Abstract

Knowledge is limited regarding decision-making about antiretroviral treatment (ART) from the patient’s perspective. This substudy of a longitudinal study of psychobiologic aspects of long-term survival, conducted in 2003, compares the rationales of HIV-positive individuals (n = 79) deciding to take or not to take ART. Inclusion criteria were HIV/AIDS symptoms, or CD4 nadir less than 350, or viral load greater than 55,000. Those not meeting any criteria for receiving ART (2/2003 U.S. DHHS treatment guidelines) were excluded. Diagnosis was on average 11 years ago; 36% were female, 42% African American, 28% Latino, 24% white, and 6% other. Qualitative content analysis of semistructured interviews identified 10 criteria for the decision to take or not to take ART: CD4/viral load counts (87%), quality of life (85%), knowledge/beliefs about resistance (66%), mind–body beliefs (65%), adverse effects of ART (59%), easy-to-take regimen (58%), spirituality/worldview (58%), drug resistance (41%), experience of HIV/AIDS symptoms (39%), and preference for complementary/alternative medicine (17%). Participants choosing not to take ART (27%) preferred complementary/alternative medicine (r = 0.43, p < 0.001)1, perceived a better quality of life without ART (r = 0.32, p < 0.004), and weighted avoidance of adverse effects of ART more heavily (r = 0.24, p < 0.030) than participants taking ART (73%). Demographic characteristics related to taking ART were having a partner (r = 0.31, p < 0.008) and having health insurance (r = 0.26, p < 0.040). Decisions to take or not to take ART depend not only on patient medical characteristics, but also on individual beliefs about ART, complementary/alternative medicine, spirituality, and mind–body connection. HIV-positive individuals declining treatment place more weight on alternative medicine, avoiding adverse effects and perceiving a better quality of life through not taking ART.

INTRODUCTION

There is limited knowledge about how people with HIV/AIDS (PLWH) make their decisions about antiretroviral treatment (ART).1–10 These decisions are particularly difficult because both physicians and patients of-ten do not know when the best point is to start, stop, or change ART.11,12 Recommendations of treatment guidelines are mainly based on disease severity. Physicians reported that in decision-making about ART they weighted their perception of patient’s likelihood of adherence as heavily as disease severity.13 Patients’ perspectives, knowledge, and experience has for too long been an untapped resource in understanding decision-making about treatment.5,14 Research in other chronic diseases suggests that understanding patients perspectives could enhance both the quality of patients’ care and ultimately their quality of life.14

Several studies have examined why PLWH decline the offer of ART.1,2,4,6–8 However, the sample sizes in theses studies have been very small with a main focus on gay men. They found that patients considered more than surrogate markers (i.e., CD4, viral load) and HIV/AIDS symptoms in their decision: doubts about personal necessity, concerns about adverse effects of ART, quality-of-life issues, distrust of ART and the medical system, preference for complementary and alternative medicine (CAM), and the attitude toward death were all associated with the decision to decline ART.1,4,7

In addition to the small sample size and focus on gay men, these studies only examined PLWH declining ART. There is not much knowledge about the decisional criteria of PLWH accepting ART. Our initial hypothesis was that patient’s rationale for taking ART might differ from their rationale for not taking ART. Thus, there is a lack of comparison between PLWH who decline and those who accept ART.1,4,15 The major purpose of this study was to determine why PLWH who have been offered ART choose to take or not to take ART. Another purpose was to discuss implications of the findings for clinical practice.

A qualitative approach was chosen because we felt that not enough was known on how PLWH make treatment decisions. This is important, because there are no existing questionnaires to identify patients’ decisional criteria. Other advantages of the qualitative approach are that findings can be used to generate suggestions for physicians to assist their patients in treatment decision-making.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Study population and sampling

The study was conducted as a substudy. The longitudinal parent study on Psychology of Health and Long Survival with HIV/AIDS16–19 started in March 1997 and recruited a diverse paid volunteer sample from AIDS organizations, doctors’ offices, and community events in Florida. The parent study included HIV-positive persons with CD4 levels between 150 and 500. The main exclusion criteria were the following: Having a past or current AIDS defining symptom (Centers for Disease Control [CDC] category C), active substance dependence, or active psychotic symptoms. This sub-study was conducted between February and September 2003, and investigated 79 PLWH, who should have been offered ART according to the U.S. Department of Health and Human Service (DHHS) treatment guidelines20: (1) PLWH with symptoms ascribed to HIV-infection; (2) asymptomatic PLWH with CD4 cells less than 350/mm3 or plasma HIV RNA levels greater than 55,000 copies per milliliter (by reverse transcription-polymerase chain reaction [RT-PCR] or bDNA). The participants in the substudy did not differ from those in the parent study on any demographic variables, except that participants with active substance dependence (i.e., who had relapsed) and or who had developed AIDS-defining events were not excluded. All participants of the parent study in which ART was not yet indicated according to the U.S. DHSS guidelines20 were excluded from the substudy. The sample was representative of PLWH in Florida with respect to gender and ethnic groups (Table 1).

Table 1.

Demographic and medical characteristics (n = 79)

| Characteristic | |

|---|---|

| Mean age years (SD) | 42.03 (7.88) |

| Gender (% female) | 35.4% |

| Sexual orientation (% heterosexual) | 53.2% |

| Ethnicity, % | |

| African American | 41.8% |

| Latino | 27.8% |

| White | 24.1% |

| Other | 6.3% |

| Income level (% less than $10,000/year) | 44.4% |

| Education level (% high school or less) | 36.8% |

| Employment status (% employed) | 36.7% |

| Partnership (% having a partner) | 30.2% |

| Drug use (% past month) | |

| Marihuana (nonprescribed) | 26.0% |

| Cocaine | 16.3% |

| Other recreational drugs | 16.6% |

| Insurance coverage (% insurance/program) | 92.4% |

| Antiretroviral treatment (% taking) | 73.4% |

| Complementary/alternative medicine (% use) | 50.6% |

| Mean viral load copies per milliliter (SD) | 37,858 (83,125) |

| Mean CD4 cells/mm3 at the interview (SD) | 347.00 (227.65) |

| Mean CD4 cells/mm3 nadir (SD) | 149.95 (93.99) |

| Symptoms of AIDS (% CDC Category C) | 13.9% |

| Mean years since HIV diagnosis (SD) | 11.14 (4.15) |

SD, standard deviation; CDC, Centers for Disease Control.

Study design and procedures

This study is designed as a cross-sectional study that is primarily qualitative. The local Institutional Review Board approved this study and all participants gave written informed consent. Self-report questionnaires on demographics (Table 1) were sent out by mail approximately 2 weeks prior to the interview. At our research center, the participants completed their medical information, the ACTG-Adherence questionnaire21 and a Physical Symptoms Checklist (asking for the presence or absence of CDC category B and C symptoms) with the researcher. Blood was drawn to assess CD4 cell counts using CD4-Flow cytometry (Coulter XL-MCL, Beckman Coulter Inc., Fullerton, CA) and HIV-1 viral load using RT/PCR (Roche Amplicor HIV-1 MONITOR® Test (Roche, Diagnostics, Indianapolis, IN), measuring viral loads at levels as low as 400 HIV-1 RNA copies per milliliter). The participants then underwent the interview, being asked what decisions they made about ART over the last year and why they currently made their decision to take or not to take ART. Later in the interview, participants were also asked about the importance of potential decisional criteria (such as specific surrogate markers, adverse effects, quality of life, resistance testing, pill burden, lifestyle, and spirituality/worldview). At the end of the interview, they were asked an open-ended question on other personally important factors. In addition, participants were asked to share their thoughts about the cause of drug resistance. The duration of the interviews was between 30–60 minutes. Participants were reimbursed $50 for each visit at the study center.

Qualitative content analysis

All semistandardized interviews were performed by one of two trained interviewers and were audiotaped and transcribed. The transcribed interviews were analyzed with the method of qualitative content analysis.22,23 This approach offers an advantage over other qualitative approaches in that it allows both quantitative and qualitative operations. This method defines itself as an empirical, methodologically controlled analysis of texts, following content analytical rules and step-by-step models without rash quantification.22,23 The word was the smallest unit of analysis. In the first step, during inductive category development, the most comprehensive interviews were worked through to develop tentative categories, and to formulate a criterion of definition derived from the research questions. After analysis of 21 interviews, the analysis reached theoretical saturation. The categories were reduced, selected, and grouped into a hierarchical system of thematic fields. Next, a formative check of reliability and validity took place to detect and revise ill-defined categories. This resulted in a system to code the reasons for the decision made about ART with category definitions, anchor examples, and coding rules for each category determining and illustrating under exactly what circumstances a text passage is coded for a specific category (Table 2). Next, independent interrater reliability of two raters (Cohen’s κ coefficient for categorical data and Kendall’s τ for ordinal data24) was calculated for the first 21 interviews. In general, coefficients above 0.70 are considered acceptable).25 All independent interrater reliability coefficients ranged between 0.83 and 1.0 (p < 0.001). In the next step, during deductive category application, all 79 interviews were coded based on the coding agenda by 3 trained team members in consensual ratings.26 Each of the 79 interviews was rated by 3 raters, who first looked at the interview independently and then discussed their decision in the group. Quantitative aspects, such as consensual validity and frequencies of the coded categories were calculated. The coding agenda, frequencies, illustrating examples, and interrater reliability were summarized in a meta-matrix (Table 2).27

Table 2.

Meta-matrix of the reasons for the decision made about art

| Thematic field | Categories | Frequency (%) (n = 79) | Category definition | Anchor examples | Interrater reliability of 2 raters (n = 21) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CD4 count/viral load | Important | 61 (77.2%) | CD4 count and viral load are important criteria for the decision | I cannot sit and wait until viral load goes up and up.… I would like to get to the point where my T-cells are at above 400. | τb = 0.94a |

| SE = 0.04 | |||||

| Partially important | 8 (10.1%) | Only one (CD4 or viral load) is important for the decision, but the other is not. | My understanding about T-cell count is that this really does not really mind that much about the progress or non-progress of the disease.… I need the medications to stop the viral replication, which is the only benefit that I receive from them. | ||

| Not important | 10 (12.7%) | CD4 count and viral load are not important criteria for the decision | They (CD4 and viral load) are numbers, and if I let those numbers drive me nuts, I’m the one that’s going to be nuts. | ||

| QOL | Impact on: | Rate how the person perceives the effect of the decision on quality of life | Physical: I’m feeling miserable because of the drugs. It’s not a good quality of life. Basically they’re probably keeping me alive, and that’s why I keep taking them. But if I stop them, I just feel so much better. | τb = 0.86a | |

| Physical QOL | SE = 0.10 | ||||

| Positive | 58 (73.4%) | ||||

| None | 16 (20.3%) | ||||

| Negative | 5 (6.3%) | ||||

| Psychosocial QOL | Psychosocial: The medication, it gives me hope. Compared to when I first started I’m doing a lot more with people, with my family, than before. | τb = 91a | |||

| Positive | 45 (57.0%) | SE = 0.07 | |||

| None | 22 (27.8%) | ||||

| Negative | 12 (15.2%) | ||||

| Beliefs about drug resistance | Causality | Rate if person believes that nonadherence is a cause of resistance to ART, or does not know what resistance is. | Yes: (Being non-adherent) is like playing with fire. | κ = 1.0a | |

| belief | Possible: I think (resistance is) partly from not adhering to the regimen enough. I think it’s more just the virus itself, mutates to fight it. | SE = <0.01 | |||

| Yes | 40 (50.6%) | ||||

| Possible | 12 (15.2%) | No: My opinion on resistance is that, pretty much how my body is reacting to a certain drug, resistance is not just the virus mutating.… I look at it as if your body is showing you a sign: “Hey! What you are putting into me is something very toxic..… You gave me this and that is the end result of it”. | |||

| No | 4 (5.1%) | ||||

| No knowledge | 23 (29.1%) | ||||

| No knowledge: Resistance? What is that? Can I take it? | κ = 0.89a | ||||

| Body–mind beliefs | Present | 28 (36%) | Rate if person states a belief or partial belief in body–mind connection | Yes: With all my healers behind me who taught me the body’s ability to heal itself.… I have even achieved undetectable viral load in the course of my study here. (She is ART naïve). Nobody even could believe it. So I did it once. I will do it again. | SE = 0.11 |

| Yes | 16 (20%) | ||||

| Partially | 35 (44%) | ||||

| No | Yes, partially: My belief is that God will work it out and I wouldn’t have to take the medicine. | ||||

| Adverse effects | Absent | 20 (25.3%) | If adverse effects are present, rate how well they are tolerated | 1) I had a fall dream (on Efavirenz), like if I was stoned. I enjoyed it actually, very much. | τb = 1.0a |

| Present, tolerance | 59 (74.7%) | 2) At the beginning I had a little bit of nausea, like normal, and felt kind of muscle aches, but they went away.… Maybe my body adjusts to it. | SE = <0.01 | ||

| 1) Very well | 1 | ||||

| 2) Well | 9 | 3) At the beginning it was a little hard, but then it went away. I had a lot of stomach pain, but I was a little tough about it … and kept doing the medicine. | |||

| 3) Moderate | 9 | ||||

| 4) Not well | 40 | 4) (ART) was killing me. I was health bound from the stomach up so I had diarrhea and I lost twenty pounds. | |||

| Anticipated | Rate if adverse effects of medication are anticipated | Yes: I am glad that I did not jump on the band wagon, because you know everyone having diabetes and neuropathy and lipodystrophy. I am the only girl, who still has a butt (laughs). | κ = 1.0a | ||

| Yes | 25 (31.6%) | SE = <0.01 | |||

| No | 54 (68.4%) | ||||

| Reason to stop/change | Rate if person states that experienced or anticipated adverse effects are a reason to stop or change ART | N/A: I haven’t had any side effects. | κ = 1.0a | ||

| N/A | 12 (15.2%) | No: I had diarrhea and that was the most severe side effect. (I continued), because I have to take the medication that the doctor gave me. | SE = <0.01 | ||

| No | 20 (25.3%) | ||||

| Yes, change | 24 (30.4%) | Yes, change: I blacked out (on ART), but they said it may be the nausea. That’s another reason why I had to change, because I could have hit my head and killed myself. | |||

| Yes, stop | 23 (29.1%) | Yes, stop: I don’s feel anything while taking it (ART). It is important, if at any time I start to develop side effects or whatever, it is my choice to stop taking it. | |||

| Spirituality/ worldview | Important | Rate if spirituality or world view are important in the decision to take ART | Spirituality: You have to put god first and the medication a second. He (god) says in his words, acknowledge him and he would direct your path.… He said to me in his voice, when he is talking to you, when I went to the doctor, and I say: “Hello, is this the best medicine? Help me to find something else that is better for me, because I do not want to take all these pills.” | κ = 1.0a | |

| Spirituality | 38 (48%) | SE = <0.01 | |||

| Worldview | 8 (10%) | Worldview: I am totally optimistic upon life, absolutely, in the most positive way. However science proved me wrong (my viral load was shooting up during drug holidays). I am still optimistic about new medication to bring it back to the level where I want it to be. I believe I am the most positive person in the world. | |||

| None of both | 33 (42%) | ||||

| Easy to take | Easy regimen important | Rate if person states that an easy to take regimen is important | Yes: First of all I just wanted to get a lot less pills. | κ = 1.0a | |

| Yes | 46 (58.2%) | SE = <0.01 | |||

| No | 33 (41.8%) | ||||

| Resistance test | Resistance test | Categorize reported status of drug-resistance testing | Present: Results from a resistance test came back and it changed the medication … based on the resistance test. | κ = 1.0a | |

| Present | 23 (29.1%) | SE = <0.01 | |||

| Absent | 6 (7.6%) | Absent: (I have had a resistance test done). No, I don’t have any resistance. | |||

| Pending | 3 (3.8%) | Waiting for results: We will have the results from the resistance test. | |||

| Not tested | 47 (59.4%) | Not tested: I was thinking about a resistance test to see how well it is still working for me. | |||

| HIV/AIDS symptoms | Experienced | Rate if HIV-symptoms have been experienced | Yes: The type of symptoms I had, fatigue, night sweats, loss of appetite, I don’t want to be bothered with this. | κ = 0.83a | |

| Yes | 31 (39.2%) | SE = 0.16 | |||

| No | 48 (60.8%) | ||||

| Complementary or alternative medicine | Preference | Rate if person states to prefer complementary or alternative medicine | Yes: I did a lot of research and I found out, that if I build my immune system on its own I can do what the drugs are attempting to do without the toxicity and the adverse effects.… I have been doing alternative, complementary therapy vigorously since that time period when I found out. | κ = 1.0a | |

| Yes | 13 (16.5%) | SE = <0.01 | |||

| No | 66 (83.5%) |

Coefficient is significant at level p < 0.001

QOL, quality of life; ART, antiretroviral treatment; SE, standard error.

Satistical analysis

Participants taking ART and those not taking ART were compared on demographic and medical parameters. The associations between taking/not taking ART and the coded categories, and demographic and medical parameters were calculated. Independent t tests were used for normally distributed ordinal and interval data. χ2 analysis and the Fischer’s exact test (indicated as pf) were used for nominal and skewed ordinal data. Pearson’s coefficients were calculated for the associations between continuous data. SPSS version 12 statistical software (SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL) was used for statistical evaluation).

RESULTS

Demographic and medical characteristics

Table 1 summarizes the demographic and medical characteristics of all 79 participants of this study. The sample was diverse, containing a good representation of gender, sexual orientation, ethnic groups, and socioeconomic status. All participants were offered ART by their physicians. Half of them reported the use of CAM such as yoga, nutritional supplements, relaxation, biofeedback, visual imagery, massage, and other mind–body medicine. Overall, the participants were diagnosed with HIV on average 11 years ago, and the majority (74%) had CD4 cells below 200/mm3 at some point in time, but only a few (14%) had AIDS-defining events prior to this substudy. According to the Physical Symptoms Checklist, 20% experienced HIV-related symptoms over the past 6 months. HIV/AIDS symptoms were underreported in the interviews compared to the Physical Symptoms Checklist and the physician verification of category C symptoms. The reports of HIV/AIDS symptoms in the interview were not significantly correlated with the self-reported category B symptoms on the Physical Symptoms Checklist and the physician verified category C symptoms (r = 0.13, p = 0.273). At the interview, CD4 counts ranged between 8–921 cells/mm3, and the maximal viral load detected was 611,682 copies per milliliter. Not skipping medications over the past month was reported by 37 (64 %) and skipping ART within the past month was reported by 21 (36%) of the 58 participants taking ART. Adverse effects, being away from home, having a change in daily routine, being busy with other things, and simply forgetting were the six main reasons for nonadherence.

Differences between participants taking ART and those not taking ART in demographic and medical characteristics

At the interview, 58 (73%) participants were taking ART (55 [69%] highly active ART, 3 (4%) combination therapy) and 21 (27%) were not taking ART. Over the past year, of the 58 participants taking ART, 22 (38%) had maintained the same regimen, whereas 28 (48%) had changed their combination (mainly switching protease inhibitors), and 8 (14%) had restarted ART after an interruption ranging from 2 weeks to 2 years (M = 6.31 ± 9.16). Of the 21 participants not taking ART, 5 (24%) were ART-naïve and 16 (76%) had currently stopped treatment for a mean duration of 7.61 ± 12.58 months, ranging from 1 week up to 4 years.

Participants taking ART were significantly more likely to have a partner than those not taking ART (χ2(1,79)7.47, odds ratio [OR] = 8.27, pf = 0.008) and were also more likely to have health insurance or a drug access program covering the costs of ART (χ2(1,79) = 5.35, OR = 4.62, pf = 0.04). Only 6 (8%) participants did not have health insurance coverage or a drug access program covering the costs of ART. Although not having health insurance was statistically related to not taking ART, only one participant reported not taking ART because he had no health insurance. Two participants without health insurance took ART and had some coverage of the costs from drug access programs. Three participants without health insurance decided not to take ART because they preferred CAM.

As expected, participants taking ART had a significantly lower viral load log compared to participants not taking ART (t77 = 6.61, 95% confidence interval [CI] = 8,473–90,314; p <0.001). However, of the 58 participants taking ART, only 52% achieved an undetectable viral load. Participants taking ART versus those not taking ART did not differ significantly on CD4 cells/mm3 at the interview (p = 0.085), CD4 nadir (p = 0.86), HIV-related symptoms over the past 6 months (pf = 1.000), AIDS-defining events in the past (pf = 0.470), and years since HIV-diagnosis (p = 0.392).

It should be noted that the 5 ART-naïve individuals may differ from ART-experienced participants. Their main reason to decline the offer of ART was the preference for CAM and the fear of adverse effects of ART. Preliminary findings suggest that the ART-naïve participants, compared to ART-experienced participants, made use of a greater variety of CAM (r = 0.31, p = 0.004), had a higher income (r = 0.032, p = 0.017), but were less likely to have health insurance (χ2(1,79) = 0.99, OR 4.61, pf = 0.040). However, the number of ART-naïve participants in this study was so small that testing for differences between ART-naïve participants and ART-experienced participants was underpowered.

Criteria for the decision made about ART

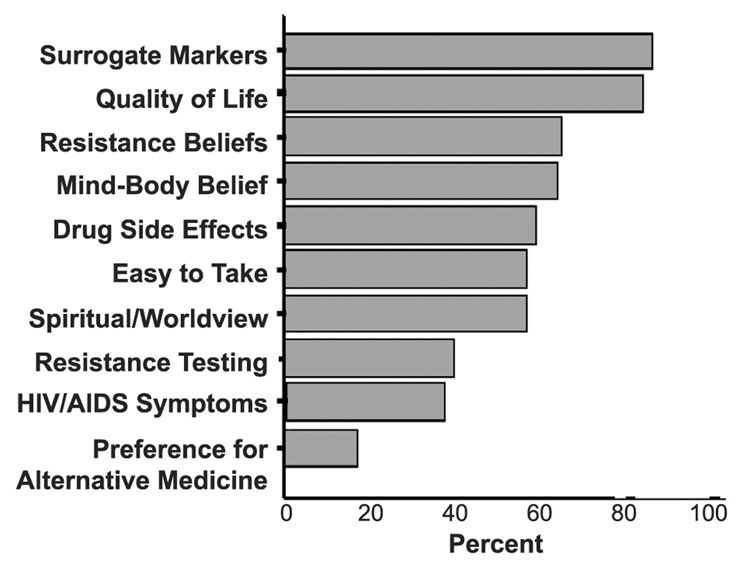

The qualitative content analysis of the interviews revealed 10 thematic fields that patients stated as reasons for their decision to take or not to take ART. The results of the qualitative content analysis are summarized in a meta-matrix27 (Table 2) and illustrated in Figure 1:

Surrogate markers were the most important criterion, considered by 87% of the participants, whereas 13% did not consider them as important.

Better quality of life was the second important criterion. The decision about ART had a positive impact on quality of life in 85% (of which 47% of participants reported improvements in both physical and psychosocial function). Only 15% rated no benefit.

Beliefs about resistance: 66% believed in a link between nonadherence and drug resistance, whereas only 5% did not believe that drug resistance was a consequence of nonadherence, and 29% had no knowledge of resistance.

Mind–body beliefs: When asked about the criteria for their decision about ART, 65% spontaneously mentioned a belief in mind–body connection, whereas 35% did not.

Adverse effects: 60% considered changing/ stopping ART for experienced/anticipated adverse effects, whereas 25% did not; and 15% did not experience/anticipate adverse effects.

Easy to take regimen: 58% spontaneously mentioned the importance of an easy to take regimen, whereas 42% did not. However, only 4 (7%) of the 58 participants taking ART had to take their regimen more than twice daily.

Spirituality/worldview: 58% of the participants considered spirituality/worldview in their decision about ART, whereas 42% participants did not. Considering spirituality in the treatment decision could lead to the acceptance of treatment (“I strongly believe that not taking medication is a sin.”), as well as in the rejection of ART (“I do not have faith in medicine. I put my hands in God.”)

Drug resistance: 41% reported being tested for drug resistance, and 59% did not. According to the U.S. DHSS guidelines,20 resistance testing should have been done in 33 participants because of a viral load above 1000 copies per milliliter after 6 months on ART despite reporting good adherence (>95% on the ACTG adherence questionnaire21); but only 19 (58%) of the 33 participants on a failing regimen were tested.

Experience of HIV/AIDS symptoms: According to the interviews, 39% experienced HIV/AIDS symptoms, whereas 61% did not.

Preference for CAM: 17% mentioned spontaneously a preference for CAM, whereas 83% did not. However, 51% participants used CAM. The preference for CAM was significantly correlated with a mind-body belief (r = 0.34, p = 0.002) and the importance of spirituality/world view (r = 0.24, p = 0.035).

FIG. 1.

Frequencies of the reasons for the decision about antiretroviral treatment (ART): Important/partial important surrogate markers, better physical/psychosocial quality of life, belief/partial belief in mind–body connection (spontaneously stated), belief in link/possible link between adherence and resistance, change/stop ART for adverse effects, easy-to-take regimen important (spontaneously stated), consider spirituality/worldview, drug resistance test performed, experience of HIV/AIDS symptoms, preference for complementary/alternative medicine (spontaneously stated) (n = 79).

The consensual validity of categories (κ or τb) ranged between 0.97–1.00.

Individual reasons for the decision about ART that were not captured in the categorization were: Loss of health insurance, active substance use, U.S. immigration restrictions, communication problems, social comparison, being a peer educator, being a parent, the empowerment of saying no, the attitude toward death, social stigma through lipoatrophy, running out of treatment options, treating a progressing hepatitis B coinfection with ART, and wanting to stay alive for the family.

Differences between people taking and not taking ART

Three criteria were significantly correlated with taking or not taking ART:

Participants not taking ART preferred more CAM than participants taking ART (r = −0.43, p < 0.001).

Participants deciding not to take ART reported a positive impact on psychosocial quality of life (r = −0.32, p = 0.004).

Anticipated adverse effects were listed as a reason for not starting ART in all 5 participants who were ART-naïve. Of the 74 ART-experienced participants, those who decided to take ART tolerated adverse effects better than who decided to cease ART (r = −0.26, p = 0.030). However, of the 33 experienced adverse treatment effects that were reported in the interviews, there were no significant differences between the experience of adverse effects between participants taking ART and those not taking ART. Except that there is a trend for lipoatrophy to be reported more frequent in PWHA stopping ART than in those taking ART (Fischer’s exact test pf < 0.064).

There were no significant differences between participants taking/not taking ART regarding the other seven reasons (surrogate markers [p = 0.599], easy-to-take regimen [p = 0.352], resistance testing [p = 0.073], knowledge/beliefs about resistance [p = 0.302], HIV/AIDS symptoms [p = 0.054], spirituality/worldview [p = 0.532], and mind–body beliefs [p = 0.968]). Thus, the belief in a body–mind connection and the individual spiritual beliefs were not associated with a higher likelihood to take or not to take ART.

Ethnic and gender disparities in treatment knowledge and resistance testing

The awareness of the importance of surrogate markers in decision-making about ART and knowledge of resistance is one indicator of treatment knowledge. Surrogate markers were considered significantly less important by African-Americans than by Latinos, whites, and other ethnic groups (t77 = 2.83, 95% CI = 0.13–0.74, p = 0.006). Knowledge about resistance was significantly related to education (r = 0.37, p = 0.001), income (r = 0.31, p = 0.006), ethnicity (t77 = 3.40, 95% CI = 0.14–0.53, p = 0.001), and gender (t77 = 3.18, 95% CI = 0.12–0.53, p = 0.002). Only 43% (9/21) of women and 67% (8/12) of men of African American origin (who usually had a lower income and education) had knowledge of resistance, compared to 71% (5/7) of women and 87% (34/39) of men of white, Latino, or other ethnic origins. In the 33 participants for whom resistance testing should have been done according to the U.S. DHSS guidelines (i.e., their viral load exceeded 1000 copies per milliliter after 6 months on ART),20 performance of resistance testing was correlated with education (r = 0.64, p < 0.001), income (r = 0.54, p = 0.001), sexual orientation (t77 = 5.34, 95% CI = 0.43–0.97, p < 0.001), ethnicity (t77 = 2.79, 95% CI = 0.12–0.77, p = 0.009), and gender (t77= 3.19, 95% CI = 0.18–0.83, p = 0.004). Of these 33 participants, all 13 (100%) gay men were tested, compared to 25% (3/12) of the African American women, and 38% (3/8) of the other heterosexual men and women.

Finally, in the 33 patients who needed resistance testing, knowledge of resistance testing was significantly correlated with performance of resistance testing (r = 0.37, p = 0.034).

DISCUSSION

To our knowledge, this is the first study comparing rationales for PLWH deciding to take or not to take ART. The main finding of this study is that PLWH deciding not to take treatment emphasize three criteria more strongly than those deciding to take ART: the preference for CAM, avoiding adverse effects of ART, and the perceived benefit in psychosocial quality of life through not taking ART. All other criteria did not differ.

Another important finding of the study is the importance of recognizing that existential issues such as mind–body beliefs and spiritual beliefs are used by approximately half of the PLWH in making decisions about treatment. These beliefs can be used both in the decision to take as well as in the decision not to take treatment. Of particular note, sometimes patient’s spiritual belief system or belief in a mind-body connection is in conflict with the recommendation of a physician (e.g., people feeling that they do not need ART because they believe that the body can heal itself). As such, physicians need to be aware of and ask about the patient’s perspective on these issues.

To take or not to take ART—patient’s rationale

The decision to take or not to take ART is in constant flux, and varies according to individually important criteria. Thus, we found that a significant proportion of participants taking ART had changed or interrupted treatment over the past year. Physicians need to be aware of the constant dynamic in patient’s decision-making, because patient’s who have decided to take ART today may alter their decision in the future depending on their individual cost-benefit equation. The decision about whether to take ART or not was based on 10 reasons that will be discussed below.

Surrogate markers

Many but not all participants considered surrogate markers as important in their decision about ART. Although considering them as important, many initiated ART at lower CD4 cells than clinical guidelines recommended. During the time this study was conducted, the U.S. DHSS guidelines20 recommended starting ART when CD4 cells were below 350 cells/mm3. Three quarters of the participants reported a CD4 nadir below 200 cells/mm3, and the remaining one quarter a CD4 nadir between 200 to 350 cells/mm3. One month after the study ended, the U.S. DHSS guidelines20 lowered the cutoff point to start ART below 200 CD4 cells/mm3. There is remaining uncertainty among experts about the optimal time to initiate ART in asymptomatic people with a viral load below 100,000 copies per milliliter with CD4 counts between 200 to 350 CD4 cells/mm3, but there is agreement that ART initiation should be recommended if CD4 counts declined below 200 cells/mm3, and deferred if CD4 cells are above 350 cells/mm3.12,28,29 For physicians, it is important to be aware that patients, even though they are aware of the importance of maintaining their immune function, may often prefer to defer treatment.

Similar to results of other studies,1,4,7,8 some felt that surrogate markers were too abstract or too far removed from how they felt. Our results suggest that it is important for physicians to ask all patients, especially African-Americans, about their view of surrogate markers in decision-making about ART to ensure that patients understand the goals of ART.

Quality of life

Most of the participants perceived that their decision about ART benefited their quality of life. In particular, participants believed that they would improve their psychosocial quality of life by declining to take ART, which is similar to results of other studies. 1,4,7,8 The short-term benefit in quality of life may be at the risk of renewed immunologic deterioration. 30 Thus, it is important to assess the patient’s perception of the impact of the decision about ART on quality of life and to negotiate a treatment plan that achieves both goals: improvement of quality of life and preservation of immune function.

Knowledge and beliefs about resistance

Similar to other studies in the United States,8,31 almost one third of the participants had no knowledge of resistance. In the present study, lack of knowledge of resistance was particularly prevalent in African American women with low socioeconomic status. This may be one of the reasons for the lower rates of adherence in African American32,33 and female populations.34 Patients who agreed strongly that nonadherence would lead to resistance had significantly better adherence.34 Physicians should ensure that patients understand the relationship between resistance and nonadherence. However, physicians spend on average only 13 minutes giving basic adherence counseling when starting a new ART.35 Rather, physicians reported that they were less willing to prescribe ART in former injection drug users and African American men, expecting that they are less likely to adhere to treatment,13 despite that research suggests that drug use is not a deterrence to ART adherence.36

Mind–body beliefs

Interestingly, two thirds of the participants spontaneously mentioned a belief or partial belief in a mind–body connection. Mind–body medicine is an approach to healing that hypothesizes that thoughts, beliefs, and emotions affect health.37 Improvement of immune function in HIV has been found with both stress management interventions, 38–40 although effect and sample sizes in these studies are small. Because patient’s often view mind–body medicine as an integral part of HIV treatment, physicians need to ask what mind–body approaches their patients are using, and how patients’ mind–body beliefs are effecting their decision to take or not to take ART. A belief in a mind–body connection may discourage some PLWH to take ART, in particular those who perceived the need to take ART as a failure of them in not being able to control the disease, whereas others felt that their “mind-power” helped them to deal with adverse effects of the medication, such as nausea or lipodystrophy.

Adverse effects

It is important to note that the participants who stopped ART tolerated adverse effects less well than participants who continued treatment. This and other studies found that adverse effects were an important reason for both declining ART1,4,7,8 and not adhering to ART.41 Physicians may inform patients in advance of possible adverse effects, assess how patients cope with adverse effects at each visit, and provide treatment for adverse effects even beginning with the first prescription.

Easy to take regimen

To ensure optimal adherence, the regimen should be as simple as possible.20 Although this study suggests that a considerable proportion of participants did not consider the complexity of a regimen as an important aspect, this might be because most patients were already on a simplified regimen. Another study found that once-daily treatments are not a golden bullet for improved adherence; when patients were asked to evaluate ART regimens, once-daily regimens were not, overall, anticipated to promote adherence to a greater extent than some of the twice-daily regimens.42

Spirituality and worldview

More than half of the participants considered spirituality/worldview in their decision about ART. Some felt supported by their spiritual beliefs to take ART (e.g., they felt empowered by their spiritual beliefs to cope with the adverse effects of medication, or felt that not taking the best possible treatment was a “sin”), whereas others named their spiritual beliefs as a reason not to take ART (e.g., they felt that God will protect them and that they did not need medication). The parent study established that spirituality/religiousness is associated with long survival, health behaviors, more optimism, less distress and low cortisol in PLWH.17 In a study in HIV-positive women, mainly African American, 92% reported that prayer was an important source for HIV medication decision-making, with 59% considering prayer more important than the physician, which created a sense of conflict for some.43 Physicians may ask about the patient’s spirituality/worldview as an aid in coping. This can send an important message of concern that may enhance the patient–physician relationship.44

Drug resistance

Less than half of the participants for whom resistance testing should have been done reported resistance testing. The African American community, in particular women, was more likely to have a detectable viral load without being appropriately counseled and offered resistance testing. Factors related to getting resistance testing were higher education and patient knowledge about drug resistance. This suggests that lack of patient knowledge can be a barrier to quality care. These results propose that disparities in quality of treatment may depend on ethnicity, gender, education, and treatment knowledge.

Experience of HIV/AIDS symptoms

A significant proportion of participants were not taking ART or not adhering to ART despite having prior experience with HIV/AIDS symptoms. It is also important to note that participants were less likely to report symptoms of HIV/AIDS when they were asked general questions in the interview as opposed to when they were completing the Physical Symptoms Checklist. Therefore, physicians should use specific checklists to assess symptoms rather than general questions.

Preference for and use of CAM

The preference for CAM and distrust of biomedical treatment was one of the reasons for participants not to take ART in this study as well as in other studies.1,4,7,8 Patient preference for CAM and the decision to forgo ART prevent patients from letting the medical profession take over control and is a potential impediment to subsequent adherence or willingness to tolerate adverse effects of ART.1 Patients declining ART have less faith in ART than their physicians.1,7

Some of the participants (17%) preferred CAM to ART, but more than half reported the use of CAM (e.g., cognitive and behavioral therapy, social support, yoga, meditation, guided imagery, relaxation, massage, etc.), which is similar to results of other studies in the United States45 and Europe.46 In our study, we did not investigate whether the physician was involved in the decision to use CAM. A U.S. study found that most patients (59% of 324) told their physicians about their use of CAM, but despite the potential for serious interactions of these therapies with ART, this information was registered in the patient’s chart in only 13% of the time.45

Socioeconomic aspects in decision-making about ART

The diverse sample included not only gay white middle-class men, but also a substantial proportion of heterosexual African American women and men with a lower socioeconomic status, representing today’s face of HIV in the United States. Interestingly, only one demographic characteristic was associated with a greater willingness to take ART: having a partner. This is consistent with another study that found that PLWH revised their decision to forgo ART because they wanted to live for their partners.15 All participants were offered ART. Only one participant did not take ART because he could not afford to pay for his medications. These encouraging results are a product of the drug access programs covering the costs of ART for PLWH who have a low-income level. Nevertheless, PLWH who do not qualify for drug access programs may consider financial constraints in their decision making about ART.

Limitations of this study

Because this was a cross-sectional study, the associations may not be causal. This study did not examine how strongly the necessity of taking ART was stressed by the physician. Because of the initial entry criteria of the parent study, participants with prior AIDS-defining symptoms, active substance dependence, and active psychosis were underrepresented. Because the interviews were conducted after the participants had made their decision about ART, it is important to consider the possible effects of cognitive dissonance and self-perception.47 In addition, adherence was exclusively measured by self-reports that lead to overestimation of adherence.48 Finally, we did not collect information on the HIV serostatus of the partner. Future research might address if the HIV serostatus of the partner has an influence on the decision to take or not to take ART.

CONCLUSIONS

Table 3 summarizes the 10 suggestions that evolve out of the 10 criteria that PLWH use in decision making about ART and relevant studies from the literature. In their decision about ART, PLWH consider not only symptoms, adverse effects and surrogate markers, but also issues of perceived quality of life, beliefs about health, ART, CAM, and spirituality. Mind–body beliefs or the individual spiritual beliefs can encourage as well as discourage PLWH to take ART, whereas a preference for alternative medicine, avoidance of adverse effects of ART and a short-term benefit in quality of life are the main motives for PLWH to forgo ART.

Table 3.

Ten criteria of PLWH in decision-making about ART and suggestions for clinical practice

| Surrogate markers |

| Explain the importance of surrogate markers in a manner that it is not too abstract and is connected with a patient’s feelings. Recognize that PLWH may prefer to start ART later than guidelines recommend and ensure that they understand the consequences of this decision. |

| Better quality of life |

| Regular assessments of quality of life may be as important as measuring surrogate markers. |

| Beliefs/knowledge about resistance |

| Make sure that all patients understand the concept of resistance and how nonadherence is related to the development of resistance. |

| Mind–body belief |

| As many patients believe in a mind–body connection it is important to explore how this may affect their decision-making. |

| Adverse effects |

| It is important to acknowledge not only whether the patient experiences adverse effects, but also how he/she perceives them. Some people are willing to tolerate adverse effects, because they believe the medication is very necessary or the body will adjust to it. Others are inclined to stop or not to start treatment to avoid adverse effects. |

| Easy to take regimen |

| Simplify ART as much as possible for people to whom this is important, but remember that this is not the most important issue for many PLWH. |

| Spirituality/worldview |

| Take a patient’s spirituality and worldview into account as it may have an impact on decision-making. Operate within the patient’s spiritual belief system rather than your own. Acknowledge and support the patient’s spiritual beliefs and worldviews that aid in coping in living with HIV. |

| Drug resistance |

| Offer drug resistance testing to all patients who need it. |

| Experience of HIV/AIDS symptom |

| Assess regularly the symptoms related to HIV with checklists. |

| Preference for CAM |

| Acknowledge patients preference for CAM and ask (and record?) each patients use of CAM, being aware of potential drug interactions. |

PLWH, persons living with HIV/AIDS; ART, antiretroviral treatment; CAM, complementary and alternative medicine.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

The authors acknowledge all the people living with HIV/AIDS for their faithful participation in the long-term survivor study, and Annie George for performing interviews. The authors thank the pharmaceutical companies Glaxo-Smith-Kline and Gilead for funding this substudy and the National Institute of Health (R01MH53791 and R01MH066697, principal investigator: Gail Ironson) for financially supporting the parent study on the Psychology of Health and Long Survival with HIV/AIDS.

REFERENCES

- 1.Cooper V, Buick D, Horne R, et al. Perceptions of HAART among gay men who declined a treatment offer: Preliminary results from an interview-based study. AIDS Care. 2002;14:319–328. doi: 10.1080/09540120220123694. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ferguson TF, Stewart KE, Funkhouser E, Tolson J, Westfall AO, Saag MS. Patient-perceived barriers to antiretroviral adherence: Associations with race. AIDS Care. 2002;14:607–617. doi: 10.1080/0954012021000005434. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Gellaitry G, Cooper V, Davis C, Fisher M, Date HL, Horne R. Patients’ perception of information about HAART: Impact on treatment decisions. AIDS Care. 2005;17:367–376. doi: 10.1080/09540120512331314367. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Gold RS, Hinchy J, Batrouney CG. The reasoning behind decisions not to take up antiretroviral therapy in australians infected with HIV. Int J STD AIDS. 2000;11:361–370. doi: 10.1258/0956462001916065. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Hirsch MS, Sterritt C. Conference report. early vs late initiation of antiretroviral therapy for HIV infection: A scientific roundtable meeting; Medscape HIV/AIDS; September 24–26; Atlanta, GA. 2003. [Last accessed July 7, 2005]. p. 9. www.medscape.com/viewarticle/463372. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Reynolds NR, Testa MA, Marc LG, et al. Factors influencing medication adherence beliefs and self-efficacy in persons naive to antiretroviral therapy: A multicenter, cross-sectional study. AIDS Behav. 2004;8:141–150. doi: 10.1023/B:AIBE.0000030245.52406.bb. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kremer H, Bader A, O’Cleirigh C, Bierhoff HW, Brockmeyer NH. The decision to forgo antiretroviral therapy in people living with HIV compliance as paternalism or partnership? Eur J Med Res. 2004;9:61–70. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Laws MB, Wilson IB, Bowser DM, Kerr SE. Taking antiretroviral therapy for HIV infection: Learning from patients’ stories. J Gen Intern Med. 2000;15:848–858. doi: 10.1046/j.1525-1497.2000.90732.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.McGuire S. Making the decision to start therapy on the level. BETA. 2004;16:20–26. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Russell CK, Bunting SM, Graney M, Hartig MT, Kisner P, Brown B. Factors that influence the medication decision making of persons with HIV/AIDS: A taxonomic exploration. J Assoc Nurses AIDS Care. 2003;14:46–60. doi: 10.1177/1055329003255114. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Phillips AN, Lepri AC, Lampe F, Johnson M, Sabin CA. When should antiretroviral therapy be started for HIV infection? interpreting the evidence from observational studies. AIDS. 2003;17:1863–1869. doi: 10.1097/00002030-200309050-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Wood E, Hogg RS, Harrigan PR, Montaner JS. When to initiate antiretroviral therapy in HIV-1-infected adults: A review for clinicians and patients. Lancet Infect Dis. 2005;5:407–414. doi: 10.1016/S1473-3099(05)70162-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Bogart LM, Kelly JA, Catz SL, Sosman JM. Impact of medical and nonmedical factors on physician decision making for HIV/AIDS antiretroviral treatment. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2000;23:396–404. doi: 10.1097/00126334-200004150-00006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Department of Health. The Expert Patient: A New Approach to Chronic Disease. London: Department of Health; Management for the 21st Century. 2001

- 15.Kremer H. [Compliance with HIV-therapy under the aspect of patient’s autonomy] [Master’s thesis] Bochum, Germany: Department of Psychology, Ruhr University Bochum; 2001. Compliance in der HIV-Therapie unter dem Aspekt der Selbstbestimmung. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Ironson G, Balbin E, Solomon G, et al. Relative preservation of natural killer cell cytotoxicity and number in healthy AIDS patients with low CD4 cell counts. AIDS. 2001;15:2065–2073. doi: 10.1097/00002030-200111090-00001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Ironson G, Solomon GF, Balbin EG, et al. The ironson-woods Spirituality/Religiousness index is associated with long survival, health behaviors, less distress, and low cortisol in people with HIV/AIDS. Ann Behav Med. 2002;24:34–48. doi: 10.1207/S15324796ABM2401_05. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Ironson G, Balbin E, Stuetzle R, et al. Dispositional optimism and the mechanisms by which it predicts slower disease progression in HIV: Proactive behavior, avoidant coping, and depression. Int J Behav Med. 2005;12:86–97. doi: 10.1207/s15327558ijbm1202_6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Ironson G, O’Cleirigh C, Fletcher MA, et al. Psychosocial factors predict CD4 and viral load change in men and women with HIV in the era of HAART. Psychosom Med. 2005;67:1013–1026. doi: 10.1097/01.psy.0000188569.58998.c8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Department of Health and Human Services (DHHS) (US) [Last accessed July 7, 2005];Guidelines for the use of antiretroviral agents in HIV-infected adults and adolescents. www.aidsinfo.nih.gov/guidelines. [PubMed]

- 21.AIDS Clinical Trials Group (ACTG) [Last accessed July 7, 2005];ACTG adherence follow-up questionnaire. 2001 www.caps.ucsf.edu/projects/2098.4188.pdf.

- 22.Mayring P. [Qualitative Content Analysis. Basics and Techniques] 7th ed. Weinheim, Germany: Deutscher Studien Verlag; 2000. Qualitative Inhaltsanalyse. Grundlagen Und Techniken. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Mayring P. Qualitative content analysis. [Last accessed July 7, 2005];Forum: Qualitative Social Research. www.qualitative-research.net/fqs-texte/2-00/2-00mayring-e.htm.

- 24.Hays WL. 3rd ed. New York, NY: Dyden Press; 1981. Statistics. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Bakeman R, Gottmann JM. An Introduction to Sequential Analysis. Cambridge, UK: University Press; 1986. Observing Interaction. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Hooper H, Burwitz L, Hodkinson P. Exploring the benefits of a broader approach to qualitative research in sport psychology: A tale of two, or three, james. [Last accessed July 7, 2005];Forum: Qualitative Social Research. 2003 :4. www.qualitative-research.net/fqs-texte/1-03/1-03hooperetal-e.htm.

- 27.Wendler MC. Triangulation using a meta-matrix. J Adv Nurs. 2001;35:521–525. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2648.2001.01869.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Gallant JE. Editorial comment: Strategies for success—A return to “hit early”? AIDS Read. 2004;14:662–663. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Mauskopf J, Kitahata M, Kauf T, Richter A, Tolson J. HIV antiretroviral treatment: Early versus later. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2005;39:562–569. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Zinkernagel C, Ledergerber B, Battegay M, et al. Quality of life in asymptomatic patients with early HIV infection initiating antiretroviral therapy. Swiss HIV cohort study. AIDS. 1999;13:1587–1589. doi: 10.1097/00002030-199908200-00024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Stone VE, Clarke J, Lovell J, et al. HIV/AIDS patients’ perspectives on adhering to regimens containing protease inhibitors. J Gen Intern Med. 1998;13:586–593. doi: 10.1046/j.1525-1497.1998.00180.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Golin CE, Liu H, Hays RD, et al. A prospective study of predictors of adherence to combination antiretroviral medication. J Gen Intern Med. 2002;17:756–765. doi: 10.1046/j.1525-1497.2002.11214.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Paterson DL, Swindells S, Mohr J, et al. Adherence to protease inhibitor therapy and outcomes in patients with HIV infection. Ann Intern Med. 2000;133:21–30. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-133-1-200007040-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Wenger N, Gifford A, Liu H, et al. Patient characteristics and attitudes associated with antiretroviral (AR) adherence [Abstract 98]; 6th Conference on Retroviruses and Opportunistic Infections; Chicago, IL. 1999. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Golin CE, Smith SR, Reif S. Adherence counseling practices of generalist and specialist physicians caring for people living with HIV/AIDS in north carolina. J Gen Intern Med. 2004;19:16–27. doi: 10.1111/j.1525-1497.2004.21151.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Wagner GJ, Ryan GW. Relationship between routinization of daily behaviors and medication adherence in HIV-positive drug users. AIDS Patient Care STDs. 2004;18:385–393. doi: 10.1089/1087291041518238. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Cassileth B. The Alternative Medicine Handbook: The Complete Reference Guide to Alternative and Complementary Therapies. 1st ed. New York: W.W. Norton & Company; 1998. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Antoni MH, Cruess DG, Klimas N, et al. Stress management and immune system reconstitution in symptomatic HIV-infected gay men over time: Effects on transitional naive T cells (CD4(+)CD45RA(+) CD29(+)) Am J Psychiatry. 2002;159:143–145. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.159.1.143. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Chesney MA, Chambers DB, Taylor JM, Johnson LM, Folkman S. Coping effectiveness training for men living with HIV: Results from a randomized clinical trial testing a group-based intervention. Psychosom Med. 2003;65:1038–1046. doi: 10.1097/01.psy.0000097344.78697.ed. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Ironson G, Antoni MH, Schneiderman N, et al. Stress management and psychosocial predictors of disease course in HIV-1 infection. In: Goodkin K, Visser AP, editors. Psychoneuroimmunology, Stress, Mental Disorders and Health. Washington D.C.: American Psychiatric Press; 2000. pp. 317–356. [Google Scholar]

- 41.Gallant JE, Block DS. Adherence to antiretroviral regimens in HIV-infected patients: Results of a survey among physicians and patients. J Int Assoc Physicians AIDS Care. 1998;4:32–35. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Stone VE, Jordan J, Tolson J, Miller R, Pilon T. Perspectives on adherence and simplicity for HIV-infected patients on antiretroviral therapy: Self-report of the relative importance of multiple attributes of highly active antiretroviral therapy (HAART) regimens in predicting adherence. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2004;36:808–816. doi: 10.1097/00126334-200407010-00007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Crane JR, Perlman S, Meredith KL, et al. Women with HIV: Conflicts and synergy of prayer within the realm of medical care. AIDS Educ Prev. 2000;12:532–543. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Koenig HG. MSJAMA: Religion, spirituality, and medicine: Application to clinical practice. JAMA. 2000;284:1708. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Southwell H, Valdez H, Lederman M, Gripshover B. Use of alternative therapies among HIV-infected patients at an urban tertiary care center. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2002;31:119–120. doi: 10.1097/00126334-200209010-00017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Colebunders R, Dreezen C, Florence E, Pelgrom Y, Schrooten W Eurosupport Study Group. The use of complementary and alternative medicine by persons with HIV infection in Europe. Int J STD AIDS. 2003;14:672–674. doi: 10.1258/095646203322387929. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Albarracin D, Wyer RS., Jr The cognitive impact of past behavior: Influences on beliefs, attitudes, and future behavioral decisions. J Pers Soc Psychol. 2000;79:5–22. doi: 10.1037//0022-3514.79.1.5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.DiMatteo MR. Variations in patients’ adherence to medical recommendations: A quantitative review of 50 years of research. Med Care. 2004;42:200–209. doi: 10.1097/01.mlr.0000114908.90348.f9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]