Abstract

Human cytomegalovirus has previously been shown to induce the accumulation of cyclooxygenase-2 RNA, protein, and enzyme activity. High doses of cyclooxygenase inhibitors substantially block viral replication in cultured fibroblasts. However, doses corresponding to the level of drug achieved in the plasma of patients have little effect on the replication of human cytomegalovirus in cultured cells. Here, we demonstrate that two nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs, tolfenamic acid and indomethacin, markedly reduce direct cell-to-cell spread of human cytomegalovirus in cultured fibroblasts. The block is reversed by addition of prostaglandin E2, proving that it results from the action of the drugs on cyclooxygenase activity. Because direct cell-to-cell spread likely contributes importantly to pathogenesis of the virus, we suggest that nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs might help to control human cytomegalovirus infections in conjunction with other anti-viral treatments.

Keywords: cyclooxygenase inhibitors, human cytomegalovirus pathogenesis

Human cytomegalovirus (HCMV) is a ubiquitous β-herpes virus. Although HCMV infection is usually asymptomatic in healthy children and adults, it is a significant cause of morbidity and mortality in newborn and immunocompromised individuals (1).

There are three systemic drugs approved for HCMV treatment: ganciclovir and its prodrug valganciclovir, foscarnet, and cidofovir (2). Unfortunately, each has potential for significant toxicity. Ganciclovir can cause bone marrow suppression (3), whereas foscarnet (4) and cidofovir (5, 6) are nephrotoxic. Further, cross-resistance has been observed for the drugs (7), because all of them ultimately target the viral DNA polymerase. Finally, because of their potential to cause toxicity, they are not used in combination, although therapies with different mechanisms of action are highly desirable. There is a need for additional agents for treatment of HCMV, and maribavir, a benzimidazole riboside that inhibits the HCMV UL97 kinase (8), is being evaluated in clinical trials. Earlier work from our laboratory (9) and others (10) has identified cyclooxygenase (COX) enzymes as a possible target for treatment of HCMV disease.

Infections by several viruses, including representatives of all three subfamilies of human herpesviruses, have been reported to induce the expression of the COX enzymes (11, 12). These enzymes, also known as prostaglandin synthases, catalyze the rate-limiting step in the prostanoid portion of the eicosanoid synthetic pathway. This subpathway produces prostaglandins (PGs), prostacyclins, and thromboxanes (13, 14). Specifically, COX enzymes convert arachidonic acid to PGH2 through a PGG2 intermediate. There are two cox genes, encoding COX-1 and -2; a third isoform (COX-3) is the product of a splice variant of COX-1 (15). COX-1 is constitutively expressed in many tissues and is involved in a variety of functions, such as cytoprotection of the gastric mucosa, regulation of renal blood flow, bone metabolism, nerve growth and development, wound healing, and platelet aggregation (16–18). Although COX-2 is constitutively expressed in the brain, kidney, and testes, it is induced in most other tissues by proinflammatory or mitogenic agents (19).

HCMV infection induces arachidonic acid metabolism (20, 21). Infection of fibroblasts strongly induces COX-2 as well as other constituents of the eicosanoid pathway (22–24), and large amounts of PGE2 appear in the medium (9, 10). Rhesus cytomegalovirus (RhCMV) encodes a COX-2 homolog with a role in cell tropism, emphasizing the importance of these enzymes in cytomegalovirus pathogenesis (25, 26), and previous studies have shown that several COX inhibitors can interfere with HCMV multiplication at high nonphysiological concentrations (9, 10, 27, 28). So far, however, the mechanistic role of COX activity and its products in the virus life cycle has remained uncertain (29).

Here, we demonstrate that two COX inhibitors, tolfenamic acid and indomethacin, substantially block cell-to-cell spread by HCMV in fibroblasts. Importantly, the drugs block direct spread in cultured cells at doses that can be achieved in the plasma of patients.

Results

Tolfenamic Acid Inhibits the Replication of HCMV, Interfering with Viral Gene Expression and Protein Localization.

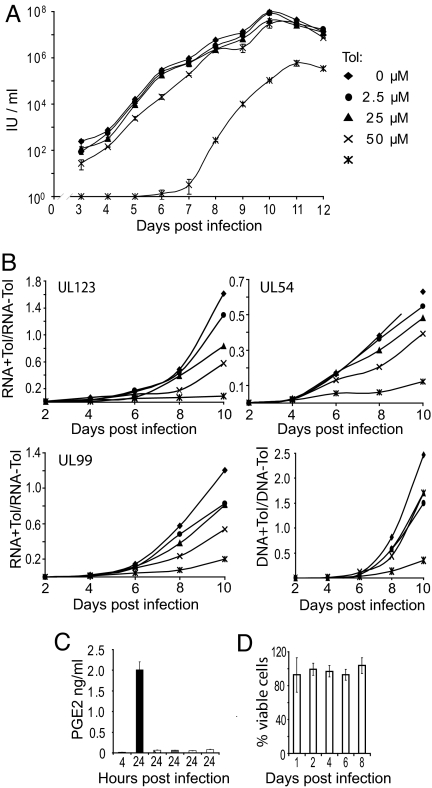

We previously showed that high doses of indomethacin or experimental COX-2 inhibitors inhibit the accumulation of the immediate-early 2 (IE2) mRNA and block the production of infectious progeny (9). We tested how another nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drug, tolfenamic acid, influenced virus replication. It seemed possible that it would inhibit HCMV growth more strongly than the inhibitors we had studied, because tolfenamic acid has been reported not only to inhibit COX activity and the synthesis of prostaglandins (30), but also to antagonize prostaglandin receptor function (31) and leukotriene biosynthesis (32, 33). We first tested the effect of tolfenamic acid on the production of extracellular virus after infection of fibroblasts at a multiplicity of 0.01 pfu/cell. A high, nonphysiological dose of the drug (100 μM) substantially delayed the production of infectious progeny and reduced the final yield of virus by a factor of approximately 20, and lower doses of tolfenamic acid had modest effects on virus growth (Fig. 1). Under normal use, the drug reaches a plasma concentration of approximately 20 μM (30), and a dose of 25 μM in the culture medium reduced the yield by a factor of 2.

Fig. 1.

At doses achieved during normal drug use in humans, tolfenamic acid inhibits the production of HCMV progeny to a limited extent. (A) Effect of tolfenamic acid (Tol) on the accumulation of extracellular virus. Fibroblasts were treated with drug for 24 h before infection with HCMV at a multiplicity of 0.01 pfu/cell. Cells received fresh medium with drug every 24 h. Cell-free virus samples were harvested at the indicated times, and infectious units (IU) was assayed by indirect immunofluorescence assay of IE1-positive cells at 24 h after infection of fibroblasts. Cultures that did not receive drug (w/o drug) were treated with DMSO (6.4 mM), the concentration used to deliver the highest level of drug tested. Results are from two independent experiments, each of which was assayed in duplicate. (B) Tolfenamic acid inhibits viral RNA and DNA accumulation in a dose-dependent manner. The accumulation of representative viral RNAs (UL123 immediate-early, UL54 early and UL99 late), was assayed by qRT-PCR, and the accumulation of viral DNA was assayed by qPCR. Assays were performed at the indicated times after infection in the presence or absence of drug. Symbols representing drug concentrations are as in panel A. Ratios (viral nucleic acids/cellular GAPDH in the presence versus absence of drug) were calculated from one experiment assayed in duplicate, and similar results were obtained in an additional experiment. (C) Tolfenamic acid treatment substantially inhibited the production of PGE2. Cells received no drug (solid bars) or 100 μM tolfenamic acid (open bars) for indicated time periods, and the production of PGE2 was determined by immunoassay. Results are from two independent experiments, each of which was assayed in duplicate. (D) Tolfenamic acid (100 μM) is not toxic to fibroblasts. Cultures received fresh medium with drug every 24 h, and the percentage of viable cells was determined daily for a total of eight days. The results are from a single experiment, which was repeated three times with similar results.

To evaluate the site in the replication cycle at which tolfenamic acid acts, we assayed the accumulation of virus-coded nucleic acids. Drug treatment reduced the accumulation of an immediate-early (UL123), early (UL54), and late (UL99) RNA as well as viral DNA in a dose-dependent manner (Fig. 1B). The reduction in immediate-early gene expression could be responsible for the later effects. In control experiments, the drug blocked PGE2 accumulation at all concentrations tested (Fig. 1C), and the highest dose of drug (100 μM) had no detectable effect on cell viability over a period of 8 days (Fig. 1D).

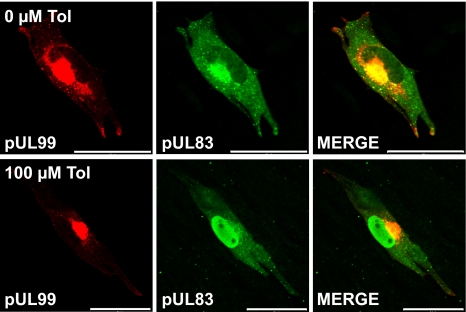

In addition to inhibiting viral gene expression, tolfenamic acid perturbed the localization of the pUL83 virion protein. Normally, pUL83 accumulates in the nucleus during the early phase of infection, and moves to the cytoplasm during the late phase (34). As expected, pUL83 was localized to the cytoplasm at 72 hpi in the absence of drug, but it was exclusively nuclear when infected cells were maintained in 100 μM tolfenamic acid (Fig. 2). At intermediate concentrations of the drug, infected cells contained both nuclear and cytoplasmic pUL83 (data not shown). A second tegument protein, pUL99, was properly localized at 72 hpi in the cytoplasm at all drug concentrations tested (Fig. 2). Several additional virus-coded proteins, pUL32 and pUL86, were found to be mislocalized, whereas pUL123 was properly localized (data not shown). A high dose of indomethacin (500 μM) induced a similar mislocalization of pUL83 late after infection (data not shown).

Fig. 2.

Tolfenamic acid causes the mislocalization of some viral proteins. Fibroblasts that did not receive drug (Upper) were treated with DMSO at the concentration (6.4 mM) used for drug treatment. Tolfenamic acid (100 μM)-treated cultures received drug 24 h before infection and were fed with fresh medium and drug every 24 h thereafter. Cells were assayed for pUL99 (red) and pUL83 (green) localization by indirect immunofluorescence at three days after infection. (Scale bars, 50 μm.)

In sum, tolfenamic acid interferes with the accumulation of virus-coded mRNAs and DNA, causes the mislocalization of several viral proteins, and reduces the production of virus progeny. The effects are dose-dependent, and a significant virus-inhibitory effect was noted only at the highest dose of drug tested.

Tolfenamic Acid Inhibits Direct Cell-to-Cell Spread of HCMV.

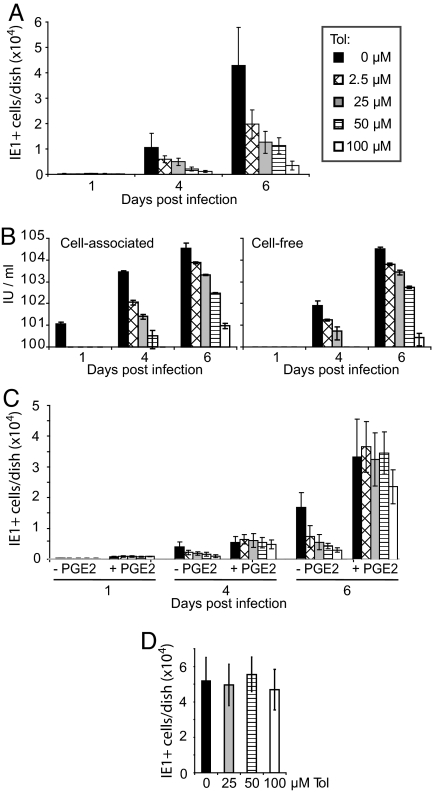

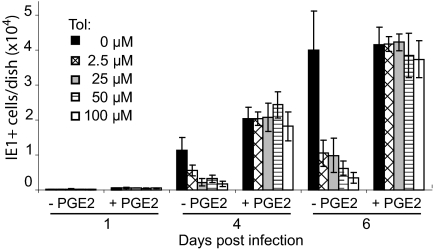

The reduction in cell-free virus observed in drug-treated cultures could result from the production of less virus in each infected cell or a failure of the virus to spread efficiently. We tested the possibility that tolfenamic acid inhibits virus spread by infecting fibroblasts at a multiplicity of 0.01 pfu/cell and visualizing IE1-expressing cells after various time intervals by immunofluorescence. At 4 and 6 days after infection, the number of fluorescent cells was reduced by the drug in a dose-dependent manner (Fig. 3A), and the decrease in the number of infected cells was reflected in the amount of cell-associated and cell-free virus produced in the cultures (Fig. 3B). The addition of PGE2 overcame the inhibitory effect of tolfenamic acid (Fig. 3C), demonstrating that the block to spread resulted from the inhibition of COX activity and is not an off target effect of the drug. Reduced spread could result from a drug-induced refractory state, that is, continuous drug treatment might make cells resistant to infection. This possibility was tested by treating cells for 6 days with tolfenamic acid, and then testing whether they could be infected by assaying for IE1 immunofluorescence (Fig. 3D). Pretreatment with the highest dose tested (100 μg/ml) had no effect on the efficiency with which HCMV infected the cells.

Fig. 3.

Tolfenamic acid inhibits spread by HCMV. Cultures that did not receive drug were treated with DMSO at the concentration (6.4 mM) used to deliver the highest level of drug tested. Results are from two independent experiments, each of which was assayed in duplicate. (A) Tolfenamic acid (Tol) reduces HCMV spread in a dose-dependent manner. Drug was added to cultures 24 h before infection at a multiplicity of 0.01 pfu/cell, and fibroblasts received fresh medium and drug every 24 h. Cells were assayed for IE1 expression by indirect immunofluorescence at the indicated times after infection. (B) Effect of tolfenamic acid on the accumulation of virus. Fibroblasts were treated with drug for 24 h before infection with HCMV at a multiplicity of 0.01 pfu/cell. Cells received fresh medium with drug very 24 h. Cell-associated and cell-free virus samples were harvested at the indicated times, and infectious units (IU) were assayed by indirect immunofluorescence assay of IE1-positive cells at 24 h after infection of fibroblasts. (C) Exogenously added PGE2 restores normal viral replication in the presence of a Cox inhibitor. Tolfenamic acid was added at indicated concentrations, either alone or together with 1 μM PGE2 at 24 h before infection at a multiplicity of 0.01 pfu/cell. Cells received fresh medium with drug and supplement every 24 h. Cells were assayed for IE1 expression by indirect immunofluorescence at the indicated times after infection. (D) Fibroblasts do not become refractive to infection with cell-free virus after extended treatment with tolfenamic acid. Cultures received fresh drug at the indicated concentrations and medium every 24 h for six days. Then they were infected and maintained in the presence of drug for an additional 24 h, after which cultures were assayed for IE1 expression by indirect immunofluorescence.

There are two modes by which viruses can spread. Extracellular virus can be produced that is able to bind and enter an uninfected cell, or virus can spread directly to adjacent cells without passing although a cell-free stage. Cytomegalovirus can spread in cultures of fibroblasts by both mechanisms [(35) and references therein]. In the experiment described above (Fig. 3), the number of single IE1-positive cells increased, but the foci of adjacent IE1-positive cells were smaller after treatment with tolfenamic acid (data not shown). This observation is consistent with a drug-induced block to direct cell-to-cell spread without inhibition of spread through the production of cell-free virus, which can infect cells at a distance from the cell in which it is produced.

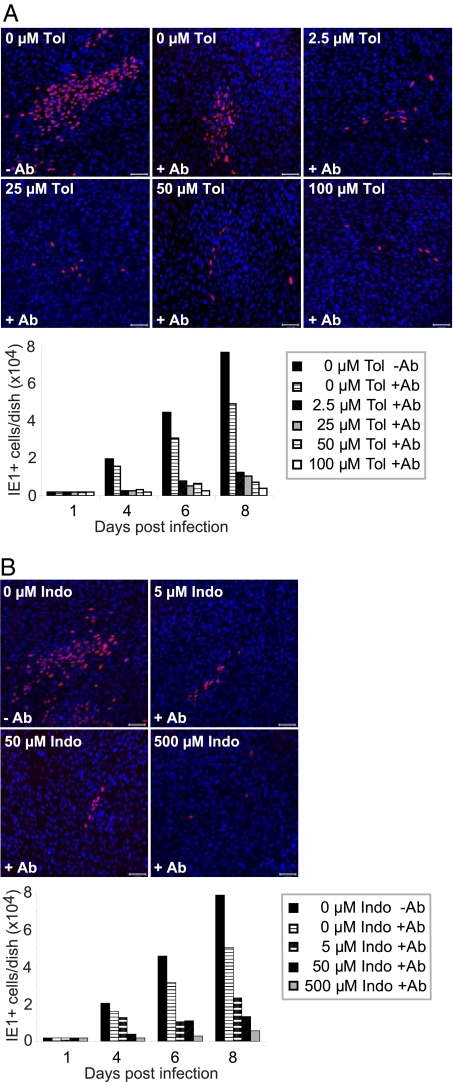

To test this interpretation, we monitored spread in the presence of hyperimmune HCMV-specific globulin. The hyperimmune globulin was titrated so that it neutralized 105 infectious units of HCMV (data not shown), more than the amount produced in the infected cultures in the absence of drug. Fibroblasts were infected at a multiplicity of 0.01 pfu/cell, and globulin was added immediately thereafter. The addition of antibody in the absence of drug reduced the number of fluorescent cells by ≈25%, and even the lowest concentration of tolfenamic acid tested (2.5 μM) markedly reduced the size of infected foci (Fig. 4A Upper), and reduced the total number of IE1-expressing cells by a factor of approximately 5 (Fig. 4A Lower). We performed the same assay using indomethacin to inhibit COX activity, and it also reduced the size of foci and the number of IE1-expressing cells (Fig. 4B). Finally, the addition of PGE2 reversed the effect of tolfenamic acid, allowing the development of normal size foci (data not shown) with normal numbers of IE-expressing cells in the presence of neutralizing antibody (Fig. 5).

Fig. 4.

Cox inhibitors reduce HCMV cell-to-cell spread. (A) Tolfenamic acid (Tol) and (B) Indomethacin (Indo) reduce HCMV cell-to-cell spread in a dose-dependent manner. Drug at indicated concentrations and, where indicated, neutralizing antibody (1% vol/vol) were added to cultures 24 h before infection at a multiplicity of 0.01 pfu/cell. Cultures received fresh medium, drug and neutralizing antibody every 24 h. Cells were assayed for IE1 expression by indirect immunofluorescence at the indicated times after infection. Upper panels: micrographs chosen to illustrate the sizes of infected cell (IE1-expressing, red) foci at 4 days after infection; lower panels: total number of infected cells per dish (2 dishes total) at the indicated times after infection. (Scale bars, 100 μm.)

Fig. 5.

Exogenously added PGE2 overcomes the inhibition of viral spread within fibroblast cultures by tolfenamic acid. Fibroblast cultures were treated with neutralizing antibody (1% vol/vol) throughout the course of the experiment. Tolfenamic acid (Tol) was added at indicated concentrations, either alone or together with 1 μM PGE2 at 24 h before infection at a multiplicity of 0.01 pfu/cell. Cells received fresh medium with drug and supplement every 24 h. In two independent experiments, the number of infected cells was determined by counting IE1-expressing cells at the indicated times after infection.

We conclude that COX inhibitors substantially block the ability of HCMV to spread directly from an infected cell to an adjacent cell.

Discussion

Many viruses can spread directly from cell to cell, a strategy that allows them to escape attack by extracellular defenses such as neutralizing antibodies and complement. For example, measles virus transfers subviral particles from infected to uninfected cells by way of fusion-mediated cytoplasmic interconnections (36, 37). HIV-1 is more efficiently passed from cell to cell rather than by infection with virions (38). Recently, it has been shown that several different retroviruses, including HIV-1, cross filopodia that extend from the uninfected to infected cells (39). These intercellular bridges are stabilized by interaction of cell-coded viral receptors at the tips of filopodia with viral envelope glycoprotein on the infected cell. Herpes simplex virus has been shown to localize to epithelial cell junctions, where it apparently moves between cells with minimal or no exposure to extracellular fluids (40). This might result from the interaction of the viral glycoprotein, gD, on the membrane of infected cells and its receptor, nectin-1, on uninfected cells at the junctions (41).

HCMV also can spread directly from cell to cell. Clinical isolates of the virus that have been passaged in culture to a limited extent remain highly cell-associated (42, 43); a clinical strain of the virus can spread efficiently in the presence of neutralizing antibody (44), consistent with direct cell-to-cell spread. Virus-expressed GFP and an injected dye have been shown to move from infected to adjacent uninfected fibroblasts, demonstrating that cytoplasmic contents can be exchanged from cell to cell (35); and electron microscopy has documented microfusion events that could provide a path for the movement of HCMV from infected endothelial cells to leukocytes in cell culture (45). Finally, a pUL99-deficient HCMV mutant accumulates tegument-containing capsids in the cytoplasm, failing to assemble infectious particles (46); but it nevertheless efficiently spreads from cell to cell in the presence of neutralizing antibody (47).

Under normal use, tolfenamic acid (30, 48) and indomethacin (48, 49) reach plasma levels of ≈20 μM and ≈5 mM, respectively, and these concentrations of drug have only a modest effect on the yield of HCMV in cultured fibroblasts (Fig. 1A) (9, 10). However, both drugs substantially inhibit the growth of infected cell foci in cultures of fibroblasts at physiologically relevant doses (Fig. 4), leading us to conclude that the drugs block direct cell-to-cell spread. Importantly, antibody-resistant spread is restored by addition of PGE2 (Fig. 5), a downstream product of COX activity, demonstrating that the inhibition of spread is not an off target effect.

How do the inhibitors block cell-to-cell spread? COX inhibitors block the maturation and movement of α-herpesvirus capsids (28) and HCMV capsids (data not shown) from the nucleus to cytoplasm and induce the mislocalization of several HCMV proteins. Either of these perturbations could block spread, but, in contrast to the inhibition of cell-to-cell spread, both require high levels of COX inhibitors, making it unlikely that either abnormality is the basis for the block to spread. Further, we have observed that a pUL83-deficient mutant can spread normally from cell-to-cell in the presence of neutralizing antibody (data not shown), reinforcing the view that the mislocalization of pUL83 alone is not responsible for the block to spread. Possibly, the spread defect caused by low doses of COX inhibitors results from mislocalization of a different viral gene product or combination of products. Alternatively, the reduction in the accumulation of RNAs observed with low doses of tolfenamic acid (Fig. 1B) could provide a clue. The modestly reduced accumulation of viral gene products, or a greater effect on a viral product we have not assayed, might perturb an aspect of cellular physiology that is required for efficient cell-to-cell spread but not for assembly and release of infectious virions from the cell.

Would inhibition of direct cell-to-cell spread attenuate an HCMV infection? Because clinical isolates of the virus remain highly cell associated when first introduced into cell culture, it is very likely that they spread directly from cell-to-cell in vivo. This mode of spread would fit well with reports that HCMV-specific cytotoxic T cells can control HCMV disease in allogeneic transplant recipients (50, 51).

Despite an important role for direct cell-to-cell spread during infection, hyperimmune HCMV-specific globulin has been reported to ameliorate the consequences of HCMV infection during pregnancy (28, 52) and transplantation (53, 54). Antibodies can act by neutralizing cell-free virus as well as by enhancing an antibody-dependent cell-mediated antiviral response. COX inhibitors might prove to be a useful adjunct to antibody treatment in the management of HCMV disease.

Although the effect of COX inhibitors on HCMV disease has not yet been tested, there are indications that this class of drugs might help to control herpes simplex virus disease. Celecoxib, a COX-2 inhibitor, can suppress herpes simplex virus reactivation in a mouse model of latency (55). In human studies, topical application of indomethacin or mefenamic acid diminished the size and severity of recurrent oral and genital lesions induced by herpes simplex viruses (56), and oral administration of indomethacin or ibuprofen reduced the frequency of reactivation and the severity of lesions in patients with a history of frequent recurrences (57).

In conclusion, our results predict that COX inhibitors might have significant therapeutic utility for the control of HCMV infections, most likely in conjunction with existing therapies.

Materials and Methods

Cells and Viruses.

Primary human foreskin fibroblasts (HFFs) at passage 6 to 15 were maintained in Dubecco's modified Eagle's medium (DMEM) supplemented with 10% FBS. An isolate of HCMV strain AD169, BADwt, was derived from an infectious clone of the viral genome (58), and propagated on MRC-5 fibroblasts (ATCC). Infectious yields were determined by fluorescent focus assays, in which MRC-5 cells were infected with dilutions of virus and IE1-positive cells were quantified 24–48 later.

Drug Treatment of Cells.

Cells were pretreated with medium containing the indicated amount of tolfenamic acid, N-(2-methyl-3-chlorophenyl) anthranilic acid (Cayman Chemical); indomethacin, 1-(4-chlorobenzoyl)-5-methoxy-2-methyl-3-indoleacetic acid (Sigma-Aldrich), or solvent (DMSO; Sigma-Aldrich) for 24 h before inoculation with virus for 2 h at 37°C. After that, the inoculum was replaced by fresh drug-containing medium, which was replaced with fresh drug-containing medium every 24 h. Cell viability in the presence of drugs or solvent was assessed by CellTiter 96 AQueous One Solution Cell Proliferation Assay according to the manufacturer's instructions (Promega). To analyze viral growth kinetics in the presence of drugs, cells were pretreated for 24 h and then infected at a multiplicity of 0.01 pfu/cell. At various times after infection, medium (cell-free virus) or cells (cell-associated virus) were collected, virus was released from cells by three freeze-thaw cycles, and infectivity was determined by fluorescent focus assay.

Analysis of Viral Nucleic Acids and Proteins.

Total cellular RNA was isolated from infected cells with TRIzol reagent (Invitrogen). Viral RNA accumulation was monitored by quantitative real-time RT-PCR (qRT-PCR) as described previously (59) by using a 7900HT sequence detection system with SDS software version 2.1 (Applied Biosystems). Primers were as follow: UL123 (IE1) (forward primer 5′GCCTTCCCTAAGACCACCAAT3′, reverse primer 5′ATTTTCTGGGCATAAGCCATAATC3′); UL54 (forward primer 5′GTGTGCAAC TACGAGGTA3′, reverse primer 5′GAC AGC ACG TTG GTT ACA3′); UL99, (forward primer 5′GAGGACAAGGCTCCGAAAC3′, reverse primer 5′CTT TGCTGATGGTGGTGATG3′). Results were normalized to glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase RNA levels (forward primer 5′ACCCACTCCTCCACCTTTGAC3′, reverse primer 5′CTGTTGCTGTAGCCAAATTCGT3′). A dissociation curve was generated for each primer pair to confirm the amplification of a single product. Viral DNA accumulation was monitored by qPCR assay of total cell DNA with UL123-specific primers as described previously (60).

Viral proteins were detected by indirect immunofluorescence as described previously (46). Mouse monoclonal antibodies (mAb) to the IE1 protein [1B12, (61)], pUL83 [8F5, (62)], and pUL99 [10B429, (46)] served as primary antibodies, and goat anti-mouse Alexa Fluor 488/546 conjugate (Molecular Probes) was the secondary antibody. Nuclei were identified by staining DNA with 4′,6-diamidino-2-phenylindole (DAPI). Microscopy and image acquisition was carried out with a Zeiss LSM510 confocal microscope.

Acknowledgments.

We thank R. Whitley (University of Alabama School of Medicine) for helpful comments. This work was supported by National Institutes of Health Grant CA85786 and European Union “TargetHerpes” Grant LSHG-CT-2006-037517.

Footnotes

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- 1.Mocarski ES, Shenk T, Pass RF. Cytomegaloviruses. Philadelphia, PA: Lippincott Williams and Wilkins; 2007. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Biron KK. Antiviral drugs for cytomegalovirus diseases. Antiviral Res. 2006;71:154–163. doi: 10.1016/j.antiviral.2006.05.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Noble S, Faulds D. Ganciclovir. An update of its use in the prevention of cytomegalovirus infection and disease in transplant recipients. Drugs. 1998;56:115–146. doi: 10.2165/00003495-199856010-00012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Deray G, et al. Foscarnet nephrotoxicity: Mechanism, incidence and prevention. Am J Nephrol. 1989;9:316–321. doi: 10.1159/000167987. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.De Clercq E, Holy A. Acyclic nucleoside phosphonates: A key class of antiviral drugs. Nat Rev Drug Discov. 2005;4:928–940. doi: 10.1038/nrd1877. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ho ES, Lin DC, Mendel DB, Cihlar T. Cytotoxicity of antiviral nucleotides adefovir and cidofovir is induced by the expression of human renal organic anion transporter 1. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2000;11:383–393. doi: 10.1681/ASN.V113383. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Field AK, Biron KK. “The end of innocence” revisited: Resistance of herpesviruses to antiviral drugs. Clin Microbiol Rev. 1994;7:1–13. doi: 10.1128/cmr.7.1.1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Biron KK, et al. Potent and selective inhibition of human cytomegalovirus replication by 1263W94, a benzimidazole L-riboside with a unique mode of action. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2002;46:2365–2372. doi: 10.1128/AAC.46.8.2365-2372.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Zhu H, Cong JP, Yu D, Bresnahan WA, Shenk TE. Inhibition of cyclooxygenase 2 blocks human cytomegalovirus replication. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2002;99:3932–3937. doi: 10.1073/pnas.052713799. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Speir E, Yu ZX, Ferrans VJ, Huang ES, Epstein SE. Aspirin attenuates cytomegalovirus infectivity and gene expression mediated by cyclooxygenase-2 in coronary artery smooth muscle cells. Circ Res. 1998;83:210–216. doi: 10.1161/01.res.83.2.210. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Reynolds AE, Enquist LW. Biological interactions between herpesviruses and cyclooxygenase enzymes. Rev Med Virol. 2006;16:393–403. doi: 10.1002/rmv.519. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Steer SA, Corbett JA. The role and regulation of COX-2 during viral infection. Viral Immunol. 2003;16:447–460. doi: 10.1089/088282403771926283. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Narumiya S, Sugimoto Y, Ushikubi F. Prostanoid receptors: Structures, properties, and functions. Physiol Rev. 1999;79:1193–1226. doi: 10.1152/physrev.1999.79.4.1193. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Smith WL, DeWitt DL, Garavito RM. Cyclooxygenases: Structural, cellular, and molecular biology. Annu Rev Biochem. 2000;69:145–182. doi: 10.1146/annurev.biochem.69.1.145. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Chandrasekharan NV, et al. COX-3, a cyclooxygenase-1 variant inhibited by acetaminophen and other analgesic/antipyretic drugs: Cloning, structure, and expression. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2002;99:13926–13931. doi: 10.1073/pnas.162468699. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.DeWitt DL, Smith WL. Primary structure of prostaglandin G/H synthase from sheep vesicular gland determined from the complementary DNA sequence. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1988;85:1412–1416. doi: 10.1073/pnas.85.5.1412. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.DeWitt DL, Smith WL. Cloning of sheep and mouse prostaglandin endoperoxide synthases. Methods Enzymol. 1990;187:469–479. doi: 10.1016/0076-6879(90)87053-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Funk CD, Funk LB, Kennedy ME, Pong AS, Fitzgerald GA. Human platelet/erythroleukemia cell prostaglandin G/H synthase: CDNA cloning, expression, and gene chromosomal assignment. FASEB J. 1991;5:2304–2312. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Chen N, Reis CS. Distinct roles of eicosanoids in the immune response to viral encephalitis: Or why you should take NSAIDS. Viral Immunol. 2002;15:133–146. doi: 10.1089/088282402317340288. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.AbuBakar S, Boldogh I, Albrecht T. Human cytomegalovirus stimulates arachidonic acid metabolism through pathways that are affected by inhibitors of phospholipase A2 and protein kinase C. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 1990;166:953–959. doi: 10.1016/0006-291x(90)90903-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.AbuBakar S, Boldogh I, Albrecht T. Human cytomegalovirus. Stimulation of [3H] release from [3H]-arachidonic acid prelabelled cells. Arch Virol. 1990;113:255–266. doi: 10.1007/BF01316678. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Browne EP, Wing B, Coleman D, Shenk T. Altered cellular mRNA levels in human cytomegalovirus-infected fibroblasts: Viral block to the accumulation of antiviral mRNAs. J Virol. 2001;75:12319–12330. doi: 10.1128/JVI.75.24.12319-12330.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Simmen KA, et al. Global modulation of cellular transcription by human cytomegalovirus is initiated by viral glycoprotein B. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2001;98:7140–7145. doi: 10.1073/pnas.121177598. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Zhu H, Cong JP, Mamtora G, Gingeras T, Shenk T. Cellular gene expression altered by human cytomegalovirus: Global monitoring with oligonucleotide arrays. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1998;95:14470–14475. doi: 10.1073/pnas.95.24.14470. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Hansen SG, Strelow LI, Franchi DC, Anders DG, Wong SW. Complete sequence and genomic analysis of rhesus cytomegalovirus. J Virol. 2003;77:6620–6636. doi: 10.1128/JVI.77.12.6620-6636.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Rue CA, et al. A cyclooxygenase-2 homologue encoded by rhesus cytomegalovirus is a determinant for endothelial cell tropism. J Virol. 2004;78:12529–12536. doi: 10.1128/JVI.78.22.12529-12536.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Tanaka J, Ogura T, Iida H, Sato H, Hatano M. Inhibitors of prostaglandin synthesis inhibit growth of human cytomegalovirus and reactivation of latent virus in a productively and latently infected human cell line. Virology. 1988;163:205–208. doi: 10.1016/0042-6822(88)90249-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Ray N, Bisher ME, Enquist LW. Cyclooxygenase-1 and -2 are required for production of infectious pseudorabies virus. J Virol. 2004;78:12964–12974. doi: 10.1128/JVI.78.23.12964-12974.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Mocarski ES., Jr. Virus self-improvement through inflammation: No pain, no gain. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2002;99:3362–3364. doi: 10.1073/pnas.072075899. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Pedersen SB. Biopharmaceutical aspects of tolfenamic acid. Pharmacol Toxicol. 1994;75(Suppl 2):22–32. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0773.1994.tb01992.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Vapaatalo H, Parantainen H, Linden IB, Hakkarainen H. Headache, New Vistas; Proceedings of the Joint Meeting of the Italian Headache and the Scandinavian Migraine Societies; Florence: 1977. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Moilanen E, Alanko J, Seppala E, Vapaatalo H. Effects of antirheumatic drugs on leukotriene B4 and prostanoid synthesis in human polymorphonuclear leukocytes in vitro. Agents Actions. 1988;24:387–394. doi: 10.1007/BF02028298. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Moilanen E, Alanko J, Juhakoski A, Vapaatalo H. Orally administered tolfenamic acid inhibits leukotriene synthesis in isolated human peripheral polymorphonuclear leukocytes. Agents Actions. 1989;28:83–88. doi: 10.1007/BF02022985. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Sanchez V, Greis KD, Sztul E, Britt WJ. Accumulation of virion tegument and envelope proteins in a stable cytoplasmic compartment during human cytomegalovirus replication: Characterization of a potential site of virus assembly. J Virol. 2000;74:975–986. doi: 10.1128/jvi.74.2.975-986.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Digel M, Sampaio KL, Jahn G, Sinzger C. Evidence for direct transfer of cytoplasmic material from infected to uninfected cells during cell-associated spread of human cytomegalovirus. J Clin Virol. 2006;37:10–20. doi: 10.1016/j.jcv.2006.05.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Moll M, Pfeuffer J, Klenk HD, Niewiesk S, Maisner A. Polarized glycoprotein targeting affects the spread of measles virus in vitro and in vivo. J Gen Virol. 2004;85:1019–1027. doi: 10.1099/vir.0.19663-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Firsching R, Buchholz CJ, Schneider U, Cattaneo R, ter Meulen V, Schneider-Schaulies J. Measles virus spread by cell–cell contacts: Uncoupling of contact-mediated receptor (CD46) downregulation from virus uptake. J Virol. 1999;73:5265–5273. doi: 10.1128/jvi.73.7.5265-5273.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Jolly C, Kashefi K, Hollinshead M, Sattentau QJ. HIV-1 cell to cell transfer across an Env-induced, actin-dependent synapse. J Exp Med. 2004;199:283–293. doi: 10.1084/jem.20030648. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Sherer NM, Lehmann MJ, Jimenez-Soto LF, Horensavitz C, Pypaert M, Mothes W. Retroviruses can establish filopodial bridges for efficient cell-to-cell transmission. Nat Cell Biol. 2007;9:310–315. doi: 10.1038/ncb1544. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Johnson DC, Webb M, Wisner TW, Brunetti C. Herpes simplex virus gE/gI sorts nascent virions to epithelial cell junctions, promoting virus spread. J Virol. 2001;75:821–833. doi: 10.1128/JVI.75.2.821-833.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Krummenacher C, Baribaud I, Eisenberg RJ, Cohen GH. Cellular localization of nectin-1 and glycoprotein D during herpes simplex virus infection. J Virol. 2003;77:8985–8999. doi: 10.1128/JVI.77.16.8985-8999.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Sinzger C, et al. Modification of human cytomegalovirus tropism through propagation in vitro is associated with changes in the viral genome. J Gen Virol. 1999;80(Pt 11):2867–2877. doi: 10.1099/0022-1317-80-11-2867. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Yamane Y, Furukawa T, Plotkin SA. Supernatant virus release as a differentiating marker between low passage and vaccine strains of human cytomegalovirus. Vaccine. 1983;1:23–25. doi: 10.1016/0264-410x(83)90008-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Sinzger C, et al. Effect of serum and CTL on focal growth of human cytomegalovirus. J Clin Virol. 2007;38:112–119. doi: 10.1016/j.jcv.2006.11.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Gerna G, et al. Human cytomegalovirus replicates abortively in polymorphonuclear leukocytes after transfer from infected endothelial cells via transient microfusion events. J Virol. 2000;74:5629–5638. doi: 10.1128/jvi.74.12.5629-5638.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Silva MC, Yu QC, Enquist L, Shenk T. Human cytomegalovirus UL99-encoded pp28 is required for the cytoplasmic envelopment of tegument-associated capsids. J Virol. 2003;77:10594–10605. doi: 10.1128/JVI.77.19.10594-10605.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Silva MC, Schroer J, Shenk T. Human cytomegalovirus cell-to-cell spread in the absence of an essential assembly protein. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2005;102:2081–2086. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0409597102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Barnett J, et al. Purification, characterization and selective inhibition of human prostaglandin G/H synthase 1 and 2 expressed in the baculovirus system. Biochim Biophys Acta. 1994;1209:130–139. doi: 10.1016/0167-4838(94)90148-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Sifton DW. Physicians' Desk Reference. 57 Edition. Montvale: Thomson; 2003. [Google Scholar]

- 50.Walter EA, et al. Reconstitution of cellular immunity against cytomegalovirus in recipients of allogeneic bone marrow by transfer of T-cell clones from the donor. N Engl J Med. 1995;333:1038–1044. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199510193331603. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Einsele H, et al. Infusion of cytomegalovirus (CMV)-specific T cells for the treatment of CMV infection not responding to antiviral chemotherapy. Blood. 2002;99:3916–3922. doi: 10.1182/blood.v99.11.3916. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Nigro G, Adler SP, La Torre R, Best AM. Passive immunization during pregnancy for congenital cytomegalovirus infection. N Engl J Med. 2005;353:1350–1362. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa043337. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Valantine HA. Prevention and treatment of cytomegalovirus disease in thoracic organ transplant patients: Evidence for a beneficial effect of hyperimmune globulin. Transplant Proc. 1995;27:49–57. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Bonaros N, Mayer B, Schachner T, Laufer G, Kocher A. CMV-hyperimmune globulin for preventing cytomegalovirus infection and disease in solid organ transplant recipients: A meta-analysis. Clin Transplant. 2008;22:89–97. doi: 10.1111/j.1399-0012.2007.00750.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Gebhardt BM, Varnell ED, Kaufman HE. Inhibition of cyclooxygenase 2 synthesis suppresses Herpes simplex virus type 1 reactivation. J Ocul Pharmacol Ther. 2005;21:114–120. doi: 10.1089/jop.2005.21.114. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Inglot AD, Woyton A. Topical treatment of cutaneous herpes simplex in humans with the non-steroid antiinflammatory drugs: Mefenamic acid and indomethacin in dimethylsulfoxide. Arch Immunol Ther Exp (Warsz) 1971;19:555–566. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Wachsman M, Aurelian L, Burnett JW. The prophylactic use of cyclooxygenase inhibitors in recurrent herpes simplex infections. Br J Dermatol. 1990;123:375–380. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2133.1990.tb06298.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Yu D, Smith GA, Enquist LW, Shenk T. Construction of a self-excisable bacterial artificial chromosome containing the human cytomegalovirus genome and mutagenesis of the diploid TRL/IRL13 gene. J Virol. 2002;76:2316–2328. doi: 10.1128/jvi.76.5.2316-2328.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Terhune SS, Schroer J, Shenk T. RNAs are packaged into human cytomegalovirus virions in proportion to their intracellular concentration. J Virol. 2004;78:10390–10398. doi: 10.1128/JVI.78.19.10390-10398.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Feng X, Schroer J, Yu D, Shenk T. Human cytomegalovirus pUS24 is a virion protein that functions very early in the replication cycle. J Virol. 2006;80:8371–8378. doi: 10.1128/JVI.00399-06. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Zhu H, Shen Y, Shenk T. Human cytomegalovirus IE1 and IE2 proteins block apoptosis. J Virol. 1995;69:7960–7970. doi: 10.1128/jvi.69.12.7960-7970.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Nowak B, et al. Characterization of monoclonal antibodies and polyclonal immune sera directed against human cytomegalovirus virion proteins. Virology. 1984;132:325–338. doi: 10.1016/0042-6822(84)90039-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]