Abstract

DNA damage from exogenous and endogenous sources can promote mutations and cell death. Fortunately, cells contain DNA repair and damage signalling pathways to reduce the mutagenic and cytotoxic effects of DNA damage. The identification of specific DNA repair proteins and the coordination of DNA repair pathways after damage has been a central theme to the field of Genetic Toxicology and we have developed a tool for use in this area. We have produced 99 molecular bar-coded Escherichia coli gene-deletion mutants specific to DNA repair and damage signalling pathways, and each bar-coded mutant can be tracked in pooled format using bar-code specific microarrays. Our design adapted bar-codes developed for the Saccharomyces cerevisiae Gene Deletion Project, which allowed us to utilize an available microarray product for pooled gene-exposure studies. Microarray-based screens were used for en masse identification of individual mutants sensitive to methyl methanesulfonate (MMS). As expected, gene deletion mutants specific to direct, base excision, and recombinational DNA repair pathways were identified as MMS-sensitive in our pooled assay, thus validating our resource. We have demonstrated that molecular bar-codes designed for S. cerevisiae are transferable to E. coli, and that they can be used with pre-existing microarrays to perform competitive growth experiments. Further, when comparing microarray to traditional plate-based screens both over-lapping and distinct results were obtained, which is a novel technical finding, with discrepancies between the two approaches explained by differences in output measurements (DNA content verse cell mass). The microarray-based classification of Δtag and ΔdinG cells as depleted after MMS exposure, contrary to plate-based methods, led to the discovery that Δtag and ΔdinG cells show a filamentation phenotype after MMS exposure, thus accounting for the discrepancy. A novel biological finding is the observation that while ΔdinG cells filament in response to MMS they exhibit wild-type sulA expression after exposure. This decoupling of filamentation from SulA levels suggests that DinG is associated with the SulA-independent filamentation pathway.

Introduction

DNA damage from endogenous and exogenous sources can promote increased mutation rates and cell death, two processes implicated in diseases such as cancer and neurodegeneration [1–10]. Fortunately, cells contain a number of dedicated and functionally conserved DNA repair and damage signaling proteins that promote cell survival. Lesions as diverse as methylated purines, cross-linked pyrimidines, single, and double strand breaks all can be detected and repaired by cellular DNA repair machinery, and adduct repair is vital to cell survival [2]. Over the last 50 years scientists in the field of Genetic Toxicology have dedicated considerable time and effort to the identification of activities that promote the repair of DNA lesions, as well as understanding the regulation of repair activities after DNA damage. Importantly, it has been demonstrated that activities belonging to direct, base excision, mismatch, nucleotide excision, and recombination repair pathways are present in organisms ranging from bacteria to humans, with many of the initial mechanistic and genetic studies performed in E. coli [9, 11–45].

One of the first genetic screens to identify DNA damage induced genes utilized a randomly integrated reporter construct to identify five damage inducible (din) loci in E. coli. The regulation of the identified din loci was recA dependent and one of the loci mapped to the gene for the nucleotide excision repair protein UvrA [46], supporting a role for din genes in the DNA damage response. Later, computational and wet-bench experiments greatly expanded the list of DNA damage response genes, and after the E. coli genome was sequenced it was demonstrated that 115 of the ~4,288 identified genes could be classified in DNA replication, recombination, modification, and repair pathways [47]. Like most model organisms, E. coli has a substantial percentage (38%) of its genes classified as of unknown function, suggesting there is still much to be learned about the activities and regulation of DNA damage signaling pathways. Further, the coordination and integration of DNA damage signaling pathways with each other and the rest of the cellular proteome are still relatively uncharacterized. Systems biology based approaches that utilize global transcriptional profiling or high-throughput screening of gene-deletion mutants, in conjunction with computational approaches, have been used to identify and characterize novel damage signaling pathways in S. cerevisiae [48–53], and systems based approaches are attractive methods to help decipher signaling processes in E. coli.

Gene knockout libraries contain thousands of mutants that have specific genes disrupted or deleted by either transposition events or targeted homologous recombination [54, 55]. High throughput screening methodologies using deletion libraries include robotic spotting of individual strains on agar plates (plate-based screens) and pooled approaches that use microarrays to quantitate mutant specific molecular bar-codes (microarray-based screens) [54–57]. The basic goal of high-throughput screens has been to identify gene products that are important for growth or viability after pharmacological or environmental exposures, and components of the S. cerevisiae cell cycle machinery [48, 58] have recently been identified using high throughput screens. The largest number of high throughput screens has been reported for S. cerevisiae, which is mainly due to the existence of a bar-coded deletion library and the efficiency of microarray-based screens [59–63].

Microarray-based screens utilize two unique molecular bar-codes in each gene deletion mutant to identify those mutants that are depleted after perturbation, relative to an untreated pool. The microarray readout can quantitate thousands of molecular bar-codes at a time, which in theory allows for many screens to be performed in a single day. In contrast a plate based screen of 4,000 E. coli mutants would require weeks of intense work using a 96 well format. In addition plate based screens would require approximately 100 plates for a 96 well format, as opposed to two flasks for the microarray format. Molecular bar-codes not only allow for an efficient and quantitative measure of the number of each mutant in a pool but they are also convenient markers to verify the identity of individual gene deletion mutants stored in 96-well plates.

Microarray based screens are fast and efficient, but quite expensive due to the cost of producing a custom made bar-code microarray. A custom microarray resource developed by the Yeast Bar Code Consortium (YBC) is available to read S. cerevisiae bar-codes, and we decided to use this platform to launch pooled microarray screens in E. coli. While a valuable library of gene-deletion strains is available for E. coli [64], it is limited by the absence of molecular bar-codes. As such, this library is useful only in plate-based screens. We have developed a prototype set of 99 molecularly bar-coded gene deletion mutants of E. coli, with bar-codes borrowed from the S. cerevisiae deletion library, for use in pooled microarray-based screens. The gene deletion mutants are mostly specific to known DNA repair pathways and are compatible with the Keio gene deletion library, due to the use of a different antibiotic marker. This compatibility allows for the facile construction of double mutants using kanamycin and chloramphenicol selections. We have demonstrated that our bar-coded library can be monitored with the existing YBC microarray resource, thus eliminating the costly production of a microarray platform de novo. In addition, we have validated our library by performing a pooled MMS screen, and demonstrated that we can classify mutants deficient in direct, base excision, and recombination repair as MMS sensitive. We have addressed the question of overlap between the results of microarray- and plate-based screens, and demonstrated that microarray based screens can identify both overlapping and novel results. Further, follow up studies have demonstrated that both tag and dinG mutants filament extensively in response to DNA damage, with the filamentation phenotype effectively identified using a comparison of microarray to plate based studies. The MMS induced filamentation of ΔdinG cells is unique because MMS induced sulA levels are similar to wild-type, and our study suggests that DinG plays a role in the SulA independent filamentation pathway.

1. Materials and methods

1.1 Media and strains

Luria Bertani broth (LB) (BP1426-3, Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA) was used to culture all E. coli used in the study. BW25113 was the parental strain [65] used to construct each individual bar coded variant.

1.2 Molecular bar-coded targeting constructs

There were two sets of primers per gene targeting construct, with the first set (bar-code primers) used to add the molecular bar-codes, and the second set (gene-targeting primers) used to add the homologous sequence specific to the gene of interest. All primers were ordered from Integrated DNA Technologies (Coralville, IA), and dissolved in 50 mM HEPES-NaOH, pH 7.5, 100 mM NaCl at a final concentration of 50 mM. Bar-code primers were first used to amplify the chloramphenicol transacetylase cassette from pKD3 [65]. The general design of each bar-code primer was 5’ – universal priming site – barcode – universal priming site – cassette homology − 3’ (76-mer). PCR reactions were performed using the following conditions, 100 ng template DNA, 2.5 mM MgCl2, 0.2 mM dNTP’s, 0. 2µM primers, 2.5 units of Taq Polymerase (Fermentas, Glen Burnie, MD), and 0.125 units Pfu polymerase (Stratagene, La Jolla, CA). Amplification occurred over 30 standard cycles, with a 55°C annealing t emperature. The PCR products were tested for appropriate size on a DNA agarose gel and purified by ethanol precipitation. PCR products were dissolved in 50 µl dH2O. The next round of PCR was used to add gene targeting sequences. The general design of the primers was 5’ – 40 base pairs of homology to the gene of interest – universal priming site – 3’ (60-mer). All primer sequences can be found in Supplemental Table S1. The PCR product from the first round of PCR was diluted 1:1000 for use as template DNA in the second round of PCR, with amplification occurring as described above. The PCR products were checked for appropriate size on a DNA agarose gel and purified by ethanol precipitation.

1.3 Transformation, selection, and verification of individual gene-deletion mutants

PCR products were dissolved in 10 µl of dH2O and half was used for transformations. Electrocompetent cells primed for homologues recombination were prepared as reported [65] and transformed with 5 µl of each purified PCR product by electroporation (BTX ECM 630, 1.8Kv, 25uF, 200 ohms, 1mm cuvets). Transformed cells were selected on LB- chloramphenicol (30 ug/ml) plates. Individual transformants were picked and grown over-night in LB-chloramphenicol liquid medium, and then streaked on LB-chloramphenicol plates to obtain individual isolates free of un-transformed E. coli. Each gene-deletion mutant was validated by PCR and DNA sequencing. PCR primers up- and down-stream of the putative insertion site were designed and obtained from Integrated DNA Technologies. PCR reactions were performed using the Fail- Safe PCR kit (Epicenter, Madison, WI) using DNA obtained from cells treated with the Lyse-N-Go kit (Pierce, Rockford, IL). PCR products were visualized on a 1% DNA agarose gel and where applicable, size was used to make an initial assessment on the presence or absence of a deletion cassette in a gene of interest. In addition, all PCR products were purified using the QIAquick PCR purification kit (Qiagen, Valencia, CA) and subjected to DNA sequence analysis at the Center for Functional Genomics (University at Albany, Rensselaer, NY). DNA sequence analysis of the PCR product specific to each targeting construct was performed and used to demonstrate the proper placement of the deletion cassette and to validate the identity of the molecular bar-codes.

1.4 Pooled microarray based screens for MMS-sensitivity

Initial screening conditions were adjusted so that ΔalkB mutants did not grow in MMS containing media, relative to untreated media. The ΔalkB strain was chosen because it is deficient in the repair of 1-methyladenine and 3-methylcytosine lesions induced by MMS, and the strain is noticeably growth impaired at relatively low concentrations of MMS. To initiate the microarray based screen, each of the 99 gene-deletion strains were grown overnight in LB-chloramphenicol, and combined in equal cell numbers to generate a pooled sample. The pooled sample was diluted 1:500 and split into (1) LB and (2) LB + 0.015% MMS samples. Cells were grown at 37°C for ~ 6-hours and harvested by centrifugation when they attained an OD600 =~1.0. DNA from each pool was purified by phenol extraction and used in PCR reactions to generate Cy3 or Cy5 tagged PCR products. Cy3 and Cy5 labeled oligonucleotides included 5’-UP (5’ GATGTCCACGAGGTCTCT 3’), 3’-UP (5’ CGGTGTCGGTCTCGTAG 3’), 5’-DWN (5’ GTCGACCTGCAGCGTACG 3’), and 3’-DWN (5’ CGAGCTCGAATTCATCGAT 3’) [66]. PCR reactions were performed using Taq Polymerase (Fermentas) with the following conditions; 250 ng template DNA, 1.5 mM MgCl2, 250uM dNTP’s, 0.05 uM unlabeled (UP) primer, 0.5 uM labeled (DWN) primer. Bar-code amplification occurred over 30 cycles, with an annealing temperature of 50°C. PCR products were th en verified on a 2% agarose gel and supplied to the microarray core facility of the University at Albany for hybridizations. The microarray we used was designed by the Yeast Bar-Code Array Consortium and is available from Agilent (Santa Clara, CA). Hybridization and wash steps were performed as reported [67]. Microarray scanning was performed using an Axon Instruments scanner model GenePix 4000B running GenePix Pro v5.1 scanning software. For both untreated and MMS treated pools, dye swap experiments were preformed. In addition a control set of experiments that compared untreated to untreated pools was performed to identify probes that displayed variable hybridization under untreated conditions. Data analysis consisted of a global normalization step to equalize the average Cy3 and Cy5 fluorescence levels in each samples, followed by log2 transformation of untreated / MMS treated intensities. Gene deletion mutants were classified as MMS sensitive if both upstream- and downstream bar-codes showed > 2-fold increase in the untreated pool, relative to the MMS treated pool. In addition, we performed a T-test on each set of bar-codes that met our criteria to determine the probability that MMS depleted bar-codes were significantly different than the entire group of hybridized products.

1.5 Plate-based and liquid based growth assays after MMS treatment

MMS plate based assays were performed in 96 well format using a 96-syringe Thermo Scientific Hydra Robot (Hudson, NH). Briefly, gene deletion mutants were grown overnight in 96 well plates containing LB-chloramphenicol and robotically spotted onto LB-chloramphenicol plates containing increasing concentrations of MMS. Plates were incubated at 37°C for 16 hours, imaged using the Alphaimager (Alpha Innotech, San Leandro, CA), and MMS-sensitive gene deletion mutants were identified visually relative to wild-type and gene deletion mutants grown on LB alone. MMS-plate based dilution assays were performed using overnight cultures grown in LB-chloramphenicol. These overnight cultures and 10-fold serial dilutions over 6 logs were manually spotted onto LB-chloramphenicol plates supplemented with 0.00, 0.045, 0.060, or 0.075% MMS. Plates were incubated at 37°C overnight and imaged using an Alphaimager (Alpha Innotech, San Leandro, CA). Untreated and MMS treated plates were compared visually to identify gene deletion strains that grew more poorly on agent containing plates, relative to control strains. Liquid growth experiments were performed in LB broth and LB broth supplemented with 0.015% MMS. Overnight cultures grown in LB broth plus chloramphenicol were diluted 1:500 into fresh medium and cell density was measured by monitoring absorbance at 600 nm over six hours. Cells were visualized by light microscopy after six hours and pictures were taken using a Nikon TS100 camera and analyzed using Spot V4.5 diagnostic software.

1.6 SOS-reporter assays

Each gene-deletion mutant and wild-type BW25113 were made chemocompetent using 2X TSS, transformed with a sulA-GFP reporter (pMS201_sulA_GFP, Open Biosystems, Huntsville, AL), and selected on TY-kanamycin (40 ug/ml) plates. Individual isolates were cultured overnight in LB-kanamycin liquid medium, diluted 1:500 and grown to an A600 = 0.4. Cultures were then split in half and either left untreated or treated with 0.015% MMS for 30 minutes. Cultures were then placed on ice, spun down, washed with phosphate buffered saline, and analyzed by fluorescent activated cell sorting (FACS) analysis. The intensity of the GFP reporter was analyzed in a population of 30,000 cells using a Becton Dickinson LSRII Benchtop Flow Cytometer. All assays were performed in duplicate.

2. Results

2.1 99 unique molecular bar-coded gene deletion mutants were developed

To generate molecular bar-coded gene deletion mutants in E. coli BW25113 we first used PCR based methods to produce targeting constructs (Fig. 1A). Two rounds of PCR were used to (1) add molecular bar-codes to the 5’ and 3’ ends of a chloramphenicol resistance cassette, and (2) add homologous targeting sequences. The two targeting sequences were exact sequence matches to 40 bases 5’ and 3’ to the start and stop codons of targeted genes, respectively, and allowed for the complete ablation of a specific gene (Supplemental Table S1). The design of the knockout cassette was based on those used to generate S. cerevisiae gene deletion mutants, with differences in the antibiotic marker and the presence of FLP recombinase target (FRT) sites to facilitate removal of the marker at a latter time. We generated 120 targeting constructs, electroporated electrocompetent cells, and selected transformants on LB-chloramphenicol plates to produce candidate colonies representing molecular bar-coded gene deletion mutants. In all 120 constructs were designed and 99 potential knockouts were generated. The construction of 21 mutants failed due to PCR or transformation failures (yeaR, xseB, ykgA, dnak, ftsK, xthA, dnaB, dnaG, slyD, topA, purB, ihr, yfjY, ybbI, ygjF, gmk, reqQ, katG, guaA, guaB, and ruvA); however guaA and guaB bar-coded mutants were eventually obtained when the selection medium was supplemented with guanine.

Figure 1. Molecular Bar-code Design and Validation in E. coli.

(A) Primers containing sequences (P1, P2, light blue arrows) specific to the CAMR gene were designed to also contain unique molecular bar-codes (UT, DT, purple lines) between two universal priming sites (yellow lines). A second round of PCR was used to add gene specific targeting sequences (H1, H2, red lines). The two different molecular bar codes (purple rectangles) in each gene deletion strain are unique in the set of 99 gene deletion strains, and each bar code is surrounded by universal priming sites (yellow rectangles). The green rectangles represent FRT sites, which are FLP recombinase target sites that can facilitate removal of the marker at a latter time. Targeting constructs were transformed into E. coli BW25113 cells induced for λred recombination, and transformants were selected on LB-chloramphenicol plates to create gene deletion mutants. (B) DNA sequence analysis was performed on deletion mutant specific PCR products containing the insertion sites and molecular bar-codes for each integrated targeting construct. The DNA sequence results for molecular bar-coded ΔalkB and ΔuvrA demonstrated that the universal priming sites were identical in each gene deletion mutant while the bar-codes are unique to each. Each oligonucleotide can be tagged with Cy3 or Cy5 (green sphere) for use in microarray experiments.

We used both PCR and DNA sequence analysis to verify that each insert was in the correct genomic position and contained the correct molecular barcode (Fig. 1B). In general, the PCR product of a properly inserted targeting construct was ~ 1,300 base pairs, and contained the 5’ and 3’ insertion sites (Fig. 1B), both molecular bar-codes and the chloramphenicol resistance gene. Most targeted genes were either smaller or larger than 1,300 base pairs and we used the size of the PCR product to initially validate gene deletion mutants. Next, all PCR products were sequenced to identify the exact sequence context of the 5’ and 3’ insertion points and to verify that each mutant contained universally primed molecular bar-codes. The molecular bar-codes are unique DNA sequences that can be PCR amplified from universal priming sites. We have been able to generate bar-coded PCR products of 60 base pairs from both E. coli (untreated and MMS treated) pools, as well as pooled S. cerevisiae gene deletion strains (not shown); thus demonstrating that this PCR product is viable for microarray analysis. In all we sequence validated 99 unique molecular bar-coded gene deletion mutants (Table 1), and stored them in 96-well plates for further validation studies.

Table I.

Genes Targeted and Represented in Bar-Coded Deletion Set

| Name | Gene Function |

|---|---|

| ade | Cryptic adenine deaminase |

| alkA | 3-mentyI-adenine DNA glycosylase II, inducible; repairs by single-and double-strand excision of 3-methyI adenine |

| alkB | Alkylated DNA repair enzyme; alpha-ketoglutarate- and Fe(II)-dependent dioxygenase |

| arsB | Arsenite pump, inner membrane; resistance to arsenate, arsenite, and antimonite |

| artl | Periplasmic binding protein of Arg transport system |

| artJ | Periplasmic binding protein of Arg transport system |

| artM | Arg periplasmic transport system; similarity to transmembrane proteins, BPC ATPases |

| artP | Arg periplasmic transport system; similarity to transmembrane proteins, BPC ATPases |

| artQ | Arg periplasmic transport system; similarity to transmembrane proteins, BPC ATPases |

| b1841 | Function unknown |

| corA | Mg2+ (and other divalent metals) uptake transporter |

| cysK | Cysteine synthase A, O-acetylserine sulfhydrylase A |

| cysM | Cysteine synthase B, O-acetylserine sulfhydrylase B |

| dam | DNA-(adenine-N6)-methyltransferase |

| dcd | dCTP deaminase; mutants suppress lethal dut mutants |

| dinF | Induced by UV and mitomycin C, function unknown |

| dinG | ATP-dependent DNA helicase; putative repair and recombination enzyme |

| dinl | Stabilizes RecA filaments |

| dmsA | DMSO reductase subunit A, anaerobic, periplasmic |

| dnaJ | Dnak co-chaperone; stress-related DNA biosynthesis |

| emrA | EmrAB-TolC multidrug resistance pump |

| emrB | EmrAB-TolC multidrug resistance pump |

| emrK | EmrKY-TolC multidrug resistance efflux pump |

| emrY | EmrKY-TolC multidrug resistance efflux pump |

| endA | DNA-specific endonuclease I |

| exoX | Exonuclease X; 3'–5' DNase |

| qpt | Guanine-xanthine phosphoribosyltransferase phosphotransferase |

| gsk | Guanosine kinase |

| guaA | GMP synthase |

| gyrA | DNA gyrase, subunit A |

| helD | ATP-dependent DNA Helicase IV |

| hpt | Hypoxanthine-guanine phosphoribsoyltransferase |

| hscA | Hsc66, Dnak-lie chaperone |

| katE | Catalase hydroperoxidase II |

| mdtM | Multidrug resistance efflux protein |

| mntH | Mn(2+) transporter, role in bacterial response to reactive oxygen species |

| moeA | Molybdopterin (MPT) synthesis; incorporation of molybdenum into MPT; chlorate resistance |

| moeB | Molybdopterin-synthase sulfurylase; probable adenylation/thiocarboxylation of MoaD C-terminus |

| mog | Molybdochelatase incorporating molybdenum into molybdopterin |

| mutH | Methyl-directed mismatch repair |

| mutL | Methyl-directed mismatch repair |

| mutM | Formamidopyrimidine-DNA glycosylase/AP lyase; 5'-terminal deoxyribophodiesterase; DNA repair; GC to TA |

| mutS | Methyl-directed mismatch repair protein |

| mutT | 8-oxo-dGTPase, antimutator; prevents AT-to-GC transversions; dGTP pyrophosphohydrolase |

| mutY | adenine glycosylase, G-A repair, 2-hydroxyadenine DNA glycosylase |

| nei | DNA glycosylase/apurinic lyase, deoxyinosine-specific; endonuclease VIII |

| nfi | Endonuclease V, specific for single-stranded DNA or duplex DNA with damage |

| nfo | AP endodeoxyribonuclease IV; member of soxRs regulon; endonuclease IV |

| nrdD | Ribonucleoside triphosphate reductase, class III, anaerobic |

| nrdE | Ribonucleoside diphosphate reductase 2, subunit alpha, class I |

| nrdF | Ribonucleoside diphosphate reductase 2, subunit beta, class I |

| nrdG | Ribonucleotide reductase activase, generating glycyl radical |

| nth | Endonuclease III, DNA glycosylase/apyrimidinic (AP) lyase |

| ogt | O6-methylguanine-DNA methyltransferase |

| oxyR | Bifunctional regulatory protein sensor for oxidative stress |

| polB | DNA polymerase II, capable of translesion synthesis; role in the resumption of DNA synthesis after UV irradiation |

| purA | Adenylosuccinate synthase, purine synthesis |

| purR | Purine regulon repressor |

| recA | Gerneral recombination and DNA repair; pairing and strand exchange; role in cleavage of LexA repressor, SOS mutagenesis |

| recB | RecBCD Exonuclease V subunit |

| recC | RecBCD Exonuclease V subunit |

| recD | RecBCD Exonuclease V subunit |

| recE | RecET recombinase, exonuclease VIII, Rac prophage; recombination and repair; degrades one strand 5'-3' in duplex DNA |

| recF | Recombination and repair |

| recG | Junction-specific ATP-dependent DNA helicase |

| recJ | ssDNA 5'-3' exonuclease involved in recombination |

| recN | Recombination and repair |

| recO | Conjugational recombination and DNA repair |

| recR | Recombination and DNA repair |

| recT | RecET recombinase, annealing protein, Rac prophage; recombination and repair |

| rihC | Ribonucleoside hydrolase |

| rob | OriC-binding protein, binds to right border of oriC |

| rusA | Endonuclease, Holliday structure resolvase, DLP 12 prophage |

| ruvB | DNA helicase driving branch migration during recombination; hexameric ring |

| sbcB | Exonuclease I |

| sbcC | DNA hairpin dsDNA 3'-exonuclease SbcCD |

| sbcD | DNA hairpin dsDNA 3'-exonuclease SbcCD |

| sodA | Superoxide dismutase |

| sodB | Superoxide dismutase |

| sodC | Superoxide dismutase, Cu, Zn, periplasmic |

| soxR | Regulatory protein of soxRS regulon; induces sox regulon when superoxide levels increase |

| tag | 3-methyladenine DNA glycosylase I |

| topA | Topoisomerase I |

| topB | Topoisomerase III |

| tus | DNA contrahelicase, terminus utilization substance |

| ung | Uracil DNA glycosylase (UDG), excise uracil from DNA by base flipping mechanism; prefers ssDNA over dsDNA |

| upp | Uracil phosphoribosyltransferase |

| uvrA | Excision nuclease subunit A; repair of UV damage to DNA |

| uvrB | Excision nuclease subunit B, ATPase I and helicase II |

| uvrC | Excision nuclease subunit C; repair of UV damage to DNA |

| uvrD | ATP-dependent 3'-5' DNA helicase II |

| uvrY | Response regulator |

| xerC | Tyrosine recombinase XerCD resolves chromosome dimers |

| xerD | Tyrosine recombinase XerCD resolves chromosome dimers |

| xseA | Exonuclease VII, large subunit |

| ygdG | Ssb-binding protein |

| ygfO | Xanthine transporter |

| ygfU | Function unknown |

| ykfG | Function unknown, CP4-6 putative prophage remnanta |

2.2 Competitive growth experiments identify seven sets of bar-codes depleted from MMS treated pools

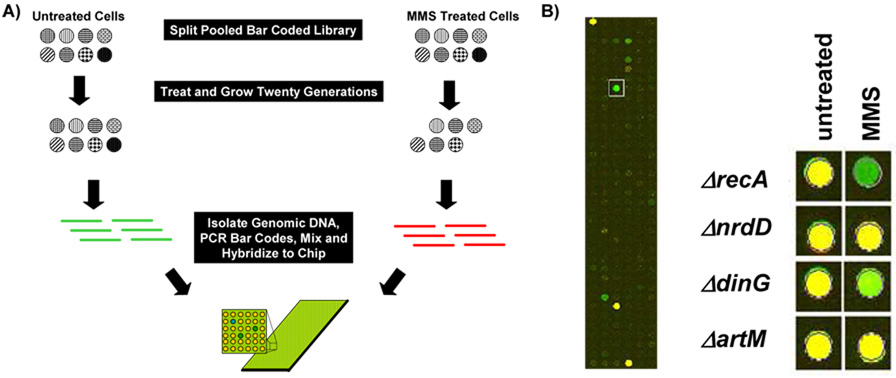

Experiments utilizing libraries of pooled bar coded yeast and human mutants or knock-downs have been used to identify gene products vital to growth after some perturbation [55, 59, 62, 68]. The basic premise is that in a pooled sample containing bar-coded gene deletion mutants those mutants whose growth is reduced by the presence of a chemical agent will be depleted relative to a reference sample (Fig. 2A). Depletion is monitored by PCR amplification of molecular bar-codes from both untreated and treated pools, using Cy3 and Cy5 labelled primers, followed by hybridization to a bar-code specific microarray. We performed proof of principle experiments using our molecular bar-coded E. coli gene deletion mutants to demonstrate that this approach is feasible in bacteria. E. coli gene deletion mutants were pooled, split in two, and then grown in liquid media for six hours, with either mock or chronic exposure to 0.015% MMS. The microarray we used was designed for use in the analysis of ~11,000 bar-codes found in the S. cerevisiae gene deletion library, but because we used yeast bar-codes in our E. coli gene deletion strains, this resource was compatible. We mixed amplified Cy3 and Cy5 labelled PCR products derived from both untreated and treated pools, which in theory were 198 total bar-codes, and performed microarray analysis to identify mutants that grew poorly in MMS, relative to untreated samples. 319 bar-code specific spots hybridized to the microarray, with 2 to 12 features specific to each set of deletion mutants bar-codes. Mutants that grew equally well in both the untreated (green) and treated (red spot) pools were represented as yellow spots on the microarray, while those that grew poorly in MMS were indicated by green spots (Fig. 2B; Supplemental Table S2).

Figure 2. Pooled Experiments with a Microarray Readout.

(A) Theoretical pooled competitive growth experiments using eight molecular bar-coded gene-deletion mutants. In theory the two MMS sensitive mutants will be depleted from the pool after exposure. DNA purified from untreated and MMS-treated pools can then be used in conjunction with Cy3 and Cy5 labeled primers to amplify molecular bar-codes from each pool. The amount of each bar-code in the pools can then be determined by mixing the amplified products, followed by hybridization to a bar-code specific microarray. Green spots on the microarray represent bar-codes depleted in the MMS treated pool relative to untreated samples. (B) We exposed a pool containing 99 molecular bar-coded gene deletion mutants to 0.015% MMS for six hours and then purified total DNA for use in PCR reactions. Cy3 and Cy5 labeled products from the untreated (green) and treated (red) pools were then mixed and hybridized to an Agilent custom array. (Left) A close up of the hybridized microarray with a ΔrecA specific bar-code indicated by a box. (Right) Results for ΔrecA, ΔnrdD, ΔdinG, and ΔartM from hybridizations of untreated vs. untreated (untreated) and untreated vs. MMS treated (MMS) pools. Yellow spots represent bar-codes found at equal levels in each pool, while green spots represent bar-codes enriched in the untreated pool relative to MMS. Note that most spots on the microarray are blank, as only a small fraction of the potential bar codes were utilized by the 99 strains in the E. coli deletion set.

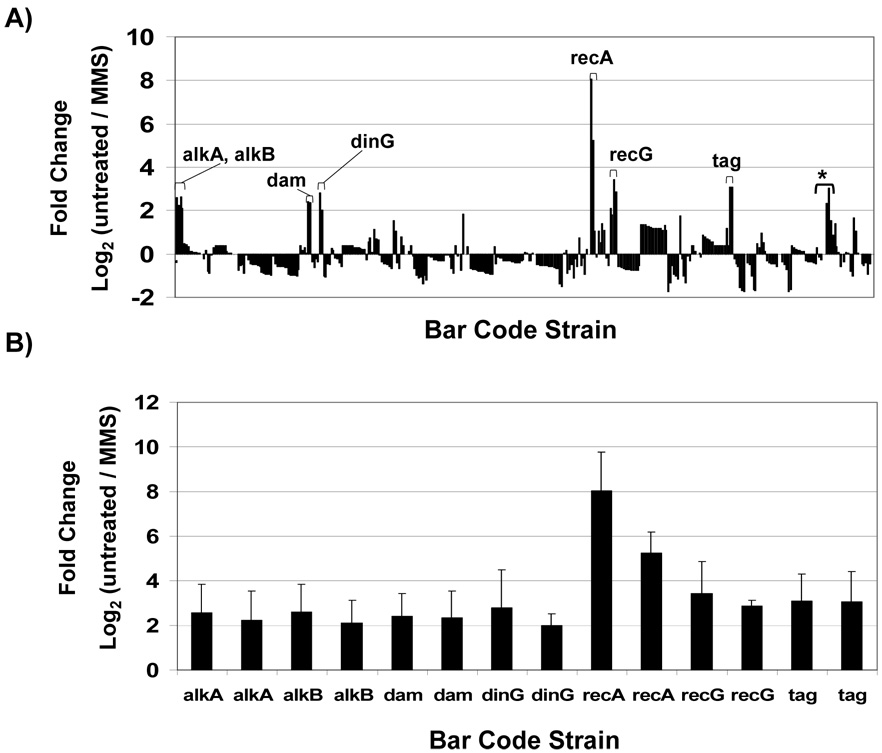

We normalized the data to adjust for intensity differences between the fluors and we used the following criteria to identify MMS sensitive strains; both up and down molecular bar-codes were required to have log2 fold differences ≥2 (untreated / MMS-treated), and reside in probes that showed minimal fluctuation in self-self hybridizations. Those spots (41) that were variable (>2-fold) in untreated vs. untreated hybridizations were scattered among the mutants such that only one was affected in our initial MMS sensitivity analysis (ΔuvrD, 2 total probes, 1 reliable and 1 variable) and two were removed from the final analysis (ΔrecB and Δgsk, two probes each, with both variable). The log2 change ≥2 (Fig. 3A) equates to a 4-fold change on the linear scale. We identified ΔrecA barcodes that had log2 values of untreated / treated = 6.6 +/− 0.7, which is ~100-fold change on the linear scale. In all we identified seven gene deletion strains that were significantly (T-test < 10−7) depleted in the MMS treated pool, relative to the untreated pool, with ΔrecA > ΔrecG > Δtag > ΔdinG > ΔalkA > Δdam > ΔalkB (Fig. 3B). The corresponding proteins participate in direct (AlkB), base excision (Tag and AlkA), recombination (RecA, RecG, and DinG) and mismatch repair (Dam) pathways, all of which are known to repair alkylated DNA [2]. We have designated ΔartM [log2 (untreated / treated) = 0.19], ΔnrdD [log2 (untreated / treated) = −0.01], and ΔsodB [log2 (untreated / treated) = −0.07] as our wild-type surrogates, due to their ability to grow equally well in untreated and MMS treated conditions, in both pooled liquid and plate-based formats, which is similar to wild-type. It is important to realize that pooled experiments do not use an authentic wild-type strain, because bar-codes are added upon the deletion of a gene; thus we performed individual liquid growth and plate based MMS assays to identify wild-type surrogates.

Figure 3. Bar-codes Depleted After MMS Treatment.

(A) Normalized intensity values for Cy3 and Cy5 tagged bar-codes were used to generate average fold change [log2 (untreated / MMS-treated)] data for all bar-codes used in MMS-competitive growth experiments. Fold changes specific to features on the microarray are plotted with each set of bar-codes represented by 2 to 12 features. The up and downstream bar-codes that were ≥ 2-fold enriched in the untreated vs. MMS treated pool were used to identify seven MMS-sensitive mutants. (*) Two bar codes specific to uvrD mutants that show a greater than 2-fold change, with one bar code being highly variable in untreated verse untreated hybridizations. (B) Bar-code specific fold changes and standard deviations for the seven identified MMS sensitive mutants (ΔalkA, ΔalkB, Δdam, ΔdinG, ΔrecA, ΔrecG, and Δtag).

2.3 Microarray- and plate-based screens identified overlapping and distinct gene-deletion strains sensitive to MMS

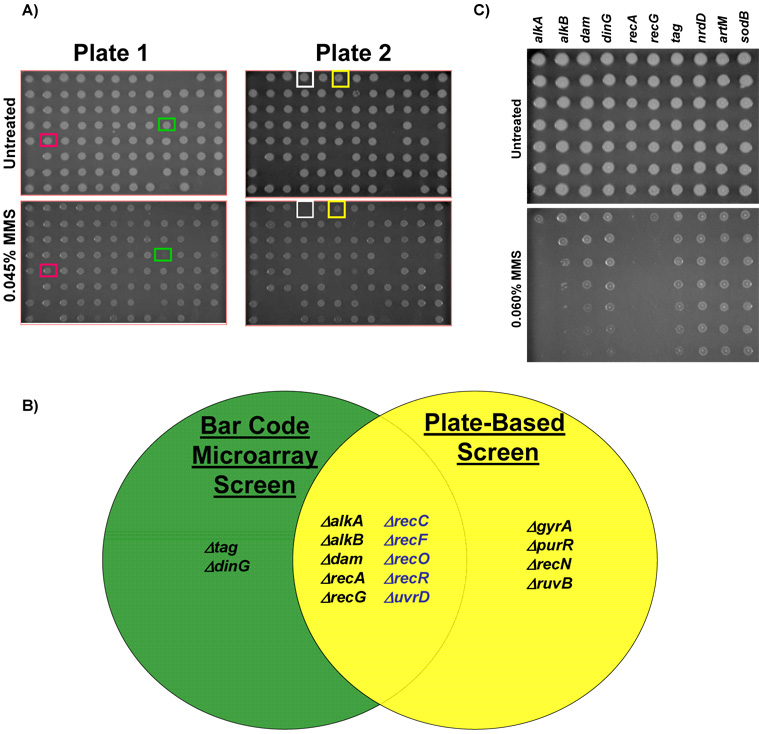

In order to perform a global comparison of plate based sensitivity to microarray classified MMS-sensitivity we have robotically spotted all 99 bar coded mutants on agar plates containing increasing concentrations of MMS (Fig. 4A). Our robotic spotting approach on plates identified 14 MMS sensitive mutants (ΔalkA, ΔalkB, Δdam, ΔrecA, ΔrecG, ΔgyrA, ΔpurR, ΔrecN, ΔruvB, ΔrecC, ΔrecF, ΔrecO, ΔrecR, and ΔuvrD). In all we determined that if we relaxed our microarray cut-off to a log2 change ≥1 (i.e. 2-fold on a linear scale) there was a 95% overlap in the data. In contrast to the microarray results, the plate based screen identified ΔgyrA, ΔpurR, ΔrecN, and ΔruvB mutants as MMS sensitive, with classification discrepancies attributed to different growth conditions for each assay (Fig. 4B). Using our robotic spotting approach we did not identify Δtag or ΔdinG bar-coded mutants as MMS sensitive. We have further validated this finding using the four Δtag or ΔdinG mutants from the Keio library in plate based MMS assays (data not shown).

Figure 4. Classification of MMS Sensitive Gene Deletion Mutants Using Plate-based Assays.

(A) Robotic spotting of bar-coded mutants on increasing concentrations of MMS. The plate key can be found in supplementary table S3 with rows labelled A to H and columns 1 to 12. Representative MMS sensitive mutants; ΔgyrA (green box) and ΔalkB (white box) as well as well two no phenotype mutants Δtag (red box) and ΔdinG (yellow box), which surprisingly exhibited no phenotype in this assay. (B) A Venn diagram illustrating the overlap of results from plate and microarray based screens. Mutants displayed in blue represent MMS sensitive mutants identified with a relaxed criterion [log2 (untreated / MMS-treated) ≥ 1-fold] in the microarray screen. (C) Overnight cultures of each microarray classified MMS sensitive mutant were 10-fold serially diluted and 5 ul aliquots were spotted on LB-chloramphenicol plates (−/+ 0.015% MMS). Plates were incubated for 16 hours at 37°C and then digitally imaged. Gene delet ion mutants classified as MMS sensitive on plates were identified using the three wild-type surrogates (ΔnrdD, ΔartM, ΔsodB) and verified against wild-type BW25113 (not shown). Gene deletion strains classified as MMS-sensitive on these plates were ΔalkA, ΔalkB, Δdam, ΔrecA, and ΔrecG.

In order to further validate our microarray data we performed plate-based MMS sensitivity studies on all the MMS sensitive mutants identified by microarray analysis (ΔalkA, ΔalkB, Δdam, ΔdinG, ΔrecA, ΔrecG, and Δtag) and wild-type surrogates (ΔartM, ΔnrdD, and ΔsodB)(Fig. 4C). We spotted 5 ul of a ten-fold dilution series of saturated cultures on LB plates and LB plates containing MMS, incubated the plates for 16 hours and identified the last dilution in which each mutant grew on the MMS containing plates. The 16 hour time point image is the earliest image where the control strains show growth at the highest dilution. In addition, the 16-hour image is representative of all the time points recorded (20 and 24 hours, data not shown). We demonstrated that ΔalkA, ΔalkB, Δdam, ΔrecA, and ΔrecG are sensitive to MMS, relative to wild-type surrogates. Similar to our microarray screen ΔalkA, ΔrecA and ΔrecG mutants appear to be highly sensitive to MMS. Surprisingly, both ΔdinG and Δtag mutants appear to grow normally on MMS-pates, further supporting our observed discrepancy between the results generated by microarray and plate-based screening methods.

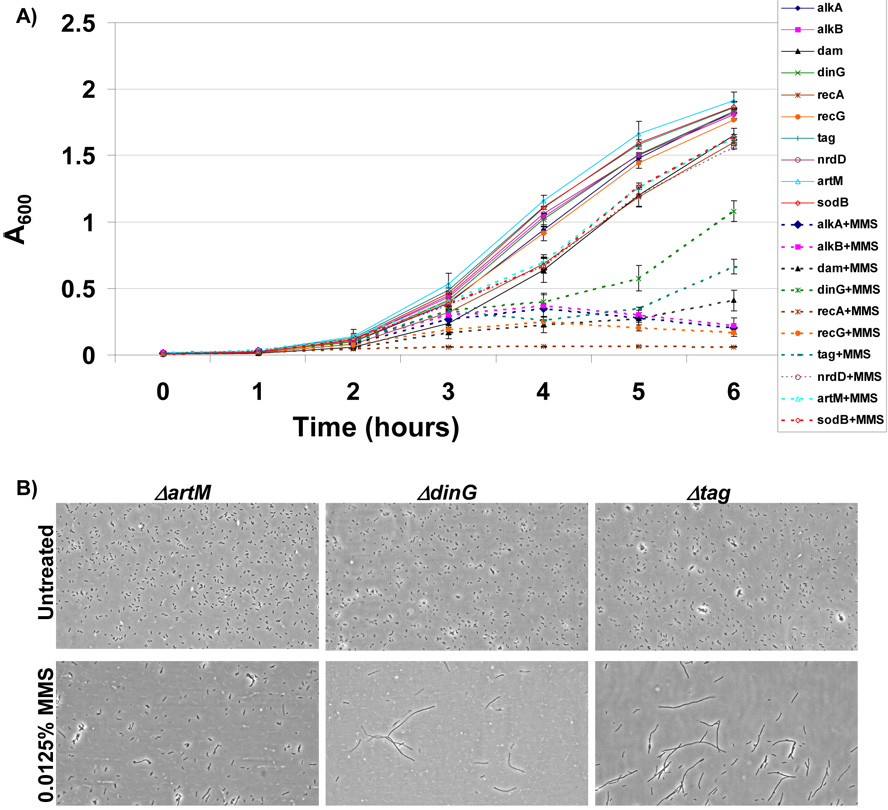

2.4 MMS-growth curves validate microarray based classifications of MMS-sensitive mutants

The discrepancy between plate- and microarray-based results warranted further investigation. To investigate the cause of this discrepancy we randomly picked 10 mutants (ΔhscA, ΔnrdF, ΔcysM, ΔemrK, ΔradC, ΔcorA, ΔkatE, Δhpt, ΔdmsA, and Δdcd) (data not shown) and measured growth in liquid medium in the absence or presence of MMS. These conditions mimic those used for pooled microarray screens, except that the growth of all mutants was individually analyzed using absorbance measurements at 600 nm. Each of the ten randomly picked mutants (ΔhscA, ΔnrdF, ΔcysM, ΔemrK, ΔradC, ΔcorA, ΔkatE, Δhpt, ΔdmsA, and Δdcd) grew equally well in the presence and absence of MMS (data not shown). Next we analyzed all of the MMS sensitive mutants identified by microarray analysis (ΔalkA, ΔalkB, Δdam, ΔdinG, ΔrecA, ΔrecG, and Δtag) and wild-type surrogates (ΔartM, ΔnrdD, and ΔsodB). Each of the ten strains grew at a similar rate in untreated medium. This was not the case for mutants exposed to MMS. We determined that in MMS containing medium the growth rates of ΔalkA, ΔalkB, Δdam, ΔdinG, ΔrecA, ΔrecG, and Δtag strains were reduced relative to wild-type surrogates (Fig. 5A). The six hour time point is representative of the conditions under which DNA was isolated for microarray analysis, thus our growth data supports the microarray results. The kinetics of growth for the Δtag and ΔdinG cells indicated that after ~5 hours of chronic MMS-treatment these cells re-initiate growth, as measured by absorbance measurements. Both mutants appear to partially adapt to MMS treatment at 5 hours and the increase in absorbance is indicative of more or larger cells. None the less, the MMS-growth curves agree with our microarray results and indicate that ΔdinG and Δtag cells display markedly reduced growth in liquid medium containing MMS relative to wild-type surrogates.

Figure 5. Measures of Growth and Filamentation in Identified MMS-Sensitive Mutants.

(A) The growth of MMS sensitive mutants identified by microarray analysis and wild-type surrogates was analyzed in LB-chloramphenicol −/+ 0.015% MMS. The growth of individual gene deletion mutants in untreated (solid lines) and MMS-treated media (dashed lines) was measured spectrophotometrically (A600) and plotted as a function of time. The six hour time point coincides with the endpoint used for microarray analysis and demonstrates that each of the MMS sensitive mutants identified by microarray analysis (ΔalkA, ΔalkB, Δdam, ΔdinG, ΔrecA, ΔrecG, and Δtag) was growth impaired in MMS containing media. (B) The cellular morphology of the MMS sensitive gene deletion mutants (ΔdinG and Δtag) and a wild-type like control (ΔartM) were analyzed from samples grown for 5 hours in LB-chloramphenicol −/+ 0.015% MMS. Cells were imaged on a Nikon TS-100 microscope at 40X magnification and demonstrated that ΔdinG and Δtag cells filament in response to MMS damage.

2.5 Δtag and ΔdinG cells filament in response to MMS

The rapid increase in absorbance for ΔdinG and Δtag cells after five hours of MMS exposure suggested that these cells adapt to DNA damage in some way. We analyzed the morphology of Δtag and ΔdinG cells, and the wild-type like control ΔartM, for 5 hour mock and MMS treated cells. The morphology of all cells grown in untreated medium was similar, and they all exhibited the rod shaped morphology of E. coli. We determined that in the presence of MMS Δtag and ΔdinG cells filament extensively (Fig. 5B), with filamentation a process by which cell size increases at the expense of DNA content. The MMS-induced filamentation of ΔdinG and Δtag cells can account for the increase in absorbance observed at 5-hours post MMS treatment, and suggests a mechanism by which these cells survive DNA damage. Importantly, the MMS-induced filamentation phenotype observed in the Δtag and ΔdinG cells can explain the discrepancy between plate- and microarray-based screens, as plate based screens use visual analysis of colony size after 16-hours of growth to assign phenotype, while microarray screens utilize DNA concentration at 6-hours.

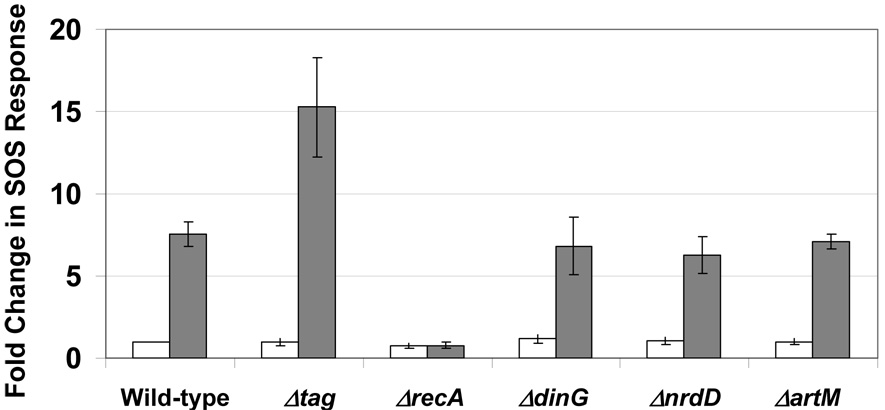

2.6 Δtag mutants were hyper-SOS after MMS treatment

The MMS-induced filamentation phenotype observed for Δtag and ΔdinG cells prompted us to examine the induction of the SOS response in each cell type (Fig. 6). We reasoned that unrepaired DNA damage should be promoting filamentation. We used a sulA-GFP reporter to demonstrate that Δtag cells have a hyperactive SOS response after MMS treatment and induce GFP levels 2-fold higher than wild-type and the wild-type surrogates used in our study. This result is in agreement with a published study which suggested that unrepaired 3-methyladenine lesions are potent inducers of the SOS response [69]. We also analyzed the MMS induced SOS response in ΔdinG cells and determined that ΔdinG cells have wild-type like activation of the sulA-GFP reporter. It is surprising that in ΔdinG cells the MMS induced level of the sulA reporter is similar to wild-type, as ΔdinG cells undergo extensive filamentation after MMS treatment.

Figure 6. MMS Induced SOS Reporter Studies in Δtag and ΔdinG Mutants.

Wild-type (BW25113), the wild-type surrogates (ΔnrdD, ΔartM), ΔrecA, Δtag and ΔdinG were transformed with the SOS reporter plasmid (SulA-GFP) and transformants were grown in LB to exponential phase and either mock or MMS treated (0.015% MMS) for 30 minutes. Cells were washed in PBS and 30,000 cells were analyzed by FACS analyses to quantitate GFP levels. Intensity levels were determined for each sample and all changes were determined relative to untreated wild-type. The results of replicate experiments are plotted with error bars representing standard deviations.

3. Discussion

Previous studies in both liquid and plate-based assays have demonstrated that components of direct, base excision, mismatch and recombinational repair are needed for survival after MMS-induced DNA damage [16, 18, 49, 56, 70–74]. Using a microarray based screen and highly stringent criteria (≥ 2-fold, on the log2 scale) we classified strains deficient in direct repair (ΔalkB), base excision repair (Δtag, ΔalkA), mismatch (Δdam) and recombinational repair (ΔrecA, ΔrecG, and ΔdinG) as MMS-sensitive. If we relaxed the stringency and included those bar-codes in the MMS treated pool that decrease ≥ 1-fold on the log2 scale (i.e. 2-fold reduction on the liner scale) we can increase the number of MMS sensitive mutants by including ΔrecD, ΔrecF, ΔrecO, ΔrecD, and ΔuvrD; with a majority belonging to DNA recombination pathways. Experimentally we have demonstrated that pooled competitive growth experiments are feasible using our set of 99 bar-coded strains and we have been able to exploit an existing microarray resource for our analysis. Further, our results demonstrate that molecular bar-codes originally designed for S. cerevisiae can be transferred into E. coli en masse and used to tag gene deletion mutants. The fact that we could buy pre-made arrays, which were originally made for S. cerevisiae, afforded a significant cost savings and provides a model for bar-code based experiments in other microbes used in systems biology studies.

We have demonstrated that microarray-screens can yield both overlapping and distinct results when compared to plate-based methods. These two complementary screening approaches have been extensively used in S. cerevisiae, with microarray based screens being a faster and more quantitative approach, while plate-based screens allow for high-throughput deletion mutant analysis in isolation. The main differences between these two methods lies in testing conditions (liquid vs. agar plate) and output measures (DNA content vs. colony size). Liquid medium and agar plates provide distinct environments in which to study E. coli, differing in bacterial growth rates and aeration. In theory the differences in growth rates, relative to MMS stability, could account for some discrepancies. Importantly, the output measures of DNA content and colony size can account for the discrepancy by which microarrays classified ΔdinG and Δtag as MMS sensitive, relative to plate-based results. Both ΔdinG and Δtag deletion strains are associated with known DNA alkylation repair pathways (RR and BER) [2, 75], so we were quite surprised that neither was identified in plate-based MMS experiments. These results are supported by similar findings using the four mutant deletion strains (two Δtag and two ΔdinG) found in the Keio library. Filamentation after MMS treatment provides a means by which ΔdinG and Δtag cells would not be detected on MMS plates, by growing bigger without replication of DNA, and the filamentation phenotype most likely accounts for the classification discrepancy between microarray and plate-based screens. Microarray analysis utilized DNA content to classify ΔdinG and Δtag strains as MMS sensitive, a result validated by growth curves. Unlike plate-based screens, microarrays are not influenced by morphological changes and serve as a reminder that multiple technologies should be used when performing high throughput screens.

Our use of comparative approaches to study the DNA damage response in E. coli have now provided us with a tool to efficiently identify genes products that influence growth after damage and a method to identify gene products that are required to prevent filamentation after DNA damage. Importantly it has allowed us to demonstrate that Δtag and ΔdinG cells filament in response to DNA damage. In general the disruption of DNA replication by damage will initiate an SOS response to repair or tolerate DNA damage and this will activate SulA to inhibit cell division. SulA, also known as Sfi, causes filamentation by binding to FtsZ to prevent septation [76]. A second pathway to promote filamentation has also been described and this SulA independent filamentation pathway is RecA and LexA dependent. The observation that this SulA independent filamentation pathway is LexA and RecA dependent suggests that the pathway will be comprised of damage inducible (din) genes, and Smith and co-workers have ruled out DinB, DinD, DinE and DinF as being components of the SulA-independent filamentation pathway [76]. We observed that ΔdinG cells and wildtype cells have a similar level of induction of sulA after MMS damage yet ΔdinG cell filament extensively. In addition, we have also shown that while Δtag and ΔdinG cells filament to similar levels after MMS damage, sulA expression in the Δtag cells is 2 fold higher than in ΔdinG cells. The decoupling of filamentation from sulA expression in the ΔdinG cells suggests that DinG is associated with the SulA-independent filamentation pathway. DinG could be a negative regulator of the SulA-independent filamentation pathway or DNA damage distinct to ΔdinG cells could be activating the sulA-independent filamentation pathway.

In conclusion we have developed a tool that can be used to study DNA repair and damage signalling pathways in E. coli. We have shown that microarray based screens can be used to derive distinct results in high throughput screens, and that tracking DNA content is an important parameter when measuring strain growth. Our bar-coded gene deletion mutants are compatible for use with the complete kanamycin based Keio gene deletion library, due to the use of a different selectable marker, and our resource has the potential to be used in epitasis and synthetic lethal studies. In addition, we believe that a complete bar-coded library will be a valuable and complimentary tool for microbe based System Biology studies. Importantly, our analysis has matched data from to two different growth assays, validated a set of gene deletion mutants, and demonstrated that ΔdinG cells display a distinct filamentation phenotype after DNA damage.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by grants to RPC (NIH NCRR1C06RR0154464 and GM46312) and to TJB (NYSTAR and NIH 1R01ES015037). Special thanks to members of the Gen*NY*Sis Center and Wadsworth NY State Public Health Laboratories for helpful comments. We are now taking suggestions on the next round of molecular bar coded gene deletion strains. Please E-mail tbegley@albany.edu to add your favorite gene to our priority list.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Balajee AS, Bohr VA. Genomic heterogeneity of nucleotide excision repair. Gene. 2000;250(1–2):15–30. doi: 10.1016/s0378-1119(00)00172-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Friedberg E, et al. DNA Repair and Mutagenesis. 2nd Edition. ASM Press; 2005. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Thacker J. The RAD51 gene family, genetic instability and cancer. Cancer Lett. 2005;219(2):125–135. doi: 10.1016/j.canlet.2004.08.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Lyakhovich A, Surralles J. Disruption of the Fanconi anemia/BRCA pathway in sporadic cancer. Cancer Lett. 2005 doi: 10.1016/j.canlet.2005.07.038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Liu Y, Kulesz-Martin M. p53 protein at the hub of cellular DNA damage response pathways through sequence-specific and non-sequence-specific DNA binding. Carcinogenesis. 2001;22(6):851–860. doi: 10.1093/carcin/22.6.851. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Hoeijmakers JH. Genome maintenance mechanisms for preventing cancer. Nature. 2001;411(6835):366–374. doi: 10.1038/35077232. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ilyas M, et al. Genetic pathways in colorectal and other cancers. Eur J Cancer. 1999;35(14):1986–2002. doi: 10.1016/s0959-8049(99)00298-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Elledge SJ. Cell cycle checkpoints: preventing an identity crisis. Science. 1996;274(5293):1664–1672. doi: 10.1126/science.274.5293.1664. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Tanaka K, Wood RD. Xeroderma pigmentosum and nucleotide excision repair of DNA. Trends in Biochemical Sciences. 1994;19(2):83–86. doi: 10.1016/0968-0004(94)90040-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Loeb LA. Mutator phenotype may be required for multistage carcinogenesis. Cancer Research. 1991;51(12):3075–3079. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Wei YF, Chen BJ, Samson L. Suppression of Escherichia coli alkB mutants by Saccharomyces cerevisiae genes. J Bacteriol. 1995;177(17):5009–5015. doi: 10.1128/jb.177.17.5009-5015.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Samson L, Derfler B, Waldstein EA. Suppression of human DNA alkylation-repair defects by Escherichia coli DNA-repair genes. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1986;83(15):5607–5610. doi: 10.1073/pnas.83.15.5607. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Rebeck GW, et al. A second DNA methyltransferase repair enzyme in Escherichia coli. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 1988;85(9):3039–3043. doi: 10.1073/pnas.85.9.3039. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Dinglay S, et al. Defective processing of methylated single-stranded DNA by E. coli AlkB mutants. Genes Dev. 2000;14(16):2097–2105. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kataoka H, Sekiguchi M. Molecular cloning and characterization of the alkB gene of Escherichia coli. Mol Gen Genet. 1985;198(2):263–269. doi: 10.1007/BF00383004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Falnes PO, Johansen RF, Seeberg E. AlkB-mediated oxidative demethylation reverses DNA damage in Escherichia coli. Nature. 2002;419(6903):178–182. doi: 10.1038/nature01048. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Aravind L, Koonin EV. The DNA-repair protein AlkB, EGL-9, and leprecan define new families of 2-oxoglutarate- and iron-dependent dioxygenases. Genome Biol. 2001;2(3) doi: 10.1186/gb-2001-2-3-research0007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Trewick SC, et al. Oxidative demethylation by Escherichia coli AlkB directly reverts DNA base damage. Nature. 2002;419(6903):174–178. doi: 10.1038/nature00908. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Duncan T, et al. Reversal of DNA alkylation damage by two human dioxygenases. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2002;99(26):16660–16665. doi: 10.1073/pnas.262589799. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Engelward BP, et al. A chemical and genetic approach together define the biological consequences of 3-methyladenine lesions in the mammalian genome. J Biol Chem. 1998;273(9):5412–5418. doi: 10.1074/jbc.273.9.5412. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Hilbert TP, et al. Cloning and expression of the cDNA encoding the human homologue of the DNA repair enzyme, Escherichia coli endonuclease III. J Biol Chem. 1997;272(10):6733–6740. doi: 10.1074/jbc.272.10.6733. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Berdal KG, et al. Cloning and expression in Escherichia coli of a gene for an alkylbase DNA glycosylase from Saccharomyces cerevisiae; a homologue to the bacterial alkA gene. EMBO. 1990;9:4563–4568. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1990.tb07909.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Bjoras M, et al. Purification and properties of the alkylation repair DNA glycosylase encoded by the MAG gene from Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Biochemistry. 1995;34(14):4577–4582. doi: 10.1021/bi00014a010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Boiteux S, TR OC, Laval J. Formamidopyrimidine-DNA glycosylase of Escherichia coli: cloning and sequencing of the fpg structural gene and overproduction of the protein. EMBO Journal. 1987;6(10):3177–3183. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1987.tb02629.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Chakravarti D, et al. Cloning and expression in Escherichia coli of a human cDNA encoding the DNA repair protein N-methylpurine-DNA glycosylase. J. Biol. Chem. 1991;266:15710–15715. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Hollis T, Lau A, Ellenberger T. Structural studies of human alkyladenine glycosylase and E. coli 3- methyladenine glycosylase. Mutat Res. 2000;460(3–4):201–210. doi: 10.1016/s0921-8777(00)00027-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Olsen LC, et al. Human uracil-DNA glycosylase complements E. coli ung mutants. Nucleic Acids Research. 1991;19:4473–4478. doi: 10.1093/nar/19.16.4473. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Weiss B, Cunningham RP. Genetic mapping of nth, a gene affecting endonuclease III (thymine glycol-DNA glycosylase) in Escherichia coli K-12. Journal of Bacteriology. 1985;162(2):607–610. doi: 10.1128/jb.162.2.607-610.1985. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Demple B, et al. Repair of alkylated DNA in Escherichia coli. Physical properties of O6- methylguanine-DNA methyltransferase. J Biol Chem. 1982;257(22):13776–13780. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Manuel RC, Lloyd RS. Cloning, overexpression, and biochemical characterization of the catalytic domain of MutY. Biochemistry. 1997;36(37):11140–11152. doi: 10.1021/bi9709708. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Porello SL, Leyes AE, David SS. Single-turnover and pre-steadystate kinetics of the reaction of the adenine glycosylase MutY with mismatch-containing DNA substrates. Biochemistry. 1998;37(42):14756–14764. doi: 10.1021/bi981594+. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Sobol RW, et al. Base excision repair intermediates induce p53-independent cytotoxic and genotoxic responses. J Biol Chem. 2003;278(41):39951–39959. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M306592200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Sancar A, Franklin KA, Sancar GB. Escherichia coli DNA photolyase stimulates UvrABC excision nuclease in vitro. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences USA. 1984;81(23):7397–7401. doi: 10.1073/pnas.81.23.7397. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Seeberg E, Steinum AL. Purification and properties of the uvrA protein from Escherichia coli. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 1982;79(4):988–992. doi: 10.1073/pnas.79.4.988. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Van Houten B, McCullough A. Nucleotide excision repair in E. coli. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 1994;726:236–251. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-6632.1994.tb52822.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Voigt JM, et al. Repair of O6-methylguanine by ABC excinuclease of Escherichia coli in vitro. J Biol Chem. 1989;264(9):5172–5176. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Van Houten B, et al. Action mechanism of ABC excision nuclease on a DNA substrate containing a psoralen crosslink at a defined position. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1986;83(21):8077–8081. doi: 10.1073/pnas.83.21.8077. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Tang M, et al. Biochemical basis of SOS-induced mutagenesis in Escherichia coli: reconstitution of in vitro lesion bypass dependent on the UmuD'2C mutagenic complex and RecA protein. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 1998;95(17):9755–9760. doi: 10.1073/pnas.95.17.9755. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Doiron KM, et al. Overexpression of vsr in Escherichia coli is mutagenic. J. Bacteriol. 1996;178(14):4294–4296. doi: 10.1128/jb.178.14.4294-4296.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Modrich P. Mismatch repair, genetic stability and tumour avoidance. Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society of London - Series B: Biological Sciences. 1995;347(1319):89–95. doi: 10.1098/rstb.1995.0014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Fishel R, et al. The human mutator gene homolog MSH2 and its association with hereditary nonpolyposis colon cancer. Cell. 1993;75(5):1027–1038. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(93)90546-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Glickman BW, Radman M. Escherichia coli mutator mutants deficient in methylation-instructed DNA mismatch correction. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 1980;77(2):1063–1067. doi: 10.1073/pnas.77.2.1063. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Plosky B, et al. Base excision repair and nucleotide excision repair contribute to the removal of N-methylpurines from active genes. DNA Repair (Amst) 2002;1(8):683–696. doi: 10.1016/s1568-7864(02)00075-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Spek EJ, et al. Nitric oxide-induced homologous recombination in Escherichia coli is promoted by DNA glycosylases. J Bacteriol. 2002;184(13):3501–3507. doi: 10.1128/JB.184.13.3501-3507.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Spek EJ, et al. Recombinational repair is critical for survival of Escherichia coli exposed to nitric oxide. J Bacteriol. 2001;183(1):131–138. doi: 10.1128/JB.183.1.131-138.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Kenyon CJ, Walker GC. DNA-damaging agents stimulate gene expression at specific loci in Escherichia coli. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1980;77(5):2819–2823. doi: 10.1073/pnas.77.5.2819. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Blattner FR, et al. The complete genome sequence of Escherichia coli K-12. Science. 1997;277(5331):1453–1474. doi: 10.1126/science.277.5331.1453. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Chang M, et al. A genome-wide screen for methyl methanesulfonate-sensitive mutants reveals genes required for S phase progression in the presence of DNA damage. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2002;99(26):16934–16939. doi: 10.1073/pnas.262669299. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Begley TJ, et al. Hot spots for modulating toxicity identified by genomic phenotyping and localization mapping. Mol Cell. 2004;16(1):117–125. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2004.09.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Haugen AC, et al. Integrating phenotypic and expression profiles to map arsenic-response networks. Genome Biol. 2004;5(12):R95. doi: 10.1186/gb-2004-5-12-r95. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Said MR, et al. Global network analysis of phenotypic effects: protein networks and toxicity modulation in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2004;101(52):18006–18011. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0405996101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Workman CT, et al. A systems approach to mapping DNA damage response pathways. Science. 2006;312(5776):1054–1059. doi: 10.1126/science.1122088. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Huang ME, et al. A genomewide screen in Saccharomyces cerevisiae for genes that suppress the accumulation of mutations. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2003;100(20):11529–11534. doi: 10.1073/pnas.2035018100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Ross-Macdonald P, et al. Large-scale analysis of the yeast genome by transposon tagging and gene disruption. Nature. 1999;402(6760):413–418. doi: 10.1038/46558. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Giaever G, et al. Functional profiling of the Saccharomyces cerevisiae genome. Nature. 2002;418(6896):387–391. doi: 10.1038/nature00935. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Begley TJ, et al. Recovery Pathways in S. cerevisiae Revealed by Genomic Phenotyping and Interactome Mapping. Mol Canc Res. 2002;1 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Bennett CB, et al. Genes required for ionizing radiation resistance in yeast. Nat Genet. 2001;29(4):426–434. doi: 10.1038/ng778. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Marston AL, et al. A genome-wide screen identifies genes required for centromeric cohesion. Science. 2004;303(5662):1367–1370. doi: 10.1126/science.1094220. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Giaever G, et al. Chemogenomic profiling: identifying the functional interactions of small molecules in yeast. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2004;101(3):793–798. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0307490100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Deutschbauer AM, et al. Mechanisms of haploinsufficiency revealed by genome-wide profiling in yeast. Genetics. 2005;169(4):1915–1925. doi: 10.1534/genetics.104.036871. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Gassner NC, et al. Accelerating the discovery of biologically active small molecules using a high-throughput yeast halo assay. J Nat Prod. 2007;70(3):383–390. doi: 10.1021/np060555t. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Lee W. Genome-wide requirements for resistance to functionally distinct DNA-damaging agents. PLoS Genet. 2005;1(2):e24. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.0010024. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Lum PY, et al. Discovering modes of action for therapeutic compounds using a genome-wide screen of yeast heterozygotes. Cell. 2004;116(1):121–137. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(03)01035-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Baba T, et al. Construction of Escherichia coli K-12 in-frame, single-gene knockout mutants: the Keio collection. Mol Syst Biol. 2006;2:2006 0008. doi: 10.1038/msb4100050. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Datsenko KA, Wanner BL. One-step inactivation of chromosomal genes in Escherichia coli K-12 using PCR products. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2000;97(12):6640–6645. doi: 10.1073/pnas.120163297. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Shoemaker DD, et al. Quantitative phenotypic analysis of yeast deletion mutants using a highly parallel molecular bar-coding strategy. Nat Genet. 1996;14(4):450–456. doi: 10.1038/ng1296-450. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Ooi SL, Shoemaker DD, Boeke JD. A DNA microarray-based genetic screen for nonhomologous end-joining mutants in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Science. 2001;294(5551):2552–2556. doi: 10.1126/science.1065672. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Paddison PJ, et al. A resource for large-scale RNA-interference-based screens in mammals. Nature. 2004;428(6981):427–431. doi: 10.1038/nature02370. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Boiteux S, Huisman O, Laval J. 3-Methyladenine residues in DNA induce the SOS function sfiA in Escherichia coli. EMBO. 1984;3:2569–2573. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1984.tb02175.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Kataoka H, Yamamoto Y, Sekiguchi M. A new gene (alkB) of Escherichia coli that controls sensitivity to methyl methane sulfonate. Journal of Bacteriology. 1983;153(3):1301–1307. doi: 10.1128/jb.153.3.1301-1307.1983. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Chen J, Derfler B, Samson L. Saccharomyces cerevisiae 3-methyladenine DNA glycosylase has homology to the AlkA glycosylase of E. coli and is induced in response to DNA alkylation damage. Embo J. 1990;9(13):4569–4575. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1990.tb07910.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Clarke ND, Kvaal M, Seeberg E. Cloning of Escherichia coli genes encoding 3-methyladenine DNA glycosylases I and II. Molecular & General Genetics. 1984;197(3):368–372. doi: 10.1007/BF00329931. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Marinus MG, Morris NR. Pleiotropic effects of a DNA adenine methylation mutation (dam-3) in Escherichia coli K12. Mutat. Res. 1975;28(1):15–26. doi: 10.1016/0027-5107(75)90309-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Wang TC, Chang HY. Effect of rec mutations on viability and processing of DNA damaged by methylmethane sulfonate in xth nth nfo cells of Escherichia coli. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Comm. 1991;180(2):774–781. doi: 10.1016/s0006-291x(05)81132-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Rudd KE. EcoGene: a genome sequence database for Escherichia coli K-12. Nucleic Acids Res. 2000;28(1):60–64. doi: 10.1093/nar/28.1.60. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Hill TM, et al. sfi-independent filamentation in Escherichia coli Is lexA dependent and requires DNA damage for induction. J Bacteriol. 1997;179(6):1931–1939. doi: 10.1128/jb.179.6.1931-1939.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.