Abstract

It is commonly believed that T cells have difficulty reaching tumors located in the brain due to the presumed “immune privilege” of the central nervous system (CNS). Therefore, we studied the biodistribution and anti-tumor activity of adoptively transferred T cells specific for an endogenous tumor-associated antigen (TAA), gp100, expressed by tumors implanted in the brain. Mice with pre-established intracranial (i.c.) tumors underwent total body irradiation (TBI) to induce transient lymphopenia, followed by the adoptive transfer of gp10025–33-specific CD8+ T cells (Pmel-1). Pmel-1 cells were transduced to express the bioluminescent imaging (BLI) gene luciferase. Following adoptive transfer, recipient mice were vaccinated with hgp10025–33 peptide-pulsed dendritic cells (hgp10025–33/DC) and systemic interleukin 2 (IL-2). This treatment regimen resulted in significant reduction in tumor size and extended survival. Imaging of T cell trafficking demonstrated early accumulation of transduced T cells in lymph nodes draining the hgp10025–33/DC vaccination sites, the spleen and the cervical lymph nodes draining the CNS tumor. Subsequently, transduced T cells accumulated in the bone marrow and brain tumor. BLI could also detect significant differences in the expansion of gp100-specific CD8+ T cells in the treatment group compared with mice that did not receive either DC vaccination or IL-2. These differences in BLI correlated with the differences seen both in survival and tumor infiltrating lymphocytes (TIL). These studies demonstrate that peripheral tolerance to endogenous TAA can be overcome to treat tumors in the brain and suggest a novel trafficking paradigm for the homing of tumor-specific T cells that target CNS tumors.

Electronic supplementary material

The online version of this article (doi:10.1007/s00262-008-0461-1) contains supplementary material, which is available to authorized users.

Keywords: Brain tumor, Immunotherapy, T cell trafficking, Dendritic cells

Introduction

Malignant tumors that develop within the confines of the “immune privileged” CNS present clinicians with few treatment options. Immunotherapy is theoretically appealing because it offers the potential for a high degree of tumor-specificity, while sparing normal brain structures [37, 49]. Several different laboratories have demonstrated that effective immune responses within the CNS can be generated through the use of gene-modified tumor cell vaccines, the adoptive transfer of immune T cells, or the use of dendritic cells (DC)-based vaccines [37]. These results imply that systemic immunity can safely enter the “immunologically privileged” CNS, selectively identify tumor-associated antigens, and destroy brain tumor cells. However, little is known about the migration patterns of tumor-specific T cells when targeting CNS tumors.

Adoptive transfer of tumor antigen-specific T cells has resulted in the highest response rates reported in patients with metastatic melanoma, including isolated metastases to the brain [9, 10]. Pre-clinically, the Pmel-1 TCR transgenic murine tumor model recapitulates many features of the clinical experience and is particularly suitable, because the TCR transgenic T cells are specific for a self-antigen, as opposed to a strong xenoantigen. Pmel-1 T cells bear a transgenic TCR that recognizes the gp10025–33 H-2Db-restricted epitope of the melanoma tumor antigen gp100, which is expressed by murine B16 melanomas [31] and GL261 gliomas [38]. Adoptive transfer of Pmel-1 CD8+ T cells alone into lymphodepleted C57BL/6 mice has no impact on the growth of established subcutaneous B16 tumors. Regression of established B16 occurs only when the adoptive transfer is complemented by vaccination with recombinant viral vectors expressing human gp100 or syngeneic DC pulsed with the human gp10025–33 (hgp10025–33) peptide, followed by systemic administration of high doses of IL-2 or IL-15 as sources of helper cytokines [1, 14, 15, 31, 32, 51].

Recent advances in sensitive in vivo imaging technologies now permit the serial, non-invasive visualization of T cell responses in murine models without disrupting the physiological process. PET and bioluminescent imaging have emerged recently as new strategies to longitudinally visualize the in vivo distribution and tumor targeting of immune cells transduced to express reporter genes. Our group and others have demonstrated the feasibility of both BLI and micro PET-based in vivo imaging approaches to monitor anti-tumor immunity [2, 8, 11, 23–25, 33, 40, 46–48]. In this study, we adapted BLI to allow us to test our hypothesis that T cells specific for endogenous melanoma antigens can localize into brain tumors and exert an anti-tumor effect. Although it has been previously demonstrated that T cells can target brain tumors [12, 16, 18–20, 26, 27, 29, 30, 34, 38, 39, 44, 45, 50, 52–54], little is known about the trafficking of T cells that are specific for endogenous TAA to these sites. Furthermore, the accumulation of lymphoid cells within the cervical lymph nodes has been associated with CNS immunity [7, 13, 22, 30, 45]; however, our studies have extended these data by defining an in vivo trafficking pattern of tumor-specific T cells targeting brain tumors. These studies provide direct evidence that T cells can attack endogenous TAA on brain tumors in syngeneic, immunocompetent mice, in large part due to our ability to serially monitor the trafficking of self-tumor antigen-specific CD8+ T cells.

Materials and methods

Animals and cell lines

Breeding pairs of Pmel-1 TCR transgenic mice were a kind gift from Dr. Nicholas Restifo (Surgery Branch, National Cancer Institute). All mice were bred and kept under defined-flora pathogen-free conditions at the AALAC-approved Animal Facility of the Division of Experimental Radiation Oncology at UCLA. Mice were handled in accordance with the UCLA animal care policy and approved animal protocols. The B16 murine melanoma cell line was obtained from the ATCC (Rockville, MD, USA) and maintained in DMEM with 10% fetal calf serum (FCS, Gemini Products, Calabasas, CA, USA), 1% (all percentages represent v/v) penicillin, streptomycin. B16 cells stably expressing firefly luciferase (B16-Fluc) were created as described elsewhere [6].

Bone marrow-derived DC

The development of DC from murine bone marrow (BM) progenitor cells was performed as previously published [38, 39, 42, 43]. BM cells were cultured overnight in RPMI 1640 (Life Technologies, Gaithersburg, MD, USA) with 10% FCS, 1% penicillin, streptomycin, and amphotericin (Complete medium, CM) in a Petri dish. Nonadherent cells were replated on day 1 at 2–3 × 106 cells/well in 24-well plates with murine interleukin-4 (IL4 500 U/ml, R&D Systems, Minneapolis, MN, USA) and murine granulocyte-macrophage colony stimulating factor (GM-CSF 100 ng/ml, Amgen, Thousand Oaks, CA, USA). On day 4, 80–90% of the media was removed and adherent cells were re-fed with an addition of 1 ml per well of CM plus cytokines. DC were harvested as the loosely adherent cells from the day-8 cultures. DC were resuspended at 2-5 × 106 cells/ml in serum-free RPMI and pulsed with human gp10025–33 peptide at a concentration of 10 μM in serum-free media for 90 min at room temperature. After three washes in PBS, hgp10025–33 peptide pulsed DC (hgp10025–33/DC) were immediately prepared for injection in 0.2 ml of PBS per mouse. Injections were given s.c. at four sites on the back.

Retrovirus production

The retroviral vector pMSCV [17], containing a 5′LTR-driven thermostable variant of firefly luciferase (tsFL [41]) fused with super enhanced yellow fluorescent protein (seYFP), was used to generate high-titer helper-free retrovirus stocks prepared by transient cotransfection of 293T cells.

In vitro activation of Pmel-1 T cells and retroviral transduction

Lymph nodes and/or spleens were harvested from Pmel-1 mice and cultured with human IL-2 (100 U/ml, Novartis Institute for Biomedical Research, Emeryville, CA, USA), IL-15 (10 ng/ml, Amgen), and hgp10025–33 peptide (1 μg/ml, Biosynthesis, Inc., Lewisville, TX, USA). After 48 h and 72 h, the cells were infected with MSCV-tsFL-YFP retrovirus [∼10 multiplicity of infection (MOI)] and 2 μg/ml of lipofectamine under spin conditions (1,800 rpm, 120 min, 32°C, Beckman CS-6R centrifuge) and then incubated overnight at 37°C. Cell lysates were prepared and in vitro luciferase activity(relative light units) was assessed with a luminometer after the addition of the d-luciferin substrate.

Smaller, parallel cultures were also infected with MSC-sr39tk-YFP retrovirus (∼10 MOI) to estimate infection efficiency by FACS (see Supplementary Figure 1B).

Adoptive transfer, vaccination, and tumor treatment

C57BL/6 mice (6–12 weeks of age) were implanted in the brain with either 1 × 103 B16 melanoma cells or 1 × 104 syngeneic GL261 glioma cells on day-8. Prior to tumor inoculation, B16 cells or GL261 cells were grown in supplemented DMEM, trypsinzed with 0.05% Trypsin-EDTA (Gibco, Gaithersburg, MD, USA), live cells enumerated using a hemacytometer with trypan blue exclusion, and then washed three times in Dulbecco’s phosphate-buffered saline (dPBS, Gibco). For the i.c. implantation of tumor cells, animals were first anesthetized with ketamine/xylazine. The head was shaved and the skull exposed. Thereafter, the animal was positioned into a stereotactic frame (David Kopf) with small animal earbars. A burr hole was made using a Dremel drill approximately 1.5 mm lateral and 1 mm posterior from the intersection of the coronal and sagittal sutures (bregma). Cells were injected using a Hamilton syringe at a depth of 3 mm in a volume of 2 μl. One day prior to Pmel-1 adoptive transfer (day-1), lymphopenia was induced by a nonmyeloablative dose (500 cGy) of TBI. On the next day (day 0), groups of mice were randomized into two groups: one receiving adoptive transfer of 2–5 × 106 transduced pmel-1 cells alone and another group that received Pmel-1 cells plus hgp10025–33-peptide pulsed DC and human IL-2 [(Novartis), 5 × 105 IU i.p. for 3 days after each DC administration]. In some survival studies, i.c. tumor progression was estimated by BLI of i.c. B16-Fluc tumors, as previously demonstrated [34, 35].

FACS analysis of adoptively transferred cells

Spleens, cervical lymph nodes, bone marrow and CNS tumor infiltrating lymphocytes (TIL) were harvested from CNS tumor-bearing mice that received either Pmel-1 AT or Pmel-1 AT followed by hgp10025–33/DC and systemic IL-2. CNS tumors were dissected from the brains of treated mice, weighed, minced and subsequently incubated at 37° for 1–2 h in media containing DNase (0.1 mg/ml, Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO), collagenase D (1 mg/ml, Roche Applied Sciences, Indianapolis, IN). Single-ell suspensions were prepared in PBS by filtering through a mesh cell strainer. Red blood cells were lysed with 1× PharmLyse (Pharmingen, San Diego, CA, USA), and cells were washed, resuspended in RPMI/10% FBS, and counted. One million lymphocytes were then labeled with fluorochrome-labeled monoclonal antibody cocktails to CD3PerCP, CD8αPE (CalTag), TCRVβ13 FITC (all from Pharmingen if not otherwise stated) and H2-Db:hgp10025–33 APC-labeled tetramers (Coulter Immunomics). Cells were labeled for 30 min on ice in the dark. The cells were then washed twice, fixed and analyzed. Stained cells were collected and analyzed on a FACSCalibur machine, using CellQuest software, and numbers/percentages of T cell populations are reported.

In vivo bioluminescent imaging

In vivo BLI was performed on tumor-bearing mice for either i.c. B16-Fluc or firefly luciferase transduced-Pmel-1 T cell trafficking. Prior to imaging, mice were anesthetized with a cocktail of ketamine:xylazine (4:1) in PBS, injected intraperitoneally with 100 μl of 30 mg/ml of the luciferase substrate, d-Luciferin (Xenogen Corp., Alameda, CA, USA) in PBS. Mice were shaved to minimize the amount of light absorbed by black fur. A cooled charge coupled device (CCD) camera apparatus (IVIS, from Xenogen Corp.) was used to detect photon emission from tumor-bearing mice with an acquisition time of 2–3 min. Analyses of the images were performed as described previously [6] using Living Image software (Xenogen) and Igor Image analysis software (Wave Metrics, Lake Oswego, OR, USA) by drawing regions of interest over the region and obtaining maximum values in photons/s/cm2/steradian or total flux values in photons/s.

Immunohistochemistry

Immunohistochemical staining was performed as described previously [34–36, 39]. Briefly, spleen, cervical lymph node and tumor tissues were immersed in formalin-free zinc fixative (BD Biosciences) and paraffin-embedded. 5–10 μm sections were cut on a microtome (Zeiss) and deparaffinized in xylene prior to staining. Alternatively, tissues were immersed in OCT and snap frozen in isopentane cooled by dry ice. 20 μm sections were cut on a cryostat (Zeiss), fixed in ice-cold acetone, and endogenous peroxidase activity eliminated with 0.3% H2O2/PBS before staining. Sections were then incubated with primary antibodies to CD3ε (500A2, BD Pharmingen, San Diego, CA, USA), CD4 (RM4–5, BD Pharmingen), CD8α (53–6.7, BD Biosciences) and/or a biotinylated CD90.1 (Thy1.1, HIS51 clone, eBioscience). The primary mAb incubation step was followed by a biotinylated secondary mAb (Vector Labs, Burlingame, CA, USA) and developed with a DAB substrate kit (Vector Labs). Negative controls consisted of isotype matched rat or hamster IgG in lieu of the primary mAbs listed above. For Thy1.1 staining, the biotinylated primary mAb was incubated on the sections followed by a streptavidin-HRP step (ABC, Vector Labs), omitting the secondary mAb incubation.

Statistical analysis

All error bars represent standard error of the mean. Continuous variables were compared using a paired Student’s t-test. Significant differences in BLI data were obtained using the Analysis of Variance (ANOVA) Repeated Measures function for groups of mice over the same experimental time course or via paired T tests between different groups at individual timepoints. The survival curves were determined using the Kaplan–Meier method. The log-rank test was used to compare curves between study and control groups. P-values are two-tailed, and P < 0.05 was considered statistically significant. Graphs were constructed using Sigma Plot (Systat Software, Richmond, CA, USA) and statistical functions were analyzed using Systat 11 software.

Results

Adoptive transfer of hgp10025–33-specific CD8+ T cells, hgp10025–33 peptide pulsed dendritic cell vaccination and IL-2 prolongs survival in mice with established CNS tumors

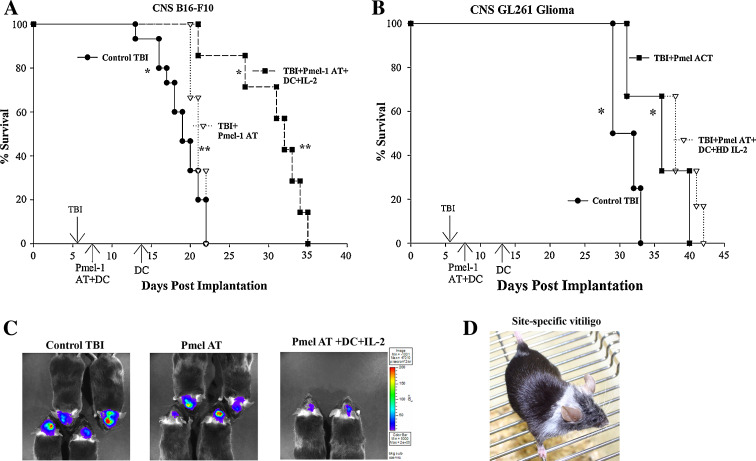

In an effort to model a clinically relevant CNS tumor model, we treated 7-day established i.c. tumors (B16-F10 melanoma or GL261 glioma) with a combinatory immunotherapy regimen consisting of an adoptive transfer of Pmel-1 gp100-specific CD8+ T cells, hgp10025–33 peptide-pulsed DC vaccination and systemic IL-2. Recipient mice underwent lymphodepleting total body radiation (TBI, 500 cGy) to facilitate the in vivo expansion of the adoptively transferred T cells. This adoptive transfer regimen has previously been shown to effectively eradicate subcutaneous B16 melanomas [31], but has not been demonstrated for tumors located in immune privileged sites such as the brain or for other neural crest-derived tumors (such as glioma). In studies conducted with more than 100 mice in five replicate independent experiments, our results demonstrated that we could induce significant increases in survival with this immunotherapy regimen in mice bearing 7-day established i.c. B16-F10 melanomas and orthotopic GL261 primary gliomas (Fig. 1a, b).

Fig. 1.

Treatment of 7-day established i.c. tumors with the adoptive transfer of gp100-specific CD8+ T cells, hgp100 peptide-pulsed DC vaccination and IL-2. a Kaplan–Meier survival curves of 7-day established i.c. B16 melanoma treatment. Groups of mice were initially implanted with 1 × 103 B16 melanoma cells into the brain at day 0, subjected to a non-myeloablative, but lymphodepleting dose of 500 cGy TBI at day 6, followed by the adoptive transfer of Pmel-1 T cells ± hgp10025–33/DC and systemic IL-2. Control mice were given TBI alone, hgp10025–33/DC vaccination in the absence of Pmel-1 adoptive transfer or Pmel-1 adoptive transfer in the absence of DC vaccination. *P = 0.0002; **P = 0.008 by Log-Rank (Mantel) survival analysis. These survival curves represent the collective result of three survival studies (n = 7–15 mice/group). b Kaplan–Meier survival analysis of 7-day established i.c. GL261 glioma treatment. N = 5–6 mice/group and the results have been confirmed twice. *P = 0.04 by Log-Rank (Mantel) survival analysis. c In vivo, bioluminescent imaging of B16-Fluc CNS tumor progression after Pmel-1 AT. Representative picture of groups of mice at day 7 post-AT reflecting CNS tumor progression in mice that received TBI control (left), TBI + Pmel-1 AT alone (middle) or TBI + Pmel-1 AT + hgp10025–33/DC + IL-2 (right). d Representative picture of CNS tumor-bearing mouse that had received Pmel-1 adoptive transfer, hgp10025–33/DC and HD IL-2. The site-specific development of vitiligo frequently was seen in responding mice. This picture was taken at 14 days post-implantation

Since i.c. tumor growth cannot be monitored with calipers, we utilized in vivo BLI of B16-F10 melanoma cells transduced to express firefly luciferase (B16-Fluc) to monitor CNS tumor progression in our treated mice. We have previously demonstrated that B16-Fluc cells grow similarly in vitro and in vivo [6], and this BLI technology is able to non-invasively detect different rates of i.c. tumor growth between groups of mice [21, 34, 35]. BLI of i.c. B16-Fluc tumor progression in groups of mice at 14 days post-implantation (7 days post-immunotherapy) demonstrated greater i.c. tumor progression in control groups of mice receiving TBI only, TBI with Pmel AT alone or TBI with Pmel AT and hgp10025–33/DC vaccination when compared to mice treated with the full treatment regimen consisting of Pmel T cell AT, hgp10025–33/DC and systemic IL-2 (Fig. 1c and data not shown). In an interesting, but not altogether unexpected finding, we observed dramatic regional autoimmune vitiligo occurring around the head and neck in mice, given the full treatment regimen (Fig. 1d). This pattern of regional vitiligo was selectively seen only in i.c. tumor-bearing mice and was frequently associated with significant extension of survival. These results suggest that adoptively transferred, self-tumor antigen-specific CD8+ T cells can mediate anti-tumor immunity to tumors located in the brain.

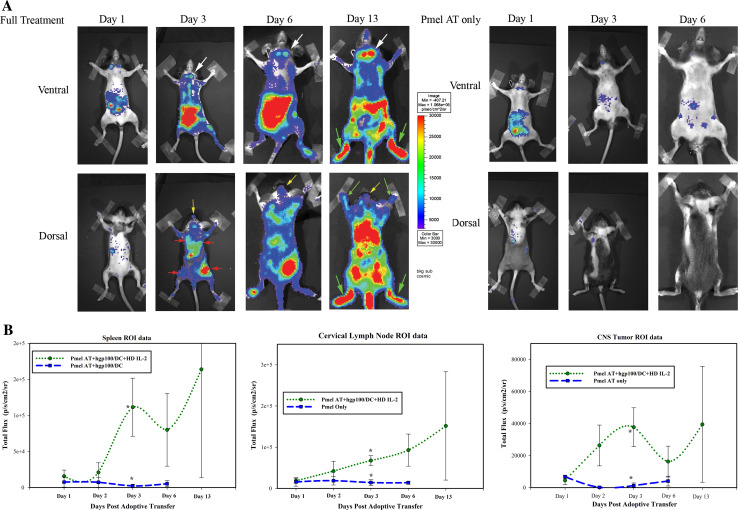

Genetically labeled Pmel-1 T cells can home to tumors located in the brain

Although conventional assays can give important information concerning where gp100-specific CD8+ T cells are found at discrete timepoints, the ability to serially monitor the trafficking of such T cells over time would allow us to better understand where these adoptively transferred cells migrate to in real time. To accomplish this, we transduced Pmel-1 T cells with retroviral constructs encoding firefly luciferase so that the trafficking of these cells could be monitored with BLI. The transduction efficiency of these cells was confirmed by FACS analysis of yellow fluorescent protein (YFP) expression in parallel Pmel-1 restimulation cultures and ex vivo luciferase assays (Supplementary Figure 1). These experiments suggested that our transduction efficiency was routinely between 30 and 80%. Transduced Pmel-1 T cells were then adoptively transferred into irradiated mice with established 7-day established CNS tumors and imaged by BLI thereafter. In addition, groups of mice that were adoptively transferred with transduced Pmel-1 T cells were either given the full treatment regimen of T cell adoptive transfer, hgp10025–33/DC vaccination and IL-2 or T cell adoptive transfer alone as control. In this fashion, the expansion and trafficking of Pmel-1 T cells could be imaged and compared in mice that received a partial therapeutic regimen compared with mice that received the full tripartite treatment regimen that provided a survival advantage. As demonstrated in Fig. 2, BLI could readily discriminate between mice that had received an adoptive transfer of transduced Pmel-1 T cells alone and mice that received the full treatment regimen. In mice that received the full tripartite combination treatment regimen, T cells initially accumulated in the cervical lymph nodes, abdomen, and spleen at day 1, followed by the accumulation in the lymph nodes draining the dendritic cell vaccination sites (Fig. 2). By 3 days post-T-cell adoptive transfer, there was a significant increase in the expansion and accumulation of transduced Pmel-1 T cells found in the cervical lymph nodes (white arrows), spleen and CNS tumor sites (yellow arrows) in mice given the full treatment regimen compared with mice that only received T cell adoptive transfer (Fig. 2a). The difference in expansion of Pmel-1 T cells between the groups was also quantitated in parallel experiments by FACS analysis (Fig. 4). BLI further demonstrated that Pmel-1 T cells trafficked through the bone marrow (green arrows) and multiple other sites in the abdomen, most likely mesenteric lymph nodes. It is interesting to note that BLI allowed us to detect Pmel-1 cells trafficking to the sites of hgp10025–33/DC vaccination (Fig. 2a, red arrows). In contrast to the mice that only received TBI and transduced Pmel-1 T cell adoptive transfer, mice that received the full tripartite treatment regimen had dramatically enhanced bioluminescent signal of Pmel-1 T cell trafficking and significantly increased cell numbers (Figs. 2b, 4).

Fig. 2.

In vivo trafficking of retroviral-transduced Pmel-1 T cells in mice harboring CNS tumors. Two groups of mice harboring 7-day established i.c. B16 tumors were given an adoptive transfer of retrovirally transduced Pmel-1 T cells. The full treatment group was then vaccinated with hgp10025–33/DC + systemic IL-2, while another group of mice was not treated. a Timecourse bioluminescent imaging of Firefly luciferase expression in Pmel-1 T cells at days 1, 3, 6 and 13 (only full treatment) days post-T cell adoptive transfer. Yellow arrows point to T cells at the CNS tumor; red arrows point to DC vaccination sites; white arrows point to the cervical lymph nodes; green arrows point to the bone marrow. b Quantitative imaging analysis of regions of interest (ROI) from the spleen, CNS tumor and cervical lymph nodes over the timecourse. *P < 0.05 by t-test analysis

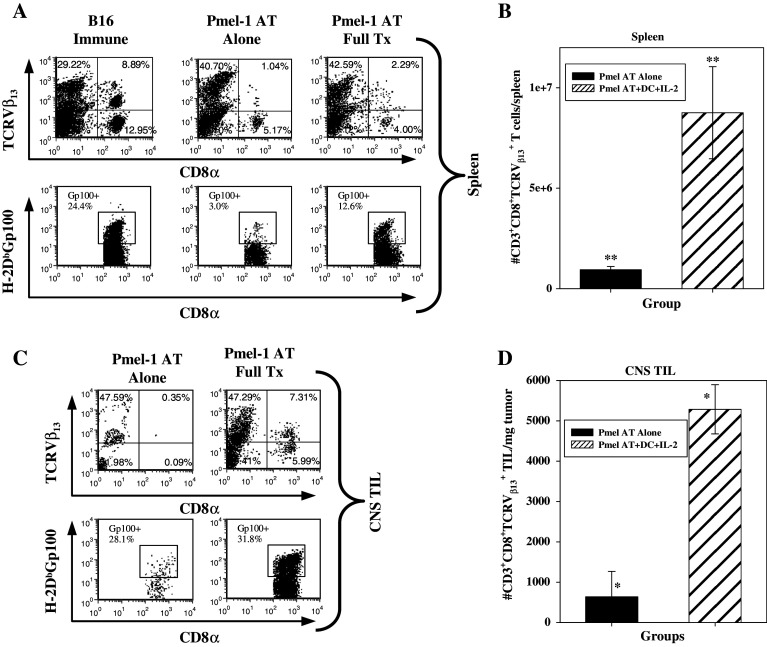

Fig. 4.

FACS Analysis of gp100-specific CD8+ T cells in the spleen and CNS Tumors after adoptive transfer. a Groups of mice received an adoptive transfer of either Pmel-1 T cells alone (middle) or Pmel-1 T cells + hgp10025–33/DC vacc + systemic IL-2 (right). Splenocytes and CNS TIL were then removed at day 14 post-AT, stained for FACS analysis and quantitated. Left panel B16 Immune splenocytes were obtained from a mouse that had previously rejected its s.c. B16 melanoma after Pmel-1 AT, hgp10025–33/DC and systemic IL-2. b Quantification of gp100-specific T cells in the spleen; **P = 0.026. c Detection of gp100-specific T cells in CNS tumors by FACS analysis of i.c. B16 TIL’s in representative mice. Antibodies to CD8α, TCRVβ13 (top) and tetramers to hgp10025–33 tetramers (bottom) were used to compare the percentages of gp100-specific T cells between mice that received an adoptive transfer of Pmel T cells alone or Pmel T cells + hgp10025–33/DC vacc + systemic IL-2. d Quantification of gp100-specific T cells in CNS tumors (right histogram); *P = 0.009

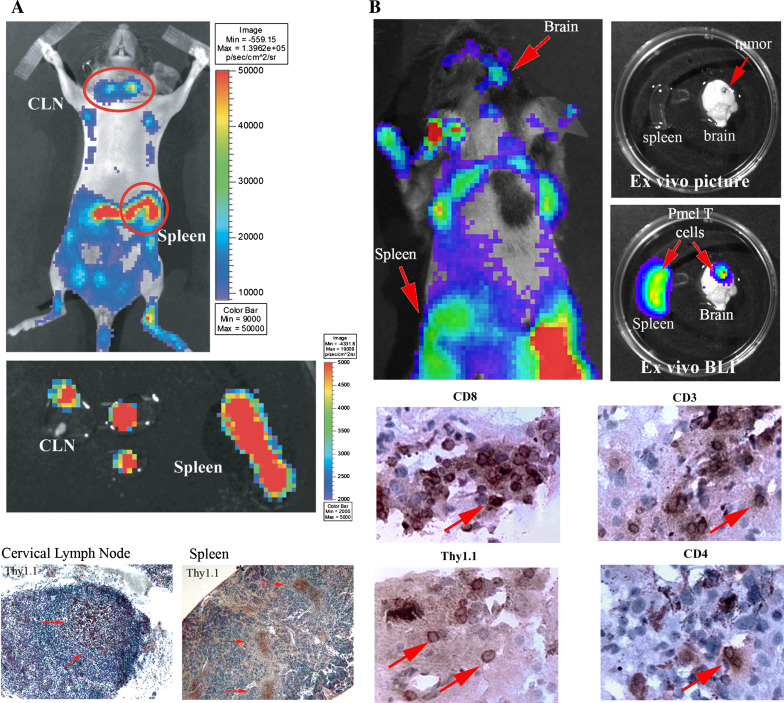

The full treatment mice additionally demonstrated enhanced persistence of the imaging signal, out past 2 weeks post-adoptive transfer, compared with the control treatment group. We confirmed that the imaging signals truly represented the anatomical sites we had suspected by harvesting the brains, spleens and cervical lymph nodes of representative mice and performed ex vivo BLI (Fig. 3). Thus, our ability to serially image the trafficking of self-antigen-specific T cell trafficking in mice harboring CNS tumors has greatly enhanced our understanding of where properly activated, anti-tumor T cells migrate to and persist in real time.

Fig. 3.

Ex vivo confirmation of Pmel-1 T cell trafficking. a Representative mice were analyzed by in vivo BLI at day 10. The spleen and cervical lymph nodes were then excised, subjected to ex vivo imaging and finally stained by immunohistochemistry for the Thy1.1 congenic marker expressed on the adoptively transferred Pmel-1 T cells, but not on the host, Thy1.2+ C57BL/6 cells. Shown are representative pictures that have been confirmed in replicate studies. b The spleen and brain were also analyzed by in vivo BLI at day 15, followed by ex vivo imaging. 10 μm brain tumor sections were then stained for Thy1.1, CD3, CD4 and CD8. The picture is of a representative mouse (n = 3/group) in an experiment that has been repeated twice with similar findings. Magnification: cervical lymph node, 100×; spleen, 20×; tumor, 200×

Pmel-1 T cell adoptive transfer, g10025–33/DC vaccination and systemic IL-2 treatment results in enhanced i.c. tumor infiltration

To confirm the distribution and tumor targeting of adoptively transferred Pmel-1 cells detected by BLI, recipient mice were killed at different time points; spleen, lymph node, bone marrow cells and i.c. tumor-associated lymphocytes (TIL) were isolated and stained ex vivo with antibodies to TCRVβ13, CD3, CD8 and H-2Db tetramers loaded with hgp10025–33. The full treatment regimen, consisting of Pmel-1 adoptive transfer, hgp10025–33 peptide-pulsed DC vaccination and systemic IL-2, resulted in a significant increase in gp10025–33-specific CD8+ T cells in the spleen, lymph nodes and i.c. tumors compared with mice who received Pmel-1 T cell adoptive transfer alone or hgp10025–33/DC vaccination alone (Fig. 4 and data not shown). These data confirm that proper environment and activation of self-tumor antigen-specific T cells can elicit dramatic tumor antigen-specific T cell infiltration of CNS tumors.

To confirm the in situ trafficking of these Pmel-1, gp100-specific CD8+ T cells into the regional lymphoid system and brain tumors, we used immunohistochemistry to stain for CD3, CD4, CD8 and Thy1.1. Thy1.1 is a congenic marker expressed on the adoptively transferred Pmel-1 T cells, but not on the host, Thy1.2+ C57BL/6 cells. Representative pictures from these studies are shown in Fig. 3, confirming the presence of the adoptively transferred, Thy1.1+, CD3+and CD8+ cells in the spleen, cervical lymph nodes and i.c. tumor. Interestingly, CD4+ cells were additionally observed within the tumor parenchyma in mice that received the full treatment regimen (Fig. 3). These results confirm our BLI findings that gp10025–33-specific CD8+ T cells traffic through lymphoid organs and accumulate in CNS tumors.

Discussion

The studies outlined in this report establish a migration pattern that tumor-specific T cells adopt for tumors growing in the brain. Real-time in vivo imaging permitted us to dynamically visualize where tumor-specific CD8+ T cells were activated and where they subsequently migrated to, before and after homing to the CNS tumor. These imaging analyses were validated by standard ex vivo assays to document the utility of this in vivo imaging approach. Our results demonstrate that the adoptively transferred CD8+ T cells initially home to the cervical lymph nodes and spleen. It is possible that the cervical lymph nodes provide an early source of antigen for restimulation because these lymph nodes are thought to provide drainage from the brain, as well as a source of cross-presenting antigen presenting cells [4, 5, 7, 22]. By day 3 post-adoptive transfer, these T cells proliferated extensively and accumulated in lymph nodes draining the hgp10025–33/DC vaccination sites, the spleen, the i.c. tumor, with some retention in the bone marrow. Following a second hgp10025–33/DC vaccination, significant accumulation of tumor-specific T cells occurred in the bone marrow, as well as circulation through the cervical and other lymph nodes, spleen and CNS tumor. The bone marrow has previously been demonstrated to be a preferential homing and proliferative site for memory T cells [3, 28]. As such, the bone marrow may provide an important reservoir of circulating memory T cells that can continually recirculate and replenish the supply of activated, tumor-specific CD8+ T cells homing to brain tumors. Ongoing experiments in our laboratories are currently testing the fundamental requirements of where tumor-specific CD8+ T cells must home for effective anti-tumor immunity within the CNS.

We recently demonstrated that both murine and human gliomas express immunologically relevant levels of many melanoma-associated antigens [38]. However, the regulation of self-tumor antigen-specific T cell trafficking to tumors within the CNS is currently not well understood. Previous studies have shown that clinically relevant anti-tumor immune responses directed towards i.c. tumors are accompanied by increased numbers of CD4+ and CD8+ T cells at the tumor site [4, 26, 29, 34, 39, 53, 54] and selective expression of integrin homing phenotypes [5, 45]. However, the monitoring of immune responses to CNS tumors is currently based on ex vivo assays (e.g., MHC tetramer and ELISPOT assays, immunohistochemistry), all of which necessitate the killing of groups of mice at multiple timepoints. Furthermore, their use as surrogate endpoints for the clinical development of immunotherapy strategies in brain tumor patients does not take into account the dynamic evolution of the T cell responses. To further improve cell-based cancer immunotherapy protocols, we believe that it is essential to complement existing immune monitoring approaches with non-invasive biomedical imaging techniques capable of monitoring the persistence and trafficking of transferred T cells at a whole body level.

Our results provide important findings concerning the in vivo trafficking of tumor-specific CD8+ T cells for effective anti-tumor immunity to tumors within the CNS. Our findings extend our belief that CNS draining lymph nodes (e.g., cervical lymph nodes) are important for brain tumor immunity. These results also demonstrate that serial, in vivo imaging studies can impart real-time information for tumor-specific T cell trafficking that may be able to supplant the traditional ex vivo staining methodology in future. We believe that this documentation of anti-tumor activity and extended survival, coupled with dynamic, real-time imaging of T cell trafficking, provides new insights into the critical parameters necessary to elicit effective anti-tumor immunity against CNS tumors.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported in part by NIH/NCI grants K01 CA111402 (to RMP), R01 CA 112358 (to LML), P50 CA086306 (to AR), the Philip R. and Kenneth A. Jonsson Foundations (to LML), the Musella Foundation for Brain Tumor Research (to LML and RMP), and the Neidorf Family Foundation (to LML and RMP). ONW is an investigator of the Howard Hughes Medical Institute. CGR was supported by the In Vivo Cellular and Molecular Imaging Centers (ICMIC) Developmental Project Award. CJS was supported by the Pharmacological Sciences Training grant PHS T32 CM008652. RMP is the recipient of the Howard Temin NCI Career Development award. AR is the recipient of a STOP Cancer Career Development award and K23 CA93376.

Abbreviations

- BLI

Bioluminescent imaging

- CNS

Central nervous system

- DC

Dendritic cell

- TAA

Tumor-associated antigen

- i.c.

Intracranial

- TBI

Total body irradiation

- TIL

Tumor-infiltrating lymphocytes

References

- 1.Antony PA, Piccirillo CA, Akpinarli A, Finkelstein SE, Speiss PJ, Surman DR, Palmer DC, Chan CC, Klebanoff CA, Overwijk WW, Rosenberg SA, Restifo NP. CD8+ T cell immunity against a tumor/self-antigen is augmented by CD4+ T helper cells and hindered by naturally occurring T regulatory cells. J Immunol. 2005;174(5):2591–2601. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.174.5.2591. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Azadniv M, Dugger K, Bowers WJ, Weaver C, Crispe IN. Imaging CD8+ T cell dynamics in vivo using a transgenic luciferase reporter. Int Immunol. 2007;19(10):1165–1173. doi: 10.1093/intimm/dxm086. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Becker TC, Coley SM, Wherry EJ, Ahmed R. Bone marrow is a preferred site for homeostatic proliferation of memory CD8 T cells. J Immunol. 2005;174(3):1269–1273. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.174.3.1269. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Calzascia T, Di Berardino-Besson W, Wilmotte R, Masson F, de Tribolet N, Dietrich PY, Walker PR. Cutting edge: cross-presentation as a mechanism for efficient recruitment of tumor-specific CTL to the brain. J Immunol. 2003;171(5):2187–2191. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.171.5.2187. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Calzascia T, Masson F, Di Berardino-Besson W, Contassot E, Wilmotte R, Aurrand-Lions M, Ruegg C, Dietrich PY, Walker PR. Homing phenotypes of tumor-specific CD8 T cells are predetermined at the tumor site by crosspresenting APCs. Immunity. 2005;22(2):175–184. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2004.12.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Craft N, Bruhn KW, Nguyen BD, Prins R, Liau LM, De Collisson EA A, Kolodney MS, Gambhir SS, Miller JF. Bioluminescent imaging of melanoma in live mice. J Invest Dermatol. 2005;125(1):159–165. doi: 10.1111/j.0022-202X.2005.23759.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.de Vos AF, van Meurs M, Brok HP, Boven LA, Hintzen RQ, van der Valk P, Ravid R, Rensing S, Boon L, t Hart BA, Laman JD. Transfer of central nervous system autoantigens and presentation in secondary lymphoid organs. J Immunol. 2002;169(10):5415–5423. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.169.10.5415. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Dubey P, Su H, Adonai N, Du S, Rosato A, Braun J, Gambhir SS, Witte ON. Quantitative imaging of the T cell antitumor response by positron-emission tomography. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2003;100(3):1232–1237. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0337418100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Dudley ME, Wunderlich JR, Robbins PF, Yang JC, Hwu P, Schwartzentruber DJ, Topalian SL, Sherry R, Restifo NP, Hubicki AM, Robinson MR, Raffeld M, Duray P, Seipp CA, Rogers-Freezer L, Morton KE, Mavroukakis SA, White DE, Rosenberg SA. Cancer regression and autoimmunity in patients after clonal repopulation with antitumor lymphocytes. Science. 2002;298(5594):850–854. doi: 10.1126/science.1076514. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Dudley ME, Wunderlich JR, Yang JC, Sherry RM, Topalian SL, Restifo NP, Royal RE, Kammula U, White DE, Mavroukakis SA, Rogers LJ, Gracia GJ, Jones SA, Mangiameli DP, Pelletier MM, Gea-Banacloche J, Robinson MR, Berman DM, Filie AC, Abati A, Rosenberg SA. Adoptive cell transfer therapy following non-myeloablative but lymphodepleting chemotherapy for the treatment of patients with refractory metastatic melanoma. J Clin Oncol. 2005;23(10):2346–2357. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2005.00.240. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Edinger M, Cao YA, Verneris MR, Bachmann MH, Contag CH, Negrin RS. Revealing lymphoma growth and the efficacy of immune cell therapies using in vivo bioluminescence imaging. Blood. 2003;101(2):640–648. doi: 10.1182/blood-2002-06-1751. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Eguchi J, Kuwashima N, Hatano M, Nishimura F, Dusak JE, Storkus WJ, Okada H. IL-4-transfected tumor cell vaccines activate tumor-infiltrating dendritic cells and promote type-1 immunity. J Immunol. 2005;174(11):7194–7201. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.174.11.7194. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ehtesham M, Kabos P, Gutierrez MA, Samoto K, Black KL, Yu JS. Intratumoral dendritic cell vaccination elicits potent tumoricidal immunity against malignant glioma in rats. J Immunother (1997) 2003;26(2):107–116. doi: 10.1097/00002371-200303000-00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Gattinoni L, Finkelstein SE, Klebanoff CA, Antony PA, Palmer DC, Spiess PJ, Hwang LN, Yu Z, Wrzesinski C, Heimann DM, Surh CD, Rosenberg SA, Restifo NP. Removal of homeostatic cytokine sinks by lymphodepletion enhances the efficacy of adoptively transferred tumor-specific CD8+ T cells. J Exp Med. 2005;202(7):907–912. doi: 10.1084/jem.20050732. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Gattinoni L, Klebanoff CA, Palmer DC, Wrzesinski C, Kerstann K, Yu Z, Finkelstein SE, Theoret MR, Rosenberg SA, Restifo NP. Acquisition of full effector function in vitro paradoxically impairs the in vivo antitumor efficacy of adoptively transferred CD8+ T cells. J Clin Invest. 2005;115(6):1616–1626. doi: 10.1172/JCI24480. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Graf MR, Prins RM, Merchant RE. IL-6 secretion by a rat T9 glioma clone induces a neutrophil-dependent antitumor response with resultant cellular, antiglioma immunity. J Immunol. 2001;166(1):121–129. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.166.1.121. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Hawley RG, Lieu FH, Fong AZ, Hawley TS. Versatile retroviral vectors for potential use in gene therapy. Gene Ther. 1994;1(2):136–138. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Heimberger AB, Archer GE, Crotty LE, McLendon RE, Friedman AH, Friedman HS, Bigner DD, Sampson JH. Dendritic cells pulsed with a tumor-specific peptide induce long-lasting immunity and are effective against murine intracerebral melanoma. Neurosurgery. 2002;50(1):158–164. doi: 10.1097/00006123-200201000-00024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Heimberger AB, Crotty LE, Archer GE, Hess KR, Wikstrand CJ, Friedman AH, Friedman HS, Bigner DD, Sampson JH. Epidermal growth factor receptor VIII peptide vaccination is efficacious against established intracerebral tumors. Clin Cancer Res. 2003;9(11):4247–4254. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Heimberger AB, Crotty LE, Archer GE, McLendon RE, Friedman A, Dranoff G, Bigner DD, Sampson JH. Bone marrow-derived dendritic cells pulsed with tumor homogenate induce immunity against syngeneic intracerebral glioma. J Neuroimmunol. 2000;103(1):16–25. doi: 10.1016/S0165-5728(99)00172-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kahlon KS, Brown C, Cooper LJ, Raubitschek A, Forman SJ, Jensen MC. Specific recognition and killing of glioblastoma multiforme by interleukin 13-zetakine redirected cytolytic T cells. Cancer Res. 2004;64(24):9160–9166. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-04-0454. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Karman J, Ling C, Sandor M, Fabry Z. Initiation of immune responses in brain is promoted by local dendritic cells. J Immunol. 2004;173(4):2353–2361. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.173.4.2353. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kim YJ, Dubey P, Ray P, Gambhir SS, Witte ON. Multimodality imaging of lymphocytic migration using lentiviral-based transduction of a tri-fusion reporter gene. Mol Imaging Biol. 2004;6(5):331–340. doi: 10.1016/j.mibio.2004.06.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Koehne G, Doubrovin M, Doubrovina E, Zanzonico P, Gallardo HF, Ivanova A, Balatoni J, Teruya-Feldstein J, Heller G, May C, Ponomarev V, Ruan S, Finn R, Blasberg RG, Bornmann W, Riviere I, Sadelain M, O’Reilly RJ, Larson SM, Tjuvajev JG. Serial in vivo imaging of the targeted migration of human HSV-TK-transduced antigen-specific lymphocytes. Nat Biotechnol. 2003;21(4):405–413. doi: 10.1038/nbt805. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kowolik CM, Topp MS, Gonzalez S, Pfeiffer T, Olivares S, Gonzalez N, Smith DD, Forman SJ, Jensen MC, Cooper LJ. CD28 costimulation provided through a CD19-specific chimeric antigen receptor enhances in vivo persistence and antitumor efficacy of adoptively transferred T cells. Cancer Res. 2006;66(22):10995–11004. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-06-0160. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Kuwashima N, Nishimura F, Eguchi J, Sato H, Hatano M, Tsugawa T, Sakaida T, Dusak JE, Fellows-Mayle WK, Papworth GD, Watkins SC, Gambotto A, Pollack IF, Storkus WJ, Okada H. Delivery of dendritic cells engineered to secrete IFN-alpha into central nervous system tumors enhances the efficacy of peripheral tumor cell vaccines: dependence on apoptotic pathways. J Immunol. 2005;175(4):2730–2740. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.175.4.2730. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Liau LM, Black KL, Prins RM, Sykes SN, DiPatre PL, Cloughesy TF, Becker DP, Bronstein JM. Treatment of intracranial gliomas with bone marrow-derived dendritic cells pulsed with tumor antigens. J Neurosurg. 1999;90(6):1115–1124. doi: 10.3171/jns.1999.90.6.1115. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Mazo IB, Honczarenko M, Leung H, Cavanagh LL, Bonasio R, Weninger W, Engelke K, Xia L, McEver RP, Koni PA, Silberstein LE, von Andrian UH. Bone marrow is a major reservoir and site of recruitment for central memory CD8+ T cells. Immunity. 2005;22(2):259–270. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2005.01.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Nishimura F, Dusak JE, Eguchi J, Zhu X, Gambotto A, Storkus WJ, Okada H. Adoptive transfer of type 1 CTL mediates effective anti-central nervous system tumor response: critical roles of IFN-inducible protein-10. Cancer Res. 2006;66(8):4478–4487. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-05-3825. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Okada H, Tsugawa T, Sato H, Kuwashima N, Gambotto A, Okada K, Dusak JE, Fellows-Mayle WK, Papworth GD, Watkins SC, Chambers WH, Potter DM, Storkus WJ, Pollack IF. Delivery of interferon-alpha transfected dendritic cells into central nervous system tumors enhances the antitumor efficacy of peripheral peptide-based vaccines. Cancer Res. 2004;64(16):5830–5838. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-04-0130. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Overwijk WW, Theoret MR, Finkelstein SE, Surman DR, de Jong LA, Vyth-Dreese FA, Dellemijn TA, Antony PA, Spiess PJ, Palmer DC, Heimann DM, Klebanoff CA, Yu Z, Hwang LN, Feigenbaum L, Kruisbeek AM, Rosenberg SA, Restifo NP. Tumor regression and autoimmunity after reversal of a functionally tolerant state of self-reactive CD8+ T cells. J Exp Med. 2003;198(4):569–580. doi: 10.1084/jem.20030590. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Palmer DC, Balasubramaniam S, Hanada K, Wrzesinski C, Yu Z, Farid S, Theoret MR, Hwang LN, Klebanoff CA, Gattinoni L, Goldstein AL, Yang JC, Restifo NP. Vaccine-stimulated, adoptively transferred CD8+ T cells traffic indiscriminately and ubiquitously while mediating specific tumor destruction. J Immunol. 2004;173(12):7209–7216. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.173.12.7209. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Ponomarev V, Doubrovin M, Lyddane C, Beresten T, Balatoni J, Bornman W, Finn R, Akhurst T, Larson S, Blasberg R, Sadelain M, Tjuvajev JG. Imaging TCR-dependent NFAT-mediated T-cell activation with positron emission tomography in vivo. Neoplasia. 2001;3(6):480–488. doi: 10.1038/sj.neo.7900204. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Prins RM, Bruhn KW, Craft N, Lin JW, Kim CH, Odesa SK, Miller JF, Liau LM. Central nervous system tumor immunity generated by a recombinant listeria monocytogenes vaccine targeting tyrosinase related protein-2 and real-time imaging of intracranial tumor burden. Neurosurgery. 2006;58(1):169–178. doi: 10.1227/01.NEU.0000192367.29047.64. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Prins RM, Craft N, Bruhn KW, Khan-Farooqi H, Koya RC, Stripecke R, Miller JF, Liau LM. The TLR-7 agonist, imiquimod, enhances dendritic cell survival and promotes tumor antigen-specific T cell priming: relation to central nervous system antitumor immunity. J Immunol. 2006;176(1):157–164. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.176.1.157. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Prins RM, Incardona F, Lau R, Lee P, Claus S, Zhang W, Black KL, Wheeler CJ. Characterization of defective CD4-CD8-T cells in murine tumors generated independent of antigen specificity. J Immunol. 2004;172(3):1602–1611. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.172.3.1602. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Prins RM, Liau LM. Cellular immunity and immunotherapy of brain tumors. Front Biosci. 2004;9:3124–3136. doi: 10.2741/1465. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Prins RM, Odesa SK, Liau LM. Immunotherapeutic targeting of shared melanoma-associated antigens in a murine glioma model. Cancer Res. 2003;63(23):8487–8491. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Prins RM, Vo DD, Khan-Farooqi H, Yang MY, Soto H, Economou JS, Liau LM, Ribas A. NK and CD4 cells collaborate to protect against melanoma tumor formation in the brain. J Immunol. 2006;177(12):8448–8455. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.177.12.8448. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Radu CG, Shu CJ, Shelly SM, Phelps ME, Witte ON. Positron emission tomography with computed tomography imaging of neuroinflammation in experimental autoimmune encephalomyelitis. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2007;104(6):1937–1942. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0610544104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Ray P, Tsien R, Gambhir SS. Construction and validation of improved triple fusion reporter gene vectors for molecular imaging of living subjects. Cancer Res. 2007;67(7):3085–3093. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-06-2402. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Ribas A, Butterfield LH, Hu B, Dissette VB, Chen AY, Koh A, Amarnani SN, Glaspy JA, McBride WH, Economou JS. Generation of T-cell immunity to a murine melanoma using MART-1-engineered dendritic cells. J Immunother. 2000;23(1):59–66. doi: 10.1097/00002371-200001000-00008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Ribas A, Butterfield LH, McBride WH, Dissette VB, Koh A, Vollmer CM, Hu B, Chen AY, Glaspy JA, Economou JS. Characterization of antitumor immunization to a defined melanoma antigen using genetically engineered murine dendritic cells. Cancer Gene Ther. 1999;6(6):523–536. doi: 10.1038/sj.cgt.7700076. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Sampson JH, Archer GE, Ashley DM, Fuchs HE, Hale LP, Dranoff G, Bigner DD. Subcutaneous vaccination with irradiated, cytokine-producing tumor cells stimulates CD8+ cell-mediated immunity against tumors located in the “immunologically privileged” central nervous system. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1996;93(19):10399–10404. doi: 10.1073/pnas.93.19.10399. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Sasaki K, Zhu X, Vasquez C, Nishimura F, Dusak JE, Huang J, Fujita M, Wesa A, Potter DM, Walker PR, Storkus WJ, Okada H. Preferential expression of very late antigen-4 on type 1 CTL cells plays a critical role in trafficking into central nervous system tumors. Cancer Res. 2007;67(13):6451–6458. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-06-3280. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Shu CJ, Guo S, Kim YJ, Shelly SM, Nijagal A, Ray P, Gambhir SS, Radu CG, Witte ON. Visualization of a primary anti-tumor immune response by positron emission tomography. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2005;102(48):17412–17417. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0508698102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Singh H, Serrano LM, Pfeiffer T, Olivares S, McNamara G, Smith DD, Al-Kadhimi Z, Forman SJ, Gillies SD, Jensen MC, Colcher D, Raubitschek A, Cooper LJ. Combining adoptive cellular and immunocytokine therapies to improve treatment of B-lineage malignancy. Cancer Res. 2007;67(6):2872–2880. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-06-2283. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Su H, Chang DS, Gambhir SS, Braun J. Monitoring the antitumor response of naive and memory CD8 T cells in RAG1-/- mice by positron-emission tomography. J Immunol. 2006;176(7):4459–4467. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.176.7.4459. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Walker PR, Calzascia T, de Tribolet N, Dietrich PY. T-cell immune responses in the brain and their relevance for cerebral malignancies. Brain Res Brain Res Rev. 2003;42(2):97–122. doi: 10.1016/S0165-0173(03)00141-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Wang LX, Chen BG, Plautz GE. Adoptive immunotherapy of advanced tumors with CD62 L-selectin(low) tumor-sensitized T lymphocytes following ex vivo hyperexpansion. J Immunol. 2002;169(6):3314–3320. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.169.6.3314. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Wang LX, Li R, Yang G, Lim M, O’Hara A, Chu Y, Fox BA, Restifo NP, Urba WJ, Hu HM. Interleukin-7-dependent expansion and persistence of melanoma-specific T cells in lymphodepleted mice lead to tumor regression and editing. Cancer Res. 2005;65(22):10569–10577. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-05-2117. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Wang LX, Shu S, Disis ML, Plautz GE. Adoptive transfer of tumor-primed, in vitro-activated, CD4+ T effector cells (TEs) combined with CD8+ TEs provides intratumoral TE proliferation and synergistic antitumor response. Blood. 2007;109(11):4865–4876. doi: 10.1182/blood-2006-09-045245. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Wang LX, Shu S, Plautz GE. Host lymphodepletion augments T cell adoptive immunotherapy through enhanced intratumoral proliferation of effector cells. Cancer Res. 2005;65(20):9547–9554. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-05-1175. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Zhu X, Nishimura F, Sasaki K, Fujita M, Dusak JE, Eguchi J, Fellows-Mayle W, Storkus WJ, Walker PR, Salazar AM, Okada H. Toll like receptor-3 ligand poly-ICLC promotes the efficacy of peripheral vaccinations with tumor antigen-derived peptide epitopes in murine CNS tumor models. J Transl Med. 2007;5:10. doi: 10.1186/1479-5876-5-10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.