Abstract

High definition self-assemblies, those that possess order at the molecular level, are most commonly made from subunits possessing metals and metal coordination sites, or groups capable of partaking in hydrogen bonding. In other words, enthalpy is the driving force behind the free energy of assembly. The hydrophobic effect engenders the possibility of (nominally) relying not on enthalpy but entropy to drive assembly. Towards this idea, we describe how template molecules can trigger the dimerization of a cavitand in aqueous solution, and in doing so are encapsulated within the resulting capsule. Although not held together by (enthalpically) strong and directional non-covalent forces, these capsules possess considerable thermodynamic and kinetic stability. As a result, they display unusual and even unique properties. We discuss some of these, including the use of the capsule as a nano-scale reaction chamber and how they can bring about the separation of hydrocarbon gases.

Introduction

In conceiving high definition supramolecular assemblies showing well-defined structure at the molecular level, chemists have traditionally relied upon enthalpy as the means to engendering a favorable free energy of assembly (Equation 1). This is intuitive from the perspective of a written chemical reaction involving only subunits; the bringing together of many chemical entities is not favored by entropy. Consequently, to ensure exothermicity such assemblies are typically driven by functionality - or assembly motifs - capable of partaking in relatively strong and highly directional non-covalent forces; hydrogen bonding1-7 and metal coordination8-20 being the most common. Indeed, the dominance of enthalpy in high-definition self-assemblies is so great that invoking words such as ‘powerful’ and ‘directional’ can trigger the misassumption that these terms are necessarily enthalpically-based. This is of course not the case.

| (1) |

Nature is very capable of taking the ‘opposite’ approach. Although bringing together two or more species is, from a written chemical equation standpoint, entropically penalized, solution based assemblies do not take place in a vacuum. It is quite possible for the free energy of assembly to be primarily driven by entropy (Equation 1) if the assembly liberates solvent molecules in the process. The key to such a strategy is of course water and the hydrophobic effect.21-25

Although an abundant molecule (that is made up from the first and third most abundant elements in the universe), many of the properties of water are still poorly understood. If this were not the case, two of the best examples of pathological science - polywater26 and memory water27 - probably wouldn't exist! The complexity of bulk water leads to many (real) emergent phenomenon, the most familiar of which is the hydrophobic effect, the tendency for oil and water to segregate.21 This phenomenon is manifest in countless ways in Nature,28 including the assembly of phospholipids to form vesicles, and the folding and assembly of proteins to yield respectively tertiary and quaternary structure. It is also in part responsible for the assembly and structure of duplex DNA, and of course the binding of effectors or substrates to proteins, enzymes, and ribozymes. It is omnipresent.

There are both enthalpic and entropic facets to the hydrophobic effect. Regarding the former, when a hydrophobic solute is expelled from the aqueous phase strong water-water interactions (the cohesive force) are increased at the expense of weaker water-hydrocarbon interactions (a minor enthalpic role can also be played by the polarizability of hydrocarbons verses the lack of polarizability of water). Although these factors frequently play a role, often the change in enthalpy as a solute is moved out of the aqueous solution is very small or even positive. In such cases, and indeed in the majority of examples at ambient temperatures, the hydrophobic effect is primarily driven by entropy.29,30 Passing over the examples where this is not the case, the hydrophobic effect is commonly viewed in terms of water being ordered around a hydrophobic solute, and if this solute can bind into a hydrophobic environment, then these waters are liberated to the bulk. As has been pointed out,21 this notion is correct to a first approximation, but one should take care not to invoke the idea of clathrate structure. Clearly, such an extreme view is incorrect; the dynamics of water structure is on the femtosecond timescale, and so the suggestion of clathrates around hydrophobic solutes is one step towards poly- and memory water. Nevertheless, a corollary of ‘ordered’ water is that self-assemblies in aqueous solution need not rely on enthalpy; entropy can be harnessed if we have a firm understanding of the hydrophobic effect. Herein lies the problem, because as just alluded to the hydrophobic effect is not fully understood. Our lack of understanding arises in part because what one observes or measures depends on the state of water molecules around a solute, which in turn depends on its hydrophobicity, size and shape. Depending on these and other factors, a solute surface may be wetted (the water density immediately surrounding the hydrophobic solute is greater than the bulk) or dewetted (the water density immediately surrounding the solute is less than the bulk). Consequently, researchers investigating the hydrophobic effect may turn up what prima facie appears to be conflicting data, because subtle difference between the systems under study are not fully appreciated. Nevertheless, in mimicry of Nature, the hydrophobic effect has been used to great affect to from host-guest complexes,31-37 fold foldamers,38-41 and assemble micelles, liposomes and their ilk;42, 43 entities that are partially ordered in so much as they show structure on scales beyond the molecular, but little of no structure at the molecular level. However, the synthesis of analogous high definition supramolecular assembles, those that are well defined at the molecular level, requires an increase in our current understanding of the hydrophobic effect. To take but one example, it is likely that Nature uses many subtle approaches to marshal the hydrophobic effect and bring about protein quaternary structure. Can these be understood and exploited? We know what constitutes a powerful assembly motif in enthalpically driven assemblies, what constitutes a powerful motif in those driven by entropy? What will be the properties of such assemblies? This highlight reviews some of our results as we try to answer these and related questions.

A Water-Soluble, Self-Assembling, Deep-Cavity Cavitand

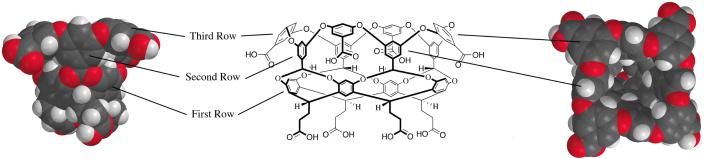

The deep-cavity cavitands44 developed in our group are resorcinarene-based molecular hosts whose cavities are built up from twelve aromatic rings.45-50 We have reported on a number of these hosts, but focus here on the cavitand shown in Figure 1. Four of the aromatic rings, those that constitute the starting resorcinarene, are termed the first row. Built on this is a second row of rings that deepens the hydrophobic cavity of the resorcinarene considerably, and a third row that both rigidifies the binding pocket whilst proving the host with a wide hydrophobic rim that is essential to its predisposition to assemble in aqueous solution. Water-solubility is by virtue of the external coat of carboxylic acids; the outer edge of the cavity rim is decorated with four, whilst the four ‘feet’ of the cavitand are also each terminated with a carboxylic acid.

Figure 1.

‘Side” view of space-filling model, chemical structure, and “Plan” view of space-filling model of deep-cavity cavitand 1. Highlighted are the three rows of aromatic rings that make up the binding pocket.

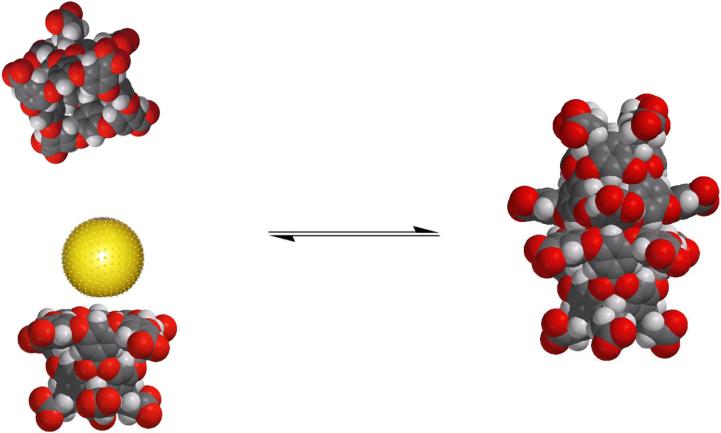

The host has limited solubility (tens of micromolar) in neutral solution, presumably because the carboxylic acids have typical pKa values of between 5-6 and so not all are deprotonated at pH 7. However, in basic solution - most of our studies have been in sodium tetraborate solution (pH = 8.9) - the host is quite soluble. Under these conditions, it is monomeric at millimolar concentrations, but exists as a disordered aggregate at concentrations of ten millimolar and above. In the latter case, the resulting broad signals in the NMR spectrum are not informative, but it is presumably the hydrophobic rim that promotes these kinetically unstable assemblies. Regardless of the host concentration, the addition of a suitable guest molecule triggers dimerization and entrapment of the guest within the resulting capsule (Figure 2). The range of guests that trigger dimerization is large (vide infra); the only prerequisites are that the guest is small enough to fit within the nano-scale cavity, and is non-polar enough that it is energetically feasible for the guest to partition into the host.

Figure 2.

The dimerization of cavitand 1 around a generic guest (yellow sphere). The capsule is shown in the (orientational) isomer in which all second row rings are edge to face stacked with a third row ring in the other hemisphere (D4d symmetry).

These dimer capsules are not held together by enthalpically strong or directional non-covalent forces. Thus, the interface of the dimer involves only enthalpically weak π⋯π interactions.51 Models suggest that maximal overlap in the interface is achieved in the D4d symmetric capsule (Figure 2) in which the two hemispheres are out of register by 45°, and the D4h form where the two hemispheres are fully in register. In the former, the interface is composed of edge to face stacking between the second row of one hemisphere and the third row of the other, while the latter is composed of slipped stacking between the third rows of each hemisphere. Presumably, ‘free’ rotation of one hemisphere relative to the other is possible without breaking the interface. In part, the complexes are also held together by host-guest interactions. Again however, most of the guest we have examined to date can only partake in enthalpically weak interactions with the host. Nevertheless, both the thermodynamic and kinetic stabilities of these complexes are considerable. Apparent association constants (Kapp, for empty to filled capsule) can be greater than 1 × 108 M-1, whilst even the encapsulation of small guests that leave considerable empty space form complexes that are stable on the NMR timescale (greater than millisecond lifetimes). Furthermore, the stability of these complexes can be increased by additives known to enhance the hydrophobic effect, e.g., NaCl, and decreased by common denaturants such as ethanol. These results emphasize that enthalpically strong non-covalent interactions are not a prerequisite for self-assembly and that careful orchestration of the hydrophobic effect can be a powerful approach to high definition self-assembly. We build on this point using the specific examples below.

Steroid Encapsulation

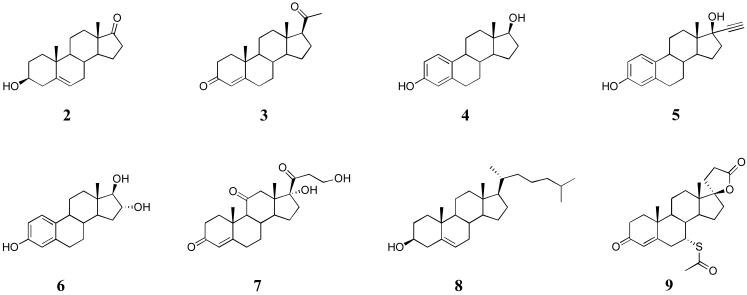

Although we anticipated that cavitand 1 would be able to self-assemble around guest molecules, we were initially concerned that the encapsulation complexes would not possess very high thermodynamic or kinetic stability. Consequently, our first studies “stacked the deck” by examining a range of steroids (Figure 3, 2-9).52 These rigid molecules were expected to template capsule assembly and enhance its stability by inhibiting lateral slippage of the two cavitands.

Figure 3.

Guest steroids encapsulated within the dimer of 1.

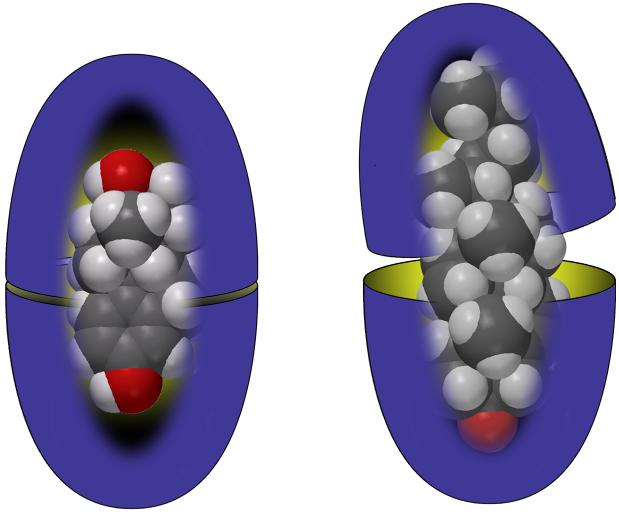

In the presence of 1, all of these guests were shown to dissolve in aqueous solution. Further, NMR reveled that a 2:1 ratio of cavitand 1 and steroid gave only encapsulation complexes (e.g., Figure 4). In each, the signals for the guest all appeared upfield from where they occur in free solution because within the capsule the guests are shielded by the aromatic walls of the host. For the guests dehydroisoandrosterone 2, progesterone 3, estradiol 4, 17αethynylestradiol 5, and estriol 6, the rate of guest exchange was slow on the NMR timescale and, given an excess of guest, signals for the free and the encapsulated state were visible. To estimate the association constants seen in these complexes we examined the complex formed by estradiol 4 by NMR dilution experiments, and then performed competition experiments between estradiol and the other steroids. Estradiol 4 formed a complex with an apparent association constant Kapp > 1 × 108 M-1, however guests with more voluminous A-rings bound more strongly. Thus, for these five guests the strength of binding to the dimer of 1 was: dehydroisoandrosterone 2 > progesterone 3 > estradiol 4 > 17α-ethynylestradiol 5 > estriol 6. In contrast, with the larger and more water-soluble cortisone 7, and the larger cholesterol 8 and spironolactone 9, the corresponding complexes were of much lower kinetic and thermodynamic stability. For example, although solubilized by 12, cholesterol 8 did not form a kinetically stable capsule. NMR signals in this complex were broad. Space-filling models explained these observations; with its C-17 hydrocarbon tail, cholesterol is too long to fit within the cavity (Figure 4). As a result, the two hydrophobic rims cannot clamp down on one another and so must remain water solvated. We conclude from this that dewetting of the interface at the equator of the capsule is essential to its stability.

Figure 4.

Representations of the capsule formed by 1 containing estradiol 4 (left) and cholesterol 8 (right).

Hydrocarbon Encapsulation

If steroids can promote the dimerization of the host, can flexible molecules do likewise? That was our next question, and to answer it we turned to the n-alkanes from pentane through to octadecane.53 Analogous to cholesterol, the latter proved to be too voluminous for the capsule. The guest was solubilized in aqueous solutions of the host, but the NMR signals of the complex were broad, indicating relatively low kinetic stability. The picture changed dramatically with heptadecane, which was shown to form a more kinetically stable 2:1 host-guest complex. Indeed, all guests from nonane through hexadecane formed similar ternary complexes. In these entities, the methyl 1H NMR signal of the guest was the most shifted, indicating that each terminal group was anchored deeply into the polar region of a hemisphere. This is a much more efficient packing conformation than U-shaped binding in which two methyls would compete for a polar region, and a turn in the chain would occupy the opposing pole. However, for guests longer than decane, the guest cannot adopt a fully extended conformation. Consequently, the guest must fold up in some manner to be accommodated. For example, NOESY NMR revealed long range interactions down the chain length of dodecane, indicating that it adopts a mainly helical conformation within the capsule. It is interesting to note that such helices have been seen in related, hydrogen bonded capsules.54 If the packing of these types of guests within other hosts frequently involves helices, it would parallel the notion that α-helices are the most prevalent of protein secondary structures precisely because they represent such an efficient mode of packing.

Continuing our study of alkane binding to 12, we observed that the guests pentane through heptane formed not 2:1, but 2:2 (quaternary) complexes. Furthermore, octane turned out to be the confused guest of the series in so much as it formed both ternary and quaternary complexes. During titration experiments, no free guest was observed until beyond the equivalence point, demonstrating the complexes have considerable thermodynamic stability and that exchange between the free and the bound state was slow on the NMR timescale. Even for pentane, the resulting quaternary complexes had good kinetic stability. Overall, this family of guests demonstrated packing coefficients (PC, ρguest/ρcav × 100) of between 48% and 73%, with the best guest dodecane having an occupancy factor of 53%. This latter value is close to the often-quoted ideal occupancy of 55%. However, it ought to be remembered that this value approximates to the height of a bell-curve for a Ka verses PC graph and makes no comment regarding its width or shape; it is the width/shape of the bell-curve that define the range of guests that bind. Although we do not know the precise shape of this bell-curve, the 48-73% PC range for alkane guests suggests a powerful host capable of binding many sizes of guests, and that the hydrophobic effect can be a strong ally to bring about self-assembly and entrapment.

Reactions within the Capsule

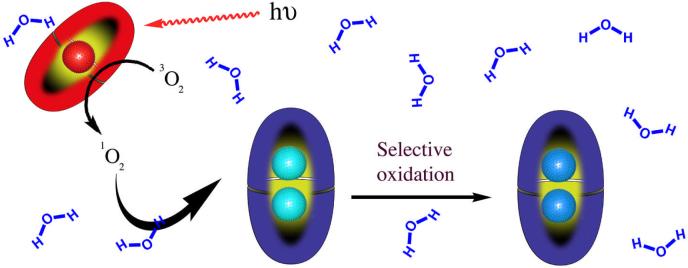

If many types of molecules trigger dimerization of 1 and in the process are encapsulated, then in theory 12 could be used as a nano-scale reaction vessel.55 Taking this thought one-step further, the high kinetic stability of these capsular complexes gives ample opportunity for the reaction performed inside to be templated by the host. With these ideas in mind, we have collaborated with the Ramamurthy group to study photochemical processes within these nano-scale reaction chambers. The nanosecond timeframe of these processes means that even complexes at the low end of the range of possible kinetic stabilities remain integral during reaction. Consequently, the capsule can impart considerable (and varied) chemical instruction. For instance, the β-cleavage of naphthyl esters56 or the singlet oxidation of olefins57 give many different products in solution, but within the capsule these reactions are brought into sharp focus. The latter example is particularly interesting as it demonstrates that capsules containing sensitizers (red in Figure 5) can chemically communicate, using singlet oxygen, through the aqueous solution with capsules containing substrates (light blue). Once within the substrate containing capsule, specific orientation of the guest ensures only one of three oxidation pathways can take place (light to dark blue).57

Figure 5.

The selective oxidation of substrates (light to dark blue guests) within a capsule. Singlet oxygen is generated in a sensitizer containing capsule (red), which must then make its way to substrate containing capsule.

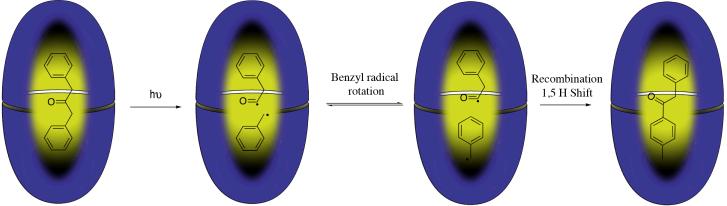

The capsule is also capable of templating the formation of products not observed in solution. Thus, the major compound produced from the photolytic cleavage of the α-C-C bond of dibenzyl ketone is not the normally observed decarbonylated product 1,2-diphenyl ethane, but (p-methyl)-phenylbenzyl ketone (Figure 6).58 Cleavage of one of the α-C-C bonds initiates this conversion, but the two radicals produced do not optimally fill the cavity and there is a subsequent 180° rotation of the benzyl radical that lowers the overall packing energy. Recombination and a 1,5 hydrogen atom shift leads to the observed rearrangement product.

Figure 6.

The capsule templated rearrangement of dibenzyl ketone to give (p-methyl)-phenylbenzyl ketone

The flipside of increasing the selectivity of reactions or engendering novel reaction, i.e., bringing normally facile reactions to a halt, can also be induced by encapsulation. By way of example, irradiation of the capsule containing two molecules of anthracene leads to strong excimer emission but no reaction between them. The reason this state of affairs is observed is that the cavity is highly packed (PC = 85%, the highest we have observed) and the essentially immobile guests are held out of register relative to each other and cannot undergo reaction.59

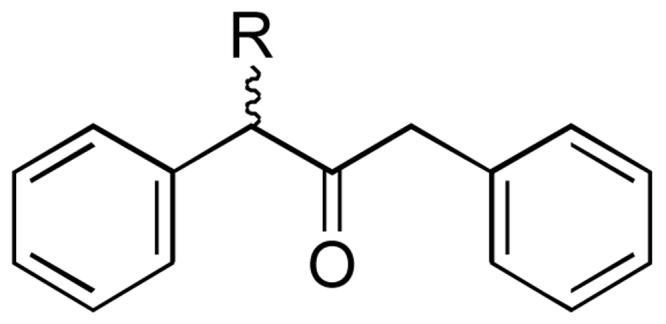

Most recently, building on our study of the photochemistry of encapsulated dibenzyl ketones, we turned our attention to a homologous series of flexible guests (10, Figure 7) to examine how guest packing within the capsule influences the multiple chemical channels in their triplet excited-state surface.60

Figure 7.

α-Alkylated dibenzyl ketone guests 10: R = Me, Et, n-Pr, n-Bu, n-Pentyl, n-Hexyl, n-Heptyl and n-Octyl. Guests highlighted in the text are the methyl (10a), n-pentyl (10b) and n-octyl (10c)

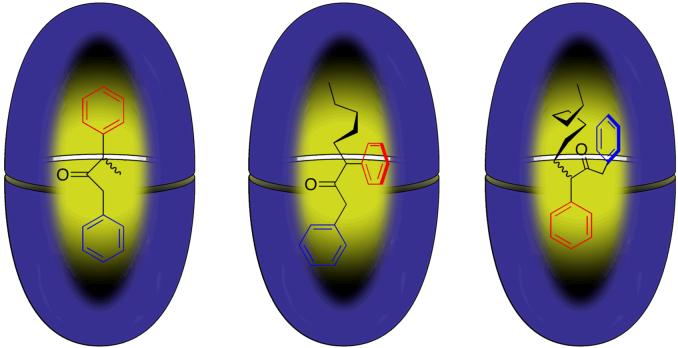

NMR experiments reveal that in combination with cavitand 1, each guest forms 2:1 capsular complexes. Furthermore, NMR also reveals that within this series of eight complexes there are three distinct families each with an identifiable mode of guest packing (Figure 8). With a small R group such as methyl, the dibenzyl ketone guest (10a, R = Me) packs the cavity by inserting its aromatic rings into the hemispheres of the capsule (Figure 8a). However, a longer R group is better able to pack the narrowest polar region of a hemisphere and consequently the alkyl chain of the n-pentyl derivative (10b, R = n-pentyl) displaces its nearest neighbor phenyl ring (red) pushing it into an equatorial region of the capsule (Figure 8b). A third method of packing is seen with still longer alkyl chains. Thus, the n-octyl case (10c, R = n-octyl) differs from the n-pentyl guest by the two phenyl rings trading positions within the capsule (Figure 8c). It is not yet clear why this change occurs, but perhaps the alkyl group is so long the guest tries to decrease its packed length by a -CH2C(O)- unit at the cost of an increase in width by the same amount.

Figure 8.

The three distinct packing motifs observed for guests 10a-c.

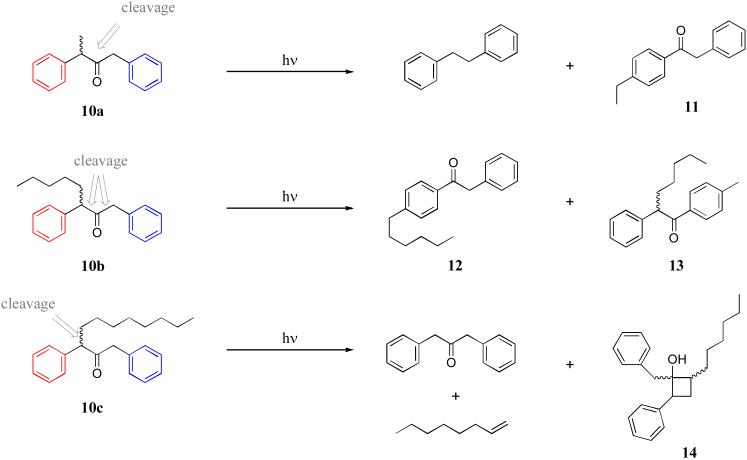

The result of these different packing motifs is that photolysis is highly dependent on the precise length of the alkyl chain, and in all cases, quite different from solution chemistry that produces a preponderance of Norrish type I products, as well as more minor amounts of type II products. Thus, within the capsule the methyl derivative 10a (R = Me) undergoes a considerable amount of decarbonylation to yield 1,2-diphenylethane, but also yields significant amounts of (p-ethyl)-phenylbenzyl ketone 11 arising from homolytic cleavage of the alkyl substituted α-C-C bond (Scheme 1). This is the expected rearrangement product arising from formation of the more stable secondary benzyl radical, radical rotation to more optimally fill the cavity, and then recombination.

Scheme 1.

Representative products arising from the photolysis of the capsular complexes of 10a, 10b and 10c.

With a different packing conformation, the n-pentyl guest 10b (R = n-pentyl) undergoes relatively little decarbonylation. Instead, the major products are rearrangement products 12 and 13 (Scheme 1), the former through a cleavage mechanism similar to the formation of 11, the latter arising through cleavage of the alternate (unsubstituted) α-C-C bond and rotation of the benzyl radical before recombination. We believe that cleavage of the unsubstituted α-C-C bond can compete with cleavage of the substituted α-C-C bond because the latter leads to two radicals that pack the cavity efficiently without having to reorientate. The pentyl group is an effective anchor of the secondary benzyl radical and so it and the acyl radical can recombine to regenerate starting material. This biases cleavage of the unsubstituted α-C-C bond, the resulting benzyl radical of which can undergo rotation within the cavity before recombination to form 13.

Photolysis of guests that pack with the motif shown in Figure 8c, for example 10c (R = n-octyl), give mostly Norrish type II products. Thus, 90% of encapsulated 10c forms type II products (Scheme 1); there is an 83% yield of dibenzyl ketone (and 1-octene) and a 7% yield of the cyclobutane 14. Interestingly, the preponderance of dealkylated product over cyclobutane formation is opposite to that seen in solution. These reactions are initiated by abstraction of a γ-hydrogen in the alkyl chain by the carbonyl oxygen. Consequently, we rationalize the high yields of type II products by assuming the carbonyl group is packed closely to the γ-hydrogens (Figure 8c).

These results demonstrate that suitable hosts can harness the hydrophobic effect to influence the outcome of photochemical processes. The capsule 12 forms kinetically stable complexes that allow the redirection of chemical reactions away from that normally seen in solution. At the same time, the capsules are dynamic enough to allow chemical communication between capsules, albeit in a one-way manner. From a slightly different perspective, these results also demonstrate that like micelles,61 host 1 can be used to perform reactions that are normally difficult to carry out in aqueous solution.

Electrochemistry within and on the Outer Surface of the Capsule

In collaboration with the Kaifer group, we have examined how the capsule formed by 1 can modify the electochemistry of redox active guests. In these studies, the necessary presence of a charge carrier (40 mM NaCl) increased the propensity of the cavitand to dimerize and led to some unusual complexes.62

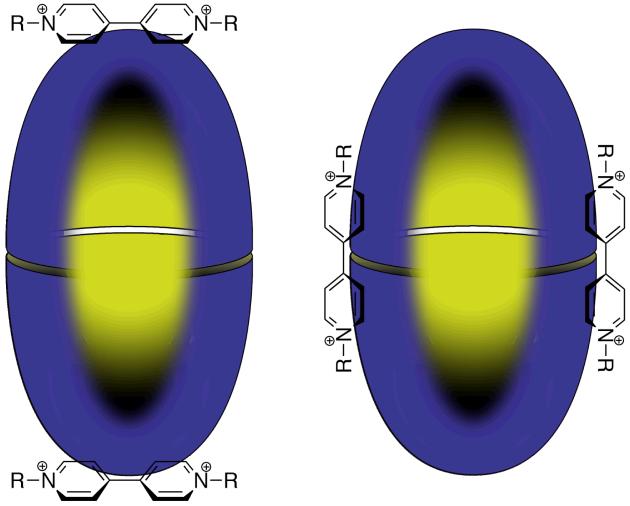

As anticipated, ferrocene readily formed an encapsulation complex. Shielded from the external environment, the cyclic voltammogram recorded for this complex was essentially flat, with very small levels of faradaic currents associated with the oxidation to ferrocenium. In a similar vein, the more sensitive technique square wave voltammetry also showed little or no faradaic response. These results were attributed to slow heterogeneous electron transfer kinetics between the entrapped ferrocene and the electrode surface. The complexation of methyl, ethyl and butyl viologens was also examined. 1D and PGSE NMR experiments indicated that in these cases two viologen guests were bound to the outside of the capsule. Two options seem likely (Figure 9). Association with the polar-regions of the capsule allows each viologen to closely interact with four carboxylates. Alternatively, in a latitudinal, inter-hemisphere position, the guests could associate with arguably more distal carboxylates, but in doing so would help stitch the capsule together. The two reductions of the dicationic viologen were observed with these complexes using cyclic voltammetry, but the current waves were substantially reduced. Furthermore, the rates of heterogeneous electron transfer were also considerably diminished.

Figure 9.

Cartoon of the possible structures of the quinternary complex formed between cavitand 1 and viologen guests.

Finally, if the viologens in the aforementioned complexes are not binding to the inside of the capsule then there must be a vacant binding site available. NMR showed this to be the case, with the formation of the corresponding quinternary complexes composed of two cavitands, two viologens, and one (encapsulated) ferrocene.

Hydrocarbon Gas Separation using the Capsule

Our final example of the ability of supramolecular systems that can harness the hydrophobic effect concerns the separation of hydrocarbon gases. By far the most common approaches to purifying natural gas liquids (NGLs) are: amine absorption (CO2 removal), glycol absorption (H2O removal), cryogenic processes (N2 removal) and subsequent condensation/distillation (hydrocarbon separation). New membrane technologies63 are however becoming increasingly popular, particularly technologies for removing CO2 from the NGLs, and for crude NGL separation at remotes sites. As yet however, there are no practical membrane technologies for separating the hydrocarbon gases themselves.

In studying the binding of n-alkanes to the capsule formed by 1, we had observed that n-pentane formed a kinetically stable quaternary complex. With the above thoughts in mind, we consequently sought to determine if the hydrocarbon gases also formed stable complexes.64 Our initial attempts involved bubbling pure butane through a solution of the host, a process that resulted in the formation of the corresponding quaternary complex. Exchange between the free and the bound state was slow on the NMR timescale with a stoichiometric amount of host and guest, but at the NMR timescale when there was an excess of gas. We are still not sure why this change in kinetics is observed although an intriguing candidate is that in an excess of butane a quinternary complex (three guests within the capsule) can form. Butane did not have to be bubbled through the solution. Its affinity is such that a host solution can extract the gas directly from the gas phase. Similarly, it was shown that propane could also be sequestered directly from the gas phase, and in doing so form a kinetically stable quaternary complex. The limit of capsule templation, at least in the absence of salts known to increase the hydrophobic effect, was ethane. This guest was shown to form a 1:1 complex with the cavitand. Regardless, the quaternary complex of propane is a remarkable entity. If viewed in terms of packing coefficient, the cavity is only 28% full. Thus, kinetically stable capsules formed by 1 have so far displayed PC values from 28% to 85%; a wide range which emphasizes the power of the hydrophobic effect. Alternatively, if the conceit is granted to compare the contents of the capsule to an ideal gas, the pressure of propane in the quaternary complex is in excess of 100 atmospheres. Of course, if the packing coefficient is actually larger because the cavity undergoes partial collapse, the pressure within increases!

Although propane binds strongly, it does so one order of magnitude more weakly than butane. This fact can be exploited to affect a unique means of separating the two gases. Thus, when a mixture of propane and butane was placed in the headspace above a solution of host 1, only butane was extracted from the gas phase into the aqueous phase. As smaller gases are more weakly bound in general, it is theoretically possible to separate any duo of methane, ethane, propane and butane. It is also likely that butane could be separated from a mixture of the four gases, or propane from ethane and methane. It is yet to be determined whether or not the system has the selectivity to separate i-butane from n-butane, or if the presence of salting out species such as sodium chloride can promote templation of the capsule by ethane or even methane. These studies are ongoing.

From the above it is apparent that if marshaled correctly, the hydrophobic effect can be used to drive the formation of high definition assemblies. The supramolecular motif in the dimerization of the cavitand does not involve directional functional groups in the traditional (enthalpic) sense envisioned by how the enthalpy of attraction between a hydrogen bond acceptor and donor changes as a function of the angle between them. Instead, the interface is comprised of aromatic rings involved in π-π interactions. Groups and interactions that are quite capable of bring about high definition assembly if the hydrophobic effect is brought to bear. Further studies along these lines are ongoing, and will be reported in due course.

Acknowledgements

SL and BCG gratefully acknowledge the National Institutes of Health for financial support (GM074031).

Biographies

Dr. Simin Liu was born in 1976 in Wuhan, China. He received his PhD in 2004 from the Wuhan University under the guidance of Prof. Chengtai Wu. From 2005, he worked on cucurbit[n]urils chemistry with Prof. Lyle Isaacs at the University of Maryland as a postdoctoral researcher. Subsequently, he joined Prof. Bruce Gibb's group at the University of New Orleans in 2007. Currently his research focuses on the synthesis of water-soluble cavitand and the assembly of nano-scale capsules.

Professor Bruce Gibb was born in 1965 and hails from Aberdeen, Scotland. He received both his B.Sc. and Ph.D. degrees from Robert Gordon's University. In 1992, he landed on the North American continent, carrying out post-doctoral research with Prof. John Sherman at the University of British Columbia. His time in Vancouver was spent synthesizing novel cavitands and cavitand-protein conjugates. In 1994, he switched to the opposite coast and carried out post-doctoral research on metallo-enzyme mimics with Prof. James Canary at New York University. His independent career began in 1996 at the University of New Orleans. He was promoted to associate professor with tenure in 2002, full professor in 2005, and University Research Professor in 2007. Between trying to dodge hurricanes, his interests lie with various aspects of supramolecular chemistry.

References

- 1.Rebek J., Jr. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2005;44:2068–2078. doi: 10.1002/anie.200462839. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Dalgarno SJ, Tucker SA, Bassil DB, Atwood JL. Science. 2005;309:2037–2039. doi: 10.1126/science.1116579. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.MacGillivray LR, Atwood JL. Nature. 1997;389:469–472. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Sijbesma RP, Meijer EJ. Chem. Commun. 2003:5–16. doi: 10.1039/b205873c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Sessler JL, Jayawickramarajah J. Chem. Comm. 2005:1939–1949. doi: 10.1039/b418526a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Davis JT, Spada GP. Chem. Soc. Rev. 2007;36:296–313. doi: 10.1039/b600282j. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Rebek J., Jr. Acc. Chem. Res. 1999;32:278–286. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Fujita M, Tominaga M, Hori A, Therrien B. Acc. Chem. Res. 2005;38:369–378. doi: 10.1021/ar040153h. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Fujita M, Fujita N, Ogura K, Yamaguchi K. Nature. 1999;400:52–55. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Yoshizawa M, Tamura M, Fujita M. Science. 2006;312:251–254. doi: 10.1126/science.1124985. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Sato S, Iida J, Suzuki K, Kawano M, Ozeki T, Fujita M. Science. 2006;313:1273–1276. doi: 10.1126/science.1129830. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Pluth MD, Bergman RG, Raymond KN. Science. 2007;316:85–88. doi: 10.1126/science.1138748. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Caulder DL, Raymond KN. J. Chem. Soc. Dalton Trans. 1999:1185–1200. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Dong VM, Fiedler D, Carl B, Bergman RG, Raymond KN. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2006;128:14464–14465. doi: 10.1021/ja0657915. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Leung DH, Bergman RG, Raymond KN. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2007;129:2746–2747. doi: 10.1021/ja068688o. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Leung DH, Bergman RG, Raymond KN. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2008;130:2798–2805. doi: 10.1021/ja075975z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Nitschke JR. Acc. Chem. Res. 2007;40:103–112. doi: 10.1021/ar068185n. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Gianneschi NC, Masar MS, III, Mirkin CA. Acc. Chem. Res. 2005;38:825–837. doi: 10.1021/ar980101q. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Ruben M, Rojo J, Romero-Salguero FJ, Uppadine LH, Lehn J-L. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2004;43:3644–3662. doi: 10.1002/anie.200300636. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Seidel SR, Stang PJ. Acc. Chem. Res. 2002;35:972–983. doi: 10.1021/ar010142d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Chandler D. Nature. 2005;437:640–647. doi: 10.1038/nature04162. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Breslow R. J. Phys. Org. Chem. 2006;19:813–822. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Southall NT, Dill KD, Haymet ADJ. J. Phys. Chem. B. 2002;106:521–533. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Pratt LR, Pohorille A. Chem. Rev. 2002;102:2671–2692. doi: 10.1021/cr000692+. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Tanford C. The Hydrophobic Effect. Formation of Micelles & Biological Membranes. 2 ed. John Wiley & Sons; New York: 1980. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Rousseau DL. American Scientist. 1992;80:54–63. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Maddox J, Randi J, Stewart WW. Nature. 1988;334:287–290. doi: 10.1038/334287a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Levy Y, Onuchic JN. Annu. Rev. Biophys. Biomol. Struct. 2006;35:389–415. doi: 10.1146/annurev.biophys.35.040405.102134. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.A positive change in entropy is a good, but not perfect, indicator of the hydrophobic effect. Rather, a much better indicator is the negative heat capacity change observed when a solute is expelled form the aqueous phase.

- 30.Aqueous-based complexations driven by enthalpy and penalized entropically are often referred to as being driven by non-classical hydrophobic effects. See for the example, reference 31.

- 31.Diederich F. Molecular recognition studies with cyclophane receptors in aqueous solutions. Wiley-VCH; Weinheim: 2004. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Ferguson SB, Sanford EM, Seward EM, Diederich F. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1991;113:5410–5419. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Ferguson SB, Seward EM, Diederich F, Sanford AR, Chou A, Inocencio-Szweda P, Knobler CB. J. Org. Chem. 1988;53:5593–5595. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Oshovsky GO, Reinhoudt DN, Verboom W. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2007;46:2366–2393. doi: 10.1002/anie.200602815. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Biros SM, Rebek J., Jr. Chem. Soc. Rev. 2007;36:93–104. doi: 10.1039/b508530f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Rekharsky MV, Inoue Y. Chem. Rev. 1998;98:1875–1917. doi: 10.1021/cr970015o. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Kim K, Selvapalam N, Ko YH, Park KM, Kim D, Kim J. Chem. Soc. Rev. 2007;36:267–279. doi: 10.1039/b603088m. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Hecht S, Huc I, editors. Foldamers: Structure, Properties and Applications. Wiley-VCH, Weinheim; Germany: 2007. [Google Scholar]

- 39.Bautista AD, Craig CJ, Harker EA, Schepartz A. Curr. Opin. Chem. Biol. 2007;11:685–692. doi: 10.1016/j.cbpa.2007.09.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Cubberley MS, Iverson BL. Curr. Opin. Chem. Biol. 2001;5:650–653. doi: 10.1016/s1367-5931(01)00261-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Gellman SH. Acc. Chem. Res. 1998;31:173–180. [Google Scholar]

- 42.Zana R, editor. Dynamics of Surfactant Self-Assembly: Micelles, Microemulsions, Vesciles and Lyotropic Phases. Taylor and Francis, Boca Raton Fl; USA: 2005. [Google Scholar]

- 43.Gelbart WM, Ben-Shaul A, Roux D, editors. Micelles, Membranes, Microemulsions and Monolayers. Springer-Verlag; New York, USA: 1994. [Google Scholar]

- 44.Rudkevich DM, Rebek J., Jr. Eur. J. Org. Chem. 1999:1991–2005. [Google Scholar]

- 45.Xi H, Gibb CLD, Stevens ED, Gibb BC. Chem. Commun. 1998:1743–1744. [Google Scholar]

- 46.Xi H, Gibb CLD, Gibb BC. J. Org. Chem. 1999;64:9286–9288. [Google Scholar]

- 47.Green JO, Baird J-H, Gibb BC. Org. Lett. 2000;2:3845–3848. doi: 10.1021/ol006569m. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Gibb CLD, Stevens ED, Gibb BC. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2001;123:5849–5850. doi: 10.1021/ja005931p. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Gibb BC. Chem. Eur. J. 2003;9:5180–5187. [Google Scholar]

- 50.Laughrey ZR, Gibb BC. J. Org. Chem. 2006;71:1289–1294. doi: 10.1021/jo0513515. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Gibb BC. Nano-Capsules Assembled by the Hydrophobic Effect. In: Atwood JL, Steed JW, editors. Organic Nano-Structures. John Wiley and Sons; 2007. [Google Scholar]

- 52.Gibb CLD, Gibb BC. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2004;126:11408–11409. doi: 10.1021/ja0475611. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Gibb CLD, Gibb BC. Chem. Comm. 2007:1635–1637. doi: 10.1039/b618731e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Rebek J., Jr Chem. Commun. 2007:2777–2789. doi: 10.1039/b617548a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Vriezema DM, Aragonès MC, Elemans JAAW, Cornelissen JJLM, Rowan AE, Nolte RJM. Chem. Rev. 2005;105:1445–1489. doi: 10.1021/cr0300688. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Kaanumalle LS, Gibb CLD, Gibb BC, Ramamurthy V. Organic and Biomolecular Chemistry. 2007;5:236–238. doi: 10.1039/b617022f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Natarajan A, Kaanumalle LS, Jockusch S, Gibb CLD, Gibb BC, Turro NJ, Ramamurthy V. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2007;129:4132–4133. doi: 10.1021/ja070086x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Kaanumalle LS, Gibb CLD, Gibb BC, Ramamurthy V. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2004;126:14366–14367. doi: 10.1021/ja0450197. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Kaanumalle LS, Gibb CLD, Gibb BC, Ramamurthy V. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2005;127:3674–3675. doi: 10.1021/ja0425381. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Gibb BC, Mezo AR, Causton AS, Fraser JR, Tsai FCS, Sherman JC. Tetrahedron. 1995;51:8719–8732. [Google Scholar]

- 61.Dwars T, Paetzold E, Oehme G. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2005;44:7174–7199. doi: 10.1002/anie.200501365. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Podkoscielny D, Gibb CLD, Gibb BC, Kaifer AE. Chem. Eur. J. 2008 in press. [Google Scholar]

- 63.Baker R, editor. Membrane Technologies and Applications. John Wiley & Sons; New York: 2004. [Google Scholar]

- 64.Gibb CLD, Gibb BC. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2006;128:16498–16499. doi: 10.1021/ja0670916. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]