Abstract

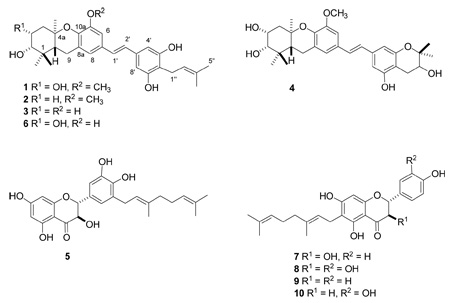

Bioassay-guided fractionation of an extract of the fruit of Macaranga alnifolia from Madagascar led to the isolation of four new prenylated stilbenes, schweinfurthins E–H (1–4), and one new geranylated dihydroflavonol, alnifoliol (5). The known prenylated stilbene, vedelianin (6), and the known geranylated flavonoids, bonanniol A (7), diplacol (8), bonannione A (9) and diplacone (10), were also isolated. All ten compounds were tested for antiproliferative activity in the A2780 human ovarian cancer cell line assay. Vedelianin (IC50 = 0.13 µM) exhibited the greatest activity among all isolates, while schweinfurthin E (IC50 = 0.26 µM) was the most potent of the new compounds.

The genus Macaranga is a large genus of the Euphorbiaceae family. Observation of Macaranga plants in their natural environment has revealed that they produce thread-like wax crystals on their ste ms, which make the slippery surfaces impassable for all insects except a species of ants known as “wax runners”. Chemical analysis has indicated that terpenoids make up a majority of the wax bloom content that helps maintain this symbiotic relationship between plant and insect.2 One of the more commonly studied species of this genus is M. tanarius, noted for its diterpenoid3,4 and flavonoid5–7 content. Work has also been performed on the isolation and characterization of terpenes from M. carolinensis,8 flavonoids from M. conifera9 and M. denticulate,10 chromenoflavones from M. indica, 11 clerodane diterpenes from M. monandra, 12 bergenin derivatives and polyphenols from M. peltata, 13 , 14 prenylflavones from M. pleiostemona, 15 a geranyl flavanone from M. schweinfurthii,16 tannins from M. sinensis,17 a rotenoid and other compounds from M. triloba, 18 and a geranylflavonol from M. vedeliana. 19 No phytochemical studies have been previously reported for M. alnifolia.

Results and Discussion

As part of an ongoing search for cytotoxic natural products from tropical rainforests in Madagascar through the International Cooperative Biodiversity Group (ICBG) program, we obtained an ethanolic extract of the fruit of Macaranga alnifolia Baker (Euphorbiaceae) for phytochemical investigation. This extract was found to be active in the A2780 ovarian cancer cytotoxicity assay, with an IC50 value of 3.5 µg/mL. Bioassay-guided fractionation led to the isolation of the five new compounds; the four new prenylated stilbenes schweinfurthins E–H (1–4), and the new geranylated dihydroflavonol, alnifoliol (5). Five known compounds were also isolated: the prenylated stilbene, vedelianin (6), the two geranylated dihydroflavonols, bonanniol A (7) and diplacol (8), and the two geranylated flavanones, bonannione A (9) and diplacone (or nymphaeol A) (10).

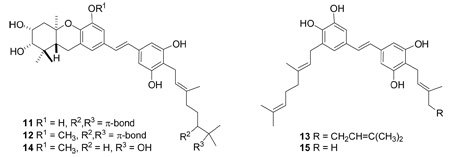

Schweinfurthins E–H (1–4) are closely related to schweinfurthins A, B, and D (11, 12, and 14) 20,21 and vedelianin (6),22 and are also more distantly related to the prenylated stilbenes schweinfurthin C (13)20 and mappain (15) isolated from M. mappa.23

Schweinfurthin E (1) was isolated as a pale yellow solid with a molecular formula of C30H38O6, based on its HRFABMS. Its UV spectrum, with λmax 331 and 224 nm, correlated well with literature values for compounds of the schweinfurthin class. Its 1H NMR spectrum indicated the presence of an asymmetrical stilbene core (δ 6.87 ppm, 1H, d, J = 16 Hz, H-1′; δ 6.77 ppm, 1H, d, J = 16.5 Hz, H-2′) with both an AA′ benzene ring system (δ 6.46 ppm, 2H, s, H-4′ and -8′) and an AB benzene ring system (δ 6.91 ppm, 1H, d, H-6; δ 6.84 ppm, 1H, d, H-8). Proton signals at δ 5.23 (1H, tq, J = 7, 1.5 Hz, H-2″), 3.27 (H-1″, partially obscured by solvent), 1.76 (3H, s, H-4″), and 1.65 ppm (3H, s, H-5″) indicated the presence of an isoprenyl group. Also present in this spectrum were signals for the protons of three other methyl groups at δ 1.40 (3H, s, H-13), 1.10 (3H, s, H-12) and 1.09 (3H, s, H-11) ppm; protons of a methoxy group at δ 3.84 ppm (3H, s, CH3O-5); and two methine protons bonded to oxygenated carbons at δ 4.14 (1H, q, J = 3.5, H-3) and 3.27 ppm (H-2, partially obscured by solvent).

The presence of an isoprenyl group was indicated by 13C NMR signals at δ 131.1 (C-3″), 124.6 (C-2″), 26.0 (C-5″), 23.3 (C-1″), and 17.9 ppm (C-4″). The three other methyl carbons resonated at δ 29.4 (C-12), 22.0 (C-13) and 16.5 ppm (C-11), and the methoxy carbon resonated at δ 56.5 ppm. Signals for three oxygenated sp3 carbons (C-2, C-4a, and C-3) were present in the spectrum at δ 78.8, 78.1, and 71.8 ppm, respectively, and the carbons of the AA′ benzene ring of the stilbene were observed at δ 157.3 ppm for the hydroxylated carbons (C-5′ and C-7′) and δ 105.8 ppm for the hydrogenated carbons (C-4′ and C-8′).

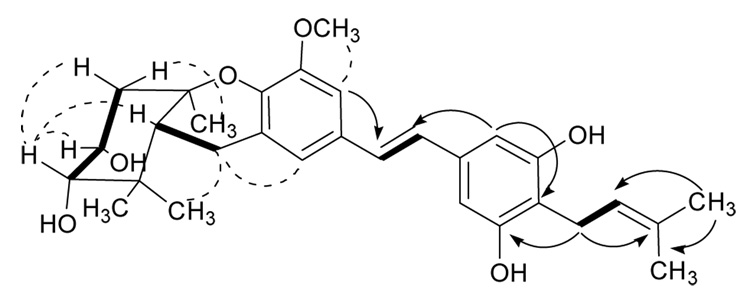

The NMR spectra of 1 corresponded closely with those of vedelianin (6)22 and schweinfurthin B (12).20 In particular, the observation of a “quartet” with J = 3.5 Hz for H-3 was in complete agreement with the “quartet” observed for H-3 of schweinfurthin B with J = 3.4 Hz,20 and confirmed the cis stereochemistry of the C-2 and C-3 hydroxyl groups. The gCOSY, HMBC, and ROESY spectra of 1 (Figure 1 and supporting information) and the observed spectroscopic differences between it and the reference compounds were also in complete agreement with this assignment and with the assignment of its structure as 5-O-methylvedelianin (or 4″-desisoprenyl-schweinfurthin B).

Figure 1.

Key COSY (bold), HMBC (arrows) and ROESY (dashed) correlations of 1

Schweinfurthin F (2) was isolated as a pale yellow solid with a molecular formula of C30H38O5, based on HRFABMS. Its 1H and 13C NMR spectra were very similar to those of 1, with the major differences that the NMR signals for H-3 and C-3 were shifted significantly upfield (from δ 4.14 to 2.03 ppm and from δ 71.7 to 39.4 ppm, respectively) when compared to those of 1. These observations, coupled with the fact that the molecule of 2 has five oxygen atoms in place of the six oxygens of 1, suggested that 2 is a 3-deoxy derivative of 1. This was confirmed by the upfield shifts for neighboring hydrogens on the α-side of the molecule (H-4, H-11, H-13) and also for adjacent carbons (C-4, C-11, C-12, C-13). The NMR spectra of 2 were essentially identical with those of a recently prepared synthetic sample,24 thus confirming its structure unambiguously.

Schweinfurthin G (3) was isolated as a pale yellow solid. Its 1H and 13C NMR spectra were very similar to those of 2, differing significantly only in the lack of signals at δ ~3.8 and ~56 ppm, respectively, corresponding to the methoxy group in 2. The structure of 3 was thus assigned as 3-deoxyvedelianin.

Schweinfurthin H (4) was isolated as a pale yellow solid. It gave a molecular formula of C30H38O7, based on HRFABMS, differing from that of 1 by a single oxygen. The 1H NMR spectrum of 4 indicated the presence of a different asymmetrical stilbene group with a second, alternate AB benzene ring system rather than an AA′ benzene ring system; the signals for H-4′ (δ 6.52 ppm) and H-8′ (δ 6.44 ppm) appeared as two separate peaks. The absence of a 1H NMR signal for the isoprenyl double bond and upfield shifts of H-2″ (δ 3.73 ppm), H-4″ (δ 1.33 ppm) and H-5″ (δ 1.23 ppm), and the appearance of H-1″ as doublet of doublets at δ 2.90 and 2.53 ppm, all indicated that the isoprenyl group was cyclized with one of the phenolic oxygens. The hydroxylation of C-2″ was also apparent from its 13C NMR chemical shift of δ 76.4 ppm. The final structure was confirmed through NMR comparison with the literature values reported for chiricanine B (16) a tricyclic prenylated stilbene from Lonchocarpus chiricanus.25 The stereochemistry of the 2″-hydroxyl group of 4 was not determined.

The data presented to this point demonstrate the relative stereochemistry of compounds 1 – 4, but do not establish their absolute stereochemistry. Fortunately this can be established by a comparison of CD spectra and of optical rotations between these compounds and the enantiomers of schweinfurthin F (2). The CD spectra of compounds 1 – 4 were essentially identical, with strong positive differential dichroic absorptions at 196 nm and strong negative absorptions at 210 nm. Their specific optical rotations at 589 nm were all also similarly positive, with values of +49.2, +50.8, +33.3, and +32.4 for schweinfurthins E–H (1 – 4). These comparisons establish that compounds 1 – 4 all belong to the same stereochemical series.

Both the R,R,R– and the S,S,S–enantiomers of schweinfurthin F (2) have recently been synthesized by the Wiemer group.24 They obtained optical rotations of +53.4 for the 1R,4aR,9aR isomer and −55.8 for the 1S,4aS,9aS isomer in CH3OH; the value for the 1R,4aR,9aR isomer matches well with the value for the natural product (+50.8 in CH3OH). We conclude that schweinfurthin F (2) has the 1R,4aR,9aR stereochemistry, and thus that compounds 1, 3, and 4 also have the same 1R,4aR,9aR stereochemistry.

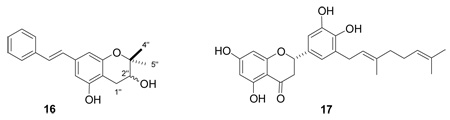

The flavonoid alnifoliol (5) was isolated as a yellow-brown solid with a molecular formula of C25H28O7, based on HRFABMS. The 1H NMR spectrum of 5 showed signals for four aromatic protons (δ 6.81, d, H-2′; δ 6.74, d, H-6′; δ 5.91, s, H-8; δ 5.87, s, H-6), one oxymethine (δ 4.88, d, H-2), and one methine α to a carbonyl (δ 4.47, d, H-3). These data suggested that 5 possesses a dihydroflavanol skeleton. Signals for a geranyl substituent (δ 5.33, m, H-2″; δ 5.10, m, H-7″; δ 3.33, d, H-1″; δ 2.09, td, H-6″; δ 2.02, t, H-5″; δ 1.70, s, H-4″; δ 1.61, s, H-9″; δ 1.56, s, H-10″) were also observed. The fact that proton signals for both H-6 and H-8 were present indicated that the geranyl group was on the B-ring. The splitting patterns for H-2′ and H-6′ confirmed the location of the geranyl group at C-5. Compound 5 is identical to a known component of propolis, isonymphaeol-B (17), except for the presence of the HO-3 group. Comparison of the NMR spectra of 5 with the literature spectra of 1726 fully supported the structural assignment of 5. The coupling constant of the C-2 and C-3 protons (11 Hz) was consistent with their anticoplanar orientation, indicating a trans stereochemistry for the C-2 aryl and C-3 hydroxyl substituents.

The known compounds vedelianin (6),22 bonanniol A (7), 27 diplacol (8),28 , 29 bonannione A (9),27 and diplacone (10, also known as nymphaeol A)30,31 were also isolated, and their structures were determined based upon comparison of their 1H NMR, 13C NMR, and HRFABMS spectra to literature values.22,26–31

All ten compounds isolated from the fruits of M. alnifolia were tested for antiproliferative activity against the A2780 ovarian cancer cell line, and the results are provided in Table 1.

Table 1.

Cytotoxicity Data of Macaranga alnifolia Compounds to A2780 Cells.

| compound | IC50 (µM) |

|---|---|

| schweinfurthin E (1) | 0.26 |

| schweinfurthin F (2) | 5.0 |

| schweinfurthin G (3) | 0.39 |

| schweinfurthin H (4) | 4.5 |

| alnifoliol (5) | 27.3 |

| vedelianin (6) | 0.13 |

| bonanniol A (7) | 23.5 |

| diplacol (8) | 11.5 |

| bonannione A (9) | 24.5 |

| diplacone (10) | 10.5 |

Schweinfurthin E (1) was also tested in the 60-cell human tumor cancer screen at the National Cancer Institute (NCI). The assay measure used by NCI that most closely corresponds to the IC50 values for antiproliferative activity is the GI50 value, and schweinfurthin E exhibited a mean panel GI50 of 0.19 µM. All lines of the leukemia subpanel were found to be highly sensitive to 1, while all lines of the ovarian cancer subpanel (OVCAR-3, -4, and -8 and SK-OV-3) were somewhat resistant, with GI50 values averaging 2.2 µM. This result is somewhat surprising in view of the sensitivity of the A2780 ovarian cancer cell line to 1, but can be explained in part by the fact that the A2780 cell line is a drug-sensitive line.32 The most sensitive lines included leukemia (MOLT-4) and CNS (SF-295) and renal (A498 and CAKI-1) cancers, which all gave GI50 and TGI values of < 10 nM. The complete mean graph for 1 is proved as Supporting Information to this manuscript. These differential cytotoxicity results suggest that schweinfurthin E (1), similar to the other schweinfurthins, may share a similar mechanism of action with the stelletins.

It is instructive to compare the data reported above with the previously reported data for the schweinfurthins A–D20,21 and for 3-deoxyschweinfurthin and its synthetic analogs.24,33 The literature data were reported primarily as mean GI50 values from the NCI 60-cell line screen, and the data above are only for one cell line, so comparisons are only possible between compounds determined in the same bioassay.

The first comparisons are between the cytotoxicities of schweinfurthin E (1, IC50 0.26 µM) and vedelianin (6, IC50 0.13 µM) and those of schweinfurthin G (3, IC50 0.39 µM) and vedelianin. In the first case, vedelianin is twice as potent as schweinfurthin E, suggesting that the replacement of the C-5 hydroxyl group with a methoxy group is deleterious to activity. In the second case, vedelianin (6) is about three times as potent as schweinfurthin G (3), indicating that the C-3 hydroxyl group enhances activity in this series. However, the issue is not as simple as this, because 3-deoxyschweinfurthin B is slightly more active than schweinfurthin B,34 so clearly the length of the side chain has an influence on how the C-3 hydroxyl group affects activity.

Another direct comparison is possible between the mean GI50 values of schweinfurthin E (1, 0.19 µM) and schweinfurthin B (12, 0.79 µM); this indicates that the shorter geranyl side chain of 1 enhances its activity. A final comparison between schweinfurthin F (2, IC50 5.0 µM) and schweinfurthin G (3, IC50 0.39 µM) indicates that the combination of the loss of the C-3 hydroxyl group with methylation of the C-5 hydroxyl group results in a greater loss of activity than would have been predicted by either modification alone. The trend in all these comparisons is for the more polar compound to be more active, so it is possible that the observed activity is limited in some way by aqueous solubility, but further experiments are required to confirm this suggestion. Schweinfurthin C (13) was found to be much less active than schweinfurthins A, B, and D, so cyclization of the geranyl group must play an important role in mediating the biological activity of these compounds.

Experimental Section

General Experimental Procedures

Optical rotations were recorded on a Perkin-Elmer 241 polarimeter. CD spectra were recorded on a JASCO J-700 spectrometer. NMR spectra were obtained on a JEOL Eclipse 500 or a Varian INOVA 400 MHz spectrometer. The chemical shifts are given in δ (ppm), and coupling constants are reported in Hz. FAB mass spectra were obtained on a JEOL JMS-HX-110 instrument. HPLC was performed on a Shimadzu LC-10AT instrument with a semi-preparative C8 Varian Dynamax column (5 µm, 250 × 10 mm) and a preparative phenyl Varian Dynamax column (8 µm, 250 × 21.4 mm). Finnigan LTQ LC/MS with a C18 Hypersil column (5 µm, 100 × 2.1 mm) was also used for crude sample analysis.

Antiproliferative Bioassays

Antiproliferative activity measurements were performed at Virginia Polytechnic Institute and State University against the A2780 ovarian cancer cell line as previously described. The A2780 cell line is a drug-sensitive human ovarian cancer cell line.32

Plant Material

Immature and mature fruits of Macaranga alnifolia Baker (Euphorbiaceae) (vernacular name “Mokaranana”) were collected in November 2001. The specimens were collected around the Natural Reserve of Zahamena in the province of Toamasina, Madagascar, at coordinates 17.41.01S and 48.38.28E, at an elevation of 900 m. Duplicate voucher specimens have been deposited at the Centre National d’Application des Recherches Pharmaceutiques (CNARP) and the Direction des Recherches Forestieres et Piscicoles Herbarium (TEF) in Antananarivo, Madagascar; the Missouri Botanical Garden in St. Louis, Missouri (MO); and the Museum National d’Histoire Naturelle in Paris, France (P).

Extraction and Isolation

Dried fruits of M. alnifolia (275 g) were ground in a hammer mill, then extracted with EtOH by percolation for 24 h at rt to give the crude extract MG 1021 (12.8 g), of which 2.84 g was made available to Virginia Polytechnic Institute and State University. The crude bioactive extract MG 1021 (IC50 = 3.5 µg/mL, 2.32 g) was partitioned between hexanes (200 mL) and MeOH-H2O (4:1, 200 mL). The aqueous fraction was dried and subsequently partitioned between 1-BuOH and H2O. The evaporated 1-BuOH fraction (1.96 g) displayed cytotoxicity (IC50 = 1.0 µg/mL) and was further separated by repeated RP-C18 column chromatography. The fractions eluted with 70% and 80% MeOH-H2O showed the most improved activity and were separated by solid-phase extraction into fractions eluting with MeOH-H2O (3:2) and MeOH. Preparative RP-C18 HPLC using MeOH-H2O (4:1, 1 mL/min) on these bioactive eluates and combination of similar fractions yielded a total of 16 new fractions (A–K and L–P). Fraction D was identified as schweinfurthin E (1, tR 21.5 min, 25.4 mg), while fractions A–C yielded vedelianin (6, tR 17.1 min, 4.1 mg), schweinfurthin G (3, tR 18.2 min, 0.9 mg) and schweinfurthin H (4, tR 19.5 min, 1.5 mg), respectively, upon additional purification by semipreparative RP-C18 and RP-phenyl HPLC, eluting with MeOH-H2O, 4:1. Fraction F was also identified as schweinfurthin F (2, tR 25.9 min, 10.6 mg). Fractions G (tR 32.6 min) and H (tR 30–45 min) were combined and purified by semipreparative RP-phenyl HPLC to obtain both alnifoliol (5, 24.9 mg) and diplacone (10, 34.1 mg). Additionally, fractions M, N and P yielded diplacol (8, tR 19 min, 6.7 mg), bonanniol A (7, tR 21 min, 27.1 mg), and bonannione A (9, tR 35 min, 3.0 mg). The structures of the known compounds were identified by comparison of their spectroscopic data with literature values.22,27–31

Schweinfurthin E (1)

pale yellow solid; [α]22D +49.2 (c 0.13, CH3OH); UV (MeOH) λmax (log ε) 223 (4.5), 331 (4.5) nm; CD (MeOH) λmax (Δε, dm3 mol−1 cm−1) 196 (+173), 210 (−139), 222 (−135), 250 (+11); 1H NMR (CD3OD, 500 MHz) δ 6.91 (1H, d, J = 1.5 Hz, H-6), 6.87 (1H, d, J = 16 Hz, H-1′), 6.84 (1H, d, H-8), 6.77 (1H, d, J = 16.5 Hz, H-2′), 6.46 (2H, s, H-4′, 8′), 5.23 (1H, tq, J = 7, 1.5 Hz, H-2″), 4.14 (1H, q, J = 3.5 Hz, H-3), 3.84 (3H, s, CH3O-5), 3.30 (partially obscured by solvent, H-2, 1″), 2.76 (2H, m, H-9), 2.34 (1H, dd, J = 14, 3 Hz, H-4), 1.93 (1H, dd, J = 13.5, 3.5 Hz, H-4), 1.76 (3H, s, H-4″), 1.74 (1H, dd, J = 12.5, 6 Hz, H-9a), 1.65 (3H, s, H-5″), 1.40 (3H, s, H-13), 1.10 (3H, s, H-12), 1.09 (3H, s, H-11); 13C NMR (CD3OD, 125 MHz) δ 157.3 (C-5′, 7′), 150.2 (C-5), 143.4 (C-10a), 137.6 (C-3′), 131.1 (C-3″), 130.8 (C-7), 128.6 (C-1′), 127.7 (C-2′), 124.6 (C-2″), 124.4 (C-8a), 121.7 (C-8), 116.0 (C-6′), 108.3 (C-6), 105.8 (C-4′, 8′), 78.8 (C-2), 78.1 (C-4a), 71.8 (C-3), 56.5 (CH3O-5), 48.5 (C-9a) 44.8 (C-4), 39.2 (C-1), 29.4 (C-12), 26.0 (C-5″), 24.0 (C-9), 23.3 (C-1″), 22.0 (C-13), 17.9 (C-4″), 16.5 (C-11); HRFABMS m/z 494.2646 [M]+ (calcd for C30H38O6, 494.2668).

Schweinfurthin F (2)

pale yellow solid; [α]22D +50.8 (c 0.06, CH3OH); UV (MeOH) λmax (log ε) 224 (4.4), 331 (4.4) nm; CD (MeOH) λmax (Δε, dm3 mol−1 cm−1) 196 (+176), 210 (−134), 220inf (−130) 247 (+9.5), 258 (+16); 1H NMR (CD3OD, 500 MHz) δ 6.91 (1H, d, J = 1.5 Hz, H-6), 6.86 (1H, d, J = 16.5 Hz, H-1′), 6.83 (1H, d, J = 1.5 Hz, H-8), 6.77 (1H, d, J = 16.5 Hz, H-2′), 6.46 (2H, s, H-4′, 8′), 5.23 (1H, tq, J = 7, 1.5 Hz, H-2″), 3.83 (3H, s, CH3O-5), 3.30 (partially obscured by solvent, H-2, 1″), 2.72 (2H, m, H-9), 2.03 (2H, m, H-3), 1.79 (1H, m, H-4), 1.76 (3H, s, H-4″), 1.75 (1H, m, H-9a), 1.65 (1H, m, H-4), 1.65 (3H, s, H-5″), 1.21 (3H, s, H-13), 1.09 (3H, s, H-12), 0.87 (3H, s, H-11); 13C NMR (CD3OD, 125 MHz) δ 157.3 (C-5′, 7′), 150.2 (C-5), 143.7 (C-10a), 137.6 (C-3′), 131.2 (C-3″), 130.9 (C-7), 128.6 (C-1′), 127.8 (C-2′), 124.6 (C-2″), 124.1 (C-8a), 121.8 (C-8), 116.0 (C-6′), 108.3 (C-6), 105.8 (C-4′, 8′), 78.8 (C-2), 78.2 (C-4a), 56.5 (CH3O-5), 39.5 (C-3), 39.0 (C-1), 29.0 (C-4), 27.9 (C-12), 26.0 (C-5″), 24.1 (C-9), 23.3 (C-1″), 20.2 (C-13), 17.9 (C-4″), 14.9 (C-11); HRFABMS m/z 478.2737 [M]+ (calcd for C30H38O5, 478.2719).

Schweinfurthin G (3)

pale yellow solid; [α]22D +33.3 (c 0.03, CH3OH); UV (MeOH) λmax (log ε) 228 (4.2) 329 (3.9) nm; CD (MeOH) λmax (Δε, dm3 mol−1 cm−1) 196 (+177), 210 (−133), 220 (−123), 247 (+10); 1H NMR (CD3OD, 500 MHz) δ 6.80 (1H, d, J = 17 Hz, H-1′), 6.79 (1H, d, H-6), 6.72 (1H, d, J = 1.5 Hz, H-8), 6.70 (1H, J = 16 Hz, H-2′), 6.44 (2H, s, H-4′, 8′), 5.23 (1H, tq, J = 7, 1.5 Hz, H-2″), 3.30 (partially obscured by solvent, H-2, 1″), 2.71 (2H, m, H-9), 2.06 (2H, m, H-3), 1.80 (1H, m, H-4), 1.76 (3H, s, H-4″), 1.75 (1H, m, H-9a), 1.68 (1H, m, H-4), 1.65 (3H, s, H-5″), 1.23 (3H, s, H-13), 1.10 (3H, s, H-12), 0.88 (3H, s, H-11); 13C NMR (CD3OD, 125 MHz) δ 157.3 (C-5′, 7′), 147.0 (C-5), 142.2 (C-10a), 141.3 (C-3″), 137.6 (C-3′), 131.0 (C-7), 128.6 (C-1′), 127.5 (C-2′), 124.6 (C-2″), 124.0 (C-8a), 120.4 (C-8), 115.9 (C-6′), 111.1 (C-6), 105.7 (C-4′, 8′), 78.8 (C-2), 78.2 (C-4a), 39.5 (C-3), 38.9 (C-1), 29.0 (C-4), 27.9 (C-12), 26.0 (C-5″), 24.0 (C-9), 23.3 (C-1″), 20.3 (C-13), 17.9 (C-4″), 14.8 (C-11). HRFABMS m/z 464.2595 [M]+ (calcd for C29H36O5, 464.2563).

Schweinfurthin H (4)

pale yellow solid; [α]22D +32.4 (c 0.04, CH3OH); UV (MeOH) λmax (log ε) 224 (4.5), 329 (4.4) nm; CD (MeOH) λmax (Δε, dm3 mol−1 cm−1) 196 (+232), 210 (−145), 220inf (−135), 250 (+12); 1H NMR (CD3OD, 500 MHz) δ 6.93 (1H, d, J = 1.5 Hz, H-6), 6.90 (1H, d, J = 16 Hz, H-1′), 6.85 (1H, d, J = 1 Hz, H-8), 6.80 (1H, d, J = 16 Hz, H-2′), 6.52 (1H, d, J = 1.5 Hz, H-4′), 6.44 (1H, d, J = 1 Hz, H-8′), 4.14 (1H, q, J = 3.5 Hz, H-3), 3.84 (3H, s, CH3O-5), 3.73 (1H, dd, J = 7.5, 5.5 Hz, H-2″), 3.30 (1H, m, H-2), 2.90 (1H, dd, J = 17, 5.5 Hz, H-1″), 2.76 (2H, m, H-9), 2.53 (1H, dd, J = 17, 7.5 Hz, H-1″), 2.34 (1H, dd, J = 14, 3 Hz, H-4), 1.92 (1H, dd, J = 14.5 Hz, H-4), 1.74 (1H, dd, J = 12, 5.5 Hz, H-9a), 1.40 (3H, s, H-13), 1.33 (3H, s, H-4″), 1.23 (3H, s, H-5″), 1.10 (3H, s, H-12), 1.09 (3H, s, H-11); 13C NMR (CD3OD, 125 MHz) δ 157.1 (C-5′), 155.3 (C-7′), 150.2 (C-5), 143.5 (C-10a), 138.5 (C-3′), 130.6 (C-7), 129.1 (C-1′), 127.5 (C-2′), 124.4 (C-8a), 121.9 (C-8), 108.4 (C-4′), 108.4 (C-6), 107.6 (C-6′), 105.0 (C-8′), 78.8 (C-2), 78.1 (C-4a), 77.7 (C-3″), 71.8 (C-3), 70.6 (C-2″), 56.5 (CH3O-5), 44.8 (C-4), 39.2 (C-1), 29.4 (C-12), 27.4 (C-1″), 25.8 (C-5″), 24.0 (C-9), 22.0 (C-13), 20.8 (C-4″), 16.6 (C-11); HRFABMS m/z 510.2579 [M]+ (calcd for C30H38O7, 510.2618).

Alnifoliol (5)

yellowish-brown solid; [α]23D +15.3 (c 0.25, CH3OH); UV (MeOH) λmax (log ε) 213 (4.7), 290 (4.4) nm; CD (MeOH) λmax (Δε, dm3 mol−1 cm−1) 196 (+150), 210 (−123), 220inf (−116), 262 (+16), 295 (−19); 1H NMR (CD3OD, 500 MHz) δ 6.81 (1H, d, H-2′), 6.74 (1H, d, J = 2 Hz, H-6′), 5.91 (1H, d, J = 2.5 Hz, H-8), 5.87 (1H, d, H-6), 5.34 (2H, t, H-2″), 5.10 (2H, t, H-7″), 4.88 (1H, d, H-2), 4.47 (1H, d, J = 11 Hz, H-3), 3.31 (2H, d, J = 7.5 Hz, H-1″), 2.09 (2H, q, J = 7.5 Hz, H-6″), 2.02 (2H, t, J = 8 Hz, H-5″), 1.70 (3H, s, H-4″), 1.61 (3H, s, H-9″), 1.56 (3H, s, H-10″); 13C NMR (CD3OD, 125 MHz) δ 197.0 (C-4), 167.4 (C-7), 164.0 (C-5), 163.2 (C-9), 144.5 (C-3′), 143.6 (C-4′), 135.5 (C-3″), 130.9 (C-8″), 128.1 (C-1′), 127.6 (C-5′), 124.1 (C-7″), 122.5 (C-2″), 120.0 (C-6′), 111.8 (C-2′), 100.5 (C-10), 96.0 (C-8), 95.0 (C-6), 84.1 (C-2), 72.4 (C-3), 39.6 (C-5″), 27.8 (C-1″), 26.4 (C-6″), 24.6 (C-9″), 16.4 (C-10″), 14.9 (C-4″); HRFABMS m/z 440.1831 [M]+ (calcd for C25H28O7, 440.1835).

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgment

This project was supported by the Fogarty International Center, the National Cancer Institute, the National Science Foundation, the National Heart, Lung and Blood Institute, the National Institute of Mental Health, the Office of Dietary Supplements, and the Office of the Director of NIH, under Cooperative Agreement U01 TW000313 with the International Cooperative Biodiversity Groups, and this support is gratefully acknowledged. We thank Mr. B. Bebout for obtaining the mass spectra, Mr. T. Glass for assistance with the NMR spectra, and Mr. Kim Harich for obtaining the CD spectra. Field work essential for this project was conducted under a collaborative agreement between the Missouri Botanical Garden and the Parc Botanique et Zoologique de Tsimbazaza and a multilateral agreement between the ICBG partners, including the Centre National d’Applications des Recherches Pharmaceutiques. We gratefully acknowledge courtesies extended by the Government of Madagascar (Ministère des Eaux et Forêts). We also thank Drs. Wiemer and Beutler for a prepublication copy of their manuscript.24

Footnotes

Dedicated to the late Dr. Kenneth L. Rinehart, of the University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign, for his pioneering work on bioactive natural products.

Supporting Information Available: Characterization data for compounds 6 – 10, NCI 60-cell line data for 1, 1H and 13C NMR spectra for compounds 1–10, and gCOSY, HMQC, HMBC, and ROESY spectra of compound 1. (20 pages). This material is available free of charge via the Internet at http://pubs.acs.org.

References and Notes

- 1.Biodiversity Conservation and Drug Discovery in Madagascar, Part 25. For Part 24, seeCao S, Norris A, Miller JS, Ratovoson F, Razafitsalama J, Andriantsiferana R, Rasamison VE, TenDyke K, Suh T, Kingston DGI. J. Nat. Prod. 2007 doi: 10.1021/np060506g.

- 2.Markstaedter C, Federle W, Jetter R, Riederer M, Hoelldobler B. Chemoecology. 2000;10:33–40. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Hui W-H, Ng K-K, Fukamiya N, Koreeda M, Nakanishi K. Phytochemistry. 1971;10:1617–1620. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Hui W-H, Li M-M, Ng K-K. Phytochemistry. 1975;14:816–817. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Tseng M-H, Chou C-H, Chen Y-M, Kuo YH. J. Nat. Prod. 2001;64:827–828. doi: 10.1021/np0100338. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Tseng M-H, Kuo Y-H, Chen Y-M, Chou C-H. J. Chem. Ecol. 2003;29:1269–1286. doi: 10.1023/a:1023846010108. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Phommart S, Sutthivaiyakit P, Chimnoi N, Ruchirawat S, Sutthivaiyakit S. J. Nat. Prod. 2005;68:927–930. doi: 10.1021/np0500272. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Han G-Q, Che C-T, Fong HHS, Farnsworth NR, Phoebe CH. J. Fitoterapia. 1988;59:242–244. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Jang DS, Cuendet M, Hawthorne ME, Kardono LBS, Kawanishi K, Fong HHS, Mehta RG, Pezzuto JM, Kinghorn AD. Phytochemistry. 2002;61:867–872. doi: 10.1016/s0031-9422(02)00378-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Sutthivaiyakit S, Unganont S, Sutthivaiyakit P, Suksamrarn A. Tetrahedron. 2002;58:3619–3622. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Sultana S, Ilyas M. Phytochemistry. 1986;25:953–954. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Salah MA, Bedir E, Toyang NJ, Kahn IA, Harries MD, Wedge DE. J. Ag. Food Chem. 2003;51:7607–7610. doi: 10.1021/jf034682w. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ramaiah PA, Row LR, Reddy DS, Anjaneyulu ASR, Ward RS, Pelter A. J. Chem. Soc. Perkin. 1979;1:2313–2316. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Asharani T, Seetharaman TR. Fitoterapia. 1994;65:184–185. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Schuetz BA, Wright AD, Rali T, Sticher O. Phytochemistry. 1995;40:1273–1277. doi: 10.1016/0031-9422(95)00491-o. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Beutler JA, McCall KL, Boyd MR. Nat. Prod. Lett. 1999;13:29–32. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Lin J-H, Ishimatsu M, Tanaka T, Nonaka G-I, Nishioka I. Chem. Pharm. Bull. 1990;38:1844–1851. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Jang DS, Cuendet M, Pawlus AD, Kardono LBS, Kawanishi K, Farnsworth NR, Fong HHS, Pezzuto JM, Kinghorn AD. 2004;65:345–350. doi: 10.1016/j.phytochem.2003.10.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Hnawia E, Thoison O, Gueritte-Voegelein F, Bourret D, Sevenet TA. Phytochemistry. 1990;29:2367–2368. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Beutler JA, Shoemaker RH, Johnson T, Boyd MR. J. Nat. Prod. 1998;61:1509–1512. doi: 10.1021/np980208m. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Beutler JA, Jato J, Cragg GM, Boyd MR. Nat. Prod. Lett. 2000;14:399–404. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Thoison O, Hnawia E, Gueritte-Voegelein F, Sevenet T. Phytochemistry. 1992;31:1439–1442. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kaaden JEvd, Hemscheidt TK, Mooberry SL. J. Nat. Prod. 2001;64:103–105. doi: 10.1021/np000265r. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Mente NR, Wiemer AJ, Neighbors JD, Beutler JA, Hohl RJ, Wiemer DF. Bioorg. Med. Chem. Lett. 2006 doi: 10.1016/j.bmcl.2006.11.096. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Ioset J-R, Marston A, Gupta M, Hostettmann K. J. Nat. Prod. 2001;64:710–715. doi: 10.1021/np000597w. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Kumazawa S, Goto H, Hamasaka T, Fukumoto S, Fujimoto T, Nakayama T. Biosci. Biotechnol. Biochem. 2004;68:260–262. doi: 10.1271/bbb.68.260. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Bruno M, Savona G, Lamartina L, Lentini F. Heterocycles. 1985;23:1147–1153. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Lincoln DE. Biochem. Syst. Ecol. 1980;8:397–400. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Wollenweber E, Schober I, Schilling G, Arriaga-Giner FJ, Roitman JN. Phytochemistry. 1989;28:3493–3496. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Phillips WR, Baj NJ, Gunatilaka AAL, Kingston DGI. J. Nat. Prod. 1996;59:495–497. doi: 10.1021/np960240l. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Yakushijin K, Shibayama K, Murata H, Furukawa H. Heterocycles. 1980;14:397–402. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Louie KG, Behrens BC, Kinsella TJ, Hamilton TC, Grotzinger KR, McKoy WM, Winker MA, Ozols RF. Cancer Res. 1985;45:2110–2115. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Neighbors JD, Salnikova MS, Beutler JA, Wiemer DF. Bioorg. Med. Chem. 2006;14:1771–1784. doi: 10.1016/j.bmc.2005.10.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Neighbors JD, Beutler JA, Wiemer DF. J. Org. Chem. 2005;70:925–931. doi: 10.1021/jo048444r. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.