Abstract

We have previously reported the activity of the IGF-1R/InsR inhibitor, BMS-554417, in breast and ovarian cancer cell lines. Further studies indicated treatment of OV202 ovarian cancer cells with BMS-554417 increased phosphorylation of HER2. In addition, treatment with the panHER inhibitor, BMS-599626, resulted in increased phosphorylation of IGF1-R, suggesting a reciprocal crosstalk mechanism. In a panel of five ovarian cancer cell lines simultaneous treatment with the IGF-1R/InsR inhibitor, BMS-536924 and BMS-599626 resulted in a synergistic antiproliferative effect. Furthermore, combination therapy decreased AKT and ERK activation and increased biochemical and nuclear morphological changes consistent with apoptosis as compared to either agent alone. In response to treatment with BMS-536924, increased expression and activation of various members of the HER family of receptors were seen in all five ovarian cancer cell lines, suggesting inhibition of IGF-1R/InsR results in adaptive upregulation of the HER pathway. Using MCF-7 breast cancer cell variants that overexpressed HER1 or HER2, we then tested the hypothesis that HER receptor expression is sufficient to confer resistance to IGF-1R targeted therapy. In the presence of activating ligands EGF or heregulin, respectively, MCF-7 cells expressing HER1 or HER2 were resistant to BMS-536924 as determined in a proliferation and clonogenic assay. These data suggested that simultaneous treatment with inhibitors of the IGF-1 and HER family of receptors may be an effective strategy for clinical investigations of IGF-1R inhibitors in breast and ovarian cancer and that targeting HER1 and HER2 may overcome clinical resistance to IGF-1R inhibitors.

Keywords: IGF-1R inhibition, erbB receptor, drug resistance, receptor crosstalk, median effect analysis

Introduction

The insulin-like growth factor 1 (IGF-1) pathway is a complex and highly regulated system that is important in human growth and development(1). In human cancers, multiple components of this system become dysregulated and provide growth and survival advantages to tumor cells(2). In particular, the IGF-1 system has been implicated in the development and growth of several cancers, including breast, prostate and colon(3-5). It has also been identified as a mechanism by which the tumors evade death by several important anti-cancer therapies including cytotoxic chemotherapy, hormonal therapy, receptor tyrosine kinase inhibitor therapy, and radiation therapy(6-14). Since the IGF-1 pathway is active in the majority of solid and hematological malignancies, targeting this system has been an area of increasing drug development interest.

In targeting the IGF-1 system, there are multiple key components that must be considered(2, 15, 16). Central to the system are it two stimulatory ligands, IGF-1 and IGF-2. These circulating ligands provide proliferative and pro-survival signaling through their binding to the receptor tyrosine kinases, IGF-1 receptor (IGF-1R) and the insulin receptor (InsR). The affinity of IGF-1R and InsR for the binding of IGF-1 and -2, as well as the metabolic counterpart, insulin, is dependent on the presence hybrid IGF-1R/InsR pairs, as well as the isoform of InsR. Specifically, the fetal form or isoform A of the InsR has proliferative and prosurvival effects upon binding IGF-2, while the metabolic InsR isoform B has sub-physiologic binding affinity for any ligand except insulin(17, 18). Additionally, a non-signaling membrane receptors, IGF-2 receptor (IGF-2R), binds and internalizes IGF-2, serving as a regulatory ‘sink’ for this stimulatory ligand(19).

Furthermore, the stimulatory effects of IGF-1 and -2 are further regulated by circulating IGF binding proteins (IGFBP) 1 through 6(20). IGFBPs, which vary in the binding affinities for IGF-1 and -2, limit the bioavailability of these ligands for receptor binding.

There are a number of potential strategies by which to target and inhibit the IGF-1 system which have been reviewed elsewhere(21). However, a few strategies have emerged that are clinically feasible and are under early preclinical and clinical investigations. Monoclonal antibodies targeting the IGF-1R (IGF-1Rmab) are currently being investigated in phase I and II clinical trials. IGF-1Rmab is an attractive strategy, as it targets the major proliferative kinase in the IGF-1 system and has little affinity for the InsR. Early clinical investigations with IGF-1Rmab’s suggest that IGF-1Rmab are very well tolerated and have shown early evidence of clinical activity(22). A potential liability to this strategy is that the mitogenic InsR isoform A is not targeted. Tyrosine kinase inhibitors (TKIs) of the IGF-1 system are also in preclinical and clinical development. Due to the nearly identical kinase domain of the IGF-1R and InsR, small molecules inhibitors have been developed that can completely block IGF-1 signaling through IGF1-R and InsR (23-26). However, the potential liability with this strategy is that TKIs may lead to hyperglycemia by blocking the InsR isoform B. The first clinical report of the phase I trial with the IGF-1Rmab, CP-751,871, in fact, reported hyperglycemia as this most common adverse event(22) suggestion some interference with the function of InsR.

As these agents are developed clinically, the mechanisms of resistance to IGF-1R targeting by TKIs or IGF-1Rmab will be important to understand as it can open new therapeutic strategies for the treatment of patients with cancer. Previous data suggested that IGF-1R signaling can provide a mechanism of resistance to HER receptor targeted therapy(9, 27-31). To determine if this apparent crosstalk was bi-directional, we undertook the studies described herein. We investigated the role of IGF-1R crosstalk with HER in IGF1- R and HER resistance. We show that overexpression of activated HER receptors will confer resistance to IGF-1R/InsR inhibition by the TKI BMS-536924 and that by simultaneously targeting HER and IGF-1R synergistic antitumor effects occur in a panel of ovarian cancer cell lines. These results suggest strategies to overcome resistance to IGF-1R targeting and support the early clinical testing of a dual pathway targeting approach.

Materials and Methods

Cell lines and reagents

OV167 and OV202 are ovarian cancer cell lines derived from a primary tumor specimen as described previously(32). A2780 and OVCAR3 ovarian cancer cells lines and MCF-7 breast cancer cell line was purchases from American Type Culture Collection (ATCC, Manassas, VA). SKOV3.ip1 cells were a kind gift from Dr. Ellen Vitetta. MCF-7 and OV202 cells were grown as previously described(23). Medium conditions for the remaining cell lines were as follows: A2780- RPMI with 10% FBS, non-essential amino acids, sodium pyruvate, sodium bicarbonate, L-glutamine, penicillin and streptomycin; OV167 and OVCAR3- RPMI with 10% FBS, L-glutamine, penicillin and streptomycin. All cultures were grown in 5% CO2 at 37° C. With the exception of FBS, all medium and supplements were purchased from Cellgro/Mediatech (Manassas, VA).

Reagents were purchased as follows:

Bovine serum albumin, ampicillin, Tris-HCL, DAPI, Hoechst 33258, SDS, bromphenol blue, glycerol from Sigma (St. Louis, MO); CellTiter 96 Non-Radioactive Cell Proliferation Assay Kit, Wizard Plus SV DNA minipreps, and 10X PBS solution from Promega (Madison, WI); T4 DNA ligase, Hind III and Xba I from New England Biolabs (Ipswich, MA); LongR3 IGF-I (LR3 IGF-I) from Gro Pep (Thebarton, South Australia, Australia); FBS, EGF, Opti-fect, Chemically-competent E. Coli DH5 alpha, Geneticin/G418 from Invitrogen/Biosource (Carlsbad, CA); Heregulin1 (NRG1-β1) from R&D Systems (Minneapolis, MN); Plasmid Midi Kit from Qiagen (Valencia, CA).

Antibodies were purchased from the following vendors:

PARP (mouse monoclonal), Bax (rabbit polyclonal), XIAP (rabbit polyclonal), phospho-AKT (Ser473 and Thr308) (rabbit polyclonal), phospho-Erk1/2 (Thr202/Tyr204) (rabbit polyclonal), Erk (rabbit polyclonal), phospho-p70S6K(Thr421/Ser424) (rabbit polyclonal), p70S6K (rabbit polyclonal), phospho-GSK3b (Ser 21/9) (rabbit polyclonal), GSK3 (rabbit polyclonal), HER2 (mouse monoclonal), phospho HER3 (Tyr1289) (rabbit monoclonal), phospho-IGF-1R/Insulin receptor (Tyr1131/Tyr1146)(rabbit polyclonal) from Cell Signaling Technology (Beverly, MA); Bcl-2 (mouse monoclonal), Bcl-xL (rabbit polyclonal), AKT (goat polyclonal), Actin (goat polyclonal and mouse monoclonal) , Raf-1 (mouse monoclonal), HER4 (mouse monoclonal), IGF-1R (rabbit polyclonal) from Santa Cruz (Santa Cruz, CA); phospho-HER2 (Tyr1248) (rabbit polyclonal), phospho-EGFR (Tyr1173) (mouse monoclonal), EGFR (sheep polyclonal) with A431 positive control lysate from Upstate Biotechnology (Lake Placid, NY); HER3 (mouse monoclonal) from Lab Vision/Neomarkers (Fremont, CA); Actin (Chicken polyclonal) from Novus Biologicals (Littleton, CO). Peroxidase-coupled secondary antibodies were supplied by KPL (Gaithersburg, MD).

Construction of a stable cell line

The pcDNA 3.1 mammalian expression vector was purchased from Invitrogen (Carlsbad, CA). pcDNA 3.1 vector containing wild-type EGFR was a gift from C. David James. pcDNA 3.1 vector containing wild-type HER2 was a gift from Tai Wong. The vectors were amplified transforming chemically competent E. coli and selecting on LB + ampicillin culture plates. The appropriate vector clones were then verified by diagnostic (Hind III/Xba I) digesting small scale mini preparations (Promega) and then verified by DNA sequencing. Midi scale DNA preparations were then made (Qiagen) and used for mammalian cell transfection of MCF-7 cells using Optifect Reagent, per the product instructions. Stable transfectants were selected in 800 μg/ml of G418 and clonal isolates were confirmed by western blotting.

MTS proliferation assay as performed as previously described(23). Briefly, 5000 cells/per well of a 96-well plate were plated in serum-containing conditions and allowed to attach overnight. The following day, the medium was changed to serum free conditions in the presence of drug and/or ligands as noted in the text. After 72 hours of treatment, the MTS dye reduction was assessed as per the product information label.

Proliferation was calculated as a percentage of the non-drug treated controls. Experiments were performed in at least triplicate. The method of Chou and Talalay was used to determine synergy, as previously described(33, 34). Median effect analysis was performed using Calcusyn Software (Biosoft). With this method a combination index (CI) >1 is deemed antagonistic, a CI<1 is synergistic and CI=1 is considered additive.

Clonogenic Assays were performed as previously described(35). Briefly, MCF-7 cell variants were trypsinized and plated in 60-mm tissue culture plates to a density of 500-1000 per plate, respectively. Cells were allowed to adhere for 22 to 24 hours, then drugs were added as indicated to final concentrations from 1000-fold concentrated stocks. After 72-hour incubation, plates were washed twice with serum-free medium, then fresh medium was added, and cells were incubated until colonies were visible. The plates were washed once with PBS and stained with Coomassie brilliant blue. Visible colonies were counted and reported as percent of control (DMSO treated) cells. Experiments were performed in triplicate.

Western blotting

Protein expression and activation was assessed by western blotting as previously described(23). Briefly, after conditions/treatments were performed as described in text, cells were washed twice with ice-cold PBS. The PBS was then removed as completely as possible and the cells were then immediately lysed by adding 4X sample buffer [250 mmol/L Tris-HCl (pH 6.8), 8% SDS, 20% glycerol, 0.0075% bromphenol blue]. Lysates were then sonicated and frozen immediately at 20°C or assayed for total protein by the bicinchoninic acid method (29). Samples were boiled at 95°C for 15 minutes with 100 mmol/L DTT and separated by SDS-PAGE. After proteins were transferred to nitrocellulose or polyvinylidene difluoride membranes, they were blocked for 1 hour in PBS-T/5% nonfat milk or BSA and probed overnight at 4°C with primary antibodies. After three washes in PBS-T, blots were probed with horseradish peroxidase—conjugated secondary antibody for 1 hour. After three additional washes, bands were visualized with enhanced chemiluminescence reagent (Amersham, Piscataway, NJ) on XoMAT film (Kodak, Rochester, NY). Experiments were performed in triplicate.

Apoptosis assay

Apoptosis was quantitated by assessing nuclear changes indicative of apoptosis (i.e., chromatin condensation and nuclear fragmentation) using the DNA-binding dye 4′,6-diamidino-2-phenylindole dihydrochloride (DAPI), as previously described(36). Cells were seeded in 35-mm plates at 2 × 105 cells per well. After incubation for 24 hours, the plates were washed, changed to serum-free medium containing drug at concentrations and for durations listed in the text. The cells were then stained with DAPI and counted by fluorescence microscopy (Nikon Eclipse TE200; Nikon Corp., Tokyo, Japan). For each treatment, at least 300 cells in 6 different high-power fields were counted. Experiments were performed in triplicate.

Apoptotic morphology imaging

OV202 and SKOV3.ip1 cells were grown to approximately 70% confluency in serum containing medium in 6-well plates. Cells were then treated with BMS-536924, BMS-599626 or the combination in serum free medium for 72 hours, as described in the text. Cells were then fixed within the 6-well plates with 70% ethanol for 15 minutes and washed twice with PBS. Cells were then stained with Hoechst 33258 at 0.5 μg/ml in PBS for 60 minutes and immediately visualized by fluorescent microscopy, as previously described(23). Experiments were performed in triplicate. Images represent typical fields.

Results

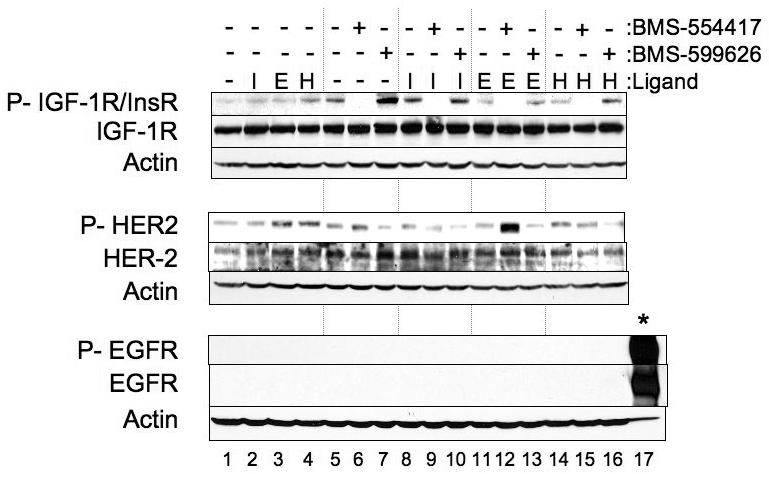

IGF-1R/InsR or HER receptor inhibition stimulates reciprocal receptor phosphorylation

OV202 cells are an epithelial ovarian cancer cell line that express IGF-1R, HER2, and low levels of the InsR and have been described elsewhere(23, 37). These cells were used initially as a proof of concept for targeting the IGF-1R/InsR and confirming specificity. Phosphorylation of IGF-1R and InsR was completely inhibited (Fig 1, lanes 6,9,12,15) upon treating cells with BMS-554417 at doses that resulted in anti-proliferative activity (Fig 2, A). In a reciprocal manner HER2 phosphorylation increased (Fig 1, lane 6) in response to BMS-554417, when compared to DMSO-treated controls (Fig 1, lane 5). Despite the lack of detectable EGFR expression in OV202 cells, the increase in HER2 phosphorylation with BMS-554417 treatment was further enhanced by the addition of EGF (Fig 1, lane 12). To investigate whether this apparent cross signaling was reciprocal in nature, we treated OV202 cells with a specific panHER inhibitor, BMS-599626 (Fig 1, lanes 7,10,13,16)(38). At doses that caused reduction of HER2 phosphorylation, IGF-1R/InsR phosphorylation increased compared to DMSO-treated controls (Fig 1, lane 7). This increase in phosphorylation of IGF-1R/InsR was not enhanced further in the presence of IGF-1, EGF or heregulin.

Figure 1. Bi-directional crosstalk signaling occurs in ovarian cancer cells.

Subconfluent OV202 cells were treated with either DMSO, BMS-554417 (10 μM) or BMS-599626 (10 μM) for one hour in serum free conditions. For the final 15 minutes of drug treatment, 10 nM of IGF-1 LR3 (I), 100 ng/ml of EGF (E) or 5 ng/ml of heregulin (H) were added to the medium. Lysates were then prepared and analyzed by western blotting. Twenty μg of EGF-stimulated A431 lysates (*) were loaded as positive control for total and activated EGFR

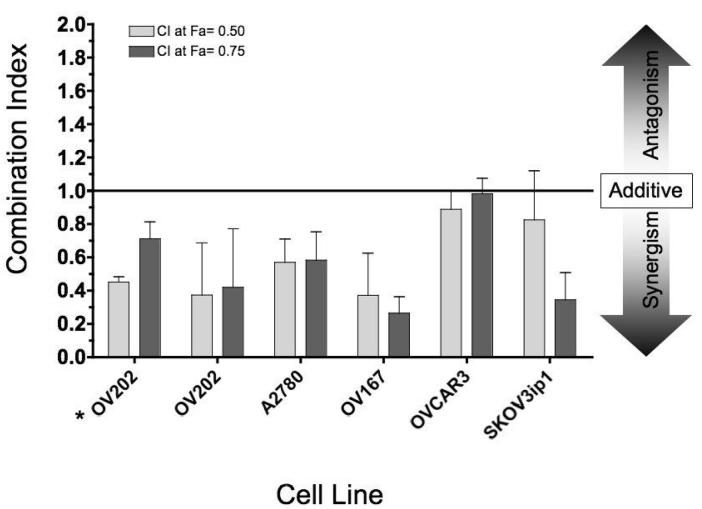

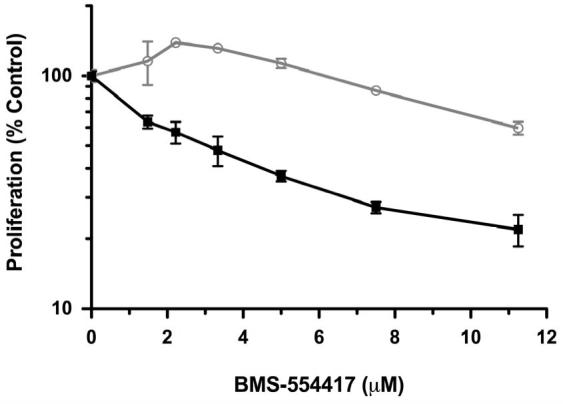

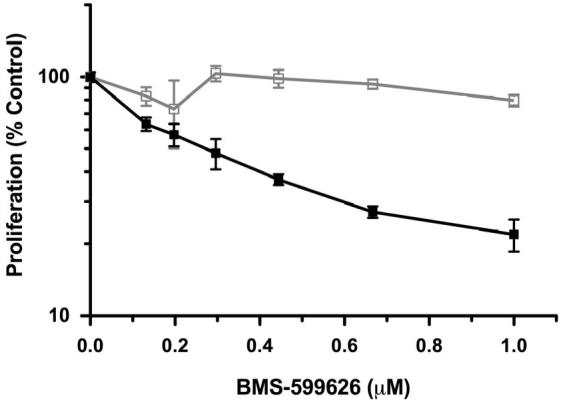

Figure 2. Simultaneous treatment with BMS-536924 and BMS-599626 has synergistic anti-proliferative effects.

A), B) OV202 cells were treated with increasing concentrations of BMS-554417 ( ), BMS-599626 (

), BMS-599626 ( ) or the combination (

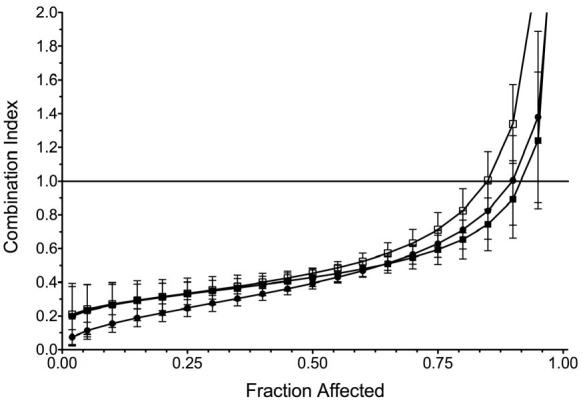

) or the combination ( ) at a fixed ratio (11.25:1). Proliferation was assessed as a function of DMSO treated controls by MTS proliferation assays and reported as a function of either BMS-554417 (A) or BMS-599626 (B) concentrations as described in methods. C) Synergy combination index plots were generated by median effect analysis of OV202 cells treated with the combination of BMS-554417, BMS-599626 or the combination in the absence (

) at a fixed ratio (11.25:1). Proliferation was assessed as a function of DMSO treated controls by MTS proliferation assays and reported as a function of either BMS-554417 (A) or BMS-599626 (B) concentrations as described in methods. C) Synergy combination index plots were generated by median effect analysis of OV202 cells treated with the combination of BMS-554417, BMS-599626 or the combination in the absence ( ) or presence of IGF-1 LR3 (10 nM-

) or presence of IGF-1 LR3 (10 nM-  ) or insulin (10 nM-

) or insulin (10 nM-  ). Error bars represent standard deviation of four replicates; D) Cells were treated with either BMS-536924, BMS-599626 or the combination at various doses. The antiproliferative effects were then assessed and median effect analysis was performed. The combination index values at the 50% (light gray bars) and 75% (dark gray bars) fraction affected are shown. For comparison, OV202 cells treated with BMS-554417 and BMS-599626 (*) were included.

). Error bars represent standard deviation of four replicates; D) Cells were treated with either BMS-536924, BMS-599626 or the combination at various doses. The antiproliferative effects were then assessed and median effect analysis was performed. The combination index values at the 50% (light gray bars) and 75% (dark gray bars) fraction affected are shown. For comparison, OV202 cells treated with BMS-554417 and BMS-599626 (*) were included.

Dual inhibition of IGF-1R/InsR and HER receptors causes synergistic cell killing in multiple ovarian cancer cell lines

Based on the findings above, OV202 cell proliferation was assessed upon treatment with various concentrations of BMS-554417, BMS-599626 alone or in combination at a fixed ratio. At doses of the single agents that had modest antiproliferative effects, the combination treatment appeared to have a significant antiproliferative effect. (Fig 2, A, B). Median effect analysis showed a marked degree of synergy as reflected by CI values less than 0.4 (Fig 2, C)(33). The degree of synergy in the absence or presence of insulin, IGF-1, EGF (data not shown) and heregulin (data not shown) was similar. Further investigations with the 2-(4-substituted-2-oxo-1,2-dihydropyridin-3-yl)-benzimidazole derivative small molecule inhibitors of the IGF-1R focused on the related analog, BMS-536924, which has improved oral exposure and in vivo activity compared to BMS-554417(26, 39). Repeat experiments to assess synergy confirmed that the antiproliferative effect of BMS-536924 in combination with BMS-599626 was synergistic when compared to the effects of the single agents alone (Fig 2,D).

To investigate whether this synergistic antiproliferative activity was specific to OV202 cancer cells, we evaluated the antiproliferative effects of BMS-536924 in combination with BMS-599626 with four other ovarian cancer cell lines. The combination of BMS-536924 demonstrated synergistic antiproliferative activity in all ovarian cancer cell lines as determined by median effect analysis (Fig 2,D). Synergy was observed in OV202, A2780 and OV167 cells at both the 50% and 75% fraction affected, while synergism in OVCAR3 and SKOV3ip1 cells approached additivity at the 75% and 50% fraction affected, respectively.

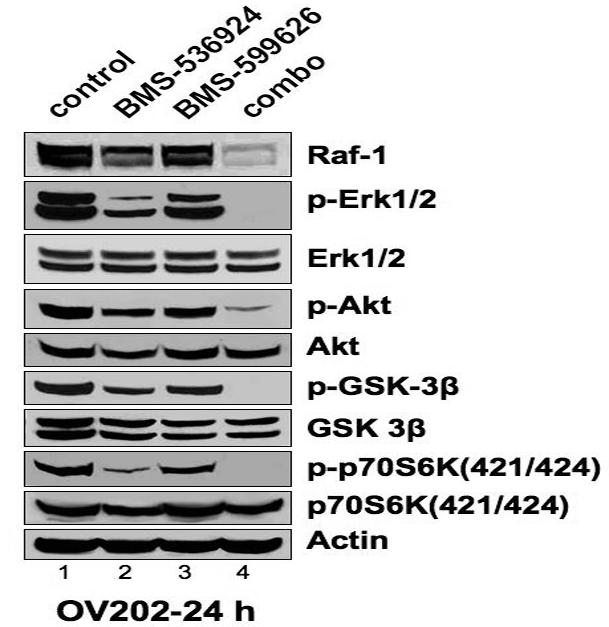

Simultaneous inhibition of IGF-1R/InsR and HER receptors inhibited AKT/ERK activation

To understand the molecular mechanism by which anti-proliferative synergy was observed in ovarian cancer cells treated with BMS-536924 and BMS599626, western blotting for the total and activated forms of key signaling intermediates of the IGF- and HER, and intrinsic apoptotic pathways was performed on OV202 lysates (Fig 3, A). In OV202 cells, treatment with the combination of BMS-536924 and BMS-599626 resulted in decreased phosphorylation of ERK, Akt, GSK-3β and p70-S6 kinase. While total protein expression of these proteins were unchanged, total Raf-1 protein levels were greatly reduced in OV202 cells treated with the combination, compared to the single agent. Thus, proliferative and prosurvival signaling through the AKT and ERK pathways in OV202 cells was dramatically reduced in response to combination treatment with BMS-536924 and BMS-599626 compared to single agent treatment.

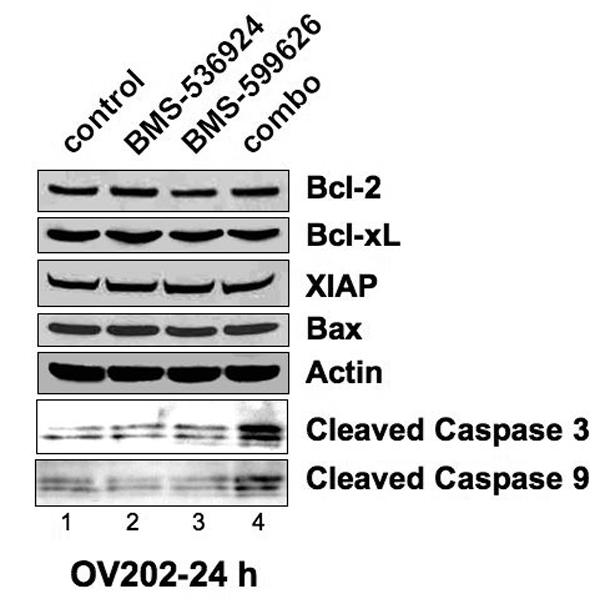

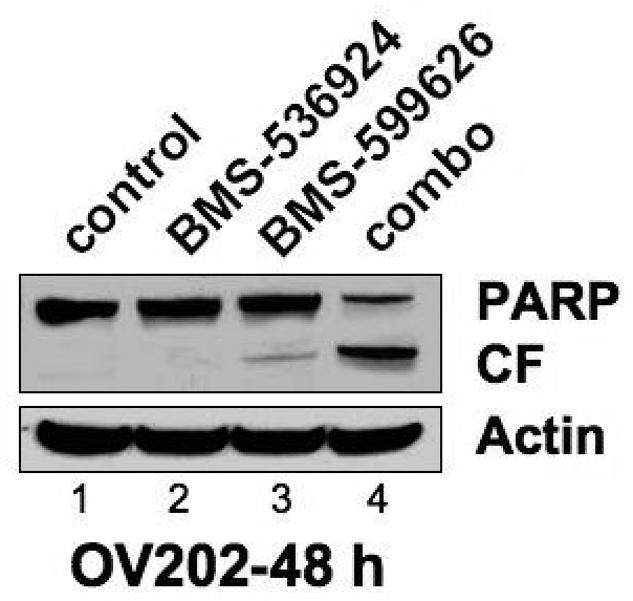

Figure 3. Combined Inhibition of IGF-1/HER signaling decreases activation of AKT/ERK activation and increases caspase/PARP cleavage.

A), B) ,C) Subconfluent OV202 cells were treated with DMSO (control), BMS-536924 (at IC50= 5 μM), BMS-599626 (at IC50= 10 μM) or the combination (combo) in serum free conditions. After either 24 or 48 hours of treatment, cells were washed and 40 μg of lysates were prepared and analyzed by western blotting.

The mechanism of synergism of combining BMS-536924 and BMS-599626 is enhanced apoptosis

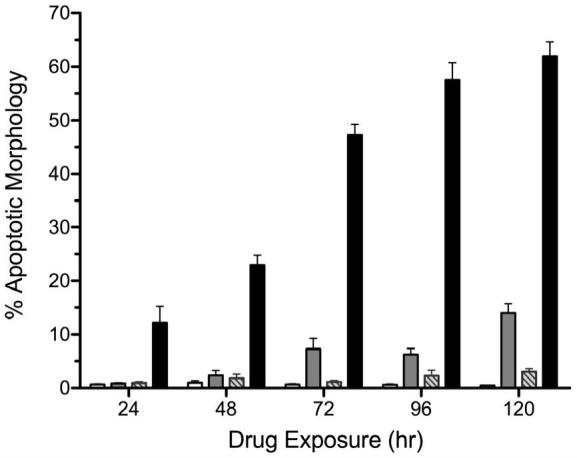

As we have previously demonstrated that single agent IGF-1R/InsR inhibition can induce apoptosis through the intrinsic pathway in OV2020 cells, we hypothesized that the synergistic activity of BMS-536924 and BMS-599626 in OV202 cells was due to enhanced apoptosis. To test this hypothesis, we assessed changes in biochemical and morphologic markers of apoptosis in OV202 cells in the presence of BMS-536924, BMS-599626 and the combination. There were no apparent changes in patterns of expression in the apoptotic proteins Bcl-2, Bcl-XL, XIAP or Bax in response to treatment with BMS-536924 and/or BMS-599626 (Fig 3, B). Despite this, the combination treatment was associated with increased cleavage of caspase 3, caspase 9, and PARP when compared to the single agents, consistent with an enhanced apoptotic death upon treatment with the combination BMS-536924 and BMS-599626 (Fig 4, C). To confirm the biochemical evidence of enhanced apoptosis with combination treatment, the extent of apoptotic changes in OV202 cells in the presence to BMS-536924, BMS-599626 and the combination were assessed by nuclear morphology in blinded fashion. At doses of BMS-536924 or BMS-599626 that lead to relatively small amounts of apoptosis alone, the combination generated a large degree of apoptosis. The enhancement of apoptosis was apparent at 24 hours (Fig 4, A). Evaluation of apoptosis using nuclear morphology was repeated in SKOV3.ip1 cells, which also showed a profound anti-proliferative effect of combination treatment compared to the single agents at the 75% fraction affected (Fig 4, B). Similar to OV202 cells, substantial nuclear apoptotic morphology was seen in SKOV3.ip1 cells treated with the combination of BMS-536924 and BMS-599626 (Fig 4, C, D). While the single agent exposures to BMS-536924 and BMS-599626 were anti-proliferative, only modest apoptotic effect was observed upon treatment for up to 5 days (Fig 4, A,C,D).

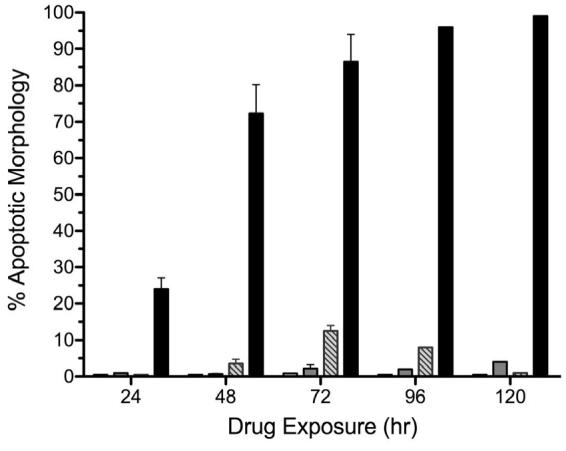

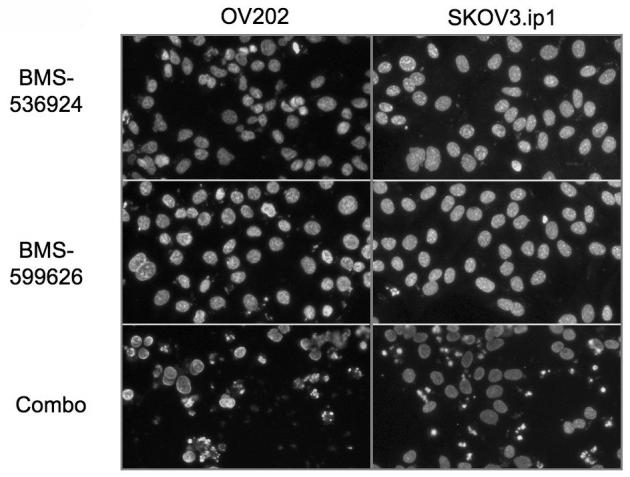

Figure 4. Combined treatment with BMS-536924 and BMS-599626 induce apoptosis in ovarian cancer cells.

OV202 cells (A) or SKOV3.ip1 cells (C) were treated with either DMSO (white bars), BMS-536924 (light gray bars), BMS-599626 (striped bars) or the combination (black bars) at IC50 concentrations (Suppl. Table 1) at time points indicated. Apoptosis was assessed as described in methods. B) Antiproliferative effects of BMS-536924 (  ), BMS-599626 (

), BMS-599626 (  ) and the combination (

) and the combination ( ) in SKOV3.ip1 cells. Error bars represent standard deviation (n=3). D) OV202 and SKOV3.ip1 cells were stained with Hoechst 33258 at 0.5 μg/ml after treatment with either BMS-536924, BMS-599626, or the combination at the IC50 concentrations (Suppl. Table 1). Images are representative fields of three replicate experiments.

) in SKOV3.ip1 cells. Error bars represent standard deviation (n=3). D) OV202 and SKOV3.ip1 cells were stained with Hoechst 33258 at 0.5 μg/ml after treatment with either BMS-536924, BMS-599626, or the combination at the IC50 concentrations (Suppl. Table 1). Images are representative fields of three replicate experiments.

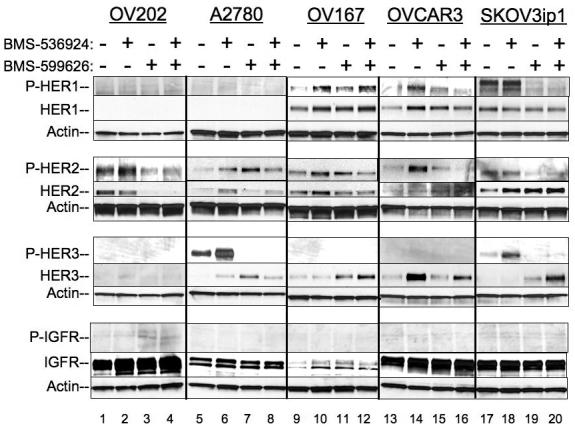

Reciprocal HER receptor activation with IGF-1R inhibition can be inhibited by HER TKI

Based on our initial observation of reciprocal receptor phosphorylation in OV202 cells, we hypothesized that receptor expression and/or phosphorylation modulation occurred in the five ovarian cancer cell lines that demonstrated synergistic anti-proliferative activity with BMS-536924 and BMS-599626. The five ovarian cancer cell lines were treated with either DMSO, BMS-536924 at the IC50 concentration, BMS-599626 at the IC50 concentration or the combination for 24 hours (Fig 5). Following treatment, cellular lysates were analyzed by western blotting for total and phosphorylation forms of the HER and IGF-1 system receptors. Upon treatment of cells with BMS-536924, all 5 ovarian cancer cells lines demonstrated evidence of increased HER receptor signaling activity (Fig 5, lanes 2,6,10,14,18). The specific HER receptor signaling changes that occurred varied by cell type. In all ovarian cell lines, this HER receptor signaling increase was blocked by BMS-599626 (Fig 5, lanes 3,7,11,15,19). All ovarian cell lines had very low expression and no detectable activation of HER4/erbB4 by western blotting (data not shown). Of note, in contrast to changes seen in 1 hour with BMS-599626 treatment in OV202 cells (Fig 1, lane 7), there were no changes in IGF-1R total or activated receptors in the ovarian cancer cell lines tested in response to treatment with BMS-599626 for 24 hours, with the exception of OV202 cells (Fig 5, lane 3). These data suggest that IGF-1R/InsR inhibition can stimulate increased HER receptor signaling in ovarian cancer cells.

Figure 5. HER receptor modulation in ovarian cancer cells in response to BMS-536924 and BMS-599626 treatment.

Ovarian cancer cells were treated with either DMSO, or the IC50 concentrations (Suppl. Table 1) of BMS-536924, BMS-599626 or the combination for 24 hours. Cells were then harvest for lysates and analyzed by western blotting for total and activated HER receptors or IGF-1R , as described in the methods.

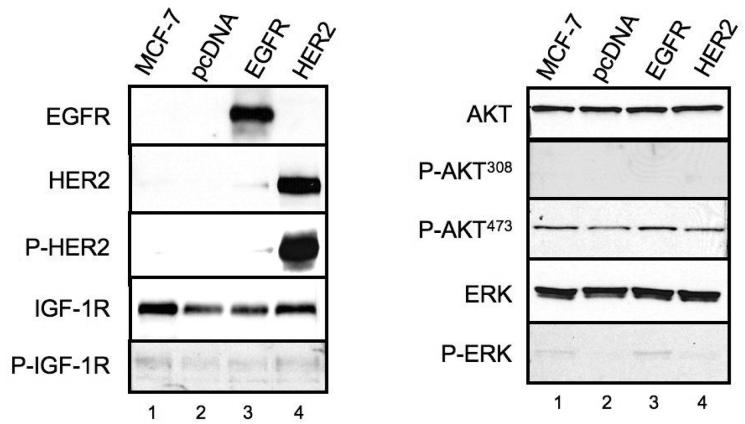

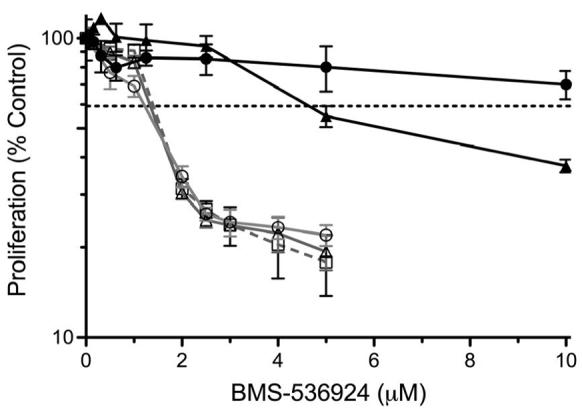

Activated HER receptor expression is sufficient to cause resistance to BMS-536924

Based on the above observations of functional IGF-1R and HER receptor crosstalk and data suggesting IGF-1R can confer resistance to HER targeted therapy, we hypothesized that HER receptors could confer resistance to IGF-1R targeted therapy. As our ovarian cancer cell lines had detectable expression of HER protein receptors and only relatively moderate sensitivity to IGF-1R inhibition as a single agent, we investigated the activity of BMS-536924 in the breast cancer cell line, MCF-7. MCF-7 parental cells were relatively sensitive to BMS-536924 and have no detectable expression of HER1 or HER2 (Fig 6, A). MCF-7 variants were constructed, which contained either an empty mammalian expression vector (MCF-7/pcDNA), the vector containing the full-length, wild-type EGF receptor (MCF-7/EGFR) or the vector containing the full-length, wild-type HER2 receptor (MCF-7/HER2). Western blot analysis of whole cells lysate from untransfected MCF-7 and stably-transfected MCF-7/pcDNA, MCF-7/EGFR and MCF-7/HER2 was performed (Fig 6, A). MCF-7 and MCF-7/pcDNA cells had no detectable expression of EGFR or HER2. However, MCF-7/EGFR cells contained high levels of EGFR and MCF-7/HER2 cells contained high levels of HER2. HER2 was activated in MCF-7/HER2 cells as demonstrated by constitutive phosphorylation. Transfection of MCF-7 cells with vectors expressing either EGFR or HER2 has no apparent effect of the expression levels of total or activated IGF-1R. Additionally, there were no apparent differences in total or activated AKT or ERK expression in all four cell lines.

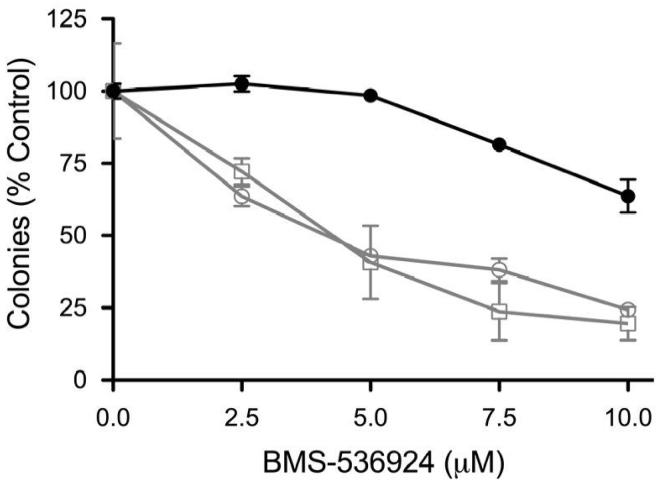

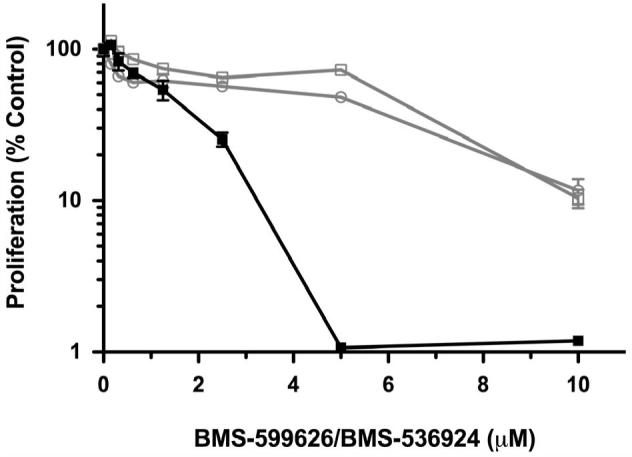

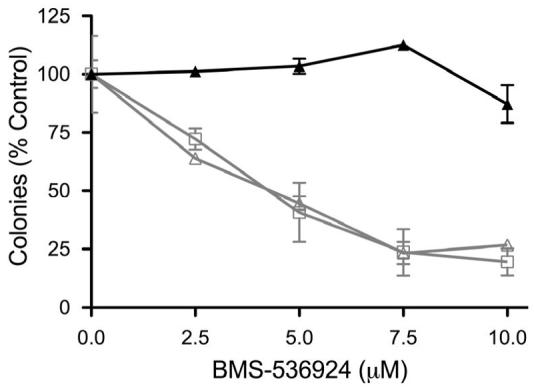

Figure 6. Activated HER receptors are sufficient for resistance to IGF-1R/InsR targeted therapy.

A) Parental MCF-7 cells (MCF-7) and stable transfectants expressing either empty vector (pcDNA) or vector containing wild-type HER1 (EGFR) or wild-type HER2 (HER2) were grown to near confluency and analyzed by western blotting as described in methods. The variants (pcDNA- ; EGFR-

; EGFR- ; HER2-

; HER2- ) were then treated with various doses of BMS-536924 for 72 hours in the absence or presence of EGF (100 ng/ml-

) were then treated with various doses of BMS-536924 for 72 hours in the absence or presence of EGF (100 ng/ml-  ) or heregulin (10 ng/ml-

) or heregulin (10 ng/ml-  ) as indicated. Proliferation (B) and clonogenicity (C, D) were assessed by MTS and clonogenic assays as described in the methods. Error bars represent standard deviation.

) as indicated. Proliferation (B) and clonogenicity (C, D) were assessed by MTS and clonogenic assays as described in the methods. Error bars represent standard deviation.

To determine whether HER receptor expression was sufficient for conferring resistance to IGF-1R targeted therapy, we performed a proliferation assay on MCF-7 cells stably transfected with pcDNA, EGFR or HER2. In the absence of ligands, the anti-proliferative effects of BMS-536924 were similar in all transfected cell lines (Fig 6, B). However, the addition of EGF or heregulin, which have little proliferative effects on MCF-7 cells (data not shown), was sufficient to confer a high level of resistance in MCF-7/EGFR and MCF-7/HER2 cells, respectively. Furthermore, the addition of EGF to MCF-7/EGFR cells and heregulin to MCF-7/HER2 cells greatly reduced the ability of BMS-536924 to prevent MCF-7 variant colony formation (Fig. 6, C and D). These data suggest that activated EGFR and HER2-heterodimer signaling, but not unstimulated EGFR or constitutively activated HER2 alone, can confer high levels of resistance to IGF-1R/InsR inhibition.

Discussion

We have demonstrated for the first time that blockade of the IGF-1R and InsR with a small molecule tyrosine kinase inhibitor stimulates crosstalk signaling through the activation of the HER family of receptors. In a reciprocal fashion, inhibition of HER2 stimulates phosphorylation of IGF-1R/InsR. Others have previously demonstrated that the IGF-1R can potentially provide a mechanism of resistance to therapy targeting the HER-family members, EGFR and HER2(8, 9, 27-31). These findings have supported the clinical development of therapies targeting the IGF-1R as a potential therapeutic strategy for overcoming or blocking IGF-1R-dependent resistance. Our data indicates that the signaling crosstalk is bi-directional and can occur through the various members of the HER receptor family.

The finding that activated HER-signaling is sufficient to confer resistance to BMS-536924 has clear clinical implications. HER2 overexpression is present and drives tumor proliferation and prosurvival signaling in 25% of breast cancers and confers a poor prognosis(40). EGFR overexpression and activating mutations are present in a significant number of non-small cell lung, head and neck, colon and pancreatic cancers, which contributes to their tumorigenicity(41). The EGFR/HER2 status of these tumors may be critical to determining their sensitivity to IGF-1R inhibition. Since HER2 autophosphorylation is ligand-independent, it was somewhat surprising that MCF-7/HER2 cells alone were not resistant to BMS-536924. However, HER2 homodimers in the absence of stimulatory ligands, such as heregulin, do not have access to the increase repertoire of adapter and intrasignaling molecules that heterodimers, such as HER2/HER3 (42, 43) do. Although HER3 does not have a kinase domain, its cross-phosphorylation by other member of the HER-family of receptors at residues with the YXXM motif, including tyrosine 1289, stimulates PI3 kinase signaling(44). It is believed that the enhanced networking potential of HER2-containing heterodimers explains their increased tumorigenicity compared to HER2 homodimers(42). In our model, it appears that it is this level of HER receptor signaling that is required to overcome sensitivity to BMS-536924. Indeed, it may be that evaluation of HER3 or heregulin in the presence of HER2, may be important for predicting sensitivity.

The combined effects of IGF-1R/InsR and panHER inhibition demonstrate that co-targeting both pathways is sufficient to cause a large degree of apoptotic cell death. These finding would suggest that either the IGF-1 or HER family pathway is critical for ovarian cancer survival. While, BMS-536924 and BMS-599626 had antiproliferative activity in the ovarian cancer cell lines tested, they had no substantial apoptotic activity as single agents, compared to DMSO-treated controls. Additionally, upregulation of the HER-family of receptor signaling demonstrates the dynamic nature of receptor expression and how they may be modulated by targeted therapy, such as BMS-536924. Given these data, it not surprising that agents targeting single members the HER-family of receptors have shown disappointing clinical activity in ovarian cancer(45, 46). In the ovarian cancer models we have tested, substantial apoptosis was only seen after complete blockade of the IGF and HER signaling pathways.

In summary these data, as well as data from others, suggest bi-directional functional crosstalk between the IGF and HER family of receptors. Our findings support the hypothesis that HER-receptor family signaling can provide a resistance mechanism for agents targeting the IGF-1R that are currently in phase I/II and III.. As simultaneous inhibition of both the IGF-1 and HER pathways disrupts this adaptive crosstalk mechanism, our data suggests that simultaneous treatment with HER and IGF-1R inhibitors may be more effective than either alone. Additionally, our results would support the notion that patients developing resistance to HER1- or HER2- targeted therapy may become re-sensitized by continuing the HER-targeted agents in combination with IGF-1R inhibitors.

Acknowledgments

Supported in part by the Mayo Clinic Breast SPORE (CA116201-01), NIH K12 (CA090628-05) the Fred C. and Katherine B. Andersen Foundation and the Mayo Clinic Cancer Center (CA15083).

Abbreviations List

- EGF

epidermal growth factor

- EGFR

EGF receptor

- HER

human EGF receptor

- IGF-1

insulin like growth factor 1

- IGF-1R

IGF-1 receptor

- IGFBP

IGF binding proteins

- IGF-1Rmab

monoclonal antibodies targeting IGF-1R

- TKI

tyrosine kinase inhibitors

References

- 1.Le Roith D. Seminars in medicine of the Beth Israel Deaconess Medical Center. Insulin-like growth factors. N Engl J Med. 1997;336:633–40. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199702273360907. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Pollak MN, Schernhammer ES, Hankinson SE. Insulin-like growth factors and neoplasia. Nat Rev Cancer. 2004;4:505–18. doi: 10.1038/nrc1387. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Hankinson SE, Willett WC, Colditz GA, et al. Circulating concentrations of insulin-like growth factor-I and risk of breast cancer. Lancet. 1998;351:1393–6. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(97)10384-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Stattin P, Bylund A, Rinaldi S, et al. Plasma insulin-like growth factor-I, insulin-like growth factor-binding proteins, and prostate cancer risk: a prospective study. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2000;92:1910–7. doi: 10.1093/jnci/92.23.1910. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Wei EK, Ma J, Pollak MN, et al. A prospective study of C-peptide, insulin-like growth factor-I, insulin-like growth factor binding protein-1, and the risk of colorectal cancer in women. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2005;14:850–5. doi: 10.1158/1055-9965.EPI-04-0661. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Abe S, Funato T, Takahashi S, et al. Increased expression of insulin-like growth factor i is associated with Ara-C resistance in leukemia. Tohoku J Exp Med. 2006;209:217–28. doi: 10.1620/tjem.209.217. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Allen GW, Saba C, Armstrong EA, et al. Insulin-like growth factor-I receptor signaling blockade combined with radiation. Cancer Res. 2007;67:1155–62. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-06-2000. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Camirand A, Lu Y, Pollak M. Co-targeting HER2/ErbB2 and insulin-like growth factor-1 receptors causes synergistic inhibition of growth in HER2-overexpressing breast cancer cells. Med Sci Monit. 2002;8:BR521–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Desbois-Mouthon C, Cacheux W, Blivet-Van Eggelpoel MJ, et al. Impact of IGF-1R/EGFR cross-talks on hepatoma cell sensitivity to gefitinib. Int J Cancer. 2006;119:2557–66. doi: 10.1002/ijc.22221. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Gee JM, Robertson JF, Gutteridge E, et al. Epidermal growth factor receptor/HER2/insulin-like growth factor receptor signalling and oestrogen receptor activity in clinical breast cancer. Endocr Relat Cancer. 2005;12(Suppl 1):S99–S111. doi: 10.1677/erc.1.01005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Knowlden JM, Hutcheson IR, Barrow D, Gee JM, Nicholson RI. Insulin-like growth factor-I receptor signaling in tamoxifen-resistant breast cancer: a supporting role to the epidermal growth factor receptor. Endocrinology. 2005;146:4609–18. doi: 10.1210/en.2005-0247. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Wan X, Helman LJ. Effect of insulin-like growth factor II on protecting myoblast cells against cisplatin-induced apoptosis through p70 S6 kinase pathway. Neoplasia. 2002;4:400–8. doi: 10.1038/sj.neo.7900242. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Wiseman LR, Johnson MD, Wakeling AE, Lykkesfeldt AE, May FE, Westley BR. Type I IGF receptor and acquired tamoxifen resistance in oestrogen-responsive human breast cancer cells. Eur J Cancer. 1993;29A:2256–64. doi: 10.1016/0959-8049(93)90218-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Yin D, Tamaki N, Parent AD, Zhang JH. Insulin-like growth factor-I decreased etoposide-induced apoptosis in glioma cells by increasing bcl-2 expression and decreasing CPP32 activity. Neurol Res. 2005;27:27–35. doi: 10.1179/016164105X18151. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kurmasheva RT, Houghton PJ. IGF-I mediated survival pathways in normal and malignant cells. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2006;1766:1–22. doi: 10.1016/j.bbcan.2006.05.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Samani AA, Yakar S, Leroith D, Brodt P. The Role of the IGF System in Cancer Growth and Metastasis: Overview and Recent Insights. Endocr Rev. 2007;28:20–47. doi: 10.1210/er.2006-0001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Frasca F, Pandini G, Scalia P, et al. Insulin receptor isoform A, a newly recognized, high-affinity insulin-like growth factor II receptor in fetal and cancer cells. Mol Cell Biol. 1999;19:3278–88. doi: 10.1128/mcb.19.5.3278. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Pandini G, Frasca F, Mineo R, Sciacca L, Vigneri R, Belfiore A. Insulin/insulin-like growth factor I hybrid receptors have different biological characteristics depending on the insulin receptor isoform involved. J Biol Chem. 2002;277:39684–95. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M202766200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Devi GR, De Souza AT, Byrd JC, Jirtle RL, MacDonald RG. Altered ligand binding by insulin-like growth factor II/mannose 6-phosphate receptors bearing missense mutations in human cancers. Cancer Res. 1999;59:4314–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Firth SM, Baxter RC. Cellular actions of the insulin-like growth factor binding proteins. Endocr Rev. 2002;23:824–54. doi: 10.1210/er.2001-0033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Zhang H, Yee D. The therapeutic potential of agents targeting the type I insulin-like growth factor receptor. Expert Opin Investig Drugs. 2004;13:1569–77. doi: 10.1517/13543784.13.12.1569. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Haluska P, Shaw HM, Batzel GN, et al. Phase I dose escalation study of the anti insulin-like growth factor-I receptor monoclonal antibody CP-751,871 in patients with refractory solid tumors. Clin Cancer Res. 2007;13:5834–40. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-07-1118. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Haluska P, Carboni JM, Loegering DA, et al. In vitro and in vivo antitumor effects of the dual insulin-like growth factor-I/insulin receptor inhibitor, BMS-554417. Cancer Res. 2006;66:362–71. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-05-1107. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Mitsiades CS, Mitsiades NS, McMullan CJ, et al. Inhibition of the insulin-like growth factor receptor-1 tyrosine kinase activity as a therapeutic strategy for multiple myeloma, other hematologic malignancies, and solid tumors. Cancer Cell. 2004;5:221–30. doi: 10.1016/s1535-6108(04)00050-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Vasilcanu D, Girnita A, Girnita L, Vasilcanu R, Axelson M, Larsson O. The cyclolignan PPP induces activation loop-specific inhibition of tyrosine phosphorylation of the insulin-like growth factor-1 receptor. Link to the phosphatidyl inositol-3 kinase/Akt apoptotic pathway. Oncogene. 2004;23:7854–62. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1208065. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Wittman M, Carboni J, Attar R, et al. Discovery of a (1H-benzoimidazol-2-yl)-1H-pyridin-2-one (BMS-536924) inhibitor of insulin-like growth factor I receptor kinase with in vivo antitumor activity. J Med Chem. 2005;48:5639–43. doi: 10.1021/jm050392q. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Jones HE, Goddard L, Gee JM, et al. Insulin-like growth factor-I receptor signalling and acquired resistance to gefitinib (ZD1839; Iressa) in human breast and prostate cancer cells. Endocr Relat Cancer. 2004;11:793–814. doi: 10.1677/erc.1.00799. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Lu Y, Zi X, Pollak M. Molecular mechanisms underlying IGF-I-induced attenuation of the growth-inhibitory activity of trastuzumab (Herceptin) on SKBR3 breast cancer cells. Int J Cancer. 2004;108:334–41. doi: 10.1002/ijc.11445. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Morgillo F, Kim WY, Kim ES, Ciardiello F, Hong WK, Lee HY. Implication of the insulin-like growth factor-IR pathway in the resistance of non-small cell lung cancer cells to treatment with gefitinib. Clin Cancer Res. 2007;13:2795–803. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-06-2077. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Nahta R, Yuan LX, Zhang B, Kobayashi R, Esteva FJ. Insulin-like growth factor-I receptor/human epidermal growth factor receptor 2 heterodimerization contributes to trastuzumab resistance of breast cancer cells. Cancer Res. 2005;65:11118–28. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-04-3841. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Lee AV, Cui X, Oesterreich S. Cross-talk among estrogen receptor, epidermal growth factor, and insulin-like growth factor signaling in breast cancer. Clin Cancer Res. 2001;7:4429s–35s.; discussion 11s-12s.

- 32.Conover CA, Hartmann LC, Bradley S, et al. Biological characterization of human epithelial ovarian carcinoma cells in primary culture: the insulin-like growth factor system. Exp Cell Res. 1998;238:439–49. doi: 10.1006/excr.1997.3861. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Chou TC, Talalay P. Quantitative analysis of dose-effect relationships: the combined effects of multiple drugs or enzyme inhibitors. Adv Enzyme Regul. 1984;22:27–55. doi: 10.1016/0065-2571(84)90007-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Erlichman C, Boerner SA, Hallgren CG, et al. The HER tyrosine kinase inhibitor CI1033 enhances cytotoxicity of 7-ethyl-10-hydroxycamptothecin and topotecan by inhibiting breast cancer resistance protein-mediated drug efflux. Cancer Res. 2001;61:739–48. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.McCollum AK, Teneyck CJ, Sauer BM, Toft DO, Erlichman C. Up-regulation of heat shock protein 27 induces resistance to 17-allylamino-demethoxygeldanamycin through a glutathione-mediated mechanism. Cancer Res. 2006;66:10967–75. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-06-1629. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Lai JP, Chien JR, Moser DR, et al. hSulf1 Sulfatase promotes apoptosis of hepatocellular cancer cells by decreasing heparin-binding growth factor signaling. Gastroenterology. 2004;126:231–48. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2003.09.043. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Kalli KR, Falowo OI, Bale LK, Zschunke MA, Roche PC, Conover CA. Functional insulin receptors on human epithelial ovarian carcinoma cells: implications for IGF-II mitogenic signaling. Endocrinology. 2002;143:3259–67. doi: 10.1210/en.2001-211408. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Wong TW, Lee FY, Yu C, et al. Preclinical antitumor activity of BMS-599626, a pan-HER kinase inhibitor that inhibits HER1/HER2 homodimer and heterodimer signaling. Clin Cancer Res. 2006;12:6186–93. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-06-0642. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Wittman MD, Balasubramanian B, Stoffan K, et al. Novel 1H-(benzimidazol-2-yl)-1H-pyridin-2-one inhibitors of insulin-like growth factor I (IGF-1R) kinase. Bioorg Med Chem Lett. 2007;17:974–7. doi: 10.1016/j.bmcl.2006.11.041. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Slamon DJ, Godolphin W, Jones LA, et al. Studies of the HER-2/neu proto-oncogene in human breast and ovarian cancer. Science. 1989;244:707–12. doi: 10.1126/science.2470152. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Ciardiello F, Tortora G. EGFR antagonists in cancer treatment. N Engl J Med. 2008;358:1160–74. doi: 10.1056/NEJMra0707704. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Citri A, Skaria KB, Yarden Y. The deaf and the dumb: the biology of ErbB-2 and ErbB-3. Exp Cell Res. 2003;284:54–65. doi: 10.1016/s0014-4827(02)00101-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Holbro T, Beerli RR, Maurer F, Koziczak M, Barbas CF, 3rd, Hynes NE. The ErbB2/ErbB3 heterodimer functions as an oncogenic unit: ErbB2 requires ErbB3 to drive breast tumor cell proliferation. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2003;100:8933–8. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1537685100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Kim HH, Sierke SL, Koland JG. Epidermal growth factor-dependent association of phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase with the erbB3 gene product. J Biol Chem. 1994;269:24747–55. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Bookman MA, Darcy KM, Clarke-Pearson D, Boothby RA, Horowitz IR. Evaluation of monoclonal humanized anti-HER2 antibody, trastuzumab, in patients with recurrent or refractory ovarian or primary peritoneal carcinoma with overexpression of HER2: a phase II trial of the Gynecologic Oncology Group. J Clin Oncol. 2003;21:283–90. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2003.10.104. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Posadas EM, Liel MS, Kwitkowski V, et al. A phase II and pharmacodynamic study of gefitinib in patients with refractory or recurrent epithelial ovarian cancer. Cancer. 2007;109:1323–30. doi: 10.1002/cncr.22545. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]