Abstract

Proteins such as the product of the breakpoint cluster region, chimaerin, and the Src homology 3-binding protein 3BP1, are GTPase activating proteins (GAPs) for members of the Rho subfamily of small GTP-binding proteins (G proteins or GTPases). A 200-residue region, named the breakpoint cluster region-homology (BH) domain, is responsible for the GAP activity. We describe here the crystal structure of the BH domain from the p85 subunit of phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase at 2.0 Å resolution. The domain is composed of seven helices, having a previously unobserved arrangement. A core of four helices contains most residues that are conserved in the BH family. Their packing suggests the location of a G-protein binding site. This structure of a GAP-like domain for small GTP-binding proteins provides a framework for analyzing the function of this class of molecules.

Keywords: signal transduction, GTPase-activating protein, x-ray crystallography, Cdc42Hs

Small GTP-binding proteins (G proteins or GTPases) control processes such as proliferation, vesicular transport, and the regulation of the actin cytoskeleton (1). They cluster in functionally differentiated subfamilies. Members of the Rho subfamily, which includes the Saccharomyces cerevisiae CDC42 protein, and the mammalian proteins Rho, Rac, and Cdc42Hs participate in cytoskeletal organization and in certain signal transduction pathways (2–4). There are families of GTPase activating proteins (GAPs), each with a characteristic sequence, for specific interaction with different subfamilies of small GTP-binding proteins (5). A 200-residue conserved segment, generally referred to as the RhoGAP domain, has been found in a large group of proteins, some of which have documented GAP activity for members of the Rho subfamily (6–10). This domain was originally identified as a region of homology between the RhoGAP and the product of the breakpoint cluster region (7). It is present in the S. cerevisiae Bem2 and Bem3 proteins, which are known to interact genetically with Cdc42 in the control of the site of bud assembly (11), as well as in many otherwise unrelated, multifunctional mammalian proteins. A multiple sequence alignment and a list of molecules containing the domain are reported in Fig. 1. The domain occurs at different sites and contexts in these molecules, suggesting that it acts as a functionally independent module. In vitro studies have shown that RhoGAP domains interact with specific members of the Rho subfamily. For instance, the recombinant RhoGAP domains from the p190 and the RhoGAP proteins preferentially stimulate Rho and Cdc42Hs, respectively (13, 14). This observation, together with the existence of RhoGAP domains that are unable to stimulate GTP hydrolysis despite their ability to interact with a G protein target (see below), prompt us to use the name “Bcr-homology” (BH) domain in place of the more misleading name “RhoGAP” domain.

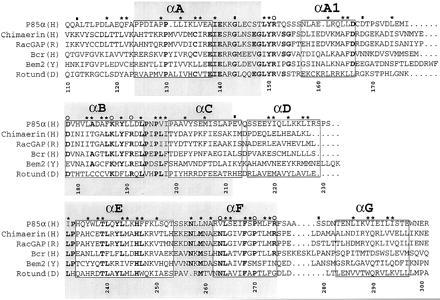

Figure 1.

A sequence alignment of a subset of BRC-homology (BH) domains. A larger alignment, comprising 22 sequences, was used to evaluate the degree of sequence conservation at each position. The sequences used, with their database accession number for each sequence listed last in parentheses, are reported (B, bovine; CE, Caenorhabditis elegans; D, Drosophila melanogaster; H, human; M, mouse; R, rat; Y, Saccharomyces cerevisiae): (H) breakpoint cluster region (Bcr) (P11274); (H) ABR (U01147); (M) 3BP1 (X87671); (R) p122 (D31962); (R) p190 (M94721); (H) C1 (X78817); (Y) Bem2 (P39960); (Y) Bem3 (P32873); (R) β-chimaerin (Q03070); (H) IT5P (P32019); (Y) RGA1 (P39083); (D) Rotund (P40809); (M) p85α (P26450); (H) p85α ((P27986); (B) p85α (P23727); (B) p85β (P23726); (H) n-chimaerin (P15882); (R) n-chimaerin (P30337); (H) OCRL (Q01968); (Y) YB9G (P38339); (H) RhoGAP (Z23024); (CE) CeGAP (U02289). Residues that were conserved in at least 14 sequences out of 22 are shown in bold type. Asterisks above columns indicate residues whose side chains are part of the hydrophobic core of the molecule. Open circles identify residues that are part of the proposed ligand-binding site. Filled rectangles indicate residues lying at intron–exon boundaries in the mouse p85α gene (12). Each helical fragment boxed. The N- and C-terminal residues of each helix were defined as the first and last residues whose main chain carbonyl and amide groups, respectively, were involved in an intrahelical hydrogen bond. The gray boxes identify three blocks of conservation discussed in the text. Numbering corresponds to full-length human p85α. The alignment was generated with the pileup program (GCG package). The image was created using the programs Adobe illustrator and Adobe photoshop (Adobe Systems, Mountain View, CA).

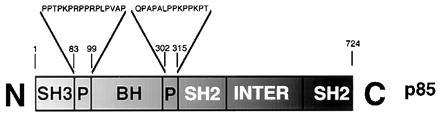

Phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase (PI3K) has a critical role in signal transduction pathways originating from a variety of membrane-bound receptors (15). It is a heterodimer of an adapter (p85) subunit and a catalytic (p110) subunit. The p85 subunit contains a BH domain, as shown in Fig. 2. It is flanked by proline-rich sequences that are potential targets of SH3 domains, including the p85 SH3 domain itself (16, 17). The p85 BH domain interacts with Cdc42Hs and Rac but not with Rho (18, 19). G protein binding leads to the activation of the lipid kinase domain in the p110 subunit (18), but the physiological significance of these results is yet to be established. The ability of the PI3K BH domain to interact with these G proteins does not correlate with catalytic activation of GTP hydrolysis; so far, it has not been possible to show that the p85 BH domain acts as a GAP for the G proteins with which it binds.

Figure 2.

Schematic view of the domain organization of p85. SH2 and SH3, Src-homology regions 2 and 3, respectively; P, proline-rich regions (see text); INTER, the inter-SH2 region that mediates dimerization with p110.

The three-dimensional structure of a BH domain has not previously been determined. Here we report the crystal structure of the BH domain of human p85α at a resolution of 2.0 Å. We describe some of its relevant features and propose the location of the G protein binding site.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Expression and Purification of the PI3K BH Domain.

PCR was used to introduce NcoI and XhoI restriction sites up- and downstream of the region of human p85α cDNA (20) encoding residues 105–319. The DNA fragment was subcloned in the pBAT4 vector (Peränen, J. and Hyvönen, M., unpublished), and the encoded protein was expressed in Escherichia coli strain BL21 (DE3) at 37°C. Cells from a 3-liter culture were harvested by centrifugation and resuspended in 60 ml of buffer A (50 mM Tris, pH 8.5/50 mM NaCl/1 mM EDTA/1 mM benzamidine/1 mM DTT). After sonication, the lysate was centrifuged on a Beckmann 45Ti rotor at 40000 rpm for 3 hr. Ion exchange and size exclusion chromatography were carried out by FPLC at 4°C. The clear supernatant was loaded onto a 50-ml bed volume column packed with Q-Sepharose HP (Pharmacia), and equilibrated with buffer A. Bound proteins were eluted with a linear salt gradient (50 mM to 1 M NaCl). Fractions containing the BH domain were pooled and precipitated with 75% saturated ammonium sulfate. The precipitate was harvested by centrifugation, resuspended in a small volume of buffer B (buffer A devoid of benzamidine), and loaded onto a Pharmacia Superdex 75 (16/60) size exclusion column. Fractions containing the BH domain were pooled and loaded onto a MonoQ ion-exchange column (Pharmacia), equilibrated with buffer C (20 mM Tris, pH 8.0/50 mM NaCl/1 mM DTT/1 mM EDTA). The BH domain eluted at a NaCl concentration of 300 mM. The protein was concentrated with Centriprep 10 (Amicon) to a final concentration of 15 mg/ml.

Crystallographic Methods.

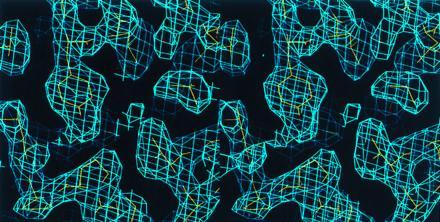

The protein was immediately used for crystallization by hanging drop vapor diffusion. Better crystals were obtained by microseeding 4-μl drops equilibrated for 1 week against a reservoir buffer containing 3.6 M sodium formate, pH 5.0. Monoclinic crystals (P21 a = 39.0, b = 90.51, c = 69.28, β = 97.2; two monomers per asymmetric unit) reached dimensions of 0.2 × 0.4 × 0.1 mm in about 2 weeks. X-ray diffraction data were collected at 4°C on an 18-cm image plate scanner (MAR Research, Hamburg) on GX-13 rotating anode source (Elliott, London). Oscillation images (1°) were processed using denzo, and diffraction intensities were scaled and merged with scalepack (21). Subsequent computations used the ccp4 program suite (22). The structure was determined using single isomorphous replacement and twofold averaging. Two independent derivative data sets were obtained from single crystals that had been incubated for 15–20 hr in a synthetic mother liquor containing 3.8 M sodium formate, pH 5.6, supplemented with 100 μM and 500 μM methyl mercury nitrate, respectively. Derivative data were scaled to native data that had been placed on an approximate absolute scale. Refinement of heavy atom parameters was carried out with the program mlphare (23), using both centric and acentric data. Inclusion of two methyl mercury derivatives significantly improved the phases even though the duplicate data sets had identical sites and similar occupancies. The electron density map was improved by solvent flattening and histogram matching using the program dm (24). The resulting map showed a clear solvent boundary, and a mask covering one of the monomers present in the asymmetric unit was created with the program mama (25). The rotational components of the noncrystallographic diad axis were found by calculation of a self-rotation function with the program amore (26), and the translational components were inferred from the positions of the four heavy atom sites. Noncrystallographic symmetry averaging was computed with the program dm. The resulting modified map (Fig. 3) could be interpreted readily to include most main chain and side chain atoms. Model building was carried out with the program o (27). Noncrystallographic symmetry was used as a restraint in the first rounds of crystallographic refinement with x-plor (28). Manual rebuilding and several cycles of simulated annealing and positional refinement completed the refinement process. The final model includes residues 115–298 for monomer A and residues 115–309 for monomer B, and 267 ordered water molecules. Residues 167–172 on each monomer are disordered.

Figure 3.

Stereo view of the averaged electron density map (contoured at 1 σ), shown against the final model. The map was used to build the model of the BH domain.

RESULTS

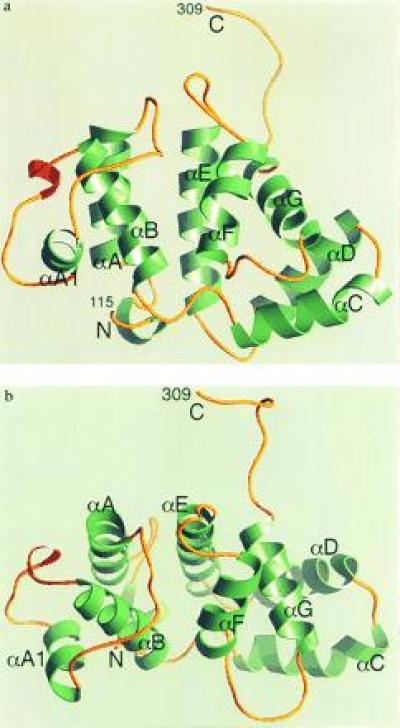

The 216-residue domain [residues 105–319 of the region of human p85α (20) plus an N-terminal methionine] was expressed, purified, and crystallized as described in Materials and Methods. The structure was solved by the single isomorphous replacement method. A summary of the structure determination and model refinement is presented in Tables 1 and 2. The domain contains seven helices (αA–αF) separated by loops of variable length (Fig. 4). Helices αA and αB (residues 132–143 and 178–192), and αE and αF (residues 234–253 and 262–272), respectively, form two helical hairpins that pack against each other in a parallel fashion to form the central core of the domain. The loop between αA and αB (AB loop) is 35 residues long. Residues 158–165 in this loop form a helix, αA1. Helices αC and αD form a helical hairpin that projects away from the core and packs against the C-terminal αG helix. The latter packs in turn against the αE and αF helices. The arrangement of the αA, αB, αE, and αF helices can be regarded as a four-helix bundle (30), in which all but one (the αB–αF) of the helix–helix interactions are (roughly) parallel. The divergence of the αB–αF helices seems to be caused by the side chain of Tyr-150 (AB loop), which points toward the inside of the molecule. Its phenolic hydroxyl is engaged in a hydrogen bond with the side chain of His-246 on helix αE and is completely buried within the hydrophobic core of the bundle. The interface between helices αC–αG can be regarded as a second, distinct hydrophobic core. In summary, the structure of the BH domain can be conveniently described as a four-helix bundle, with a projection composed of three more helices. We carried out a search of the protein structural data base with the program dali (31) and failed to identify a similar fold in known proteins. The BH domain, therefore, appears to represent a previously undescribed protein fold.

Table 1.

Summary of SIR phase determination

| Data set | Me Hg NO3

|

|

|---|---|---|

| 1 | 2 | |

| Isomorphous difference,* % | 17.5 | 15.8 |

| Phasing power† (acentric/centric) | 1.84/1.17 | 2.52/1.76 |

| Rcullis‡ | 0.71 | 0.59 |

| No. of sites | 4 | 4 |

|

|

|

|

Table 2.

Data collection and refinement statistics

| Data set | Native | Me Hg NO3

|

|

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 2 | ||

| Reflections | |||

| Max. resolution, Å | 2.0 | 2.7 | 2.3 |

| Observed/unique | 124,328/30,040 | 58,379/12,520 | 92,414/20,358 |

| Rsym,* % (all data/last shell) | 5.7/19.3 | 11.4/24.9 | 7.9/21.4 |

| Completeness, % (all data/last shell) | 96/84 | 96/97 | 96/94 |

| I/σI (last shell) | 5.4 | 3.9 | 3.7 |

| Refinement | |||

| Rcryst/Rfree,† % (all data in 8.0–2.0 Å range) | 18.4/23.5 | ||

| Resolution, Å | 8.0–2.0 | ||

| rms deviation bond lengths, Å | 0.011 | ||

| rms deviation bond angles | 1.6° | ||

|

|

Figure 4.

(a) Ribbon diagram of the PI3K BH domain. Molecule B is shown. α-Helices are in green, and 310 helices are in red. N and C indicate the N and C termini of the domain, respectively. The figure was created with the program ribbons (29). (b) A view of the domain from the top of the four-helix bundle, roughly corresponding to a 90° rotation about a horizontal axis parallel to the plane of the page in a.

Three blocks of sequence conservation have been identified in the BH family (see for example refs. 8 and 11). These correspond to αA and the N-terminal half of the AB loop (block 1), αB, the BC loop, and part of αC (block 2), and αE-αF (block 3), respectively (Fig. 1). These regions roughly coincide with the four-helix bundle core of the domain. Our structure shows that the boundaries of the domain extend beyond these conserved regions. At the N terminus, the side chains of Leu-118, Gln-121, and Phe-122 are buried within the hydrophobic core of the molecule and appear to be important for protein stability. The C-terminal αG helix, also corresponding to a region of poor sequence conservation, plays an essential role in the packing of the domain. Thus, poorly conserved regions at both termini are integral structural components of the BH domain.

Crystals of the BH domain contain two monomers (A and B) in the asymmetric unit, related by a proper twofold noncrystallographic symmetry axis. A superposition of the A and B monomers shows that the rms deviation in the positions of 178 Ca atoms is 0.65 Å. The dimerization interface is hydrophobic, with the side chain of Met-176 from one monomer inserting into a small, exposed pocket formed by Leu-161, Ile-177, and Val-181 from the other monomer (all residues are located in the AB loop). A different crystal form of the domain shows the same interaction (unpublished data).

Our crystal structure (residues 105–319 of p85α) includes the proline-rich region C-terminal to the BH domain (Fig. 1). There is poor electron density for this region in molecule A, but in molecule B, there is very clear electron density as far as Pro-309. The polypeptide chain corresponding to the RQPAPALPP (residues 301–309) motif extends away from the core of the molecule and is involved in a crystal contact. It is elongated, but it does not form the PPII helix that is observed in SH3 ligands (32, 33).

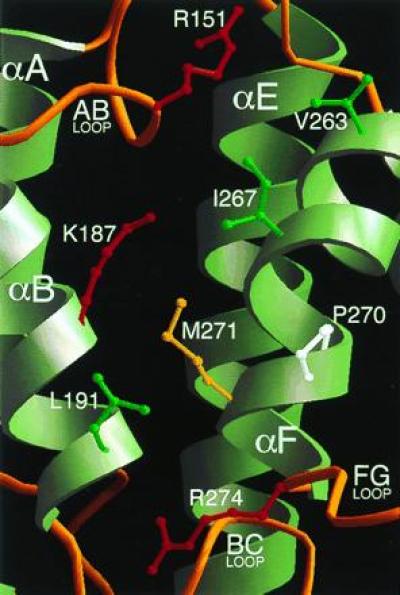

To identify the potential site of interaction of BH domains with G proteins, we have analyzed the distribution on the three-dimensional structure of residues that are conserved in the BH family. Residues such as Arg-151, Lys-187, and Pro-270 are among the best conserved (Fig. 1). They cluster around a shallow pocket, whose floor is formed by the solvent-exposed surfaces of helices αB and αF, and whose rim is contributed by the N-terminal portion of the AB loop, and, opposite to it, the FG loop (Fig. 5). In the p85α BH domain, the floor of this pocket is formed by several non- or poorly conserved hydrophobic side chains, including those of Val-263, Ile-267, and Met-271, all contributed by helix αF. This helix is kinked, due to the presence of Pro-270. Leu-191 from the αB helix also contributes to the hydrophobic character of this patch. We propose that this exposed patch is the G protein-binding site of the BH domain. Most other conserved residues are scattered at different sites of the three-dimensional structure, mainly in the four-helix bundle, and are not part of a well-defined patch. Conservation is particularly strong in the BC loop. Leu-193 is the only residue to be fully conserved in the BH family, and Pro-194 and Pro-196 are present in 22 out of 23 sequences. The function of this loop may be to provide a rigid link between the four-helix bundle and the helical projection consisting of helices αC and αD, thereby contributing to the stabilization of the domain.

Figure 5.

The proposed G protein-binding site of the BH domain. The domain is viewed from the same orientation shown in Fig. 4A. Residues Arg-151, Lys-187, Pro-270, and Arg-274 are conserved in the BH family. Leu-191 and Val-263 are nonconserved residues occurring at sites that are otherwise strongly conserved (Fig. 1). The side chains of Ile-267 and Met-271 are included to show the relatively hydrophobic character of this patch.

DISCUSSION

We have determined the crystal structure of a member of the BH family of protein domains. The structure is α-helical, and it seems to represent a previously undescribed protein fold. The conservation of residues in the hydrophobic core of the domain (Fig. 1) indicates a strong structural conservation within the family.

BH domains were originally characterized for their ability to stimulate the GTP hydrolysis of small GTP-binding proteins (7). The reaction is highly specific for members of the Rho family of GTPases. Furthermore, it is selective, in that different BH domains act predominantly on certain members of the Rho family and not on others. This selectivity is also characteristic of the PI3K BH domain; it interacts with Rac1 and Cdc42Hs, but it is unable to bind Rho (18, 19). An important difference between the PI3K domain and other BH domains is that the former does not act as a GAP on the GTPases to which it binds. This observation suggests that BH domains may be regarded as domains that engage in protein–protein interactions with G proteins and may or may not enhance their catalytic rate. At least in vitro several BH domains are able to bind to the GTP- and GDP-bound forms of the G protein with similar affinities, further reinforcing the idea that the G protein-binding and GAP functions are separate activities (8, 34). The ability of the PI3K BH domain to interact with Rac1 and Cdc42Hs may be important for translocating PI3K to membranes and for stimulating its catalytic activity. The molecular mechanism by which certain GAPs help G proteins to catalyze GTP hydrolysis is not yet known. They may provide a key residue (e.g., a catalytic base or a positive charge to stabilize the transition state) or induce an active conformational state.

To identify the site of G protein interaction, we have analyzed the distribution of conserved surface residues onto the three-dimensional structure of the BH domain. The rationale behind this approach is that these residues should be responsible for the common function of BH domains, namely GTPase-binding. We have described a surface patch where a few well conserved residues cluster and have proposed that this is the site of G protein interaction. This view is reinforced by the observation that mutations Val-261 to Asp and Pro-264 to Arg (equivalent to positions Ile-267 and Pro-270 in p85) in the BH domain of n-chimaerin severely impair the GAP function of this domain (8). We cannot at this point explain the lack of GAP activity by the PI3K BH domain. It is possible that it may lack specific residue(s) important for the stimulation of γ-phosphate hydrolysis. Arg-191 and Asn-263, which are part of the proposed ligand-binding site but which are not conserved in the PI3K BH domain (they are instead leucine and valine, respectively), are good candidates for this function. Preliminary evidence suggests that a rather extended surface area of the G protein, comprising at least the effector loop (a region that has been implicated in the binding of G protein targets) and the β5-α3 loop, appears to be involved in BH binding (18, 35). There is some sequence variation at these site that correlates with the observed selectivity of the G protein–BH domain interactions.

It has been reported that PI3K interacts with 14–3-3 proteins in in Jurkat T cells (36). The 14–3-3 proteins have recently been shown to recognize phosphorylated serine residues in the consensus sequence RSXpSXP, where X is any amino acid, and pS is a phosphorylated serine residue (37). A sequence of this sort is found in the BH domain (RSPSIP, residues 228–233). It is part of an exposed loop between helices αD and αE (Fig. 4a). It is not known whether Ser-231 in this sequence is phosphorylated in vivo.

BH domains are often flanked by proline-rich regions, which are potential targets of SH3 and WW domains (6, 38). These interactions may be important for the subcellular localization and catalytic activation of PI3K. Proline-rich sequences flank the p85 BH domain (Fig. 2). They are targets of the SH3 domains of several proteins, including p85 itself (16, 17), probably reflecting a regulatory mechanism for BH and PI3K activation. Binding of Src-family kinase SH3 to the p85 subunit activates the lipid kinase of PI3K (17). In p85, the sequence KPRPPRPLPVAP in the N-terminal proline-rich stretch is a likely target of PI3K-SH3, as it contains two partially overlapping motifs (KPRPPRP and RPLPVAP) that agree well with the class I consensus sequence for this domain (32). Binding of the PI3K SH3 domain to this sequence may occur by an intermolecular mechanism. Preliminary observations suggest that a recombinant SH3-BH domain fragment, which includes both proline-rich regions of p85, behaves as a dimer in size-exclusion chromatography (unpublished results). We note that the p85 BH domain forms a dimer in the crystals described here. This interaction must be weak, as we have no evidence of dimer formation during purification of the domain, but it could represent a detail of a stronger complex resulting from the concomitant intermolecular binding of the SH3 domain to the proline-rich regions. It remains to be seen whether dimerization is important for the catalytic activation of the lipid kinase domain in the p110 subunit.

Acknowledgments

We are grateful to Michael Eck, David Fruman, Mykol Larvie, Martin Lawrence, Robert Nolte, and Kimberly Tolias for helpful discussions and critical reading of the manuscript. A.M. is a Human Frontier Science Program postdoctoral fellow. This work was partly supported by National Institutes of Health Grant GM36624 to L.C.C. S.C.H. is an Investigator in the Howard Hughes Medical Institute.

Footnotes

Abbreviations: BH, Breakpoint cluster region-homology; GAP, GTPase-activating protein; PI3K, phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase; SH2 and SH3, Src homology regions 2 and 3.

Data deposition: The atomic coordinates and structure factors have been deposited in the Protein Data Bank, Chemistry Department, Brookhaven National Laboratory, Upton, NY 11973 (reference 1PBW).

References

- 1.Bourne H R, Sanders D A, McCormick F. Nature (London) 1991;349:117–127. doi: 10.1038/349117a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ridley A J. J Cell Sci Suppl. 1994;18:127–131. doi: 10.1242/jcs.1994.supplement_18.19. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Hall A. Cell. 1992;69:389–391. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(92)90441-e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Vojtek A B, Cooper J A. Cell. 1995;82:527–529. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(95)90023-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Boguski M S, McCormick F. Nature (London) 1993;366:643–654. doi: 10.1038/366643a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Lamarche N, Hall A. Trends Genet. 1994;10:436–440. doi: 10.1016/0168-9525(94)90114-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Diekmann D, Brill S, Garrett M D, Totty N, Hsuan J, Monfries C, Hall C, Lim L, Hall A. Nature (London) 1991;351:400–402. doi: 10.1038/351400a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ahmed S, Lee J, Wen L P, Zhao Z, Ho J, Best A, Kozma R, Lim L. J Biol Chem. 1994;269:17642–17648. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Cicchetti P, Ridley A J, Zheng Y, Cerione R A, Baltimore D. EMBO J. 1995;14:3127–3135. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1995.tb07315.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Baldwin G S, Zhang Q X. Trends Biochem Sci. 1993;18:378–380. doi: 10.1016/0968-0004(93)90093-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Zheng Y, Hart M J, Shinjo K, Evans T, Bender A, Cerione R A. J Biol Chem. 1993;268:24629–24634. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Fruman, D. A., Cantley, L. C. & Carpenter, C. L. (1996) Genomics, in press. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 13.Ridley A J, Self A J, Kasmi F, Paterson H F, Hall A, Marshall C J, Ellis C. EMBO J. 1993;12:5151–5160. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1993.tb06210.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Lancaster C A, Taylor H P, Self A J, Brill S, van Erp E H, Hall A. J Biol Chem. 1994;269:1137–1142. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kapeller R, Cantley L C. BioEssays. 1994;16:565–576. doi: 10.1002/bies.950160810. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kapeller R, Prasad K V, Janssen O, Hou W, Schaffhausen B S, Rudd C E, Cantley L C. J Biol Chem. 1994;269:1927–1933. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Pleiman C M, Hertz W M, Cambier J C. Science. 1994;263:1609–1612. doi: 10.1126/science.8128248. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Zheng Y, Bagrodia S, Cerione R A. J Biol Chem. 1994;269:18727–18730. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Tolias K F, Cantley L C, Carpenter C L. J Biol Chem. 1995;270:17656–17659. doi: 10.1074/jbc.270.30.17656. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Skolnik E Y, Margolis B, Mohammadi M, Lowenstein E, Fischer R, Drepps A, Ullrich A, Schlessinger J. Cell. 1991;65:83–90. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(91)90410-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Otwinowski Z. In: Data Collection and Processing. Sawyer L, Isaacs N, Bailey S, editors. Warrington, U.K.: Science and Engineering Research Council/Daresbury Laboratory; 1993. pp. 56–62. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Collaborative Computational Program Number 4 (CCP4) Acta Crystallogr D. 1994;50:760–763. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Otwinowski Z. In: Isomorphus Replacement and Anomalous Scattering. Wolf W, Evans P R, Leslie A G W, editors. Warrington, U.K.: Science and Engineering Research Council/Daresbury Laboratory; 1991. pp. 80–86. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Cowtan K. Joint CCP4 ESF-EACBM Newsl Protein Crystallogr. 1994;31:34–38. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kleywegt G J, Jones T A. In: Proceedings of the CCP4 Study Weekend. Bailey S, Hubbard R, Waller D, editors. Daresbury, U.K.: Daresbury Laboratory; 1994. pp. 59–66. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Navaza J. In: Molecular Replacement: Proceedings of the CCP4 Study Weekend. Dodson E J, Gover S, Wolf W, editors. Daresbury, U.K.: Science and Engineering Research Council; 1992. pp. 87–90. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Jones T A, Zou J-Y, Cowan S W. Acta Crystallogr A. 1991;47:110–119. doi: 10.1107/s0108767390010224. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Brunger, A. T. (1992) x-plor Manual (Yale Univ., New Haven, CT).

- 29.Carson M. J Appl Crystallogr. 1991;24:958–961. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Harris N L, Presnell S R, Cohen F E. J Mol Biol. 1994;236:1356–1368. doi: 10.1016/0022-2836(94)90063-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Holm L, Sander C. Trends Biochem Sci. 1995;20:478–480. doi: 10.1016/s0968-0004(00)89105-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Yu H, Chen J K, Feng S, Dalgarno D C, Brauer A W, Schreiber S L. Cell. 1994;76:933–945. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(94)90367-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Musacchio A, Saraste M, Wilmanns M. Nat Struct Biol. 1994;1:546–551. doi: 10.1038/nsb0894-546. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Self A J, Hall A. Methods Enzymol. 1995;256:67–77. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Diekmann D, Nobes C D, Burbelo P D, Abo A, Hall A. EMBO J. 1995;14:5297–5305. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1995.tb00214.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Bonnefoy-Berard N, Liu Y C, von Willebrand M, Sung A, Elly C, Mustelin T, Yoshida H, Ishizaka K, Altman A. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1995;92:10142–10146. doi: 10.1073/pnas.92.22.10142. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Muslin A J, Tanner J W, Allen P M, Shaw A S. Cell. 1996;84:889–897. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)81067-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Bork P, Sudol M. Trends Biochem Sci. 1994;19:531–533. doi: 10.1016/0968-0004(94)90053-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]