Abstract

Both human-related and natural factors can affect the establishment and distribution of exotic species. Understanding the relative role of the different factors has important scientific and applied implications. Here, we examined the relative effect of human-related and natural factors in determining the richness of exotic bird species established across Europe. Using hierarchical partitioning, which controls for covariation among factors, we show that the most important factor is the human-related community-level propagule pressure (the number of exotic species introduced), which is often not included in invasion studies due to the lack of information for this early stage in the invasion process. Another, though less important, factor was the human footprint (an index that includes human population size, land use and infrastructure). Biotic and abiotic factors of the environment were of minor importance in shaping the number of established birds when tested at a European extent using 50×50 km2 grid squares. We provide, to our knowledge, the first map of the distribution of exotic bird richness in Europe. The richest hotspot of established exotic birds is located in southeastern England, followed by areas in Belgium and The Netherlands. Community-level propagule pressure remains the major factor shaping the distribution of exotic birds also when tested for the UK separately. Thus, studies examining the patterns of establishment should aim at collecting the crucial and hard-to-find information on community-level propagule pressure or develop reliable surrogates for estimating this factor. Allowing future introductions of exotic birds into Europe should be reconsidered carefully, as the number of introduced species is basically the main factor that determines the number established.

Keywords: exotic birds, community level, introduced species, propagule pressure, human footprint, hierarchical partitioning

1. Introduction

Concerns over the invasion of exotic species worldwide and their negative impacts emphasize the need to elucidate the major factors shaping the richness and spatial variation of exotic species (Elton 1958; Blackburn & Duncan 2001; Leprieur et al. 2008). The number of established exotic species greatly varies in space (Pyšek et al. 2008). Many factors have been examined in an attempt to explain this spatial variation (Sakai et al. 2001; Duncan et al. 2003). Initially, most of the work focused on the natural biotic and abiotic characteristics of the invaded ecosystem (e.g. Elton 1958; Shea & Chesson 2002; Levine et al. 2004; Evans et al. 2005) as well as traits of successful invaders (e.g. Sol et al. 2005; Jeschke & Strayer 2006). More recently, human activity was suggested as an important factor shaping exotic species richness at large spatial scales (Taylor & Irwin 2004; Leprieur et al. 2008). As far as we are aware, there have been no studies examining these factors together at a regional, continental or global scale.

In Europe, humans have been affecting the environment for thousands of years (e.g. Blondel & Aronson 1999), generating large spatial variation in human impacts on the environment (Sanderson et al. 2002). Thus, including human-related factors, such as land use, and separating their effect from natural factors is of major importance in our understanding of the spatial distribution of exotic species richness. Here, we examine the relative importance of the major natural and human-related factors known to shape variation in exotic bird richness over space in one framework that separates two main components of human effect: the number of bird species introduced into a region and the human footprint.

Human activity can affect invasion success in many ways and at different stages of the invasion process, from introduction to invasion. For example, human activity can affect the establishment stage by altering the environment (Byers 2002). Many exotic species establish in highly modified habitats (McKinney 2006). In addition, human activity can shape the early stage of introduction, where humans determine the number of species introduced into a region (sometimes termed community-level propagule pressure; Blackburn et al. 2008) and the number of introduction attempts and/or number of individuals of each species introduced (often termed population-level introduction effort; Cassey et al. 2005). Introduction effort at the population level has received much interest recently, supporting the hypothesis that this factor plays an important role in determining the establishment success of species (Lockwood et al. 2005). However, due to lack of information and the difficulty in measuring the number of species introduced for a large spectrum of species and at wide spatial extents, the importance of propagule pressure at the community level usually remains unknown (Richardson & Pyšek 2008), although it has been shown to be important on islands (Blackburn et al. 2008). Several surrogates that approximate community-level propagule pressure have been proposed over the years, such as human density or population size (Taylor & Irwin 2004), economic indices (Leprieur et al. 2008) and the number of countries where a species was introduced (Jeschke & Strayer 2006). Unfortunately, most of these proxies are also proxies for human modification of the environment that can affect the establishment stages (Byers 2002), so that identifying the major human factors that affect exotic richness remains challenging (Richardson & Pyšek 2008).

Here, we hypothesized that the number of exotic species introduced and the human footprint will positively affect the number of species established. We conducted a continental analysis for Europe and provide, to our knowledge, the first map of exotic bird richness across the whole of Europe. We use hierarchical partitioning, a statistical method that calculates the relative contribution of each factor to the total explained deviance in the number of species established. This method is especially useful when factors covary.

2. Material and methods

(a) Bird database and mapping

We compiled lists of introduced and established exotic birds and introduction events in Europe using the database that we generated in the framework of the Delivering Alien Invasive Species Inventories for Europe research consortium (DAISIE 2008). The database was derived from information in books, journal articles, grey literature, reports at a country or regional scale, published and unpublished bird atlas projects, bird guides and bird checklists for countries (222 bibliographic sources in total, list available upon request). This extensive database was peer reviewed and verified by national experts (Kark et al. 2008). We recorded location, year of introduction and the occurrence in the year 2000 at the most detailed scale reported. We did not include in our analysis the most recent introductions after 2000 since the result of the establishment is not yet clear. We considered bird introductions as successful if they resulted in the establishment of self-reproducing breeding populations by the year 2000 and unsuccessful in the case of non-breeding or extinct exotic species (DAISIE 2008). Species native to Europe that were introduced to other European regions where they are non-native were considered exotic in the new region. Species with unknown locations or unclear introduction histories were omitted from the analyses. We restricted our analysis to introductions starting from the year 1500 AD (following DAISIE 2008). We included all European countries and their European islands (including the Azores, Canaries and Madeira), except Albania and Croatia due to the lack of verified data on bird introductions. European Russia and Turkey were not included in our analysis. We used the geographic information system ArcGIS 9.2 to assign the locations of all introductions using 50×50 km2 grid squares. This scale was also used by the European Breeding Census Council Atlas (Hagemeijer & Blair 1997).

(b) Human-related and natural variables

The continuous variables included human-related variables and natural variables. The human-related variables included community-level propagule pressure (i.e. the number of exotic bird species introduced, following Blackburn et al. 2008) and human footprint, an integrated measure of human-related habitat disturbance. The human footprint is an index that includes human population density, human land use and infrastructure, and human access (Sanderson et al. 2002). The natural variables included native bird richness, two measures of available energy (McCann 1998; Evans et al. 2005), habitat diversity (Melbourne et al. 2007) and inter- versus intra-European species origin (Blackburn & Duncan 2001). Native bird species richness was derived from the EBCC atlas and database (Hagemeijer & Blair 1997). We estimated available energy using the normalized difference vegetation index, a surrogate of plant productivity (Kerr & Ostrovsky 2003) and used the minimum temperature (°C) averaged over the season of bird reproduction (April–July spanning from 1950 to 1990; Hijmans et al. 2005) as a measure of solar energy. The Land Cover database provided the number of different habitat types in each grid square (n=9; USGS EROS 2008). The species origin indicates whether the introduction was intraregional (introduction site and native range were in Europe) or interregional (native range was from outside of Europe), defining European and non-European exotic species, respectively.

Because most variables were defined at finer resolutions than the 50×50 km2 scale, we scaled up information by averaging the values of variables at the grid square level across Europe. In addition to the seven continuous variables, two categorical variables were analysed, which included (i) whether the location was on the mainland or an island and (ii) the country.

(c) Hierarchical partitioning and multivariate analysis

Because most of the factors showed multicollinearity, we used hierarchical partitioning (Chevan & Sutherland 1991). This method provides explanatory power (R-value) for each of the factors, and the contribution of each factor to the total explained deviance of the model, both independently and in conjunction with the other variables (McNally 2002). The R-value of each factor is independent, which means it is corrected for the joint contributions of the other factors on the variable tested, and is expressed as the percentage of the total independent deviance explained (Leprieur et al. 2008). We calculated the statistical significance of each factor as a pseudo Z-score using 1000 randomizations (McNally 2002). Hierarchical partitioning only provides explanatory power, as opposed to standard regression, which gives information on the form of the relationship between the independent and the dependent variables. Therefore, following Leprieur et al. (2008), we also modelled the relationship between exotic bird richness and each environmental factor at the 50×50 km2 scale. Spatial autocorrelation, if present, can confound relationships between species richness and environmental factors, especially when the analysis is done at a below-country spatial resolution (Sol et al. 2008). To overcome this potential problem, we used spatial models that allow for the specification of the spatial correlation structure as a function of the distance matrix between grid squares. These included a spatial generalized least-squares model (GLS; Pinhero & Bates 2000) accounting for spatial autocorrelation (table 1). We compared the results of the spatial model with those of a standard multiple regression that assumes spatial independency (table 1). We then used the Akaike information criterion (AIC; Burnham & Anderson 2002) to examine whether the spatial model is more parsimonious than the regression model (table 1).

Table 1.

Details on the multiple regression model versus the spatial GLS used in this paper. (AIC is the Akaike information criterion.)

| the GLS model | model assumptions | model error structure | error correlation distribution | goodness of fit | model selection |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| regression model | spatial independence | GLS without specification of error spatial structure | Gaussian | maximum log-likelihood | lowest AIC value (ΔAIC>2) |

| spatial model | spatial dependence | GLS with specification of error spatial structure | linear, exponential, Gaussian or spherical | maximum log-likelihood | lowest AIC value (ΔAIC>2) |

In order to determine the direction and significance of the correlation, for each variable, we calculated the residuals deriving from a multivariate analysis examining the relationship between exotic richness and all other variables. We then examined the relationship between these residuals and the variable of interest. To test the slope of the relationship in the GLS, we used the t-statistic when model residuals were normally distributed. Following Leprieur et al. (2008), for the non-spatial models, we used the Pearson or the Spearman rank correlation when model residuals were normally or non-normally distributed, respectively. We used the R statistical software version 2.6.1 (R Development Core Team 2004) for all analyses.

3. Results

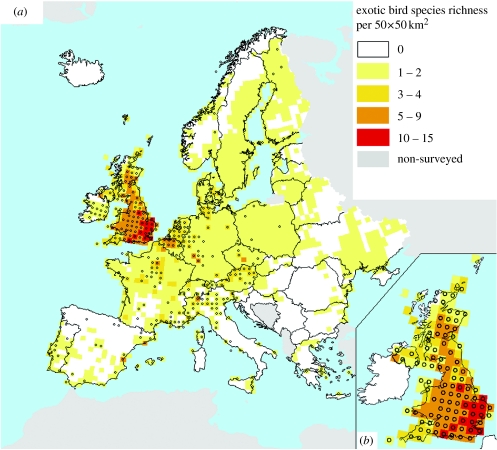

Overall, we recorded the introduction of 175 exotic bird species in Europe between the years 1500 and 2000 AD. Of these, 75 species (43%) were established in Europe in the year 2000 (figure 1a) where 59 per cent of the continent had at least one known established exotic bird species at the 50×50 km2 spatial scale (figure 1a). The highest richness of exotic birds in Europe was found in southeastern England, followed by areas in Belgium and The Netherlands (figure 1). In southeastern England, there was a maximum of 15 exotic bird species per 50×50 km2 square, reaching 12 per cent of the richness of the native breeding birds. In eastern and southeastern Europe, the richness of established birds was significantly lower (between 0 and 2 species per grid square; figure 1a). This result could partly be attributed to lower sampling and reporting efforts and/or less available data in the eastern parts of Europe in the nineteenth and the twentieth centuries.

Figure 1.

Distribution of exotic bird richness in (a) the whole of Europe and (b) the UK at a 50×50 km2 grid square resolution. Verified introductions included in the analyses are marked with open circles.

The results of the hierarchical partitioning suggest that, of the continuous variables estimated at a scale of 50×50 km2, the most important was community-level propagule pressure, followed by the human footprint (table 2). These two human-related variables together explain 37 per cent of the total deviance and are both positively and significantly correlated with exotic richness (table 2). Native bird richness, although having a significant effect, explained only one per cent of the total deviance. All other continuous variables together explained four per cent of the deviance. The two categorical variables that were used to control for larger scale effects, including island/mainland location and country, explained an important part (59%) of the deviance (table 2). We used the standard regression model, as it performed better than the spatial regression model when analysed for the whole of Europe (ΔAIC>2 in all cases; table 1).

Table 2.

The proportion of the deviance in exotic bird species richness explained by each of the variables estimated at a 50×50 km2 grid square (n=1497 squares for Europe and n=124 squares for the UK). The direction of the relationship is marked with plus/minus and statistical significance (p≤0.05) based on 95% CI (Z-scores>1.65) is marked with asterisks. Variables were ranked according to the proportion of the total deviance explained.

| proportion of the deviance explained | direction and significance (p-value) | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| variables | Europe | UK | Europe | UK |

| continuous variables | ||||

| community-level propagule pressure | 28.8* | 45.4* | +(<0.001) | +(0.048) |

| human disturbance | 7.8* | 19.8* | +(<0.001) | +(0.040) |

| native bird richness | 1.1* | 22.2* | +(0.246) | +(<0.001) |

| minimum temperature | 0.5* | 8.8* | +(0.034) | −(0.784) |

| plant productivity | 2.4* | 1.52 | +(0.016) | −(0.090) |

| habitat diversity | 0.2 | 2.2 | −(0.624) | −(0.005) |

| discrete variables | ||||

| country | 44.4* | — | — | — |

| mainland versus island | 14.7* | — | — | — |

| total deviance | 100% | 100% | — | — |

We found using contingency table analysis that the proportion of species successfully established in Europe that originated from other parts of Europe was higher than those originating from other continents, though this result was only marginally significant (Χ12=2.81, p=0.09). Of the 39 species of European origin introduced into Europe (22% of the exotic bird species), 25 successfully established in Europe. These comprised 33 per cent of all exotic bird species established in the study area.

Because the UK was the richest hotspot of exotic birds in Europe and had large spatial variation in most variables and in exotic bird richness, we ran a hierarchical partitioning model for the UK alone using the same methods. This also enabled us to test whether the results at the European-wide scale held when we analysed the data for a single country that received a high sampling effort compared with many other parts of Europe (Hagemeijer & Blair 1997). The spatial model performed better for the UK. Therefore, we used it for all the UK analyses. We found that for the UK alone, in agreement with the analysis at the European scale, community-level propagule pressure was the most important predictor of exotic richness, explaining 45 per cent of the total deviance (table 2). Human footprint was also an important predictor (20%). In contrast to the analysis at the continental scale, in the UK, native bird richness was an important predictor of established exotic bird richness, explaining 22 per cent of the deviance. The relationship was positive and significant after controlling for spatial autocorrelation using the spatial model. Although minimum temperature was also more important at this extent than for the whole of Europe (table 2), it did not explain a major part of the total deviance in exotic species richness at the 50×50 km2 spatial scale (table 2).

4. Discussion

Hypotheses explaining the establishment success of exotic species have ranged from those related to biotic factors in the ecosystem invaded (e.g. the biotic resistance, the biotic acceptance and the enemy-release hypotheses; Elton 1958; Colautti et al. 2004; Levine et al. 2004; Fridley et al. 2007), traits of the invaders (e.g. behavioural innovation; Sol et al. 2008), to hypotheses dealing with the abiotic characteristics of the environment (e.g. the climate-matching hypothesis; Duncan et al. 2001). Recently, human activity has been found to be an important factor shaping establishment success (Taylor & Irwin 2004; Leprieur et al. 2008). However, in most studies, community-level propagule pressure was not directly estimated or separated from other human activity effects (but see Blackburn et al. (2008) for islands). The results of our study suggest that the relative role of community-level propagule pressure is a major factor in shaping the species richness of exotic bird communities. While this is not surprising, it suggests that quantifying community-level propagule pressure using surrogates of human activity such as population size and the gross domestic product may be insufficient for explaining the invasion process. Although such proxies of human activity can be useful, they affect both the introduction and the establishment stages and do not enable an examination of their separate roles. The use of community-level propagule pressure enables us to separate the effects at the introduction stages from those at the establishment stage, to include the effect of species that failed to establish (Blackburn et al. 2008), and thus to better understand the mechanisms shaping biological invasions. Blackburn et al. (2008) recently compared the effect of community-level propagule pressure, human population size and island isolation on the establishment of birds in 35 islands around the world. The factor that best explained the establishment patterns was the number of exotic species introduced to each island. Our results provide evidence that this effect is a major factor not only on islands, but also on continents and at large scales. In addition, the results are robust when we control for other potential factors, enabling us to show the relative contribution of the major human-related factors.

Previous studies have shown the importance of what is sometimes termed human disturbance (e.g. Leprieur et al. 2008) in shaping the number of exotic species. Here, the use of hierarchical partitioning shows that although the human footprint does not explain as much of the deviance as propagule pressure at both the European and UK scales, it remains an important factor even after controlling for more natural characteristics of the environment (e.g. native richness and climatic factors) and propagule pressure. While exotic bird species are more often released in human-disturbed areas (Kark et al. 2008) and therefore establish there, this result suggests that human modification of the environment alone is probably an important factor in shaping the establishment process. We chose to use the human footprint index as it includes multiple factors related to human disturbance (e.g. human population size, land use, infrastructure and the degree of human access). These human effects modify and generate new environments that are favourable for exotic species, many of which are human commensals (McKinney 2006). In birds, this often includes exotic species that succeed in urban environments (e.g. the feral rock dove), agricultural environments (e.g. Egyptian goose) or in both (e.g. the rose-ringed parakeet). In our case, because the data on the native bird richness were available at a 50×50 km2 resolution (Hagemeijer & Blair 1997), and data for some parts of Europe are not available at more detailed resolutions, we analysed the factors at this scale. It would be interesting to examine whether our results at a European scale would be similar at a more detailed resolution (e.g. Chytrý et al. 2008). Currently, this can only be done on a small subset of species for which very detailed local spatial information exists.

Country, as expected, was a major factor explaining the spatial variation in the number of exotic species established, even after controlling for the biotic and abiotic factors. This variation among countries can result from several factors, such as differences between countries in historical, cultural, socio-economic factors, legislation and data collection or reporting (Jenkins 1999; Duncan et al. 2006; Pyšek et al. 2008). Because we found few established exotic birds in many parts of eastern Europe, while most hotspots occurred in the west, the analysis was also performed at the UK scale alone, where potential bias due to reporting is expected to be less substantial. Although the goal of this study was not to compare the effects at multiple spatial extents, but rather to test the factors at a continental European scale, the analysis performed for the UK alone shows an interesting resemblance to and differences from that done for the whole of Europe. First, the major finding that community-level propagule pressure is the most important factor in determining the richness of exotic species in the UK mirrors the results for the whole of Europe. Human footprint is also important at the UK scale. However, unlike the European scale, we find that, for the UK alone, native bird richness is an important predictor of exotic richness even after controlling for the other factors. This supports other studies, in which positive relationships have been found at regional scales (Fridley et al. 2007), while at more detailed scales the relationship becomes less positive and sometimes even negative (Kennedy et al. 2002).

Our results provide support for the human-activity hypothesis and especially for what can be termed the ‘community-level propagule pressure’ hypothesis. For the UK, they also support the biotic acceptance hypothesis (Fridley et al. 2007). They do not support the biotic resistance hypothesis. Because the establishment of exotic species in Europe is not only a historical process but is also ongoing today, the fact that propagule pressure is a crucial factor suggests that management actions should be directed to prevent future introduction in both species-rich and species-poor environments. A recent study of exotic fish establishment at the global scale (Leprieur et al. 2008) found that human-related factors are more important than natural factors. It is interesting to note that the importance of human factors dominates in two such different ecosystems and taxa, which may hint at a more general pattern. Because birds are one of the few groups for which reasonable quantitative data on the earliest stages of transport and release exist, more theoretical and applied work should be devoted to developing and testing reliable proxies for estimating propagule pressure when data on the early stages of introduction are incomplete (Richardson & Pyšek 2008).

While some countries around the world invest large amounts of resources at preventing current introductions of exotic species, there is little regulation of the passage of exotic species among the countries of the European Union under free trade rules. We encourage further studies to identify the causes of the variation of exotic richness at the country scale to help structure better management policies (Jenkins 1999). Regulation of trade at both the within-country scale and coordinated at the whole European scale will be required to control the introduction of alien species at European borders and their flow among countries. Because a very high proportion of bird species introduced into Europe have managed to successfully establish breeding populations (see also Jeschke & Strayer 2005), allowing future introductions of exotic birds into Europe should be reconsidered carefully.

Acknowledgments

This study was supported by the European Commission's Sixth Framework Programme project DAISIE (contract SSPI-CT-2003-511202). We thank the members of DAISIE for their collaboration and Nicola Bacetti, Eran Banker, Daniel Bergmann, Birdlife Belgium, Michael Braun, Jordi Clavell, Philippe Clergeau, Helder Costa, Anita Gamauf, Piero Genovesi, Ohad Hatzofe, Jelena Kralj, Anton Kristin, Teemu Lehtiniemi, Michael Miltiadous, Gert Ottens, Milan Paunovic, Riccardo Scalera, Ondrej Sedláček, Cagan Sekercioglu, Assaf Shwartz, Wojciech Solarz, Diederik Strubbe, Alexandre Vintchevski, Wim Van den Bossche and Georg Willi for providing and/or verifying local information on birds. We are most thankful to the European Bird Census Council and especially to Richard Gregory for providing us with the digital data of the EBCC Atlas of European Breeding Birds.

References

- Blackburn T.M, Duncan R.P. Determinants of establishment success in introduced birds. Nature. 2001;414:195–197. doi: 10.1038/35102557. doi:10.1038/35102557 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blackburn T.M, Cassey P, Lockwood J.L. The island biogeography of exotic bird species. Global Ecol. Biogeogr. 2008;17:246–251. doi:10.1111/j.1466-8238.2007.00361.x [Google Scholar]

- Blondel J, Aronson J. Oxford University Press; New York, NY: 1999. Biology and wildlife of the Mediterranean region. [Google Scholar]

- Burnham K.P, Anderson D.R. Springer; New York, NY: 2002. Model selection and multi-model inference: a practical information–theoretic approach. [Google Scholar]

- Byers J.E. Impact of non-indigenous species on natives enhanced by anthropogenic alteration of selection regimes. Oikos. 2002;97:449–458. doi:10.1034/j.1600-0706.2002.970316.x [Google Scholar]

- Cassey P, Blackburn T.M, Duncan R.P, Lockwood J.L. Lessons from the establishment of exotic species: a meta-analytical case study using birds. J. Anim. Ecol. 2005;74:250–258. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2656.2005.00918.x [Google Scholar]

- Chevan A, Sutherland M. Hierarchical partitioning. Am. Stat. 1991;45:90–96. doi:10.2307/2684366 [Google Scholar]

- Chytrý M, Pyšek P, Jarošík V, Hájek O, Knollová I, Tichý L.R, Danihelka J. Separating habitat invasibility by alien plants from the actual level of invasion. Ecology. 2008;89:1541–1553. doi: 10.1890/07-0682.1. doi:10.1890/07-0682.1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Colautti R.I, Ricciardi A, Grigorovich A, MacIsaac H.J. Is invasion success explained by the enemy release hypothesis? Ecol. Lett. 2004;7:721–733. doi:10.1111/j.1461-0248.2004.00616.x [Google Scholar]

- DAISIE. Springer; Dordrecht, The Netherlands: 2008. Handbook of alien species in Europe. [Google Scholar]

- Duncan R.P, Bomford M, Forsyth D.M, Conibear L. High predictability in introduction outcomes and the geographical range size of introduced Australian birds: a role for climate. J. Anim. Ecol. 2001;70:621–632. doi:10.1046/j.1365-2656.2001.00517.x [Google Scholar]

- Duncan R.P, Blackburn T.M, Sol D. The ecology of bird introductions. Annu. Rev. Ecol. Evol. Syst. 2003;34:71–98. doi:10.1146/annurev.ecolsys.34.011802.132353 [Google Scholar]

- Duncan R.P, Blackburn T.M, Cassey P. Factors affecting the release, establishment and spread of introduced birds in New Zealand. In: Allen R, Lee W, editors. Biological invasions in New Zealand. vol. 186. Springer; Berlin, Germany: 2006. pp. 137–154. [Google Scholar]

- Elton C. Methuen; London, UK: 1958. The ecology of invasions by animals and plants. [Google Scholar]

- Evans K, Warren P.H, Gaston K.J. Does energy availability influence classical patterns of spatial variation in exotic species richness? Global Ecol. Biogeogr. 2005;14:57–65. doi:10.1111/j.1466-822X.2004.00134.x [Google Scholar]

- Fridley D.J, Stachowicz J, Naeem S, Sax D.F, Seabloom E.W, Smith M.D, Stohlgren T.J, Tilman D, Von Holle B. The invasion paradox: reconciling pattern and process in species invasions. Ecology. 2007;88:3–17. doi: 10.1890/0012-9658(2007)88[3:tiprpa]2.0.co;2. doi:10.1890/0012-9658(2007)88[3:TIPRPA]2.0.CO;2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hagemeijer E.J.M, Blair M.J. T. & A. D. Poyser; London, UK: 1997. The EBCC Atlas of European breeding birds: their distribution and abundance. [Google Scholar]

- Hijmans R.J, Cameron S, Parra L, Jones P.G, Jarvis A. Very high resolution interpolated climate surfaces for global land areas. Int. J. Climatol. 2005;25:1965–1978. doi:10.1002/joc.1276 [Google Scholar]

- Jenkins P.T. Trade and exotic species introductions. In: Sandlund O.T, Schei P.J, Viken Å, editors. Invasive species and biodiversity management. Kluwer Academic Publishers; Dordrecht, The Netherlands: 1999. pp. 229–235. [Google Scholar]

- Jeschke J.M, Strayer D.L. Invasion success of vertebrates in Europe and North America. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA. 2005;102:7198–7202. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0501271102. doi:10.1073/pnas.0501271102 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jeschke J.M, Strayer D.L. Determinants of vertebrate invasion success in Europe and North America. Glob. Change Biol. 2006;12:1608–1619. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2486.2006.01213.x [Google Scholar]

- Kark S, Solarz W, Chiron F, Clergeau P, Shirley S. Alien birds, amphibians and reptiles of Europe. In: DAISIE, editor. Handbook of alien species in Europe. Springer; Dordrecht, The Netherlands: 2008. pp. 105–118. [Google Scholar]

- Kennedy T.A, Naeem S, Howe K.M, Knops J.M.H, Tilman D. Biodiversity as a barrier to ecological invasion. Nature. 2002;417:636–638. doi: 10.1038/nature00776. doi:10.1038/nature00776 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kerr J.T, Ostrovsky M. From space to species, ecological applications for remote sensing. Trends Ecol. Evol. 2003;18:299–305. doi:10.1016/S0169-5347(03)00071-5 [Google Scholar]

- Leprieur F, Beauchard O, Blanchet O, Oberdorff T, Brosse S. Fish invasions in the world's river systems: when natural processes are blurred by human activities. PLoS Biol. 2008;6:404–410. doi: 10.1371/journal.pbio.0060028. doi:10.1371/journal.pbio.0060028 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Levine J, Adler P, Yelenik S. A meta-analysis of biotic resistance to exotic plant invasions. Ecol. Lett. 2004;10:975–989. doi:10.1111/j.1461-0248.2004.00657.x [Google Scholar]

- Lockwood J.L, Cassey P, Blackburn T.M. The role of propagule pressure in explaining species invasions. Trends Ecol. Evol. 2005;20:223–228. doi: 10.1016/j.tree.2005.02.004. doi:10.1016/j.tree.2005.02.004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McCann K, Hastings A, Huxel G.R. Weak trophic interactions and the balance of nature. Nature. 1998;395:794–798. doi:10.1038/27427 [Google Scholar]

- McKinney M.L. Urbanization as a major cause of biotic homogenization. Biol. Conserv. 2006;127:247–260. doi:10.1016/j.biocon.2005.09.005 [Google Scholar]

- McNally R. Multiple regression and inference in ecology and conservation biology: further comments on identifying important predictor variables. Biodivers. Conserv. 2002;11:1397–1401. doi:10.1023/A:1016250716679 [Google Scholar]

- Melbourne B.A, et al. Invasion in a heterogeneous world: resistance, coexistence or hostile takeover? Ecol. Lett. 2007;10:77–94. doi: 10.1111/j.1461-0248.2006.00987.x. doi:10.1111/j.1461-0248.2006.00987.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pinhero J.C, Bates D.M. Springer; New York, NY: 2000. Mixed-effects models in S and S-PLUS. [Google Scholar]

- Pyšek P, Richardson D.M, Pergl J, Jarošík V, Sixtová Z, Weber E. Geographical and taxonomic biases in invasion ecology. Trends Ecol. Evol. 2008;23:237–244. doi: 10.1016/j.tree.2008.02.002. doi:10.1016/j.tree.2008.02.002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- R Development Core Team 2004 R: a language and environment for statistical computing, v. 2.6.1. Vienna, Austria: R Foundation for Statistical Computing.

- Richardson D.M, Pyšek P. Fifty years of invasion ecology: the legacy of Charles Elton. Divers. Distrib. 2008;14:161–168. doi:10.1111/j.1472-4642.2007.00464.x [Google Scholar]

- Sakai A.K, et al. The population biology of invasive species. Annu. Rev. Ecol. Syst. 2001;32:305–332. doi:10.1146/annurev.ecolsys.32.081501.114037 [Google Scholar]

- Sanderson E.W, Malanding J, Levy M.A, Redford K.H, Wannebo A.W, Woolmer G. The human footprint and the last of the wild. Bioscience. 2002;52:891–903. doi:10.1641/0006-3568(2002)052[0891:THFATL]2.0.CO;2 [Google Scholar]

- Shea K, Chesson P. Community ecology theory as a framework for biological invasions. Trends Ecol. Evol. 2002;17:170–176. doi:10.1016/S0169-5347(02)02495-3 [Google Scholar]

- Sol D, Duncan R.P, Blackburn T.M, Cassey P, Lefebvre L. Big brains, enhanced cognition, and response of birds to novel environments. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA. 2005;102:5460–5465. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0408145102. doi:10.1073/pnas.0408145102 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sol D, Vilà M, Kühn I. The comparative analysis of historical alien introductions. Biol. Inv. 2008;10:1119–1129. doi:10.1007/s10530-007-9189-7 [Google Scholar]

- Taylor B.W, Irwin R.E. Linking economic activities to the distribution of exotic plants. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA. 2004;101:17 725–17 730. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0405176101. doi:10.1073/pnas.0405176101 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- USGS Earth Resources Observation and Science Center (EROS) 2008 Global Land Use/Land Cover (LANDCOV). See http://edc.usgs.gov/