Abstract

Paired immunoglobulin-like receptors of activating (PIR-A) and inhibitory (PIR-B) isoforms are expressed by many hematopoietic cells including B lymphocytes and myeloid cells. To determine the functional roles of PIR-A and PIR-B in primary bacterial infection, PIR-B-deficient (PIR-B-/-) and wild-type (WT) control mice were injected intravenously with an attenuated strain of Salmonella enterica Typhimurium (WB335). PIR-B-/- mice were found to be more susceptible to Salmonella infection than WT mice as evidenced by high mortality rate, high bacterial loads in the liver and spleen, and a failure to clear bacteria from the circulation. While blood levels of major cytokines and Salmonella-specific antibodies were mostly comparable in the two groups of mice, distinct patterns of inflammatory lesions were found in their livers at 7- to 14-d post-infection: diffuse spreading along the sinusoids in PIR-B-/- mice versus nodular restricted localization in WT mice. PIR-B-/- mice have more inflammatory cells in the liver but fewer B cells and CD8+ T cells in the spleen than WT mice at 14-d post-infection. PIR-B-/- bone marrow-derived macrophages (BMMφ) failed to control intracellular replication of Salmonella in vitro, in part due to inefficient phagosomal oxidant production, when compared with WT BMMφ. PIR-B-/- BMMφ also produced more nitrite and TNFα upon exposure to Salmonella than WT BMMφ. These findings suggest that the disruption of PIR-A and PIR-B balance affects their regulatory roles in host defense to bacterial infection.

Introduction

During the last decade, many genes have been identified that encode novel pairs of immunoreceptors which have similar ectodomains but function to produce opposing signals (1,2). The pairing of activating and inhibitory receptors is thought to be necessary for the initiation, amplification and termination of immune responses. Paired Ig-like receptors of activating (PIR-A) and inhibitory (PIR-B) isoforms in rodents are among the earliest paired receptors (3,4). PIR-A associates non-covalently with the Fc receptor common γ chain, a transmembrane signal transducer containing immunoreceptor tyrosine-based activation motifs in the cytoplasmic tail, to form a cell activation complex (5-8). In contrast, PIR-B contains three functional immunoreceptor tyrosine-based inhibitory motifs in its cytoplasmic tail, which negatively regulate cellular activity via SHP-1 and SHP-2 tyrosine phosphatases (9-12). PIR-A and PIR-B are expressed by many hematopoietic cell types, including B cells, dendritic cells (DC), monocyte/macrophages, neutrophils, eosinophils, mast cells and megakaryocyte/platelets (7,12,13). PIR are not expressed by T cells, NK cells and erythrocytes, a feature that distinguishes mouse PIR from the human PIR homologs leukocyte Ig-like receptors (LILR) (originally called the Ig-like transcripts, monocyte-macrophage Ig-like receptors or CD85) some of which are expressed by T cells and NK cells as well (14-17). PIR is also expressed by lymphoid progenitors committed to differentiation to T cells, NK cells and DC, but not to B-lineage cells, suggesting a complex pattern of PIR expression during hematopoietic differentiation (18). In addition to the hematopoietic cells, it has been recently shown that PIR-B is expressed by neurons throughout the brain using in situ hybridization and protein blot analyses (19).

Several interesting findings regarding the PIR ligands and disruption of the Pirb gene (PIR-B-/-) have been demonstrated (20). Like human LILR, both PIR-B and PIR-A react in surface plasmon resonance assays with various MHC class I molecules at relatively high affinity (21). Furthermore, the interaction between PIR and MHC class I is found to occur at cis (i.e., on the same cell) and not at trans (i.e., between different cells; ref. (22). In addition to endogenous MHC class I, both PIR-B and PIR-A are found to recognize cell wall components of both Gram-positive Staphylococcus aureus and Gram-negative Escherichia coli, suggesting multiple ligand recognition by PIR (23). While PIR-B-/- mice exhibit normal T- and B-cell development except for slightly higher levels of peritoneal B-1 cells, PIR-B-/- B cells are hyper-responsive upon BCR ligation. PIR-B-/- mice show significantly augmented IgG1 and IgE responses to T-cell dependent antigens and produce more IL-4 and IFNγ than wild-type control mice, suggesting an enhanced Th2 response attributable to the immaturity of PIR-B-/- DC (24). PIR-B-/- mice also exhibit an exaggerated graft-versus-host (GVH) reaction, possibly due to the interaction between PIR-A on PIR-B-/- DC and allogeneic MHC class I on donor T cells that leads to increased production of IFNγ, a critical cytokine in lethal GVH as well as to increased proliferation of cytotoxic T cells (21). PIR-B-/- phagocytic cells are also shown to be hyper-responsive to integrin ligation (25,26). In the present study we have determined the influence of PIR-B deficiency on the pathogenesis of Salmonella infection in mice.

Materials and Methods

Mice

C57BL/6 mice and RAG-2-deficient mice on a C57BL/6 background (RAG-2-/-) were purchased from the Jackson Laboratory. PIR-B-/- mice on a C57BL/6 background were generated by one of us (TT; ref. 23) and were bred and maintained in filter-topped isolator cages at our animal facility. PIR-B-/- mice were backcrossed with C57BL/6 mice for at least nine generations. All animals of both sexes were used at 6-12 wk of age. All studies involving animals were conducted in accordance with and after approval of the University of Alabama at Birmingham Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee.

Bacterial strain, preparation and inoculation

WB335, an LT2 strain of Salmonella enterica serovar Typhimurium (S. typhimurium) attenuated due to a spontaneous mutation of rpoS, an RNA polymerase sigma factor (27,28), was used in the present studies. This attenuated strain was used since C57BL/6 mice are hyper-susceptible to wild-type Salmonella (27,28). WB335 was stored at -80°C and a single colony of WB335 from a blood agar plate was picked to LB broth and grown to an O.D. of 0.5 at 600 nm and the resultant bacterial suspensions were frozen in the presence of 10% glycerol at -80°C as frozen infection stocks. For all infection experiments, the bacterial dose of frozen stocks was reevaluated by thawing a vial and plating onto LB agar plates one day before inoculation. Based on this estimation, enough vials to obtain needed CFU were thawed, washed in pyrogen-free, sterile Ringer's solution (Abbot Lab, Chicago, IL), resuspended in the desired concentrations of bacteria and injected in a 200 μl of volume into the lateral tail vein of mice. The numbers of inoculated bacteria were confirmed by CFU plate counts. The survival status of WB335-infected mice was monitored at least twice a day during the course of infection. In some experiments, WB335 (4 × 108 CFU) were heat-killed by incubating at 60°C for 30 min, labeled with Alexa Fluor 488 fluorochrome (Invitrogen) according to the manufacturer's instructions and stored at -80°C, prior to use for phagocytic assays.

Enumeration of bacteria in organs

To determine the bacterial loads in blood and major organs (liver, spleen, kidneys and lungs), the blood was drawn into a heparin-coated syringe by cardiac puncture from mice euthanized with CO2 and the organs were removed aseptically and weighed. Serial dilutions of a blood aliquot in cold sterile Ringer's solution were plated on blood agar plates (Becton Dickinson Microbiology System, NJ) and incubated at 37°C overnight. The remaining blood samples were subjected to centrifugation at 3000 rpm for 10 min at 4°C for plasma preparation. A portion of each removed organ was weighed and homogenized in 1 ml of cold sterile Ringer's solution and 50 μl aliquots of the homogenate and its serial dilutions were plated on blood agar plates. Visible CFU were determined after overnight incubation at 37°C and the bacterial load was expressed as CFU per the entire organ.

Assays for cytokines and antibodies

The concentrations of cytokines (TNFα, IFNγ and IL-10) in plasma were determined by using specific ELISA kits purchased from Pierce Biotechnology according to the manufacturer's instructions. The titers of Salmonella-specific antibodies of IgM, IgG and IgA classes in the plasma collected on day 14 from infected mice were determined by ELISA. Briefly, 96-well flat bottom plates were pre-coated with 100 μl of heat-killed WB335 suspension (108 CFU/ml) by centrifugation at 1,500 rpm for 15 min at 4°C, washed, blocked with 1% BSA/0.1% Tween 20 in PBS and incubated sequentially with serial dilutions of plasma samples and with AP-labeled goat antibodies specific for mouse IgM, IgG or IgA [Southern Biotechnology Associates (SBA), Birmingham, AL] prior to incubation with the substrate p-nitrophenyl phosphate solution as described previously (29). A pool of normal mouse sera and antisera were used as standards and the results were expressed as the fold-increase over the normal sera.

Histopathological and immunohistological analyses

A portion of each organ removed from each WB335-infected mouse was fixed in neutral buffered, 10% formalin (Sigma) for at least one day, dehydrated, embedded in paraffin, sectioned and stained with hematoxylin and eosin for histopathological analysis. Another portion of each organ was embedded in OCT compound, snap-frozen in liquid nitrogen, cut in 4 – 6 μm thickness with a cryostat, fixed in acetone and rehydrated in PBS. Sections were incubated with appropriately diluted rabbit antisera against WB335 before developing with FITC-labeled goat anti-rabbit Ig antibody without cross-reactivity to mouse Ig (SBA). The immunostained tissue sections were examined under a Leica/Leitz DMRB fluorescence microscope equipped with appropriate filter cubes (Chroma Technology, Battleboro, VT). Images were acquired with a C5810 series digital color camera (Hamamatsu Photonic System, Bridgewater, NJ). Images were processed with Adobe Photo Shop and IP LAB Spectrum software (Signal Analytics Software, Vienna, VA).

Immunofluorescence analysis of cells

Liver and splenic tissues were removed during the course of infection at the indicated days and cut into small pieces before digestion with 0.1% collagenase (Sigma)/0.1% DNase I in HBSS containing 5% FCS. The resultant liver cell suspension was first centrifuged at 700 rpm for 2 min at 4°C to remove hepatocytes and then at 1200 rpm for 10 min. The cell pellets were resuspended in HBSS/5% FCS, overlaid onto Percoll gradient (2 ml of cell suspension/6 ml of 25% Percoll/4 ml of 50% Percoll), and centrifuged at 800 × g for 30 min at 4°C, before collecting the mononuclear cells (MNC) at the 25%/50% interface. Erythrocytes in the collagenase-treated splenic cell suspension were lysed in 0.15 M ammonium chloride buffer at pH 7.4. Both cell suspensions were passed through nylon meshes to remove tissue debris and subjected to cell surface immunostaining as described previously (7). Briefly, cells were first incubated with Ab93 mAb (rat γ2aλ isotype) to block the FcγRII/III (30) and then with the following reagents: FITC- or PE-labeled mAbs specific for mouse CD4 (H129.19, rat γ2a), CD8 (53-6.7, rat γ2a), CD11c (HL3, hamster γ1) or CD11b (M1/70, rat γ2b), which were purchased from BD Bioscience Pharmingen (San Diego, CA), PE-labeled rat anti-mouse PIR mAb (6C1, rat γ1κ; ref. 7), or biotin-labeled rat mAbs specific for mouse CD19 (1D3, γ2a) (BD Pharmingen) or liver sinusoidal endothelial cell (LSEC; ME-9F1, γ2a) (Miltenyi Biotec, Auburn, CA). Streptavidin-allophycocyanin was used as a developing reagent for biotinylated mAbs. Rat anti-mouse endoglin/CD105 mAb (clone 209701, γ2a) purchased from R & D Systems (Minneapolis, MN) was labeled with Alexa Fluoro 488 (Invitrogen Molecular Probe). The controls included the isotype-matched irrelevant mAbs labeled with the corresponding fluorochromes or biotin. The stained cells were analyzed by the FACScalibur™ or FACSort™ flow cytometer with CELLQuest™ software (BD).

Phagocytosis assay

Bone marrow cells were obtained from the femurs of PIR-B-/- and wild-type (WT) C57BL/6 mice of the same age and sex. After lysing erythrocytes, bone marrow cells were cultured at 3 × 106 cells/ml in RPMI 1640 containing 10% FCS and 10% M-CSF conditioned medium, the culture supernatant of the CMG1 cell line which was transfected with mouse M-CSF cDNA and was kindly provided by Dr. Eric Brown (UCSF, San Francisco, CA), for 3 days. After removing non-adherent cells, the adherent cells were cultured in the above fresh medium for additional two days and harvested to be used as bone-marrow-derived macrophages (BMMφ). BM polymorphonuclear leukocytes (PMN) were enriched by centrifugation at 1,200 × g for 30 min at 25°C over Percoll gradients (3 ml of cell suspension/3 ml of 62% Percoll/3 ml of 81% Percoll). BMMφ or BMPMN were incubated with the heat-killed, Alexa 488-labeled, opsonized WB335 at different ratios of bacteria/cell numbers from 10/1 to 1/10 for 30 min with shaking at 37°C. All opsonization procedures in this study were performed using normal fresh mouse sera. After quenching the fluorescence of the extracellular WB335 with Trypan blue at the final concentration of 125 μg/ml, the intracellular fluorescence of phagocytosed WB335 was assessed by FACSort™ (31,32).

Intracellular killing assay

For in vitro infection, exponential phase WB335 bacteria, which were opsonized and resuspended in DMEM containing 10% FCS without antibiotics, were added in triplicate at various multiplicity of infection (MOI) into 96-well plates containing 3 × 105 BMMφ or BMPMN per well, centrifuged briefly, and incubated at 37°C for 25 min under 5% CO2 prior to addition of gentamicin at the final concentration of 100 μg/ml to kill the extracellular WB335 for 1 hr. After replacing the media with DMEM/10% FCS containing gentamicin (10 μg/ml), infected cells were cultured for another 2 or 24 hrs, washed, and lysed in 100 μl Triton X-100 prior to CFU plate counts (33).

Assays for superoxide, nitrite and TNFα release

BMMφ (5 × 105 cells) or BMPMN (5 × 105 cells) were resuspended in 250 μl of HBSS containing 10 mM HEPES, 0.5 mM CaCl2, 1 mM MgCl2 and 120 μM cytochrome C, plated in triplicate into polypropylene tubes, and stimulated with or without live serum-opsonized WB335 at various MOI or 162 nM PMA for 2 hrs (for BMMφ) or 15 min (for BMPMN) in 37°C shaking water-bath. The respiratory burst reaction as measured by the cytochrome C reduction was stopped by incubation on an ice bath for 10 min, followed by centrifugation at 2,000 rpm for 5 min at 4°C and assessment of the supernatant absorbance at 550 nm. The OD values were converted to the nmoles of the reduced cytochrome C by using the extinction coefficient of E550 nm = 2.1 × 104 M-1cm-1 (34). For nitrite production, BMMφ (105 cells) or BMPMN (5 × 105 cells) were plated in triplicate into 96-well plates and stimulated with or without heat-killed opsonized WB335 at different concentrations or LPS (1 μg/ml) for 48 hrs (for BMMφ) or 24 hrs (for BMPMN), before collection of the supernatants. The concentration of nitrite in the resultant culture supernatants was measured as an index of nitric oxide synthase activity by the Griess Reagent system (100 − 1.56 μM for sensitivity; Promega) according to the manufacturer's instructions. For TNFα release, BMMφ (2 × 105 cells) and BMPMN (5 × 105 cells) were plated in triplicate into 24-well and 96-well plates, respectively, and stimulated for 24 hrs with heat-killed opsonized WB335 at the bacteria/cells ratio of 10. The TNFα in the culture supernatants was measured by ELISA as described above.

Phagosomal oxidant production

The above assay determines primarily extracellular superoxide as the 12 kDa cytochrome C molecule is likely excluded from interior of the cell due to its size (35). To determine oxidant production inside the phagosome (36,37), heat-killed WB335 bacteria (109 cells) were labeled with the oxidant sensitive fluorescent dye OxyBURST Green H2DCFDA (2′,7′-dichlorodihydrofluorescein diacetate; Molecular Probes) according to the manufacturer's instructions. Labeled bacteria were washed twice, resuspended in PBS and opsonized prior to incubation with BMMφ at different ratios of bacteria/BMMφ numbers for 2 hs at 37°C with shaking. After stopping the reaction by incubation iced bath for 10 min, the fluorescence of BMMφ that engulfed H2DCFDA-WB335 bacteria was analyzed by FACSort.

Statistical analysis

Data are recorded as the mean ± 1 SD. Differences in group survival were analyzed using Mantel Cox Logrank p test. All other simple comparisons were performed with Student's t test, with p ≤ 0.05 considered to represent statistical significance.

Results

PIR-B-/- mice are more susceptible to Salmonella infection than WT mice

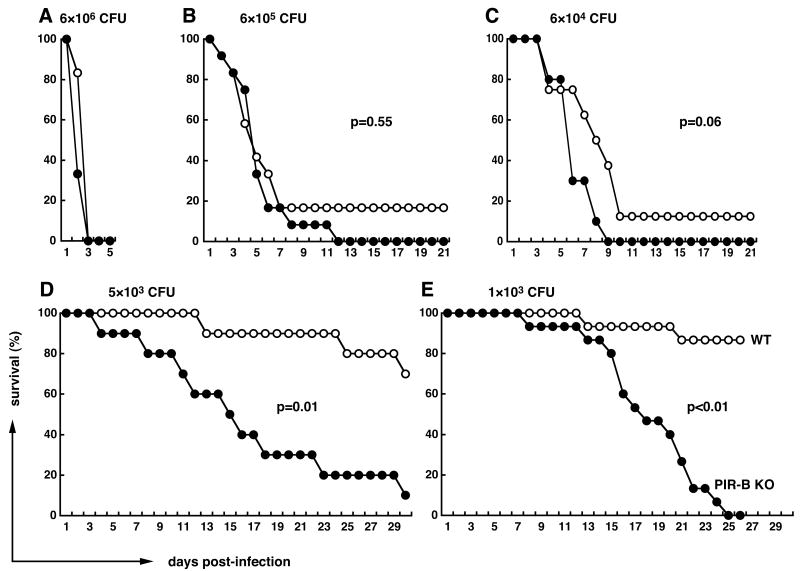

To determine the role of PIR-B in the bacterium/host interaction, we employed the Salmonella enteric fever mouse model. S. typhimurium is known as a Gram-negative, facultative intracellular pathogen capable of replication both outside and inside host cells. The WB335 strain of S. typhimurium, which has a mutation of RNA polymerase sigma factor (rpoS) resulting in attenuated virulence in susceptible strains of mice such as C57BL/6 (27,28), was selected for this purpose. Both PIR-B-/- and WT C57BL/6 mice of the same age and sex were infected intravenously with various doses of the attenuated WB335 organisms (103 to 6 × 106 CFU/mouse) in a group of 10 - 15 mice per each dose and their survival status was monitored for three to four weeks after infection. When inoculated with the high dose of bacteria (6 × 106 CFU/mouse), both groups of mice died within 3 days post-infection (Fig. 1A). When injected with 10- or 100-fold fewer bacteria, all PIR-B-/- mice and most WT mice died within two weeks after infection (Figs. 1B and 1C). However, a small proportion (10 – 20%) of the WT mice survived for the entire three week test period. A more striking survival difference was observed in the mouse groups receiving lower doses of bacteria (≤ 5 × 103 CFU/mouse). With one exception, PIR-B-/- mice receiving 5 × 103 CFU died over a 4-wk period starting at 4-d post-infection, whereas many control mice survived during this time period (Fig. 1D). Furthermore, many of the infected PIR-B-/- mice showed signs of morbidity much sooner than the infected WT mice during the course of infection. When inoculated with 103 CFU/mouse, most PIR-B-/- mice survived for the first two weeks but started to die in the third week which resulted in a much sharper slope of the mortality curve than that with 5 × 103 CFU (Fig. 1E). Most WT mice survived during this 4-wk period. Although these survival experiments were conducted using male mice, the same results were also obtained with female mice, indicating no sexual differences in the susceptibility to Salmonella infection of PIR-B-/- mice (not shown). Notably, when the RAG-2-/- mice, which are totally deficient in mature T and B cells, were infected with the same WB335 strain at 5 × 103 CFU/mouse, all five mice survived for the first 14 days after infection and then died during the next two days, suggesting that similar to other strains of S. typhimurium, both innate and adaptive immunity are important for full protection against infection with the attenuated WB335 strain (not shown). Collectively, these findings indicate that PIR-B-/- mice are more susceptible than WT mice to infection with S. typhimurium.

Figure 1. Survival of mice from Salmonella infection.

Age-matched, PIR-B-/- (●) and WT (○) C57BL/6 male mice (N=12 for A and B, N=10 for C and D, and N=15 for E) were infected intravenously with the indicated doses of attenuated strain (WB335) of S. typhimurium and survival was monitored for 21 to 30 days. The y axis indicates survival (%) and the x axis indicates days after infection.

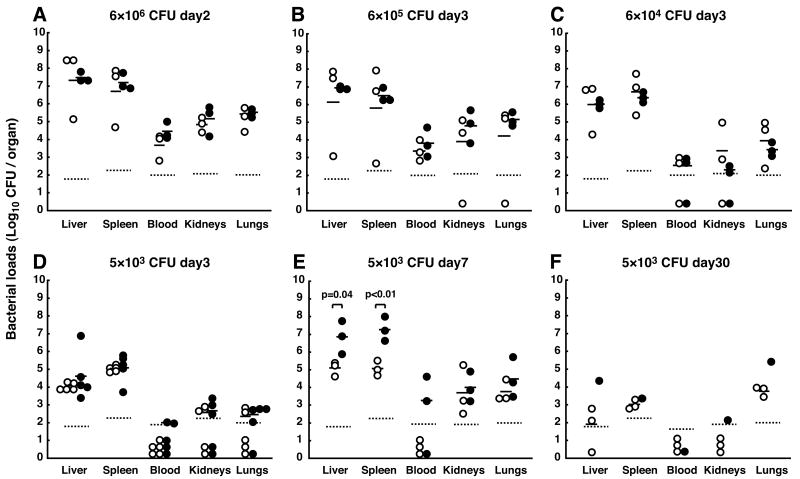

PIR-B-/- mice are incapable of controlling bacteria replication in vivo

To determine the tissue localization of inoculated bacteria, three to five mice in each dose group were sacrificed during the course of infection and the bacterial loads in various organs were assessed. In mice receiving higher doses of bacteria (>6 × 104 CFU/mouse), both PIR-B-/- and WT mice exhibited similar high bacterial burdens at 2- and 3-d post-infection in all tissues examined including the blood (Figs. 2A-2C). By contrast, in mice receiving low doses of bacteria (5 × 103 CFU), PIR-B-/- mice were found to have more bacteria than WT mice in the liver and spleen at 7-d post-infection (Fig. 2E). Furthermore, the bacterial burden in those tissues of PIR-B-/- mice reached ∼5 × 107 CFU, close to the maximum number of bacteria recovered from live mice. Bacteremia was detected at 3-d (2/5 mice) and 7-d (2/3 mice) post-infection in PIR-B-/- mice, but not in WT mice, consistent with the high mortality of PIR-B-/- mice. In the one PIR-B-/- mouse that survived for the entire 30-d period, bacteria were undetectable in the blood (Fig. 2F). These findings suggest that the high susceptibility of PIR-B-/- mice to Salmonella infection is associated with a failure to control bacterial replication in target organs.

Figure 2. Bacterial titers in various tissues of mice infected with S. typhimurium WB335.

PIR-B-/- (●) and WT (○) mice were infected intravenously with the indicated CFU of WB335 organisms. Three (A to C, E, F) or five (D) mice were sacrificed at the indicated days after infection except for one PIR-B-/-mouse at 30-day post-infection. The bacterial loads (CFU) in the indicated tissues were assessed as described in Materials and Methods. The Log10 values of WB335 CFU per organ represent individual mice. The geometric mean values are indicated (−) and the detection limits are indicated (····). The total blood volume (ml) was determined as one thirteenth of the body weight (gm).

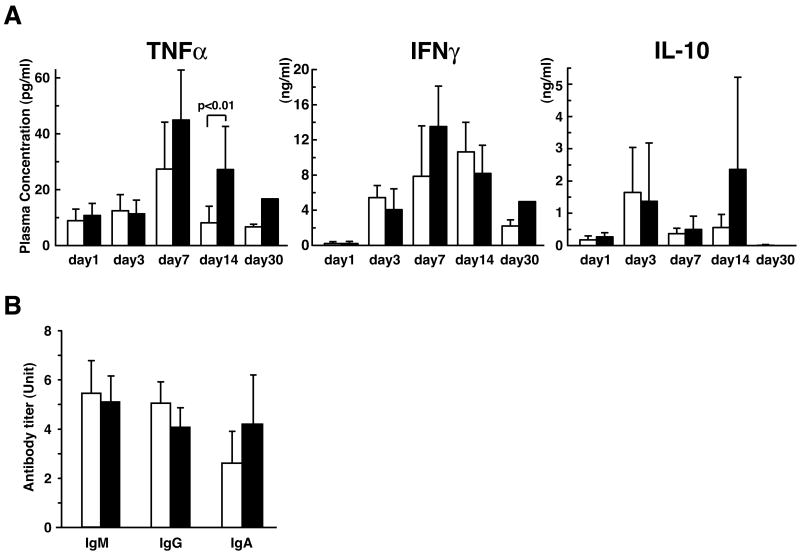

Mostly comparable blood levels of cytokines and antibodies in both groups of mice

The ability of Salmonella to survive and/or replicate inside macrophages is depend on the activation state of the host cells that are affected by host cytokines. To determine the role of cytokines in the susceptibility of PIR-B-/- mice to Salmonella infection, we determined the plasma levels of representative proinflammatory (TNFα and INFγ) and anti-inflammatory (IL-10) cytokines during the course of infection by ELISA. The concentrations of these cytokines in the blood of infected animals were indistinguishable between PIR-B-/- and WT mice, except for the TNFα level at 14-d post-infection where PIR-B-/- mice showed significantly higher than WT mice (Fig. 3A). Notably, there was a large standard deviation of the concentrations of IL-10 in PIR-B-/- mice at 14-d post-infection, suggesting considerable individual variability among the six mice examined. Since antibody is shown to be important for full protection against Salmonella infection, we measured the titer of antibodies to the WB335 strain in the plasma at 14-d post-infection. The titers of three major classes of anti-Salmonella antibodies did not differ significantly between PIR-B-/- and WT control mice (Fig. 3B). Thus, blood levels of cytokines and antibodies could not be the explanation for the susceptibility of PIR-B-/- mice to infection with Salmonella.

Figure 3. Plasma levels of cytokines and antibodies in mice infected with S. typhimurium WB335.

Plasma were prepared from PIR-B-/- (■) or WT (□) mice at the indicated days after infection with WB335 (5 × 103 CFU) and subjected to the assessments of cytokines (A) and anti-Salmonella antibody titers (B). Results are expressed as arithmetic means ± SD from five to six mice at day 1, five to ten mice at days 3 and 7, six to fifteen mice at day 14, and three WT mice and one PIR-B-/- mouse at day 30. The anti-Salmonella antibodies in plasma samples from the infected animals are expressed as the fold increase over the value obtained from pooled uninfected plasma.

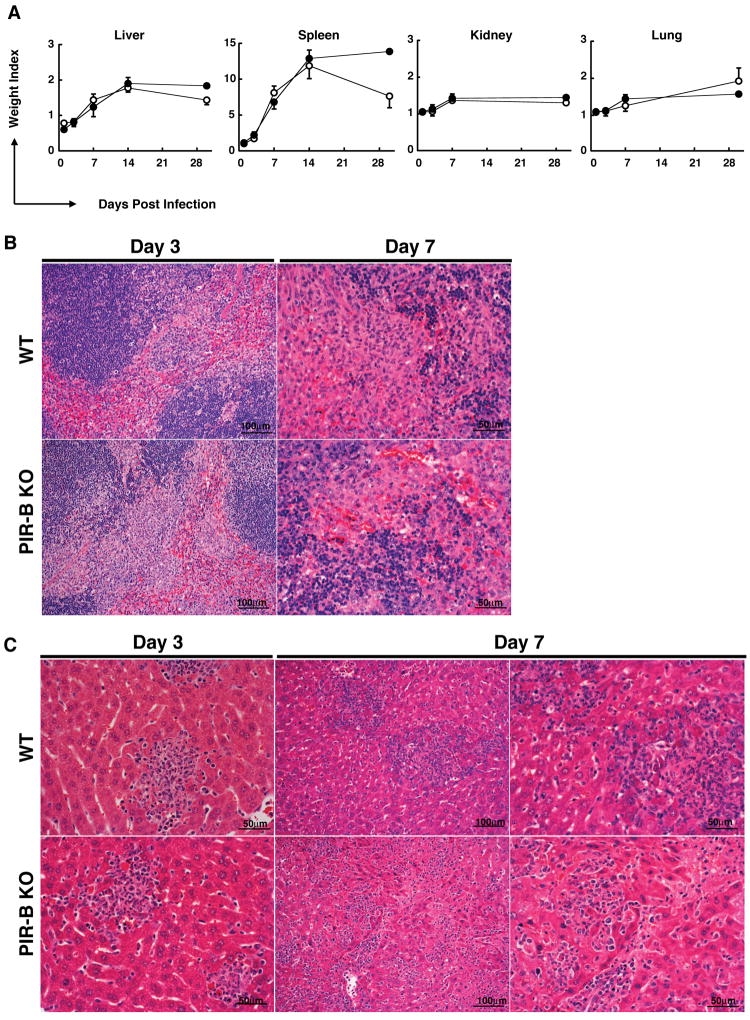

Distinct patterns of inflammatory foci and bacteria spreading in liver between PIR-B-/- and WT mice

To obtain further insight into the progression of Salmonella infection in PIR-B-/- and WT mice, we examined the histology of the major organs. Macroscopically, as expected, the spleen size markedly increased following infection and the extent of splenomegaly was comparable in both groups of mice except at 30-d post-infection. The sizes of other organs after infection were also comparable in both groups (Fig. 4A). Microscopically, the white pulp in the spleen was markedly expanded at 1-d post-infection. Numerous nodular inflammatory foci called typhoid nodules, which were characterized by cellular aggregates of PMN (in early stage) and macrophages (in later stage), were scattered predominantly in the red pulp at day 3 of both the WT and PIR-B-/- mice. By day 7, in addition to numerous granulomatous typhoid nodules, we observed the obliteration of follicular margins and the marked proliferation of sinus lining cells and sinus macrophages in both groups of mice (Fig. 4B). These granulomatous typhoid nodules and histological changes in the sinus were still prominent at 14-d and 30-d post-infection in both groups.

Figure 4. Pathological changes in mice infected with S. typhimurium WB335.

(A) PIR-B-/- (●) and WT (○) mice infected with WB335 Salmonella (5 × 103 CFU) were sacrificed at the indicated days of post-infection and the weight index of each organ was estimated as: (the organ weight from infected animals(÷) the organ weight from uninfected animals). Results are expressed as arithmetic means ± SD. (B and C) H&E staining of spleen and liver at 3-d and 7-d post-infection with 5 × 103 CFU.

In the liver, small typhoid nodules consisting of PMN and Kupffer cells or macrophages were visible in hepatic lobules as early as 1-d post-infection and their incidence increased in the next six days in both groups of mice. Quite distinctive pathological changes were observed, however, at 7-d post-infection. In the WT mice, the inflammatory cellular lesions were localized and exhibited nodular distribution, whereas in the PIR-B-/- mice, in addition to granulomatous typhoid nodules, inflammatory mononuclear cells infiltrated along the sinusoids, resulting in a spreading pattern and the dilatation of sinusoidal spaces accompanied with narrowing of hepatic cords (Fig. 4C). These sinusoidal changes were still observed in most of the PIR-B-/- mice (4/5), but only in a minority of the WT mice (1/5) at 14-d post-infection. At 30-d post-infection the inflammatory foci, including the granulomatous typhoid nodules, became smaller and infrequent in WT mice, but were still frequently observed along with mild sinusoidal infiltration in the surviving PIR-B-/- mouse, indicating that the effects of Salmonella infection were more readily controlled in the WT mice than in the PIR-B-/- mice. In addition to the above changes, fibrin deposition, thrombosis formation and parenchymal necrosis were also observed in both groups after 3-d post-infection.

To determine the bacterial distribution in livers, we performed immunofluorescence analysis using Salmonella-specific antibodies. Salmonella were found more diffusely along the sinusoids in PIR-B-/-mice, but were more localized in the WT mice (not shown), consistent with the patterns of inflammatory cellular infiltration on H&E-stained slides. In lungs and kidneys, interstitial inflammatory cell infiltration was observed in both groups after 7-d post-infection. Collectively, these findings suggest that while the splenic histological changes following Salmonella infection are indistinguishable between the PIR-B-/-and WT mice, the liver exhibits quite distinctive inflammatory lesions with diffuse spreading along the sinusoids in PIR-B-/- mice versus nodular localization in WT mice.

Salmonella-infected PIR-B-/- mice have more inflammatory cells in liver, but fewer B cells and CD8+ T cells in spleen than WT infected mice

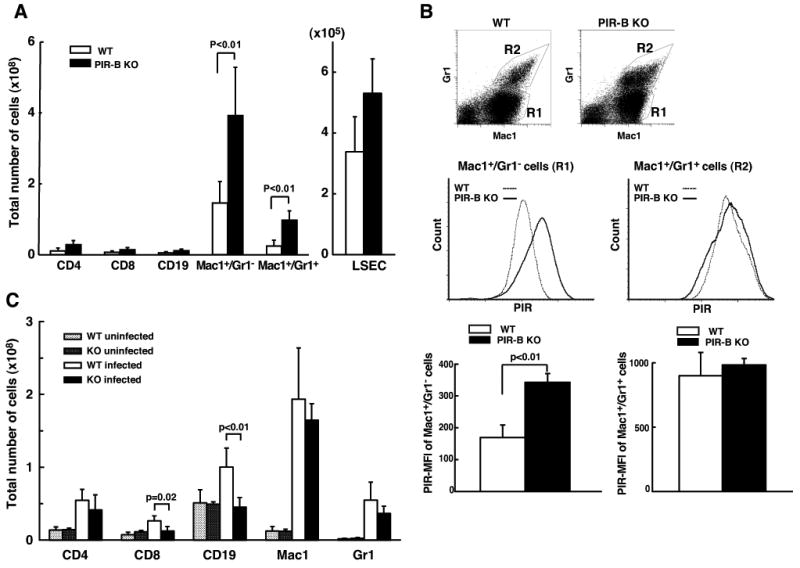

Since the histological changes of liver were evident at 7-d post-infection (see Fig. 4C), we examined by flow cytometry the infiltrating cells, resident Kupffer cells and sinusoidal endothelial cells in the 7-d liver samples. As shown in Fig. 5A, the total numbers of Mac-1+/Gr-1- macrophage/Kupffer cells and of Mac-1+/Gr-1+ PMN in the liver are two to three folds increased in PIR-B-/- mice in compared with WT mice.The cell surface PIR levels were also compared among these cell populations using the 6C1 mAb which recognizes both PIR-A and PIR-B. The surface PIR-A level in the PIR-B-/- macrophage/Kupffer cell, but not PMN, population was enhanced two folds in comparison with the surface PIR-A and PIR-B levels in the WT cell populations, indicating in turn the enhanced expression of PIR-A on PIR-B-/-macrophage/Kupffer cells (Fig. 5B). The total numbers of CD4+ T cells, CD8+ T cells and CD19+ B cells in the liver were comparable in both groups of mice. Despite the pathological findings of bacterial spreading along the liver sinusoids in PIR-B-/- mice, the sinusoidal endothelial cell population defined by the expression of endoglin/CD105 and LSEC antigen was also indistinguishable between the PIR-B-/- and WT mice.

Figure 5. Immunofluorescence analysis of liver mononuclear cells and splenocytes from mice infected with S. typhimurium.

(A) Liver MNC from PIR-B-/- (■) or WT (□) mice at 7-d post-infection with WB335 (5 × 103 CFU) were incubated with fluorochrome-labeled mAbs specific for the indicated antigens as well as with isotype-matched control mAbs before analysis with FACSort™ flow cytometer. Results are expressed as total number of cells with the indicated phenotype per liver from four different mice in each group. Note two to three fold increase in the number of Mac-1+/Gr-1- Mφ/Kupffer cells and of Mac-1+/Gr-1+ PMN in PIR-B-/- mice in compared with WT mice. (B) Gates of Mac-1+/Gr-1- (R1) and Mac-1+/Gr-1+ (R2) cell populations in WT and PIR-B-/- mice (top panel). Cell surface PIR intensity on the population of Mac-1+/Gr-1- Mφ/Kupffer cells (left) and of Mac-1+/Gr-1+ PMN (right) from PIR-B-/-(solid histogram) and WT (open histogram) mice (middle panel). MFI of PIR on Mφ/Kupffer cells (left) and PMN (right) in WT (□) and PIR-B-/- (■) mice (bottom panel). Note two-fold increase of cell surface PIR intensity on PIR-B-/- Mφ/Kupffer cells. (C) Splenic MNC from PIR-B-/- (■) or WT (□) mice at 14-d post-infection with WB335 (5 × 103 CFU) or from uninfected PIR-B-/- (

) or WT (

) or WT (

) mice were similarly examined for the indicated cell populations by immunofluorescence. Results are expressed as mean ± SD of the total number of cells per spleen from five different mice in each group. Note no significant increase in the number of CD19+ B cells and CD8+ T cells in PIR-B-/- mice after Salmonella infection.

) mice were similarly examined for the indicated cell populations by immunofluorescence. Results are expressed as mean ± SD of the total number of cells per spleen from five different mice in each group. Note no significant increase in the number of CD19+ B cells and CD8+ T cells in PIR-B-/- mice after Salmonella infection.

In spleen, the total numbers of CD19+ B cells, CD4+ T cells, CD8+ T cells, Mac-1+ macrophages, GR-1+ PMN and CD11c+ dendritic cells were comparable between PIR-B-/- and WT mice at 7-d post-infection (not shown). At 14-d post-infection, however, the number of CD19+ B cells and, to a lesser extent, of CD8+ T cells in PIR-B-/- mice did not increase as markedly as in WT mice after Salmonella infection (Fig. 5C). As expected, Mac-1+ macrophages and Gr-1+ PMN were markedly increased in both groups of mice. Other cell subsets were comparable in both groups of mice. Collectively, these findings suggest that systemic infection of Salmonella results in i) more inflammatory infiltrating cells in liver and/or Kupffer cell reactions, ii) enhanced expression of PIR-A by macrophage/Kupffer cells and iii) insufficient increase of splenic B cells and CD8+ T cells in PIR-B-/- mice.

PIR-B-/- macrophages are unable to control intracellular Salmonella growth ex vivo

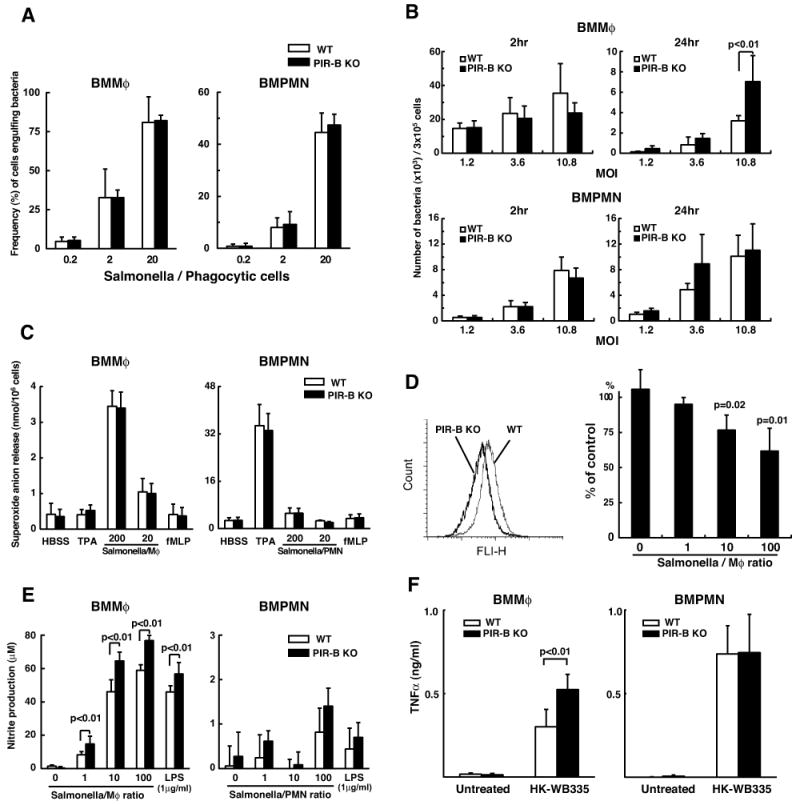

To explore the cellular basis for high susceptibility of PIR-B-/- mice to Salmonella infection, bone marrow-derived macrophages (BMMφ) and PMN (BMPMN) from PIR-B-/- and WT mice were examined for their in vitro responses to WB335 bacteria. The ability to engulf fluorochrome-labeled, heat-killed WB335 by BMMφ and BMPMN was comparable between PIR-B-/- and WT mice at different ratios of bacteria/phagocytic cells (Fig. 6A). Upon in vitro infection with live WB335, bacterial replication in BMPMN was indistinguishable in both groups of mice at both 2- and 24-h post-infection at different MOI. In the PIR-B-/- BMMφ, however, more bacterial growth was evident at 24-h post-infection with a high MOI (i.e., 10.8) when compared to WT BMMφ. These results show that PIR-B-/- BMMφ are unable to control intracellular Salmonella replication, consistent with the in vivo findings (Fig. 6B). The extracellular superoxide anion release by phagocytes from WT and PIR-B-/- mice upon in vitro infection with heat-killed (not shown) or live WB335 or stimulation with TPA or fMLP was similar (Fig. 6C). However, oxidant production inside the phagosome engulfing WB335 was clearly diminished in PIR-B-/-BMMφ compared with WT BMMφ (Fig. 6D). Unlike BMMφ, the phagosomal oxidation in BMPMN was indistinguishable between WT and PIR-B-/- mice (not shown). It should be noted that similar reduction in phagosomal oxidation by PIR-B-/- BMMφ was also observed with other heat-killed microorganisms (e.g., E. coli, S. pneumonia, S. aureus and C. albicans), suggesting a generalized phenomenon related to the PIR-B-deficient macrophages and not to a particular pathogen (not shown). These findings are thus consistent with the inability of PIR-B-/- macrophages to control intracellular bacterial growth.

Figure 6. Ex vivo functions of phagocytes from PIR-B-/- and WT mice.

(A) Phagocytic activity. BMMφ (left) and BMPMN (right) from PIR-B-/- (■) and WT (□) mice were incubated with heat-killed, Alexa 488-labeled, opsonized WB335 at the indicated ratios of bacteria/phagocytic cells. After quenching the extracellular fluorescence, the intracellular fluorescence of engulfed WB335 was determined by flow cytometry. (B) Bactericidal activity. Phagocytes described in A were infected with live opsonized WB335 bacteria at the indicated MOI, and the number of intracellular bacteria was enumerated by CFU plate counts at the indicated time periods. (C-F) Cells described in A were incubated with the indicated stimuli and the superoxide anion release (C), the nitrite production (E) and the TNFα production (F) were assessed as described in Materials and Methods. For phagosomal oxidant production (D), BMMφ from PIR-B-/- and WT mice were incubated with oxidant sensitive dye-labeled WB335 bacteria at the indicated ratios and the fluorescence of BMMφ engulfing the dye-labeled WB335 was analyzed by FACSort. A typical profile at the Salmonella/BMMφ ratio of 100 is shown (left panel) and the values of [100 × (MFI of PIR-B-/- BMMφ/MFI of WT BMMφ)] at different ratios are plotted (right panel). Results are expressed as means ± SD from three different experiments.

PIR-B-/- BMMφ were also found to produce more nitrite than the WT BMMφ when exposed to heat-killed WB335 at different ratios of bacteria/phagocytes (Fig. 6E). This was also observed with LPS stimulation. Unlike BMMφ, the BMPMN irrespective of the mouse genotype did not produce significant amounts of nitrites by either WB335 or LPS stimulation. Furthermore, the PIR-B-/- BMMφ were found to produce more TNFα upon exposure to the heat-killed WB355 than the WT BMMφ (Fig. 6F). In contrast, BMPMN produced comparable amounts of TNFα upon stimulation with heat-killed WB335. Collectively, these findings suggest that PIR-B-/- macrophages are unable to control the intracellular growth of Salmonella, but are hyper-responsive to the heat-killed Salmonella as evidenced by enhanced production of nitrite and TNFα ex vivo.

Discussion

Using a mouse model of Salmonella infection with an attenuated strain of S. typhimurium (WB335) we showed that PIR-B-/- mice were more susceptible to Salmonella infection than the WT mice as evident by increased mortality rate, high bacterial loads in the liver and spleen and a failure to clear bacteria from the circulation. The blood levels of cytokines (TNFα, IFNγ and IL-10) and Salmonella-specific antibodies (IgM, IgG and IgA) were mostly comparable between these two groups of mice. However, distinct bacterial spreading patterns were notable in the liver at 7- to 14-d post-infection; a diffuse spreading along the sinusoids was observed in PIR-B-/- mice versus a nodular restricted localization in WT mice. PIR-B-/-mice had more inflammatory cells in the liver, but fewer B cells and CD8+ T cells in the spleen than WT mice. These in vivo differences were substantiated by the ex vivo findings where BMMφ in PIR-B-/- mice failed to control intracellular replication of Salmonella due to inefficient phagosomal oxidant production compared with those in WT mice. PIR-B-/- BMMφ also produced more nitrite and TNFα upon exposure to Salmonella than control macrophages.

While PIR-A and PIR-B are among first paired receptors with opposing signaling capabilities to be identified, there are now more than 20 such related immunoreceptors reported, implying that the paring of activation and inhibition is essential modulators for initiation, amplification and termination of immune responses (1,2). Since PIR is expressed by many hematopoietic cell types (B cells, monocyte/macrophages, DC, PMN, mast cells and megakaryocyte/platelets), it has been postulated that the disruption of PIR-A and PIR-B balance may affect their regulatory roles in host defense, including humoral immune, inflammatory, antigen-presenting, allergic and coagulative responses. Indeed, several functional alterations have been reported for the PIR-B-/- mice. These include i) hyper-reactivity of B cells to BCR ligation and to T cell independent antigens (24), ii) enhanced Th2 response due to immature dendritic cells (24), iii) exaggerated GVH reactions when sublethally irradiated PIR-B-/- mice receive allogeneic splenocytes (21), and iv) hyper-responsiveness of macrophages and PMN to integrin ligation ex vivo (25,26). When we initially set up the present experiments, it was difficult for us to anticipate what the outcomes would be. The expected enhanced inflammatory responses in the PIR-B-/- mice would render them more resistant to Salmonella infection. On the other hand, their diminished ability to attenuate the inflammatory reactions might have pathological sequelae.

We have now shown that the PIR-B-/- mice are more susceptible to the primary infection of WB335 than the WT control mice. Interestingly, the slopes of the morbidity curves of 5 × 103 versus 103 CFU dose are different; in the former higher dose PIR-B-/- mice died gradually beginning at day 4 post-infection over the next 3 weeks, whereas in the latter lower dose most PIR-B-/- mice survived for two weeks but began to die in the third week post-infection, similar to Rag-2-/- mice receiving 5 × 103 CFU/mouse. It has been shown that the innate immune system can restrict replication of S. typhimurium to a certain degree, but that acquired immunity is essential for effective control and eradication of bacteria (38-40). These survival data suggest that the disruption of the Pirb gene affects both innate and acquired immunity to a primary infection with S. typhimurium.

The high susceptibility of PIR-B-/- mice to Salmonella infection appears to be associated with their inability to control bacteria replication in target organs as evidenced by (i) high bacterial loads in the liver, spleen and lung tissues, (ii) diffuse spreading pattern of bacteria along the liver sinusoids, (iii) failure to efficiently clear bacteria from circulation, and (iv) more intracellular bacterial growth inside the marrow-derived macrophages ex vivo. It has recently been shown that PIR-B can recognize S. aureus as well as some Gram-negative bacteria such as H. pylori and E. coli, suggesting that PIR-B may recognize pathogen-associated molecular patterns (23). In this regard, we found by immunofluorescence that neither PIR-B nor PIR-A could directly bind live or heat-killed WB335 (S. Oka, et al, unpublished). PIR-B-/- and WT phagocytes ingested opsonized WB335 and subsequently released superoxide anion into culture supernatants at comparable levels. It has been shown that Salmonella survive and replicate in phagocytes within unique Salmonella-containing vacuoles (SCV) inaccessible to the host defense mechanisms (41-43). Delayed acidification of SCV and their incomplete fusion with lysosomes are thought to promote intracellular survival of Salmonella in these vacuoles. Phagosomal oxidant production by PIR-B-/- macrophages was indeed less than by WT macrophages. This reduced production of oxidants may permit increased replication of bacteria inside PIR-B-/- macrophages and leads to be inability to control Salmonella replication in the reticuloendothelial system of PIR-B-/- mice.

The precise mechanism by which the PIR-B deficiency leads to reduction of phagosomal oxidation is presently unknown. However, the extracellular superoxide release by both macrophages and PMN and the phagosomal oxidation by PMN were comparable between PIR-B-/- and WT mice, suggesting that the assembly and activation processes of the NADPH oxidase subunits might not be impaired in PIR-B-deficient phagocytes. It should also be noted that heat-killed bacteria were used for phagosomal oxidation assays because the live bacteria could not be labeled with an oxidation-sensitive dye; hence, the evading strategies of Salmonella from host defense could be excluded from our consideration of the mechanism. Furthermore, the reduced phagosomal oxidation in PIR-B-deficient macrophages was a generalized phenomenon as observed with several other heat-killed microorganisms. Collectively, the processes of phagosomal development and subsequent oxidant production appear to be indirectly impaired by disruption of the PIR-A and PIR-B balance in macrophages, possibly through differences in the phagocytosing cellular status, the stimuli via multiple phagocytic receptors, the cytokine milieu and the time after onset of exposure to pathogens. Alternatively, PIR-B may have a dual function of both inhibitory and activating activities as suggested by the presence of an additional SH2-binding motif called the immunoreceptor tyrosine-based switch motif (ITSM) “T/SxYxxV/I” (where x represents any amino acid) (44). In this regard, it has recently been shown that while PIR-B negatively regulates the eotaxin-dependent eosinophil chemotaxis by recruiting the SHP-1 protein tyrosine phosphatase, PIR-B also positively regulates the leukotriene B4-induced eosinophil chemotaxis by recruiting activating kinases (JAK1, JAK2, Shc and Crk) (13). It is thus conceivable that PIR-B may recruit some kinases, such as Src family kinases, Syk, and PI3 kinase p85 known to be involved in activation of NADPH oxidase (45,46), through its ITSM during phagocytosis of bacteria.

Another clear difference in Salmonella infected animals is the distinct patterns of inflammatory lesions in the liver after infection. While in WT mice such lesions were more localized and exhibited nodular distribution, in PIR-B-/- mice inflammatory cells infiltrated diffusely along the sinusoids and exhibited a spreading pattern. PIR-B-/- mice also had more macrophages and PMN in the liver than WT mice as determined by flow cytometry. These differences were observed as early as 7-d post-infection. Notably, the cell surface PIR-A levels on PIR-B-/- macrophages, but not PMN, were enhanced two fold in compared with those on WT macrophages which were contributed by PIR-A and PIR-B. In our previous study, cell surface levels of PIR on WT splenic B cells and macrophages were found to be up-regulated by ∼33% after LPS stimulation for 3 days in vitro (7). The observed enhancement of surface PIR-A levels seen in Salmonella-infected PIR-B-/- mice might result from long exposure to Salmonella, leading to dysregulated macrophage responses against bacterial infection. The more production of NO and TNFα by these PIR-B-/- macrophages may have detrimental, rather than protective, effects locally on the surrounding hepatic tissues. Similar association of enhanced PIR-A expression with enhanced host reaction was also demonstrated in DC populations of PIR-B-/- mice that develop an exaggerated acute GVH reaction (21). One of the unique features of PIR is that PIR-B on resting B cells, DC and myeloid cells is constitutively tyrosine-phosphorylated by Src family tyrosine kinases (Lyn or Fgr and Hck) and associates constitutively with tyrosine phosphatases (SHP-1 and SHP-2), thereby restraining potential cellular activation via BCR, integrin and chemokine receptors (25,26,47,48). This tonic inhibition is apparently absent in PIR-B-/- mice and the present studies clearly indicate that the disruption of PIR-A and PIR-B balance also affects their regulatory roles in host defense to bacterial infection.

The finding that the total numbers of splenic B cells and, to a lesser extent, CD8+ T cells in PIR-B-/-mice did not increase as markedly as those in WT mice at 14-d post-infection was unexpected. Sepsis or endotoxemia is known to accelerate lymphocyte apoptosis in both animals and humans (49,50). In our studies, LPS-induced apoptosis was frequently observed in the splenic white pulp of PIR-B-/-, but not WT, mice and B cells appeared to be more prone to this cell death (I. Torii, et al., unpublished). It is thus reasonable to suggest that PIR-B deficiency leads to increased sensitivity of B cells to LPS-induced apoptosis during Salmonella infection. Since T cells do not express PIR, the inability of PIR-B-/- mice to increase CD8+ T cells two weeks after Salmonella infection results most likely from an indirect effect of PIR-B deficiency.

The molecular mechanisms of resistance and susceptibility to Salmonella infection are extremely complex and multifactorial with host innate and adaptive immune responses versus with Salmonella virulence factors or evading systems. Inbred strains of mice vary considerably in resistance or susceptibility to Salmonella infection and several major resistance genes have been identified in mice (51). These include (i) MHC class I and II, (ii) natural resistance associated macrophage protein, (iii) TLR4, (iv) Bruton's tyrosine kinase, (v) LPS-binding protein and CD14, (vi) NADPH oxidase and inducible NO synthase, and (vii) cytokines (TNFα, INFγ). Many immunodeficient mouse strains are also unable to control the in vivo replication of attenuated Salmonella strains. For example, T cell deficient nu/nu, MHC class II-/-, TCRβ-/-, INFγR-/-, TNFα p55R-/-, CD28-/-, CD40L/CD154-/- and MD-2-/-, mice all succumb to infection with attenuated strains of Salmonella that are normally eradicated in WT mice (52-58). PIR-A and PIR-B are one of the family members of paired immunoreceptors which share similar ectodomains but exhibit opposing signaling capabilities and are postulated based on their wide cellular distribution to play important regulatory roles in host defense. Here, we show clear evidence that the balance of PIR-A and PIR-B functional activities is important for immune responses to bacterial infection.

Acknowledgments

We thank Ms. J. Yvette Hale, Ms. Janice D. King, Mr. Dong-Won Kang and Ms. Lisa Jia for their excellent technical assistance; Dr. Eric J. Brown for providing CMG1 cell line; Dr. Melissa Swiecki for technical advice, Drs. Richard B. Johnston, Jr., Sasada Masataka, Victor Darley-Usmar, and Louis B. Justement for helpful discussions and suggestions, and Ms. Jacquelin B. Bennett for manuscript preparation.

Abbreviations used in this paper

- BMMφ

bone marrow-derived macrophages

- BMPMN

bone marrow polymorphonuclear leukocytes

- DC

dendritic cells

- GVH

graft-versus host

- ITSM

immunoreceptor tyrosine-based switch motif

- LILR

leukocyte Ig-like receptors

- LSEC

liver sinusoidal endothelial cell

- MFI

mean fluorescence intensity

- MNC

mononuclear cells

- MOI

multiplicity of infection

- PIR-A

paired Ig-like receptors of activating isoform

- PIR-B

paired Ig-like receptor of inhibitory isoform

- SCV

Salmonella-containing vacuoles

Footnotes

This work was in part supported by National Institutes of Health grants AI14782 (J.F.K.), AI21548 (D.E.B.), AI42127 (H.K.). I.T. was an overseas Research Scholar of the Ministry of Education, Culture, Sports, Science and Technology in Japan.

Author Contributions: I.T. and M.H. initiated this study and developed the in vivo results (Figs. 1 and 2). Serological (Fig. 3) and histological analyses (Fig. 4) were performed by S.O. and I.T. and by I.T and H.K., respectively. S.O. performed the flow cytometric analysis (Fig. 5), the ex vivo studies (Fig. 6) and the statistical evaluation. T.T provided PIR-B-/- mice. J.F.K. conducted the immunohistochemical analysis. W.H.B., D.E.B. and H.K. designed the research and H.K. wrote the paper.

Disclosure: The authors have no financial conflicts of interests.

References

- 1.Ravetch JV, Lanier LL. Immune inhibitory receptors. Science. 2000;290:84–89. doi: 10.1126/science.290.5489.84. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Lanier LL. Face off - the interplay between activating and inhibitory immune receptors. Curr Opin Immunol. 2001;13:326–331. doi: 10.1016/s0952-7915(00)00222-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kubagawa H, Burrows PD, Cooper MD. A novel pair of immunoglobulin-like receptors expressed by B cells and myeloid cells. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1997;94:5261–5266. doi: 10.1073/pnas.94.10.5261. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Hayami K, Fukuta D, Nishikawa Y, Yamashita Y, Inui M, Ohyama Y, Hikida M, Ohmori H, Takai T. Molecular cloning of a novel murine cell-surface glycoprotein homologous to killer cell inhibitory receptors. J Biol Chem. 1997;272:7320–7327. doi: 10.1074/jbc.272.11.7320. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Maeda A, Kurosaki M, Kurosaki T. Paired immunoglobulin-like receptor (PIR)-A is involved in activating mast cells through its association with Fc receptor γ chain. J Exp Med. 1998;188:991–995. doi: 10.1084/jem.188.5.991. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Yamashita Y, Ono M, Takai T. Inhibitory and stimulatory functions of paired Ig-like receptor (PIR) family in RBL-2H3 cells. J Immunol. 1998;161:4042–4047. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kubagawa H, Chen CC, Ho LH, Shimada TS, Gartland L, Mashburn C, Uehara T, Ravetch JV, Cooper MD. Biochemical nature and cellular distribution of the paired immunoglobulin-like receptors, PIR-A and PIR-B. J Exp Med. 1999;189:309–318. doi: 10.1084/jem.189.2.309. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Taylor LS, McVicar DW. Functional association of FcεRIγ with arginine632 of paired immunoglobulin-like receptor (PIR)-A3 in murine macrophages. Blood. 1999;94:1790–1796. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Bléry M, Kubagawa H, Chen CC, Vély F, Cooper MD, Vivier E. The paired Ig-like receptor PIR-B is an inhibitory receptor that recruits the protein-tyrosine phosphatase SHP-1. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1998;95:2446–2451. doi: 10.1073/pnas.95.5.2446. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Maeda A, Kurosaki M, Ono M, Takai T, Kurosaki T. Requirement of SH2-containing protein tyrosine phosphatases SHP-1 and SHP-2 for paired immunoglobulin-like receptor B (PIR-B)-mediated inhibitory signal. J Exp Med. 1998;187:1355–1360. doi: 10.1084/jem.187.8.1355. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Maeda A, Scharenberg AM, Tsukada S, Bolen JB, Kinet JP, Kurosaki T. Paired immunoglobulin-like receptor B (PIR-B) inhibits BCR-induced activation of Syk and Btk by SHP-1. Oncogene. 1999;18:2291–2297. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1202552. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Uehara T, Blery M, Kang DW, Chen CC, Ho LH, Gartland GL, Liu FT, Vivier E, Cooper MD, Kubagawa H. Inhibition of IgE-mediated mast cell activation by the paired Ig-like receptor PIR-B. J Clin Invest. 2001;108:1041–1050. doi: 10.1172/JCI12195. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Munitz A, McBride ML, Bernstein JS, Rothenberg ME. A dual activation and inhibition role for the paired immunoglobulin-like receptor B in eosinophils. Blood. 2008;111:5694–5703. doi: 10.1182/blood-2007-12-126748. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Colonna M, Nakajima H, Navarro F, Lopez-Botet M. A novel family of Ig-like receptors for HLA class I molecules that modulate function of lymphoid and myeloid cells. J Leukoc Biol. 1999;66:375–381. doi: 10.1002/jlb.66.3.375. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Cosman D, Fanger N, Borges L. Human cytomegalovirus, MHC class I and inhibitory signalling receptors: more questions than answers. Immunol Rev. 1999;168:177–185. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-065x.1999.tb01292.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Long EO. Regulation of immune responses through inhibitory receptors. Annu Rev Immunol. 1999;17:875–904. doi: 10.1146/annurev.immunol.17.1.875. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Wilson MJ, Torkar M, Haude A, Milne S, Jones T, Sheer D, Beck S, Trowsdale J. Plasticity in the organization and sequences of human KIR/ILT gene families. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2000;97:4778–4783. doi: 10.1073/pnas.080588597. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Masuda K, Kubagawa H, Ikawa T, Chen CC, Kakugawa K, Hattori M, Kageyama R, Cooper MD, Minato N, Katsura Y, Kawamoto H. Prethymic T-cell development defined by the expression of paired immunoglobulin-like receptors. EMBO J. 2005;24:4052–4060. doi: 10.1038/sj.emboj.7600878. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Syken J, Grandpre T, Kanold PO, Shatz CJ. PirB restricts ocular-dominance plasticity in visual cortex. Science. 2006;313:1795–1800. doi: 10.1126/science.1128232. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Takai T. A novel recognition system for MHC Class I molecules constituted by PIR. Adv Immunol. 2005;88:161–192. doi: 10.1016/S0065-2776(05)88005-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Nakamura A, Kobayashi E, Takai T. Exacerbated graft-versus-host disease in Pirb-/-mice. Nat Immunol. 2004;5:623–629. doi: 10.1038/ni1074. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Masuda A, Nakamura A, Maeda T, Sakamoto Y, Takai T. Cis binding between inhibitory receptors and MHC class I can regulate mast cell activation. J Exp Med. 2007;204:907–920. doi: 10.1084/jem.20060631. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Nakayama M, Underhill DM, Petersen TW, Li B, Kitamura T, Takai T, Aderem A. Paired Ig-like receptors bind to bacteria and shape TLR-mediated cytokine production. J Immunol. 2007;178:4250–4259. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.178.7.4250. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Ujike A, Takeda K, Nakamura A, Ebihara S, Akiyama K, Takai T. Impaired dendritic cell maturation and increased TH2 responses in PIR-B-/- mice. Nat Immunol. 2002;3:542–548. doi: 10.1038/ni801. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Pereira S, Zhang H, Takai T, Lowell CA. The inhibitory receptor PIR-B negatively regulates neutrophil and macrophage integrin signaling. J Immunol. 2004;173:5757–5765. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.173.9.5757. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Zhang H, Meng F, Chu CL, Takai T, Lowell CA. The Src family kinases Hck and Fgr negatively regulate neutrophil and dendritic cell chemokine signaling via PIR-B. Immunity. 2005;22:235–246. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2005.01.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Benjamin WH, Jr, Yother J, Hall P, Briles DE. The Salmonella typhimurium locus mviA regulates virulence in Itys but not Ityr mice: functional mviA results in avirulence; mutant (nonfunctional) mviA results in virulence. J Exp Med. 1991;174:1073–1083. doi: 10.1084/jem.174.5.1073. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Swords WE, Cannon BM, Benjamin WH., Jr Avirulence of LT2 strains of Salmonella typhimurium results from a defective rpoS gene. Infect Immun. 1997;65:2451–2453. doi: 10.1128/iai.65.6.2451-2453.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Kiyotaki M, Cooper MD, Bertoli LF, Kearney JF, Kubagawa H. Monoclonal anti-Id antibodies react with varying proportions of human B lineage cells. J Immunol. 1987;138:4150–4158. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Oliver AM, Grimaldi JC, Howard MC, Kearney JF. Independently ligating CD38 and FcγRIIB relays a dominant negative signal to B cells. Hybridoma. 1999;18:113–119. doi: 10.1089/hyb.1999.18.113. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Loike JD, Silverstein SC. A fluorescence quenching technique using trypan blue to differentiate between attached and ingested glutaraldehyde-fixed red blood cells in phagocytosing murine macrophages. J Immunol Methods. 1983;57:373–379. doi: 10.1016/0022-1759(83)90097-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Wan CP, Park CS, Lau BH. A rapid and simple microfluorometric phagocytosis assay. J Immunol Methods. 1993;162:1–7. doi: 10.1016/0022-1759(93)90400-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Chakravortty D, Hansen-Wester I, Hensel M. Salmonella pathogenicity island 2 mediates protection of intracellular Salmonella from reactive nitrogen intermediates. J Exp Med. 2002;195:1155–1166. doi: 10.1084/jem.20011547. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Johnston RB, Jr, Keele BB, Jr, Misra HP, Lehmeyer JE, Webb LS, Baehner RL, RaJagopalan KV. The role of superoxide anion generation in phagocytic bactericidal activity: studies with normal and chronic granulomatous disease leukocytes. J Clin Invest. 1975;55:1357–1372. doi: 10.1172/JCI108055. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Huycke MM, Joyce W, Wack MF. Augmented production of extracellular superoxide by blood isolates of Enterococcus faecalis. J Infect Dis. 1996;173:743–746. doi: 10.1093/infdis/173.3.743. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Rakita RM, Vanek NN, Jacques-Palaz K, Mee M, Mariscalco MM, Dunny GM, Snuggs M, Van Winkle WB, Simon SI. Enterococcus faecalis bearing aggregation substance is resistant to killing by human neutrophils despite phagocytosis and neutrophil activation. Infect Immun. 1999;67:6067–6075. doi: 10.1128/iai.67.11.6067-6075.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Steinckwich N, Frippiat JP, Stasia MJ, Erard M, Boxio R, Tankosic C, Doignon I, Nusse O. Potent inhibition of store-operated Ca2+ influx and superoxide production in HL60 cells and polymorphonuclear neutrophils by the pyrazole derivative BTP2. J Leukoc Biol. 2007;81:1054–1064. doi: 10.1189/jlb.0406248. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Jones BD, Falkow S. Salmonellosis: host immune responses and bacterial virulence determinants. Annu Rev Immunol. 1996;14:533–561. doi: 10.1146/annurev.immunol.14.1.533. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Mittrucker HW, Kaufmann SH. Immune response to infection with Salmonella typhimurium in mice. J Leukoc Biol. 2000;67:457–463. doi: 10.1002/jlb.67.4.457. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Ravindran R, McSorley SJ. Tracking the dynamics of T-cell activation in response to Salmonella infection. Immunology. 2005;114:450–458. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2567.2005.02140.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Buchmeier NA, Heffron F. Inhibition of macrophage phagosome-lysosome fusion by Salmonella typhimurium. Infect Immun. 1991;59:2232–2238. doi: 10.1128/iai.59.7.2232-2238.1991. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Rathman M, Barker LP, Falkow S. The unique trafficking pattern of Salmonella typhimurium-containing phagosomes in murine macrophages is independent of the mechanism of bacterial entry. Infect Immun. 1997;65:1475–1485. doi: 10.1128/iai.65.4.1475-1485.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Vazquez-Torres A. Salmonella pathogenicity island 2-dependent evasion of the phagocyte NADPH oxidase. Science. 2000;287:1655–1658. doi: 10.1126/science.287.5458.1655. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Sidorenko SP, Clark EA. The dual-function CD150 receptor subfamily: the viral attraction. Nat Immunol. 2003;4:19–24. doi: 10.1038/ni0103-19. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Underhill DM, Ozinsky A. Phagocytosis of microbes: complexity in action. Annu Rev Immunol. 2002;20:825–852. doi: 10.1146/annurev.immunol.20.103001.114744. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Fang FC. Antimicrobial reactive oxygen and nitrogen species: concepts and controversies. Nat Rev Microbiol. 2004;2:820–832. doi: 10.1038/nrmicro1004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Ho LH, Uehara T, Chen CC, Kubagawa H, Cooper MD. Constitutive tyrosine phosphorylation of the inhibitory paired Ig-like receptor PIR-B. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1999;96:15086–15090. doi: 10.1073/pnas.96.26.15086. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Brown EJ. Leukocyte migration: dismantling inhibition. Trends in Cell Biology. 2005;15:393–395. doi: 10.1016/j.tcb.2005.06.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Hotchkiss RS, Osmon SB, Chang KC, Wagner TH, Coopersmith CM, Karl IE. Accelerated lymphocyte death in sepsis occurs by both the death receptor and mitochondrial pathways. J Immunol. 2005;174:5110–5118. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.174.8.5110. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Hotchkiss RS, Swanson PE, Cobb JP, Jacobson A, Buchman TG, Karl IE. Apoptosis in lymphoid and parenchymal cells during sepsis: findings in normal and T- and B-cell-deficient mice. Crit Care Med. 1997;25:1298–1307. doi: 10.1097/00003246-199708000-00015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Roy MF, Malo D. Genetic regulation of host responses to Salmonella infection in mice. Genes Immun. 2002;3:381–393. doi: 10.1038/sj.gene.6363924. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Sinha K, Mastroeni P, Harrison J, de Hormaeche RD, Hormaeche CE. Salmonella typhimurium aroA, htrA, and aroD htrA mutants cause progressive infections in athymic (nu/nu) BALB/c mice. Infect Immun. 1997;65:1566–1569. doi: 10.1128/iai.65.4.1566-1569.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Hess J, Ladel C, Miko D, Kaufmann SH. Salmonella typhimurium aroA- infection in gene-targeted immunodeficient mice: major role of CD4+ TCR-αβ cells and IFN-γ in bacterial clearance independent of intracellular location. J Immunol. 1996;156:3321–3326. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Weintraub BC, Eckmann L, Okamoto S, Hense M, Hedrick SM, Fierer J. Role of αβ and γδ T cells in the host response to Salmonella infection as demonstrated in T-cell-receptor-deficient mice of defined Ity genotypes. Infect Immun. 1997;65:2306–2312. doi: 10.1128/iai.65.6.2306-2312.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Everest P, Roberts M, Dougan G. Susceptibility to Salmonella typhimurium infection and effectiveness of vaccination in mice deficient in the tumor necrosis factor alpha p55 receptor. Infect Immun. 1998;66:3355–3364. doi: 10.1128/iai.66.7.3355-3364.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Mittrucker HW, Kohler A, Mak TW, Kaufmann SH. Critical role of CD28 in protective immunity against Salmonella typhimurium. J Immunol. 1999;163:6769–6776. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.al-Ramadi BK, Fernandez-Cabezudo MJ, Ullah A, El-Hasasna H, Flavell RA. CD154 is essential for protective immunity in experimental Salmonella infection: evidence for a dual role in innate and adaptive immune responses. J Immunol. 2006;176:496–506. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.176.1.496. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Nagai Y, Akashi S, Nagafuku M, Ogata M, Iwakura Y, Akira S, Kitamura T, Kosugi A, Kimoto M, Miyake K. Essential role of MD-2 in LPS responsiveness and TLR4 distribution. Nat Immunol. 2002;3:667–672. doi: 10.1038/ni809. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]