Abstract

Substrates of the N-end rule pathway include proteins with destabilizing N-terminal residues. These residues are recognized by E3 ubiquitin ligases called N-recognins. Ubr1 is the N-recognin of the yeast Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Extracellular amino acids or short peptides up-regulate the peptide transporter gene PTR2, thereby increasing the capacity of a cell to import peptides. Cup9 is a transcriptional repressor that down-regulates PTR2. The induction of PTR2 by peptides or amino acids involves accelerated degradation of Cup9 by the N-end rule pathway. We report here that the Ubr1 N-recognin, which conditionally targets Cup9 for degradation, is phosphorylated in vivo at multiple sites, including Ser300 and Tyr277. We also show that the type-I casein kinases Yck1 and Yck2 phosphorylate Ubr1 on Ser300, and thereby make possible (“prime”) the subsequent (presumably sequential) phosphorylations of Ubr1 on Ser296, Ser292, Thr288, and Tyr277 by Mck1, a kinase of the glycogen synthase kinase 3 (Gsk3) family. Phosphorylation of Ubr1 on Tyr277 by Mck1 is a previously undescribed example of a cascade-based tyrosine phosphorylation by a Gsk3-type kinase outside of autophosphorylation. We show that the Yck1/Yck2-mediated phosphorylation of Ubr1 on Ser300 plays a major role in the control of peptide import by the N-end rule pathway. In contrast to phosphorylation on Ser300, the subsequent (primed) phosphorylations, including the one on Tyr277, have at most minor effects on the known properties of Ubr1, including regulation of peptide import. Thus, a biological role of the rest of Ubr1 phosphorylation cascade remains to be identified.

Keywords: Mck1, proteolysis, Yck1

The uptake of di- and tripeptides (di/tripeptides) in the yeast Saccharomyces cerevisiae is regulated by the N-end rule pathway, one proteolytic pathway of the Ub-proteasome system (Fig. 1A) (1–4). The N-end rule relates the in vivo half-life of a protein to the identity of its N-terminal residue (5–8). Degradation signals (degrons) that are targeted by the N-end rule pathway include a set called N-degrons (5, 9). The main determinant of an N-degron is a destabilizing N-terminal residue of a substrate protein (5, 9).

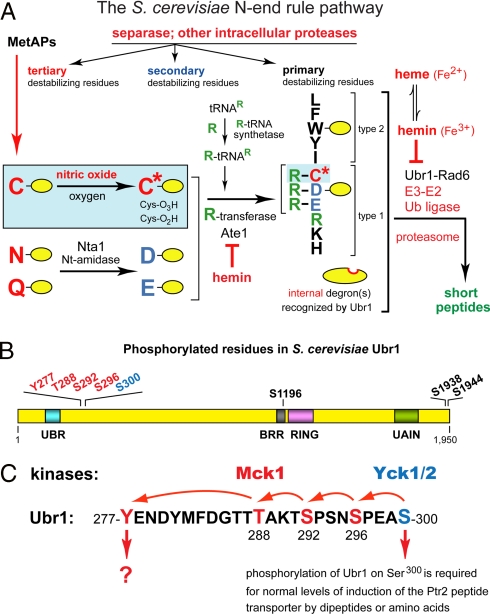

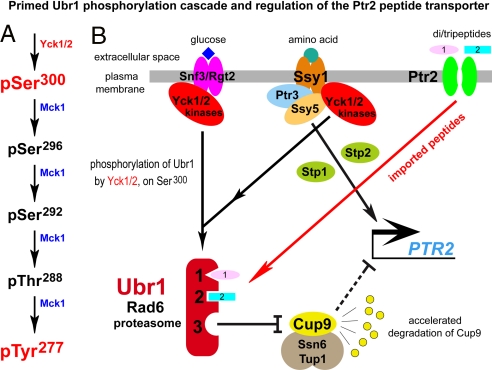

Fig. 1.

The N-end rule pathway, in vivo phosphorylation sites in S. cerevisiae Ubr1, and the primed cascade of Ubr1 phosphorylation. (A) The S. cerevisiae N-end rule pathway. N-terminal residues are indicated by single-letter abbreviations for amino acids. Yellow ovals denote the rest of a protein substrate. Hemin (Fe3+-heme) inhibits arginylation by R-transferase in both S. cerevisiae and mammals (12). MetAPs, methionine aminopeptidases. Reactions in the shaded rectangle are a part of the N-end rule pathway that is active in eukaryotes which produce NO (11). These reactions may also be relevant to S. cerevisiae, which lacks NO synthase but can produce NO by other routes, and can also be influenced by NO from extracellular sources. C* denotes oxidized Cys, either Cys-sulfinate or Cys-sulfonate (11). Type-1 and -2 destabilizing N-terminal residues of N-end rule substrates are recognized by Ubr1, the sole E3 Ub ligase of S. cerevisiae. Through its third substrate-binding site, Ubr1 targets internal (non-N-terminal) degrons in substrates (denoted by a larger oval) such as Cup9, a transcriptional repressor (1, 3, 4). (B) Phosphorylated residues of S. cerevisiae Ubr1 identified in the present work. Also indicated are the conserved Ubr1 regions such as the UBR box, the BRR (basic residues-rich) domain, the Cys/His-rich RING domain, and the UAIN (UBR autoinhibitory) domain (2). (C) The cascade of Ubr1 phosphorylation discovered in the present work. Initial phosphorylation of Ubr1 on Ser300 by the CKI-type Yck1/Yck2 kinases makes possible (“primes”) the subsequent (apparently sequential) phosphorylations of Ubr1 by Mck1 (a Gsk3-type kinase) on Ser296, Ser292, Thr288, and Tyr277. Also indicated is the identified function of Ser300 phosphorylation.

The N-end rule has a hierarchic structure that involves the primary, secondary, and tertiary destabilizing N-terminal residues (Fig. 1A). Destabilizing activities of these residues differ by their requirements for a preliminary enzymatic modification, a set of reactions that includes N-terminal deamidation and arginylation (8–12). In mammals and other multicellular eukaryotes, the set of arginylated residues contains not only Asp and Glu but also N-terminal Cys, which is arginylated after its oxidation to Cys-sulfinate or Cys-sulfonate. The in vivo oxidation of N-terminal Cys requires nitric oxide (NO), oxygen (O2), and/or their derivatives (Fig. 1A) (8, 11).

E3 Ub ligases of the N-end rule pathway are called N-recognins (5, 8, 13, 14). They bind to primary destabilizing N-terminal residues. At least 4 N-recognins, including Ubr1, mediate the N-end rule pathway in mammals and other multicellular eukaryotes (8). N-recognins share a ≈70-residue motif called the UBR box. Mouse Ubr1 and Ubr2 are the sequelogous (15) 200-kDa RING-type E3 Ub ligases. The N-end rule pathway of S. cerevisiae is mediated by a single N-recognin, Ubr1, a 225-kDa sequelog of mammalian Ubr1 and Ubr2 (Fig. 1A) (2, 13, 14). Ubr1 contains at least 3 substrate-binding sites. The type-1 and type-2 sites are specific for basic (Arg, Lys, His) and bulky hydrophobic (Trp, Phe, Tyr, Leu) N-terminal residues, respectively. The third binding site of Ubr1 recognizes, in particular, an internal (non-N-degron) degradation signal in Cup9, a transcriptional repressor of a regulon that includes PTR2, which encodes the transporter of di/tripeptides (16). This site of Ubr1 is autoinhibited but can be activated through the binding of di/tripeptides to the type-1/2 sites of Ubr1 (1, 2, 13). The resulting acceleration of the Ubr1-dependent degradation of Cup9 decreases its levels and thereby induces the Ptr2 transporter. This positive-feedback circuit allows S. cerevisiae to detect the presence of extracellular peptides and to react by increasing their uptake (1, 2).

The functions of the N-end rule pathway include the sensing of NO, oxygen, short peptides, and heme (Fig. 1A); the maintenance of high fidelity of chromosome segregation, through the degradation of a separase-produced fragment of cohesin subunit; regulation of peptide import, through the degradation of Cup9 (see above); regulation of signaling by transmembrane receptors, through the NO/O2-dependent degradation of specific RGS proteins that down-regulate G proteins; regulation of apoptosis, meiosis, spermatogenesis, neurogenesis, and cardiovascular development in mammals, and regulation of leaf senescence in plants (refs. 1, 2, 4, 8, 10–12, 17 and refs. therein). Mutations in human Ubr1 are the cause of Johansson–Blizzard Syndrome (JBS), which includes mental retardation, physical malformations and severe pancreatitis (18).

In the present study, we show that the Ubr1 Ub ligase is phosphorylated in vivo at multiple sites, including Ser300 and Tyr277. We found that the type-I casein kinases Yck1 and Yck2 phosphorylate Ubr1 on Ser300 and thereby make possible (“prime”) the subsequent phosphorylation of Ubr1 on Ser296, Ser292, Thr288, and Tyr277. The latter phosphorylations are mediated by Mck1, a member of the glycogen synthase kinase 3 (Gsk3) family. We also show that phosphorylation of Ubr1 on Ser300 plays a major role in the control of peptide import by the N-end rule pathway.

Results and Discussion

Identification of in Vivo Ubr1 Phosphorylation Sites Using Mass Spectrometry.

To determine the sites of Ubr1 phosphorylation, we used tryptic digestion of Ubr1, capillary liquid chromatography, and peptide sequencing by mass spectrometry (cLC-MS/MS) [supporting information (SI) Text and Fig. S1]. The following Ubr1-derived phosphopeptides were identified: (i) pY277ENDYMFDGTTTAK and YENDYMFDGTTpT288AK, (ii) pT291SPSNpS296PEASPLAK or TpS292PSNpS296PEASPLAK, (iii) pT291SPSNpS296PEApS300PLAK or TpS292PSNpS296PEApS300PLAK, (iv) EHEpS1196EFDEQDNDVDMVGEK, (v) NLDEDDpS1938DDNDDDER, and (vi) NLDEDDpS1938DDNDDpS1944DER. Although cLC-MS/MS alone could not distinguish between phosphorylation at Thr291 vs. Ser292, the latter residue was the more likely one, given the presence of a consensus phosphorylation site for a Gsk3-type kinase (S/T-X-X-X-S/T). We changed Ser292 of Ubr1 to Ala and found this mutation (S292A) abolished phosphorylation on Tyr277. Together, these analyses identified 8 in vivo phosphorylation sites (Fig. 1B). Five of these sites were clustered in a 25-residue region of the 1,950-residue Ubr1, between the previously delineated locations (13) of its type-1 and -2 substrate-binding sites (Fig. 1B and Fig. S1).

In Vivo Phosphorylation of Ubr1 on Tyr277.

As a part of this study, we produced an affinity-purified rabbit antibody (termed Ab1ScUbr1(1–1140)) to N-terminal half of S. cerevisiae Ubr1. To detect the in vivo phosphorylation of Tyr277 by a method other than MS, we also produced an affinity-purified rabbit antibody (termed Ab1pY277Ubr1) against a peptide that contained phospho-Tyr277 and adjacent Ubr1 sequences. Ab1pY277Ubr1 recognized both the phosphopeptide and Tyr277-phosphorylated Ubr1 (Ubr1pY277) and did not recognize the unphosphorylated peptide or Ubr1Y277F, which contained a nonphosphorylatable (Phe) residue at position 277 (Fig. 2 A and B). The epitope(s) recognized by Ab1pY277Ubr1 could be removed by treating Ubr1 with lambda protein phosphatase; the epitope was retained in the presence of phosphatase inhibitors (Fig. 2C).

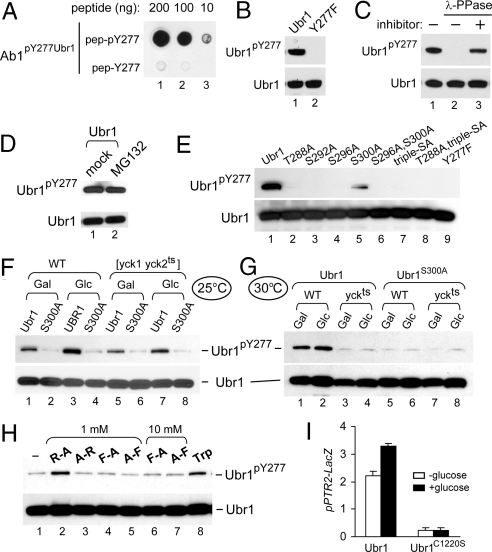

Fig. 2.

Phosphorylation of Ubr1 on Tyr277. (A) Characterization of antibody, termed Ab1pY277Ubr1, that was raised against a Ubr1 phosphopeptide QFLNDLKpY277ENDY. Dot immunoblotting with affinity-purified Ab1pY277Ubr1, using indicated amounts of the spotted QFLNDLKpYENDY phosphopeptide and its unphosphorylated counterpart. (B) Specificity of Ab1pY277Ubr1. Purified wild-type Ubr1 (which contains Ubr1pY277) and Ubr1Y277F were subjected to SDS-NuPAGE (4–12%) and immunoblotted with affinity-purified Ab1pY277Ubr1 (1:1,000), and thereafter with Ab1ScUbr1(1–1140). (C) Purified wild-type Ubr1 (0.25 μg) was incubated with 400 units of λ phosphatase (λ-PPase) in the presence or absence of phosphatase inhibitors for 2 h at 30 °C, followed by SDS/PAGE and sequential immunoblotting, as in B. (D) S. cerevisiae CHY50 [ubr1Δ pdr5Δ] expressing the N-terminally flag-tagged Ubr1 (fUbr1), was grown in SC(-Leu) and treated for 3 h either with MG132 (at 50 μM) or with an equivalent volume of its stock-solution solvent dimethyl sulfoxide. Cell extracts were subjected to SDS/PAGE and sequential immunoblotting, as in B. (E) Ubr1 phosphorylation on Tyr277 depends on phosphorylation at other sites. JD55 (ubr1Δ) cells were transformed with pFlagUBR1SBX-based plasmids that expressed wild-type Ubr1 or its indicated derivatives. Cells were grown to A600 of ≈1 in SC(-Leu). Cell extracts were subjected to SDS-NuPAGE (4–12%) and sequential immunoblotting, as in B. (F and G) Wild-type LRB906 [YCK1 YCK2] or LRB756 [yck1Δ yck2ts] strains (Table S1) that expressed wild-type fUbr1 or fUbr1S300A (in the ubr1Δ background) were grown in a galactose-containing medium, with or without a subsequent addition of glucose, either at 25 °C (permissive temperature for Yck2ts) or at 30 °C (semipermissive temperature for Yck2ts). Cell extracts were subjected to SDS/PAGE and sequential immunoblotting with Ab1pY277Ubr1 and anti-flag antibodies. (H) AVY26 (ubr1Δ) S. cerevisiae expressing wild-type Ubr1 from pSOB33 (Tables S1 and S2) was grown to A600 of ≈0.8 in SHM medium in the presence of indicated dipeptides, at 1 mM or 10 mM, or in the presence of Trp (98 μM). Cell extracts were subjected to SDS/PAGE and immunoblotting, as in B. (I) CHY201 (ubr1Δ) S. cerevisiae (Table S1) carried the plasmid pSS4 (PPTR2-lacZ) and either pCH100 (wild-type Ubr1) or pCH159 (Ubr1MR1), the latter expressing Ubr1C1220S, which is inactive as an E3 (14). Cultures were grown at 25 °C in galactose-containing SGal(-Ura,-Leu) medium to A600 of ≈0.8, followed by the addition of either galactose (to 4% total) (white bars) or glucose (to 4%) (black bars), further incubation for 2.5 h, and measurements of βgal activity in cell extracts.

The in vivo levels of Ubr1pY277 (relative to total Ubr1) were increased upon the addition of glucose, an amino acid such as Trp, or a type-1 dipeptide such as Arg-Ala (Fig. 2 F–H). We also expressed Ubr1 in S. cerevisiae CHY50, a [ubr1Δ pdr5Δ] strain that was sensitive to a proteasome inhibitor such as MG132. The levels of Ubr1pY277 were not increased by treatment with MG132 (Fig. 2D). This test was performed in part because some Ubr1 mutants at position 277, such as Ubr1Y277A, and Ubr1Y277E, were found to be short-lived in vivo (Fig. S2 D and E). These results indicated that that the identity of a residue at position 277 is critical for a metabolically stable conformation of Ubr1. The above Ubr1 mutants are described solely in SI (Fig. S2 B–E), because the levels of Ubr1pY277 were not altered by inhibition of the proteasome (Fig. 2D), suggesting (but not proving) that the metabolic stability of Ubr1pY277 is comparable to that of Ubr1 unphosphorylated on Tyr277.

Truncated derivatives of Ubr1 (2, 13) and the Ab1pY277Ubr1 antibody were used to determine “large-scale” requirements for the in vivo phosphorylation of Ubr1 on Tyr277. Remarkably, no phosphorylation on Tyr277 was observed with the fUbr11–717 fragment, in contrast to “wild-type” levels of Tyr277 phosphorylation with Ubr11–1140f, fUbr11–1367, fUbr11–1700, and fUbr11–1818 fragments (Fig. S3A). Thus, a region between positions 717 and 1,140 (Fig. 1B) was essential for the phosphorylation of Ubr1 on the far-upstream Tyr277 residue (Fig. S3A), suggesting that this phosphorylation may require an appropriate conformation and/or a preceding phosphorylation at other residues of Ubr1.

Tyr277 of Ubr1 Is Phosphorylated by Mck1, a Member of the Gsk3 Kinase Family.

We used Ab1pY277Ubr1 (Fig. 2 A–C) and a library of yeast mutants in 27 putative Tyr kinases (see SI Text) to screen for the ability of these mutants to phosphorylate Ubr1 on Tyr277 in vivo. A mutant lacking the Mck1 kinase was found to be nearly incapable of phosphorylating Ubr1 on Tyr277 (Fig. S4A, lane 5). This defect could be rescued by wild-type Mck1 but could not be rescued by Mck1D164A (19), a catalytically inactive mutant (Fig. S4B). Expression of Mck1Y199F, a possibly leaky mutant in the activation loop of this kinase (ref. 19 and refs. therein), weakly but detectably rescued the Tyr277-specific phosphorylation of Ubr1 (Fig. S4B).

Mck1 is a member of the Gsk3 family of kinases, present in all eukaryotes (19, 20). In addition to Mck1, the S. cerevisiae genome encodes 3 other kinases of this family, Rim11, Mrk1, and Ygk3. In contrast to the near absence of Tyr277-specific phosphorylation of Ubr1 in mck1Δ cells, this phosphorylation remained unperturbed in rim11Δ, mrk1Δ, or ygk3Δ cells (Fig. S4A). Moreover, double and triple mutants, the latter lacking all 3 Gsk3-type kinases other than Mck1, did not exhibit a significant decrease in the Tyr277-specific Ubr1 phosphorylation (data not shown), indicating a unique role of Mck1 in phosphorylating Ubr1 on Tyr277. We also overexpressed His6-tagged derivatives of either wild-type Mck1 or its catalytically inactive Mck1D164A mutant in S. cerevisiae and purified them to near homogeneity (Fig. S3B). Wild-type Ubr1 and Ubr1Y277F were expressed in the mck1Δ strain (Fig. S4A, lane 5) and also purified. Ubr1 or Ubr1Y277F were incubated with Mck1 or Mck1D164A and γ[32]ATP, followed by SDS/PAGE and autoradiography. Wild-type Mck1 phosphorylated wild-type Ubr1, whereas the amounts of 32P were much lower (but not zero; see below) with Ubr1Y277F, which could not be phosphorylated at position 277 (Fig. 3A). Immunoblotting of the same reaction products with Ab1pY277Ubr1 directly confirmed that Mck1 phosphorylated Ubr1 on Tyr277 (Fig. 3A). We conclude that Mck1 is by far the major (possibly the sole) kinase that phosphorylates Ubr1 on Tyr277.

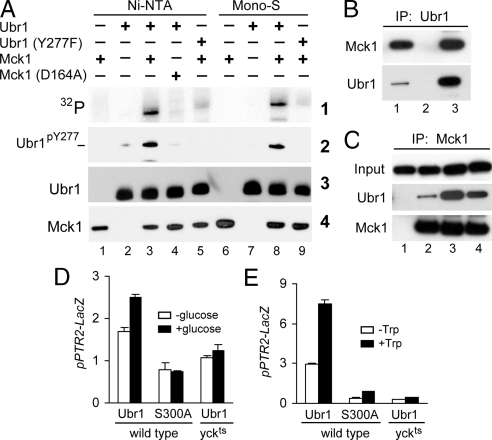

Fig. 3.

Phosphorylation of Ubr1 by Yck1/Yck2 and Mck1 kinases. (A) Purified Mck1 phosphorylates Ubr1 on Tyr277. Wild-type fUbr1 and its fUbr1Y277F derivative were purified from mck1Δ S. cerevisiae; 0.1 μg of fUbr1 or fUbr1Y277F were incubated with 0.1 μg of either partially purified (“Ni-NTA”) or additionally purified (“Mono-S”) ha-tagged Mck1, or with its indicated derivatives in the presence of γ-[32]ATP at 30 °C for 30 min, followed by SDS/PAGE and sequential immunoblotting with Ab1pY277Ubr1, anti-flag, and anti-ha antibodies. (B) Extracts from JD55 (ubr1Δ) cells expressing fUbr1 and Mck1-ha were incubated with beads only (lane 2) or anti-flag beads (lane 3). Bound proteins were eluted and analyzed by SDS/PAGE and immunoblotting with anti-HA and anti-flag antibodies. Lane 1, 0.1% of total extract. (C) Extracts from JD55 (ubr1Δ) cells expressing fUbr1 or fUbr1Y277F and coexpressing Mck1-ha were processed for immunoprecipitation, SDS/PAGE, and immunoblotting, as in B. “Input” samples before immunoprecipitation, with immunoblotting using anti-flag. Lane 1, cells expressed fUbr1 alone (control). Lane 2, same as lane 1 but cells expressed both fUbr1 and Mck1-ha. Lane 3, CHY89 (mck1Δ ubr1Δ) cells that lacked endogenous Mck1 and expressed both fUbr1 and Mck1D164A-ha. Lane 4, same as lane 2 but with cells that expressed fUbr1Y277F and Mck1-ha. (D) CHY201 (ubr1Δ) and CHY202 (ubr1Δ yck1Δ yck2ts) S. cerevisiae carried pSS4 (PPTR2-lacZ) and either pCH100 (wild-type Ubr1) or pCH114 (Ubr1S300A) (Tables S1 and S2). Cultures were grown in SGal(-Ura,-Leu) at 25 °C to A600 of ≈0.8, and thereafter were shifted to 37 °C for 20 min, followed by the addition of either galactose (to 4% total) (white bars) or glucose (to 4%) (filled bars) and further incubation at 37 °C for 2.5 h, followed by measurements of βgal activity in cell extracts. (E) CHY203 (ubr1Δ) and CHY204 (ubr1Δ yck1Δ yck2ts) S. cerevisiae carried pSS4 (PPTR2-lacZ) and either pCH100 (wild-type Ubr1) or pCH114 (Ubr1S300A) (Tables S1 and S2). Cultures were grown to A600 of ≈0.8 in SHM medium (see SI Text) at 25 °C and thereafter were shifted to 37 °C for 2.5 h in the same medium either without or with the addition of Trp to 98 μM, followed by processing as in D.

Reciprocal coimmunoprecipitation tests confirmed that Ubr1 specifically interacted with Mck1 (Fig. 3 B and C). As would be expected, the apparent affinity of Mck1 for Ubr1 was higher with either unphosphorylated Ubr1 (isolated from mck1Δ cells expressing catalytically inactive Mck1D164A-ha) or with Ubr1Y277F (which could not be phosphorylated at position 277) than with wild-type Ubr1 from cells containing wild-type Mck1 (Fig. 3C). The binding of the Ubr1 Ub ligase to Mck1 did not make the latter short-lived in vivo (data not shown).

A “Primed” Ubr1 Phosphorylation Cascade That Begins at Ser300 Involves 3 Other Serines/Threonines and Concludes with Tyr277.

We identified Thr288, Ser292, Ser296, and Ser300 of Ubr1 as the sites of its in vivo phosphorylation downstream of Tyr277, a residue phosphorylated by Mck1 (Figs. 1B and 3A and Fig. S1). A NetPhosK program (www.cbs.dtu.dk/services/NetPhosK) pinpointed Thr288, Ser292, Ser296, and Ser300 of Ubr1 as putative sites of phosphorylation by Gsk3-type kinases. To address these issues, we constructed Ubr1 mutants that retained Tyr277 but contained single or multiple mutations to Ala at the above Ser/Thr sites. We then used Ab1pY277Ubr1, which recognized Ubr1pY277, to determine the extent of in vivo phosphorylation of mutant Ubr1 proteins on Tyr277. Strikingly, no phosphorylation on Tyr277 was observed with Ubr1T288A, Ubr1S292A, and Ubr1S296A, and also with multisite mutants Ubr1S296A,S300A, Ubr1S292A,S296A,S300A, and Ubr1T288A,S292A,S296A,S300A, whereas Ubr1S300A exhibited a detectable but greatly reduced phosphorylation on Tyr277 (Fig. 2E). Thus, the Mck1-mediated phosphorylation on Tyr277 is the last step of a phosphorylation cascade that involves the obligatory preceding (“priming”) phosphorylations of Ser/Thr residues that are close to position 277 of Ubr1 (Fig. 1 B and C). These data, together with a low but significant in vitro Mck1-mediated phosphorylation of Ubr1Y277F, which could not be phosphorylated at position 277 (Fig. 3A), strongly suggested (but did not formally prove) that the observed phosphorylation of Ubr1 on Thr288, Ser292, and Ser296 is also carried out by Mck1 (Fig. 1C).

Yck1 and Yck2 Are “Priming” Kinases That Phosphorylate Ubr1 on Ser300 and Initiate the Mck1-Mediated Phosphorylations on Thr288, Ser292, Ser296, and Tyr277.

In a cascade that is referred to as “primed” phosphorylation, specific residues of a protein must be phosphorylated sequentially rather than independently of one another, in that a “downstream” phosphorylation event requires one or more of preceding phosphorylations (21). Kinases that phosphorylate at a position required for subsequent phosphorylations are referred to as “priming” kinases (refs. 20–22 and refs. therein). In the known Gsk3 cascades, a frequently encountered preference is for a prior phosphorylation, often by a distinct kinase, of a residue at +4 position relative to a residue to be phosphorylated next. This previously established rule is consistent with the distances between the Ser300, Ser296 Ser292, and Thr288 residues of Ubr1 (Fig. 1C). A prior phosphorylation by a priming kinase is not always strictly essential, in that in most cases a priming phosphorylation greatly increases the activity of a Gsk3-type kinase at a “dependent” phosphorylation site, typically by 100- to 1,000-fold (21).

According to the NetPhosK program, Ser300 of S. cerevisiae Ubr1 was a plausible phosphorylation site for either Gsk3-type kinases or Pho85, of the CDK kinase family. We found that null mutations in either S. cerevisiae Pho85 or the non-Mck1 kinases of the Gsk3 family (Rim11, Mrk1, and Ygk3) did not affect the Mck1-mediated phosphorylation of Ubr1 on Tyr277 in vivo (Fig. S4A). Previous work has shown that Yck1/Yck2, 2 sequelogous S. cerevisiae kinases of the casein kinase-I (CKI) family (23) are essential components of systems such as glucose-mediated signaling pathways (24), bud-localized mRNA translation (25), and the signaling mediated by extracellular amino acids, particularly the SPS pathway (26–28). In mammals, CKI-type kinases regulate a multitude of processes, including the cell cycle, circadian rhythms, membrane trafficking, chromosome segregation, and apoptosis (23).

S. cerevisiae contains 4 sequelogous kinases of the CKI family: Yck1, Yck2, Yck3, and Hrr25. Yck1 and Yck2 are peripheral membrane proteins whose localization at the plasma membrane requires palmitylation of their C-terminal Cys-Cys motif (refs. 27 and 28 and refs. therein). Yck1 and Yck2 complement each other in a number of functions (27). We carried out coimmunoprecipitation with the flag-tagged Ubr1 (fUbr1) and myc-tagged Yck1 (Yck1-myc) that were coexpressed in ubr1Δ cells. fUbr1 was coimmunoprecipitated with Yck1-myc (Fig. S4 C and D). Moreover, fUbr1 could be efficiently phosphorylated, in the presence of γ[32]ATP, in immunoprecipitates with wild-type (C-terminally tagged) Yck1-myc but not with inactive Yck1K98R-myc or with beads alone (Fig. S4E). Yck1 assays were also carried with GST-Ubr1227–327 and GST-Ubr1227–327,S300A. GST-Ubr1227–327 was phosphorylated in immunoprecipitates with wild-type Yck1-myc but not with inactive Yck1K98R-myc (Fig. S4F). Crucially, the otherwise identical GST-Ubr1227–327,S300A, which contained Ala at position 300 of Ubr1, was at most weakly phosphorylated by Yck1-myc (Fig. S4F). Together, these results indicated that the CKI-type Yck1 and Yck2 kinases (either one of them was sufficient; data not shown) functioned as priming kinases of Ubr1, phosphorylating its Ser300 and thereby making possible (“priming”) the cascade of Mck1-mediated phosphorylations that converged on Tyr277 (Fig. 1C).

Yck1/Yck2-Primed, Mck1-Mediated Phosphorylation of Ubr1 on Tyr277 Is Increased by Glucose, Amino Acids, or Type-1 Dipeptides.

The addition of glucose, an amino acid such as Trp, or a type-1 dipeptide such as Arg-Ala to a growth medium significantly increased the in vivo levels of Ubr1pY277 (Fig. 2 F–H). To determine whether glucose-mediated increases of Ubr1pY277 required the priming Yck1/Yck2 kinases that initially phosphorylate Ubr1 on Ser300, we used a wild-type [YCK1 YCK2] strain and a temperature-sensitive (ts) [yck1Δ yck2ts] strain that lacked Yck1 and contained a ts-Yck2 kinase (Yck2ts). These strains (Table S1) were constructed to express either wild-type Ubr1 or Ubr1S300A, which could not be phosphorylated at position 300. Exponential cultures in a 2% galactose-containing medium at 25 °C (permissive temperature for Yck2ts) or at 30 °C (semipermissive temperature) were left growing with galactose or were modified by the addition of glucose to 4% and further incubation for 2.5 h at either 25 °C or 30 °C. With [YCK1 YCK2] cells, phosphorylation of Ubr1 on Tyr277 was increased upon the addition of glucose at 25 °C. By contrast, at 30 °C the level of Ubr1pY277 was greatly reduced in [yck1Δ yck2ts] cells (Fig. 2 F and G). In addition, glucose did not increase phosphorylation of Ubr1 on Tyr277 in [yck1Δ yck2ts] cells when these cells were cultured further at the nonpermissive temperature of 37 °C for 2.5 h (data not shown). The increased phosphorylation on Tyr277 required Ser300, because no change in the levels of Ubr1pY277 was observed in otherwise identical experiments with Ubr1S300A (Fig. 2 F and G). In agreement with this result, the level of Ubr1pY277 increased upon the addition of glucose at 25 °C but not at 30 °C in [yck1Δ yck2ts] cells (Fig. 2 F and G).

Normal Induction of the Ptr2 Peptide Transporter by Amino Acids, Dipeptides, or Glucose Requires Phosphorylation of Ubr1 on Ser300 by Yck1/Yck2.

By measuring the expression of PPTR2-lacZ transcriptional reporter, we found that the addition of glucose to cells growing on galactose led to a modest (≈1.6-fold) but reproducible induction of the transporter-encoding PTR2 gene in wild-type (UBR1) cells but not in cells that expressed the catalytically inactive Ubr1C1220S mutant (Fig. 2I). Glucose-mediated increase of PTR2 expression required the Yck1/Yck2 kinases and phosphorylation of Ubr1 on Ser300, because no induction of PTR2 by glucose occurred at 37 °C either in [yck1Δ yck2ts] cells that expressed wild-type Ubr1 or in [YCK1 YCK2] cells that expressed Ubr1S300A (Fig. 3D).

Addition of an amino acid such as Trp significantly increased the levels of Ubr1pY277 (Fig. 2H, lane 8; compare with lane 1 or 3). In vitro kinase assays (data not shown) indicated this effect of Trp was not mediated by an increase in the activity of the Mck1 kinase. The addition of Trp also induced the expression of PTR2 by >2-fold (Fig. 3E). The induction of PTR2 by Trp was nearly abolished in [YCK1 YCK2] cells that expressed Ubr1S300A instead of wild-type Ubr1 or in [yck1Δ yck2ts] cells at 37 °C in the presence of wild-type Ubr1 (Fig. 3E). Together, these findings strongly suggested that Trp causes the formation of Ubr1pY277 through the demonstrated (ref. 27 and refs. therein) activation of the Yck1/Yck2 kinases by the SPS pathway or through inhibition of a phosphatase(s) that dephosphorylates the phospho-Ser300 residue of Ubr1.

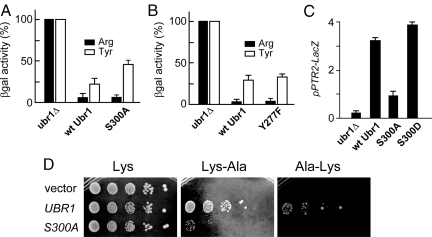

Ubr1S300A was indistinguishable from wild-type Ubr1 in mediating the in vivo degradation of a type-1 N-end rule substrate such as Arg-βgal (Fig. 4A). However, Ubr1S300A was considerably impaired in mediating the degradation of either a type-2 N-end rule substrate such as Tyr-βgal (Fig. 4A) or the Cup9 repressor (Fig. S4G and data not shown). Cup9 is targeted by Ubr1 through an internal degron (see Introduction). A strongly impaired ability of Ubr1S300A to induce PTR2 could also be observed in experiments where a mixture of amino acids was present (Fig. 4C). The (previously described) Trp-induced acceleration of Cup9 degradation (4) was found to be nearly absent in cells that expressed Ubr1S300A instead of wild-type Ubr1 (Fig. S4G and data not shown). This result accounted, at least in part, for the decreased ability of Ubr1S300A to mediate the induction of PTR2 by amino acids (Figs. 3E and 4C).

Fig. 4.

Functional consequences of Ubr1 alterations at position 300. (A) Relative levels of Arg-βgal (filled bars) and Tyr-βgal (white bars), a type-1 and a type-2 N-end rule substrate, respectively (Fig. 1A), in ubr1Δ S. cerevisiae or in the same strain that expressed either wild-type Ubr1 or Ubr1S300A. (B) Same as in A but an independent experiment, and Ubr1Y277F instead of Ubr1S300A. (C) Effects of Ubr1 mutations at position 300 on PTR2 expression. S. cerevisiae JD55 (ubr1Δ) carried pSS4 (PPTR2-lacZ) and either pCH100 (wild-type Ubr1), pCH114 (Ubr1S300A) pCH246 (Ubr1S300D). Cultures were grown to A600 of ≈0.8 at 30 °C in SC containing a mixture of compounds (including amino acids) required by a strain, followed by measurements of βgal activity in cell extracts. (D) JD55 (ubr1Δ) S. cerevisiae carrying either the empty vector (pRS315), or pCH100 (wild-type Ubr1), or pCH114 (Ubr1S300A) (Table S2) were serially diluted 5-fold and spotted on SC(-Leu, -Lys) plates containing 110 μM Lys, or 66 μM Lys-Ala, or 66 μM Ala-Lys. The plates were incubated at 30 °C for 3 days.

Type-1 dipeptides such as Lys-Ala (which bind to Ubr1 and thereby accelerate Cup9 degradation) can up-regulate peptide import and thus enable survival of cells on media with peptides as sole sources of a required amino acid (1). In agreement with other data (see above) about functional significance of Ubr1 phosphorylation on Ser300, Ubr1S300A was strongly impaired in the growth-based peptide import assay, in contrast to wild-type Ubr1 (Fig. 4D). A different test involved Ubr1S300D, in which Ser300 was converted to Asp, a “mimic” of phospho-Ser. This experiment provided yet another, independent evidence for the functional importance of phosphorylation on Ser300. Specifically, the Ubr1S300D mutant was more active than wild-type Ubr1 (and much more active than Ubr1S300A) in mediating the expression of PTR2 (Fig. 4C). Whereas a type-1 dipeptide such as Arg-Ala (at 1 mM) significantly increased the levels of Ubr1pY277, a type-2 dipeptide such as Phe-Ala did not have this effect even at 10 mM (Fig. 2H), for reasons that remain to be understood.

Concluding Remarks

Several E3 Ub ligases of the Ub-proteasome system have been shown to be regulated through phosphorylation (refs. 29–31 and refs. therein). We discovered a “primed” phosphorylation cascade that involves Ser300, Ser296, Ser292, Thr288, and Tyr277 of Ubr1, the E3 Ub ligase (N-recognin) of the N-end rule pathway in S. cerevisiae (Figs. 1 B and C and 5). This cascade is mediated by Yck1 and Yck2, 2 sequelogous type-I casein kinases that act as “priming” kinases for the Mck1 kinase of the Gsk3 family. Phosphorylation of Ubr1 on Ser300 by the functionally overlapping Yck1/Yck2 kinases makes the resulting Ubr1pS300 a substrate of Mck1, which phosphorylates 3 Ser/Thr residues of Ubr1 and completes the cascade by phosphorylating Tyr277 (Fig. 1 B and C). The Tyr277 residue of Ubr1 is an example of a tyrosine phosphorylation by Mck1, outside of its autophosphorylation activity. We also showed that the initial (priming) phosphorylation of Ubr1 on Ser300 (Fig. 1C) plays a major role in the control of import of di/tripeptides by the N-end rule pathway (Figs. 1C and 5).

Fig. 5.

Summary of main findings. (A) The cascade of Ubr1 phosphorylation. See Fig. 1C for another diagram of this cascade. (B) The Yck1/Yck2 kinases mediate the activity of the amino acid-sensing SPS pathway and the glucose-sensing Snf3/Rgt2 pathway. We found that Yck1/Yck2 also function as “priming” kinases in the Ubr1 phosphorylation cascade (A and Fig. 1C) that involves the Yck1/Yck2 and Mck1 kinases. Stp1 and Stp2 are latent transcription factors, activated through cleavages by Ssy5, that up-regulate, in particular, the expression of the peptide transporter gene PTR2, in a process counteracted by the Cup9 repressor (28). Also shown is the characterized positive-feedback circuit (1, 2) that involves the binding of di/tripeptides with type-1 or -2 destabilizing N-terminal residues (Fig. 1A) to the types-1/2 binding sites of Ubr1, and the resulting allosteric activation of the third binding site of Ubr1 that targets Cup9 for ubiquitylation. This activation, which accelerates Cup9 degradation and thereby up-regulates PTR2, was found to require phosphorylation of Ubr1 on Ser300 by the Yck1/Yck2 kinases.

Phosphorylation of Ubr1 on Tyr277 is up-regulated by an extracellular amino acid such as Trp (Fig. 2H). Trp induces the Ptr2 transporter and thereby up-regulates the import of di/tripeptides (32). The mechanism of Ptr2 induction by Trp was recently found to involve acceleration of the Ubr1-dependent degradation of the Cup9 repressor (4). This acceleration requires the amino acid-sensing SPS (Ssy1-Ptr3-Ssy5) pathway (26, 28, 33). Ssy1, the plasma membrane-embedded amino acid sensor, transduces its interaction with an extracellular amino acid such as Trp into a changed phosphorylation state of Ptr3, an Ssy1-associated protein that functions downstream of Ssy1. The Trp-induced phosphorylation of Ptr3 is mediated by the Ssy1-dependent activation of the Yck1/Yck2 kinases (27, 28). Remarkably, the same kinases were found to phosphorylate Ubr1 on Ser300, thereby priming the rest of Ubr1 phosphorylation cascade (Figs. 1 B and C and 5). Thus, the addition of Trp up-regulates the cascade phosphorylation of Ubr1 through the same Ssy1-mediated activation of the Yck1/Yck2 kinases that also leads to phosphorylation of Ptr3, a component of the SPS pathway (27, 28, 33).

The impaired ability of Ubr1S300A to increase the rate of Cup9 degradation in response to amino acids or type-1 dipeptides can account, at least in part, for the demonstrated impairment of Ubr1S300A in the induction of PTR2 by these effectors (Figs. 3E and 4C; Fig. S4G). In summary, the induction of PTR2 by Trp, a process that involves the SPS pathway and the Ubr1-dependent acceleration of Cup9 degradation (4), requires phosphorylation of Ubr1 on Ser300 by the Yck1/Yck2 kinases. These kinases also play a role in the signaling by glucose in yeast (24), in agreement with the Yck1/Yck2-dependent up-regulation of Ubr1 phosphorylation on Tyr277 by glucose, an effect that is not observed with Ubr1S300A (Fig. 2 F and G). In contrast to the Yck1/Yck2-mediated phosphorylation of Ubr1 on Ser300 that affects both the activity of Ubr1 and the control of peptide import by the N-end rule pathway, the other (primed) phosphorylations of Ubr1 (Fig. 1C) appear to have at most minor effects on the known Ubr1 functions. Thus, a biological role of the post-Ser300 part of Ubr1 phosphorylation cascade (Fig. 1C) remains to be identified. We also found that mutational replacements of Tyr277 by either Ala or Glu (the latter a mimic of phospho-Tyr at this position) converted Ubr1 into a short-lived protein in vivo (Fig. S2 B–E). Surprisingly, a proteasome-inhibitor test with Ubr1pY277 (wild-type Ubr1 phosphorylated on Tyr277) suggested its metabolic stability (Fig. 2D), in contrast to a short in vivo half-life of, for example, Ubr1Y277E (Fig. S2 B–E). It remains to be determined definitively whether the phosphorylation of Ubr1 on Tyr277 can lead to its accelerated degradation in vivo.

Although S. cerevisiae Ubr1 is sequelogous to the mammalian Ubr1/Ubr2 N-recognins (8), the latter lack a sequence that resembles the Tyr277-containing region of S. cerevisiae Ubr1. Nevertheless, a counterpart of the functionally critical Ser300 residue of yeast Ubr1 (Fig. 1C) may well be present in mammalian Ubr1/Ubr2, which have several potential sites of phosphorylation by a CKI-type kinase. In other words, the main discovery of the present work (Figs. 1C and 5) suggests that phosphorylation will be found to regulate N-recognins of multicellular eukaryotes as well.

Methods Summary

For descriptions of materials and methods, including S. cerevisiae strains, plasmids and PCR primers, see SI Text, and Tables S1–S3. Standard techniques, including PCR, were used to construct specific strains and plasmids, including plasmids that encoded Ubr1 mutants. Epitope-tagged Mck1, Ubr1 and their mutant derivatives or GST fusions to Ubr1 fragments were overexpressed in S. cerevisiae or Escherichia coli and purified through steps that included affinity chromatography. Sites of in vivo phosphorylation of Ubr1 in S. cerevisiae were mapped using trypsin-produced fragments of isolated Ubr1 and mass spectrometry (MS). Ab1ScUbr1(1–1140), an antibody that recognized all species of S. cerevisiae Ubr1 and Ab1pY277Ubr1, an antibody to a phosphopeptide that encompassed phospho-Tyr277, were produced in rabbits. All procedures, including the making and characterization of antibodies, the immunoblotting and coimmunoprecipitation assays, pulse–chase assays, and in vitro kinase assays are described in SI Text.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments.

We thank M. Longtine (Oklahoma State University, Stillwater, OK) for pFA6a-KanMX6 and pFA6a-SkHIS3MX6; L. C. Robinson (Louisiana State University, Shreveport, LA) for the LRB906 and LRB756 S. cerevisiae; K. W. Cunningham (Johns Hopkins University, Baltimore) for gsk3Δ S. cerevisiae; M. Snyder (Yale University, New Haven, CT) for a GST-kinase library; and G. Hathaway, J. Zhou, and S. Horvath (California Institute of Technology) for MS analyses and biotin/Tyr277-containing peptides. We thank T. Hunter for comments on the article. We are also grateful to the present and former members of the Varshavsky laboratory, particularly Z. Xia for advice and assistance, J. Sheng for permission to cite unpublished data, and to A. Shemorry for comments on the paper. This study was supported by grants from the National Institutes of Health (GM31530, DK39520, to A.V.), the Sandler Program in Asthma Research (A.V.), and the Ellison Medical Foundation (A.V.).

Footnotes

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

This article contains supporting information online at www.pnas.org/cgi/content/full/0808891105/DCSupplemental.

References

- 1.Turner GC, Du F, Varshavsky A. Peptides accelerate their uptake by activating a ubiquitin-dependent proteolytic pathway. Nature. 2000;405:579–583. doi: 10.1038/35014629. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Du F, Navarro-Garcia F, Xia Z, Tasaki T, Varshavsky A. Pairs of dipeptides synergistically activate the binding of substrate by ubiquitin ligase through dissociation of its autoinhibitory domain. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2002;99:14110–14115. doi: 10.1073/pnas.172527399. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Homann OR, Cai H, Becker JM, Lindquist SL. Harnessing natural diversity to probe metabolic pathways. PLoS Genet. 2005;1:e80. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.0010080. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Xia Z, Turner GC, Hwang C-S, Byrd C, Varshavsky A. Amino acids induce peptide uptake via accelerated degradation of CUP9, the transcriptional repressor of the PTR2 peptide transporter. J Biol Chem. 2008;283:28958–28968. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M803980200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Varshavsky A. The N-end rule: Functions, mysteries, uses. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1996;93:12142–12149. doi: 10.1073/pnas.93.22.12142. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Varshavsky A. Discovery of cellular regulation by protein degradation. J Biol Chem. 2008 doi: 10.1074/jbc.X800009200. in press. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Mogk A, Schmidt R, Bukau B. The N-end rule pathway of regulated proteolysis: Prokaryotic and eukaryotic strategies. Trends Cell Biol. 2007;17:165–172. doi: 10.1016/j.tcb.2007.02.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Tasaki T, Kwon YT. The mammalian N-end rule pathway: New insights into its components and physiological roles. Trends Biochem Sci. 2007;32:520–528. doi: 10.1016/j.tibs.2007.08.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ravid T, Hochstrasser M. Diversity of degradation signals in the ubiquitin-proteasome system. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2008;9:679–689. doi: 10.1038/nrm2468. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kwon YT, et al. An essential role of N-terminal arginylation in cardiovascular development. Science. 2002;297:96–99. doi: 10.1126/science.1069531. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hu R-G, et al. The N-end rule pathway as a nitric oxide sensor controlling the levels of multiple regulators. Nature. 2005;437:981–986. doi: 10.1038/nature04027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hu R-G, Wang H, Xia Z, Varshavsky A. The N-end rule pathway is a sensor of heme. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2008;105:76–81. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0710568105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Xia Z, et al. Substrate-binding sites of UBR1, the ubiquitin ligase of the N-end rule pathway. J Biol Chem. 2008;283:24011–24028. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M802583200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Xie Y, Varshavsky A. The E2–E3 interaction in the N-end rule pathway: The RING-H2 finger of E3 is required for the synthesis of multiubiquitin chain. EMBO J. 1999;18:6832–6844. doi: 10.1093/emboj/18.23.6832. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Varshavsky A. Spalog and sequelog: Neutral terms for spatial and sequence similarity. Curr Biol. 2004;14:R181–R183. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2004.02.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Cai H, Hauser M, Naider F, Becker JM. Differential regulation and substrate preferences in two peptide transporters of Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Eukaryot Cell. 2007;6:1805–1813. doi: 10.1128/EC.00257-06. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Sasaki T, et al. Spatiotemporal regulation of c-Fos by ERK5 and the E3 ubiquitin ligase UBR1, and its biological role. Mol Cell. 2006;24:63–75. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2006.08.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Zenker M, et al. Deficiency of UBR1, a ubiquitin ligase of the N-end rule pathway, causes pancreatic dysfunction, malformations and mental retardation (Johanson-Blizzard syndrome) Nat Genet. 2005;37:1345–1350. doi: 10.1038/ng1681. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Rayner TF, Gray JV, Thorner JW. Direct and novel regulation of cAMP-dependent protein kinase by Mck1p, a yeast glycogen synthase kinase-3. J Biol Chem. 2002;277:16814–16822. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M112349200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Lochhead PA, et al. A chaperone-dependent GSK3beta transitional intermediate mediates activation-loop autophosphorylation. Mol Cell. 2006;24:627–633. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2006.10.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Doble BW, Woodgett JR. GSK-3: Tricks of the trade for a multi-tasking kinase. J Cell Sci. 2003;116:1175–1186. doi: 10.1242/jcs.00384. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.He H, et al. CK2 phosphorylation of SAG at Thr10 regulates SAG stability, but not its E3 ligase activity. Mol Cell Biochem. 2007;295:179–188. doi: 10.1007/s11010-006-9287-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Knippschild U, et al. The casein kinase 1 family: Participation in multiple cellular processes in eukaryotes. Cell Signal. 2005;17:675–689. doi: 10.1016/j.cellsig.2004.12.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Santangelo GM. Glucose signaling in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Microbiol Mol Biol Rev. 2006;70:253–282. doi: 10.1128/MMBR.70.1.253-282.2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Paquin N, Chartrand P. Local regulation of mRNA translation: new insights from the bud. Trends Cell Biol. 2008;18:105–111. doi: 10.1016/j.tcb.2007.12.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Abdel-Sater F, Bakkoury EI, Urrestarazu A, Vissers S, Andre B. Amino acid signaling in yeast: Casein kinase I and the Ssy5 endoprotease are key determinants of endoproteolytic activation of the membrane-bound Stp1 transcription factor. Mol Cell Biol. 2004;24:9771–9785. doi: 10.1128/MCB.24.22.9771-9785.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Liu Z, Thornton J, Spirek M, Butow RA. Activation of the SPS amino acid-sensing pathway in Saccharomyces cerevisiae correlates with the phosphorylation state of a sensor component, Ptr3. Mol Cell Biol. 2008;28:551–563. doi: 10.1128/MCB.00929-07. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Andréasson C, Heessen S, Ljungdahl PO. Regulation of transcription factor latency by receptor-activated proteolysis. Genes Dev. 2006;20:1563–1568. doi: 10.1101/gad.374206. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Hunter T. The age of crosstalk: Phosphorylation, ubiquitination, and beyond. Mol Cell. 2007;28:730–738. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2007.11.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Dornan D, et al. ATM engages autodegradation of the E3 ubiquitin ligase COP1 after DNA damage. Science. 2006;313:1122–1126. doi: 10.1126/science.1127335. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Gallagher E, Gao M, Liu Y-C, Karin M. Activation of the E3 ubiquitin ligase Itch through a phosphorylation-induced conformational change. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2006;103:1717–1722. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0510664103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Fosberg H, Ljungdahl PO. Sensors of extracellular nutrients in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Curr Genet. 2001;40:91–109. doi: 10.1007/s002940100244. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Poulsen P, Leggio LL, Kielland-Brandt MC. Mapping of an internal protease cleavage site in the Ssy5p component of the amino acid sensor of Saccharomyces cerevisiae and functional characterization of the resulting pro- and protease domains by gain-of-function genetics. Eukaryot Cell. 2006;5:601–608. doi: 10.1128/EC.5.3.601-608.2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.