Abstract

We have reported previously that telomeres (ends of chromosomes consisting of highly conserved TTAGGG repeats) were shorter in metaphase and interphase preparations in T lymphocytes from short-term whole blood cultures of women with Down syndrome (DS) and dementia compared to age-matched women with DS but without dementia (Jenkins et al., 2006). Our previous study was carried out by measuring changes in fluorescence intensity [using an FITC-labeled peptide nucleic acid (PNA) probe (Applied Biosystems; DAKO) and Applied Imaging software], and we now report on a substantially simpler metric, counts of signals at the ends of chromosomes. Nine adults with DS and dementia plus four who are exhibiting declines in cognition analogous to mild cognitive impairment in the general population (MCI-DS) were compared to their pair-matched peers with DS but without dementia or MCI-DS. Results indicated that the number of chromosome ends that failed to exhibit fluorescent signal from the PNA telomere probe was higher for people with dementia or mild cognitive impairment (MCI-DS). Thus, a simple count of chromosome ends for the “presence/absence” of fluorescence may provide a valid biomarker of dementia status. If this is the case, then after additional research for validation to assure high specificity and sensitivity, the test may be used to identify and ultimately guide treatment for people at increased risk for developing mild cognitive impairment and/or dementia.

Keywords: Telomere number, Down syndrome, Alzheimer’s disease, Mild cognitive impairment

Introduction

Telomeres are chromosome ends that consist of highly conserved TTAGGG repeats and become shorter with every cell division. Increased telomere shortening has been associated with a variety of conditions including apoptosis and replicative cellular senescence (Allsopp et al., 1992; Hao et al., 2004), neoplastic transformation (Plentz et al., 2004), in vivo cellular aging (Hastie et al., 1990; Lindsey et al., 1991; Ahmed et al., 2001; Flanary et al., 2003), heart disease (Samani et al., 2001; Benetos et al., 2004), stress (Epel et al., 2004; Damjanovic et al., 2007), osteoporosis (Valdes et al., 2007), obesity (Valdes et al., 2005), dyskeratosis congenita (Vulliamy and Dokal, 2007), and Alzheimer’s disease (AD) (Panossian et al., 2003). The recent finding on UUAGGG-repeat telomeric RNAs may provide better understanding of the role of the telomere in the above conditions (Schoeftner and Blasco, 2007).

We have previously observed quantitatively reduced telomere size in metaphase and interphase preparations from short-term whole blood cultures of adults with DS and dementia compared to age-matched adults with DS and no dementia (Jenkins et al., 2006; Jenkins et al, 2008). In addition we have broadened our original study to show that telomere length is also shortened for people with DS who exhibited cognitive declines analogous to mild cognitive impairment (MCI) in the general population, referred to as MCI-DS in the present study. MCI is defined as an intermediate stage between cognitive declines typical of brain aging, per se, and the deficits that occur with dementia, during which daily living activities are generally unaffected (e.g, Gauthier et al., 2006; Winblad et al., 2004; Petersen et al., 1999). Declines observed are not sufficiently severe to meet criteria diagnostic for dementia (Petersen et al., 1999). Individuals with MCI are more likely to convert to dementia than peers without MCI (Petersen et al., 1999), especially those with memory function decline. Similar to dementia diagnosis, MCI identification in adults with DS is complicated by lifelong cognitive deficits and substantial inter-individual variability in baseline abilities. However, longitudinal assessments of cognition can be used to characterize changes suggestive of MCI within this population, and that was the procedure employed in this study (see Devenny et al., 2000; Krinsky-McHale et al, in press; Zigman et al., 2004).

Quantitative measurement of telomere length requires the use of sophisticated and specialized methods and equipment. Therefore, we wanted to determine if a simpler metric could distinguish adults with dementia or MCI-DS from their unaffected peers with DS. For this purpose, we chose counts of signals (present/absent) from fluorescently tagged chromosome ends (employing an FITC-labeled peptide nucleic acid probe).

Materials and Methods

Human Subjects

Adult subjects with DS were recruited using an Institutional Review Board-approved protocol with correspondent-informed consent and participant assent. A community-based sample of 234 women with DS, 45–78 years of age, and 124 men from 45–73 years of age, was obtained through the New York State Developmental Disability Service System or direct contacts with provider agencies in neighboring states. These people have been participating in a longitudinal study examining changes in functioning associated with aging and dementia in adults with intellectual disability and have been evaluated at 14–18 month intervals to determine cognitive, functional and health status (see e.g., Silverman et al., 2004). From this larger sample, 11 pairs of females, as well as two pairs of males (all with complete trisomy 21) were age-matched, one individual within each pair having dementia or MCI-DS and the other not. Samples from females have been more available than males because of an ongoing project focused on women’s health (Schupf et al., 2003). Table 1 indicates the age, sex and dementia status of individuals within our sample.

Table 1.

The mean number of chromosome arms with no signal (MNCANS) for studies 1 – 13 showing greater loss of signal associated with dementia and MCI-DS among 26 people with DS.

| Study | Sex | Age | Dementia Status1 | MNCANS | P |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | F | 58.3 | PD | 19.0 (7.3)2 | |

| 1 | F | 60.3 | ND | 11.0 (7.2) | <.002 |

| 2 | F | 53.8 | DD | 13.1 (5.5) | |

| 2 | F | 57 | ND | 7.7 (5.6) | <.004 |

| 3 | F | 58.8 | PD | 13.1 (6.0) | |

| 3 | F | 60.6 | ND | 7.3 (4.1) | <.001 |

| 4 | M | 62.5 | DD | 9.4 (4.8) | |

| 4 | M | 63.2 | ND | 5.2 (3.9) | <.004 |

| 5 | M | 58 | PD | 13.0 (5.7) | |

| 5 | M | 64.5 | ND | 4.2 (3.0) | <.000001 |

| 6 | F | 59 | DD | 16.4 (7.1) | |

| 6 | F | 65.4 | ND | 5.6 (3.7) | <.000001 |

| 7 | F | 66.9 | PD | 18.3 (6.1) | |

| 7 | F | 69.8 | ND | 6.6 (3.7) | <.000000 |

| 8 | F | 57 | DD | 10.3 (4.4) | |

| 8 | F | 58 | ND | 4.3 (2.3) | <.000004 |

| 9 | F | 55.8 | DD | 16.2 (9.7) | |

| 9 | F | 57.8 | ND | 3.9 (4.1) | <.000007 |

| 10 | F | 49.8 | MCI | 8.6 (5.2) | |

| 10 | F | 50.2 | ND | 8.0 (4.2) | <.7 |

| 11 | F | 54.2 | MCI | 9.1 (6.0) | |

| 11 | F | 54.6 | ND | 6.1 (5.1) | <.1 |

| 12 | F | 51.5 | MCI | 12.0 (3.5) | |

| 12 | F | 53 | ND | 5.9 (2.7) | <.000000 |

| 13 | F | 53 | MCI | 10.0 (3.7) | |

| 13 | F | 53.3 | ND | 4.2 (2.8) | <.000004 |

DD, PD, ND, MCI = definite dementia, probable dementia, no dementia, and mild cognitive impairment, respectively

19.0 (7.3) = mean number of signals lost with a standard deviation of 7.3.

Dementia Status

The dementia status of each participant was determined at a consensus conference which included all senior staff members participating in our longitudinal assessments and research assistants who had direct contact with the participants under consideration (Silverman et al., 2004; Zigman et al., 2004). Participants were classified based upon consideration of information available from a detailed review of clinical records, informant interviews, and direct assessments of selected cognitive functions, including evidence of decline over the 14- to 20-month period between assessments. Dementia status was classified consistent with diagnostic guidelines recommended by the AAMR-IASSID Working Group for the Establishment of the Criteria for the Diagnosis of Dementia in Individuals with Developmental Disability (Aylward et al., 1997; Burt & Aylward, 2000), that were based upon current ICD-10 criteria (WHO, 1992). Each case was classified as: (a) non-demented, indicating with reasonable certainty that significant age-associated impairment was absent; (b) MCI-DS status, indicating that there was substantial uncertainty regarding dementia status, with some indication of mild cognitive and/or functional decline but importantly, the observed change(s) did not meet dementia criteria; (c) possible dementia, indicating that some signs and symptoms of dementia were present, but declines over time were not judged to be totally convincing, although there was more certainty than for the MCI-DS status classification; (d) definite dementia, indicating with reasonable confidence that dementia was present based upon substantial decline over time and absence of other conditions that might mimic dementia (e.g., untreated hypothyroidism). For each participant who was rated as having possible or definite dementia, findings were reviewed to establish a differential diagnosis. These were either AD or AD in combination with possible other cause(s) (e.g., Parkinson’s disease) given the substantial AD neuropathology characteristic of DS at these ages. Participants could also be categorized as (e) status uncertain due to complications, indicating that the criteria for possible dementia had been met, but symptoms might be caused by some other substantial concern, usually a medical condition unrelated to a dementing disorder (e.g., severe sensory loss, poorly resolved hip fracture, psychiatric diagnosis), and (f) indeterminable, indicating that the preexisting disability was of such severity that detection of decline indicative of dementia was not possible (e.g., profound ID with multiple handicaps). Participants in these latter two categories were not included in the present study.

Telomere Analysis

Telomeres in metaphase spreads (T-lymphocytes from freshly collected whole blood) were hybridized using an FITC-labeled peptide nucleic acid (PNA) probe and DAPI counterstaining (Jenkins et al., 2006). The actual number of fluorescent signals for each metaphase was determined by simply counting the signal number per metaphase and tabulating the number of chromosome arms that did not exhibit an FITC signal for each participant.

Results

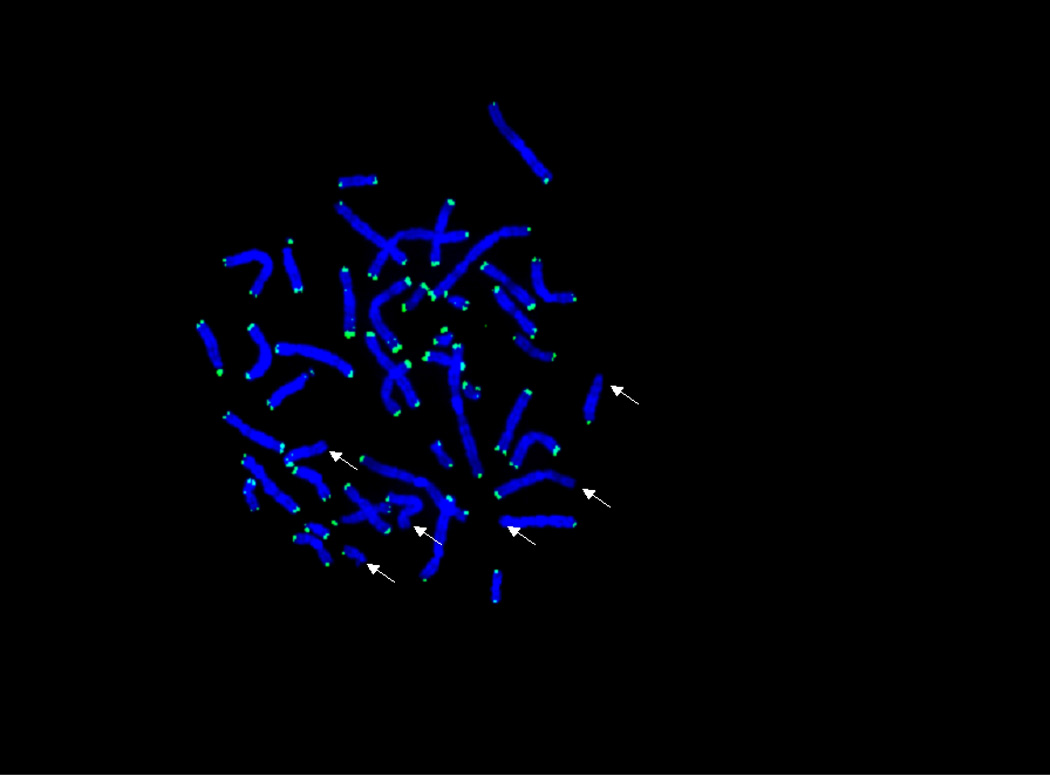

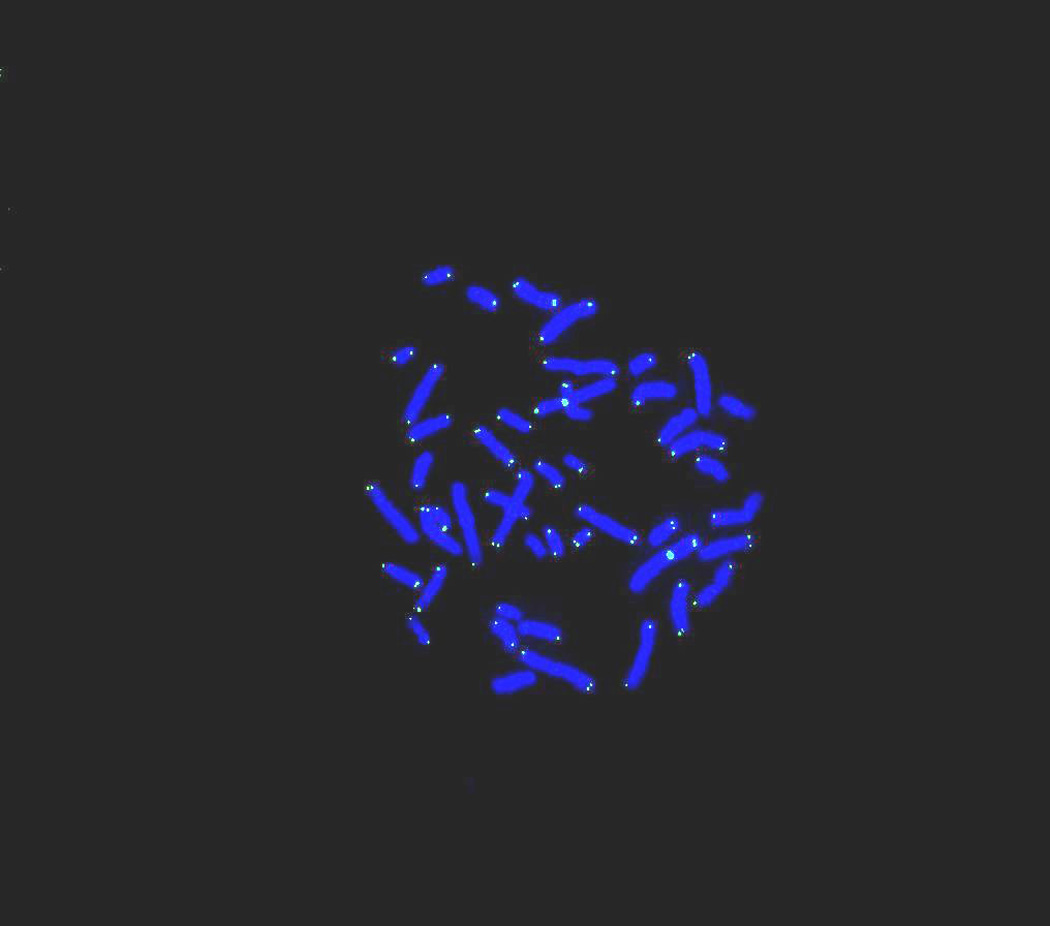

Figure 1 shows an image of a metaphase from a short-term whole blood culture, hybridized with an FITC-labeled PNA probe such that telomeres are labeled at most metaphase chromosome ends and within the interphase nucleus. The results of within-pair comparisons of the number of chromosome arms with no fluorescent signal are given in Table 1.

Fig. 1.

Fig. 1a: Telomeres in metaphase shown by an FITC-labeled PNA probe with DAPI counterstaining. Examples of chromosome arms with no signal are shown by arrows. This cell was obtained from a whole blood culture of a person with Down syndrome with no dementia/MCI.

Fig. 1b: Similar to Fig. 1a except there are more signals (over 20) missing from this metaphase obtained from a whole blood culture of a person with MCI-DS.

Results, summarized in Table 1, were generated by counting the number of chromosome arms with no “visible” telomeres in each of 20 metaphase cells per subject. Overall, the distributions of scores for individuals with dementia or MCI-DS versus their non-demented peers had almost no overlap, t (12) = 7.18, p < .00003. In fact, all individuals with dementia or MCI-DS had means of over 8 missing signals while that was true for only a single non-demented individual. The difference between affected and unaffected individuals was also significant for pairings with just demented cases or just MCI-DS cases, t (8) = 8.19, p<.0005 and t(3) = 2.99, p<.03 (1-tailed), respectively, but a mixed model analysis of variance (with diagnosis as a between subjects variable and affected/unaffected as a within subjects variable) indicated that signal loss was greater in cases with dementia compared to MCI-DS, F(1,11) = 6.02, p<.032 (see Figure 2).

Fig. 2.

Telomere Fluorescent Signal Loss: Interaction showing greater effect with dementia compared to MCI-DS. Interaction effect: F(1, 11)=6.02, p=.032.

Discussion

While presence/absence of signal represents a relatively simple method of measurement, it is important to note that this measure is an imperfect reflection of true telomere status. Factors unrelated to telomere length could reduce a signal below the detection threshold of our equipment, and therefore some telomeres may actually be present and functioning where no signal was observed. Nevertheless, it seems safe to assume that any extraneous factors should have equal influences on individuals with or without dementia or MCI-DS, and any differences in signal number associated with dementia status should be a valid indication of differential telomere length.

These results not only show that the number of “visible” telomere signals is significantly less in people with DS and dementia versus those in age- and sex-matched controls with DS only, and they suggest that adults with DS without dementia can be distinguished from adults with DS experiencing cognitive decline presumably associated with the progression of AD simply by counting the number of chromosome arms with no signal from the FITC-labeled PNA telomere probe. If these results are confirmed in a larger sample, findings will provide the foundation for a diagnostic procedure having both high sensitivity and specificity. As already mentioned, shorter telomeres have been found in people with AD compared to controls (Panossian et al., 2003; Franco et al., 2006) and in people with DS and dementia and/or MCI-DS versus people with DS only (Jenkins et al., 2006), and recently shorter telomeres have been observed in people with reduced immune function who are caregivers of patients with AD (Damjanovic et al., 2007). It will be interesting and exciting to determine whether the loss of signals that we have observed can be directly correlated with increased telomere shortening in these conditions. Only additional research will answer this question.

Since there is as yet no clear biomarker for dementia/Alzheimer’s disease, a longitudinal study would be useful to determine whether reduced signal number in individuals with DS precedes clinical signs of dementia, and to determine the underlying mechanism responsible for this association. Recognition of pre-clinical and early dementia would be very useful in this population of adults who already have preexisting cognitive impairments. Early detection is especially important because it would allow earlier treatment and justify the initiation of intervention strategies soon enough to minimize damage to the central nervous system. Further, a valid biomarker would be of great value for differential diagnosis, given the variety of conditions that can cause behavioral or cognitive changes in older adults with DS.

Acknowledgements

Thanks are due Lucille McLendon for production and cryopreservation of buffy coat cells for telomere studies, Peter Steinbach, Ph.D., for constructive criticism during manuscript preparation, and Mr. Black, Institute librarian. This work was supported in part by the New York State Office of Mental Retardation and Developmental Disabilities, Alzheimer’s Association grants IIRG-07-60558, IIRG-99-1598 and IIRG-96-077, NIH grants PO1-HD35897, RO1-HD37425, and RO1-AG 14673.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- Ahmed A, Tollefsbol T. Telomeres and telomerase: basic science implications for aging. J. Am. Geriatr. Soc. 2001;49:1105–11009. doi: 10.1046/j.1532-5415.2001.49217.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Allsopp RC, Caziri H, Patterson C, Boldsten SE, Younglai V, Futcher AB, Greider CW, Harley CB. Telomere length predicts replicative capacity of human fibroblasts. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 1992;89:10114–10118. doi: 10.1073/pnas.89.21.10114. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aylward E, Burt D D, Thorpe L, Lai F, Dalton A. Diagnosis of dementia in individuals with intellectual disability. J. Intellect. Disabil. Res. 1997;41:162–164. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2788.1997.tb00692.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Benetos A, Gardner JP, Zureik M, Labat C, Xiaobin L, Adamopoulos C, Temmar M, Bean KE, Thomas F, Aviv A. Short telomeres are associated with increased carotid atherosclerosis in hypertensive subjects. Hypertension. 2004;43(20):182–185. doi: 10.1161/01.HYP.0000113081.42868.f4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burt DB, Aylward E. Test battery for the diagnosis of dementia in individuals with intellectual disability. Journal of Intellectual Disability Research. 2000;44:262–270. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2788.2000.00264.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Damjanovic AK, Yang Y, Glaser R, Kiecolt-Glaser JK, Nguyen H, Laskowski B, Zou U, Beversdorf DQ, Weng NP. Accelerated telomere erosion is associated with a declining immune function of caregivers of Alzheimer’s disease patients. J. Immunol. 2007;179:4249–4254. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.179.6.4249. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Devenny DA, Krinsky-McHale SJ, Sersen G, Silverman WP. Sequence of cognitive decline in dementia in adults with Down's syndrome. J. Intellect. Disabil. Res. 2000;44(Pt 6):654–665. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2788.2000.00305.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Epel ES, Blackburn EH, Lin J, Dhabhar FS, Adler NE, Morrow JD, Cawthon RM. Accelerated telomere shortening in response to life stress. P.N.A.S. 2004;101(49):17312–17315. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0407162101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Flanary BE, Streit WJ. Telomeres shorten with age in rat cerebellum and cortex in vivo. J. Anti-Aging Med. 2003;6:299–308. doi: 10.1089/109454503323028894. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Franco S, Blasco MA, Siedlak SL, Harris PLR, Moreira PI, Perry G, Smith MA. Telomeres and telomerase in Alzheimer’s disease: Epiphenomena or a new focus for therapeutic strategy? Alzheimer’s & Dimentia. 2006;2:164–168. doi: 10.1016/j.jalz.2006.03.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gauthier S, Reisberg B, Zaudig M, Petersen RC, Ritchie K, Broich K, Bellevil H, Bennett D, Chertkow H, Cummings JL, de Leon M, Feldman H, Ganguli M, Scheltens P, Tierney MC, Whitehouse P, Winblad B. Mild cognitive impairment. Lancet. 2006;367(9518):1262–1270. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(06)68542-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hao LY, Strong MS, Greider CW. Phosphorylation of H2AX at short telomeres in T cells and fibroblasts. J. Biol. Chem. 2004;279(43):45148–45154. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M403924200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hastie ND, Dempster M, Dunlop MG, Thompson AM, Green DK, Allshire RC. Telomere reduction in human colorectal carcinomal and with ageing. Nature. 1990;346(6287):866–868. doi: 10.1038/346866a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jenkins EC, Velinov MT, Ye L, Gu H, Li S, Jenkins EC, Jr, Brooks SS, Pang D, Devenny DA, Zigman WB, Schupf N, Silverman WP. Telomere shortening in T lymphocytes of older individuals with Down syndrome and dementia. Neurobiol. Aging. 2006;27:41–45. doi: 10.1016/j.neurobiolaging.2005.05.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jenkins EC, Ye L, Gu H, Ni SA, Duncan CJ, Velinov M, Pang D, Krinsky-McHale SJ, Zigman WB, Schupf N, Silverman WP. Shorter telomeres may indicate dementia status in older individuals with Down syndrome. Neurobiol of Aging. 2008 doi: 10.1016/j.neurobiolaging.2008.06.001. doi:10.1016/j.neurobiolaging.2008.06.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krinsky-McHale SJ, Devenny DA, Kittler PK, Silverman W. Selective attention deficits associated with mild cognitive impairment and early-stage Alzheimer’s disease in adults with Down syndrome. Am J Ment. Ret. 2008 doi: 10.1352/2008.113:369-386. in press. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lansdorp PM, Verwoerd NP, van de Rijke FM, Dragowska V, Little MT, Dirk AK, Tanke HJ. Heterogeneity in telomere length of human chromosomes. Hum. Mol. Genet. 1996;5:685–691. doi: 10.1093/hmg/5.5.685. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lindsey J, McGill NI, Lindsey LA, Green DK, Cooke HJ. In vivo loss of telomeric repeats with age in humans. Mutat. Res. 1991;256(1):45–48. doi: 10.1016/0921-8734(91)90032-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Londoño-Vallejo JA, DerSarkissian H, Cazes L, Thomas G. Differences in telomere length between homologous chromosomes in humans. Nucleic Acids Res. 2001;29:3164–3171. doi: 10.1093/nar/29.15.3164. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mayer S, Brüderlein S, Perner S, Waibel I, Holdenried A, Ciloglu N, Hasel C, Mattfeldt T, Nielsen KV, Möller P. Sex-specific telomere length profiles and age-dependent erosion dynamics of individual chromosome arms in humans. Cytogenet. Genome Res. 2006;112:194–201. doi: 10.1159/000089870. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Panossian LA, Porter VR, Valenzuela HF, Znhu X, Reback E, Masterman D, Cummings JL, Effros RB. Telomere shortening in T cells correlates with Alzheimer’s disease status. Neurobiol. Aging. 2003;24:77–84. doi: 10.1016/s0197-4580(02)00043-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Perner S, Brüderlein S, Hasel C, Walbel I, Holdenried A, Ciloglu N, Chopurian H, Nielsen KV, Plesch A, Högel J, Möller P. Quantifying telomere lengths of human individual chromosome arms by centromere-calibrated fluorescence in situ hybridization and digital imaging. Am. J. Pathol. 2003;163(5):1751–1756. doi: 10.1016/S0002-9440(10)63534-1. 2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Petersen RC, Smith GE, Waring SC, Ivnik RJ, Tangalos EG, Kokmen E. Mild cognitive impairment: clinical characterization and outcome. Arch. Neurol. 1999;56(3):303–308. doi: 10.1001/archneur.56.3.303. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Plentz RR, Caselitz M, Bleck JS, Gebel M, Flemming P, Kubicka S, Manns MP, Rudolph KL. Hepatocellular telomere shortening correlates with chromosomal instability and the development of human hepatoma. Hepatology. 2004;40(1):80–86. doi: 10.1002/hep.20271. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Samani JJ, Boultby R, Butler R, Thompson JR, Goodall AH. Telomere shortening in atherosclerosis. Lancet. 2001;358(9280):472–473. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(01)05633-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schoeftner S, Blasco MA. Developmentally regulated transcription of mammalian telomeres by DNA-dependent RNA polymerase II. doi: 10.1038/ncb1685. Published online 23 December 2007; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schupf N, Pang D, Patel BN, Silverman W, Schubert R, Lai F, Kline JK, Stern Y, Ferin M, Tycko B. Onset of dementia is associated with age at menopause in women with Down syndrome. Ann. Neurol. 2003;54:433–438. doi: 10.1002/ana.10677. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Silverman W, Schupf N, Zigman W, Devenny D, Miezejeski C, Schubert R, Ryan R. Dementia in adults with mental retardation: assessment at a single point in time. Am. J. Ment. Retard. 2004;109(2):111–125. doi: 10.1352/0895-8017(2004)109<111:DIAWMR>2.0.CO;2. 2004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Valdes AM, Andrew T, Gardner JP, Kimura M, Oelsner E, Cherkas LF, Aviv A, Spector TD. Obesity, cigarette smoking, and telomere length in women. Lancet. 2005;366(9486):662–664. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(05)66630-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Valdes AM, Richards JB, Gardner JP, Swaminathan R, Kimura M, Xiaobin L, Aviv A, Spector TD. Telomere length correlates with bone mineral density and is shorter in women with osteoporosis. Osteoporosis Int. 2007;18(9):1203–1210. doi: 10.1007/s00198-007-0357-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vulliamy TJ, Dokal I. The diverse clinical presentation of mutations in the telomerase complex. Biochimie. 2007;90(1):122–130. doi: 10.1016/j.biochi.2007.07.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Winblad B, Palmer K, Kivipelto M, Jelic V, Fratiglioni L, Wahlund LO, Nordberg A, Backman L, Alber Arai H, Basun H, Blennow K, de Leon M, DeCarli C, Erkinjuntti T, Giacobini E, Graff C, Hardy J, Jack K, van Duijn C, Visser P, Petersen RC. Mild cognitive impairment--beyond controversies, towards a consensus: report of the International Working Group on Mild Cognitive Impairment. J. Intern. Med. 2004;256(3):240–246. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2796.2004.01380.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zigman WB, Schupf N, Devenny DA, Miezejeski C, Ryan R, T, Urv K, Schubert R, Silverman W. Incidence and prevalence of dementia in elderly adults with mental retardation without Down syndrome. Am. J. Ment. Retard. 2004;109(2):126–141. doi: 10.1352/0895-8017(2004)109<126:IAPODI>2.0.CO;2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]