Abstract

Objectives

Geriatric diabetes care guidelines recommend that treatment intensity be based on patient preferences and clinical criteria such as limited life expectancy and functional decline (i.e., vulnerability). We assessed whether patient perceptions of diabetes treatments differed by vulnerability.

Design

Cross-sectional survey

Setting

Clinics affiliated with two Chicago-area hospitals

Participants

Patients 65 and over, living with type 2 diabetes (N=332).

Measurements

We assessed utilities, preference ratings on a scale from 0 to 1, for nine treatment states using time trade-off questions and queried patients about specific concerns regarding medications. Vulnerability was defined by the Vulnerable Elders Scale.

Results

One third (36%) of patients were vulnerable. Vulnerable patients were older (77 vs. 73 years of age) and had a longer duration of diabetes (13 vs. 10 years) (p’s < 0.05). Vulnerable patients reported lower utilities than non-vulnerable patients for most individual treatment states (e.g., Intensive Glucose Control, mean 0.61 vs. 0.72, p<0.01) but within group variation was large for both groups (e.g., standard deviations >0.25). While mean individual state utilities differed across groups, we found no significant differences in how vulnerable and non-vulnerable patients compared intensive and conventional treatment states (e.g., Intensive versus Conventional Glucose Control). In multivariable analyses, the association between vulnerability and individual treatment state utilities became non-significant except for the cholesterol pill.

Conclusions

Older patients’ preferences for diabetes treatment intensity vary widely and are not closely associated with vulnerability. This observation underscores the importance of involving older patients in diabetes treatment decisions, irrespective of clinical status.

Keywords: Diabetes mellitus, treatments, quality of life, patient preferences, aging

Introduction

Current diabetes guidelines recommend that patients maintain a glycosylated hemoglobin (HbA1C) of less than 7%1, a blood pressure of below 130/80 mm Hg2, and an LDL of less than 100 mg/dl3 in order to minimize the risk of developing microvascular4 and cardiovascular complications.5, 6 The achievement and maintenance of these risk factor goals often requires an increasing number of medications over the duration of a patient’s disease.7 The pursuit of these goals has come to define modern comprehensive diabetes care.8

While comprehensive diabetes care has the potential to benefit the general population of patients living with diabetes, there are specific concerns regarding the applicability of goals developed for the general population to the diverse group of patients over the age of 65 years. Many older patients may benefit from intensive, comprehensive diabetes care; however, older patients at high risk for mortality or functional decline may not benefit substantially from intensively pursuing glucose control. The United Kingdom Prospective Diabetes Study (UKPDS) showed that the benefits of maintaining these lower glucose control levels may take seven or more years to accrue,9 which suggests that older patients must have a minimum level of life expectancy in order to benefit from intensive glucose control. There is additional concern that intensive and comprehensive diabetes care may be harmful in some older patients. Taking multiple medications, in and of itself, has been shown to increase the risk of side effects or adverse drug events; and maintaining lower risk factor levels is associated with side effects such as hypoglycemia10 and falls.11 Apart from adverse drug events, the very medications used as part of comprehensive diabetes care may represent a quality of life burden for many older patients.12–14 In light of these concerns, it has been increasingly recognized that the goals of diabetes care must be carefully tailored to the clinical context, health care goals, and treatment preferences of the individual older patients.15, 16

In 2003, the California Healthcare Foundation/American Geriatric Society Panel on Improving Care for Elders with Diabetes developed care guidelines to assist providers in individualizing care for older patients.17 Since their publication, these guidelines have been endorsed and adopted by the American Diabetes Association.18 A centerpiece of the guidelines is the stratification of care goals and treatments between older patients who might not benefit from general population treatment goals (HbA1C <7%) from those older patients who would. An underlying theme of the guidelines is that providers should elicit and incorporate patient preferences in treatment decisions.

Providers attempting to implement these guideline recommendations must integrate both clinical criteria used to stratify patients and patients’ treatment preferences. The ease with which this integration process takes place depends on the extent to which clinical criteria correspond with patients’ preferences. Consider the clinical criterion of clinical vulnerability, defined as limited life expectancy combined with a high risk of functional decline.19 Clinically vulnerable patients, by virtue of their more complex medical histories, may have a stronger preference against the intensification of diabetes treatments compared to non-vulnerable patients. If there is a close correspondence of clinical vulnerability and preferences, it may be possible to utilize clinical status as initial proxy for patients’ treatment preferences. On the other hand, if there is not a close correspondence, there may actually be significant conflicts between clinical recommendations based on clinical criteria and patients’ preferences that must be resolved.20 Some clinically vulnerable patients may desire to pursue intensive diabetes care, despite a low likelihood of benefits. The converse of this conflict would be the observation of non-vulnerable patients rejecting intensive diabetes care, despite a higher likelihood of benefits.

To date, there has been limited research attempting to ascertain patients’ perceptions of the quality of life burdens of comprehensive diabetes care.13 The goal of our study was to determine whether patient preferences for diabetes-related treatments corresponded with clinical vulnerability. We anticipated that while patients would be heterogeneous in their views about medications, vulnerable patients would be more likely to view intensive diabetes therapies negatively compared to non-vulnerable patients.

Methods

From May 2004 to May 2006, we conducted face-to-face interviews with patients, 18 and older, living with diabetes, attending clinics affiliated with an academic medical center (University of Chicago, Chicago, IL) and physician offices affiliated with a suburban hospital (MacNeal Hospital, Berwyn, IL). We identified patients using electronic billing data provided by the clinics. Patients were included if they had an ICD-9 billing code of 250.xx in the past year and were 18 years of age or older. Physicians at each clinic approved which patients we were permitted to contact. We excluded patients with type 1 diabetes, as well as those who had dementia, or who scored less than 17 points on the mini mental status examination.21 We then selected a random sample of patients to whom we sent recruitment letters, which were followed with up to four telephone calls. For the purposes of this study we focus on the subpopulation of patients who were 65 years or over. During the course of study recruitment, we successfully contacted 1,077 eligible patients over 65 years of age and scheduled interviews with 415 patients. 332 patients (31% of eligible patients) successfully completed the study. The average age and the location of residences by ZIP code of subjects who completed interviews did not differ from that of other eligible patients. Subjects who completed interviews were more likely to be male than other eligible patients (p=0.05).

The face-to-face interviews took approximately one hour and were conducted by trained interviewers in either English or Spanish at the patient’s doctor’s office. Patients could schedule an interview either with or independently of an appointment with their doctor, and were paid $20 for their time. During interviews, we elicited patients’ perceptions of quality of life with nine separate diabetes treatments using time trade-off questions.22 We also elicited patients’ perceptions of multiple complication states related to diabetes. For this manuscript, we chose to focus on the treatment states given their significant impact in prior cost-effectiveness analyses, over and above the impact of complication states.14 Time trade-off questions are one method for eliciting utilities, which are quantitative measures of preference on a 0 to 1 scale where 0 represents a state equivalent to death and 1 represents life in perfect health. Utilities are used in cost-effectiveness analyses to quantify quality of life effects of treatments and complications.23 For each scenario, we described a treatment state, and asked patients to consider how it would affect their day-to-day lives. Patients were then asked whether they would prefer to live 10 years on the treatment, or a shorter period of time in perfect health. In a series of questions using the ping-pong method, the time in perfect health was reduced until the patient was indifferent between the two choices or chose life with the treatment. In order to minimize the effects of subject fatigue and order response bias, the order in which patients heard about conventional (e.g., conventional glucose control) and intensive treatment states (e.g., intensive glucose control) was randomly allocated.

Treatments assessed included Aspirin, Cholesterol Pill, Intensive and Conventional Glucose Control, Intensive and Conventional Blood Pressure Control, Comprehensive Diabetes Care, Comprehensive Care with PolyPill, Diet therapy, and Exercise therapy. Descriptions of treatments included the method of treatment delivery (i.e., oral agents/injection/both), associated laboratory testing, and the likelihood of side effects. We told patients that if they were to experience side effects, their physician would discontinue that medication and find an alternative treatment. For Intensive and Conventional Glucose Control, we described the treatment protocols of patients in UKPDS.9 Patients in the intensive control arm were more likely to take multiple oral agents and insulin over the course of their disease in order to achieve a HbA1C less than 7%, while those in the conventional control arm were more likely to receive oral agents only in order to reach a HbA1C target of less than 8%. The likelihood of side effects such as hypoglycemic episodes and upset stomach were compared between intensive and conventional treatments. Patients were also told they would be expected to follow a diabetic diet, to exercise, and to check their blood sugar. In a similar fashion, for intensive and conventional blood pressure control, we described the treatment protocols of patients in the blood pressure trial of the UKPDS.24 Patients were told that with Intensive Blood Pressure Control they would be more likely to be placed on three to four blood pressure agents in comparison to Conventional Blood Pressure Control. For the remaining treatment states, we used data from the medical literature to develop treatment state descriptions (Aspirin prophylaxis25, Cholesterol lowering medication26–30, Dietary therapy31, 32 and Exercise therapy33).

Comprehensive Diabetes Care consisted of life with a combination of Cholesterol Pill, Aspirin, Intensive Blood Pressure Control, Intensive Glucose Control, Diet, and Exercise. We also asked patients to consider a state we called the Comprehensive Care with Polypill state. This state was identical to the Comprehensive Diabetes Care state except that the number of pills taken per day was reduced by the use of the Polypill. The Polypill is a proposed treatment combining an aspirin, diuretic, angiotensin converting enzyme inhibitor, beta blocker, folic acid, and a statin, reducing the number of pills taken per day34; the Polypill does not eliminate the need for glucose lowering medications or insulin.

In addition to evaluating utilities for specific diabetes related treatments, we asked patients a series of questions regarding common concerns about medication taking. This section included the perception that medication taking was unpleasant or painful, anxiety about side effects, medication cost, and doctor visits, willingness to take more medications or insulin, fear of dependency on medications or on other people, and the feeling of needing help taking medications. Responses were recorded on a five point Likert scale.

We also asked patients a variety of questions regarding their overall health status (Short Form Health Survey-1235), functional status, history of diabetes-related complications, and current medications. We examined medical records for additional clinical data on current medications, diabetes-related conditions (e.g., depression), comorbidities (Charlson Comorbidity Index36), and current risk factor levels. To assess the reliability of chart abstraction we performed a 10% re-review. The intraclass correlation coefficients for glycosylated hemoglobin, systolic blood pressure, and LDL cholesterol were 0.96, 0.81, and 0.91 respectively. The Kappa statistic for micro and cardiovascular complications of diabetes was 0.79.

Patient vulnerability was determined using the Vulnerable Elders Scale (VES-1319). Higher scores on the VES-13 are associated with a greater risk of death within the next two years and a greater risk of functional decline. As previously used, patients were defined as vulnerable if they scored three or more points on this scale. The Vulnerable Elders Scale includes self-reported health, patient age, and an assessment of activities of daily living and instrumental activities of daily living. The VES-13 was developed using the Medicare Current Beneficiary Survey19 and then validated in two managed care organizations in the United States.37 To provide additional description of the prognosis of patients, we also evaluated patients’ risk of mortality based on the Charlson Comorbidity Index36 and a 4-year mortality index.38

Statistical Analysis

All analyses were performed using SAS statistical software (Release 8.1, SAS Institute Inc., Cary, NC). We compared the mean utility scores of individual treatment states of vulnerable and non-vulnerable patients using the Wilcoxon Rank-Sum test. We similarly compared the mean differences in utility scores for intensive and conventional treatment states (i.e., glucose, blood pressure, and cholesterol control) for the two groups. For multivariable analyses of utility scores, we divided utilities into three levels (<0.2, 0.2–0.7, >0.7) based on the observed distribution of utility scores. We used ordinal logistic regression models and adjusted for gender, non-white ethnicity, education (>=high school graduate), income (<$10,000 per year), and duration of diabetes mellitus. For direct questions regarding life with medications, we dichotomized responses such that responses of “Agree Somewhat” and “Agree Strongly” were grouped together. For both unadjusted and adjusted analyses we used logistic regression. In the adjusted analyses we again accounted for gender, ethnicity, education, income and duration of diabetes. We separately considered depression as a covariate in multivariable analyses.

Results

We interviewed 332 patients, 36% of whom were vulnerable (Table 1). Vulnerable patients were significantly older (mean age, 77 versus 73 years, p<0.01), female (75% versus 49%, p<0.01) and African-American (55% versus 42%, p=0.03) compared to non-vulnerable patients. Vulnerable patients were also significantly different from non-vulnerable patients in terms of education (completed high school, 58% versus 78%) and income (income less than $10,000 per year, 33% versus 13%)(p’s<0.01).

Table 1.

Demographics and Clinical Characteristics (N=332)

| Vulnerable * (N = 118) | Non-vulnerable (N = 214) | P-Value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age, mean years (± SD,) | 77 (7) | 73 (5) | < 0.01 |

| Female, % | 75 | 49 | < 0.01 |

| Race/Ethnicity, % | |||

| African-American | 55 | 42 | 0.03 |

| Latino | 8 | 14 | 0.11 |

| Non-Hispanic White | 28 | 39 | 0.04 |

| Completed High School Education, % | 58 | 78 | < 0.01 |

| Income Under $10,000, % | 33 | 13 | < 0.01 |

| Health Insurance | |||

| Private, % | 55 | 75 | < 0.01 |

| Medicaid, % | 24 | 8 | < 0.01 |

| Duration of Diabetes, mean years (± SD) | 13 (11) | 10 (8) | 0.06 |

| Number of Medications, mean (± SD) | 8 (4) | 7 (3) | < 0.01 |

| Diet alone, % | 19 | 24 | 0.32 |

| Oral glucose lowering medications alone, % | 59 | 59 | 1.00 |

| Insulin and oral medications, % | 12 | 7 | 0.10 |

| Insulin alone, % | 9 | 10 | 0.89 |

| Charlson Comorbidity Index, mean (± SD) | 3.6 (2.2) | 2.7 (1.9) | < 0.01 |

| Diabetes-Related Complications/Conditions | |||

| Eye disease, % | 23 | 11 | < 0.01 |

| Kidney disease, % | 7 | 3 | 0.15 |

| Foot Disease (Peripheral Neuropathy and Amputation), % | 63 | 43 | < 0.01 |

| Heart disease, % | 48 | 27 | < 0.01 |

| Stroke, % | 21 | 7 | < 0.01 |

| Depression†, % | 33 | 13 | < 0.01 |

| Risk Factor Levels | |||

| HbA1c, mean (± SD) | 7.3 (1.3) | 7.1 (1.1) | 0.23 |

| HbA1c < 7%, % | 44 | 50 | 0.34 |

| Systolic blood pressure, mean mm Hg(± SD) | 138 (19) | 135 (17) | 0.07 |

| Systolic blood pressure < 130 mm Hg, % | 29 | 35 | 0.28 |

| LDL cholesterol, mean mg/dl (± SD) | 95 (37) | 91 (28) | 0.67 |

| LDL cholesterol < 100 mg/dl, % | 64 | 64 | 0.87 |

Patients classified as vulnerable if they scored 3 or more points on the Vulnerable Elders Scale.19

Patients classified as having depression if diagnosis was noted by their physician in their medical chart.

With regards to health status, vulnerable patients had a longer duration of diabetes (mean duration, 13 years versus 10 years) and more medical problems. They had a higher average Charlson Comorbity Index score36 (3.6 versus 2.7) and more diabetes-related complications/conditions including eye disease (23% versus 11%), foot disease (63% versus 43%), heart disease (48% versus 27%), and depression (22% versus 13%)(all p’s<0.01). Twenty-nine percent of vulnerable patients had a Charlson Comorbidity Index score of five or higher, denoting a risk of death in the next year of 64–100%, while only 15% of non-vulnerable patients had equivalent scores. Twenty-four percent of vulnerable patients were ill enough to have a 67% or higher risk of death in the next four years according to the four-year mortality prognostic index versus 8% of non-vulnerable patients.38 There was no difference between the two groups in the use of glucose lowering agents, cholesterol lowering agents, or aspirin, and no difference in terms of glucose, blood pressure, or cholesterol control.

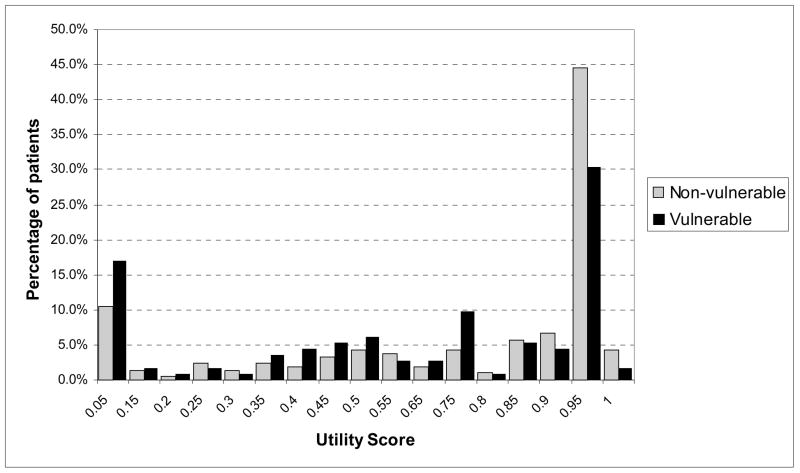

With the exception of Diet Therapy, vulnerable patients reported significantly lower utility scores than non-vulnerable patients for the majority of treatments states (Table 2). For instance, vulnerable patients had a mean utility score of 0.61 for Intensive Glucose Control while non-vulnerable patients had a mean of 0.72 (p <0.01). While there were differences across groups, there was substantial within-group variation in how patients rated each therapy, with most therapies having a standard deviation of greater than 0.25. The majority of both vulnerable and non-vulnerable patients rated most treatments at 0.95 and above. There were differences between the two groups in the distribution of utility scores (Figure 1). For Intensive Glucose Control, over half (55%) of non-vulnerable patients reported a utility score of 0.90 or greater, whereas only 37% of vulnerable patients did. On the other end of the spectrum, 12% of non-vulnerable patients reported a utility score for Intensive Glucose Control of 0.15 or less, whereas 19% of vulnerable patients did (p for difference in distributions, 0.04). Similar patterns of distributions existed for other treatment states.

Table 2.

Treatment Utilities of Vulnerable and Non-Vulnerable Older Patients, Means (± SD)*

| Treatment states | Vulnerable | Non-vulnerable | P-Value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Aspirin | 0.79 (0.28) | 0.83 (0.28) | 0.02 |

| Cholesterol lowering pill | 0.72 (0.30) | 0.83 (0.26) | < 0.01 |

| Intensive glucose control | 0.61 (0.34) | 0.72(0.32) | < 0.01 |

| Conventional glucose control | 0.71 (0.33) | 0.79 (0.28) | < 0.01 |

| Intensive blood pressure control | 0.69 (0.33) | 0.76 (0.29) | 0.04 |

| Conventional blood pressure control | 0.73 (0.32) | 0.80 (0.28) | 0.03 |

| Diet | 0.89 (0.23) | 0.90 (0.21) | 0.55 |

| Exercise | 0.85 (0.26) | 0.91 (0.19) | < 0.01 |

| Polypharmacy state | 0.58 (0.35) | 0.66 (0.32) | 0.02 |

| Polypill | 0.60 (0.34) | 0.70 (0.32) | 0.02 |

| Difference in conventional and intensive control states | |||

| Glucose control | 0.09 (0.25) | 0.07 (0.20) | 0.67 |

| Blood pressure control | 0.04 (0.15) | 0.03 (0.19) | 0.37 |

| Cholesterol control (diet and exercise versus cholesterol lowering pill) | 0.25 (0.34) | 0.19 (0.29) | 0.06 |

Utilities (preference ratings on a scale from 0 to 1) measured using time-tradeoff technique.

Patients classified as vulnerable if they scored 3 or more points on the Vulnerable Elders Scale.19

P-values reflect results from Wilcoxon Rank-Sum tests.

Figure 1.

Distribution of Utility Scores for Intensive Glucose Control Among Vulnerable and Non-Vulnerable Patients

Personal experiences with treatments were correlated with differences in patient’s perceptions of related treatment states. Patients already taking specific treatments tended to have slightly higher utility scores for related states in comparison to patients not taking those treatments. For example, non-vulnerable patients already taking aspirin had a mean utility score of 0.86 for the description of life with aspirin therapy compared to a mean score of 0.80 for those not taking aspirin (p 0.03). We found that these differences in mean scores between patients taking treatments and those not taking treatments were, for the most part, statistically significant among non-vulnerable patients, but were not statistically significant among vulnerable patients. This treatment experience phenomenon did not alter the basic differences between vulnerable and non-vulnerable patients; we found that vulnerable patients who had experience with treatments still rated related states lower than non-vulnerable patients who had not experienced the treatments.

Although vulnerable patients rated most treatment states lower than non-vulnerable patients, we did not find significant differences in how vulnerable and non-vulnerable patients compared intensive and conventional treatment states. More precisely, the mean differences in utilities for intensive and conventional treatment states (i.e., glucose, blood pressure, and cholesterol) were not statistically different for the two groups. As with the utilities for individual states, we observed variability in how patients compared treatment states of varying intensity. In the case of the comparison of intensive and conventional glucose control, 8% of non-vulnerable patients rated intensive glucose control higher than conventional glucose control, while this was true for 4% of vulnerable patients; and 26% of non-vulnerable and 22% of vulnerable patients rated conventional glucose control higher than intensive glucose control. The remaining majority of both frail and non-frail patients rated intensive and conventional glucose control the same. These distributions were not statistically different for the two groups.

Many of the differences in mean individual utility scores for vulnerable and non-vulnerable older patients also became non-significant, when we adjusted for race, education, income, gender, and duration of diabetes (Table 3). The one exception to this was the response to the question regarding cholesterol pill treatment state. Vulnerable patients were significantly less likely to give a high rating for life with a cholesterol pill compared to non-vulnerable patients (Odds Ratio (OR) 0.53, 95% Confidence Interval (CI) (0.30, 0.95)). Including physician reported depression in the models did not alter any of the findings significantly. We found that education level and income were important predictors of most utility responses. Patients who had a high school degree or greater were more than twice as likely to rate aspirin, cholesterol pill, intensive and conventional glucose control, and intensive and conventional blood pressure control favorably than those who had not finished high school. Similarly, those who had an income of less than $10,000 per year were almost twice as likely to rate Comprehensive Diabetes Care unfavorably than patients with a higher income.

Table 3.

Treatment Utilities of Vulnerable and Non-Vulnerable Older Patients, Adjusted Comparisons*

| Treatment states | OR (95% CI) for Vulnerable Variable | P-Value |

|---|---|---|

| Aspirin | 1.21 (0.65, 2.26)† | 0.55 |

| Cholesterol lowering pill | 0.53 (0.30, 0.95)† | 0.03 |

| Intensive glucose control | 0.72 (0.44, 1.18)† | 0.19 |

| Conventional glucose control | 0.87 (0.50, 1.52)† | 0.63 |

| Intensive blood pressure control | 0.82 (0.48, 1.41)† | 0.48 |

| Conventional blood pressure control | 0.87 (0.49, 1.53)† | 0.62 |

| Diet | 1.00 (0.45, 2.25)† | 0.99 |

| Exercise | 0.55 (0.26, 1.16) | 0.11 |

| Polypharmacy state | 0.76 (0.47, 1.23) ‡ | 0.26 |

| Polypill | 0.69 (0.42, 1.13) | 0.14 |

Each ordinal logistic regression model adjusted for gender, non-white ethnicity, education (>=high school graduate), income (<$10,000 per year), and duration of diabetes. OR= odds ratio, CI= confidence interval.

Presence of high school degree or greater education associated with higher utility ratings.

Income less than $10,000 per year associated with lower utility ratings.

Outside of utility scores, vulnerable patients also had significantly more concerns about various elements of medication taking than non-vulnerable patients (Table 4). They were more likely to say they worried about side effects (49% versus 38%), had trouble remembering to take their medications (42% versus 24%), or needed the help of another person in taking their medications (25% versus 12%)(all p’s<=0.05). Vulnerable patients were also more likely to report that they often felt overwhelmed after doctor’s visits (27% versus 18%, p=0.04).

Table 4.

Concerns about Medications for Vulnerable vs. Non-Vulnerable Older Patients*

| Question | Vulnerable, % | Non- vulnerable, % | Unadjusted OR(95% CI) for Vulnerable Variable | P- Value | Adjusted OR (95% CI) for Vulnerable Variable† | P-Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| I worry about side effects from my medications. | 49 | 38 | 1.58 (1.00, 2.50) | 0.05 | -- | -- |

| I worry about becoming dependent on my medications. | 53 | 42 | 1.52 (0.97, 2.39) | 0.07 | -- | -- |

| I sometimes have difficulty remembering to take my medications. | 42 | 24 | 2.21 (1.37, 3.59) | <0.01 | 2.17 (1.28, 3.70) | < 0.01 |

| I could use another person’s help taking my medications. | 25 | 12 | 2.43 (1.35, 4.35) | <0.01 | 2.15 (1.14, 4.06) | 0.02 |

| I find taking my pills unpleasant or painful. | 16 | 8 | 2.32 (1.14, 4.70) | 0.02 | 2.11 (0.98, 4.54) | 0.06 |

| I find taking my insulin unpleasant or painful. (n=73) | 51 | 24 | 3.41 (1.25, 9.27) | 0.02 | 4.12 (1.23, 13.78) ‡ | 0.02 |

| I often come away from a doctor’s visit feeling overwhelmed with new things to do. | 27 | 18 | 1.74 (1.02, 2.98) | 0.04 | 1.43 (0.79, 2.58) | 0.24 |

| I worry about switching from name brand to generic drugs. | 31 | 22 | 1.60 (0.96, 2.67) | 0.07 | -- | -- |

| If your doctor told you that you would benefit from taking more medications, would you be willing to? | 77 | 86 | 0.57 (0.32,1.00) | 0.05 | -- | -- |

| If your doctor told you that you would benefit from taking insulin, would you be willing to? (n=258) | 59 | 72 | 0.55 (0.31 - 0.94) | 0.03 | 0.65 (0.36, 1.17) | 0.15 |

Percentages reflect percentage of patients responding “Agree Somewhat” and “Agree Strongly” to statements. Patients classified as vulnerable if they scored 3 or more points on the Vulnerable Elders Scale.19 Unadjusted comparisons performed using logistic regression. OR= odds ratio, CI= confidence interval.

Each logistic regression model adjusted for gender, non-white ethnicity, education (>=high school graduate), income (<$10,000 per year), and duration of diabetes. OR= odds ratio, CI= confidence interval.

Income of less than $10,000 also significant predictor.

In terms of current and future use of medications related to diabetes, we found many significant differences between vulnerable and non-vulnerable patients. Vulnerable patients were more likely to say they found taking their pills unpleasant or painful (16% versus 8%, p=0.02). Similarly, among the patients taking insulin (N=73), vulnerable patients were significantly more likely to report finding taking their insulin unpleasant or painful (51% versus 24%, p=0.02)). For future treatment decisions, a majority of both groups of patients said that they would be willing to take additional medications if their doctor said that it would benefit them, however, vulnerable patients were still much less likely to agree to this statement (77% versus 86%, p=0.05). More specifically, among the patients not taking insulin (N=253), vulnerable patients were much less likely to report a willingness to take insulin if asked by their doctor (59% versus 72%, p=0.03).

Many of these findings remained significant even with adjustment for additional socioeconomic and demographic covariates (Table 4). Vulnerable patients were more likely to report that they sometimes forgot to take their medications (OR 2.17, 95% CI (1.28, 3.70) or that they could use help taking their medications (OR 2.15, 95% CI (1.14 - 4.06)). Vulnerable patients continued to be more likely to say that they found taking pills to be unpleasant or painful (OR 2.13 (1.00 -4.59)), although this had borderline significance, and continued to be more likely than non-vulnerable patients to find taking their insulin unpleasant or painful (OR 4.12, 95% CI (1.23 -13.78)). Notably, the association between clinical vulnerability and a future decision to take insulin became non-significant in adjusted analyses. Including depression in our analyses did not alter our findings significantly.

Discussion

Geriatric diabetes care guidelines recommend that the intensity of diabetes care be determined by a combination of clinical status measures, such as clinical vulnerability, and patient treatment preferences. This standard of care has the potential to significantly improve the quality of diabetes care and quality of life of many older patients; however, this standard may also introduce new challenges for providers as recommendations for diabetes care by clinical status may sometimes conflict with the treatment preferences of patients.20 Our study provides one of the first evaluations of how older diabetes patients’ perceptions and concerns regarding life with medications correspond with clinical status.

Our evaluation of treatment state utilities revealed more similarities between the treatment preferences of clinically vulnerable and non-vulnerable patients, than differences. For both groups, utility scores for individual treatment states varied widely, indicating significant preference heterogeneity. In addition, we found that vulnerable and non-vulnerable patients do not inherently weigh the relative quality of life effects of intensive and conventional treatment choices differently. We did find that vulnerable patients had lower mean utilities, and therefore more negative perceptions, for most diabetes treatment states compared to non-vulnerable patients. However, in adjusted analyses, these differences became non-significant when accounting for race, education, income, gender, and duration of diabetes, with the exception of cholesterol lowering therapy. Having less than a high school education, and having an income less than $10,000 per year were found to be more important predictors of reporting lower utility scores for treatment states than vulnerability. In our population, vulnerable patients were more likely to have both less education and low incomes. Less education is associated with lower health literacy39 and lower incomes are associated with more difficulties with medication costs.40 Experiences with either one of these social barriers to care may lead to negative perceptions of life with medications. The extent to which these social barriers are intertwined with clinical status and negative perceptions of life with medications presents an important challenge for efforts to individualize diabetes care for older patients.41

While we found that the association between vulnerability and treatment preferences disappeared in adjusted analyses, we found that clinically vulnerable patients had significantly more concerns about medication taking than non-vulnerable patients in both unadjusted and adjusted analyses. Many of the reported concerns of vulnerable patients in this study reflect commonly recognized problems that older patients often have with their medications, such as failing to remember to take medications. Clinically vulnerable older patients may have more difficulties taking their medications because many may have mild cognitive impairment (MCI), but not dementia. MCI may initially affect executive control and instrumental activities of daily living, without any impact on activities of daily living.42, 43 In addition to a higher frequency of reporting difficulties with medication adherence, we found that vulnerable patients were more likely to report discomfort or pain when taking pills or insulin than the non-vulnerable patients, which raises concerns about the physical burdens of everyday medications for vulnerable older patients. The contrast of this series of findings with the series of treatment preference results highlights an interesting dichotomy. Older vulnerable patients may have many more logistical and physical difficulties with their medication than their non-vulnerable counterparts; however, they may still aspire to pursuing intensive diabetes therapy, despite these difficulties.

Overall, our results lend support for the concept of individualizing diabetes care in older patients and provide insight into some of the steps that are needed to successfully implement this concept in practice. The wide variation in treatment preferences suggests that it is important for providers to actively elicit older patients’ perceptions of and preferences for intensive, comprehensive diabetes care. It cannot assumed that vulnerable older patients will necessarily desire moderate intensity of diabetes care and some may even prefer to pursue intensive therapy. At the same time, our second set of findings strongly suggest that it is equally important for providers to elicit patient concerns regarding the physical and logistical burdens of managing multiple medications, which were more common among our vulnerable patients. Each of these previously described steps mirror components of a shared decision making approach to treatment decisions. The key components of the shared decision making approach are 1) establishing an ongoing partnership between patient and provider, 2) information exchange, 3) deliberation on choices, and 4) deciding and acting on decisions.44 In the case of older diabetes patients, the shared decision making approach can be enhanced by an explicit discussion regarding the overall goals of health care and diabetes care.15, 16 In order to make actual choices regarding the medications that will be adopted, there must be an accompanying discussion regarding the likelihood that different treatment options will allow patients to achieve their stated goals.16

There are some limitations to this study. First, we used one approach to stratifying older diabetes patients (VES-13 19) when there are actually multiple overlapping clinical considerations that have been proposed including age, vulnerability, comorbid illness, functional status, and life expectancy.45 The correlation between preferences and these measures should be the subject of future research. A second limitation of our study is that the patients we surveyed may not be representative of all older patients with diabetes. We interviewed only patients who had seen a doctor in the past year. In addition, some patients may have been excluded because they were unable to get to the clinic, because they were too ill to leave the house, or because a family member told us that they were too ill to participate. It is likely that these burdens of participating in this study fell disproportionately on vulnerable patients. For the purposes of study feasibility, we also excluded patients with probable dementia. Patients with dementia comprise a significant proportion of vulnerable older patients, and the geriatric diabetes care guidelines would apply very directly to the care of such patients. For these various reasons, it is likely that the vulnerable patients we surveyed were the least disabled of this population. Nonetheless, we still found important differences in treatment experiences between vulnerable and non-vulnerable patients in our diverse sample that are likely to be applicable to many older patients.

Beyond its clinical relevance, this study has important implications for healthcare policies related to the quality of diabetes care. Pay-for-performance policies that reward providers for keeping a high proportion of their patients below nationally recommended risk-factor levels for conditions like diabetes are important for improving the overall health of the population.46 However, these policies currently do not reward providers for the time-consuming process of individualizing chronic care management which is particularly important for vulnerable, older patients with multiple chronic diseases.47 Such policies may unfairly penalize providers who have a large proportion of vulnerable older adults with diabetes and shift provider incentives away from treating such patients. Care must be taken in the design of these programs to allow for variation in treatment intensity that is clinically necessary when treating a diverse group of patients. Further research that incorporates data on patient preferences and treatment benefits will be necessary to assess the effectiveness and cost-effectiveness of individualized diabetes treatment in older adults, and to confirm the importance of the geriatric diabetes care guidelines.

Acknowledgments

This study was supported by a NIA Career Development Award (Dr. Huang, K23-AG021963), a NIDDK Midcareer Investigator Award in Patient-Oriented Research (Dr. Chin, K24 DK071933) a NIDDK Diabetes Research and Training Center (Ms. Brown, and Drs. Chin, Huang, and Meltzer, P60 DK20595), CDC-PEP (Ms. Brown, Drs. Huang, and Meltzer, U36-CCU319276), the Chicago Center of Excellence in Health Promotion Economics (Drs. Huang and Meltzer, P30-CD000147).

Footnotes

This paper was presented in part at the 2006 Annual Meeting of the American Geriatrics Society and was awarded the Best Quality of Life Poster Award.

Conflict of interest disclosures:

None of the authors have any conflicts of interest related to employment, grants, honoraria, speaker forums, consultancies, stocks, royalties, expert testimony, board membership, patents, or personal relationships.

Ms. Brown participated in acquisition of data, formulation of the analysis plan, analysis of data, interpretation of findings, and preparation of the manuscript. Dr. Meltzer contributed to overall study conception and design, interpretation of findings, and critical revision of the manuscript. Dr. Chin contributed with interpretation of findings and critical revision of the manuscript. Dr. Huang participated in the conception and design of the overall study, analysis of data, interpretation of findings, and preparation of the manuscript.

Sponsor’s role

The various funding agencies that supported this research did not participate in study design, methods, subject recruitment, data collections, analysis, or preparation of the manuscript.

| Elements of Financial/Personal Conflicts | SES Brown | DO Meltzer | MH Chin | ES Huang | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Yes | No | Yes | No | Yes | No | Yes | No | |

| Employment or Affiliation | X | X | X | X | ||||

| Grants/Funds | X | X | X | X | ||||

| Honoraria | X | X | X | X | ||||

| Speaker Forum | X | X | X | X | ||||

| Consultant | X | X | X | X | ||||

| Stocks | X | X | X | X | ||||

| Royalties | X | X | X | X | ||||

| Expert Testimony | X | X | X | X | ||||

| Board Member | X | X | X | X | ||||

| Patents | X | X | X | X | ||||

| Personal Relationship | X | X | X | X | ||||

Contributor Information

Sydney E.S. Brown, The University of Pennsylvania School of Medicine, Philadelphia, PA.

David O. Meltzer, Economics, and Public Policy The University of Chicago, Chicago, IL.

Marshall H. Chin, The University of Chicago, Chicago, IL.

Elbert S. Huang, The University of Chicago, Chicago, IL, 5841 S. Maryland Avenue, MC 2007, Chicago, IL 60637, 773-834-9143, 773-834-2238(fax), ehuang@medicine.bsd.uchicago.edu.

References

- 1.Standards of medical care in diabetes--2007. Diabetes Care. 2007;30(Suppl 1):S4–S41. doi: 10.2337/dc07-S004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Chobanian AV, Bakris GL, Black HR, et al. The seventh report of the joint national committee on prevention, detection, evaluation, and treatment of high blood pressure: the JNC 7 report. Journal of the American Medical Association. 2003;289(19):2560–72. doi: 10.1001/jama.289.19.2560. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Executive Summary of The Third Report of The National Cholesterol Education Program (NCEP) Expert Panel on Detection, Evaluation And Treatment of High Blood Cholesterol In Adults (Adult Treatment Panel III) JAMA. 2001;285(19):2486–97. doi: 10.1001/jama.285.19.2486. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Nathan DM, Singer DE, Godine JE, et al. Retinopathy in older type 2 diabetics: association with glucose control. Diabetes. 1986;35:797–801. doi: 10.2337/diab.35.7.797. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Nathan DM, Meigs JB, Singer DE. The epidemiology of cardiovascular disease in type 2 diabetes mellitus: how sweet it is ... or is it? Lancet. 1997;350(Suppl 1):S14–S9. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(97)90021-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kuller LH. Stroke and Diabetes. In: Harris MI, editor. Diabetes in America. 2. Bethesda: National Institutes of Health; 1995. pp. 449–56. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Turner RC, Cull CA, Frighi V, et al. Glycemic control with diet, sulfonylurea, metformin, or insulin in patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus: progressive requirement for multiple therapies (UKPDS 49). UK Prospective Diabetes Study (UKPDS) Group. JAMA. 1999;281(21):2005–12. doi: 10.1001/jama.281.21.2005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Gaede P, Vedel P, Larsen N, et al. Multifactorial intervention and cardiovascular disease in patients with type 2 diabetes. N Engl J Med. 2003;348(5):383–93. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa021778. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.U. K. Prospective Diabetes Study Group. Intensive blood-glucose control with sulphonylureas or insulin compared with conventional treatment and risk of complications in patients with type 2 diabetes (UKPDS 33) Lancet. 1998;352(9131):837–53. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Shorr RI, Ray WA, Daugherty JR, et al. Incidence and risk factors for serious hypoglycemia in older persons using insulin or sulfonylureas. Arch Intern Med. 1997;157(15):1681–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Tinetti ME. Clinical practice. Preventing falls in elderly persons. N Engl J Med. 2003;348(1):42–9. doi: 10.1056/NEJMcp020719. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Vijan S, Hayward RA, Ronis DL, et al. The burden of diabetes therapy: implications for the design of effective patient-centered treatment regimens. J Gen Intern Med. 2005;20:479–82. doi: 10.1111/j.1525-1497.2005.0117.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Huang ES, Brown SE, Ewigman BG, et al. Patient perceptions of quality of life with diabetes-related complications and treatments. Diabetes Care. 2007;30(10):2478–83. doi: 10.2337/dc07-0499.. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Huang ES, Jin L, Shook M, et al. The impact of patient preferences on the cost-effectiveness of intensive glucose control in older patients with new onset diabetes. Diabetes Care. 2006;29(2):259–64. doi: 10.2337/diacare.29.02.06.dc05-1443. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Huang ES, Gorawara-Bhat R, Chin MH. Self-reported goals of older patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2005;53:306–11. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2005.53119.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Huang ES. Goal setting in older adults with diabetes. In: Munshi MN, Lipsitz LA, editors. Geriatric Diabetes. New York: Informa Healthcare USA; 2007. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Brown AF, Mangione CM, Saliba D, et al. Guidlines for improving the care of the older person with diabetes mellitus. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2003;51(5 Suppl Guidelines):S265–80. doi: 10.1046/j.1532-5415.51.5s.1.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.American Diabetes Association. Standards of medical care in diabetes. Diabetes Care. 2004;27(Supplement 1):S15–S35. doi: 10.2337/diacare.27.2007.s15. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Saliba D, Elliott M, Rubenstein LV, et al. The vulnerable elders survey: a tool for identifying vulnerable older people in the community. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2001;49:1691–9. doi: 10.1046/j.1532-5415.2001.49281.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Huang ES, Gorawara-Bhat R, Chin MH. Practical challenges of individualizing diabetes care in older patients. Diabetes Educ. 2004;30(4):558–70. doi: 10.1177/014572170403000407. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Folstein MF, Folstein SE, McHugh PR. “Mini-mental state”. A practical method for grading the cognitive state of patients for the clinician. J Psychiatr Res. 1975;12(3):189–98. doi: 10.1016/0022-3956(75)90026-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Neumann PJ, Goldie SJ, Weinstein MC. Preference-based measures in economic evaluation in healthcare. Annu Rev Public Health. 2000;21:587–611. doi: 10.1146/annurev.publhealth.21.1.587. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Russell LB, Gold MR, Siegel JE, et al. The role of cost-effectiveness analysis in health and medicine. Journal of the American Medical Association. 1996;276(14):1172–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.U. K. Prospective Diabetes Study Group. Tight blood pressure control and risk of macrovascular and microvascular complications in type 2 diabetes: UKPDS 38. BMJ. 1998;317:703–13. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Gage BF, Cardinalli AB, Owens DK. Cost-effectiveness of preference-based antithrombotic therapy for patients with nonvalvular atrial fibrillation. Stroke. 1998;29:1083–91. doi: 10.1161/01.str.29.6.1083. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Downs JR, Clearfield M, Weis S, et al. Coronary events with lipid-lowering therapy: the AFCAPS/TexCAPS trial. Air Force/Texas Coronary Atherolsclerosis Prevention Study. Journal of the American Medical Association. 1998;279(20):1615–22. doi: 10.1001/jama.279.20.1615. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Prosser LA, Stinnett AA, Goldman PA, et al. Cost-effectiveness of cholesterol-lowering therapies according to selected patient characteristics. Ann Intern Med. 2000;132:769–79. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-132-10-200005160-00002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Grover S, Paquet S, Levington C, et al. Estimating the benefits of modifying risk factors of cardiovascular disease: a comparison of primary vs. secondary prevention. Arch Intern Med. 1998;158(6):655–62. doi: 10.1001/archinte.158.6.655. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Goldman L, Coxson PG, Hunink MGM, et al. The relative influence of secondary versus primary prevention using the National Cholesterol Education Program Adult Treatment Panel II guidelines. J Am Coll Cardiol. 1999;34(3):768–76. doi: 10.1016/s0735-1097(99)00260-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Ganz DA, Kuntz KM, Jacobson GA, et al. Cost-effectiveness of 3-hydroxy-3-methylglutaryl coenzyme A reductase inhibitor therapy in older patients with myocardial infarction. Ann Intern Med. 2000;132:780–7. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-132-10-200005160-00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Reader D, Carstensen K. Five good food habits for people with diabetes. Park Nicollet Medical Foundation; 1995. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Franz MJ, Bantle JP, Beebe CA, et al. Evidence-based nutrition principles and recommendations for the treatment and prevention of diabetes and related complications. Diabetes Care. 2003;26(Suppl 1):S51–61. doi: 10.2337/diacare.26.2007.s51. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Zinman B, Ruderman N, Campaigne BN, et al. Physical activity/exercise and diabetes mellitus. Diabetes Care. 2003;26(Suppl 1):S73–7. doi: 10.2337/diacare.26.2007.s73. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Wald NJ, Law MR. A strategy to reduce cardiovascular disease by more than 80% BMJ. 2003;326:1419–23. doi: 10.1136/bmj.326.7404.1419. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Ware JEJ, Kosinski M, Keller SD. SF-12: How to score the SF-12 physical and mental health summary scales. 2. Boston, MA: The Health Institute, New England Medical Center; 1995. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Charlson ME, Pompei P, Ales KL, et al. A new method of classifying prognostic comorbidity in longitudinal studies: development and validation. J Chronic Dis. 1987;40(5):373–83. doi: 10.1016/0021-9681(87)90171-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Min LC, Elliott MN, Wenger NS, et al. Higher vulnerable elders survey scores predict death and functional decline in vulnerable older people. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2006;54:507–11. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2005.00615.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Lee SJ, Lindquist K, Segal MR, et al. Development and validation of a prognostic index for 4-year mortality in older adults. JAMA. 2006;295(7):801–8. doi: 10.1001/jama.295.7.801. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Gazmararian JA, Baker DW, Williams MV, et al. Health literacy among Medicare enrollees in a managed care organization. JAMA. 1999;281(6):545–51. doi: 10.1001/jama.281.6.545. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Tseng CW, Tierney E, Gerzoff RB, et al. Race/Ethnicity and economic differences in cost-related medication underuse among insured adults with diabetes. The TRIAD study. Diabetes Care. 2007 doi: 10.2337/dc07-1341. dc07-1341v1-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Peek ME, Chin MH. Care of community-living racial/ethnic minority elders. In: Munshi MN, Lipsitz LA, editors. Geriatric Diabetes. New York: Informa Healthcare; 2007. pp. 357–76. [Google Scholar]

- 42.Royall DR. Mild cognitive impairment and functional status. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2006;54(1):163–5. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2005.00539.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Royall DR, Palmer R, Chiodo LK, et al. Executive control mediates memory’s association with change in instrumental activities of daily living: the Freedom House Study. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2005;53(1):11–7. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2005.53004.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Montori VM, Gafni A, Charles C. A shared treatment decision-making approach between patients with chronic conditions and their clinicians: the case of diabetes. Health Expect. 2006;9(1):25–36. doi: 10.1111/j.1369-7625.2006.00359.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Huang ES, Sachs GA, Chin MH. Implications of new geriatric diabetes care guidelines for the assessment of quality of care in older patients. Med Care. 2006;44(4):373–7. doi: 10.1097/01.mlr.0000204281.42465.11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Epstein AM. Pay for performance at the tipping point. N Engl J Med. 2007;356(5):515–7. doi: 10.1056/NEJMe078002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Boyd CM, Darer J, Boult C, et al. Clinical practice guidelines and quality of care for older patients with multiple comorbid diseases: implications for pay for performance. JAMA. 2005;294:716–24. doi: 10.1001/jama.294.6.716. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]