Abstract

Mast cells are found in the heart and contribute to reperfusion injury following myocardial ischemia. Since the activation of A2A adenosine receptors (A2AARs) inhibits reperfusion injury, we hypothesized that ATL146e (a selective A2AAR agonist) might protect hearts in part by reducing cardiac mast cell degranulation. Hearts were isolated from five groups of congenic mice: A2AAR+/+ mice, A2AAR−/− mice, mast cell-deficient (KitW-sh/W-sh) mice, and chimeric mice prepared by transplanting bone marrow from A2AAR−/− or A2AAR+/+ mice to radiation-ablated A2AAR+/+ mice. Six weeks after bone marrow transplantation, cardiac mast cells were repopulated with >90% donor cells. In isolated, perfused hearts subjected to ischemia-reperfusion injury, ATL146e or CGS-21680 (100 nmol/l) decreased infarct size (IS; percent area at risk) from 38 ± 2% to 24 ± 2% and 22 ± 2% in ATL146e- and CGS-21680-treated hearts, respectively (P < 0.05) and significantly reduced mast cell degranulation, measured as tryptase release into reperfusion buffer. These changes were absent in A2AAR−/− hearts and in hearts from chimeric mice with A2AAR−/− bone marrow. Vehicle-treated KitW-sh/W-sh mice had lower IS (11 ± 3%) than WT mice, and ATL146e had no significant protective effect (16 ± 3%). These data suggest that in ex vivo, buffer-perfused hearts, mast cell degranulation contributes to ischemia-reperfusion injury. In addition, our data suggest that A2AAR activation is cardioprotective in the isolated heart, at least in part by attenuating resident mast cell degranulation.

Keywords: Langendorff, tryptase, ATL146e, CGS-21680, bone marrow chimera

mast cells contribute to immune responses with both sentinel and effector roles in host defense and inflammation. The activation of mast cells has been found to have protective or deleterious effects in response to tissue infection or injury (22, 29). This is due in part to tissue-specific heterogeneity of mast cell function (3, 48). In the heart, degranulation of resident cardiac mast cells mediates injurious effects during experimental ischemia-reperfusion (I/R) injury and myocardial infarction (MI). These deleterious effects are mediated by multiple mechanisms, including a local renin-angiotensin axis (18, 26, 41), histamine and prostanoid-induced ventricular arrhythmogenesis (36), and the initiation of a cytokine cascade resulting in increased ICAM-1 expression and neutrophil extravasation (13, 42). In addition, resident cardiac mast cells contribute to the ventricular hypertrophic response during chronic cardiac volume overload (6, 16, 32, 33). In the isolated heart, oxidative stress from I/R is sufficient to stimulate degranulation of resident cardiac mast cells (13). Mast cell stabilizers such as ketotifen and low-dose carvedilol attenuate I/R-induced myocardial injury (15).

Adenosine or adenosine analogs such as 5′-N-ethylcarboxamideadenosine or N6-(3-iodobenzyl)-adenosine-5′-N′-methyluronamide primarily use the A3 adenosine receptor (AR) to stimulate degranulation of rat or murine mast cells, whereas the A2BAR is the principle activator of primed canine or human mast cells (2, 9, 23, 40, 47, 52). In some, but not all, mast cells, A2AAR activation reduces degranulation and migration by inhibiting the Ca2+-activated K+ channel KCa3.1s (8, 17). The effect of A2AAR agonism on in vivo murine cardiac mast cells is unknown. In vivo, A2AAR activation during reperfusion following coronary artery occlusion reduces mouse heart reperfusion injury by preventing lymphocyte uptake and activation (50). Here, we demonstrate that A2AAR activation inhibits cardiac mast cell degranulation. A2AAR activation or mast cell depletion protects the buffer-perfused isolated mouse heart from reperfusion injury, suggesting that mast cell degranulation contributes to reperfusion injury.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Animals.

Mouse experiments were approved by the University of Virginia Animal Care and Use Committee. A2AAR+/+ [wild type (WT)], KitW-sh/W-sh (mast cell deficient), and ubiquitous green fluorescent protein (uGFP) mice congenic with C57BL/6J were purchased from Jackson Laboratory. A2AAR−/− mice from Jiang-Fan Chen (Boston University) were moved onto a C57BL/6J background.

Isolated, perfused mouse hearts.

Metabolic, cellular, and functional responses to I/R injury were assessed using the isolated, perfused mouse heart as previously described (20). Adult male mice (10–12 wk old, 20 ± 5 g) were anesthetized with pentobarbital sodium, and hearts were excised and placed in ice-cold heparinized perfusion buffer. Hearts were retrograde perfused via an aortic cannula with a modified Krebs-Henseleit buffer [containing (in mmol/l) 118 NaCl, 25 NaHCO3, 4.7 KCl, 1.2 KH2PO4, 2.5 CaCl2, 1.2 MgSO4, 11 glucose, and 0.6 EDTA equilibrated with 95% O2-5% CO2 to an end Po2 of 550 ± 50 mmHg]. Coronary perfusate flow was continuously monitored by an in-line ultrasonic flow probe (Transonic Systems, Ithaca, NY). Following 10 min of equilibration, hearts were paced for an additional 10 min at 425 beats/min via an electrode at the base of the right ventricle.

Experimental protocol.

After 20 min of equilibration, pacing was halted, and hearts were subject to 30 min of global ischemia followed by 30 min of reperfusion as previously described (1). Vehicle, CGS-21680 (final concentration: 100 nmol/l; Fig. 1), or ATL146e (final concentration: 100 nmol/l; Adenosine Therapeutics Group, Charlottesville, VA; Fig. 1) was infused at a 1% coronary perfusate flow rate throughout the reperfusion interval. Samples of coronary perfusate effluent (500 ± 50 μl) were collected at baseline and at 1, 2, 5, 10, 15, 20, 25, and 30 min of reperfusion for tryptase analysis (Fig. 2). Following reperfusion, hearts were stained with 1.5% triphenyltetrazolium chloride in PBS (37°C) to determine infarct size (IS). IS was expressed as the percent area at risk (AAR), where the AAR was considered to be the entirety of the left ventricle (global myocardial ischemia).

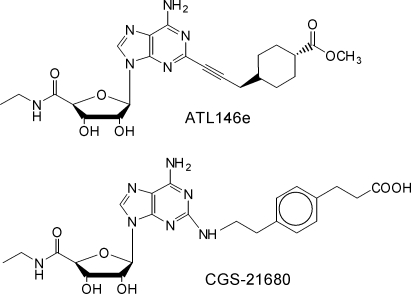

Fig. 1.

Chemical formulas of ATL146e and CGS-21680. Mast cells were subsequently cultured from dissociated lung pieces.

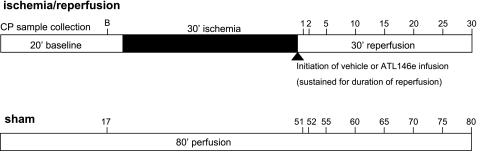

Fig. 2.

Schematic of the isolated, perfused mouse heart protocol. Isolated hearts were subjected to either an 80-min perfusion (sham) or an ischemia-reperfusion (I/R) protocol. ATL146e or vehicle infusion was initiated in I/R hearts at the onset of reperfusion. Numbers indicate time points for coronary perfusate (CP) sample collection. B, baseline (preischemia) collection period.

Tryptase release.

Coronary effluent samples were analyzed for tryptase content enzymatically as described by Lavens et al. (21). Briefly, 50 μl of coronary effluent perfusate were incubated with 50 μl of 0.8 mmol/l α-N-benzoyl-l-arginine-p-nitroanilide (up to 72 h at 37°C), and the nitroaniline product was measured colorimetrically at 405 nm (Wallac 1420 VICTOR2 plate reader, Perkin-Elmer, Waltham, MA). All samples and standards were run in duplicate, and tryptase values were calculated as micrograms per minute per gram of tissue. Values are expressed as percent changes from the preischemic baseline.

Bone marrow transplantation.

Irradiated (600 rad twice at two 4-h intervals) 6-wk-old WT mice served as recipients for bone marrow transplantation as previously described (7). Donor mice (WT, A2AAR−/−, or uGFP C57Bl/6 mice) were anesthetized with pentobarbital sodium and killed. Marrow from tibia and femur was harvested by flushing the marrow cavity with RPMI-1640 medium (Invitrogen) plus 10% FBS to obtain a suspension of ∼5 × 107 nucleated cells. Subsequent to irradiation, 3 × 106 previously harvested bone marrow cells were injected into the jugular vein of each mouse. Transplanted mice were were fed chow containing 5 mM sulfamethoxazole and 0.86 mM trimethorprim and allowed to recover for 6 wk before experimentation. This procedure has consistently produced turnover of >85% circulating lymphocytes and >95% circulating granulocytes (7).

Isolation of primary mast cells.

To assess the extent of mast cell turnover in various tissues, mouse primary peritoneal mast cells (mPPMC) as well as mouse primary lung mast cells (mPLMC) and mouse primary heart mast cells (mPHMC) were derived from bone marrow chimeric (BMC) mice where either uGFP or WT bone marrow was reconstituted into radiation-ablated WT mice. mPPMCs were collected by peritoneal lavage with 10 ml PBS. For the isolation of mPLMCs, mice were anesthetized, and a complete thoracotomy was performed. The pulmonary vasculature was perfused with 10 ml of saline, and the right and left lung lobes were removed and mechanically dissociated. The dissociated tissue was diluted with 10 ml PBS and placed on ice (52).

Isolation of mPHMCs was performed as previously described (10). Ventricular tissue was manually dissociated and incubated in 160 U/ml collagenase type II, 100 U/ml hyaluronidase, 1 U/ml pronase E, and 304 U/ml DNAse I in PBS at 37°C. Supernatants collected after three 15- to 30-min digestion intervals were filtered through 70-μm nylon mesh and subsequently washed with PBS. Pooled cells were combined and washed twice in PBS.

Primary mast cell cultures.

mPPMCs, mPLMCs, and mPHMCs were cultured in DMEM containing 10 ng/ml stem cell factor and 10 ng/ml IL-3; culture media were changed every other day for 1 wk (25, 52). Nonadherent cells were collected and transferred to fresh media. Cells were passaged in the same manner for 6 wk, at which time the population of granular cells that had grown out was analyzed by flow cytometry.

Immunostaining for flow cytometry.

After 6 wk in culture, mPPMCs, mPLMCs, and mPHMCs were washed twice with PBS (1% BSA) and resuspended at 107 cells/ml in staining buffer (1% BSA and 0.1% sodium azide in PBS). Aliquots were labeled with anti-mouse CD45 (Becton Dickinson) and anti-mouse CD117 and anti-mouse FCɛRI (eBioscience). Control samples were labeled with isotype-matched control antibodies. PBS (1 ml) was added along with the Aqua Live/Dead Fixable Dead Cell Stain Kit (Molecular Probes, Eugene, OR) for an additional 30 min. Stained cells were washed, fixed (1% paraformaldehyde in PBS), and resuspended. Fluorescence intensity was measured with a CyAn ADP LX 9 Color analyzer (DakoCytomation, Glostrup, Denmark). Analysis was performed with FlowJo software (Tree Star, Ashland, OR). Cell gates were created based on fluorescence minus one staining and live CD45-positive cells were gated on for analysis. Mast cells found in the live cell CD45-positive gate were identified as CD117 positive and FCɛRI positive.

Radioligand binding for AR subtype specificity.

Radioligand binding to recombinant human and mouse AR subtypes was performed as described by Murphree et al. (31).

Statistics.

For IS determination, all groups were compared using one-way ANOVA with a post hoc Student-Newman-Keuls multiple-comparison test. For tryptase analysis, all groups were compared using two-way ANOVA with a Bonferroni post test. For all tests, significance was established at P < 0.05.

RESULTS

Effects of ATL146e and CGS-21680 in A2AAR+/+ and A2AAR−/− mice.

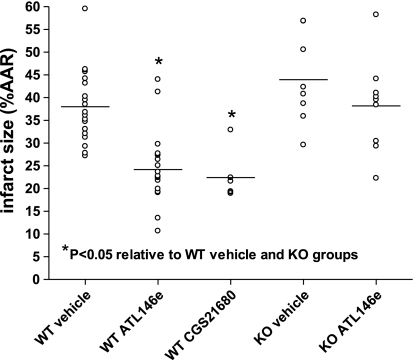

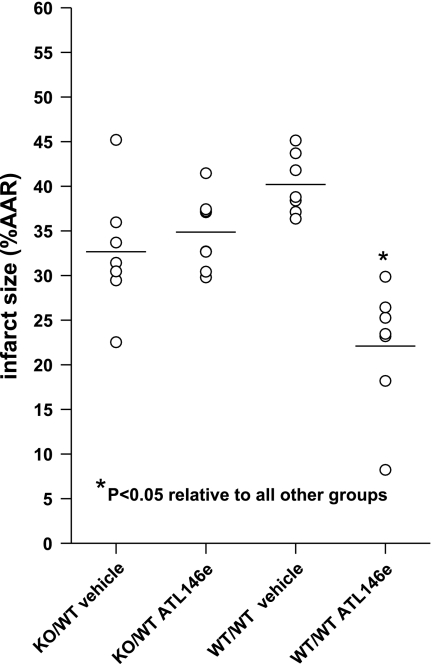

ATL146e and CGS-21680 at 100 nmol/l final concentrations did not cause any changes in coronary conductance (as measured by coronary perfusion flow rate) at any recorded time period in any experimental group (data not shown). When administered during reperfusion, ATL146e and CGS-21680 significantly decreased IS in WT mice (Fig. 3) from 38 ± 2% ARR to 24 ± 2% and 22 ± 2% AAR in ATL146e- and CGS-21680-treated hearts, respectively (P < 0.05). This effect was absent in A2AAR−/− mice, as ISs between vehicle- and ATL146e-treated animals were similar (44 ± 4% AAR vs. 38 ± 3% AAR in vehicle- and ATL146e-treated hearts, respectively; Fig. 3).

Fig. 3.

Infarct sizes (ISs) in vehicle-, ATL146e-, and CGS-21680-treated A2A adenosine receptor (A2AAR)+/+ and A2AAR−/− hearts. Treatment with either ATL146e or CGS-21680 significantly decreased IS in A2AAR+/+ [wild type (WT)] hearts (P < 0.05), but ATL146e had no effect in A2AAR−/− [knockout (KO)] hearts. IS is presented as the percent area at risk (%AAR). n = 20 vehicle-treated WT hearts, 20 ATL146e-treated WT hearts, 8 CGS-21680-treated hearts, 8 vehicle-treated KO hearts, and 8 ATL146e-treated KO hearts. *P < 0.05 by one-way ANOVA.

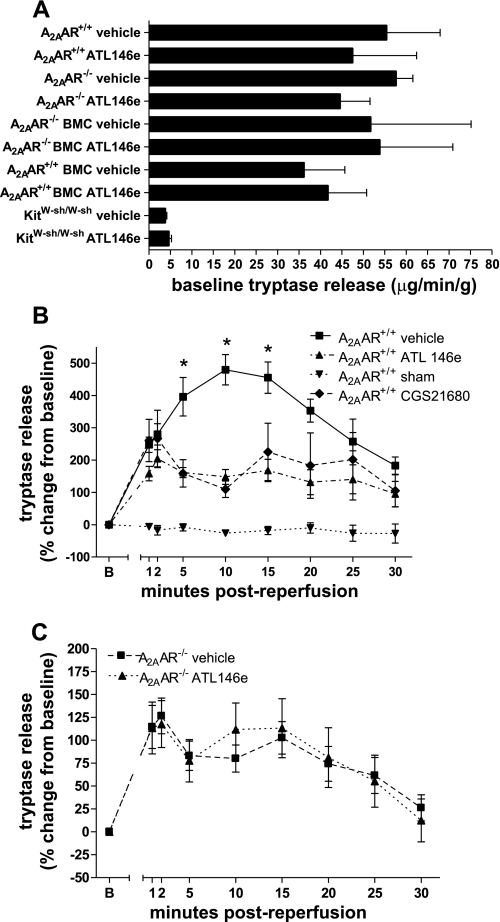

Tryptase release was not significantly different at baseline between WT and A2AAR−/− groups (Fig. 4A). However, baseline tryptase release was decreased in hearts from both vehicle- and ATL146e-treated KitW-sh/W-sh groups compared with hearts from mice with functional mast cells. ATL146e or CGS-21680 treatment significantly decreased tryptase release during reperfusion in WT hearts compared with vehicle-treated controls (Fig. 4B). ATL146e treatment had no effect in A2AR−/− mice, confirming that the effects of ATL146e are mediated through the A2AAR (Fig. 4C). Interestingly, the peak tryptase release in vehicle-treated groups was significantly lower in A2AAR−/− mice compared with WT mice, possibly due to chronic stimulation of mast cells lacking inhibitor ARs.

Fig. 4.

Tryptase release at baseline and during I/R in A2AAR+/+ and A2AAR−/− hearts. A: tryptase release at baseline was similar in all groups except KitW-sh/W-sh hearts. BMC, bone marrow chimeric mice. B and C: effect of ATL146e or CGS-21680 treatment on tryptase release in A2AAR+/+ (B) and A2AAR−/− hearts (C) during reperfusion. *P < 0.05 relative to all other groups by two-way ANOVA with the Student-Neuman-Keuls post test.

Mast cell turnover in BMC mice.

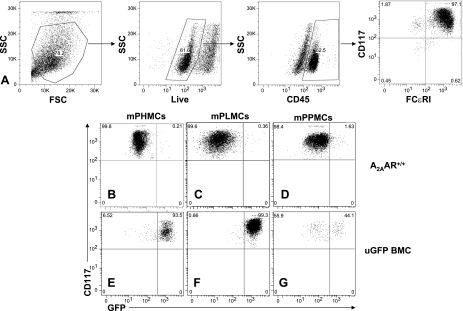

We conducted bone marrow transplantation experiments to selectively delete the A2AAR in bone marrow-derived cells (including mast cells). Since the turnover rate of murine cardiac mast cells was unknown, we examined the efficiency of mast cell repopulation using mice ubiquitously expressing GFP (uGFP) as the source of donor marrow. After mast cells had been harvested from the heart and other tissues, they were expanded in culture, and the fraction of GFP-positive cells was determined by flow cytometry. Cytometry was also performed on identical cultures that were derived from mice where bone marrow from WT mice had been transplanted to ablated WT mice. As shown in Fig. 5A, CD45-positive, FCɛRI-positive, and CD117-positive (triple positive) cells were identified as mast cells.

Fig. 5.

Flow cytometry of cultured heart, peritoneal, and lung mast cells. A: gating strategy for identifying mast cells. Only live CD45-positive, CD117-positive, and FCɛRI-positive cells were identified as mast cells. CD117 and GFP positivity were assessed in A2AAR+/+ (B–D) and ubiquitous green fluorescent protein (uGFP) BMC (E–G) mouse primary heart mast cells (mPHMCs; B and E), mouse primary lung mast cells (mPLMCs; C and F), and mouse primary peritoneal mast cells (mPPMCs; D and G). For both mPHMCs and mPLMCs, cultured cells from uGFP BMC mice were GFP positive in >90% of all cells, whereas <50% of all cells from the peritoneum (mPPMCs) of uGFP mice were GFP positive.

In bone marrow transplanted mice that received WT bone marrow, nearly all mast cells were confirmed to be GFP negative (Fig. 5, B–D). Conversely, in bone marrow transplanted mice that received uGFP bone marrow, the majority of mast cells derived from the heart and lung were GPF positive, whereas peritoneal-derived mast cells were less than half GFP positive. The percentage of GFP-positive cells was 93.5% in mPHMCs (Fig. 5E), greater than 99% in mPLMCs (Fig. 5F), and 44.1% in mPPMCs (Fig. 5G). Thus, the turnover of resident cardiac mast cells occurs within the 6-wk period given for bone marrow reconstitution, as cultured cells from hearts of uGFP BMC mice were nearly all GFP positive. In addition, these results confirm that bone marrow ablation by radiation is nearly 100% effective in ablating resident cardiac mast cells, as very few surviving cells were GFP negative.

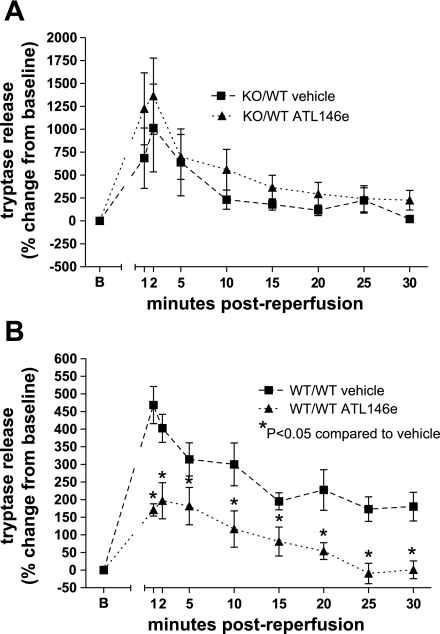

Cardioprotection by ATL146e is mediated through bone marrow-derived cells.

Following transplantation of A2AAR−/− donor bone marrow to radiation-ablated WT recipients [knockout (KO)/WT], the average IS in vehicle-treated groups was 33 ± 3%, and the average IS in ATL146e-treated groups was not changed (38 ± 3%; Fig. 6). In contrast, in hearts from WT/WT BMT mice, the IS reduction in response to ATL146e was reconstituted (40 ± 1% vs. 22 ± 3%, P < 0.05). The ineffectiveness of ATL146e in reducing IS in KO/WT BMT chimeric hearts indicates that the target of ATL146e is A2AARs on bone marrow-derived cells. The reconstitution of ATL146e-mediated protection in WT/WT hearts demonstrates that there is little or no effect of bone marrow transplantation per se on the efficacy of ATL146e to reduce IS.

Fig. 6.

ISs in vehicle- and ATL146e-treated A2AAR+/+ and A2AAR−/− BMC mice. ATL146e reduced ISs in irradiated WT mice where A2AAR+/+ bone marrow had been transplanted (WT/WT vehicle and ATL146e) but not in WT irradiated mice where A2AAR−/− bone marrow was transplanted (KO/WT vehicle and ATL146e). n = 7 vehicle-treated KO/WT mice, 7 ATL146e-treated KO/WT mice, 7 vehicle-treated WT/WT mice, and 7 ATL146e-treated WT/WT mice. *P < 0.05 by one-way ANOVA.

Tryptase release during reperfusion following myocardial ischemia was similar in vehicle- and ATL146e-treated hearts from KO/WT mice (Fig. 7A). In WT/WT hearts, ATL146e treatment reduced tryptase release (Fig. 7B). In concordance with IS data, the lack of effect of ATL146e in KO/WT hearts indicates that selective deletion of the A2AAR on bone marrow cells rendered cardiac mast cells insensitive to A2AAR activation. Conversely, ATL146e- reduced tryptase release in WT/WT BMC mice.

Fig. 7.

Tryptase release in vehicle- and ATL146e-treated A2AAR+/+ and A2AAR−/− BMC mice. A: the percent change in tryptase release was not significantly different in vehicle- and ATL146e-treated hearts from mice where A2AAR−/− bone marrow had been transplanted (KO/WT vehicle and ATL146e). B: ATL146e treatment reduced the percent change in tryptase release at every collection period during reperfusion versus vehicle in mice where A2AAR+/+ bone marrow was transplanted (WT/WT vehicle and ATL146e). *P < 0.05 by two-way ANOVA with the Student-Neuman-Keuls post test.

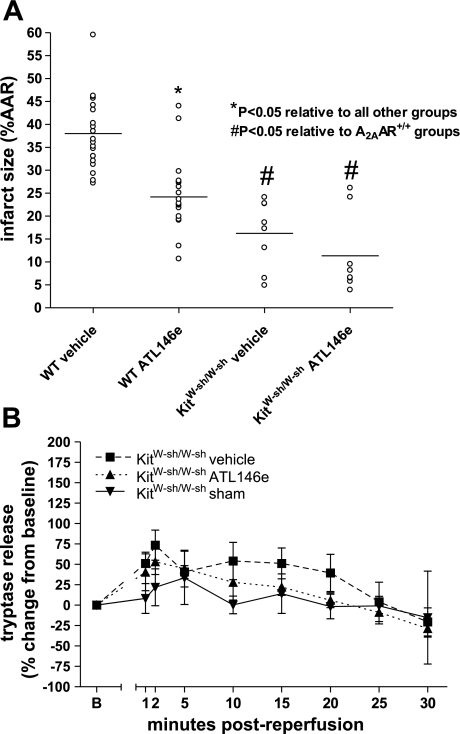

ATL146e does not protect KitW-sh/W-sh mice.

Hearts from KitW-sh/W-sh mice had significantly lower ISs than either vehicle- and ATL146e-treated WT hearts (Fig. 8A). In addition, ISs in KitW-sh/W-sh hearts were significantly lower than those in all other groups tested. ATL146e treatment had no effect to further reduce IS compared with vehicle treatment, as IS in vehicle- and ATL146e-treated groups was 16 ± 3% versus 11 ± 3%, respectively (not significant; Fig. 8A). Mast cell deficiency therefore appears to be protective in the isolated, perfused heart. The lack of additional benefit from ATL146e treatment suggests that mast cells are necessary for the protective effects of A2AAR activation. As expected, little or no tryptase release was detected in hearts from KitW-sh/W-sh mice, and ATL146e treatment had no significant effect (Fig. 8B).

Fig. 8.

IS and tryptase release in hearts from vehicle and ATL146e-treated KitW-sh/W-shmice. A: IS was significantly less in KitW-sh/W-sh hearts of both treatment groups compared with A2AAR+/+ hearts. IS in vehicle- (n = 8) and ATL146e-treated (n = 8) KitW-sh/W-sh hearts showed no difference. B: the percent change from baseline tryptase release in KitW-sh/W-sh hearts was not significantly different from sham or within either treatment group.

DISCUSSION

This study shows that the A2AAR agonists ATL146e and CGS-21680 reduce ex vivo I/R injury in the isolated, asanguineous mouse heart. Upon reperfusion following ischemia, cardiac mast cells degranulated as assessed by measuring tryptase release into the coronary effluent perfusate. Hearts from WT but not A2AAR−/− mice had reduced tryptase release on reperfusion with ATL146e or CGS-21680, indicating that A2AAR activation can reduce mouse heart mast cell degranulation. Hearts from mast cell-deficient mice also had greatly reduced ISs compared with hearts with mast cells. These findings suggest that inhibition of cardiac mast cell degranulation contributes to the cardioprotective effects of A2AAR agonsits in the isolated perfused mouse heart. To our knowledge, this is the first study to show IS reduction in isolated, perfused hearts with an A2AAR agonist given at the onset of reperfusion; Maddock et al. (27) showed that A2AAR agonism attenuated I/R-induced myocardial stunning but did not measure IS. Our data agree with those of Cargnoni et al. (5), although they concluded that the protective target for A2AAR agonism is the cardiac myocyte. CGS-21680 did not significnalty protect hearts from reperfusion injury in some previous studies (38, 44, 51). However, other studies have shown a protective effect for this compound (5), and the role of A2AAR activation in cardioprotection has been controversial. In the present study, CGS-21680 or ATL146e were cardioprotective when added to the coronary perfusate at 100 nmol/l. Findings with A2AAR−/− mice clearly implicate A2AARs as mediators of cardioprotection. We conclude that A2AAR agonists can reduce reperfusion injury in the isolated heart, but possibly only within a certain range of injury.

A2AARs are activated by ATL146e and CGS-21680 but also by adenosine produced in ischemic tissues. Recently, Morrison et al. (30) described the importance of A2AARs in postconditioning, defined as cardioportection caused by short periods of ischemia following a long ischemic episode. Their data showed that treatment with ZM-241385 (an A2AAR-specific antagonist) or A2AAR-specific deletion abrogated myocardial postconditioning and that postconditioned-mediated protection through A2AAR involves ERK1/2 and Akt phosphorylation. Although the role of ERK1/2 and Akt phosphorylation on resident cardiac mast cells is not known, it is possible that A2AAR-mediated postconditioning is facilitated in part by inhibition of mast cell degranulation by adenosine generated by short-duration ischemic postconditioning episodes. Parikh and Singh (37) have provided evidence that cardiac mast cells may play a role in ischemic preconditioining, and these results may extrapolated to postconditioning as well.

Although the role of interstitial mast cells in in vivo MI has been established by several investigators, very few studies have focused on resident cardiac mast cells in isolated hearts. Bhattacharya et al. (4) and Reil et al. (42) showed that isolated hearts from mast cell-deficient mice release less IL-6 and TNF-α into the coronary effluent when these hearts had been subjected to I/R. Our findings show that resident cardiac mast cells contribute to I/R-induced IS expansion in the isolated heart. Consistent with this, Jaggi et al. (15) showed that low-dose carvedilol or ketotifen (both mast cell stabilizers) reduced myocardial injury following I/R, and these compounds had no effect on hearts degranulated with compound 48/80 prior to I/R. Mast cell-mediated myocardial damage occurs despite the relative paucity of mast cells in the C57Bl/6 mouse heart, as reported by Gersch et al. (12). It is possible that the role of resident cardiac mast cells in I/R is amplified in the isolated, perfused heart, as the induced ischemia is global rather than regional. Thus, all mast cells present in the myocardium are subject to I/R stress, whereas regional MI would selectively activate only mast cells in the AAR in the coronary occlusion models that are generally used in vivo.

We recently showed that the protective effect of ATL146e in murine in vivo MI is dependent on its action on CD4-positive T cells, as CD4-positive T cell-specific A2AAR deletion abolishes the protective effect of this drug (49, 50). These in vivo results implicate lymphocytes as the cell type of primary importance in MI. However, T cells are absent in the buffer-perfused heart and therefore do not mediate the damage caused by I/R, nor are they the target of cardioprotection by A2AAR agonsits in this setting. Both mast cells and lymphocytes may be important inflammatory targets in vivo, as it is plausible that degranulation of resident cardiac mast cells is upstream of the infiltration of CD4-positive T cells in the pathology of MI. Frangogiannis et al. (11) have shown that in response to I/R, cardiac mast cells degranulate and release preformed TNF-α, which subsequently induces IL-6 expression in infiltrating mononuclear cells. IL-6 in turn upregulates myocardial ICAM-1 expression, increasing susceptibility to neutrophil-induced adhesion, extravasation, and cytotoxicity (43). In addition, evidence that mast cells can enhance T cell activation (i.e., cytokine production) through TNF-α secretion has been provided by Nakae et al. (34, 35). Thus, resident cardiac mast cells may initiate an inflammatory cascade during in vivo MI and subsequently stimulate the accumulation and activation of CD4-positive T cells in the infarct zone. Additional studies to examine the effect of mast cell deficiency on MI are necessary to further elucidate this possible mechanism.

Independent of any effects on lymphocyte trafficking or activation, our data indicate that mast cell degranulation is injurious to the isolated myocardium following I/R in the absence of infiltrating inflammatory cells. Mast cells are known to release various preformed cytotoxic substances such as serotonin, IL-8, keritinocyte chemoattractant, RANTES, endothelin, bradykinin, urocortin, and substance P, among others (46). In addition, mast cell degranulation releases several preformed proteases such as arylsulfatases, chymase, tryptase, and metalloproteinases, which may be directly damaging to cardiac myocytes and which may be responsible for the observed dependence of increased IS on mast cell degranulation. Recently, Mackins et al. (26) showed evidence for the activation of a local renin-angiotensin axis during I/R in isolated hearts initiated by cardiac mast cell-derived renin. It is plausible that through the activation of angiotensin II and NADPH oxidase, this axis could damage the myocardium directly (in addition to causing rhythm disturbances, as previously reported). Further studies are necessary to determine both the identity and effects of mast cell mediators on the heart. Mast cell mediators may influence in vivo MI by 1) directly damaging the myocardium, thus amplifying the cellular response to injury; 2) increasing the expression of adhesion molecules on vascular endothelial cells, thus increasing the recruitment of inflammatory cells; and 3) stimulating other proximal mast cells to degranulate and further exacerbate the inflammatory cytokine cascade.

Evidence suggesting the release of tryptase from isolated, perfused hearts has been previously reported by Matsui et al. (28), where tryptase-like protease activity correlated well with histamine release during ischemia. These investigators reported that the majority of mast cell degranulation occurs during ischemia with insignificant degranulation occurring during reperfusion. Importantly, this study was carried out by perfusing the heart with an ischemic buffer rather than by using no-flow global ischemia, as was done in the present study. In the present study, we clearly showed that most tryptase release occurs upon reperfusion and that mast cell degranulation contributes to IS expansion.

The role of adenosine in the modulation of mast cell responses has been extensively investigated, but controversy still exists regarding its precise role (24). Our data show that the administration of an A2AAR-selective agonist decreases I/R-induced degranulation in resident cardiac mast cells and that this inhibition is A2AAR dependent. These data are supported by other studies demonstrating the inhibitory capacity of the A2AAR on mast cell degranulation and are consistent with a general mechanism where Gs activation increases intracellular cAMP and suppresses mast cell degranulation (8, 17, 45). This is in contrast to the A3AR (Gi coupled), which promotes mast cell degranulation by increasing the intracellular Ca2+ concentration (17). Interestingly, other studies that have employed A3AR-specific agonists at the onset of reperfusion have not found an exacerbation of IS, although many of the agonists used also activate A2AARs (31). Indeed, as noted by the selectivity of ATL146e and CGS-21680 in the mouse (Table 1), it is plausible that both of these compounds activate A3ARs at the concentrations used in this study. However, our data from both KO and BMC animals show that the effect of these compounds is due to activation of the A2AAR. It is possible that high levels of adenosine and inosine generated during ischemia maximally activate A3ARs on mast cells so that the addition of A3AR agonists has no additional effect.

Table 1.

Receptor binding affinities as determined by radioligand binding for ATL146e and CGS-21680 in the human and mouse A1AR, A2AAR, A3AR, and A2BAR

| Human A1AR |

Human A2AAR |

Human A3AR | Human A2BAR | Mouse A1AR | Mouse A2AAR

|

Mouse A3AR | Mouse A2BAR | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Low-Affinity Binding Site | High-Affinity Binding Site | Low-Affinity Binding Site | High-Affinity Binding Site | |||||||

| ATL146e | 23.4±2.2 | 24.5±6.3 | 0.68±0.1 | 6.9±1 | >1 μmol/l | 65.2±11 | 6.6±0.68 | 1.08±0.5 | 8.87±2.5 | 3,870±337 |

| CGS-21680 | 197±27.3 | 650±67.3 | 17.3±5.1 | 27.6±4.7 | >1 μmol/l | 215±15.3 | 1,450±301 | 0.95±0.4 | 51.1±3 | NA |

Values are means ± SE of receptor binding affinity (Ki) values (in nmol/l unless otherwise noted). AR, adenosine receptor; NA, not available at the time of publication.

Mast cell heterogeneity dictates that the responsiveness of mast cells to promoters and inhibitors of degranulation will vary to a large degree according to the tissue microenvironment in which the mast cell is located. This heterogeneity encompasses AR expression, FCɛRI receptor density, protease content, and secretory granule content (39, 48). The precise identity (i.e., receptor expression and granule content) of resident cardiac mast cells is not known. However, our experiments indicate that they have A2AARs in sufficient density to inhibit I/R-mediated degranulation. The expression profile of ARs on mouse lung mast cells was described by Zhong et al. (52), where the dominant AR was of the A3 subtype with only minor expression of the A2A subtype. In the same study, these investigators showed that A3AR activation alone is sufficient for mast cell activation and degranulation. Although 100 nmol/l ATL146e or CGS-21680 can activate mouse A3ARs (Table 1), we did not observe an increase in tryptase release from A2AAR−/− hearts treated with ATL146e.

Mast cells are relatively long lived after they reach terminal differentiation in peripheral tissues. Our data indicate that after irradiation, both lung and heart mast cells are replaced by bone marrow-derived cells within 6 wk. In contrast, peritoneal mast cells did not turn over this quickly, as evidenced by the fact that 6 wk after GFP bone marrow transplantation, only ∼44% of mast cells were GFP positive. The actual turnover rate of mast cells independent of irradiation is not known; however, some studies have suggested that these cells can reside in tissue for extended periods of time (19). Regardless, our data advocate the use of bone marrow transplantation as an effective method to examine mast cell-dependent tissue effects in both the lung and heart.

Interestingly, ISs in A2AAR−/− hearts were not greater than ISs in WT hearts in the vehicle-treated group. The lack of IS exacerbation suggests that there is no endogenous, nonpharmacological protective value of A2AAR activation in the inhibition of mast cell degranulation during reperfusion. This may indicate that the endogenous adenosine that accumulates during ischemia is rapidly depleted during reperfusion, and A2A adenosinergic tone must be maintained during reperfusion to effectively inhibit mast cell degranulation.

An important limitation of the present study lies in the relative youth and health of the animals used. It is unknown what the role of resident cardiac mast cells is in aged animals with comorbid conditions (e.g., diabetes, hypercholesteremia, hypertension, etc.), a population that would more closely resemble the human population most at risk for MI. Several investigators have noted the role of mast cells in plaque formation and rupture during atherosclerosis (22); however, no data exist regarding the role of preplaque myocardial mast cells in these models. It is possible that other factors in these diseases influence the role of mast cells.

In summary, our data show that the administration of an A2AAR-selective agonist during reperfusion is cardioprotective in the isolated, perfused mouse heart via inhibition of resident cardiac mast cell degranulation. While mast cell mediators can directly damage the isolated heart, an important additional role of these mediators may be as chemotactic stimuli for other damaging leukocytes in vivo.

GRANTS

This work was supported by National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute Grant R01-HL-37942. T. H. Rork is an American Heart Association postdoctoral fellow (0725488U).

DISCLOSURES

J. Linden is a paid consultant to the Adenosine Therapeutics Group.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Jayson Reiger of the Adenosine Therapeutics Group (Charlottesville, VA) for providing ATL146e for use in this study. In addition, the authors thank Dr. John Ryan and Joanne Lannigan for help with the flow cytometry and Renea Frazier for providing binding data for both ATL146e and CGS-21680.

The costs of publication of this article were defrayed in part by the payment of page charges. The article must therefore be hereby marked “advertisement” in accordance with 18 U.S.C. Section 1734 solely to indicate this fact.

REFERENCES

- 1.Ashton KJ, Holmgren K, Peart J, Lankford AR, Paul MG, Grimmond S, Headrick JP. Effects of A1 adenosine receptor overexpression on normoxic and post-ischemic gene expression. Cardiovasc Res 57: 715–726, 2003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Auchampach JA, Jin X, Wan TC, Caughey GH, Linden J. Canine mast cell adenosine receptors: cloning and expression of the A3 receptor and evidence that degranulation is mediated by the A2B receptor. Mol Pharmacol 52: 846–860, 1997. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Beil WJ, Schulz M, Wefelmeyer U. Mast cell granule composition and tissue location–a close correlation. Histol Histopathol 15: 937–946, 2000. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bhattacharya K, Farwell K, Huang M, Kempuraj D, Donelan J, Papaliodis D, Vasiadi M, Theoharides TC. Mast cell deficient W/Wv mice have lower serum IL-6 and less cardiac tissue necrosis than their normal littermates following myocardial ischemia-reperfusion. Int J Immunopathol Pharmacol 20: 69–74, 2007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Cargnoni A, Ceconi C, Boraso A, Bernocchi P, Monopoli A, Curello S, Ferrari R. Role of A2A receptor in the modulation of myocardial reperfusion damage. J Cardiovasc Pharmacol 33: 883–893, 1999. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Chancey AL, Brower GL, Janicki JS. Cardiac mast cell-mediated activation of gelatinase and alteration of ventricular diastolic function. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol 282: H2152–H2158, 2002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Day YJ, Li Y, Rieger JM, Ramos SI, Okusa MD, Linden J. A2A adenosine receptors on bone marrow-derived cells protect liver from ischemia-reperfusion injury. J Immunol 174: 5040–5046, 2005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Duffy SM, Cruse G, Brightling CE, Bradding P. Adenosine closes the K+ channel KCa3.1 in human lung mast cells and inhibits their migration via the adenosine A2A receptor. Eur J Immunol 37: 1653–1662, 2007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Feoktistov I, Polosa R, Holgate ST, Biaggioni I. Adenosine A2B receptors: a novel therapeutic target in asthma? Trends Pharmacol Sci 19: 148–153, 1998. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Forman MF, Brower GL, Janicki JS. Spontaneous histamine secretion during isolation of rat cardiac mast cells. Inflamm Res 53: 453–457, 2004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Frangogiannis NG, Lindsey ML, Michael LH, Youker KA, Bressler RB, Mendoza LH, Spengler RN, Smith CW, Entman ML. Resident cardiac mast cells degranulate and release preformed TNF-alpha, initiating the cytokine cascade in experimental canine myocardial ischemia/reperfusion. Circulation 98: 699–710, 1998. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Gersch C, Dewald O, Zoerlein M, Michael LH, Entman ML, Frangogiannis NG. Mast cells and macrophages in normal C57/BL/6 mice. Histochem Cell Biol 118: 41–49, 2002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Gilles S, Zahler S, Welsch U, Sommerhoff CP, Becker BF. Release of TNF-alpha during myocardial reperfusion depends on oxidative stress and is prevented by mast cell stabilizers. Cardiovasc Res 60: 608–616, 2003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Glover DK, Ruiz M, Takehana K, Petruzella FD, Rieger JM, Macdonald TL, Watson DD, Linden J, Beller GA. Cardioprotection by adenosine A2A agonists in a canine model of myocardial stunning produced by multiple episodes of transient ischemia. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol 292: H3164–H3171, 2007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Jaggi AS, Singh M, Sharma A, Singh S, Singh N. Cardioprotective effects of mast cell modulators in ischemia-reperfusion-induced injury in rats. Methods Find Exp Clin Pharmacol 29: 593–600, 2007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Janicki JS, Brower GL, Gardner JD, Forman MF, Stewart JA Jr, Murray DB, Chancey AL. Cardiac mast cell regulation of matrix metalloproteinase-related ventricular remodeling in chronic pressure or volume overload. Cardiovasc Res 69: 657–665, 2006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Jin X, Shepherd RK, Duling BR, Linden J. Inosine binds to A3 adenosine receptors and stimulates mast cell degranulation. J Clin Invest 100: 2849–2857, 1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kano S, Tyler E, Salazar-Rodriguez M, Estephan R, Mackins CJ, Veerappan A, Reid AC, Silver RB, Levi R. Immediate hypersensitivity elicits renin release from cardiac mast cells. Int Arch Allergy Immunol 146: 71–75, 2007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kiernan JA Production and life span of cutaneous mast cells in young rats. J Anat 128: 225–238, 1979. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Lankford AR, Yang JN, Rose'Meyer R, French BA, Matherne GP, Fredholm BB, Yang Z. Effect of modulating cardiac A1 adenosine receptor expression on protection with ischemic preconditioning. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol 290: H1469–H1473, 2006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Lavens SE, Proud D, Warner JA. A sensitive colorimetric assay for the release of tryptase from human lung mast cells in vitro. J Immunol Methods 166: 93–102, 1993. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Leslie M Mast cells show their might. Science 317: 614–616, 2007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Linden J, Auchampach JA, Jin X, Figler RA. The structure and function of A1 and A2B adenosine receptors. Life Sci 62: 1519–1524, 1998. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Livingston M, Heaney LG, Ennis M. Adenosine, inflammation and asthma–a review. Inflamm Res 53: 171–178, 2004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Lukacs NW, Kunkel SL, Strieter RM, Evanoff HL, Kunkel RG, Key ML, Taub DD. The role of stem cell factor (c-kit ligand) and inflammatory cytokines in pulmonary mast cell activation. Blood 87: 2262–2268, 1996. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Mackins CJ, Kano S, Seyedi N, Schafer U, Reid AC, Machida T, Silver RB, Levi R. Cardiac mast cell-derived renin promotes local angiotensin formation, norepinephrine release, and arrhythmias in ischemia/reperfusion. J Clin Invest 116: 1063–1070, 2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Maddock HL, Broadley KJ, Bril A, Khandoudi N. Role of endothelium in ischaemia-induced myocardial dysfunction of isolated working hearts: cardioprotection by activation of adenosine A2A receptors. J Auton Pharmacol 21: 263–271, 2001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Matsui N, Okikawa T, Imajo N, Yasui Y, Fukuishi N, Akagi M. Enzymatic measurement of tryptase-like protease release from isolated perfused guinea pig heart during ischemia-reperfusion. Biol Pharm Bull 28: 2149–2151, 2005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Metz M, Grimbaldeston MA, Nakae S, Piliponsky AM, Tsai M, Galli SJ. Mast cells in the promotion and limitation of chronic inflammation. Immunol Rev 217: 304–328, 2007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Morrison RR, Tan XL, Ledent C, Mustafa SJ, Hofmann PA. Targeted deletion of A2A adenosine receptors attenuates the protective effects of myocardial postconditioning. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol 293: H2523–H2529, 2007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Murphree LJ, Marshall MA, Rieger JM, Macdonald TL, Linden J. Human A2A adenosine receptors: high-affinity agonist binding to receptor-G protein complexes containing Gβ4. Mol Pharmacol 61: 455–462, 2002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Murray DB, Gardner JD, Brower GL, Janicki JS. Endothelin-1 mediates cardiac mast cell degranulation, matrix metalloproteinase activation, and myocardial remodeling in rats. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol 287: H2295–H2299, 2004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Murray DB, Gardner JD, Brower GL, Janicki JS. Effects of nonselective endothelin-1 receptor antagonism on cardiac mast cell-mediated ventricular remodeling in rats. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol 294: H1251–H1257, 2008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Nakae S, Suto H, Iikura M, Kakurai M, Sedgwick JD, Tsai M, Galli SJ. Mast cells enhance T cell activation: importance of mast cell costimulatory molecules and secreted TNF. J Immunol 176: 2238–2248, 2006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Nakae S, Suto H, Kakurai M, Sedgwick JD, Tsai M, Galli SJ. Mast cells enhance T cell activation: Importance of mast cell-derived TNF. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 102: 6467–6472, 2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Nistri S, Cinci L, Perna AM, Masini E, Mastroianni R, Bani D. Relaxin induces mast cell inhibition and reduces ventricular arrhythmias in a swine model of acute myocardial infarction. Pharmacol Res 57: 43–48, 2007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Parikh V, Singh M. Possible role of cardiac mast cell degranulation and preservation of nitric oxide release in isolated rat heart subjected to ischaemic preconditioning. Mol Cell Biochem 199: 1–6, 1999. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Peart J, Flood A, Linden J, Matherne GP, Headrick JP. Adenosine-mediated cardioprotection in ischemic-reperfused mouse heart. J Cardiovasc Pharmacol 39: 117–129, 2002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Puri N, Roche PA. Mast cells possess distinct secretory granule subsets whose exocytosis is regulated by different SNARE isoforms. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 105: 2580–2585, 2008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Ramkumar V, Stiles GL, Beaven MA, Ali H. The A3 adenosine receptor is the unique adenosine receptor which facilitates release of allergic mediators in mast cells. J Biol Chem 268: 16887–16890, 1993. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Reid AC, Silver RB, Levi R. Renin: at the heart of the mast cell. Immunol Rev 217: 123–140, 2007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Reil JC, Gilles S, Zahler S, Brandl A, Drexler H, Hultner L, Matrisian LM, Welsch U, Becker BF. Insights from knock-out models concerning postischemic release of TNFalpha from isolated mouse hearts. J Mol Cell Cardiol 42: 133–141, 2007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Sanceau J, Kaisho T, Hirano T, Wietzerbin J. Triggering of the human interleukin-6 gene by interferon-gamma and tumor necrosis factor-alpha in monocytic cells involves cooperation between interferon regulatory factor-1, NF kappa B, and Sp1 transcription factors. J Biol Chem 270: 27920–27931, 1995. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Solenkova NV, Solodushko V, Cohen MV, Downey JM. Endogenous adenosine protects preconditioned heart during early minutes of reperfusion by activating Akt. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol 290: H441–H449, 2006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Suzuki H, Takei M, Nakahata T, Fukamachi H. Inhibitory effect of adenosine on degranulation of human cultured mast cells upon cross-linking of Fc epsilon RI. Biochem Biophys Res Commun 242: 697–702, 1998. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Theoharides TC, Kempuraj D, Tagen M, Conti P, Kalogeromitros D. Differential release of mast cell mediators and the pathogenesis of inflammation. Immunol Rev 217: 65–78, 2007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Tilley SL, Tsai M, Williams CM, Wang ZS, Erikson CJ, Galli SJ, Koller BH. Identification of A3 receptor- and mast cell-dependent and -independent components of adenosine-mediated airway responsiveness in mice. J Immunol 171: 331–337, 2003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Welle M Development, significance, and heterogeneity of mast cells with particular regard to the mast cell-specific proteases chymase and tryptase. J Leukoc Biol 61: 233–245, 1997. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Yang Z, Day YJ, Toufektsian MC, Ramos SI, Marshall M, Wang XQ, French BA, Linden J. Infarct-sparing effect of A2A-adenosine receptor activation is due primarily to its action on lymphocytes. Circulation 111: 2190–2197, 2005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Yang Z, Day YJ, Toufektsian MC, Xu Y, Ramos SI, Marshall MA, French BA, Linden J. Myocardial infarct-sparing effect of adenosine A2A receptor activation is due to its action on CD4+ T lymphocytes. Circulation 114: 2056–2064, 2006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Zatta AJ, Matherne GP, Headrick JP. Adenosine receptor-mediated coronary vascular protection in post-ischemic mouse heart. Life Sci 78: 2426–2437, 2006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Zhong H, Shlykov SG, Molina JG, Sanborn BM, Jacobson MA, Tilley SL, Blackburn MR. Activation of murine lung mast cells by the adenosine A3 receptor. J Immunol 171: 338–345, 2003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]