Abstract

To test the Italian translation of Corah's Dental Anxiety Scale (DAS) and to check the relationship between dental anxiety and the American Society of Anesthesiologists (ASA) physical status classification (ASA-PS), the DAS was translated into Italian and administered to 1072 Italian patients (620 male and 452 female patients, ages 14–85 years) undergoing oral surgery. Patients' conditions were checked and rated according to the ASA-PS. The DAS ranged from 4 to 20 (modus = 8, median = 10); 59.5% of patients had a DAS of 7–12, 26.1% had a DAS >12, and 10.3% had a DAS >15. The mean DAS was 10.29 (95% confidence limit = 0.19); female patients were more anxious than male patients (P < .001), while patients older than 60 years showed a significant decrease in the level of anxiety. Five hundred two patients were rated as ASA-PS class P1, 502 as ASA-PS class P2, and 68 as ASA-PS class P3, with a mean DAS score of 9.69, 10.78, and 11.09, respectively: the DAS difference between groups was significant (P < .001).

Keywords: Anxiety, Dentistry, Dental anxiety scale, Visual analogue scale, Psychological tests, Methods, Dental phobia, Physical status

The relevance of psychology and behavioral sciences is ever increasing both in dental education and in clinical practice. A high percentage of patients are so fearful of dental care as to delay or avoid attendance. Other than avoidance behavior, dental anxiety has a wide-ranging and dynamic impact on a person's life. Therefore, careful assessment of anxiety and treatment is an essential step for appropriate patient management and overall quality of care.

The evaluation of dental anxiety can be performed with a wide range of approaches, including several psychologic tests able to explore general aspects of anxiety and/or dental anxiety. A comprehensive review of main tests for anxiety and pain evaluation in dentistry has been published by Newton and Buck in 2000.9 Out of 15 tests mentioned in this review, the Corah Dental Anxiety Scale (DAS)10–12 results are the most widely used. The Corah DAS shapes 4 dentally related situations, each including 5 responses of increasing anxiety; the sum of responses ranges between 4 and 20, where scores higher than 12 indicate anxious patients,13–18 and scores higher than 15 indicate phobic levels of anxiety.9

The DAS diffusion in clinical practice depends on the fact that it is well validated, reproducible, focused on dental fear, fast, and simple. It has been used in both adults15,19–26 and children,27–31 showing a high internal consistency and test-retest reliability,10 and is available in 4 European languages (German, Norwegian, Dutch, and Hungarian).24,32–34 In Italy there is a surprising shortage of Italian-language tests for dental fear. To our knowledge, only 1 paper has been published so far in the literature on the use of DAS in Italian patients.35,36 However, the paper deals with adolescents only, while the Italian translation of the test they used has not been published. As far as studies from other countries are concerned, the largest series available in the literature deal with normal subjects, such as university students and soldiers, while most studies on patients include a smaller number of cases: it is to be considered that patients who are going to be operated on might be more anxious and, thus, have a higher DAS score than the normal population.

The aims of this study are to check: (a) the Italian translation of the DAS and its reliability in a large sample of adult patients undergoing oral surgery and (b) the relationship between the American Society of Anesthesiologists (ASA) physical status classification and dental anxiety.

Materials and Methods

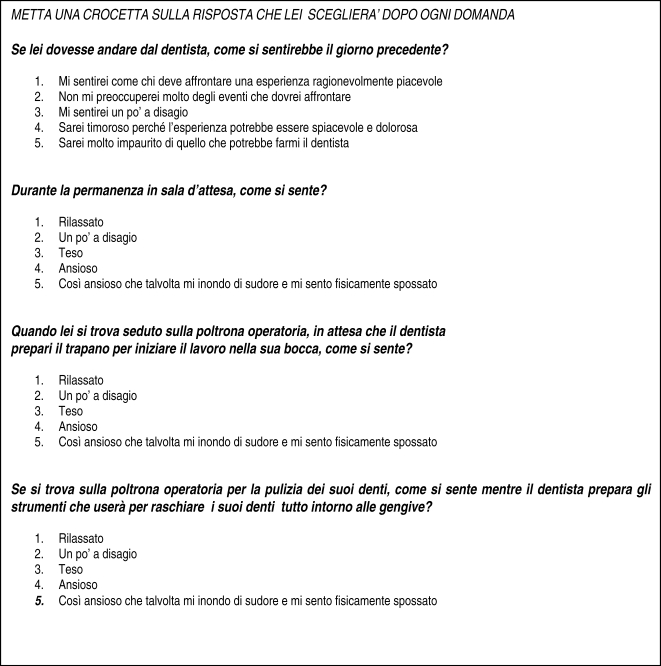

The Corah DAS was translated from English into Italian by each of the authors, and the draft versions were discussed in order to reach an agreement. Then, the final version was back-translated into English by an interpreter, and tested for inconsistencies. The study was approved by our local ethical committee, and all the patients gave their informed consent.

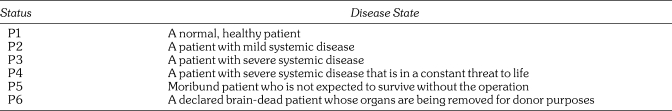

In our department, the anesthesiologic examination is part of routine preoperative assessment for patients submitted to major oral surgery (eg, implantology, multiple teeth extraction), patients with increased perioperative risk due to coexisting diseases, and fearful patients; conscious sedation is routinely available for all of these patients. One thousand seventy-two consecutive patients, 620 male (57.8%) and 452 female (42.2%), ranging between the age of 14 and 85 years (mean ± SD = 53.8 ± 14.0), filled out the Italian version of the Corah DAS (Figure 1) at the beginning of the preoperative examination, before any other evaluation of patients' physical conditions and information about sedation. Patients who were unwilling or unable to fill out the DAS, due to their clinical conditions (eg, neurologic or psychiatric disorders) or foreign nationality were discarded from the study. The patients were asked to select the option that best represented their experience in the DAS, and the total score was then calculated by summing the values of each selected option. After DAS administration, the clinical conditions were checked and rated according to the ASA physical status classification37 (Table 1). Conscious sedation during the operation was proposed to all patients and planned at the end of the visit, after assessment of their physical condition. The statistical analysis was conducted with Cronbach alpha, t test, and 1-way ANOVA with post-hoc test according to Bonferroni, using the SPSS 13.0 for Windows program (SPSS Inc, Chicago, Ill), for a significance level of P < .05.

Figure 1.

The Italian translation of the Dental Anxiety Scale by Corah.

Table 1.

American Society of Anesthesiologists Physical Status Classification37

Results

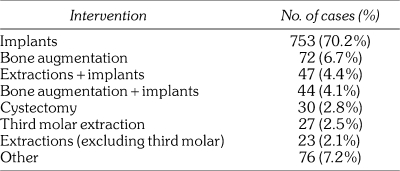

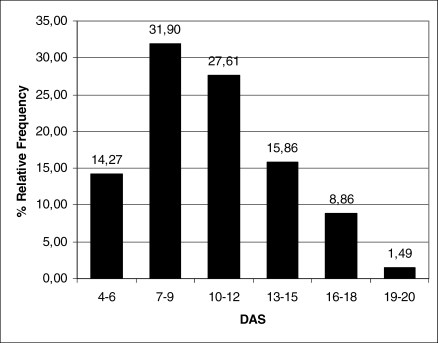

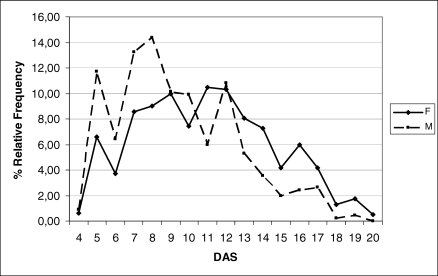

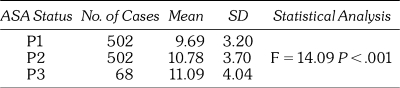

Five hundred two patients (46.8%) belonged to class P1, 502 (46.8%) to class P2, and 68 (6.4%) to class P3. The type of intervention is shown in Table 2. Figure 2 shows the distribution of DAS scores in our sample: the DAS score ranged from 4 to 20 with modus = 8 and median = 10. About 60% of patients had a score ranging between 7 and 12, while 26.1% had scores higher than 12, and 10.3% reached phobic levels of anxiety (that is, DAS>15). The Italian version of the DAS also showed a very good internal consistency with Cronbach alpha = .883. The distribution of DAS scores in female patients was shifted toward right, when compared with male patients, showing a higher level of anxiety (Figure 3).

Table 2.

Interventions in 1072 Patients Submitted to Oral Surgery

Figure 2.

Distribution of Dental Anxiety Scale (DAS) scores in 1072 patients undergoing oral surgery.

Figure 3.

Distribution of Dental Anxiety Scale (DAS) scores in both sexes: female patients show higher levels of anxiety, as defined by the DAS.

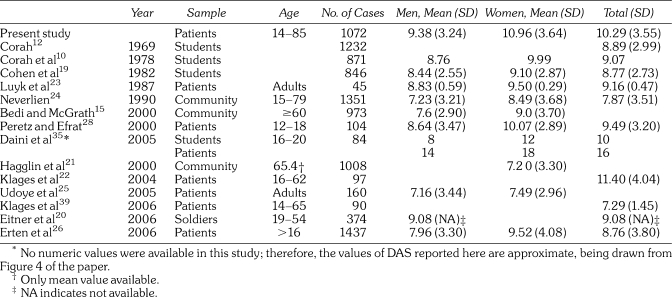

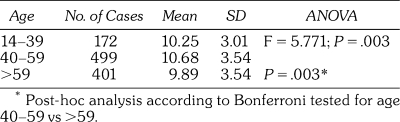

The mean scores and SD of male and female patients and both combined, together with the results of other previous reports, are shown in Table 3. The mean DAS score of the whole sample was 10.29, with a 95% confidence limit of 0.19, with a highly significant difference between male and female patients (t = 7.338; P < .001). Our mean and SD were similar to those reported by other studies dealing with patients, while studies on students and community showed a lower DAS score; in the former, the range of the mean DAS score was 7.29–11.40, while in the latter it was 7.87–9.08. The DAS was significantly related to the age as well (Table 4), with a level of anxiety significantly lower in patients older than 60 years of age (P = .003).

Table 3.

Mean Dental Anxiety Scale Scores in 1072 Italian Patients, Compared With Data From Other Previous Studies in Other Countries

Table 4.

Relationship Between Dental Anxiety Scale and Age

The level of anxiety was significantly related to the physical status as well (Table 5). Patients belonging to ASA class P2 and P3 (that is, patients with mild and severe systemic disease, respectively) showed a significantly higher DAS score than patients belonging to ASA class P1 (healthy subjects).

Table 5.

Relationship Between ASA Physical Status Classification and Dental Anxiety Scale Scores

Discussion

Dental fear is a universal phenomenon, since all over the world, approximately 25% of patients avoid visits and treatments, and approximately 10% reach phobic levels of anxiety. It has manifold endogenous and exogenous causes38: the latter include conditioned fear (yielded by previous bad experiences), distrust of dental professionals, and somatic intraoperative reactions, which may change in function of dental experience.

The problem is of paramount importance for several reasons: (a) avoidance causes worse oral health and quality of life; (b) high levels of anxiety and phobia may impinge on the dentist/patient relationship, may prevent proper dental treatment, and be a cause of intraoperative complications; and (c) the sympathetic response to stress caused by anxiety may yield harmful reactions, such as vasovagal syncope, hypertension, tachycardia, and cardiovascular accidents. The latter is of paramount importance in patients with increased risk (namely ASA class P2 and higher), where the diagnosis and treatment of dental anxiety becomes essential for patient's safety.

The DAS is the most widely used and validated test for dental anxiety and is available in several European languages. No Italian versions of the DAS are available yet, and, in general, there is a surprising lack of Italian versions of anxiety tests, even though there is no reason to expect a lower anxiety in our patients. It probably depends on 2 different factors: (a) underestimation of the relevance of anxiety assessment in clinical practice; and (b) use of self-made, untested individual translations. Consequently, there is an increasing need for validating Italian translations and adopting standard validated versions, in order to assure comparability of data. Only 1 study on the DAS has been published so far in Italian patients, regarding adolescents only,35 while no data are available in adults. In this study, several aspects of anxiety (ie, fear as a general reaction to life, dental fear, and anxiety as a personal characteristic) as well as the level of oral hygiene were evaluated in adolescent patients and in high school students, in order to check how dental care affected state and dental anxiety. The patients showed a higher level of anxiety than students (yielded by dental care), with girls significantly more anxious than boys, while a better knowledge of dental hygiene was not enough to decrease anxiety, suggesting the need for specific preventive anxiety care. The Spielberger State Trait Anxiety Test, showed a close correlation with DAS and showed a high level of both state and trait anxiety in this series. The approximate figures of DAS from this study are reported in Table 3 (the exact numbers were not available, since the results were only plotted as a bar graph) and suggest the following remarks: (a) the values of patients look much higher than those reported by Peretz and Efrat28; (b) these values reach phobic levels in girls; and (c) the high DAS scores, being associated with a high level of both state and trait anxiety, suggest that the patients were referred to the University hospital because of their anxiety and do not represent a casual sample. Unfortunately, the Italian translation of the DAS was not reported in the study by Daini et al.35

The aim of our study was to check the Italian translation of the DAS in a large sample of patients undergoing oral surgery. Our results show that the mean DAS score in an Italian population is in the range of the one reported by published papers from other countries, dealing with patients attending dental clinics; however, it looks slightly higher than the one reported in studies on community. The differences may reflect sample variability, cultural differences across nations, and the likely increase of anxiety when waiting for surgical treatment. According to other reports, the anxiety is higher in female patients and lower in the elderly, while about 25% have high levels of anxiety (DAS>12) and 10% reach phobic levels (DAS>15).

The significant relationship between anxiety and ASA physical status classification shows a new factor involved in dental anxiety, which, to our knowledge, has not yet been identified. Since anxiety may change as a function of experience,38 dental anxiety may be affected by medical, besides dental, experiences. In fact, patients suffering from chronic systemic diseases are to face the concern for their illness and experience more or less invasive diagnostic and therapeutic medical interventions. All these factors, likewise dental treatments, may increase anxiety. This is a relevant aspect of patient assessment since patients with coexisting systemic diseases are more likely to undergo perioperative complications, which, in turn, may be fostered by somatic reactions yielded by disease-related anxiety. Moreover, the close relationship between ASA physical status classification and the DAS discloses the mutual impact of systemic diseases on dental anxiety and of dental anxiety on systemic diseases, along with the relevance of anxiety assessment in patients belonging to ASA class P2 and P3.

The good consistency between our data and those reported in the literature shows the comparability of data and the reliability of the Italian version of the DAS, supporting its use in the assessment of dental anxiety in Italian patients. The close relationship between DAS and ASA classification of physical status suggests that dental anxiety is affected by medical as well as dental experiences, emphasizing the relevance of anxiety assessment in patients belonging to ASA-PS class P2 and P3. Further studies on the role of coexisting systemic diseases in dental anxiety are required.

Conclusions

Our data show the reliability of the Italian version of the DAS and support its use in Italian patients. The relationship between DAS and ASA-PS show that dental anxiety is affected by medical, besides dental, experiences, where an increased intraoperative risk is paralleled by increased anxiety.

References

- Berggren U, Linde A.Dental fear and avoidance: a comparison of two modes of treatment J Dent Res 198463( 10) 1223–1227. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berggren U, Pierce C.J, Eli I.Characteristics of adult dentally fearful individuals. A cross-cultural study Eur J Oral Sci 2000108( 4) 268–274. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cohen S.M, Fiske J, Newton J.T.The impact of dental anxiety on daily living Br Dent J 2000189( 7) 385–390. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hakeberg M, Berggren U, Carlsson S.G, Grondahl H.G.Long-term effects on dental care behavior and dental health after treatments for dental fear Anesth Prog 199340( 3) 72–77. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moore R, Brødsgaard I, Mao T.K, Kwan H.W, Shiau Y.Y, Knudsen R.Fear of injections and report of negative dentist behavior among Caucasian American and Taiwanese adults from dental school clinics Community Dent Oral Epidemiol 199624( 4) 292–295. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McGrath C, Bedi R.The association between dental anxiety and oral health-related quality of life in Britain Community Dent Oral Epidemiol 200432( 1) 67–72. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haugejorden O, Klock K.S.Avoidance of dental visits: the predictive validity of three dental anxiety scales Acta Odontol Scand 200058( 6) 255–259. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mellor A.C.Dental anxiety and attendance in the north-west of England J Dent 199220( 4) 207–210. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Newton J.T, Buck D.J.Anxiety and pain measures in dentistry: a guide to their quality and application J Am Dent Assoc 2000131( 10) 1449–1457. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Corah N.L, Gale E.N, Illig S.J.Assessment of a dental anxiety scale J Am Dent Assoc 197897( 5) 816–819. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Corah N.L.Dental anxiety. Assessment, reduction and increasing patient satisfaction Dent Clin North Am 198832( 4) 779–790. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Corah N.L.Development of a dental anxiety scale J Dent Res 196948( 4) 596. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sohn W, Ismail A.I.Regular dental visits and dental anxiety in an adult dentate population J Am Dent Assoc 2005136( 1) 58–66. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ekanayake L, Dharmawardena D.Dental anxiety in patients seeking care at the University Dental Hospital in Sri Lanka Community Dent Health 200320( 2) 112–116. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bedi R, McGrath C.Factors associated with dental anxiety among older people in Britain Gerodontology 200017( 2) 97–103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kruger E, Thomson W.M, Poulton R, Davies S, Brown R.H, Silva P.A.Dental caries and changes in dental anxiety in late adolescence Community Dent Oral Epidemiol 199826( 5) 355–359. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thomson W.M, Poulton R.G, Kruger E, Davies S, Brown R.H, Silva P.A.Changes in self-reported dental anxiety in New Zealand adolescents from ages 15 to 18 years J Dent Res 199776( 6) 1287–1291. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thomson W.M, Stewart J.F, Carter K.D, Spencer A.J.Dental anxiety among Australians Int Dent J 199646( 4) 320–324. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cohen L.A, Snyder T.L, LaBelle A.D.Correlates of dental anxiety in a university population J Public Health Dent 198242( 3) 228–235. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eitner S, Wichmann M, Paulsen A, Holst S.Dental anxiety—an epidemiological study on its clinical correlation and effects on oral health J Oral Rehabil 200633( 8) 588–593. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hagglin C, Hakeberg M, Ahlqwist M, Sullivan M, Berggren U.Factors associated with dental anxiety and attendance in middle-aged and elderly women Community Dent Oral Epidemiol 200028( 6) 451–460. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Klages U, Ulusoy O, Kianifard S, Wehrbein H.Dental trait anxiety and pain sensitivity as predictors of expected and experienced pain in stressful dental procedures Eur J Oral Sci 2004112( 6) 477–483. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Luyk N.H, Beck F.M, Weaver J.M.A visual analogue scale in the assessment of dental anxiety Anesth Prog 198835( 3) 121–123. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Neverlien P.O.Normative data for Corah's Dental Anxiety Scale (DAS) for the Norwegian adult population Community Dent Oral Epidemiol 199018( 3) 162. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Udoye C.I, Oginni A.O, Oginni F.O.Dental anxiety among patients undergoing various dental treatments in a Nigerian teaching hospital J Contemp Dent Pract 20056( 2) 91–98. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Erten H, Akarslan Z.Z, Bodrumlu E.Dental fear and anxiety levels of patients attending a dental clinic Quintessence Int 200637( 4) 304–310. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Majstorovic M, Skrinjaric I, Glavina D, Szirovicza L.Factors predicting a child's dental fear Coll Antropol 200125( 2) 493–500. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peretz B, Efrat J.Dental anxiety among young adolescent patients in Israel Int J Paediatr Dent 200010( 2) 126–132. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bedi R, Sutcliffe P, Donnan P.T, McConnachie J.The prevalence of dental anxiety in a group of 13- and 14-year-old Scottish children Int J Paediatr Dent 19922( 1) 17–24. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Neverlien P.O, Backer J.T.Optimism-pessimism dimension and dental anxiety in children aged 10–12 years Community Dent Oral Epidemiol 199119( 6) 342–346. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Neverlien P.O.Fear and dental apprehension among school-age children in a rural district [in Norwegian] Nor Tannlaegeforen Tid 198999( 15) 574–578. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eijkman M.A, Orlebeke J.F. De factor ‘angst’ in de tandheelkundige situatie. Nederlands Tijdschrift voor Taandheekunde. 1975;82:114–123. [Google Scholar]

- Kunzelmann K.H, Dunninger P.Dental fear and pain: effect on patient's perception of the dentist Community Dent Oral Epidemiol 199018( 5) 264–266. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fabian T.K, Kelemen P, Fabian G.Introduction of the concept of Dental Anxiety Scale in Hungary. Epidemiologic studies on the Hungarian population [in Hungarian] Fogorv Sz 199891( 2) 43–52. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Daini S, Errico A, Quinti E, Manicone P.F, Raffaelli L, Rossi G.Dental anxiety in adolescent people Minerva Stomatol 200554( 11–12) 647–659. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Desiate A, Fanelli M, Milano V.“Odontogenic” anxiety. A study of a population of 1500 students from the public schools in the Bari area [in Italian] Minerva Stomatol 199746( 4) 165–173. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- ASA Physical Status Classification System. 2008. Available at: http://www.asahq.org/clinical/physicalstatus.htm. Accessed June 18, 2008.

- Liddell A, Locker D.Changes in levels of dental anxiety as a function of dental experience Behav Modif 200024( 1) 57–68. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Klages U, Kianifard S, Ulusoy O, Wehrbein H.Anxiety sensitivity as predictor of pain in patients undergoing restorative dental procedures Community Dent Oral Epidemiol 200634( 2) 139–145. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]