Abstract

The novel α1D Ca2+ channel together with α1C Ca2+ channel contribute to the L-type Ca2+ current (ICa-L) in the mouse supraventricular tissue. However, its functional role in the heart is just emerging. We used the α1D gene knockout (KO) mouse to investigate the electrophysiological features, the relative contribution of the α1D Ca2+ channel to the global ICa-L, the intracellular Ca2+ transient, the Ca2+ handling by the sarcoplasmic reticulum (SR), and the inducibility of atrial fibrillation (AF). In vivo and ex vivo ECG recordings from α1D KO mice demonstrated significant sinus bradycardia, atrioventricular block, and vulnerability to AF. The wild-type mice showed no ECG abnormalities and no AF. Patch-clamp recordings from isolated α1D KO atrial myocytes revealed a significant reduction of ICa-L (24.5%; P < 0.05). However, there were no changes in other currents such as INa, ICa-T, IK, If, and Ito and no changes in α1C mRNA levels of α1D KO atria. Fura 2-loaded atrial myocytes showed reduced intracellular Ca2+ transient (∼40%; P < 0.05) and rapid caffeine application caused a 17% reduction of the SR Ca2+ content (P < 0.05) and a 28% reduction (P < 0.05) of fractional SR Ca2+ release in α1D KO atria. In conclusion, genetic deletion of α1D Ca2+ channel in mice results in atrial electrocardiographic abnormalities and AF vulnerability. The electrical abnormalities in the α1D KO mice were associated with a decrease in the total ICa-L density, a reduction in intracellular Ca2+ transient, and impaired intracellular Ca2+ handling. These findings provide new insights into the mechanism leading to atrial electrical dysfunction in the α1D KO mice.

Keywords: mice, calcium transient, arrhythmia, myocyte

the voltage-gated α1d Ca2+ channel was previously considered to be expressed only in cells of neuroendocrine origin (10). Recent studies (11, 15, 16, 19, 26) reported that the α1D deletion in mice causes sinus bradycardia and various degrees of atrioventricular (AV) block. The evidence presented suggests a critical role of the α1D Ca2+ channel in diastolic depolarization and in the rate of discharge of the sinoatrial (SA) node. The expression of α1D Ca2+ channel was demonstrated in the SA node, AV node, and atria, but not in the ventricles of adult hearts (15, 20, 26). Therefore, deletion of α1D Ca2+ channel could play an important role in altering the normal activity of the atrium and might also contribute to atrial arrhythmias, such as atrial fibrillation (AF).

AF is the most common cardiac arrhythmia, and it is associated with a four- to fivefold increase in the risk of stroke compared with the general population. It affects an estimated 2.2 million adults in the United States (4). Because of its clinical relevance and the lack of an effective therapy, many experimental models of AF have been tested to elucidate the mechanisms of initiation and maintenance of AF. A decreased L-type Ca2+ current (ICa-L) density is a common finding and has been reported in several models of AF (23, 25).

Unlike ventricular cells, a unique property of atrial cells is that both α1C and α1D Ca2+ channels contribute to the total ICa-L (26). While a decrease in ICa-L density and a reduction in mRNA and protein level of the α1C Ca2+ channel in AF have been reported (2, 12), the role of α1D Ca2+ channel in AF remains unclear. However, one study (5) using gene microarray approach demonstrated a significant reduction in α1D Ca2+ channel mRNA (as well as a reduction of α1C Ca2+ channel mRNA) in atrial samples from patients with AF, supporting the potential role of α1D L-type Ca2+ channel in the genesis of AF.

Because α1C and α1D Ca2+ currents cannot be separated in the native atrial myocytes using conventional electrophysiological and/or pharmacological tools, the α1D Ca2+ channel knockout (KO) mouse thus represents a unique model to assess the relative contribution of α1D Ca2+ channel to atrial myocyte electrophysiology. In this study, we used the α1D Ca2+ channel KO mouse model, to investigate the electrophysiological features, the relative contribution of α1D Ca2+ channel to the total ICa-L, the intracellular Ca2+ transient ([Ca2+]iT), and the Ca2+ handling by the sarcoplasmic reticulum (SR) to ultimately gain insight into the mechanism leading to atrial dysfunction in this mouse model.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

The investigation conforms to the Guide for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals published by the US National Institutes of Health (National Institutes of Health Publication No. 85-23, revised 1996). The experimental protocols were approved by the Animal Care and Use Committee at the Veterans Affairs New York Harbor Healthcare System (New York, NY).

Six- to ten-week-old α1D Ca2+ channel KO mice and age-matched wild-type (WT) littermates were used in this study. The α1D KO mice were kindly provided by Dr. R. Flavell (Yale University, School of Medicine, New Haven, CN) with the concurrence of Dr. J. Striessnig (Peter Mayr Strasse, Innsbruck, Austria). The generation of α1D KO has been previously described (19).

Surface ECG recordings.

High resolution surface ECG was recorded and analyzed using a digital acquisition and analysis system (Biopac Systems, Santa Barbara, CA). Mice were placed on a warm pad and subjected to anesthetic inhalation; gauze pledged was moistened with isoflurane (3–4%) and placed in the bottom of a drop jar under a fume hood. After the mouse was anesthetized, it was removed and a mask was used to maintain anesthesia with 2% isoflurane (mix of isoflurane and oxygen). Electrodes were positioned on the sole of each mouse foot. Electrical signals were recorded at 1,200 Hz stored in a computer hard disk and analyzed off-line (AcqKnowledge software, Biopac Systems). Tracings were analyzed for heart rate, P-wave duration, P-wave amplitude, P-R interval, QRS duration, and conduction abnormalities including first-, second-, and third-degree AV block.

Gene expression analysis for α1C and α1D transcripts using real-time RT-PCR.

Total cellular RNA was isolated from atrial tissue of WT and α1D KO mice using Trizol LS Reagent (Invitrogen) according to the manufacturer's recommendations. RNA was quantified by spectrophotometry at 260 nm, and the ratio of absorbance at 260 nm to that of 280 nm was >1.8 for all samples. Degradation of RNA was monitored by the observation of appropriate 28S to 18S ribosomal RNA ratios as determined by ethidium bromide staining of agarose gels. First-strand cDNA synthesis was carried out using RETROscript reverse transcriptase kit (Ambion). Gene-specific intron-spanning Taqman primers (Applied Biosystems) were used to quantify the relative changes in mRNA levels of α1C and α1D in the WT and α1D KO mice (Hs99999901_s1, Mm00437917_m1, Mm00551384_m1) using ABI PRISM 7500 real-time PCR (Applied Biosystems). All real-time PCR reactions were done in triplicates, and the cycle threshold (CT) values were normalized against the endogenous control 18S.

Epicardial electrograms from isolated hearts.

Hearts were removed and quickly cannulated through the aorta and Langendorff-perfused with Krebs-Henseleit buffer solution containing the following (in mM): 118 NaCl, 4.7 KCl, 1.2 KH2PO4, 1.2 MgSO4, 1.8 CaCl2, 25 NaHCO3, and 11.1 glucose, (pH 7.4), bubbled with 95% O2-5% CO2 at 35 ± 1 °C. A bimodular amplifier (Biopac MP System) was used to record atrial and ventriclar epicardial electrical activity from a total of six chlorinated electrodes placed on the heart, as previously described (9). A third module was a stimulator controlled by a computer to deliver programmed fast pacing stimuli with S1 cycle lengths ranging from 80 to 40 ms followed by three extra-stimuli S1-S2-S3 delivered at a coupling interval of 30–20 ms. Stimuli were delivered to the right atrium to induce AF (1).

Atrial myocytes isolation.

Atrial cells were isolated from Langendorff-perfused hearts. The heart was perfused with nominally Ca2+-free Tyrode solution containing the following (in mM): 137 NaCl, 5.4 KCl, 1 MgCl2, 0.33 NaH2PO4, 10 HEPES, and 10 glucose (pH 7.4) equilibrated with 100% O2 (35 ± 1°C). After the blood was washed out, collagenase type-2 (1 mg/ml; Worthington, Biochemical), protease type XIV (0.02 mg/ml; Sigma), and elastase (0.2 mg/ml; Worthington, Biochemical) were added to the perfusion solution. When the hearts became dilated, the left ventricle was removed and the myocytes were allowed to disperse in solution. Ventricular myocytes were subjected to Ca2+ readaptation and finally resuspended in Tyrode solution (1 mM CaCl). The right atrium was quickly removed and allowed to digest for an additional 5–15 min in the solution containing the enzymes. The tissue was transferred into the KB-recovery solution containing the following: 70 mM/l l-glutamic acid, 20 mM/l KCl, 80 mM/l KOH, 10 mM/l (±)-β-OH-butyric acid, 10 mM/l KH2PO4, 10 mM/l taurine, 1 mg/ml BSA, and 10 mM/l HEPES-K (adjusted to pH 7.4 with KOH). After 40 min, cells were dispersed in the same solution. Na+ and Ca2+ were reintroduced by the addition of a solution containing the following: 10 mM NaCl, 1.8 mM CaCl2, and 1 mg/ml BSA. Cells were finally stored in a solution containing the following: 100 mM NaCl, 35 mM KCl, 1.3 mM CaCl2, 0.7 mM MgCl2, 14 mM l-glutamic acid, 2 mM β-OH butyric acid, 2 mM KH2PO4, 2 mM taurine, and 1 mg/ml BSA (pH 7.4) and were used within 4 h after the isolation (15).

Patch-clamp recordings.

Whole cell configuration of the patch-clamp technique was used for ion current recordings. Cells were first superperfused with Tyrode solution, and then the perfusion was switched to the appropriate solution for each current studied as previously described (7). All experiments were conducted at room temperature. Briefly, for ICa-L and ICa-T, Na+ and K+ were substituted by equimolar concentration of tetraethylammonium (TEA−) and cesium (Cs+) respectively. Niflumic acid (30 μM) and 4-aminopyridine (4-AP; 1 mM) were added to block chloride and K+ currents; cobalt (5 mM) was added during ICa-T recording (27). Pipette solution for ICa-L and ICa-T recordings contained (in mM): 110 Cs-aspartate, 20 CsCl, 1 MgCl2, 10 EGTA, 10 HEPES, 5 Mg-AT, and 0.5 Tris-GTP (pH 7.4) with CsOH. The ICa-L was activated by a series of 250-ms depolarization pulses from −90 mV holding potential (HP) to test potentials ranging from −50 mV to +60 (10-mV step) at 10-s intervals. The ICa-T was elicited by 250-ms depolarizing pluses (10-mV step) from a HP of −90 mV to +60 mV. The external solution for INa recordings contained (in mM): 60 N-methyl glucosamine, 60 NaCl, 10 CsCl, 1.8 CaCl2, 1 MgCl2, 10 HEPES, and 10 glucose (pH 7.4, with CsOH). ICa-L and ICa-T were blocked by CoCl2 (5 mM) and NiCl2 (1 mM), respectively. The internal solution contained (in mM): 135 CsOH, 135 l-aspartic acid, 1 MgCl2, 10 EGTA, 10 HEPES, 5 Mg-ATP, and 0.1 Na-GTP (pH 7.2, CsOH). INa was evoked with 30-ms duration pulses to +30 mV from a HP of −90 mV at 5-s intervals.

For Ito, If, and IK current recording, the extracellular solution was adjusted as follows. The IK and the Ito were blocked with 4-AP (0.5 mM); the ICa-L was blocked with verapamil (10 μM). IK was elicited by step membrane depolarization from −50 mV to +60 mV. Ito was studied in the presence of TEA-Cl and CdCl2 (200 μM), and current was elicited by step depolarization from −50 mV to +60 mV. The hyperpolarization-activated current (If) was studied by adding BaCl2 (1 mM) to the external solution, and the membrane was then hyperpolarized from −20 mV to −130 mV. The standard pipette solution contained (in mM): 110 K-aspartate, 20 KCl, 2 CaCl2, 1 MgCl2, 0.1 GTP, 5 Mg2-ATP, 5 Na2-phosphocreatine, 10 EGTA, and 10 HEPES (pH 7.3, with KOH). Data were sampled with an A/D converter (Digital 1320A, Axon Instruments) and stored on the hard disk of a computer for subsequent analysis.

Measurement of [Ca2+]iT and SR Ca2+ loading.

The [Ca2+]iT was recorded in isolated right atrial myocytes loaded with fura 2-AM (5 μM, 15 min; Invitrogen). Measurements started at least 30 min after fura 2 was removed to allow the complete dye deesterification. Drops containing cells were placed in a perfusion chamber mounted in an inverted microscope (Nikon) and were continuously superfused with Tyrode solution at 35°C. The [Ca2+]iT was evoked by electrical field-stimulation (square pulses 3–5 ms duration at rate of 0.5 Hz). Fluorescence was measured using a photomultiplier (DeltaRam, Photon Technology International).

Caffeine was used to release SR Ca2+ and thus estimate SR Ca2+ content. The Na+ and Ca2+ were not included in the caffeine solution to minimize extrusion of Ca2+ by the Na+/Ca2+ exchanger. Caffeine was applied locally by pressure ejection through a pipette positioned near the cell (200 μm) after the cells were electrically stimulated at steady state to allow homogeneous (SR) Ca2+ loading.

Statistical analyses.

Data are means ± SD. Experimental data from the α1D KO mice and WT controls were compared by unpaired Student's t-test. A value of P < 0.05 was considered to be statistically significant; n represents the number of cardiomyocytes or hearts.

RESULTS

ECG recordings.

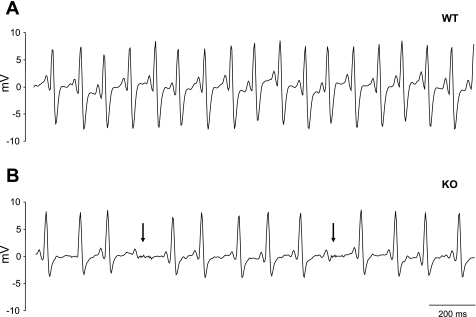

Surface ECGs were obtained from a total of 15 α1D KO and 15 WT anesthetized mice. Representative ECG recordings are illustrated in Fig. 1. The recording from the WT mouse shows a sinus rhythm with regular P-QRS complex (Fig. 1A). However, the ECG from the α1D KO mice shows sinus bradycardia and blocked atrial impulses, which failed to propagate to the ventricle (AV block; Fig. 1B). Averaged data demonstrated significant sinus bradycardia in the α1D KO mice (46.1% ± 15.4 reduction in beats/min, P < 0.01). In the α1D KO mice, ECG analysis shows that P-wave amplitude was depressed and prolonged and that P-R interval was also prolonged (Table 1). The mean QRS duration was not different in the two groups. Three out of 15 α1D Ca channel KO mice showed spontaneous episodes of atrial arrhythmia. These spontaneous episodes were not seen in any of the WT mice.

Fig. 1.

Representative surface ECG recordings from anesthetized mice. A: wild-type (WT) mouse ECG, showing sinus rhythm (heart rate 571 beats/min) with a regular P-QRS complex. B: ECG from α1D Ca2+ channel knockout (KO) mouse with pronounced sinus bradycardia (375 beats/min). Arrowheads illustrate atrial activity failing to propagate into the ventricle [atrioventricular (AV) block].

Table 1.

Electrocardiographic parameters in anesthetized WT and α1D channel KO mice

| Parameters | WT | KO |

|---|---|---|

| Heart rate, beats/min | 551.2+58.6 | 303.5+72.4* |

| P-R interval, ms | 33.5+2.02 | 45.1+2* |

| P-wave duration, ms | 25.3+1.0 | 30.8+1.0* |

| P-wave amplitude, mV | 2.24+0.03 | 1.26+0.06* |

Data are means ± SD. WT, wild type; KO, knockout.

P < 0.05.

Electrograms from isolated hearts and induction of AF in α1D KO mice.

To rule out potential interferences from neural innervations and/or anesthesia, we conducted studies in isolated Langendorff-perfused hearts. All the atrial abnormalities observed in vivo were still present in isolated α1D Ca2+ channel KO mice hearts (n = 5), but none were found in WT mice hearts (n = 5), suggesting that the electrical abnormalities are intrinsic to the heart and reinforcing the hypothesis that α1D Ca2+ channel is necessary for the normal genesis and conduction of the electrical impulse. Sinus bradycardia was detected in the α1D Ca2+ KO hearts (205 ± 17 beats/min; n = 5) compared with WT mice hearts (309 ± 20 beats/min; n = 8; P < 0.01).

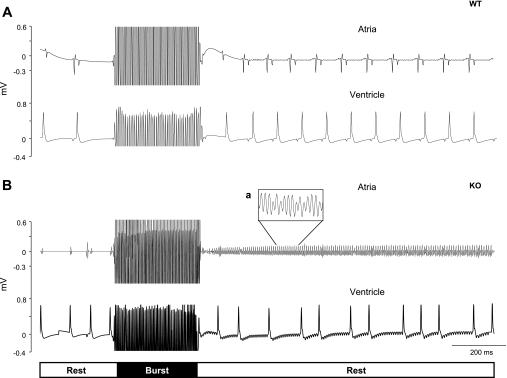

Programmed electrical stimulation (burst stimulation and extrasystolic beats, combined) was delivered in the right atria to induce AF. AF was readily inducible in all α1D Ca2+ channel KO hearts but in none of the WT mice hearts. Representative ECG traces from a WT mouse heart in sinus rhythm before and after burst stimulation is shown in Fig. 2A. In contrast, application of the same burst stimulation protocol resulted in inducible AF/tachycardia (Fig. 2B) in α1D Ca2+ channel KO mice hearts (5 out of 5). During AF, the atrial rate was much faster than the ventricular rate, with a median fibrillation interval of ∼60 milliseconds (Fig. 2B). Irregular and slow ventricular rhythm can be also observed during AF (Fig. 2B). The episodes of AF spontaneously converted after 125 ± 66 s to sinus rhythm.

Fig. 2.

Epicardial ECG and rapid pacing (burst) in isolated hearts applied at the S1 cycle length of 40 ms followed by 3 extra-stimuli S1-S2-S3 at 30 ms. Recordings electrodes were placed in each heart chamber free walls, and stimulator electrodes are placed in the right atria. A: representative epicardial ECG recording from a WT mouse heart, sinus rhythm is evident before and after the burst stimulation. B: burst stimulation of the heart from α1D Ca2+ channel KO mouse resulted in induced AF and irregular ventricular response. Expanded view of the uncoordinated atrial activities is shown in inset.

Patch-clamp recordings from atrial cells.

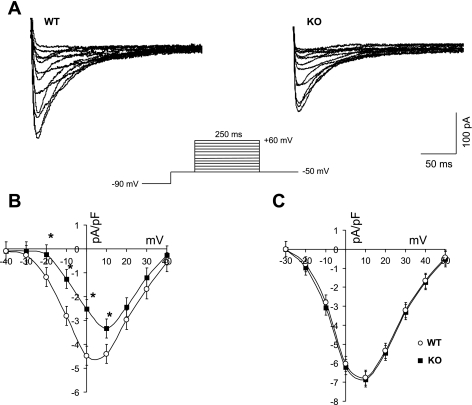

To determine the relative contribution of the α1D Ca2+ channel to the total ICa-L in the atria, right atrial cells were isolated and the whole cell recording of ICa-L was performed as shown in Fig. 3A. The capacitance of atrial cells from the KO mice cells was smaller compared with the WT cells [42.13 ± 2.22 pA/pF in KO (n = 26) vs. 50.75 ± 3.25 pA/pF in WT (n = 26); P = 0.05]. The I-V relationship for ICa-L revealed a depolarization shift (13 mV) in the ICa-L peak density in the KO mice cells (Fig. 3B). Atrial myocytes from the KO mice demonstrated a reduced ICa-L peak density (at +10 mV) compared with WT [3.51 ± 0.3 pA/pF in KO (n = 18) vs. 4.65 ± 0.2 pA/pF in WT (n = 25); P < 0.05]. This finding indicates that the I-V relationship generated from α1D Ca2+ channel KO atrial cell is represented only by the α1C subunit of the L-type Ca2+ channel. Interestingly, the I-V relationship from ventricular cells did not show any changes in the ICa-L density between the WT and the α1D Ca2+ channel KO mice (Fig. 3C).

Fig. 3.

Membrane ion currents in single cardiomyocytes isolated from the right atria of WT and KO mice. A: selected ICa-L tracings of atrial myocytes from WT (left) and α1D Ca2+ channel KO (right) mice. B: current-voltage (I-V) relationship showing a reduction of ICa-L density in α1D Ca2+ channel KO (▪) atrial myocytes compared with the WT (○). The I-V peak is shifted rightward in α1D Ca2+ channel KO cells (∼13 mV). C: I-V relationship of α1D Ca2+ channel ICa-L density from ventricular myocytes of the WT (○) and KO (▪) mice. The voltage protocol used to generate the I-V relationship is shown in the inset. *P < 0.05.

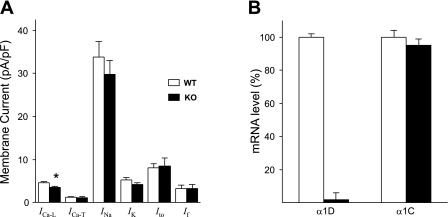

To investigate whether the deletion of α1D Ca2+ channel may have resulted in changes (i.e., compensatory mechanisms) of other major atrial ion currents (17, 21), we recorded INa, ICa-T, IK, If, and Ito from both groups (Table 2). Current densities were not significantly different between WT and α1D Ca2+ channel KO mice, indicating that deletion of α1D Ca2+ channel did not result in compensation from the major currents we measured (Fig. 4A). Because the deletion of α1D Ca2+ channel might result in altered expression of the α1C Ca2+ channel (16), we used real-time PCR to assess the levels of α1C Ca2+ channel mRNA. The transcript for α1D was detected in the atria of the WT but not in the α1D Ca2+ channel KO mice. The deletion of the α1D Ca2+ channel gene did not result in any significant changes in the α1C Ca2+ channel mRNA level in α1D Ca2+ channel KO mice (Fig. 4B). This further supports the conclusion that the decrease in ICa-L observed in the α1D Ca2+ channel mice was attributable to the deletion of α1D Ca2+ channel.

Table 2.

Averaged ion current densities of atrial cells from WT and α1D Ca2+ channel KO mice

| Density Peak at mV | WT | KO | P Value |

|---|---|---|---|

| ICaL at +10 | 4.65+0.2 (25) | 3.51+0.3*(18) | P=0.039 |

| ICaT at −10 | 1.24+0.2 (5) | 1.1+0.3 (4) | P=0.95 |

| INa at −20 | 33.8+3.6 (6) | 29.80+3.2 (6) | P=0.86 |

| IK at +60 | 5.32+0.54 (8) | 4.17+0.44 (8) | P=0.50 |

| Ito at +60 | 8.12+0.85 (9) | 8.52+1.85 (8) | P=0.96 |

| If at −110 | 3.31+0.73 (3) | 4.30+0.88 (4) | P=0.71 |

Data are means ± SD; no. in parenthesis are no. of animals.

P < 0.05.

Fig. 4.

Bar graphs representing averaged current densities and mRNA levels in right atrial cells from α1D Ca2+ channel (KO) and WT mice. A: summary of several ion current densities from atrial myocytes of KO and WT mice. Only ICa-L density is significantly (P < 0.05) reduced. B: real-time PCR analysis for the relative quantification of α1D and α1C Ca2+ channel mRNA in WT and α1D Ca2+ channel KO mice atria. α1D mRNA level is minimal in the α1D Ca2+ channel KO mice compared with the WT mice. There were no significant changes in α1C mRNA level in α1D Ca2+ channel KO compared with the WT. *P < 0.05.

[Ca2+]i measurements in atrial myocytes.

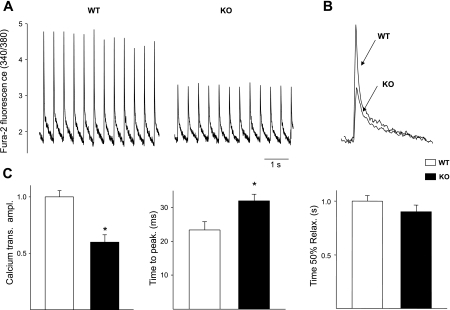

The [Ca2+]iT was monitored in single right atrial cells loaded with fura 2, and [Ca2+]iT was evoked by electrical field stimulation. Representative traces of a single atrial cell from a WT and KO stimulated until steady state are shown (Fig. 5A). A significant reduction of the [Ca2+]iT peak amplitude was observed in all of the α1D KO mice atrial cells compared with the WT atrial cells (40.48 ± 5.02%; n = 13; P < 0.05). This reduction was associated with an increase of the time to peak without alteration of the [Ca2+]iT decay time (Fig. 5C).

Fig. 5.

Representative intracellular Ca2 ([Ca2+]i) transient from fura 2 loaded cells electrically stimulated at 0.5 Hz. A: [Ca2+]i transient original records from WT and α1D Ca2+ channel KO atrial cells. B: normalized and superimposed individual [Ca2+]i transients from a WT and from α1D Ca2+ channel KO show a reduced systolic [Ca2+]i peak in α1D Ca2+ channel KO atrial cells. C: averaged data for [Ca2+]i transient amplitude, time to peak, and time to 50% relaxation. *P < 0.05.

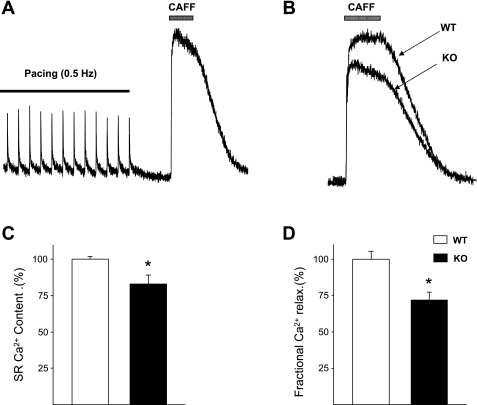

SR Ca2+ load and function in atrial myocytes.

Since the SR Ca2+ store is the main Ca2+ contributor to the [Ca2+]iT in mice (22), we investigated whether the decrease in systolic Ca2+ might reflect a decrease in SR Ca2+ content. Rapid caffeine application (10 mM) to empty the intracellular Ca2+ store in single atrial cells revealed a significant reduction of the SR Ca2+ content in the α1D Ca2+ channel KO cells compared with the WT cells (17 ± 2% reduction; n = 8; P < 0.05; Fig. 6A). Superimposed individual caffeine-induced [Ca2+]iT from a WT and from a KO cell indicates that the SR Ca2+ content in KO cells is less than in WT (Fig. 6B). The average data of caffeine-induced Ca2+ release peak are shown in Fig. 6C. To assess whether the Ca2+-induced Ca2+-release (CICR) might be affected by the α1D Ca2+ channel gene deletion, we measured fractional SR Ca2+ release, defined as the electrically induced Ca2+ released during a single twitch and the total Ca2+ released by caffeine application ([Ca2+]iT twitch/[Ca2+]iT,caffeine). The average fractional Ca2+ release was significantly smaller in the α1D KO cells (28 ± 3%; n = 6; P < 0.05; Fig. 6D). This result suggests an impairment of the CICR in the α1D Ca2+ channel KO atrial cells.

Fig. 6.

Sarcoplasmic (SR) Ca2+ content measured by caffeine application. A: original traces from WT and α1D Ca2+ channel KO atrial cells showing SR Ca2+ content measured by caffeine induced Ca2+ release. Cells were electrically field-stimulated followed by local caffeine pulse (10 mM). B: superimposed individual caffeine-induced Ca2+ transient from WT and α1D Ca2+ channel KO cells showing that the SR Ca2+ content in KO cells is less than in WT. C: average data of peak caffeine-induced Ca2+ release. D: SR fractional Ca2+ release. Data are normalized to facilitate comparison. *P < 0.05.

DISCUSSION

Our results show that α1D Ca2+ channel deletion leads to abnormal electrical activity and AF vulnerability. Furthermore, the results show a reduction of ICa-L density, a reduced intracellular [Ca2+]iT amplitude, and impaired CICR in the α1D Ca2+ channel KO mouse atrial myocytes. These findings may account for the electrocardiographic abnormalities, including AF vulnerability found in these mice.

Electrocardiographic abnormalities of the α1D Ca2+ channel KO mice.

During ECG recordings in KO mice, electrocardiographic abnormalities such as sinus bradycardia, P-wave changes, and AV block were present. The reduced P-wave amplitude and prolonged P-wave duration suggest slower atrial impulse propagation in the α1D Ca2+ channel KO mice atria. Similar ECG abnormalities were found in isolated Langendorff-perfused hearts. Furthermore, isolated hearts from α1D KO mice were prone to AF/tachycardia upon burst stimulation of the right atrium. This evidence suggests that the increased incidence of AF in the α1D Ca2+ channel KO paced heart may be related to intrinsic abnormalities of atrial electrical properties such as intra-atrial or interatrial conduction disturbances. Altogether, the present findings suggest that the α1D Ca2+ channel plays an important role in the maintenance of normal atrial electrical activity.

Ion currents in the α1D Ca2+ channel KO atrial cells.

Reduction of the global ICa-L, which is represented only by α1C in the α1D Ca2+ channel KO mouse, indirectly shows that the α1D Ca2+ channel actively contributes to the Ca2+ influx in atrial myocytes and the CICR mechanism. The patch-clamp results unmasked the different biophysical characteristics between α1C and α1D channels. The latter activates at more negative potentials, consistent with the properties of α1D Ca2+ channel characterized in heterologous expression systems (11, 24). The α1C Ca2+ channel mRNA expression is not altered in the α1D Ca2+ channel KO mice atria, and as indicated by real-time PCR data (Fig. 4B), deletion of α1D Ca2+ channel did not result in α1C transcript level changes. Moreover INa, ICa-T, IK, If, and Ito current densities are not affected by the deletion of the α1D Ca2+ channel in the atrial cells, suggesting no compensatory mechanisms. Altogether, the patch-clamp data further support the unique role of α1D Ca2+ channel in the atria. The reduction of ICa-L density in the α1D Ca2+ channel KO mice is consistent with a reduced total ICa-L density in the SA node cells of the same α1D Ca2+ channel KO mice (15) with no compensatory changes from other currents but is in contrast with others (26) showing no changes in total ICa-L of the α1D Ca2+ channel in KO mice atrial cells. The use of different stimulation/conditioning voltage-clamp protocols used to evoke ICa-L and the differences in the genetic background (18) of the mice used between the two studies may account for the different findings.

[Ca2+]iT in the α1D Ca2+ channel KO atrial cells.

To date, there are no data available regarding the potential contribution of α1D Ca2+ channel to the [Ca2+]iT in single atrial myocytes. The ICa-L reduction in the α1D Ca2+ channel KO mice may account, at least in part, for the significant reduction of the [Ca2+]iT in single atrial cells. Since the main source of Ca2+ during CICR is the SR, the smaller ICa-L cannot be solely responsible for the large [Ca2+]iT decrease. In fact, our results show a concomitant SR Ca2+ load reduction and a smaller fractional SR Ca2+ release. The results obtained indicate that the α1D Ca2+ channel deletion contributes significantly to the [Ca2+]iT and that perturbations of α1D Ca2+ channel can lead to abnormal electrophysiological function of the atria. Moreover, the absence of the α1D Ca2+ channel may result in an inefficient CICR. Giving the interplay between Ca2+ cycling and cellular electrophysiology in arrhythmogenesis, this animal model serves as a valuable research tool for further investigations.

Pathophysiological significance.

Unlike ventricular myocytes, atrial cells do not possess an extensive T-tubule system (8, 13) but exhibit additional ryanodine receptor clusters around the periphery of the atrial cells (3, 6, 14). Two types of ryanodine receptors are found in atrial myocytes: junctional ryanodine receptors, which are located just beneath the sarcolemma and in close proximity to L-type Ca2+ channels, and nonjunctional ryanodine receptors, which are deeper inside the cell. As a consequence (the close apposition of L-type Ca2+ channels and ryanodine receptors), triggering of CICR occurs only at the cell periphery. Because cardiac ryanodine receptors are under local control of a single L-type Ca2+ channel, a change in properties of the L-type channel may have profound consequences on the normal function of CICR. In this study, the important role of the sarcolemmal α1D Ca2+ channel to the atrial Ca2+ homeostasis and to the electrical activity of the atria has been emphasized. The genetic deletion of α1D Ca2+ channel affected time to peak (slower time to peak) of [Ca2+]iT, the amplitude of [Ca2+]iT (reduced amplitude), the Ca2+ content of the SR (reduced SR Ca2+ content), and the fractional Ca2+ release (reduced), all of which are expected to affect Ca2+ homeostasis. The reduced SR Ca2+ load and unchanged decay of the caffeine-induced Ca2+ transient suggest that triggered activity/automaticity are unlikely mechanisms for the increased propensity to atrial arrhythmias. The reduced P-wave amplitude and prolonged P-wave duration, which suggest slower conduction in the α1D Ca2+ channel KO mice atria, and the reduced ICa,L would suggest that reentry susceptibility may be a likely mechanism. Unlike the commonly reported reduction of ICa,L current density due to remodeling after AF has taken place, the present data support the hypothesis that an a priori reduction in ICa,L current density may be involved in the initiation of AF, since deletion of the α1D Ca2+ channel makes the mice prone to AF.

Altogether, the data from the present study open new directions into the characteristic features of the α1D Ca2+ channel in the supraventricular tissue, which may be useful for the development of potential atrial specific therapeutics targeted towards the management of atrial arrhythmias especially AF.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institutes Grant HL-77494, the Veterans Administration Merit Grant Awards to Dr. Boutjdir, and the Veterans Administration Merit Review Entry Program grant to Dr. Qu.

The costs of publication of this article were defrayed in part by the payment of page charges. The article must therefore be hereby marked “advertisement” in accordance with 18 U.S.C. Section 1734 solely to indicate this fact.

REFERENCES

- 1.Berul CI, Aronovitz MJ, Wang PJ, Mendelsohn ME. In vivo cardiac electrophysiology studies in the mouse. Circulation 94: 2641–2648, 1996. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Brundel BJ, van Gelder IC, Henning RH, Tuinenburg AE, Deelman LE, Tieleman RG, Grandjean JG, van Gilst WH, Crijns HJ. Gene expression of proteins influencing the calcium homeostasis in patients with persistent and paroxysmal atrial fibrillation. Cardiovasc Res 42: 443–454, 1999. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Carl SL, Felix K, Caswell AH, Brandt NR, Ball WJ Jr, Vaghy PL, Meissner G, and Ferguson DG. Immunolocalization of sarcolemmal dihydropyridine receptor and sarcoplasmic reticular triadin and ryanodine receptor in rabbit ventricle and atrium. J Cell Biol 129: 672–682, 1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Feinberg WM, Blackshear JL, Laupacis A, Kronmal R, Hart RG. Prevalence, age distribution, and gender of patients with atrial fibrillation. Analysis and implications. Arch Intern Med 155: 469–473, 1995. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Gaborit N, Steenman M, Lamirault G, Le Meur N, Le Bouter S, Lande G, Leger J, Charpentier F, Christ T, Dobrev D, Escande D, Nattel S, Demolombe S. Human atrial ion channel and transporter subunit gene-expression remodeling associated with valvular heart disease and atrial fibrillation. Circulation 112: 471–481, 2005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Hatem SN, Benardeau A, Rucker-Martin C, Marty I, de Chamisso P, Villaz M, Mercadier JJ. Different compartments of sarcoplasmic reticulum participate in the excitation-contraction coupling process in human atrial myocytes. Circ Res 80: 345–353, 1997. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Hu K, Qu Y, Yue Y, Boutjdir M. Functional basis of sinus bradycardia in congenital heart block. Circ Res 94: e32–38, 2004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Huser J, Lipsius SL, Blatter LA. Calcium gradients during excitation-contraction coupling in cat atrial myocytes. J Physiol 494: 641–651, 1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Knollmann BC, Katchman AN, Franz MR. Monophasic action potential recordings from intact mouse heart: validation, regional heterogeneity, and relation to refractoriness. J Cardiovasc Electrophysiol 12: 1286–1294, 2001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kollmar R, Montgomery LG, Fak J, Henry LJ, Hudspeth AJ. Predominance of the alpha1D subunit in L-type voltage-gated Ca2+ channels of hair cells in the chicken's cochlea. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 94: 14883–14888, 1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Koschak A, Reimer D, Huber I, Grabner M, Glossmann H, Engel J, Striessnig J. Alpha 1D (Cav1J.3) subunits can form l-type Ca2+ channels activating at negative voltages. J Biol Chem 276: 22100–22106, 2001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Lai LP, Su MJ, Lin JL, Lin FY, Tsai CH, Chen YS, Huang SK, Tseng YZ, Lien WP. Down-regulation of L-type calcium channel and sarcoplasmic reticular Ca(2+)-ATPase mRNA in human atrial fibrillation without significant change in the mRNA of ryanodine receptor, calsequestrin and phospholamban: an insight into the mechanism of atrial electrical remodeling. J Am Coll Cardiol 33: 1231–1237, 1999. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Lipp P, Huser J, Pott L, Niggli E. Spatially non-uniform Ca2+ signals induced by the reduction of transverse tubules in citrate-loaded guinea-pig ventricular myocytes in culture. J Physiol 497: 589–597, 1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Mackenzie L, Bootman MD, Berridge MJ, Lipp P. Predetermined recruitment of calcium release sites underlies excitation-contraction coupling in rat atrial myocytes. J Physiol 530: 417–429, 2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Mangoni ME, Couette B, Bourinet E, Platzer J, Reimer D, Striessnig J, Nargeot J. Functional role of L-type Cav1.3 Ca2+ channels in cardiac pacemaker activity. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 100: 5543–5548, 2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Matthes J, Yildirim L, Wietzorrek G, Reimer D, Striessnig J, Herzig S. Disturbed atrio-ventricular conduction and normal contractile function in isolated hearts from Cav1.3-knockout mice. Naunyn Schmiedebergs Arch Pharmacol 369: 554–562, 2004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Morad M, Chau M. Learning about cardiac calcium signaling from genetic engineering. Ann NY Acad Sci 1015: 1–15, 2004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Namkung Y, Skrypnyk N, Jeong MJ, Lee T, Lee MS, Kim HL, Chin H, Suh PG, Kim SS, Shin HS. Requirement for the L-type Ca(2+) channel alpha(1D) subunit in postnatal pancreatic beta cell generation. J Clin Invest 108: 1015–1022, 2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Platzer J, Engel J, Schrott-Fischer A, Stephan K, Bova S, Chen H, Zheng H, Striessnig J. Congenital deafness and sinoatrial node dysfunction in mice lacking class D L-type Ca2+ channels. Cell 102: 89–97, 2000. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Qu Y, Baroudi G, Yue Y, Boutjdir M. Novel molecular mechanism involving alpha1D (Cav1.3) L-type calcium channel in autoimmune-associated sinus bradycardia. Circulation 111: 3034–3041, 2005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Takahashi E, Nagasu T. Pattern of compensatory expression of voltage-dependent Ca2+ channel alpha1 and beta subunits in brain of N-type Ca2+ channel alpha1B subunit gene-deficient mice with a CBA/JN genetic background. Exp Anim 54: 29–36, 2005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Terracciano CM, Souza AI, Philipson KD, MacLeod KT. Na+-Ca2+ exchange and sarcoplasmic reticular Ca2+ regulation in ventricular myocytes from transgenic mice overexpressing the Na+-Ca2+ exchanger. J Physiol 512: 651–667, 1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Van Wagoner DR, Pond AL, Lamorgese M, Rossie SS, McCarthy PM, Nerbonne JM. Atrial L-type Ca2+ currents and human atrial fibrillation. Circ Res 85: 428–436, 1999. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Xu W, Lipscombe D. Neuronal Ca(V)1.3alpha(1) L-type channels activate at relatively hyperpolarized membrane potentials and are incompletely inhibited by dihydropyridines. J Neurosci 21: 5944–5951, 2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Yue L, Feng J, Gaspo R, Li GR, Wang Z, Nattel S. Ionic remodeling underlying action potential changes in a canine model of atrial fibrillation. Circ Res 81: 512–525, 1997. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Zhang Z, He Y, Tuteja D, Xu D, Timofeyev V, Zhang Q, Glatter KA, Xu Y, Shin HS, Low R, Chiamvimonvat N. Functional roles of Cav1.3(alpha1D) calcium channels in atria: insights gained from gene-targeted null mutant mice. Circulation 112: 1936–1944, 2005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Zhang ZH, Johnson JA, Chen L, El-Sherif N, Mochly-Rosen D, Boutjdir M. C2 region-derived peptides of beta-protein kinase C regulate cardiac Ca2+ channels. Circ Res 80: 720–729, 1997. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]