Abstract

The objective of this study was to determine the effects and mechanisms of serum amyloid A (SAA) on coronary endothelial function. Porcine coronary arteries and human coronary arterial endothelial cells (HCAECs) were treated with SAA (0, 1, 10, or 25 μg/ml). Vasomotor reactivity was studied using a myograph tension system. SAA significantly reduced endothelium-dependent vasorelaxation of porcine coronary arteries in response to bradykinin in a concentration-dependent manner. SAA significantly decreased endothelial nitric oxide (NO) synthase (eNOS) mRNA and protein levels as well as NO bioavailability, whereas it increased ROS in both artery rings and HCAECs. In addition, the activities of internal antioxidant enzymes catalase and SOD were decreased in SAA-treated HCAECs. Bio-plex immunoassay analysis showed the activation of JNK, ERK2, and IκB-α after SAA treatment. Consequently, the antioxidants seleno-l-methionine and Mn(III) tetrakis-(4-benzoic acid)porphyrin and specific inhibitors for JNK and ERK1/2 effectively blocked the SAA-induced eNOS mRNA decrease and SAA-induced decrease in endothelium-dependent vasorelaxation in porcine coronary arteries. Thus, SAA at clinically relevant concentrations causes endothelial dysfunction in both porcine coronary arteries and HCAECs through molecular mechanisms involving eNOS downregulation, oxidative stress, and activation of JNK and ERK1/2 as well as NF-κB. These findings suggest that SAA may contribute to the progress of coronary artery disease.

Keywords: endothelial nitric oxide synthase, reactive oxygen species, antioxidant, mitogen-activated protein kinase, nuclear factor-κB

it is well known that inflammation plays a crucial role in the pathogenesis of atherosclerosis (29). Serum amyloid A (SAA) belongs to a family of the major acute-phase proteins in vertebrates and was discovered in 1971 as a principal constituent within the amyloid deposits of patients with persistent inflammation (31, 44, 47). Recent studies have shown that increased levels of SAA are strongly associated with many inflammation conditions including cardiovascular diseases (11, 22, 32). For example, SAA levels have also been correlated with the severity of human coronary artery atherosclerosis (32) and many cardiovascular risk factors including obesity, insulin resistance, diabetes (26), and rheumatoid arthritis (50). SAA can bind to extracellular vascular glycans and impair the ability of HDL to promote cholesterol efflux from macrophages (3). Lewis et al. (27) reported that circulating SAA levels, but not lipid levels, were strongly associated with the extent of aortic atherosclerosis in a mouse model, and SAA colocalized with apolipoprotein A-I and proteoglycans in atherosclerotic lesions. SAA may bind and transport cholesterol into aortic smooth muscle cells (28). Additionally, SAA also promotes monocyte chemotaxis and adhesion (4). These data suggest that SAA is a biomarker and biomediator for cardiovascular disease.

Decreased bioavailability of nitric oxide (NO) produced from endothelial NO synthase (eNOS) plays a crucial role in the development and progression of atherosclerosis (51). eNOS converts l-arginine to l-citrulline and NO in the endothelium. Modulation of eNOS gene expression or activity can, in turn, control the NO signaling (7). Impaired eNOS activity leads to a decrease in the relative bioavailability of NO, which not only impairs endothelium-dependent vasorelaxation but also activates other mechanisms that have an important role in the pathogenesis of atherosclerosis (36). Furthermore, eNOS and NO levels can be modulated by reactive oxygen species (ROS), which can result in the activation of various signaling pathways, including MAPKs (14, 18). In the vascular system, ROS may react with and reduce NO bioavailability, leading to the endothelial dysfunction found in a number of cardiovascular disease states, including hypertension, chronic heart failure, and atherosclerosis (42). However, the precise mechanisms by which endothelial cells maintain the physiological levels of NO and ROS, such as superoxide anion, are not completely understood.

Despite the clinical implications, limited biological functions of SAA have been reported, and the role and mechanisms of SAA in endothelial functions have not been fully elucidated. In the present study, we tested the hypothesis that SAA may induce endothelial dysfunction by downregulating eNOS expression through oxidative stress and MAPK activation. Specifically, the effects of SAA on eNOS mRNA and protein levels were determined in human coronary artery endothelial cells (HCAECs) and porcine coronary artery rings. NO bioavailability, ROS production, and the internal antioxidant enzymes catalase (CAT) and SOD as well as MAPK phosphorylation were investigated. This study may provide new insights into the mechanisms of SAA-related endothelial dysfunction and its association with cardiovascular disease.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Chemicals and reagents.

Recombinant human apolipoprotein SAA was obtained from Leinco Technologies (St. Louis, MO). The endotoxin level in the SAA preparation was <1.0 EU/μg. DMSO, the thromboxane A2 analog U-46619, bradykinin, sodium nitroprusside (SNP), seleno-l-methionine (SeMet), NG-nitro-l-arginine methyl ester (l-NAME), and the Tri-Reagent kit were obtained from Sigma Chemical (St. Louis, Mo). The ERK1/2 inhibitor PD-98059, p38 inhibitor SB-239063, and JNK inhibitor SP-600125 were obtained from Calbiochem (San Diego, CA). Dihydroethidium (DHE), 4-amino-5-methylamino-2′,7′-difluorofluorescein diacetate (DAF-FM DA), and lucigenin were purchased from Molecular Probes (Eugene, OR). DMEM was obtained from Life Technologies (Grand Island, NY). The antibody against human eNOS was obtained from BD Transduction Laboratories (Lexington, KY). Biotinylated horse anti-mouse IgG and the avidin-biotin complex kit were obtained from Vector Labs (Burlingame, CA). Mn(III) tetrakis-(4-benzoic acid)porphyrin (MnTBAP) was purchased from A. G. Scientific (San Diego, CA).

Myograph model.

Fresh porcine hearts were harvested from young adult farm pigs (6–7 mo old) at a local slaughterhouse, placed in a container filled with cold PBS solution, and immediately transported to the laboratory. Fresh porcine right coronary arteries were carefully dissected and cut into multiple 5-mm rings. The rings were then incubated in DMEM with 1, 10, or 25 μg/ml of SAA at 37°C and 5% CO2 for 24 h. The myograph tension system used in our laboratory has been previously described (10). Briefly, rings were suspended between the wires of the organ bath myograph chamber in 6 ml of Krebs solution, maintained at 37°C, and oxygenated with pure oxygen gas. Rings were slowly subjected stepwise to a predetermined optimal tension of 30 mN, and each ring was precontracted with the thromboxane A2 analog U-46619 (final concentration: 3 × 10−8 M), which precontracted vascular rings ∼60% of the maximal contraction (see Supplemental Fig. S1).1 After 60–90 min of contraction, a relaxation curve was generated by adding 60 μl of five cumulative additions of the endothelium-dependent vasodilator bradykinin (final concentrations: 10−9–10−5 M) every 3 min. In addition, SNP (final concentration: 10−6 M) was added into the organ bath, and endothelium-independent vasorelaxation was recorded. In a separate experiment, serial concentrations of U-46619 and SNP were used.

Lucigenin-enhanced chemiluminescence assay.

Levels of ROS produced by endothelial cells of porcine arteries were detected using the lucigenin-enhanced chemiluminescence method as previously described in our study (10). Six sets of vessel rings in each group were used. Briefly, rings were cut open longitudinally and trimmed into 5 × 5-mm pieces. An assay tube was filled with 5 μM lucigenin, and the vessel segment was placed endothelium side down in the tube to record signals from the endothelial layer. Time-based reading of the luminometer was recorded. Data, in relative light units (RLU) per second for each sample, were averaged between 5 and 10 min. Values of blank tubes containing the same reagents as the vessel ring samples were subtracted from their corresponding vessel samples. The area of each vessel segment was measured using a caliper and was used to normalize the data for each sample. Final data are represented as RLU per second per millimeter squared. ROS production and distribution in the porcine coronary artery ring were also visualized by DHE staining on frozen and unfixed tissue sections.

Cell culture.

HCAECs and endothelial growth medium (EGM)-2 were purchased from Cambrex BioWhittaker (Walkersville, MD). Cells were used at passages 6–8. When HCAECs grew to 80–90% confluence in six-well plates, they were divided into four groups. In group I, cells were treated with different concentrations (1, 10, or 25 μg/ml) of SAA for various periods of time (6, 24, or 48 h). In group II, cells were cocultured with SeMet (10 μM) or MnTBAP (2 μM) and SAA (10 μg/ml) for 24 h. In group III, cells were treated with SAA (10 μg/ml) for 5 min, 15 min, 30 min, 40 min, 60 min, 2 h, or 24 h. In group IV, cells were pretreated with p38 inhibitor (SB-239063, 1 μM), ERK1/2 inhibitor (PD-98059, 40 μM), or JNK inhibitor (SP-600125, 40 μM) for 1 h and then cocultured with SAA (10 μg/ml) for 24 h. In all groups, cells cultured in EGM-2 alone were used as negative controls.

Real-time PCR.

Porcine endothelial cells were isolated from cultured porcine coronary artery rings by scraping the luminal surface with surgical blades. Total RNA from porcine endothelial cells and HCAECs was isolated using the Tri-Reagent kit following the manufacturer's directions. Primers of eNOS (human and porcine), human CAT, SOD, GAPDH, and porcine CD31 were designed via Beacon Designer 2.1 software (Bio-Rad) (see Supplemental Table S1). Porcine CD31 was used to normalize porcine eNOS mRNA levels to exclude potential protein contaminations from porcine smooth muscle cells. For HCAECs, GAPDH was used to normalize eNOS, CAT, and SOD mRNA levels. The iQ SYBR green Supermix Kit and iCycler iQ Real-Time PCR detection system (Bio-Rad) were used in real-time PCR. Controls were performed with no reverse transcriptase (mRNA sample only) or no mRNA (water only) to demonstrate the specificity of the primers and the lack of DNA contamination in the samples. Relative mRNA levels of eNOS, CAT, and SOD are presented as  , where Ct is the threshold cycle, as previously described (48).

, where Ct is the threshold cycle, as previously described (48).

Western blot analysis.

Total proteins were isolated from HCAECs using the Tri-Reagent kit. Equal amounts of total proteins were loaded using 10% SDS-PAGE, fractionated by electrophoresis, and transferred to nitrocellulose membranes. The membrane was incubated with the primary antibody at 4°C overnight. Dilutions of 1:1,000 for eNOS monoclonal antibody and 1:10,000 for β-actin monoclonal antibody were used. Bands were visualized with ECL Plus Chemiluminescent substrate (Amersham Biosciences). Densitometric measurements were performed to quantify the relative expression of eNOS proteins versus β-actin (AlphaEaseFC software).

Nitrite detection.

NO levels released from vessel rings and HCAECs were determined by measuring the accumulation of its stable degradation products, nitrite and nitrate (Griess Reaction NO Assay kit, Calbiochem). Nitrate is reduced to nitrite by nitrate reductase. Thus, total nitrite levels represent total NO levels. Porcine coronary rings and HCAECs were cultured with or without SAA for 24 h. The supernatant was collected, and total nitrite levels were measured. Absorbance of the samples was determined at 540-nm wavelength and compared with standard solutions. The amount of nitrite detected was normalized to the area of the cultured rings (in μM/mm2) or total proteins of HCAECs (in μM/mg).

Flow cytometry.

Cells were harvested with 0.02% trypsin-EDTA and adjusted to 1 × 106 cells/FACS tube. For ROS and NO staining, DHE (3 μM) and DAF-FM DA (10 μM) were added, respectively, and incubated in 37°C for 30 min. ROS and NO levels in cells were analyzed by FACS Calibur flow cytometry (Becton Dickinson). In each experiment, at least 10,000 events were analyzed.

Measurements of CAT and SOD activity.

HCAECs were homogenized and centrifuged in HEPES buffer (pH 7.4) containing 1 mM EDTA. CAT and SOD enzyme activities were measured with commercial enzyme assay kits (Cayman Chemical) following the manufacturer's protocols. CAT and SOD enzyme activities were calculated from the average absorbance of each sample using the equations provided in the kit manuals. Final data for CAT activity are presented as means ± SE (in nmol·min−1·ml−1); final data for SOD are presented as means ± SE (in U/ml).

Bio-plex immunoassay.

HCAECs were cultured with 10 μg/ml of SAA for 0 min, 5 min, 15 min, 30 min, 45 min, 60 min, 2 h, or 24 h. Cell lysate was prepared using the kit obtained from Bio-Rad. Detection of phosphorylated and total ERK1/2, JNK, p38, and IκB-α was performed according to the manufacturer's protocol. Each test included four positive controls provided by Bio-Rad to monitor detector stability and specimen and sample integrity. Final data were analyzed and presented as the ratio of phosphoprotein to total protein for each MAPK and for IκB-α (average of triplicates).

Statistical analysis.

Statistical analysis was completed by comparing the data from treatment and control groups using Student's t-test (two-tailed). The vasomotor reactivity in response to serial concentrations of vasoactive drugs with multiple groups and data points was analyzed by ANOVA (two-tailed) followed by Bonferroni-Dunn's post hoc test (Minitab software, Sigma Breakthrough Technologies, San Marcos, TX). P values of <0.05 were considered statistically significant. Experimental values are reported as means ± SE.

RESULTS

SAA decreases endothelium-dependent vasorelaxation in porcine coronary arteries.

Endothelial dysfunction plays a crucial role in the development and progression of atherosclerosis. We first tested the effects of SAA on vasomotor functions in porcine coronary arteries by a myograph system including vessel contraction (U-46619), endothelium-dependent (bradykinin) relaxation assays, and endothelium-independent (SNP) relaxation assays. Maximal contraction in response to U-46619 was not different between SAA treatment groups and controls (Fig. 1A and Supplemental Fig. S1). In response to bradykinin at 10−5 M, endothelium-dependent vasorelaxation of the rings was significantly reduced in SAA-treated groups in a concentration-dependent manner (Fig. 1B). At 10 or 25 μg/ml SAA, the endothelium-dependent relaxation was significantly reduced by 12% or 23%, respectively, compared with controls (P < 0.05; Fig. 1B). However, in response to SNP (10−9–10−5 M), endothelium-independent vasorelaxation showed no differences between SAA-treated and control groups (Fig. 1C and Supplemental Fig. S2). Furthermore, we tested the effect of the specific NOS inhibitor l-NAME on vasomotor function of SAA-treated and control rings. After treatment of SAA (10 μg/ml) for 24 h, porcine coronary arteries were preincubated with l-NAME (100 μm) for 30 min. Rings were then precontracted with U-46619 (3 × 10−8 M) and relaxed with bradykinin (10−9–10−5 M). In response to bradykinin at 10−5 M, endothelium-dependent vasorelaxation of SAA-treated or untreated rings was significantly blocked by l-NAME compared with those without l-NAME treatment (P < 0.05; Fig. 1D), indicating a major role of NO in bradykinin-induced vasorelaxation of porcine coronary arteries. However, there were no significant differences of endothelium-dependent vasorelaxation between SAA-treated and untreated groups in the presence of l-NAME, indicating that SAA mainly affects the eNOS system but not prostaglandin and other endothelium-derived hyperpolarizing factors. In addition, endothelium-independent vasorelaxation in response to 10−6 M SNP showed no significant differences between l-NAME-treated and control groups (data not shown).

Fig. 1.

Effect of serum amyloid A (SAA) on vasomotor function in porcine coronary arteries. Porcine coronary arteries were treated with SAA (1, 10, and 25 μg/ml) or with DMSO as a control for 24 h. A: maximal contraction of porcine coronary artery rings in response to U-46619 (3 × 10−8 M). B: precontracted vessels were tested for endothelium-dependent relaxation by adding a series of concentrations of bradykinin (10−9–10−5 M). C: endothelium-independent relaxation in response to sodium nitroprusside (SNP; 10−6 M). n = 11. D: effect of NG-nitro-l-arginine methyl ester (l-NAME) on endothelium-dependent vasorelaxation in response to bradykinin. The SAA (10 μg/ml)-treated vessel ring was treated with l-NAME (100 μm) for 30 min before precontraction with U-46619 started. n = 5. *P < 0.05, control (DMSO) compared with SAA; #P < 0.05 SAA compared with l-NAME or l-NAME + SAA.

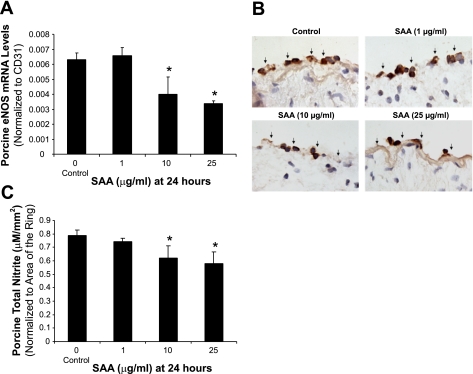

SAA decreases eNOS expression and NO production in porcine coronary arteries and HCAECs.

To investigate whether eNOS could be involved in SAA-induced vasomotor dysfunction in porcine coronary arteries, eNOS expression in both artery rings and HCAECs was analyzed by real-time PCR, immunohistochemistry, and Western blot analysis. Significant decreases of eNOS mRNA levels were observed in a concentration-dependent manner in response to SAA treatment. At 10 or 25 μg/ml SAA, eNOS mRNA levels of arterial rings showed significant decreases by 37% or 47%, respectively, compared with controls (Fig. 2A, P < 0.05). Immunohistochemistry staining also confirmed significant decreases in eNOS protein levels in endothelial layers of porcine arteries (Fig. 2B). Consistent with the effects of SAA on artery rings, both mRNA levels and protein levels of eNOS in HCAECs were significantly reduced with SAA treatment in a concentration-dependent manner (P < 0.05; Fig. 3). When cells were treated with SAA (10 or 25 μg/ml) for 24 h, eNOS mRNA levels were decreased by 23% or 46%, respectively, compared with controls (P < 0.05; Fig. 3A). Moreover, HCAECs were treated with SAA in a time-dependent manner. As shown in Fig. 3B, when cells were cultured with SAA (10 μg/ml) for 6, 24, or 48 h, only 24- and 48-h treatment groups showed a significant reduction of eNOS mRNA levels compared with controls (P < 0.01; Fig. 3B). Furthermore, NO production was analyzed with the nitrite assay kit. NO production was substantially reduced in SAA-treated rings and HCAECs in a concentration-dependent manner. When treated with 10 μg/ml SAA, NO production was decreased by 21.3% and 26.8% in rings and HCAECs, respectively, compared with controls (P < 0.05; Figs. 2C and 3D).

Fig. 2.

Effect of SAA on endothelial nitric oxide (NO) synthase (eNOS) expression and NO release in porcine coronary arteries. Porcine coronary artery rings were cultured with or without SAA for 24 h, and total mRNA was purified from endothelial layers of arterial rings. Porcine eNOS mRNA was measured with real-time PCR. The porcine eNOS mRNA level in each sample was normalized to porcine CD31 to exclude potential molecular contaminations from porcine smooth muscle cells. The relative mRNA level is presented as 2[Ct(CD31) − Ct(eNOS)], where Ct is the threshold cycle. A: SAA significantly decreased eNOS mRNA expression in a concentration-dependent manner compared with controls (n = 3). B: representative slides showing decreased eNOS immunoreactivity in the endothelium of porcine coronary arteries treated with SAA compared with controls. Magnification: ×400. C: NO levels released from vessel rings were determined by measuring the accumulation of its stable degradation products, nitrite and nitrate, using the Griess assay method in culture medium. SAA substantially decreased NO levels compared with controls (n = 4). *P < 0.05, controls (DMSO) compared with SAA.

Fig. 3.

Effect of SAA on eNOS expression and NO release in human coronary artery endothelial cells (HCAECs). HCAECs were treated with SAA in a concentration- and time-dependent manner, and both eNOS mRNA and protein levels were measured with real-time PCR and Western blot analysis, respectively. eNOS mRNA levels in HCAECs were significantly decreased in SAA-treated cells in a concentration-dependent manner (A) and a time-dependent manner (B) compared with controls. Consistent with mRNA levels, SAA treatment also decreased eNOS protein levels in HCAEC (C). n = 3. D: NO release from HCAECs was determined by measuring the accumulation of its stable degradation products, nitrite and nitrate, using the Griess assay method in culture medium. SAA substantially decreased NO release compared with controls (n = 4). *P < 0.05, controls (DMSO) compared with SAA.

Cellular NO production was also demonstrated with the fluorescent dye DAF-FM DA and measured by flow cytometry. DAF-FM DA staining is a unique method to measure NO production in living cells or solutions (24). NO production was significantly reduced in SAA-treated cells in a concentration-dependent manner. SAA at 10 or 25 μg/ml concentration decreased NO-positive cell numbers by 25% or 34%, respectively, compared with controls (P < 0.05; Fig. 4, A and B). In a separate experiment, l-NAME (100 μM) was incubated with HCAECs in the presence of 10 μg/ml SAA. As shown in Fig. 4C, NO production levels in HCAECs were substantially inhibited by l-NAME treatment.

Fig. 4.

Effect of SAA on NO production in HCAECs. SAA-treated HCAECs were stained with the fluorescent dye 4-amino-5-methylamino-2′,7′-difluorofluorescein diacetate (DAF-FM DA) and measured by flow cytometry. A and B: NO production was significantly reduced in SAA-treated HCAECs in a concentration-dependent manner. n = 3. *P < 0.05, controls (DMSO) compared with SAA. C: l-NAME (100 μM) was incubated with HCAECs in the presence of SAA. NO production levels in HCAECs were inhibited by l-NAME treatment.

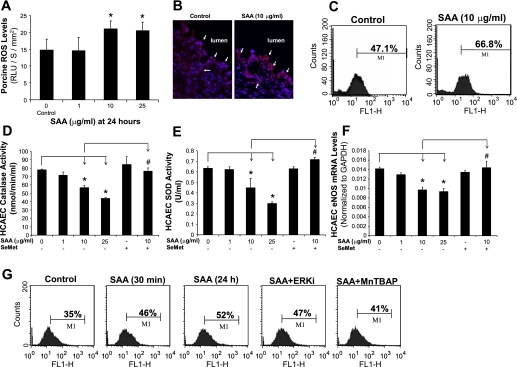

SAA increases ROS production in both porcine coronary arteries and HCAECs.

To investigate whether oxidative stress could play a role in SAA-induced endothelial dysfunction in the vascular system, ROS production from porcine coronary artery rings and HCAECs was analyzed with lucigenin-enhanced chemiluminescence and DHE staining, respectively. ROS levels from artery rings were significantly increased in SAA-treated vessels in a concentration-dependent manner with lucigenin-enhanced chemiluminescence assay. SAA treatment at 10 and 25 μg/ml increased ROS levels from vessel rings by 42% and 39%, respectively, compared with controls (P < 0.05; Fig. 5A). Moreover, differences in ROS levels were also investigated using DHE staining in vessel sections (Fig. 5B). DHE becomes ethidium bromide upon an interaction with ROS and produces red fluorescence when excited. There was a marked increase in red fluorescence in 10 μg/ml SAA-treated samples in both endothelial and smooth muscle layers compared with control samples, which was consistent with results from the lucigenin-enhanced chemiluminescence assay. When HCAECs were cultured with 10 μg/ml SAA for 24 h followed by flow cytometric measurement of DHE staining, ROS levels were substantially increased by 42% compared with controls (Fig. 5C). Furthermore, ROS levels in HCAECs were markedly increased in the early stage of 10 μg/ml SAA treatment (30 min), and the antioxidant MnTBAP (SOD mimetic) effectively blocked the SAA-induced increase in ROS levels (Fig. 5G).

Fig. 5.

Role of SAA-induced oxidative stress on endothelial dysfunction in both porcine coronary arteries and HCAECs. A: ROS levels in the endothelial layer of porcine coronary arteries were tested with lucigenin-enhanced chemiluminescence assay. SAA significantly increased ROS levels of vessel rings in a concentration-dependent manner compared with controls. RLU, relative light units. B: sections of frozen and unfixed porcine coronary artery rings were stained with a fluorescent oxidative dye [dihydroethidium (DHE)] to show ROS levels (red) and counterstained with 4′,6-diamidino-2-phenylindole (blue). ROS staining was increased in SAA-treated vessels in both endothelial and smooth muscle cell layers compared with control vessels. Magnification: ×400. C: ROS levels in HCAECs were stained with DHE and analyzed by FACS Calibur flow cytometry. ROS levels in SAA-treated HCAECs were substantially increased. D and E: activities of both catalase [CAT (D)] and SOD (E) in HCAECs were significantly decreased in SAA-treated cells in a concentration-dependent manner. Coculture with the antioxidant seleno-l-methionine (SeMet) effectively blocked the SAA-induced decrease in activities of both enzymes. F: SeMet effectively prevented the SAA-induced decrease of eNOS mRNA levels in HCAECs. n = 3. G: ROS levels in HCAECs were substantially increased in the early stage of 10 μg/ml SAA treatment (30 min), and the antioxidant Mn(III) tetrakis-(4-benzoic acid)porphyrin [MnTBAP (SOD memetic)] effectively blocked the SAA-induced increase in ROS levels. ERKi, ERK inhibitor. *P < 0.05, controls (DMSO) compared with SAA; #P < 0.05, SAA compared with SeMet + SAA.

SAA decreases activities of CAT and SOD in HCAECs.

Intrinsic antioxidants, including CAT and SOD, are present in the organism to protect it from oxidative stress (35). The activities of CAT and SOD were studied with assay kits (n = 3 for each). Both CAT and SOD activities in HCAECs were significantly decreased in a concentration-dependent manner in response to SAA treatment. SAA (10 and 25 μg/ml) treatment significantly reduced CAT activities in HCAECs by 19% and 37%, respectively, compared with controls (P < 0.05; Fig. 5D). Similarly, SOD activities were also reduced by 30% and 53%, respectively, compared with controls (P < 0.05; Fig. 5E). Coculture with the antioxidant SeMet (20 μM) effectively blocked the SAA-induced decrease of activities of both enzymes to control levels (P < 0.05; Fig. 5, D and E). Furthermore, to evaluate the relationship between oxidative stress and downregulation of eNOS expression, restoring the suppressive effect of SAA on eNOS mRNA levels by antioxidant SeMet was analyzed. As shown in Fig. 5F, SeMet (20 μM) effectively blocked the SAA-induced decrease in eNOS mRNA levels in HCAECs to control levels (P < 0.05).

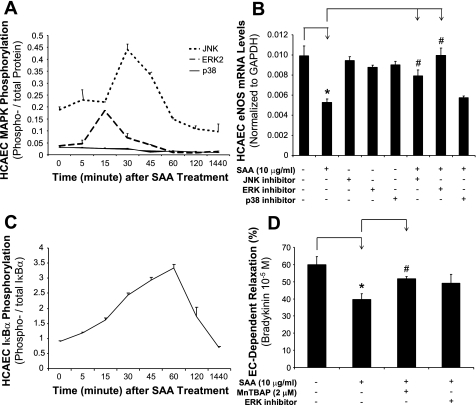

SAA induces phosphorylation of JNK and ERK1/2 as well as IκB-α in HCAECs.

To determine whether MAPKs could be involved in the signal transduction pathways of SAA-induced endothelial dysfunction, the activation status of three major MAPKs (JNK, ERK1/2, and p38) was determined by Bio-Plex immunoassay. Increased phosphorylation of JNK and ERK1/2, but not p38, was observed at 15–30 min after SAA (10 μg/ml) treatment (Fig. 6A). To confirm the functional role of these MAPKs in SAA action, JNK inhibitor (SP-600125, 40 μM), ERK1/2 inhibitor (PD-98059, 40 μM), or p38 inhibitor (SB-239036, 1 μM) was used to pretreat HCAECs for 1 h before SAA (10 μg/ml) treatment for 24 h, and eNOS mRNA levels were determined with real-time PCR. Accordingly, JNK and ERK1/2 inhibitors, but not the p38 inhibitor, effectively blocked the SAA-induced eNOS decrease (n = 3, P < 0.05; Fig. 6B). However, these inhibitors alone did not show any effect on eNOS expression in HCAECs. Moreover, separate experiments showed that JNK and ERK1/2 inhibitors did not have a significant impact on SAA regulating CAT or SOD mRNA levels (Supplemental Fig. S3), indicating that the reduced CAT and SOD activities induced by SAA in HCAECs may be independent to ERK1/2 activation.

Fig. 6.

Effects of SAA on the phosphorylation of MAPKs and IκB-α in HCAECs. HCAECs were treated with SAA (10 μg/ml) for different times. Phosphorylated and total ERK2, JNK, and p38 as well as IκB-α were detected by Bio-Plex immunoassay. A: SAA (10 μg/ml) treatment increased the ratios of phosphorylated and total ERK1/2 and JNK, but not p38, at 15 and 30 min, respectively. B: to confirm the functional role of these MAPKs in SAA action, JNK inhibitor (SP-600125, 40 μM), ERK1/2 inhibitor (PD-98059, 40 μM), or p38 inhibitor (SB-239036, 1 μM) was used to pretreat HCAECs for 1 h before SAA (10 μg/ml) treatment. eNOS mRNA levels were analyzed with real-time PCR. JNK and ERK1/2 inhibitors, but not the p38 inhibitor, effectively blocked the SAA-induced eNOS decrease. C: SAA (10 μg/ml) treatment induced a gradual increase of IκB-α phosphorylation levels starting from 15 min and peaking at 60 min. n = 3. D: blocking effects of MnTBAP (SOD mimetic) or PD-98059 on the SAA (10 μg/ml)-induced decrease in endothelium-dependent relaxation in response to bradykinin (10−5 M). n = 4. *P < 0.05, controls (DMSO) compared with SAA; #P < 0.05, SAA compared with JNK inhibitor + SAA, ERK1/2 inhibitor + SAA, or MnTBAP + SAA.

Additionally, ROS production in HCAECs pretreated with the ERK1/2 inhibitor was determined with DHE staining and flow cytometry analysis. SAA-increased ROS levels in HCAECs were not significantly affected by ERK1/2 inhibitor treatment (Fig. 5G), indicating that SAA-induced ROS production in HCAECs may be upstream of ERK1/2 activation or that SAA-induced ERK1/2 activation and ROS increase may be two parallel events contributing to endothelial dysfunction. Furthermore, to determine the role of ROS and MAPKs in SAA-induced endothelial dysfunction in porcine coronary arteries, the antioxidant MnTBAP (2 μM) or PD-98059 (40 μM) was used to pretreat artery rings followed by SAA (10 μg/ml) treatment for 24 h. As shown in Fig. 6D, in regard to the vasorelaxation in response to bradykinin (10−5 M), SAA significantly reduced endothelium-dependent vasorelaxation by 34% compared with untreated control rings (P < 0.05, n = 4). Coculture of the antioxidant MnTBAP and SAA significantly increased the vasorelaxtion by 31% compared with SAA-treated vessels (n = 4, P < 0.05). Coculture of the ERK inhibitor and SAA also increased vasorelaxation by 24% compared with SAA-treated vessels; however, it did not reach a statistical difference (P = 0.065). Thus, both MnTBAP and the ERK1/2 inhibitor partially blocked the SAA-induced decrease in endothelium-dependent vasorelaxation in response to bradykinin in porcine coronary arteries, indicating that oxidative stress and ERK1/2 activation are involved in SAA-induced endothelial dysfunction. However, the maximal contraction and endothelium-independent vasorelaxation were not significantly different among these treatment groups (data not shown).

In most resting cells, the transcription factor NF-κB is sequestered in the cytoplasm in an inactive form associated with inhibitory molecules such as IκB-α. The phosphorylation status of IκB-α can release the inhibition of NF-κB, thereby activating NF-κB (34). After SAA (10 μg/ml) treatment, we observed a gradual increase of IκB-α phosphorylation levels, starting from 15 min and peaking at 60 min (Fig. 6C). These data suggest that SAA may activate NF-κB.

DISCUSSION

It is not fully understood whether SAA can mediate cardiovascular pathogenesis, although its levels are associated with cardiovascular disease. The present study provides direct evidence for biological functions of SAA in the vascular system. We demonstrated a potential mechanism by which SAA causes endothelial dysfunction of porcine coronary arteries and HCAECs. SAA increases ROS production, decreases eNOS expression, and activates JNK and ERK1/2 MAPKs, which may function as signal transduction pathways for SAA's action in endothelial cells. SAA could serve as a potential therapeutic target in patients with a high risk for cardiovascular disease.

Clinically, plasma levels of SAA can be determined by several techniques such as ELISA, radioimmunoassays, nephelometric assays, and dissociation-enhanced lanthanide fluorescence immunoassay. The sensitivity of these detection methods is different, and thereby plasma levels of SAA are variable among different reports due to the different methods used. In general, the plasma level of SAA in a healthy population without evidence of acute inflammation is ∼2–4 μg/ml or less. However, plasma SAA levels can increase from 100 to 1,000 μg/ml in response to inflammation, viral or bacterial infections, neoplasia, and vasculitis (19, 32, 44, 47). Plasma SAA levels were significantly higher in patients with severe atherosclerosis than in normal individuals (11, 22, 32). For example, Johnson et at. (21) reported that a total of 705 women with confirmed coronary artery diseases had mean plasma SAA levels of 17.9 μg/ml (ranging from 0.2 to 731 μg/ml), and higher levels of plasma SAA were positively associated with the severity of cardiovascular disease and with the risk of cardiovascular events. Thus, the three major concentrations (1, 10, and 25 μg/ml) of SAA used in the present study are clinically relevant.

Endothelial dysfunction is a characteristic aspect of atherosclerosis and is commonly found as an early feature in atherothrombotic vascular disease. One of the important characteristics of endothelial dysfunction is the impaired synthesis, release, and activity of endothelium-derived NO. In normal endothelial cells, the amino acid l-arginine is constitutively converted to l-citrulline and NO by eNOS (2). The eNOS/NO system is one of the most important components in the endogenous defense against vascular injury, inflammation, and thrombosis. Inhibition of eNOS accelerated atherosclerosis in experimental animals (9). An impairment of endothelium-dependent vasorelaxation is present in atherosclerotic vessels even before vascular structural changes occur and represents reduced eNOS-derived NO activity (23). Many cardiovascular risk factors can directly reduce eNOS expression at transcriptional and/or posttranscriptional levels. For example, tetrahydrobiopterin (BH4) is a critical coenzyme of eNOS. When BH4 availability is reduced, eNOS decreases NO production, whereas it increases superoxide anion production. This process is termed “eNOS uncoupling” (45). In addition, TNF-α could reduce eNOS mRNA stability through potential mechanisms of unknown cytoplasmic proteins binding to eNOS mRNA 3′-untranslated region (UTR) sequences (1, 25, 43). More recently, we have shown that sCD40L also decreased eNOS mRNA stability, and unknown cytoplasmic molecules were able to bind to the eNOS mRNA 3′-UTR in sCD40L-treated HCAECs (12). Furthermore, we performed a 95-micro-RNA (mi)RNA profiling experiment in HCAECs treated with sCD40L or TNF-α for 24 h. sCD40L or TNF-α treatment induced a specific expression pattern of 95 miRNAs, which may be able to regulate eNOS mRNA translation or stability. For examples, we found that sCD40L and TNF-α could increase miR-221 levels by 38% and 47%, respectively (12). miR-221 may have functions to regulate eNOS levels (46). However, it is not clear whether SAA is able to regulate eNOS expression at transcriptional and/or posttranslational levels in endothelial cells.

The present study shows that SAA impairs endothelium-dependent relaxation of porcine coronary arteries and downregulates eNOS expression in both porcine arteries and HCAECs, indicating that SAA causes endothelial dysfunction via damaging the NO/eNOS system. Moreover, we found that endothelium-dependent vasorelaxation of either SAA-treated or untreated rings was significantly blocked by l-NAME. Removal of NO by l-NAME reduced vasorelaxation in response to bradykinin in both SAA-treated and untreated rings. These data suggest that SAA-induced endothelial dysfunction is mainly through inhibition of NO production.

ROS are key mediators for vascular inflammation and atherogenesis via a variety of mechanisms, including a state of continuous NO consumption and depletion, intracellular alkalinization, and regulation of gene transcription (49). In the present study, we found SAA induced a substantial increase of ROS in both porcine coronary artery rings and HCAECs. However, specific mechanisms of SAA-induced ROS production are not well understood. Several enzymatic systems contribute to ROS production in vascular endothelial cells, including NA(D)PH oxidase, xanthine oxidase, uncoupled eNOS, and the mitochondrial electron transport chain (16, 49). NADPH oxidase is one of the best characterized ROS-generating enzymes in inflammation and in vascular cells. It has been reported that SAA is able to induce the activation of neutrophil NADPH oxidase with a resulting release of ROS (6). Our previous study (48) has indicated that C-reactive protein, an acute inflammatory protein, increased ROS production in macrophage-derived foam cells, which may result from mitochondrial dysfunction and upregulation of NADPH oxidase. In addition, decreased levels and/or activities of internal antioxidant enzymes such as SOD and CAT may induce a increase of ROS. SOD facilitates the formation of H2O2 from superoxide anion, whereas CAT catalyzes the reaction of H2O2 to water (16).

Although endothelial dysfunction is a multifactorial process, there is evidence to support that increased vascular ROS production is likely to be an important step since superoxide reacts rapidly with NO, resulting in the formation of peroxynitrite anion and loss of bioactivity of NO (30). ROS may promote the oxidative degradation of BH4, leading to the decreased production of NO (8). The present study demonstrates that SAA significantly increased ROS production in porcine coronary arteries and HCAECs, whereas it decreased both CAT and SOD activities simultaneously in HCAECs. SAA-induced decreases in CAT and SOD activities may be responsible for the oxidative stress and reduction of NO bioavailability, thereby attributing to endothelial dysfunction. SAA stimulates TNF-α secretion from human T lymphocytes by forming a SAA-extracellular matrix complex (37), and TNF-α can induce oxidative stress (17). SAA at high concentrations (50 and 100 μg/ml) can stimulate neutrophil superoxide anion production (15). NO bioavailability is mainly dependent on NO production by eNOS and the presence of ROS. A decreased level of eNOS could directly reduce NO production. Decreased levels of CAT and SOD could increase the accumulation of ROS, which readily interact with NO to form peroxynitrite (13), thereby reducing NO bioavailability. Increased ROS could also inhibit eNOS expression and activity (40). Thus, it is possible that there may be a synergistic effect between the loss of eNOS and loss of CAT and SOD reducing NO bioavailability in response to SAA.

In addition to the detrimental effects of ROS, multiple studies have demonstrated that elevated ROS could play a role in various signaling pathways, among which are MAPKs, including ERK, JNK, and p38. MAPKs can be activated by a wide variety of stimuli, such as inflammation, growth factors, and ROS. For example, ROS modulates the cardiomyocyte response to ischemia-reperfusion through MAPK activation (33). ROS scavengers inhibited the activities of ERK1/2 and p38 in alveolar epithelial cells (53, 54). It is possible that MAPK is involved in the onset of ROS production because MAPK activation precedes ROS production. However, recent evidence has indicated that ROS production is induced by a mechanism independent of the activation of MAPKs (41). In the present study, we demonstrated that the SAA-induced ROS increase in HCAECs is not significantly affected by treatment of the ERK1/2 inhibitor, although SAA can activate ERK1/2. The reason for this observation is clear, and we speculate that SAA-induced ROS production in HCAECs may be the upstream of ERK1/2 activation or that the SAA-induced ERK1/2 activation and ROS increase may be two parallel events contributing to endothelial dysfunction. This interesting relationship between ROS and MAPK activation in SAA-treated vessels or cells warrants further investigation.

ROS may mediate the activation of MAPKs in a variety of cells, leading to the activation of transcription factors such as NF-κB, attributing to changes in gene expressions (39, 52). ROS have been implicated in initiating inflammatory responses in the lungs through the activation of transcription factors such as NF-κB, causing chromatin remodeling and gene expression of proinflammatory mediators (38). MAPK pathways have been involved in regulating these transcription factors. SAA has been found to activate MAPKs such as ERK1/2 and p38 in both HeLa and THP-1 cells in a CD36 and LIMPII analogous-1-dependent manner (5). SAA activates NF-κB and proinflammatory gene expression in human and murine intestinal epithelial cells (20). A recent study (55) has indicated that SAA rapidly induces the expression and activity of tissue factor and that the effects were mediated through the activation of MAPK and NF-κB. In the present study, increased phosphorylation of JNK, ERK1/2, and IκB-α was observed in SAA-treated HCAECs, and JNK and ERK1/2 inhibitors effectively blocked the SAA-induced eNOS decrease, indicating that the signal pathways of JNK and ERK1/2 as well as NF-κB may be involved in SAA's action in endothelial cells.

In summary, the present study shows that SAA induces endothelial dysfunction of porcine coronary artery endothelial cells and HCAECs via increasing ROS production, decreasing eNOS expression, inhibiting CAT and SOD activities, and activating JNK and ERK1/2 MAPKs. Antioxidants or the EKR1/2 inhibitor effectively blocked the SAA-induced eNOS decrease, indicating that inhibition of oxidative stress and MAPK activation may have the potential to block SAA-induced endothelial dysfunction.

GRANTS

This work was partially supported by National Institutes of Health Research Grants HL-076345 (to P. H. Lin), DE-15543 (to Q. Yao), AT-003094 (to Q. Yao), EB-002436 (to C. Chen), and HL-083471 (to C. Chen) as well as by the Michael E. DeBakey Department of Surgery, Baylor College of Medicine, and Michael E. DeBakey Veterans Affairs Medical Center (Houston, TX).

Acknowledgments

Authors thank Dr. Esteban A. Henao for technical assistance.

The costs of publication of this article were defrayed in part by the payment of page charges. The article must therefore be hereby marked “advertisement” in accordance with 18 U.S.C. Section 1734 solely to indicate this fact.

Footnotes

Supplemental material for this article is available online at the American Journal of Physiology-Heart and Circulatory Physiology website.

REFERENCES

- 1.Alonso J, Sánchez de Miguel L, Montón M, Casado S, López-Farré A. Endothelial cytosolic proteins bind to the 3′ untranslated region of endothelial nitric oxide synthase mRNA: regulation by tumor necrosis factor alpha. Mol Cell Biol 17: 5719–5726, 1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Arnal JF, Dinh-Xuan AT, Pueyo M, Darblade B, Rami J. Endothelium-derived nitric oxide and vascular physiology and pathology. Cell Mol Life Sci 55: 1078–1087, 1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Artl A, Marsche G, Pussinen P, Knipping G, Sattler W, Malle E. Impaired capacity of acute-phase high density lipoprotein particles to deliver cholesteryl ester to the human HUH-7 hepatoma cell line. Int J Biochem Cell Biol 34: 370–381, 2002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Badolato R, Wang JM, Stornello SL, Ponzi AN, Duse M, Musso T. Serum amyloid A is an activator of PMN antimicrobial functions: induction of degranulation, phagocytosis, and enhancement of anti-Candida activity. J Leukoc Biol 67: 381–386, 2000. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Baranova IN, Vishnyakova TG, Bocharov AV, Kurlander R, Chen Z, Kimelman ML, Remaley AT, Csako G, Thomas F, Eggerman TL, Patterson AP. Serum amyloid A binding to CLA-1 (CD36 and LIMPII analogous-1) mediates serum amyloid A protein-induced activation of ERK1/2 and p38 mitogen-activated protein kinases. J Biol Chem 280: 8031–8040, 2005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Björkman L, Karlsson J, Karlsson A, Rabiet MJ, Boulay F, Fu H, Bylund J, Dahlgren C. Serum amyloid A mediates human neutrophil production of reactive oxygen species through a receptor independent of formyl peptide receptor like-1. J Leukoc Biol 83: 245–253, 2008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Bredt DS Endogenous nitric oxide synthesis: biological functions and pathophysiology. Free Radic Res 31: 577–596, 1999. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Cai H, Harrison DG. Endothelial dysfunction in cardiovascular diseases: the role of oxidant stress. Circ Res 87: 840–844, 2000. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Cayatte AJ, Palacino JJ, Horten K, Cohen RA. Chronic inhibition of nitric oxide production accelerates neointima formation and impairs endothelial function in hypercholesterolemic rabbits. Arterioscler Thromb 14: 753–759, 1994. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Chai H, Yang H, Yan S, Li M, Lin PH, Lumsden AB, Yao Q, Chen C. Effects of 5 HIV protease inhibitors on vasomotor function and superoxide anion production in porcine coronary arteries. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr Hum Retrovirol 40: 12–19, 2005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Chait A, Han CY, Oram JF, Heinecke JW. Thematic review series: the immune system and atherogenesis. Lipoprotein-associated inflammatory proteins: markers or mediators of cardiovascular disease? J Lipid Res 46: 389–403, 2005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Chen C, Chai H, Wang X, Jiang J, Jamaluddin MS, Liao D, Zhang Y, Wang H, Bharadwaj U, Zhang S, Li M, Lin P, Yao Q. Soluble CD40 ligand induces endothelial dysfunction in human and porcine coronary artery endothelial cells. Blood 112: 3205–3216, 2008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Cominacini L, Rigoni A, Pasini AF, Garbin U, Davoli A, Campagnola M, Pastorino AM, Lo Cascio V, Sawamura T. The binding of oxidized low density lipoprotein (ox-LDL) to ox-LDL receptor-1 reduces the intracellular concentration of nitric oxide in endothelial cells through an increased production of superoxide. J Biol Chem 276: 13750–13755, 2001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Drummond GR, Cai H, Davis ME, Ramasamy S, Harrison DG. Transcriptional and posttranscriptional regulation of endothelial nitric oxide synthase expression by hydrogen peroxide. Circ Res 86: 347–354, 2000. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Gatt ME, Urieli-Shoval S, Preciado-Patt L, Fridkin M, Calco S, Azar Y, Matzner Y. Effect of serum amyloid A on selected in vitro functions of isolated human neutrophils. J Lab Clin Med 132: 414–420, 1998. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Giordano FJ Oxygen, oxidative stress, hypoxia, and heart failure. J Clin Invest 115: 500–508, 2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Gloire G, Legrand-Poels S, Piette J. NF-kappaB activation by reactive oxygen species: fifteen years later. Biochem Pharmacol 72: 1493–1505, 2006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Harrison D, Griendling KK, Landmesser U, Hornig B, Drexler H. Role of oxidative stress in atherosclerosis. Am J Cardiol 91: 7A–11A, 2003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Hoffmeister A, Rothenbacher D, Bäzner U, Fröhlich M, Brenner H, Hombach V, Koenig W. Role of novel markers of inflammation in patients with stable coronary heart disease. Am J Cardiol 87: 262–266, 2001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Jijon HB, Madsen KL, Walker JW, Allard B, Jobin C. Serum amyloid A activates NF-kappaB and proinflammatory gene expression in human and murine intestinal epithelial cells. Eur J Immunol 35: 718–726, 2005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Johnson BD, Kip KE, Marroquin OC, Arant CB, Wessel TR, Olson MB, Johnson BD, Mulukutla S, Sopko G, Merz CN, Reis SE. Serum amyloid A as a predictor of coronary artery disease and cardiovascular outcome in women: the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute-Sponsored Women's Ischemia Syndrome Evaluation (WISE). Circulation 109: 726–732, 2004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Jousilahti P, Salomaa V, Rasi V, Vahtera E, Palosuo T. The association of c-reactive protein, serum amyloid a and fibrinogen with prevalent coronary heart disease–baseline findings of the PAIS project. Atherosclerosis 156: 451–456, 2001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kawashima S The two faces of endothelial nitric oxide synthase in the pathophysiology of atherosclerosis. Endothelium 11: 99–107, 2004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kojima H, Urano Y, Kikuchi K, Higuchi T, Hirata Y, Nagano T. Fluorescent indicators for imaging nitric oxide production. Angew Chem Int Ed Engl 38: 3209–3212, 1999. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Lai PF, Mohamed F, Monge JC, Stewart DJ. Downregulation of eNOS mRNA expression by TNF-α: identification and functional characterization of RNA-protein interactions in the 3′UTR. Cardiovasc Res 59: 160–168, 2003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Leinonen E, Hurt-Camejo E, Wiklund O, Hultén LM, Hiukka A, Taskinen MR. Insulin resistance and adiposity correlate with acute-phase reaction and soluble cell adhesion molecules in type 2 diabetes. Atherosclerosis 166: 387–394, 2003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Lewis KE, Kirk EA, McDonald TO, Wang S, Wight TN, O'Brien KD, Chait A. Increase in serum amyloid a evoked by dietary cholesterol is associated with increased atherosclerosis in mice. Circulation 110: 540–545, 2004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Liang JS, Schreiber BM, Salmona M, Phillip G, Gonnerman WA, de Beer FC, Sipe JD. Amino terminal region of acute phase, but not constitutive, serum amyloid A (apoSAA) specifically binds and transports cholesterol into aortic smooth muscle and HepG2 cells. J Lipid Res 37: 2109–2116, 1996. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Libby P, Ridker PM, Maseri A. Inflammation and atherosclerosis. Circulation 105: 1135–1143, 2002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Mahmoudi M, Curzen N, Gallagher PJ. Atherogenesis: the role of inflammation and infection. Histopathology 50: 535–546, 2007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Manley PN, Ancsin JB, Kisilevsky R. Rapid recycling of cholesterol: the joint biologic role of C-reactive protein and serum amyloid A. Med Hypotheses 66: 784–792, 2006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Mezaki T, Matsubara T, Hori T, Higuchi K, Nakamura A, Nakagawa I, Imai S, Ozaki K, Tsuchida K, Nasuno A, Tanaka T, Kubota K, Nakano M, Miida T, Aizawa Y. Plasma levels of soluble thrombomodulin, C-reactive protein, and serum amyloid A protein in the atherosclerotic coronary circulation. Jpn Heart J 44: 601–612, 2003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Michel MC, Li Y, Heusch G. Mitogen-activated protein kinases in the heart. Naunyn Schmiedebergs Arch Pharmacol 363: 245–266, 2001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Monaco C, Paleolog E. Nuclear factor kappaB: a potential therapeutic target in atherosclerosis and thrombosis. Cardiovasc Res 61: 671–682, 2004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Muzykantov VR Targeting of superoxide dismutase and catalase to vascular endothelium. J Control Release 71: 1–21, 2001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Quyyumi AA Endothelial function in health and disease: new insights into the genesis of cardiovascular disease. Am J Med 105: 32S–39S, 1998. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Preciado-Patt L, Pras M, Fridkin M. Binding of human serum amyloid A (hSAA) and its high-density lipoprotein3 complex (hSAA-HDL3) to human neutrophils. Possible implication to the function of a protein of an unknown physiological role. Int J Pept Protein Res 48: 503–513, 1996. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Rahman I, MacNee W. Role of transcription factors in inflammatory lung diseases. Thorax 53: 601–612, 1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Rahman I, Marwick J, Kirkham P. Redox modulation of chromatin remodeling: impact on histone acetylation and deacetylation, NF-kappaB and pro-inflammatory gene expression. Biochem Pharmacol 68: 1255–1267, 2004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Ramet ME, Ramet M, Lu Q, Nickerson M, Savolainen MJ, Malzone A, Karas RH. High-density lipoprotein increases the abundance of eNOS protein in human vascular endothelial cells by increasing its half-life. J Am Coll Cardiol 41: 2288–2297, 2003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Romeis T, Piedras P, Zhang S, Klessig DF, Hirt H, Jones JD. Rapid Avr9- and Cf-9-dependent activation of MAP kinases in tobacco cell cultures and leaves: convergence of resistance gene, elicitor, wound, and salicylate responses. Plant Cell 11: 273–287, 1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Rush JW, Denniss SG, Graham DA. Vascular nitric oxide and oxidative stress: determinants of endothelial adaptations to cardiovascular disease and to physical activity. Can J Appl Physiol 30: 442–474, 2005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Searles CD, Miwa Y, Harrison DG, Ramasamy S. Posttranscriptional regulation of endothelial nitric oxide synthase during cell growth. Circ Res 85: 588–595, 1999. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Sodin-Semrl S, Zigon P, Cucnik S, Kveder T, Blinc A, Tomsic M, Rozman B. Serum amyloid A in autoimmune thrombosis. Autoimmun Rev 6: 21–27, 2006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Stuehr D, Pou S, Rosen GM. Oxygen reduction by nitric-oxide synthases. J Biol Chem 276: 14533–14536, 2001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Suárez Y, Fernández-Hernando C, Pober JS, Sessa WC. Dicer dependent microRNAs regulate gene expression and functions in human endothelial cells. Circ Res 100: 1164–1173, 2007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Uhlar CM, Whitehead AS. Serum amyloid A, the major vertebrate acute-phase reactant. Eur J Biochem 265: 501–523, 1999. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Wang X, Liao D, Bharadwaj U, Li M, Yao Q, Chen C. C-reactive protein inhibits cholesterol efflux from human macrophage-derived foam cells. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol 28: 519–526, 2008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Wassmann S, Wassmann K, Nickenig G. Modulation of oxidant and antioxidant enzyme expression and function in vascular cells. Hypertension 44: 381–386, 2004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Wong M, Toh L, Wilson A, Rowley K, Karshimkus C, Prior D, Romas E, Clemens L, Dragicevic G, Harianto H, Wicks I, McColl G, Best J, Jenkins A. Reduced arterial elasticity in rheumatoid arthritis and the relationship to vascular disease risk factors and inflammation. Arthritis Rheum 48: 81–89, 2003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Yang Z, Ming XF. Recent advances in understanding endothelial dysfunction in atherosclerosis. Clin Med Res 4: 53–65, 2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Yoshizumi M, Tsuchiya K, Tamaki T. Signal transduction of reactive oxygen species and mitogen-activated protein kinases in cardiovascular disease. J Med Invest 48: 11–24, 2001. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Zhang GX, Lu XM, Kimura S, Nishiyama A. Role of mitochondria in angiotensin II-induced reactive oxygen species and mitogen-activated protein kinase activation. Cardiovasc Res 76: 204–212, 2007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Zhang Z, Leonard SS, Huang C, Vallyathan V, Castranova V, Shi X. Role of reactive oxygen species and MAPKs in vanadate-induced G2/M phase arrest. Free Radic Biol Med 34: 101333–101342, 2003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Zhao Y, Zhou S, Heng CK. Impact of serum amyloid A on tissue factor and tissue factor pathway inhibitor expression and activity in endothelial cells. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol 27: 1645–1650, 2007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]