Abstract

Using a microfluidic volume sensor, we studied the dynamic effects of Hg2+ on hypotonic stress-induced volume changes in CHO cells. A hypotonic challenge to control cells caused them to swell but did not evoke a significant regulatory volume decrease (RVD). Treatment with 100 μM HgCl2 caused a substantial increase in the steady-state volume following osmotic stress. Continuous hypotonic challenge following a single 10-min exposure to HgCl2 produced a biphasic volume increase with a steady-state volume 100% larger than control cells. Repeated hypotonic challenges to cells exposed once to Hg2+ resulted in a sequential approach to the same steady-state volume. Stimulation after reaching steady state caused a reduction in peak cell volume. Repeated stimulation was different than continuous stimulation resulting in a more rapid approach to steady state. Substituting extracellular Na+ with impermeant NMDG+ in the hypotonic solution produced a rapid RVD-like volume decrease and eliminated the Hg2+-induced excess swelling. The volume decrease in the presence of Hg2+ was inhibited by tetraethylammonium and 4,4′-diisothiocyanatostilbene-2,2′-disulfonic acid disodium, blockers of K+ and Cl- channels, respectively, suggesting that part of the Hg2+ effect was increasing NaCl influx over KCl efflux. The presence of multiple phases of steady-state volume and their sensitivity to the stimulation history suggests that factors beyond solute fluxes, such as modification of mechanical stress within the cytoskeleton also plays a role in the response to hypotonic stress.

Keywords: Cell volume regulation, Na+ transport, Cytoskeleton, Microfluidic, Mercury

Introduction

Inorganic mercury ions and organic mercurials are known to affect membrane transport by binding to the sulfhydryl group of membrane proteins [1, 2] and altering the permeability to inorganic ions [3-7], organic osmolytes [3, 8], and water [9-11]. Hg2+ also affects mitochondrial transport [12-15], cytoplasmic enzymes [2, 16, 17], and the cytoskeleton [18]. Hg2+-modification of Na+, K+, and Cl- permeability leads to changes in cell volume and loss of the regulatory volume decrease (RVD) [3, 7, 19, 20]. Mercurial inhibition of RVD has been reported for many different cell types including MDCK [6], astrocytes [3, 21], and hepatocytes [4, 5], although reportedly acting on different pathways in the different cell types. In MDCK cells, the loss of RVD was ascribed to an enhanced conductance for Na+, K+, and Cl- [6], with the loss of K+ compensated by the influx of Na+. In skate hepatocytes, the effect was attributed to the combined effects of increased Na+ uptake and the inhibition of a taurine permeability [4]. In Ehrlich ascites tumor cells, the response was more complex, with an accelerated RVD followed by a volume increase [22]. This was attributed to the Na+-dependent anion exchange system and K+-Cl- co-transporters. In astrocytes, the inhibition of RVD was attributed to Na+ uptake via the Na+/H+ exchanger (NHE) [21].

Independently, Hg2+ disorganizes the cytoskeleton and cell morphology in many cell types. The formation of blebs in cultured proximal tubule epithelial cells upon exposure to HgCl2 was attributed to the disruption of actin filament attachment to the plasma membrane [23]. Hg2+ disrupts microtubules in IMR-32 neuroblastoma cells [18]. These observations suggest that mercurials may interact with cells at multiple sites and exhibit a collective effect on cell volume. Most studies examine the response to single hypotonic challenge, and the result tends to reflect the involvement of one factor. The dynamic analysis of Hg2+-induced cell volume changes may provide insight into the integrated effect of multiple mechanisms.

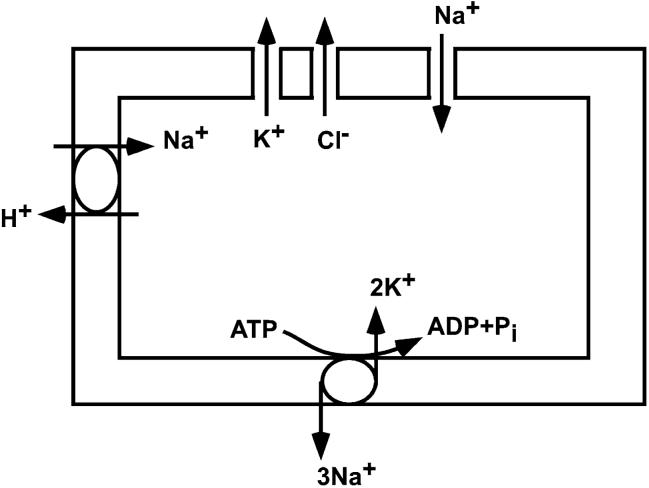

We used a microfluidic cell volume sensor [24] to study the effect of Hg2+ on dynamic changes in cell volume of CHO-K1 cells, a common exogenous expression system. A schematic diagram for the ionic pathways identified from the CHO cells are shown in Fig. 1 [25-30]. The sensor chip allows us to repeatedly expose cultured cells to mercurials and other reagents and to follow the response in real time. Hg2+ caused increased swelling in CHO cells in response to hypotonic challenges, and the steady state proved sensitive to the stimulation history. The effect of Hg2+ on volume not only reflects the changes in membrane transport, but also alteration of cytoskeletal dynamics.

Fig. 1.

Schematic diagram showing ionic channels, transporters, and a pump expressed in CHO cells

Materials and Methods

Chemical Reagents

KCl, NaCl, N-methyl-D-glucamine (NMDG), tetraethylammonium chloride (TEA-Cl), 4,4′-diisothiocyanatostilbene-2,2′-disulfonic acid disodium (DIDS), amiloride, Dulbecco's phosphate buffered saline (D-PBS, with Mg2+ and Ca2+), ouabain, streptomycin, and mannitol were purchased from Sigma-Aldrich (St. Louis, MO). N-2-hydroxyethylpiperazine-N′-2-ethanesulfonic acid (HEPES) and calcium chloride were obtained from Fisher Chemical (Fairlawn, NJ). HgCl2 was purchased from Aceto chemical (Flushing, NY). BCECF-AM and Live/dead viability/cytotoxicity kit for mammalian cells were purchased from Molecular Probes (Eugene, OR).

Solution Preparation

Table 1 shows the composition of various isotonic and hypotonic solutions where, in general, the ionic strength was maintained constant. Solution-I (column I in Table 1) is the normal isotonic and hypotonic solution for all the control runs, in which mannitol was used to adjust the osmolarity. In solutions II-IV, different salts were used to replace NaCl. Since the sensor chip measures the conductivity of the extracellular solution, to reduce transients, the conductivity of the solutions was titrated to equality with NaCl or KCl. The final osmolarity of the solution was measured using an osmometer (Advanced Model 303, Advanced Instrument, Norwood, MA). A 30 mM of HgCl2 stock solution was prepared in deionized water. Stock solutions of 200 mM of amiloride, 100 mM of DIDS, and 1 mM of BCECF-AM were prepared in DMSO and stored in a -20°C. A stock solution of 10 mM of ouabain was prepared in hypotonic solution and stored at room temperature.

Table 1.

Composition of isotonic and hypotonic solutions

| Components (mM) | S-I |

S-II |

S-III |

S-IV |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| NMDG-HEPES |

KCl-HEPES |

TEA-HEPES |

||||||

| Iso | Hypo | Iso | Hypo | Iso | Hypo | Iso | Hypo | |

| NaCl | 75 | 75 | - | - | - | - | - | - |

| KCl | 5 | 5 | - | - | 80 | 80 | 5 | 5 |

| NMDG-Cl | - | - | 75 | 75 | - | - | - | - |

| TEA-Cl | - | - | - | - | - | - | 75 | 75 |

| MgCl2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 |

| CaCl2 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| HEPES | 10 | 10 | 10 | 10 | 10 | 10 | 10 | 10 |

| Mannitol | 150 | 75 | 150 | 75 | 150 | 75 | 150 | 75 |

| pH | 7.4 | 7.4 | 7.4 | 7.4 | 7.4 | 7.4 | 7.4 | 7.4 |

| Osmolaritya | 340 | 258 | 340 | 258 | 340 | 258 | 340 | 258 |

The osmolarity was measured after the conductivity of solutions was titrated to equality with NaCl or KCl

Cell Culture

Microscope slides (thickness 0.96-1.06 mm, Corning, NY) were cut to ~22 × 13 mm to fit the sensor. They were sonicated with 1 M HCl for 30 min and rinsed with deionized water and ethanol. After air-drying, they were sterilized with UV light for 20-30 min. The CHO-K1 cells (ATCC) were grown on the glass in a 35 mm Petri dish using Hams-F12 (F-12K, Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA) containing 10% FBS and penicillin/streptomycin for 3-5 days until the cells covered 70-90% of the area. The passage number was between 7 and 30.

Measurement of Cell Volume Change

The volume sensor chip follows the impedance change of a fixed volume-sensing chamber [24] (a commercial version of this instrument, the CVC-7000, is manufactured by Reichert Instruments, Depew, NY). A glass coverslip containing the cells was inverted over the sensor chip and the chamber resistance measured using a constant current source (100 Hz, 200 nA) with a four-electrode array and phase-lock detection. The cells were perfused sequentially with various solutions. The data were plotted as the ratio of cell volume change to the resting cell volume as described in our previous report [24].

Measurement of Intracellular pH Change

CHO-K1 cells were grown in 50 ml culture flask. After rinsing with D-PBS buffer, the cells were incubated with 2 μM of BCECF-AM in 8 ml of D-PBS buffer at 37°C for 30 min and then rinsed with D-PBS buffer. The cells were then released using a trypsin-EDTA solution, centrifuged, and resuspended with isotonic solution (solution I, Table 1). The washing and centrifugation step was repeated twice. The fluorescence of the cell suspension was measured using spectrofluorimeter (Aminco Bowman series 2, SLM-Aminco, Edison, NJ). The signal was plotted as the ratio of the intensities at 535 nm with excitation at 440 and 490 nm [31].

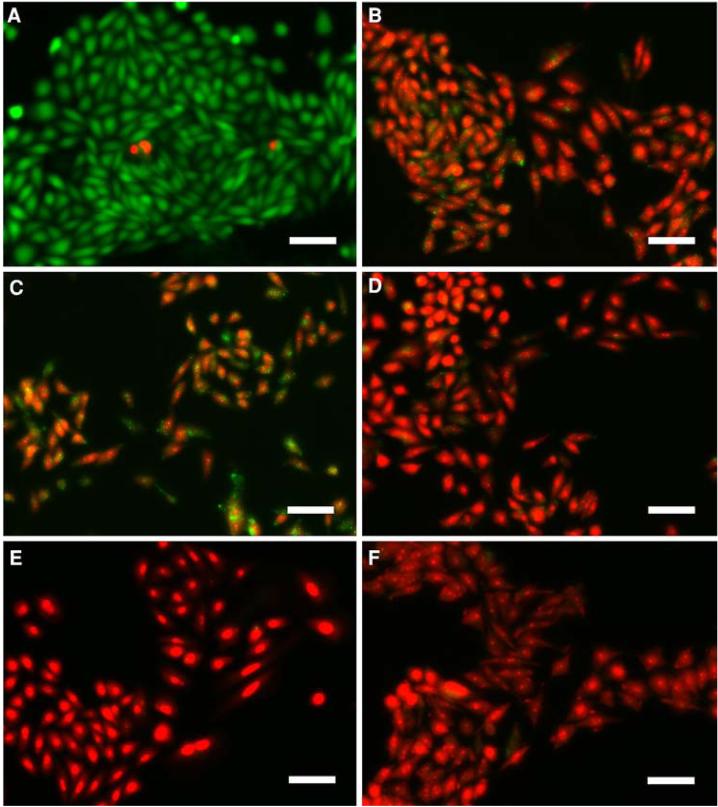

Cell Viability Test after Mercurial Exposure

The cultures were exposed to hypotonic solutions with or without 100 μM HgCl2. They were then incubated with a D-PBS solution containing both 2 μM calcein-AM and 2 μM ethidium dibromide (EthD) at room temperature for 40 min in the dark. The cells were then rinsed with D-PBS thrice. As a control, cells were killed with 70% ethanol. Fluorescent images of the cells were acquired with an inverted microscope (Axiovert 200M, Zeiss) and recorded using a CCD camera (Axiocam MRm, Zeiss). Filter sets 43 (Ex: 545 nm; dichroic filter: 570 nm; Em: 605 ± 70 nm, Zeiss) and 38 HE (Ex: 470 ± 40 nm; dichroic filter: 495 nm; Em: 525 ± 50 nm, Zeiss) were used to view dead and live cells, respectively.

Optical Micrographs of Cells During Mercurial Exposure

Cells were grown in 35 mm Petri dish. After cell culture, media was removed, and the cells were rinsed with isotonic solution several times. Phase contrast optical micrographs were collected every 60 s, while the cells were exposed to 100 μM of HgCl2 in hypotonic solution for 40-50 min.

Transfection with Plasmid Encoding EGFP

When cells grew to 50% confluence, they were transfected with plasmid encoding EGFP using FuGene 6 (Roche Applied Science, IN) and incubated for a day.

Results

Volume Change of CHO-K1 Cells in Hypotonic Media

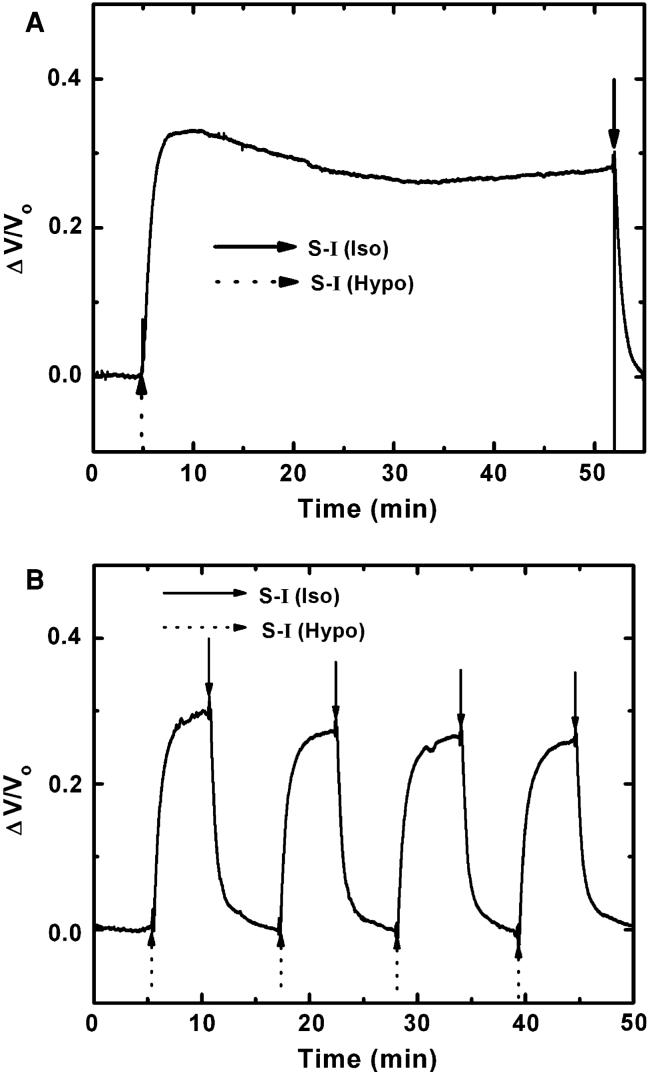

Figure 2a is a representative result showing a volume change of CHO-K1 cells in response to an osmotic shock. We perfused with isotonic solution (S-I, Table 1) then switched to hypotonic. The cells swelled to their maximum volume within 5 min. Unlike other cell lines, CHO-K1 cells showed only a slight RVD and maintained this steady-state volume until the hypotonic solution was switched to isotonic. The extent of RVD was independent of passage number. The steady-state control cell volume in the hypotonic solution (258 mOSm) was ~30% larger than the resting cell volume in isotonic solution (340 mOsm). Figure 2b shows the effect of repeated osmotic challenge. Cell swelling with the first challenge was a little larger than that of subsequent cycles. However, after one or two challenges, the steady-state volume for subsequent challenges was constant. Thus the cells did not lose significant amounts of any osmolyte that was not in the perfusion solution. Optical microscopy confirmed that there was no significant detachment of cells from the coverslip during repeated challenges.

Fig. 2.

(a) Volume change of CHO-K1 cells in response to a hypotonic challenge (S-I, Table 1). (b) Volume changes in response to several perfusion cycles of hypotonic and isotonic solutions (S-I, Table 1). The solid and dotted arrows indicate the solution exchange to isotonic and hypotonic, respectively

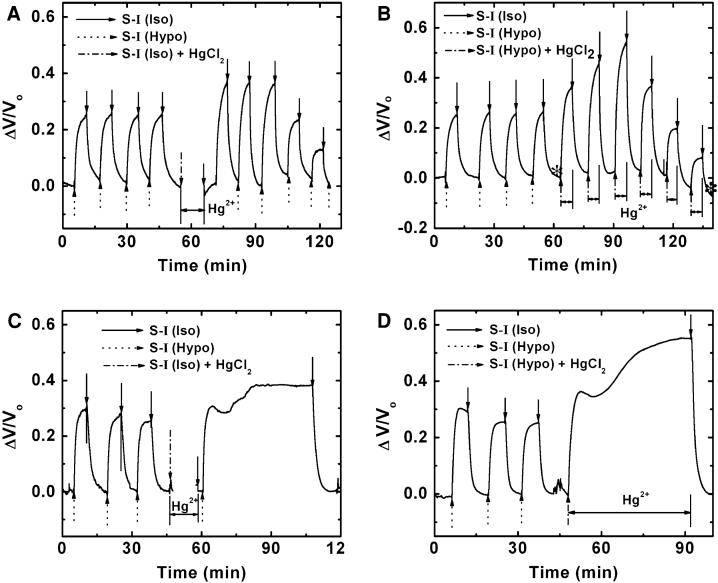

The Effect of HgCl2 on Cell Volume

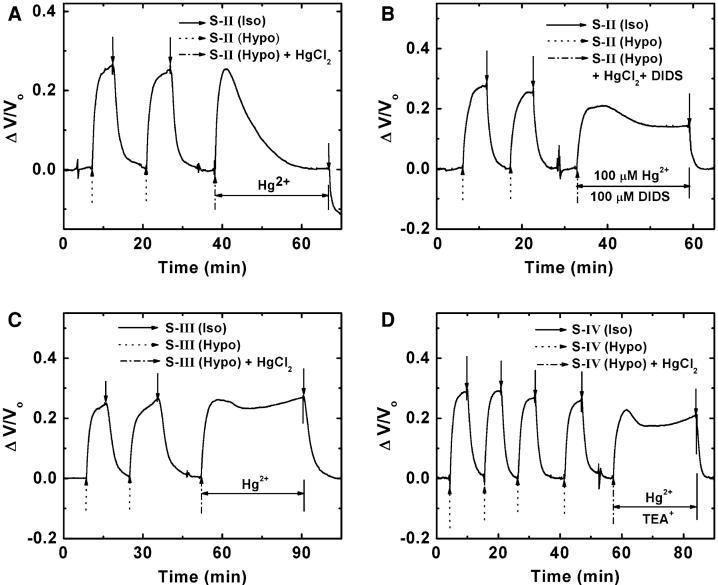

We examined the effects of HgCl2 using four different protocols as shown in Fig. 3a-d. In the beginning of each experiment, we challenged the cells with normal hypotonic solution several times to establish a steady-state response and followed with solutions containing HgCl2. In Fig. 3a, the arrows on the first four responses indicate the maximum control cell volume changes. We then perfused isotonic solution containing 100 μM HgCl2 for 10 min, followed by Hg2+-free isotonic and hypotonic solutions. After washing out the remaining HgCl2 from the chamber, repeated hypotonic challenges caused an initial swelling that peaked and began a slow decay to steady state.

Fig. 3.

Effects of HgCl2 on cell volume. (a) Response to hypotonic challenges before and after a single 100 μM HgCl2 treatment. Notice that the effect of Hg2+ treatment is to cause the initial response to hypotonic challenge to be larger than controls and subsequent stimuli to be smaller. (b) Responses to hypotonic challenge with multiple exposures of 100 μM HgCl2. (c) Long-term osmotic challenge following a single application of 100 μM HgCl2. Note that the cells remain swollen to a larger volume than the controls. Compare this to (a) where repeated stimulation causes a decrease in volume. (d) Long-term osmotic challenge with continuous application of HgCl2. As with the acute stimuli, the Hg2+ reaction appears complete within 10 min. Note that there is a biphasic response to the hypotonic stimulus with an initial peak followed by a slow swelling phase indicating multiple sites of action for Hg2+

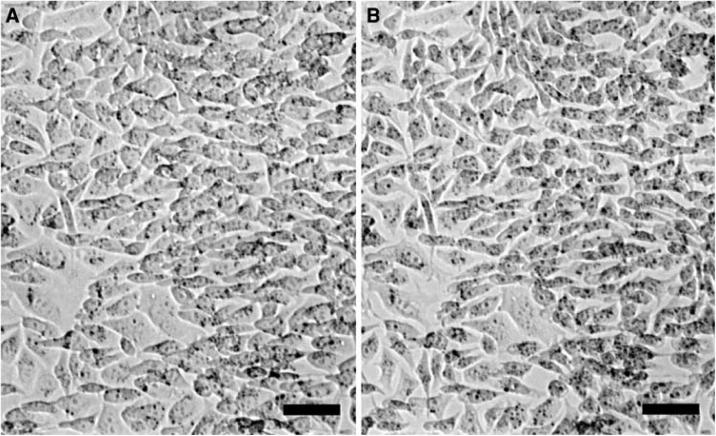

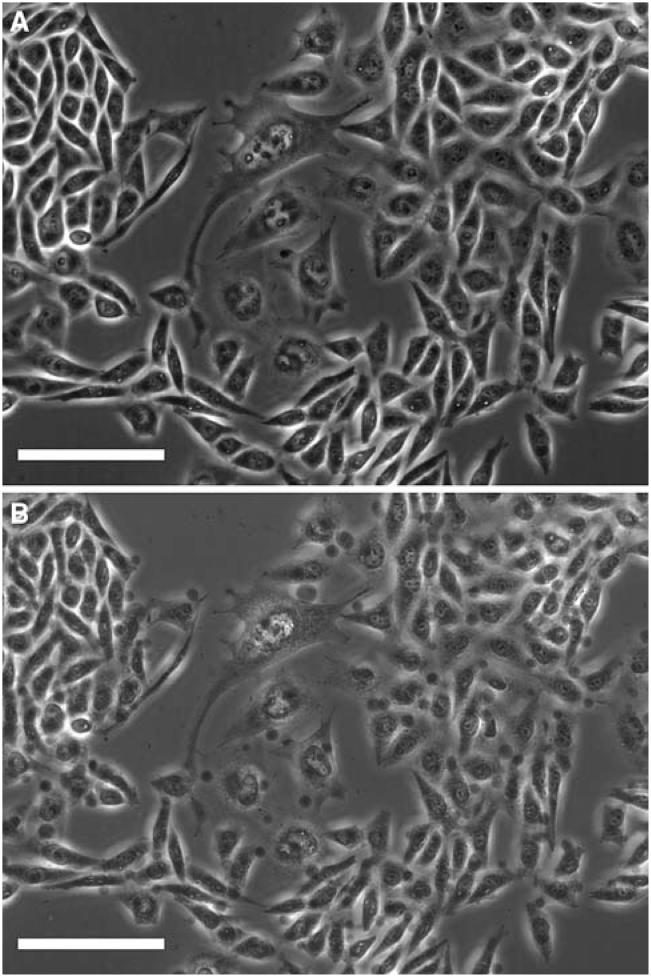

In order to observe the kinetics of the Hg2+ effects, we repeatedly perfused the chamber with Hg2+-containing hypotonic solution (Fig. 3b). The similarity between Fig. 3a and b suggests that 100 μM HgCl2 reacts on the scale of minutes. Figure 3a shows that even after Hg2+ washout, the response to a hypotonic challenge continues to decrease after the initial excess swelling, suggesting that Hg2+ irreversibly binds to the cells and acts progressively on cellular function. Note that the baseline volume in isotonic solution (Fig. 3a, b) is constant indicating no significant loss of ions during repeated stimulation. The decrease in the steady-state cell volume does not involve a loss of cells from the coverslip, as shown in optical micrographs obtained during the solution exposure (Fig. 4a, b).

Fig. 4.

The optical micrographs of the cells in the sensor before and after multiple exposures to HgCl2. (a) Before exposure (corresponding to the moment of the first asterisk in Fig. 3b). (b) After the sixth exposure (the second asterisk in Fig. 3b). Note that there was no loss of cells

Because the peak volume decreased over time, we measured the response to long-term Hg2+-free hypotonic challenge after a single Hg2+ treatment (Fig. 3c) and long-term hypotonic challenge with Hg2+-containing solution (Fig. 3d). The responses commonly exhibited two phases: a primary peak that was followed by a slower increase to 1.5 and 2.3 times the steady-state peak, respectively (Fig. 3c, d). The primary swelling shown in Fig. 3c, d resulted in a quasi-steady state with slightly higher volume than control cells. However, a steady-state cell volume was established only after the second phase volume increase in Fig. 3c, d. The steady-state volumes were consistent with the maximum volume observed in Fig. 3a, b, however, with repeated hypotonic challenges, Hg2+ decreased the peak swelling whereas with continued hypotonic exposure, Hg2+ maintained the peak swelling. Clearly there is hysteresis in the system and it is not in equilibrium, but the relevant reactions that are responsible are not yet understood.

We did not see the change in water permeability in the presence of Hg2+ although Hg2+ is a known blocker for most mammalian AQPs except AQP4 and AQP6 [9, 32]. If the rate of rise to a challenge represents the rate of water influx, apparently AQPs do not play a major role in water permeability of CHO cells.

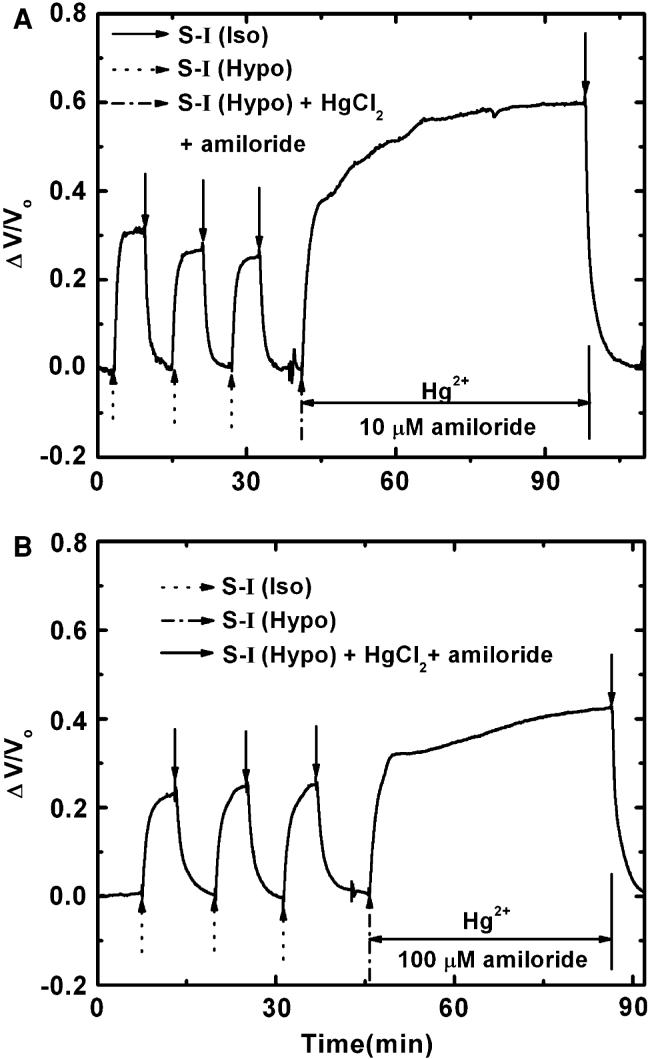

Hg2+ Effects on Ion Transport

Hg2+ produces a large increase in Na+ uptake [3, 4, 6, 21]. In order to assess the contribution of Na+ in our case, we replaced Na+ with the impermeant cation NMDG+ [6] in both isotonic and hypotonic solutions (S-II, Table 1). We initially perfused the cells with normal isotonic and hypotonic solutions (the first two peaks in Fig. 5a), and after the cells recovered their resting volume in isotonic solution, we applied hypotonic solution containing 100 μM HgCl2 to the same cells. Figure 5a shows that in NMDG saline, Hg2+ did not produce a large steady-state volume, but instead a rapid volume decrease. When the Hg2+-containing hypotonic solution was switched to isotonic solution, the cells shrank below the resting volume suggesting a loss of intracellular solutes during Hg2+ treatment in Na+-free saline. This cell volume decrease has been attributed to the efflux of KCl induced by Hg2+ [6], although we seldom observed significant RVD in control cells (Fig. 2a). Presumably, the resting volume of the cell reflects a steady-state exchange of Na+ and K+, and removal of extracellular Na+ causes the KCl efflux to dominate. Comparing Figs. 5a with 3c, d, the similarity in the time course of initial volume increase after HgCl2 exposure suggests that the passive influx of water was not affected by Hg2+. The alternation in osmotic pressure caused by kinetic balance between Hg2+-induced Na+ uptake and KCl release is responsible for the primary peak.

Fig. 5.

The response of cell volume in the absence of Na+. (a) Hypotonic stimulation in the presence of Hg2+ produces an RVD-like response. (b) Block of Cl- channels with 100μM DIDS eliminates the RVD-like response in the presence of Hg2+. (c) Substitution of Na+ with K+ reversing the K+ gradient also eliminates the RVD-like response. (d) Block of K channels with 75 mM TEA also eliminates the RVD-like response

In order to confirm the participation of Cl- fluxes, we applied DIDS, a Cl- channel blocker [33]. After obtaining the control responses, we perfused with a hypotonic solution containing 100 μM HgCl2 and 100 μM DIDS. Figure 5b shows that DIDS inhibited the rapid decrease in cell volume. This result suggests that Cl- fluxes are involved in the volume response in Fig. 5a. We also examined the K+ flux explicitly by replacing Na+ with K+ in both isotonic and hypotonic solutions (S-III, Table 1), and by replacing Na+ with TEA+, a K+ channel blocker (S-IV, Table 1) [34]. As shown in Fig. 5c, the reduction of the K+ concentration gradient eliminates the rapid cell shrinking (compare with Fig. 5a). In the absence of K+ permeation, we did not observe the excess cell swelling due to the presence of Hg2+ or the rapid volume decrease (Fig. 5d relative to the controls of Fig. 5a). K+ channel blockade in the presence of Hg2+ produced a similar response to Cl- channel blocker (Fig. 5b). This suggests that, as expected, the volume changes can only be affected by moving neutral species, and in this case KCl, probably through independent K+ and Cl- channels.

Hg2+-sensitive Na+ Transport Pathways

There are four likely transport pathways that can be altered by Hg2+ leading to abnormal volume changes: the epithelial Na+ channels [6], the NHE [20, 21, 35], Na+/Cl-, or Na+/K+/2Cl- co-transporters [36, 37], and the Na+-K+-ATPase [17, 38]. We excluded the contribution from Na+/Cl- or Na+/K+/2Cl- co-transporters, because Hg2+ inhibits them [36, 37]. In order to examine the role of the Na+-K+-ATPase, we exposed the cells to hypotonic solution containing 1.2 mM ouabain, an inhibitor for the Na+-K+-ATPase, with and without 100 μM HgCl2. Ouabain did not alter the cells response to a hypotonic challenge (data not shown). Since Hg2+ did produce large changes in cell volume upon challenge, it could not have done so by inhibiting the Na+-K+-ATPase.

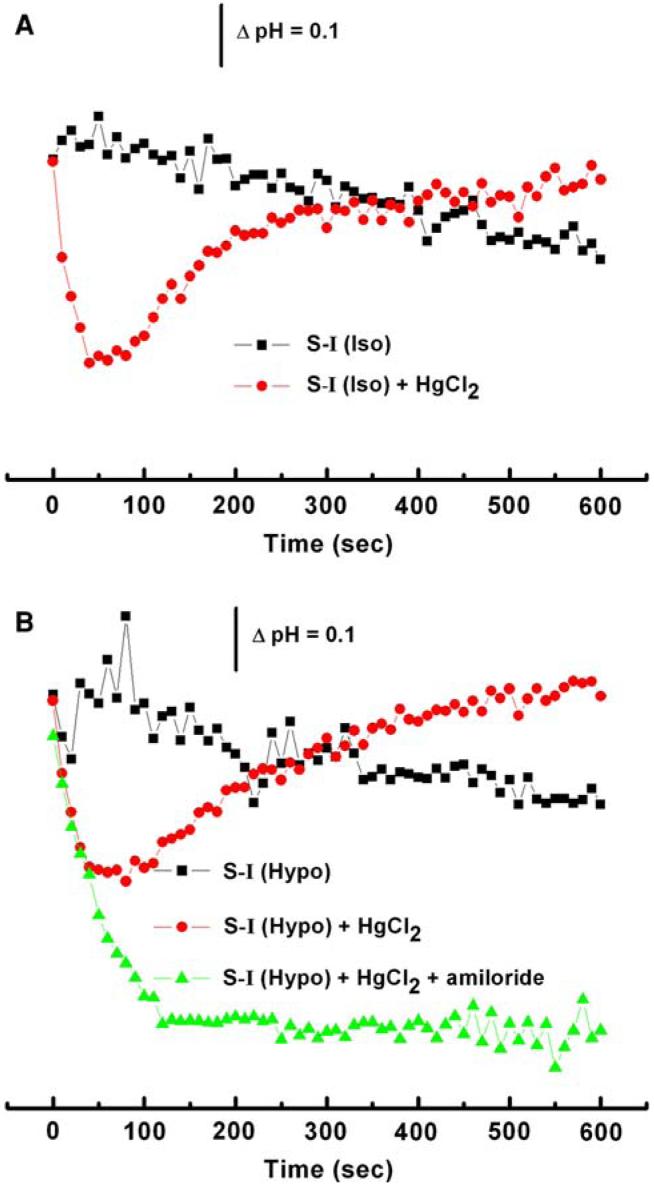

It has been reported that the Hg2+ increased Na+ uptake through epithelial Na+ channels in MDCK cells and the NHE in astrocytes [6, 21]. Amiloride apparently acts as a blocker for both pathways [39]; submicromolar amiloride will block Na+ channels, but >1 μM amiloride also blocks the NHE. The slow phase volume increase seen in Fig. 3d was partially reduced by 100-μM amiloride (see Fig. 6b); however, neither the primary nor the secondary increase was blocked by 10-μM amiloride (Fig. 6a). This suggests Na+ channels are unlikely to be responsible for the Hg+2-induced excess swelling.

Fig. 6.

Effect of amiloride on Hg2+ effects. (a) 10 μM amiloride and (b) 100 μM amiloride. Amiloride in high enough concentrations to block ENaC and NHE partially blocked the second swelling

It has been reported that Hg2+ can decrease intracellular pH [20, 40] and this drop in intracellular pH could activate the NHE [41]. We loaded cells with BCECF, a pH-sensitive fluorescent dye. In control solutions, the pH was insensitive to volume changes suggesting that NHE was not stimulated by swelling alone (Fig. 7a, b). However, in Hg2+-containing solutions, the cytoplasmic pH rapidly decreased and then slowly returned to normal (Fig. 7a, b). The return alkalinization was blocked by high concentrations of amiloride suggesting that the NHE was involved (Fig. 7b).

Fig. 7.

Intracellular pH following 100 μM Hg2+ treatment. (a) In isotonic media, Hg2+ induces a sudden drop in pH that recovers within 2 min. (b) Hypotonic media introduces a similar response to isotonic media, but amiloride at 1 mM that eliminates the pH recovery

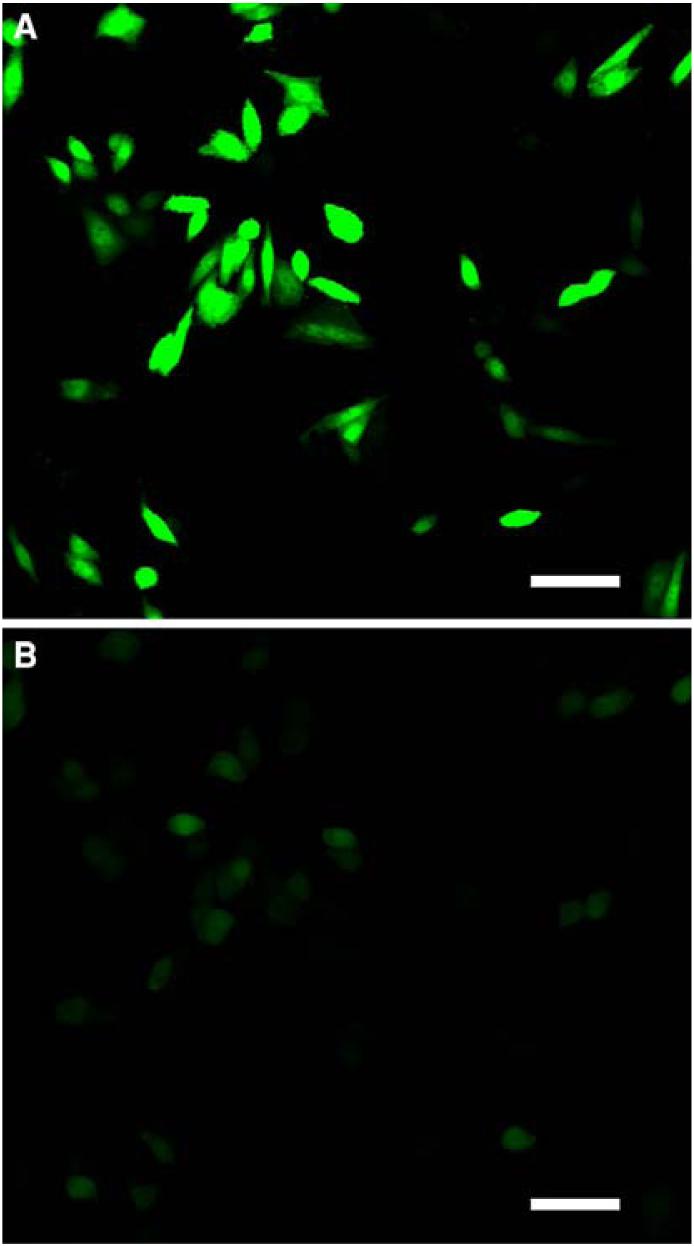

Mercurial Effects on Cytoskeleton

We found that Hg2+ was permeant to CHO cells and the permeability is enhanced in hypotonic conditions. EGFP in solution is photobleached in the presence of Hg2+. When EGFP is expressed in the cells, in isotonic solution external Hg2+ causes a slow photobleaching (Fig. 8a). However, when the cells are exposed to Hg2+ in a hypotonic solution, the EGFP photobleaches within 20 s (Fig. 8b) showing that swelling induces Hg2+ permeation. The permeation pathway for Hg2+ is unknown, it may be through the lipid membranes [42] but not via stretch activated ion channels (C. L. Bowman and F. Sachs, unpublished results).

Fig. 8.

Photobleaching of EGFP in the presence of Hg2+. Confocal micrographs of EGFP-expressing cells. (a) In isotonic solution containing 100 μM Hg2+ the cells do not photobleach. (b) Immediately after exposure to hypotonic media the cells photobleach showing that Hg2+ enters swollen cell. The scale bar indicates 50 μm

It was reported that cells treated with HgCl2 reorganized the actin filament structure associated with bleb formation [23]. We examined the blebbing of CHO cells before and after a 40-min exposure to Hg2+ in hypotonic solution (Fig. 9a, b). Blebs occurred after 15-20 min of treatment. Similar blebbing was observed when the cells were treated with 100 μM cytochalasin-B suggesting the Hg2+ effect may have been the result of actin filament disruption. Hg2+ injury to cytoskeleton and the slow phase of cell swelling occur in the same time period. Supporting information in the movie files (M-I, II) also suggests Hg2+ interaction with cytoskeleton. Membrane ruffles related to the reorganization of cytoskeleton were observed in control solutions (MI), but in contrast, immediately after the cells were exposed to Hg2+, the membrane ruffles disappeared and blebs began to form (M-II).

Fig. 9.

Optical micrographs showing bleb formation during sustained Hg2+ exposure. (a) CHO cells in the isotonic solution after 40 min. (b) CHO cells in the Hg2+-containing hypotonic solution after 40 min. Several blebs can be clearly seen around the cells. The scale bar indicates 50 μm

We checked cell viability using calcein-AM and EthD [43]. Repeated challenges in normal hypotonic solution did not affect membrane integrity (Fig. 10a). However, when treated with 100 μM HgCl2 in isotonic solution for 10 min, the cells became leaky for the EthD dye (Fig. 10b). The cells were damaged progressively when they were repeatedly exposed to hypotonic solution containing 100 μM Hg2+ (Fig. 10c-e). The dye leakage also appeared when the cells were stimulated for 45 min in Hg2+-containing hypotonic solution (Fig. 10f). Membrane damage in the presence of Hg2+ may lead to the loss of response to repeated challenges (Fig. 3a, b); however, it cannot explain the large increase in volume with sustained Hg2+ stimulation (cf. Fig. 3c, d).

Fig. 10.

Cell viability tests following exposure to 100 μM Hg2+. Red indicates dead cells and green the live cells. (a) After four cycles of exposures to Hg2+-free hypotonic/isotonic solutions. (b) After exposure to isotonic solution containing Hg2+ for 10 min. (c) The response after exposure to Hg2+-containing hypotonic and Hg2+-free isotonic solutions for 5 min each. (d) The response after two exposures to Hg2+-containing hypotonic and Hg2+-free isotonic solution. (e) The response after four exposures to Hg2+-containing hypotonic and Hg2+-free isotonic solution. (f) Steady-state exposure to hypotonic solution containing HgCl2 after 45 min. The scale bar indicates 50 μm. Note that repeated exposures to Hg2+-free hypotonic solution does not damage cell membrane as assayed by dye permeation. However, a brief exposure to Hg2+ even in isotonic solution can affect dye transport

Discussion

Cell volume is a function of the cell's water content. That in turn is a function of the solute content and mechanical stresses within the cytoskeleton. The steady-state volume could be a kinetic balance of influx and efflux and/or an equilibrium between the hydration state of solutes and the stress in the cytoskeleton, and Hg2+ exposure appears to alter both the membrane permeability and the cytoskeleton.

Hg2+ inhibits RVD in most cell types and this has been attributed to rebalancing of the flux of solutes [3, 4, 6, 21]. The control cells in this study showed weak RVD with a hypotonic challenge (Fig. 2a). This weak RVD of CHO cells has been reported by other groups and was attributed to a lack of TRPV-4 channels that are purportedly volume sensitive [44]. In our experiments in response to a hypotonic challenge HgCl2-treated cells produced a biphasic swelling (Fig. 3); a fast swelling to 30% above the control volume followed by the slow phase to twice the control volume. Hg2+ increased the maximum steady-state volume. Frequent challenges caused Hg2+-treated cells to reach steady state more rapidly.

The interaction of Hg2+ with membrane proteins appeared to promote Na+ uptake and caused the initial swelling (Fig. 3). This is in agreement with findings from other cell lines [4, 21, 45]. In the absence of Na+, there is no RVD, but treatment with Hg2+ in the absence of Na+ generates an RVD-like response (Fig. 5a) involving KCl efflux suggesting this KCl pathway is not normally functional. The pathway for KCl transport seems to be via separate ion channels since the volume decrease could be inhibited by either DIDS (a Cl- channel blocker) or TEA (a K+ channel blocker) as shown in Fig. 5b, d. The slight volume decrease after K and Cl blockade suggests that other osmolytes, such as amino acids, may contribute [4, 21]. The Hg2+ effects on ion transport appear to account for the primary phase of the response to a hypotonic challenge. The slight decrease following the primary peak observed with Hg2+-treated cell (Fig. 3c, d) probably reflects an adjustment in osmotic pressure in response to the kinetic balance of NaCl influx and KCl efflux. The identity of the Na+ transport pathway as NHE was supported by the response to amiloride and intracellular pH measurements, and this suggests that Hg2+ potentiates NHE.

The secondary swelling in a sustained hypotonic perfusion after HgCl2 treatment (Fig. 3c, d) appears to involve more than just NHE. Hypotonic stimulation produces some membrane blebbing after the sustained mercurial treatment (Fig. 9b and also supporting information, M-II). The blebbing is similar to that observed in cytochalasin-treated cells suggesting Hg2+-induced cytoskeleton reorganization [46, 47]. This is consistent with our observation that EGFP photobleached upon cell swelling (Fig. 8) as Hg2+ entered the cell under hypotonic stress. Previous reports have shown that Hg2+ disrupt both microtubules [48] and actin filaments [23]. Blebbing has been attributed to weakened adhesion between the bilayer and the cytoskeleton or disorganization of the cytoskeleton [49]. We found that the time required for bleb formation (15-20 min) coincided with the time required to reach the peak swelling (Fig. 3c, d), suggesting the possible contribution of cytoskeleton structure to second swelling. Note that although blebs are considered as part of the cell volume, the measured volume change is mainly produced by cells not blebs. In situ recordings of volume and optical micrographs show that the number and size of blebs does not make a significant contribution. In those experiments, the measured cell volume change was more than 100%, while the estimated total volume of the blebs was less than 15%.

One of the striking results in this work is that the history of stimulation leads to different steady-state cell volumes so that cell volume cannot be considered a state variable set by the environmental conditions. Repeated hypotonic challenges resulted in a successive reduction in cell volume (Fig. 3a, b). Alternate swelling and shrinking caused effects not seen with continuous swelling (Fig. 3d) probably as a result of cytoskeletal reorganization. The different swelling characteristics are sensitive to the stimulation dynamics and cannot be simply explained by the Hg2+- induced changes in the ionic transport. Hypotonic stress causes changes in F-actin organization [50]. Hg2+ can readily disrupt sulfhydryl groups essential to cytoskeletal structure.

The cell membranes proved to be robust with respect to repeated challenges (cf., Figs. 2b and 10a), and in a sustained challenge in the presence of Hg2+ (Fig. 3c, d), although Hg2+ treatment did make the cells more permeable to EthD (Fig. 10b-f) regardless of the stimulation protocol. This effect is probably true for other dye tracers [51]. If the challenges in the presence of Hg2+ caused membrane lysis, we should have not observed an increase in volume, but we did. These facts suggest that change in dye permeability was not the result of lysis.

The most difficult observation to explain is that the cells can swell to a stable volume under osmotic pressures ~2 atm, the 80 mOsm osmotic pressure difference between the isotonic and the hypotonic saline. Taking the traditional view that the cell is a semipermable bag, we would need the membrane to withstand a pressure of 2 atm in steady state. According to Laplace's law, the tension in a membrane is given by T = ΔPr/2 where ΔP is the pressure gradient and r is the radius of curvature. If the cell had a mean radius of 5 μm, the membrane tension would be ~500 mN/m, but the lytic tension of bilayers is <10 mN/m [52-54]. Thus, in the traditional membrane-limiting model, the only way to explain the cell's stability under apparently large osmotic pressures is that most of the osmolytes left the cell following a challenge. But if this were the explanation, the response to the next challenge would reflect the fact that the cell had few solutes so the cell would only swell a small amount. This did not happen in the repeated challenges.

The alternative explanation is that much of the osmotic stress is shared by the cytoskeleton so that the cell behaves much like a sponge wrapped with a membrane. Sponges swell when exposed to water but they do not lyse because the elastic stress of the walls of the sponge balances the entropically driven influx of water. With a membrane bound to the cytoskeleton, the radius of curvature is reduced and the tension falls proportionately. The idea that the cytoskeleton is involved in osmotic regulation is not new [55-57] and we are inclined to go along with that interpretation. Furthermore, we are unaware of any data suggesting that the cytoskeleton is free from stress during swelling, and if there is stress, that will add to the equilibrium balance of free energy.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

This work is supported by National Institute of Health Grant DK77302, NHLBI (FS) and by New York State Office of Science, Technology & Academic Research (NYSTAR).

Footnotes

Electronic supplementary material The online version of this article (doi:10.1007/s12013-008-9010-y) contains supplementary material, which is available to authorized users.

References

- 1.Atchison WD, Hare MF. Mechanisms of methylmercury-induced neurotoxicity. FASEB Journal. 1994;8:622–629. doi: 10.1096/fasebj.8.9.7516300. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Zalups RK. Molecular interactions with mercury in the kidney. Pharmacological Review. 2000;52:113–143. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Aschner M, Vitarella D, Allen JW, Conklin DR, Cowan KS. Methylmercury-induced inhibition of regulatory volume decrease in astrocytes: Characterization of osmoregulator efflux and its reversal by amiloride. Brain Research. 1998;811:133–142. doi: 10.1016/s0006-8993(98)00629-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ballatori N, Boyer JL. Disruption of cell volume regulation of mercuric chloride is mediated by an increase in sodium permeability and inhibition of an osmolyte channel in skate hepatocytes. Toxicology and Applied Pharmacology. 1996;140:404–410. doi: 10.1006/taap.1996.0237. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ballatori N, Shi C, Boyer JL. Altered plasma membrane ion permeability in mercury-induced cell injury: Studies in heptatocytes of elasmobranch Raja erinacea. Toxicology and Applied Pharmacology. 1988;95:279–291. doi: 10.1016/0041-008x(88)90164-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Rothstein A, Mack E. Actions of mercurials on cell volume regulation of dissociated MDCK cells. American Journal of Physiology. Cell Physiology. 1991;260:C113–C121. doi: 10.1152/ajpcell.1991.260.1.C113. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Aschner M, Eberle NB, Miller K, Kimelberg HK. Interactions of methylmercury with rat primary astrocyte cultures: Inhibition of rubidium and glutamate uptake and induction of swelling. Brain Research. 1990;530:245–250. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(90)91290-w. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Albrecht J, Talbot M, Kimelberg HK, Aschner M. The role of sulfhydryl groups and calcium in the mercuric chloride-induced inhibition of glutamate uptake in rat primary astrocyte cultures. Brain Research. 1993;607:249–254. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(93)91513-r. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Yasui M, Hazama A, Kwon T-H, Nielsen S, Guggino WB, Agre P. Rapid gating and anion permeability of an intracellular aquaporin. Nature. 1999;402:184–187. doi: 10.1038/46045. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Barone LM, Shih C, Wasserman BP. Mercury-induced conformational changes and identification of conserved surface loops in plasma membrane aquaporins from higher plants: Topology of PMIP31 from Beta vulgaris L. Journal of Biological Chemistry. 1997;272:30672–30677. doi: 10.1074/jbc.272.49.30672. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hazama A, Kozono D, Guggino WB, Agre P, Yasui M. Ion permeation of AQP6 water channel protein. Journal of Biological Chemistry. 2002;277:29224–29230. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M204258200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Chavez E, Holguin JA. Mitochondrial calcium release as induced by Hg2+ Journal of Biological Chemistry. 1988;263:3582–3587. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Chavez E, Zazueta C, Osornio A, Holguin JA, Miranda ME. Protective behavior of captopril on Hg2+-induced toxicity on kidney mitochondria: In vivo and in vitro experiments. Journal of Pharmacological and Experimental Therapeutics. 1991;256:385–390. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Lund B-O, Miller DM, Woods JS. Studies on Hg(II)-induced H2O2 formation and oxidative stress in vivo and in vitro in rat kidney mitochondria. Biochemical Pharmacology. 1993;45:2017–2024. doi: 10.1016/0006-2952(93)90012-l. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Weinberg JM, Harding PG, Humes HD. Mitochondrial bioenergetics during the initiation of mercuric chloride-induced renal injury: I. Direct effects of in vitro mercuric chloride on renal mitochondrial function. Journal of Biological Chemistry. 1982;257:60–67. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Anner BM, Moosmayer M, Imesch E. Chelation of mercury by ouabain-sensitive and ouabain-resistant renal Na+/K+-ATPase. Biochemical and Biophysics Research Communications. 1993;167:1115–1121. doi: 10.1016/0006-291x(90)90638-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Anner BM, Moosmayer M, Imesch E. Mercury blocks Na-K-ATPase by a ligand-dependent and reversible mechanism. American Journal of Physiology. Renal Physiology. 1992;262:F830–F836. doi: 10.1152/ajprenal.1992.262.5.F830. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Stoiber T, Degen GH, Bolt HM, Unger E. Interaction of mercury (II) with the microtubule cytoskeleton in IMR-32 neuroblastoma cells. Toxicology Letters. 2004;151:99–104. doi: 10.1016/j.toxlet.2003.11.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Mel HC, Reed TA. Biophysical responses of red cell-membrane systems to very low concentrations of inorganic mercury. Cell Biophysics. 1981;3:233–250. doi: 10.1007/BF02782626. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Jensen BS, Kramhoeft B, Jessen F, Lambert IH, Hoffmann EK. HgCl2-induced ion transport pathways in Ehrlich ascites tumor cells. Cellular Physiology and Biochemistry. 1993;3:97–110. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Vitarella D, Kimelberg HK, Aschner M. Inhibition of regulatory volume decrease in swollen rat primary astrocyte cultures by methylmercury is due to increased amiloride-sensitive Na+ uptake. Brain Research. 1996;732:169–178. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(96)00518-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kramhoft B, Lambert IH, Pedersen R. Mercuric chloride activates latent, anion-dependent cation transport systems in the plasma membrane of Ehrlich ascites tumor cells. Pharmacology and Toxicology. 1989;64:421–425. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0773.1989.tb00679.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Elliget KA, Phelps PC, Trump BF. Mercury(II) chloride-induced alteration of actin filaments in cultured primary rat proximal tubule epithelial cells. Cell Biology and Toxicology. 1991;7:263–280. doi: 10.1007/BF00250980. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Ateya DA, Sachs F, Gottlieb PA, Besch S, Hua SZ. Volume cytometry: Microfluidic sensor for high-throughput screening in real time. Analytical Chemistry. 2005;77:1290–1294. doi: 10.1021/ac048799a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Garnovskaya MN, Mukhin YV, Vlasova TM, Raymond JR. Hypertonicity activates Na+/H+ exchange through Janus kinase 2 and Calmodulin. Journal of Biological Chemistry. 2003;278:16908–16915. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M209883200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Qian N-X, Pastor-Anglada M, Englesberg E. Evidence for coordinating regulation of the A system for amino acid transport and the mRNA for the a1 subunit of the Na+, K+-ATPase gene in Chinese hamster ovary cells. Proceedings of National Academy of Sciences of the USA. 1991;88:3416–3420. doi: 10.1073/pnas.88.8.3416. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Tonini R, Ferroni A, Valenzuela SM, Warton K, Campbell TJ, Breit SN, Mazzanti M. Functional characterization of the NCC27 nuclear protein in stable transfected CHO-K1 cells. FASEB Journal. 2000;14:1171–1178. doi: 10.1096/fasebj.14.9.1171. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Gabriel SE, Price EM, Boucher RC, Stutts MJ. Small linear chloride channels are endogenous to non-epithelial cells. American Journal of Physiology. Cell Physiology. 1992;263:C708–C713. doi: 10.1152/ajpcell.1992.263.3.C708. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Lalik P, Krafte DS, Volberg WA, Ciccarelli RB. Characterization of endogeneous sodium channel gene expressed in Chinese hamster ovary cells. American Journal of Physiology. Cell Physiology. 1993;264:C803–C809. doi: 10.1152/ajpcell.1993.264.4.C803. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Skryma R, Prevarskaya N, Vacher P, Dufy B. Voltage-dependent Ca2+ channels in Chinese hamser ovary (CHO) cells. FEBS Letters. 1994;349:289–294. doi: 10.1016/0014-5793(94)00690-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Alvarez-Leefmans FJ, Herrera-Perez JJ, Marquez MS, Blanco VM. Simultaneous measurement of water volume and pH in single cells using BCECF and fluorescence imaging microscopy. Biophysical Journal. 2006;90:608–618. doi: 10.1529/biophysj.105.069450. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Borgnia M, Nielsen S, Engel A, Agre P. Cellular and molecular biology of the aquaporin water channels. Annual Review of Biochemistry. 1999;68:425–428. doi: 10.1146/annurev.biochem.68.1.425. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Golgelein H. Chloride channels in epithelia. Biochimica et Biophysica Acta. 1988;947:521–547. doi: 10.1016/0304-4157(88)90006-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Ikeda SR, Korn SJ. Influence of permeating ions on potassium channel block by external tetraethylammonium. Journal of Physiology. 1995;486:267–272. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1995.sp020809. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Pourahmad J, O'Brien PJ. Involvement of intracellular Na+ accumulation in Hg2+ or Cd2+ induced cytotoxicity. Journal de Physique IV: Proceedings. 2003;107:1095–1098. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Vazquez N, Monroy A, Dorantes E, Munoz-Clares RA, Gamba G. Functional differences between flounder and rat thazide-sensitive Na-Cl cotransporter. American Journal of Physiology. Renal Physiology. 2002;282:F599–F607. doi: 10.1152/ajprenal.00284.2001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Jacoby SC, Gagnon E, Caron L, Chang J, Isenring P. Inhibition of Na+-K+-2Cl- cotransport by mercury. American Journal of Physiology. Cell Physiology. 1999;277:C684–C692. doi: 10.1152/ajpcell.1999.277.4.C684. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Anner BM, Moosmayer M. Mercury inhibits Na-KATPase primarily at the cytoplasmic side. American Journal of Physiology. Renal Physiology. 1992;262:F843–F848. doi: 10.1152/ajprenal.1992.262.5.F843. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Benos DJ. Amiloride: A molecular probe of sodium transport in tissues and cells. American Journal of Physiology. Cell Physiology. 1982;242:C131–C145. doi: 10.1152/ajpcell.1982.242.3.C131. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Guo TL, Miller MA, Shapiro IM, Shenker BJ. Mercuric chloride induces apoptosis in human T lymphocytes: Evidence of mitochondrial dysfunction. Toxicology and Applied Pharmacology. 1998;153:250–257. doi: 10.1006/taap.1998.8549. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Livine A, Hoffmann EK. Cytoplasmic acidification and activation of Na+/H+ exchange during regulatroy volume decrease in Ehrlich ascites tumor cells. Journal of Membrane Biology. 1990;114:153–157. doi: 10.1007/BF01869096. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Gutknecht J. Inorganic mercury (Hg2+) transport through lipid bilayer membranes. Journal of Membrane Biology. 1981;61:61–66. [Google Scholar]

- 43.Jacobson MD, Weil M, Raff MC. Role of Ced-3/ ICE-family proteases in staurosporine-induced programmed cell death. Journal of Cell Biology. 1996;133:1041–1051. doi: 10.1083/jcb.133.5.1041. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Becker D, Blase C, Bereiter-Hahn J, Jendrach M. TRPV4 exhibits a functional role in cell-volume regulation. Journal of Cell Science. 2005;118:2435–2440. doi: 10.1242/jcs.02372. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Rothstein A, Mack E. Volume-activated calcium uptake: its role in cell volume regulation of Madin-Darby canine kidney cells. American Journal of Physiology. Cell Physiology. 1992;262:C339–C347. doi: 10.1152/ajpcell.1992.262.2.C339. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Charras GT, Hu CK, Coughlin M, Mitchison TJ. Reassembly of contractile actin cortex in cell blebs. Journal of Cell Biology. 2006;175:477–490. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200602085. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Charras GT, Yarrow JC, Horton MA, Mahadevan L, Mitchison TJ. Non-equilibration of hydrostatic pressure in blebbing cells. Nature. 2005;435:365–369. doi: 10.1038/nature03550. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Bonacker D, Stoiber T, Wang M, Bohm K, Prots I, Unger E, Thier R, Bolt H, Degen G. Genotoxicity of inorganic mercury salts based on disturbed microtubule function. Archives of Toxicology. 2004;78:575–583. doi: 10.1007/s00204-004-0578-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Sheetz MP, Sable JE, Dobereiner H-G. Continuous membrane-cytoskeleton adhesion requires continuous accomodation to lipid and cytoskeleton dynamics. Annual Review of Biophysics and Bimolecular Structure. 2006;35:417–434. doi: 10.1146/annurev.biophys.35.040405.102017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Ziyadeh FN, Mills JW, Kleinzeller A. Hypotonicity and cell volume regulation in shark rectal gland: role of organic osmolytes and F-actin. American Journal of Physiology. Renal Physiology. 1992;262:F468–F479. doi: 10.1152/ajprenal.1992.262.3.F468. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Zucker R, Elstein K, Easterling R, Ting-Beall H, Allis J, Massaro E. Effects of tributyltin on biomembranes: Alteration of flow cytometric parameters and inhibition of Na+, K+-ATPase two-dimensional crystallization. Toxicology and Applied Pharmacology. 1988;96:393–403. doi: 10.1016/0041-008x(88)90097-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Heinrich V, Rawicz W. Automated, high-resolution micropipet aspiration reveals new insight into the physical properties of fluid membranes. Langmuir. 2005;21:1962–1971. doi: 10.1021/la047801q. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Akinlaja J, Sachs F. The breakdown of cell membranes by electrical and mechanical stress. Biophysics Journal. 1998;75:247–254. doi: 10.1016/S0006-3495(98)77511-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Bloom M, Evans E, Mouritsen OG. Physical properties of the fluid lipid-bilayer component of cell membranes : A perspective. Quarterly Reviews of Biophysics. 1991;24:293–397. doi: 10.1017/s0033583500003735. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Venosa RA. Hypotonic stimulation of the Na+ active transport in frog skeletal muscle: Role of the cytoskeleton. Journal of Physiology. 2003;548:451–459. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2002.036830. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Guilak F, Erickson GR, Ting-Beall HP. The effects of osmotic stress on the viscoelastic and physical properties of articular chondrocytes. Biophysics Journal. 2002;82:720–727. doi: 10.1016/S0006-3495(02)75434-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Wan X, Harris JA, Morris CE. Responses of neurons to extreme osmomechanical stress. Journal of Membrane Biology. 1995;145:21–31. doi: 10.1007/BF00233304. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.