells by microarray and other analytic technology represents an important addition to our technical arsenal that will help unravel the mechanistic intricacies of atherosclerotic development.

Acknowledgments

We thank Dr. Lisa White, Laura Liles and other members of the Microarray Core Facility at Baylor College of Medicine for their help in sample processing and discussion. This work was supported by a Scientist Development Grant from the American Heart Association (to AP) and a grant from the National Institutes of Health HL051586 (to LC).

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Reference List

- 1.Rosamond Wayne, Flegal Katherine, Friday Gary, Furie Karen, Go Alan, Greenlund Kurt, Haase Nancy, HO Michael, Howard Virginia, Kissela Bret, Kittner Steven, Lloyd-Jones Donald, McDermott Mary, Meigs James, Moy Claudia, Nichol Graham, O'Donnell Christopher J, Roger Veronique, Rumsfeld John, Sorlie Paul, Steinberger Julia, Thom Thomas, Wasserthiel-Smoller Sylvia, Hong Yuling American Heart Association Statistics Committee and Stroke Statistics Subcommittee. Heart Disease and Stroke Statistics--2007 Update: A Report From the American Heart Association Statistics Committee and Stroke Statistics Subcommittee. Circulation. 2007;115:e69–e171. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.106.179918. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Breslow Jan L. Mouse Models of Atherosclerosis. Science. 1996;272:685–688. doi: 10.1126/science.272.5262.685. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Meir Karen S, Leitersdorf Eran. Atherosclerosis in the Apolipoprotein E-Deficient Mouse: A Decade of Progress. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 2004;24:1006–1014. doi: 10.1161/01.ATV.0000128849.12617.f4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Reddick RL, Zhang SH, Maeda N. Atherosclerosis in mice lacking apo E. Evaluation of lesional development and progression. Arterioscler.Thromb. 1994;14:141–147. doi: 10.1161/01.atv.14.1.141. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Palinski W, Ord VA, Plump AS, Breslow JL, Steinberg D, Witztum JL. ApoE-deficient mice are a model of lipoprotein oxidation in atherogenesis. Demonstration of oxidation-specific epitopes in lesions and high titers of autoantibodies to malondialdehyde-lysine in serum. Arterioscler Thromb. 1994;14:605–616. doi: 10.1161/01.atv.14.4.605. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Espina Virginia, Wulfkuhle Julia D, Calvert Valerie S., VanMeter Amy, Zhou Weidong, Coukos George, Geho David H, Petricoin Emanuel F, Liotta Lance A. Laser-capture microdissection. Nat.Protocols. 2006;1:586–603. doi: 10.1038/nprot.2006.85. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Trogan Eugene, Choudhury Robin P, Dansky Hayes M, Rong James X, Breslow Jan L, Fisher Edward A. Laser capture microdissection analysis of gene expression in macrophages from atherosclerotic lesions of apolipoprotein E-deficient mice. PNAS. 2002;99:2234–2239. doi: 10.1073/pnas.042683999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Seo David, Wang Tao, Dressman Holly, Herderick Edward E, Iversen Edwin S, Dong Chunming, Vata Korkut, Milano Carmelo A, Rigat Fabio, Pittman Jennifer, Nevins Joseph R, West Mike, Goldschmidt-Clermont Pascal J. Gene Expression Phenotypes of Atherosclerosis. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 2004;24:1922–1927. doi: 10.1161/01.ATV.0000141358.65242.1f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Luzzi Veronica, Holtschlag Victoria, Watson Mark A. Expression Profiling of Ductal Carcinoma in Situ by Laser Capture Microdissection and High-Density Oligonucleotide Arrays. Am J Pathol. 2001;158:2005–2010. doi: 10.1016/S0002-9440(10)64672-X. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.King Chialin, Guo Ning, Frampton Garrett M, Gerry Norman P, Lenburg Marc E, Rosenberg Carol L. Reliability and Reproducibility of Gene Expression Measurements Using Amplified RNA from Laser-Microdissected Primary Breast Tissue with Oligonucleotide Arrays. J Mol Diagn. 2005;7:57–64. doi: 10.1016/S1525-1578(10)60009-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Luo L, Salunga RC, Guo H, Bittner A, Joy KC, Galindo JE, Xiao H, Rogers KE, Wan JS, Jackson MR, Erlander MG. Gene expression profiles of laser-captured adjacent neuronal subtypes. Nat Med. 1999;5:117–122. doi: 10.1038/4806. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Paul Antoni, Ko Kerry WS, Li Lan, Yechoor Vijay, McCrory Mark A, Szalai Alexander J, Chan Lawrence. C-Reactive Protein Accelerates the Progression of Atherosclerosis in Apolipoprotein E-Deficient Mice. Circulation. 2004;109:647–655. doi: 10.1161/01.CIR.0000114526.50618.24. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Dobson AT, Raja R, Abeyta MJ, Taylor T, Shen S, Haqq C, Pera RA. The unique transcriptome through day 3 of human preimplantation development. Hum.Mol Genet. 2004;13:1461–1470. doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddh157. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Tangirala RK, Rubin EM, Palinski W. Quantitation of atherosclerosis in murine models: correlation between lesions in the aortic origin and in the entire aorta, and differences in the extent of lesions between sexes in LDL receptor-deficient and apolipoprotein E-deficient mice. J Lipid Res. 1995;36:2320–2328. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Rozen S, Skaletsky H. Primer3 on the WWW for general users and for biologist programmers. Methods Mol.Biol. 2000;132:365–386. doi: 10.1385/1-59259-192-2:365. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Vandesompele Jo, De Preter Katleen, Pattyn Filip, Poppe Bruce, Van Roy Nadine, De Paepe Anne, Speleman Frank. Accurate normalization of real-time quantitative RT-PCR data by geometric averaging of multiple internal control genes. Genome Biology. 2002;3 doi: 10.1186/gb-2002-3-7-research0034. research0034-research0034. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Copois Virginie, Bibeau Frederic, Bascoul-Mollevi Caroline, Salvetat Nicolas, Chalbos Patrick, Bareil Corinne, Candeil Laurent, Fraslon Caroline, Conseiller Emmanuel, Granci Virginie, Maziere Pierre, Kramar Andrew, Ychou Marc, Pau Bernard, Martineau Pierre, Molina Franck, del Rio Maguy. Impact of RNA degradation on gene expression profiles: Assessment of different methods to reliably determine RNA quality. Journal of Biotechnology. 2007;127:549–559. doi: 10.1016/j.jbiotec.2006.07.032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Taylor TB, Nambiar PR, Raja R, Cheung E, Rosenberg DW, Anderegg B. Microgenomics: Identification of new expression profiles via small and single-cell sample analyses. Cytometry A. 2004;59:254–261. doi: 10.1002/cyto.a.20051. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Mahoney WM, Schwartz SM. Defining smooth muscle cells and smooth muscle injury. J Clin.Invest. 2005;115:221–224. doi: 10.1172/JCI24272. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kunjathoor VV, Febbraio M, Podrez EA, Moore KJ, Andersson L, Koehn S, Rhee JS, Silverstein R, Hoff HF, Freeman MW. Scavenger receptors class A-I/II and CD36 are the principal receptors responsible for the uptake of modified low density lipoprotein leading to lipid loading in macrophages. J Biol Chem. 2002;277:49982–49988. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M209649200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Oram John F, Lawn Richard M. ABCA1: the gatekeeper for eliminating excess tissue cholesterol. J.Lipid Res. 2001;42:1173–1179. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Larigauderie Guilhem, Furman Christophe, Jaye Michael, Lasselin Catherine, Copin Corinne, Fruchart Jean Charles, Castro Graciela, Rouis Mustapha. Adipophilin Enhances Lipid Accumulation and Prevents Lipid Efflux From THP-1 Macrophages: Potential Role in Atherogenesis. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 2004;24:504–510. doi: 10.1161/01.ATV.0000115638.27381.97. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Wodicka L, Dong H, Mittmann M, Ho MH, Lockhart DJ. Genome-wide expression monitoring in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Nat Biotechnol. 1997;15:1359–1367. doi: 10.1038/nbt1297-1359. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Shou J, Qian HR, Lin X, Stewart T, Onyia JE, Gelbert LM. Optimization and validation of small quantity RNA profiling for identifying TNF responses in cultured human vascular endothelial cells. J Pharmacol.Toxicol.Methods. 2006;53:152–159. doi: 10.1016/j.vascn.2005.02.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Libby Peter, Theroux Pierre. Pathophysiology of Coronary Artery Disease. Circulation. 2005;111:3481–3488. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.105.537878. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Ross R. Atherosclerosis--an inflammatory disease. N.Engl.J.Med. 1999;340:115–126. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199901143400207. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Upson JJ, Stoyanova R, Cooper HS, Patriotis C, Ross EA, Boman B, Clapper ML, Knudson AG, Bellacosa A. Optimized procedures for microarray analysis of histological specimens processed by laser capture microdissection. J Cell Physiol. 2004;201:366–373. doi: 10.1002/jcp.20073. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Kabbarah O, Pinto K, Mutch DG, Goodfellow PJ. Expression profiling of mouse endometrial cancers microdissected from ethanol-fixed, paraffin-embedded tissues. Am J Pathol. 2003;162:755–762. doi: 10.1016/S0002-9440(10)63872-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Lawrie LC, Curran S, McLeod HL, Fothergill JE, Murray GI. Application of laser capture microdissection and proteomics in colon cancer. Mol Pathol. 2001;54:253–258. doi: 10.1136/mp.54.4.253. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Bagnato Carolina, Thumar Jaykumar, Mayya Viveka, Hwang Sun Il, Zebroski Henry, Claffey Kevin P, Haudenschild Christian, Eng Jimmy K, Lundgren Deborah H, Han David K. Proteomics Analysis of Human Coronary Atherosclerotic Plaque: A Feasibility Study of Direct Tissue Proteomics by Liquid Chromatography and Tandem Mass Spectrometry. Mol Cell Proteomics. 2007;6:1088–1102. doi: 10.1074/mcp.M600259-MCP200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]