Abstract

The role of TLRs and MyD88 in the maintenance of gut integrity in response to dextran sodium sulfate (DSS)-induced colitis was demonstrated recently and led to the conclusion that our innate immune response to luminal commensal flora provides necessary signals that facilitate epithelial repair and permit a return to homeostasis after colonic injury. In this report, we demonstrate that a deficit in a single neutrophil chemokine, CXCL1/KC, also results in a greatly exaggerated response to DSS. Mice with a targeted mutation in the gene that encodes this chemokine responded to 2.5% DSS in their drinking water with significant weight loss, bloody stools, and a complete loss of gut integrity in the proximal and distal colon, accompanied by a predominantly mononuclear infiltrate, with few detectable neutrophils. In contrast, CXCL1/KC−/− and wild-type C57BL/6J mice provided water only showed no signs of inflammation and, at this concentration of DSS, wild-type mice administered DSS showed only minimal histopathology, but significantly more infiltrating neutrophils. This finding implies that neutrophil infiltration induced by CXCL1/KC is an essential component of the intestinal response to inflammatory stimuli as well as the ability of the intestine to restore mucosal barrier integrity.

INTRODUCTION

The murine chemokine, keratinocyte chemoattractant CXCL1 (also called KC or N51), is a potent neutrophil chemoattractant. It was identified originally as being stimulated to very high levels in keratinocytes, monocytes, and macrophages in response to a variety of endogenous stimuli, including Platelet-derived Growth Factor, Colony Stimulating Factor-1, TNF-α and microbial stimuli. Synthesis of CXCL1/KC is observed also in vascular endothelial cells where it is induced by thrombin. Mice do not have a structural homolog for the human neutrophil chemoattractant, IL-8. There is some debate in the literature about whether murine KC (mouse CXCL1) is a structural homolog of human Gro-α (CXCL1) or Gro-β (CXCL2), with murine MIP-2 (CXCL2) being the structural homolog of the other.reviewed in 1, 2

Relatively little is known about the regulation of CXCL1/KC expression or its role in inflammation. However, the prototype Toll-like receptor (TLR) 4 agonist, Gram negative lipopolysaccharide (LPS), is a very potent inducer of CXCL1/KC in vitro and in vivo.3–5 For example, CXCL1/KC steady-state mRNA is increased ~60-fold over baseline levels by 1 hr in murine macrophage cultures and remains elevated for 48 hr, and similarly, hepatic CXCL1/KC gene expression was upregulated within an hour of LPS administration to mice. In contrast to many LPS-inducible proinflammatory genes, induction of CXCL1/KC is blunted by the Th1 cytokine, IFN-γ.3 In macrophages rendered “endotoxin tolerant” by prior exposure to LPS, CXCL1/KC is poorly inducible.4 In a mouse model of polymicrobial sepsis induced by cecal ligation and sepsis, CXCL1/KC mRNA is strongly and rapidly induced in the livers and lungs and is associated with increased neutrophil infiltration into these organs.6

Despite the fact that CXCL1/KC has been observed to be strongly upregulated in a variety of in vitro and in vivo systems, its role in the induction of a protective vs. pathologic response remains controversial. For example, overexpression of CXCL1/KC in the lungs of transgenic mice resulted in significant neutrophil infiltration in the absence of tissue injury; however, these infiltrating neutrophils still contained their cytoplasmic granules, indicating that they had not undergone degranulation.7,8 Transient overexpression of CXCL1/KC in the lungs of mice resulted in a significant level of survival and reduction of fungal burden in response to challenge with invasive aspergillosis9,10 as well as enhanced resistance to Klebsiella pneumoniae infection.11 On the other hand, several studies provided a strong association for a role of CXCL1/KC in disease. Boisevert et al.12 mated CXCL1/KC−/− mice with atherosclerosis-prone LDLR−/− mice and observed a significant protective effect against development of atherosclerosis when compared to CXCL1/KC-competent control mice. In a model of Hemolytic Uremic Syndrome (HUS) induced by co-administration of LPS and Shigatoxin produced by E. coli, Obrig and colleagues13 demonstrated that the pathology, including neutrophil infiltration into the kidneys that is characteristic of HUS, was inhibited by co-administration of antibodies against CXCL1/KC and CXCL2/MIP-2.14

In this study, we determined the role of CXCL1/KC in the intestinal response to inflammation using mice with a targeted mutation in CXCL1/KC. The findings presented herein demonstrate that mice deficient in CXCL1/KC exhibit a much more profound colitis in response to DSS, supporting a protective role of CXCL1/KC-mediated recruitment of neutrophils in this model.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Mice

Mice with a targeted mutation in CXCL1/KC were derived as described by Boisvert et al.12 and backcrossed 14 generations to C57BL/6J mice (Jackson Laboratories, Bar Harbor, ME). C57BL/6J mice were used as wild-type (WT) controls. CXCL1/KC−/− mice were maintained in a specific pathogen-free (SPF) barrier facility at UMB and were fed sterile food and hyperchlorinated water and autoclaved bedding. All animal experiments were carried out within our institution’s AAALAC-accredited program following Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee (IACUC) approval.

DSS model of colitis

DSS-induced colitis was induced exactly as described by Fukata et al.15 Briefly, DSS with a molecular weight of 36,000 – 50,000 (MP Biomedicals, Lot No. 8825H) was dissolved in water at 2.5% (w/v) and the bottles changed daily. It is important to note that DSS lots differ greatly in their ability to induce experimental colitis and the dosage used may have to be determined empirically. While administration of 5% DSS led to occasional deaths in C57BL/6J WT control mice, administration of 2.5% DSS to WT mice resulted in little or no signs of disease. A final concentration of 2.5% DSS was chosen because it clearly discriminated between the WT and CXCL1/KC−/− mice (presented in the Results section).

To quantify the extent of mucosal damage, the entire length of the small intestine and colon was removed en bloc. Sections of small intestine were taken at 5 (upper jejunum; I-1), 15 (jejunum; I-2), and 25 (ileum; I-3) cm from the pylorus. The cecum was removed and sections were taken from the mid-proximal (PC) and mid-distal (DC) colon. Tissue was fixed in 4% paraformaldehyde, paraffin embedded, sectioned (5 μ), and stained with Wright-Giemsa or hematoxylin and eosin (H&E). Assessment of microscopic inflammation was performed by two investigators who were unaware of the treatment groups. The histological score was a combined score of acute inflammatory cell infiltrate (neutrophils, 0–4), chronic inflammatory cell infiltrate (mononuclear cells, 0–3), and crypt damage (0–4) (Table1). Specifically, the crypt damage was scored as follows: score of 0 was given to an intact crypt, 1 = loss of the basal one-third of crypt, 2 = loss of basal two-thirds of crypt, 3 = entire loss of crypt, and 4 = loss of crypt and surface epithelium.15–17 The number of neutrophils was counted in Giemsa-stained sections of I-3, PC, and DC for each mouse in 10 consecutive fields (1000x) that had well-oriented architecture.

Microsnapwell assay of transepithelial electrical resistance (TEER)

To determine if mice deficient in CXCL1/KC possess an inherent defect in intestinal permeability, intestinal transepithelial electrical resistance (TEER) and changes in TEER in mouse small intestine were measured using the microsnapwell system.18 Briefly, sections of small intestine from WT or mice deficient in CXCL1/KC were stripped of smooth muscle and mounted in microsnapwells and TEER was measured every 30 min for 90 min.

RESULTS

CXCL1/KC−/− mice respond to DSS with significant weight loss

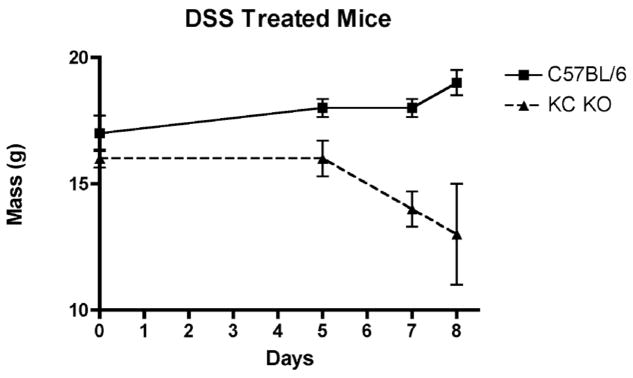

WT and CXCL1/KC−/− mice were provided water or 2.5% DSS in water ad libitum and weighed over an 8 day period. Higher concentrations of DSS caused significant mortality in the CXCL1/KC−/− mice. Figure 1 shows that over this time period, the WT mice did not lose weight and showed minimal signs of illness, while the CXCL1/KC−/− mice lost 18% of their starting weight (and were 31% below the weight of DSS-treated WT mice at Day 8), exhibited bloody stools within 5 days of DSS administration, and many appeared to be moribund by Day 7–8. It is important to note that both the WT and CXCL1/KC−/− mice were housed in an extremely clean barrier facility that is free of adventitious pathogens. This, coupled with the observation that different lots of DSS exhibit variability in their capacity to induce inflammation, as well as strain differences in susceptibility to DSS, may account for the fact that the WT mice used in our study failed to show any overt signs of inflammation or injury, in contrast to other similar studies carried out under apparently similar conditions.15,19

Figure 1.

Weight loss of WT (C57BL/6) and CXCL1/KC−/− mice in response to DSS treatment. On day 0, mice were placed on DSS-containing drinking water and mouse weights were monitored. Results represent the mean ± SD of 8 mice per treatment group.

Microscopic damage in DSS-treated WT and CXCL1/KC−/− mice

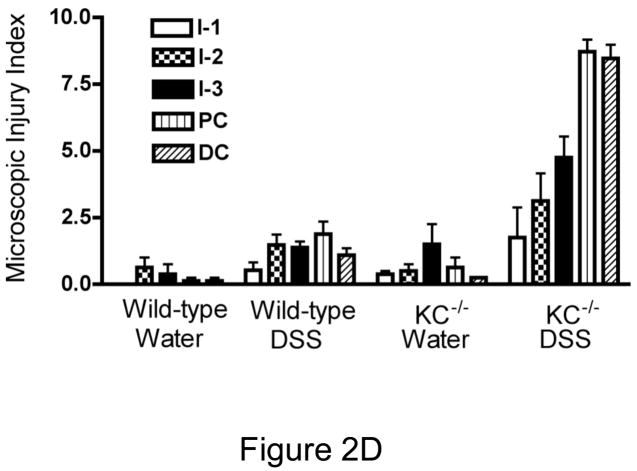

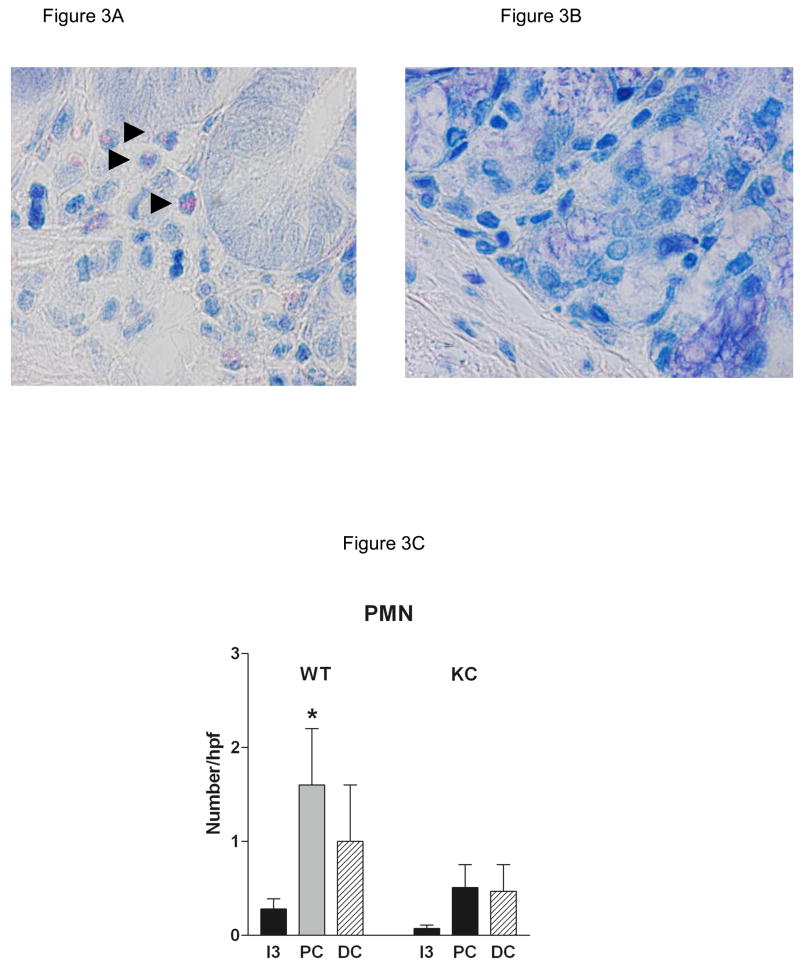

Representative photomicrographs from control (water only) and DSS-treated WT (C57BL/6) and CXCL1/KC−/− mice are shown in Figures 2A and B, respectively. The small intestine morphology was essentially unaltered by DSS treatment in WT mice at this concentration of DSS. Similarly, DSS did not cause significant injury to the colonic mucosa in WT mice, but did induce a marked smooth muscle hypertrophy in the muscularis externa of this region (Figure 2A, PC and DC). There was no difference in the microscopic appearance of the small intestine or colon in vehicle-treated WT and CXCL1/KC−/− mice, although there was some suggestion of hyperplasia of mucus in the colon, but not in the intestine of the CXCL1/KC−/− mice. In contrast to WT mice, however, DSS treatment induced significant changes in the GI tract of CXCL1/KC−/− mice (Figure 2B). Damage was not evident in the duodenum or jejunum (I-1, I-2), but the ileum (I-3) showed marked sloughing of surface epithelial cells extending along the length of the villi. DSS induced significant damage in the colonic mucosa of CXCL1/KC−/− mice. The proximal colon (PC) featured epithelial sloughing, inflammatory infiltrate in the mucosa and submucosa as well as in the smooth muscle. The distal colon (DC) in DSS-treated CXCL1/KC−/− mice was characterized by marked mucosal hypertrophy and mucus hyperplasia with alternating areas of moderate with severe damage including loss of epithelial, goblet cells, and crypts. There was also marked inflammatory infiltrate containing primarily of mononuclear inflammatory cells (Figure 2C) as well as lymphoid aggregates. The mean microscopic injury scores that were read in a blinded fashion show that the response to DSS was increased slightly in WT mice, but was exaggerated greatly in the CXCL1/KC−/− mice with significant injury in the distal small intestine and colon (Figure 2D). Examination of sections under high power revealed modest neutrophil infiltration in sections derived from DSS-treated WT mice, despite the fact that they exhibited little outward signs of illness (Figure 3A and C). Infiltration was primarily around crypts and was clustered, rather than uniform in distribution (Figure 3A). In contrast, neutrophils were not detected in most sections derived from DSS-treated CXCL1/KC−/− mice despite significant mucosal injury and marked mononuclear inflammatory infiltrate (Figure 3B and C).

Figure 2.

(A) WT (C57BL/6) or (B) CXCL1/KC−/− mice were given water (control) or DSS in water ad libitum for 8 days. The entire intestine and cecum were removed en bloc and sections obtained from the upper jejunum (I-1), jejunum (I-2), ileum (I-3) mid-proximal colon (PC) and mid-distal colon (DC), fixed, and stained with Wright-Giemsa stain. Results represent photomicrographs (100X) of representative sections from individual mice (N = 8 per treatment group). Additional control mice (fed water without DSS for the entire 8 days; N = 2 per strain) were also included and showed no signs of microscopic injury (data not shown). The results are representative of two independent experiments. (C.) Higher magnifications of distal colon of a DSS-treated CXCL1/KC−/− mouse. Left photomicrograph (200X, H&E): destruction of most of the epithelium in the crypts and glands (arrow), with inflammatory cells extending into the submucosa (arrowhead). Right photomicrograph (400X, H&E)): illustrates distal colonic epithelium and infiltration of chronic inflammatory cells (arrowhead). There is also an acute inflammatory infiltrate in the lumen (arrow). Bottom photomicrograph (1000X Giemsa) shows typical inflammatory infiltrate in mucosa, featuring primarily lymphocytes (arrow) and macrophages (arrowhead). (D.) Injury score for each section examined by two independent readers as described in Materials and Methods. . Results represent the mean ± SEM for each treatment group. DSS-treated KC mice had significantly greater injury in I3 (p<0.01), PC (p<0.001) and DC (p<0.001) when compared to DSS-treated WT mice

Figure 3.

(A) WT (C57BL/6) or (B) CXCL1/KC−/− mice were given water (control) or DSS in water ad libitum for 8 days. The mid-distal colon (DC) was fixed, and stained with Wright-Giemsa stain. Results represent photomicrographs (1000X) of representative sections from individual mice (N = 8 per treatment group). There was modest PMN infiltrate in WT with little evidence of mucosal injury (see Figure 2 A, DC, DSS). In contrast, there were few neutrophils evident in CXCL1/KC−/− mice (quantified in C; mean ± SEM; *p < 0.05), although the mice exhibited marked mucosal damage (see Figure 2B, DC, DSS). The greater cellularity and mucus hyperplasia evident in the distal colon in Figure 2 is also present in these sections.

CXCL1/KC−/− mice do not exhibit basal intestinal leak

It has been reported previously that mice with a targeted mutation in MyD88, a key adapter molecule for TLR/IL-1R-mediated signaling, exhibited increased susceptibility to DSS-induced damage, similar to the response of CXCL1/KC−/− mice shown herein.15,19 Subsequently, we showed that MyD88−/− mice, but not TLR4−/− mice, exhibited “leaky” intestines in the absence of exogenous stimulation as measured by decreased transepithelial electrical resistance (TEER) when compared to WT intestinal segments.20 Therefore, we also compared CXCL1/KC−/− intestinal segments to those of WT mice for basal TEER levels. In contrast to MyD88−/− mice, CXCL1/KC−/− intestines were not “leaky” basally (TEER measured at 90 min, CXCL1/KC−/− = 49.0 ± 7.6 Ωcm2 (N = 3) vs. WT = 40.3 ± 4.1 Ωcm2 (N = 5), respectively; p > 0.05, Student’s t test). Thus, the increased sensitivity of CXCL1/KC−/− to DSS-induced intestinal damage cannot be attributable to basal “leakiness.”

DISCUSSION

This report demonstrates that the failure to express a single chemokine, CXCL1/KC, results in a profoundly impaired intestinal response to exposure to DSS. These data point to CXCL1/KC as an important mediator of gut integrity in the DSS model of colitis. Previous reports demonstrated that TLR4−/−, TLR2−/−, and MyD88−/− mice exhibit a similar phenotype in response to DSS15,19 and, together, these findings support the concept that TLR activation and neutrophil recruitment have beneficial effects to the maintenance and restoration of mucosal homeostasis during inflammation.

There are a number of experimental models of inflammatory bowel disease (IBD) including both chemically induced (e.g., DSS, trinitrobenzene sulfonic acid) and mice with targeted gene deletions in specific cytokines. For example, mice with a targeted mutation in the gene that encodes IL-10, an anti-inflammatory cytokine, spontaneously develop colitis and have been used as a model for IBD.21,22 However, when such mice are reared under germ-free conditions, colitis fails to develop21, indicating the importance of gut flora to the induction of the colitis. TLR4 expression is normally low in intestinal epithelial cells, but can be induced by proinflammatory cytokines such as TNF-α and IFN-γ23, both of which are increased in the absence of IL-10.24 Based on these and other observations, two groups independently postulated that TLR4 or TLR2 signaling through a MyD88-dependent signaling pathway, induced by the innate immune response to commensal bacteria, protects against the induction of chemically-induced colitis.15,19 Oral administration of DSS to mice is commonly used as a model of colon inflammation in which the epithelial barrier is disrupted, leaving the lamina propria exposed to gut bacteria. Mice lacking TLR2, TLR4, or the adapter molecule, MyD88, were significantly more susceptible to DSS-induced colitis and exhibited a greatly reduced capacity for intestinal epithelial proliferation, indicating that TLR signaling in response to gut flora is important for maintenance of normal epithelial barrier function.15,19 Consistent with these findings, TLR4−/− and MyD88−/− mice exhibited bloody stools and rectal bleeding prior to DSS-treated WT mice, as well as bacterial translocation to the mesenteric lymph nodes that was not observed in WT mice.15 The observation that mice deficient in MyD88 have a constitutively impaired barrier function, as evidenced by basally decreased TEER12, may contribute to the increased susceptibility to DSS in these mice. Collectively, these data suggest that TLR signaling in response to the presence of commensal bacteria after epithelial injury is required for reestablishment of gut integrity. It is interesting to note that mice with a targeted mutation in the Vitamin D3 receptor are also highly susceptible to DSS-induced colitis as well as to i.v. administration of LPS, and like their WT controls, proinflammatory cytokines, including CXCL1/KC, could be detected in colonic homogenates in mice treated with DSS.25 However, whether vitamin D regulates TLR signaling pathways to maintain gut integrity is unknown.

In humans, CXCL8 (IL-8) has two receptors, CXCR1 and CXCR2. In the mouse, however, CXCR2 appears to serve as the receptor for CXCL1/KC; CXCL1/KC was shown to be an ineffective ligand for mCXCR1 as measured by [35S]GTPγS exchange.26 In a very recent report, however, Buanne et al.27 showed that mice with a targeted mutation in CXCR2 exhibited ameliorated inflammation in a model of chronic experimental colitis induced by two consecutive cycles of 4% DSS (separated by 14 days of water only) as evidenced by lower clinical, histopathologic and pathologic scores in the CXCR2−/− mice from Days 20 to 27 of treatment than observed in WT mice. It should be noted that at the end of the first cycle of DSS treatment (Day 6), the clinical, histological, and pathological scores of WT and CXCR2−/− mice receiving DSS were not significantly different, in contrast to the findings presented herein. This suggests that during the initial exposure to DSS, CXCR2 is less important in the “acute” inflammatory response and, perhaps, CXCR1 substitutes as a low affinity receptor. Although one might postulate that additional receptor for CXCL1/KC exists, there is currently no evidence for this possibility. It is also possible that the discrepancies observed in our study and that of Buanne et al. are attributable to the dose of DSS and strain differences in the mice used. The concentration of DSS used in the study by Buanne et al. was considerably higher than that used herein. At 2.5% DSS, the CXCL1/KC−/− were moribund at Day 8, while control mice showed essentially no overt signs of illness (including no weight loss; Figure 1) and only minimal histopathology (Figure 2D). Importantly, in our study (and those in references 15 and 19), the mice with targeted mutations were backcrossed onto a C57BL/6 background, while in the study by Buanne et al., the mice were on a BALB/c background. Significant differences in inflammatory responses between these two inbred strains have been reported previously (e.g., in response to Leishmania infection28) and might contribute to differences observed in the two studies. Lastly, differences in the exposure of mice to environmental pathogens may influence sensitivity to DSS: Jackson Laboratories houses both C57BL/6J and BALB/cJ mice with IL-10-deficient mice for 7 days “to facilitate the transfer of enteric bacteria necessary to induce colitis” by DSS.29

Neutrophil infiltration into mucosal epithelia is a hallmark of IBD and accumulation within epithelial crypts and in the intestinal lumen is linked to clinical disease activity and epithelial injury.reviewed in 30 In colonic mucosa of IBD patients, increased macrophage-mediated generation of IL-8 and CXCL1/KC (Gro-α) was correlated positively with disease activity.31 Despite the established contribution of neutrophils to active mucosal inflammation, as well as the correlation of neutrophil infiltration with severe inflammation in the chronic relapsing DSS colitis model27, there is a growing recognition that recruitment of neutrophils during inflammation also exerts beneficial effects. Hans et al.32 found that neutrophil depletion of mice led to aggravation of DSS-induced colitis. Fukata et al.15 reported that by 5 days after DSS, TLR4−/− and MyD88−/− mice exhibited essentially no neutrophil infiltration into the lamina propria or submucosa in contrast to WT mice, and this was correlated with decreased production of MIP-2 by lamina propria macrophages. Our data extend these observations, but suggest that a deficit of CXCL1/KC, rather than MIP-2, another CXCR2 ligand, is likely primarily responsible for the lack of neutrophil infiltration observed by Fukata et al. This observation is also consistent with the recent finding of Qualls et al.33 that depletion of macrophages by intrarectal administration of chlodronate-encapsulated liposomes, but not control liposomes, to WT mice resulted in marked colitis in response to subsequent administration of DSS in the drinking water. The present study also demonstrates that the augmented inflammation in response to DSS in the CXCL1/KC-deficient mice is not linked to a constitutive defect in barrier function as mucosal resistance was similar to that in WT mice. Together, these data imply that the innate immune response to commensal flora through TLR2 and TLR4, MyD88-mediated signaling, results in production of CXCL1/KC that recruits neutrophils in response to DSS. Thus, the data of Qualls et al., coupled with our own, clearly suggest that recruitment of neutrophils by macrophage-derived or macrophage-mediated production of CXCL1/KC is protective in this model.

In conclusion, these data are the first to demonstrate a protective role for endogenous CXCL1/KC in disease, extending earlier findings that lung-specific transgenic expression of CXCL1/KC in mice enhances resistance to fungal and Klebsiella pneumoniae infections.9–11 Future studies to characterize the role of this potent neutrophil chemokine in protection or enhancement of other diseases will potentially lead to therapeutic approaches that target this important inflammatory molecule in diseases associated with colitis.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported in part by NIH grants AI-49316 (TSD), DK-072201 (SAL), AI-18797 (SNV), AI-052266 and a Career Development Award from the Crohn’s & Colitis Foundation of America (MF), and The Program of Comparative Medicine, UMB (LDT). The authors wish to thank Ms. Sandra Jabre for excellent technical assistance in the maintenance of the CXCL1/KC−/− breeding colony.

References

- 1.Horst Ibelgaufts’ COPE: Cytokines & Cells Online Pathfinder Encyclopaedia. Version 19.4. 2007 April; http://www.copewithcytokines.de/cope.cgi?key=KC.

- 2.Kobayashi Y. Neutrophil infiltration and chemokines. Crit Revs Immunol. 2006;26:307–315. doi: 10.1615/critrevimmunol.v26.i4.20. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kopydlowski KM, Salkowski CA, Cody MJ, van Rooijen N, Major J, Hamilton TA, Vogel SN. Regulation of macrophage chemokine expression by lipopolysaccharide in vitro and in vivo. J Immunol. 1999;163:1537–1544. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Medvedev AE, Kopydlowski KM, Vogel SN. Inhibition of Lipopolysaccharide-induced signal transduction in endotoxin-tolerized mouse macrophages: dysregulation of cytokine, chemokine, and toll-like receptor 2 and 4 gene expression. J Immunol. 2000;164:5564–5574. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.164.11.5564. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Rovai LE, Herschman HR, Smith JB. The murine neutrophil-chemoattractant chemokines LIX, KC, and MIP-2 have distinct induction kinetics, tissue distributions, and tissue-specific sensitivities to glucocorticoid regulation in endotoxemia. J Leuk Biol. 1998;64:494–502. doi: 10.1002/jlb.64.4.494. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Salkowski CA, Detore G, Franks A, Falk MC, Vogel SN. Pulmonary and hepatic gene expression following cecal ligation and puncture: monophosphoryl lipid A prophylaxis attenuates sepsis-induced cytokine and chemokine expression and neutrophil infiltration. Infect Immun. 1998;66:3569–3578. doi: 10.1128/iai.66.8.3569-3578.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Lira SA, Fuentes ME, Strieter RM, Durham SK. Transgenic method to study chemokine function in lung and central nervous system. Meth Enzymology. 1997;287:304–318. doi: 10.1016/s0076-6879(97)87022-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Lira SA, Zalamea P, Heinrich JN, Fuentes ME, Carrasco D, Lewin AC, Barton DS, Durham S, Bravo R. Expression of the chemokine N51/KC in the thymus and epidermis of transfenic mice results in marked infiltration of a single class of inflammatory cells. J Exp Med. 180:2039–2048. doi: 10.1084/jem.180.6.2039. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Mehard B, Strieter RM, Moore TA, Tsai WC, Lira SA, Standiford TJ. CXC chemokine receptor-2 ligand are necessary components of neutrophil-mediated host defense in invasive pulmonary aspergillosis. J Immunol. 1999;163:6086–6094. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Mehrad B, Wiekowski M, Morrison BE, Chen S-C, Coronel EC, Manfra DJ, Lira SA. Transient lung-specific expression of the chemokine KC improves outcome in invasive aspergillosis. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2002;166:1159–1160. doi: 10.1164/rccm.200204-367OC. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Tsai WC, Strieter RM, Wilkowski JM, Bucknell KA, Burdick MD, Lira SA, Standiford TJ. Lung-specific transgenic expression of KC enhances resistance to Klebsiella peumoniae in mice. J Immunol. 1998;161:2435–2440. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Boisevert WA, Rose DM, Johnson KA, Fuentes ME, Lira SA, Curtiss LK, Terkeltaub RA. Up-regulated expression of the CXCR2 ligand KC/GRO-α in atherosclerotic lesions plays a central role in macrophage accumulation and lesion progression. Am J Path. 2006;168:1385–1395. doi: 10.2353/ajpath.2006.040748. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Keepers TR, Psotka MA, Gross LK, Obrig TG. A murine model of HUS: Shiga toxin with lipopolysaccharide mimics the renal dmage and physiologic response of human disease. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2006;17:3404–3414. doi: 10.1681/ASN.2006050419. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Roche JK, Keepers TR, Gross LK, Seaner RM, Obrig TG. CXCL1/KC and CXCL2/MIP-2 are critical effectors and potential targets for therapy of Escherichia coli 0157:H7-associated renal inflammation. Am J Pathology. 2007;170:526–537. doi: 10.2353/ajpath.2007.060366. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Fukata M, Michelsen KS, Eri R, Thomas LS, Hu B, Lukasek K, Nast CC, Lechago J, Xu R, Naiki Y, Soliman A, Arditi M, Abreu MT. Toll-like receptor-4 is required for intestinal response to epithelial injury and limiting bacterial translocation in a murine model of acute colitis. Am J Physiol Gastrointest Liver Physiol. 2005;288:G1055–G1065. doi: 10.1152/ajpgi.00328.2004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Atreya R, Mudter J, Finotto S, Mullberg J, Jostock T, Wirtz S, Schutz M, Bartsch B, Holtmann M, Becker C, Strand D, Czaja J, Schlaak JF, Lehr HA, Autschbach F, Schurmann G, Nishimoto N, Yoshizaki K, Ito H, Kishimoto T, Galle PR, Rose-John S, Neurath MF. Blockade of interleukin 6 trans signaling suppresses T-cell resistance against apoptosis in chronic intestinal inflammation: evidence in crohn disease and experimental colitis in vivo. Nat Med. 2000;6:583–588. doi: 10.1038/75068. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Cooper HS, Murthy SN, Shah RS, Sedergran DJ. Clinicopathologic study of dextran sulfate sodium experimental murine colitis. Lab Invest. 1993;69:238–249. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.El Asmar, El Asmar R, Panigrahi P, Bamford P, Berti I, Not T, Coppa GV, Catassi C, Fasano A. Host-dependent zonulin secretion causes the impairment of the small intestine barrier function after bacterial exposure. Gastroenterology. 2002;123:1607–1615. doi: 10.1053/gast.2002.36578. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Rakoff-Nahoum S, Paglino J, Eslami-Varzaneh F, Edberg S, Medzhitov R. Recognition of commensal microflora by toll-like receptors is required for intestinal homeostasis. Cell. 2004;118:229–241. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2004.07.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Thomas KE, Sapone A, Fasano A, Vogel SN. Gliadin stimulation of murine macrophage inflammatory gene expression and intestinal permeability are MyD88-dependent: role of the innate immune response in celiac disease. J Immunol. 2006;176:2512–2521. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.176.4.2512. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kuhn R, Lohler J, Rennick D, Rajewsky K, Muller W. Interleukin-10-deficient mice develop chronic enterocolitis. Cell. 1993;75:263–274. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(93)80068-p. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Davidson NJ, Fort MM, Muller W, Leach MW, Rennick DM. Chronic colitis in IL-10−/− mice: insufficient counter regulation of a Th1 response. Intl Rev Immunol. 2000;19:91–121. doi: 10.3109/08830180009048392. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Abreu MT, Thomas LS, Arnold ET, Lukasek K, Michelsen KS, Arditi M. TLR signaling at the intestinal epithelial interface. J Endotoxin Res. 2003;9:322–330. doi: 10.1179/096805103225002593. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Berg DJ, Davidson N, Kuhn R, Muller R, Menon S, Holland G, Thompson-Snipes L, Leach MW, Rennick D. Enterocolitis and colon cancer in interleukin-10-deficient mice are associated with aberrant cytokine production and CD4+ TH1-like responses. J Clin Invest. 1996;98:1010–1020. doi: 10.1172/JCI118861. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Froicu M, Cantorna M. Vitamin D and the vitamin D receptor are critical for control of the innate immune response to colonic injury. BMC Immunology. 2007;8:5–11. doi: 10.1186/1471-2172-8-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Fan X, Patera AC, Pong-Kennedy A, Deno G, Gonsiorek W, Manfra DJ, Vassileva G, Zeng M, Jackson C, Sullivan L, Sharif-Rodriquez W, Opdenakker G, Van Damme J, Hedrick JA, Lundell D, Lira SA, Hipkin RW. Murine CXCR1 is a functional receptor for GCP-2/CXCL6 and interleukin-8/CXCL8. J Biol Chem. 2007;282:11658–11666. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M607705200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Buanne P, Di Carlo E, Caputi L, Brandolini L, Mosca M, Cattani F, Pellegrini L, Biordi L, Coletti G, Sorentino C, Fedele G, Colotta F, Melillo G, Bertini R. Crucial pathophysiological role of CXCR2 in experimental ulcerative colitis in mice. J Leuk Biol. 2007;82:1239–1246. doi: 10.1189/jlb.0207118. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Güler ML, Gorham JD, Hsieh CS, Mackey AJ, Steen RG, Dietrich WF, Murphy KM. Genetic susceptibility to Leishmania: IL-12 responsiveness in TH1 cell development. Science. 1996;271:984–987. doi: 10.1126/science.271.5251.984. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.JAX Notes No. 507, Fall 2007. pp. 3–4.

- 30.Hanauer S. Inflammatory bowel disease: epidemiology, pathogenesis, and therapeutic opportunities. Inflam Bowel Dis. 2006;12(suppl 1):S3–9. doi: 10.1097/01.mib.0000195385.19268.68. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Imada A, Ina K, Shimada M, Yokoyama T, Yokoyama Y, Nishio Y, Yamaquchi T, Ando T, Kusugami K. Coordinate upregulation of interleukin-8 and growth-related gene producted-alpha is present in the colonic mucosa of inflammatory bowel. Scand J Gastronenterol. 2001;36:854–864. doi: 10.1080/003655201750313397. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Hans W, Schölmerich J, Gross V, Falk W. Interleukin-12 induced interferon-γ increases inflammation in acute dextran sulfate sodium induced colitis in mice. European Cytokine Network. 2000;11:67–74. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Qualls JE, Kaplan AM, van Rooijen N, Cohen DA. Suppression of experimental colitis by intestinal mononuclear phagocytes. J Leuk Biol. 2006;80:802–815. doi: 10.1189/jlb.1205734. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]