Abstract

The application of high-resolution X-ray spectroscopy methods to study the photosynthetic water oxidizing complex, which contains a unique hetero-nuclear catalytic Mn4Ca cluster, is described. Issues of X-ray damage, especially at the metal sites in the Mn4Ca cluster, are discussed. The structure of the Mn4Ca catalyst at high resolution, which has so far eluded attempts of determination by X-ray diffraction, X-ray absorption fine structure (EXAFS) and other spectroscopic techniques, has been addressed using polarized EXAFS techniques applied to oriented photosystem II (PSII) membrane preparations and PSII single crystals. A review of how the resolution of traditional EXAFS techniques can be improved, using methods such as range-extended EXAFS, is presented, and the changes that occur in the structure of the cluster as it advances through the catalytic cycle are described. X-ray absorption and emission techniques (XANES and Kβ emission) have been used earlier to determine the oxidation states of the Mn4Ca cluster, and in this report we review the use of X-ray resonant Raman spectroscopy to understand the electronic structure of the Mn4Ca cluster as it cycles through the intermediate S-states.

Keywords: X-ray absorption fine structure, manganese, oxygen-evolving complex, polarized X-ray absorption fine structure, photosystem II, photosystem II single crystals

1. Introduction

Life on earth relies on oxygen, and only owing to the constant regeneration of oxygen through photosynthetic water oxidation by green plants, cyanobacteria and algae is it abundant in the atmosphere. The structure of the catalytic Mn4Ca complex, which oxidizes H2O to O2 and is part of a multi-protein membrane system known as photosystem II (PSII), has been the subject of intense study ever since Mn was identified as an essential element for oxygenic photosynthesis (Wydrzynski & Satoh 2005). Water oxidation in PSII is a stepwise process wherein each of four sequential photons absorbed by the reaction centre powers the advance of the oxygen-evolving complex (OEC) through the S-state intermediates S0 through S4 (Kok et al. 1970). Upon reaching the S4 state, the complex releases O2 and returns to S0. The critical questions related to this process are the structural and electronic state changes in the Mn4Ca complex as the OEC proceeds through the S-state cycle. The recent results from our laboratory that address these questions, using polarized X-ray absorption fine structure (EXAFS) of single crystals of PSII (Yano et al. 2005a; Yano et al. 2006), range-extended EXAFS (Yano et al. 2005b; Pushkar et al. 2007) and X-ray Raman spectroscopy or resonant inelastic X-ray spectroscopy (RIXS; Glatzel et al. 2004; Glatzel et al. 2005), were presented at the Royal Society Discussion Meeting on ‘Revealing how nature uses sunlight to split water’ and are reviewed here.

2. Structure of the Mn4Ca cluster in photosynthesis

(a) Single crystal X-ray spectroscopy

A key to understanding the mechanism of water oxidation by the OEC in PSII is the determination of the structure of the Mn4Ca cluster, which has eluded both Mn X-ray absorption fine structure (EXAFS; Penner-Hahn 1998; Dau et al. 2001; Yachandra 2005; Sauer et al. 2008) and X-ray diffraction (XRD) studies (Zouni et al. 2001; Kamiya & Shen 2003; Ferreira et al. 2004; Loll et al. 2005) until now. Availability of PSII single crystals and the X-ray crystallographic studies of PSII have opened up the possibility of using spectroscopic studies of single crystals to obtain a detailed high-resolution structure of the catalytic site of water oxidation in PSII.

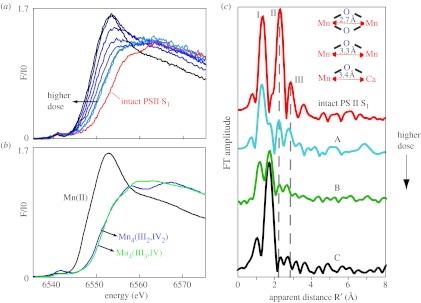

(i) Damage by X-rays: a case study for metalloprotein crystallography

In order to determine a safe level of X-ray dose for our single crystal X-ray spectroscopy studies, we conducted a comprehensive survey of the effects of radiation dose, energy of the X-rays and temperature on the structure of the Mn4Ca cluster in single crystals and solutions of PSII. These studies (Yano et al. 2005a) have revealed that the conditions used for structure determination by XRD methods are damaging to the metal site structure as monitored by X-ray absorption near edge structure (XANES) and EXAFS spectroscopy, for both cyanobacteria and spinach at room and lower temperatures (Yano et al. 2005a; Grabolle et al. 2006). With the advent of third generation synchrotron sources, the intensity of X-rays available for crystallography has increased considerably, and X-ray damage to biomolecules has been a continuing concern. This is a well-recognized problem, and various steps have been taken to minimize such damage (Garman 2003). In most crystallography studies, it is the loss of diffractivity as evidenced by loss of resolution that is used as a measure of X-ray damage (Henderson 1990). However, as shown in our study (Yano et al. 2005a), this method is not sensitive to localized damage as is prevalent in redox-active metal-containing proteins. We used in situ XANES and EXAFS to show that for the Mn4Ca cluster in PSII the damage to the metal site precedes the loss of diffractivity by more than an order of magnitude of X-ray dose. This case study demonstrates that such in situ evaluation of the structural intactness of the active site(s) by spectroscopic techniques can be critical to validate structures derived from crystallography. Since structure–function correlations are routinely made using the structures determined by X-ray crystallography, it is important to know that the metal site structures are indeed intact. This is particularly important for radiation-sensitive metalloproteins.

Although X-ray crystallography studies of PSII have added valuable information to our knowledge about the location of the Mn4Ca cluster, at present there are serious discrepancies among the structural models for the Mn4Ca complex derived from these studies, and inconsistencies with spectroscopic data. This disagreement is probably a consequence of both X-ray-induced damage to the catalytic metal site and differences in the interpretation of the electron density at the presently available resolution (3.0–3.8 Å; Zouni et al. 2001; Kamiya & Shen 2003; Ferreira et al. 2004; Loll et al. 2005).

The Mn XANES data from PSII single crystals show that, following X-ray doses characteristic of the XRD measurements, Mn are reduced to Mn(II) from Mn4(III2,IV2) present in the S1 state (figure 1, left). Moreover, the EXAFS spectrum changes significantly, from one that is characteristic of a multinuclear oxo-bridged Mn4Ca complex to one that is typical of mononuclear hexa-coordinated Mn(II) in solution (figure 1, right; Yano et al. 2005a). These X-ray spectroscopy results present clear evidence that there are no specific metal bridging or metal–metal interactions, as shown by the disappearance of the Fourier peaks that are characteristic of Mn-bridging oxo, and Mn–Mn/Mn–Ca interactions with di-μ-oxo or mono-μ-oxo bridges, and by the appearance of Mn–O distances characteristic of Mn(II)–O ligand bond lengths. The density seen in the XRD results is in all probability from the Mn(II)-hexa-coordinated ions that are distributed in the binding pocket, presumably bound to carboxylate ligands and free water, leading to a distribution of metal-binding sites and the resultant unresolved electron density. The metal ions have not necessarily moved away from the site, it is just that they are all bound in a distribution of sites, without the presence of di- or mono-μ-oxo-bridged Mn–Mn or Mn–Ca units.

Figure 1.

Mn XANES and EXAFS of single crystals of PSII from Thermosynechococcus elongatus as a function of X-ray dose. (a) PSII single crystal: as the X-ray dose increases, Mn in PSII normally present as Mn4(III2, IV2) is reduced to Mn(II) as seen by the changes in XANES spectra. (b) Mn models: the Mn XANES from Mn complexes in formal oxidation states II, III and IV. (c) The changes in the EXAFS spectra show that the three Fourier peaks characteristic of Mn-bridging-oxo, Mn-terminal and Mn–Mn/Ca interactions (dashed vertical line) are replaced by one Fourier peak characteristic of a Mn(II) environment. The FT marked C is from a sample given approximately the average dose in the XRD studies. The FT on top from an intact PSII is characteristic of samples used in the X-ray spectroscopy experiment.

These studies reveal that the conditions used for structure determination by X-ray crystallography cause serious damage, specifically to the metal site structure, and they provide quantitative details. The results show furthermore that the damage to the active metal site occurs at a much lower X-ray dose than that causing the loss of diffractive power of the crystals as established by X-ray crystallography. The damage is significantly higher at wavelengths used for anomalous diffraction measurements and is much lower at liquid He temperatures (10 K) compared with 100 K, where the crystallography experiments were conducted. For future X-ray crystallography work on the Mn4Ca complex, it will therefore be imperative to develop protocols that mitigate the X-ray-induced damage. More generally, these data show that in redox-active metalloproteins careful evaluations of the structural intactness of the active site(s) are required before structure–function correlations can be made on the basis of high-resolution X-ray crystal structures.

(ii) Structure of the Mn4Ca complex from polarized EXAFS of PSII crystals

PSII membranes can be oriented on a substrate such that the membrane planes are roughly parallel to the substrate surface. This imparts a one-dimensional order to these samples; while the z axis for each membrane (collinear with the membrane normal) is roughly parallel to the substrate normal, the x and y axes remain disordered (Rutherford 1985). Exploiting the plane-polarized nature of synchrotron radiation, spectra can be collected at different angles between the substrate normal and the X-ray e-vector. The dichroism of the absorber–backscatterer pair present in the oriented samples is reflected in, and can be extracted from, the resulting X-ray absorption spectra (George et al. 1989; Mukerji et al. 1994; Dau et al. 1995; Dau et al. 2001; Cinco et al. 2004). The EXAFS of the oriented PSII samples exhibits distinct dichroism, from which we have deduced the relative orientations of several interatomic vector directions relative to the membrane normal and derived a topological representation of the metal sites in the OEC. However, because the samples are ordered in only one dimension, the dichroism information is available only in the form of an angle with respect to the membrane normal. For EXAFS measurements, this means that the absorber–backscatterer vectors can lie anywhere on a cone defined by the angle the vector forms with the membrane normal.

Further refinement can be performed if samples with three-dimensional order, i.e. single crystals, are examined instead of oriented membranes (Scott et al. 1982; Flank et al. 1986). This is possible because the EXAFS amplitude is proportional to approximately cos2θ, where θ is the angle between the X-ray E vector and the absorber–backscatterer vector. These studies have been able to significantly expand the X-ray absorption spectroscopic information available for these systems over what is gleaned from studies of isotropic samples. We have developed the methodology for collecting single crystal X-ray absorption spectroscopy (XAS) data from PSII. XAS spectra were measured at 10 K using a liquid He cryostat or cryostream, and an imaging plate detector placed behind the sample was used for in situ collection of diffraction data and determination of the crystal orientation.

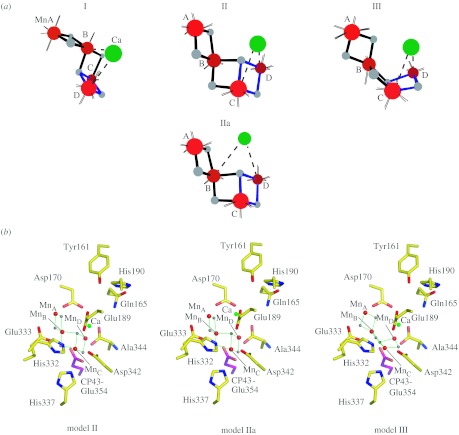

We have reported the polarized EXAFS spectra of oriented PSII single crystals, which result in a set of four similar high-resolution structures for the Mn4Ca cluster (figure 2a; Yano et al. 2006), which were derived from simulations of single crystal polarized spectra based on the experimentally observed dichroism. These structural models are dependent only on the spectroscopic data, and are independent of the electron density from XRD studies. The structure of the Mn4Ca cluster from the polarized EXAFS study of PSII single crystals is unlike either the 3.0 (Loll et al. 2005) or 3.5 Å (Ferreira et al. 2004) resolution X-ray structures, and other previously proposed models. The structure of the Mn4Ca cluster favoured in our study contains structural features that are unique and are likely to be important in facilitating water-oxidation chemistry.

Figure 2.

(a) The structural models determined from the polarized EXAFS spectra of oriented PSII single crystals from T. elongatus. The distance between MnA–MnB, MnB–MnC is approximately 2.7 Å, MnC–MnD is approximately 2.8 Å, and MnB–MnD is approximately 3.2 Å. There are at least two Ca–Mn distances of approximately 3.4 Å (Yano et al. 2006). (b) The structural models II, IIa and III are placed in the ligand environment from the XRD data of Loll et al. at a resolution of 3.0 Å. The centre of mass was translated to the centre of electron density attributed to the Mn4Ca cluster in the XRD structure without any rotation (Loll et al. 2005).

In order to discriminate between symmetry-related structural models that are possible owing to the presence of a non-crystallographic C2 axis, the cluster was placed within PSII taking into account the overall shape of the electron density of the metal site and the putative ligand information from X-ray crystallography, including infrared and electron paramagnetic resonance (EPR) studies. The centre of mass of the structural models was translated to the centre of electron density attributed to the Mn4Ca cluster in the 3.0 Å XRD structure (Loll et al. 2005) and the models were not optimized with respect to the electron density, or rotated with respect to the crystal axes, as that would change the dichroic characteristics. Of the four options shown in figure 2a, it is possible to rule out Model I on the basis of oriented membrane EXAFS data (Cinco et al. 2004; Pushkar et al. 2007). Model II, IIa and III in the putative ligand environment are shown in figure 2b. However, we caution that the ligand positions are tentative because they are likely to be affected by radiation damage, as are the positions of the metals atoms from XRD (Yano et al. 2005a; Grabolle et al. 2006).

The polarized EXAFS study of PSII single crystals demonstrates that the combination of XRD and polarized EXAFS has several advantages for unravelling structures of X-ray damage-prone, redox-active metal sites in proteins. XRD structures at medium resolution are sufficient to determine the overall shape and placement of the metal site within the ligand sphere, and refinement using polarized EXAFS can provide accurate metal–metal/ligand vectors. In addition, we are extending the study to determine the structure of the Mn4Ca cluster in the intermediate S-states of the OEC, which are difficult to study with XRD at high resolution.

(b) Range-extended X-ray absorption spectroscopy

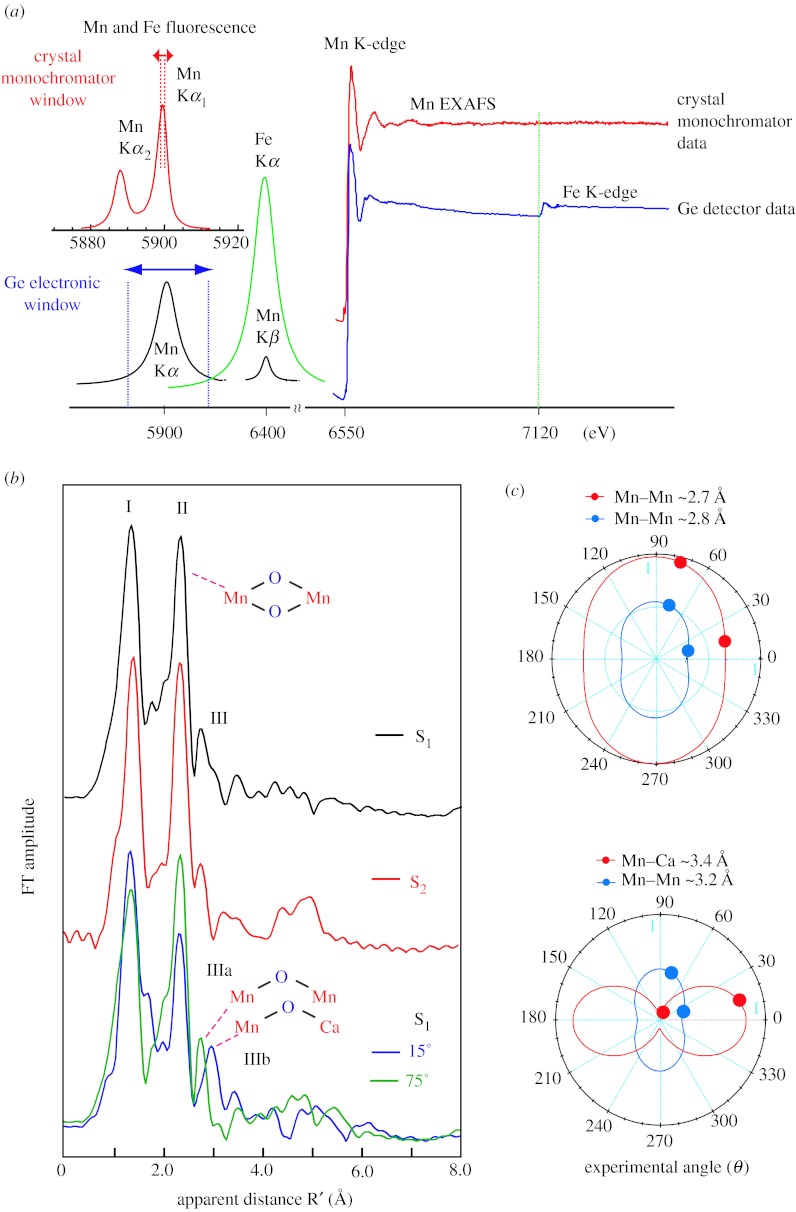

EXAFS spectra of metalloprotein samples are normally collected in X-ray fluorescence yield by electronically windowing the Kα emission (2p to 1s) from the metal atom (Scott 1984; Cramer 1988; Yachandra 1995). The solid state detectors used over the past decade have a resolution of 150–200 eV, full width at half maximum (FWHM), making it impossible to fully discriminate the fluorescence of the absorbing atom (Mn in our case for PSII) from that of the following element (Fe in PSII) in the periodic table. The distances from Mn that can be resolved in a typical EXAFS experiment are given by ΔR=π/2Δk, where k is the energy of the Mn photoelectron. Unfortunately, owing to the presence of Fe in the PSII samples we have been limited to a Δk of approximately 12 Å−1, which places an inherent limit on the resolution of Mn distances to approximately 0.14 Å. We have overcome this limitation by using a high-resolution crystal monochromator (Bergmann & Cramer 1998), which has a resolution of 1 eV to collect EXAFS spectra well beyond the Fe K-edge to k=15 Å−1, thus improving the distance resolution to 0.09 Å (figure 3a). We have recently shown the feasibility of the range-extended EXAFS method and collected data without interference from Fe in the sample (Yano et al. 2005b).

Figure 3.

(a) A schematic of the detection scheme. Mn and Fe Kα1 and Kα2. The multi-crystal monochromator with approximately 1 eV resolution is tuned to the Kα1 peak (red). The fluorescence peaks broadened by the Ge-detector with 150–200 eV resolution are shown below (blue). Right: The PSII Mn K-edge EXAFS spectrum from the S1 state sample obtained with a traditional energy-discriminating Ge-detector (blue) compared with that collected using the high-resolution crystal monochromator (red). Fe present in PSII does not pose a problem with the high-resolution detector (the Fe edge is marked by a green line). (b) Fourier transform (FT) of Mn K-edge EXAFS spectra from isotropic solution and oriented PSII membrane samples in the S1, S2 and oriented S1 state obtained with a high-resolution spectrometer (range-extended EXAFS). Angles indicate orientation of the membrane normal with respect to the X-ray e-field vector. The k range was 3.5–15.2 Å−1. (c) Polar plot of the X-ray absorption linear dichroism of PSII samples in the S1 state. The Napp values (solid circles) for oriented membranes are plotted at their respective detection angles (θ). The best fits of Napp versus θ to the equation in the text are shown for the various Mn–Mn vectors as solid lines that take into account the experimentally determined mosaic spread of Ω=20°.

We can now resolve two short Mn–Mn distances in the S1 and S2 states, while earlier we could discern only one distance of approximately 2.7 Å. We have also collected range-extended polarized EXAFS data using oriented PSII membranes, and it is quite clear that the heterogeneity is more obvious; the Mn–Mn distance is approximately 2.7 or 2.8 Å depending on the angle the X-ray e-vector makes with the membrane normal. Interestingly, for the first time we were able to resolve the Fourier transform (FT) peak at approximately 3.3 Å into one Mn–Mn vector at 3.3 Å and two Mn–Ca vectors at 3.4 Å, which are aligned at different angles to the membrane normal (Pushkar et al. 2007).

In figure 3b FTs of the range-extended EXAFS for PSII in isotropic solution and in oriented membranes in S1 state are compared. Peaks are labelled I, II, III corresponding to the shells of backscatterers from the Mn absorber. Peak I contains Mn–O bridging and terminal interactions, and peak II corresponds to di-μ-oxo-bridged Mn–Mn moieties, peak III has information about mono-μ-oxo-bridged Mn–Mn and Mn–Ca interactions. Increased spectral resolution results in the detection of the orientation dependence of peaks II and III.

Figure 3c shows polar plots of the Napp plotted (solid circles) with respect to detection angle (θ). By fitting the angle dependence of the amplitude (Napp) to equation (2.1),

| (2.1) |

the approximate number of backscatterers (Niso) and the average orientation 〈ϕ〉 for that shell of scatterers can be determined. Analysis of the orientation dependence of the approximately 2.7 Å Mn–Mn vector results in two Mn–Mn interactions at an average angle of 〈ϕ〉=61±5°, with respect to the membrane normal. The approximately 2.8 Å Mn–Mn vector has one Mn–Mn interaction at an angle of 〈ϕ〉=64±10° with respect to the membrane normal. In this way, we independently derived that the three Mn–Mn distances of approximately 2.7 Å and approximately 2.8 Å are present in a 2 : 1 ratio in PSII samples in the S1 state.

The range-extended EXAFS method allowed us to resolve the complex nature of the peak III containing at least two peaks, IIIA and IIIB, having different distances of 3.2 and 3.4 Å. Previous Ca EXAFS studies of native PSII (Cinco et al. 2002), Sr EXAFS of Sr-substituted PSII (Cinco et al. 1998), and Mn EXAFS (Latimer et al. 1995) of Ca-depleted PSII (Latimer et al. 1998) have shown the contribution of both Mn–Mn (approx. 3.2 Å) and Mn–Ca (approx. 3.4 Å) vectors to FT peak III. Peak IIIB can be assigned to the Mn–Ca vector and peak IIIA to the Mn–Mn vector, and moreover, the dichroic behaviour of peak IIIB is strikingly similar to that reported previously for the Mn–Sr vector (Cinco et al. 2004).

We have extended these studies to the S0 and S3 intermediate states of the enzymatic cycle, and the preliminary results show that there is a significant change in the structure of the Mn complex in the S3 state. This result has important implications for choosing between the many mechanisms that have been proposed for the water oxidation reaction. In conjunction with the data from single crystal XAS studies, these studies promise to reveal the changes that occur in the structure of Mn4Ca catalyst as it cycles through the S-states and the mechanism of water oxidation.

3. Electronic structure of the Mn4Ca cluster

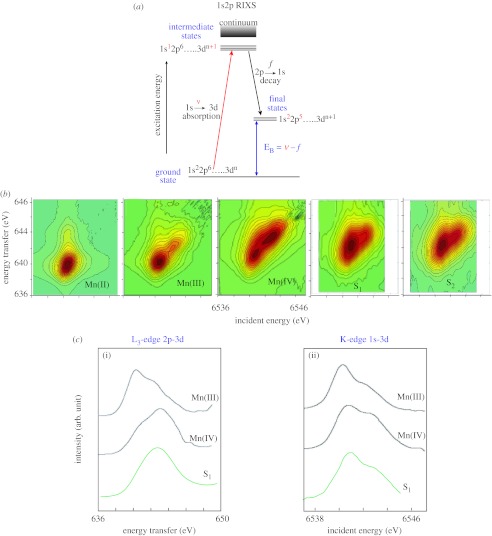

(a) X-ray resonant Raman or resonant inelastic X-ray scattering

A key question for the understanding of photosynthetic water oxidation is whether the four oxidizing equivalents generated by the reaction centre are accumulated on the four Mn ions of the OEC during S-state turnover, or whether a ligand-centred oxidation takes place, especially, before the formation and release of molecular oxygen during the S3 to (S4) to S0 transition (Yano & Yachandra 2007). It is crucial to solve this problem, because the Mn redox states form the basis for any mechanistic proposal. The description of the Mn4Ca cluster in the various S-states in terms of the formal oxidation states is very useful, and Mn K-edge XANES has been the conventional X-ray spectroscopic method for determining the oxidation states. However, it is also important to understand the electronic structure of the Mn cluster in more detail, and we are using the technique of X-ray resonant Raman or resonant inelastic X-ray scattering (RIXS) that has potential for addressing this issue. The RIXS data are collected by scanning the incident energy (1s to 3d/4p absorption followed by 2p-1s emission) to yield two-dimensional plots that can be interpreted along the incident energy axis or the energy transfer axis, which is the difference between the incident and emission energies (figure 4a; Glatzel & Bergmann 2005). This method provides a description of the degree of covalency and d-orbital occupancy of the Mn complex, both parameters that are critical for understanding what makes this cluster function as it advances through the enzymatic cycle.

Figure 4.

(a) The energy level diagram for 1s2p RIXS. Excitation energy ν, corresponding to a 1s to 3d transition, is scanned using a double crystal monochromator; f is the 2p to 1s emission that is scanned using a high-resolution crystal monochromator. The difference ν−f corresponds to an L-edge-like (2p to 3d) transition. (b) Contour plots of the 1s2p3/2 RIXS planes for three molecular complexes MnII(acac)2(H2O)2, MnIII(acac)3, and MnIV(sal)2(bipy) and PSII in the S1- and S2 state. One axis is the excitation energy and the other is the energy transfer axis. The L-edge like spectra are along the energy transfer axis and the 1s to 3d transition is along the incident energy axis. The assignment of Mn(III2,IV2) for the S1 state is confirmed by these spectra. (c(ii)) Integrated spectra along the incident energy axis (K-edge, 1s to 3d) and (c(i)) energy transfer axis (L3 edge, 2p to 3d) of the contour plot shown in figure 4b for MnIII(acac)3 and MnIV(sal)2(bipy) and S1 state of PSII. The spectra show that the Mn oxidation state of S1 is a combination of (III) and (IV).

We have compared the spectral changes in the RIXS spectra between the Mn4Ca cluster in the S-states (Glatzel et al. 2004), Mn oxides (Glatzel et al. 2005) and Mn coordination complexes, and the results indicate clear differences in how the protein environment modulates the Mn atoms, leading to stronger covalency for the electronic configuration in the Mn4Ca cluster compared with that in the oxides or coordination complexes.

The RIXS two-dimensional data are best shown as contour plots (figure 4b). The comparison of Mn(II), Mn(III), Mn(IV) and PSII in the S1 and S2 states shows that both states contain a mixture of oxidation states Mn(III) and Mn(IV). The integrated cross sections along the Raman or energy transfer axis are the L3-like edge (2p to 3d; figure 4c, (i)). The integrated cross sections along the incident energy are the K-edge (1s to 3d) transition (figure 4c, (ii)). It is clear from figure 4 that Mn in the S1 state is in oxidation states III and IV, thus providing confirmation for the (III2, IV2) assignment for the S1 state.

The first moment of the spectrum integrated along the incident energy axis (see figure 4b) was calculated for all the S-states and compared with the first moments obtained from Mn oxides and Mn coordination compounds in formal oxidation states of (II), (III) and (IV).

The changes per oxidation state in the first moment positions are more pronounced between the Mn oxides than between the Mn coordination complexes. This observation is consistent with a stronger covalency in the coordination complexes. We furthermore observe a Mn oxidation between the S1 and S2 states of PSII, even though the change in the Mn electronic structure is less pronounced than in the oxides. The spectral change per Mn ion between MnIII(acac)3 and MnIV(salicylate) (bipy) is by a factor of 2 more pronounced than between S1 and S2. In other words, the orbital population change per change in oxidation state is largest between the Mn oxides and smallest between S1 and S2. The reason is an increased covalency or delocalization of the Mn valence orbitals in the Mn4Ca cluster in PSII. We thus find that the electron that is transferred from the OEC in PSII between S1 and S2 is strongly delocalized.

Although there has been general agreement with respect to the increasing oxidation of Mn in the cluster during S0 to S1 and S1 to S2, there is a lack of consensus concerning Mn oxidation during S2 to S3. It is also not clear whether the S0 state contains any Mn(II). Recent preliminary results from the S0 and S3 states show that the orbital population change per change in oxidation state between the S2 and S3 states is half as much as that between S0 and S1, or S1 and S2. These results indicate that the electron is removed from a more covalent form or a more delocalized orbital during the S2 to S3 transition compared with the S0 to S1 and S1 to S2 transitions.

These results are in agreement with the earlier qualitative conclusions derived from the shifts in the XANES inflection point energies and the Kβ emission peaks from the S-states and support considering a predominantly ligand-based oxidation during the S2 to S3 transition (Messinger et al. 2001; Yano & Yachandra 2007).

Discussion

C. Dismukes (Princeton University, USA). Do your RIXS data provide more proof for the oxidation state assignments for the Mn ions in PSII versus the earlier XANES data that rely entirely on comparison with reference model compounds?

V. Yachandra. RIXS spectra provide a way for obtaining the effective number of electrons on Mn and also the degree of covalency. Therefore one can reliably determine the charge on the metal, which is Mn4(III2,IV2) in the S1 state, and the changes between the S-states can tell us about the difference in the charge and in the degree of covalency. We find that the electron that is extracted from the OEC between S1 and S2 is strongly delocalized, consistent with strong covalency for the electronic configuration in the OEC. The orbital population change per change in oxidation state between the S2 and S3 states is half as much as that between that between S0 and S1, or S1 and S2 transitions, indicating that the electron is removed from a more covalent form or even more delocalized orbital during this transition.

R. Pace (Australian National University, Canberra, Australia). Is the overall dichroism seen in the EXAFS pattern greater in the oriented PSII membranes than in the rotation patterns from single crystal?

V. Yachandra. The observed dichroism is different for the oriented PSII membranes and crystals, as expected. PSII membranes are oriented in the xy plane, and hence there is no discrimination between x and y, or +z and −z (top and bottom of the PSII membrane). On the other hand, PSII crystals are organized in three dimensions containing four molecules (PSII membranes)/unit cell, which contribute to the differences compared with oriented PSII membranes, and also generate the complicated dichroism pattern. The other parameter that influences the dichroism is the mosaic spread, which is very small (approx. 0.1 degrees) for crystals, but can be large (approx. 20 degrees) for oriented PSII membranes.

J. Barber (Imperial College London, UK). Although EXAFS can give high-resolution spatial information for the Mn cluster, is it correct to call your overall model of the OEC including Ca2+ and the amino acid residues ‘high resolution’? Surely the quality of model is dependent on the accuracy of the positioning of the Ca2+ and the amino acid side chains which at present are at intermediate resolution and perhaps modified by radiation damage.

V. Yachandra. The structure of the Mn cluster determined from single crystal EXAFS is at an accuracy of approximately 0.02 Å in distances and approximately 0.15 Å in resolution. Moreover, the structure of the Mn cluster is independent of the details of the PSII structure determined from X-ray diffraction, or the positioning of the amino acid side chains. Therefore, we think it is justified to refer to the EXAFS-derived Mn cluster as a high-resolution structure, as we are referring only to the Mn cluster, and it does not have anything to do with the overall PSII structure or the vicinity of the Mn cluster in the OEC.

Acknowledgements

The research presented here was supported by the NIH grant GM 55302 (V.K.Y.), and by the Director, Office of Science, Office of Basic Energy Sciences (OBES), Division of Chemical Sciences, Geosciences and Biosciences of the Department of Energy (DOE) under Contract DE-AC02-05CH11231. Grant support from the Deutsche Forschungsgemeinschaft SFB 498, TP C7 to A.Z., and Me 1629/2-4 and from the Max-Planck-Gesellschaft to J.M. are gratefully acknowledged. Synchrotron facilities were provided by the Stanford Synchrotron Radiation Laboratory (SSRL), the Advanced Light Source (ALS) and the Advanced Photon Source (APS) operated by DOE OBES. The SSRL Biomedical Technology programme is supported by NIH, the National Center for Research Resources (NCRR) and the DOE Office of Biological and Environmental Research, and the BioCAT at APS is supported by NCRR.

Footnotes

One contribution of 20 to a Discussion Meeting Issue ‘Revealing how nature uses sunlight to split water’.

References

- Bergmann, U. & Cramer, S. P. 1998 A high-resolution large-acceptance analyzer for X-ray fluorescence and Raman spectroscopy. In SPIE Conference on Crystal and Multilayer Optics, vol. 3448, pp. 198–209. San Diego, CA: SPIE.

- Cinco R.M, Robblee J.H, Rompel A, Fernandez C, Yachandra V.K, Sauer K, Klein M.P. Strontium EXAFS reveals the proximity of calcium to the manganese cluster of oxygen-evolving Photosystem II. J. Phys. Chem. B. 1998;102:8248–8256. doi: 10.1021/jp981658q. doi:10.1021/jp981658q [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cinco R.M, Holman K.L.M, Robblee J.H, Yano J, Pizarro S.A, Bellacchio E, Sauer K, Yachandra V.K. Calcium EXAFS establishes the Mn–Ca cluster in the oxygen-evolving complex of photosystem II. Biochemistry. 2002;41:12 928–12 933. doi: 10.1021/bi026569p. doi:10.1021/bi026569p [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cinco R.M, Robblee J.H, Messinger J, Fernandez C, Holman K.L.M, Sauer K, Yachandra V.K. Orientation of calcium in the Mn4Ca cluster of the oxygen-evolving complex determined using polarized strontium EXAFS of Photosystem II membranes. Biochemistry. 2004;43:13 271–13 282. doi: 10.1021/bi036308v. doi:10.1021/bi036308v [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cramer S.P. Biochemical applications of X-ray absorption spectroscopy. In: Koningsberger D.C, Prins R, editors. X-ray absorption: principles, applications and techniques of EXAFS, SEXAFS, and XANES. Wiley-Interscience; New York, NY: 1988. pp. 257–326. [Google Scholar]

- Dau H, Andrews J.C, Roelofs T.A, Latimer M.J, Liang W, Yachandra V.K, Sauer K, Klein M.P. Structural consequences of ammonia binding to the manganese cluster of the photosynthetic oxygen-evolving complex: an X-ray absorption study of isotropic and oriented photosystem II particles. Biochemistry. 1995;34:5274–5287. doi: 10.1021/bi00015a043. doi:10.1021/bi00015a043 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dau H, Iuzzolino L, Dittmer J. The tetra-manganese complex of photosystem II during its redox cycle—X-ray absorption results and mechanistic implications. Biochim. Biophys. Acta. 2001;1503:24–39. doi: 10.1016/s0005-2728(00)00230-9. doi:10.1016/S0005-2728(00)00230-9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ferreira K.N, Iverson T.M, Maghlaoui K, Barber J, Iwata S. Architecture of the photosynthetic oxygen-evolving center. Science. 2004;303:1831–1838. doi: 10.1126/science.1093087. doi:10.1126/science.1093087 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Flank A.M, Weininger M, Mortenson L.E, Cramer S.P. Single-crystal EXAFS of nitrogenase. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1986;108:1049. doi:10.1021/ja00265a034 [Google Scholar]

- Garman E. Cool crystals: macromolecular cryocrystallography and radiation damage. Curr. Opin. Struct. Biol. 2003;13:545–551. doi: 10.1016/j.sbi.2003.09.013. doi:10.1016/j.sbi.2003.09.013 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- George G.N, Prince R.C, Cramer S.P. The manganese site of the photosynthetic water-splitting enzyme. Science. 1989;243:789–791. doi: 10.1126/science.2916124. doi:10.1126/science.2916124 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Glatzel P, Bergmann U. High resolution 1s core hole X-ray spectroscopy in 3d transition metal complexes—electronic and structural information. Coord. Chem. Rev. 2005;249:65–95. doi:10.1016/j.ccr.2004.04.011 [Google Scholar]

- Glatzel P, et al. The electronic structure of Mn in oxides, coordination complexes, and the oxygen-evolving complex of photosystem II studied by resonant inelastic X-ray scattering. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2004;126:9946–9959. doi: 10.1021/ja038579z. doi:10.1021/ja038579z [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Glatzel P, Yano J, Bergmann U, Visser H, Robblee J.H, Gu W, de Groot F.M.F, Cramer S.P, Yachandra V.K. Resonant inelastic X-ray scattering (RIXS) spectroscopy at the Mn K absorption pre-edge—a direct probe of the 3d orbitals. J. Phys. Chem. Solid. 2005;66:2163–2167. doi: 10.1016/j.jpcs.2005.09.012. doi:10.1016/j.jpcs.2005.09.012 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grabolle M, Haumann M, Mu¨ller C, Liebisch P, Dau H. Rapid loss of structural motifs in the manganese complex of oxygenic photosynthesis by X-ray irradiation at 10–300 K. J. Biol. Chem. 2006;281:4580–4588. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M509724200. doi:10.1074/jbc.M509724200 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Henderson R. Cryo-protection of protein crystals against radiation damage in electron and X-ray diffraction. Proc. R. Soc. B. 1990;241:6–8. doi:10.1098/rspb.1990.0057 [Google Scholar]

- Kamiya N, Shen J.R. Crystal structure of oxygen-evolving photosystem II from Thermosynechococcus vulcanus at 3.7-angstrom resolution. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA. 2003;100:98–103. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0135651100. doi:10.1073/pnas.0135651100 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kok B, Forbush B, McGloin M. Cooperation of charges in photosynthetic O2 evolution. Photochem. Photobiol. 1970;11:457–476. doi: 10.1111/j.1751-1097.1970.tb06017.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Latimer M.J, DeRose V.J, Mukerji I, Yachandra V.K, Sauer K, Klein M.P. Evidence for the proximity of calcium to the manganese cluster of photosystem II: determination by X-ray absorption spectroscopy. Biochemistry. 1995;34:10 898–10 909. doi: 10.1021/bi00034a024. doi:10.1021/bi00034a024 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Latimer M.J, DeRose V.J, Yachandra V.K, Sauer K, Klein M.P. Structural effects of calcium depletion on the manganese cluster of photosystem II: determination by X-ray absorption spectroscopy. J. Phys. Chem. B. 1998;102:8257–8265. doi: 10.1021/jp981668r. doi:10.1021/jp981668r [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Loll B, Kern J, Saenger W, Zouni A, Biesiadka J. Towards complete cofactor arrangement in the 3.0 Å resolution structure of photosystem II. Nature. 2005;438:1040–1044. doi: 10.1038/nature04224. doi:10.1038/nature04224 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Messinger J, et al. Absence of Mn-centered oxidation in the S2 to S3 transition: implications for the mechanism of photosynthetic water oxidation. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2001;123:7804–7820. doi: 10.1021/ja004307+. doi:10.1021/ja004307+ [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mukerji I, Andrews J.C, Derose V.J, Latimer M.J, Yachandra V.K, Sauer K, Klein M.P. Orientation of the oxygen-evolving manganese complex in a photosystem-II membrane preparation—an X-ray-absorption spectroscopy study. Biochemistry. 1994;33:9712–9721. doi: 10.1021/bi00198a042. doi:10.1021/bi00198a042 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Penner-Hahn J.E. Structural characterization of the Mn site in the photosynthetic oxygen-evolving complex. Struct. Bond. 1998;90:1–36. [Google Scholar]

- Pushkar Y, Yano J, Glatzel P, Messinger J, Lewis A, Sauer K, Bergmann U, Yachandra V.K. Structure and orientation of the Mn4Ca cluster in plant photosystem II membranes studied by polarized range-extended X-ray absorption spectroscopy. J. Biol. Chem. 2007;282:7198–7208. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M610505200. doi:10.1074/jbc.M610505200 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rutherford A.W. Orientation of EPR signals arising from components in photosystem II membranes. Biochim. Biophys. Acta. 1985;807:189–201. doi:10.1016/0005-2728(85)90122-7 [Google Scholar]

- Sauer K, Yano J, Yachandra V.K. X-ray spectroscopy of the photosynthetic oxygen-evolving complex. Coord. Chem. Rev. 2008;252:318–335. doi: 10.1016/j.ccr.2007.08.009. doi:10.1016/j.ccr.2007.08.009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scott R.A. X-ray absorption spectroscopy. In: Rousseau D.L, editor. Structural and resonance techniques in biological research. Academic Press; Orlando, FL: 1984. pp. 295–362. [Google Scholar]

- Scott R.A, Hahn J.E, Doniach S, Freeman H.C, Hodgson K.O. Polarized X-ray absorption spectra of oriented plastocyanin single crystals. Investigation of methionine–copper coordination. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1982;104:5364–5369. doi:10.1021/ja00384a020 [Google Scholar]

- Wydrzynski T, Satoh S. Advances in photosynthesis and respiration. Springer; Dordrecht, The Netherlands: 2005. Photosystem II: the light-driven water: plastoquinone oxidoreductase. [Google Scholar]

- Yachandra V.K. X-ray absorption spectroscopy and applications in structural biology. Methods Enzymol. 1995;246:638–675. doi: 10.1016/0076-6879(95)46028-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yachandra V.K. The catalytic manganese-cluster: organization of the metal ions. In: Wydrzynski T, Satoh S, editors. Photosystem II: the light-driven water: plastoquinone oxidoreductase. Springer; Dordrecht, The Netherlands: 2005. pp. 235–260. [Google Scholar]

- Yano J, Yachandra V.K. Oxidation state changes of the Mn4Ca cluster in photosystem II. Photosyn. Res. 2007;92:289–303. doi: 10.1007/s11120-007-9153-5. doi:10.1007/s11120-007-9153-5 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yano J, et al. X-ray damage to the Mn4Ca complex in photosystem II crystals: a case study for metallo-protein X-ray crystallography. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA. 2005a;102:12 047–12 052. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0505207102. doi:10.1073/pnas.0505207102 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yano J, Pushkar Y, Glatzel P, Lewis A, Sauer K, Messinger J, Bergmann U, Yachandra V.K. High-resolution Mn EXAFS of the oxygen-evolving complex in photosystem II: structural implications for the Mn4Ca cluster. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2005b;127:14 974–14 975. doi: 10.1021/ja054873a. doi:10.1021/ja054873a [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yano J, et al. Where water is oxidized to dioxygen: structure of the photosynthetic Mn4Ca cluster. Science. 2006;314:821–825. doi: 10.1126/science.1128186. doi:10.1126/science.1128186 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zouni A, Witt H.-T, Kern J, Fromme P, Krauß N, Saenger W, Orth P. Crystal structure of photosystem II from Synechococcus elongatus at 3.8 Å resolution. Nature. 2001;409:739–743. doi: 10.1038/35055589. doi:10.1038/35055589 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]