Abstract

Objective

Tort reform may affect health insurance premiums both by reducing medical malpractice premiums and by reducing the extent of defensive medicine. The objective of this study is to estimate the effects of noneconomic damage caps on the premiums for employer-sponsored health insurance.

Data Sources/Study Setting

Employer premium data and plan/establishment characteristics were obtained from the 1999 through 2004 Kaiser/HRET Employer Health Insurance Surveys. Damage caps were obtained and dated based on state annotated codes, statutes, and judicial decisions.

Study Design

Fixed effects regression models were run to estimate the effects of the size of inflation-adjusted damage caps on the weighted average single premiums.

Data Collection/Extraction Methods

State tort reform laws were identified using Westlaw, LEXIS, and statutory compilations. Legislative repeal and amendment of statutes and court decisions resulting in the overturning or repealing state statutes were also identified using LEXIS.

Principal Findings

Using a variety of empirical specifications, there was no statistically significant evidence that noneconomic damage caps exerted any meaningful influence on the cost of employer-sponsored health insurance.

Conclusions

The findings suggest that tort reforms have not translated into insurance savings.

Keywords: Medical malpractice, damage caps, employer-sponsored health insurance

While the call for federal medical malpractice reforms has cooled with the change in leadership in the Congress (Young 2007), the American Medical Association and nine other physician organizations continue to identify tort reform as a key element in reforming the U.S. health care system (AMA 2007). The Bush Administration has proposed legislation to impose a $250,000 national cap on noneconomic damage awards and many state legislatures continue to consider limits on the size of medical malpractice awards.

Limits on damage awards are designed to reduce the liability of health care providers. Health care consumers are implicitly asked to accept restrictions in their legal rights in exchange for lower health care costs. The public evidently believes that malpractice litigation is a significant cause of rising health insurance premiums. In a 2006 survey of small business owners, 71 percent indicated that malpractice lawsuits were a significant cause of rising premiums. This percentage was larger than the responses for any other reported option (Medical Benefits 2007).

Surprisingly, no rigorous research has examined whether insurance purchasers have realized cost savings due to changes in tort law. This study begins to bridge that gap in knowledge by examining the effects of limitations on medical malpractice damage awards on employer-sponsored health insurance premiums over the 1999–2004 period. While other tort reforms have been adopted in many states there is virtually no empirical evidence that they have affected malpractice insurance premiums (Nelson, Kilgore, and Morrisey 2007). In brief, this study finds no evidence that limits on noneconomic damages had statistically meaningful effects on health insurance premiums. This finding is robust to a number of alternative specifications and holds whether or not one includes other tort reforms.

BACKGROUND

The first “malpractice crisis” occurred in the mid-1970s. Beginning in 1975, many states enacted changes in tort law; perhaps most notable was California's Medical Injury Compensation Reform Act (MICRA). MICRA set a $250,000 cap on noneconomic damage awards along with other changes in tort law. A dozen other states adopted similar forms of tort reform in the 1970s (Nelson, Kilgore, and Morrisey 2007). It is worth noting that the lack of any inflation adjustments in the MICRA legislation makes its damage cap more restrictive each year. A $250,000 cap in 2004 dollars is the equivalent of a $71,200 cap in 1975 purchasing power.

The second crisis occurred in the mid-1980s. Posner (1986) reports that malpractice premiums increased by 20–40 percent overall in 1984 and by 50–100 percent in some areas. State tort law changes were more general and less targeted on medical malpractice issues (Sloan, Bovbjerg, and Githerns 1991). In particular, a number of states enacted caps on noneconomic damages or revisited their earlier statutes.

The most recent crisis began with steep premium increases in 2002. Medical Liability Monitor (2005) reported increases of 10–49 percent, depending upon specialty, in 2003 and 7–25 percent in 2004 after several years when increases were little more than the rate of inflation. In response some 34 states considered tort reforms in 2003 alone (Madigan 2003).

The economic theory of torts and tort reform has been well summarized by Danzon (2000). The intent of tort law is to provide incentives for providers to deliver optimally efficient care. In a world of full knowledge and costless exchange, under the Coase Theorem the assignment of liability would be arbitrary and it would always be cheaper not to commit negligent acts.

If liability were assigned to the provider, he or she would have to compensate patients for any losses arising through negligence. If liability were assigned to the patients they would pay for additional care in the event of a negligent act. Because the negligent act always entails additional costs of care, the negligence is costlessly observed, and the contract costlessly enforced, it would always be cheaper not to commit negligence.

With asymmetric information and imperfectly functioning courts and private markets, liability is assigned to the party with the greater knowledge—the provider. Thus, the rule of liability provides for a second-best incentive to physicians and other providers not to skimp on care.

However, there is uncertainty about the appropriate standard of care and with the determination of negligence both because of the actual characteristics of individual patients and the state-of-the-art with respect to some clinical procedures and treatments. The assignment of liability and the uncertainty provide incentives for risk averse providers to deliver more than first-best optimal care. The incentives include more than just the monetary award he/she may be assessed in a finding of negligence. In addition, it includes the time and psychic costs associated with dealing with a claim of malpractice from allegation through negotiation, litigation and appeals, regardless of the outcome.

The resultant overprovision of care has come to be called defensive medicine. In this context, tort reforms can be interpreted as attempts to reduce the incentives for the overprovision of care. The specification of a maximum payment for noneconomic damages, for example, reduces the expected penalty for a potentially tortious act.

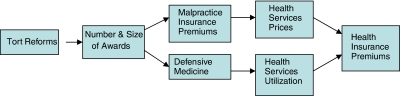

The logic of tort reforms can be summarized in Figure 1. Tort reforms are thought to reduce the number and size of malpractice awards. These reductions result in lower malpractice premiums and a reduction in the extent of defensive medicine. Lower malpractice premiums translate into lower prices for health services and the reduction in defensive medicine means that fewer tests and procedures are performed, implying a reduction in health services utilization. The reduction in prices and in utilization leads to lower health insurance premiums.

Figure 1.

Model of the Effects of Tort Reform on Health Insurance Premiums

If there are breaks along either path of causation, tort reforms will have reduced or nonexistent effects on health insurance premiums. There has been substantial empirical research on some of the linkages, only limited study of others, and no effort until now to examine the net effect of tort reform on health insurance premiums.

Effects of Tort Reform on Malpractice Insurance Premiums

There is growing empirical evidence that malpractice damage caps have resulted in lower malpractice insurance premiums (see Mello 2006; Nelson, Kilgore, and Morrisey 2007 for recent reviews). Zuckerman, Bovbjerg, and Sloan (1990) examined the effects of damage caps and other reforms, as well as the roles of investment returns, insurance regulation, and local population and medical care characteristics using 1974–1986 data on malpractice premiums from three specialties. They found that damage caps reduced premiums by 13.6–16.9 percent. Other reforms had smaller but statistically significant effects on premiums in some specifications as well.

Kessler and McClellan (1997) used 1985–1993 physician self-reported malpractice premium data to examine the effects of “direct” and “indirect” malpractice reforms on the rates of increases in premiums. Direct reforms included caps on damages, abolition of punitive damages, no mandatory prejudgment interest, and collateral source rule reform. They found that direct reforms worked with a lag. Three years after enactment, the growth of malpractice premiums in reform states was estimated to be 8.4 percent lower than in nonreform states. Indirect reforms had no impact.

A series of studies used aggregate malpractice insurance revenue at the state or state-insurer level. Over the 1985–1988 period Blackmon and Zeckhauser (B–Z) (1990) found that tort reforms reduced aggregate short-run premium revenue by 16.6 percent. Viscusi et al. (1993) found somewhat larger effects but were unable to find effects for individual reforms. Viscusi and Born (1995) examined the 1985–1991 period and concluded that states enacting “reforms” reduced firm-specific aggregate premium revenues by 12.4 percent. More recently Viscusi and Born (2004) revised their earlier analysis and found that states with caps on noneconomic damages reduced short-run premium income by 6.2 percent.

Thorpe (2004) also used the NAIC data, but for a much longer time period: 1985–2001. He used the B–Z approach, but added a new measure, the aggregate premium income per physician in the state. Thorpe found that states with either economic or noneconomic damage caps (or both) had aggregate premium incomes that were 17.1 percent lower and premium income per physician that was 12.2 percent lower. There was no statistically significant effect of prohibitions on punitive damages.

Danzon, Epstein, and Johnson (2004) used Medical Liability Monitor data to study the effects of tort reforms on premiums from the physician's perspective. Using 1994–2003 annual data on average premiums paid by internists, general surgeons and obstetricians by firm and state, they found that noneconomic damage caps below $500,000 reduced the change in premiums by 5.7 percent. Damage caps set at a higher level, and total damage caps had no statistically significant effects.

Finally, Kilgore, Morrisey, and Nelson (2006) used a full fixed effects model to examine tort reforms over the years 1991–2004. They found that noneconomic damage caps reduced premiums by 17.3–25.5 percent depending upon specialty and that each $100,000 more generous cap increased malpractice insurance premiums by 4 percent. These two features of the caps also implied that caps above $750,000 raised malpractice insurance premiums. Other reforms had no effect in retarding premiums.

Tort Reform, Defensive Medicine, and Health Services Utilization

There is less evidence that changes in tort law have affected medical practice patterns. Kessler and McClellan (1996) examined the effects of direct and indirect reforms on the provision of heart disease care over the years 1984–1990. Direct reforms were associated with a 5.3 percent reduction in hospital expenditures for Medicare patients with a new heart attack and a 9.3 percent reduction in expenditures for those with a new case of ischemic heart disease. The effects of the reforms on 1-year mortality and 1-year re-admission were small and statistically insignificant.

There is more evidence with respect to obstetrical care. Using 1984 data, Localio et al. (1993) found that Cesarean-section (C-section) rates were positively associated with malpractice premiums in New York State. Dale and Wojtowycz (1997) used cumulative obstetric malpractice suits by county in New York as a proxy for physician fear of malpractice. Over the 1975–1986 period they found that greater fear was associated with both higher C-section rates (6.6 percentage points) and greater use of electronic fetal monitoring.

Dubay, Kaestner, and Waidmann (2001) examined the effects of malpractice premiums on the prenatal care and infant health over the 1991–1992 period. They found small but statistically significant delays in the onset of prenatal care and reductions in the use of prenatal care in areas with lower malpractice premiums. However, there were no statistically meaningful effects on their measures of infant health. Grant and McInnes (2004) examined the behavior of a panel of Florida obstetricians over the 1992–1995 period. They found that physicians who had medical malpractice claims that led to substantial indemnity payments increased their risk-adjusted cesarean section rates by about one percentage point. Like Dubay and colleagues, they concluded that defensive medicine, in this context, was modest.

In contrast, Studdert et al. (2005) surveyed physicians in six specialties in Pennsylvania in May 2003. Nearly 93 percent of those responding indicated that they practiced defensive medicine by using imaging technology more aggressively, by eliminating procedures prone to complications, and by avoiding patients with complex problems.

Effects of Tort Reform on Health Services Prices

If tort reforms do reduce malpractice insurance premiums and reduce defensive medicine, one would expect that tort reforms should lead to lower costs for physician services. One would certainly expect this to be true in competitive physician markets, but it should also be true, albeit to a lesser extent, in markets where physicians have market power. To our knowledge, only two studies have examined this issue. Thurston (2001) used 1983–1985 data on physician fees and malpractice premiums and concluded that physicians could fully pass on premium increases. In a recent working paper Pauly et al. (2005) examined net income data from single-specialty group practices in 1994, 1998, and 2002. They found no evidence that higher malpractice premiums depressed physician net incomes.

Malpractice Awards and Health Insurance Premiums

Baicker and Chandra (2006) examined the effects of health insurance premiums on employee wages, full-time employment, and a number of other employer-sponsored health insurance issues. As part of the analysis they use the number of state medical malpractice claims settled and the average value of the settlement paid by specialty groups as instruments for health insurance premiums. In this first stage regression, they found that a 1 percent increase the average value of the malpractice settlements per capita in the state increased employer-sponsored health insurance premiums by 1–1.1 percent. In disaggregated regressions, surgical awards raised premiums by 1.4 percent and internal medicine payments increased premiums by 1 percent. The number of awards did not have statistically significant effects.

The chain of logic is that tort reforms reduce the number and size of malpractice claims and reduce the incentive to engage in defensive medicine. The existing empirical evidence supports the view that damage caps, at least, reduce malpractice premiums. There is evidence supporting the view that defensive medicine is reduced at least modestly in cardiac and obstetric care. There is also some evidence that the size of malpractice awards affect health insurance premiums. However, there has been no effort to examine the net effect of damage caps or other forms of tort reforms on premiums. If such an effect is not empirically present, it suggests that tort reforms provide little benefit to consumers.

TORT REFORM DATA

It is difficult to obtain consistent reports of the nature of state medical malpractice tort law and the extent and timing of changes in the law. First, most compendiums of state laws are only concerned about the current law. Second, when laws are enacted by state legislatures, the date of enactment may differ from the date of implementation. Finally, and perhaps most importantly, malpractice reforms are often subjected to court challenges. They may be enjoined by lower courts on the basis of a finding of unconstitutionality and they may ultimately be declared unconstitutional.

In this study we employ a new data set on state-level tort reform. A team of law students supervised by a law professor prepared historical summaries of tort law in each of the states. The team identified statutes and case rulings relating to eleven malpractice reforms enacted since 1975 using Westlaw, LEXIS, and statutory compilations in the law library. All cases and statutes were “Shepardized.” That is, the team used Shepard's Citation Service, now available through LEXIS, to obtain current information as to whether a statute had been amended, repealed, or declared unconstitutional and whether cases have been overruled. Additionally, the status was checked using Westlaw's Findcite and compared with existing compendiums. See Kilgore, Morrisey, and Nelson (2006) for a more detailed discussion. A detailed summary of the laws with the citation of the state code, the efforts at establishing constitutionality, and the legislative language determining the size of the damage cap can be found at LHC (2007). Table 1 lists the states with damage caps and the size of the cap in 2004 dollars.

Table 1.

States with Noneconomic Damage Caps, 2004

| State | 2004 Cap |

|---|---|

| Alaska | $400,000 |

| California | $250,000 |

| Colorado | $300,000 |

| Florida | $500,000 |

| Hawaii | $375,000 |

| Idaho | $250,000 |

| Indiana | $250,000 |

| Kansas | $250,000 |

| Louisiana | $100,000 |

| Maine | $400,000 |

| Maryland | $650,000 |

| Massachusetts | $500,000 |

| Michigan | $354,440 |

| Mississippi* | $500,000 |

| Missouri | $599,088 |

| Montana | $250,000 |

| Nebraska | $200,000 |

| Nevada* | $350,000 |

| New Mexico | $600,000 |

| North Dakota | $500,000 |

| Ohio* | $500,000 |

| South Dakota | $500,000 |

| Texas* | $250,000 |

| Utah | $400,000 |

| Virginia | $1,750,000 |

| West Virginia | $500,000 |

| Wisconsin | $430,840 |

Four states implemented damage caps legislation between 1999 and 2004 and damage caps in one state, Oregon, were struck down as unconstitutional in 2000.

EMPIRICAL SPECIFICATION

The key hypothesis in this analysis is that the enactment or tightening of noneconomic damage caps will reduce private health insurance premiums. We test this hypothesis using a general differences-in-differences approach of the form:

| (1) |

where E is the inflation-adjusted weighted average annual health insurance premium paid by employer f, in state s, in year t on behalf of his or her employee. L is the vector of measures of damage caps by state and year. X is a vector of time varying firm and coverage characteristics. θ and τ are state and year fixed effects, respectively, and ɛ is an error term. Malpractice damage cap laws are defined at the state level and our unit of observation is the firm-level health insurance premium. Robust standard errors are computed in the context of state specific clustering.

Damage caps are measured in two ways. First, we include a dichotomous variable for the presence of a cap and the inflation-adjusted value of the cap. Second, we include a series of four dichotomous variables capturing the size of the inflation-adjusted cap. Like the employer premiums, all values of damage caps are converted to 2004 values using the Consumer Price Index, all items.

The X vector includes measures of the types of plans offered, their share of enrollment, the size of copays and deductibles, the use of self-insured plans, the presence of retiree coverage, total employment, and whether the firm is exclusively local. This specification generally follows the existing empirical literature using employer-specific premium data ( Jensen and Morrisey 1990; Feldman, Dowd, and Gifford 1993; Wholey, Feldman, and Christianson 1995; Morrisey, Jensen, and Gabel 2003).

In our general model we estimate an equation for single coverage. As sensitivity checks we re-estimate and report the model using 3- and 5-year lag values of the damage caps to account for possible lags between the time a cap is imposed or changed and when effects on premiums appear. As further sensitivity cheeks, in specifications not reported, we estimated the model with fixed effects for firm as well as year and state. We included a vector of other tort reforms as used in Kilgore, Morrisey, and Nelson (2006). We also estimated the model using natural logarithms of premiums and for family premiums instead of single coverage premiums. In addition to weighted average premiums, we estimated separate equations for conventional, HMO, PPO, and point-of-service single coverage premiums. This was done to allow more detailed controls for the coverage offered by the firm in each plan type. Finally, because of concerns over the location of “firms” in multi-establishment organizations, we re-estimated the models using only local firms. None of these efforts altered the basic findings.

PREMIUM DATA

We used premium data for the 1999–2004 period from the Health Research and Education Trust/Kaiser Family Foundation Survey of Employer Benefits. The surveys are representative of private sector firms and local/state governments with 200 or more employees and have a response rate of approximately 50 percent. Telephone interviews were conducted by National Research Inc., with the benefits manager or most knowledgeable individual in each firm. Approximately 1,766 organizations responded each year. See Morrisey, Jensen, and Gabel (2003) for details.

The surveys contained information on firm and plan characteristics. Of particular interest, the surveys asked the number of workers in this location, and the number of workers in each type of health insurance plan. It asked the premium charged for COBRA coverage for the largest of each plan type (conventional, HMO, PPO, and POS) offered. This premium definition is useful because it provides a common benchmark by which self-insured and other employer plans can specify the relevant premiums. The average single premium was computed as the sum of the proportion of covered single workers in each plan type times the premium for that plan type. Table 2 contains the means and standard deviations of the variables used in the analysis.

Table 2.

Means and SD

| Variable | Mean | SD | Minimum | Maximum |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Overall single monthly premium | 260 | 86 | 30 | 1,404 |

| Cap (indicator) | 0.46 | 0.49 | 0 | 1 |

| Cap value ($100,000)* | 4.75 | 3.57 | 1 | 17.5 |

| Cap ≤$250,000 | 0.06 | 0.24 | 0 | 1 |

| $250K< Cap ≤$500K | 0.26 | 0.44 | 0 | 1 |

| $500K< Cap ≤$750K | 0.11 | 0.31 | 0 | 1 |

| Cap >$750,000 | 0.04 | 0.19 | 0 | 1 |

| Total employment | 4,510 | 18,560 | 3 | 800,000 |

| % Low income workers | 20 | 22 | 0 | 100 |

| Low copay HMO | 0.24 | 0.43 | 0.00 | 1.00 |

| Low copay PPO | 0.16 | 0.36 | 0.00 | 1.00 |

| Low copay POS | 0.15 | 0.36 | 0.00 | 1.00 |

| Deductible conventional | 48 | 178 | 0 | 4,360 |

| Deductible in-plan PPO | 164 | 279 | 0 | 5,000 |

| Deductible out-plan PPO | 308 | 435 | 0 | 5,200 |

| Deductible in-plan POS | 28 | 132 | 0 | 3,710 |

| Deductible out-plan POS | 122 | 290 | 0 | 4,000 |

| Coinsurance conventional | 0.14 | 0.34 | 0.00 | 1.00 |

| Coinsurance HMO | 0.01 | 0.11 | 0.00 | 1.00 |

| Coinsurance PPO | 0.26 | 0.44 | 0.00 | 1.00 |

| Coinsurance POS | 0.05 | 0.23 | 0.00 | 1.00 |

| Retiree coverage | 0.36 | 0.48 | 0.00 | 1.00 |

| Self-insured—conventional | 0.08 | 0.28 | 0.00 | 1.00 |

| Self-insured—HMO | 0.09 | 0.29 | 0.00 | 1.00 |

| Self-insured—PPO | 0.36 | 0.48 | 0.00 | 1.00 |

| Self-insured—POS | 0.11 | 0.31 | 0.00 | 1.00 |

| % Enrolled HMO | 0.23 | 0.35 | 0.00 | 1.00 |

| % Enrolled PPO | 0.49 | 0.45 | 0.00 | 1.00 |

| % Enrolled POS | 0.20 | 0.36 | 0.00 | 1.00 |

| # Conventionals offered | 0.25 | 2.21 | 0.00 | 136.00 |

| # HMOs offered | 2.00 | 9.37 | 0.00 | 400.00 |

| # PPOs offered | 1.00 | 2.96 | 0.00 | 100.00 |

| # POSs offered | 0.66 | 3.90 | 0.00 | 127.00 |

| Exclusively local firm | 0.57 | 0.50 | 0.00 | 1.00 |

Cap value is conditional on having a cap in place.

FINDINGS

Table 3 reports regression results for fixed effects, weighted average single coverage premiums. The first column reports the specification in which the presence of a damage cap and the size of that inflation adjusted cap, if present, are tallied contemporaneously with the employer-sponsored insurance premium. In the second column the damage cap variables are measured as they existed 3 years before the premium data and in the third column the damage cap values are included as they were five years before the premium data. If it takes time for a damage cap or a more restrictive cap imposed by the legislature to affect malpractice premiums and the practice of defensive medicine and to be translated into lower physician fees and/or lower utilization experience, these specifications should accommodate those lags. The final column uses an alternative specification of the damage caps in which the size of the inflation-adjusted cap, if present, is categorized into one of four ranges.

Table 3.

Regression Results for Single Coverage Monthly Total Premium

| Same-Year Cap | Lag | Ranges of Caps | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 3-Year | 5-Year | |||

| Cap indicator | −6.74 | 7.46 | −3.00 | — |

| (11.29) | (7.35) | (7.57) | ||

| Cap amount | 0.79 | 0.00 | 0.00 | — |

| (1.76) | (0.00) | (0.00) | ||

| Cap ≤$250,000 | — | — | — | −2.95 |

| (6.80) | ||||

| $250K< Cap ≤$500K | — | — | — | −8.07 |

| (6.46) | ||||

| $500K< Cap ≤$750 | — | — | — | 3.12 |

| (4.17) | ||||

| Cap >$750,000 | — | — | — | −27.82*** |

| (5.49) | ||||

| Total employment (in 1,000s) | −0.11*** | −0.11*** | −0.11*** | −0.11*** |

| (0.05) | (0.05) | (0.05) | (0.04) | |

| % Low income workers | −0.18*** | −0.18*** | −0.18*** | −0.18*** |

| (0.06) | (0.06) | (0.06) | (0.06) | |

| Low copay HMO | 4.37 | 4.36 | 4.41 | 3.87 |

| (2.87) | (2.88) | (2.88) | (2.89) | |

| Low copay PPO | 5.09*** | 5.10*** | 5.03*** | 4.98*** |

| (2.26) | (2.25) | (2.25) | (2.23) | |

| Low copay POS | 2.34 | 2.36 | 2.35 | 2.25 |

| (1.90) | (1.90) | (1.90) | (1.89) | |

| Deductible conventional | −0.01* | −0.01* | −0.01* | −0.01* |

| (0.01) | (0.01) | (0.01) | (0.01) | |

| Deductible in-plan PPO | 0.01* | 0.01* | 0.01* | 0.01* |

| (0.00) | (0.00) | (0.00) | (0.00) | |

| Deductible out-plan PPO | −0.01*** | −0.01*** | −0.01*** | −0.01*** |

| (0.00) | (0.00) | (0.00) | (0.00) | |

| Deductible in-plan POS | −0.01 | −0.01 | −0.01 | −0.01 |

| (0.01) | (0.01) | (0.01) | (0.01) | |

| Deductible out-plan POS | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 |

| (0.00) | (0.00) | (0.00) | (0.00) | |

| Coinsurance conventional | −5.19 | −5.21 | −5.30 | −5.30 |

| (5.82) | (5.75) | (5.81) | (5.81) | |

| Coinsurance HMO | −2.17 | −2.11 | −2.31 | −2.19 |

| (6.50) | (6.47) | (6.56) | (6.51) | |

| Coinsurance PPO | −2.65 | −2.66 | −2.56 | −2.79 |

| (2.03) | (2.04) | (2.00) | (2.02) | |

| Coinsurance POS | 3.76 | 3.75 | 3.68 | 4.00 |

| (2.95) | (2.96) | (2.97) | (2.97) | |

| Retiree coverage | 12.56*** | 12.58*** | 12.62*** | 12.90*** |

| (2.55) | (2.56) | (2.56) | (2.57) | |

| Self-insured—conventional | −4.55 | −4.53 | −4.51 | −4.50 |

| (6.95) | (6.91) | (6.91) | (6.94) | |

| Self-insured—HMO | 9.65*** | 9.70*** | 9.82*** | 9.87*** |

| (4.14) | (4.14) | (4.13) | (4.10) | |

| Self-insured—PPO | −2.45 | −2.48 | −2.53 | −2.75 |

| (2.97) | (2.97) | (2.98) | (2.96) | |

| Self-insured—POS | 5.58*** | 5.58*** | 5.66*** | 5.49*** |

| (2.43) | (2.44) | (2.44) | (2.43) | |

| % Enrolled HMO | −62.54*** | −62.55*** | −62.64*** | −62.52*** |

| (9.77) | (9.78) | (9.77) | (9.76) | |

| % Enrolled PPO | −22.58*** | −22.57*** | −22.57*** | −22.30*** |

| (8.23) | (8.20) | (8.21) | (8.22) | |

| % Enrolled POS | −46.09*** | −46.14*** | −46.23*** | −46.39*** |

| (9.49) | (9.47) | (9.48) | (9.45) | |

| # Conventionals offered | −0.37* | −0.37* | −0.37* | −0.38* |

| (0.21) | (0.21) | (0.21) | (0.21) | |

| # HMOs offered | −0.09 | −0.09 | −0.09 | −0.07 |

| (0.08) | (0.08) | (0.08) | (0.07) | |

| # PPOs offered | −0.04 | −0.04 | −0.04 | −0.01 |

| (0.28) | (0.28) | (0.28) | (0.27) | |

| # POSs offered | −0.15 | −0.15 | −0.16 | −0.15 |

| (0.12) | (0.12) | (0.12) | (0.12) | |

| Exclusively local firm | 13.47*** | 13.48*** | 13.46*** | 13.26*** |

| (2.16) | (2.17) | (2.17) | (2.16) | |

| Year 2000 | 18.54*** | 18.27*** | 18.44*** | 18.7*** |

| (3.00) | (2.96) | (2.92) | (2.93) | |

| Year 2001 | 29.17*** | 29.18*** | 29.13*** | 29.18*** |

| (2.48) | (2.41) | (2.47) | (2.49) | |

| Year 2002 | 57.18*** | 57.33*** | 57.49*** | 57.08*** |

| (2.60) | (2.47) | (2.59) | (2.53) | |

| Year 2003 | 85.15*** | 85.33*** | 84.88*** | 84.55*** |

| (3.12) | (3.16) | (3.08) | (3.06) | |

| Year 2004 | 110.06*** | 110.06*** | 109.65*** | 109.84*** |

| (3.21) | (3.22) | (3.16) | (3.44) | |

| Constant | 240.50*** | 236.15*** | 243.27*** | 242.38*** |

| (9.12) | (8.55) | (10.63) | (9.13) | |

| R2 | 0.268 | 0.268 | 0.268 | 0.267 |

indicate statistical significance at the 90 percent confidence levels, two-tailed tests.

indicate statistical significance at the 95 percent confidence levels, two-tailed tests.

indicate statistical significance at the 99 percent confidence levels, two-tailed tests.

All equations include state fixed effects. Standard errors are robust to state and year clusters.

It is clear from a consideration of the alternative damage cap models that caps on noneconomic damages did not translate into lower health insurance premiums for employers. In the contemporaneous and 5-year lag models the presence of a cap had small and negative coefficients; the coefficient was positive in the 3-year lag. However, in none of these models did the point estimates approach statistical significance at the conventional levels. Moreover, there did not appear to be a lag mechanism at play in as much as the largest negative coefficient was obtained in the contemporaneous damage cap specification not in the lag models. The regression reported in column 4 effectively yielded the same result, although the coefficient on the least binding cap is statistically significant.

One might legitimately ask if there was enough variability in the enactment of damage caps to provide enough statistical power to meaningfully examine the issue. In fact four states enacted damage caps during the 1999–2004 and one additional state removed damage caps. However, the inflation-adjusted damage cap changes in virtually every state that enacted a cap. Most of the damage caps are legislatively specified as dollar specific limits, e.g., $500,000. Thus, the limit is effectively made more constraining every year in which inflation is present. Only four states, Maryland, Michigan, Missouri, and Wisconsin, have legislative provisions that adjust the cap for some measure of inflation. Two additional states, Virginia and Maine, explicitly adjusted their cap during the 1999–2004 period. Looked at from another vantage point, two states had real cap amounts in excess of $750,000 and, due to inflation, one state had a cap that was reduced from above $750,000 to <$750,000. In all, these states contained 336 firm-year observations. For the category of $500,000–750,000, 12 states were represented with four of these changing categories over time and comprising 1,426 firm-year observations. Thus, we have substantial variation across states and over time with respect to at least the size of the damage cap. Moreover, based upon the contemporaneous specification (in column 1) the robust standard error for the presence of a damage cap was $11.51, so the model was capable of detecting a $23.00 difference in monthly premiums at the .05 level of significance. (At the average premium, this is approximately an 8.8 percent change.) Similarly, the model was sufficient to detect a $3.70 change in monthly premiums for a $100,000 change in the value of a cap.

The results were also robust to a large number of alternative specifications including the inclusion of other tort reforms, using family coverage, using a logarithmic specification, running the models separately by type of insurance plan (to better account for the nature of coverage), and adding fixed effects for firms. The only specifications that resulted in large statistically significant coefficients on the damage cap measures were specifications that excluded year or state fixed effects. In these cases the coefficients had large point estimates but of the wrong sign, suggesting that either the damage caps inexplicably led to higher premiums or that there was significant endogeneity in the models.

Finally, we briefly turn to the other terms in the model. It is clear from the regressions in Table 3 that many of the characteristics of the firm and the firm's coverage were statistically significant. Because this is a reduced-form model it is not possible to sign the expected effects. A higher copay measure, for example, may reflect both a utilization effect and a plan choice effect. However, the results are consistent with earlier cross-sectional research that similarly demonstrates that employer premiums are related to coverage, self-insured status, and the mix of coverage across employees.

DISCUSSION

The argument for capping malpractice damage awards is that they reduce medical malpractice premiums and cut defensive medicine. Ultimately, these efforts are expected to reduce health care costs.

There is an established body of empirical research that indicates that limitations on the size of noneconomic damages have constrained the growth of medical malpractice premiums. The rigorous empirical evidence with respect to defensive medicine is more modest but suggests some cost reductions in cardiac and obstetric care. More general surveys of physicians suggest a widespread practice of defensive medicine.

Why then do we not find that damage caps reduced health insurance premiums paid by employers? There are two explanations. First, medical malpractice premiums themselves are a very small component of health care costs. Danzon (2000) reports that such premiums constitute about one percent of health care costs. Baicker and Chandra (2006) found that a one percent increase in malpractice awards per capita increased malpractice premiums by only one percent. Thus, even if damage caps were dramatically effective, say reducing malpractice premiums by 50 percent (which no study has concluded), they would at best reduce health insurance costs by no more than one-half of one percent. Less-effective reforms would have an even smaller impact. From this perspective, our results are no surprise.

The second explanation relates to the practice of defensive medicine. Proponents of tort reform have argued that high malpractice premiums and fear of lawsuits have led physicians to perform extra tests, to pass complex cases on to specialists, and to otherwise increase the cost of care and/or the volume of care. The implication of this is that the costs of defensive medicine are large and likely dwarf the malpractice premium savings and yield marked reductions in health insurance premiums. We do not find any such result.

One interpretation may be that there is little actual defensive medicine actually practiced. The few empirical studies that control for other factors find only small to modest effects. If so, tort reforms will have little impact on health insurance premiums.

Another interpretation is that defensive medicine may be little affected by tort reforms. As Danzon (2000) has observed, the time, anxiety and embarrassment associated with malpractice claims may outweigh premium costs. If these are the real drivers of clinical practice patterns, then tort reforms that affect malpractice premiums may have little effect of physician behavior. In such a case, we would be unable to find an effect on health insurance premiums.

One stark policy implication immerges from this study. Tort reforms have not led to health care cost savings for consumers. As a consequence, state and federal legislatures need to reassess their efforts at tort reform and again ask whether limitations on patients' rights to redress in the face of potential negligence provide anything of benefit to consumers themselves. The results of this study suggest that there are no insurance premium savings that accrue to consumers. Are there other benefits to consumers? If these cannot be identified, it is difficult to see a justification for the loss of legal rights.

Acknowledgments

Joint Acknowledgement/Disclosure Statement: This project was funded by grant number 050298 from the Robert Wood Johnson Foundation under its Changes in Health Care Financing and Organization initiative. An earlier version of the paper was presented at the International Health Economics Association Fifth World Congress and seminars at the University of Alabama at Birmingham, University of Iowa, Army-Baylor Graduate Program in Health and Business, and the American Enterprise Institute.

Disclosures: None.

Supplementary material

The following supplementary material for this article is available online:

Author Matrix.

This material is available as part of the online article from: http://www.blackwell-synergy.com/doi/abs/10.1111/j.1475-6773.2008.00869.x (this link will take you to the article abstract).

Please note: Blackwell Publishing is not responsible for the content or functionality of any supplementary materials supplied by the authors. Any queries (other than missing material) should be directed to the corresponding author for the article.

REFERENCES

- AMA. Nation's Leading Physician Groups Join Together to Announce Principles for Reforming the U.S. Health Care System. 2007 [accessed on June 2, 2007]. Available at http://www.ama-assn.org/ama/pub/category/17206.html.

- Baicker K, Chandra A. The Labor Market Effects of Rising Health Insurance Premiums. Journal of Labor Economics. 2006;24(3):609–43. [Google Scholar]

- Blackmon G, Zeckhauser R. The Effect of State Tort Reform Legislation on Liability Insurance Losses and Premiums. 1990. Working paper, Harvard University, Kennedy School of Government.

- Dale T A, Wojtowycz M A. Malpractice, Defensive Medicine, and Obstetric Behavior. Medical Care. 1997;35(2):172–91. doi: 10.1097/00005650-199702000-00007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Danzon P M. Liability for Medical Malpractice. In: Culyer A J, Newhouse J P, editors. Handbook of Health Economics. Vol 1B. Amsterdam: Elsevier; 2000. pp. 1339–404. [Google Scholar]

- Danzon P M, Epstein A J, Johnson S. The ‘Crisis’ in Medical Malpractice Insurance. 2004 [accessed on May 12, 2008]. Available at http://fic.wharton.upenn.edu/fic/papers/04/Danzon%20%20Paper.pdf.

- Dubay L, Kaestner R, Waidmann T. Medical Malpractice Liability and Its Effect on Prenatal Care Utilization and Infant Health. Journal of Health Economics. 2001;20:591–611. doi: 10.1016/s0167-6296(01)00082-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Feldman R, Dowd B, Gifford G. The Effect of HMOs on Premiums in Employer-Based Health Plans. Health Services Research. 1993;27(6):779–811. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grant D, McInnes M M. Malpractice Experience and the Incidence of Cesarean Delivery: A Physician-Level Longitudinal Analysis. Inquiry. 2004;41(2):170–88. doi: 10.5034/inquiryjrnl_41.2.170. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jensen G A, Morrisey M A. Group Health Insurance: An Hedonic Approach. Review of Economics and Statistics. 1990;72(1):38–44. [Google Scholar]

- Kessler D, McClellan M. Do Doctors Practice Defensive Medicine? Quarterly Journal of Economics. 1996;111:353–90. [Google Scholar]

- Kessler D P, McClellan M. The Effects of Malpractice Pressure and Liability Reforms on Physicians' Perceptions of Medical Care. Law and Contemporary Problems. 1997;60:81–106. [Google Scholar]

- Kilgore M L, Morrisey M A, Nelson L J. Tort Law and Medical Malpractice Insurance Premiums. Inquiry. 2006;43(3):255–70. doi: 10.5034/inquiryjrnl_43.3.255. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lister Hill Center for Health Policy. Compendium of State Damages Caps Laws 1975-Present. 2007 [accessed on May 12, 2008]. Available at http://www.healthpolicy.uab.edu/malpractice.

- Localio A R, Lawthers A G, Bergtson J M, Hebert L E, Weaver S L, Brennan T A, Landis J R. Relationship between Malpractice Claims and Cesarean Delivery. Journal of the American Medical Association. 1993;269(3):366. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Madigan E. Medical Malpractice Reform High on States Agenda, Stateline.org. 2003 [accessed on June 16, 2005]. Available at http://www.stateline.org/live/viewpage.action?sitenodeid=136&languageid=1&contentid=15331.

- Medical Benefits. Survey of Businesses Served by Professional Employer Organizations. Medical Benefits. 2007;24(3):10–1. [Google Scholar]

- Medical Liability Monitor. Rate Survey Issues 1991–2004. 2005 [accessed on June 16, 2005]. Available at http://www.medicalliabilitymonitor.com.

- Mello M M. Medical Malpractice: Impact of the Crisis and Effect of State Tort Reforms. Princeton, NJ: Robert Wood Johnson Foundation; 2006. Research Synthesis #10. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morrisey M A, Jensen G A, Gabel J. Managed Care and Employer Premiums. International Journal of Health Care Finance and Economics. 2003;3(2):95–116. doi: 10.1023/a:1023317214453. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nelson L J, Kilgore M L, Morrisey M A. Damage Caps in Medical Malpractice Cases. Milbank Quarterly. 2007;85(2):259–86. doi: 10.1111/j.1468-0009.2007.00486.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pauly M V, Thompson C, Abbot T, Margolis J, Sage W M. Who Pays? The Incidence of High Malpractice Premiums. 2005. Working Paper, University of Pennsylvania, Wharton School of Business.

- Posner J R. Trends in Medical Malpractice Insurance 1970–1985. Law and Contemporary Problems. 1986;49:37–56. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sloan F A, Bovbjerg R R, Githerns P B. Insuring Medical Malpractice. New York: Oxford University Press; 1991. [Google Scholar]

- Studdert D M, Mello M M, Sage W M, DesRoches C M, Peugh J, Zapert K, Brennan T A. Defensive Medicine among High-Risk Specialist Physicians in a Volatile Malpractice Environment. Journal of the American Medical Association. 2005;293(21):2609–17. doi: 10.1001/jama.293.21.2609. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thorpe K E. The Medical Malpractice ‘Crisis’: Recent Trends and the Impact of State Tort Reforms. Health Affairs–Web Exclusive. 2004;W4:20–30. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.w4.20. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thurston N K. Physician Market Power-Evidence from The Allocation of Malpractice Premiums. Economic Inquiry. 2001;39:487–98. [Google Scholar]

- Viscusi W K, Born P H. Medical Malpractice Insurance in the Wake of Liability Reform. Journal of Legal Studies. 1995;24:463–90. [Google Scholar]

- Viscusi W K, Born P H. Damages Caps, Insurability, and the Performance of Medical Malpractice Insurance. 2004. Working Paper, Harvard University, John M. Olin Center for Law, Economics and Business.

- Viscusi W K, Zeckhauser R J, Born P, Blackmon G. The Effects of 1980s Tort Reform Legislation on General Liability and Medical Malpractice Insurance. Journal of Risk and Uncertainty. 1993;6:165–86. [Google Scholar]

- Wholey D, Feldman R, Christianson J B. The Effect of Market Structure on HMO Premiums. Journal of Health Economics. 1995;14(1):81–105. doi: 10.1016/0167-6296(94)00039-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Young J. Physician Lobby Shifts Strategy on Medical-Liability Reform. The Hill. 2007 [accessed on June 2, 2007]. Available at http://www.thehill.com/thehill/export/TheHill/News/Frontpage/020107/medical.html.

- Zuckerman S, Bovbjerg R R, Sloan R. Effects of Tort Reforms and Other Factors on Medical Malpractice Insurance Premiums. Inquiry. 1990;27:167–82. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Author Matrix.